Jan Wieseke, Florian Kraus, Michael Ahearne, & …moorman/Marketing...Jan Wieseke, Florian Kraus,...

Transcript of Jan Wieseke, Florian Kraus, Michael Ahearne, & …moorman/Marketing...Jan Wieseke, Florian Kraus,...

Jan Wieseke, Florian Kraus, Michael Ahearne, & Sven Mikolon

Multiple Identification Foci and TheirCountervailing Effects onSalespeople’s NegativeHeadquarters Stereotypes

Using a large-scale, multilevel data set, this study introduces to the sales management literature the concept ofsales representatives’ headquarters stereotypes as a negative outcome of social identification. The results suggestthat work team identification fosters headquarters stereotyping more strongly when organizational identification islow than when it is high. Salespeople’s physical distance from their corporate headquarters increases work teamidentification and decreases organizational identification. Competitive intensity, as an external threat tosalespeople’s social identity, strengthens stereotyping and social identification. In addition to important theoreticalimplications, this research also provides crucial insights for managers. Headquarters stereotypes are criticallyimportant because they can have harmful consequences for sales performance and customer satisfaction. Keymanagerial implications are that managers should foster organizational identification and that using differentcompensation systems does not remedy the negative effects of stereotypes.

Keywords: stereotypes, identification, dispersed sales teams, competitive intensity, sales performance

Jan Wieseke is Professor of Marketing (e-mail: [email protected]), andSven Mikolon is a postdoctoral student in Marketing (e-mail: sven.mikolon@ rub.de), Ruhr-University Bochum. Florian Kraus is Professor ofMarketing, University of Mannheim, and Dr. Werner Jackstädt EndowedChair of Business Administration and Marketing IV and Research Fellow,C.T. Bauer College of Business, University of Houston (e-mail: kraus@bwl. uni-mannheim.de). Michael Ahearne is Professor of Marketing andExecutive Director, Sales Excellence Institute, C.T. Bauer College of Busi-ness, University of Houston (e-mail [email protected]). All authors con-tributed equally to this article. Author order was decided by coin flips.

© 2012, American Marketing AssociationISSN: 0022-2429 (print), 1547-7185 (electronic)

Journal of MarketingVolume 76 (May 2012), 1–201

The psychological literature thoroughly documents thefinding that people define themselves at least partly interms of the groups to which they belong (Ashforth

and Mael 1989; Ellemers, De Gilder, and Haslam 2004;Tajfel and Turner 1986). The process by which a groupbecomes directly linked to its members’ sense of self isreferred to as social identification (Shamir and Kark 2004).

Viewing identification as a root construct in organizations(Albert, Ashforth, and Dutton 2000), scholars have shownin numerous studies that employee–company identificationleads people to act on behalf of their organization, resultingin a variety of positive outcomes for the organization, suchas increased organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) andbetter performance (Celsi and Gilly 2010; Dukerich, Golden,and Shortell 2002; Larson et al. 2008; Olkkonen and Lippo-nen 2006; Van Knippenberg and Van Schie 2000). Simi-larly, research has shown customer–company identificationto be a predictor of customer loyalty and customer willing-ness to pay (Ahearne, Bhattacharya, and Gruen 2005; Hom-burg, Wieseke, and Hoyer 2009). Given these positive out-

comes, marketing and management scholars have typicallyviewed social identification as desirable.

However, virtually no research has investigated thepotential negative consequences of social identification pro-cesses in organizations. This lack of attention is surprising,given the fundamental prediction of social identity theorythat identification associated with in-groups drives negativestereotypes of out-groups (Tajfel and Turner 1986). Indeed,in their seminal article, Ashforth and Mael (1989, p. 20)note that “social identification leads to ... stereotypical per-ceptions of self and others.” Stereotypes can be a powerfulpredictor of negative or even antisocial intergroup behavior,such as discrimination against the targeted group (e.g.,Caprariello, Cuddy, and Fiske 2009; Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick2007; Heilman and Okimoto 2008). Therefore, inattentionto the role of negative stereotypes is a major shortcoming of previous research on social identification processes inorganizations.

Organizations are especially prone to intergroup stereo-typing because they provide their members with multiplegroup memberships for constructing their social identities,such as the shift, the work team, the department, or, moreholistically, the entire organization (Homburg et al. 2011).All groups represent possible identification foci for theirmembers (Ashforth, Harrison, and Corley 2008; Van Knip-penberg and Van Schie 2000) and at the same time arepotential targets for intergroup stereotyping. As a result,stereotyping and its detrimental behavioral outcomes, suchas scapegoating, aggression, or lack of support for the tar-geted group, are apparently ubiquitous in most organiza-tions (for reviews on behavioral outcomes of stereotypes,

see Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis 2002; Hilton and Von Hip-pel 1996).

Furthermore, because employees can simultaneouslyidentify with different groups (Ashforth and Johnson 2001;Olkkonen and Lipponen 2006) and given that identificationwith in-groups drives out-group stereotyping (Tajfel andTurner 1986), intergroup stereotypes are a likely subject ofthe interplay between different identification foci withinorganizations, such as the work team and the organizationas a whole. Indeed, identifications with different targets inthe workplace can be complicated and place conflictingdemands on people (Hekman et al. 2009). Complicationsmay arise particularly for employees working in distributedteams that are, to a certain extent, distant from their corpo-rate headquarters. Such conditions can undermine organiza-tional identification and foster fierce subgroup loyaltythrough identification with more localized groups (Cradadorand Pratt 2006). However, the negative consequences ofmultiple identifications remain largely unexplored, andempirical research in this stream has not yet consideredstereotypes as a negative identification outcome.

The current study investigates sales representatives’stereotyping of their corporate headquarters. The corporateheadquarters are particularly likely to be negatively stereo-typed because they represent a ubiquitous, high-statusgroup that possesses multiple interfaces with other organi-zational subgroups (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Reade 2001).Furthermore, according to the literature, at least two lines ofevidence demonstrate that headquarters stereotypes are par-ticularly important in sales management. First, althoughneglecting the constructs of identification and stereotyping,literature on the “thought worlds” of organizational sub-units shows that sales teams occupy a somewhat uniquethought world within organizations (Homburg and Jensen2007). Therefore, sales teams may develop a differentiatedand unique in-group identity that fosters fierce subgrouployalty, intergroup comparisons, and, subsequently, out-group stereotyping (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Haslam andEllemers 2005). This identity may particularly characterizedispersed sales teams.

Second, in a personal selling setting, salespeople are theface of an organization (Hartline, Maxham, and McKee2000), and they pervasively affect customers’ perceptions ofthe entire company through their direct interaction (Ahearne,Bhattacharya, and Gruen 2005; Liao and Chuang 2004). Thus,salespeople harboring negative headquarters stereotypesmay evoke unfavorable customer evaluations of the com-pany that subsequently affect organizational performance.

The present study has three purposes. First, by empiri-cally linking the concept of stereotypes with social identifi-cation, we shed light on potentially harmful organizationaloutcomes of social identification processes and address animportant empirical research gap. This contribution is par-ticularly consequential because organizations are highlydifferentiated systems and stereotypes can explain a varietyof intergroup contexts. Second, whereas previous researchhas predominantly examined only the organizational identi-fication of salespeople, this study investigates both theirorganizational and work team identification simultaneouslyand reveals countervailing effects of these identifications on

2 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

headquarters stereotypes. Adopting a multiple identity per-spective seems to be particularly fruitful for research deal-ing with salespeople working in dispersed sales teams,because previous investigators have argued that such condi-tions foster identification with the localized identity focusand threaten identification with the organization as a whole(Cradador and Pratt 2006). Third, the study investigateshow an external threat to a social identity in the form ofperceived competitive intensity affects salespeople’s socialidentification and headquarters stereotyping. Despite itsimportance to social identification processes, research onsocial identity threats is still in its infancy, and our resultsprovide important theoretical implications.

For the present study, we collected data from 1548salespeople in 299 sales districts across two divisions of alarge U.S.-based company in the business-to-business sec-tor. We rely on the notion of “nested identities” and baseour model on sales representatives’ simultaneous identifica-tion with their organization and their work teams. Ourresults show that physical distance between salespeople’swork teams and the corporate headquarters fosters workteam identification and diminishes organizational identifi-cation. Our investigation further reveals that work teamidentification contributes most strongly to the prevalence ofheadquarters stereotypes when organizational identificationis low rather than when it is high. Headquarters stereotypes,in turn, decrease sales performance and customer satisfac-tion with the sales interaction. Importantly, we find that dif-ferent compensation systems (commission based vs. fixedsalary) cannot deflect these negative effects of headquartersstereotyping. Furthermore, our findings show that competi-tive intensity fosters identification at both the work teamand organizational levels and also directly strengthensheadquarters stereotypes.

The Phenomenon of SocialIdentification in Organizations

Social Identity and Social Identification inOrganizationsThe social identity approach, which encompasses thetheories of social identity (Hogg and Abrams 1988; Tajfeland Turner 1979) and self-categorization (Turner et al.1987), proposes that a person’s sense of identity is partly afunction of belonging to a social group. In general, socialidentity is viewed as “that part of an individual’s self-conceptwhich derives from his knowledge of his membership of asocial group (or groups) together with the value and emo-tional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel1978, p. 63).

Three features of this definition stand out. First, socialidentity is socially constructed and comparative in naturebecause it emerges from social categories and contains infor-mation about the positional status of the particular groupand relevant comparison groups. Thus, a social identity isshared by group members, distinguishes groups (Ashforth,Harrison, and Corley 2008), and provides “the frame of ref-erence for differentiation and social comparisons” (Brewer1991, p. 476). Second, social identity is self-referential or

self-defining (Pratt 1998) because people use it to describethemselves. Third, social identity implies a hedonic elementbecause it comprises the emotional involvement with thegroup in question. In summary, social identity provides “aplace in the social world” (Simon and Klandermans 2001,p. 320) and answers two fundamental self-defining ques-tions: “Who am I?” and “How does it feel to be me?”

Social identification, as a related but distinct concept tosocial identity, is the process by which a group becomesdirectly linked to a person’s self-concept (Shamir and Kark2004). Thus, the degree of a person’s identification with aspecific group reflects the importance of a social identityfor the person (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Olkkonen and Lip-ponen 2006). More specifically, identification refers to “arelatively enduring state that reflects an individual’s readi-ness to define him- or herself as a member of a particularsocial group” (Haslam 2001, p. 383; for a review of the his-tory of the construct, see Edwards 2005). Most important,while an organization simultaneously provides multiplegroup memberships for the person, the relative degree towhich this person views each of the identities as self-descriptive is a function of his or her identification with thegiven groups (Ellemers, De Gilder, and Haslam 2004). Forexample, depending on their level of work team identifica-tion and organizational identification, some employees mayconsider themselves members of a given work team first andforemost and organization members second, whereas for oth-ers the opposite might be true (Hekman et al. 2009; Johnsonet al. 2006).

From a social identity perspective, motives for identifi-cation may include self-enhancement (Tajfel and Turner1979) and uncertainty reduction (Hogg 2000). According tosocial identity theory, in general, people strive to maintainor enhance their self-esteem and therefore identify withsocial groups that possess favorable value connotations(Tajfel and Turner 1986). People tend to identify withgroups they perceive as distinct and attractive because thesegroups enhance members’ self-esteem (Ashforth and Mael1989; Sluss and Ashforth 2008). Moreover, Tajfel andTurner (1986, p. 16) stress this self-enhancement functionof social identification, stating that “identifications …define the individual … as ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than membersof other groups.”

In addition, uncertainty identity theory, which is anextension of social identity theory, maintains that a person’sidentification with a group can also be an aversive reactionto perceived uncertainty arising from the person’s socialcontext (Hogg 2000). Indeed, research in social psychologyshows that subjective uncertainty is one of the most impor-tant motives for social identification (Grieve and Hogg1999; Hogg et al. 2007).

When people identify with a social group, they tend toact and feel in congruence with salient aspects of theirsocial identities (Edwards 2005), resulting in numerouspositive behaviors on behalf of groups that embody theirsocial identities (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Ellemers, DeGilder, and Haslam 2004). In organizational contexts, socialidentification thus motivates people to adopt several desir-able behaviors, such as OCB (Dukerich, Golden, and Short-ell 2002; Olkkonen and Lipponen 2006), organizational

Multiple Identification Foci / 3

commitment (Meyer, Becker, and Van Dick 2006), andincreased performance (Van Knippenberg 2000). Multiple Nested Social Identities in OrganizationsA growing body of empirical evidence supports the notionthat when members of organizations construe their socialidentities, they may rely on multiple group membershipssimultaneously (e.g., Hekman et al. 2009; Olkkonen andLipponen 2006; Reade 2001; Van Dick et al. 2004; VanKnippenberg and Van Schie 2000). For example, employeescan simultaneously identify with their work team and theirorganization as a whole. These multiple organizationalidentities, in turn, are hierarchically nested, with lower-order identities embedded within higher-order identities(Ashforth, Harrison, and Corley 2008; Ashforth and John-son 2001). Importantly, the literature on nested identitiesconverges on the notion that, in general, organizationalmembers are likely to identify more strongly with lower-order identities than with higher-order identities (Ashforthand Johnson 2001; for meta-analytic support, see Rikettaand Van Dick 2005).

The organizational consequences of the outcomes ofmultiple nested identities are often discrete and textured(Ashforth, Harrison, and Corley 2008). Previous researchon the outcomes of simultaneous identifications withhigher- and lower-order identities indicates that higher-order identification is more strongly related to specifichigher-order outcomes, whereas lower-order identificationis more strongly associated with specific lower-order out-comes (Riketta and Van Dick 2005). For example, Rikettaand Van Dick’s (2005) meta-analysis reveals that work teamidentification is more strongly related to outcomes on thework team level (e.g., work team extra-role behavior),whereas organizational identification is more strongly asso-ciated with outcomes on the organizational level (e.g., orga-nizational extra-role behavior). Thus, although multiplenested forms of social identification might be correlated, toa certain extent, they are also independent (Van Dick et al.2008).Multiple Nested Identities and Negative Outcomesfor the Organization Identifications with different targets in the workplace canbe complicated and impose conflicting demands on people(Hekman et al. 2009; Pratt and Foreman 2000). For exam-ple, research using a sample of physician employees showedthat work performance is most negative when physicians’professional identification is high and their organizationalidentification is low (Hekman et al. 2009). Similarly,research in management indicates that group members canrefuse to act on behalf of their organization if they thinkthat doing so will threaten their lower-order identities(Alvesson and Willmot 2002; Ashforth and Mael 1998;Fisher, Maltz, and Jaworski 1997).

The key implication of this stream of research is thatbecause people tend to act on behalf of the social identitythat is most important for their self-concept, detrimentaloutcomes on the organizational level are more likely toarise when people identify more strongly with the lower-

order identity. For example, employees who more stronglyidentify with their work team than with their organizationmight adhere to a work team goal that consists of coveringup for colleagues’ mistakes, though this practice is likely toconflict with a total quality strategy, which would be bene-ficial to the organization as a whole (Ulrich et al. 2007).Social Identification and Stereotypes inOrganizations

Defining stereotypes. Stereotypes are beliefs about thecharacteristics, attributes, and behaviors of members of cer-tain groups (Hilton and Von Hippel 1996) and are mostoften overgeneralized and rigid (Krueger et al. 2008).Stereotypes can be based on an exaggeration of actualgroup differences (Swim 1994) and can occur even in theabsence of actual group differences (Hamilton and Gifford1976; Stroessner and Plaks 2001). Importantly, even stereo-types based on actual group differences are overgeneralizedand exaggerated, reflecting a biased reality (Haslam andTurner 1992). Thus, regardless of their basis, stereotypeslead to conceptions of groups that diverge from reality(Macrae and Bodenhausen 2000). These conceptionsevolve into a stereotypical belief system that people use tojudge incoming information about out-groups (Bargh, Chen,and Burrows 1996; Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007) and useas a basis for intergroup discriminations (Caprariello,Cuddy, and Fiske 2009; Heilman and Okimoto 2008).

Linking social identification and stereotypes. The socialidentity approach, comprising social identity theory (Tajfel1978; Tajfel and Turner 1979) and its cognitive derivate self-categorization theory (Turner et al. 1987), provides a theoreti-cal framework for explaining the link between social identi-fication and intergroup stereotyping. Self-categorizationtheory maintains that when people identify with groups, theycategorize themselves as in-group members (with the in-group containing the self) and others as out-group members.As a consequence, people perceive out-group members interms of the stereotypes about their groups and not in termsof their characteristics as individual people (Ashforth andMael 1989; Tajfel and Turner 1986). For example, catego-rizing someone as elderly is automatically associated withstereotypical expectations for this category, such as walkingslowly. Therefore, according to self-categorization theory,stereotypes convey social information and are inevitablyintertwined with social categorization processes (for areview of the self-categorization perspective on stereotyp-ing, see Van Knippenberg and Dijksterhuis 2000).

In addition to self-categorization theory, social identitytheory contributes a motivational explanation for why inter-group stereotyping occurs. More specifically, social identitytheory maintains that when identified with a group, mem-bers actively try to enhance their sense of self by comparingtheir own in-group with relevant out-groups. For example,motivated by self-enhancement, people tend to denigrateout-group members after the out-group has lost status(Leach et al. 2003). These intergroup comparisons tend tobe biased in favor of the person’s own in-group. As a result,negative out-group stereotypes arise, which the person can

4 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

mobilize against the out-group to gain a positive socialidentity for the in-group.

Taken together, the social identity approach offers botha cognitive (self-categorization) and a motivational (self-enhancement) explanation for why intergroup stereotypingoccurs when a person has come to identify with a givengroup. Most important, the social identity approach proposesa direct link between social identification and intergroupstereotypes, fostering negative behaviors such as discrimi-nation against out-groups (Caprariello, Cuddy, and Fiske2009; Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007; Heilman and Okimoto2008).

Corporate headquarters as a potential target group forstereotyping. Negative intergroup stereotypes in organiza-tions may mutually arise between any organizational sub-groups. In general, however, negative stereotypes are likelyto develop toward comparison groups that are enduringlysalient and of high status in organizational contexts. Theo-retical support for this notion comes from Ashforth andMael (1989, p. 30): “A low-status group (such as noncriticalstaff function or cadre of middle managers) may go to greatlengths to differentiate itself from a high-status comparisongroup (such as critical line functioning or senior manage-ment).” Complementing this view, social psychology hasshown upward comparisons to more efficiently satisfy self-improvement motives (Taylor, Neter, and Wayment 1995).Therefore, the corporate headquarters, as a ubiquitousgroup within a firm, may be particularly subject to negativestereotyping by other organizational groups.

Conceptual Framework andHypotheses

In this section, we derive formal, testable hypotheses. Weconceptualize headquarters stereotypes as the focal con-struct in our framework, and we hypothesize that physicaldistance between sales representatives’ work teams andtheir corporate headquarters fosters work team identifica-tion and discourages organizational identification. Further-more, we assume that either identification’s effect on head-quarters stereotypes depends on the strength of the other.Thus, we derive no direct effects of the two identificationson headquarters stereotypes. We propose that sales repre-sentatives’ work team identification fosters headquartersstereotypes more strongly when organizational identifica-tion is low than when it is high. Moreover, we hypothesizethat an external threat to sales representatives’ social iden-tity, in the form of perceived competitive intensity,addresses two fundamental motives of the social identityapproach and therefore fosters both work team and organi-zational identification and strengthens headquarters stereo-types. Finally, we propose a direct negative link betweennegative headquarters stereotypes and the business out-comes of customer satisfaction with sales interaction andsales performance. We derive no hypothesis for separatedirect effects of organizational identification and work teamidentification on headquarters stereotypes because a nestedidentity model assumes that sales representatives hold bothidentifications simultaneously. We also do not explicitly

hypothesize direct effects of organizational or work teamidentification on outcomes, because such hypotheses repre-sent no incremental insights with respect to prior research.

Testing our hypotheses regarding sales performance andcustomer satisfaction with the sales interaction requiresaccounting for variables that previous studies have found tobe influential. Thus, we controlled for sales representatives’sales experience (for reviews, see Quiñones, Ford, and Tea-chout 1995; Sturman 2003), job satisfaction (e.g., MacKen-zie, Podsakoff, and Ahearne 1998), commitment (for ameta-analysis, see Riketta and Van Dick 2005), customerorientation (for a meta-analysis, see Franke and Park 2006),organizational trust (e.g., Doney and Cannon 1997), OCB(Podsakoff and Mackenzie 1994), and leader–memberexchange (LMX) (Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995). Moreover,we controlled for salespeople’s perception of control sys-tems, which can be either outcome or behavior based(Anderson and Oliver 1987; Oliver and Anderson 1994).Under outcome-based control systems, salespeople’s com-pensation usually depends on their overall sales (Andersonand Oliver 1987), and the salesperson’s objective is to allo-cate efforts to maximize overall sales. Under a behavior-based control system, however, the salesperson’s compen-sation and career progression largely depend on followingdirections provided by the firm, creating incentives for sales

Multiple Identification Foci / 5

representatives to pursue a firm’s nonsales goals, such asservice and customer satisfaction. A behavior-based controlsystem works in favor of a long-term perspective. There-fore, we assume a positive effect of a behavior-based con-trol system on customer satisfaction, because this outcomeis a longer-term one. In contrast, in the short run, sales per-formance might be harmed by the behavior-based controlsystem. Figure 1 provides an overview of the proposedhypotheses.

Physical distance from corporate headquarters andsocial identification. Previous research in the context of vir-tual work (Wiesenfeld, Raghuram, and Garud 1999, 2001)and conceptual work in marketing has suggested that geo-graphically dispersed working conditions can threaten andultimately decrease organizational identification (Cradadorand Pratt 2006; Wiesenfeld, Raghuram, and Garud 1999)and, at the same time, foster identification with more inclu-sive and proximal identities (Scott 1997), such as workteams. Construal-level theory (e.g., Henderson 2009; for areview, see Trope and Liberman 2003) and the social identityapproach offer explanations of these relationships. Construal-level theory holds that people adopt different levels of rep-resentation or construal as a function of their temporal orphysical distance to objects and events. According to thistheory, temporal or physical distance can lead to an associa-

FIGURE 1Conceptual Framework

Notes: We also controlled for the direct effect of competitive intensity and organizational and team identification on sales performance and cus-tomer satisfaction. We also controlled for the direct effects of work team identification and organizational identification on headquartersstereotypes as well as for the direct effect of distance to headquarters on headquarters stereotypes. For reasons of simplicity, the directeffects and additional controls are not depicted in the figure.

Level 2 Variable

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

!!

!

Data per Sales District Individual Data per SalesRepresentitive

Objective Data per SalesRepresentitive

OrganizationalIdentification (OI)

Distance toHeadquarters

CompetitiveIntensity

HeadquartersStereotypes

SalesPerformance

Work TeamIdentification

(WTI)

External Threats to Sales Representative’s Identity Performance OutcomesCounterveailing Effects of SocialIdentification: OI attenuates the

positive effect of WTI onheadquarters stereotypes

CustomerSatisfaction withSales Interaction

Level 1 Variable

OI¥WTI

H1a (–)

H1b (+)

H3 (+)

H5 (–)

H6 (–)H4a (+)

H2

H4b (+)

tion between distance and construal, such that more proxi-mal objects trigger lower levels of construal (involving rich,concrete, and idiosyncratic information), whereas more dis-tant objects trigger higher levels of construal (involvingrather abstract information) (Fujita et al. 2006; Henderson2009). For example, Fujita et al. (2006) provide evidencethat greater physical distance indeed leads to a moreabstract construal of social events.

The social identity approach holds that people tend toidentify with groups they perceive as distinct and attractivebecause these groups enhance members’ self-esteem (Ash-forth and Mael 1989; Sluss and Ashforth 2008). Distinctive-ness differentiates a given group from other groups and pro-vides a sharp and salient definition of what the group signifies(Mael and Ashforth 1992). The prediction of construal-leveltheory that more distant objects trigger more abstract con-strual suggests that for sales representatives, organizationaldistinctiveness is likely to blur with increased physical dis-tance between a sales team and the corporate headquarters.This is because idiosyncratic information about what theorganization makes distinct and attractive as a target forsales representatives’ identification is missing. Instead, theorganizational identity remains rather distal, potentiallyleading people to feel psychologically lost in an abstractand large entity. Thus, with increasing physical distance, theorganizational identity becomes less attractive as a targetfor sales representatives’ identification.

In contrast, given a basic human need for identification(Ashforth, Harrison, and Corley 2008), to the extent that theorganizational identity becomes less attractive as an identi-fication target, the work team as a localized and concreteidentity becomes more so. This shift occurs because thework team is the organizational unit in which people con-duct most of their day-to-day job activities (Van Dick et al.2008). More specifically, with increasing physical distance,people will progressively transfer identification from theorganization to the work team. This reasoning leads to thefollowing hypotheses:

H1: The greater the physical distance, (a) the lower is salesrepresentatives’ organizational identification, and (b) thehigher is sales representatives’ work team identification.

Social identification and headquarters stereotypes.Employees can simultaneously hold multiple nested identi-ties, such as with their organization and their work team(Bartel et al. 2007; Johnson et al. 2006; Olkkonen and Lip-ponen 2006). The extent to which people perceive each ofthese identities as self-descriptive is reflected by a person’sidentification with the given group (Ellemers, De Gilder,and Haslam 2004; Haslam and Ellemers 2005). Therefore,depending on their level of identification, some employeesmay consider themselves members of their work team firstand of the organization second, whereas for others theopposite might be true (Hekman et al. 2009; Johnson et al.2006).

We propose that headquarters stereotypes should be par-ticularly prominent when members identify strongly withtheir work teams, as a relatively exclusive organizationaldomain, and only weakly with their organization. In thiscase, self-categorization theory predicts that identification

6 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

sharpens group boundaries and enhances “us-versus-them”feelings between sales representatives’ work teams andtheir corporate headquarters (Mael and Ashforth 1992).Thus, sales representatives perceive the corporate headquar-ters more strongly in terms of the stereotypes surroundingthe headquarters (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Tajfel andTurner 1986).

Furthermore, according to the motivational perspectiveof social identity theory, when sales representatives identifywith their work teams, the comparative nature of socialidentity encourages intergroup differentiation from impor-tant comparison groups. This differentiation is motivated bywork team members striving for a more positive socialidentity (Brown and Hewstone 2005; Tajfel and Turner1979). In the case of strong work team identification, salesrepresentatives tend to comply with the self-enhancementdemands of their work teams and will try to favorably com-pare with other groups, even at the expense of the entireorganization. When organizational identification is low andwork team identification is high, comparison groups arelocated at the organizational subgroup level (Richter et al.2006), making the corporate headquarters a likely target forstereotyping.

Conversely, to the extent that sales representatives iden-tify more strongly with the organization as the most inclu-sive and highest-order identity, work teams will use head-quarters stereotypes less for regulating and interpretingintergroup relationships with the corporate headquarters(Ellemers, De Gilder, and Haslam 2004; Van Knippenbergand Dijksterhuis 2000). In this case, team members directtheir attention to the inclusive organizational domain andminimize their attention to category differences between thework team and the corporate headquarters (Richter et al.2006). For example, if a member of a sales team is highlyidentified with the holistic organization, subgroup catego-rizations—for example, into the sales team and the corpo-rate headquarters—will be less important, and stereotypesattached to them will become less diagnostic for organizingsocial information (Ellemers 1993). Indeed, previous researchin social psychology supports this notion. Employees whoidentify strongly with their work team (in this case, thehigher-order identity) and to some extent with their ethnicgroup (in this case, the lower-order identity) have more har-monious relationships with other groups than those who donot identify with the higher-order identity (Huo et al. 1996).

Likewise, when sales representatives’ identificationwith their organization is the most important identitydomain for their sense of self, they tend to act on behalf ofthe entire organization. As a result, headquarters stereotypeswill become less strong because this contributes to favor-able intergroup relationships between the sales teams andthe corporate headquarters, which ultimately is beneficial tothe entire organization. In addition, in the case of strongorganizational identification and weak work team identifi-cation, the motive for self-enhancement leads to favorablecomparisons with other organizations and decreases compari-sons with other organizational subgroups, such as the cor-porate headquarters.

Similarly, headquarters stereotypes should weakenwhen sales representatives hold a complex social identity

(Roccas and Brewer 2002) and identify equally with bothnested identities—the work team and the organization. Acomplex social identity leads sales representatives to clas-sify the corporate headquarters in terms of multiple, moredifferentiated, and nonstereotypical dimensions and identifyat least some similarities between work teams and the head-quarters, which result from membership in the same organi-zation (Hewstone et al. 2001). Thus, sales representativesperceive that the corporate headquarters and their own workteams share some common characteristics. This perceptionshould lessen us-versus-them feelings and reduce headquar-ters stereotypes. Consistent with this contention, researchhas shown that intergroup bias diminishes when membersof different social categories that are nested in a higher-order category are aware that they all share this higher-order category membership (Crisp and Hewstone 2000;Hewstone, Islam, and Judd 1993; Hewstone et al. 2001).

Finally, previous research on multiple nested identitieshas shown that equally high identification with nestedgroups contributes to members’ self-consistency and leadsto positive outcomes, such as motivation and individualwell-being (Van Dick et al. 2008), ultimately resulting in areduced desire for self-enhancement. From this reasoning,we hypothesize the following:

H2: Sales representatives’ work team identification has astronger, more positive relationship with headquartersstereotypes when organizational identification is low thanwhen it is high.

Threat to a positive social identity, key motives for socialidentification, and ambivalent effects on intraorganizationalstereotyping. With one exception (Elsbach and Kramer1996), social identity studies have only recently begun toinvestigate how people construct a positive social identityin the face of identity threats at work. According to Elsbachand Kramer (1996), identity threats can represent symbolicand sensemaking dilemmas for organization membersbecause they call into question the merit or importance ofcore, distinctive, and enduring organizational traits associ-ated with their institutions (Elsbach and Kramer 1996). Inthe face of threats, people begin to manage their identitiesmore actively (Bartel 2001). At the same time, group mem-bers are likely to turn more strongly to their in-groups(Mael and Ashforth 1992). Thus, identity threats may facil-itate cohesion in dispersed organizations and may thereforealso have functional aspects, which marketing research hasyet to explore.

From a social identity perspective, external identitythreats stimulate key motives for social identification, self-enhancement (Tajfel and Turner 1979), and uncertaintyreduction (Hogg 2000). Following Dutton and Jackson’s(1987) definition, an external threat to a group presents apotentially negative situation, arising from the environmen-tal context in which the group acts. The situation is negativebecause it involves potential loss for the group and com-prises elements of surprise and novelty (Chattopadhyay,Glick, and Huber 2001; Dutton and Jackson 1987). There-fore, as uncertainty-identity theory predicts, external threatscan induce feelings of uncertainty, enhancing people’ssocial identification with in-groups (Hogg 2000, 2008). At

Multiple Identification Foci / 7

the same time, a threat may refute a group’s attractivenessand may call a person’s social identity into question (Els-bach and Kramer 1996; Sluss and Ashforth 2008). In thiscase, the self-enhancement motive of social identity theorypredicts that members will engage in compensatory behav-iors aimed at restoring their sense of self.

When applied to the organizational subgroup level, thisline of thinking suggests that external identity threats mayhave ambivalent effects. External threats enhance organiza-tional identification (DiSanza and Bullis 1999; Elsbach andKramer 1996), which should decrease headquarters stereo-typing. However, the self-enhancement motive suggeststhat external threats should directly increase headquartersstereotypes to the extent that they challenge the favorabilityof the work team identity.

Competitive intensity and headquarters stereotypes. Socialidentity theory maintains that to satisfy self-enhancementneeds, in general, people are motivated to favorably com-pare their own in-group with relevant comparison groups(Tajfel and Turner 1986). As empirical research in socialpsychology suggests, a particularly effective way to favor-ably compare the in-group with the out-group is to nega-tively stereotype the out-group (Branscombe and Wann1994), especially when the in-group’s relative status is atstake and the favorability of members’ social identity isthreatened (Branscombe and Wann 1994; Vignoles andMoncaster 2007). Because people generally need to evalu-ate themselves favorably (Tajfel and Turner 1986), a threat-ened social identity will trigger compensatory behaviorssuch as scapegoating or stereotyping. For example, researchin social psychology has shown that when group membersperceive that their in-group’s ethics are threatened, theyengage in compensatory behaviors such as out-group dero-gation and devaluation to restore in-group favorability(Branscombe and Wann 1994; Doosje, Ellemers, andSpears 1995; Ellemers and Bos 1998). Furthermore, a seriesof experimental studies shows that a threat to a positivesocial identity can result in increased discrimination againstout-groups, whereas self-affirmation can impair discrimina-tion (Fein and Spencer 1997).

From a sales management perspective, this evidencesuggests that the work team can positively contribute tosalespeople’s sense of self when the team has prestige andhigh status. However, high competitive intensity poses amajor threat to organizations because it implies the poten-tial loss of resources for the firm (e.g., in terms of cus-tomers, turnover, sales growth), resulting in cost cutting andbudget tightening (Thomas, Clark, and Gioia 1993). Thisthreat also implies a loss of sales for salespeople (Keaveney1995) and therefore has the potential to jeopardize sales-people’s organizational prestige and status and subse-quently their self-image. Conditions of high competitiveintensity threaten the adequacy and worthiness of member-ship in an organizational sales team, and the value of thisidentity is at stake. Thus, high competitive intensity createsdifficulty for salespeople to maintain positive images ofthemselves and their fellow group members and thereforeposes a major threat to sales representatives’ identities.

Consistent with the logic of the aforementioned self-enhancement motive, in the face of a threatened social iden-tity (e.g., intense competition), salespeople should adoptstrategies to compensate for this threat. As we outlined pre-viously, theoretical and empirical evidence suggests thatstereotyping a relevant comparison group is a particularlyeffective way to resolve identity crises and protect thefavorability of the social identity. In line with our previouscontention, for salespeople, the corporate headquartersserves as a relevant comparison group. Thus, we proposethe following:

H3: The greater the perceived competitive intensity, thestronger are the sales representatives’ negative headquar-ters stereotypes.

Competitive intensity and social identification. On theindividual level, competitive intensity is especially threat-ening for sales representatives. Salespeople acting underconditions of high competitive intensity face customerswho have many options for satisfying their needs and wants(Jaworski and Kohli 1993). Complementing this view,Keaveney (1995) shows that attraction by superior competi-tors is a fundamental predictor of customer switchingbehavior. As a consequence, salespeople perceive they haveless control over their selling performance, which increasestheir feelings of uncertainty (Chandrashekaran et al. 2000).

According to uncertainty-identity theory, social identifi-cation with groups can be conceived of as a reaction to sub-jectively perceived uncertainty (Hogg 2000, 2008). Socialidentification is a particularly effective way to reduceuncertainty because classifying the self and others intosocial categories renders the self’s and others’ behavior pre-dictable (Bartel 2001; Hogg 2008). Consequently, highlyidentified group members benefit from socially derived cer-tainty. In addition, research in social psychology suggeststhat socially derived certainty in one life domain can com-pensate for uncertainty in another domain (McGregor andMarigold 2003; McGregor et al. 2001). Thus, high competi-tive intensity should be positively related to identificationdue to uncertainty reduction.

Finally, social identity maintains that people engage insupportive behavior on behalf of the groups embodyingtheir social identities (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Ellemers,De Gilder, and Haslam 2004; Tajfel and Turner 1986). Fur-thermore, people expect to receive protection and supportfrom their in-groups (their work team and their organiza-tion) and are therefore likely to band together with similarothers in the face of external threats.

People can simultaneously identify with more than oneorganizational group (Hogg and Abrams 1988; Olkkonenand Lipponen 2006). Because competitive intensity posesan equal threat to sales representatives’ work team identifi-cation and organizational identification, the fundamentalprocesses leading to identification would seem to applyequally to both identities. Therefore, we hypothesize thefollowing:

H4a: The greater the perceived competitive intensity, thestronger are the sales representatives’ (a) work team iden-tification and (b) organizational identification.

8 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

Negative headquarters stereotypes and sales represen-tatives’ sales performance. Research in social psychologyshows that stereotypes lead to discrimination against tar-geted groups (Caprariello, Cuddy, and Fiske 2009; Correllet al. 2002; Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007; Heilman andOkimoto 2008). Discrimination can take various forms,ranging from active aggression (e.g., explicitly aiming tohurt an out-group) to passive harm (e.g., disregarding theneeds of out-groups) (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007).

A corollary of this empirical evidence is that sales rep-resentatives holding strong negative headquarters stereo-types should be unwilling to adopt sales innovations andcomply with sales guidelines put in place by corporateheadquarters (e.g., for a review of factors leading to salesforce automation use, see Jones, Sundaram, and Chin2002). This unwillingness should result in lower sales per-formance (Ahearne, Srinivasan, and Weinstein 2004; Rapp,Agnihotri, and Forbes 2008).

Furthermore, if stereotypes lead to discriminationtoward the group in question, sales representatives holdingnegative headquarters stereotypes should put less effort intotheir selling activities, either because they lack motivationor because they become motivated to actively violate nor-mative expectations of their headquarters. Given that effortis a key antecedent of sales performance (Brown and Peter-son 1994; Christen, Iyer, and Soberman 2006; Sujan, Weitz,and Kumar 1994), its absence should affect sales perfor-mance adversely. From this reasoning, we hypothesize thefollowing:

H5: The stronger the sales representatives’ negative headquar-ters stereotypes, the lower is the sales representatives’sales performance.

Negative headquarters stereotypes and customer satis-faction with the sales interaction. In their role as boundaryspanners, sales representatives link an organization to itscustomers (Ahearne, Bhattacharya, and Gruen 2005; Bitner,Booms, and Mohr 1994). Regarding customers’ satisfactionwith the frontline employee, which can be defined as a cus-tomer’s overall evaluation of the interaction with the salesrepresentative (Gustafsson, Johnson, and Ross 2005), cus-tomer interaction research has shown that customers holdexpectations about how a boundary-spanning agent shouldperform his or her role within the interaction (Bitner,Booms, and Mohr 1994). When sales representatives meetcustomer expectations regarding role behavior, the result issatisfaction with the sales interaction (Bitner, Booms, andMohr 1994; Oliver 1980). Sales representatives’ negativestatements or behaviors that are based on stereotypes willinstigate negative customer perceptions of the interaction,disconfirm role expectations, and subsequently lead tolower levels of satisfaction.

In support of this proposition, research in social psy-chology suggests that stereotypes are communicated andtransmitted between people. For example, Stephan andStephan (1984) show that educators pass their stereotypeson to their pupils. Most important, this transmission caneven happen without the conscious intent of the one harbor-ing the stereotypes (Devine 1989; Monteith, Devine, andZuwerink 1993). The main implication is that if sales repre-

sentatives possess negative stereotypes of their corporateheadquarters, they are likely to make negative statementsabout their corporate headquarters when interacting withcustomers. Customers will then directly perceive stereo-types in the organization and experience sales representa-tives as acting on the basis of their stereotypes. These per-ceptions are contrary to their expectations and should leadto decreased satisfaction.

Furthermore, psychological research indicates thatmembers of in-groups tend to describe relevant out-groupsmore stereotypically and with more negative affect thantheir own in-group (Harasty 1997). Plausibly, then, wheninteracting with customers, sales representatives harboringnegative stereotypes will show more negative emotionsthan sales representatives possessing less negative stereo-types. According to emotional contagion theory (Barsade2002), the negative emotions salespeople display will spillover to their customers and decrease enjoyment of the per-sonal interaction (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2006). Because cus-tomers also tend to form expectations about the level ofpositive affect related to the interaction, this spillovershould lead to decreased satisfaction.

H6: The stronger the sales representatives’ negative headquar-ters stereotypes, the lower is customer satisfaction withthe sales interaction.

MethodSample

Research context. We collected data from the sales forceof a U.S.-based Fortune 500 company in the cleaning andsanitizing industry. The sales representatives surveyed inour study work in sales teams in 299 sales districts, witheach sales team operating in a single sales district. The salesforce comprises two separate divisions. The sales represen-tatives in the first division primarily acquire and sell to newcustomers. Their compensation is heavily commissionbased and depends on their sales performance (this divisioncomprises 161 sales teams). The salespeople in the seconddivision primarily up- and cross-sell the company’s prod-ucts to existing customers and service them. They receive afixed salary (this division comprises 138 sales teams). Thecompany does not mix sales representatives from differentdivisions to compose a work team; rather, they operate inseparate sales teams. Sales teams of both divisions arephysically distant from the firm’s headquarters. The sales-people working in sales districts experience close employee–customer interactions, a circumstance especially conduciveto testing potential customer reactions to employees’ head-quarters stereotypes. Other industries also have these fea-tures, including insurance companies, banks and financialservice providers, pharmaceutical firms, tourism compa-nies, and retailers (e.g., clothing, computer hardware).

Data source. We acquired multiple-source data for ourstudy. We obtained data from sales representatives nested insales districts as well as objective firm data on the individualsalesperson’s sales performance. We also used customer-based data reporting how satisfied customers were with the

Multiple Identification Foci / 9

sales interaction. We distributed questionnaires to all thecompany’s salespeople (n = 2290) within 302 sales districtsacross the two divisions. The final sample includes 1548sales representatives (a 67% overall response rate), ofwhich 903 are commission based and 645 have fixedsalaries, from 299 sales districts. Additional tests showedno significant differences between the responses from earlyversus late respondents on all the major constructs and onthe key demographic variables, suggesting that nonresponsebias is not a problem in our data (Armstrong and Overton1977).Construct MeasuresThe Appendix provides a complete list of measurementitems used in the study. We measured distance to headquartersas the absolute physical distance in miles between each salesteam’s location and the location of the corporate headquar-ters.

To measure salespeople’s stereotypes of corporate head-quarters, we followed Gardner’s (1994) stereotype differen-tial technique, which is consistent with existing work in thisarea (Homburg et al. 2011). We measured the organizationalas well as team identification of sales representatives usingMael and Ashforth’s (1992) well-established six-item scale.We measured competitive intensity with Jaworski andKohli’s (1993) four-item scale. The unit of analysis we usedfor this construct is the sales district (i.e., level 2), for sev-eral reasons. First, the company has no national competitor,which means that competition is on a local, or district,level. Second, talking to company representatives made itclear that the competitive intensity varies between sales dis-tricts: Salespeople who work in the same sales district com-pete with the same local competitors, whereas salespeoplein other districts deal with different competitors. Third, dataanalysis shows that aggregation is necessary.

We calculated median within-group agreement (medianrwg) and intraclass correlations (ICC[1] and ICC[2]), statis-tics that are frequently used to justify aggregation of data tohigher levels of analysis (Bliese 2000). Compared with theconventional thresholds for these statistics (James, Dema-ree, and Wolf 1984), the rwg coefficient was sufficiently highfor competitive intensity (rwg = .80), as were its intraclasscorrelation coefficients (ICC[1] = .21, ICC[2] = .52). Theseresults suggested that data aggregation was appropriate.Thus, we treated competitive intensity as a group-levelvariable and aggregated individual representatives’ ratings.

Outcomes. For sales performance, we used the year-over-year growth percentage of total sales per employee.We obtained this objective measure from the company’ssales records and computed the sales trend improvement foreach salesperson. We used year-over-year percentagegrowth in total sales per employee for two reasons. First,using trend improvements enabled us to control for season-ality, differences in sales territories and competitors, andother potential confounding factors to measure true sales-person performance (see also Ahearne et al. 2010). Second,measuring sales performance using year-over-year percent-age growth of sales is an approach frequently applied in

previous research in marketing (e.g., Lam, Kraus, andAhearne 2010; Matsuno and Mentzer 2000).

We measured customer satisfaction with callbacks. Thecompany’s customer service department called customerswithin 60 minutes after a salesperson had contacted themand asked whether their request had been addressed to theircomplete satisfaction. These callbacks yielded a customersatisfaction measure in the form of the percentage of satis-fied customers per salesperson. The response rate rangedbetween 90% and 100% per salesperson. These measuresare the company’s standard criteria for evaluating sales rep-resentatives’ sales performance and customer satisfactionon a monthly basis. We used the sales performance growthand customer satisfaction for the month in which we con-ducted the study.

Controls. We included sales experience, job satisfaction,salespeople’s control systems perception, customer orienta-tion, organizational commitment, organizational trust,OCB, LMX, and sales representatives’ corporate headquar-ters contact as covariates in our empirical analyses to testthe robustness of the proposed relationships while control-ling for important extraneous influences. We measured jobsatisfaction using Hackman and Oldham’s (1975) well-established scale and organizational commitment usingAllen and Meyer’s (1990) scale. We evaluated customerorientation with Thomas, Soutar, and Ryan’s (2001) shortform of Saxe and Weitz’s (1982) scale and assessed organi-zational trust with Doney and Cannon’s scale (1997), OCBwith Podsakoff and Mackenzie’s (1994) well-establishedscale, and LMX with Graen and Uhl-Bien’s (1995) scale.We measured sales representatives’ perception of controlsystems using Oliver and Anderson’s (1994) scale, whichconsists of 21 separate items representing five uniquedimensions of the perceptions of a sales representative’scontrol system. Following Oliver and Anderson (1994), weconverted all subscales to z-scores and additively combinedthem to form an index in which an outcome-based controlsystem is represented by a lower score.Measurement ModelWe conducted an exploratory factor analysis using maxi-mum likelihood extraction and an oblique rotation to evalu-ate the reflective scales. The commonalities are all greaterthan .54, and the extracted (and rotated) factors account for79.3% of the variance in the items’ variance–covariancematrix. Factor loadings for all constructs ranged from .544to .967, with no unusually high cross-loadings. We calcu-lated reliabilities for each scale and deemed them accept-able (all reliabilities were greater than .78; see Table 1).

In the next step, we conducted a confirmatory factoranalysis. Although the chi-square statistic (1543, d.f. = 204)was significant, an examination of the comparative fit index(CFI) and standard root mean square residual (SRMR) esti-mates (.95 and .04, respectively) suggests that the measure-ment model fits well. Furthermore, the root mean squareerror of approximation (RMSEA) value of .07 comes closeto the recommendation of .06 or less (Hu and Bentler 1999;Kline 2005). All factor loadings of the indicators on theirrespective latent constructs were significant. Furthermore,

10 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

the lowest composite reliability was .80, and the lowestaverage variance extracted was .57, providing evidence thatall constructs possess adequate reliability and convergentvalidity (Bagozzi 1980; Fornell and Larcker 1981). In addi-tion, all squared correlations between the latent constructswere smaller than the average variance extracted from therespective constructs, further supporting the measures’ dis-criminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981).Analytical ApproachBecause the salespeople were nested in a particular salesdistrict and because their data could vary across the 299sales districts, the responses from sales representativesworking in the same district might be interdependent. Todetermine whether a two-level approach was warranted, weexamined intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and cor-responding design effects to ascertain the extent of system-atic group-level variance (Duncan et al. 1997). The result-ing ICCs indicate that the proportion of total varianceaccounted for by between-cluster variation is of sufficientsize to substantiate a multilevel approach. In addition,design effects, calculated by multiplying the ICC by (aver-age cluster size – 1) and adding 1, were generally greaterthan 2, suggesting that a multilevel structure should not beignored (Múthen and Satorra 1995).

Consequently, to take into account the hierarchicalstructure of the data, we estimated a multilevel structuralequation model using MPlus 5 using full maximum likeli-hood (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). This approach has theadvantage over other hierarchical linear modeling methodsof enabling the modeling of both structural and measure-ment models simultaneously. In our study, we modeledcompetitive intensity and distance to headquarters as level 2variables because they vary by sales district.

ResultsBecause standard fit indexes are not available with thenumerical integration procedure used by MPlus to estimatelatent interactions, which are part of our model, weemployed a log-likelihood difference test (–2 ¥ difference inlog-likelihoods ~ 2 , d.f. = number of freed paths) to comparethe fit of the evaluated nested models, and we used Akaike’sinformation criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information cri-terion (BIC) to compare the fit of selected nonnested models.

We first ran an unconditional (intercepts only) model,which substantiated our multilevel design. Next, we fit abaseline model that estimated all direct effects on organiza-tional and team identification as well as sales performanceand customer satisfaction, eliminating the paths pointing tothe mediating variable headquarters stereotypes whileretaining headquarters stereotypes in the model. The resultssupport the overall framework of the model.

Next, we estimated the hypothesized model. A compari-son of AIC and BIC values confirms that this less restrictedmodel fits better than the direct effects–only model (122.76lower AIC and 128.42 lower BIC for the less restrictedmodel). This improved model reflects significant relation-ships between organizational and team identification aswell as competitive intensity (i.e., the antecedents) and

Multiple Identification Foci / 11

TABLE 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Scale Intercorrelations

Variable

MSD

Cronbach’s a

AVE

12

34

56

1.Co

mpe

titive

intens

ity5.33

1.22

.75

.60

2.Or

ganiz

ation

al ide

ntific

ation

5.69

1.33

.81

.59

.54**

3.Te

am id

entifica

tion

4.99

1.54

.80

.61

.40**

.49**

4.He

adqu

arters stereotyp

es4.57

.97

.77

.57

.22**

–.20

**.59**

5. D

istan

ce to

hea

dqua

rters

1136

472

.—a

.—a

.10*

–.16

**.17**

.19**

6.Sa

les perform

ance

6.28

9.60

.—a

.—a

.12**

.29**

.26**

–.33

**.02

7.Cu

stomer satisfac

tion

80.5

15.6

.—a

.—a

.15**

.25**

.28**

–.30

**–.01

.13**

*p< .05.

**p< .01.

a Con

struc

ts are mea

sured by

a sing

le ite

m.

Notes:

AVE = av

erag

e va

rianc

e ex

tracte

d. D

istan

ce to

hea

dqua

rters is

mea

sured in

miles.

headquarters stereotypes (i.e., the mediator), fulfilling addi-tional requirements for a mediated structure—that is, sig-nificant antecedent–final outcome and mediator–final out-come relationships (Baron and Kenny 1986).

The log-likelihood difference test for this hypothesizedmodel confirmed that the inclusion of the effects on head-quarters stereotypes provides a stronger fit to the data (D2 =95.17, d.f. = 7, p < .01) than the nested model that did notinclude these mediating effects. Next, we summarize modelresults in the context of our hypotheses.

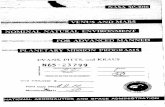

The results indicate a negative relationship between dis-tance to corporate headquarters and organizational identifi-cation (H1a: = –.14, p < .05) and a positive relationshipbetween distance to headquarters and team identification(H1b: = .17 p < .01), in support of H1a and H1b. Further-more, we find a significant interaction between organiza-tional and team identification as proposed in H2 (H2: =–.22, p < .01). As Figure 2 shows, work team identificationmore strongly fosters headquarters stereotypes when orga-nizational identification is low than when it is high. A posi-tive relationship between competitive intensity and head-quarters stereotypes ( = .11, p < .05) substantiates H3. Wealso found that competitive intensity positively influencesboth team identification (H4a: = .28, p < .01) and organi-zational identification (H4b: = .38, p < .01), in support ofH4a and H4b. The significant negative impacts of headquartersstereotypes on sales performance (H5: = –.27, p < .01) andcustomer satisfaction with the sales interaction (H6: = –.23,p < .01) lend support to H5 and H6, which posit that strongheadquarters stereotypes will result in a decrease in salesperformance as well as satisfaction with the sales interaction.

Finally, we tested whether competitive intensity moder-ates the relationship between distance to corporate head-quarters and work team identification. We found a significant

12 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

moderation effect ( = .09, p < .05), such that the relation-ship is stronger when competitive intensity is high than whenit is low.1 Table 2 shows results of the series of models.Mediational AnalysisAlthough the results generally support the hypothesizedconceptual model, we used the comparison of log-likelihooddifference tests of the baseline model and the hypothesizedmodel to assess whether the mediations present are full orpartial (Baron and Kenny 1986; MacKinnon et al. 2002;Mathieu and Taylor 2007). The hypothesized model, whichincluded the indirect effect of organizational identification,team identification, and competitive intensity mediatedthrough headquarters stereotypes on sales performance andcustomer satisfaction, exhibited a superior fit to the baselinemodel (D2 = 95.17, d.f. = 7, p < .01), which did notinclude the effects of organizational identification, teamidentification, and competitive intensity on headquartersstereotypes. Although we still find significant effects of bothorganizational and team identification on sales performanceand customer satisfaction with the sales interaction, the directeffects of competitive intensity on those outcomes lose sig-nificance when we include headquarters stereotypes as amediator. Therefore, we find that headquarters stereotypespartially mediate the organizational and team identification–outcomes links, while these stereotypes fully mediate thecompetitive intensity–outcome link.

Furthermore, in an additional analysis to rule out alter-native explanations, we also tested organizational trust andOCB as mediators instead of headquarters stereotypes.Unlike headquarters stereotypes, neither trust nor OCBmediate the effects of organizational and team identificationon sales performance and customer satisfaction with thesales interaction. Despite these findings, we controlled for theeffects of organizational trust and OCB in the final model.ControlsIn examining the control variables, we found significant rela-tionships between the controls and sales performance as wellas customer satisfaction for most of the relationships. Theresults show that even in the presence of those performancepredictors, sales representatives’ headquarters stereotypesstill decrease sales performance and customer satisfactionwith the sales interaction. Moreover, our results indicate thata behavior-based control system hinders sales performance( = –.13, p < .05), which means that an outcome-basedcontrol system increases sales performance. However, wealso find that a behavior-based control system has a positiveimpact on satisfaction with the sales interaction ( = .10, p <.05). These effects are in line with the findings from previ-ous research. Finally, in predicting headquarters stereotypes,we controlled for LMX quality. The results indicate thatLMX does not significantly influence sales representatives’headquarters stereotypes.

FIGURE 2Interaction Effect Between Team Identification

and Organizational Identification on HeadquartersStereotypes

53!!

FIGURE 2 Interaction Effect Between Team Identification and Organizational Identification on Headquarters Stereotypes

!!

tceff EniotcaretIn B eenwet

!!

FIeen d naonitcaifitndeImaTe

!!

ERGUFI 2tcaifitndeIlaonitazingarOd

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

Low Team Identification High Team Identification

6.2

5.7

5.2

4.7

4.2

Headquarters Stereotypes

Low organizational identificationHigh organizational identificationMedium organizational identification

53!!

FIGURE 2 Interaction Effect Between Team Identification and Organizational Identification on Headquarters Stereotypes

!!

!!

!!

ERGUFI 2tcaifitndeIlaonitazingarOd

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

53!!

FIGURE 2 Interaction Effect Between Team Identification and Organizational Identification on Headquarters Stereotypes

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

53!!

FIGURE 2 Interaction Effect Between Team Identification and Organizational Identification on Headquarters Stereotypes

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

!!

1Following a suggestion by an anonymous reviewer, we alsotested whether sales representatives’ customer orientation attenu-ates the negative effect of headquarters stereotypes on customersatisfaction with the sales interaction. The results support a signifi-cant moderation effect.

Multiple Identification Foci / 13

TABLE 2Model Comparison and Effects

Model 1 Model 2(Baseline) (Hypotheses) Model 3 Model 4

RelationshipsDistance to headquarters Æ organizational identification (H1a) –.16** –.14* –.14* –.10*Distance to headquarters Æ team identification (H1b) .17** .17** .12* .15**Distance to headquarters Æ headquarters stereotypes .19** .20** .16** .14*Distance to headquarters ¥ competitive intensity Æorganizational identification .n.s. .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Distance to headquarters ¥ competitive intensity Æteam identification .09* .09* .08* .08*Team identification ¥ organizational identification Æheadquarters stereotypes (H2) .— –.22** –.15** –.15**Organizational identification Æ headquarters stereotypes .— –.40** –.32** –.34**Team identification Æ headquarters stereotypes .— .26** .18** .19**Competitive intensity Æ headquarters stereotypes (H3) .— .11* .10* .10*Competitive intensity Æ team identification (H4a) .29** .28** .22** .21**Competitive intensity Æ organizational identification (H4b) .38** .38** .31** .31**Headquarters stereotypes Æ sales performance (H5) –.29** –.27** –.10* –.25**Headquarters stereotypes Æ customer satisfaction (H6) –.27** –.23** –.20** –.20**Competitive intensity Æ sales performance .07* .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Competitive intensity Æ customer satisfaction .10* .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Organizational identification Æ sales performance .17** .16** .10* .10*Organizational identification Æ customer satisfaction .14* .13* .09* .10*Team identification Æ sales performance .14* .11* .09* .09*Team identification Æ customer satisfaction .12* .09* .08* .08*

Controlled RelationshipsOrganizational identification Æ trust .— .19** .12** .16**Team identification Æ trust .— .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Team identification ¥ organizational identification Æ trust .— .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Competitive intensity Æ trust .— .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Trust Æ sales performance .09* .09* .07* .07*Trust Æ customer satisfaction .12* .10* .08* .08*Organizational identification Æ OCB .— .21** .13* .17**Team identification Æ OCB .— .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Team identification ¥ organizational identification Æ OCB .— .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Competitive intensity Æ OCB .— .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.OCB Æ sales performance .13** .12* .08* .09*OCB Æ customer satisfaction .15** .13** .09* .10*HQ contact Æ headquarters stereotypes .— .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.LMX Æ headquarters stereotypes .— .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Sales experience Æ sales performance .09* .08* .07* .08*Job satisfaction Æ sales performance .n.s. .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Control systems Æ sales performance –.15** –.13* –.11* –.10*Organizational commitment Æ sales performance .16** .13** .13** .15**Customer orientation Æ sales performance .20** .18** .18** .16**Sales experience Æ customer satisfaction .12* .10* .08* .10*Job satisfaction Æ customer satisfaction .n.s. .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Control systems Æ customer satisfaction .11* .10* .09* .10*Organizational commitment Æ customer satisfaction .n.s. .n.s. .n.s. .n.s.Customer orientation Æ customer satisfaction .21** 19** .19** .18**

d.f. 237 223 447 447Log-likelihood –24,018.43 –23,922.98 –27,848.17 –27,848.17(–2LL change) .(—) (95.45**) .(—) .(—)

AIC 52,184.67 52,061.04 52,672.12 52,672.12BIC 52,815.43 52,686.30 53,431.23 53,431.23*p < .05.**p < .01. Notes: n.s. = not significant. Model 3: Commission-based sales representatives only; Model 4: Fixed salary-based sales representatives only.

14 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

Additional AnalysisBecause the sales representatives’ compensation (commis-sions vs. fixed salary) differs across the two divisions, weran our model using the data from the commission-basedsales representatives and the salespeople with fixed salariesseparately to examine whether the results change. We con-ducted a multigroup analysis using the affiliation with thedivision as grouping variable.2 The last two columns ofTable 2 summarize of our findings. The results for the twodivisions are virtually identical, with no differences in thesignificance of relationships among the variables of inter-est. However, a significant finding is that the impact ofheadquarters stereotypes on sales performance is much lessnegative for the sales representatives whose salaries areheavily commission based ( = –.10, p < .05) than for thesales representatives with fixed salaries ( = –.25, p < .01).In contrast, the negative effects on customer satisfactionwith the sales interaction are the same for the commission-based ( = –.20, p < .01) and fixed salary ( = –.20, p < .01)sales representatives.

To test for the significance of this difference, we com-pared the chi-square from a model with all parametersallowed to be unequal across groups to the chi-square froma model with only the effect of interest–sales performanceregressed on headquarters stereotypes, constrained to beequal across groups. The model with all parameters freelyestimated in the two groups reached acceptable fit measures(CFI = .92, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .04). Although the CFIis slightly below the value Hu and Bentler (1999) suggest,in combination with an RMSEA of .06 and an SRMR of.04, the model fit is acceptable.

The partial invariance model with the effect of interestconstrained to be equal across commission- and salary-based sales representatives showed a significantly poorermodel fit (D2(1) = 13.67, p < .01). The CFI of .87, theSRMR of .132, and the RMSEA of .163 suggest that the fitcan be improved. The findings imply that the size of thenegative coefficient for the headquarters stereotypes–salesperformance link differs significantly across the two divi-sions. In summary, the impact of headquarters stereotypeson sales performance is significantly less negative for salesrepresentatives who are heavily compensated on commis-sion than for those who receive a fixed salary. At the sametime, the negative effects on customer satisfaction are virtu-ally identical for both groups.

General DiscussionDrawing on the notion of multiple nested identities and thesocial identity approach (Tajfel and Turner 1986), we pro-posed and empirically tested our hypotheses. The resultsshow that physical distance from the corporate headquartersenhances sales representatives’ work team identificationand diminishes their organizational identification. Identifi-

cation with the work team most strongly contributes to theprevalence of negative headquarters stereotypes when orga-nizational identification is low, and headquarters stereo-types in turn lower sales performance and customer satis-faction with the sales interaction. Competitive intensityincreases social identification at both levels and alsodirectly triggers headquarters stereotypes. Furthermore, dif-ferent compensation systems (commission based vs. fixedsalary) do not forestall the negative effects of headquartersstereotypes on sales performance and customer satisfactionwith the sales interaction.Limitations and Theoretical Implications The collection of a large-scale, multilevel data set, such asthe one on which our study is based, was only possible byworking closely with one company. Although this companyis structurally characteristic for its industry (e.g., insurancecompanies, banks and financial service providers, tourismcompanies, retailers), further research is needed to examinethe cross-industry stability of our findings. Furthermore, inour study, we merely considered negative stereotypes.However, according to the social psychology literature,positive and mixed group stereotypes can exist as well. Forexample, stereotypes against elderly people might includepositive (e.g., wise) and negative (e.g., senile) traits. There-fore, further research should investigate the role of positivestereotypes in marketing and management.

The current study makes important contributions to thefield of applied social identity theory in marketing and salesmanagement research (e.g., Bhattacharya and Sen 2003;Homburg, Wieseke, and Hoyer 2009; Hughes and Ahearne2010). Whereas prior research has concentrated merely onpositive outcomes of social identification in organizations(e.g., OCB, organizational commitment, increased perfor-mance), this study investigates the link between social iden-tification in organizations and the prevalence of intraorgani-zational stereotyping as a negative outcome of identification.Therefore, linking the concept of stereotypes to social identi-fication, we challenge the notion that social identification isthoroughly desirable, which has been asserted in previousmarketing research. Given that applications of the socialidentity approach and social identification are still gainingmomentum in marketing and given our results, which showthat headquarters stereotypes can adversely influence bothsales performance and customer satisfaction with the salesinteraction, stereotypes are highly relevant for furtherresearch.

Moreover, the concept of stereotypes matters because ofits theoretical connection with intergroup-related topics inthe marketing and sales literature. For example, stereotypescan serve as a fruitful basis for explaining the interfacebetween marketing and other business functions, such asmarketing’s boundaries with sales or research and develop-ment. This stream of research lacks a thorough theoreticalfoundation. Thus, the construct of stereotypes, with itsstrong theoretical background, could enrich the marketinginterface literature.

Another important contribution of our study lies in thesimultaneous examination of sales representatives’ multiple

2We also evaluated the invariance of the measurement modelacross the two groups of sales representatives. The factor structureis invariant across groups, providing evidence that the derivedscales can be used with some confidence in both groups of salesrepresentative.