Gia sư lớp 8

-

Upload

bookbooming-nha-sach -

Category

Education

-

view

574 -

download

0

description

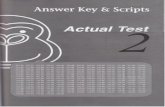

Transcript of Gia sư lớp 8

- 1.Click to visit