Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change ... · Georgetown, Guyana:Disaster Risk and...

Transcript of Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change ... · Georgetown, Guyana:Disaster Risk and...

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

Report prepared for the Inter‐Amercian Development Bank

Final

November 2019

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

i

Executive Summary

This report provides the results of the Disaster Risk and Climate Vulnerability Assessment (DRCVA) that has

been undertaken for the capital city of Guyana – Georgetown and its surrounding area. This study is one of a

series of baseline studies for Georgetown, forming part of the Inter‐American Development Bank’s (IDB)

Emerging and Sustainable Cities Initiative. The studies have been developed under the IDB’s technical

cooperation agreement with Guyana’s Central Housing and Planning Authority, titled “Climate Resilience

Support for the Adequate Housing and Urban Accessibility Program in Georgetown, Guyana” (GY‐T1137).

The DRCVA takes account of climate and land use change as well as alternative adaptation approaches. The

key findings from this study and the recommended next steps are summarized below.

Key messages

● Neighbourhood Democratic Councils (NDC) in Regions 3 and 4, the Regional Democratic Council (RDC) for Region 3 and the Municipal Council for Georgetown all identified coastal and inland flooding as the highest priority hazards for DRCVA efforts.

● Today, the expected annual damage from flooding is around GYD 1.3 billion (USD 6 million) across the wider Georgetown area with a further GYD 0.625 billion (USD 3 million) of disruption and repair to critical infrastructure; this equates to approximately 1% of economic activity. The expected annual (average) number of people exposed to flooding exceeding 0.5m is around 10,200. Forty‐six critical infrastructure sites (including hospitals, bus station, health clinics, fire stations, hospital, military barracks, police station, school and both airports) experience flooding during major storms (exceeding a 1in100 year return period).

● Assuming a business as usual adaptation approach, the expected annual damage from flooding is projected to reach between USD 10‐12 million by 2040s in response to climate change and projected urban growth. The expected annual number of people exposed to flooding is also likely to increase significantly. The “Business as Usual” approach therefore is not a viable DRCVA option for Georgetown and a more ambitious adaptation strategy is required.

● Clear and decisive action now could dramatically reduce economic damages from flooding and improve Georgetown’s resilience. This will be most effective if it includes:

spatial planning and building regulation that embrace flood risk management related issues

realign the coast and maintain green space where possible to make space for a natural response to sea level rise and surface water by adopting a ‘living with water’ approach.

selectively implement hard measures to hold the line by constructing and rehabilitation of hard sea and flood defences such as sea walls and embankments where necessary.

promote a ‘naturally resilient coastline’ with soft measures (ecosystem‐based adaptation) to restore and expand mangroves and sediment management.

strategic management of land drainage, through improved channel management and rehabilitation/replacement of control structure and pumps.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

ii

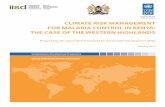

Given a feasible or smart adaptation approach future risks are much lower (Figure A), with a projected 2040s

Expected Annual Damage (EAD) of USD 5.5‐6.5 million and USD 3‐4 million respectively. Figure A

demonstrates the changing flood risks under a business as usual, feasible and smart adaptation scenarios

through the 2030s and 2050s.

Figure A Future flood risks: business as usual, feasible and smart adaptation scenarios

Source: Sayers and Partners (2019)

Next steps beyond this project

Successful adaptation will require significant resources (both financial and human). To take forward the

findings of this study, the high‐level analysis presented here will need to be translated into actionable (and

investable) plans. In particular, the development of a strategic urban and coastal management policy and

action plan is recommended. This project would aim to map and model coastal processes to enable better

protection of the coastal zone and provide the integrated framework of coastal policy planning with

supporting detailed investment plans. There is overlapping legislation which has led to coastal and urban

management being shared among several institutions such as MoPI, EPA, GFC, NAREI and GL&SC. The

integrated plan should strengthen participation among these major stakeholders and sectors, and provide an

agreed strategy plan which, if developed well, should guide decision making, promote awareness of the

issues and facilitate the execution of programs to manage coastal resources and reduce vulnerability climate

change.

The project should address issues relating to policy development, analysis and planning, inter‐agency

coordination, public education and awareness‐building, environmental control and compliance, monitoring

and measurement, and information management alongside a programme of investable infrastructure

improvement actions. Secondly, the development of an improved forecasting and early warning system is

proposed. This has been suggested by stakeholders throughout this study. Although not the focus here it is

recommended that future attention is also directed towards providing timely and reliable information on

forecast and projected flood risks to support early action.

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

14.0

Low High Low High Low High Low High Low High Low High

2030s 2050s 2030s 2050s 2030s 2050s

PresentDay

Business as Unsual Feasible Smart

Expected Annual Dam

ages (USD

, m)

Coastal Rainfall

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

iii

Authorship and acknowledgements

Team members

IDB: Patricio Zambrano‐Barragan, team leader (CSD/HUD); Edgar Lemus, Derise Williams (CCB/CGY); Merle

Reyes (WSA/CGY); Tanja Lieuw (CCS/CGY).

Consultants

Vivid Economics (consultant lead, and lead CE3): Charlie Dixon, Neeraj Baruah with in‐country support from

Haimwant Persaud

Sayers and Partners (lead for CE2 – this report): Paul Sayers, Jonathan McCue, Harvey Rodda, Jack Dearman,

Giorgia Sacco with in‐country support from Ranata Robertson.

Aether: (lead for CE1) Melanie Hobson, Ryan Glancy

Guyana stakeholders

Government authorities: Central Housing and Planning Authority, Solid Waste Management Dept – Ministry

of Communities; Guyana Lands and Survey Commission; Agricultural Sector Development Unit and Hydro‐

meteorological Service – Ministry of Agriculture; Civil Defence Commission; Ministry of Natural Resources;

Office of Climate Change and Environmental Protection Agency – Ministry of the Presidency; Guyana

Mangrove Restoration Project; Sea and River Defence Unit, Work Services Group and Transport and

Harbours Dept. – Ministry of Public Infrastructure; National Drainage and Irrigation Authority; Guyana

Bureau of Statistics; Guyana Power and Light; Guyana Water Inc.; Guyana Maritime Administration; Faculty

of Environmental and Earth Sciences – University of Guyana; National Agriculture Research and Extension

Institute.

Academic partners

Faculty of Environmental and Earth Sciences – University of Guyana; National Agriculture Research and

Extension Institute.

Citation: Sayers and Partners (2019). Disaster risk and climate change vulnerability assessment . A report for

the Inter‐American Development Bank produced in association with Vivid Economics and Aether.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

iv

Acronyms

CDC ‐ Civil Defence Commission

CH&PA ‐ Central Housing and Planning Authority

DRCVA ‐ Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

DTM – Digital Terrain Model

EAD ‐ Expected Annual Damage

EPA – Environmental Protection Agency

ESCI ‐ Emerging and Sustainable Cities Initiative.

GFC – Guyana Forestry Commission

GL&SC – Guyana Lands and Surveys Commission

GSDS ‐ Guyana State Development Strategy

IDB ‐ Inter‐American Development Bank

JICA ‐ Japan International Cooperation Agency

JRC – Joint Research Centre (European Commission)

MoPI – Ministry of Public Infrastructure

NAREI ‐ The National Agricultural Research & Extension Institute

NDC ‐ Neighbourhood Democratic Council

RDC – Regional Democratic Council

SPL – Sayers and Partners LLP

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

v

Glossary

Adaptation: A continuous process of adjustment in natural, human or infrastructure systems in response to

actual or expected future change with the aim of moderating harm or exploiting beneficial opportunities.

Community resilience‐building: This is a community‐driven process, rich with information, experience, and

dialogue, where participants identify top hazards, current challenges, strengths, and priority actions to

improve community resilience to all hazards today, and in the future.

Climate change: A change in the statistical properties of the climate system when considered over long

periods of time (including mean and variance).

Ecosystem‐based Adaptation (EbA): EbA is the use of biodiversity and ecosystem services as part of an

overall adaptation strategy to reduce the adverse effects of climate change (CBD 2009) and the role of

sustainable management, conservation and restoration of natural systems.

Expected Annual (economic) Damage (EAD): An integration of the relationship between annual probability of

occurrence of a flood (taking account of the storm and system states) and the associated consequence.

Exposure: Any component of a physical location, population or habitat that may suffer harm (loss of well‐

being) when subject to a hazard.

Event risk: The damage associated with a particular (storm) event

Hazard (and threats): Any situation with the potential to cause harm. A hazard maybe a function of the

environment (a storm surge) or arise directly from a human activity (a cyber threat).

Nature ‐based solutions (‘soft’ engineering). Actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or

modified ecosystems, that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing

human well‐being and biodiversity benefits.

Resilience: The capacity of social, economic and environmental systems to cope with a hazardous event or

trend or disturbance, responding or reorganizing in ways that maintain their essential function, identity and

structure, while also maintaining the capacity for adaptation, learning and transformation.

Risk: Typically defined as combination of the chance that a given hazard occurs and the associated

consequences (that in turn reflects the vulnerability of those exposed to the hazard, either directly or

indirectly).

Risk Assessment: The process of determining the qualitative or quantitative value of risk. It determines the

nature and extent of the risk by considering the hazard, vulnerability as well as capacities to cope

(resilience).

Vulnerability: The degree of harm (e.g. economic loss) when a receptor (e.g. a house, person, business etc.)

is exposed to given severity of hazard (e.g. a flood depth of 1m). Vulnerability is the function of several

factors including physical, social/cultural, economic, and ecological which increase or reduce susceptibility or

resilience to the impact of a hazard.

Vulnerability Assessment: This activity seeks to examine the individual factors of vulnerability for a place or

population. It attempts to identify the features which are susceptible to damage as well as those which

provide some protection (resilience) from such negative effects. It may be used to prioritize mitigative

interventions as well as recovery, response and developmental planning.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

vi

Contents

Authorship and acknowledgements .................................................................................................... iii

Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................. iv

Glossary ................................................................................................................................................. v

1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Priority climate related hazards and risks ............................................................................................ 4 3 Present day flood risk ........................................................................................................................... 8 4 Future flood risk .................................................................................................................................. 33 5 Adaptation cost ................................................................................................................................... 45 6 Conclusions ......................................................................................................................................... 49

Appendices .......................................................................................................................................... 51

List of tables

Table 1 Storm scenarios: coast and rainfall ..................................................................................................... 14

Table 2 Drainage capacity in relation to land use ............................................................................................... 15

Table 3 Current shares (2017) by land use class ............................................................................................. 20

Table 4 Direct economic damage functions (flood depth) ............................................................................. 23

Table 5 Replacement cost of critical infrastructure ........................................................................................ 24

Table 4 Adaptation measures included in each alternative strategy ............................................................. 34

Table 5 Standards of service – Coastal defences and drainage infrastructure .............................................. 35

Table 6 Conditional failure probabilities ‐ Coastal defences and drainage infrastructure ............................. 35

Table 9 Proposed SLR scenarios ...................................................................................................................... 36

Table 10 Proposed increases in extreme rainfall scenarios .............................................................................. 36

List of figures

Figure 1 Georgetown lies on the Atlantic coast of Guyana .................................................................................. 1

Figure 2 Study focuses on Georgetown (the capital of Guyana) and surrounding area ................................... 4

Figure 3 Structured participatory approach to Identifying priority hazards ...................................................... 5

Figure 4 Past flood events in Guyana recorded since 1972 .................................................................................. 6

Figure 5 Basic framework of assessment ........................................................................................................... 8

Figure 6 Final DTM including highly resolved linear flood infrastructure. ........................................................... 9

Figure 7 Extreme value tidal levels ................................................................................................................... 10

Figure 8 Extreme Rainfall .................................................................................................................................. 11

Figure 9 Coastal protection is typically provided by conventional 'hard' seawalls and 'soft' mangrove

stands .................................................................................................................................................. 12

Figure 10 Coastal defence condition survey (ciria 2011) .................................................................................... 12

Figure 11 A view over the Demerara estuary looking east towards Georgetown ............................................. 13

Figure 12 A network of channels, pumps and sluices act to drain the flat coastal plains .................................. 13

Figure 13 The drainage channel network represented in the hazard analysis ................................................... 17

Figure 14 Present day ‐ Rainfall induced flood hazards ...................................................................................... 18

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

vii

Figure 15 Present day ‐ Coastal induced flood hazards ...................................................................................... 19

Figure 16 Present day (2017) land use map of study area ................................................................................. 20

Figure 17 Current population distribution across the study area ...................................................................... 21

Figure 18 Critical infrastructure within the study area: Mapped ....................................................................... 22

Figure 19 Critical infrastructure within the study area: By count ...................................................................... 22

Figure 20 Present day‐ Expected Annual Damage (spatial distribution) ............................................................ 25

Figure 21 Present day flood risk by sector and flood hazard – Economic risk ................................................... 27

Figure 22 Risk profile: Present day relationship between probability and economic damage .......................... 27

Figure 23 Event risk – Present day 1 in 100‐year return period storm .............................................................. 28

Figure 24 Present day ‐ People at risk – Expected annual number of people exposed to flooding .................. 29

Figure 25 Present day ‐ People at risk – Example map 1in100 return period rainfall ....................................... 30

Figure 26 Present day flood risk by land use and flood hazard – Critical infrastructure risk ............................ 31

Figure 27 Present day‐ Critical infrastructure at risk (spatial distribution ‐ 1in100 return period) ................... 31

Figure 28 Portfolio of flood management measures ......................................................................................... 33

Figure 29 Projected development hotspots under BAU, smart and feasible scenarios .................................... 37

Figure 30 Present and future land use maps of Georgetown under BAU, smart and feasible scenarios .......... 37

Figure 31 Relative changes in economic risk by sector: Present day ‐ 2050s (Baseline adaptation) ................ 39

Figure 32 Changes in economiuc risk by flood hazard: Present day – 2050s (A comparsion of altnernative

adpatation strategies) ......................................................................................................................... 39

Figure 33 Expected Annual Damage ‐ Spatial distribution ................................................................................. 40

Figure 34 Expected Annual Damages given alternative adaptations – By flood source .................................... 41

Figure 35 Expected Annual Damages given alternative adaptations – By sector .............................................. 42

Figure 36 Expected annual number of people exposed to flooding by 2050s (High climate, business as

usual future) ........................................................................................................................................ 43

Figure 37 Expected annual number of people exposed to flooding greater than 0.5m by 2050s .................... 43

Figure 38 Expected annual impact of physical damage and disruption to critical infrastructure (mUSD) ....... 44

Figure 38 Projected business as usual spending on core adaptation measures from 2020‐2040 .................... 46

Figure 39 Projected spending from 2020 to 2040 by type of adaptation measure and adaptation scenario .. 47

List of boxes

Box 1 2005 flood event ................................................................................................................................... 6

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

1

1 Introduction

Georgetown lies on the Atlantic coast of Guyana at the mouth of the Demerara River (Figure 1). Georgetown

is the capital and largest city in Guyana and, due to its location, is subject to a range of climate‐related hazards,

including coastal storms and rainfall. Since the major floods of 2005, significant investment has been targeted

towards improving sea and river defences as well as upgrading the extensive network of canals and drainage

infrastructure; but a significant adaptation deficit persists. Without further action, flood events will continue

to undermine economic development and as sea levels rise and rainfall patterns change, risks are likely to

increase. This study therefore focuses on developing an understanding of disaster and climate change risks

across the greater Georgetown area.

In recognition of this, the Government of Guyana (GOG) has sought to incorporate climate change

considerations into its development policies. For example, the Framework of the Green State Development

Strategy (GSDS) and Financing Mechanism in 2017 (Ministry of the Presidency, 2017) sets out ‘Guyana’s Vision

2030’ as:

“A green, inclusive and prosperous Guyana that provides a good quality of life for all its citizens based

on a sound education and social protection, low‐carbon resilient development, green and decent jobs,

economic opportunities, individual equality, justice, and political empowerment. Guyana serves as a

model of sustainable development and environmental security worldwide, demonstrating the

transition to a de‐carbonised and resource efficient economy that values and integrates the multi‐

ethnicity of our country and enhances the quality of life for all Guyanese.”

Appropriately adapting to climate related risks will be prerequisite to achieving this vision. Developing and

investing in natural and built coastal and fluvial infrastructure that responds to climate change will be, in turn,

of the highest priority.

Figure 1 Georgetown lies on the Atlantic coast of Guyana

Source: OCHA, accessed 2019

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

2

About this report

This report is one of a series of baseline studies for Georgetown, forming part of the Inter‐American

Development Bank’s (IDB) Emerging and Sustainable Cities Initiative (ESCI). The studies have been developed

under the IDB’s technical cooperation agreement with the Central Housing and Planning Authority (CH&PA),

“Climate Resilience Support for the Adequate Housing and Urban Accessibility Program in Georgetown,

Guyana” (GY‐T1137). The following three studies were produced for Georgetown:

● Climate Change Mitigation Assessment, to analyse Georgetown’s carbon footprint and help the city identify concrete options to reduce this.

● Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment (DRCA), to better understand the risks the city faces from natural hazards, including increasing hazardous risk due to climate change, and facilitate adequate planning to reduce these risks and the city’s vulnerability.

● Urban Growth Study, which assesses the urban footprint of the city and its dynamics under expected future trends, to inform and facilitate successful infrastructure and environmental planning at the city and regional level.

This report focuses on the DRCA. In doing so, two climate projections (a lower and higher projection) are

considered alongside three alternative adaptation scenarios (business as usual, feasible and smart). The

future changes in risk are then assessed for the 2030s and 2050s and the whole life costs of the measures

associated with adaptation estimated.

Objectives

The study objectives are to:

● Identify priority climate related hazards and risks (determined during the study to be coastal storm surge and rainfall induced flooding);

● Provide a strategic, broad‐scale, assessment associated with the priority risks for the present day and 2040s (viewed through the changing risk from 2030s and 2050s) taking account of climate change (Low and high), socio‐economic development (a central projection, Vivid, 2019) and alternative adaptation strategies (baseline, feasible and smart);

● Assess the associated adaptation investment (capital and operating) costs.

Structure of study and report

The report is structured as follows:

● Chapter 2 ‐ Priority climate related hazards: presents the qualitative stakeholder led process of identifying the flood hazards (coastal and rainfall) as the priority hazards to be assessed in more detail.

● Chapter 3 ‐ Present day flood risks: presents the analysis of present‐day hazards (including extreme value analysis of rainfall and tide levels), exposure and vulnerabilities.

● Chapter 4 – Future flood risks: presents the climate change and adaptation assumptions together with an assessment of the potential changes in flood risk by the 2030s and 2050s.

● Chapter 5 – Adaptation costs: presents an assessment of the whole life costs associated with the alternative adaptation scenarios and the supporting evidence.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

3

● Chapter 6 – Conclusions: presents a brief summary of key findings and recommendations for next steps.

A series of supporting reports have been produced during the study. The detailed analysis provided by these

reports are included in the following appendices:

● Appendix 1 Prioritization of hazards and risk.

● Appendix 2 Creation of a credible understanding of topography (DTM).

● Appendix 3 Extreme value analysis.

● Appendix 4 Defence standards and approach to modelling the inundation scenarios.

● Appendix 5 Long list of adaptation options.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

4

2 Priority climate related hazards and risks

2.1 Geographical setting

Guyana has a tropical climate and is generally hot and humid, though moderated by northeast trade winds

along its coast. There are two rainy seasons, the first from May to mid‐August, the second from December to

January, that lead to frequent flooding. Although Georgetown does not truly have a dry season with monthly

precipitation throughout the year typically above 60 millimetres. Guyana, however, lies south of the typical

tropical cyclone formation regions that drive hurricanes towards the Caribbean hence coastal flooding is driven

by storm surge.

Guyana’s physical landscape is diverse and vibrant. Inland, Guyana has one of the largest unspoiled rainforests

in South America, some parts of which are almost inaccessible by humans. Guyana’s coastline forms part of a

1,600km‐long coastal system dominated by mangrove forests and a network of mud banks that migrate north

from the mouth of the Amazon River in Brazil to the Orinoco in Venezuela (Anthony et al., 2010). This system

of complex mud banks is highly dynamic and exhibits significant variation on intra and inter year timescales.

This coastal system is increasingly being squeezed by sea level rise and land‐based development, increasing

Guyana’s exposure to coastal flooding and erosion. The coastal risks are not however confined to the

degradation of coastal ecosystems, but also impact social and economic wellbeing. Frequent flooding in the

past has had significant economic consequences.

Georgetown itself is located on Guyana's Atlantic coast on the east bank of Demerara River estuary (Figure 2).

The topography is typical of a coastal delta, flat and low‐lying (in many places lying significantly below high

tide levels). The coastal protection is provided by a combination of built seawalls and natural mangrove forests

complemented by a network of canals and kokers (sluices and pumps first developed by the Dutch) that act to

drain flood waters during heavy rainfall events.

Figure 2 Study focuses on Georgetown (the capital of Guyana) and surrounding area

Note: Urban population density from European Union Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL). LiDAR data available from the

Ministry of Agriculture for the area spanning in pink.

Source: Vivid Economics and Sayers and Partners

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

5

2.2 Priority hazards

The risks in Regions 3 and 4 (Essequibo Islands West Demerara and Demerara Mahaica) have been

prioritized through a participatory, qualitative, approach based on two workshops and the application of the

Hazard Assessment Matrix tool (a process summarised in Figure 3).

Figure 3 Structured participatory approach to Identifying priority hazards

Source: Sayers and Partners

The assessment identified a total of 22 relevant hazards and threats and enabled information to be

exchanges between attendees involved in two on‐going related studies (funded by European Development

Bank and the Caribbean Development Bank). The workshops were well attended and involved a range of in‐

country experts enabling the available quantitative information on different hazards (both historic and future

given climate change) to be combined with expert insights to develop a robust risk ranking as follows:

1. Pluvial flooding.

2. Coastal/tidal Flooding.

3. River Flooding.

4. Improper Solid Waste Management.

5. Water Pollution.

6. Oil/Chemical Spills.

7. Poor Infrastructure.

8. Tsunamis.

The priorities for further study established through this process (and discussed in detail in the following

chapters) reflect observational evidence that flooding is increasing in both frequency and significance in

Guyana (

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

6

Box 1 2005 flood event

In January 2005, extreme rainfall caused devastating flooding on the coastal lowlands, with many areas

remaining inundated for up to 3 weeks and water levels reaching chest height in many homes. Due to the

inability of the system to drain away the excess water quickly enough, water levels in the EDWC were

significantly above safe operating levels, weakening the dam and leaving it more vulnerable to

overtopping and a potential breach. Fortunately, the dam did not breach but the 2005 flood and other

floods since then have highlighted the vulnerability of the system to catastrophic failure. In summary, in

January 2005 over 1 m of rain fell, nearly 5 times the monthly average, with 65cm in just 5 days. The

extreme rainfall caused widespread flooding which affected almost half of Guyana’s population. Total

damages from the disaster are estimated to have been US$ 465 million or 59% of Guyana’s GDP for 2004.

Source: World Bank, 2013 Managing Flood Risk in Guyana The Conservancy Adaptation Project 2008‐2013

Figure 4).

A full description of the prioritisation process, those involved, and the qualitative scores for each hazard are

presented in Appendix 1.

Box 1 2005 flood event

In January 2005, extreme rainfall caused devastating flooding on the coastal lowlands, with many areas

remaining inundated for up to 3 weeks and water levels reaching chest height in many homes. Due to the

inability of the system to drain away the excess

water quickly enough, water levels in the EDWC

were significantly above safe operating levels,

weakening the dam and leaving it more

vulnerable to overtopping and a potential

breach. Fortunately, the dam did not breach but

the 2005 flood and other floods since then have

highlighted the vulnerability of the system to

catastrophic failure. In summary, in January

2005 over 1 m of rain fell, nearly 5 times the

monthly average, with 65cm in just 5 days. The

extreme rainfall caused widespread flooding

which affected almost half of Guyana’s

population. Total damages from the disaster are

estimated to have been US$ 465 million or 59%

of Guyana’s GDP for 2004.

Source: World Bank, 2013 Managing Flood Risk in Guyana The Conservancy Adaptation Project 2008‐2013

Figure 4 Flood events in Guyana recorded since 1972

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

7

Source: Inventory of the effects of disasters: https://www.desinventar.org/

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

8

3 Present day flood risk

3.1 Introduction

The assessment of flood risk requires the consideration of the three components of risk: hazard – a situation

with the potential to cause harm; exposure – to that hazard; and, vulnerability – the agreed means of valuing

the harm caused (Figure 5). To provide a credible assessment of the hazard a range of storm scenarios and

alternative defence system states (i.e. the conditional state of the Georgetown seawalls – breached or not –

and conveyance channels – flow restricted or not) are used to provide a probabilistic assessment of the flood

risk and an assessment of the Expected Annual Damage (EAD). The following sections elaborate each aspect

of this framework.

Figure 5 Basic framework of assessment

Source: Sayers and Partners, based on Sayers et al, 2014

3.2 Flood hazard

An appropriately reliable assessment of the probability of flooding is a prerequisite to the assessment of risk.

Achieving this relies upon several important inputs as introduced below.

Topography

To produce a suitable Digital Terrain Model (DTM) for this project, several steps were undertaken in ArcGIS

to generate outputs with enhanced accuracy for flood modelling. The approach uses two sources of DTM (i)

a freely available SRTM (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission) – 30m resolution grid and (ii) a high‐resolution

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) covering part of the study area at a 1m horizontal resolution and

resampled here to a 10m grid. To ensure a credible representation of the defence crest levels in the DTM

used for the flood modelling, the location of crests of the EDWC dam and the coastal defences were digitised

from the 1m DTM as a polyline1. The resulting integrated DTM is shown together with example defence

cross‐sections in

Figure 6. A more detailed discussion of the data used, and the associated processing is provided in Appendix

2.

1 Note: The harmonisation of the vertical datums is based on the assumption that Mean Sea Level (today) equates to 15.56mGD (Guyana Datum). The reference GD is taken from the Brass Datum plate on the Lighthouse, set at 17.41mGD. The feature used to set 0mGD is unknown to the authors.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

9

Figure 6 Final DTM including highly resolved linear flood infrastructure.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

10

Source: Sayers and Partners

Tidal levels

Astronomical tides in Guyana are diurnal with two high and two low tides each day in Georgetown. The tidal

range averages about 2m with the tidal influence extending a considerable distance inland (as far as 80 km

to 100 km inland along the Demerara River under surge conditions, Daniel 2001). An extreme value analysis

of the annual maxima water level data from Georgetown Tide Gauge (located at the mouth of the Demerara)

using an extreme value Gumbel distribution is presented in Figure 7. A more detailed discussion of the data

and the associated processing is provided in Appendix 3.

Figure 7 Extreme value tidal levels

Note: Top: Annual maxima records from the Georgetown tide gauge. Bottom: Extreme value distribution

Source: Sayers and Partners

Coastal wind‐waves

The Guyana coastline is characterized by relatively mild meteorological and hydrodynamic conditions; winds

are generally from between northeast and east (Trade Winds) and vary between 5 and 10 m/s (Van Ledden

et al., 2009). The wave energy incident to the shoreline is limited by the large continental shelf and network

of mud banks. Wave overtopping alone typically results in more localized flooding (in comparison to a breach

or major surge event) but does act to increase the chance of breach (through scour and structural damage to

the front, crest or rear face of the coastal embankment or seawall).

Rainfall

The annual meridional migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) northward generally brings

heavy rainfall between mid‐April and the end of July, with a major peak rainfall in June. During the

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

11

southward migration of the ITCZ, a second wet season is observed between mid‐November and the end of

January with peak rainfall in December. Large interannual variability in rainfall is driven by El Nino (typically

higher rainfall) /La Nina (typically lower rainfall) cycles; although this cycle is not a ‘perfect’ indicator of the

likely seasonal rainfall, for example, during the mild El Nino year 2004–2005, rainfall was 49% above normal

(Rama Rao et al., 2012).

In the absence of well‐conditioned observed rainfall data, the daily rainfall depth estimates from the CHIRPS

(Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station data) dataset (covering the period 1981‐2018) is

used to support the extreme value analysis. The annual maxima values from the CHIRPS dataset for

Georgetown together with the Gumbel extreme value analysis are presented in Figure 8. A more detailed

discussion of the data and the associated processing is provided in Appendix 3.

Figure 8 Extreme Rainfall

Note: Top: Annual maxima for Georgetown based on CHIRPS. Bottom: Extreme value distribution

Source: Sayers and Partners

Existing defence and drainage standards and condition

Flood protection is provided by a combination of a seawalls, mangrove forests, wharf walls and a network of

drainage channels, pumps and sluices. The standard of protection typically provided varies from around

1in100 year return on the open coast, to 1in50 year return on the tidal Demerara and around 1in25 year

drainage standard in urban centre of Georgetown (less elsewhere). These protection systems are

introduced in turn below with a more detailed discussion provided in Appendix 4.

Open coast: Protection from coastal flooding is provided by a combination of conventional sea defences

(with a mix of concrete and rip‐rap revetments) fronted by a muddy foreshore and mangrove forest (

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

12

Figure 9). Sediment control structures (groynes) and the mangrove forests help to stabilise the morphology

and attenuate wave energy. The systems of mud banks are also crucial elements of the coastal defence

system. The latest Sea Defence Condition Survey (Work Services Group 2016) highlights some sections of

defence in ‘critical’ or ‘poor’ condition reflecting the difficulties in securing investment to appropriately

maintain the existing defences (Figure 10).

Figure 9 Coastal protection is typically provided by conventional 'hard' seawalls and 'soft' mangrove stands

Left: The new sea defence being constructed at Cornelia Ida (Region 3). Right: The fronting mangrove stands backed by

old sea walls (Region 4).

Source: Jonathan McCue, 2019

Figure 10 Coastal defence condition survey (ciria 2011)

Source: Work Services Group Sea Defence Structures Survey Map (2011)

Tidal reaches of the Demerara River: On the east bank the commercial wharves provide a de facto defence

line (

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

13

Figure 11). On the west bank mangrove forests and natural banks continue to provide the dominate

boundary together with some localised protection structures.

Figure 11 A view over the Demerara River mouth looking east towards Georgetown

Source: Jonathan McCue

Land drainage: The drainage around the coastal plain of Guyana forms a series of larger primary channels

fed by secondary channels (often the relics of agricultural drainage) on a regular rectangular grid system

(Pelling, 1999). This network of channels, pumps and sluices acts to drain flood waters to the sea. In many

cases the drainage capacity of this network is unable to accommodate daily rainfall events that exceed a 25‐

year return period (i.e. a daily rainfall depth of 275 mm). The drainage capacity is not however standard

across the study area. This variation reflects several factors, including both the past investment in drainage

infrastructure and the effort devoted to the on‐going maintenance of that infrastructure (including debris

clearance and conveyance management).

Figure 12 A network of channels, pumps and sluices act to drain the flat coastal plains

Far left: Sluice (Cornelia Ida, Region 3), Left: Ogle sluice Right: coast parallel channel (Stewartville, Region 3), Georgetown, Far right:

Heavy vegetation channel near Stabroek Market

Source: Jonathan McCue and Paul Sayers

The Conservancy Dam: The EDWC dam (located to the east of the Demerara) is designed to intercept and

retain flows from the area to the south of the coastal plain. The performance of the dam is outside the

scope of this study but is included within the DTM (with a crest level of between 18 and 18.5m GD).

Combined storm scenarios and system states

Based on the extreme value analysis a set of 13 rainfall and coastal flood scenarios are used to represent the

storm scenarios (Table 1). To reflect the possibility of a significant rainfall event coinciding with a high tide

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

14

event, several joint events are included. In the absence of well‐conditioned observed data, a formal joint

probability analysis has not been possible but is recommended for further study.

Table 1 Storm scenarios: coast and rainfall

Coastal extremes Rainfall extremes

Joint return

period (years)

Return period

(years)

Tidal level

Demerara

(m GD)

Tidal Level

Open

Coast

(m GD)

Return

period

(years)

Rainfall

(mm/day)

2 17.08 17.28 2

10 17.34 17.54 10

50 17.6 17.8 50

100 17.72 17.92 100

200* 17.98 18.18 200

Low tide 14.79 14.79 2 130.8 2

Low tide 14.79 14.79 10 222.5 10

Low tide 14.79 14.79 25 274.8 25

Low tide 14.79 14.79 100 353.8 100

Low tide 14.79 14.79 200 393.3 200

2 17.08 17.28 2 130.8 2

100 17.72 17.92 2 353.8 150

2 17.08 17.28 100 130.8 150

Source: Sayers and Partners and Vivid Economics

To provide a whole system probabilistic framing of the hazard analysis, each storm scenario is associated

with the following conditional system states:

Coastal defence system states: In representing the coastal defences, two defence states are considered:

● No breach – in this case it is assumed that the backshore defences remain intact and provide protection up to their notional design standard. For events exceeding this, the defences are overtopped but remain structurally intact.

● Breach – in this case it is assumed that the backshore defences are breached at the weakest locations (defined where the present day condition of the defence is assessed to be ‘critical’ – Figure 10). Based on this reasoning, three locations along the coast east of the Demerara and one location to the west of the Demerara are assumed to breach. The breach width is assumed to be 20% of the length of the defence section (with a minimum breach length of 100m) and an invert level determined by the natural ground level (although considered reasonable, see Sayers et al, 2001, Hall et al, 2004, specific breach initiation and growth studies have not been possible here).

Tidal defence system state: Given the absence of significant lengths of raised defences, no consideration is

given to the potential for a breach, although the tidal walls may be overtopped.

Drainage system states: Two possible system states are considered:

● Unrestricted function – in this case, the system is operating to capacity and linked to the land use categories (with greater standards provided in more established urban and industrial settings) as set out in Table 1.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

15

● Restricted function – Failure of the drainage system is considered in terms of a reduced capacity that may arise due to blockage (of the channel itself or sluice due to vegetation or anthropogenic debris) or operational failure (e.g. failure of a pump or failure of a sluice to open or close). For example, during the 2005 floods, it is estimated that the canal system functioned at 60% capacity (Muntz, 2005). ‘Failure’ is therefore represented through a reduction in the drainage capacity (Table 2).

Table 2 Drainage capacity in relation to land use

Land use category

From CE3

Drainage capacity

(present day – expressed in return period, years)

Unrestricted Restricted

Residential areas 25 10

Predominantly Industrial 10 2

Predominantly commercial 10 2

All other areas 10 2 Note: Unrestricted refers to the standard provided assuming the channels and associated pumps and sluice perform as designed

(where they exist). Restricted refers to the cause of a partial loss in conveyance due to poor channel management, or a pump or

sluice failure.

Source: Sayers and Partners and Vivid Economics

Flood hazard mapping

The flood hazard analysis considers both the storm conditions (rainfall and coastal surge) as well as

representation of the system states (breach or not, blocked or not). Given the strategic nature of the

analysis, representation of each individual sluice and pump is not appropriate but where possible insights

from the recent localized model studies by JICA (2017) and TUD (Remmers et al., 2016) – studies that have

focused on Georgetown only – have been used to inform the inundation analysis.

A cell‐based routine is used to map the flood extent and depth across the floodplain in a way that builds

upon approaches typically used as part of larger scale analysis (e.g. Rodda, 2005). These are capable of using

the high resolution of the mosaic DTM (see earlier) and characterising the complexity of the channel network

and coastal defences. Within this approach, it is assumed that rainfall directly on the land surface is first

conveyed to the drainage network before spilling on to the floodplain; a reasonable assumption given the

extensive nature of the network (

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

16

Figure 13). Flood waters overtopping the crest level of the coastal or tidal defences (or in the case of a

breach, the invert level of the breach) provide the coastal boundary to the model. Propagation inland of

coastal flooding is then limited by the roughness of the floodplain (through a Manning’s function that

accounts for the various inland cover and use).

A more detailed description of the approach to the flood hazard mapping is provided in Appendix 4.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

17

Figure 13 The drainage channel network represented in the hazard analysis

Note: Blue: Previously mapped channels. Green: Channels derived here from the DTM

Source: Sayers and Partners, Vivid Economics

Selected present day hazard maps are presented in the following figures. Figure 14 Present day ‐ Rainfall

induced flood hazardsFigure 14 shows the flood extent and depth associated with a 1in100 year return

period rainfall event2. Two sets of hazards maps are provided in response to this storm event. The first

considers the drainage network performs as designed (i.e. an unrestricted system state) and the second

considers the impact of a partial loss of conveyance (i.e. the restricted system state).

2 A 1in100 return period expresses the expected number of events that will exceed this value in any given 100 years, but it is easily possible that within any given 100 year period an event that exceeds this value may not occur at all, or else it may occur more than once – See Sayers et al, 2015.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

18

Figure 14 Present day ‐ Rainfall induced flood hazards

Note: Example output hazard mapping: Left: 1in100 return period present‐day rainfall assuming the drainage network, pumps and

sluices perform as designed. Right: the same storm event, but assuming conveyance is partially restricted (due, for example, to poor

channel management, pump or sluice failure).

Source: Sayers and Partners and Vivid Economics

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

19

Figure 15 Present day ‐ Coastal induced flood hazards

Note: Example output hazard mapping: Left: 1in50 return period storm event given the present‐day climate and three defence

breaches (of the critical condition defences). All other defences remain structural intact with limited (no) overtopping. Right: 1in100

return period storm event given the present‐day climate and three defence breaches, but with the added inflows from overtopping

of other defences.

Source: Sayers and Partners and Vivid Economics

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

20

3.3 Flood exposure

Flood exposure is used here to refer to three aspects of the study area that may be subject to flooding.:

Economic (Land use) exposure

Error! Reference source not found.Error! Reference source not found. shows the spatial pattern of

commercial, industrial and residential land use and highlights the clusters of development around central

Georgetown and along the East Bank and south along the bank of the Demerara River. Agricultural land

buffers these developments and accounts for 20% of land use within the study area and predominantly

urban areas 6% (with exposure highest along the coast, where urban development is most dense) ‐ Table 3.

Figure 16 Present day (2017) land use map of study area

Table 3 Current shares (2017) by land use class

Land use class Area (Ha) Proportion

Dense vegetation and forests 85,535 32.6%

Agriculture 52,589 20.0%

Wetlands and swamps 52,103 19.8%

Sparse vegetation 34,411 13.1%

Predominantly residential 15,562 5.9%

Water bodies 9,277 3.5%

Shrublands and sandy areas 8,585 3.3%

Urban greenspaces 3,127 1.2%

Mangroves 731 0.3%

Predominantly industrial 477 0.2%

CBD and predominantly commercial 166 0.1%

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

21

People exposure

Around 140,000 people live in the study area with the majority living in Central Georgetown and its suburbs

(~85,000 people or 66% of the total population) ‐ Error! Reference source not found.. This mirrors the

distribution of critical infrastructure and highlights the high exposure here. The East Coast is the next most

populous region with 28,000 people or 22% of the total population. There are considerably less people west

of the Demerara and in the Timehri region, and very few living in the forests and wetlands (as expected). As

expected, the population density is also greatest in Central Georgetown (~14 people per hectare) and less

dense elsewhere.

Figure 17 Current population distribution across the study area

Source: Vivid Economics

Critical infrastructure exposure

Infrastructure that provides critical socioeconomic services such as health care, education and emergency

response are largely located within Georgetown itself and the immediate surroundings (Error! Reference

source not found.). This includes hospitals, health clinics, schools, police stations, fire stations, bus stations,

ferry terminals, airports with the majority of critical infrastructure within Central Georgetown and its

suburbs 3.

Figure 19 provides a summary count of the critical infrastructures within the study area. Within central

Georgetown and its suburbs, infrastructure is most densely located in the administrative boundary of

Georgetown, especially in the North‐western corner and along the southern border. This includes 41

schools, 20 hospitals, 18 bus stations, 8 police stations, 7 health clinics and 4 fire stations.4 It also includes

the ferry terminal (Stelling) between Georgetown and Vreed‐en‐Hoop, the Eugene F. Correira International

Airport (formerly Ogle) Airport, the National Park Stadium and Providence Stadium and the Camp Ayanganna

military base. Outside of the administrative boundary of Georgetown, critical infrastructure is mostly located

3 In the context of Georgetown, water, electricity and waste infrastructure are also critical to the provision of basic services and susceptible to flood damage. However, we were unable to include these assets within our analysis as no consolidated data sources exist mapping their location across Georgetown (or our wider study area). We also include Providence Stadium as well as the Camp Ayanganna Army Barracks. 4 While Guyana has only one National Referral Hospital, we use a wider definition of hospital as per Open Street Maps (2019) criteria. Hospitals mark ‘institutions for health care providing treatment by specialised staff and equipment, and typically providing nursing care for longer‐term patient stays.’ Health clinics mark ‘medical centres with doctors for outpatient care’.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Forests andwetlands

West ofDemerara

CentralGeorgetown and

suburbs

East Coast Timehri region

Bui

lt ar

ea d

ensi

ty (

peop

le p

er h

a)

Pop

ulat

ion

(tho

usan

ds)

Currentpopulation

Built area density

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

22

along the Demerara river, following the East Bank Highway. This includes a series of schools as well as a few

police stations and hospitals. It also includes Providence Stadium, located 10 minutes by car from central

Georgetown. Along the East coast the infrastructure become more dispersed (including 20 schools, 4

hospitals, 4 bus stations, 4 police stations and 1 health clinic). West of the Demerara infrastructure services

are less developed (with 17 schools, 3 police stations, 1 hospital and 1 fire station). The Leonora Stadium is in

the North Western corner of the region.

Figure 18 Critical infrastructure within the study area: Mapped

Note: Critical infrastructure in the Timehri region is excluded due to the lack of high‐resolution satellite imagery

Figure 19 Critical infrastructure within the study area: By count

2

25

9 6

25

2

15

80

2

1

Airport Bus stations Health clinics

Fire stations Hospitals* Military barracks

Police stations Schools Stadiums

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

23

3.4 Flood vulnerability

Vulnerability reflects the potential for a given receptor (such as a residential property) to experience harm

when exposed to a flood. To provide a quantified estimate of vulnerability three perspectives are used here:

Economic vulnerability

A damage function is used to relate the characteristics of the hazard (defined in terms of flood depth) to an

economic damage by land use class. The economic damage function used is based on the Guyana country

functions provided in the Global flood depth‐damage functions database (JRC, 2017) as summarised in Table

4.

Table 4 Direct economic damage functions (flood depth)

Hazard indicator USD / m2

Flood Depth (m) Residential Commercial Industrial Agriculture

0 ‐ ‐ ‐ ‐

0.5 18 135 65 0.01

1 26 186 87 0.01

1.5 31 204 93 0.02

2 35 219 98 0.02

3 36 221 98 0.02

Note: Uplifted from the base date of the JRC database (2010) to 2018 prices using IMF consumer price index (CPI) growth

statistics. The values shown are per m2 of land and are adjusted to account for the density of buildings on residential,

commercial and industrial land in Georgetown (based on the land use inventory produced under the Urban Growth

Study component of this project). The JRC vulnerability functions have been used in preference to construction type

damage functions (such as those provided in HAZUS or CAPRA). This reflects the lack of data on building construction

type across the study area. Although available in some areas (within the high‐resolution land use explored in CE3) it is

not possible to provide a credible generalization of this data. Therefore, the more aggregated damage functions

provided by JRC have been used.

Source: Sayers and Partners and Vivid Economics, based on JRC, 2017

People vulnerability

People vulnerability is explored through two counts. The first considered the number of people exposed to

flooding of any depth and the second those exposed to flood depths greater than 0.5m. No distinction is

may by social vulnerability (income, health, or social networks etc). This reflects the lack of information on

the detailed demographics and social vulnerabilities (e.g. as used in the neighbourhood flood vulnerability

index, Sayers et al, 2017) but also the well‐recognised difficulties in monetising the impact of a flood on the

physical and mental well‐being of an individual or group of individuals.

Critical infrastructure vulnerability

The economic damage incurred when critical infrastructure is flooded reflects the impact of the lost service

and the cost of replacing / reinstating those services. These impacts are valued here through two proxy

methods. The first provides an evaluation of the replacement value of each critical infrastructure asset

drawn from a variety of local and regional sources (Table 7). This assessment highlights the significant asset

based within the study area with a total value of around ~450m USD. The second is through a multiplier

applied to the direct economic damages to account for the physical infrastructure damage and disruption

that may be caused when an asset is flooded. This is difficult to assess directly (due to the highly contextual

nature of the damage and disruption). The assessment here assumes such damages add a further 50% to

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

24

the associated of the direct economic damage (above) 5. In the case of a hospital or clinic, for example, this

includes the reduction in the provision of medical services in the local area and repairing the building. This is

only a proxy of course so the basic counts of the number and type of critical infrastructure are also

presented.

Table 5 Replacement cost of critical infrastructure

Type of asset Replacement cost (2018 USD) Source

Hospital 1,747,522 IDB (2015)

Clinic 188,777 IDB (2015)

Ogle airport 28,885,501 Starbroek News (2018)

Cheddi Jagan airport 150,000,000 MOPI (2018)

Bus station 2,048,852 MOPI (2017)

Ferry terminal 1,240,225 MOPI, Transport and Harbours Dept (2017)

Fire station 91,378 Guyana Chronicle (2011)

Police station 73,321 Guyana Chronicle (2011)

School 1,594,255 GoG (2017)

Stadium 37,368,633 ESPN (2019)

Note: All figures are converted to 2018 USD using World Bank official exchange rate and US CPI data.

5 Physical infrastructure damage and associated disruption is typically estimated using a 1.1‐1.8 uplift applied to the direct economic damages. 1.5 is applied here to yield the total damages after Sayers et al, 2018. A study for Paramaribo, the consultant ERM Total Damage/Asset Damage ratio ranges between 1.05 and 1.71 that provides some supporting evidence (although no supporting reference for this can be found). It is noted however noted the assessment of the damage to and from critical infrastructure is highly contextual.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

25

3.5 Flood risks

Present day ‐ Economic risk

Expected annual damage

Today the EAD6 from flooding across Georgetown and the surrounding area is around 5mUSD and

dominated by residential and commercial sectors exposed to surface water flooding (Figure 20).

Figure 20 Present day‐ Expected Annual Damage (spatial distribution)

Note: EAD by 30m gird

Source: Sayers and Partners

Coastal and tidal flood risk is much less (~1.2m USD compared to 3.8m USD from surface water) and

predominantly impacts the commercial and industrial sectors with the economic damage to the agricultural

sector small in comparison to other sectors (a function of the low value of the agricultural damage rather

than a lower exposure) ‐ see

6 EAD represents an integration of the relationship between annual probability of occurrence of a flood (taking account of probability of storm and conditional probability of the defence system states – see Table 6) and the associated consequences

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

26

Figure 21.

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

27

Figure 21 Present day flood risk by sector and flood hazard – Economic risk

Source: Sayers and Partners

Risk profile: Economic

To provide insight into the risk profile, Figure 22 sets out the relationship between probability and the conditional economic damage. This highlights the rapid increase in damage as the severity of the storm event exceeds around a return period of around 1in25 years. The increase in damage is much less with higher return periods. This is because floods that exceed a 1in200 year return period impact a significant area. The probable maximum damage, reflecting combined severe coastal and rainfall storm (with a joint return of 1in1000 years7 ). The damage associated with a 1in100 year return period coastal storm (taking account of conditional probability of a breach in the coastal defences) is estimated around 70mUSD with an equivalent rainfall event (taking account of conditional probability of loss of conveyance due to blockage or pump failure) is significantly higher (around 90m USD).

Figure 22 Risk profile: Present day relationship between probability and economic damage

7 As highlighted in Appendix 3 the coincidence record length is limited. This makes it difficult to determine extreme joint probability events from the data directly, so care is needed when considered such extreme events.

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

All sectors Residential Agricultural Industrial Commercial

Expected Annual Dam

age (USD

m)

Coastal Rainfall All sources

y = 67.97ln(x) ‐ 208.39R² = 0.99

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200

Conditional economic dam

age (m

USD

)

Return Period (years)

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

28

The spatial distribution of damage for the 1in100 event is provided Figure 23 and hot spots of damage in the city of Georgetown and along the commercial areas near the mouth of Demerara. The areas immediately in the lee of those sea defences assessed to be in a ‘critical’ condition (assumed here to be the location of a breach, if it occurs) experience significant damage.

Figure 23 Event risk – Present day 1 in 100‐year return period storm

Source: Sayers and Partners

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

29

Present day ‐ People risk

The expected annual number of people exposed to flooding is given in Figure 24. The expected annual number of people flooded is ~28,400 people. This is primarily in response to rainfall events (~26,000) with significantly fewer experiencing coastal flooding (~2,400). The severity of the flooding at the coast is however typically greater, with most people exposed to flooding experiencing flood depths that exceed 0.5m. Although the absolute number of people experiencing flood depths greater than 0.5m in response to a rainfall storms is much higher, the relative proportion is much less than during coastal storms.

Figure 24 Present day ‐ People at risk – Expected annual number of people exposed to flooding

Source: Sayers and Partners and Vivid Economics

The spatial distribution of the people exposed to an annual probability of flooding greater than 0.01 (i.e. a

return period of 1in100 years) is shown in

Figure 26 Present day flood risk by land use and flood hazard – Critical infrastructure risk

Figure 27 Present day‐ Critical infrastructure at risk (spatial distribution ‐ 1in100 return period)

0.0

5.0

10.0

15.0

20.0

25.0

30.0

Any flood depth Flood depths >0.5m

Expected annual number of

peo

ple flooded

(000s)

Coastal Rainfall All sources

32

46

5868

0

20

40

60

80

25 100 150 200

Number of sites affected

Return Period (years)

Total number affectedairportbus_stationclinicfire_stationhospitalmilitarypolice

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

30

Top: Critical infrastructure impacted by 1in100 year rainfall event: Bottom: Critical infrastructure impacted by 1in100 year coastal

event. Source: Sayers and Partners

. The figure highlights a concentration of people at risk at the mouth of the Demerara and along its east bank (as expected). Under such extreme conditions ~375,000 people may be flooded during rainfall events and ~125,000 during coastal storms (if associated with a breach).

Figure 25 Present day ‐ People at risk – Example map 1in100 return period rainfall

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

31

Source: Sayers and Partners

Present day ‐ Critical infrastructure risk

Significant critical infrastructure is exposed to flooding with the number of police stations, bus stations and

schools increasingly significantly with the severity of the storm (Figure 26). As expected, most critical

infrastructure risks are within Georgetown and its immediate surrounding (Figure 27).

Figure 26 Present day flood risk by land use and flood hazard – Critical infrastructure risk

Figure 27 Present day‐ Critical infrastructure at risk (spatial distribution ‐ 1in100 return period)

32

46

5868

0

20

40

60

80

25 100 150 200

Number of sites affected

Return Period (years)

Total number affectedairportbus_stationclinicfire_stationhospitalmilitarypolice

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

32

Top: Critical infrastructure impacted by 1in100 year rainfall event: Bottom: Critical infrastructure impacted by 1in100 year coastal

event. Source: Sayers and Partners

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

33

4 Future flood risk

4.1 Alternative adaptation measures and strategies

A long list of adaptation measures was first developed through a thorough consultation process with key

stakeholders. From this, a shortlist of the most promising options was identified, based on the economic,

environmental and technical constraints and opportunities in Regions 3 and 4. This process is elaborated in

more detail in Appendix 5. The resulting shortlist is shown in Figure 28.

Figure 28 Portfolio of flood management measures

Note: Short list of measures identified from the stakeholder lead long listing process (Appendix 4) reflects a portfolio

approach widely recognised as a perquisite for good flood risk management, Sayers et al, 2014.

Source: Sayers and Partners

These individual measures form the basis for the three alternative approaches to flood risk management as

follows:

● Business‐as‐usual: Considers the adaptation measures that would be implemented assuming a continuation of current approaches and similar levels of investment as today.

● Feasible adaptation: Assumes the adaptation effort is increased with more investment directed towards maintaining existing natural (‘soft’) and conventional (‘hard’) infrastructure and appropriately plan new infrastructure (taking account of climate change). It is also assumed flood hazards have a greater influence for spatial planning and building regulation than they do today.

● Smart adaptation: Assumes climate change and long‐term resilience are central consideration managing flood risks. This means significant resources are devoted to soft and hard flood protection infrastructure and, importantly, spatial planning choices provide space for the natural dynamics of the coast where possible and avoid development in areas exposed to the highest chance of flooding in the future.

A summary narrative of the individual adaptation actions contributing to each alternative strategy is given in

Table 6. Details of the assumed standards and conditional breach and blockage failure probabilities are given

in Table 76 to 8

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

34

Table 6 Adaptation measures included in each alternative strategy

Adaptation measure Business‐as‐Usual (BAU) Feasible Smart

Soft infrastructure

Mangroves and

sediment control

structures

Conservation areas are maintained but not

extended and groynes remain in poor condition

with limited influence on morphology. Little

protection provided to backshore defences.

Active management and targeted extension of

conservation areas. This acts to reduce the

chance of breach (where opportunities are

greatest).

Further extension of mangrove forest areas and

control structures act to improve the standard of

protection.

Hard infrastructure

Coastal and tidal

defence

Present day standards reduce with climate

change. No significant improvement in defence

condition, ‘Critical’ condition defences have an

increased chance of breaching.

Present day standards reduce with climate

change, but enhanced maintenance leads to

some improvement in defence condition

(reducing the chance of a breach).

Defence standards are raised (through a

combination of conventional and nature‐based

defences) to 1in100 years and their condition

improved (reducing the chance of a breach).

Hard infrastructure

Drainage infrastructure

Drainage capacity continues to be constrained by

channel and pump capacity as well as

anthropogenic debris and vegetation. The chance

of blockage or pump failure is high.

Improved channel management and

pump/sluice maintenance (and targeted

replacement) improve the conveyance

capacity in urban areas. The chance of a

blockage and/or pump is reduced.

Further improvements to conveyance and

maintenance improve standards in urban and

commercial areas (reducing the chance of blockage

and pump failure).

Catchment

management*

All strategies assume the upstream catchment remains unaltered and the flows in the Demerara remain unchanged with climate change (an assumption

that relies on the maintaining the existing forest cover)

Spatial planning*/** Urban growth takes place with no consideration

of flood risk ‐

Urban growth takes place with some

consideration of flood risks, seeks to avoid

those areas where present day flood hazard

during the 1in100 year event > 0.6m. A no

new development buffer is maintained of

100m in tidal areas and 500m at the coast.

Urban growth takes place with some consideration

of flood risks, seeks to avoid all areas exposed

during a 1in100 year coastal event and a pluvial

flood hazard of >0.3m. A no new development

buffer is maintained of 200m in tidal areas and

1000m at the coast.

Forecasting and

warning*

Improved forecasting and warning to support Disaster Risk Management is required across all the strategies and the need to invest in improved systems is

a clear recommendation from the stakeholder workshops. The associated costs and risk reduction however are not quantified here.

Building resilience * Appropriately rising threshold levels to reflect the 1in100 year flood level (mGD) plus a freeboard allowance and the updating building regulations to

encourage resilient designs.

Supporting disaster risk

management, climate

adaptation and social

resilience*

Institutional change and regulatory responsibility, asset management, mangrove management and monitoring and insurance are all important issues that

will need to be addressed going forward are not the focus here. It is however assumed that improvements in asset monitoring enable better targeting of

investment in the feasible and smart strategies yielding some efficiency saving. Also developing social resilience requires actions beyond those listed

above, including specific actions that address the needs of vulnerable individuals and groups. This will rely upon developing long term community

connections and cohesion (Particip 2018). Achieving this is a difficult and complex, requiring community engagement and integrated planning. These

actions are not directly focused on in this report but will be improved aspects of further integrated planning processes as identified by Particip (2018).

Note: * indicates not included in adaptation cost estimates. ** See further discussion in Section 4.2. Source: Sayers and Partners

Georgetown, Guyana: Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

35

Table 7 Standards of service – Coastal defences and drainage infrastructure

Individual measure Alternative adaptation strategies

Baseline strategy Feasible Smart

Mangroves and sediment control structures

Open coast: As now Limited extension and

improvement

Further

extension and improvement

Tidal river: As now Limited extension and

improvement

Further

extension and improvement

Open coast defences standard of protection (years)

East frontage: 1in50 1in50 1in100

West frontage: 1in50 1in50 1in100

Tidal defence standard of protection (years)

East bank: Direct from DTM Min 1in50 Min 1in100

West bank: Direct from DTM Min 1in50 Min 1in100

Drainage system (capacity by land use)

Residential 1in25 1in25 1in25

Agricultural 1in10 1in10 1in25

Commercial 1in10 1in25 1in25

Note: See Appendix 4 for further detail

Source: Sayers and Partners