From the Real to the Colón The History of Money in Costa Rica · The name “colón” was...

Transcript of From the Real to the Colón The History of Money in Costa Rica · The name “colón” was...

/MBCCR

@museosbccr

/museosbccr

While from the 1860s until the early decades of the twentieth century sev-eral banks issued banknotes, since 1950, the Central Bank of Costa Rica (Banco Central de Costa Rica) is the only entity authorized to issue coins and banknotes.

The name of Costa Rica’s coin changed throughout history. From the silver real and gold escudo– inherited from the Spanish monetary system- it passed in 1863 to the establishment of a unique name for the currency, the peso, under a decimal system divided into one hundred parts called centavos. Finally, in 1896, the “colón” was established as the monetary unit divided into one hundred parts called

“céntimos” 20 pesos, gold, Costa Rica, 1873.

50 pesos, Anglo Costa Rican Bank (Banco Anglo Costarricense), 1864.

500 colones, Central Bank of Costa Rica (Banco Central de Costa Rica), 1951. In recent years, technological change is making the traditional concept of the coin disappear replacing it with so-called “plastic money”, consisting of debit and credit cards and electronic transactions with which many of the

economic activities of purchasing and selling goods and services are per-formed. Thus, it is possible that the coins and banknotes we use increasingly less often today could come to disappear and become the treasures of tomorrow.

The name “colón” was assigned to the Costa Rican coin in honor of Christopher Columbus because, in 1892, the Fourth Centenary of the

“discovery of America” was celebrated.

20 colones, gold, Costa Rica, 1899.

Level 1Museum of Numismatics

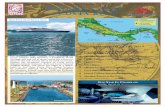

From the Real to the ColónThe History of Money in Costa Rica

Learn more about the Museums of the Central Bank of Costa Rica at: www.museodelbancocentral.orgPhone: 2243-4202E-mail: [email protected]

During the nineteenth century there was a constant issuance of coins however, the economic development of the coun-try required increasing amounts of cur-rency and the mint could not cope with the demand, so that coins of a colonial ori-gin and other American States continued to circulate along with the national coin. Many of these were allowed or autho-rized for circulation by the Government upon stamping a seal (counterstamp).

Similarly, in1858appearedthefirstbank called the National Bank of Costa Rica (Banco Nacional de Costa Rica) with the power to issue banknotes and, while its doors closed a year later, it was the

beginning of the formation of a num-ber of banks, especially from the 1860s, which issued banknotes and towards the end of the nineteenth century, led to the consolidation of the use of paper money.

With the independence of Central America proclaimed in 1821, one of the firstconcernsofCostaRicawastoissueits own coin and, although the Spanish monetary system continued to be used as abasis,in1825thefirstcoinsweremanu-factured and issued in a provisional mint. In 1828, a permanent mint was founded that would produce the majority of Costa Rican coins between 1829 and 1949, the year in which it closed.

The history of metallic coins and other means of exchange in the ter-ritory that today is Costa Rica begins with the arrival in the early sixteenth century of the Spaniards. Indigenous societies did not use coins for trans-actions but rather resorted to barter or exchange.

The Spaniards imposed a new spa-tial planning, political, economic, cul-tural and social order and a monetary system based on the use of silver and

gold coins. There were the following denominations: silver reales in differ-ent values (¼, ½, 1, 2, 4, 8) and gold escudos (¼, ½, 1, 2, 4, 8). Their shape could be circular or irregular (called macuquinas). Between the late six-teenth and early nineteenth centuries these were the coins that circulated in Costa Rica, which came from different parts of the Spanish Empire through trade and the payment of civil and ecclesiasticofficialssinceCostaRicahad no mint.

8 reales, silver, Mexico, 1734. 1 real, silver, Potosi, 1768. Macuquina.2 escudos, gold, Costa Rica, 1855. 10 pesos, National Bank of Costa Rica (Banco

Nacional de Costa Rica), 1858.½ real, silver, Costa Rica, 1842.8 reales, silver, Costa Rica, 1841. Counterstamp on 8 reales, silver, Nueva Guatemala, 1825.

The shortage of low denomination coins resulted in that, by the 1840s, coffee boletos -tokens used on coffee farms as a private currency- emerged to pay the workers’ wages, a mechanism that was later in the twentieth century used mainly in banana and commercial activities.

½ escudo, gold, Costa Rica, 1825.8 escudos, gold, Costa Rica, 1828

Coffee tokensJuan Rafael Mora Porras, ½ real, bronze.Ceferino Fernández, 10 céntimos, cupronickel.

From the Real to the ColónHistory of Money in Costa Rica