Freedom of Speech: The King vs John Peter Zenger...Freedom of Speech: The King vs John Peter Zenger...

Transcript of Freedom of Speech: The King vs John Peter Zenger...Freedom of Speech: The King vs John Peter Zenger...

) wife.5

i offe wa

I d t h e lHenryJ

/[ore wa\t <

. 3ill and;

,MorEKT

fjj

•H:i-fif;HH.

Freedom of Speech:The King vs John Peter Zenger

Richard Cicale examines the Zenger trial and the affect it had on freedom of the press in America

NEW-YORK,

jHans Hoi-;sire pin-.;sferthe*:

aid.

|d queeftiWear as

nje, More jWas •;•;of 1

JJuly 15||

Rafter-|e.;faith;"|

Sjfcblicservant

IN THE UNITED STATES, the conceptof freedom of speech and freedom

Fsf the press is so fundamental, itis often taken for granted. FromWatergate to Whitewater, Ameri-cans expect their news media tofreely report on the controversialissues surrounding their govern-ment and politicalleaders.

; : , While certainlimits on press free-dom have sometimesbeen deemed neces-sary in times ofnational crisis, mostAmericans neverquestion the basicpremise that a freepress is crucial to afree society. Thiswasn't always thecase, however.

.In early colonialtimes, freedom of thepress as a legal rightdid not exist and anewspaper publishercould be fined oreven thrown in jailfor writing a criticalstory about a government official— even if the story was proven tobe true.

One of the first and most sig-nificant events that helped changethis state of affairs occurred in1735 in colonial New York. Theincident — which set the stage forfuture events that shaped theright to free speech in the US —involved an ordinary Germanimmigrant, many of New York'selite and some nasty politics.

The Deatlvof a Governor and theBirth of a NewspaperThe newspapers of pre-revolutionAmerica were a dull affair, con-sisting mostly of advertisements?nd reprints of European newsreports. The main impediment toa.more vibrant press was govern-mental censorship. In those days,

almost any printed criticism of thegovernment was considered acrime, and few publishers werebrave enough to risk imprison-ment by printing something thatmight irk a government official.

By the early 18th century,with the political tensions

between thecolonies andEngland rising,stirrings fromthe public wereheard to endthe govern-ment's controlof the press.

In 1731, achain of eventsstarted that

•Ssw>sra5K: isp; «a«s5;-K-s-i=- would push^™-™^^^:--^;^ some New

;,•*,*>£

x ' : . ' , - ' .. • ' ..'-v.. ..: . '. .For 1'aiHTis'o am! Fcr,lR>ii!ir-, ;•. I'JBEL

agiuiir the Guvermuair; '•:->::'-•';• ' . - , . . . - . ' • • • , • . ' ' . - . . , "- ' '--- • ' • ' - . ' . ' , .' '

Cosby was appointed, the formergovernor of the Island of Minorca.Cosby chose to remain in Englandfor another 13 months, while inNew York a government officialnamed Rip Van Dam governed inhis place. When Cosby finallyarrived in New York in 1732, hedemanded half the pay Van Damearned while acting as governor.Van Dam refused and Cosbypromptly sued. During the subse-quent court proceedings, one of ,the judges hearing the case, ChiefJustice Lewis Morris, ruledagainst Cosby. In retaliation, thegovernor removed Morris fromoffice.

These acts, along with otherinstances of questionable govern-ing, infuriated Cosby's critics,who wished to make public what

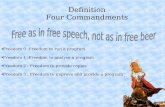

Top left, cover of the book that told the story of the precedent-setting trial, saidto have been written by one of Zenger's attorneys in 1752. Above, the court-

room drama is captured in this illustration from the period.

York powerbrokers, frustratedwith timid news reporting, intoaction and set off one of the defin-ing moments in American journal-ism history.,

It all started with the death ofthe colonial governor of NewYork. To take his place, William

they saw as the governor's tyran-nical actions.

However, the only newspaperin town at the time was the NewYork Gazette, a loyal organ of theCosby administration. To counterthe pro-government bias of theGazette, Cosby's critics, led by Van

History Magazine December/January 2006 — 13

FAMOUS TRIALS

Dam, Judge Morris and the well-known lawyer James Alexander,decided to start their own journal.They called their newspaper TheNew-York Weekly Journal and hireda German immigrant named JohnPeter Zenger to print it.

Although Zenger didn't writeany of the articles that would soonland him in jail.— the Journal'santi-government articles werewritten by the paper's intellectualbackers — as its publisher he waslegally responsible for everythingthe paper printed.

The first issue of the Journal,which appeared on 5 November1733, accused Cosby of harassingvoters and immediately turnedthe placid, predictable newspaperworld of New York into a venuefor a furious political brawl.

Another issue covered thegovernor's oppressive behavior —"We see men's deeds destroyed,judges arbitrarily displaced, newcourts erected without consent ofthe legislature by which... trial byjury is taken away when a gover-nor pleases."

Since public criti-cism of a governmentofficial was extremelyrare, readers followedthe frequent attackswith delight. Cosby,however, wasenraged. The gover-nor's first act of retri-bution wasquestionable in bothits efficacy and itspublic relationsimpact — he had sev-eral of the Journal'smore damning issuespublicly burned.Things grew moreserious when on 17November 1734,Zenger was arrestedand jailed on chargesof seditious libel.

The Trial of John Peter ZengerWith Zenger in jail and his wifetaking up the work of publishingthe Journal, Alexander and the restof his allies set about planningZenger's defense. It wasn't goingto be easy.

The charge of seditious libel

was based on English legal prece-dents prohibiting statements thatcould incite the public against thegovernment. Under this legal tra-dition, the prosecution wouldonly have to prove that Zenger'snewspaper had published the arti-cles in question. There could be noconsideration by the jury ofwhether the statements were trueor libelous. This put Alexander,who acted asZenger'slawyer, in thealmost unten-able position ofdefendingsomeone whohad publishedthe evidence ofhis guilt in hisown news-paper.

Zenger'sfate grew evendarker afterAlexander wasdisbarred earlyin the pre-trialproceedings for

weak", Hamilton agreed to risk \s reputation and health on a <

controversial case that seemed jdoomed from the start. The trial;took place at City Hall and woul|open and close in one day, 4August 1735.

With Hamilton arguing for 'defense, few in the courtroomdoubted there would be drama,;but no one could have predicted;]

the lawyer's

-B., _____ =— .

^ ''. T : - - w K . .Mv;w;|j

£Tji^ ^cIJi-&6&,- :' ' '

. _

'

^of.. Airomej1." «T&r«i'-mj'- 'Proof*' 'of my :

' -'

;v;:;::iSM^^vU,;.3:

Top, a page fromZenger's New YorkWeekly Journal news-paper, following thetrial and Zenger'slandmark Not Guiltyverdict. In the article,Zenger thanks alengthy list of partici-pants including hissolicitors and jurymembers. Left, apainting depictingthe case's variouslawyers, judges andjury members.

arguing with the judge. Thisforced Zenger's defenders toquickly find another lawyer brave,or reckless, enough to take thecase. They decided to aim highand prevailed upon the mostfamous attorney of the day,Philadelphia lawyer AndrewHamilton. Although he was 60and described himself as "old and

first words,whichamounted to;admission that;his client had jindeed corted the allegeoffense. "Ido|confess that h§tjudboth printed mamand publishect|repthe papers setjfjurforth in the sffsini[indictment]. "4Over the gaspsjof the court,Hamilton con-!tinued, "I dohope in sodoing he hascommitted no;;crime." ' 1

This |delighted the ;| outprosecutor, wjpancknew that the|jury was only:!required todecide onwhether Zenghad publishethe criticisms/!regardless oftheir truthful-/|yoiness. It seemed!to most people! cin the court-room that,'Zenger's ilawyer had JUEJ

|timffre<?gre|urd

ind

EGo-

admitted this point the jury had1

no option but to convict.Hamilton, however, was:

finished. Citing precedents d;back to Magna Carta and in wordfwh.that brought cheers from the :tators, Hamilton derided the '.and insisted that truth was indetyat the heart of whether Zenger § fleewas guilty of seditious libel. The

14 — History Magazine December/January 2006

-fedtrial

ino

irritated judges angrily admon-ished Hamilton "to use us withgood manners" and remindedhim that he was not permitted tooffer truth as a defense againstlibel.

The judges were on firm legalfooting here and Hamilton knewit. At this point, Hamilton's taskwas no longer to argue inZenger's defense, but to argueagainst the fairness of the lawunder which he was charged.The notion of what the presscould publish in a free societywas now the focus of the case.Zenger became a footnote tohis own trial.

Hamilton's strategy wasto go over the heads of thejudges and prosecutor andappeal directly to the public,represented by the men of thejury. This was a wise move,since popular opinion at thetime greatly favored increasedfreedom of the press. Withgreat flair, scathing irony andunfailing logic, Hamiltonframed the case against thelowly German immigrant asan assault on the jury's —indeed all citizens' — liberty.

In a thinly veiled dig atGovernor Cosby, Hamiltonoutlined the inherent rightand natural inclination of peo-ple to truthfully criticize agovernment official who"brings his personal failings,but much more his vices, intohis administration." Thisbrought a bald threat from theprosecutor, who warnedHamilton to "have a care whatyou say, and don't go too far."

Undeterred, Hamilton con-cluded his address by likening thetrial to a clash between liberty andtyranny, with the men of the juryon the front lines of this battle."The question before the Courtand you, Gentlemen of the Jury, isnot of small or private concern. Itis not the cause of one poorprinter, nor of New York alone,which you are now trying. No! ...Every man who prefers freedomto a life of slavery will bless andhonor you as men who have baf-fled the attempt of tyranny..."

The jury deliberated for a

short time and, to no one's sur-prise, found the defendant notguilty.

Zenger was set free afterspending most of the previousyear in jail and would continuepublishing the Journal until hisdeath at 66 years of age. Hamiltonspent the rest of his days as ajudge, dying on 4 August 1741, sixyears to the day after the Zenger

A minute book page from 4 August 1735,detailing the trial of The King vs John Peter

Zenger.

trial. As for the unfortunate Gov-ernor Cosby, things did notimprove after his bitter disap-pointment over the verdict. He fellill that winter and died the follow-ing March, with the stain of theZenger affair still very much onhis reputation.

Psychological ImpactThe historical legacy of the Zengertrial is a momentous one but acomplex one as well.

While most citizens rejoicedover the verdict, many othersworried about the detrimentaleffects that could follow whenpopular sentiment trumps the law,

as it did in the Zenger verdict.The legal effects of the trial

were also murky. On the mostbasic level, the trial was only anisolated victory for Zenger and hissupporters, with no actual legalprecedents being set. In fact, it'svery likely that the Zengeriteswould have again felt the wrath ofthe governor's office had Cosbynot died so soon after the trial, he

not being one to take such adefeat quietly.

The importance of theZenger case lies instead withits great psychological impacton the early American con-sciousness.

In a broad sense, theZenger case proved that thecolonists could successfullyrebel against British laws theyconsidered unfair and unnat-ural. In this respect, Zenger'sacquittal would foreshadowevents such as the Boston TeaParty of 1773 and the Revolu-tionary War itself.

More fundamentallythough, it showed how pow-erful the yearning for a freepress and free speech was tothe colonists. Hamilton's pleawas one of the earliest andmost eloquent expressions ofthe.right to criticize the gov-ernment without fear of retri-bution. Hamilton's words andthe popular support for theverdict would later be atremendous influence andinspiration to the founders ofthe new nation.

It is fitting then, that NewYork's City Hall, the site of JohnPeter Zenger's trial, would laterbecome Federal Hall, site of thesigning of the Bill of Rights in1789, which prohibited theabridgement of "freedom ofspeech, or of the press."

Further Reading:• Putnam, William Lowell. JohnPeter Zenger and the FundamentalFreedom (North Carolina: McFar-land & Company, 1997).• Zenger, John Peter. A Brief Nar-rative of the Case and Tryal of JohnPeter Zenger, Printer of the New YorkWeekly Journal (New York: ^^Brandywine Press, 1997). dUl

History Magazine December/January 2006 —15

![Dolomites (IAS Special Publications 21) [B.H. Purser, M.E. Tucker, D.H. Zenger]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/55cf941c550346f57b9fb3f3/dolomites-ias-special-publications-21-bh-purser-me-tucker-dh-zenger.jpg)