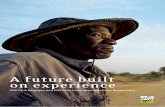

food aid english 18 1 06 - Action Against Hunger...Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives...

Transcript of food aid english 18 1 06 - Action Against Hunger...Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives...

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

1

Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

2

Objectives of this book:

Constitute a reference for the principles and methodology of intervention

for food aid and alternatives to food aid,

from initial assessment to implementation and monitoring.

Table of Contents

PREAMBLE ...............................................................................................................................................................5

INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................5

Chapter 1 : ACFIN’s Position on Food Aid .............................................................................................................7

I Introduction............................................................................................................................................................7

II Technical approach...............................................................................................................................................7

III Context and objectives of food aid programs......................................................................................................8

IV Impact of food distribution .................................................................................................................................8

V Intervention principles of food aid and its alternatives ......................................................................................10

VI Argument ..........................................................................................................................................................10

VII Summary..........................................................................................................................................................11

Chapter 2 : Preliminary Assessments .....................................................................................................................12

I Introduction..........................................................................................................................................................12

II Context Study .....................................................................................................................................................13

III Study of food markets .......................................................................................................................................13

IV Identifying the populations’ needs....................................................................................................................15

V Estimating the number of individuals in a population........................................................................................16

VI Other actors present ..........................................................................................................................................16

VII Logistical assessment.......................................................................................................................................16

VIII Deciding on an implementation plan for a distribution program ...................................................................17

IX Summary ...........................................................................................................................................................18

Chapter 3 : Choice of the Type of Distribution Program .....................................................................................19

I Establishing an intervention strategy ...................................................................................................................19

II Responses to a lack of food availability .............................................................................................................22

III Responses to a lack of access to food................................................................................................................29

IV Key questions for the choice of program type ..................................................................................................34

V Summary ............................................................................................................................................................35

Chapter 4 : Development of the Program ..............................................................................................................36

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

3

I Targeting the vulnerable population ....................................................................................................................36

II Selecting work-exchange projects ......................................................................................................................39

III Determining the ration to be distributed............................................................................................................41

IV Supply logistics .................................................................................................................................................49

V How are the populations and local structures involved? ....................................................................................54

VI Human resources...............................................................................................................................................56

VII Summary..........................................................................................................................................................62

Chapter 5 : Registration of Beneficiaries ...............................................................................................................63

I Introduction..........................................................................................................................................................63

II Obtaining lists realized by a third party..............................................................................................................64

III Realizing the registration process......................................................................................................................64

IV Ensuring the quality of the registration.............................................................................................................67

V Summary ............................................................................................................................................................70

Chapter 6 : Distribution Conditions .......................................................................................................................71

I Choosing a food distribution program .................................................................................................................71

II System of cash distribution.................................................................................................................................72

III Site selection and number of distribution points ...............................................................................................73

IV Awareness .........................................................................................................................................................74

V Adjust the conditions in the case of absent beneficiaries ...................................................................................75

VI Summary ...........................................................................................................................................................76

Chapter 7 : Food Distribution Circuit ....................................................................................................................77

I Stations prior to actual distribution of the foodstuffs ..........................................................................................77

II Actual distribution of the foodstuffs...................................................................................................................78

III Examples of distribution circuits.......................................................................................................................80

IV Canteen circuit ..................................................................................................................................................84

V Summary ............................................................................................................................................................86

Chapter 8 : Flow Planning and Management ........................................................................................................88

I Flow of a food distribution program....................................................................................................................88

II Planning the supply of distribution points ..........................................................................................................90

III Basic documents................................................................................................................................................91

IV Flow management .............................................................................................................................................94

V Itemize the losses................................................................................................................................................95

VI What weight should be taken into account?......................................................................................................96

VII Reports.............................................................................................................................................................98

VIII Flow reconciliation and monitoring ...............................................................................................................99

IX Flow of a cash distribution program ...............................................................................................................100

X Summary ..........................................................................................................................................................101

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

4

Chapter 9 : Program Monitoring and Evaluation...............................................................................................102

I Verifying the registration list and the targeting criteria .....................................................................................102

II Food Basket Monitoring (‘FBM’) ....................................................................................................................104

III Post distribution monitoring (‘PDM’).............................................................................................................106

IV Information to collect......................................................................................................................................108

V Role of nutritional surveys ...............................................................................................................................110

VI Summary .........................................................................................................................................................110

Chapter 10 : Frequently Asked Questions about Food Aid................................................................................111

I What is a food aid program?..............................................................................................................................111

II What is meant by ‘alternatives’ to food aid? ....................................................................................................111

III A food aid program: is it Logistics or Food Security? ....................................................................................111

IV When should a food aid program start, and when should it stop?...................................................................112

V How can we be sure that the food aid reaches the most vulnerable? ...............................................................112

Examples .................................................................................................................................................................113

Figures .....................................................................................................................................................................114

Tables.......................................................................................................................................................................114

Appendices ..............................................................................................................................................................115

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

5

PREAMBLE

This book is part of a series of food security books developed by Action Contre la Faim (ACFIN1) and is based upon a consolidation of experiences and investigations led over the past ten years in the field. This series looks at and develops specific aspects of the different food security programs, especially the technical tools that can be used within the scope of precise projects. Each of these books can be read alone or they can be complemented and reinforced with the other ACFIN Food Security books included in the series constituting a ‘food security kit’ which can be presented as follows:

The books address a variety of audiences including the international humanitarian community, technical and operation field workers and the general public who wishes to learn more about food security at the international level. Each book contains a detailed index with examples of the different tools that can be used for the implementation of the programs, a glossary of technical terminology and commonly asked questions that can give the reader a quick response to key points highlighted throughout the document. This series could eventually be completed with other types of food security programs depending on the development and research led in the field (i.e., food security in the urban context, in the pastoral environment or other topics such as community participation). All of these books are subject at all times to additions and or improvements following the development of the food security department at Action Contre la Faim and the continued internal and external evaluations of the different food security activities. INTRODUCTION This book presents the principles and methodologies specific to food aid interventions and the alternatives to food aid. The “alternatives” to food aid are programs based on monetary support that may be either direct (cash distribution) or indirect (stamp or voucher distribution). Due to the diverse contexts and situations found in the field, this book does not provide an exhaustive response to all the problems encountered but will furnish a certain number of keys and tools which will facilitate the implementation of food aid programs according to the needs of the population in a given context. Chapter 1 presents the position of Action Contre la Faim on food aid through its objectives, its stakes, and its intervention principles.

1 ACFIN is the international network comprised of ACF Canada, ACF France, ACF Spain, ACF UK and ACF USA. The international network shares a common charter and global objectives.

Introduction to Food Security:

Intervention Principles

Food Aid and Alternatives to

Food Aid

Income Generating

Activities

Agricultural Rehabilitation

Food Security Assessments and

Surveillance

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

6

Chapter 2 readdresses the specifics of the initial assessment of any food aid program (the methodologies of which having already been widely developed in the book, Food Security Assessments and Surveillance). This assessment determines the nature and the level of the food security, as well as, where indicated, the conditions of intervention. Chapter 3 presents and compares the different types of food aid programs and the alternatives that may constitute the intervention strategy so as to implement the most appropriate solution possible. Chapter 4 explains how to determine the essential aspects of intervention strategy, and Chapter 5 specifically addresses the methodologies of the registration of the program’s beneficiaries, a step crucial to the success of the program. Chapter 6 discusses the different possible distribution systems so as to help make the most appropriate choices according to the advantages and disadvantages of each. Chapter 7 details the organization of the distribution sites according to the selected conditions, and Chapter 8 gives the tools necessary for planning, monitoring, and the control of the flow of products to be distributed. Chapter 9 complements this process with the tools of follow-up and evaluation, making it possible to measure the program’s progress and to make adjustments when indicated. Chapter 10 ends with the most frequently asked key questions. The responses highlight the key points developed throughout this book.

Acknowledgements: It is not possible to name each person who contributed to the development of this book; however, the methodology and examples illustrated here are a compilation of experiences from hundreds of ACFIN expatriates and local staff over the last ten years. Special thanks should be given to all those who have worked in the food security departments of ACFIN headquarters and who all contributed in some way to develop the department and laid the foundation of this Food Security Series. Special recognition should go to Fred Mousseau, food aid expert, for having written the initial version of the food distribution module that remains the backbone of the current book, Kate Ogden, Caroline Wilkinson, and Henri Leturque, for their technical contributions, Béatrice Carré and Anne-Laure Solnon for their volunteer and professional work on the quality control of foodstuffs and the capitalization of ACFIN experiences on food aid alternatives, respectively, Laurent Mirione and Vincent Tanguy, directors of the mission logistics service, for their constructive collaboration on the common tools necessary for the food aid programs, This book was updated this year by Fred Michel in coordination with a peer review team consisting of Hanna Mattinen, Pascal Debons and Lisa Ernoul.

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

7

CHAPTER 1 : ACFIN’S POSITION ON FOOD AID

I Introduction2

Despite the promises of the World Food Summit in 1996 to halve the number of malnourished people by 2015, this number has not ceased to grow at a rate of 4.5 million per year. In 2004, over 842 million people were considered malnourished, even though millions of tons of food aid are provided annually. Food aid volumes continue to depend on the stock available and the international trading price of cereals, especially wheat. When the prices are low and the available stock becomes more abundant in developed countries, delivery of food aid increases, and vice versa. Bilateral aid from state to state remains a political and economic tool which is most often monetized to help support the commercial balances of the beneficiary countries, generally without connection to the needs of the hungry. Moreover, for decades international food aid has participated in the impoverishment of the food crop economies by the dumping of foodstuffs produced in developed countries, flooding the national markets with low prices because of subsidies given to the “Northern” farmers. For almost ten years, the majority of international food aid has been allocated to emergency and restoration operations, with the help of bilateral aid: this positive sign reflects a better understanding of humanitarian needs because it is addressed, on the basis of the analysis of the needs, to the populations without buying power and theoretically does not affect local production. The development of the capacities and expertise of emergency humanitarian organizations contributes to the improvement of international food aid, making it a true humanitarian action. It is within this perspective that ACFIN places itself in order to better fight against hunger.

II Technical approach

Action Contre la Faim aims to save lives, to relieve human suffering, and to re-establish and preserve food security, by acting at different levels, while respecting the dignity of the people and protecting the populations. The technical strategy of ACFIN takes into account the different levels of causes (direct, underlying, or basic) that determine the nutritional status of the individuals. This general method of tackling the problem is represented by the flow chart on the causes of malnutrition (see figure 1). Food security for ACFIN is based on the definition provided by the World Bank in 1986: “ensure the access and availability by all people at all times to enough quality, healthy and appropriate food.” The key words here are clearly: access, availability, quality, healthy, appropriate food. The use of the food is also taken into consideration, leading to a tight collaboration with the nutritional department. This service provides the necessary expertise on the nutritional impact of the foodstuff according to their composition (nutrients), their methods of conservation, and their preparation. The objective of the food aid programs is to respond to food destitution by directly providing food, while

promoting the self sufficiency of the beneficiaries3. Consequently, the ACFIN food security service has developed specific expertise through the recruitment and training of professionals who manage the food aid programs, from emergency programs to those of longer-term food security. The programs make up part of a global strategy including:

- The analysis of the multiple components of food security - Immediate food aid in response to food destitution - Household economic support, with the goal of reinforcing the coping mechanisms to increase the access to

foodstuffs (production, exchange).

2 Adapted from the report written for ACF by Fred Mousseau, ‘Bitter wheat, food aid, and the fight against hunger,’ October 2005 3 At the ACF headquarters in France, food aid was integrated into the food security service in 2001. The fusion of food aid and food security means a precise contextual analysis may be carried out, and immediate food security activities are encouraged, while limiting the potential negative effects and the duration of food aid activities.

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

8

This approach, developed by the food security service at Action Contre la Faim, is based on the analysis of the local food markets and the populations’ mechanisms to live and survive, as well as on the identification and targeting of the most vulnerable groups within the populations.

III Context and objectives of food aid programs

Food aid or its alternatives are indispensable in emergency situations, when the populations lose their means of livelihood (harvests, livestock, economic activities) because of a conflict, an economic or political crisis, or a natural disaster, and find themselves confronted with food destitution. In these situations, distribution should be implemented in a fast, efficient manner in order to ensure the people’s survival. If necessary, parallel, complementary actions should be developed. These may include: reserves of drinking water; medical care and treatment for the malnourished in the nutritional centers. Simultaneously, food security responses over a longer term should be prepared to replace the emergency intervention. In such a context, the distribution should help the crisis victims survive by providing available and accessible food products, of adequate quality and quantities in order to prevent the development of malnutrition and disease. Another objective of food aid is to prevent the people’s resorting to the kinds of coping mechanisms which could, over the long term, create negative consequences on the people’s living conditions and food security: total or partial migration of the members of a household, transfer of capital, new and unsustainable economic activities such as wood harvesting, decapitalisation of productive goods, etc. Depending on the cause and the severity of the food deficit within the households, the type of aid program will be based on providing either foodstuffs or cash.

Table 1: Type of aid to be provided according to the food problematic

Conditions and Causes of food destitution Food problematic Response to provide • Level of harvest inexistent or very

low

• Level of food stock inexistent or very low

• Market destitution, non-functioning markets

• Elevated prices of staple foods

Lack of food availability

Injection of foodstuffs

• Significant drop in buying power due to loss of revenues (work, loss of production tools) and/or the loss of working capacity (illness, death, emigration)

• Functioning markets which can respond to the increase in demand

Lack of access to foodstuffs

Injection of cash and food coupons

IV Impact of food distribution

The expected impact of the food distribution program is above all nutritional because it tends either to improve the nutritional status of the beneficiary population or to prevent its deterioration. Nevertheless, food aid often has more or less desirable effects that must be anticipated and evaluated before deciding on the kind of intervention and the conditions. In order to reduce the negative impacts of food aid programs, Action Contre la Faim analyses the following parameters prior to engaging in type of activity:

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

9

• Local economy and living standards of the population Aid constitutes an economic resource for the beneficiary population. It can be sold or exchanged and can provide resources which are indispensable to the household in dealing with the necessary expenses. Sometimes, food aid represents an essential part of the resources of the people in crisis situations. As such, it can become a major stake for the populations but also for the authorities or the rival groups in an armed conflict.

• International politics and commerce Aid can also be a commercial or economical political tool of international contributors, accentuating the dependence of a beneficiary country on external aid. Often the volume of food aid is based on international market prices rather than the degree of the populations’ food needs. The agricultural excesses of rich countries make up the greater part of the food aid. For example, such food aid does not permit the use of the local food availabile when they exist and can, in such a case, generate significant degradation of the economic outlets of the local producers.

• Political situation and social relationships within a group The economic importance of the aid can naturally tempt politicians and the local despots to divert these resources towards political ends. Food aid, in particular, may serve as a substitute for the social assistance of a government. Additionally, depending on the distribution method, the aid can influence the internal relationships within a group. For example, it could create a foundation of power or situations of dependence. Aid can also facilitate a certain social cohesion or, by contrast, create tensions (for example, in the case where only certain groups are targeted).

• Security of the people The value of the aid can also attract the attention of armed groups, military groups, or Mafia, thereby creating new risks, especially when there are new governments and/or population movements.

• Economic organization of a zone Aid can enter de facto into competition with the local production, harm the pre-existing commercial networks, and thereby cause a modification of the prices of foodstuffs in the beneficiary zone. This concerns not only the impact of the distribution but also the choices made with regards to the merchandise (local or regional purchases or importation from another region), the foodstuffs (type and varieties chosen), and the type of distribution (actual food or a food coupon system). Inversely, local purchases in large quantities when availability is insufficient could cause a price increase that would penalize the entire population of the zone.

• Population movements Aid can stabilize populations in the beneficiary zone, or it can stir them up. The local authorities or the military forces may be tempted to use the aid as a political instrument for displacement or regrouping. By contrast, local authorities or military forces could oppose the aid if they believe it encourages an undesirable situation to continue.

• Perpetuation of a crisis situation Aid can demotivate or even discourage the populations during their necessary return to self-sufficiency following a crisis. In certain cases, as a result of taxation, theft, or the more or less voluntary participation of the aid recipients in a war effort, aid can also become a source of provision for armed groups implicated in the crisis.

• Health of the populations

Although food aid normally has a positive effect on the health of the beneficiaries, the distribution of rations that are insufficient in vitamins and minerals could cause the development of epidemics and serious deficiencies, for example pellagra, scurvy, or beriberi. International aid focuses on the macronutrients (lipids, proteins) and rarely considers the micronutrients in the composition of its rations. Food aid therefore becomes a risk, especially when it is the principle resource (i.e., not complemented by other sources) over a prolonged period.

• Ecological environment Certain distributed foods require more fuel than others for their preparation. This may have an ecological impact over the long term, engendering deforestation. On the other hand, favoring local foods reduces the risks that

foodstuffs containing genetically modified organisms4 might be used as planting seeds.

4 For more information, refer to the ACFIN paper on positioning concerning genetically modified organisms.

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

10

• Cultural aspects Importing foodstuffs can have long-term consequences on local customs. Here again, local food should be favored in order to prevent upsetting the local eating traditions.

V Intervention principles of food aid and its alternatives

Food aid consists of distributing the food to the beneficiary populations. When alternatives to food aid are more appropriate, non-food items (blankets, jerry cans, cooking utensils, emergency shelters) and/or cash could also be distributed. In conformity with the project cycle management, the activities are defined with the goal of minimizing the adverse effects previously mentioned and to maximize the results expected from the desired objectives (see above, section III).

Distribution programs are based on the following principles:

• All food aid programs are preceded by an assessment and an analysis of both the needs of the populations and the socio-economic and geopolitical contexts, including the aid politics of international contributors. This analysis shows the pertinence of the intervention and helps determine objectively identifiable indicators to monitor the potential activities.

• Food aid is a means and not an end: an exit strategy is prepared at the beginning of the intervention; food security activities that are aimed at longer-term objectives may be gradually introduced.

• Program implementation takes into account the logistical capacities and the human and financial resources of ACFIN, including the capacity to manage the security necessary because of the context or the type of project.

• Food rations should consider the composition with regards to an appropriate supply in nutrients (micronutrients included), local customs, and respect for the environment.

• Local and regional purchases are, when possible, favored in order to ensure culturally appropriate food and in order to support the local economy.

• Food products of good quality are provided by respecting the definition of the appropriate specifications and a systematic quality control of the foodstuffs from the supplier to the beneficiary.

• The existing local capacities and resources are identified and used throughout the program as much as possible.

• Effective measures are adopted in order to ensure that the most vulnerable groups are effectively reached,

while taking into account the security risks5, the local context, and the dignity of the populations.

• All of the program’s activities are subjected to ongoing monitoring and systematic evaluations throughout the duration of the program. An impact analysis is carried out in order to reorient the activities, if necessary, and to optimize the definition and realization of future programs.

• The activities are coordinated with the other partners onsite, with the goal of obtaining optimal aid cover.

VI Argument

ACFIN aims to contribute to reducing hunger by informing the public and by influencing the politics and the practices of the principal actors through a proof-based analysis. Its argument is based on the following principles:

• Detailed analysis of the causes, responsibilities, and solutions of the hunger problem in certain countries.

• Identification of the common factors of the hunger problem in the countries where ACFIN intervenes, in order to define global tendencies.

• Defend the cause of hunger before the national and international communities.

5 Security risks for the populations and ACFIN teams

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

11

Depending on the stakes involved, the food aid programs can be at the heart ACFIN’s lobbying, especially on the international system of food aid to contribute to its improvement for the benefit of the populations suffering from hunger. ACFIN means thereby to denounce as much as possible the downward spiral of a food aid system....

- Which offers only a default response to the deeper problems which continue to be overlooked, - Which contributes to reduced food crop farming and increased dependence on the importation of foodstuffs, - Whose allocations depend less on objective needs assessments and more on the political or commercial

interests of the donating countries.

This is why ACFIN proposes a certain number of paths for lobbying and action6:

• Reject the conditionality of the aid: aid should be provided according to objective assessments of the needs and not the interests and agendas of the donating countries. Food aid should especially be provided independently of the market reforms.

• Encourage the donating countries to reduce actual food aid in preference for direct financial aid, which would permit the financing of other types of actions and of local food aid purchases in the developing countries.

• Encourage food aid purchases in the Southern countries, ensuring that this will benefit the poorest countries and their small farmers.

• See that the food aid is no longer the dominant response in emergency situations nor the default response to structural deficit problems and chronic food insecurity. Food aid should become an instrument among others and be used pragmatically and within limits.

• Reform or eliminate the international institutions that govern food aid, whose existence and mandate reflect the logistical measures of dealing with surplus in developed countries.

• Review and reconsider aid politics in order to give priority to the local farmers and to favor food self-sufficiency in the poorest countries.

• Return the responsibility and the means of fighting international hunger to the FAO (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization) by implementing a more responsible aid politic with the governments and the NGOs.

• Give the poorest countries the political and financial means of fighting hunger, through the elimination of debt, enhanced development aid, and the right to food sovereignty.

VII Summary

• Food aid and its alternatives are tools for improving food security of populations having suffered adverse conditions.

• Food aid programs are necessary when a certain population or group no longer has the capacity to feed itself.

• Food aid responds to a lack of food availability: the alternatives respond to the populations’ lack of access to the foodstuffs.

• Intervention principles enable risk reduction and maximized impact of the aid program.

• Food aid should remain short-term and can be relieved by longer-term programs that restore autonomy in the targeted population.

• Food aid at ACFIN also aims to contribute to the improvement of the international system by denouncing any wrongdoings witnessed in the intervention fields and by making recommendations.

6 Extract of the report written for ACFIN by Fred Mousseau, ‘Bitter wheat, food aid, and the fight against hunger,’ October 2005.

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

12

CHAPTER 2 : PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENTS

I Introduction

Action Contre la Faim follows the causal approach of malnutrition to evaluate humanitarian needs. As the conceptual chart shows (see figure 1), malnutrition is not only related to a problem of accessibility or availability of food, and other factors must be taken into consideration. Identification of the population’s needs is therefore not centered only its food situation; it also takes its social, medical, or sanitary problems into account. In the same approach, the basic causes at the economic and political levels must also be fully understood. Even in the case where Action Contre la Faim would not be able to develop responses to all the needs identified, it is important to perform this type of multi-sectional assessment in order to ensure that the proposed response is indeed the most appropriate. Additionally, it may serve as a way to lobby for the intervention of other actors.

Figure 1: Causal chart of malnutrition 7

In a crisis situation, the general context analysis and an initial needs identification make it possible to recommend possible activities. When it is decided that food aid must be provided, these assessments should necessarily be complemented by further investigation to help establish the pertinence and feasibility of this type of intervention. The methodologies of the investigations are presented in the book, Food Security Assessments and Surveillance.

7 Adapted from UNICEF, 1997

MORTALITY

INADEQUATE FOOD SUPPLY

LOCAL PRIORITIES

FORMAL AND INFORMAL ORGANISATIONS AND INSTITUTIONS

POLITICAL IDEOLOGY

RESOURCES

� Human

� Social � Environmental � Structural � Financial

FUNDAMENTAL CAUSES

UNDERLYING CAUSES

IMMEDIATE CAUSES

HOUSEHOLD FOOD SECURITY

�

Food availability �

Food accessibility

PUBLIC HEALTH AND HYGIENE � Sanitary environment � Access to health structures � Availability, quality, and access

to water

MALNUTRITION

SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT AND RESPONSIBILITY � Behaviours and responsibility � Role, status, and rights of women � Social and organisational networks

DISEASE

� Use of food

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

13

II Context Study

The context in which a crisis has occurred should be studied in depth, from various angles: Social

• Socio-cultural characteristics of the population: way of life, habitat, customs, role and status of women, etc.

• Local capacities and resources: administrative or traditional structures in place, their functions, their capacities and reliability, level of education of the local population, languages spoken, capacities and capabilities, particular constraints related to their characteristics.

• Political and social structure of the population: institutions, social system, etc. Security

• Conditions of access of the affected population as well as the factors influencing the safety and security of that population and the people who intervene: risk analysis, study of the different actors involved in a conflict, etc.

Economic

• Economic and food situation of the targeted region: the principle resources and dependencies in the zone; exporter zone, deficitary zone, balanced zone; types of foodstuffs imported/exported

• Environment, climate, agricultural calendar and their effects on the populations in terms of activities and movement

III Study of food markets

As soon as a serious perturbation of the livelihood of the affected populations is suspected in terms of food (production crisis, breakdown in the supply system), we must first, before developing any sort of program, evaluate the food availability in the affected zone and its prospects according to the possible market reactions. The goal is to determine whether the program should respond to the problematic of a lack of food availability or a lack of food accessibility. Seasonal variations must always be taken into consideration (agricultural calendar of local production, for example) to identify the real impact of the crisis on the food economy. The results of this study, led at the country level as well as at the target zone level, are then combined with the analysis at the household level (see section IV). First, an analysis must be performed on: The availability of basic products before and after the crisis, in the affected zone and within the whole country, based on macro-economic data:

- Seasonality of the exchanges in a ‘normal’ year - Level and sources of production (deficitary zones and surplus zones) - Level of the accessibility and functionality of production sources - Level and origins of imports - Level and destinations of exports

- Level of stock (private and public8) and government politics on the use of reserves - Level of bilateral donations - Evolution of internal and external flow (cross-border) - Evolution of the exchange rates (official and parallel) and their impacts on the prices

The conditions of functioning market:

- Price levels - Existence of speculative phenomena - Situation of a monopoly of the actors (merchants, government) where prices are fixed - Level of integration (connections) of principle and secondary markets - Creation/disappearance of markets - Creation of new supply circuits - Sufficient or insufficient availability of staple products9

8 There may be national cereal offices having the role of stabilising the prices of cereals by manipulating the purchase and reselling of a part of the national production and/or of imported products.

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

14

- Changes in the types of foodstuffs and their packaging - Types of exchange: monetary or barter - Level and evolution of prices of staple products - Evolution in terms of exchange - Number of active merchants, and their capacity and willingness to respond to an increase in demand (for

example, by transfer from a surplus zone to deficitary zones) - Capacity for storage (size of warehouses, turn-over) and for transport (delivery frequency, truck size) - Existence of internal exchange barriers (taxes, road and bridge conditions, insecurity, front line, border

closings) - Evolution of buying power of the population in terms of credit systems

Later, the possible market reaction scenarios must be identified in order to understand the impact on the food availability of the affected zone according to whether food or cash is to be injected.

Table 2: Type of aid according to the conditions on the food markets (Oxfam, 2005).

Scenario Problematics and possible impacts Recommendation No available food in the zone’s neighboring markets OR Non-functioning markets

Problem of food availability without possibility of being addressed by the local markets.

Food aid

Abnormally high food prices AND Non-functioning markets

Problem of accessibility due to the loss of buying power because of elevated prices. Cash injection would elevate the prices even more.

Food aid

Food available in neighboring markets AND Loss of revenues in the population AND Functioning markets AND Hindered exchange actions (taxes, conflict) OR Non-competitive markets (prices controlled by merchants/speculators) OR Non-integrated (or non-connected) markets OR Merchants not willing or unable to respond to the increased demand

Problem of access to food. Cash injection would elevate prices because the offer could not be increased in the zone because of... --exchange barriers, --elevated ‘adjustments’ of the controlled prices, --neighboring markets not being connected to supply the zone (increase the offer) --merchants not increasing the offer of foodstuffs on the markets.

Food aid

Food available in neighboring markets AND Loss of revenues in the population AND Functioning markets AND Exchanges unhindered AND Competitive markets (prices controlled) AND Integrated markets AND Merchants willing and able to respond to the increased demand

Problem of access to food. The injection of food would lessen the demand and prevent development of the local economy of the food markets (production, commerce). Cash injection would cause an increase in demand and the conditions in the food markets would provide a response to the problem while developing their activities.

Direct aid on the buying power by injection of cash or food coupons.

9 The staple products are classically the traditional food products consumed by the population (in terms of cereals, legumes, fats and oils, fruits and vegetables) as well as the products of primary necessity such as soap and fuel.

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

15

Additionally, food needs at the household level must be understood: especially the potential impact on their level of resources and their coping strategies.

IV Identifying the populations’ needs

The nutritional survey will estimate the level of malnutrition prevalent within a given population through the use of

anthropometrics criteria and supplies good indications on the definition of the program’s priorities.10 The food security assessment11 seeks to identify the causes of this malnutrition and of the food insecurity. It should evaluate the population’s food availability, determine the food access and food consumption mechanisms, identify the categories of the population that are most affected, and understand the adaptation or coping mechanisms employed. It should also evaluate the capacities of the population to resist adverse conditions over time. The identification of the food security needs results from this capacity to cope with a crisis in order to minimize the deterioration of their livelihood means. (See figure 2 in the book, Food Security Assessments and Surveillance, for more information on the coping mechanisms.) For the specific identification of the food needs, the assessment should respond to the following questions:

- What is the current rate of malnutrition, and how has it evolved? - What are the causes of the malnutrition? - How much reduction or loss of livelihood has the population suffered (in terms of production, revenues,

tools/productive assets)? - What is the cause of the loss of buying power? (elevated prices, loss of revenues) - How have the prices of staple products evolved on the markets, and what are the exchange terms (when the

economy is poorly monetized or not monetized)? - How have the types of foodstuffs being consumed changed? - How significant is the drop in number of daily meals and quantities consumed? - What changes in the sources of supply have occurred (purchase, loan, begging, gathering)? - What changes in the levels of household food stocks have occurred? - Are the coping mechanisms adopted unbearable or risky? - What is the capacity of the households to cope with the adverse conditions? - What are the prospects of revenue (economic and agricultural) according to the seasonal variations?

The crosscheck of the needs analysis of the population and the study of the food markets (see section III) help determine whether the problematic is a lack of access to or a lack of availability of food, or both. As the conceptual chart shows (see figure 1), malnutrition is not necessarily linked to a problem of food access or availability, and other factors must be taken into account. For example, a problem of malnutrition is sometimes the result of poor weaning practices or sanitary problems related to poor drinking water quality that would obviously not be improved by food supply. Also, even if the nutritional needs are identified as priority and the food aid represents an adapted response, the program’s impact can be reduced because other needs have not been taken into account. For example, it is possible that the beneficiaries would have to resell a part of their foodstuffs to cover other needs which were not covered by the assistance, such as the purchase of hygiene products or reconstruction materials. The nutritional supply would therefore be inferior to that which had been initially planned and would not respond to the objectives fixed by the program.

The identification of a population’s needs is a step that must be taken prior to any intervention, but it should also be continued throughout the program’s ongoing verification and monitoring. The monitoring and evaluation should help measure the results and the impact of the activities and therefore continue to identify the evolving needs of the population (see the book, Introduction to Food Security, for more information concerning the project cycle).

10 Nutritional investigations are led exclusively by nutritionists who have the required expertise. Without this investigation, it is still possible to perform MUAC measurements on children under five, with the technical advice of the Nutrition department, in order to verify whether acute malnutrition is present or not. The results should never be used as statistically viable data. 11 For the information collection techniques and methodologies, see the book, Food Security Assessments and Surveillance.

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

16

V Estimating the number of individuals in a population

During an initial needs assessment, it is imperative to have at least a rough estimation of the number of people affected as well as their demographic characteristics in order to be able to evaluate the magnitude of the crisis, the feasibility of the intervention, and the volume of assistance required. Two options may be available from the outset:

- Figures and statistics obtained from administrations, community representatives, or other organizations present

- Calculations based on local existing lists (in cases of displacement camps, for example). In cases where this information might not be available or seems unreliable, crosschecking of different sources will be needed, such as comparing local administration census figures to those of a vaccination campaign performed by another organization. The number of people can also simply be estimated by the aid workers using two methods that are explained in Appendix 3.

VI Other actors present

It is crucial to take the current or planned actions led by other organizations or local authorities into consideration. The following elements should be studied in particular:

- The real on site presence of the actors: NGOs (local and international), international organizations (ICRC, United Nations agencies, especially WFP, UNICEF), sponsors, local authorities, social institutions, local groups...

- Their analysis and position: What approach are the actors taking to the crisis? What assistance are they giving or planning to give?

- The current or forthcoming national politics: Is there a cereal reserve? How is it used to stabilize the markets? Are any zones being neglected?

- The type of assistance provided: rations provided for distribution but also the other activities being implemented in the other technical sectors (water and clean-up, medical, nutrition)

- How much geographic cover is included in the assistance: Which beneficiaries are targeted? How many? In which sites or what region?

- The selection methods of the beneficiaries employed: What selection criteria are used? How are they applied? How are the beneficiaries registered?

- The distribution methods employed: direct? How often? - Different constraints encountered during the registration of beneficiaries and foodstuff distribution. - Expectations and capacities for future action, which actions, when? - Access to the affected populations? Have any zones been overlooked?

This study is essential because it constitutes the first step toward good coordination among the actors and a cohesion of the interventions. It helps identify the zones that are not covered or poorly covered. Insufficient coordination may, in fact, cause later iniquities or program overlaps and even limit the impact of the assistance. Some groups could receive too much aid, others not enough. If rations or selection criteria are different, this could encourage people to relocate in order to be in the place where they feel they will receive the most aid. Additionally, joint cover by the different actors could influence the priorities or needs in a specific zone. Such a zone might have such poor cover that, in the end, it appears that it should have been targeted in the first place.

VII Logistical assessment

It is essential that the logistics service be involved at the initial stage of the assessment and especially in the perspective of developing distribution programs which require significant logistical support for the supply of products. The logistical plan should be defined at the same time as the program to ensure its feasibility and to be activated as soon as the budget has been validated. The logistical assessment will study the conditions of the beneficiaries’ access to the intended aid and thereby establish the feasibility of the implementation of activities. It therefore considers the possible alternatives for the

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

17

purchase or reception of the foodstuffs, their shipment, their storage, and their delivery to the distribution points where indicated. This study thus investigates:

• The possibilities of transport and storage (including in the affected zones)

• The entry points (ports, border crossings, airports) and their import capacities (equipment and materials)

• Location of existing foodstuff stocks, their availability, their costs, their mobility

• Identification of the private suppliers and assess their capacity to respond to the demand (quality, quantity, delivery time)

• Identification of the capacity of the humanitarian actors present who are susceptible to provide foodstuffs and other primary necessity goods (WFP, UNICEF, UNHCR, ICRC)

• The possible routes between the supply points (entry points, stock) and the affected zones

• The customs procedures and formalities and national legislation concerning the importation of specific (nutritional) products

• Transportation, storage, and warehouse costs

• The potential risks (security, access, quality of foodstuffs) Appendix 4 shows an example questionnaire for a rapid assessment of the different logistical aspects in an affected zone.

VIII Deciding on an implementation plan for a distribution program

The different assessments mentioned above should not only provide an objective view of the different domains studied but also take the foreseeable or possible effects of food aid into account (see Chapter 1): displacement of the population towards distribution points, aggravation of insecurity in areas adjacent to the distribution sites, depopulation of agricultural production areas, upset of the local market, reduction in the agricultural production volume, environmental impact, etc. Even so, it is often the case that in an emergency context that access conditions and insecurity prevent aid workers from performing as complete and in-depth assessments as would normally be desired. Consequently, it will be necessary to construct a certain number of working hypotheses that will later need to be confirmed or invalidated through the program monitoring. The monitoring and ad-hoc assessments of both the program and its impact should thus provide a way to review the hypotheses and the corresponding choices and to consequently adapt our actions. There is not only one solution for the definition and implementation of a food aid program. Only by synthesizing and comparing different assessments can the most appropriate program be decided, its pertinence and feasibility determined, and its implementation plan drawn up. The decision to implement a food aid program should thus systematically be based on a variety of objective indicators, such as those presented in the table below, initially helping to establish priorities the needs of a food aid program.

Table 3: Indicators to determine the pertinence of a program

Indicators Description

Degree of food needs

Rate (evolution) of acute malnutrition Food consumption level (quantity, diversity/quality) of families Production and food resource levels of families Breakdown of the production system and/or crop supply Local coping mechanisms (households, economic actors)

Level of needs Number of people affected

Presence of humanitarian actors Capacity to cover food needs

Level of risks of adverse affects according to the context

Access to the population Substitution of the role of local authorities Upset of the local economy Manipulation or misappropriation of organized aid

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

18

Security and political risks to the beneficiaries and the personnel Risks of aggravation of an unfavorable situation

Potential lobbying themes

Local purchases Nutritional quality—microelements Forgotten populations/discrimination Effects on the local economy caused by an international aid system

Technical and operational goals How transversal it is (with the food security and other technical activities) Development and capitalization of innovative projects (which could be reproduced in other intervention zones)

IX Summary

• The initial assessment establishes an analysis that serves as a reference to follow the evolution of the situation and the causes of the identified problem.

• The nature of the food problematics (lack of availability or lack of access) determines the type of response to be provided (injection of food or cash).

• It is at the household level that the intervention needs are confirmed; program monitoring and evaluation ensure an ongoing needs analysis in order to respond in the most appropriate manner.

• The capacities and the intentions of the actors present determine the help determine the intervention context.

• Logistics are an essential part of the initial assessment so that the constraints and resources necessary for the implementation of the program may be integrated from the very beginning.

• The decision to intervene is based on the totality of the indicators identified during the assessment process.

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

19

CHAPTER 3 : CHOICE OF THE TYPE OF DISTRIBUTION PROGRAM

I Establishing an intervention strategy

Strategy design is based on the causal analysis of malnutrition (see figure 1). The purpose of the ACFIN intervention is the prevention of malnutrition or the improvement of the general nutritional status of the affected population. Establishing an intervention strategy goes back to the basic definition of all the actions to implement in time and space to attain the program’s objectives.

• Complementarity of the intervention strategy: The food aid programs can ensure the immediate availability of food and/or reinforce the mechanisms of access to food. These programs are generally limited to a short period and are complementary to other actions carried out either at the same time as these programs or after them. During an acute nutritional emergency, simultaneous actions are led: in nutrition, in order to treat the people suffering from malnutrition, and in free food distribution, in order to provide a satisfactory nutritional allowance to the entire affected population. Parallel agricultural or economic support may be provided in order to contribute to the autonomy of the populations and to progressively decrease the needs for distributions. Other actions may be necessary in the health, water, and sanitation sectors if such needs are identified. These actions may also have a direct impact on the nutritional status of a population; in this way, having drinking water could prevent the appearance of diarrhea-related illnesses that would otherwise directly affect the nutritional status of the population. In a relatively stable context, food aid or its alternatives could respond not only to immediate causes but also to underlying causes of malnutrition and prevent a deterioration of the means of livelihood such as the decapitalisation of productive tools. The selected beneficiaries could receive food (or cash according to the nature of the needs) in exchange for restoration work on the collective infrastructures (roads, dykes, irrigation networks). The restoration work is determined in order to facilitate later agricultural or economic development. Interventions involving agricultural boosts could possibly relieve distribution, helping the populations re-establish their access to foodstuffs. In some cases food distribution may be necessary in conjunction with seed distributions, so as to protect the seeds from consumption and to reinforce the impact of the agricultural boost. If the crisis has caused a displacement situation, it is crucial to estimate future population movements as much as possible: return to their places of origin or establishing themselves in their places of displacement, etc. According to the situation, it may be necessary to plan assistance for return journeys or setting up home again (distribution of seeds and tools or construction materials), which would allow the beneficiaries of the program to have a free choice, unconstrained by a need to maintain the level of resources furnished by aid.

• Planning strategy: After specifying the specific objective of the program and the type of intervention, designing the strategy requires rigorous planning to maximize its impact according to the agricultural calendar (hunger gap, harvest), the rainy season (conditions of access), seasonal migration movements (pastoral populations, work opportunities), movement of displaced persons/refugees, etc (see Example 1). Retro planning thus determines the calendar of all the necessary activities according to the type of distribution chosen and is useful for adequately foreseeing the human and material needs. For more information, see the book, Food Security Assessments and Surveillance.

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

20

Example 1: Planning depends on the objective

The theoretical chart below presents the possible evolution of food and nutrition factors. The red line shows how food cover levels for the most vulnerable households may evolve over one year of poor harvest, and the yellow line shows how the prevalence of acute malnutrition might evolve over that same period. This represents a typical situation found in rural zones when the most vulnerable populations depend heavily on the level of their agricultural harvests (Taylor, 2004).

•

The type of intervention and its timing could be different according to the fixed objective: - If the food distribution begins in January it could prevent the deterioration of the nutritional status of the

population. - If the intervention begins in March it could prevent the sale of personal goods, i.e., the decapitalization of

households. - In April/May, distribution could prove useful to limit the emigration movements and permit the households to

maintain their work force for the preparation of agricultural planting. - After June/July, the intervention could consist of protecting the seeds to ensure an agricultural boost at the

moment of planting and increase the food availability during the hunger gap. - After the month of August, a cash distribution would be most appropriate, given the improved food availability in

the zone. Finally, it is important to include the conditions and steps for concluding the aid program in the intervention strategy: the exit strategy. This is made easier if the distribution program has been planned as a complement or a forerunner to a longer-term type of assistance that would contribute to the affected populations’ return to autonomy.

• Formalization of the strategy and monitoring indicators: It is the whole process that determines the intervention strategy; it should be formalized within a logical intervention framework12: this ensures coherence among the general objective, the specific objective, the expected results, and the activities to be led. (See Appendix 5 for an example of the logical framework of a direct distribution project.)

12 Refer to the book, Introduction to Food Security, for the use of a logical intervention framework.

80 60 40 20 0

Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May June July Aug Sept Oct

% food needs covered

% prevalence of acute malnutrition

Sale of pers. goods

Exceptional migration

harvests

harvests

Hunger gap

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

21

Each of these intervention phases should be monitored according to objectively verifiable indicators previously identified. The indicators should be defined during strategy development to guarantee the possibility of monitoring the program’s progress and pertinence: a must to ensure if the response is appropriate to the evolving needs of the population. The difficulty is in measuring the desired results in terms of prevention: it is hard to objectively measure the part of the productive capital which was not have been sold because of, for example, a distribution program. It is preferable to observe how the revenue sources have evolved by using qualitative investigations (post-distribution interviews) to see if the decapitalization phenomenon has indeed been stopped or reduced during the program: such a trend would show the program’s pertinence for this aspect. The indicators will therefore be different according to the objective and the type of program. In Table 4, below, the most frequently seen indicators are listed.

Table 4: Examples of distribution program monitoring indicators

Objectives and desired results

Objectively verifiable indicators Sources of verification

The targeted population receives food baskets or cash

• Cycles of distribution carried out

• Number of beneficiaries served

• Number of beneficiaries registered

• Quantity of food and/or cash distributed

• Number of food baskets provided

• % of beneficiaries who received the entire defined ration

• % of beneficiaries who are satisfied with the quality of the rations provided

• Activity report

• Distribution report

• Registration list

• Distribution and stock report

• Distribution report

• FBM13 and PDM14

• PDM

Food availability within the households is improved

• Use of the food basket

• Duration of the food basket

• Quality of diet

• % of the nutritional needs covered by the food basket

• PDM

• PDM

• PDM

• PDM

Access to foodstuffs is improved

• Use of the food basket

• Structure of the household expenses

• Quality of diet

• Evolution of the staple food prices

• PDM

• PDM

• PDM

• Market survey

Decapitalization of productive goods is reduced

• Evolution of the sale of goods in overall income

• Evolution of the herd size

• PDM, food security survey

• PDM, food security survey

The accessibility of the zone is improved (through a restoration project)

• Costs of transportation and of products

• Evolution of the number of merchants

• Food security survey and focus group discussions

The seeds are protected from food consumption (through food basket distribution)

• Area of sowed land

• Level of harvests

• Pre-harvest survey

• Post-harvest survey

Depending on the nature of the food crisis, the program will be defined with the goal of optimizing its impact within the affected population while minimizing the risks and potential adverse effects. The type of distribution must be selected according to set objectives, taking into account the advantages and disadvantages of each type of activity. Sections II and III, below, present the different types of distribution implemented by ACFIN according to whether they respond to a problematic of lack of food availability or a lack of food access.

13 FBM: Food Basket Monitoring is the verification of quantities for each foodstuff in the ration, performed at the exit of the distribution site (see Chapter 9). 14 PDM: Post-Distribution Monitoring is the follow-up after distribution via a sampling of the distribution beneficiaries (see Chapter 9).

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

22

II Responses to a lack of food availability

II.1 Free general (or targeted) food distribution II.1.1 Description One or several kinds of foodstuffs are freely distributed to populations affected by a lack of food availability in the

zone. The food basket is defined on the basis of the nutritional needs15 and the food security analysis of households, who may also be simultaneously suffering from access to food. This type of distribution can cover a selected population in a general manner or in a targeted manner according to the objective criteria (see Chapter 4, Section I) leading to a cover for the most vulnerable people. This type of targeting allows us to complement the nutrition programs during a significant nutritional crisis. General food distributions or distributions targeting a sector of the population (children under 5) allow the activities to be quickly set in motion without having to register the beneficiaries, while at the same time, effectively curbing a nutritional crisis as the following example shows:

Example 2: Free distribution to children under 5 years old

Southern Darfur – Sudan, September 2005 Close to Nyala, the capital of Southern Darfur, the Kalma camp housed approximately 70 to 90 thousand refugees fleeing combats and perpetrated violence for more than a year. Often following several displacements, these civilians found Kalma to be their ultimate refuge, finding access to assistance from humanitarian organizations, on which they were totally dependent in terms of medical care and food. Distributions were theoretically carried out every month. Even so, the rate of acute malnutrition during this period was constantly rising, reaching more than 20% among children under 5 years of age. After an investigation, the principle reason for the increased malnutrition was determined to be poor cover of the general distribution due to a lack of systematic registration of the new arrivals and to the logistical constraints that prevented proper supplying of full rations. It was decided to rapidly implement a targeted distribution to all children less than 5 years old (estimated to be about 15,000 people) with a mixed ration (equivalent to one porridge meal per day) in order to prevent the risks of malnutrition among this particularly vulnerable population. This targeted distribution, which lasted nearly 5 months, worked well in complement with the general distribution and the nutritional centers that could not cope with the growing number of cases of malnutrition.

If the food security analysis indicates a lack of access to foodstuffs—in other words, an excessively weak buying power resulting from a loss of revenues even though the level of availability is normal—a complementary or unique distribution of non-food products or cash is indicated to help improve the access to food (see below, Section III). II.1.2 Specific objectives:

- Ensure survival - Improve the nutritional status of the populations - Improve the household means of livelihood

II.1.3 Desired results:

- Availability of food in quality and in quantity - Reduction or prevention of malnutrition - Prevention of risky coping mechanisms - Reduction of the decapitalization of productive goods (livestock, tools) - Prevention of new, unsustainable economic activities or of falling into debt - Increase in the capacity of households to concentrate on productive activities

II.1.4 Order of program events: - Identify the needs of the population (see Chapter 2) - Identify the targeted population (see Chapter 4, Section I) - Determine the food rations to be provided (see Chapter 4, Section III) - Prepare the supply (see Chapter 4, section IV) - Establish distribution committees and awareness campaigns (see Chapter 4, Section V)

15 By ‘nutritional needs’ is meant the deficit between the current diet and the minimum required to remain in good health.

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

23

- Organize the team (see Chapter 4, Section VI) - Register the beneficiaries (see Chapter 5) - Determine the distribution systems and site installation (see Chapter 6) - Distribute food rations and manage flow (see Chapters 7 and 8) - Verify the quantities actually received and the use of the foodstuffs (see Chapter 9) - Evaluate the impact with regard to the fixed objectives (see Chapter 9)

II.1.5 Initial conditions: Context:

- Large-scale emergency - Sudden natural catastrophe - Significant movements of the population - Abnormally high or rising level of malnutrition - Disintegrated social structures, lack of reliability and equity of social structures (thereby not being able to

manage distribution themselves) Food market:

- Breakdown of production or market supply system - Absence or inefficacy of public organisms to regulate cereal markets - Elevated food prices and/or rapid inflation - Abnormally low availability of staple foods, absence of certain foodstuffs

Population: - Population cut off from its usual food source (refugees, displaced persons) - Population having lost its harvest or means of livelihood - Insufficient capacity of the families to produce or generate incomes (weak proportion of active workers in

the family, monoparental family) - Poor access to production means / access to land, forests, sea, possession of assets

Logistics/security: - Easy access to populations in terms of geography and security - Possible distribution sites are accessible and of adequate size

Table 5: Advantages and disadvantages of free distribution

Advantages Disadvantages • Immediate impact, rapid implementation

• Limited risks of aggravation of the nutritional situation

• Direct contact with beneficiaries and possibility of large-scale awareness

• Reduction of the risk of misappropriation of distributed goods (no intermediary)

• No discrimination for access to food

• Reaches the most vulnerable people or families

• Lowered food prices on the market => rise in buying power

• Stimulates local economy and production when the rations are purchased locally

• Can complement the goods available on the market

• Economic value of the food, making it possible to transfer expenses to other primary necessity stations

• Requires enough time and resources to select and register the beneficiaries

• Requires significant capacities of transportation and storage, high logistical costs

• Is work-intensive

• Sometimes requires repackaging the food into individual rations

• Does not always respects the dietary habits and customs compared to the lack of local availability

• Does not take into account the differences between villages and between families when there is no targeting

• Creates dependence on the donor when the donation is in pure form (incertitude, supply delays, types of rations and foodstuffs)

• Develops dependency and may cause lack of motivation for auto-production

• Risks keeping the populations where they are, or discouraging the return of refugees/displaced persons.

• Risks destabilizing the local markets (unbalanced offer or demand) and lowering the revenues of local producers.

• Creates security risks due to large quantities of foodstuffs

Action Contre la Faim Food Aid and Alternatives to Food Aid

24