Five Decades of Free Universal Primary or Basic Education in Nigeria and the Challenges of...

-

Upload

oluosokoya -

Category

Documents

-

view

446 -

download

8

Transcript of Five Decades of Free Universal Primary or Basic Education in Nigeria and the Challenges of...

Five Decades of free Universal Primary/Basic Education in Nigeria and the Challenges of Sustainability

By

DR. ISRAEL OPEOLU OSOKOYA

(Associate Professor of Education)

Dept. of Teacher Education,

University of Ibadan,

Ibadan.

A Public Lecture Delivered at the 10th Professor Kosemani Memorial Annual Lecture, University of Port-Harcourt, Rivers State – Nigeria on 30th October, 2012

1 of 21

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally primary or basic education means the type of education, in quality and concept

that is given in the first level of education. (UNICEF 1993, Osokoya 2011). The concept of first

level of education varies from country to country. In some countries of the world the first level

of education is of 6, 7, 8 or 9 years duration. In western Nigeria for example, the first level of

education was of 8 years duration prior to 1955 when it was reduced to six years. In Eastern

Region of the country, it remained 8-years until 1976, while the Northern Regional Government

maintained a 7-year primary education until 1976. Between 1976 and 1992 however, the scope

of first level of education in Nigeria as a nation was 6 years but this was later expanded to 9

years when basic education included the first three years of secondary school education.

Education at all levels is of great importance to every nation, developing, developed or under-

developed and thus attracts considerable attention over the ages. No doubt, at the family,

community, state, and federal government levels, education is discussed, planned and

processed. Education makes a person for it has a great influence on one’s values and attitudes.

Studies have shown that man’s attitudes, habits; values are gradually acquired over time

through his or her education. No wonder, the United Nations Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO) once observed that since wars begin in the minds of men it is also in the

minds of men that defenses of peace must be constructed. This illustrates the great potentials

of education for transforming the individual and the society.

A constant assessment of a country’s educational programme is considered necessary if the

nation is to develop and make progress economically, socially, politically and technologically.

This is probably why studies on free universal education particularly at the foundation level

became very popular in the last half-century as more and more western colonies gained

political independence. In fact, free universal basic education had become central to the overall

project of planned socio-economic development, modernization and democratization of the

Third World nations.

This lecture examines the ups and downs in the process of free universal primary/basic

education in the context of Nigeria’s chequered political history and in the light of its

2 of 21

geographical, social and political complexity. It also assessed the extent of success and

problems in the free universal basic education. In addition it offers suggestions for possible

sustainable paths to support future policy options,

THE EARLY YEARS.

The system of education in Nigeria before the early free universal primary education

programmes had been well documented by notable African Scholars as well as historians of

education. (Fafunwa 1974, Obanya 1992 and 2002, Ojerinde 1998, Okoro 2000, Osokoya 1987,

1989, 2001 and 2002; Tahir 2001, Yoloye 1993). Geographically, Nigeria can be conveniently

divided into two vegetational zones, namely; the equatorial forest (south) and the tropical

grassland north. The two zones had two broad types of educational process and pre-colonial

experience. In addition, they were two distinct protectorates of the British administration

before the unification of the country in 1914. Furthermore, they were administered

educationally in two different departments by the colonial government for one and half

decades after unification of the nation as it was only in July 1929 that the northern and

southern education departments were merged by ERJ Hussey the then Director of Education; It

is not surprising to observe therefore that five decades after attaining political independence,

the north and south Nigeria remained distinct socio-cultural, economic and political zones.

In the pre-colonial era, the northern zone was the home of a Flourishing Islamic empire. Islam

and Islamic education had developed in the area right from the 14th century. Islamic scholars

from Bornu in the east and Mali and Songhai in the west spread the religion in the zone.

Between 1452 and 1463, Yakubu the king of Kano has encouraged the spread of Islam. The

immigration of the Fulani from Mali during this early period made a mark in the development of

Islamic religion and education in the northern zone. Islamic education got its biggest boost in

early 19th century with the Jihad of Usman Dan Fodio. Thus with the arrival of the western

missionaries and the introduction of western education in Nigeria the Northern Emirs resisted

3 of 21

the spread of education into the northern zone as they felt that it was an imposition of another

religion in the area.

On the contrary, the south being predominantly pagan during the arrival of Christian

missionaries accepted Christianity and western education which the missionaries brought. The

initial resistance of the Emirs in the north to missionary education gradually resulted to

“educational imbalance” between North and South. The dilemma of closing the gap through

political means later gave rise to such educational policies including educationally

disadvantaged states, federal character, and quota system within a nation aspiring to be a just

and egalitarian society.

THE FOUNDATION OF WESTERN EDUCATION IN NIGERIA

At the invitation of the ex-slaves usually referred to as returnees from Sierra-Leone, Christian

missionaries arrived in Nigeria in1842. The first to come were the Reverend Thomas Birch

Freeman and Mr. and Mrs. William de Graft representing the Wesleyan Methodist Society. They

arrived at Badagry on 24th September 1842 where they built a mission house and a school. The

Wesleyan mission thus established the first western oriented school in Nigeria in 1842. It was

named Nursery of the infant church. The Church Missionary Society (CMS) which later played a

more prominent role in the development of education in the country arrived barely three

months after the arrival of the Wesleyan Missionary Society. The CMS represented by Rev.

Henry Townsend landed in Badagry on 19th December 1842. Rev. Townsend was later

accompanied by Rev. C.A. Gollmer and Rev. Ajayi Crowther and their wives.

They established a station in Badagry, and built two schools in 1842. The Presbyterian mission

followed with the establishment of a station at Calabar in 1846. The Southern Baptist

Convention also landed at Ijaiye Orile in 1853 and established a mission primary school. The

Roman Catholic joined the race when Padre Anthonio arrived in Lagos in 1868. There was an

expansion of western education to northern Nigeria during the Samuel Ajayi Crowther led first

and Second Niger expedition in 1854 and 1857 respectively. These Christian missions founded

elementary schools and built churches at their different locations on arrival in Nigeria (Osokoya

2003).

4 of 21

Thirty years after the arrival of the western missionaries, education in Nigeria was still a

monopoly of the church missions. It was only in the year 1872 that the colonial government

made available the sum of £30 to each of the three missionary societies involved in educational

activities in Lagos, the CMS, the Wesleyan Methodist and the Catholic to support their

educational activities (Fafunwa 1991). This perhaps marked the beginning of the grants-in-aid

to education which formed the major educational financing policy of the colonial government

and was subsequently adopted by the government of the First Republic of Nigeria. In 1877, the

grants-in-aid were increased to £200 per year for each of the three missions. The grants-in-aid

stood at that amount until 1882. (Osokoya 1999)

The school curriculum in the missionary/colonial education was heavily religious-biased,

intensely denominational and shallow in content. The school buildings, often the same building

as the churches, were ill-equipped. The blackboards, chalk and slates were in short supply and

the primers were largely religious tracts consisting of information unrelated to local

background. Literature in the vernacular was also scanty. (Fafunwa 1974)

In 1899, the first government primary school was opened in Lagos for the education of Muslim

children. By the year 1912, there were 150 primary schools under colonial government control

in the colony and protectorate of Southern Nigeria with a total enrolment of some 16,000

pupils. (Ukeje and Aisiku 1982). The story in the Northern protectorate was however different.

While western education became the prevalent and dominant type of education in the South,

Qur’anic education remained for many decades, the only kind of education in the north. In

1913, there were some 19,073 Qur’anic schools with an enrolment of 143,312 pupils in the

Northern Nigeria. (Fafunwa 1991). Missionary education progressed at a slow pace during this

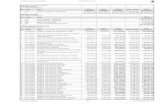

period in the northern protectorate. Table 1 shows the school population of the Northern

Protectorate.

5 of 21

Table 1: Schools in Northern Nigeria in 1913

S/N School owners No. of School No. of Pupils

1. CMS 13 -

2. Sudan United Mission 4 63

3. Sudan Interior Mission 7 -

4. Mennotite Brethen in Christ 3 38

5. Roman Catholic 3 60

6. Government Schools 12 527

7. Qur’anic Schools 19,073 143,312

Source: Fafunwa (1974) p. 109

THE FIRST UNIVERSAL EDUCATION SCHEME

The first UPE scheme in Nigeria came on the wake of self-government starting from the West in

1955. It was the era of resource control at the regional level and of healthy competition among

the three constituent regions-namely North, West and East.

The Action Group won the first election to the Western House of Assembly in 1952. In his

budget speech the leader of the Party, Chief Obafemi Awolowo gave priority to education and

health. In July 1952, the West Minister of Education, Chief S.O. Awokoya submitted a

comprehensive recommendation for the introduction of a free universal and compulsory

primary education for the region by 1955. The master plan for the programme included a

massive teacher training scheme, expansion of teacher training facilities as well as those of

6 of 21

secondary and technical education. Secondary modern school was planned to take care of

those who could not find placement in the secondary institution.

Before the Launching of the scheme, the various educational problems facing the region were

outlined and efforts were made to solve such problems between 1952 and 1954. The regional

government also embarked upon an intensive public enlightenment to seek for the parents’ co-

operation in order to release their wards for the free education at the primary level. The mass

media were used for the massive awareness of the relative importance of education especially

among the illiterate parents. Other preparations included massive training of teachers for

primary school level. Teachers Grade Three institutions were established to supplement the

teacher education programmes at the Higher Elementary level. In addition, school buildings

were constructed to accommodate the teaming population of children that would enjoy the

free education.

On 17th January 1955, the scheme was officially launched with the word compulsory deleted but

replaced with universal. In that month, some 811,000 children turned up for UPE. By 1958,

more than one million children were enrolled. The number of primary school teachers rose

from 17,000 in 1954 to 27,000 in 1955. About 90 percent of the regional budget was spent on

education in 1955. By 1960, over one million, one hundred thousand children were enrolled.

This represented more than 90 percent of children of school age in the Western Region. No

doubt, the scheme popularized education in the region and scholars regarded it as a

breakthrough in popular education not only in Nigeria but in black Africa.

The impact of this scheme on primary school enrolment in that region was impressive and

immediate as could be observed in the table 2:

7 of 21

Table 2: School Enrolment in Western Nigeria 1954-1959

Year No. of Primary School No. of Pupils

1954 - 456,600

1955 6,407 908,022

1956 6,603 908,022

1957 6,628 982,755

1958 6,670 1,037,755

1959 6,518 1,080,303

Source: Western region of Nigeria: Triennial Report on Education Paper No. 11 of 1959. Ibadan

Government Press

The scheme however had its problems. Firstly, enrolment projections were grossly under-

estimated. Records showed that while provisions were made for 170,000 children, 391,895

showed up in the first day of school in January 1955. One major reason for this was that over-

age and under-age children also turned up for registration. Another reason was that as a result

of falsification of population census which was rampart in Nigeria for political reasons, accurate

population projection was impossible. The Scheme also gave rise to a noticeable falling

standard in primary school education in the region.

The Banjo Commission set up six years after the introduction of the scheme to examine the

causes of the major problems of the scheme documented among others

Large number of untrained teachers

Problems of continuity in staffing

Too large classes

Presence of under-age children

Unsatisfactory syllabus

Inadequate supervision of schools

8 of 21

A BOLD STEP BY EASTERN REGIONAL GOVERNMENT

The Eastern Nigerian government, in keeping with the healthy competition of the time,

proposed the introduction of the universal primary education on a large scale. It was an eight

year free education plan to start from 1957. Educators claimed that it was a hurried plan that

lacked adequate preparations. At the initial launching of the Scheme in February 1957,

practically all the new schools were staffed by untrained teachers. Besides, building facilities

were grossly inadequate as temporary buildings and shelters were used to accommodate the

teaming school population. Funding the scheme particularly in the area of paying teachers’

salaries became a major problem. This coupled with the strong opposition of the Roman

Catholic Mission which owned more than sixty percent of the schools became a major force

hindering its proper implementation. All the same, the scheme opened the hearts of the people

to the need for universal education as the community gave massive support to the scheme.

Thus the region remained almost at par with the West in the promotion of education.

The Lagos town council which had assumed full responsibility for education in Lagos during the

period launched an 8-year UPE scheme in January 1957, two years after the launching of the

Western Region’s scheme. Lagos UPE though was administered by the Lagos City Council, was

actually sponsored by the Federal Ministry of Education. Hence Lagos unlike the Western and

Eastern Regions did not face financial difficulties. Money was available to build upon the

existing sites while teachers were attracted to the urban life of the Federal Capital. The Federal

Government Teacher training college at Surulere was expanded, and two voluntary agency

teacher training colleges were established in 1958 and 1959.Between 1956 and 1966, the

primary school enrolment rose astronomically as could be observed in this Table 3:

Table 3: Schools in Lagos 1956-1966

9 of 21

Year No. of Schools Enrolment No. of Teachers

1956 96 50, 182 1, 646

1966 129 140,000 4,200

The Northern Regional Government remained silent on Universal Education until the scheme

was launched by the Federal Military Government in September 1976.

However, during this period, enrolment in primary education in the region rose steadily from

122,055 in 1952 to 518,864 in 1966

Table 4: School Enrolment in Northern Nigeria 1952-1966

Year Primary School Enrolment

1952 122,055

1953 142,477

1954 153,686

1955 168,521

1956 185, 484

1957 205, 769

1958 230,000

1959 250,000

1960 282,849

1961 316,264

1962 359,934

1963 410,706

1965 492,510

1966 518,864

UNIVERSAL EDUCATION IN THE POST-WAR RECONSTRUCTION ERA

10 of 21

The period 1966-1977 brought about the centralization of education policies. The civil war of

1967-1970 had a devastating effect in the east where schools were destroyed and most

households became impoverished. To soften the effects of the war, the federal government

embarked on a policy of reconciliation, reconstruction and rehabilitation with the creation of 12

states in 1967, and additional seven states in 1976. Government also engaged in rapid

expansion of educational institutions with the objective of improving wider access to education

at all levels. This was a period of oil boom in Nigeria. Petroleum accounted for almost 90 per

cent of foreign exchange earnings and 85 per cent of total exports {Ekpo et al 2000}.

This wealth impacted positively on the educational system in many ways. The Federal

government implemented the Udoji Salary Review Commission of 1975. This went a long way

to improve the lot of teachers and it also attracted many graduates to the teaching profession.

The Federal Government took over the financing of teacher education and launched the

Universal Primary Education nationwide in 1976. The aim was to improve the overall school

enrolment and to correct the educational imbalance precisely between the southern and

northern parts of Nigeria

The planning was guided by the principles that the Federal Military Government would solely

finance the project while the state governments would act as agents. Preparations were put in

place for training of teachers, construction of classrooms while over one billion naira was

budgeted for the commencement of the programme. The programme took off with a total

enrolment of 3 million pupils into primary school enrolment of about 8.1 million (Taiwo

1981).By 1981, the figure had risen to over fifteen million as shown in table 5.

Table 5: Enrolment of pupils into Primary Schools in Nigeria 1977-1981

11 of 21

Year No. of Pupils

1977 8,114,307

1978 9,845,838

1979 11,457,772

1980 13,546,312

1981 15,664,424

Source: Federal Ministry of Education Planning Statistics Unit, Lagos.

Unfortunately, the economic depression of the 1980’s brought a sharp decline in resources

allocated to education hence primary education subsequently faced many problems and

challenges. Such problems inadequacy of teaching personnel, infrastructure, finance and

educational imbalance. The problems of teaching personnel comprised teacher quality,

quantity, incentive and self-image and the social image of the teacher. It was evident from the

inception of the UPE project that the available teachers could not cope with the staggering

numbers of pupils. This factor led to the merging of classes under single teacher thus leading to

a disproportionate teacher pupil ratio. The problems that relate to teacher incentive cannot be

regarded as less important. The poor salary of teachers led to non-commitment to work as well

as attrition from teaching appointment. Most of the trained teachers serving in the rural areas

massively drifted to the urban centres in search of more lucrative jobs. The problems of

infrastructure were very glaring in most of the states. Acute shortage of classrooms gave rise to

two or three shifts school arrangements in the urban centres. Furthermore, sub-standard

school buildings were constructed in many states by the in-experienced and inefficient

indigenous contractors.

To worsen the situation, the Federal Government that initially decided to shoulder the entire

UPE expenses soon realized that it was not feasible to do so. The Federal Government therefore

involved the states and local governments in financing UPE. Records showed that even though

the Federal Government strived to meet her obligations, most of the states and Local

governments did not. The problem became more acute when some states and local

governments diverted educational funds to other areas. All these problems led to a drastic

decline in the quality and quantity of UPE in Nigeria by the middle of 1980s and it became

12 of 21

necessary to take a revolutionary step in Nigeria’s aspiration and commitment to meet the

target date for attaining education for all by 2000 (which was later shifted to 2015).

SHIFT FROM UPE TO UBE

The UBE (Universal Basic Education) in Nigeria is a product of its time, Nigeria being a signatory

to the 1990 Jomtien Declaration, fully participated in the various deliberations concerning

Education for All (EFA). The Federal Government therefore decided to officially launch the

Universal Basic Education in the country on September 30, 1999, while the implementation

guidelines were published in 2000. The objective of the programme was to lay a solid

foundation for a life-long learning for all Nigerians by ensuring the acquisition of appropriate

levels of literacy, numeracy, manipulative as well as communicative life skills (FME Guidelines

for UBE 2006). The Universal Basic Education became compulsory for all children of school age

regardless of sex, religion or states of origin as from Friday May 28, 2004. (Osokoya 2008)

At the inception of the UBE programme in 1999, the nations’ literacy rate was estimated to be

52% (Osokoya 2008). Education statistics for the year showed that only 14.1 million children

were enrolled into primary schools out of the 21 million children of school-going age. The

transition rate to Junior Secondary School was 43.5%. There were in addition, substantial short

coming in Nigeria’s institutional and personnel capacities for the delivery of a sound

educational foundation for all citizens. In particular, there were widespread disparities both in

quality and access across the nation. Education statistics further indicated that the available

infrastructural facilities, teaching and learning materials as well as qualified teachers were

grossly inadequate.

The major achievement of UBE is that it has remained in force despite all odds and tumultuous

political terrain in Nigeria, The achievement on the ground of increase in enrolment has been

well captured in the 2005 MDGs (Millenium Development Goals) report of the Nigerian

government briefly cited below:

Trends in enrolment from 1999 to 2003 show that on an average enrolment consistently

increased over the years for both males and females from 7%, 8%, 11% and 44% in

13 of 21

2000, 2001, 2002 and 2003 respectively. Primary schools rates were, however

consistently higher for boys than for girls

The efficiency of primary education has improved over the years.

The primary-six completion rate increased steadily from 65% in 1998 to 83% in 2001. It

however declined in 2002 to shoot up to 94% in 2003.

The implementation of the Universal Basic Education in addition, has brought remarkable

developments in such aspects as academic, social and physical educational spheres. The

content of elementary education in Nigeria witnessed many changes both in variety and

intensity since then. It should be remembered that the advent of the National Policy on

Education in 1977 and the revisions in 1981, 1998 and 2004 respectively brought with it the

need to radically change the school curriculum to meet the new philosophy of Nigerian

education. Appropriate curriculum contents were therefore developed for the school system in

the recent past aimed at improving universal education to fit into the dynamics of current

events and of the immediate future in Nigeria. Of particular importance is the issue of

citizenship education which has been infused in to the primary school curriculum. Topics

emphasized include Nigerian constitution, tenets of War Against Indiscipline (WAI) Mass

Mobilization for Social Justice and Economic Recovery (MAMSER) principles and the high way

code. Other topics include home economics, introductory technology, elementary science,

population and family life education, drug abuse education and environmental education.

Relevant components of these new subjects were infused into the existing school subjects

through the process of integrated approach to avoid over-loading of the school curricula.

In the area of personnel development, more teachers were trained at the colleges of education

and universities in most of the states while the untrained teachers were encouraged to undergo

teacher training courses. In addition, the Federal Government has under the Millennium

Development Goals Project directed the National Teachers’ Institute by the Act No. 7 of 1978 to

organize programmes for upgrading and updating practising teachers. Many workshops had

been organized on Innovative techniques of teaching and Improvisation of Instructional

materials in the six geo-political zones since the implementation of UBE. Furthermore the

14 of 21

Nigerian Certificate of Education (NCE) was fixed as the minimum teaching qualification in

Nigeria. In the bid to encourage appropriate textual materials with illustrations taken from the

locality, indigenous authors were sensitized and encouraged to produce instructional materials

by the Federal Government through the establishment of Book Development Centre based at

the Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council (NERDC). Another major academic

landmark was the introduction of the Continuous Assessment practice into the UBE Scheme.

The National Policy of Education laid strong emphasis on the use of continuous assessment

practice at the various levels of Educational system, in preference to the former practice of

single terminal examinations. Certification at the primary school level is now based on

continuous assessment rather than on a primary school leaving certificate examination.

Continuous assessment is viewed as the method of finding out what the students have gained

from learning activities in terms of knowledge, thinking and reasoning, character development

and industry. It takes into account the cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains of the

pupils. In the cognitive domain, teachers assess the pupil’s knowledge of previously learned

materials, his understanding and the application of materials in solving problems. They also

attempt to evaluate the extent to which the child can make inference and assumptions from

the learned materials. Pupils’ feelings, attitudes, emotions and other social behaviour are

assessed in the affective domain while the interest is to evaluate the pupil’s manipulative skills

in the psychomotor domain. Manipulative skills simply refer to the way the child makes proper

use of his limbs and body and the degree of coordination involved in skilled activities.

The use of continuous assessment practice gives room for teachers to combine the scores

attained by each pupil in the class assignments, homework, weekly tests, examinations and

various other sources applied during class instructions to obtain the overall score for a given

period. With such overall scores, it would be possible to diagnose problems in the course of

instruction. Teachers would therefore be in a better position to help their pupils overcome their

individual problems. It also gives room for teachers to assess their own performance and

effectiveness on the job. This will no doubt lead to possible improvement or innovations of

teaching techniques. Furthermore, continuous assessment gives teachers the opportunity to

15 of 21

make a critical study of the character, temperament, interest, attitude and adjustment of the

pupils, which would form part of the final assessment of the pupils. Such assessment and

information will no doubt lead to better understanding of the pupils and with the aid of proper

guidance and counseling, students would be able to overcome their difficulties and improve

their performance.

The Universal Basic Education in Nigeria is also geared towards improving the socio-economic

condition of the indigenous rural population in Nigeria. Such rural population include the

nomadic pastoralists and the artisan migrant fishermen who are difficult to educate as evident

by their participation in existing formal and non-formal education programmes which were

abysmally low, as their literacy rate ranged between 0.2% and 2.0% (Tahir 2003). In the bid to

provide universal education to all Nigerian citizens, the Federal Government launched the

Nomadic Education Scheme on 4th November 1986. As a follow up to this, by Decree no. 41 of

December 1989, the Federal Government established the National Commission for Nomadic

Education (NCNE) and charged it with the responsibility of implementing the Nomadic

Education in the country. The commission on Nomadic Education had four departments

namely:

Planning, Research and Statistics

Personnel Management

Monitoring and Evaluation

Finance and Supplier.

In 1996, the commission had 42 staff members, 54 field officers in eighteen different units

through which they relate very closely with three University in Nigeria namely: Usman Dan

Fodio University Sokoto for Curriculum Development, Universities of Maiduguri for Education

Training and Outreach and University of Jos for Research and Evaluation (Osokoya 2005). In

addition, the commission worked through the states Nomadic Education

Units/Agencies/Directorates which were either affiliated to the participation state ministries of

Education or State Primary Education Boards in Implementing Nomadic Education programmes

at the state, local government and community levels. Student-teacher ratio increased annually

16 of 21

from 1999 to 2005 but became more pronounced between 2003 and 2005. This suggests that

more nomads are interested in education but teachers are lacking.

Physical development refers to the development of the physical and spatial enablers of

teaching and learning. It includes the refurbishing of classrooms, libraries, laboratories,

workshops, playfields, school farms and gardens as well as provisions for pupils daily use as

electricity, water and sanitation. At the inception of the UBE programme in 1999, it was realized

that such basic school level infrastructure were not only in short supply, but that the available

ones had deterioted. Since the inception of the UBE programme, the Federal Government had

been involved in the construction of additional classrooms, offices, stores and toilets in the

public primary schools in the various states.

Educational researchers however still claim that there is inadequacy in the number of primary

school to support full enrolment of primary-school-age children [Okebukola (2008), Nwagwu

(2010)]. Worse hit are the urban areas with dense population of children resulting in high

pupil/teacher ratio. The shortage of schools and especially classrooms manifests in children

receiving instruction under harsh conditions.

Furthermore, a major factor in the success of UBE scheme is the teacher. There is a plethora of

evidence (UNESCO, 2007) suggesting that teacher quantity, quality and motivation exert

noteworthy effects on a host of school variables. These include enrolment, participation and

achievement of pupils. The shortfall in teacher number translates to high pupil-teacher ratio

and severe stress on teachers on ground. Inadequacy in the number of teachers for the UBE

programme could therefore account for the declining quality of the products. In addition, the

existing model and practice of teacher education with particular reference to the use of

outreach and sandwich centres has weak pedagogical bases and frameworks. Evidences abound

that the input into many of these part-time programmes is of doubtful quality. Irregularity in

the payment of teachers’ salaries that was a distinctive feature of the 90’s is fast fading.

Notwithstanding this boost, teachers in Nigeria remain poorly motivated.

17 of 21

TOWARDS A PATH FOR THE SUSTAINABILITY OF UBE IN NIGERIA

The path for sustainability of UBE in Nigeria lies in avoiding the mistakes of the past universal

education and to provide solutions to the current challenges of the project. The following

suggestions are therefore made to build sustainability safeguards into the UBE scheme.

Political Stability and the social mobilization: Nigeria seems to be steadily returning to political

stability and economic sufficiency since the new civilian dispensation. Its debt burden has been

considerably reduced while its income has been considerably enhanced by the hikes in

petroleum prices. This has given rise to some on-going social reforms in many aspects of our

national life. Maintenance of political stability should be regarded as a pre-condition for success

to be achieved in future UBE. In addition to this, Nigerian Politicians should endeavour to build

a strong political support for the UBE programme. Governments at all levels, federal state and

local, should provide adequate social mobilization to ensure a satisfactory level of popular will

for the programme. Universalizing education should be fully accepted by Nigerian populace and

adequately supported by all. In order to achieve a strong civil society involvement UBE should

be highly decentralized for participatory management, working in the principles of popular will

and people’s ownership. (Obanya 2009)

True Federalism Challenge: It should be borne in mind that the constitutional requirement for

the governance of education in Nigeria confers the control of primary education to local

governments. The UBE scheme in the country is a federally-led intervention. This had led to

conflicts of power struggle between the local and state governments as the state governmnet’s

stranglehold on local governments is total. It is therefore necessary that the management and

policy structure of UBE be streamlined to make for greater harmonization at the three tiers of

government. True federalism should be allowed to take root in the planning and delivery of

UBE. To this end, there is the need to restore the key role of the local government in delivering

basic education giving them the technical and financial empowerment to take on the

responsibility.

Adequate Funding: Adequate funding and the judicious use of available fund had been seen as

a major factor for the failures of the previous universal education schemes. Future success and

18 of 21

sustainability of the UBE scheme lies in improved fund management, particularly on grounds of

transparency and accountability. UBE should be correctly costed and resourced. Furthermore,

there should be timely release of funds and implementers must endeavour to use the funds for

the purpose for which they are intended.

Data Problem: A major problem faced by educational planners in Nigeria had been the inability

to obtain correct and up-to-date statistical data needed for planning. A population census in

Nigeria has always been a politically charged issue. This has continually made projections based

on population figures unrealistic. Nigerians need to rethink and change their attitude towards

record keeping and imitate the developed countries in using accurate facts and figures for

planning and decision making. To this end, government should ensure accurate data collection

through Education Management Information System (EMIS)

CONCLUSION

Universalisation of education at the primary level is not new to Nigeria. In the mid-fifties, the

two regional governments in the east and west of the country embarked on Universal Primary

Education Scheme. The Western Region made a better success of it than the Eastern Region.

Both regional attempts however could not be sustained. Explosion in enrolment coupled with

poor economic environment constituted huge constraints to such a laudable programme.

The first national attempt at providing universal access to primary education was in 1976. This,

in spite of better economic climate at its inception, was also not sustained. Many reasons were

attributed to its non-sustainability. It however succeeded in boosting enrolment in primary

education.

This second effort at introducing Universal Basic Education nationwide could not have come at

a better time. With the democratic dispensation, there is evidence to show political

commitment and determination to succeed. We however need to take some pre-cautions

including

19 of 21

Taking appropriate steps to ensure that the various agencies controlling the policy

directions on the programme are operating in harmony, ensuring that all resources are

brought together for a common cause, which is the promotion of basic education

Our emphasis should not be limited to physical access issues; rather we should focus

more on equity, relevance, quality and efficiency challenges.

Social-will i.e. readiness of the populace to be carried along in the UBE process, as a

result of government’s readiness to carry the people along.

Sustainable funding

Systematic monitoring

Poor curriculum delivery

Teacher quality and quantity

REFERENCES

Adewunmi, J.A. (2001): Analysis of Universal Primary Education (UPE) and the lessons for

the Universal Basic Education (UBE) Paper Presented at the UBE Local Level Policy

Dialogue at Ilorin.

Ajayi, T. (2001): Effective Planning Strategies for UBE Programme in UBE Forum Vol. 1 No

1.

Fafunwa, A.B. (1974): History of Education in Nigeria. London, George Allen Unwin

Federal Ministry of Education (2000): Guidelines for Universal Basic Education. Abuja,

Government Printers.

Federal Ministry of Education (2001): UBE Forum. Journal of Basic Education in Nigeria.

20 of 21

Federal Ministry of Education (2001): Universal Basic Education Digest. A newsletter of

Basic Education in Nigeria.

Federal Ministry of Education (2003): A Handbook of Information of Basic Education in

Nigeria Abuja Government Press.

Federal Ministry of Education (2004): National Policy on Education (Revised) Lagos,

Government Press.

Obanya PAI (2007): Thinking and Talking Education. Ibadan, Evans Brothers Nigeria Ltd.

Obanya PAI (2009): Dreaming Living and Doing Education. Ibadan Educational Research and

Study Group. Institute of Education University of Ibadan.

Obanya, PAI. (2002): Revitalizing Education in Africa. Ibadan Stirling-Horden Publishers Nig Ltd.

Okoro, D.C.U. (2000): Basic Education Emerging Issues, Challenges and Constraints in UNESCO

Abuja Office. The State of Education in Nigeria.

Osokoya, I.O (2010): History and Policy of Nigeria Education in World Perspective Ibadan AMD

Publishers.

Osokoya, I.O. (2004): 6-3-3-4 Education in Nigeria, History, Strategies, Issues and Problems.

Ibadan, Laurel Educational Publishers Ltd.

Tahir, GO. (2001): Federal Government Intervention in Universal Basic Education. UBE

FORUM. A Journal of Basic Education in Nigeria.

Yoloye, E.A. (Ed) (2004): Burning Issues in Nigerian Education. Ibadan Wemilore Press Nig.

Ltd.

Yoloye, E.A. (Ed) (2010): Vision 20-2020 The Educational Imperatives. Lagos, The CIBN

Press Ltd.

21 of 21