Edwards Amasa Park · 2020-04-28 · ./01 23 45 556 4 47./01 0## 23 468356 4 8 ChapterOne...

Transcript of Edwards Amasa Park · 2020-04-28 · ./01 23 45 556 4 47./01 0## 23 468356 4 8 ChapterOne...

Charles W. Phillips

Edwards Amasa ParkThe Last Edwardsean

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

New Directions in Jonathan Edwards Studies

Edited byHarry S. Stout, Kenneth P. Minkemaand Adriaan C. Neele

Volume 4

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Charles W. Phillips

Edwards Amasa Park

The Last Edwardsean

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

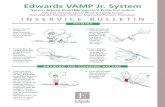

With one illustration

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek:The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie;detailed bibliographic data available online: http://dnb.de.

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D-37073 GöttingenAll rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or byany means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any informationstorage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Typesetting: 3w+p GmbH, RimparPrinted and bound: Hubert & Co. BuchPartner, GöttingenPrinted in the EU.

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com

ISSN 2566-7319ISBN 978-3-647-56030-4

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

For Debs, without whom nothing.

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Acknowledgements

My debts related to this monograph are simply too large to pay, and so a simpleacknowledgement must stand-in for the greater appreciation I intend. To DavidBebbington, for exemplifying the highest levels of scholarship and courtesy—toMark Noll, first for helping to generate with David the original idea for this workand then for not strenuously avoiding any claims to paternity later—to KenMinkema for his on-going encouragement and support in publication—toJonathan Yeager for allowing me to inflict some of these ideas on his class—toDavid Denmark and the Maclellan family for allowing me occasional dis-appearances into the nineteenth century—and, finally, to my dear wife andchildren for allowingme frequent disappearances altogether: you all have put meforever under obligation.

Additionally, grateful thanks for their assistance are extended to the librariansand archivists of the Andover-Harvard Theological Library at Harvard Uni-versity, the Franklin Trask Library at Andover-Newton Theological School, theOliver Wendell Holmes Library at Phillips Academy (Andover), the Congrega-tional Library (Boston), the Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston), theAndover Historical Society, the John Hay Library at Brown University, the YaleUniversity Libraries, the Heard Divinity Library at Vanderbilt University, theBurke Library at Union Seminary (New York), the Library at Oberlin College, theLibrary of Congress, the Bodleian Library and the Rhodes House Library of theUniversity of Oxford, the Library of the University of Glasgow, and the NewCollege Library of the University of Edinburgh. Material from the Andover-Harvard Theological Library is used by permission.

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Contents

Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Abbreviations in the Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Chapter OneIntroduction: Edwards A. Park and The Creative Conservation of theNew England Theology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Chapter TwoThe Arc of New England Theology: From Edwards to Edwards AmasaPark . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Chapter ThreeFraming the New England Theology: Intellectual Influences on Park’sDevelopment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Chapter Four‘The Theology of the Intellect and That of the Feelings’: RhetoricalStrategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

Chapter FiveDefining The New England Theology: The Creation of anAuthenticating Tradition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141

Chapter SixDefending The New England Theology: Competing Methods andNarratives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 171

Chapter SevenConclusion: The Last Edwardsean . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Bibliographical Note . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 219

Select Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221Edwards Amasa Park Primary Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221Papers and Correspondence (by Repository) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221Journal Articles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221Articles in Published Works . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222Other Publications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222Student Notebooks of Park’s Andover Lectures . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223

Index of Names . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225

Contents10

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Abbreviations in the Notes

ABR American Biblical RepositoryAR Andover ReviewATR American Theological ReviewBRPR Biblical Repertory and Princeton ReviewBS Bibliotheca SacraCH Charles Hodge (1797–1878)EAP Edwards Amasa Park (1808–1900)HBS Henry Boynton Smith (1815–1877)NE New Englander

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

My father studied theology with Dr.Emmons. His father studied with Dr.Smalley, and his father with PresidentEdwards. I therefore can claim a rightto the Edwardean theology by what sci-entists would call the law of heredity.

—Edwards Amasa Park, ‘Address atthe Alumni Dinner’, 1881

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Chapter One

Introduction:Edwards A. Park andThe Creative Conservation of the New England Theology

Reigning in the days of his power as the great champion of Edwardsean Cal-vinism—the consummate mid–century Congregationalist, a master teacher ofpreachers at Andover seminary, linked by name and by marriage to JonathanEdwards himself—Edwards Amasa Park is now awarded not much more than apassing footnote or an occasional essay in the nineteenth century’s grand story ofthe New England Theology’s decisive shaping of evangelicalism among English-speaking peoples. Born in 1808 and dying in 1900, Park was a public figure of notefor almost seven decades, in a long professional career that was often marked bycontentious controversies over theological views, seminary politics and de-nominational creeds. Just as his nineteenth-century contemporaries criticisedhim for being either inadequately conservative or insufficiently liberal, Park hasbeen similarly condemned by historians for more than a century since his deathas either a doctrinal relic who outlived his time, or as a proto-liberal who lackedthe courage to make good on his intuitions. Whether as preacher, rhetorician,theologian, editor, biographer, historian, redactor, or disputant, Edwards Parkhas only infrequently been accorded the prominence in retrospect that came tohim in abundance in his lifetime. Once, in the words of an Andover memoirist,Park’s fame was great in Zion.1

A celebrated professor at the first and largest seminary in the land for overforty-five years, editor of the influential Bibliotheca Sacra for forty, distinguishedpublic theologian in the prominent Abbot chair for almost thirty-five—fewat thetime of Park’s death would have challenged his description by his eulogists as onewho ‘since Edwards…has hardly been surpassed in acumen’,2 who preached ‘the

1 Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Chapters from a Life (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1897), p. 196.2 George P. Fisher, The Congregationalist, 14 June 1900, p. 871.

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

greatest sermon ever preached in Boston’,3who as ‘a lecturer had no superior’, sothat ‘students from other seminaries would come from far and near’ to hear him,4

who was ‘one of the greatest teachers of theology…this country has known’.5

Williston Walker, the premier historian of Congregationalism, asserted beforePark’s death that his ‘conception of the NewEngland theology became part of themental furniture of more theological students than any other Congregationalisthas ever taught’.6 At the end of Park’s life, there was little question of hisgreatness.

It may be, then, that Edwards Park’s lifework is as interesting now as it isneglected. He wrote in 1854, at the height of his significance as a theologian andpublic churchman, that his ‘Edwardean definitions were introduced not tosubvert, but to conserve the substance of the old Calvinistic faith, and to prolongits influence over the minds of an intelligent community’.7 Park promulgated a‘Calvinism in an improved form’, the New England Theology, that in his viewconserved the essential truth of his inherited Edwardsean Calvinism by findingfor it newmodes of expression thatmet the contemporary tests of reasonablenessand perspicuity.8 He drew creatively on a broad palette of the intellectual re-sources he had at hand in order to re-cast his inherited Hopkinsian revivalism inthe new conditions of the middle of the nineteenth century. The New Rhetoricand common-sense epistemology from the Scottish Enlightenment, historicistmethodology from the German mediating theologians, the fresh affective sen-sibilities awash in American culture and nurtured by the bracing stream ofRomanticism from England—all were used by Park to create a broadly relevantorthodox synthesis in the innovative spirit of Jonathan Edwards and Edwards’sNew Divinity successors: Bellamy, Hopkins, and Emmons, Park’s own revivalistforebears fromhis boyhood. In the very same innovative spirit as Edwards and hishardy followers, Park adaptively built a fresh and synthetic tradition with whichto defend evangelical Calvinism from the new philosophical and epistemologicalchallenges of his own day, by meeting contemporary tests of reasonableness andfairness. That tradition—theNew England Theology—came with its own heroesand a historical narrative wound tightly around the sturdy armature of essentially

3 George A. Gordon, The Congregationalist, 13 June 1903, p. 840.4 George B. Front to Owen Gates, circa 1928 (MS in Trask Library, Andover-Newton TheologicalSchool).

5 Richard Salter Storrs, The Congregationalist, 7 June 1900, p. 831.6 Williston Walker, A History of the Congregational Church in the United States (Boston: ThePilgrim Press, 1894), p. 353.

7 EAP, ‘The Fitness of the Church to a Constitution of Renewed Men’, in Addresses of Rev. Drs.Park, Post and Bacon at the Anniversary of the American Congregational Union, May, 1854(New York: Clark, Austin and Smith, 1854), p. 41 [emphasis in original].

8 EAP, ‘New England Theology; with Comments on a Third Article in the Biblical Repertory andPrinceton Review, Relating to a Convention Sermon’, BS 9 (1852), p. 184.

Chapter One16

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Hopkinsian theological practices. It seamlessly brought Awakenings-past alive bysupplying a next generation of Edwardsean revivalists with handy apologetic andrhetorical tools. It is, in turn, fair that Park be judged on the success of this life-long project of creative conservation.

Andover seminary had been founded near the start of the nineteenth centuryas a bastion of orthodoxy to contend against Harvard, and in the decades sur-rounding the American Civil War, Park served as its public champion. Deployinghis NewEngland Theology and taking on all comers, Edwards Amasa Park led the‘sacred West Point of orthodoxy’.9 Dominating Andover with a ‘massive andstriking personality’, Park’s professional life in the Bartlet chair of sacred rhetoricand later in the Abbot chair of Christian theology affirmed the primary test ofgenuine Edwardsean revivalism—that the wills of hearers be moved to action.10

Always attentive to the premise that the effectiveness of the preacher was afunction of both content and presentation, Park taught creative rhetoricalstrategies to ensure that the preaching of ancient truths should be freshly per-suasive. As a powerful revival preacher before his career at Andover and as agifted theological disputant during it, Park defined a core New England Theologythat in its matter preserved essential biblical content and that in its practice wasadapted tomove the unregenerate—the very same project, after all, that had beenthe work of Jonathan Edwards and his New Divinity heirs, because this was theonly kind of preaching that produced regeneration and holiness in the church.11

It seems appropriate and timely to conduct a reappraisal of Edwards Park’sstanding in the historical course of nineteenth-century American theology byundertaking something like an intellectual biography. In order to begin, twoframing discussions are in order. First, because of Park’s close identification withrevivalist Edwardsean Calvinism, an initial rapid transit through the distinctivesof this larger movement might provide a useful context at the start for the entireundertaking, thoughmore detailed consideration will be required later. This firstframe is also helpful for the second, an overview of Park’s status to date in theprior historical evaluations of New England theology. This historiographic effortmay seem to some like palaeontology, but the task is necessary to set the stage fora fresh evaluation of Park. Happily, if unsurprisingly, each of these frames ofreference have the same starting point.

9 Nathan Lord, A Letter to the Rev. Daniel Dana, D.D., on Professor Park’s Theology of NewEngland, by Nathan Lord, President of Dartmouth College (Boston: Crocker and Brewster,1852), p. 51; see alsoHarry S. Stout,TheNewEngland Soul (NewHaven: Yale University Press,1986), p. 38.

10 Edward Dwight Eaton to Owen Gates, 16 November 1928 (MS in Trask Library, Andover-Newton Theological School).

11 Park preached during a four-month revival in Braintree, Massachusetts, in 1831; see FrankHugh Foster,The Life of Edwards Amasa Park (NewYork: FlemingH. Revell, 1936), pp. 67–69.

Introduction 17

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) was the primary spokesperson for the wide-spread religious awakening which was first associated with his own parish inNorthampton, Massachusetts, in 1734–1735 and which in the next decade en-veloped much of New England.12 His own theological work was a complex re-statement of traditional Reformed doctrines invigorated by a philosophicalidealism that grew from his profound theocentric religious experience, and by anEnlightenment-inspired confidence in reason, empiricism and Lockeansensationalism.13 Edwards’s insistence on genuine experiential religion con-stituted a rejection of the older view in New England of a covenanted com-monwealth—one expressed by the Half-Way Covenant as drafted according tothe principles of his grandfather, Solomon Stoddard (1643–1729)—and his in-sistent demand for a converted church membership in Northampton finallyforced his own removal to the frontier at Stockbridge, Massachusetts, in 1750.14

There he produced the great philosophical treatise, A Careful and Strict Enquiryinto the Modern Prevailing Notions of that Freedom of Will, Which is supposed tobe essential to Moral Agency, Virtue and Vice, Reward and Punishment, Praiseand Blame (1754)15, where he argued that man’s will is free, even if divinelydetermined, because it is rooted in the unfettered exercise of one’s own strongestmotive, and the theological work, The Great Christian Doctrine of Original SinDefended (1758), where he asserted that because human nature is entirely cor-

12 See Jonathan Edwards,AFaithful Narrative of the SurprizingWork of God in the Conversion ofMany Hundred Souls in Northampton, and the Neighbouring Towns and Villages of NewHampshire in New-England (London: John Oswald, 1737), in C. C. Goen, ed., The GreatAwakening, TheWorks of Jonathan Edwards, vol. 4 (NewHaven: Yale University Press, 1972),pp. 130–211. See also Thomas S. Kidd, The Great Awakening: The Roots of EvangelicalChristianity in Colonial America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007); George M.Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), pp. 150–169;Mark A. Noll, The Rise of Evangelicalism: The Age of Edwards, Whitefield and the Wesleys(DownersGrove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2003), pp. 100–154;Michael J.McClymond andGeraldR. McDermott, The Theology of Jonathan Edwards (New York: Oxford University Press,2012), pp. 428–437; Robert W. Caldwell III, Theologies of the American Revivalists: FromWhitefield to Finney (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2017), ch. 1.

13 See Mark A. Noll, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (New York:Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 22–25.

14 See Marsden, Jonathan Edwards, pp. 345–356.15 See Allen C. Guelzo, Edwards On the Will: A Century of American Theological Debate

(Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1989); Guelzo, ‘After Edwards: Orig-inal Sin and Freedom of the Will,’ in Oliver D. Crisp and Douglas A. Sweeney, eds, AfterJonathan Edwards: The Courses of the New England Theology (New York: Oxford UniversityPress, 2012), pp. 51–62; Guelzo, ‘The Return of the Will: Jonathan Edwards and the Possi-bilities of Free Will’, in Sang Hyun Lee and Allen C. Guelzo, eds, Edwards in Our Time:Jonathan Edwards and the Shaping of American Religion (Grand Rapids, Michigan: WilliamB. Eerdmans, 1999), pp. 87–110; Philip John Fisk, Jonathan Edwards’s Turn from the Classic-Reformed Tradition of Freedom of the Will (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 2016),ch. 8.

Chapter One18

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

rupted by sin, those free exercises without divine regeneration are always sinful.16

The latter work was published after Edwards’s death in 1758, following a verybrief relocation as president of the College of New Jersey, later Princeton.

Thus, an evangelical theology that might broadly be described as Edwardseanwas necessarily revivalistic and practical, in that it required the genuine con-version of the freely-choosing sinner, and Calvinistic, in that it affirmed thetraditional tenets of the Reformed faith such as divine sovereignty and humandepravity. These fundamental attributes would remain identifiable character-istics of most of Edwardseanism in the nineteenth century throughout EdwardsPark’s lifetime, even if in some variants the allegiance became largely ephemeral.Practically speaking, the theological parties within Congregationalism that de-veloped in New England in the decades after Edwards’s death may be definedlargely as they accepted or rejected aspects of Edwards’s legacy. The ‘Old Cal-vinists’ wished to retain the social order of the traditional covenantal polity inNew England, and, while they embraced orthodox doctrine and some weresympathetic to spiritual renewal, they generally rejected the enthusiasm andupheaval associated with the evangelical revival. This moderate party possessedmany pious and distinguished men—including Jedidiah Morse (1761–1826),David Tappan (1752–1803) and Ezra Stiles (1727–1795)—but largely failed toproduce a growing number of adherents as the long eighteenth century closed.17

The more liberal party in eastern Massachusetts, known to Edwardseans as‘Arminians,’ for want of a better term, shared a desire for social stability with theOld Calvinists but increasingly rejected orthodox doctrine in favour of a ra-tionalistic theology that adopted a more positive view of human ability and intheir viewapplied a fresh standard of reasonableness to God’s dealings withman.The absurd idea that God had, for example, imputed the sin of Adam to all hisprogeny to establish their native depravity failed this test—no individual oughtto be held personally responsible for the sins of an ancient and unelected rep-

16 See Paul Ramsey, ed., Freedom of the Will, The Works of Jonathan Edwards, vol. 1 (NewHaven: Yale University Press, 1957), pp. 225–238; Clyde A. Holbrook, ed., Original Sin, TheWorks of Jonathan Edwards, vol. 3 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970), pp. 107–119.

17 See Sydney Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (New Haven: Yale Uni-versity Press, 1972), pp. 403–404; E. BrooksHolifield,Theology in America: Christian Thoughtfrom the Age of the Puritans to the Civil War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004),pp. 149–156; Joseph W. Phillips, Jedidiah Morse and New England Congregationalism (NewBrunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1983), pp. 1–11; Edmund S. Morgan, TheGentle Puritan: A Life of Ezra Stiles, 1727–1795 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962),pp. 166–179. JedidiahMorsewould play an important role in negotiating the compromise thatled to the founding of Andover seminary. David Tappanwas theHollis professor of divinity atHarvard prior to the Unitarian Henry Ware, whose succession prompted the Andovercompromise thatMorse was to shepherd; see Phillips, JedidiahMorse, pp. 138–139. Ezra Stileswas a minister in Newport, Rhode Island, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire, until he becamepresident of Yale College in 1778, serving in that office until his death in New Haven in 1795.

Introduction 19

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

resentative. Some of this group, like Charles Chauncey (1705–1787) and JonathanMayhew (1720–1766), eventually followed the guidance of uncorrupted reasontowards Unitarianism and a number to outright universalism by the early dec-ades of the nineteenth century.18

A third group deliberately championed Edwards’s revivalistic Calvinism.Closely tied to Edwards personally by familial and ministerial relationships, the‘New Divinity’—not initially a term of approbation by anyone—clerics wereoften, like him, Congregationalist products of Yale College and the rural Con-necticut River valley.19 If Edwards himself had reinvigorated traditional Cal-vinism with the philosophical developments of the eighteenth century in view,Edwards’s disciples were likewise engaged in adapting his legacy in the new socialand intellectual setting of post-Revolutionary America. As small-town ministersrighteously indignant over the dangerous acceleration of self-interest in anemerging market economy, they extended Edwards’s teachings on the activenature of virtue into all-encompassing definitions of holiness as radical disin-terested benevolence and of sin as self-love or selfishness.20This Godly charter forbenevolence was first personal, guiding one’s own selfless moral choices, butthen corporate, as it unleashed with unprecedented energy an entire industry ofactivist enterprises formed to abolish slavery, establish home and overseasmissions, promote temperance, found educational institutions, and undertakehumanitarian reform.21 Edward Park’s own Andover seminary would be a keyfeature of this efflorescence. At the same time, concerned as was Edwards himselfabout the antinomian excesses that had attended the first revivals, the NewDivinity clerics promulgated a high view of God’s law in detailing his orderlymoral government, and they preached untiringly on the moral accountability ofthe human agent resident in every act of choice or ‘exercise’.22 They were con-

18 See Holifield, Theology in America, pp. 128–135.19 See Mark Valeri, ‘Jonathan Edwards, the New Divinity, and Cosmopolitan Calvinism,’ in

Oliver D. Crisp andDouglas A. Sweeney, eds,After Jonathan Edwards: The Courses of the NewEngland Theology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 17–30; McClymond andMcDermott, Theology of Jonathan Edwards, ch. 37; Guelzo, Edwards on the Will, ch. 3; Ho-lifield, Theology in America, pp. 135–149.

20 See Jonathan Edwards, ‘Dissertation on the Nature of True Virtue’, in Paul Ramsey, ed.,Ethical Writings, The Works of Jonathan Edwards, vol. 8 (New Haven: Yale University Press,1989), pp. 537–627.

21 See the discussion in Ahlstrom, Religious History, pp. 422–428.22 The central importance of moral accountability in Edwardsean Calvinism has been forcefully

argued by William Breitenbach; see Breitenbach, ‘New Divinity Theology and the Idea ofMoral Accountability’ (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Yale University, 1978); see also Breitenbach,‘Samuel Hopkins and the New Divinity: Theology, Ethics, and Reform in Eighteenth-CenturyNew England’, William and Mary Quarterly 34 (1977), pp. 572–589, and Breitenbach, ‘TheConsistent Calvinism of the NewDivinityMovement’,William andMary Quarterly 41 (1984),pp. 241–264.

Chapter One20

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

vinced that Edwards’s revivalistic call for a converted church required a rejectionof the old Puritan practice of preparation (much favoured still by the Old Cal-vinists), where by the gradual application of the ‘means of grace’—throughprayer, the preaching of the Word, and the sacraments—a sinner might wait onGod for years until the Spirit enlightened the understanding andmoved the heartto full conviction. Edwards’s successors insisted on gospel preaching that un-qualifiedly rejected a dependence on means in favour of the sinner’s immediateresponsibility to repent upon hearing the gospel.

To validate these startling revivalist imperatives as thoroughly Edwardsean,the New Divinity men depended on a distinction made by Jonathan Edwards inFreedom of the Will.23 Edwards had distinguished between a natural inability(arising from a lack of physical strength or an insuperable natural barrier) and amoral inability (consisting of a want of an inclination or disposition).24 Theindividual moral agent was not responsible for failure in the first case, butcompletely culpable in the second. Deftly, the New Divinity clerics claimed fromthis operative difference that every sinner had a natural ability to repent, sincenothing prevented anyone hearing the gospel from repenting apart from theirown stubborn unwillingness—there were no metaphysical shackles to complainof. As Calvinists, the New Divinity party did not overlook the fact that moralinability proceeded from innate depravity—a gracious interposition by the HolySpirit was still required—but, as Edwardsean revivalists, they were certain that amoral indisposition could never provide an adequate excuse for a fallen sinnerfailing to elect righteousness. Importantly, it followed that a universal naturalability warranted the unreserved proclamation of the gospel to every sinner—thiswas the glory of evangelical Calvinism.25

The first leaders of the New Divinity party were personally tied to JonathanEdwards. Joseph Bellamy (1719–1790) and Samuel Hopkins (1721–1803) were theRomulus and Remus of a forthcoming benevolent empire, each nurtured fromthe common fount of theology in Edwards’s own home. Bellamy’s principal work,True Religion Delineated (1750), contained a preface by Edwards himself,praising the volume’s support for experimental piety. Bellamy’s theology ex-

23 See David W. Kling, A Field of Divine Wonders: The New Divinity and Village Revivals inNorthwestern Connecticut 1792–1822 (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania StateUniversity Press, 1993), pp. 88–91.

24 Edwards, Freedom of the Will, pp. 156–162. See also Caldwell III, Theologies of the AmericanRevivalists, pp. 58–68; Philip John Fisk, Jonathan Edwards’s Turn from the Classic-ReformedTradition of Freedom of the Will, pp. 344–346.

25 See William Breitenbach, ‘Piety andMoralism: Edwards and the New Divinity’, in Nathan O.Hatch and Harry S. Stout, eds, Jonathan Edwards and the American Experience (New York:Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 186–188, 190–195; see also Noll, America’s God, pp. 272–273.

Introduction 21

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

tended Edwards’s ownwork on the permissiveness bywhichGod allowed sin, andexpanded likely hints from Edwards into a description of God as a Moral Gov-ernor—each developed as working adjustments to inherited Calvinism.26 Hop-kins was the great systematiser whose codification of the New Divinity theologyin his two-volume System of Doctrines (1793) nearly made ‘Hopkinsianism’synonymous with the entire movement.27 He studied for eight months withEdwards in Northampton and, later, when Edwards removed to Stockbridge, heserved as minister in Great Barrington and so became Edwards’s nearest clericalneighbour. Hopkins went beyond Bellamy’s work on the permissive nature of sinto assert that sin was in fact the occasion of greater good in the universe—thisbecame a party slogan. His utter rejection of the use of the means of grace by theunconverted became a startling proposal that a sinner’s application of the meansonly increased one’s guilt, since all the actions of the unrighteous before salvationcould only be completely sinful and selfish.28 The distinguishing mark of theconverted believer was in fact the very opposite of selfishness, a ‘disinterestedbenevolence’ that made emblematic Edwards’s life of true virtue as an absolutelyselfless dedication to good works. In a true saint this radical self-abandonmentmight literally mean a ‘willingness to be damned’ if it furthered God’s glory—New Divinity opponents made hay for decades on this Hopkinsian exclamationpoint. Hopkins’s apologetic aim was to balance the sovereignty of God withhuman accountability, insisting on ‘regeneration’ as the work of the Holy Spiritand a complementary ‘conversion’ as an exercise of the human will. In thismanner Calvinistic divine sovereignty and human depravity, rather than actingas solvents to action, underpinned the moral urgency of Edwardseanrevivalism.29 Such a balancing act remained a critical feature of the theology oflater Hopkinsians like Edwards Park.

26 SeeMarkValeri, Lawand Providence in Joseph Bellamy’s NewEngland: TheOrigins of the NewDivinity in Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), pp. 110–133;see also Oliver D. Crisp, Jonathan Edwards among the Theologians (Grand Rapids, Michigan:William B. Eerdmans, 2015), pp. 124–142.

27 Samuel Hopkins, The System of Doctrines, contained in Divine Revelation, explained anddefended, Showing their Consistence and Connection with each other, by Samuel Hopkins,D.D., Pastor of the First Congregational Church in Newport, in Two Volumes (Boston: I.Thomas and E. Andrews, 1793).

28 Bellamy had argued earlier that ‘all unregenerate personsmakeMUCHof their duties, thoughsuch miserable poor things: and so affront God to his very face….their best religious per-formances are odious in the sight of God’; see Joseph Bellamy, True Religion Delineated; or,Experimental Religion Distinguished from Formality on the OneHand and Enthusiasm on theOther, in two discourses, by Joseph Bellamy, D.D., Minister of the Gospel at Bethlehem inConnecticut (Glasgow: Lochhead, 1828), p. 163.

29 See Joseph Conforti, Samuel Hopkins and the New Divinity Movement: Calvinism, the Con-gregational Ministry, and Reform in New England Between the Great Awakenings (GrandRapids, Michigan: Christian University Press, 1981), pp. 29–32, 65–67, 69–70, 117–123; see

Chapter One22

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

Edwards’s son, Jonathan Edwards, Jr, (1745–1801) studied with both Bellamyand Hopkins and made important contributions to the New Divinity party as apolemicist defending both his father and his father’s successors’ ‘improvements’on the family legacy.30 He gave the fullest expression to date of the moral gov-ernment theory of the atonement, building on the work of Bellamy31 and StephenWest (1735–1819). Importantly, this theory replaced for the New Divinity thetraditional Reformed view that Christ’s death was a substitution for the sinner’sown deserved penalty or that God imputed Adam’s sin to his posterity—eachseemed hard to defend against the universal principle of equity. They preferred toaccentuate the work of God as a benevolent Moral Governor who displayed hiscare for the universe by demonstrating that his moral law operated in favour ofpublic justice: Christ’s death effected no individual sinner’s pardon but publiclyillustrated that God’s law must be revered.32 In continuing to extend, with Ed-wards, Jr, the spirit of innovation from the first generation of Bellamy andHopkins, Nathanael Emmons (1745–1840) was perhaps the most original of theNew England divines.33 Conducting his ministry for fifty-four years in ruralFranklin, Massachusetts—where young Edwards Park would regularly travelwith his family from nearby Providence, Rhode Island, to hear him preach—Emmons’s views were confessedly rooted in the Hopkinsian system, but weredeveloped toward their logical extremity and came to represent the most con-troversial summation of what came to be called the ‘Exercise’ scheme. Hopkinshad emphasised that moral conduct resided in the actions or ‘exercises’ of the

also Noll, America’s God, pp. 269–276; Peter Jauhiainen, ‘Samuel Hopkins and Hopkin-sianism,’ in Oliver D. Crisp and Douglas A. Sweeney, eds, After Jonathan Edwards: TheCourses of theNewEngland Theology (NewYork: OxfordUniversity Press, 2012), pp. 108–117,and Jauhiainen, ‘An Enlightenment Calvinist: Samuel Hopkins and the Pursuit of Benev-olence’ (unpublished Ph.D. diss. , University of Iowa, 1997; publication by Oxford UniversityPress forthcoming); Caldwell III, Theologies of the American Revivalists, ch. 3.

30 See Robert L. Ferm, A Colonial Pastor: Jonathan Edwards the Younger, 1745–1801 (GrandRapids, Michigan:William B. Eerdmans, 1976), pp. 21–24; Jonathan Edwards, Jr, ‘Remarks onthe Improvements Made in Theology by his Father, President Edwards,’ The Works of Jon-athan Edwards, D.D. (Andover: Allen, Morrill and Wardwell, 1842), vol. I, pp. 481–492.

31 See Oliver D. Crisp, ‘The Moral Government of God: Jonathan Edwards and Joseph Bellamyon the Atonement,’ in Oliver D. Crisp and Douglas A. Sweeney, eds, After Jonathan Edwards:The Courses of the New England Theology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 78–90; McClymond and McDermott, Theology of Jonathan Edwards, pp. 614–617.

32 See Ferm, A Colonial Pastor: Jonathan Edwards the Younger, pp. 22, 115–119.33 See Gerald R. McDermott, ‘Nathanael Emmons and the Decline of Edwardsean Theology,’ in

Oliver D. Crisp andDouglas A. Sweeney, eds,After Jonathan Edwards: The Courses of the NewEngland Theology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 118–129; Guelzo, Edwardson the Will, pp. 102–103, 109–110; McClymond and McDermott, Theology of Jonathan Ed-wards, pp. 607–612, 622–623, 632–634; Holifield, Theology in America, pp. 144–147; ZacharyM. Bowden, ‘The Speckled Bird: Nathanael Emmons, Consistent Calvinism, and the Legacy ofJonathan Edwards’ (unpublished Ph.D. diss. , Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary,2016).

Introduction 23

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

human agent and not in any prior disposition: there could be no actual sin priorto actual sinful exercises, or else the moral culpability of the sinner would vanishin the mists of prevailing depravity: no one ought to be punished for a God-ordained disability. Any Hopkinsian ‘exerciser’ saw that even the hint of a sinfuldisposition simply provided an excuse for sinners to hide behind—besides, howcould there be sin before there was a single sinful act? Emmons’s notoriousepigramwas not at all enigmatic: ‘all sin consists in sinning’.34 In its simplicity thiswas clearly just the obverse of true virtue, which required expression in the activebenevolence of the converted moral agent. Emmonsism insisted with Hopkin-sianism that holiness and sin consisted only in the willing choices or free ex-ercises of the moral agent, but it preserved for the Deity an absolutist Calvinistsovereignty in its own strong statements establishingGod’s sole causality in everyevent. This particularly direct divine efficiency appeared to require that Godhimself author sin, but Emmons, far from being abashed by this conclusion, onlyaffirmed that such a position proceeded logically from scripture. The Exercisesword cut in both directions, establishing an ultra-Calvinist view of God’s sov-ereignty alongside an absolute freedom for the moral agent. If this was a dis-concerting double efficiency to many, ‘Emmonsism’ as an extension of theHopkinsian exercise scheme only followed Edwards on the will in seeking whatwas required of post-Revolutionary Calvinism, i. e. , to establish the moral ac-countability of man without diminishing the supremacy of the authority ofGod.35 Notably, the key characteristic of exercise—that moral accountabilityrequired that there was neither a passive condition of depravity nor any moralstate or ‘taste’ that preceded one’s first active choice—continued as a standardtenet of Park’s New England Theology.36

It would be misleading to suggest that the New Divinity clerics agreed uni-formly on every point of doctrine: they insisted stubbornly on their own in-dependence. Yet the degree of agreement was sufficiently substantial that itmadesense then and now to identify the NewDivinity party as a coherent group, and totrace their specific theological influence outside New England and Con-gregationalism into Presbyterian churches in theMiddle Atlantic states—even asfar away as Virginia, Tennessee and Great Britain.37 They were unrepentantCalvinists, in that they held to native depravity and God’s sovereignty, and active

34 Emmons in Jacob Ide, ed., The Works of Nathanael Emmons, Including a ‘Memoir of Na-thanael Emmons, with Sketches of His Friends and Pupils’ by Edwards A. Park, 6 vols (Boston:Congregational Board of Publication, 1860–1863; reprint, New York: Garland Publishers,1987), vol. I, p. 365.

35 See Noll, America’s God, pp. 264, 282–283; Ahlstrom, Religious History, pp. 410–412.36 ‘Exercise’was more than ‘action’, since action could appear to be just the physical expression

of a native disposition.37 See Holifield, Theology in America, p. 135.

Chapter One24

Charles W. Phillips: Edwards Amasa Park. The Last Edwardsean

© 2018, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, GöttingenISBN Print: 9783525560303 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647560304

revivalists, in that their preaching focused on an urgent call to immediate re-pentance. Moreover, they were avowedly Edwardseans in at least a dual sense.First, Jonathan Edwards was always the protean figure fromwhom their theologyderived its authority. Although the New Divinity men in general (with the pos-sible exception of Emmons) did not share Edwards’s philosophical ideality, andas a group adopted signal modifications of Edwards’s own recalibration of tra-ditional Reformed Calvinism, they never hesitated to yield pride of place toJonathan Edwards as the fons et origo of their movement. Secondly, their labourswere ultimately validated by that most Edwardsean of evidences—by the SecondGreat Awakening in New England at the close of the eighteenth century and theopening of the nineteenth, when, in Sydney Ahlstrom’s words, ‘the new revivalsoccurred, almost uniformly under the strictest preaching of the New Divinity’.38

If Edwards own theological identity was founded in the first awakening in NewEngland, the New Divinity party’s identification with Edwards would be vindi-cated by the second.

Nevertheless, two significant elements within evangelical orthodoxy in earlynineteenth-century New England would dispute that New Divinity theology ingeneral or a dominant Hopkinsian exercise scheme in particular could properlybe identified as Edwardsean. One group, whose institutional locus became theTheological Institute of Connecticut in East Windsor and who included AsaBurton (1752–1836) and Bennet Tyler (1783–1858), asserted that the exercisershad departed from Edwards’s own views in neglecting the import of a traditionalCalvinist understanding of innate depravity—indeed such a doctrine was centralto Reformed Calvinism itself. Some in this moderate Edwardsean party wereidentified (by foes and friends) as ‘tasters’ because they held that a sinful natureexisted prior to any moral action, so that a prior sinful disposition or inclinationlay behind any voluntary exercise and solely determined the will’s choice.39It istrue that the tasters and the exercisers shared much common ground as jointshareholders in a general Edwardsean enculturation: Burton’s own theologicaltraining, for example, was Hopkinsian. They generally agreed that regenerationwas a transformation of sinners initiated by God’s grace from outside themselves,and that the demand for a renewed membership in the church did not allow forthe gradualism of the preparationist means of grace: revival was the object of

38 See Ahlstrom, Religious History, pp. 415–428; the quotation is from p. 416.39 See Douglas A. Sweeney, ‘Taylorites and Tylerites,’ in Oliver D. Crisp andDouglas A. Sweeney,

eds, After Jonathan Edwards: The Courses of the New England Theology (New York: OxfordUniversity Press, 2012), pp. 142–150; see also Sweeney, Nathaniel Taylor, New Haven The-ology, and the Legacy of Jonathan Edwards (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003),pp. 132–138, 148.

Introduction 25