Edinburgh Research ExplorerPatient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4 1 Shortening Self-report...

Transcript of Edinburgh Research ExplorerPatient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4 1 Shortening Self-report...

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Shortening self-report mental health symptom measures throughoptimal test assembly methods: Development and validation ofthe Patient Health Questionnaire-Depression-4Citation for published version:Ishihara, M, Harel, D, Levis, B, Levis, AW, Riehm, KE, Saadat, N, Azar, M, Rice, DB, Sanchez, TA,Chiovitti, MJ, Cuijpers, P, Gilbody, S, Ioannidis, JPA, Kloda, LA, Mcmillan, D, Patten, SB, Shrier, I, Arroll, B,Bombardier, CH, Butterworth, P, Carter, G, Clover, K, Conwell, Y, Goodyear-smith, F, Greeno, CG,Hambridge, J, Harrison, PA, Hudson, M, Jetté, N, Kiely, KM, Mcguire, A, Pence, BW, Rooney, AG,Sidebottom, A, Simning, A, Turner, A, White, J, Whooley, MA, Winkley, K, Benedetti, A & Thombs, BD2018, 'Shortening self-report mental health symptom measures through optimal test assembly methods:Development and validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-Depression-4', Depression and anxiety.https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22841

Digital Object Identifier (DOI):10.1002/da.22841

Link:Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer

Document Version:Peer reviewed version

Published In:Depression and anxiety

Publisher Rights Statement:This is the author's peer-reviewed manuscript as accepted for publication.

General rightsCopyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s)and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise andabide by the legal requirements associated with these rights.

Take down policyThe University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorercontent complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright pleasecontact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately andinvestigate your claim.

Download date: 17. Mar. 2020

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

1

Shortening Self-report Mental Health Symptom Measures through Optimal Test Assembly

Methods: Development and Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-Depression-4

Miyabi Ishihara, MSc1,2,3, Daphna Harel, PhD2,3, Brooke Levis, MSc4,5, Alexander W. Levis,

MSc4,5, Kira E. Riehm, MSc4, Nazanin Saadat, BSc4, Marleine Azar, MSc4,5, Danielle B. Rice,

MSc4,6, Tatiana A. Sanchez, BSc4, Matthew J. Chiovitti, MISt4, Pim Cuijpers, PhD7, Simon

Gilbody, PhD8, John P.A. Ioannidis, MD, DSc9, Lorie A. Kloda, PhD10, Dean McMillan, PhD8,

Scott B. Patten, MD, PhD11,12, Ian Shrier, MD, PhD4,5, Bruce Arroll, MBChB, PhD13, Charles H.

Bombardier, PhD14, Peter Butterworth, PhD15,16,17, Gregory Carter, FRANZCP18, Kerrie Clover,

PhD, MPsychClin, MAPS18,19, Yeates Conwell, MD20, Felicity Goodyear-Smith, MBChB, MD13,

Catherine G. Greeno, PhD21, John Hambridge, BA (Hons), Dip Clin Psych22, Patricia A.

Harrison, PhD23, Marie Hudson, MD, MPH4,24, Nathalie Jetté, MD, MSc11,12,25, Kim M. Kiely,

PhD15, Anthony McGuire, PhD, NP26, Brian W. Pence, PhD27, Alasdair G. Rooney, MBChB,

MD28, Abbey Sidebottom, PhD, MPH29, Adam Simning, MD, PhD21, Alyna Turner, PhD30,31,

Jennifer White, PhD32, Mary A. Whooley, MD33,34,35, Kirsty Winkley, PhD25, Andrea Benedetti,

PhD5,24,36, Brett D. Thombs, PhD4,5,6,24,37,38.

1 Department of Statistics, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California, USA; 2

PRIISM Applied Statistics Center, New York University, New York, New York, USA; 3

Department of Applied Statistics, Social Science, and Humanities, New York University, New

York, New York, USA; 4Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, Jewish General Hospital,

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

2

Montréal, Québec, Canada; 5Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational

Health, McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 6 Department of Psychology, McGill

University, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 7 Department of Clinical, Neuro and Developmental

Psychology, EMGO Institute, VU University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 8 Hull York Medical

School and the Department of Health Sciences, University of York, Heslington, York, United

Kingdom; 9 Department of Medicine, Department of Health Research and Policy, Department of

Biomedical Data Science, Department of Statistics, Stanford University, Stanford, California,

USA; 10 Library, Concordia University, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 11 Department of Community

Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada; 12 Hotchkiss Brain Institute

and O'Brien Institute for Public Health, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada; 13

Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care, University of Auckland, New Zealand;

14 Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA;

15 Centre for Research on Ageing, Health and Wellbeing, Research School of Population Health,

The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia; 16 Centre for Mental Health, Melbourne

School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia;

17Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne,

Melbourne, Australia; 18 Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health, University of

Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia; 19 Psycho-Oncology Service, Calvary Mater Newcastle,

New South Wales, Australia; 20 Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester Medical

Center, New York; 21 School of Social Work, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,

USA; 22Liaison Psychiatry Department, John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle, Australia; 23 City of

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

3

Minneapolis Health Department, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA; 24 Department of Medicine,

McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 25 Department of Clinical Neurosciences,

University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada; 26 Department of Nursing, St. Joseph's College,

Standish, Maine, USA; 27 Department of Epidemiology, Gillings School of Global Public Health,

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA; 28 Division

of Psychiatry, Royal Edinburgh Hospital, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK;

29Allina Health, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA; 30 School of Medicine and Public Health,

University of Newcastle, New South Wales, Newcastle, Australia; 31 IMPACT Strategic Research

Centre, School of Medicine, Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria, Australia; 32 Monash

University, Melbourne, Australia; 33 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of

California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA; 34 Department of Medicine, Veterans

Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco, California, USA; 35 Department of Medicine, University

of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA; 36 Respiratory Epidemiology and

Clinical Research Unit, McGill University Health Centre, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 37

Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 38 Department of

Educational and Counselling Psychology, McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Drs. Jetté and Patten declare that they received a grant, outside

the submitted work, from the Hotchkiss Brain Institute, which was jointly funded by the Institute

and Pfizer. Pfizer was the original sponsor of the development of the PHQ-9, which is now in the

public domain. All other authors declare no competing interests. No funder had any role in the

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

4

design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data;

preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for

publication.

Acknowledgements: This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research

(CIHR; KRS-134297). Dr. Harel was supported by NYU start-up research grants. Ms. Levis was

supported by a CIHR Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship doctoral

award. Mr. Levis and Ms. Azar were supported by Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé

(FRQS) Masters Training Awards. Ms. Riehm and Ms. Saadat were supported by CIHR

Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canadian Graduate Scholarships – Master’s Awards. Ms.

Rice was supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. The primary studies by

Amoozegar and by Fiest et al. were funded by the Alberta Health Services, the University of

Calgary Faculty of Medicine, and the Hotchkiss Brain Institute. Collection of data for the study

by Arroll et al. was supported by a project grant from the Health Research Council of New

Zealand. Data for the study by Razykov et al. was collected by the Canadian Scleroderma

Research Group, which was funded by the CIHR (FRN 83518), the Scleroderma Society of

Canada, the Scleroderma Society of Ontario, the Scleroderma Society of Saskatchewan,

Sclérodermie Québec, the Cure Scleroderma Foundation, Inova Diagnostics Inc., Euroimmun,

FRQS, the Canadian Arthritis Network, and the Lady Davis Institute of Medical Research of the

Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, QC. The primary study by Bombardier et al. was supported

by the Department of Education, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research,

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

5

Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems: University of Washington (grant no. H133N060033), Baylor

College of Medicine (grant no. H133N060003), and University of Michigan (grant no.

H133N060032). Collection of data for the primary study by Kiely et al. was supported by

National Health and Medical Research Council (grant number 1002160) and Safe Work

Australia. Dr. Butterworth was supported by Australian Research Council Future Fellowship

FT130101444. Dr. Conwell received support from NIMH (R24MH071604) and the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (R49 CE002093). Collection of data for the primary study by

Gjerdingen et al. was supported by grants from the NIMH (R34 MH072925, K02 MH65919, P30

DK50456). The primary study by Eack et al. was funded by the NIMH (R24 MH56858).

Collection of data for the studies by Turner et al were funded by a bequest from Jennie Thomas

through the Hunter Medical Research Institute. The primary study by Sidebottom et al. was

funded by a grant from the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Health

Resources and Services Administration (grant number R40MC07840). Dr. Hudson was

supported by a FRQS Senior Investigator Award. The primary study by Twist et al. was funded

by the UK National Institute for Health Research under its Programme Grants for Applied

Research Programme (grant reference number RP-PG-0606-1142). Dr. Jetté was supported by a

Canada Research Chair in Neurological Health Services Research. Dr. Kiely was supported by

funding from Australian National Health and Medical Research Council fellowship (grant

number 1088313). Collection of data for the primary study by Williams et al. was supported by a

NIMH grant to Dr. Marsh (RO1-MH069666). Collection of primary data for the study by Dr.

Pence was provided by NIMH (R34MH084673). The primary study by Rooney et al. was funded

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

6

by the United Kingdom National Health Service Lothian Neuro-Oncology Endowment Fund.

Simning et al.’s research was supported in part by grants from the NIH (T32 GM07356), Agency

for Healthcare Research and Quality (R36 HS018246), NIMH (R24 MH071604), and the

National Center for Research Resources (TL1 RR024135). The primary study by Thombs et al.

was done with data from the Heart and Soul Study (PI Mary Whooley). The Heart and Soul

Study was funded by the Department of Veterans Epidemiology Merit Review Program, the

Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development service, the National

Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01 HL079235), the American Federation for Aging Research,

the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Ischemia Research and Education Foundation.

Drs. Benedetti and Thombs were supported by FRQS researcher salary awards. No other authors

reported funding for primary studies or for their work on the present study.

Author Contributions: MI, DH, BL, PC, SG, JPAI, LAK, DM, SBP, IS, RJS, RCZ, AB and

BDT were responsible for the study conception and design. BA, MB, CHB, PB, GC, KC, YC,

DKG, FGS, CGG, JH, PAH, MH, KI, NJ, KMK, LM, AM, BWP, AGR, ASidebottom, ASimning,

AT, JW, MAW, KW, AB, and BDT were responsible for collection of primary data included in

this study. BL, KER, NS, MA, DBR, TAS, MJC and BDT contributed to data extraction and

coding. MI, DH, BL, AWL, AB, and BDT contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. MI,

DH, BL, AWL, and BDT contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors provided a critical

review and approved the final manuscript. DH is the guarantor.

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

7

Keywords: Depression, Patient Health Questionnaire, Psychometrics, Patient outcome

assessment

Word Count: 3499

Address for Correspondence:

Daphna Harel, PhD; 246 Greene Street, 3rd floor, New York NY, 10003; Tel (212) 992-6701; E-

mail: [email protected]

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

8

ABSTRACT

Background: The objective of this study was to develop and validate a short form of

the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a self-report questionnaire for assessing

depressive symptomatology, using objective criteria.

Methods: Responses on the PHQ-9 were obtained from 7,850 English-speaking

participants enrolled in 20 primary diagnostic test accuracy studies. PHQ

unidimensionality was verified using confirmatory factor analysis, and an item response

theory model was fit. Optimal test assembly (OTA) methods identified a maximally

precise short form for each possible length between 1 and 8 items, including and

excluding the 9th item. The final short form was selected based on pre-specified validity,

reliability, and diagnostic accuracy criteria.

Results: A 4-item short form of the PHQ (PHQ-Dep-4) was selected. The PHQ-Dep-4

had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.805. Sensitivity and specificity of the PHQ-Dep-4 were

0.788 and 0.837, respectively, and were statistically equivalent to the PHQ-9 (sensitivity

= 0.761, specificity = 0.866). The correlation of total scores with the full PHQ-9 was high

(r = 0.919).

Conclusion: The PHQ-Dep-4 is a valid short form with minimal loss of information of

scores when compared to the full-length PHQ-9. Although OTA methods have been

used to shorten patient-reported outcome measures based on objective, pre-specified

criteria, further studies are required to validate this general procedure for broader use in

health research. Furthermore, due to unexamined heterogeneity, there is a need to

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

9

replicate the results of this study in different patient populations.

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

10

Introduction

In mental health research and clinical practice, self-report symptom measures are used to

assess patient symptoms and identify patients with undetected mental disorders. Completing

these measures is demanding, especially when people are asked to respond to multiple measures

that each contain multiple items (Coste et al., 1997; Goetz, Lemetayer, & Rat, 2013; Kruyen,

Emons, & Sijtsma, 2013; Stanton, Sinar, Balzer., & Smith, 2002). Therefore, researchers attempt

to create shortened versions with scores that perform comparably well with original full-length

versions (Coste et al., 1997; Goetz et al., 2013; Kruyen et al., 2013; Stanton, Sinar, Balzer, &

Smith, 2002). (Goetz et al., 2013)

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a 9-item, self-report questionnaire that

measures depressive symptomatology (Kroenke et al., 2009; Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002; Kroenke,

Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). A recent meta-analysis of the PHQ-9 found that at the standard cutoff

of 10, based on 34 studies, the sensitivity and specificity were 0.78 and 0.87, respectively

(Moriarty, Gilbody, McMillan, & Manea, 2015).

The PHQ-8 is similar to the PHQ-9 and is increasingly used because it eliminates one

item that asks about patients’ thoughts of either self-harm or being “better off dead” (Kroenke &

Spitzer, 2002), but it identifies large numbers of patients not at risk of suicide (Dube, Kroenke,

Bair, Theobald, & Williams, 2010; Razykov, Hudson, Baron, & Thombs, 2013). Many studies

have reported that the PHQ-8 performs nearly identically to the PHQ-9 (Corson, Gerrity, &

Dobscha, 2004; Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002; Leadbeater, Carruthers, Green, Rosser, & Field, 2011;

Razykov et al., 2013).

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

11

The PHQ-2 is another short-form, designed to include the two core items in a Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

diagnosis: depressed mood and anhedonia (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2003). A recent meta-

analysis of the PHQ-2 found that at a cutoff of 2, based on 17 studies, the sensitivity and

specificity were 0.91 and 0.70, respectively, while at a cutoff of 3, based on 19 studies, the

sensitivity and specificity were 0.76 and 0.87, respectively (Manea et al., 2016).

Conventionally, short forms of patient-report measures are created through an expert-

based analysis of item content, as with the PHQ-2, or by removing items with minimal factor

loadings (Goetz et al., 2013). These methods are not typically applied in a systematic way, and

multiple shortened versions of the same measure may exist (Coste et al., 1997; Goetz et al.,

2013; Kruyen et al., 2013; Smith, McCarthy, & Anderson, 2000; Stanton, Sinar, Balzer, & Smith,

2002). Methods such as item response theory (IRT; van der Linden & Hambleton, 1997) have

been used to evaluate and identify problematic items, but have not incorporated objective and

reproducible criteria for item selection.

Optimal test assembly (OTA) is a mixed-integer programming procedures that uses an

estimated IRT model to select the subset of items that best satisfies pre-specified constraints (van

der Linden, 2006). Although more commonly used in the development of high-stakes educational

tests (Holling, Kuhn, & Kiefer, 2013), a recent study demonstrated that OTA can be used to

develop shortened versions of patient-reported outcome measures (A. W. Levis et al., 2016). This

procedure was also shown to be replicable, reproducible, and produce shortened forms of

minimal length as compared with leading alternative methods (Harel & Baron, 2018).

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

12

The objective of the present study was to apply OTA to develop a shortened version of

the PHQ-9. We (1) used confirmatory factor analysis to verify the unidimensionality of the

underlying construct; (2) applied OTA methods to obtain candidate forms of each possible

length; and (3) selected the shortest possible form that showed similar performance to the full

form in terms of pre-specified validity, reliability, and diagnostic accuracy criteria, compared to

the PHQ-9 as the full-form standard.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study used a subset of data accrued for an individual participant data meta-analysis

(IPDMA) on the diagnostic accuracy of the PHQ-9 depression screening tool to detect major

depression (in progress). The IPDMA was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42014010673), and a

protocol was published (Thombs et al., 2014).

Search Strategy

A medical librarian searched Medline, Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed

Citations via Ovid, PsycINFO, and Web of Science (January 2000 - December 2014) on

February 7, 2015, using a peer-reviewed search strategy (Supplementary Methods 1). We also

reviewed reference lists of relevant reviews and queried contributing authors about non-

published studies. Search results were uploaded into RefWorks (RefWorks-COS, Bethesda, MD,

USA). After de-duplication, unique citations were uploaded into DistillerSR (Evidence Partners,

Ottawa, Canada), for storing and tracking search results.

Identification of Eligible Studies for Full IPDMA

Datasets from articles in any language were eligible for inclusion if they included

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

13

diagnostic classifications for current MDD or Major Depressive Episode (MDE) based on a

validated semi-structured or fully structured interview conducted within two weeks of PHQ-9

administration, among participants ≥18 years and not recruited from youth or psychiatric

settings. Datasets where not all participants were eligible were included if primary data allowed

selection of eligible participants. For defining major depression, we considered MDD or MDE

based on the DSM or MDE based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). If more

than one was reported, we prioritized DSM over ICD and DSM MDE over DSM MDD. Across

all studies, there were 23 discordant diagnoses depending on classification prioritization (0.1% of

participants).

Two investigators independently reviewed titles and abstracts for eligibility. If either

deemed a study potentially eligible, full-text review was completed by two investigators,

independently, with disagreements resolved by consensus, consulting a third investigator when

necessary. Translators were consulted to evaluate titles, abstracts and full-text articles.

Data Contribution and Synthesis

Authors of eligible datasets were invited to contribute de-identified primary data. We

compared published participant characteristics and diagnostic accuracy results with results from

raw datasets and resolved any discrepancies in consultation with the original investigators.

Data Selection for Present Study

We restricted our dataset to participants who completed the PHQ-9 in English, due to the

potential for heterogeneity across studies conducted in different languages. We excluded studies

that classified major depression using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI),

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

14

because it is structurally different from other fully structured interviews and classifies

approximately twice as many participants as cases compared to the most commonly used fully-

structured interview, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (B. Levis et al.,

Br. J. Psychiatry 2018).

Measure

Scores on each PHQ-9 item reflect frequency of symptoms in the last two weeks and

range from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”). Higher scores indicate greater depressive

symptomatology. Total scores range from 0 to 27 (Kroenke et al., 2001).

Statistical Analyses

Verification of Unidimensionality of the PHQ-9

Robust weighted least squares estimation in Mplus was used to fit a single-factor

confirmatory factor analysis model of PHQ-9 items (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). The model was

first fit without allowing for any residual correlations among the items. Then modification

indices were used to identify item pairs that would improve model fit if their residuals were

allowed to correlate, if there was theoretical justification (McDonald & Ho, 2002). Model fit was

evaluated concurrently, using: the 𝜒2statistic, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index

(TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Feinian Chen, Curran, Bollen,

Kirby, & Paxton, 2008). Priority was given to CFI, TLI, and RMSEA, because the 𝜒2test may

reject well-fitting models when sample size is large (Reise, Widaman, & Pugh, 1993). Model fit

was considered adequate if CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95 and RMSEA ≤ 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Item Response Theory Model and Optimal Test Assembly

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

15

A generalized partial credit model (GPCM) was fit to PHQ-9 (Muraki, 1992). The GPCM

is an IRT model that relates a latent trait, representing severity of depressive symptomatology, to

the distribution of observed item-level responses. The GPCM estimates two types of item-

specific parameters: a discrimination parameter and threshold parameters. From these item-level

parameter estimates, item information functions for each item were calculated from the GPCM,

as well as a test information function (TIF), obtained by summing item information functions.

Because the TIF is inversely related to the standard error of measurement of the latent trait, high

amounts of information represent greater precision for measuring depressive symptomatology.

Next, we used OTA, a mixed-integer programming technique to systematically search for

the short form that maximized the TIF, subject to the constraint of fixing the number of items

included in each short form, optimizing the precision of the short form in estimating participants’

level of depressive symptomatology (Boekkooi-Timminga, 1989; van der Linden, 2006). The

shape of the TIF was anchored at five points (van der Linden, 2006). Thus, for each short form of

lengths 1 to 8 items, OTA selected items from the full set of the nine PHQ-9 items that

maximized test information. Due to concerns about the use of the ninth item of the PHQ (Corson

et al., 2004; Dube et al., 2010; Lee, Schulberg, Raue, & Kroenke, 2007; Razykov et al., 2013;

Rief, Nanke, Klaiberg, & Braehler, 2004), the same procedure was used to generate 8 additional

short forms that were forced to exclude the ninth item. In total, the OTA procedure yielded 16

candidate short forms.

For each of the 16 candidate short forms and the full-length form, two scoring procedures

were used to obtain estimates of each participant’s level of depressive symptomatology. First, the

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

16

summed scores across all items included in the short form were calculated. Second, factor scores

were estimated for each participant. Although summed scores are typically relied upon for

clinical use, the factor scores were considered to provide a better estimate of the latent trait due

to well-known limitations of the summed score under the GPCM (Harel, 2014; van der Ark,

2005).

Selection of Final Short Form

The selection of the final short form was based on the following five criteria: reliability,

concurrent validity of summed scores, concurrent validity of factor scores, and non-inferior

sensitivity and specificity, since the elimination of items necessarily reduces information

compared to a full-length form.

Reliability of each candidate short form was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach,

1951). The final selected form was required a priori to have a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ≥

0.80. Concurrent validity of the summed scores and factor scores was measured with the

Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the full-length form and candidate short form scores,

and were required a priori to be ≥ 0.90.

Diagnostic accuracy of each candidate short form was assessed through a three-step

process. First, the sensitivity and specificity of each candidate short form for each of its possible

cutoff summed score values was estimated with a bivariate random-effects model. Second, for

each candidate short form, an optimal cutoff score was selected using Youden’s J statistic

(Youden, 1950). For the full-length form, the conventionally used cutoff score of 10 was selected

(Gilbody, Richards, Brealey, & Hewitt, 2007; Kroenke et al., 2001; Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002;

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

17

Spitzer et al., 2000; Wittkampf, Naeije, Schene, Huyser, & van Weert, 2007). Third, two non-

inferiority tests were conducted for each of the 16 candidate forms to compare sensitivity and

specificity, separately, to the full-length form. Non-inferiority tests assess whether the sensitivity

or specificity of the short form is not lower than that of the full-length form, up to a pre-specified

clinically-significant tolerance (Counsell & Cribbie, 2015), such as 𝛿 = 0.05. To conduct the

non-inferiority test, the sampling distribution of the test statistic was generated through the

bootstrap method (Liu, Ma, Wu, & Tai, 2006). Bootstrapping resamples the original dataset, with

replacement, to generate new, artificial, datasets (Efron & Tibshirani, 1994). For each non-

inferiority test, 2000 bootstrap iterations were conducted, controlling in each for the number of

respondents with and without major depression. For each bootstrap iteration, the bivariate

random-effects model was fit to each of the 16 candidate short forms and the full-length form,

and the sensitivities and specificities were computed based on their cutoff scores. To account for

the multiple testing in the 32 total non-inferiority tests, the Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value

was used to determine the significance of the test at the 0.05 signficance level (Benjamini &

Hochberg, 1995).

The factor analysis was conducted using Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). All other

analyses were conducted using R version 3.3.3 (R Core Team, 2017). The GPCM was fit using

the ltm package (Rizopoulos, 2006). The OTA analysis was conducted using the lpSolveAPI

package (Diao & van der Linden, 2011). The bivariate random-effects model was fit using the

lme4 package (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015).

RESULTS

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

18

Search Results and Inclusion of Primary Data

Of 5,248 unique titles and abstracts identified from the database search, 5,039 were

excluded after title and abstract review and 113 after full-text review, leaving 96 eligible articles

with data from 69 unique participant samples, of which 55 (80%) contributed datasets

(Supplementary Figure 1). Authors of included studies contributed data from three unpublished

studies, for a total of 58 datasets. Of these, we excluded 32 studies that administered the PHQ-9

in a language other than English and 6 more that used the MINI. In total, 7,850 participants (863

major depression cases) from 20 primary studies were included. These studies were conducted in

the USA, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, the UK, and Cameroon. The mean age of the sample

was 33.9 years, and 55.3% of participants were women. See Table 1 for descriptive sample

statistics, and Supplementary Table 1 for characteristics of each included study.

Unidimensionality of PHQ-9

A single factor model was fit to the PHQ-9 items with no specification of residual

correlations (𝜒2[𝑑𝑓 = 36] = 1578.7, 𝑝 < 0.0001, 𝑇𝐿𝐼 = 0.966, 𝐶𝐹𝐼 = 0.974,𝑅𝑀𝑆𝐸𝐴 =

0.086). Modification indices indicated improvement of model fit if residuals of items that

measure physical symptoms (items 3, 4, and 5) were correlated. The model was refitted with

specification of three correlated residuals, and fit improved (𝜒2[𝑑𝑓 = 39] = 750.2, 𝑝 <

0.0001, 𝑇𝐿𝐼 = 0.982, 𝐶𝐹𝐼 = 0.988,𝑅𝑀𝑆𝐸𝐴 = 0.062). Factor loadings for items were all

moderately high, with a median of 0.763 and a range of 0.665 to 0.877.

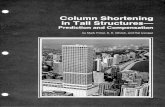

Item Response Theory Model and Optimal Test Assembly

Table 2 presents discrimination parameters for each item based on the GPCM. The item

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

19

with the greatest discrimination parameter was item 2. Other items with high values were items 1

and 6. Figure 1 shows the information function of each of the 9 items, as well as the total TIF.

Table 3 shows the items that were included in each of the 16 candidate short forms from

the OTA analysis. For the candidate forms generated both with the inclusion of item 9 and

without, items 3, 4, and 5 were only selected in the longest short forms, and quickly dropped

thereafter. Items 1, 2, and 6 were included in all forms of at least 4 items. For the short forms

generated from the full set of nine items, item 9 was included in all candidate short forms.

Selection of final short form

Table 4 presents Cronbach’s alpha values and concurrent validity correlations for the 16

candidate short forms. Table 5 presents results of the non-inferiority tests for both sensitivity and

specificity. There were four short forms that satisfied our pre-specified criteria in terms of

reliability, concurrent validity, and diagnostic accuracy. The four such forms were: 6-item and 7-

item short forms that included item 9 and 4-item and 5-item short forms that excluded item 9.

The 4-item short form was the shortest form that fulfilled all criteria. The form includes:

item 1 (“Little interest or pleasure in doing things”), item 2 (“Feeling down, depressed, or

hopeless”), item 6 (“Feeling bad about yourself – or that you are a failure or have let yourself or

your family down”), and item 8 (“Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have

noticed? Or the opposite – being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot

more than usual”). The PHQ-Dep-4 maintained high reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.805

(95% CI, 0.795, 0.814) compared to 0.866 for the full-length form. Correlations of the summed

and factor scores between the PHQ-Dep-4 and PHQ-9 were 0.919 (95% CI, 0.916, 0.923) and

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

20

0.910 (95% CI, 0.907, 0.914), respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of the PHQ-Dep-4 at

its optimal cutoff of 4 were 0.788 (95% CI, 0.725, 0.840) and 0.837 (95% CI, 0.809, 0.861),

respectively. Both sensitivity and specificity were non-inferior to the sensitivity (0.761; 95% CI,

0.679, 0.787) and specificity (0.866; 95% CI, 0.836, 0.892) of the full-length form.

DISCUSSION

This study illustrated how OTA methods can be used to effectively shorten self-report

symptom measures while maintaining comparable diagnostic accuracy. OTA methods were

applied to shorten the 9-item PHQ-9 to a 4-item version (PHQ-Dep-4). In addition to

maintaining similar sensitivity and specificity, the short form had minimal loss of information

and maintained reliability and validity that were comparable to the full-length form based on pre-

specified criteria. Cronbach’s alpha of the PHQ-Dep-4 was 0.805, compared to 0.866 for the full

form. Correlations of the summed score and factor score of the PHQ-Dep-4 and PHQ-9 were

0.919 and 0.910, respectively. Per pre-specified criteria, the sensitivity and specificity of the

PHQ-Dep-4 (0.788 and 0.837, respectively) were within 5% of those of the PHQ-9 (0.761 and

0.866, respectively).

The 4 items included in the PHQ-Dep-4 included items 1, 2, 6 and 8 from the original

PHQ-9. These items included the 2 core depression items (depressed mood and loss of interest)

that make up the commonly used PHQ-2. According to diagnostic criteria for major depression,

at least one of these symptoms must be present for a diagnosis. The other 2 items in the PHQ-

Dep-4 included an affective/cognitive item (feelings of failure) and a somatic item (physical

movement). Thus, the PHQ-Dep-4 includes items that qualitatively represent the depressive

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

21

symptomatology construct well. We note that the PHQ-Dep-4 includes 1 somatic symptom,

whereas the full PHQ-9 includes 4 symptoms. One study found that somatic symptoms may

increase scores on the PHQ-9 among somatically ill patients due to factors related to somatic

disease, but not depression, among scleroderma patients, but the association was minimal

(Leavens, Patten, Hudson, Baron, & Thombs, 2012). Another study, of multiple sclerosis

patients, did not find that somatic symptoms influenced scores substantively (Sjonnesen et al.,

2012).

Both the actual PHQ-2 and the PHQ-8 were selected in the set of 16 candidate short

forms. Neither of these, however, were selected by the OTA procedure as optimal. The PHQ-

Dep-4 has lower sensitivity than the PHQ-2 (0.788 rather than 0.880), but higher specificity

(0.837 rather than 0.725). The PHQ-Dep-4, therefore, may represent a middle ground between

shortening the full-length scale, while still retaining desirable measurement and diagnostic

properties. The PHQ-Dep-4 may be a useful option in some contexts because it is shorter than

the PHQ-9 and PHQ-8, but generates a wider score distribution than the PHQ-2.

There are several limitations for this study that must be considered. First, for the

collection of data for the full IPDMA, it was not possible to obtain primary data from 14 of the

69 eligible datasets. Second, the full IPDMA excluded studies where the PHQ-9 was

administered exclusively to patients with known psychiatric conditions. Therefore, the

generalizability of the results should be confirmed when monitoring treatment response. Third,

the present study only included participants for whom the PHQ-9 was administered in English.

Fourth, a previous study showed that semi-structured and fully structured interviews have

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

22

different characteristics as reference standards (B. Levis et al., Br. J. Psychiatry 2018). We

excluded studies that used the MINI, given its high rate of diagnosis relative to other diagnostic

interviews (B. Levis et al., Br. J. Psychiatry 2018). We included studies that used both semi-

structured and fully structured interviews as reference standards, and future work should verify

that our results apply in both cases. While our dataset included a specific sample of patients, we

note that measurement invariance or differential item functioning requirements have been

examined in previous studies of the PHQ-9 used as a continuous measure across variables like

language (Arthurs, Steele, Hudson, Baron, & Thombs, 2012; Merz, Malcarne, Roesch, Riley, &

Sadler, 2013), culture (Baas et al., 2011; Hirsch, Donner-Banzhoff, & Bachmann, 2013; Huang,

Chung, Kroenke, Delucchi, & Spitzer, 2006), and medical diagnosis (Chung et al., 2015; Cook et

al., 2011; Leavens et al., 2012). These studies provide some degree of confidence that the

structure of the PHQ-9 is similar across groups. Lastly, there is a need to replicate our results in

different patient populations due to unexamined heterogeneity across the studies included in this

analysis.

With regards to the OTA procedure, two limitations must be considered. First, the

selection of a short version was sensitive to the choice of criteria for the selection of the final

form, and should be carefully considered in future analyses Additionally, the OTA approach is

exploratory and data-driven, and the results of this study should be replicated.

CONCLUSION

The study illustrates how patient self-report symptom measures can be developed and

validated using the OTA method, which uses pre-specified objective criteria to determine the

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

23

length and specific items that should be included in a short form. The method was implemented

with a sample of 7,850 participants from 20 primary PHQ-9 diagnostic studies. The 4-item

version was developed and validated based on pre-specified constraints on its test information,

reliability, validity, and diagnostic accuracy.

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

24

REFERENCES

Arthurs, E., Steele, R. J., Hudson, M., Baron, M., & Thombs, B. D. (2012). Are Scores on

English and French Versions of the PHQ-9 Comparable? An Assessment of Differential

Item Functioning. PLoS ONE, 7(12), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052028

Baas, K. D., Cramer, A. O. J., Koeter, M. W. J., Van De Lisdonk, E. H., Van Weert, H. C., &

Schene, A. H. (2011). Measurement invariance with respect to ethnicity of the Patient

Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Journal of Affective Disorders, 129(1–3), 229–235.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.026

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-dffects models

using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Benjamini, Y., Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and

powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 57(1), 289–

300.

Boekkooi-timminga, E. (1989). A maximin model for test design. Psychometrika, 54(2), 237–

247.

Chung, H., Kim, J., Askew, R. L., Jones, S. M. W., Cook, K. F., & Amtmann, D. (2015).

Assessing measurement invariance of three depression scales between neurologic samples

and community samples. Quality of Life Research, 24(8), 1829–1834.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-0927-5

Cook, K. F., Bombardier, C. H., Bamer, A. M., Choi, S. W., Kroenke, K., & Fann, J. R. (2011).

Do somatic and cognitive symptoms of traumatic brain injury confound depression

screening? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(5), 818–823.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.008

Corson, K., Gerrity, M. S., & Dobscha, S. K. (2004). Screening for depression and suicidality in

a VA primary care setting: 2 items are better than 1 item. The American Journal of

Managed Care, 10(11 Pt 2), 839–845.

Coste, J., Guillemin, F., Pouchot, J., & Fermanian, J. (1997). Methodological approaches to

shortening composite measurement scales. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 50(3), 247–

252. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00363-0

Counsell, A., & Cribbie, R. A. (2015). Equivalence tests for comparing correlation and

regression coefficients. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 68(2),

292–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12045

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

25

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3),

297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

Diao, Q., & van der Linden, W. J. (2011). Automated test assembly using lp_solve version 5.5 in

R. Applied Psychological Measurement, 35(5), 398–409.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621610392211

Dube, P., Kroenke, K., Bair, M. J., Theobald, D., & Williams, L. S. (2010). The P4 screener:

Evaluation of a brief measure for assessing potential suicide risk in 2 randomized

effectiveness trials of primary care and oncology patients. The Primary Care Companion to

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 12(June 2008).

https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.10m00978blu

Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. J. (1994). An introduction to the bootstrap. CRC press.

Feinian Chen, Curran, P. J., Bollen, K. A., Kirby, J., & Paxton, P. (2008). An Empirical

Evaluation of the Use of Fixed Cutoff Points in RMSEA Test Statistic in Structural

Equation Models. Sociological Methods & Research, 36(4), 462–494.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124108314720

Gilbody, S., Richards, D., Brealey, S., & Hewitt, C. (2007). Screening for depression in medical

settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): A diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal

of General Internal Medicine, 22(11), 1596–1602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-

0333-y

Goetz, C., Coste, J., Lemetayer, F., Rat, A. C., Montel, S., Recchia, S., … Guillemin, F. (2013).

Item reduction based on rigorous methodological guidelines is necessary to maintain

validity when shortening composite measurement scales. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.12.015

Harel, D. (2014). The effect of model misspecification for polytomous logistic adjacent-category

item response theory models (Doctoral dissertation, McGill University).

Harel, D., & Baron, M. (2018). Methods for shortening patient-reported outcome measures.

Statistical Methods in Medical Research. doi: 10.1177/0962280218795187

Hirsch, O., Donner-Banzhoff, N., & Bachmann, V. (2013). Measurement Equivalence of Four

Psychological Questionnaires in Native-Born Germans, Russian-Speaking Immigrants, and

Native-Born Russians. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 24(3), 225–235.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659613482003

Holling, H., Kuhn, J. T., & Kiefer, T. (2013). Optimal test assembly in practice: The design of

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

26

the Austrian educational standards assessment in mathematics. Journal of Psychology,

221(3), 190–200.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis:

Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang, F. Y., Chung, H., Kroenke, K., Delucchi, K. L., & Spitzer, R. L. (2006). Using the

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse

primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(6), 547–552.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x

Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity

measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–515.

Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9 : a new depression diagnostic and severity

measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–515. https://doi.org/170553651

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9 Validity of a Brief

Depression Severity Measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 605–613.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2

Validity of a Two-Item Depression Screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

Kroenke, K., Strine, T. W., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H.

(2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 114(1–3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026

Kruyen, P. M., Emons, W. H. M., & Sijtsma, K. (2013). On the Shortcomings of Shortened

Tests: A Literature Review. International Journal of Testing.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15305058.2012.703734

Leadbeater, E., Carruthers, J. M., Green, J. P., Rosser, N. S., & Field, J. (2011). Nest inheritance

is the missing source of direct fitness in a primitively eusocial insect. Science, 333(6044),

874–876. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1205140

Leavens, A., Patten, S. B., Hudson, M., Baron, M., & Thombs, B. D. (2012). Influence of

somatic symptoms on patient health questionnaire-9 depression scores among patients with

systemic sclerosis compared to a healthy general population sample. Arthritis Care and

Research, 64(8), 1195–1201. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21675

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

27

Lee, P. W., Schulberg, H. C., Raue, P. J., & Kroenke, K. (2007). Concordance between the PHQ-

9 and the HSCL-20 in depressed primary care patients. Journal of Affective Disorders,

99(1–3), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.002

Levis, A. W., Harel, D., Kwakkenbos, L., Carrier, M. E., Mouthon, L., Poiraudeau, S., … Mills,

S. D. (2016). Using Optimal Test Assembly Methods for Shortening Patient-Reported

Outcome Measures: Development and Validation of the Cochin Hand Function Scale-6: A

Scleroderma Patient-Centered Intervention Network Cohort Study. Arthritis Care and

Research, 68(11), 1704–1713. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22893

Levis, B., Benedetti, A., Riehm, K. E., Saadat, N., Levis, A. W., & Azar, M. (2018). Probability

of major depression diagnostic classification using semi-structured versus fully structured

diagnostic interviews. British Journal of Psychiatry. 212(6), 377-385..

Liu, J. P., Ma, M. C., Wu, C. Y., & Tai, J. Y. (2006). Test of equivalence and non-inferiority for

diagnostic accuracy based on the paired areas under ROC curves. Statistics in Medicine,

25(7), 1219–1238. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2358

Manea, L., Gilbody, S., Hewitt, C., North, A., Plummer, F., Richardson, R., … McMillan, D.

(2016). Identifying depression with the PHQ-2: A diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 203, 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.003

McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M.-H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation

analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64

Merz, E. L., Malcarne, V. L., Roesch, S. C., Riley, N., & Sadler, G. R. (2013). A multigroup

confirmatory factor analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 among English-and

Spanish-speaking Latinas. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(3), 309.

https://doi.org/10.1021/nn300902w.Release

Moriarty, A. S., Gilbody, S., McMillan, D., & Manea, L. (2015). Screening and case finding for

major depressive disorder using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis.

General Hospital Psychiatry, 37(6), 567–576.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.06.012

Muraki, E. (1992). A Generalized Partial Credit Model : Application of an EM Algorithm.

Applied Psychological Measurement, 16(2), 159–176.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (2012). Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis With Latent

Variables. Mplus User’s Guide (Seventh Edition), 1–850. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-

0447.2011.01711.x

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

28

R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation

for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. Retrieved from https://www.r-project.org/

Razykov, I., Hudson, M., Baron, M., & Thombs, B. D. (2013). Utility of the Patient Health

Questionnaire-9 to assess suicide risk in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care &

Research, 65(5), 753–758. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21894

Reise, S. P., Widaman, K. F., & Pugh, R. H. (1993). Confirmatory factor analysis and item

response theory: two approaches for exploring measurement invariance. Psychological

Bulletin, 114(3), 552.

Rief, W., Nanke, A., Klaiberg, A., & Braehler, E. (2004). Base rates for panic and depression

according to the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire: A population-based study. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 82(2), 271–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2003.11.006

Rizopoulos, D. (2006). ltm: An R package for latent variable modeling and item response theory

analyses. Journal of Statistical Software, 17(5), 1–25.

Sjonnesen, K., Berzins, S., Fiest, K. M., Bulloch, A. G. M., Metz, L. M., Thombs, B. D., &

Patten, S. B. (2012). Evaluation of the 9–Item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ–9) as an

Assessment Instrument for Symptoms of Depression in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis.

Postgraduate Medicine, 124(5), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2012.09.2595

Smith, G., Mccarthy, D. M., & Anderson, K. (2004). On the sins of short-form development (vol

12, pg 102, 2000). Psychological Assessment, 16(3), 340.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., & Williams, J. B. W. (2000). Validation and utility of a self-report

version of PRIME-MD. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry,

2(1), 31.

Stanton, J. M., Sinar, E. F., Balzer, W. K., & Smith, P. C. (2002). Issues and strategies for

reducing the length of self-report scales. Personnel Psychology, 55(1), 167–194.

Thombs, B. D., Benedetti, A., Kloda, L. A., Levis, B., Nicolau, I., Cuijpers, P., … Ziegelstein, R.

C. (2014). The diagnostic accuracy of the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), Patient

Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for detecting

major depression: protocol for a systematic review and individual patient data meta-ana.

Systematic Reviews, 3(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-124

Van der Ark, L. A. (2005). Stochastic ordering of the latent trait by the sum score under various

polytomous IRT models. Psychometrika, 70(2), 283–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-

000-0862-3

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

29

Van der Linden, W. J. (2006). Linear models for optimal test design. New York: Springer.

Wittkampf, K. A., Naeije, L., Schene, A. H., Huyser, J., & van Weert, H. C. (2007). Diagnostic

accuracy of the mood module of the Patient Health Questionnaire: a systematic review.

General Hospital Psychiatry, 29(5), 388–395.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.004

Youden, W. J. (1950). Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer, 3(1), 32–35.

https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

30

Table 1. Patient demographic and diagnostic characteristics (N = 7850)

Sociodemographic variables Summary

Age, years, mean [median] ± SD (range) 52.0 [54] ± 18.1 (18, 102)

Women, n (%) 4335 (55.2)

PHQ-9 score, mean [median] ± SD (range) 5.2 [3] ± 5.4 (0, 27)

Country, n (%)

USA 2781 (35.4)

New Zealand 2528 (32.2)

Australia 1092 (13.9)

Canada 573 (7.3)

UK 478 (6.1)

Cameroon 398 (5.1)

Care Setting, n (%)

Primary care 2928 (37.3)

Non-medical setting 1389 (17.7)

Perinatal care 665 (8.5)

Neurology 607 (7.7)

HIV/AIDS care 398 (5.1)

Oncology 273 (3.5)

Medical rehabilitation 211 (2.7)

Rheumatology 201 (2.6)

Cardiology 100 (1.3)

Stroke care 72 (0.9)

Outpatients with coronary artery disease 1006 (12.8)

Diagnostic Interview, n (%)

CIDI 3949 (50.3)

SCID 2443 (31.1)

DIS 1006 (12.8)

SCAN 352 (4.5)

DISH 100 (1.3)

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

31

Classification system, n (%)

DSM-IV 6859 (87.4)

ICD-10 822 (10.5)

DSM-V 169 (2.2)

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

32

Table 2. PHQ-9 items and discrimination parameters from the generalized partial credit

model

Item

Number

Description Discrimination

Parameter

1 Little interest or pleasure in doing things 1.95

2 Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless 2.40

3 Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much 0.93

4 Feeling tired or having little energy 1.37

5 Poor appetite or overeating 1.08

6 Feeling bad about yourself – or that you are a failure or have

let yourself or your family down

1.90

7 Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading newspaper

or watching television

1.41

8 Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have

noticed? Or the opposite – being so fidgety or restless that

you have been moving around a lot more than usual

1.29

9 Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting

yourself in some way

1.77

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

33

Table 3. Items included in optimal short forms of each length with item 9 included and item 9 excluded

Item Number (X indicates inclusion)

Short

Form

Length

1

Little

interest

2

Feeling

down

3

Sleep

problem

4

Feeling

Tired

5

Appetite

6

Feeling

failure

7

Concentration

8

Physical

Movement

9

Thoughts of

Death or Self-

Harm

Item 9 Eligible for Inclusion in Short Forms

1 X

2 X X

3 X X X

4 X X X X

5 X X X X X

6 X X X X X X

7 X X X X X X X

8 X X X X X X X X

Item 9 Ineligible for Inclusion in Short Forms

1 X

2 X X

3 X X X

4 X X X X

5 X X X X X

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

34

6 X X X X X X

7 X X X X X X X

8 X X X X X X X X

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

35

Table 4. Reliability and validity results of the candidate short forms

Form

Length

Cronbach’s alpha (95% CI) Correlation of summed

scores (95% CI)

Correlation of factor

scores (95% CI)

Item 9 Eligible for Inclusion in Short Forms

1 NA 0.527 (0.511, 0.543) NA

2 0.533 (0.504, 0.563) 0.804 (0.796, 0.811) 0.800 (0.792, 0.808)

3 0.727 (0.712, 0.741) 0.863 (0.857, 0.868) 0.869 (0.863, 0.874)

4 0.801 (0.790, 0.810) 0.892 (0.887, 0.896) 0.895 (0.890, 0.899)

5 0.809 (0.799, 0.819) 0.920 (0.916, 0.923) 0.912 (0.909, 0.916)

6 0.835 (0.826, 0.843) 0.939 (0.937, 0.942) 0.931 (0.928, 0.934)

7 0.846 (0.839, 0.854) 0.971 (0.970, 0.973) 0.980 (0.979, 0.980)

8 0.858 (0.851, 0.865) 0.986 (0.986, 0.987) 0.989 (0.989, 0.990)

9 0.866 (0.860, 0.873) 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) 1.000 (1.000, 1.000)

Item 9 Ineligible for Inclusion in Short Forms

1 NA 0.781 (0.772, 0.79) NA

2 0.779 (0.763, 0.794) 0.849 (0.842, 0.855) 0.860 (0.855, 0.866)

3 0.816 (0.806, 0.826) 0.887 (0.882, 0.892) 0.891 (0.886, 0.895)

4 0.805 (0.795, 0.814) 0.919 (0.916, 0.923) 0.910 (0.907, 0.914)

5 0.832 (0.824, 0.840) 0.940 (0.936, 0.941) 0.930 (0.927, 0.933)

6 0.845 (0.838, 0.852) 0.970 (0.969, 0.971) 0.978 (0.977, 0.979)

7 0.857 (0.850, 0.863) 0.984 (0.984, 0.985) 0.988 (0.987, 0.988)

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

36

8 0.866 (0.860, 0.872) 0.997 (0.997, 0.997) 0.998 (0.998, 0.998)

Bold values represent those of the final selected form.

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

37

Table 5. Diagnostic accuracy results of the candidate short forms and their non-inferiority test results

Form

Length

Optimal

Cutoff

Sensitivity (95% CI) P-value Specificity (95% CI) P-value

Item 9 Eligible for Inclusion in Short Forms

1 1 0.420 (0.369, 0.437) 0.976 0.943 (0.930, 0.954) 0.000

2 1 0.929 (0.900, 0.950) 0.000 0.650 (0.592, 0.685) 0.976

3 2 0.892 (0.843, 0.927) 0.000 0.717 (0.680, 0.751) 0.976

4 3 0.858 (0.810, 0.895) 0.000 0.776 (0.744, 0.805) 0.976

5 4 0.806 (0.749, 0.853) 0.000 0.826 (0.798, 0.851) 0.066

6 5 0.837 (0.808, 0.863) 0.000 0.837 (0.808, 0.863) 0.000

7 7 0.814 (0.715, 0.884) 0.000 0.849 (0.820, 0.873) 0.000

8 7 0.856 (0.855, 0.857) 0.000 0.802 (0.801, 0.804) 0.976

9 10 0.761 (0.679, 0.787) NA 0.866 (0.836, 0.892) NA

Item 9 Ineligible for Inclusion in Short Forms

1 1 0.916 (0.877, 0.944) 0.000 0.650 (0.599, 0.698) 0.976

2 2 0.880 (0.825, 0.919) 0.000 0.725 (0.688, 0.760) 0.976

3 3 0.844 (0.796, 0.882) 0.000 0.784 (0.752, 0.813) 0.976

4 4 0.788 (0.725, 0.840) 0.000 0.837 (0.809, 0.861) 0.000

5 5 0.792 (0.716, 0.873) 0.000 0.848 (0.820, 0.873) 0.000

6 6 0.855 (0.762, 0.916) 0.000 0.807 (0.773, 0.838) 0.976

7 7 0.844 (0.762, 0.902) 0.000 0.810 (0.776, 0.840) 0.976

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

38

8 8 0.871 (0.786, 0.925) 0.000 0.784 (0.746, 0.819) 0.976

Bold values represent those of the final selected form.

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

39

FIGURES

Figure 1. The left hand plot shows the item information functions for each of the 9 items. The right hand plot shows the test

information function of the PHQ-9.

-4 -2 0 2 4

01

23

4

Item Information Functions

Depressive Symptomology

Info

rmatio

n

Item1

Item2

Item3

Item4

Item5

Item6

Item7

Item8

Item9

-4 -2 0 2 40

51

015

20

Test Information Function

Depressive Symptomology

Info

rmatio

n

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

40

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Methods 1. Search Strategies

Supplementary Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Study Selection Process

Supplementary Table 1. Characteristics of included primary studies

Supplementary Table 2. The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 Item Short Form (PHQ-

Dep-4)

Supplementary Material References

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

41

Supplementary Methods 1. Search Strategies

MEDLINE (OvidSP)

1. PHQ*.af.

2. patient health questionnaire*.af.

3. 1 or 2

4. Mass Screening/

5. Psychiatric Status Rating Scales/

6. "Predictive Value of Tests"/

7. "Reproducibility of Results"/

8. exp "Sensitivity and Specificity"/

9. Psychometrics/

10. Prevalence/

11. Reference Values/

12.. Reference Standards/

13. exp Diagnostic Errors/

14. Mental Disorders/di, pc [Diagnosis, Prevention & Control]

15. Mood Disorders/di, pc [Diagnosis, Prevention & Control]

16. Depressive Disorder/di, pc [Diagnosis, Prevention & Control]

17. Depressive Disorder, Major/di, pc [Diagnosis, Prevention & Control]

18. Depression, Postpartum/di, pc [Diagnosis, Prevention & Control]

19. Depression/di, pc [Diagnosis, Prevention & Control]

20. validation studies.pt.

21. comparative study.pt.

22. screen*.af.

23. prevalence.af.

24. predictive value*.af.

25. detect*.ti.

26. sensitiv*.ti.

27. valid*.ti.

28. revalid*.ti.

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

42

29. predict*.ti.

30. accura*.ti.

31. psychometric*.ti.

32. identif*.ti.

33. specificit*.ab.

34. cut?off*.ab.

35. cut* score*.ab.

36. cut?point*.ab.

37. threshold score*.ab.

38. reference standard*.ab.

39. reference test*.ab.

40. index test*.ab.

41. gold standard.ab.

42. or/4-41

43. 3 and 42

47. limit 43 to yr=”2000-Current”

PsycINFO (OvidSP)

1. PHQ*.af.

2. patient health questionnaire*.af.

3. 1 or 2

4. Diagnosis/

5. Medical Diagnosis/

6. Psychodiagnosis/

7. Misdiagnosis/

8. Screening/

9. Health Screening/

10. Screening Tests/

11. Prediction/

12. Cutting Scores/

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

43

13. Psychometrics/

14. Test Validity/

15. screen*.af.

16. predictive value*.af.

17. detect*.ti.

18. sensitiv*.ti.

19. valid*.ti.

20. revalid*.ti.

21. accura*.ti.

22. psychometric*.ti.

23. specificit*.ab.

24. cut?off*.ab.

25. cut* score*.ab.

26. cut?point*.ab.

27. threshold score*.ab.

28. reference standard*.ab.

29. reference test*.ab.

30. index test*.ab.

31. gold standard.ab.

32. or/4-31

33. 3 and 32

38. Limit 33 to “2000 to current”

Web of Science (Web of Knowledge)

#1: TS=(PHQ* OR “Patient Health Questionnaire*”)

#2: TS= (screen* OR prevalence OR “predictive value*” OR detect* OR sensitiv* OR valid*

OR revalid* OR predict* OR accura* OR psychometric* OR identif* OR specificit* OR cutoff*

OR “cut off*” OR “cut* score*” OR cutpoint* OR “cut point*” OR “threshold score*” OR

“reference standard*” OR “reference test*” OR “index test*” OR “gold standard”)

#1 AND #2

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

44

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH Timespan=2000-2014

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

45

Supplementary Figure 1. Flow diagram of study selection process

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

46

Supplementary Table 1. Characteristics of included primary studies

First Author, Year Country Recruited Population Diagnostic

Interview

Classificati

on System Total N

Major

Depression

N (%)

Amoozegar,

Unpublished

Canada Migraine patients SCID DSM-IV 203 49 (24)

Arroll, 2010 (1) New Zealand Primary care patients CIDI DSM-IV 2528 156 (6)

Bombardier, 2012 (2) USA Inpatients with spinal cord injuries SCID DSM-IV 160 14 (9)

Eack, 2006 (3) USA Women seeking psychiatric services for

their children at two mental health centers

SCID DSM-IV 48 12 (25)

Fiest, 2014 (4) Canada Epilepsy outpatients SCID DSM-IV 169 23 (14)

Gjerdingen, 2009 (5) USA Mothers registering their newborns for

well-child visits at medical or pediatric

clinics

SCID DSM-IV 419 19 (5)

Kiely, 2014 (6) Australia Community sample of adults CIDI ICD-10 822 33 (4)

Lambert, 2015 (7)a Australia Cancer patients SCID DSM-IV 147 21 (14)

McGuire, 2013 (8) USA Acute coronary syndrome inpatients DISH DSM-IV 100 9 (9)

Pence, 2012 (9) Cameroon HIV-infected patients CIDI DSM-IV 398 11 (3)

Razykov, 2013 (10) Canada Patients with systemic sclerosis CIDI DSM-IV 201 7 (3)

Richardson, 2010 (11) USA Older adults undergoing in-home aging

services care management assessment

SCID DSM-IV 377 95 (25)

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

47

Rooney, 2013 (12) UK Adults with cerebral glioma SCID DSM-IV 126 14 (11)

Sidebottom, 2012 (13) USA Pregnant women SCID DSM-IV 246 12 (5)

Simning, 2012 (14) USA Older adults living in public housing SCID DSM-IV 190 10 (5)

Thombs, 2008 (15) USA Outpatients with coronary artery disease C-DIS DSM-IV 1006 221 (22)

Turner, Unpublished Australia Cardiac rehabilitation patients SCID DSM-IV 51 4 (8)

Turner, 2012 (16) Australia Stroke patients SCID DSM-IV 72 13 (18)

Twist, 2013 (17) UK Type 2 diabetes outpatients SCAN DSM-IV 352 79 (22)

Williams, 2012 (18) USA Parkinson’s disease patients SCID DSM-IV 235 61 (26)

Abbreviations: C-DIS: Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule; CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DISH: Depression Interview and

Structured Hamilton; DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; PHQ-9: Patient Health

Questionnaire-9; SCAN: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders; UK: United Kingdom;

USA: United States of America.

aWas unpublished at the time of electronic database search

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

48

Supplementary Table 2. The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 Item Short Form (PHQ-DEP-

4)

Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been

bothered by any of the following problems?

Not at

all

Several

days

More

than

half the

days

Nearly

every

day

1. Little interest or pleasure in doing things 0 1 2 3

2. Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless 0 1 2 3

3. Feeling bad about yourself — or that you are a

failure or have let yourself or your family down

0 1 2 3

4. Moving or speaking so slowly that other people

could have noticed? Or the opposite – being so

fidgety or restless that you have been moving

around a lot more than usual.

0 1 2 3

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

49

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL REFERENCES

1. Arroll, B., Goodyear-Smith, F., Crengle, S., Gunn, J., Kerse, N., Fishman, T., ... & Hatcher,

S. (2010). Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary

care population. The Annals of Family Medicine, 8(4), 348-353.

2. Bombardier, C. H., Kalpakjian, C. Z., Graves, D. E., Dyer, J. R., Tate, D. G., & Fann, J. R.

(2012). Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in assessing major depressive disorder

during inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Archives of physical medicine and

rehabilitation, 93(10), 1838-1845.

3. Eack, S. M., Greeno, C. G., & Lee, B. J. (2006). Limitations of the Patient Health

Questionnaire in identifying anxiety and depression in community mental health: many cases

are undetected. Research on Social Work Practice, 16(6), 625-631.

4. Fiest, K. M., Patten, S. B., Wiebe, S., Bulloch, A. G., Maxwell, C. J., & Jetté, N. (2014).

Validating screening tools for depression in epilepsy. Epilepsia, 55(10), 1642-1650.

5. Gjerdingen, D., Crow, S., McGovern, P., Miner, M., & Center, B. (2009). Postpartum

depression screening at well-child visits: validity of a 2-question screen and the PHQ-9. The

Annals of Family Medicine, 7(1), 63-70.

6. Kiely, K. M., & Butterworth, P. (2015). Validation of four measures of mental health against

depression and generalized anxiety in a community based sample. Psychiatry

Research, 225(3), 291-298.

7. Lambert, S. D., Clover, K., Pallant, J. F., Britton, B., King, M. T., Mitchell, A. J., & Carter,

G. (2015). Making Sense of Variations in Prevalence Estimates of Depression in Cancer: A

Co-Calibration of Commonly Used Depression Scales Using Rasch Analysis. Journal of the

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 13(10), 1203-1211.

8. McGuire, A. W., Eastwood, J. A., Macabasco-O'Connell, A., Hays, R. D., & Doering, L. V.

(2013). Depression screening: utility of the patient health questionnaire in patients with acute

coronary syndrome. American Journal of Critical Care, 22(1), 12-19.

9. Pence, B. W., Gaynes, B. N., Atashili, J., O'Donnell, J. K., Tayong, G., Kats, D., ... &

Ndumbe, P. M. (2012). Validity of an interviewer-administered patient health questionnaire-9

to screen for depression in HIV-infected patients in Cameroon. Journal of Affective

Disorders, 143(1), 208-213.

Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression-4

50

10. Razykov, I., Hudson, M., Baron, M., & Thombs, B. D. (2013). Utility of the Patient Health

Questionnaire‐9 to Assess Suicide Risk in Patients With Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis care &

research, 65(5), 753-758.

11. Richardson, T. M., He, H., Podgorski, C., Tu, X., & Conwell, Y. (2010). Screening

depression aging services clients. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(12),

1116-1123.

12. Rooney, A. G., McNamara, S., Mackinnon, M., Fraser, M., Rampling, R., Carson, A., &

Grant, R. (2013). Screening for major depressive disorder in adults with cerebral glioma: an

initial validation of 3 self-report instruments. Neuro-oncology, 15(1), 122-129.

13. Sidebottom, A. C., Harrison, P. A., Godecker, A., & Kim, H. (2012). Validation of the Patient

Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 for prenatal depression screening. Archives of Women's

Mental Health, 15(5), 367-374.

14. Simning, A., van Wijngaarden, E., Fisher, S. G., Richardson, T. M., & Conwell, Y. (2012).

Mental Healthcare Need and Service Utilization in Older Adults Living in Public Housing.

The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(5), 441–451.

15. Thombs, B. D., Ziegelstein, R. C., & Whooley, M. A. (2008). Optimizing detection of major

depression among patients with coronary artery disease using the patient health

questionnaire: data from the heart and soul study. Journal of General Internal

Medicine, 23(12), 2014-2017.

16. Turner, A., Hambridge, J., White, J., Carter, G., Clover, K., Nelson, L., & Hackett, M. (2012).

Depression Screening in Stroke. Stroke, 43(4), 1000-1005.

17. Twist, K., Stahl, D., Amiel, S. A., Thomas, S., Winkley, K., & Ismail, K. (2013). Comparison

of depressive symptoms in type 2 diabetes using a two-stage survey design. Psychosomatic

Medicine, 75(8), 791-797.

18. Williams, J. R., Hirsch, E. S., Anderson, K., Bush, A. L., Goldstein, S. R., Grill, S., ... &

Pontone, G. (2012). A comparison of nine scales to detect depression in Parkinson disease

Which scale to use?. Neurology, 78(13), 998-1006.