Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

-

Upload

programa-regional-para-el-manejo-de-recursos-acuaticos-y-alternativas-economicas -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

0

Transcript of Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

1/40

Economic incentivesor marine conservation

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

2/40

Lead AuthorsEduard Niesten (Conservation International)Heidi Gjertsen (Conservation International)

Project LeadsGiselle Samonte (Conservation International)Leah Bunce Karrer (Conservation International)

Science communication team

Tim Carruthers and Jane Hawkey (University o Maryland Center or Environmental Science)

This publication is funded byGordon and Betty Moore FoundationNational Fish and Wildlie Foundation

Preferred citation:Niesten, E. and H. Gjertsen. 2010. EconomicIncentives or Marine Conservation. Science andKnowledge Division, Conservation International,Arlington, Virginia, USA.

The authors thank Conservation Internationals Marine Management Area Science Program or unding and guidance,the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and National Fish and Wildlie Foundation or fnancial support, andthe project Advisory Committee or input on the study design. The authors also acknowledge the tremendousconservation eorts o the projects eatured in this research. We thank the ollowing groups or providing inormationand assistance with site visits: Ejido Luis Echeverria, WildCoast, Pronatura, International Community Foundation,Natural Resources Deense Council, The Nature Conservancy, Morro Bay Commercial Fishermens Organization,Alto Golo Sustentable, INE, University o Caliornia-Santa Barbara, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, PacifcFishery Management Council, NOAA Coral Ree Conservation Program, US Virgin Islands Department o Planningand Natural Resources, Sea Sense, CI-Ecuador, Nazca, Toledo Institute or Development and Environment, St.Thomas Fishermens Association, Misool Eco Resort, CI-Indonesia, Seacology, Tetepare Descendants Association,Western Solomons Conservation Program, Roviana Conservation Foundation, Community ConservationNetwork, Helen Ree Resource Management Project, Palau Conservation Society, Micronesia Conservation Trust,Conservation Society o Pohnpei, Marine and Environmental Research Institute o Pohnpei, Integrated MarineManagement Ltd, Marine and Coastal Resource Conservation Foundation (Bar Ree), WWF, and the communitiesand governments o all sites. We acknowledge background reports and inormation provided by the ollowingindividuals: Dave Forman, Aaron Bruner, Geo Shester, Patrick Saki Fong, Shona Paterson, Stuart Sandin, GabrielHendel, Sheela Saneidejad, Siri Hakala, and Celet Armedilla-Pontillas.

For more inormation:Giselle [email protected]

Conservation International

Science and Knowledge Division2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500Arlington, VA 22202 USA

www.science2action.orgwww.conservation.org/mmas

The views and conclusions contained in this documentare those o the authors and should not be interpreted asrepresenting the opinions or policies o the U.S. Governmentor the National Fish and Wildlie Foundation. Mention o tradenames or commercial products does not constitute theirendorsement by the U.S. Government or the National Fish andWildlie Foundation.Printed on 100% recycled paper (50% post-consumer).

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

3/40

Chapter 1: Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1Incentives: motivating sustainable behavior ......................................................................1Purpose o the study ...............................................................................................................2Research method ....................................................................................................................4

Guidebook overview ...............................................................................................................5Chapter 2: Three approaches to shaping incentives ............................................................7Buyouts ......................................................................................................................................7Conservation agreements .....................................................................................................9Alternative livelihoods ...........................................................................................................12

Chapter 3: Refections on project design and tool selection ......................................... 15Opportunity cost ....................................................................................................................16Positive and negative incentives: benefts and enorcement ......................................17Perormance monitoring ......................................................................................................19Beneft packages ..................................................................................................................20Choosing approachesproperty rights ......................................................................... 21

Choosing approachesessential capacities ................................................................ 22Choosing approachesurgency o threat and unding potential ............................ 25Drawing on strengths rom each approach ................................................................... 27

Chapter 4: Concluding remarks ...................................................................................................... 29Reerences ........................................................................................................................ .......................... 31Appendix ............................................................................................................................ .......................... 32

Table o contents

Community releases sea turtle caught by fsherman, Ayau, Raja Ampat, Indonesia.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

4/40

f

4

Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

5/401

Chapter 1: IntroductionIncentives: motivating sustainable behavior

Inadequate protection and managemento marine resources has proound

consequences: the oceans house bothessential species and critical ecologicalprocesses, and provide a vital source o oodand livelihoods or large numbers o people,including the worlds poorest. Despite thisimportance, marine species and habitats areincreasingly endangered and fsheries arecollapsing around the world.

Marine managed areas (MMAs) are akey element o global strategy to reverse

these trends, as strategically located andwell-designed MMAs protect biodiversityand enhance resource yields.1,2,3,4 Acomprehensive global MMA system would beeconomically rational given that it could besupported ully by fnancial resources savedby eliminating perverse subsidies to industrial

What are marine managed areas?MMAs, as defned or this booklet, aremultiuse, ocean zoning schemes that

typically encompass several types osubareas, such as no-take areas (e.g.,no fshing, mining), buer zones withparticular restrictions (e.g., no oil drilling),or areas dedicated to specifc uses (e.g.,fshing, diving).

MMAs can take many orms, addressingdierent issues and objectives. SomeMMAs involve areas where multiple uses(e.g., fshing, tourism) are allowed under

specifc circumstances. Others involveareas where no extractive human uses(e.g., fshing, mining, drilling) at all areallowed. Still others restrict certain areasto one specifc use (e.g., local fshing)that is judged to be the most benefcialuse o that area to the exclusion oothers.

The term marine managed areas isoten used interchangeably with marineprotected areas (MPAs) as an inclusive

way o describing dierent types oMPAs ranging rom those with multiple-use to areas o complete protection. Formore inormation on MMAs, see MarineManaged Areas: What, Why and Whereavailable at www.science2action.org.

fsheries (estimated at US$15-30 billionper year). Doing so would create more

employment than supported by thesesubsidies and enhance the sustainabilityo global fsheries.5,6,7,8,9 Nevertheless,

marine protected areascurrently cover only 1%o the oceans, and inmany cases managementleaves considerableroom or improvement,oten due to inadequateunding.5,10 I creation and

eective management oa comprehensive globalsystem o MMAs oers such

substantial ecological and economicadvantages, the challenge is to explainwhy this system has yet to materialize.

A large part o the answer relates todistribution o costs and benefts oconservation. Many benefts are non-market values that accrue to peoplear removed rom resource owners andusers. For example, people around theworld may value the act that leatherbackturtles exist, even i they never seeone themselves. In contrast, the costslargely all on coastal communities, andare immediate and tangible throughlost incomes and orgone consumptiono marine resources. Although globalbenefts rom conservation may outweighgains rom destructive practices, atthe level o resource users the beneftsrom unsustainable use oten exceedthose rom sustainable management.11As a consequence o these misalignedincentives, sustainable management inmany contexts is either economicallyunattractive or unaordable or localdecision-makers, particularly in the short-term.

The challenge o making conservationeconomically attractive is a critical hurdle

or creation and eective managemento MMAs. This relates to constructingeconomic alternatives that make oregoingincome rom unsustainable resource-use a viable and preerred option ordecision makers. In other words, resourceusers need to see tangible rewards rom

$

C 1

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

6/40

f

2

Purpose o the studyThe aim o this study is to provide guidance orconservation practitioners and policy makerswith respect to selecting and deployingincentive-based tools. The role o incentivesin conservation eorts is receiving increasedrecognition, but there are many dierent waysthat projects can incorporate incentives. In

particular, incentives can be dierentiatedby their level o directness. Directness reersto the link between project benefts as anincentive and the desired change in behavior,i.e., how benefts depend on conservationperormance. Paying someone to relinquishfshing rights is a very direct incentive. An

changing behavior i sustainable managementand conservation o marine biodiversity is to beachieved.

This research eort is motivated by theproposition that changes in unsustainablebehavior will require interventions that enhance

the economic appeal o other resource-useoptions, and examines what kinds o site-based interventions show the greatest promiseor doing so. Using a global set o casestudies, the analysis that ollows examinesways in which dierent interventions result inincentives to change resource use. Althoughmarine conservation and MMAs ace a widearray o challenges beyond those discussedhere, i incentives are misaligned at the locallevel then eorts to address other challenges

are ar less likely to succeed.

What is opportunity cost?The opportunity cost o conservation is what is given up by choosing conservation versusother uses o resources. It includes the cost o undertaking the conservation actions (e.g.,program administration, wages or patrolling activities), as well as the value o orgoneresource use (e.g., income lost by not harvesting turtle eggs). This second componentacknowledges that changes in resource-use patterns may come at a cost, and any

intervention must consider how and by whom that cost will be addressed.

The opportunity cost o conservation to resource users is defned as the net benefts(benefts minus costs) that would be received under the next best alternative. For example,when establishing a no-take zone in an area, the opportunity cost to consider is the netbeneft that could be generated by fshing in that area. Although the net beneft o fshingusually denotes revenues minus harvest costs, benefts can also include other componentssuch as the cultural role o fshing activities. These are more difcult to measure, but shouldbe included. Estimating the benefts that will be orgone by shiting to dierent resource usespermits explicit examination o osetting incentives required to elicit this behavioral change.

Conservation practitioners increasinglyare turning to incentive-based approachesto encourage local resource users tochange behaviors that impact biodiversityand natural habitat.12,13,14,15,16,17,18 Althoughpast approaches have employed fnes andpenalties (negative incentives), some current

approaches use compensation o variousorms (positive incentives) to encourageparticular conservation practices. Theseapproaches recognize that conservation canimpose a loss in terms o orgone income oraccess to resources (opportunity cost). Sincepeople ace pressing socio-economic needsin many priority areas or conservation, suchpotential losses can hamper the acceptanceand sustainability o conservation interventions,i.e., unless conservation programs address

economic needs, local resource users willbe compelled to make choices that generateshort-term economic returns regardless odestructive impacts.

example o an indirect incentive is trainingsomeone to be a dive guide, i.e., with theexpectation that they then will be less inclinedto overharvest. This analysis examinesincentives using case studies that representeatures o the ollowing approaches.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

7/403

cash, services, or goods, and are providedperiodically upon veriying that conservationperormance targets are met.

Alternative livelihoodsConservation investorsestablish livelihood activities to

replace unsustainable activitiesby resource users. Income orharvest or their own consumption may bederived rom entirely new economic activitiesor revised orms o previous activities. Whenincome is sought through enterprises, beneftsdepend on market proftability. Whether or notthese enterprises are resource-based, beneftstypically are not contingent on conservationperormance per se.

BuyoutsConservation investorspurchase resource rights orequipment with the intention oretiring them, thereby reducing

the overall level o eort applied to harvesting.Compensation to resource owners or users

is typically in the orm o an up-ront, one-time cash payment, ollowed by governmentenorcement to prevent illegal activities.

Conservation agreementsConservation investors negotiatecontracts by which resource-users orego unsustainableactivities in exchange or

benefts that are conditional on conservationperormance. Benefts may be in the orm o

$

$$$

$

Buyout example: trawl permit and vessel buyout, Morro Bay, USATrawling, the primary method or groundfsh capture on the west coast o the United States,involves dragging large, weighted nets along the sea bottom, damaging habitat and causinghigh bycatch. In 2003, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and Environmental Deense engagedthe Morro Bay bottom trawling industry along the central Caliornia coast to protect marinehabitat. With their support, in June 2005, the Pacifc Fishery Management Council approveda network o no-trawl zones o ~1.5 million hectares o ocean. The regulations were enactedin May 2006, and TNC subsequently purchased six ederal limited-entry trawling permits andour trawling vessels rom commercial fshers. Now, the project seeks to sustain fsheries byleasing permits back to fshers who commit to switching to sustainable gear and practices.

Conservation agreement example: community development fund, Laguna SanIgnacio, MexicoIn 2005, the 43 members o the Luis Echeverria community agreed to protect ~48,500hectares o grey whale habitat, in exchange or annual payments o US$25,000 that supportsmall-scale development projects. The area is monitored by a third party to veriy compliancewith contract terms, and payments are released upon confrmation o compliance withcontract terms. Payments have been used to provide business training and launch newincome-generating activities. Every year, any community member can present a projectproposal or review by the leadership, and all the members vote on the proposals in ageneral assembly. The agreement is fnanced through a dedicated trust und that covers

annual payments, monitoring, and legal expenses. The contract was signed by the communityand NGOs (Pronatura, International Community Foundation, Maijanu), and is designed tolast in perpetuity.

Alternative livelihood example: dive tag fees, Kubulau, FijiThe communities o Kubulau district in southwestern Vanua Levu, Fijis second largest island,have created a network o 13 MMAs, anchored by the Namena Marine Reserve. The siteis one o the best diving areas in Fiji, but it is threatened by poachers rom nearby villagesas well as more distant urban centers. Together with Moodys Namena Resort, the Kubulaucommunities enorce no-take areas against poaching to protect important dive sites, using asurveillance system involving community fsh wardens. The system is fnanced through dive-tag ees paid by dive-tourism operators to the Kubulau Resource Management Committee(KRMC), and the unds are used or community development, tertiary scholarships,operational costs such as patrolling and mooring maintenance, and other managementexpenses. Strong community ownership o the project is made possible by recognition ocustomary fshing rights under Fijian law and is strengthened through extensive technicalsupport rom NGO partners such as Wildlie Conservation Society and Coral Ree Alliance.

C 1

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

8/40

f

4

Project characteristics in the case studiesvary widely and many projects share eatureso multiple approaches. Nevertheless, basicproject design does allow or dierentiation.One important design dierence lies infnancing strategy: typical buyouts involve aone-time, up-ront cost, whereas conservation

agreements explicitly require long-termexternal fnancing and alternative livelihoodsare intended to become sel-fnancing.

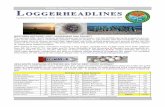

Twenty-seven cases were selected to examine the role o economic incentives in changing behavior.

Another important distinction arises in howbenefts are structured to create incentives.In a buyout, benefts compensate or reducedharvest capacity, and behavior change ismaintained by enorcement (direct incentive).Under a conservation agreement, benefts areprovided over time only i behavior change

is sustained (direct incentive). An alternativelivelihood project results in benefts whenthe livelihood becomes economically viable(indirect incentive).

Research methodThis research involved gathering inormationon case studies representing the threeapproaches listed above. The interventionsin the majority o cases are implemented in

conjunction with MMAs. However, we did notrestrict the cases specifcally to MMAs, asthis would exclude some inormative marineconservation sites rom the sample, particularlythose involving species rather than habitatprotection. The paucity o available datarequired primary data collection. Indeed, theresearch confrmed that most projects donot consistently collect the types o data andinormation required or rigorous quantitativeanalysis o individual project eectiveness,let alone cross-comparisons among projects.Thereore the study relies on qualitativeanalysis.

Key inormants helped compile a large set osuggested candidate projects or inclusion inthe study. Constrained to a sample size o 27cases, random selection rom all possible sites

would not yield an adequately representativesample. Thereore, to ensure broadgeographical representation we constructeda purposive sample that includes examples o

each approach in a wide variety o settings.The purposive sample also sought to includeeective representation o best practices oeach approach (Table 1).

A template was designed to acilitateequivalent data collection or each site. Theinormation collected includes a detailedcharacterization o the project: location,stakeholders, conservation objective,principal threats, intervention model, budget,duration, etc. Project implementers andother key inormants including communityrepresentatives were interviewed to documenteach project; project implementers wereinvited to comment on the drat case studies.The case studies were then analyzed as acollection o project experiences.

Atlantic

Ocean

Pacific

Ocean

Arctic Ocean

Indian

Ocean

Pacific

Ocean

0 2,500 mi

0 2,500 kmCase study sites

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

9/405

Belize

Ecuador

Federated Statesof Micronesia

Fiji

Indonesia

Kiribati

Mexico

Palau

Philippines

SolomonIslands

Sri Lanka

Tanzania

USA

Maya Mountain MarineCorridor scholarships

Galera-San Francisco MarineReserve fsheries management

Navini Island Resort lease

Misool Eco Resort lease;Jamursba Medi scholarships

Laguna San Ignaciocommunity development und

Helen Ree community und

Tetepare and Rendovaincentive payments andscholarships;Olive health clinic

Mafa Island incentivepayments

Buyout Conservation Agreement Alternative Livelihood

Port Honduras MarineReserve AlternativeLivelihood Training

Pohnpei sponge and coralarming

Kubulau dive tag ees;Waitabu marine reserveecotourism

Ayau piggery

Punta Abreojos cooperativeand Marine StewardshipCouncil certifcation

Cagayancillo tourism entryee;Gilutongan Marine Sanctuarytourism revenue sharing

Baraulu sewing

Bar Ree SustainableLivelihoods Enhancementand Diversifcation

St. Croix East End MarinePark interpretive ranger andcommercial captain training

Phoenix Islands ProtectedArea fsheries licenserevenue oset

Northern Gul o Caliorniagill net permit buyout

Mafa Island Marine Park gearreplacement

Morro Bay, CA trawl permitand vessel buyout;Palmyra island purchase;St. Croix gill net and trammelnet buyout

Table 1. List of the 27 case study sites included in the research sample.

C 1

Guidebook overviewChapter 2 presents the three economic

incentive approaches used to characterize thecase studies. Observations gleaned rom thecase study analysis are presented in the ormo project design advice in Chapter 3.

The case studies are incorporated into this

document as brie summaries. For moreinormation, see Economic Incentives orMarine Conservation: Case Studies availableat www.science2action.org.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

10/40

f

6

Lankayan Island, Malaysia.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

11/407

Chapter 2: Three approachestoshapingincentives

BuyoutsBuyouts are the most directapproach with respect toincentives, involving a complete

transer o property or user rights. In a typicalbuyout, the conservation implementer acquires

resource rights or equipment or the purposeo retiring them rom use. Doing so reducesthe level o harvesting eort, and therebyreduces pressure on the resource base. Abuyout can take several orms:

Purchase and retirement o fshingpermits, quotas, or licenses to reduceeort.

Purchase o vessels or gear to reduceeort or change harvesting methods.

Purchase o an area and theaccompanying resource rights.

Buyouts will only reduce harvest eort i thereduction is not readily replaced by eitherexisting resource users or new entrants, whichmeans that total eort or harvest level mustbe eectively regulated.19,20 In a pure buyout,compensation to resource owners or userstypically is in the orm o an up-ront, one-time cash payment. Following the transaction,prevention o violations depends primarily ongovernment enorcement.

Most examples o buyouts are motivated byobjectives related to industry proftability orcommercial stock management, rather thanbycatch reduction or biodiversity conservation.However, buyouts increasingly are beingimplemented or other goals such asprotecting ecosystems and endangeredspecies, reducing bycatch, and conservingbiodiversity in general.21 The buyout casesanalyzed in this study are described in Table

A.1 in the Appendix.

Although the buyout approach in principle isbased on a one-time payment, hal o the casestudies include ongoing incentives beyondthe initial transaction. For instance, in thePhoenix Islands Protected Area, the buyout

Economic incentives dier in the way that they aect resource use. The previous chapterintroduced three approaches to providing economic incentives to conserve natural resources:

buyouts, conservation agreements, and alternative livelihoods. This chapter discusses how thesetools are used by conservation investors (e.g., non-government organizations, government, privatesector) to engage resource users (e.g., local residents, fshers, developers).

$ approach is adapted to conorm to the nationalsystem o annual access agreements orfshing eets, such that a trust und will yieldannual payments in return or enorcement ono-take zones. Thus, one component o theappeal o buyoutsthe apparent simplicityo a one-time transaction as opposed tolong-term engagementis less commonin practice when the approach is appliedto conservation objectives. Nevertheless,the basic proposition o acquiring rights orequipment to reduce extraction pressure oersa powerul direct incentive or resource users.

In Mexicos Northern Gul o Caliornia,ongoing investment in alternative livelihoodeortsin tourism and alternative fshingmethodsis needed to sustain a permitbuyout designed to protect the vaquita,an endemic porpoise species. Developingvaquita-sae fshing gear will take considerabletime, but the threat to the vaquita populationis extremely urgent. Thereore the strategychosen, in addition to the buyout, was tooer temporary compensation or not fshingin certain areas (which does not requirerelinquishing a permit), while collaborating todevelop new fshing equipment that reducesthe risk o vaquita bycatch. Thus, a buyoutcan be used as a stopgap measure whiledeveloping alternative shing gear.

C 2

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

12/40

f

8

A buyout may require substantial uprontunds or a one-time payment. Decliningeconomic proftability as in the Morro Baytrawl fshery can lower opportunity cost andmake a buyout more fnancially easible.However, the conditions needed or a buyoutto succeed (i.e., a limited-entry fshery withreliable enorcement) typically are most likelyto hold in more developed areas that also tendto exhibit higher costs, and thereore buyoutsare unlikely to be cheap investments. Theadvantage o implementing buyouts in moredeveloped areas is that institutions or fsheriesmanagement and enorcement tend to bestronger. In contrast, buyouts in developing

countries may be less costly, but managementand enorcement provisions may not berobust enough to guarantee that conservationinvestors get what they pay or.

The buyout approach oers a direct responseto the problem o excess harvesting pressure.However, implementation o a buyout caninvolve a number o challenges, ranging romhigh fnancing requirements as in the PhoenixIslands Protected Area and Palmyra examples,difcult social and political conditions as inthe Northern Gul o Caliornia example, orcomplex legal and bureaucratic requirementsas in Morro Bay. A recurring theme is thatin many contexts simply removing fshingcapacity through a one-time transaction willnot be enough; local stakeholders demandassistance in pursuing alternatives, whetherthat be in new economic activities or

continuation o fshing activity but with dierentgear or practices. This means that buyoutinitiatives oten will share signicantoverlap with conservation agreements andalternative livelihoods approaches.

Palmyra Island, USA: purchaseLocated 1,693 km south o Hawaii, the Palmyra atoll consists o 275 hectares o landand 6,277 hectares o pristine coral rees. In 1947, the Fullard-Leo amily prevailed in aprotracted US Supreme Court battle with the US Navy or ownership o Palmyra. In 2000,ater more than two years o negotiations, the Fullard-Leo amily agreed to sell the atollto The Nature Conservancy (TNC) or ~US$30 million. The US Fish and Wildlie Service

(USFWS) contributed US$9 million to the purchase o above-water orest lands and mosto the submerged lands and open water, including the rees; these areas are a NationalWildlie Reuge, while TNC manages the remainder o the atoll, about a third o the total, asa preserve.

Phoenix Islands, Kiribati:protected area sheries license revenue offsetThe Phoenix Islands lie in Kiribati, in the central Pacifc Ocean. Their rees are among themost pristine in the tropical Pacifc, but are threatened by oreign commercial fshers.The Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA) was created in 2006, and the boundarieswere fnalized in 2008 to encompass 408,250 km. Using a buyout model, the size o thePIPA no-take zone will depend on fnancing to oset orgone fshing-license revenue. Toguarantee revenue replacement over time, the New England Aquarium and Conservation

International are working with the government to create an endowed trust und romwhich payments to replace fshing-license revenues will continue as long as conservationobjectives o PIPA are met. An initial target o US$25 million is estimated to justiy closing25% o PIPA to commercial fshing.

Northern Gulf of California, Mexico: gill net permit buyoutThe vaquita (Phocoena sinus), a small porpoise endemic to Mexicos Northern Gul oCaliornia, is killed as bycatch in gill nets used to harvest fsh and shrimp. To avoid imminentextinction, the Mexican government launched an initial buyout o permits in 2007, oeringfshers start-up unds or tourism enterprises. Another option was or fshers to receiveunds to purchase new gear. A second round in 2008 included a third option, namely

compensation or not fshing with gill nets inside a designated vaquita reserve. Realisticoptions or alternative livelihoods are limited, and ew fshers will support any plan thatprevents them rom fshing entirely. Thereore, the long-term strategy includes betterenorcement against illegal fshing, maintenance o no-fshing zones, and development ogear that avoids vaquita bycatch.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

13/409

Further guidance on design of buyout projectsCountries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have longexperience with vessel and license buyouts as a fsheries management tool. These measureshave been used to address excess fshing capacity, overexploitation o fsh stocks, anddistributional issues. In Fisheries Buybacks, Curtis and Squires review global experiencewith vessel and license buyouts, and note that these programs can be expected increasingly

to include a ourth major objective, namely conservation o ecosystems and biodiversity.21

The single-most important condition or eective buyouts is limited entry, whichrequires eective registration o licenses and vessels to orm a well-defned group oparticipants, and well-defned boundaries o the fshery. The program must be accompaniedby a mechanism to prevent new entry, re-entry, or other investments that reintroduceharvest pressures. Buyouts can be counterproductive i participants use unds to purchaseupgraded equipment, or i new participants can enter the fshery as proftability increases.Thereore buyout programs may include restrictions on reinvestment o unds received byparticipants and on reuse o the purchased vessel, gear, or license; indeed, many buyoutsrequire that purchased vessels be scrapped to ensure permanent retirement o excessharvest capacity.

Design o buyout initiatives must pay particular attention to clearly dening thescope o the program. For instance, should the program purchase licenses or vessels andgear, or some combination? How will the buyout price be determined? Will the programconsist o a single round or multiple rounds o transactions? When moving beyond fshstock management to pursue conservation objectives, programs may purchase vesselsand licenses or pay fshers to change fshing practices (e.g., restricting location or time oharvest, or defning permissible gear). The program also must decide whether it will ocus onull-time or part-time (latent) vessels. Purchasing inactive vessels or permits may be cheaper,but have less impact on overall fshing eort. Indeed, a poorly designed buyout may result inexit by only the least efcient, less proftable vessels, or fshers that were already planning to

retire, again undermining the objective o reducing harvest pressure.Financing buyouts typically involves some combination o industry, government, and NGOsupport, depending on the extent o benefts to industry and to the public. However,although vessel and permit owners are likely to benet rom a buyout, crew membersoten do not. The potential decrease in employment may require investment in retraining orbusiness grants to acilitate a transition to new economic activities.

For urther discussion o specifc design considerations and review o practical experiencesin buyout programs, see: Curtis, R. and D. Squires. 2007. Fisheries Buybacks. BlackwellPublishing, Oxord.21

onservation agreements Parties and their rights and

responsibilitiesAn agreement typically involves twoprincipal partiesthe resource userswho agree to collaborate in conservationand orego destructive practices, and

the investor who agrees to providecompensatory benefts. An agreementmay incorporate other parties, such as bydefning the role o government agenciesor other partners in monitoring activities.

$$$

C 2

Conservation agreements oerdirect economic benefts toresource users in exchange

or changes in resource-use practices. Adistinction between this approach and buyoutsor alternative livelihoods is that it explicitly

provides ongoing delivery o benefts romexternal sources. A key eature o conservationagreements is that benefts are conditionalon conservation perormance, thus requiringeective monitoring. The ollowing areomponents o a conservation agreement:

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

14/40

f

10

eature all the components o a comprehensiveagreement. For instance, several lack ormalperormance monitoring or sanctions or non-compliance. Provisions or monitoring andthe types o conservation actions/non-actionsrequired o resource users vary widely. Inmost agreements, resource owners commit

to establishing and respecting an MMA insome orm. In some cases, the MMA is legallydesignated while in others it is an agreementto observe management rules within a defnedarea without ormal protected status.

Long-term nancing is a commonchallenge or conservation agreementprojects. The Laguna San Ignacio easement issupported by an endowed und. In the MisoolEco Resort case, sustainability is ensured

by the presence o a private enterprisewith a long-term stake in the success othe agreement. However, the other casesremain dependent on short-term grant cycles,aecting both the reliability o the beneftstream and the ability o implementers toexecute project management and monitoringroles.

The conservation agreement approach hasmet with some resistance rom skepticalconservationists, oten due to incompleteunderstanding o how agreements can beadapted to dierent contexts. For example,there are concerns about an inux o cashinto a small, remote community, but benetpackages can comprise in-kind benetsor unds or community development,as in the Tetepare and Rendova examples.Another misunderstanding is the impressionthat local stakeholders lose their resourcerights. However, under most conservationagreements stakeholders retain their rightsand simply agree to exercise these rights inparticular ways; should the agreement becomeunacceptable to resource owners, theyusually can withdraw rom the arrangementand dispose o their resources as theysee ft (a notable exception is Laguna SanIgnacio, where the community has signed anagreement in perpetuity). The conservationagreement case studies suggest that the basicproposition o providing benefts in return orconservation commitments resonates with

resource users in many settings around theworld.

Conservation commitmentsAn agreement stipulates prohibitedand required activities that will be theresponsibility o the resource users,designed to advance conservationobjectives, e.g., observing no-take zones,ending certain practices such as dynamite

fshing, or conducting patrols to deterpoachers. Benets

In return or conservation actions romresource users, the conservation investoragrees to supply a defned beneftpackage. The value o benefts shouldbe commensurate with opportunitycoststhe value o orgone resourceuse (e.g., reduced fsh yields rom notusing destructive gear) and the cost o

conservation actions (e.g., wages orpatrolling activities). Beneft packagescan include cash payments, but theyusually consist o investments in socialgoods such as scholarships or communitydevelopment unds.

Sanctions or non-complianceBenefts are provided in return oradherence to conservation commitments.I commitments are not met, beneftsmust be adjusted; a thorough agreementwill defne how benefts are aected byparticular types o inractions. Typically,reductions in benefts will be temporaryto allow an opportunity to improvecompliance and restore ull benefts.

Perormance monitoring protocolGiven that benefts are contingenton perormance, compliance withconservation commitments must bemonitored to justiy continued beneftdelivery. This means that commitmentsmust be defned in a way that is amenableto monitoring, and the parties to theagreement must agree to compliancestandards and means o measuringperormance with respect to thosestandards.

Table A.2 in the Appendix lists theconservation agreement cases in the study.Though rooted in the basic concept o a directexchange o benefts in return or conservationcommitments, each agreement is tailored to a

specifc context in which cultural, economic,biological, legal, and institutional actorsall shape beneft packages, conservationcommitments, and implementation details.Some cases, though designed as suchto provide direct incentives as per theconservation agreement approach, do not

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

15/4011

Misool Eco Resort, Indonesia: leaseRaja Ampat is a large archipelago in eastern Indonesias Papua province. In 2005, the MisoolEco Resort (MER) entered into a 25-year lease agreement with the customary ownerso uninhabited Batbitim island to establish a 425 km no-take zone around Batbitim andmany neighboring islands. The lease grants MER exclusive rights to the islands, includinghills, orests, coconut trees, water, animals and the surrounding lagoon. The no-take zone

protects animals, coral rees, turtles, sharks, rays and fsh. The agreement was made underboth customary law and Indonesian law. In addition to paying lease ees, the resort alsoemploys villagers and provides them with health insurance, job training, and English lessons.Under the agreement, the resort regularly patrols the area or illegal fshing and shark-fnningand manages the area or conservation, including observance o the no-take area.

Tetepare and Rendova, Solomon Islands: incentive payments and scholarshipsTetepare Island is located in Western Province o the Solomon Islands and is ~11,880hectares in size. The island retains roughly 97% o its original orest growth. The majorityo the landownerscollectively, the Tetepare Descendants Association (TDA)live in 15zones around the Province, but primarily inhabit our villages on Rendova, the closest islandwest o Tetepare. In return or agreeing to protect the island habitat, villagers receive three

types o benefts, including a scholarship program operated through the TDA, training andemployment opportunities linked to conservation activities and ecotourism, and a paymentscheme in Rendova or turtle nest protection. The turtle project provides cash payments toindividuals and to a village development und or nests ound and protected.

Further guidance on design of conservation agreement projectsThe Nature Conservancy (TNC) and Conservation International (CI) have developed aPractitioners Field Guide or conservation agreements in marine contexts, drawing on thecollective feld experience o many dierent organizations. The manual describes a step-by-step process in our phases, rom initial scoping o potential or the approach in a given siteto on-the-ground implementation. The Guide itsel is complemented by additional resourcesavailable online at www.mcatoolkit.org. The process described in the Guide is applicable toa wide variety o agreement types, ranging rom ormal leases and contracts that rely on legalrameworks to inormal arrangements that rely on non-legally binding covenants betweenimplementers and resource owners. Similarly, the process is applicable whether theconservation agreement targets specic areas, harvesting methods, resource access,or any other proposed behavior change with respect to resource use.

The our phases consist o easibility analysis, engagement, agreement design, andimplementation. O the several elements to be considered in the easibility analysis,

among the most important is the presence o a clear agreement counterpart(individuals, community, management entity, etc.) who is in a position to make concretecommitments and undertake actions that advance conservation objectives in returnor specifed benefts. The purpose o the engagement phase is to reach a sharedunderstanding between the implementer and the resource users with respect to theconservation agreement approach. This encompasses understanding o the motivationsor conservation, the actions required, the implications o changes in resource use, and,critically, the act that benefts are contingent on verifed compliance with agreement terms.Once all stakeholders ully comprehend and consent to the conservation agreement model,the agreement design phase can proceed. To design the agreement, the implementerand resource users work toward mutually agreeable terms on specic actions,

compensatory benets and perormance metrics, as well as consequences o non-compliance.

The implementation phase can begin ater the conservation agreement terms have beenfnalized. Implementation will include many dierent elements, but one o the most criticalactivities or the conservation agreement approach is monitoring to veriy that the

C 2

(continued on ollowing page)

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

16/40

f

12

Further guidance on design of conservation agreement projects (continued)parties to the agreement are ullling their commitments. This compliance monitoringtypically will be accompanied by other monitoring eorts that measure both biological andsocio-economic impacts o the agreement.

For detailed guidance on designing and implementing conservation agreements, see: TheNature Conservancy and Conservation International. 2009. Practitioners Field Guide orMarine Conservation Agreements. Final V1. Washington DC. 74 pp.22

interventions. Indeed, several cases examinedin this study suggest that acceptance obuyouts oten requires adding alternativelivelihoods to overall project design, as

seen in the Northern Gul o Caliornia case.However, under the alternative livelihoodsapproach, support or new activities is notpositioned explicitly as compensation ordisplacing unsustainable behavior. Thissupport is not necessarily conditional; theincome or production rom the new activityis what osets the orgone resource use.The alternative livelihood cases examined inthis study are described in Table A.3 in theAppendix.

The opportunity cost o conservation tendsto be low in the alternative livelihood cases,which might be expected given that highopportunity cost could make it hard to fndcompetitive alternatives. Although the benetlevel needed to overcome opportunity costmay be low, alternative livelihood programsalso incur costs o providing continuedtechnical assistance to overcome capacitygaps; thus, the approach can entail anexpensive long-term commitment. Inthe cases studied, one-time investmentsin Baraulu and St. Croix did little to impactlivelihoods or reduce pressure on resources.The projects in the Philippines opted orlonger-term investments, but reduced the needor external unding by using tourism revenueand by issuing loans rather than grants.

Social expectations with respect todistribution o benets can pose achallenge or alternative livelihood

projects. Successul projects typically includeprominent roles or individuals with particularaptitudes and skills, so there is a tendency orbenefts to accrue to those who are alreadyadvantaged.23,24,25 These people may then acestrong social pressures that can underminea project. Such dynamics were seen in the

Alternative livelihoods

$ The alternative livelihoodsapproach provides incentives toresource users by developing

new income options. Alternative livelihood

support typically is not linked directly toconservation perormance. Rather, newoptions are designed to result in conservationas people pursue activities that are moreproftable than unsustainable resource use.Alternative livelihood interventions can takethree orms:

Transorm existing resource extractionto sustainable use. Many projects inthis category involve working with fshersto adopt management practices such asrationalizing harvest levels or establishingno-take zones to enhance resilience o theresource base. Thus, improved prospectsor continued extraction serve as theincentive or resource users.

Encourage new commercial activitiesthat do not involve harvesting but relyon ecosystem quality. For example,ecotourism requires intact ecosystemsand abundance o species. The incentiveor conservation derives rom the act thatecosystem health sustains the provisiono environmental goods or servicesessential to the non-consumptive income-generating activity.

Pursue new activities that are notor only peripherally related to theecosystem. The intention is to reducedependence on marine resources, as in aproject that encourages fshers to becomearmers or livestock keepers. Incomerom non-marine activities serves as theincentive to cease exploiting the resource

o conservation interest.

Making reduced resource pressure a viableoption or local users by providing alternativeincome options has great intuitive appeal.Consequently, it is no surprise that thisbasic logic underlies many conservation

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

17/4013

Baraulu sewing project, where disputes andjealousies led to lack o cooperation, poaching,and project disintegration. In Pohnpei, projectimplementers have avoided these problems

Cagayancillo, Philippines: tourism entry feeThe municipality o Cagayancillo covers Tubbataha Rees Natural Park (TRNP), which in1988 became the frst national park in the Philippines. The TRNP is under a no-take policythat bars all activities except tourism, research, and management, but it is threatened byillegal fshers rom other coastal communities in the Philippines and as ar away as Taiwanand China. One TRNP management strategy is an alternative livelihood program to replaceincome lost by Cagayancillo residents due to reduced fshing access. The municipalityreceives 10% o park entrance ees. Hal is allocated to road construction, and the rest toa microcredit acility. Two types o loan are oered livelihood loans to support enterprisedevelopment and salary loans against uture income. To date, 80% o recipients usedtheir loans to fnance livelihoods, principally seaweed arming. Low repayment rates in2006/2007 led to a new system o weekly (rather than monthly) collection and group (ratherthan individual) loans.

Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia: sponge and coral farmingIn 2001, the Conservation Society o Pohnpei (CSP) began working with communities to re-establish state sanctioned marine protected areas (MPAs) within Pohnpei lagoon. To provideadditional income-generating opportunities, CSP partnered with the Marine EnvironmentalResearch Institute o Pohnpei to establish sponge arming with communities near MPAs.In 2005, income-generating activities were expanded to hard coral, sot coral, and othermarine invertebrate arming. Sponges are sold locally and or export as beauty products,while corals are exported or the aquarium trade. The arming project is resulting in increasedincome or the 32 participating community members, but it is not being used as an incentiveor conservation per se, since participation in the program or proftability o the arming does

not depend on conservation behavior. However, it does oer an environmentally benignincome source in an area where these are ew and ar between.

C 2

Further guidance on design of alternative livelihood projectsA successul alternative livelihood project requires taking the time to conduct anextensive, participatory process with community members to identiy aspirations andcapacities. Such a process is described in detail in Sustainable Livelihood Enhancementand DiversifcationSLED: A Manual or Practitioners.23 This step-by-step guide alsoemphasizes that rigorous market analysis is essential to ensure that alternative

livelihood investments are tailored to realistic market conditions and opportunities.Sel-evident as these two considerations may seem, they all too oten are insufcientlyincorporated into livelihood initiatives.

The SLED process encompasses three major phasesdiscovery, direction, and doingeach o which entails several specifc steps. The discovery phase generates the inormationneeded by the implementer to acilitate community livelihood development visioning.These visions must be grounded in the skills, capacities, and aspirations o the community,and must reect consensus on the need to change existing livelihood strategies andresource use. During the direction phase, the implementer supports community eorts toidentiy and evaluate ways to achieve their livelihood development visions. This is when

specifc alternatives are explored. Finally, in the doing phase the implementer must buildcommunity capacity and acilitate market access by helping the community cultivatelinks to government, civil society actors, and the private sector .

(continued on ollowing page)

by working directly with individuals who wishto set up their own sponge or coral arm, andextending this opportunity to all communitymembers.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

18/40

f

14

Further guidance on design of alternative livelihood projects (continued)IMM 2008(a) describes this process as one that empowers communities to adapt tochangeincluding changes in management regimes over marine resources.23 Thereore,successul SLED engagement results in benets beyond the immediate rewardso new livelihoods to encompass social resilience. Although specifc vocational skillsrelated to a new livelihood are important, additional value results rom enhancing skills

related to identiying strengths and opportunities, and building networks that acilitatecommunity responses to those opportunities.

For urther discussion o the SLED livelihood development process and review o practicalexperiences in alternative livelihood projects, see IMM 2008(a). Sustainable LivelihoodEnhancement and DiversifcationSLED: A Manual or Practitioners. IUCN.23

To choose sustainable management andconservation o marine biodiversity and naturalhabitat, resource users and decision makersneed to see tangible rewards or changingresource use behaviors. The incentive-basedconservation approaches discussed in this

chapter all recognize that potential loss oincome and access to resources must beoset. The next chapter discusses variousways in which project design must considerlinks between incentives and behavior to drawon strengths o each approach.

Ahus Island, Papua New Guinea.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

19/4015

Chapter 3: Refections on projectdesign and tool selectionThe preceding chapter presented three incentive-based approaches to marine conservation,summarized in Table 2 below. Ideally, one would like to answer the question o which approach is

best, or assuming there is no unique intervention that works best in all settings, how should onedesign a project given the conditions o a site? Answering these questions on the basis o thecase studies is complicated by the act that: 1) the case study approach constrained the researchto a small sample size, and 2) most projects do not collect adequate measures o biological andsocioeconomic outcomes. Nevertheless, the various experiences surveyed do illustrate how thesecases have responded to the challenge o designing incentives or conservation, and how theyhave perormed in dierent settings. Indeed, despite the inability to support statistical analyses,the case studies oer a number o insights into how to choose the appropriate approach and howto successully combine dierent eatures o the approaches to ft a particular context.

C 3 f j

Denitionreward

behaviorchange

Mechanism

Reward type

Maintainingchange

Coststructure

Essentialfor success

Example

project

Direct compensation orbehavior change.

Halt ecosystem-damagingactivity.

Reward provided only ibehavior changes.

Social benefts (e.g., health,education, transportation)Cash.

Conservation investors mustensure continued monitoringor compliance and deliveryo benefts.

Ongoing cost o benefts andmonitoring.

Long-term commitment romconservation investor.

Cover annual teacher salaries

as long as no-take zone isobserved.

Buyout Conservation Agreement Alternative Livelihood

Income or subsistence romnew livelihoods.

Halt reliance onunsustainable resource use.

Reward ollows whenalternative livelihood

becomes economicallyviable.

Income or consumption ogoods rom new livelihoods.

Resource users mustcontinue to engage innew activities and avoidunsustainable resource use.

Cost o training, technicalassistance, and initialunding or new livelihoods.New activities designed tobecome sel-sustaining.

Becomes and remains moreproftable than unsustainableresource use.

Provide skills-training and

start-up unds or ecotourismventure.

Purchase o resource rightsor equipment.

Reduce harvest levels.

Reward compensates orreduced harvest capacity.

Enorcement maintains thechange.

Usually cash.

Government agenciesmust continue to providemonitoring and enorcement.

Large, initial cost.Ongoing enorcement cost.

Well-defned access rightsover the resource.Eective enorcement.

Purchase and retire fshing

licenses to reduce totalharvest in an area.

Table 2. Summary of three incentive-based approaches.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

20/40

f

16

In general, opportunity cost and resourcedependence are correlated, though highdependence can accompany low opportunitycost, as in situations characterized by povertyand dependence on small-scale fshing. Inthese cases, osetting orgone resource-usethrough a buyout or conservation agreementwill be relatively aordable, even i there isa high dependence on the activity. Nearlyall o the cases examined eatured low-medium opportunity cost and low-medium

dependence.Another design consideration is thedistribution o opportunity cost, whichindicates who should receive benefts roma conservation intervention. For example, inthe Phoenix Islands, benefts are providedto the government to compensate or lostrevenues rom license ees. In some cases,urther incentives may be needed to securebuy-in rom additional stakeholders, and otenalso cover at least a portion o enorcementcosts (technically also a component o theopportunity cost o conservation). Buyoutsare generally quite targeted in terms obenefciaries, as compensation goes to thosefshers or boat owners who agree to giveup their licenses or vessels. The alternativelivelihoods approach oten is promoted withthe expectation that the community will beneftas a whole. Many conservation agreementsinclude a und or community-wide benefts.For example, at Navini Island, the landownerclan receives lease payments, and the villagesalso receive unds to support schools andcommunity development projects. Otenit is easier and more equitable to providebenefts to the entire community rather than asubset, and this does not necessarily involvesubstantially higher costs.

Opportunity costAdvice:Incentives are needed to address the opportunity cost o conservation. Incentivesshould be targeted towards legitimate stakeholders whose behavior or resource-use decisionsthe project seeks to inuence, as they ace an opportunity cost o conservation. However, in manycases wider distribution o benefts will be more practical and equitable.

With respect to project design, case studieso all three approaches demonstrate theimportance o addressing the opportunity costo conservationosetting potential loss oincome and access to resources to ensurethat local stakeholders are not orced to bearan undue economic burdenbut strategies todo so can vary widely. Buyouts are predicatedon the notion that air compensation canbe transerred in an upront transaction.Conservation agreements seek to provide

a stream o benefts over time that osetopportunity costs. Alternative livelihoodprojects strive to develop new economicoptions that replace reliance on unsustainableresource use.

When opportunity cost is high, alternativelivelihoods will struggle to generate sufcientincome to replace orgone resource use. Thiswas seen in the Port Honduras case wherelocal fshers expressed the need to continuefshing despite the availability o alternative

jobs linked to tourism and conservation. Highopportunity cost also presents a challengeto more direct incentive strategies, asbuyouts and conservation agreements willinvolve a substantial undraising burden.I the opportunity cost is extremely highor instance, i oshore oil resources arepresentthen incentive-based approachesmay become unaordable, necessitating otherstrategies centered on regulatory reorm andpolicy advocacy.

Alternative livelihood approaches will be moreeasible in low opportunity cost settings, butso will the other approaches. Low opportunitycosts are avorable or buyouts andconservation agreements since opportunitycost orms the basis or determiningcompensation levels. Many conservationagreements are implemented in remote placeswhere there are ew alternatives and costs aregenerally low, as in the Melanesia cases. On

the other hand, areas with high opportunitycosts may be those in which a buyout oragreement is most needed to induce resourceowners to embrace conservation, as in thecase o Laguna San Ignacio.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

21/4017

C 3 f j

Port Honduras Marine Reserve, Belize: Alternative Livelihood Training (ALT)The Toledo Institute or Development and Environment (TIDE) co-manages Belizes PortHonduras Marine Reserve (PHMR) with the Department o Fisheries. Many local fsherscomplain o illegal fshers rom neighboring Honduras and Guatemala. Although most arrestcases involve oreigners, some are locals involved in the TIDE training programs. TIDEoperates an Alternative Livelihood Training (ALT) program to link sustainable natural resource

management with livelihoods or local communities. The ALT program provides training inecotourism felds such as kayaking, birding, y-fshing, diving, hospitality, and small businessmanagement. Since tourism has not met growth expectations, trainees increasingly arelooking or other opportunities to use their new skills. Despite the ALT, people say theirincome is insufcient or daily household needs, and community representatives argue orrelaxed restrictions on fshing and harvesting o marine resources.

Navini Island Resort, Fiji: leaseNavini is one o 32 small islands in Fijis Mamanuca group. The Navini island MMA existsby agreement between the Navini Island Resort and the chiey clan o the Tui Lawa, theparamount chie o the Malolo region. The MMA protects the rees surrounding the islandwith a complete ban on extraction o any resources. Surveillance and monitoring o illegal

activities alls under the daily duties o resort sta, who inorm the Tui Lawa o inractionswhich he addresses using traditional authority mechanisms. The agreement, including anannual payment o FJD5000, has been renewed every year since 1988. Additional beneftsinclude library books and other materials or the local primary school, and support orcommunity development projects with resources, cash, or labor. Local communities arealso seeing ecosystem benefts as stock recovery around Navini is having positive spillovereects or fshing grounds throughout the Malolo region.

Positive and negative incentives: benets and enorcementAdvice:Both positive incentives rom any o the three approaches and negative incentives in theorm o enorcing laws and regulations are necessary or conservation successthe sources othreats to the resource base determines the balance o incentives and enorcement in successul

project design.

Most sites include a ormal protected area osome kind, as well as ormal laws that supportconservation beyond protected areas. Forexample, the turtle projects in Tanzania, theSolomon Islands, and Indonesia are in remotesites that are rarely visited by enorcementofcers. Thus, weak enorcement gives rise tothe need or additional incentives. Nearly allthe case studies involve providing a beneft tolocal resource users whose activities threatenbiodiversity or resource sustainability. Somecases also ace external pressure, such asfshers rom other regions or countries whoare active in the Phoenix Islands, HelenRee, Cagayancillo, and Galera. In the mostremote case study sites, illegal oreign fshingoperations pose the main threat. The capacity

o local communities to deal with this large-scale threat is limited, so any approachmust not only provide incentives or localresource users to change practices, butalso assist them with enorcement. Severalprojects support community eorts to enorceconservation measures against outside threats,

enhancing security o property rights whilealso providing employment opportunities. Ingeneral, more signifcant external threats implya need or greater emphasis on enorcement,while local threats may be more responsive toincentives.

In buyout cases, government enorcementgenerally remains necessary, whilecompensation serves to achieve equitablereductions in capacity and thereby improveacceptance o conservation measures andstrengthened regulation. The Northern Gul oCaliornia case illustrates how initial relianceon regulation and enorcement ailed to thwartthe risk o extinction, and then the buyoutwas hoped to ease the enorcement burden;

ultimately, a combined investment in thebuyout and enorcement proved necessary.A fshery with limited access is necessary sothat there is a bundle o legal interests thatcan be purchased, traded, or leased. Theseproperty rights must be enorced, otherwiseconservation investors cannot be assured

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

22/40

f

18

Galera-San Francisco Marine Reserve, Ecuador: sheries managementThe 546 km Galera-San Francisco Marine Reserve was established in October 2008 in

Ecuadors Esmeraldas Province. Ecuadors Ministry o the Environment and the EcuadorianNGO Nazca will use a conservation agreement to oset short-term losses to fshers causedby improved management that will generate greater returns in the uture. Preparatoryactions or conservation agreements were signed in February 2010 with the communitiesMarine Reserve association and the Galera fshers. The actions will include designingand implementing a communication program, building capacity or the Marine Reserveassociation to operate as an organized group, creating a seed und to improve livelihoods,mapping fshing areas or marine reserve zonation, designing and implementing fsheriesrules and a monitoring system, and strengthening the fsheries cooperative. These steps willeed into the development o a management plan and a conservation agreement.

Maya Mountain Marine Corridor, Belize: scholarshipsThe Toledo Institute or Development and Environment (TIDE) co-manages Belizes PortHonduras Marine Reserve (PHMR) with the Department o Fisheries. One type o incentiveprovided by TIDE to communities is a scholarship program. This program encourages fshersto give up unsustainable management practices in return or scholarships, thus providingan alternative way or parents to fnance their childrens education. Over 50 students havereceived scholarships. The program targets children whose parents agree to stop usingunsustainable fshing and arming methods. The recipients o the scholarship program areexpected to contribute to conservation eorts and work alongside TIDE on communityoutreach activities. Although scholarships are provided in exchange or commitmentsto oregoing unsustainable fshing practices, eligibility is not directly contingent on

perormance, and there is no explicit trade or ormalized sanction system.

that by acquiring these legal interests theywill quantitatively reduce harvest pressure. Tomaintain the impacts o a buyout, enorcementis necessary to ensure that fshers cannotre-enter the fshery and that new entrants areprevented. The case studies suggest that inthe absence o reliable enorcement, buyout

project design must become more elaborate toincorporate ongoing incentives.

Conservation agreements require the abilityto monitor conservation perormance (seebelow) and to apply and enorce sanctionsin the event o non-compliance. In somecontracts, sanctions may simply take the ormo withholding unds or reducing benefts bysome prescribed amount. Losing eligibility orscholarship unds i caught poaching, as might

occur in Jamursba Medi or the Maya MountainMarine Corridor, is an example. In these cases,government or third party enorcement is notessential. However, in cases such as LagunaSan Ignacio, legal action may be requiredto prevent development that is contrary tothe terms o the contract. In most o theconservation agreement cases, the contract

sought to fll the enorcement void let by anabsence o laws or inadequate application oexisting laws.

In alternative livelihoods, enorcement maynot be emphasized i the new activity ullyreplaces unsustainable behavior. However,

most oten livelihoods need to be part o largerset o interventions, including investment inenorcement. In the absence o enorcement,there may be little to prevent people romcontinuing with the unsustainable behaviorthat the new livelihood is meant to displace.Project design oten appears to assume thattime or income needs o resource users areconstrained such that the alternative incomeopportunity will make the original resource useeither impossible or superuous; however, this

is rarely the case. Building an enorcementcomponent into the project is one possibility.Another is to include alternative livelihoods inan agreement to provide unds or livelihooddevelopment in return or verifed compliancewith conservation requirements. The latterapproach adopts the logic o conservationagreements.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

23/4019

Monitoring is inadequate in most projects,including monitoring o conservationoutcomes, socioeconomic impacts, andperormance o resource users with respectto conservation requirements. Given thenecessity o monitoring in the conservationagreement approach to ensure that beneftsare contingent on perormance, one mightexpect this group o case studies to exhibitbetter monitoring provisions. However, evenamong these cases monitoring leaves room

or improvement, resulting in weaker incentivesi the link between benefts and complianceis not sufciently strong. The importance operormance monitoring or the conservationagreement model means that this tool shouldbe selected only i the desired behaviorchange is amenable to such monitoring andthe project implementers have the capacityto ensure that monitoring takes place. Again,the Laguna San Ignacio easement is a modelagreement in which a third party monitors andreports on compliance on an annual basis, andunds are released based on this reporting.

The conservation agreements that involvedirect payments or sea turtle nest protection

Perormance monitoringAdvice: Ongoing perormance monitoring is critical or the success o conservation agreements,but less so or alternative livelihoods and buyouts. However, all projects will beneft rom greatermonitoring to assess intervention impacts and inorm uture tool selection and project designbased on quantitative analysis.

C 3 f j

are among the best monitored. These projectsdevised compensation ormulas o varyingcomplexity linked to numbers o nests, eggs,and hatchings, as in Mafa Island and Rendova.The Mafa Island case involves per-hatchlingpayments, which means that each hatchlingrom each nest is counted. This providesvaluable inormation regarding conservationperormance o villagers as well as hatchingsuccess rate, which may be low or variousreasons. For instance, the Jamursba Medi

project did not monitor hatching success, andonly recently ound that rates are low due tohigh sand temperatures and nest inundation.The project now relocates many nests, aneed that would have been revealed earlier bybetter monitoring. These projects demonstratehow specifc conservation actions andthe explicit link between conservationperormance and benefts have signifcantimplications or monitoring requirements.The more sophisticated the arrangement, themore imperative it is that perormance andconservation outcomes are closely monitored.Such monitoring has the added beneft thatthe project can better demonstrate actualconservation impact.

Maa Island, Tanzania: incentive paymentsBeore 2001, all turtle nests discovered by residents on Tanzanias Mafa Island werepoached. In 2001, the Mafa Island Turtle Conservation Program was initiated through acollaboration between Mafa Island Marine Park and Mafa District Council, with fnancialsupport rom WWF. The program led to the establishment o a local NGO, Sea Sense,

which trained and paid elected community monitors to patrol nesting beaches, relocatenests when necessary, and assist with data collection. Sta perceived that the monitorswere not sufcient, since 50% o nests were still poached. In 2002, Sea Sense beganpaying individuals or fnding and reporting nests, with the amount depending on thenests hatching success. Under the combined program o nest monitoring, nest protectionpayments, and education programs to raise awareness and concern about sea turtleconservation, the poaching rate decreased to 3% in 2002, 2% in 2003, and less than 1% in2004. Between 2005 and 2008, the incidence o poaching remained low averaging 3.4%.

The alternative livelihood approach does

not depend in the same way on the abilityto monitor perormance, as the investmentis not predicated on an explicit, negotiatedexchange. However, like the other twoapproaches, alternative livelihood interventionsdo beneft rom monitoring to demonstratebiological as well as socioeconomic impacts

o the investment. Although some cases do

include monitoring o certain aspects o themarine environment, with the exception oPunta Abreojos the alternative livelihood casesdo not monitor conservation perormance.For instance, in Ayau there is no monitoringor enorcement protocol or the MPAs or theturtle commitments. Although this does not

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

24/40

f

20

necessarily preclude success, impacts othese programs are difcult to assess dueto the lack o monitoring data. Monitoringo resource trends is also important or

sustainable resource management, asextraction rates must be calibrated withrespect to stock dynamics.

Benet packages

Advice: Benefts should be linked to conservation perormance, sufcient to oset opportunitycosts, and tailored to local needs and aspirations. While cash payments are rare, commonlyseen elements in beneft packages include scholarships or other orms o support or education,direct employment in monitoring and enorcement activities, and support or new and improvedlivelihoods.

The case studies exhibit a wide variety obenefts that can serve as incentives orconservation. Individual cash payments are notvery common in the cases in our study. This isthe orm o beneft that probably most people

associate with direct incentive programs dueto the literature on conservation paymentsand payments or environmental services.However, in some contexts, cash is notungible, or project proponents are concernedwith how the cash will be used. Buyouts havetraditionally involved direct payments to vesselor permit owners, but the buyout examplesin this study also involve loans or alternativelivelihood support. The cases in whichindividual cash payments are provided usuallyalso include some other orm o beneft suchas employment or community developmentunds. A system that pools individual paymentsto und public goods can achieve muchgreater positive impact than small individualcash payments. The ejido members o LagunaSan Ignacio recognized this and chose topool payments to und community projectsrather than divide them among households.Pooled payments can be particularly attractivewhen communities ace institutional or socialchallenges to providing public goods in theabsence o outside support.

Buyouts generally involve upront cashpayments as the primary beneft. Alternativelivelihoods involve providing support to

catalyze new livelihood options that willprovide benefts in the orm o income orsubsistence. Conservation agreementscan incorporate a range o options orbenefts. From individual cash payments to

unds or community development projectsto scholarships, there is a wide range opossible benefts that can create individualor community incentives. Importantly, beneftpackages must respond to resource usersneeds and priorities, typically identifedthrough a participatory consultation process.For instance, i unsustainable resource use isdriven by the need or cash to pay school ees,a beneft package that includes scholarshipsmay be appropriate. Another difculty acedby people at many sites is constrained accessto credit. A beneft package can address thisneed by directing unds to a micro-loan acilityaccessible to community members, as doneusing tourist ees in the case o Gilutongan.

Several projects in the case studies providescholarships. In remote areas, school eesrepresent a major expenditure or households,and lack o cash is the primary obstacle thatprevents parents rom sending their childrento school. For conservationists, paying orschool ees can be relatively inexpensive (orinstance, ~US$10,000 per year would coverthe expenses or all schoolchildren in JamursbaMedi), and is a beneft that is likely to reachnearly every household.

Gilutongan Marine Sanctuary, Philippines: tourism revenue sharingGilutongan Marine Sanctuary (GMS) is located in the Philippines Cebu province. GMS isone o the countrys ew urban MPAs, located 20 km rom Cebu City, the second largesturban area in the Philippines. The ordinance that established the GMS includes a tourism

revenue-sharing scheme between the municipality o Cordova (70%) and the village oGilutongan (30%). Alternative livelihoodsincluding seaweed arming and tourism-basedactivities (catering, lieguarding, boating service, souvenir selling)are promoted to reducedependence on ree resources. Loans are available to fnance new livelihoods, but only 10%o loans have been repaid. Another issue is revenue disputes; municipal ofcials claim theyhave given the allocated share to village ofcials each year, but village ofcials deny this.

-

8/4/2019 Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation

25/4021

Although the conservation agreementapproach oers great exibility in designingbeneft packages to meet locally specifc

needs and aspirations, there is considerableconvergence in the orm that these beneftpackages take. As noted, scholarshipprograms are airly common, and beneftsalso oten include direct employment inpatrolling and monitoring activities. In addition,despite the act that the logic underlying theconservation agreement model is distinctly

C 3 f j

dierent rom the alternative livelihoodsapproach, at least a portion o benefts otentakes the orm o investments in improved

livelihoods and enterprise development.Among our case studies, in addition to thealternative livelihoods projects themselves,nearly hal o the other projects rom thebuyout and conservation agreement examplesprovide alternative livelihood support as acomponent o the beneft package.

Jamursba Medi, Indonesia: scholarshipsJamursba Medi, in Indonesias Papua province, hosts the largest remaining leatherbacknesting population in the Pacifc. World Wildlie Fund (WWF)-Indonesia has worked withthe villages o Saubeba and Warmandi to protect this site since 1993. Past attempts tocreate incentives or turtle conservation included alternative livelihood projects, but these allailed due to lack o transportation and marketing inrastructure. Thus, benefts only accrued

to 24 village patrollers receiving salaries, causing tension in the villages. In 2005, WWFcollaborated with SEACOLOGY (www.seacology.org) to provide 13 three-year scholarshipsor village students in exchange or protecting a 113-hectare nesting beach and 65-hectareringing orest reserve. I a amily is ound poaching eggs, they no longer will be eligible orparticipation in the scholarship program. In August 2007, the villages agreed to protect anadditional 822 hectares, including 25 km o turtle nesting beach.