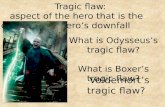

Theories of International Relations Realism Realism Idealism Idealism Constructivism Constructivism.

Dostoevskij's Tragic Idealism

-

Upload

harry-white -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of Dostoevskij's Tragic Idealism

Russian Literature XL VIII (2000) 301-332 North-Holland

www.elsevier.nl/locate/ruslit

DOSTOEVSKIJ'S TRAGIC IDEALISM

HARRY WHITE

First idealism, then pained outrage - that is the entire psychology of the classical, or "heroic", period of our revolutionary history.

(Ol'ga Ljubatovi6)

Dostoevskij's life spanned the heroic period of Russia's revolutionary history. Born four years before the Decembrist revolt, he died the year Alexander II was assassinated; and although he wrote from strong biases, his writings still offer some of the most revealing and accurate insights into the age - its ideals, disappointments, pain and outrage.

We have no better summation of those insights than the two chapters many consider the culmination of his life's work: 'Rebellion' and 'The Grand Inquisitor'. Unfortunately, most miss the important connection between them. The two chapters form parts of a single argument. 'Rebellion' lays the groundwork for the corrective measures the Grand Inquisitor would institute by showing that humankind cannot hope for divine intervention. In fact both chapters repeat the same charge, the first against an aloof and apparently indifferent Father, the second against a quiescent Son, neither of whom reveals himself willing to remedy the evils of this world. Justice therefore requires that the traditional moral foundations of society must be replaced, but the form the new society will take and the means by which it will be established also need to be determined, and Ivan is equally intent on undermining the idea that social justice can be achieved simply through "common sense and science", as the Underground Man sneeringly called it.

0304-3479/00/$ - see front matter © 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. PII: S0304-3479(00)00056-9

302 Harry White

That is why he offers in 'Rebellion' the strongest evidence anywhere in Dostoevskij that social conditions are not the sole cause of evil and crime.

This is no mistake on Ivan's part. The mistake is to believe that against "dedicated socialists and all their works Dostoevsky raged with all his strength" (Payne 1961: 357). For we need to recall that socialists proposed various ways of establishing justice in Russia, everything from a populism modeled after the peasant commune to despotic political control. Dostoevskij was well aware of these differences. He raged against those types of socialism that called for violent and tyrannical political means, and he ridiculed others for their naive conception of human nature. But he also worried about the disillusionment with many of its ideals and sympathized with the longing of Russia's youth for social harmony and justice. Ignoring these distinctions, readers often fail to see that the Grand Inquisitor is indeed a socialist, but one who explicitly rejects the idealism and rationalism of an earlier generation of Russian radicals who thought social justice could be achieved simply by convincing men to give up freedom for bread. To the contrary he denies what too many assume he proposes - a naive conception of human nature along with the equally naive hope that justice can be achieved through the elimination of hunger and poverty. The Grand Inqui- sitor is after all a despot, and 'Rebellion' provides the reasons why he of necessity must resort to despotism to establish justice.

What makes these chapters so compelling is that they go to the heart of the disappointment experienced by Dostoevskij and so many others who sought justice in Russia and beyond. Dostoevskij refused to abandon those hopes, but he soon came to believe along with the nihilists that the first generation of reformers had entertained an unworkable view of man and society. Specifically he felt that given the condition of the Russian people, their profound religiosity, their savagery, their extreme propensity for debauch and suffering, that social reform could not presently be realized by other than despotic means. His criticism of later versions of radical socialism centered on the unacceptable means reformers would necessarily have to exploit to establish justice. But herein lay a problem, which he faced up to, if at all, only with the greatest difficulty. Dostoevskij's refutation of utopian socialism, based on his profound sense of human criminality, cut more ways than one. Human nature as Dostodvskij came to understand and portray it undermined the idealism that sustained socialists and Christians alike, the hope so many like him had lived for that without force or violence man and the world might become better. The injustices humanity suffered were indeed horrible, but if traditional Christianity promised no relief for earthly injustice, if idealistic utopias (including those like Dostoevskij's which derived from Christ's vision of brotherhood) were unworkable, and if nihilistic despotism remained unacceptable, what then was to be done?

Dostoevskij's Tragic Idealism 303

Dostoevskij vacillated between tragic resignation and dubious hope, and to sustain that hope the disillusioned radical idealist wound up placing himself in the same position he criticized the socialists for - which was in effect a criticism of his own longings: he preferred to remain, as he said, outside the truth. In the interim between disillusionment and the promise of earthly paradise - a promise neither Dostoevskij nor his many great characters can any longer believe in without irony - Dostoevskij, much like his Grand Inquisitor, presented himself as a Christian who defended beliefs he himself thought might very well be a lie. He did so because in a century of doubt and disbelief what he finally felt men and society needed above all else, that without which they could not go on living, was not bread or railroads, but idealism of some kind, maybe even of any kind, regardless of whether it could be known to be true or not.

I advise you [Alega] never to think [...] about God, whether He exists or not. All such ideas are utterly inappropriate for a mind created with an idea of only three dimensions.

(Ivan Karamazov)

In a letter to Asa Gray, Darwin remarked, "I cannot see [...] evidence of design and beneficence [...]. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created" such a world (May 22, 1860). Ivan drew a similar conclusion when he said that it's "not that I don't accept God, you must understand, it's the world created by Him I don't and cannot accept" (Dostoevsky 1950: 279; quotations from The Brothers Karamazov hereafter noted by page number only).

Dostoevskij felt Ivan's "rejection not of God, but of the meaning of his creation" would reflect "contemporary Russian anarchism" because "the scientific and philosophical rejection of God's existence has been abandoned now [...]. But on the other hand God's creation, God's world, and its meaning are rejected as strongly as possible (May 10 and 19, 1879, see Dostoevsky 1991). That, as Alega says, is "the form taken by atheism today", and that is why Dostoevskij framed Zosima's response to Ivan's blasphemies not as an argument for God's existence, but as a defense of his world: Look "around you at the gifts of God", he says, "nature is beautiful and sinless, and we, only we, are sinful and foolish" (358).

It is therefore contrary to what Ivan insists we must understand to mistake his statements for "atheistic propositions", and to conclude from

304 Harry White

them that he represents Dostoevskij's supreme spokesman "for disbelief in God", one who questions, "If God exists [...] why so much misfortune?" (Jones 1976: 143; Cerny 1975: 32; Jackson 1993: 293). Strictly speaking, neither 'Rebellion' nor 'The Grand Inquisitor' are atheistic tracts. Rather they are theodicies which take for their starting points both the existence of God and, most importantly, the very principles Christianity has preached for centuries: "I accept God and am glad to, and what's more I accept His wisdom, His purpose [...]; I believe in the underlying meaning and order of life; I believe in the eternal harmony in which we shall one day be blended" (279).

To understand the nature of Ivan's critique we need to recognize that atheism in nineteenth-century Russia arose out of "sympathy with mankind, the impossibility of reconciling oneself with the idea of God in view of the excessive evil and suffering of life". It held that "there was no God at all, or if He did exist that he would be an evil God" (Berdyaev 1996: 40, 42). Ivan presents a moral indictment against a persistent faith in a Father and Son who have failed to effectively realize the very values he shares and which those who believe in them claim to uphold. 'Rebellion' specifically employs a negative variation of the traditional argument from design, by which Ivan infers from the unacceptable state of the world a Creator who, if he does exist, must necessarily not be just because he remains indifferent when it comes to earthly suffering and injustice. The evidence of human misery Ivan cites will not logically support the belief, at the core of Christian theology, in a beneficent Creator who is working his will throughout human history. The thrust of his critique is defined quite succinctly in a statement and qualifier from The Notebooks for The Brothers Karamazov: "there is no [...] God, that is, the God that you preached" (1971: 75).

None of this is meant to suggest that Ivan's personal belief in God is by any means certain; nor does it ignore the fact that he does state at other times that God does not exist: Fedor asks, Is "there a God, or not?" Ivan answers, "No, there is no God" (159), and that is all he says on the subject because the question of God's existence or non-existence is not what concerns him. So when Ivan insists, "I am a believer", we must understand that he is not referring to God. Rather he specifically identifies himself as believing in the harmony and justice that all "the religions of the world are built on" (289). Whether Ivan believes God exists or not, his faith remains inspired by and committed to those Christian ideals which Miusov significantly describes as "a beautiful Utopian dream [...] something after the fashion of socialism" (71). It reflects the religious fanaticism of Russia's radical youth whom Bakunin characterized as "believers without God" (1992. 214). The same revolutionary faith won over Raskol'nikov who (as he informs Porfirij) believes literally in God and the New Jerusalem (1965: 278), and a zealous, atheistic Christianity characterizes Satov's pronouncements as well. He, like

Dostoevskij's Tragic Idealism 305

Ivan, believes in God's promise, that, as he says, Christ's "new coming will take place in Russia". Yet to the question of whether he actually believes in God, he can only answer, "I shall believe in God" (1962b: 239).

Writers are fond of celebrating Dostoevskij as a prophet of the evils of communism. Particularly they find the legend of the Grand Inquisitor reveals his "fearful prophecy of a new dictatorial politics and a new pseudo-Christian salvation which was to become the reality of twentieth century Russian communism". The "intuitive genius of Dostoevski [...] discovered the iso- morphism of Christian and Marxist apocalypse" (Lavine 1986:16 and 19). What most of these commentaries overlook is that what Dostoevskij actually did predict was the revival of Christianity within Russia ("Russia will be one and orthodox"; 1950: 377) which would then hopefully inspire the West to reject skepticism and materialism ("the future renewal of all humanity and its resurrection perhaps by [...] a Russian God and Christ"; 1962a: 563) - and that clearly did not happen. But more to the point, Dostoevskij did not so much prophesize what was to become nor was a pseudo-Christianity something he had to intuit. These things were readily apparent to any ob- server of nineteenth-century Russian radicalism. Dostoevskij could easily see that Christian principles of harmony and justice inspired not only holy men like Mygkin and Zosima, but many of the radical activists of his own day. He had after all been imprisoned in part for circulating Belinskij's Letter to Gogol that proclaimed "the spirit [...] of Christianity of our time" which was that "the Orthodox Church [has always been] the servant of despotism, but [Christ] was the first to bring to people the teaching of freedom, equality and brotherhood" (1965: 327, 324). Ne6aev, whether he believed it or not, called Christ "the first revolutionary agitator", and Dostoevskij reports that Belin- skij told him if Christ were to return "He would join the socialists and follow them" (1979: 8). The assumption re-appears in Kolja's observation that if Christ "were alive to-day, He would be found in the ranks of the revolu- tionists" (672).

'The Grand Inquisitor' is, to be sure, an attack upon Catholicism, but the inspiration or at least the need for the legend certainly did not come from the West. The repeated claims by Russian radicals that they were the true, modem disciples of Christ is what no doubt planted the seed in Dostoevskij's mind of the importance of having Christ himself return and show no interest whatsoever in joining the ranks of the radicals, even after the Inquisitor does his best to demonstrate the futility of his response to human suffering. Needless to say it was equally important for Dostoevskij to show that although Russia's radical youth regularly proclaimed their work to be in imitation of Christ, they were, as the Grand Inquisitor admits of his work, "declaring falsely that it is in [Christ' s] name" (300).

What Dostoevskij recognized and tried to distance Christianity from was the fact that, especially in Russia, "socialism in its embryo used to be

306 Harry White

compared by some of its ringleaders with Christianity", and, he goes on to note in words which anticipate the Grand Inquisitor, it "was regarded as a mere corrective to, an improvement of, the latter" (1979: 148). And that comparison extended well beyond the embryonic stage to cover the entire span of Dostoevskij's life. In 1878 The Northern Union of Russian Workers published a manifesto promising to "make Christ's doctrine live once again in brotherhood and equality" (quoted in Venturi 1983: 553). In 1880, the year The Brothers Karamazov was completed, one of the members of The Sou- thern Union of Russian Workers proclaimed "what a fine religion [Christ and the apostles] made - t h e same as socialism" (Kovalskaia 1987: 231). And in 1881, the year Dostoevskij died, Andrej Zeljabov, at his trial for the assassination of Alexander II, testified that he was no longer a member of the Orthodox Church, but added, "At the same time I admit the teaching of Christ to be the basis of my moral convictions. I believe in truth and justice. [...] I hold it to be the duty of a sincere Christian to fight on behalf of the weak and oppressed [...]. That is my faith" (Zhelyabov 1965: 374).

Although Dostoevskij understood the comparison of socialism with Christianity to be seriously misleading, it was not entirely false. For he never denied that socialist ideals were truly based on Christianity, that as Ivan says of his Grand Inquisitor, "the deception is in the name of Him in Whose ideal the old man had so fervently believed all his life long" (310-311). In fact his own later Christian hopes for earthly paradise remained strikingly similar to his early socialist views. As Edie noted, "Dostoevsky's socialism has never been denied - like Berdyaev's, it has merely been de-secularized" (1969: 238). But then again something like de-secularized versions of socialism were not uncommon among the radicals of his day. Thus it may appear ironic or just unfair that Dostoevskij should mock and criticize them for what he himself continued to believe in. But Dostoevskij's criticism of socialism was never so complete as so many assume. As we shall see he continued to express admiration for many of the goals the radical youth dedicated themselves to. The deception and the difference lay in the means they would employ, not in the ideals he shared with them. And if he did often mock their idealism that mockery took aim at his own beliefs as well, not only his own early idealism, but his never-relinquished hopes for earthly renewal.

So if Raskol'nikov prays to God (79) or Ivan warns Smerdjakov that God sees what evil he has committed (767) that is because Dostoevskij did not make these radical intellectuals spokesmen for disbelief in God. Those statements he gave to Kirilov ("I must affirm my unbelief'; 1962b: 636) or Ippolit, who struggles with the possibility that human life is ruled by an ironic nature (1962a: 315ff.). Nor is it quite right to regard them as moral- religious nihilists. Others tended to be assigned that role, sensualists like Svidrigajlov or Stavrogin whom Dostoevskij portrayed as men of utter disbelief, members of an idle rich class who lead meaningless and desperate

Dostoevskij's Tragic Idealism 307

lives, maintained now and then through voluptuous pleasure, but inevitably ending in suicide. The sensualist, Prince Valkovskij, who lives "a gay and charming life without ideals" knows full well the problem men like him face: some fool, he says, "philosophized till he destroyed everything, everything, even the obligation of all normal and natural duties, till at last he had nothing left. The sum total became nil, and so he declared that the best thing in life was prussic acid" (1956: 238; see also Dostoevskij's sketch of this type, a "suicide out of tedium", in his article, 'The Verdict', 1979: 470ff., as well as his comment on it 538ff., quoted in part below).

A revealing list, a kind of taxonomy of the dramatis personae who reappear throughout Dostoevskij's fiction is presented in 'The Dream of a Ridiculous Man'. In the post-lapsarian world of that story there appear amoralists who are characterized as "proud and voluptuous" men who do not "hesitate to commit crime" and if that does not work, "they are prepared for suicide". And while there are many common characteristics, the amoralists in 'Dream' and elsewhere are clearly distinguishable from another type who believes that "science and wisdom" will finally "force men to unite in a harmonious, reasonable society" (1964b: 222). To apply the term nihilist to these men hardly describes them since the "'Nihilists', more than anyone else, believed [...] in their own ideals" and were anything but apathetic (Venturi 1983: 326). While Dostoevskij did infuse them with more skepti- cism than was evident in their prototypes, he well understood the difference between the fervor of men like Ivan and the total despondency of characters like Stavrogin. Men like Ivan have ideals still and believe there remain obligations and duties to fulfill. They are also intensely aware of the moral limits from which they are unable to escape and are horrified when their nihilistic doubles confess to transgressing those limits seemingly without any moral qualms: "You are an idealist", Svidrigajlov exclaims (483), somewhat surprised to find Raskol'nikov upset by his pederasty, and Ivan similarly recoils from Smerdjakov's revelation that he has murdered their father.

So when we speak of the atheism of men like Ivan, we need to distinguish it, as Dostoevskij did, from amoral disbelief. For he was quite specific in depicting the particular form atheism took among the radical intelligentsia as the desire to bring about the New Jerusalem without God, to establish a community of worship without Christ: "socialism is not merely the labor question, it is before all things the atheistic question, the question of the form taken by atheism today, the question of the tower of Babel built without God [...] to set up Heaven on earth" (1979: 26; italics added). As Ivan puts it, those Russian youths "who do not believe in God", or we might add, those like Ivan who reject his world, "talk of socialism or anarchism, of the transformation of all humanity on a new pattern" (278).

Dostoevskij depicted the form atheism took among Russia's youth as political programs which at one and the same time rejected the Father's work,

308 Harry White

even as they sought to implement the Son's vision of brotherhood. He thus recognized two Russian types of believers: the spiritual Zosima and the radical Ivan who diverged not in the ends, not in the harmonious community they both hoped for, but in the means each would adopt to establish earthly peace and justice. "Where Thy temple stood", the Inquisitor tells Christ, "will rise a new building; the terrible tower of Babel will be built again" (300). His atheism explicitly manifests itself in the godless means he employs to establish a harmonious society because, as Dostoevskij believed, socialism for many was "Christianity, only without God" (1968: 406). Explicitly de- nying neither God's existence and certainly not Christ's vision of harmony, the Grand Inquisitor embodies the atheism of Russian radicalism in his denial that God's will as incarnated in Christ's vision has effectively operated or indeed can effectively operate within human history to ameliorate the conditions under which men live and thereby secure a harmonious existence for humankind. Dostoevskij patterned his atheism after the program of radicals like Belinskij, who "knew that the revolution had to begin with atheism. He had to dethrone that religion whence the moral foundations of [...] society [...] had sprung up. Family, property, personal moral responsi- bility - these he denied radically" (1979: 6-7; italics added).

Bakunin said that there "is not, there cannot be, a State without religion" (1970: 84). As Ivan sees it, "There would have been no civilization if they hadn't invented God" (160). The thrust of Ivan's atheism being political, what 'Rebellion' and 'The Grand Inquisitor' challenge is not the existence of God, but, as Ivan puts it, "the idea of the necessity of God" (278). They question what is called political theology, the social-political position that faith in God's purpose is necessary for social harmony. Once we understand the atheistic question properly, that the form it took among the intelligentsia was not theological, but political, we can understand just why Alega says that before all things the most important issue regarding socialism is the question of atheism. His concern has to do with the despotic means atheistic socialism inevitably would have to exploit to organize society and establish paradise on earth - or just in Russia for starters.

Dostoevskij was in no position to argue for the existence of God because he himself doubted it (see below). But whatever doubts he harbored with respect to God it was nevertheless eminently clear that, as Zosima notes, the "people believe as we do, and an unbelieving reformer will never do anything in Russia" (377). To try and organize Russian society along atheistic lines contrary to the people's profound religious beliefs would inevitably require the use of force and violence. That is before all things the problem atheistic socialism posed - its acceptance of government intrusion into the free life of the people. In its present form, and given current conditions among the Russian people, socialism would have to impose its despotic will on Russian society, as had become readily apparent from

Dostoevskij's Tragic Idealism 309

manifestos like Young Russia (1862) with its proposal for the adoption of what it called "Russian Jacobinism", along with the battle cry "To your axes" (quoted in Venturi 1983: 296) - the very weapon Raskol'nikov chooses to dispose of his victim. "We have taken the sword of Caesar", the Grand Inquisitor proclaims, "and in taking it, of course have rejected Thee" (306).

Socialism was not the same as Christianity because while it did indeed proclaim Christ's vision of harmony and brotherhood, it rejected Christ whenever it tried to "force men to unite in a harmonious, reasonable society" (1964b: 222; my italics). In modern times the West had turned to politics to realize the age-old dream of harmony, and now that Russia's youth had entered onto the same path, Dostoevskij noted that their decision amounted to little more than a re-enactment of the ancient Catholic heresy which had first proclaimed "a new Christ [...] seduced by the third temptation of the devil - the temptation of the kingdoms of the world" (1979: 255). He warned not only that socialists were going about establishing harmony in the wrong way, but that there was hardly anything new in their supposedly novel approach to the problem of injustice. That approach had already been tried by the Church, and it had failed for centuries.

Dostoevskij parodied the growing despotic tendencies of the radical intelligentsia in the political programs of Verchovenskij and Ivan, and in Raskol'nikov's article which cannot conceive the benefactors of humanity as anything other than arbiters and legislators, men like Solon or Napoleon, and not men like Christ, who is conspicuously absent from his list of benefactors. Kropotkin observed that "Jacobinists and anarchists have existed at all times among reformers and revolutionists" (1975b: 59), and the clear and present danger of Jacobinism re-emerging in Russia made anarchism appear to many, including Dostoevskij, to be preferable to politically enforced change. That is why he has Zosima warn that, adopting political means and taking up the sword of Caesar, the radicals "aim at justice, but, denying Christ, they will end by flooding the earth with blood" (381). Change, he insists, must remain an exclusively "spiritual, psychological process. To transform the world [...] men must turn into another path psychologically" (363).

Dostoevskij retained the socialist ideals of his youth until he died, in no small part because he viewed them as an expression, however perverted, of the sublime legacy of Christianity. So even though he often portrayed vile opportunists and gullible fools as prominent among the radicals of his day - and he has come in for much criticism for it - he nevertheless fully recognized that what made socialism so appealing was that its ideas "seemed holy in the highest degree and moral" (1979: 148). The "basic point on which socialism will long continue to be based" is "enthusiasm for goodness". In "the purity of their hearts" many call themselves political nihilists "in the name of honor, truth, and true usefulness!" (April 25, 1866). Socialism attracted "rogues and scoundrels", but it also appealed to the most con-

310 Harry White

scientious members of society because like the Christianity Dostoevskij en- visioned - and which, especially in his later writings, offers many compa- risons with utopian socialism (as Miusov, for one, readily acknowledges) - it encouraged their noblest aspirations for the betterment of humankind. Even in his most unrelenting attack on the radicals, he therefore understood that characters like Petr Verchovenskij or Stavrogin were not really seeking justice, but were by their own admission a crook bent on destruction and a nihilist driven by boredom and disease (1962b: 402 and 418).

The politics of Raskol'nikov, Verchovenskij, and Ivan do not embody true social justice because in every case it is characterized by an enthusiasm for the despotism of the few over the many. So when Dostoevskij has Raskol'nikov admit that he "did not commit [...] murder to become the benefactor of humanity" (432), the point is not that socialists do not aim to benefit humanity. The point is that Raskol'nikov and all those who think and act like him are admittedly not really socialists, at least not as it was understood by the radicals of Dostoevskij's generation. They are intellectuals who fancy themselves superior to the people and who have thereby betrayed the beneficent, populist hopes that defined the radical thought of an earlier generation. Those hopes live on still as a dream in the hearts of men like Alega who look forward to a time when "all men will be holy and love one another, and there will be no more rich nor poor, no exalted nor humbled" (30-31).

There is certainly plenty of rage in Dostoevskij's writings, but we need to understand it, not as the rantings of a radical turned reactionary, but as an expression of bitter disappointment in the changes that had occurred in radical thought since the days of his own participation in the Petra~evskij group. Dostoevskij believed that in his youth he might have taken the path of violence and despotism like a Ne~aev, but he didn't because "in those days these things could not even have been imagined [...]. Times were altogether different" (1979: 147). However the nihilists of the sixties seduced a new generation of youths into a different type of political activism with different goals. Thus in a statement indicative of the transformation of Russian radicalism from populism to Jacobinism and one which turned out to be truly prophetic of its future tragedy, ~igalev says: "I started out with the idea of unrestricted freedom and I have arrived at unrestricted despotism" (1962b: 384). Radicalism in Russia had indeed become altogether different!

What Dostoevskij feared was that especially volatile mix of religious fervor and political radicalism, and that is one reason why he named his first great political character after religious schismatics, the Raskol'nild. For those Dostoevskij dreaded most were not the scoundrels, but their betters: he feared "those who believe in God and are Christians, but at the same time are socialists. [...] The socialist who is a Christian is more to be dreaded than the~ socialist who is an atheist" (Miusov is speaking; 1950: 76) - the men and

Dostoevskij's Tragic Idealism 311

women of the Narodniki for example who would convert to Christianity before going to the people and whom Krav6inskij described as experiencing "a faith one can feel only once in one's life [...]. It was not yet a political movement. Rather it was like a religious movement" (qouted in Venturi 1983: 503). The Grand Inquisitor stands out as Dostoevskij's greatest embo- diment of that fear. He like many of the Russian socialists can appropriate not only the appearance but many of the principles of Christianity while at the same time dismissing the apolitical core of Christ's message.

The dreadful irony throughout Dostoevskij's great writings is that men imbued with the promise of Christianity who mistakenly turn to political action present a potentially greater threat to humanity in terms of the bloodshed they might unleash upon the world than any nihilistic pederast or atheistic nonbeliever. To dismiss Ivan or Raskol'nikov as complete unbe- lievers would miss not only what troubles them - that Christianity has not realized what it promised - but Dostoevskij's own stunning insight - that some of the greatest violence to human life would derive from that very promise! Speaking of his own desire "to live for the happiness of all men, for the finding and spreading of truth", Ippolit cannot help noting the absurdity of such desires, that an ironical nature creates "her very best human beings only to make fools of them later". For him Jesus stands as the paramount example of the futility of dedicating one's life to human happiness: the "only creature recognized on earth as perfect" says "words that have caused so much blood to flow that had it been shed at one time mankind would have drowned in it!" (1962a: 315).

Knowing how inspired they were by it, Dostoevskij depicted radical reformers as believers in the promise of Christianity to show how political violence in the modern age, the rivers of blood Raskol'nikov says must flow, was not quite anti-Christian as a radical perversion of Christianity itself - the distorted form Jesus' words took among certain men of the modem age who accepted Christ's vision, but rejected his teachings whenever they became seduced by the ancient Catholic and modern Western heresy of trying to enforce justice by political means. So however much he or his characters inveigh against socialism itself, it is not finally judged to be an unqualified evil, but rather a tragic error that better individuals mistakenly fall into. Coming to face that error and its terrible consequences is the moment of recognition towards which tragic characters like Ivan and Raskol'nikov are driven. What makes them arguably the most compelling characters in all of Dostoevskij's fiction is their struggle to reconcile their desire for justice with the religious principles of humility and acceptance that were especially pronounced in the Russian Orthodox tradition. In that they embody perhaps the central dilemma of Dostoevskij's life and writings, if not Russian culture itself.

312 Harry White

Dostoevskij raged against socialism because he believed it would inevitably lead to violence and tyranny, and we can identify two fundamental reasons why he felt radical violence was inevitable. The first as we have seen had to do with atheism as a political program that violated the beliefs and practices of the Russian people. The second major reason had to do with socialism's supposedly scientific and rational understanding of human nature, its mistaken belief that a just and harmonious society could be achieved simply by eliminating hunger and poverty. If the first reason led to Dosto- evskij 's objection to socialism, the second marked his own disillusionment with it and, as we shall see, proved far more devastating than he may have at first imagined.

II

[A] man [...] harms others [...] almost only when he is obliged to deprive them of things so as not to remain himself without the things he needs. [...] Very often very many people suffer from a shortage of [food and drink], and this is the cause of the largest number of bad actions of all kinds [...]. If this one cause of evil were abolished, at least nine tenths of all that is bad in human society would quickly disappear. Crime would be reduced to one tenth. (Cerny~evskij, 'The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy')

I meant to speak of the suffering of mankind generally, but we better confine ourselves to the sufferings of the children. That reduces my argument to a tenth of what it would be.

(Ivan Karamazov)

Dostoevskij believed "socialism [...] revealed none but abominable perver- sions of nature and common sense" (1979: 6). "Human nature isn't taken into account at all. [...] Human nature isn't supposed to exist", Razumichin contends. "[Y]oung people have been torn away from reality" (1979: 584). They "have nothing but paper schemes and blueprints in their heads", ~atov says (1962b: 132), schemes, according to Razumichin, that "reduce every- thing to one common cause - environment. Environment is the root of all evil - and nothing else!" (1965: 273). And strange as it may seem at first, Ivan shares these opinions. For he discounts any schemes the radical intelligentsia might still entertain for realizing justice solely by eliminating hunger and poverty. Ippolit in The Idiot anticipated Ivan's challenge to traditional belief by offering his fatal disease as evidence of a natural order indifferent to human suffering, but it is important to note that he did not cite, as Ivan does, examples of suffering inflicted by one human being upon another. Thus the

Dostoevskij 's Tragic Idealism 313

"metaphysical rebellion" Camus and others have understood to be practically the sole aim of 'Rebellion' completely ignores the more profound problem of human perversity the chapter addresses.

Vera Figner typified the unreal view of human nature Dostoevskij criticized when she said that "there are more fundamental, more profound motivations than the individual will. [...] [S]ocial conditions are such that, despite individual inclinations, temperaments, or desires, they inevitably produce crime. Hunger and deprivation of all kinds [...] are the true causes of [...] violence against human beings" (1987:15). And most mistakenly assume that that is also pretty much Ivan's position: he is said to declare "that all he understands is that suffering exists and no one is to blame" (Jones 1976: 192- 193). But when Ivan states that none are guilty, he is not referring to the perpetrators of crime, as socialists like Cernygevskij or Figner were wont to do. He is declaring the victims to be innocent: they haven't "eaten the apple and [don't] know good and evil" (282); and he does so to make the opposing point - that their tormentors cannot in any way not be viewed as guilty. Indeed they themselves have to know that "a little creature [...] cannot even understand what's done to her", yet they are drawn to torture the innocent because it is precisely the child's "defenselessness that tempts the tormentor, just the angelic confidence of the child [...] that sets his vile blood on fire" (287). When Ivan contends that the chastisement of innocents really amounts to torture, he is reiterating the same argument Dostoevskij made in discussing the Kroneberg case. (It is one of the news items Ivan cites.) Dostoevskij had ridiculed the defense counsel's contention that the father was motivated to punish his daughter and not torture her, arguing in part that "a seven year old child does not, and cannot, possess sufficient intelligence to observe evil in herself" (see 1979: 220, 232).

Dostoevskij, unlike many of the socialists he attacked, did not view all crimes in the same light. He recognized that some did indeed occur under extenuating, possibly excusable circumstances, while others certainly did not: One man, he noted, kills a passer-bye for an onion, another the man who debauched his wife, a third kills defending his liberty and his life while another "assassinates children for amusement, for the pleasure of feeling their warm blood flow over his hands, of seeing them shudder in a last bird-like palpitation beneath the knife that tears their flesh!" However, though "the criminal who has revolted against society hates it, and considers himself in the right; society was wrong, not he", Dostoevskij felt assured that "in spite of different opinions, everyone will acknowledge that there are acts which everywhere and always, under no matter what legal system, are beyond doubt criminal". According to Frank, the acts Dostoevskij was probably thinking of at this point were those of the prisoner Gazin who was "fond of murdering small children simply for pleasure" (1990: 137).

314 Harry White

Ivan's critique of the single-minded view of crime socialists presented reflects Dostoevskij's own views. He concentrates on acts against children because their absolute injustice remains "so unanswerably clear" (290), which is to say, they are beyond doubt criminal and no one can blame them on society. Ivan of course realizes that keeping to the children "does weaken my case". It reduces it, he estimates, from encompassing "the suffering of mankind generally" to one tenth of its effectiveness (282), but it does not reduce it simply for the reason that children make up a small fraction of the l~opulation, but because other crimes - the remaining ninety percent by Cerny~evskij's estimate - may truly arise out of need and could conceivably be explained without taking human nature into account. Ivan acknowledges that a case against utopian socialism cannot apply to all instances. It cannot encompass all of humanity because it cannot be said that no crimes arise out of hunger or poverty. So Ivan must stick to the children because everyone, everywhere, under any legal system would unfailingly regard the acts Ivan cites as criminal. And he takes care to describe their tormentors variously as a "well-educated, cultured gentleman and his wife", a retired general who lives an aristocratic life of leisure on his "property of two thousand souls" or two "most worthy and respectable people, of good education and breeding". These individuals are clearly neither motivated by poverty nor restrained by any of the supposed benefits of culture and civilization. Rather, they are well- to-do people, similar to characters like Svidrigajlov who desire to add "zest" and "amusement" to their lives, and they offer further proof of what the Underground Man knew all along, that the "most refined, bloodthirsty tyrants [...] are often most exquisitely civilized. [...] Civilization has made man, if not always more bloodthirsty, at least more viciously, more horribly bloodthirsty" (108).

What for Dostoevskij made the abuse of children a crime categorically different from most all others is that it stands out as the one crime not even a socialist could blame upon society - or God for that matter - the crime for which the criminal could not possibly disclaim responsibility. Even before Ivan's critique in The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevskij had been used to citing the abuse of children to trump the socialists' contention that environ- mental conditions were responsible for the evil men do. For example, Tichon tells Stavrogin that "there is not and cannot be any worse crime than what you did to that little girl". Yet the very nature of that crime, he says, is such that there can be "no doubt that you are responsible". Tichon understands it to be the crime which leaves no doubt as to the central question, "Am I or am I not responsible for my actions?" And he believes that for this reason Stavrogin may find salvation because "a Christian accepts responsibility whatever his environment" (1962b: 434-435). Stavrogin, in the Notebooks at least, realizes that his crime was that of an idle gentleman, uprooted from the

Dostoevskij 's Tragic Idealism 315

soil, yet admits that "most of the fault lay with my own evil will, and not with the environment alone" (367).

Perhaps most revealingly in Crime and Punishment Razumichin lashes out against the socialist position that "crime is a protest against bad and abnormal social conditions and nothing more". He complains, as we have seen, that socialists reduce every evil to environment and nothing else. And when Porfirij challenges him by saying he can prove that "environment means a lot in crime", Razumichin agrees, but then cites the one crime which assuredly no one can claim results from abnormal social conditions: "but tell me this: a forty year old man violates a ten year old girl - was it environment that drove him to do it?" (272-273).

Many have commented on the special place children have in Do- stoevskij's writing (see for instance Albert J. Guerard, The Triumph of the Novel or William Rowe, Dostoyevsky: Child and Man in His Works). Nume- rous characters demonstrate a special affection as well as a perverted desire for them, and the victimization and suffering of innocent children stands in Dostoevskij as the greatest outrage imaginable. The psycho-sexual nature of this fascination cannot be underestimated. Even so, the exclusive emphasis upon this aspect of pederasty overlooks the role it plays in Dostoevskij's attacks upon the socialists. Dostoevskij cited the violation of children specifically to counter their denial of moral responsibility, and he did so to no greater effect than in 'Rebellion'. The chapter is perfectly in keeping with what the Underground Man said was mankind's "main defect[,] [...] his chronic perversity, an affliction from which he has suffered throughout his history" (113). It dramatizes in lurid detail what 'Dream of a Ridiculous Man' identified as "almost the sole source of our sins": It was neither the hunger nor poverty socialists cited, but those "outbursts of cruel sensuality that are so common on our earth" (218). Ivan is similarly out to prove that, although environment means a lot in crime, it cannot be lack of bread that drives all men to all crimes, certainly not these crimes. Something else drives them: "I know for a fact there are people who at every blow are worked up to sensuality, to literal sensuality, which increases progressively at every blow they inflict. [...] In every man, of course, a demon lies hidden - the demon of rage, the demon of lustful heat at the screams of the tortured victim, the demon of lawlessness let off the chain" (286-287).

Razumichin complained that socialists believe that "if society is organized on normal lines, all crime will vanish [...] and all men will become righteous in the twinkling of an eye. Human nature isn't taken into account at all. [...] Human nature isn't supposed to exist" (272). Razumichin's warning is the subject of 'Rebellion' which takes into account facts of human nature that too many socialists chose to ignore, but an all too exclusive concen- tration on ecclesiastical and spiritual issues has led too many to overlook the secular faith Ivan is attacking and to miss the crucial connection between the

316 Harry White

two chapters. The narrow insistence that it "is, of course, the Roman Catholic church that Dostoevskij accuses" leads to the presumption that, "'The Grand Inquisitor' [...] sits just a little uncomfortably in the text because it addresses an issue not entirely relevant to the discussion on suffering" (Gunn 1990: 161, 160). Not so. Ivan prepares for the Inquisitor's despotic rule perfectly. He shows that man being "a savage vicious beast" (278), much human suffering results from human viciousness more than food shortages. That point is missed entirely if one believes that "all this evidence of the devil in man is [...] relevant for [...] socialist utopia - the Crystal Palace" because Ivan "is very largely Dostoevskij himself in his younger days, when he was still attached to Fourierist socialism" (Peace 1971: 271; Payne 1961: 343). Again, not so. Ivan mocks Crystal Palace notions of progress as much as the Underground Man did and explicitly debunks the kind of Fourierist, utopian socialism that Dostoevskij may have embraced in his younger days! No utopian idealist, Ivan does not believe that justice will occur in the mere twinkling of an eye. And we must therefore realize that his legend of the Grand Inquisitor dramatizes not so much the evils of despotism as the dilemma faced by generations of radicals and reformers, like him and his creator, once they came to realize that change in Russia, which was so desperately needed, would nevertheless not likely come about through nonviolent, popular means. 'Rebellion' reveals the enormity of the problem. Man is by nature, and not circumstances, a savage, vicious, rebellious beast who prefers the thrill of rubbing excrement in little girls' mouths to a peaceful society having enough bread for everyone. Socialism may be a good thing in what it seeks, but under these circumstances and given the present nature of man and the extreme propensity for crime and debauchery among the Russian people, social justice cannot be realized except through despotic control.

The Narodniki present perhaps the most telling example of what those who sought for justice in Russia had to confront, for they especially insisted on going to the people, but when they did they discovered that the people were so backward and censorship so rigid that it made education, enlighten- ment or just about any type of popular, peaceful reform highly impractical. Worst of all, the people were turning their defenders in to the authorities[ Reformers in Russia had to face a situation a lot different and certainly a lot more difficult than what those in the West confronted. Consequently many Russian radicals came often reluctantly to realize that violence and unpopular political action and control would be required. This caused anarchists to split from communists, and one anarchist and former radical to reject the socialist approach to injustice for the reason that "reason, science and realism alone" cannot produce "social 'harmony'" (1979: 6) - certainly not in holy Russia. For, as we shall see, Dostoevskij discovered in prison the very problem other radicals were to encounter a lot later on. And he summed up the dis-

Dostoevskij 's Tragic Idealism 317

appointing history of several generations of Russian radicals by Sigalev's turn from freedom to despotism. But that terrible disappointment was dra- matized to no greater effect than in his last, great work: The Grand Inquisitor turns to despotism not because he wants to, but because he, like Dostoevskij, comes to realize that reason and science which were supposed to finally eliminate suffering cannot alleviate the problem.

In Notes from the Underground Dostoevskij ridiculed the naive ratio- nalism which held that "when science and common sense have completely reeducated human nature [...] man himself will give up erring of his own free will [...] (1964a: 108, italics in original). And he does it again in 'The Grand Inquisitor': "Freedom, free thought and science will lead them to such straights [...] that some of them [...] will destroy themselves, others [...] will destroy one another, while the rest [...] will crawl fawning to our feet" (307). The Inquisitor picks up where the Underground Man left off to draw the logical political conclusion from the identical view of human nature. He begins by reiterating an essential socialist contention that there is no such thing as crime, but when he does so he is not speaking in his own voice. What he says is that "humanity will proclaim by the lips of their sages that there is no crime, and therefore no sin; there is only hunger" (300; my italics). The Inquisitor may give lip service to this view, but it is not one he believes in any more than he believes in Christianity, for he clearly makes a point of attributing it to others and proceeds to quickly deny it himself.

The problem is that most not only attribute this sentiment to the Inquisitor, but mistake it as central to his argument when in fact it is the very thing he argues against in making his case for despotic measures! Simmons for example typically says that by "giving them bread [...], the Church has enslaved the multitude" (1940: 350). But the Inquisitor's point is that the multitude have to be enslaved because hunger is neither man's sole nor primary m~ot!vation - bread alone will not bring him to live in peace and harmony. And while it may be true that "men are weak, vicious and ignoble and millions of them will lack the strength to give up the earthly bread for the bread of heaven" (Jones 1976: 182), yet this also commonly held view, though correct, misses entirely the other difficulty that arises from man's weakness: because men are vicious, they will not give up the earthly bread they have and willingly share it with others. The sages whom the Inquisitor mocks may believe that only hunger explains crime, but when he proceeds to speak for himself, the Grand Inquisitor specifically denies the notion that there is no such thing as criminality or sinfulness. Taking up the position set forth in 'Rebellion', which is the one Dostoevskij stated over and over again at least since the composition of Notes from the Underground, he reiterates that man is a savage not driven to crime simply by hunger and therefore not likely to accept social reform of his own free will: "No science will give them bread so long as they remain free [...] for they are weak, worthless, vicious,

318 Harry White

and rebellious. [...] [F]reedom and bread enough for all are inconceivable together" (300).

When she comments on these remarks, Temira Pachmuss typically • . ~ . .

understands them m exclusively spiritual terms:

There are but few people who have enough strength to neglect their animal being for the sake of living for the spirit. [...] Man is turned against man because they .stand in a relationship similar to that of one animal toward another, each trying to seize the other's food. [...] Had Christ freed men from the worry about their daily bread, He would also have freed them from this primitive state. (1963: 98-99)

Yet the Inquisitor's point is just the opposite, and he has the evidence in 'Rebellion' to back him up: Free man from the worry of daily bread, while still letting him free to act as he desires and he will continue to turn on his fellow man because, like the vicious animal he is, he does not torment his fellow man because he is in need of bread. "Chernyshevsky used to say that all he would have to do was talk to the people for a quarter of an hour, and he would immediately persuade them to turn to socialism" (April 25, 1866), but the Grand Inquisitor realizes that more than talk is needed to establish socialism. He insists that the overwhelming majority of mankind will not neglect their animal nature for the spirit, as Christians believe, and they won't give it up for bread either, as utopian socialists had hoped. This is the dilemma he presents: so long as man remains weak and vicious there will never be bread enough to placate him and social justice will not be realized except through tyranny. The Inquisitor's opinion of human nature as it presently stands squares perfectly with Dostoevskij's own view, one that was so unavoidable that he gave voice to it in characters as seemingly diverse as Zosima and the Inquisitor. Both Ivan and Zosima recognize the same problem• Ivan's answer, politically enforced equality, Dostoevskij found un- acceptable. Zosima's call for spiritual renewal he believed to be the only solution, but not a very viable one for any but a small minority of exceptional individuals.

We are told that the Inquisitor conceals "beneath his ardent concern for mankind a profound contempt for men [...]. [And] Ivan shares the Inquisitor's contempt for his fellow men" (Leatherbarrow 1981: 157), but that is a rather one-sided view of the problem. Ivan's outcry against man's viciousness was perhaps best explained in Dostoevskij's Diary: "the realization of one's utter impotence to help [...] suffering mankind [...] may convert in one "s heart love

for mankind into a hatred o f it" (541). In this revealing entry Dostoevskij, as it were, anticipates the entire gamut of criticism which has characterized him as everything from a sympathetic lover to a vicious hater of humanity. But for Dostoevskij it was the very love of humanity which leads to hatred, and in

Dostoevskij 's Tragic Idealism 319

Ivan's impotent anger ("I must have justice, or I will destroy myself"; 289), he summed up the frustration of many an idealist like himself whose pained outrage marked the last phase of the heroic age of Russian revolutionary history. And he did indeed foresee what the next phase would likely bring. An outraged idealism continually frustrated would turn to terrorism: the "wise ones [would be] in a hurry to exterminate the unwise who couldn't grasp their Idea" (1964b: 222-223).

The Inquisitor's recognition that freedom and socialism are presently incompatible resulted from a disturbance for Dostoevskij so devastating that he was never able to fully recover idealism of any kind ever again. For his own disillusionment with nonviolent change did not result from the perceived recalcitrance of those in power. Dostoevskij's disillusionment with, as distin- guished from his objection to, socialism had to do with his realization, which he never portrayed more vividly than in 'Rebellion', that the fundamental roadblock to justice and social harmony lay with the people and not the authorities.

There is no better illustration of this change in Dostoevskij's thinking toward the possibility of reform than in the way he re-staged a "disgusting scene" which, he said, remained in his memory all his life (see 1979: 186ff.). The incident involved a courier beating a cabman which led the driver to lash out at his horses. Dostoevskij tells us he was then given to "meditating intensely [...] about everything 'beautiful and lofty'". In those days the words "used to be uttered without irony", and it appeared to him at that time that there was a "cause and effect link" between "every blow dealt at the animal" and "each blow dealt at the man", and in the late forties, during the period of his "most unrestrained and fervent dreams", Dostoevskij imagined that were he to found "a philanthropic society" it would have this courier's troika as its emblem. However he came to realize that he had understood the cruelties in the Russian people "in a too one-sided sense". In the 1870's, couriers no longer beat the people, but the people continued to beat themselves. ("We've left off thrashing the peasants, [...] but they go on thrashing themselves"; 1950: 158). Dostoevskij can now no longer one-sidedly attribute the crimi- nality to social injustice, but to the effects of drunkenness, "some itch for debauch", and "demoralizing idea[s]" like "materialism and scepticism".

In The Notebooks for Crime and Punishment Dostoevskij wrote of that scene, "My first personal insult, the horse, the courier" (1971: 64); but when he finally came to compose the dream that recalls Raskol'nikov's first insult, he revised the scene in light of his new understanding. He removed the courier so that the peasant now beat his horse to death for no apparent cause. (An incident just like it is alluded to in 'Rebellion'.) In other words, Dostoevskij transformed the telling social-political encounter into a senseless act of cruelty, transferring the blame for innocent suffering from a cruel auto- cratic society to the corrupt nature of every ordinary man. (It is noteworthy

320 Harry White

that in his Letters From Russia [1832], which Dostoevskij was perhaps familiar with, the Marquis de Custine also witnessed a client beating a cabman without protest from either the victim or any bystanders. The incident for him typified the Russian acceptance of brutality of men over their inferiors, and the conclusion he drew from it was that it and too many other similar incidents led him who left France a monarchist to return from Russia a republican.)

Crime and Punishment is not Dostoevskij's only work which, as Philip Rahv so excellently showed, "depends on the sleight-of-hand of substituting a meaningless crime for a meaningful one" (1978: 173). Dostoevskij's so- called motiveless or senseless crimes are rather the rule and do in fact make quite good sense. They serve to push into the background the reasons why he himself once believed crime often flourished in countries like Russia. It flourished because a backward nineteenth-century autocracy permitted and accepted massive injustices that other societies had already gone a long way toward reforming, because men can be so impoverished that they have no other opportunity for survival, because rebels truly and fully dedicated to change will sometimes select meaningful targets, like a Tsar, rather than spill blood uselessly and senselessly by killing an old pawnbroker, a provincial slavophile like Satov, or a dissolute sensualist like Karamazov. If "I had killed her just because I was hungry", Raskol'nikov says, "I'd have been happy now" (427). Happy because the crime might then be excused or might possibly lend support to the idea that even murder derives from social injustice rather than willfully perverse behavior. Of course if Raskol'nikov had targeted someone whose death would have produced meaningful political consequences that also might have made him happy in the knowledge that he wasn't just some poor confused killer. But Dostoevskij won't allow him that. Even a ruthless fanatic like Ne6aev knew enough in his Catechism of a Revolutionist that murder could be justified only of people of power and political importance and then only if "the person's death will necessarily render to the revolutionary cause" (1973: 227). He explicitly excludes ordinary, insignificant people (like pawnbrokers) from his target list of those the revolution must assassinate.

Killing a pawnbroker let alone a horse would be senseless even for Ne6aev, but the sense Dostoevskij repeatedly made of the seemingly senseless crimes that run throughout his fiction is that common sense ought to tell us what socialists deny, that people of their own free will do not want to give up their vicious ways: "I don't want to do good, I want to do evil", Lise says, and Ale~a remarks, "There are moments when people love crime" (708). In Dostoevskij these moments are neither isolated nor insignificant. Michajlovskij was perhaps the first to point out that "cruelty and torture always preoccupied Dostoevskij, and they did so precisely for their attractiveness, for the sensuality which torture seems to contain" (11). But

Dostoevskij 's Tragic Idealism 321

that is not the whole of the story. For writers may very well find certain behavior sensually attractive and may imaginatively represent it that way, even while being equally clear that they find such attraction terribly disturb- ing and the enactment of cruelty utterly abhorrent. That very ambivalence is what makes Raskol'nikov's dream so unsettling. Most men who witness acts of torture, like the beating of the mare, do not always find them hateful, but rather zestful and amusing. (Later in the novel, to illustrate his fondness for children, Svidrigajlov describes a similar scene in which cabaret patrons stand round taking pleasure from seeing a little girl being publicly humiliated; 493-494.) But more disturbing still is the fact that Raskol'nikov can identify with both the peasant who delights in killing an innocent creature with an axe and the child who is horrified by such cruelty and suffering. These same self-lacerations are also tearing Ivan apart. His expressed fondness for children along with his fondness for collecting certain stories about them (newspaper accounts which Dostoevskij had himself collected) suggests that the demon of lust he finds hidden in every man inhabits his own soul as well: "And observe, cruel people, the violent, the rapacious, the Karamazovs are sometimes very fond of children" (282). He is not a pederast like Svidrigajlov or Stavrogin, but a pedophile aware of the hell in his own heart. After all, the reasons Ivan gives for sticking to the children aren't entirely reasonable, but suggest he is motivated by a rather peculiar fondness for them: "in the first place, children can be loved even at close quarters, even when they are ugly (I fancy, though, children are never ugly)", whereas adults are "disgusting and unworthy of love". One "can love one's neighbor in the abstract, or even at a distance, but at close quarters it's almost impossible". Children however are a different matter: "Children while they are quite little [...] are so remote from grown-up people; they are different creatures, as it were, of a different species" (282).

Alega understands exactly what's troubling Ivan. Lise relates to him her dream of watching a child suffer while she eats pineapple compote, and he says to her about Ivan, "perhaps he believes in the pineapple compote himself. He is very ill now" (711).

None of this makes either Ivan or Raskol'nikov a hypocrite, but rather individuals, like their creator, who desire justice even while fully realizing exactly how and why it will be so horribly difficult to end human suffering. Dostoevskij was well aware that the sensual cruelty which is the cause of so much suffering lurked in the hearts even of men like himself who hated cruelty. And if that was the case, how much hope could anyone hold out for improving the human condition?

What utopian socialism could not contend with is the fact that crime, torture, and suffering is not what men want to eliminate from their lives. It is what they desire: "such blows are a real pleasure to me. I cannot do without them. [...] Let her beat me", Marmeladov says of his wife (1965: 41). As Lise

322 Harry White

observes, "everyone loves crime [...]". People "all declare that they hate evil, but secretly they all love it" (708). This realization destroyed Dostoevskij's early radical idealism, but it did not end there. Men's love of crime continued to haunt any later hope he maintained based on his reading of Christianity that beauty or love might transform the world: "[P]aradise on earth [...] is a difficult matter, Prince [My~kin], much more difficult than it appears to your beautiful heart" (1962a: 36l). It could undermine both because they were never really that much different in Dostoevskij's mind, as his contemporary, Konstantin Leont'ev, was the first to point out. He dismissed Dostoevskij's "expectations of earthly love and earthly peace" as deriving from Enlighten- ment utopianism and therefore introducing a "too rosy hue [...] into Christi- anity" which, he rightly contended and perhaps Dostoevskij realized as well, did "not expect anything particularly beneficent from mankind in the future" (1969: 244).

From the Slavophiles to the Narodniki, populism flourished among the Russian intelligentsia. Dostoevskij was a populist to be sure, but his populism was forged as a prisoner among convicts in the House of the Dead, and he realized that what anyone would find when they actually went to the Russian people was not the brotherly love socialists felt was just waiting to be tapped: Were the intelligentsia to go "to some remote place in our own country", Porfirij tells Raskol'nikov, they would not "find anyone there but peasants - real, genuine Russian peasants - and our modern educated Russian would sooner be in jail than live among such foreigners as our peasants" (355; the comment reflects the situation Dostoevskij had earlier on found himself in, a prisoner among peasant convicts who hated members of the educated classes). Nor would they find the simple Christian piety that Tolstoj claimed to find. (The radically different views of Russian peasantry that come from the country's two greatest novelists perhaps resulted from the fact that the Count couldn't figure out that a peasant is not likely to reveal to his master what he truly feels or believes, while the convict mistook the particular criminal class he became intimate with for all genuine Russian peasants.)

Dostoevskij's Russian peasant could be profoundly Christian, but still and all savage and criminal: A "peasant not at all poor [so Dostoevskij tells us he is not motivated by need] [...] took a knife [...] raised his eyes to heaven, crossed himself, and bitterly and silently prayed, 'Lord, forgive me for Christ's sake!' and he cut his friend's throat [...] and took his watch". From this Mygkin concludes what Dostoevskij came to understand among the Russian prisoners, that "the essence of religious feeling [...] has nothing to do with wrongdoing or crime". The "most hardened and unrepentant criminal [...] realizes in his conscience that he has not acted rightly, even though he is unrepentant" (1962a: 239, 358-359). Similar sentiments, expressing a salva- tionist view of Christianity based upon the impossibility of righteousness, are given by Marmeladov who believes he shall be saved because he knows

Dostoevskij's Tragic Idealism 323

himself to be unworthy, and by Dmitrij Karamazov who can pray, "Lord, receive me, with all my lawlessness [...]. I am a wretch, but I love Thee" (40 and 500).

Zosima sums up quite nicely the insight Dostoevskij came to in Omsk prison that would profoundly alter his thinking: "Russian criminals still have faith" (73). The problem is that if prisoners have faith of what good is faith in preventing crime? It does not stop Marmeladov from mining himself and his family, nor Mygkin's pious cutthroat from theft and murder, nor does it hinder Raskol'nikov who knows in his conscience that he is wrong and to no avail prays to God to stop him from killing.

Ivan says, "To my thinking, Christ-like love from men is a miracle impossible on earth" (281). Dostoevskij was careful to limit the expression of such beliefs in his published novel to Ivan's way of thinking, but Ivan was actually reiterating his own concerns. For Dostoevskij himself wrote, "To love your neighbor as yourself, according to Christ's commandment, is im- possible" (1963: 305n.). His own straggle with ways of ending human suffer- ing finally converged in the thoughts and character of Ivan Karamazov. For he is the first to note that the same fundamental problem undermines both socialist blueprints and Christian faith and the first to challenge both for that same reason: neither can keep the beast from his savage ways because brotherly love is not possible for most all men in this life.

Among the peasant convicts, Dostoevskij witnessed men of faith and pride who were still criminals, sometimes of the most brutal sort. So the distinction he maintained throughout his writings was not that Christians were different from nonbelievers by their resistance to savage and criminal behavior, but that Christians like Marmeladov or Dmitrij Karamazov under- stood they were unworthy and in need of salvation whereas the nonbelievers could find in modern doctrines a justification for their criminality. Thus My~kin distinguishes a criminal who "realizes in his conscience that he has not acted rightly" from radical thinkers who "refuse to even consider themselves criminals and think they are in the right" (359). Porfirij says the same about Raskol'nikov: "He has committed a murder, but he still regards himself as an honest man" (468). This refusal to acknowledge one's guilt could lead to "innocent" calls for spilling rivers of blood beyond what any ordinary cutthroat could desire or envision, yet the Christian who "accepts responsibility" (as Tichon put it) may be driven to confess, seek punishment or forgiveness, but he is not distinguished in Dostoevskij by repentance and the elimination of wrongdoing from his life, as Mygkin for one makes clear. What that means is that Christianity with its humble love that Zosima insists upon and the Inquisitor ridicules as ineffective could in fact not stop the beast. The savage, brutal nature of the people made Dostoevskij skeptical of any schemes for social justice, either that proposed by the socialists or even his own hopes, which Mygkin, Alega, and Zosima express, that Christian love

324 Harry White

and forgiveness would transform the world. It might save the exceptional few, even the unworthy among them, but it cannot save the world, which is why Ivan, who must have justice above all, says he returns his ticket to heaven. Dostoevskij depicts Christianity as a hope, a salvation, a justification, but not a morally effective means for transforming the individual and certainly not the world.

The view of humanity Dostoevskij came to in prison stood as a bitter disappointment to any and all hopes he tried to maintain throughout his life for an alleviation of brutality in God's world and in Russia especially. To be sure, his notorious fascination with cruelty reveals a peculiar interest in human perversity, but along with it, there remained an outrage at something peculiar to the Russian psyche which made an end to cruelty and injustice in that country particularly frustrating, a terrible mentality that Gor'kij for one also noted: "I think the Russians have a unique sense of [...] cruelty [o..]. Once can sense a diabolical refinement in Russian cruelty [...]. If such acts of cruelty were the expression of the perverse psychology of a few individuals, they would not concern us here [...]. But I am concerned here with human suffering as a collective entertainment [...]" (quoted in The Black Book, 732- 733). Dostoevskij may have over-generalized from his experiences in prison and from his knowledge of the collective character of the Russian people, but he is not simply throwing the "entertaining" incidents Ivan cites in the faces of social reformers. He is documenting the tragic recognition every lover of suffering humanity like Ivan must face up to and which many socialists with good reason preferred to gloss over.

And yet the ignorance or denial of unwelcome truths is not limited to socialists in Dostoevskij's fiction. It is widespread among his characters and stems from his belief that idealism, whether well founded or not, was absolutely necessary for sustaining individual life and social harmony. Indeed so serious is the need to maintain lost illusions among the people that Ivan has his Grand Inquisitor publicly stand for ideals he does not truly believe in: In giving the people bread, he misrepresents himself to them as one who accepts the rational idealism of the early socialists, but covering all bases, he cloaks it all in miracles, mystery, and authority as well, and knowingly does it falsely in the name of Christ whose teachings he also neither believes in nor practices. As we shall see, the Grand Inquisitor is not the first Dostoev- skij character to hold to beliefs he does not believe in. He would however turn out to be the last.

Dostoevskij's Tragic Idealism 325

III

I have been a child of the age, a child of disbelief and doubt up until now and will be even (I know) to the grave. [...] [My] credo is very simple, here it is: to believe there is nothing more beautiful, more profound, more attractive, more wise, more courageous and more perfect than Christ [...]. Moreover, if someone proved to me that Christ were outside the troth, and it really were that the truth lay outside Christ, I would prefer to remain with Christ rather than with the truth.

(Letter to N.D. Fonvizina, January-February, 1854)

I go on living in spite of logic. (Ivan Karamazov)

Socialism offered solutions to human suffering most of which appeared either unworkable or objectionable, no doubt even to many who continued to pro- pose them, and like Ivan persisted "even i f I were wrong" (291). And yet socialism continued to appeal to so many. That appeal seemed to Dostoevskij to have less to do with what Alega calls the labor question than with a need to fulfill the religious longing of Russia's disillusioned intellectuals and to replace the religious faith they no longer found tenable with a new binding idea. Lebedev, no doubt speaking for Dostoevskij, compares modem prospe- rity with the martyrdoms men formerly suffered for their beliefs: "Show me an idea that binds men together today," he says. "And don' t try to scare me off with your prosperity, your wealth, the rarity of famine. [...] [T]he binding idea does not exist anymore" (1962a: 399-400). Porfirij, also speaking for his creator, recognizes how important ideas are to sustain men like Raskol'nikov: "in my opinion, you're one of those men who [...] would stand and look at his torturers with a smile, provided he had found something to believe in or had found God" (471).

Dostoevskij felt that men and society required idealism and hope because reason and realism alone could not bind them together. The "strength of a great moral idea", he wrote, is that "it cements men in a most solid union [...]" and without it, it would be impossible to "unite men for the attainment of your civic aims" (1979: 1000). Ivan has his Inquisitor express the same view, revealing that for him the power of socialism is not primarily to be found in whatever material benefits it may provide. Its greatest appeal lies in the very ideals socialism stands for, in its ability to sustain men psycho- logically:

The secret of man's being is not only to live but to have something to live for. Without a stable conception of the object of life, man would

326 Harry White

not consent to go on living, and would rather destroy himself than remain on earth, though he had bread in abundance. (302; italics added)

This is quite an admission from one whom many mistake as a mate- rialist demanding that people sacrifice everything "for the sake of food" (Berdyaev 1996: 87). Like his creator, the Inquisitor knows that neither "man nor nation can exist without a sublime idea" (1979: 538-540), and that is why he not only dispenses bread, but tells people he dispenses it in the name of Christ. He understands that "[s]ocialism has been embraced not only by those who are hungry but also by those who are thirsting for a spiritual life" (1968: 201). That is why Stepan Verchovenskij interprets the enthusiasm young men like his son have for socialism as only secondarily concerned with economic issues: "It's not the practical aspects of socialism that fascinate them but its emotional appeal - its idealism - what we may call its mystical religious

aspect" (1962b: 75). And the son pretty much agrees: "we have a new reli- gion to replace the old one; that's why we have so many volunteers and are able to operate on a grand scale" (388). As Raskol'nikov does in his own way: The writer of articles on advanced ideas, the self-proclaimed benefactor of humanity buries the pawnbroker's loot and never returns to it. Mygkin, though a critic of and not a believer in socialism, nevertheless presents the same analysis: socialism seeks "to replace the lost moral power of religion, to quench the spiritual thirst of lost humanity" (561).

Dostoevskij attacked socialism not as an unacceptable economic alternative, but as a competing religious ideology. For he contended that Rus- sian socialism did not represent some new socio-economic theory, but was "an offspring of Catholicism and the essential Catholic idea!" (My~kin in 1962a: 561). It was the reappearance of the old idea of the "compulsory communion of mankind [...] which dates back to ancient Rome and which was fully conserved in Catholicism" (1979: 563). It fulfilled the personal and political need of Russia's youth for genuine faith: "Isn't socialism taking the place of Christianity? Isn't it the new Christianity [...]. It is precisely the same Christianity, only without God" (1968: 406). Socialism amounted to a pre- tender religion that readily appealed to men of conscience and compassion who longed above all for a novel modern ideology that would bind men harmoniously together.

And yet the easy attraction socialism has for so many of his characters might have had less to do with the content of socialist thought than with Dostoevskij's understanding of the character of the Russian people, of their profound need for passionate belief which made them willing to embrace almost any kind of idealism. Satov who "radically altered his former socialist convictions and jumped to the other extreme", represents "one of those Russian idealists who, once struck by some overwhelming idea, becomes

Dostoevskij's Tragic Idealism 327

obsessed by it, sometimes for the rest of his life. He cannot ever really grasp it, but he believes in it passionately" (32).