Chopin's Fourth Ballade as Musical Narrative

-

Upload

abelsanchezaguilera -

Category

Documents

-

view

30 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Chopin's Fourth Ballade as Musical Narrative

-

Society for Music Theory

Chopin's Fourth Ballade as Musical NarrativeAuthor(s): Michael KleinSource: Music Theory Spectrum, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Spring, 2004), pp. 23-55Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society for Music TheoryStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4488727Accessed: 25/07/2010 22:26

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available athttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unlessyou have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and youmay use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained athttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucal.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

University of California Press and Society for Music Theory are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserveand extend access to Music Theory Spectrum.

http://www.jstor.org

-

Chopin's Fourth Ballade as Musical Narrative MICHAEL KLEIN

This article argues a perspective of musical narrative as an emplotment of expressive states rather than a sequence of actors and their actions, and offers a narrative analysis of Chopin's Fourth Ballade. The analysis embraces both hermeneutic and semiotic concerns by examining what this music means and how it signifies that meaning, and proposes a reading of the Fourth Ballade that situates it intertextually.

I begin with a discussion of mimetic and diegetic properties of music and consider ways in which Chopin's ballades signify time, particularly the past tense often deemed crucial to narrative forms. I then expand Edward T. Cone's notion of apotheosis, showing how Chopin's larger works depend upon an emotionally transformed recapitulation of an interior theme that often represents a desired emotional state. After applying these theories of apotheosis and temporality to the Fourth Ballade, I conclude with a discussion of pastoral literary narratives and the ways they eluci- date the expressive logic of this work.

. it does not seem at all exaggerated to view humans as narrative ani- mals, as homo fabulans-the tellers and interpreters of narrative" (Mark Currie). ~411 that we don't know is astonishing. Even more astonishing is whatpasses

for knowing" (Philip Roth). Regarding the apotheosis of Chopin's Fourth Ballade: 4nyone looking for 'narrative' structure in music would be hard put to find a more moving ex- ample, or one that is more beautifully composed" (Carl Schachter).'

WHAT KIND OF NARRATIVE?

We tell stories. When we tell stories about stories, it is a commonplace to reaffirm that they can be about anything in any medium. Perhaps because we are storytellers, an ever

growing array of publications devotes attention to narrativity in music, yet despite this work, there are those who argue that music cannot narrate. Such arguments tend to focus on what Jean-Jacques Nattiez calls the trace, or immanent level of analysis, contending that there is nothing in the music per se that allows it to point unambiguously to actions or charac- ters.2 As if anticipating such objections, Theodor Adorno responds in advance, "It is not that music wants to narrate, but that the composer wants to make music in the way that others narrate."3 From the perspective of reader-response criticism, we might willfully misread Adorno, adding that it

*I wish to thank Sumanth Gopinath, Martha Hyde, and Patrick McCreless for their insightful comments on early versions of this article. Citations for the three epigraphs are Currie 1998, 2; Roth 2000, 209; and Schachter 1989, 190.

2 This is Nattiez's strategy in concluding that "narrative, strictly speak- ing, is not in the music, but in the plot imagined and constructed by the lis- teners from functional objects" (Nattiez 1990a, 249). Similar arguments, though, could be made about many types of narratives. Nattiez rightly observes, for example, that historical facts are not a narrative until we arrange them into a plot of causality (Ibid., 245).

3 Adorno 1992, 62. In fairness, Adorno's statement is directed at the music of Mahler and makes no sweeping commitment to all of music.

23

-

24 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

is not that music wants to narrate, but that we want to hear music in the ways that we hear narration.4 We want to hear stories.

To structure these perspectives, we can borrow Nattiez's semiotic tripartition and position musical narrative on three levels.5 On the poietic level, a composer may wish to write music that narrates, focusing on musical attributes that sig- nal narration. On the immanent level, the music may have such attributes, regardless of whether the composer intends to write narrative music. On the esthesic level, a listener may want to hear music as a narration, regardless of the com- poser's intent.6 Narrative on the poietic level is a matter for

biography and history. Narrative on the immanent level is a matter for the conjectures of theory. And narrative on the esthesic level is a matter for probing the ways that we read texts.

Objections to the conception of music as narrative tend to focus on two arguments: music is incapable of representing the actors and actions deemed necessary for narrative, and/or music fails to project a narrator, who can tell the tale in the past tense. Both arguments rest on a mimesis/diegesis oppo- sition that has been central to western poetics since Plato.7 Though the history of these two terms is complex, and their use in literary theory far from stable even today, we can take them to mean the difference between showing (mimesis) and telling (diegesis). Under these definitions, music, along with drama and dance, is a mimetic art. A small irony in ar- guments against music as narrative is that on the one hand music's limited capacity to represent actions and actors is a failure of mimesis, yet on the other hand music's inability to project a narrator is a failure of diegesis. Thus music exists in a shadow realm between mimesis and diegesis.

Roger Scruton untangles the issues around music's ability to represent actors and actions.8 Although Scruton ulti- mately rejects music as a representational art, he admits its capacity to imitate the sounds of a limited number of real world objects. Crucial, though, is his observation that when

4 Because even the most expository writing necessarily leaves out infor- mation crucial for an understanding of the text, reader-response criti- cism broadly concerns itself with the work that readers must do in in- terpreting the text. Important contributions to this area include Eco 1981, Fish 1980, Iser 1974, and Nardocchio 1992.

5 Nattiez 1990b. Nattiez (1990a) also uses the tripartition in his critique of narrativity in music. Basically, though, since Nattiez contends that music has no intrinsic ability to narrate, interpretive acts that narra- tivize music remain on the poietic and esthesic levels for him.

6 The word attribute in these descriptions refers to Cook 2001. Cook contends that when drawing meaning from music, listeners attend to those attributes that will support that meaning. Because listeners natu- rally focus on only a few of music's potentially unlimited attributes, dif- ferent listeners may arrive at wildly different meanings for the same music. Cook may be using the term attribute as opposed to structure in order to allow for listening strategies that focus on surface events in the music without excluding the possibility of focusing on deeper-level structures. I use the term here with the same motivation. Like the study of narrative, Cook's theory might be structured by Nattiez's tripartition, where the attributes are the immanent level and the listener is the es- thesic level (Cook never discusses the composer, though it would be easy enough to include a poietic level in his theory). Troublesome in Cook's theory, Nattiez's tripartition, and my borrowing of this work is the conception that attributes (and structures) are somehow in the music. It may just as well be the case that we project these attributes and structures on the music, so that the immanent level collapses into the esthesic.

7 The history of the terms diegesis and mimesis begins with Book III of The Republic, where Plato uses diegesis to mean speech that comes from the author/narrator and mimesis to mean speech that comes from an- other character (Plato made no distinction between the narrator and the author). Aristotle complicates matters in his Poetics, where mimesis includes not only speech from another character, but any imitation or miming of action. Mimesis occurs not only when characters speak in drama, or epic poetry, but also when dancers dance. Roger Scruton is quick to point out that the music Aristotle had in mind was mimetic because it was danced, sung, or marched to (Scruton 1997, 118). For an account of the varying meanings that have attached themselves to die- gesis and mimesis, see Hawthorn 1994, 42-5.

8 Scruton 1997, 118-39.

-

CHOPIN S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 25

music imitates birdsong, for example, "the musical line is not about the birdsong . . ."9 Raymond Monelle clarifies this point semiotically, arguing that when music imitates the sound of a bird, that imitation is an iconic sign; but the bird that music imitates is indexical of (points to) what are often the real signifiers of the music: spring, nature, joy.10 This in- terpretation puts in a new light Scruton's claim that music narrates not the actions of a bird but "the birdlover's emotion as he is carried away by the song.""l Music may make ges- tures of imitation, but it soon returns to itself, carried away with the emotional responses to the object of imitation. Mu- sic "appropriates being."12 From this perspective, we see how rightly Gregory Karl argues that limiting narrative to extra- musical reference seems a naive understanding both of what a narrative is and of what claims people make when they hear music as narrative.13 The impulse to narrativize music is a motivation to find the expressive logic within both the individual composition and the repertoire that supports it.

The distinction between uncovering an expressive logic and mapping a story onto the music is critical for an under- standing of the narratives that have accrued around Chopin's Ballades, of which the Fourth will soon be the focus of this article. Early in their reception history, these works were thought to be inspired by the poems of Adam Mickiewicz, with inconclusive evidence linking the Second Ballade in particular to the poem Swite', in which a Polish pastoral setting suffers the invasion of Russian soldiers.14 If Chopin

did create a one-to-one correspondence between actions in Mickiewicz's poem and musical attributes in the Second Ballade, we may never know, because he rarely offered pro- grams to aid interpretation of his works. The search for such a correspondence on poietic and immanent levels, though, seems to match that naive understanding of narrative to which Karl and others object. Knowing that the presto con fuoco sections of the Second Ballade portray Russian soldiers violating the Polish countryside may be of historical interest, but calling this portrayal the narrative of the ballade misun- derstands what musical narrative is. Music may have a lim- ited capacity to signify the story of Swited but it is adept at signifying expressive states whose arrangement follows a narrative logic. When we hear the sudden explosive expres- sions of the first presto con fuoco section in the Second Ballade, we may well wonder what motivates this expression, whether it will return intact or transformed, and why it is placed where it is. These are narrative questions that can be answered with recourse to narrative theory. The distinction between an extra-musical narrative and an expressive one also aids in understanding how Chopin might have had Switez in mind when composing the Second Ballade, while remaining committed to the idea of absolute music.15

Perhaps the most famous objection that music has no narrator is Carolyn Abbate's claim that music has "no ability to posit a narrating survivor of the tale who speaks of it in

9 Ibid., 127. io Monelle 2000, 19. Hi Scruton 1997, 129. 12 Adorno 1992, 71. 13 Karl 1997, 13-4. 14 Samson 1992, 16. Jeffrey Kallberg (1996, 190-4), drawing from corre-

spondence among Chopin's publishers, documents early attempts to call the Second Ballade a "Ballade polonaise" or a "Ballade des Palerins" (where the word pilgrims refers to Polish emigres). Kallberg finds no conclusive evidence to determine whether these titles came from Chopin or his publishers.

15 Following Hanslick's famous dictum that "Der Inhalt der Musik sind t6nend bewegte Formen" ("The contents of music are tonally moving forms"), absolute music is often taken today to mean instrumental music whose true content is a formal/structural one (Hanslick [1854] 1966, 59). Carl Dahlhaus (1989) shows, however, that historically the concept of absolute music had a wide range of meanings-from music without words, to music that could express the absolute (in a German Idealist context), to music whose sole content was form. As such, Chopin's commitment to absolute music may have been closer to the idea that instrumental music could relate an expressive content without recourse to words or programs. See also Chua 1999.

-

26 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

the past tense."16 Lacking a narrator, the mark of diegesis, music can only present actions as they unfold in the present. Since music lacks a past tense, it cannot properly be called narrative according to a tradition of poetics reaching back to Aristotle. Recent work on narrative, though, has shown the difficulty of maintaining the distinction between mimesis and diegesis. J. Hillis Miller, for example, argues that Sopho- cles' Oedipus Rex fails as an example of mimesis, because the action in the play is "made up almost exclusively of people standing around talking or chanting."17 Paul Cobley argues that a telling is also a showing, because the creator of a nar- rative in any medium chooses to reveal some events, while hiding others. Accordingly, Cobley defines narrative as the "showing or telling of these events and the mode selected for that to take place."18 Under this definition, music's failure of the diegesis test ceases to impact its status as a narrative artform.

Some may find in such arguments the sophistry of a post- modern thought content to tear down distinctions of any kind. But long before the question of music as narrative began to focus on the absence of a narrator in music, Edward Cone wrote of that comfortable illusion that we hear the ex- pressive states of music as if projected from a subject, a con- sciousness.19 In search of that consciousness, Cone posits a persona, virtual in the case of instrumental music, which acts

as the narrating presence mediating the musical action be- fore us. In Cone's conception, music may be peopled by the expressive states of multiple characters that seem to speak for themselves. Implicit in such music, as in a novel written in the third person, is that a single consciousness narrates the expressive states of these various musical characters. Cone, and later Scruton and Monelle, also warns against confusing the composer with the musical persona.20 Such confusion may be viewed as a contributing factor in how the music-as- meaning game has been played. In regard to Chopin's bal- lades, for example, it was a common belief in the nineteenth century that since Chopin was a Polish patriot, the ballades must be his telling of events in Poland's tragic history. More damaging was the idea that Chopin's physical weakness somehow inscribed itself in his music. Alternate readings of much of his music, though, would have to conclude that Chopin could create musical personae of great physical, moral, and psychological strength.21

My narrative analysis of Chopin's Fourth Ballade assumes the existence of a musical persona who is the implicit narra- tor of a tale, and demonstrates that Chopin makes more explicit this surviving narrator with an evocation of the past. Following the work of Cone (1974), Robert Hatten (1994), Karl (1997), and Fred Maus (1988), among others, the type of narrative explored in this analysis is an expressive one. Instead of mapping a particular story of actors and actions onto the music, I shall describe expressive states evoked by 16 Abbate 1989, 230. Karl also considers Abbate's claim, agreeing that

music has no narrative past tense, but arguing that our experience of music is closer to a narrative (diegetic) one than a dramatic (mimetic) one. See Karl 1991 and 1997.

17 Miller 1998, 10. The irony of Miller's observation is that Aristotle uses Oedipus Rex as the model for tragedy; yet a close reading reveals that this play fails in almost all of the characteristics that Aristotle lists for a classic tragedy.

18 Cobley 2001, 6. 19 Cone 1974. Drawing upon recent literary criticism, Monelle recon-

siders Cone's notion of the musical persona, concluding that more emphasis should be placed on the performer, who acts as reader and impersonator of the composer's voice (Monelle 2000, 165-9).

20 Monelle 2000, 158-65. Scruton calls the idea that a composer's state of mind is somehow in the music the "biography theory," which is "so evi- dently erroneous that it would be pointless to refute ..." (Scruton 1997, 144).

21 On the tendency in the nineteenth century to associate Chopin and his music with weakness, effeminacy, and the otherworldly, see Kallberg's finely nuanced "Small Fairy Voices," in Kallberg 1996, 62-86. In "Harmony of the Tea Table," Kallberg offers a gendered account of Chopin's music, including analysis of a later trend to deflect tropes around Chopin's effeminacy by cultivating descriptions of manly vigor in his music (Ibid., 42-5).

-

CHOPIN S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 27

this music and the ways that their unfolding implies a narra- tive. The term expressive covers primarily affective meanings (sadness, apprehension, etc.) but may also cover dramatic sit- uations or ideas (outburst, transcendence, etc.). The analysis of these expressive states will be both hermeneutic and semi- otic: hermeneutic, because it focuses on what this music means; semiotic, because it is concerned with how this music means.

The theories that support this narrative analysis are wide ranging. Following Hatten, I begin with analysis of the Fourth Ballade's expressive genre, the broad topical field that organizes the expressive states of the work.22 Jim Samson ar- gues that although Chopin wrote only four ballades, they still represent a separate genre.23 As such, I believe that we must read the Fourth Ballade intertextually with the other three, with particular emphasis on some astonishing points of contact between it and the First Ballade.24 Broadening

this intertextual perspective into Chopin's other larger forms reveals an emphasis on apotheosis in his late music, and I shall devote space to the narrative implications of this con- cept. From analysis of the expressive genre, I turn to a con- sideration of temporality in the ballades and refocus a theory of lyric and narrative time outlined by Monelle in order to demonstrate how we can hear significations of the past and present tenses. Equipped with this theory, I hope to show the temporal logic that leads the narrative action to the apotheosis. Finally, I take up pastoral as a literary genre and suggest ways in which the affective trajectory of the Fourth Ballade mirrors conventions of pastoral literary-narratives.

WHOSE NARRATIVE?

My analysis makes generous use of Hatten's semiotic theory of markedness and correlation, in which an opposi- tion in the music (major/minor, for example) correlates to extra-musical meaning (non-tragic/tragic).25 Though Hatten allies his project with Peircean semiotics, his use of opposi- tions may be read within Ferdinand de Saussure's celebrated tenet that meaning is difference, leaving no positive terms for signs.26 In music, a minor key has no power to signify the tragic except within a field of difference that opposes it to a major key. Further, it is within a cultural/historical context that a listener competent with the repertoire of art music hears a minor key as signifying a tragic affect. Even within this convention of interpretation, though, a listener may find other signs in the music that override the correlation between major/minor and tragic/non-tragic. Conventions of

22 Hatten 1994, 67-90. 23 Samson 1992, 71. Kallberg points out that until recently genre has been

under-theorized in English publications, which often rely too heavily on immanent characteristics (Kallberg 1996, 5, 231-2). The problem of genre is underscored in Chopin's works, where intertextual references to multiple styles and formal types within a single composition make for difficult classifications. In considering the problem of genre in Chopin, both Samson and Kallberg have made contributions to our understand- ing of that term. See Kallberg 1996, 3-29; and Samson 1989. Samson's use of the word genre in regard to the ballades may be read as a formal/ stylistic category that includes listener expectations in regard to affect. By contrast, Hatten's expressive genres can cut across formal ones. Any number of different formal genres, for example, may support an expres- sive genre that moves through a heroic topic from tragic to transcen- dent states.

24 Eero Tarasti (1994, 178-9) argues that we must read the narrative grammar of a work intertextually with the grammars of other works by the same composer. Tarasti's argument comes near the end of a highly detailed analysis of Chopin's First Ballade, which relies on A. J. Greimas's rules of narrative grammar to articulate five modalities of the ballade ("Will," "Know," "Can," "Must," and "Believe"). Tarasti's analysis has a welcome phenomenological character, as he explores, for

example, how a listener might doubt the "truth" of the opening waltz because it is displaced from its normative genre. Though the analysis is filled with insights, an urge to give values to each of the modalities and to go sequentially through the sections of the ballade a number of times results in a bloodless quality to the description of the narrative.

25 Hatten 1994. 26 Saussure 1983, 118.

-

28 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

interpretation, or what some would call codes, may be moti- vated by appeals to metaphor, icon, or index, but ultimately they are arbitrary.27 In addition, codes are fluid and combi- natorial, allowing for a range of interpretation as the listener apprehends the interaction of signs. Finally, oppositions abound in music as in all sign systems, and seeking them in support of an interpretation can quickly devolve from serious pursuit of the foundations of meaning to the less serious en- tertainment of a parlor game. It would be a mistake in light of the foregoing to claim that an opposition within a cultural context always correlates to a single meaning. It would be a mistake as well to conclude that since we find an opposition in the music that supports a meaning, we have somehow proved an interpretation.

Realizing that a conventional code correlates a musical opposition to an extra-musical meaning would seem to make imperative a discovery of just what these codes are, how they develop, and how they change. Thus the hermeneutics of re- covery, a motivation to rediscover how people once under- stood an artwork by reconstructing its original context, runs deeply in the study of musical meaning. Hatten, for example, writes in his Musical Meaning in Beethoven: I am developing a modern theory of meaning compatible with Peircean semiotic theory, and applying that theory to the historical reconstruc- tion of an interpretive competency adequate to the understanding of Beethoven's works in his time (3). In the first chapter, Hatten makes a gambit that exposes the difficulties involved in reconstructing that interpretive com- petency. The chapter presents an interpretation of the third

movement of Beethoven's Hammerklavier, after which Hatten writes: If the interpretive journey has been convincing to this point, one reason is that all the outstanding or salient structural events have been related to an overarching hypothesis ... (28). To which we might ask: convincing to whom? Surely Hatten means convincing to us, his readers. And his interpretation is convincing, even brilliant. But lacking the historical inter- pretive competency that Hatten proposes to reconstruct, his readers are in no historical position to judge this interpretive journey. Of course, historical documents give us an idea, refracted through another interpretation, of how listeners understood Beethoven's music in his time. Hatten could be asking if we find his interpretive journey to have convincing resonance with an understanding culled from these docu- ments. I suspect, though, that Hatten wishes the interpreta- tion to be convincing both to us and to our notions of how Beethoven's contemporaries heard his music. We can hear the music this way, and we can believe that Beethoven's con- temporaries also heard it this way.

It is not my intent to be unfairly severe in reading Hatten's text, especially since I depend upon his remarkable project. Instead, I wish to respond to the announced goal of his work by wondering why we so willingly divest our inter- pretive energies into reviving the unknown dead. Under- standing a text's original historical/cultural context is both an end in itself and a means of determining where we are in relation to where we have been. Scruton suggests another motivation when he compares artistic contemplation to reli- gious ritual, reasoning that changes in either disturb us be- cause they deny a connection between the living and the dead, implying that one day we too will be cast aside.28 Thus an ethical dimension comes into play in acts of interpreta- tion. For this discussion, though, I wish to focus on the no- tion that recovering the competency of the past can be an at-

27 For an introduction to semiotic codes, see Chandler 2002. More de- tailed discussions of codes may be found in Barthes 1974, Culler 1981, and Eco 1976. Nattiez (1990b, 16-28) is critical of Eco's use of codes as a model for meaning, finding that they quickly proliferate to an un- manageable number as we attempt to map signifieds onto signifiers. Nattiez is in agreement with Eco's position that any description of codes must allow for the possibility that the producer and receiver of a message may not share the same code for its interpretation. 28 Scruton 1997, 461.

-

CHOPIN S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 29

tempt to hypostatize interpretation. Implicit is the fear that unmitigated interpretation has already been released on mu- sical texts, leading people to make claims that ought not pass for knowledge. Often grounding this fear are beliefs in uni- versals, in the univocal nature of the artwork, in the past as more stable than the chaotic present, and in our ancestors as more capable than we.29 Jonathan Culler reminds us of an assumption held even among critics versed in semiotics that works of art have a meaning. Such a view implies that mean- ing is somehow inscribed into the fabric of the text itself, and the critic competent in interpretative strategies simply draws it out.30 Culler offers a sane response to the fear that interpretations have become unlimited when he argues that the liveliness of literary (musicological) institutions depends on the dual facts that we can never settle matters of inter- pretation and that we must find supporting evidence for interpretation.31 Because artworks resist interpretation, we are left with the same task that Hatten sets for himself: to convince our readers that they could hear the music in a way consistent with the interpretation at hand.

To be clear, my position is that although uncovering the contexts and interpretive strategies of the past is a viable pursuit, an impulse to defer to the dead as a means of discov-

ering univocal meaning brings in assumptions about texts with which I do not find myself in accord. Significance is not inscribed into the text but arises as the result of an act of interpretation. The text is a nexus around which interpretive acts take place, among which are surely notions about histor- ical context and the conventions of linking signs. In laying out an expressive narrative for Chopin's Fourth Ballade, though I am concerned with an understanding of Chopin's time, I shall make no claims about reconstructing a compe- tency held by Chopin and his contemporaries. Instead, I shall focus on what the Fourth Ballade might mean to us today.

The methodology of this narrative interpretation involves intertextuality, a conception of the text as the site of allusions, citations, and transformations of other texts. Under the broad definition used in this article, a text is any cultural artifact: a work of art, a piece of music, a novel, a scholarly publication, an historical document, a calendar, or even that composer whom we imagine, whose name is the same as the historical figure called "Chopin."32 Space prohibits a thorough account of intertextuality here except to say that most writings on the topic rehearse an argument in which intertextuality is both a condition of meaning and a threat to it. As readers, we bring other texts to our interpretation of a single text, but since the number and type of these texts are potentially unlimited, questions arise regarding the possibility of establishing stable 29 I do not wish to imply that Hatten's position involves such beliefs.

Particularly in his "Grounding Interpretation," Hatten (1996) appeals to the ways that semiotics and stylistic competency support interpreta- tion, which is open to a range of possibilities.

30 Michael Riffaterre (1978), for example, proposes a theory by which every poem is the transformation of a single matrix, a word or sentence that is the unifying semiotic sign of the poem. Riffaterre's theory allows only one possible matrix for each poem, and much of his writing is de- voted to pointing out errors in other critics' interpretations, based on the hypothesis that they have uncovered the wrong matrix. For Riffaterre the text controls interpretation, an idea that is striking in light of his otherwise nuanced use of intertextuality, which is often viewed as a destabilizing factor in interpreting texts. For a review of Riffaterre's work, see Culler 1981, 80-99.

31 Culler 1997, 61-2.

32 Regarding intertextuality, the literature is too vast for an exhaustive ci- tation, though a fine introduction to its implications and uses in literary criticism is Jay Clayton and Eric Rothstein's "Figures in the Corpus" (1991). Definitions of the term vary widely in the literature, and the one offered here is indebted both to Julia Kristeva, who coined the word intertextualite as a "permutation of texts," and to Roland Barthes, who conflates text with intertext, defining them as a "new tissue of past citations" where "bits of code, formulae, rhythmic models, fragments of social language, etc. pass into the text and are redistributed within it, for there is always language before and around the text" (Kristeva 1980, 36; Barthes 1981, 39). Regarding the notion of the author as another text, imagined by the reader, see Barthes 1977 and Foucault 1977.

-

30 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

interpretations. Intertextuality interacts with the semiotic oppositions we analyze in support of extra-musical meaning. The critic has an intuition about a meaning or range of meanings for a text or a passage from a text and considers the oppositions in the text that support this meaning. The critic forms an intertext with another cultural artifact, con- firming or denying the interpretation. Alternatively, the critic organizes as an opposition an attribute of a musical passage but lacks an immediate intuition about its meaning. The critic then hypothesizes meanings set as oppositions and forms an intertext with other cultural artifacts, confirm- ing or denying those meanings. Broadly, the critic starts with an intuition about meaning and moves to a consideration of the structural, cultural conditions that underpin that mean- ing, or the critic starts with those structural, cultural condi- tions and moves to a consideration of what meaning they might underpin. Both processes may move from part to whole, or from whole to part of the text.33

APOTHEOSIS

Since each of the four ballades presents two or more themes and key areas with a reprise of at least one theme, published analyses tend to compare these works to sonata forms.34 Such comparisons can be problematic because the

reprise of the second theme in the ballades may appear away from the home key, in addition to which the structural dom- inants for the First, Second, and Fourth Ballades occur after the recapitulation, suggesting that if Chopin were making a response to sonata form, it was an individual and original one.35 Although comparison among the ballades reveals some similarities in form, no single model governs the entire set. The First and Fourth Ballades, though, share striking features of form and expressive content. Example 1 presents in tabular form an outline of the themes and key areas of these two ballades. Arrows in the example show modulatory sections. The terms Gang, lyric, and narrative will be defined shortly. Finally, the bottom row in these tables lists topical features. Example 1 provides a frame of reference only and should not be taken to represent an incontestable formal structure.

Determining the boundaries of the exposition is unprob- lematic for both ballades, since they present two themes in contrasting keys. Points of recapitulation are more question- able, since both ballades bring back the second theme in the submediant, and the First Ballade reprises the themes in re- verse order. Chopin sets the first theme of both ballades as a waltz. In addition, both contain a second, more virtuosic and celebratory waltz in a development section.36 As for dra- matic affect, both ballades conclude with fiery codas, sug- gesting a tragic end. I hear topics for sighing and death in the left hand of the coda of the Fourth Ballade, which sup- port this interpretation. But the unbridled virtuosity of this coda, coupled with powerful closing chords, might be read as defiant, or as a sign of heroic struggle. Under such a reading, the listener might make an intertextual connection between

33 The reader may well feel discomfort at such an undertaking, and might wonder how to evaluate the following claims about Chopin's Fourth Ballade. For now it may suffice to say that this interpretation is best read as one among many.

34 Samson argues that despite departures from sonata form, "we need to recognize it as the essential reference point for all four ballades" (Samson 1992, 45). Not all published analyses have made the sonata comparison. Heinrich Schenker views the First Ballade as an extended three-part form (Schenker 1979, 133 and Fig. 153/1). Douglass Green calls the First Ballade a unique form in five sections (Green 1979, 304- 6). Alan Rawsthorne admits resemblances between the ballade's formal structures and sonata form, yet he insists that it is foolish to relate Chopin's ballades to sonata form in any way (Rawsthorne 1966, 45).

35 Samson discusses Chopin's different treatments of the dominant at foreground and middleground levels in 1985, 213-4, and 1992, 78-81.

36 Even the term development should be taken loosely. Karol Berger has argued convincingly that Chopin's development of themes in the First Ballade does "not quite live up to the Classical image of thematic work- ing" (Berger 1996, 56).

-

CHOPIN S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 31

First Ballade Exposition? - - Development? - )- Recap.?

Mm. 1-7 8-36 36-67 67-82 82-94 94-105 106-125 126-137 138-150 150-166 166-180 180-194 194-208 208-264 Intro Theme 1 Gang Theme 2a Theme 2b Theme 1 Theme 2a Gang Theme 3 Gang Theme 2a Theme 2b Theme 1 Coda

g g - Eb a A V/E6 Eb g Lyric Lyric Narrative Lyric Lyric Lyric Lyric Narrative Lyric Narrative Lyric Lyric Lyric? Narrative

Mythic Waltz "Horn" Berceuse Apotheosis Virtuouso Tragic ] Apotheosis Valedictory Announce- intro ("Public") Trans. ] Tragic

ment Waltz Polonaise

Fourth Ballade Exposition? I - Development? - j j Recap.?

Mm. 1-7 8-22 23-37 38-57 58-71 71-80 80-99 100-112 112-128 129-134 135-151 152-168 169-210 211-239 Intro. Theme 1 Var. 1 Interruption Var. 2 Gang Theme 2 Gang Theme 3 Intro. Var. 3 Var. 4 Theme 2 Coda Motto (Th. 1) (Th. 1) Motto (Th. 1) (Th. 1)

C f Gb-bb-Gb f -+ B g-- Ab A d-+V/f f Db--V/f f

Lyric Lyric Lyric Lyric Lyric to Narrative Lyric Narrative Lyric to Lyric Lyric Lyric to Narrative Narrative Narrative Narrative Narrative

Waltz Sublime Waltz Pastorale Virtuouso Canon Waltz to Apotheosis Tragic ("Public") Learned Apotheosis?

Waltz Style

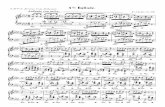

EXAMPLE I. Structural and topicalfeatures of Chopin's First and Fourth Ballades.

the final passages of the Fourth Ballade and those of Beetho- ven's Appassionata sonata, where heroic defiance and struggle are a plausible interpretation.

Rather than view these ballades as unruly sonatas, it seems more productive to discover their formal/expressive logic. This logic differs from that of a Beethovenian para- digm in which the tensions of the work find release in the dual return of the tonic and the first theme at the point of recapitulation, and in which the return of the second theme in the tonic resolves the structural harmonic dissonance set up in the exposition. In Chopin's larger works, including the ballades, formal/expressive logic is directed towards what

Cone calls apotheosis, "a special kind of recapitulation that re- veals unexpected harmonic richness and textual excitement in a theme previously presented with a deliberately restricted harmonization and a relatively drab accompaniment."37 Examples 2 and 3 reproduce the second theme of the Fourth

37 Cone 1968, 84. Following Cone's lead, Kallberg describes the expres- sive sweep of Chopin's Polonaise-Fantasy, op. 61 in terms of apotheosis (Kallberg 1996, 117). Samson discusses Chopin's music in similar terms (Samson 1992, 75-6, 84). In an otherwise positive review of Samson's earlier The Music of Chopin (1985), Schachter takes Samson to task for a failure to develop Cone's idea of apotheosis (Schachter 1989, 189-90). Schachter posits the overtures of Weber as the immediate

-

32 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

Ballade and its apotheosis. Commentary in the examples refers to a later discussion. Though it is arguable whether the initial appearance of the second theme shown in Example 2 is restricted in harmonization, there can be no doubt that the texture of its accompaniment is greatly expanded in the apotheosis. Further, the apotheosis forms a climax to the Fourth Ballade that extends through to the last measures of the coda. Cone considers the apotheosis in Chopin to be an early version of what will become thematic transformation in Liszt and Wagner, where a poietic impulse to narrativize music makes critical the desire to avoid exact repetition of a theme. If characters in a narrative change over time, then the themes that represent them or their emotional states must change over time as well. Thus apotheosis is both a structural and expressive transformation of a theme.

This expressive transformation gives vital clues to what Hatten calls the expressive genre of a piece.38 A familiar ex- pressive genre is the tragic-to-triumphant one that arches across the movements of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. In Chopin's music, variables that aid in determining the expres- sive genre include the theme chosen for apotheosis, the key of the apotheosis relative to the tonic, and the placement of the structural dominant with respect to the apotheosis. In Chopin's larger works, an interior theme tends to be a noc- turne or pastorale, whose simple accompaniment imbues it with potential for apotheosis. Often the initial appearance of such a theme is in a chorale texture, whose religious impli- cations underscore a desired emotional state. We might identify the nocturne as a metaphor for Chopin's own sub- jectivity, as if he has written himself into the narrative as a musical persona; a broader perspective might see these inter- nal themes as metaphors for otherness.39 A gendered reading

might view these themes as signifying the feminine and the apotheosis of these themes as an exaltation of feminine musical discourse (though defined by a man). However we interpret the theme marked for apotheosis, we can hear it as signifying a difference from the ontological reality of the surrounding musical material: it is past as opposed to pres- ent, interior as opposed to exterior, there as opposed to here, feminine as opposed to masculine, night as opposed to day. In the present discussion, I shall settle upon the opposition of rural versus urban, largely because the theme chosen for apotheosis is a pastorale. In opposition to the pastorale is the first theme, a waltz, which I take to be a synecdoche for the salons of nineteenth-century urban life. Rural and urban themes, in this case also tied to lower and upper classes, are common to literary pastorals, which I shall take up later.

A prime example of apotheosis appears just past the mid- point of the Polonaise-Fantasy, op. 61, where a new theme appears in the flat mediant; the theme is introduced by a chorale texture before a nocturnal accompaniment takes over. Both this theme and a counter-theme drawn from its accompaniment return in an apotheosis at the end of the work. Chopin's penchant for placing expressive weight on a theme other than the first is evident as well in his Second and Third Sonatas. Though neither work contains an apoth- eosis, both have a nocturnal second theme that also ushers in a recapitulation, lacking a reprise of a more dramatic first theme. In addition, the second theme of the Second Sonata first appears in a chorale texture before receiving a more elaborate treatment. Interior themes that are lyrical repre- sentations of desired emotional states appear in the Bar- carolle op. 60, and the First, Third, and Fourth Ballades, in addition to the works mentioned. A notable exception is the Second Ballade, whose first theme is a pastorale, and

ancestors to Chopin's apotheoses, though he admits that the concept gains potency in Chopin's music.

38 Hatten 1994, 67-90. 39 For a discussion of the gendering of the nocturne, see Kallberg's "The

Harmony of the Tea Table" (Kallberg 1996, 30-61). Wayne Petty offers

a reading of nocturnal themes within Chopin's larger forms as the com- poser's means of asserting identity in the face of the anxiety of influence (Petty 1999, 286).

-

CHOPIN S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 33

Sequence before theme (proper) begins- - - Pastoral Theme dolce

79 a tempo

"frozen" VII - altered NCT

CT diminished 7ths IV falls to ii

L L I

6-5 - - - - - - Ascending 6-5 Sequence - IV sustained - - - Striving

EXAMPLE 2. Second theme of Chopin's Fourth Ballade.

whose second theme has a stormy character that shatters all calm.40

Regarding the key of the apotheosis, when it appears in the tonic major in Chopin's music, the end expressive state is never tragic. The apotheosis of the Barcarolle, for example, is of the third theme in the tonic, and its expressive end might 40 Because the Second Ballade begins in F major and ends in A minor, Kevin Korsyn (1996) reads it as an early example of directional tonality.

Samson (1996) argues that the ballade's two-key scheme may be an extension of improvisatory practice in the brilliant style of the early nineteenth-century, where highly sectionalized forms allowed for the juxtaposition of key centers. Whether we follow Korsyn in viewing the work as a harbinger of the future, or Samson in viewing it as an ex- tension of the past, it is questionable whether the Second Ballade has

an apotheosis. One might view the return of the first theme in mm. 83-140 as a failed apotheosis. Though the texture and expressive con- tent are heightened in this section, its developmental nature and even- tual modulation to D minor crushes hope of a transcendent reprise of the opening pastorale.

-

34 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

Pastoral theme Magical change of perspective 167

V/bb Db major interrupts cadence on Bb minor

170

6: etc.

187

Ascending 6ths Sequence (Striving)

Arrival, Presence,

19.0 O

Continue as in m. 191 "Tragic" 6/4

Augmented 6th (Db/B) Redirects Tonal Focus

EXAMPLE 3. Apotheosis of second theme in Chopin's Fourth Ballade.

-

CHOPIN'S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 35

be described as a perfectly fulfilled joy. The apotheosis of the Third Ballade is of the first theme in the tonic, and the end state is one of exalted happiness. In both the First and Fourth Ballades, the apotheosis is of the second theme (a de- sired state), but it appears in the submediant, a key area that Susan McClary calls the never-never land of nineteenth- century musical imagery.41 As expected, the expressive end of these two ballades is tragic.

Finally, the placement of the structural dominant presents an opportunity for the musical persona to comment on the nature of the apotheosis. In the Barcarolle the resolution of the structural dominant into the tonic coincides with the commencement of the apotheosis, contributing to the emo- tional fulfillment of its joyous state. In the Polonaise-Fantasy an apotheosis of the first theme begins on the structural dominant of Ab major, the home key, only to be interrupted briefly by an ecstatic turn to the dominant of B major, the key of the interior theme, before a fuller apotheosis of the interior theme occurs back on the structural dominant of Ab. In this case, the completion of that interior theme coincides with resolution of the structural dominant into the tonic, and the expressive state speaks of an achieved emotional strength in the face of earlier doubts. In the First and Fourth Ballades, the structural dominant of a minor tonic appears after the apotheosis, turning tragic the putative triumph of these sections. These two ballades fit similar expressive genres. In both cases a second theme represents a desired emotional state. The fulfillment of that emotional state is promised in an apotheosis, but since it occurs in a non-tonic key, the success in maintaining that state is uncertain. Failure becomes complete when a structural dominant of the minor home-key turns the music away from the promise of the de- sired emotional state. I read the end state of these two bal- lades as failed-triumph to tragic. An alternate reading might view the end states as failed-triumph to defiant.

The peripeteia in the apotheosis of the Fourth Ballade is terrible and swift in comparison to that of the First. In the First Ballade, the second theme appears in two apotheoses, first in A major and later in E6 major, which is also the key of the second theme in the exposition. The first apotheosis occurs rather early, but since its key creates an unusual rela- tionship to the home key, G minor, and the second theme, Ek, much of the energy of the development is directed to- ward modulation back to EL major. Once Ek is confirmed, the second apotheosis commences, this time including the second and third themes. The energy of this climactic sec- tion dissipates by the end of the third theme, and a direct modulation back to G minor hints of the tragedy to come. When the first theme returns over the structural dominant, we have long guessed that all is not well. Chopin's corrective swerve in the Fourth Ballade pushes the apotheosis closer to the end of the work, allowing the structural dominant to interrupt the triumph of this section. A heightened pathos results from the failure of the apotheosis at the fullness of its promise, and narrative inquiry searches for the logic of expressive states leading to that failure.

THE NARRATING SURVIVOR---THE PAST TENSE

A musical persona can act as a narrating presence, sepa- rating the teller of the tale from the tale itself. In the First and Fourth Ballades, Chopin signifies more directly this nar- rating survivor and a past tense in which the action takes place. Both Rawsthorne and Samson read the compound duple meter in each ballade as a presence linking the musical scenes implied by topical, textural, and expressive changes.42 Beyond this presence, the First Ballade offers a remarkable moment of the signified narrator. Example 4 reproduces the opening of the First Ballade with commentary. The 4/4 meter and monophonic octaves separate mm. 1-7 from the

41 McClary 2000, 123. 42 Rawsthorne 1966, 43; Samson 1992, 86.

-

36 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

f dim. p 3

P- j -Emotional involvement/

uncertainty Profound Announcement Expectation

Regaining Waltz theme 5 composure Moderato

9 - 8 6 - 5 4 - 3

Phrygian bass An old tale An old tale

EXAMPLE 4. Introduction to Chopin's First Ballade.

waltz that follows, and the opposition of these two passages correlates to the announcement of a message and the mes- sage itself. Because the opening octave C is long and low, it correlates to a state of expectation and to a profound utter- ance. As a major chord in first inversion unfolds, it makes in- tertextual reference to the paradigmatic opening of opera

4*6 recitatives.43 But I hear the move from iv6 to the cadential 6 in mm. 6-7 as central to marking narrative distance. The simple texture and half-step motion in the bass leading to the cadential 6 mimic the phrygian cadences found at the

end of certain slow movements in music of the Baroque pe- riod. To be sure, there is no upper-voice movement from 4 to 5, and the cadence proper concludes in m. 9 with the reso- lution of the dominant to the tonic early in the waltz theme. But a factor contributing to the resemblance between mm. 6-7 and a phrygian cadence is the grouping structure, wherein the relatively long note in mm. 7-8 marks a bound- ary between the introduction and the waltz. The final chords of the introduction suggest to me something old or authori- tative. Further, this progression gains salience from the dis- sonances in m. 7, suggesting a pained utterance. We hear the opening as the announcement of a profound and painful tragedy, and the closing progression tells us that the story is an old one, as if one is about to recount a legend or myth: a

43 Berger makes explicit the recitative intertext, hearing in the opening of the First Ballade the opening of Beethoven's "Tempest" sonata with its own recitative references (Berger 1996, 68-70).

-

CHOPIN S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 37

clear instance of the "once upon a time" that Adorno attrib- utes to Mahler's Fourth Symphony.44 The past tense adheres to the waltz that follows in m. 8. Eero Tarasti calls this open- ing theme "somewhat estranged . . . a waltz oubliee."45 Once upon a time, there was a waltz.

Traditionally the narrator of a poetic ballade is emotion- ally uninvolved in the story being told. In the case of Chopin's First Ballade, though, the narrator falters in main- taining this detachment. The announcement of mm. 1-2 proceeds through an embellished major-chord in the delib- erate dignity of simple octave ascents. But at the end of m. 3 the chromatic descent to F#, coupled with the diminuendo and the silence that follows, calls into question the stability of mm. 1-2. With the F# we can first guess that the previous chord was a Neapolitan, a marker of ombra. The passage of mm. 4-5 challenges harmonic analysis. We might read F# in m. 4, embellished by E#, as harbinger of a dominant, whose root appears with the repeated Ds at the end of m. 5, except that the iv6 chord in m. 6 surely points to D3 in the bass of m. 7 as the structural dominant for the introduction. Schenker's sketch of this passage includes no detail about mm. 4-5, but a register transfer from C6 in m. 3 to C5 in m. 6 of his sketch implies that the chromaticism of the inter- vening measures embellishes a simple stepwise descent.46 I read the harmonic clarity of mm. 1-2 and 6-8 in opposition to the uncertainty of mm. 3-5 as correlative to emotional de- tachment followed by involvement on the part of the narra- tor. The narrator begins with a composure that flows from detachment, but the tragedy of the tale to be told soon be- comes overwhelming; the narrator is lost in the chromatic passage of mm. 4-5, regaining composure only in the silence that precedes the entrance of the iv6 chord. The intrusion of the dissonant Eb3 into the cadential 6 of m. 7 indicates that the regained composure falls short of complete objectivity.

Example 5 is a recomposition of the introduction, removing the chromatic questioning of mm. 4-5 in order to illustrate the expressive impact of these measures. Though the recom- position is shorter than the original, it still follows all of the particulars of Schenker's sketch.

Chopin is less direct in signifying the narrator of his Fourth Ballade. We can still hear the compound duple meter as a presence threading together the musical action. In addi- tion, the opening waltz evinces the same estranged character that Tarasti hears in the waltz of the First Ballade. The strong intertextual connection between these two ballades prompts us to hear the later waltz in the past tense. Even without this intertextual connection, though, Chopin still signifies the past in ways aligned with the temporality of the nineteenth century. Monelle argues for two types of time signified in the music of this period: lyric and narrative.47 Lyric time is signified in those presentational sections in which melody comes to the fore, and in which harmonic and phrase structures are relatively stable. Narrative time is signi- fied in those sections in which harmonic and phrase struc- tures become more complex, and in which there is generally an increase in rhythmic activity. Such sections often corre- spond to transitions, and as such Monelle takes as a starting point A. B. Marx's Gang, passage work that connects the more periodic Scitze.48 Marx himself associates his paradigm for musical form, Satz-Gang-Satz, with a metaphor for ac- tivity, rest-motion-rest; and it is Monelle's insight that the

44 Adorno 1992, 96. 45 Tarasti 1994, 154. 46 Schenker 1979, Fig. 64/2c.

47 Monelle 2000, 115-21. Monelle's conception of lyric and narrative time overlaps with Berger's conception of lyric and narrative forms (Berger 1992, 1996). For Berger, narrative (temporal) forms involve a causality in which a later phrase occurs as the result of an earlier one; lyric (atem- poral) forms evince no such causality, though succeeding phrases may have mutual implications. The difference in Monelle's conception lies in his willingness to delineate narrative and lyric sections within a single work, lending the possibility of changes in temporality.

48 Monelle's discussion of Marx's Gang and Satz references earlier uses of these terms in the writings of Joseph Riepel as well (Monelle 2000, 100-14).

-

38 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

Largo Moderato

pesante dim.

--b --Composure maintained

EXAMPLE 5. Recomposition of introduction to First Ballade.

same formal paradigm may be mapped onto a temporal metaphor where the Satz (lyric time) is time arrested, and the Gang (narrative time) is time passing. Lyric time is evo- cation, description; narrative time is action.-

Nineteenth-century ballet is particularly instructive in re- gard to the coordination of lyric and narrative time with music. During Tchaikovsky's Nutcracker, for example, there are moments when actions are performed: the children enter the hall for their Christmas gifts, the Nutcracker battles the Mouse King. During these moments the dancers mime the action, and the music is less melodic, often exhibiting quick changes in texture and harmony. We experience narrative time. But there are also moments when the action of the story stops: Clara watches the dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, or the dance of the Reed Flutes. During these mo- ments, miming ceases and dancing commences while the music becomes periodic with a clearer harmonic structure. We experience lyric time. The mixing of lyric and narrative times in the telling of a story is not unique to music. From the fabula (plot) and sjuzet (discourse) of the Russian Formalists, to the dialogism of Mikhail Bakhtin's theory of the novel (1981), to the five codes of Roland Barthes's S/Z, literary theorists have long recognized that story telling is a mix of different types of writing.49 Few stories emplot a lin-

ear sequence of action without the detours of description, evocation, and characterization.

In instrumental music of the nineteenth century, entire pieces may signify lyric time. During Schumann's "Traiu- merei," for example, time is suspended while we view the dreamer in full reverie. Even in the more excited movements of Kinderszenen, like "Wichtige Begebenheit," the periodic structure, the lack of transitions, and the relative brevity of the work keep time at bay, so that we can view the important event in an extended temporal stasis.50 In Chopin's music lyric time is associated with the salon style: the nocturne, the

49 The termsfabula and sjuzet are sometimes taken to mean story and plot, respectively. Bakhtin's dialogism describes the way that utterances mix

different types of language. The novel, for example, mixes everyday lan- guage for its dialogues, poetic language for its descriptions, and so forth. Bakhtin's dialogism heavily influences Julia Kristeva's argument in coining the term intertextualite in "The Bounded Text" (1980). Kevin Korsyn discusses Bakhtin's writings as philosophical backdrop to a theory of intertextuality in music in "Beyond Privileged Contexts" (2001). Barthes's five codes, though directed at how readers make sense of texts, imply that different types of writing make up a literary work. Musical extensions of Barthes's codes appear in Abbate's "What the Sorcerer Said" (1989), Patrick McCreless's "Roland Barthes's S/Z" (1988), and Robert Samuel's Mahler's Sixth Symphony (1995).

50 Anthony Newcomb (1987) argues that when the character piece in- vades Schumann's larger works, like the "Im Legendenton" section in the first movement of the op. 17 Fantasie, it is a sign of Schumann's im- pulse to narrate in the ways that his favorite novelists do. Newcomb's idea resonates with the literary theories listed in the previous footnote.

-

CHOPIN S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 39

poeticized waltzes and mazurkas. Narrative time is associ- ated with the virtuosic style: the etudes, the concertos, and portions of the polonaises. This broad division of Chopin's music interacts with an astonishing intertextuality. As Sam- son illustrates, bel canto, stile brillante, baroque textures, and Polish folk music all play parts in the creation of Chopin's style.51 In his larger works, Chopin tends to mix these influ- ences so that lyric and narrative time alternate, and this tech- nique is nowhere more apparent than in the ballades, where the lyricism of a slow waltz may lead to the narrative pulse of a virtuosic passage. Whether this mixing of styles represents a poietic impulse to narrativize music may always be a matter of debate as we gain new perspectives on Chopin's creative life, but the esthesic impulse to read narrative into Chopin's larger works gains impetus from this mixture. The fourth rows in the tables of Example 1 align formal sections of the First and Fourth Ballades with expressions of lyric and nar- rative time, showing as well that lyric time is associated with themes, while narrative time is associated with Gange. Apo- theosis presents a special difficulty with respect to lyric and narrative time, since the heightened textures and rhythmic surfaces may give the impression of narrative action. Still, I hear apotheosis in general as an exalted lyric time. I mark the apotheosis of the Fourth Ballade, however, as "Lyric to Narrative" because passages leading to the climax of this sec- tion have a striving quality, suggesting to me an active effort to maintain the exalted effect. I retain Marx's term Gang in the tables, even though it fits Chopin's music uncomfortably. Monelle argues that the Gang in late eighteenth-century music is semantically cool.52 However in Chopin's music-, arguably in Beethoven's as well-the Gang seems rich with meaningful action.

Either lyric or narrative time may be coordinated with structures that signify the present or the past. Though the existence of a narrator places the events of a story in the past

tense and positions the reader in a temporal space after those events, the pacing of action may draw the reader into the story to experience it as if in the present. Conversely, the pacing of action might maintain significations of the past, so that the reader is never drawn into the story. Similarly, though Monelle describes lyric time as an extended present (or an empty present), he is perceptive in claiming that the tempo- ral dynamic of the nineteenth century often sentimentalizes time, so that lyric evocations become empty longings for the glories of the past.53 Example 6 coordinates narrative and lyric time on a horizontal axis with past and present on a vertical axis. The intersection of signifiers for past/present and lyric/narrative allow for four temporal possibilities: time passes in the present (narrative/present), time passes in the past (narrative/past), time stops in the present (lyric/ present), time stops in the past (lyric/past). Hearing these possibilities within the dynamics of story telling means that the presence of a narrator frames the entire sequence of events as something complete, something in the past. Tem- poral shifts occur within the perspective of that narrative frame, implying that we are drawn into the past as if it were happening before us, or that we remain removed from the past, experiencing it as if at a distance.

In Chopin's music action is often suspended so that the narrator may indulge in the poetry of evocation and also con- template a scene from the past. Chopin's focus on the sub- dominant supports an idealized past in many of these lyric sections. Charles Rosen's correlation between a dominant/ subdominant opposition and an active/passive one is well known, but a second mapping of this harmonic opposition correlates the dominant with movement toward the future (time as experienced rushes forward) and the subdominant with looking toward the past (time as experienced turns back).54 An example of Chopin's use of the subdominant to

51 Samson 1985. 52 Monelle 2000, 107.

53 Monelle 2000, 115. 54 Pertinent is Rosen's characterization of the subdominant in the early

Romantic period as representing "a diminishing tension and a less

-

40 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

Narrative Time Lyric Time (Action) (Evocation) Gang Satz

Present Time passes in the present Time stops in the present

motion to dominant

Past Time passes in the past Time stops in the past

motion to subdominant

EXAMPLE 6. Temporality in narrativeforms.

signify the past appears early in the First Ballade. Beginning in m. 36, diminished-seventh chords, increased rhythmic ac- tivity, and agogic accents on weak beats point to movement away from the lyric time of the opening waltz. In m. 40 Chopin marks the music agitato, and by m. 44 the full virtu- osic style signifies narrative time. At the end of this narrative section, the music commences its first modulation, ostensibly toward the key of B6 major. Example 7 reproduces this pas- sage, including a recomposition of the opening of the second theme. In m. 63-4 a 4-3 motion in the upper voices marks the bass F as a dominant. A horn topic in mm. 64-7 an- nounces the second theme, but the earlier calando and smorzando markings coupled with the ritenuto of m. 66 gives this horn call a dysphoric character. When the new theme arrives in m. 68, the addition of A6 above the supposed tonic, B6, redirects the harmonic goal to BV's subdominant, E6, which will be the key for this theme. The recomposition of this passage in Example 7 illustrates how easily the second theme might have remained in B6, the key toward which the transition seems directed. I read the redirection to Eb as a

means of reversing the passage of time. The musical persona seems intent on reviewing the past.

The subdominant signifies the past in the first theme of the Fourth Ballade as well. Example 8 reproduces part of the opening motto and a rhythmic reduction of the waltz theme that follows. The key of the opening motto is C major, and a V7/IV in m. 2 marks F as a subdominant before a cadence affirms C in m. 3. F's status as subdominant is maintained by a plagal prolongation of C in mm. 6-7. The motto is lyrical evocation, an extended arresting of time. Though F as sub- dominant appears early in the passage, it moves directly to the dominant in m. 3; therefore, I read this lyric section in the present. Temporality changes with the melodic turn of D6 and B? in m. 8, which shifts the tonal focus from C major to F minor. Because C is so clearly the tonic in the first seven measures, we may well hear the move to F minor in m. 8 as motion to the subdominant instead of motion from a domi- nant to a tonic. At the moment when the first theme arrives, the musical persona looks to the past. Though both the opening motto and the first theme are lyric, the motto signi- fies the present, while the first theme signifies the past. The narrative technique here is quite different from that which opens the First Ballade. In contrast to a narrator whose emo- tional uncertainty in the introduction signals the tragedy to come, the musical persona of the Fourth Ballade sets the "once upon a time" with an optimism tinged with the conso- lation of a religious topic suggested by the plagal successions in mm. 6-7. When the waltz theme enters in m. 8 with its reduced rhythmic activity and minor key inflected as a sub- dominant, we can hear it as the reason that the narrator at- tempts consolation in the opening motto. Now (motto), I begin to find consolation and hope, but back then (first theme) ...

Chopin trumps the subdominant during the course of the waltz theme, whose three phrases tonicize Ab major and B6 minor before a quick return to F minor. The theme loses itself in the subdominant, and an ingenious ambiguity allows the melody to appear both in the tonic (mm. 8-10) and in

complex state of feeling, and not the greater tension and imperative need for resolution implied by all of Beethoven's secondary tonalities" (Rosen 1971, 383).

-

CHOPIN S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 41

68Va ------- ----calando

Second theme 8Vea . . e Meno mosso

Dysphoric Shorns add 7th to reach Eb

V ofB

Recomposition

Bb

EXAMPLE 7. Transition to second theme ofFirst Ballade.

the subdominant (mm. 18-20) without a change in pitch level. Harmonic motion from the subdominant back to the tonic is accomplished rather abruptly with the dominant in the second half of m. 22, redirecting tonal motion after a presumed cadence in B6 minor: a willed effort brings the waltz back into focus. Four variations of this theme appear throughout the ballade, during the first of which Chopin interrupts the motion back to the tonic with a direct modu-

lation from B1 minor to G6 major in m. 38. Example 9 re- produces this passage with commentary. Hatten associates such modulations by thirds to changes of perspective, or sud- den insight.ss55 In addition, the key of G6 had special signifi- cance in the early nineteenth-century, where it was associ- ated with the remote, the profound, and the transcendentally

55 Hatten 1994, 22-3.

-

42 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

Lyric time/the present

Shifts etcetc.

tonal focus

Waltz Plagal close Lyric time/the past f: i V/III III

Phrase 2: III-iv Phrase 3: V/iv-iv-V 13 15 .18 21

etc etc.Shifts etc.

III iv/iv V/iv iv V/iv iv V

EXAMPLE 8. Opening motto and waltz theme of Chopin's Fourth Ballade.

spiritual.56 Schubert's Impromptu in Gb makes a particularly evocative intertext. A deep stasis of the melodic and har-

monic material supports the remote and spiritual topic in mm. 38-46. But the stasis sends our sense of time even

56 Hugh MacDonald (1988) writes that in the nineteenth century Gb major was also associated with the otherworldly, the ecstatic, and the mysterious. These signifieds for Gb rest on an opposition between the relative distance of a key in relation to a home tonic, and the absolute distance of a key in relation to C. Under an absolute measurement, Gb is taken to be the most distant key from the fixed point of C. The C/Gb opposition maps onto a number of extra-musical ones: earthly/

heavenly, known/unknown, ordinary/sublime, etc. As always, these mappings must be read within a context of other signifiers. Chopin, for example, uses the key of G6 in two etudes, the so-called "Black-Key," op. 10 no. 5, and the "Butterfly," op. 25 no. 9; but, lacking other markers for the sublime, these etudes form only a weak intertext with the pas- sage in question from the Fourth Ballade.

-

CHOPIN S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 43

Harmonic Stasis Third Relation Direct Modulation Gb

36 "Sublime"

bb: Gb: 42 PS 0

,

Frh inoh-ps

Further into the past

EXAMPLE 9. Sublime interruption in Chopin's Fourth Ballade.

deeper into the past, a problem exacerbated by implications of Eb minor in mm. 45-7 suggesting a move to the subdomi- nant of the subdominant of the home key. So far there have been no narrative sections to offer a sense of action so neces- sary to story telling, and the lyric sections seem intent on sending the listener further into the past. Only the sequence and canonic writing of mm. 50-3, and the dominant of m. 57 redirect the harmony back to the tonic, saving the musical narrative from the temporal catastrophe of a story that never moves forward in time and that gives no sense of action.

At m. 58 the waltz theme returns in a variation elaborate enough to lead to the first instance of narrative time: at last things happen. We understand how long narrative time has been kept at bay by comparing this ballade to the first, where the waltz theme appeared only once before increased rhyth- mic and harmonic activity propelled the music around m. 36.

In the Fourth Ballade, Chopin maintains control of lyric time, even driving the music further into the past with those emphases on the subdominant, before the transformation to narrative time begins around m. 68. By m. 72 narrative time is in full force as the music begins an ascending sequence that promises modulation. This narrative section interrupts completion of the waltz's second variation before it can re- turn to the tonic, following a pattern set in the first variation and continued in each subsequent one. With the exception of the waltz theme itself, each variation will be interrupted before it can exit the subdominant. The narrator is com- pelled to repeat part of the story with each variation but is unable to bring that story to its completion.

This repetition compulsion leads to a remarkable moment when the opening motto returns in the key of A major at m. 129. We find ourselves at the beginning of the story all over

-

44 MUSIC THEORY SPECTRUM 26 (2004)

again. As before, the motto leads to the waltz theme, this time treated in canon at the octave in the key of D minor. If the theme itself is marked as sadly introspective, then a canonic treatment of it makes the music authoritatively so, as each voice takes up the musical persona's subjectivity. The persona tries to soften the edges of this canon, modulating from D minor in m. 135 to F major in m. 138. But the canon returns strengthened by the entrance of a third voice in the key of F minor. Sequential treatment promises that the canon will again be softened by modulation, this time to Ab major in m. 142. But a final appearance of a three-voice canon in Ab minor fails to elicit a softening response. A de- scending chromatic line in the left hand of m. 144 under- scores this failure before the waltz theme moves to B6 minor once again.

APOTHEOSIS IN THE FOURTH BALLADE

A return to Example 2 allows a closer look at the second theme, which commences in m. 80 after a brief narrative sec- tion. The shift from narrative to lyric time is so stark that the descending sequence beginning in m. 80 seems a necessary and calming prelude to the theme's proper entrance with the dolce of m. 84. Chopin alters the usual form of the circle-of- fifths sequence by building a major triad on 7 in the bass and preceding that triad with its own dominant. Although the sequence confirms Bb major, the close connection between the major triads on B6 and A on the downbeats of mm. 81 and 82 temporarily suspends normal tonal syntax, suggesting the expressive tonality evident later in the century, where tonal motion up or down a half step correlates with increased or decreased emotional tension. The iambic rhythm, the major thirds in the upper voices, and the consonant 6-5 ac- cented passing tone in m. 92 establish this second theme as a pastorale or siciliana. Chopin uses the same topic to open his Second Ballade, and comparison of the two themes illus- trates a different character to the pastorale of the Fourth. In

the earlier case the thoroughly diatonic harmony of the first eighteen measures firmly establishes the simplicity of expres- sion often associated with the pastoral topic. In the Fourth Ballade, though, unquiet minor thirds in the common-tone o7 chords of mm. 86-7 are in opposition to the cheerful major thirds common to pastorales. Particular pains are taken to reach the subdominant, another marker for the pas- torale. The first such move appears in mm. 86-9, where the tonic becomes a V7/IV before moving to IV. The arrival on the subdominant in m. 89 is too brief, falling immediately to the supertonic in that same measure. During a second pass at the subdominant in mm. 92-7, an ascending, chromatic 5-6 sequence adds urgency to the theme, heightened by compar- ison to the earlier descending sequence that calmed the mu- sical expression. When the music reaches its goal in m. 97, the subdominant extends more than a measure before a ca- dence closes the theme. The effort to hold on to the em- blematic subdominant idealizes the pastorale, as if it can recompense the awful present that shatters this theme in m. 100, where another narrative section commences in the key of G minor.

The struggle of the Fourth Ballade is to transform the second theme into an apotheosis while holding at bay the possibility of apotheosis for the unfortunate waltz theme. We might view apotheosis in this ballade as an attempt to transform through action an idealized past into a realized present. During the final appearance of the waltz theme, a dramatically enriched rhythmic profile for the accompani- ment and a generously ornate fioritura variation of the melody signals growth of the waltz into apotheosis. Beautiful as this variation is, the musical persona again interrupts completion of the waltz in favor of an apotheosis of the pastorale. Example 3 shows the relevant passage. After a carefully prepared motion to the minor subdominant, B%, with an extended pedal on its dominant, F, in mm. 162-8, the pastoral theme simply appears in Di major in m. 169. The return of this theme is unprepared harmonically, and

-

CHOPIN S FOURTH BALLADE AS MUSICAL NARRATIVE 45

therefore magical in its aspect.57 Yet there is an unearned quality to this interruption, and the following passages at- tempt to reaffirm the status of D. In particular an ascending chromatic sequence in mm. 187-90 reaches a breathtaking cadence in DM on the structural downbeat of m. 191. Here the melody falls away, leaving a sweeping texture that bears an intertext with Chopin's Etude op. 25 no. 12. The pure vir- tuosic style indicates narrative action in the course of this apotheosis with a power to bring into full flower the desired state of the pastoral theme. A D6 pedal through this passage underpins an attempt to hold on to the climax and its atten- dant implications of the plenitude of presence. But D1 is col- ored immediately by the augmented triad in m. 192, leading to the vi chord of m. 193; and when B? forms an augmented 6th with the pedal Db in m. 194, we know that all is lost, be- cause this interval must find its resolution in an octave C that will direct harmonic motion away from Db. Indeed, we may recall that the same pitches, D6 and B?, refocused the opening of this ballade away from C major and toward F minor. As expected, in m. 195 the music lands on an F- minor 6 chord, underscored by hypermetric placement, tex- tural change, phenomenal accent, and an embellished arpeg- gio. Hatten uses the expression arrival 6 or more poetically salvation 6 to describe certain major-mode 6 chords that re- ceive the kind of emphases we hear in this measure.58 The minor 4 chord in m. 195 is an evil twin that signals a deep

and personal tragedy in ironic opposition to the salvation and transcendence of its major-mode counterpart.