China's International Relations Essay

-

Upload

ewen-dymott -

Category

Documents

-

view

28 -

download

2

Transcript of China's International Relations Essay

Ewen Dymott – University of Bristol

1

Discuss the claim that as China moves to join the war on ISIS, there is growing evidence that

its military and security interests have moved beyond its domestic borders

Following the death of Mao Zedong on the 9th September 1976, China began to shift its focus

away from Marxist/Maoist ideology and towards economic pragmatism. Mao’s era was

characterised by a heavy emphasis on China’s domestic situation in an attempt to consolidate

support for the fledgling communist state, and this domestic focus was also evident in the

Chinese Communist Party’s (C.C.P) foreign policy. The end of the Second World War and the

early stages of the Cold War were periods of the 20th Century that were arguably the most

volatile due to the ensuing struggle between Western capitalism, and the communist ideologies

of the Soviet Union and China. Right from the start of Mao’s time as the leader of the C.C.P in

1949, he was faced with a direct challenge to the security of his regime which came in the form

of the Korean War (1950-1953). China’s involvement in the Korean War was largely motivated

by a desire to protect her domestic borders from the ‘imperialist’ United Nations forces led by

the United States. However, under Deng Xiaoping (1977-1992), China adopted a more

pragmatic approach focused on economic development and traditional Chinese culture, rather

than the revolutionary ideology promoted by Mao. It is important to note that during this period,

and subsequent periods, China retained its communist characteristics, but chose to focus on

economic growth and development over politics and ideology (Robinson, 1995). Chinese

foreign policy became centred on the national interest, which manifested itself in the form of a

more open approach to foreign investment, technology transfer and trade (Robinson, 1995). In

order to achieve Deng’s economic goals, China believed that peace was the key to prosperity

and actively sought closer relationships with Washington and Moscow in order to try and

nullify any perceived threats to Chinese territory (Robinson, 1995). Crucially, China also began

to turn to the ‘Third World’, and began a programme of military assistance that included the

sale and transfer of nuclear weapons technology to Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia,

and Syria (Robinson, 1995). When coupled with the increased establishment of global

diplomatic relations, this period represents a turning point in Chinese history – one in which

China became motivated by economic development. This trend continued under subsequent

leaders, with increasingly active participation in international institutions and regional politics

with the belief that, as part of the international system, China would be better able to influence

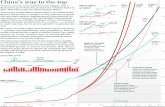

global policy and effect economic growth. Since 1978, China has experienced a real annual

GDP growth rate of over 9% (Cable & Ferdinand, 1994).

China’s pragmatic desire for increased economic growth has gone hand in hand with

globalisation. As China seeks to trade with more markets across the globe, states have become

more economically dependent on one another. As a result, each country has gained strategic

interests in its international partners, and China is no exception. As China has grown

economically, the C.C.P has invested heavily in its military capabilities, which now allow the

People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to project military power beyond its borders (Roy, 1996).

However, China’s definition of what constitutes its borders is not necessarily universal - the

ongoing issue over the South China Sea exemplifies this. As a result of China’s economic

progress, and an increasingly globalised and interconnected world, China now has strategic

interests beyond its borders. However, there is a difference between strategic interests and

security interests, the latter of which are the topic of discussion. Security interests can be

considered strategic, but so can economic interests.

Ewen Dymott – University of Bristol

2

This essay will present the argument that China’s rumoured involvement in the war against the

Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (I.S.I.S) is motivated more by economic interest and therefore

it cannot be used as evidence to suggest that China’s military and security interests have moved

beyond its domestic borders. Indeed, if we look at the areas of globe in which China is most

militarily engaged, and the areas in which China has publically stated security interests, we can

see that they are heavily focused around China’s borders. Furthermore, even though China now

has the necessary military capabilities to pursue its foreign security interests, it is limited in

terms of how it can do so by the ‘Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence’. In order to make

this argument, this essay is divided into three sections. The first shall focus on the ‘Five

Principles’ and explain how they limit China’s ability to pursue security interests abroad but

legitimise military action within China’s domestic sphere, as well as how the very continuation

of this policy into the present day is evidence that China is still domestic focused with regards

to its military and security interests. The second part of this essay will explain the extent to

which China is involved in the war against I.S.I.S, and how any proposed action is motivated

more by China’s economic interests than security interests – thereby nullifying the claim that

China’s military and security interests have moved beyond its domestic borders. The third

section of this essay will look at two of China’s most pressing security issues, the South China

Sea and North Korea, and explain how these are considered security issues in close proximity

to China’s domestic borders. For the purposes of this essay, security issues will be classified

along more traditional theoretical lines in terms of threat to the Chinese state and the communist

regime, rather than notions of economic or human security.

The Limits of the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence

The ‘Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence’ first appeared in the text of a treaty between

India and the People’s Republic of China (P.R.C) (Fifield, 1958). On the 29th April 1954, the

treaty to clarify India’s role in Tibet was signed in Peking, containing the ‘Five Principles’

(Fifield, 1958). The principles were worked out between three prime ministers, and so no single

individual can claim patronage over them (Kao, 1957; Nehru, 1957). Even though the ‘Five

Principles’ first appeared in the early 1950s, they remain the framework around which

contemporary Chinese foreign policy is orchestrated, as demonstrated by the Chinese Premier’s

remarks in 2004: “as a large developing country with 1.3 billion people, China will, as always,

steadfastly commit itself to the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence” (Jiabao, 2004: 367).

They remain such a fundamental part of Chinese foreign policy that they have been written into

the constitution of the P.R.C (Zhenmin, 2014).

The Five Principles are as follows: mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity,

mutual non-interference in domestic affairs, mutual non-aggression, equality and mutual

benefit, and peaceful co-existence (Chung, 2009). Mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial

integrity implies that each state has a right to freely choose its own economic, legal, political,

social, and cultural systems combined with the responsibility to respect the diversity of

civilizations across the globe, and that they enjoy these rights on the basis of independence and

equality (Hong, 2014). According to the Director-General of the Department of Treaty and

Law within the Chinese Foreign Ministry, this also includes the right for states to take “lawful

measures within its own territory to defend its territorial integrity” (Hong, 2014: 503). This is

significant because whilst this principle outlines that the independence and sovereignty of

Ewen Dymott – University of Bristol

3

nations are guaranteed (therefore implying that intervention within another state would be

against this principle), it allows for a scenario in which aggression and force could be used to

defend China’s territory – a provision particularly relevant to its border disputes and

aspirations. Mutual non-interference in domestic affairs safeguards the independence of states,

and acts to combat hegemonism (Hong, 2014). This principle essentially states that no nation

has the right to intervene in the affairs of another and shall not “organise, foment, finance,

incite or tolerate subversive, terrorist, or armed activities directed towards the violent

overthrow of the regime of another state” (Hong, 2014: 503). Mutual non-aggression dictates

that, unless authorized by the United Nations Security Council or in exercise of self-defence,

all states must refrain from the threat or use of force against another state (Hong, 2014).

Equality and mutual benefit outlines the Chinese position that all states are to be considered as

equals in the international system, regardless of their political, economic, or social systems

(Hong, 2014). Mutual benefit is most often applied to economics, and ensures that there can be

no ‘one-sided’ trade deals and that all participants stand to gain from them. Finally, the

principle of peaceful co-existence suggests that international disputes between nation states

should be resolved through peaceful means in accordance with international law (Hong, 2014).

These foreign policy principles are important for a number of reasons. Firstly, they heavily

limit the extent to which China can act to support its military and security interests beyond its

domestic borders, and in fact they “set particular and predictable limits on the choices available

to Chinese foreign policy makers” (Richardson, 2009: 5). Most notably, in relation to the war

against I.S.I.S, the principle of mutual non-interference in domestic affairs prohibits China

from intervening in the domestic affairs of both Syria and Iraq. Because of this principle in

particular, even though China may have strategic interests abroad which can include both

economic and security dimensions, Beijing cannot interfere in what is seen as a domestic

problem. Therefore, if Beijing’s proposed involvement in the war against I.S.I.S is considered

as evidence for expanding military and security interests, and this essay will argue that it is not,

China would be unable to act in favour of these interests anyway because of the limitations of

the ‘Five Principles’. Andrew Mertha (2011: 213) supports this view by arguing that China has

“voluntarily constrained itself in its international interactions from the 1950s to the present

(day)”. The second reason why these principles are important is because, whilst they do not

allow for military intervention abroad, they quite clearly allow for China to pursue her domestic

military and security interests. The use of the word ‘mutual’ is very important in this case,

because China could argue (with reference to its domestic border confrontations) that another

state, by laying claim to ‘Chinese territory’, is directly breaking the principle of mutual non-

interference in domestic affairs. This then allows China to use its military capabilities to defend

its territory without contravening her own principles, because another party would have already

broken the ‘mutual’ element of the ‘Five Principles’. This is arguably the most significant

determinant as to why China’s military and security interests are concentrated around its

domestic borders, and not beyond. In short, the current Chinese foreign policy framework, the

‘Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence’, limit China’s ability to act upon its interests abroad,

but promote the ability to act along her domestic borders. This is evidence that China has not

expanded her military and security interests abroad because if Beijing had begun to look further

afield, it would have to abandon, or at least redesign its policy principles.

Ewen Dymott – University of Bristol

4

China and the ‘Islamic State’

Ever since the C.C.P passed a counter-terrorism law in December 2015 that allowed the P.L.A

to be deployed overseas on counter-terrorist operations, there have been rumours circulating

amongst the media that China will move to join the war against I.S.I.S (Irish, 2016). However,

any proposed involvement in the multinational US-led coalition in Iraq and Syria was quashed

by the Chinese Foreign Minister, Wang Yi. On the 12th February 2016 he stated that “There is

a tradition in China’s foreign policy. We do not join in state groups that have a military nature

and this also applies to international terrorism co-operation” (Irish, 2016). Despite this

assertion that China will not be taking part in any military activity in the Middle East, Wang

Yi did emphasise that China had been fighting terrorism “in its own ways” (Irish, 2016).

According to the Business Insider, Beijing has been getting involved diplomatically in Syria

by recently hosting the Syrian Foreign Minister and opposition officials (Irish, 2016). In a

recent interview, Wang Yi himself outlined the levels of Chinese involvement in Iraq saying

“we have been helping Iraq with counter-terrorism capacity building, and conducting

intelligence sharing with certain countries”, he went on to add “we are (also) working with

countries to cut the channels of financial resources and movement of terrorists” (Irish, 2016).

Nevertheless, the C.C.P is not offering diplomatic and intelligence assistance to the

governments of Iraq and Syria altruistically. As mentioned earlier, through globalisation, China

has developed strategic interests in the Middle East. Some analysts and journalists argue that

China’s assistance in the region is motivated by security interests that specifically relate to a

growing number of Chinese-origin terrorists that have joined ISIS (Gertz, 2016). Indeed, I.S.I.S

have reportedly shown aspirations to expand its territory towards Xinjiang province – home to

a large Chinese-Muslim population (Chaziza, 2016). According to media reports, between 100

and 300 Uighur militants from Xinjiang have been training with I.S.I.S in order to carry out

terrorist attacks on Chinese soil. (Patranobis, 2014; Ng, 2014; Martina, 2014). Yet, in the face

of what Chaziza (2016: 26) describes as “a real danger to Beijing’s national security”, the most

decisive action taken by the Chinese government so far has been the evacuation of most of the

10,000 Chinese citizens living in Iraq (Hunwick, 2014). With respect to the borderline non-

existent involvement of the Chinese government in the war against I.S.I.S so far, it is

impossible to conclude that there is evidence for China’s military and security interests having

moved beyond its domestic borders, mostly because China has not involved and indeed cannot

involve its military in Middle Eastern affairs, in line with their ‘Five Principles of Peaceful Co-

Existence’ foreign policy framework.

Instead, the Chinese position towards Iraq and Syria should be viewed in terms of Beijing’s

economic plans, and there are two factors that have influenced the C.C.P’s policy. The first

factor relates to energy supplies. As a ‘developing’ and economically growing country, China

is heavily dependent on its manufacturing sector, which in turn relies upon the importation of

raw materials and energy, mostly in the form of non-renewable fossil fuels. The Middle East

is China’s largest source of crude oil, and in 2014 it supplied China with 3.2 million barrels per

day (Energy Information Administration, 2015). Since 2003, China has invested around $10

billion in the Iraqi oil industry, and approximately 50% of Iraq’s oil exports go to China which,

as of 2014, made Iraq the fifth largest foreign source of crude oil in China (Zambelis, 2013;

Energy Information Administration, 2015). By 2035, 80% of Iraq’s oil production is estimated

to be destined for China (Roberts, 2014). With the instability in Iraq and Syria caused partly

by the ‘Islamic State’, a significant proportion of China’s vital oil supplies are under threat and

Ewen Dymott – University of Bristol

5

may lead to an increase in oil prices and jeopardise the already hefty investment made into

Iraq’s oil industry (Juan, 2014). Following the slowdown of the Chinese economy in January

2016, disruption to a vital oil supply would certainly hinder any recovery, and this is a far more

compelling explanation for the Chinese policy choices in Iraq and Syria than security interests

given the economic focus of recent Chinese leaders including Xi Jinping.

The second, and most significant economic factor driving China’s limited involvement in the

war against I.S.I.S, is the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative. In September 2013, Chinese President

Xi Jinping first eluded to a proposal to create a ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ at a speech in

Kazakhstan (Xinhua, 2013). Later that year in October, Xi, and his Premier Li Keqiang,

attended the Asia Pacific Economic Co-operation (A.P.E.C) summit, in Indonesia, and the East

Asia Summit, in which they outlined proposals for a 21st Century ‘Maritime Silk Road’ (Ruan,

2014). By early 2015, the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ were

amalgamated into the ‘One Belt One Road’ (O.B.O.R) concept, with the ‘belt’ referring to a

land route, and the ‘road’ referring to a maritime route to connect Asia, Europe, and Africa

(Summers, 2016). The O.B.O.R vision seeks mutual benefit to all participants, and so is

compatible with the ‘Five Principles’ framework (State Council, 2015). Section IV of the

‘vision document’ contains five co-operation priorities: policy co-ordination, facilities

connectivity (which involves the building of infrastructure, logistics, and communications and

energy infrastructure), unimpeded trade (free trade areas, customs co-operation, balancing

trade flows, and protecting the rights of investors), financial integration, and ‘people-to-people

bonding’ (student exchanges and tourism) (State Council, 2015). The O.B.O.R proposal has a

huge geographic scope, and under Section III of the ‘vision document’, it states that the belt

focuses on linking China, Central Asia, Russia, Europe, the Persian Gulf, the Mediterranean

Sea, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and the Indian Ocean (State Council, 2015). The South China

Sea is also to play an important part in bringing together trade between China and Europe, and

China and the South Pacific (State Council, 2015). According to a proposed map of the trade

routes published by the Xinhua news agency, the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ will pass through

both Iraq and Syria and seeks to include the Middle East by routing part of the ‘Maritime Silk

Road’ through the Suez Canal and the Persian Gulf (Xinhua, 2015; Strategic Comments, 2015;

Minnick, 2015). According to Nataraj & Sekhani (2015), the O.B.O.R initiative is the

centrepiece of China’s foreign policy and domestic economic strategy, and Beijing has already

allocated $40 billion to a ‘Silk Road’ fund. This initiative represents a defining moment in

China’s foreign policy and Xi Jinping’s presidency, designed to enhance trade and financial

links between China and a large portion of the world, with some 3 billion people estimated to

live within the economic belt alone (Summers, 2016). Long-term instability within Iraq, Syria,

and the Middle East as a whole, caused by I.S.I.S, is bound to affect the success of this proposal,

and given the economic focus of the current Chinese leadership, it is logical to argue that the

O.B.O.R route is the determinant motive for Chinese policy against I.S.I.S – especially given

the already substantial investment into the scheme. Given the two economic factors outlined,

it is clear that Beijing’s involvement in the war against I.S.I.S is not evidence for the pursuit of

military and security interests beyond its borders, but a continuation of China’s economic

globalisation and development plans.

Ewen Dymott – University of Bristol

6

China’s Security Interests

After concluding that China’s involvement against I.S.I.S is not motivated by security interests

and cannot be used as evidence to support the claim these interests have moved beyond China’s

domestic borders, it seems reasonable to examine where China’s security interests lie. This

section shall briefly identify two of Beijing’s top security interests; the South China Sea, and

North Korea – both of which are unfolding in close proximity to China’s domestic borders.

The South China Sea has been a long running problem for China, and for Southeast Asia as a

whole for a number of decades, because of overlapping territorial claims to many of the islands

within the sea by China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan and Japan (Lowy

Institute, 2016). The South China Sea is a significant maritime trading route that contains rich

fishing grounds, and reportedly large reserves of oil and natural gas (Lowy Institute, 2016).

However, for China, this issue is about something far more fundamental that economics alone;

in essence this dispute is about Chinese territory (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s

Republic of China, 2015). It is an extremely important Chinese national interest because some

countries have occupied reefs and islands in the South China Sea which, in the eyes of the

C.C.P, violates Chinese territorial sovereignty (Hao, 2011). Furthermore, the South China Sea

is the ‘southern gate’ of China’s national defence and security, and any actions taken that will

destroy the peace and stability of the region (provoked by the border disputes) are a major

threat to Chinese national security (Hao, 2011). In recent years, there has been an increasingly

noticeable P.L.A presence on some of the Chinese claimed islands that threatens to escalate

this dispute further. Territorial integrity is a vital pillar of the C.C.P’s national identity – as

displayed by its prevalence in the ‘Five Principles’, and in the wake of the economic slowdown,

nationalism has taken on increasingly greater importance for the legitimacy of the C.C.P, and

consequently the party’s survival. (Turner, 2016). Therefore, because the survival of the

communist regime is at stake, this is clearly a security issue for the Chinese. This problem is

centred on Chinese borders and supports the argument that China’s military and security

interests have not moved further afield.

A second major Chinese military and security interest lies in North Korea. Since Kim Jong-Il

began North Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons technology in the 1990s, China’s territorial

security has been put under strain by the increasing likelihood of war breaking out on the

Korean peninsula (Shambaugh, 2003). On the last occasion of war between the two Koreas,

between 1950 and 1953, China became involved out of fear that the U.S led United Nations

forces would push beyond the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (D.P.R.K) into Chinese

territory, thus threatening Mao’s fledgling communist state (Hao & Zhai, 1990). Since then,

the D.P.R.K has conducted four nuclear weapons tests which is challenging the international

community as well as Chinese and regional security. The worry for China is that in the event

of war, history may very well repeat itself and the P.L.A could be drawn into another conflict

to protect its borders and to prevent the collapse of yet another communist state (Shambaugh,

2003). China is actively engaged in preventing the emergence of a nuclear North Korea, but

frequently finds itself caught between criticism from Kim Jong-Un, for aiding ‘imperialists’ in

imposing the U.N-backed sanctions against the regime, and from the U.S for not taking a

sufficiently hard-line approach against its communist neighbour. North Korea is a clear security

interest for China, and like the South China Sea issue, is occurring along its borders. In

examining two of China’s most prevalent security issues, it can be seen that they fall

comfortably within the realm of its domestic sphere, and whilst some could make the argument

Ewen Dymott – University of Bristol

7

that China is acting on behalf of the security of the entire Southeast Asian region, a more

convincing argument is that China is motivated by a desire to protect her own national security.

Conclusion

The claim that China’s proposed involvement in the war against I.S.I.S is evidence for the

pursuit of security interests beyond its domestic borders does not stand up to scrutiny. Indeed,

the so far limited actions of Beijing are motivated by economic concerns rather than security.

The importance of Iraq and the Middle East as a whole to China’s energy supplies, that are

vital to continued economic growth, combined with the desire for stability within Iraq and Syria

for Xi Jinping’s flagship ‘One Belt One Road’ policy, far outweigh any security interests that

may face China. If it were the case that China had security interests in the region, it is highly

likely that they would be unable to pursue them anyway because of the limitations of their

foreign policy framework – the ‘Five Principles’. The very fact that this framework does not

allow for foreign military involvement, despite the passing of a new counter-terrorism law, is

further evidence that China’s military and security interests remain centred around its domestic

borders. The location of two of China’s most pressing security interests, the South China Sea

and North Korea, further supports this argument. However, it is not inconceivable that China

will develop a serious security issue in the Middle East if more of its Muslim population from

the Xinjiang province train with I.S.I.S, and with the expanded strategic interests that arise

from the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative. In the future, this may lead to greater Chinese involvement

in the region, as long as it remains within the ‘Five Principles’ framework.

Bibliography

1. Cable. V and Ferdinand. P, (1994), ‘China as an Economic Giant: Threat or

Opportunity?’, International Affairs, 70:2, pp 243-261.

2. Chaziza. M, (2016), ‘China’s Middle East Policy: The ISIS Factor’, Middle East

Policy, 23:1, pp 25-33.

3. Chung. C, (2009), ‘The “Good Neighbour Policy” in the Context of China’s Foreign

Relations’, China: An International Journal, 7:1, pp 107-123.

4. Energy Information Administration, (2015), ‘China Oil Imports’, EIA, 14th May,

(online), Available at: https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis.cfm?iso=CHN,

last accessed: 30th April 2016.

5. Fifield. R, (1958), ‘The Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence’, The American

Journal of International Law, 52:3, pp 504-510.

6. Gertz. B, (2016), ‘China May Enter the War Against ISIS’, Washington Times, 13th

January, (online), Available at:

http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2016/Jan/13/inside-ring-china-may-join-

russia-war-against-isla/, last accessed: 30th April 2016.

7. Hao. S, (2011), ‘China’s Positions and Interests in the South China Sea: A Rational

Choice in its Co-operative Policies’, Center for Strategic and International Studies,

pp 1-12.

8. Hao. Y and Zhai. Z, (1990),’China’s Decision to Enter the Korean War: History

Revisited’, The China Quarterly, 121, pp 94-115.

Ewen Dymott – University of Bristol

8

9. Hong. X, (2014), ‘The Chair’s Summary of the Colloquium on “The Five Principles

of Peaceful Coexistence and the Development of International Law” Held in Beijing

on May 27, 2014’ Chinese Journal of International Law, 13, pp 501-505.

10. Hunwick. R, (2014), ‘A Nervous China Is ‘Interested’ in a Possible Role in the Fight

against ISIS’, Business Insider, 22nd September, (online), Available at:

http://www.businessinsider.com/robert-foyle-hunwick-china-is-interested-in-against-

isis-2014-9?IR=T, last accessed: 30th April 2016.

11. Irish. J, (2016), ‘The World’s Largest Military Will Not Join the Fight Against ISIS’

Business Insider, 12th February, (online), Available at:

http://uk.businessinsider.com/r-china-rules-out-joining-anti-terrorism-coalitions-says-

helping-iraq-2016-2?r=US&IR=T, last accessed: 30th April 2016.

12. Jiabao. W (2004), ‘Speech by Wen Jiabao, Premier of the State Council of the

People’s Republic of China, at a rally commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Five

Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence’, Chinese Journal of International Law, 3, pp

363-368.

13. Juan. D, (2014), ‘Iraq Crisis May Change China’s Oil Suppliers’, China Daily, 17th

June, (online), Available at: http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/2014-

06/17/content_17595493.htm, last accessed: 30th April 2016.

14. Kao. L, (1957), ‘China and Panch Shila’, People’s China, 14:10.

15. Lowy Institute, (2016), ‘South China Sea: Conflicting Claims and Tensions’, Lowy

Institute for International Policy, (online), Available at:

http://www.lowyinstitute.org/issues/south-china-sea, last accessed: 1st May 2016.

16. Martina. M, (2014), ‘China Urges Central Asian Neighbours to Step Up Extremism

Fight’, Reuters, 15th December, (online), Available at:

http://af.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idAFKBN0JT0UR20141215, last accessed

30th April 2016.

17. Mertha. A, (2011), The Journal of Asian Studies, 70:1, pp 212-214.

18. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, (2015), ‘People’s

Daily: China’s Sovereignty Over South China Sea Islands Brooks No Denial’, 16th

December, (online), Available at:

http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/nhwt/t1324812.shtml, last

accessed: 1st May 2016.

19. Minnick. W, (2015), ‘China’s ‘One Belt One Road’ Strategy’, Defence News, 12th

April, (online), Available at:

http://www.defensenews.com/story/defense/2015/04/11/taiwan-china-one-belt-one-

road-strategy/25353561/, last accessed, 30th April 2016.

20. Nataraj. G & Sekhani. R, (2015), ‘China’s One Belt One Road: An Indian

Perspective’, Economic and Political Weekly, 50:49, pp 67-71.

21. Nehru. J, (1957), Letter to Russell Fifield from Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

22. Ng. T, (2014), ‘Xinjiang Militants Being Trained in Syria and Iraq, Says Special

Chinese Envoy’, South China Morning Post, 28th July, (online), Available at:

http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1561136/china-says-xinjiang-extremists-

may-be-fighting-middle-east, last accessed: 30th April 2016

23. Patranobis. S, (2014), ‘ISIS Training Xinjiang Militants: Chinese Media’, Hindustan

Times, 23rd September, (online), Available at:

Ewen Dymott – University of Bristol

9

http://www.hindustantimes.com/world/isis-training-xinjiang-militants-chinese-

media/story-ySeckrU4t0Hr9F4p2M4xuN.html, last accessed: 30th April 2016.

24. Richardson. S, (2009), China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful

Coexistence, New York: Columbia University Press.

25. Roberts. D, (2014), ‘Iraq Crisis Threatens Chinese Oil Investments’, Bloomberg, 17th

June, (online), Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-06-

17/iraq-crisis-threatens-chinese-oil-investments, last accessed: 30th April 2016.

26. Robinson. T, (1995), ‘Chinese Foreign Policy from the 1940s to the 1990s’, in

Robinson. T & Shambaugh. D, Chinese Foreign Policy: Theory and Practise, Oxford:

Clarendon Press, pp 555-602.

27. Roy. D, (1996), ‘The ‘China Threat’ Issue: Major Arguments’, Asian Survey, 36:8, pp

758-771.

28. Ruan. Z, (2014), ‘What Kind of Neighbourhood Will China Build?’, China

International Studies, 45, pp 25-50.

29. Shambaugh. D, (2003), ‘China and the Korean peninsula: Playing for the long term’,

The Washington Quarterly, 26:2, pp 43-56.

30. State Council, (2015), ‘Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic

Belt and Twenty-First Century Maritime Silk Road’, Xinhua, 28th March, (online),

Available at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2015-03/28/c_134105858.htm,

last accessed: 30th April 2016.

31. Strategic Comments, (2015), ‘China’s Ambitious Silk Road Vision’, Strategic

Comments, 21:6, pp 4-5.

32. Summers. T, (2016), ‘China’s ‘New Silk Roads’: Sub-National Regions and

Networks of Global Political Economy’, Third World Quarterly, pp 1-16.

33. Turner. O, (2016), ‘The motives behind Beijing’s South China Sea expansion’,

Southeast Asia Globe, 12th April, (online), Available at: http://sea-globe.com/motives-

behind-beijing-south-china-sea-expansion/, last accessed: 1st May 2016.

34. Xinhua, (2013), ‘Xi Suggests China, C. Asia Build Silk Road Economic Belt’,

Xinhua, 7th September, (online), Available at:

http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-09/07/c_132700695.htm, last accessed:

30th April 2016.

35. Xinhua, (2015), ‘The Belt and Road’, Xinhua Finance Agency, (online), Available at:

http://en.xinfinance.com/html/obaor/, last accessed: 30th April 2016.

36. Zambelis. C, (2013), ‘China’s Iraq Oil Strategy Comes into Sharper Focus’, China

Brief, 13:10, pp 10-13.

37. Zhenmin. L, (2014), ‘Following the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence and

Jointly Building a Community of Common Destiny’, Chinese Journal of International

Law, 13, pp 477-480.