Charles 'Lee' Leonidas 'Doc' Cooke

Transcript of Charles 'Lee' Leonidas 'Doc' Cooke

Charles ‘Lee’ Leonidas ‘Doc’ Cooke (Band details August 1922 to January 1924)

Introduction: Details about Charles ‘Lee’ Leonidas ‘Doc’ Cooke’s musical doings are not easy to unearth and biographical information found in jazz magazines/books does not seem to have appeared in a thorough collected form. A recent biographical book, “Harlem Renaissance Lives” by Gates/Higginbotham is listing a rather comprehensive Cooke story - yet one has to carry out quite a research to dig out some real facts as to his various band personnels. Cooke deserves a lot more recognition in the jazz annals for being an excellent and important band leader - his recordings are only vaguely regarded, although one gets a fine impression of some of the great but less well-documented jazzmen. Even if part of the music may be categorized as novelty, many sides are swinging hot with high level performances. Maybe not progressive or trailblazing, yet Cooke had an excellent and constantly improving band from 1922-30. To direct more interest to the Cooke saga, some information/facts/questions/conclusions are stated below - in the hope that a wider debate may clarify the situation. Surely there must be other references (from way back) than the ones piled together here. Hopefully, with reporting from a number of collectors, it shall be possible to establish a more detailed picture of this fine gentleman, “Doc” Cook as he was known most of the time, his compositions/arrangements, and his orchestras.

-o0o-

Paul Eduard Miller (ca. 1941-42): “Charles L. Cooke. Arranger, composer. Born September 3, 1891, Louisville, Kentucky. Obtained his musical education at the Chicago Musical College (Bachelor of Music Degree, 1922) and at the Chicago College of Music (Doctor of Music Degree, 1926). Began professional career in Detroit 1909, where he was associated with J. A. Remick Music Company.” Gates/Higginbotham 2009 (listing recordings): “Why his last name was given in truncated form is not known; it may have originated as an error and become too troublesome to correct.” DoctorJazzWeb, Brian Goggin 2007, and also Gates/Higginbotham 2009: “Charles Lee Cooke was born 3rd September 1887, as indicated on the WWI draft registration card, and while most reference works agree with his birthday, they give the year as 1891. The 1920 U.S. Census entry indicates a birth year of 1888, while the 1930 entry supports the 1891 year of birth. In addition, his WWII draft registration card also gives the date of 3rd September 1891 and notes his middle name as Leonidas. Cooke attended public schools in Louisville and Detroit, Michigan. He received early music tuition from his mother, a music teacher and later learned piano and theory with other teachers. Working as a staff composer at Detroit publishing houses (already before 1910) for a time, he moved on to Chicago later and organised his own band there. An obviously learned man where music was concerned, Cooke . . . studied under composer Louis Victor Saar and Chicago Symphony Orchestra programme annotator Felix Borowski for the latter two qualifications.”

Copyright 1912 Copyright 1914, Jerome Remick. Copyright 1915 (no lyrics)

Inside “A Weary Blue”, no lyrics.

Mike Schwimmer recut

As by Charles S.(?) Cooke (copyright 1918) Copyright 1913 William H. “Billy” Butler (interview with Gene Fernett ca. 1966): “Charles L. ‘Doc’ Cooke (he later dropped the ‘e’ from his last name) began composing music when he was eight years old. He organized an 8-piece combo in Louisville when he was only 15. Soon after he had turned 18, he and his parents moved to Detroit, where he played in Fred Stone’s Orchestra and, later, in Ben Shook’s band. As a manager with Shook (who had a contract to furnish all the orchestras for Riverview Park, Chicago), Cook got his first opportunity to lead a large band.”

Gates/Higginbotham 2009: Cooke scored an early hit in 1918, when his song “I’ve Got the Blue Ridge Blues” (words by Charles Mason; co-composed by Richard Mason) was included in ‘Sinbad’, a successful show featuring a young Al Jolson. . . . by 1920 Cooke was based in Chicago, where he quickly became a leading theatrical and cabaret bandleader and worked as musical director at Riverside Park” DoctorJazzWeb, Brian Gogging 2007: Cooke’s WWI Draft Registration Card, 5th June 1917:

It appears from the draft registration card that Charles Cooke, at this point (June 1917), is living at 451 Twelfth Street, Detroit, Michigan. That he is a musician, employed by Benjamin L. Shook engaged at Griswold Hotel. That he is of Ethiopian race, is married, and has one child. That he is tall and slender with brown eyes and black hair. He signed as ‘Charles Lee Cooke’. .

Jazz piano solo, 1919. Composed by van Alstyne, compiled and arranged by Chas. L. Cooke

Arranged by Charles L. Cooke, 1922 Arranged by Charles L. Cooke, 1923 Olle Helander/”Jazzens Väg”, c. 1945, pages 110-111 (translated): ”During 1918-21 Cook was leader of the music at Riverview Park, an amusement park north of Western Avenue and West Belmont Avenue . . . right before Cook took over from Charlie Elgar at the Dreamland, he had been playing for a few months at Riverview Dance Hall . . .” - the band personnel stated is: Axe Turner. Graham. Garland. Noone. Poston. Pasquall. Spaulding. Cook (organ). Shelby. Reynaud. Green. When the Dreamland engagement started, Keppard joined. Note that Clifford King is not mentioned - so apparently King was not at the Riverview Dance Hall, but joined at the beginning of the Dreamland engagement which would sustain that Cooke hired King from Elgar when the latter left the Dreamland. If Shelby was really at the Riverview Dance Hall (beginning 1918), why would Stanley Wilson have been the banjo player at the August 1922 start at the Dreamland (as per Pasquall), when Shelby is definitively still seen in the late 1923 poster photos? Clifford “Klarinet” King was so named to distinguish him from the trumpet/cornet player Clifford King. Gates/Higgin-botham 2009 state the name of the amusement park to be ‘Riverside Park’ - seemingly incorrect.

James K. Williams, Storyville 2002-03, page 119: “ Summer 1920, Noone quit Oliver’s Creole Band and joined Charles “Doc” Cooke’s Orchestra . . . sometimes doubling with his own and other groups at Chicago clubs.” DoctorJazzWeb / Brian Goggin: “Even though Cooke had been a published ragtime composer for several years, it was as leader of his own band that . . . he is best remembered. The Dreamland catered for high class patrons who enjoyed the good food and alcohol served there in addition to the music. . . . His Dreamland Orchestra was a large one for the time, with up to sixteen or more musicians and was very popular, one newspaper headlining “Doc Cook’s Dreamland Ballroom’s Orchestra Breaks Records at the Dreamland”. Although a pianist, Cooke apparently didn’t feature himself on that instrument, choosing instead to conduct, take care of musical direction duties and play the organ.” Pete Whelan’s cover notes (Herwin LP101) indicate that Dreamland Café and Harmon’s Dreamland is the same venue - which is not the case. Don Pasquall (interview with Driggs/Hagert, ca. 1950s-1964, printed in Jazz Journal 1964, April/May): “Later in 1921, I went to Chicago to study at the Conservatory. On the South Side at the Paradise (35th and Calumet), Glover Compton’s band with Jimmie Noone was playing, and at Dreamland (Café) was Mae Brady’s (Bradley?) with Freddy Keppard (and Bob Shoffner, Junie Cobb, and Eddie South). Carroll Dickerson was at the Sunset Café with Andrew Hilaire. But the greatest bands around Chicago at the time were Charlie Elgar’s and Doc Cook’s. Elgar was out on the West Side at Harmon’s Dreamland where he featured Clifford King. King was later known publicly as “Klarinet King” and was a very excellent musician who also had many tricks – one was playing two horns at the same time. His best stunt was holding a note indefinitely without seeming to take a breath (circular breath control method) . . . Louis (Armstrong) wanted me to join the band (Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band), but I thought I had better prospects elsewhere. As a matter of fact, by 1922 I had made quite a reputation as a C-melody sax player on the South Side and was much in demand. Paddy Harmon – his real name was Patrick – who owned Harmon’s Dreamland, used to lease the Municipal Pier from the city during the summer months. The pier was a magnificent piece of architecture, all glass enclosed, which jutted right out over Lake Michigan. He would close the Dreamland in June and open the pier until mid-August and then return to the Dreamland. When Elgar’s band concluded its contract, Doc Cook, whose band had been playing at the Riverview Ballroom, opened the Dreamland at the end of the summer (1922). In the reed section were Clifford King and Jimmie Noone both featured on clarinet. Joe Poston was mainly on alto sax and I was playing tenor sax and later acted as assistant conductor. We all doubled, Jimmie Noone sometimes played soprano sax, but he didn’t take to it. I had four horns and King had five or six. Fred “Cat” Garland was on trombone. Elwood Graham and Ax Turner were on trumpets, and Freddy Keppard later replaced Turner. Keppard really gave the band a lift and then we went to town. Later, Andrew Hilaire and Johnny St. Cyr joined the band. Doc Cook seldom wrote out any special parts for Freddy Keppard but would just give him his head and while we were playing the arrangements, Keppard would do anything he wanted. Paddy Harmon was also the maker of the Harmon mute (another report has it that Harmon patented the mute and named it after himself, but that it was invented/constructed by Charlie Elgar’s trumpet player Joe Sudler). Before that all the legitimate players used the standard metal mute like the one Joe Oliver used to get special effects with. Harmon had his mute developed by a man named Schlossenburg and the first people to try it out were Keppard and Graham of Cook’s band.” Gates/Higginbotham 2009: “Cooke’s ensembles were renowned for their technical expertise, and the section players were required to be fully trained reading musicians. Cooke may have compromised slightly in the interest of featuring hot soloists, although the two most famous of these, the clarinetist Noone and the cornetist Freddie Keppard, both from New Orleans, probably would not have been hired if they could play only by ear”.

Preston Jackson (ex Ramsey/Chicago Doc. 1944): “I came to Chicago in 1917 . . . Perez was in Chicago at the Royal Gardens with Jimmy Noone, Paul Barbarin, Eddie Venson, Lottie Taylor, and Bill Johnson. For a while, Keppard played the De Luxe. Well, compare him to Perez, who was the best teacher - he read very well. Keppard was just the opposite, all barrelhouse. He played two or three notes a bar, and was called King Keppard. He was tops. He didn’t have a lot of execution . . . .” Jelly Roll Morton (same source): “ . . I never heard a man that could beat Keppard - his reach was so exceptional, both high and low, with all degrees of power, great imagination, and more tone than anybody. Any little place in the music that didn’t have any notes on, he would fill right up. He really couldn’t read a note. Liked to hear the tune first, because he didn’t want to admit he couldn’t read. He frequently found excuses; he would be having valve trouble, fingering the valves, shaking the instrument, spitting it out; all the while he would be listening. Somebody would bawl him out and he would say, “Go ahead, I’ll play my part!” Next time, he would pick up his horn and play right through the number.”

Doc Cook (courtesy Billy Butler) William H. “Billy” Butler (interview with Gene Fernett ca. 1966):”Cook was an excellent organist and pianist. Gee, he was a wonderful man and a tremendous arranger. When I joined him in Chicago, he already had an office in the State-Lake Building, and was doing all the overtures for important theatres, and a lot of orchestrations that were published widely. He had a doctorate from American Conservatory – one of the first negroes to receive one. When he started his group in Chicago (that was after he had the Detroit group he called ‘Cookie and his Ginger Snaps’), he called the outfit ‘Charlie Cook and his 14 Doctors of Syncopation’!” Paul Eduard Miller (ca. 1941-42): “Cook migrated to Chicago in 1918 where he held the contract for all musicians working at Riverview Park (35 to 74 in number). He remained in this job until 1922 when he organized and headed a 16-piece orchestra at Harmon’s Dreamland Ballroom, where he remained for five years. His band then moved to White City Ballroom (1927-30). It is these 12 years of activity as a bandleader that firmly established Cooke’s position in jazz music. Simultaneously with his activities as leader, he wrote and arranged for Remick and Hugo Riesenfeld, and other New York publishers.” Happy Caldwell, Storyville 99/1982, page 85: “ . . .I played clarinet, although I did have an alto sax. None of us bothered much with saxes then. In fact, I lent my sax to Johnny Dodds and he kept it a whole year before he gave it back - he used it on a record date once. But we were all clarinet players then; Johnny Dodds, Buster Bailey, Clifford King - he was a very versatile musician, and played all the reeds, including bassoon. Cliff was in Charlie’s band - he (Cooke) had a beautiful band at that time, 17 pieces. Elrick (sic) Graham on trumpet, Shoffner, Spaulding, Jimmy Noone, Freddie Keppard. Freddie Keppard was the “Iron Man” of the trumpet.” Laurie Wright, “King Oliver”, 1987: On 19 May 1923, the Chicago Defender carried an advert: “Midnight May Ball, Local 208, Saturday May 26, 1923 at Eighth Regiment Armory, 35th and Giles Ave., Chi; midnight. Music furnished by Chicago’s Famous “40” Courtesy of: Clarence M. Jones, Moulin Rouge. Erskine Tate, Vendome Theater. Joseph Oliver, Royal Gardens (actually RG had changed name to Lincoln Gardens). Charles L. Cooke, Harmon’s Dreamland. 40 pieces - proceeds for benefit of “Building Improvement Plan”. Driggs/Lewine (Black Beauty, White Heat) 1982, state (on page 53) that trumpeter Jimmy Wade worked briefly with Doc Cook. Chilton confirms and suppose year to be c. 1922. McCarthy, Big Band Jazz 1974, agrees. Wade is not seen in any photo of the Cook organization. Ramsey/Smith (Jazzmen, 1939) have it (on page 284) that Sidney Bechet was with Cook’s Dreamland Orchestra - must be confused with Will Marion Cook’s Orchestra. McCarthy has it (page 21) that Pasquall was with Charlie Elgar in 1922 before he joined Cooke - which doesn’t seem possible at all. On page 23, McCarthy states: “Keppard was in the (Cooke) band for two years from the autumn of 1922, except for a brief spell with Erskine Tate.” Quite a number of reports, mainly on the internet but also Chilton, have included Zutty Singleton in Cook’s personnel - so far it has not been possible to pinpoint a certain period, yet during late 1926 or first three months of 1927 (Zutty

Singleton was with Dave Peyton in April 1927) might be possible. Andrew Hilaire joined Cooke in 1923 and did not leave until the band broke up in 1930 - but Hilaire’s TB sickness may have necessitated a substitute drummer now and then which would also explain why Jimmy Bertrand may have been hired for a while. Some sources have it that Cook replaced Elgar at the Dreamland in 1921. There is existing a photo of Charles A. Elgar’s Dreamland and Municipal Pier Orchestra (13 men altogether) dated (by hand) November 11, 1921 – although not being a conclusive evidence, it seems that on this account it may safely be assumed that Cook did not replace Elgar until 1922 (and Pasquall states that Cook took over 1922 after the Municipal Pier engagement, which would then be mid-August 1922). Likely, at the same time, Cook hired Robert William Shelby and Clifford King (ex Elgar).

Above: Cook and His Dreamland Orchestra (no inverted commas used for Cook’s last name) at Paddy Harmon’s Dreamland, South State and 35th (sic), Chicago (this photo ex Black Beauty, White Heat/1982, page 54, source AC(?), year 1923, no details as to personnel. Since Hilaire/St. Cyr/Anderson are not shown, and Keppard/Wilson/Newton are not present, 1923 would in fact be the likely year for this photo - but it could also be right at the beginning of the Dreamland engagement, late summer 1922. Personnel from left, starting back row, is recognized as: Anthony/Antonio/Antonia/”Tony” J. Spaulding, piano. Unknown, xylophone/marimba/glockenspiel/bells. Bert W. Greene/Green, dms. Robert William “Bill” Shelby, bjo/gtr. Next row: R. Elwood Graham, cor. Unknown (still Ax Turner? - doesn’t look like Wade or Shoffner), cor. Fred “Crazy Cat” Garland, trb. Rudolph “Sudie”/“Zutty” Reynaud/ Renaud, brass bass. Next row: William Clifford “Klarinet” King, reeds. Joseph E. “Doc”/ ”Joe” Poston, reeds. Jerome Don Pasquall, reeds and asst. cond. James “Jimmy”/”Jimmie” Noone, clt. Next row: Jimmy/James/Jasper Bell, vln (left). Unknown, vln (right). Front: Charles L. “Doc” Cook, organ. Why isn’t there any music stands except for the unknown percussionist? According to Milt Hinton, Spaulding was gay (which may account for the sometimes used first name “Antonia”) - had a big scar across his face from an automobile accident, and was much older than Hinton himself. One would think that had Keppard been even remotely associated with the Cook band at this time, then he would also have been posing for the photo – his authority, reputation, and playing certainly were assets to be publicized. Although Chilton also states that Keppard joined Cook in autumn 1922, the Pasquall information doesn’t give a definitive clue as to the exact date for Keppard’s commencement. Otherwise this photo might have been shot exactly during the short spell in 1923 when Keppard was reportedly with Erskine Tate (if ever he was a firm member of Tate’s band at this point? Tate augmented his band personnels for various occasions and from day to day, so Keppard could have been hired for the recording purpose only. In Chicago Defender Mar 3, 1923, it is, however, reported + advertised that Keppard was in Ollie Powers’ Syncopators at the opening of Paradise Gardens at midnight March 2 - which he could probably have been even if he was with Cook also). If this is the case (1923), it could probably not be Ax Turner in the second trumpet chair - he would have left the band at this point. Chicago Defender, March 10, 1923, reports personnel of Tate’s band which includes two cornets: James Tate and “King” Keppard. In Chicago Defender, September 1, 1923, there is an ad for the Tate/Keppard Okeh 4907 (recorded June 23, 1923) with a photo of the band showing 12 men. Since there is only one trumpet man visible, it is not likely to be Keppard?

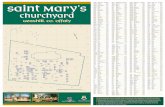

Earl Hines / World of Earl Hines, page 35: “ . . . some of the great stars of the day used to appear at the Grand, where Dave Peyton played piano in just a small group at first. Musicians like Freddie Keppard . . . were all gigging around, playing dances and in and out of these theatres. Erskine Tate was across the street at the Vendome Theatre, where they showed movies - no sound - and had live musicians . . .” In Chicago DEFENDER, September 17, 1927, one Jimmy Bell is listed as being director of the Metropolitan theater orchestra - is he identical with Cook’s violinist? Cook probably took over Shelby from Elgar at the late summer shift in 1922. Since Shelby is also in the 1924 Cook band photo, he must be the banjo/guitar player in the 1923 photo (a bit difficult to verify exactly, but it looks like him). Shelby was back with Elgar in 1926, but probably left Cook at the beginning of 1924 or maybe even some weeks earlier. Anyway, the banjo player in the 1923 photo is definitely not looking like Stanley Wilson. Bell has been identified via the photo of Elgar’s Creole Orchestra (6 men) at Fountain Inn, Chicago (some sources state ca. 1913-15, others ca. 1915-17). However, Stanley “Stan” Wilson also played violin, and looked quite alike Jimmy Bell . . . yet Stanley Wilson seems to have been employed with Jimmy Wade constantly from 1923-27, except that he was with Dave Peyton’s Symphonic Syncopators sometime 1924/25 at the Plantation (before Oliver took over). Mark Berresford, Retrieval ca. 1999 / James K. Williams, Storyville 2002-03, page 119: “The Dreamland was a cavernous, barnlike dance hall/building (which also functioned as a roller rink) located beneath the Elevated Railroad tracks at the junction of Paulina and Van Buren streets on Chicago’s West Side (a site which today is the north embankment of the Eisenhower Expressway), and catered to an exclusively white audience / a mostly Jewish & Italian audience, being about equidistant from what is now called “Little Italy” and a nearby Jewish neighborhood.” Over the years there has been much confusion about the Dreamland, as there were two such-named venues in Chicago – the other being a ‘black and tan’ cabaret on State Street in Chicago’s infamous South Side, owned by African American businessman Bill Bottoms.” (Actually it was – acc. to Charles Elgar’s recollection - owned by Virgil Williams and managed by Bill Bottoms and known as Bill Bottom’s Dreamland Gardens.) Chilton: “Poston joined in 1922, Pasquall in 1922, Johnny St. Cyr in January 1924, Hilaire in 1924.” Judging from several assertions, it seems that the clientele frequenting the Dreamland was white people.Miller/Hoefer, 1946, Esquire’s Jazz Book, page 23: “During 1924 and 1925 Doc Cook, Erskine Tate, Sammy Stewart, Jimmie Wade, and Clarence Jones continued to pace the entire field. Doc Cook and his Doctors of Syncopation delivered good jazz to the white patrons of Dreamland Ballroom.”

“Cook” and his Dreamland Orchestra (note inverted commas), poster studio photos by Bloom Photographers, State-Lake Building (where also Cook had his office), Chicago (this black and white photo ex Pictorial History of Jazz/1955, page 36, source George Hoefer, year not stated. No source for the color photo). Since Pasquall, who left during summer 1924, is included, these photos would very likely not have been taken later than springtime 1924. Since Shelby and Greene are still with the band, and St. Cyr and Hilaire have enrolled, it might certainly also have been taken right at the beginning of January 1924, or even sometime before the end of 1923. A photo of above poster is deposited at Chicago Woodson Regional Library, Harsh Research Collection - donated by a William McBride (deceased). As per the library registration, Mr. McBride informed that the poster dated from 1923. Research reveals that he actually gave the information “c. 1923”. No further details are available except that the photograph-measure corresponds exactly with that of the poster print reproduced in “Pictorial History of Jazz”. Latest research reveals that the Chicago Public Library Digital Collection (Woodson Regional Library / Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection / William McBride Papers 007) is holding the above original. Although photographer/artist is listed to be unknown (the name Bloom Photographers, State-Lake Building appears from poster), however, it appears that date of original is 1923!! (McBride himself apparently source of information).

Conclusive evidence seems now (July 2014) to have come to light, since in an interview printed in The JazzFinder/Playback, January 1949, St. Cyr states that he joined Cook at the beginning of December 1923!!! So all in, it is more than likely that the poster and band photo was made in December 1923.

Above: “Cook” and his Dreamland Orchestra, studio photo by Bloom Photographers, State-Lake Building, Chicago (this photo ex Pictorial History of Jazz/1958, page 36, source George Hoefer, year not stated). Personnel from left (identified via the Dreamland poster): Bert W. Green, drums. Fred “Crazy Cat”/”Cat” Garland. Andrew “Andy” Henry Hilaire. Fred “Freddie” Keppard. R. Elwood Graham. Rudolph “Sudie”/ “Zutty” Reynaud/Renaud, brass bass. Kenneth “Ken” Anderson, piano. Jerome Don Pasquall. Jimmy/Jimmie Noone. Charles L. “Doc” Cook. Joseph E. “Joe”/ ”Doc” Poston. Robert William Shelby, banjo. John “Johnny” Alexander St. Cyr, six-string banjo. William Clifford “Klarinet” King. Hilaire’s last name is sometimes spelled Hillaire, for instance in the Dreamland picture poster. On the later Columbia labels, his name is spelled Hilaire which is definitively correct.

Same photo (ex Swing Out/1970, page 27, source Elwood Graham, stating photo was taken in 1924). Elwood Graham’s identification is exactly the same as for the Pictorial History-photo. The dark background spot, between Hilaire and Renaud, is not a retouch but a shadow from the brass bass bell piece caused by a light bulb in the left ceiling corner (see full sized photo from the Cook Dreamland poster).

Same photo (ex Esquire’s 1944 Year Book of the Jazz Scene, page 13, year taken 1924 as per source George Hoefer). Miller’s identification of musicians equals Elwood Graham’s opinion.

Same photo (ex Record Changer July-August 1951, page 20. Only general credits and sources are mentioned in foreword by Harriet Janis/Rudi Blesh/Herb Thrune/Harry Crawford. No year of photo stated, and just a few band member names referred. However, this photo is seemingly rather uncropped - interestingly, a bass saxophone is seen to the far left; was it ever played in the recordings? Several other bands, such as NORK, had their photos taken in the Bloom Studio). Don Pasquall (interview with Driggs/Hagert, ca. 1950s-1964): “Around the winter of 1924 we went out to Richmond, Indiana, to make our first (sic) records for Gennett. Since it was our first time and since recording hadn’t reached the state of perfection that it has today, we had no way of knowing that we weren’t using the best techniques. As it was, I

think we tried to do too many sides. We made several tests, and I think, three masters each of six different tunes. By the end of the afternoon, everybody was missing notes and making mistakes. The records didn’t come out well and we were all disappointed with them. I remember Noone said, “I don’t ever want to hear them anymore.” I left Cook that year (summer 1924) and went East to Boston to study serious music at New England Conservatory for three years until I graduated in 1927 with high honours. (Pasquall relates that he spent time during summer 1925 in New York only, not Chicago).” (It is worth noting Pasquall’s expression “Since it was our first time and since recording . . .” - if it was indeed these musicians first time in a recording studio, then it is quite logical that Jimmy Noone denied his presence on the King Oliver 1923 Columbia sides!! Yet St. Cyr had recorded with King Oliver, Keppard with Tate, and Noone is alleged to be on the Ollie Powers sides, all made in 1923 - but it certainly does not sound like Noone on the Oliver Columbias or Powers Paramounts). Walter C. Allen, Hendersonia, page 214, 1973: ” . . .Pasquall working for Doc Cooke for several years. The Chicago DEFENDER of May 15, 1926, reported that he had left Cooke and gone to Boston to study at the New England Conservatory of Music.” Is this a misprint? 1926 couldn’t be correct since Pasquall very well remembered having studied for three years and graduating June 27, 1927. The Bloom studio photos must have been taken around the time of the band’s Gennett session recorded in Richmond, Indiana, January 21, 1924 (Berresford has August for the Gennett session in his Retrieval notes, which must be an unintentional slip). So: Is it the same band members in the photo and on the Gennett sides?

Delaunay’s discography 1938. Brunswick 4338 (High Fever) is actually ColumbiaE 4338 labeled COOK and HIS DREAMLAND ORCHESTRA.

Delaunay’s discography 1943. Brunswick 4338 (High Fever) is actually ColumbiaE 4338 labeled COOK and HIS DREAMLAND ORCHESTRA.

Delaunay’s discography 1948. ColumbiaE 4338 (High Fever) is actually labeled COOK and HIS DREAMLAND ORCHESTRA.

As per today’s discographies and LP/CD notes, the below discographical ‘facts’ are usually listed - strangely unquestioned since the dawn of time. Is it due to a definitive and reliable source? It is not, indeed - instead it is just a mystery why no one has pointed out several misleadings. Jerome Don Pasquall (Jazz Journal 1964, Driggs/Hagerts interviews) remembered that he joined Cook right when the Dreamland Ballroom engagement started in the summer (August) of 1922, and as per the article, he gave the following personnel for that occasion: Elwood Graham, Ax Turner (trumpet) later replaced by Freddie Keppard, Fred Garland, Jimmie Noone, Clifford King, Joe Poston, himself, Jimmy Bell (violin only), Anthony Spaulding, Stanley Wilson (banjo), Bill Newton, and Bert Green – and one would certainly assume that (considering the source) this is the very information making up the basis for today’s discographical personnel. In fact, Pasquall himself is not naming the rhythm section members by name in his account - but a ‘band personnels’ listing is added to Pasquall’s story. Although it is stated that Pasquall has confirmed the Cook band personnel (also for the Gennett recording session), he might in fact have confirmed Frank Driggs’ suggestion for a personnel. Driggs probably had his information from the Walter C. Allen Henderson-project, and Walter Allen seems to have adopted the personnel put forward by Delaunay. So, if we go all the way back to Delaunay’s Hot Discography of the 30’ties, Delaunay has exactly the same personnel - that is, after the enrolment of Keppard - and Stanley Wilson for some reason being omitted. In the Irish “Hot Notes” magazine, May/June 1947, Walter C. Allen writes about Keppard: “ . . . (Keppard) then joined Doc Cook at Harmon’s Dreamland Ballroom in the fall of 1921, staying until the fall of 1924, when he was replaced by George Mitchell.” - 1921, of course, being the wrong year. Allen then proceeds to lay down a discography for Keppard, and arrives at exactly the same personnel as by Delaunay and almost the same as by Pasquall. 17 years prior to the Pasquall quote in the Jazz Journal article. The same thing happens in “Disc-Counter”, April 1949. In “Jazz Music”, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1954, Normand Turner-Rowles confirms this personnel and even establishes the mistake that “So This Is Venice”, Edison Bell Winner 4056, by Diplomat Novelty Orchestra, was by the Cook band (it is actually a Harry Reser unit). NT-R credits Walter C. Allen. It is unlikely that the band personnel would not change at all from the start in August 1922 until the recording in January 1924. The question is whether Pasquall’s memory is exact - he might actually have confirmed Wilson and Newton because they were with Cook in 1929, the year when Pasquall rejoined Cook. During his first stay with Cook, Pasquall himself is seen together with Shelby and Renaud in all three photos (and in the latest two St. Cyr and Hilaire are also present, while another assumed candidate for the drums, Fred Hall, is never shown). In fact/unfortunately Pasquall himself does not comment on the recording personnel or the personnel shown in the studio photo (which is also printed together with the 1964 Driggs/Hagert/JJ article). Which source has provided the name of Fred Hall (drums)? And who is he? Is he supposed to be Alfred “Tubby” Hall? COOK’S DREAMLAND ORCHESTRA: Doc Cook, dir. Freddie Keppard, cnt. Elwood Graham, cnt. Fred Garland, trb. Jimmie Noone, clt. Clifford King, alt. Joe Poston, alt. Jerome Pasquall, ten. Jimmy Bell, vln. Tony Spaulding, pno. Stan Wilson, bjo. Bill Newton, bb. Fred Hall or Bert Greene, dms.

Richmond, Indiana, January 21, 1924 11727-B Scissor Grinder Joe Gennett 5374, Silvertone 4044 11728- Lonely Little Wallflower Gennett 5373, Silvertone 4045 11729-A-B So This Is Venice Gennett 5360 11730- Moanful Man Gennett 5373, Silvertone 4045 11731- The Memphis Maybe Man Gennett 5374, Silvertone 4044 11732-A-B The One I Love Belongs To Somebody Else Gennett 5360 Well then, what is it possible to hear in the recordings?: In general 2 cornets and 1 trombone are audible. In general 4 reeds are audible, most distinctly in first chorus of 11729 (clarinet over 3 voiced saxes) and also first chorus of 11732. In general one pianist, one banjoist, one brass bass player, and one drummer. No violin or guitar audible. Altogether probably 12 men including Cook himself. 1. As per above studio photos, it could be assumed that Bert Green/Greene is the drummer – yet, it could also be Hilaire (see item 5 below). Glockenspiel is heard on 11727. Fred Hall is not (as a drummer) in any of the above photos, while Bert Greene is in all three of them. It is certainly worth noting Olle Helander/”Jazzens Väg”, c. 1945, pages 130-131-134 (translated): ” . . . Andrew Hilaire (was) with Carroll Dickerson’s Orchestra at Sunset Café, in 1923 replaced by Tubby Hall . . . . among drummers performing at the Dreamland Ballroom was the excellent Andrew Hilaire, to be heard with Charlie Cook’s Orchestra. He joined in 1923 (!!) after having been with Dickerson.” (During the war years, maybe even in the 30’ties, Helander corresponded with a number of early American jazzmen - so his information may come from firsthand sources). In the 1924 Dickerson band photo, it is definitively Tubby Hall on drums and not Hilaire. 2. It is not possible to hear a violin part at any time, so the question is whether Jimmy Bell is at all present? Or for that matter, at all a member of the band at this point – he is not in the Bloom Studio photos.

Bell had been with Elgar at the Fountain Inn, 63rd and Halstead, ca. 1913-1915 (probably also other engagements with Elgar), and was apparently with Cook in 1922-23. 3. As per the studio photos, isn’t Kenneth Anderson the obvious man for the piano stool? Why would Jimmy Bell or Anthony/Antonio/Antonia/”Tony” Spaulding be the likely piano candidates? The piano solo breaks are certainly not unlike the piano playing by Anderson on the later Okeh sides by Cookie’s Gingersnaps. Several newspaper clippings (Storyville 1996-97, page 241), however, prove that Spaulding must have left Cook sometime in 1923: “The dance team of Dave and Tressie toured for several years on the vaudeville circuits with their own “Syncopated Ginger Snaps”. A report in the Defender, November 10th, 1923, from Bloomington, Ill. , gives the personnel of the band: Porter LaMont, clt. Stanley Williams, sax/ldr. Jimmy Palo, sax. Anthony Spaulding, pno. Ed Williams, bjo. William Johnson, sbs. Raymond Greene, dms (all sic). By January 1924, when they were at the Palace Theater in Detroit, the band (acc. to Chicago Defender January 19, 1924) was Stanley Williams, sax/ldr. Jim Paloa, sax. June Clark, cnt. James Harris, trb. A. J. Spaulding, pno. James Harris, prob. sbs. John Lee, bjo. Raymond Green, dms (all sic). Consequently, Spaulding is out of the picture, and Kenneth Anderson must be the piano player. (By the way, Kenneth Anderson was originally an excellent trumpet player, studying 1917-19 at Englewood High, 6201 S. Stewart Avenue, Chicago. Some sources have it that he also played saxophone). 4. Vocal shouting during break in Noone’s clarinet solo on 11727: “Grind that thing, Joe!” and some sound effects imitating a grinder. Shouting could be by Poston, and sound effects by Hilaire. 5. Vocal shouting during two breaks at the beginning of 11731 – not the same voice as on 11727, this one in fact having the timbre of Andrew Hilaire’s voice. So after all, it is more than likely that Hilaire may have stepped in this early – he is in the Bloom Studio photos, and the cymbals are played not unlike the Hilaire trademark. 6. Slap-tongue baritone sax heard on 11727/11731/elsewhere. A baritone is in front of Pasquall in the Bloom photo. Some source once put forward that Pasquall never played baritone sax, but only bass saxophone - seems unlikely. 7. Clarinet soloist on 11730 sounds more convincing than Noone. This must be King featured all the way through in this arrangement. Probably a bass clarinet (King) is heard on 11729 (over three clarinets). A bass clarinet is seen in front of King in the studio photo (doesn’t look like a bassoon). 8. And most important: The banjo break on 11732 is pure and genuine St. Cyr style - general banjo accompaniment is very relaxed and have the familiar St. Cyr ring – although very poorly recorded it sounds very much like St. Cyr is present. At this time, could anyone else than St. Cyr have executed/invented such an excellent break? Judging from the photo personnels, and considering that Shelby was apparently with the band from the very start at the Dreamland, the logical candidate for the banjo position would have been Shelby. Shelby was a quite good section man displaying a floating touch, yet generating a completely different sound from his instrument compared to St. Cyr. Further Shelby did not seem able to execute solos/breaks of this elegant calibre (confer Elgar’s Victor sides, especially “When Jenny Does ..” – the Elgar recordings are in fact highly interesting music! But are disco personnels true?). St. Cyr seemingly terminated his job with Oliver at the end of 1923 to start with Cook January 1st,1924. Since it is uncertain exactly when Oliver disbanded late 1923, St. Cyr could even have left Oliver a month or so earlier. 9. Stanley Wilson probably did not get (back) with Cook until much later – anyway he is not in the Bloom photos, but he could be one of the violinists in the Dreamland photo 1923. Stanley Wilson was in fact a greatly skilled musician on violin/banjo/guitar, and did play fine and well constructed solos – but seems to have been employed with Jimmy Wade constantly from 1923-27, except that he was with Dave Peyton’s Symphonic Syncopators sometime 1924/25 at the Plantation (while Oliver was hired temporarily by Peyton until Oliver himself took over late February 1925). 10. It may seem likely that Cook reorganized his band as from January 1st, 1924 (and that, at this occasion, the grand photo poster was made up for marketing purposes) - maybe due to the recording contract with Gennett. All in all, one good reason for Robert Shelby and Bert Greene being with the band in early January 1924, were for them to ‘hand over’ their parts to their successors, and that would also explain why they are in the Bloom photos but did not assist at the Gennett session? OR: The Bloom photo session might have taken place even in December 1923, at a time when Hilaire/St. Cyr had already signed their contracts yet before they actually joined and Shelby/Greene actually left? As stated above, Helander has it that Hilaire joined sometime late 1923. Anderson was a well educated musician and probably did not have any problems catching on to the repertoire. 11. Can anyone explain why Bill Newton ended up in above listed personnel? Was that because he is on the later Columbias? 12. Further details: Correct orchestra label name according to the Gennett labels: Cook’s Dreamland Orch. Correct title of 11728 according to label: Lonely Little Wall Flower Correct title of 11732 according to label: The One I Love (Belongs To Somebody Else) Can anyone confirm other unknown takes?

Suggested corrected discographical details as per above findings: Cook’s Dreamland Orch. (Gennett) / COOK’S DREAMLAND ORCH. (Silvertone): Doc Cook, dir. Elwood Graham, 1. cnt. Freddie Keppard, 2. cnt. Fred Garland, trb. Jimmie Noone, clt. Clifford King, clt/bcl/alt. Joe Poston, clt/alt/poss. shouting. Jerome Pasquall, clt/ten/bar. Kenneth Anderson, pno. John St. Cyr, bjo. Rudolph Renaud, bb. Andrew Hilaire, dms/glockenspiel/vcl.

Richmond, Indiana, January 21, 1924 11727 SCISSOR GRINDER JOE Unissued 11727-a SCISSOR GRINDER JOE Unissued 11727-B SCISSOR GRINDER JOE (shouting poss. JP) Gennett 5374, Silvertone 4044 11728 Lonely Little Wall Flower Gennett 5373 11728 LONELY LITTLE WALL FLOWER Silvertone 4045 11728-a Lonely Little Wall Flower Unissued 11728-B Lonely Little Wall Flower Unissued 11729 SO THIS IS VENICE Unissued 11729-a SO THIS IS VENICE Gennett 5360 11729-B SO THIS IS VENICE Gennett 5360 11730 MOANFUL MAN Gennett 5373, Silvertone 4045 11730-a MOANFUL MAN Unissued 11730-B MOANFUL MAN Unissued 11731 THE MEMPHIS MAYBE MAN (shouting AH) Gennett 5374, Silvertone 4044 11731-a THE MEMPHIS MAYBE MAN Unissued 11731-B THE MEMPHIS MAYBE MAN Unissued 11732 THE ONE I LOVE (BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE) Unissued 11732-a THE ONE I LOVE (BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE) Gennett 5360 11732-B THE ONE I LOVE (BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE) Gennett 5360 NOTE: One issue of Gennett 5360 has 11729a coupled with 11732B (different pressings still combine the same takes) while another couples 11729B with 11732a. Jerome Don Pasquall remembers the cutting of several tests and likely three masters each of six different tunes (which is confirmed by Gennett ledger notes). Although Robert Shelby, bjo/gtr, and Bert W. Greene, dms/perc, may both still have been in the band at this time, it is not possible to trace/hear any special contributions by them on the above sides. The glockenspiel during the opening breaks of 11727 and the subsequent special grinding-sound-effect during the clarinet-solo-break could easily be handled by Hilaire (after all he was also teaching xylophone and further well versed within the percussion field). Actually the cymbals/woodblocks are not really audible until about two minutes into the recording, which leaves Hilaire plenty of space/time to handle the glockenspiel etc. "So This Is Venice", Edison Bell Winner 4056, Diplomat Novelty Orchestra, was erroneously assigned to Cook’s Dreamland Orch., by Norman Turner-Rowles in “Jazz Music”, Vol. 6/1, 1954. It is actually a Harry Reser unit. Silvertone labelled COOK’S DREAMLAND ORCH. (capital letters). “Moanful Man” resembles very much “My Daddy Rocks Me with One Steady Roll”, the latter title not recorded until 1925.

Pasquall’s memory is not failing if one takes a look at the Gennett papers. Bill Grauer, Record Changer, December 1953: “ . . . the ledgers and records of the Gennett label, which have always been carefully preserved by the Gennett family, have never before been made available to the jazz public. The Record Changer now is able to offer selected pages excerpted . . . “. It is interesting to note that titles slightly misspelled in discographies are correctly spelled in the Gennett paper (even though other mistakes appear). As seen, the Gennett executive (presumably) noted his favourite tracks by writing the word “Best” next to the following matrix numbers, 11728, 11729B, 11730, 11731, 11732A - no preference written as for the first side recorded. This would verify that the coupling of 11729B/11732a probably was the first release while the coupling 11729a/11732B came later (in the dead shellack the take number ‘a’ is used instead of the capital ‘A’ used in the Gennett papers).

- - - -

Johnny St. Cyr recollects:

I left New Orleans to go to Chicago in September, 1923. I bought a round trip ticket as I did not know if I would stay. I stayed six years. I was to play with the King Oliver Band for two weeks at Lincoln Gardens to catch their style. I received $75.00 a week which was also to cover my fees for recording. I knew everyone in the band except Lillian Hardin. She had heard about me from all the other fellows in the band and we became good friends right away. Lillian was a very friendly, wonderful person. Charlie Jackson was playing bass-sax with the band at that time. He played all the bass instruments, viol and tuba as well. Bill Johnson had already left, but where he went I don’t know, as I never saw him in Chicago. We had played together with the Olympia Band in New Orleans. I had no trouble playing with this Oliver band as they were playing exactly the same style as in New Orleans. The Lincoln Gardens was a black and tan club, no segregation, it was a great musicians’ hangout and musicians from all over came in there to hear the band. The recordings made by this band give a good idea as to the way it sounded. That is to say, they played the numbers on the recordings exactly the way they played them on the job. There were however a lot more numbers in their repertoire than ever got recorded. The recording companies liked to record unpublished numbers so they would not have to pay royalties if they got a hit record. They just bought the numbers outright for $25.00. I roomed and boarded with Joe Oliver and his family when I first arrived in Chicago, this was part of our agreement. When my two weeks with the band was about up and I was in need of a job, Darnell Howard came in one night. He heard me working with the band and asked Joe, ‘Where can I find a banjo player like that?’ Joe told him I would be free after the week was up. Darnell had the band at the Arcadia Ballroom at Sunnyside and Broadway on the North side, so I went with him for $50.00 a week. We played stock arrangements, nothing special in the way of music, the same type of stock arrangements we used on the riverboats. After two months Darnell lost the job and the band broke up. Joe Oliver had asked me to find other accommodations, as he just had a small apartment and we were a little crowded. Louis Armstrong and Lillian were planning on getting married and had rented a house, but had not moved in yet. They told me to move in there and make myself at home. I stayed there for a while with them after they were married. Charlie Cook had used me on a recording date he had at Columbia (actually Gennett - but anyway St. Cyr’s assertion confirms that he was on Cook’s very first recordings) while I was with Darnell Howard’s band. He liked my work and told me to look him up if I ever needed a job. When Darnell’s band broke up, I let Cook know I was available. He hired me and I went right to work with Cook’s Dreamland Orchestra at Harmon’s Dreamland Ballroom located at Paulina and Van Buren Streets. This was the first band I ever played with that used their own special arrangements on every number that we played. Also, they were the first arrangements in a jazz style. We had many specials, strictly in the jazz style, but all arranged, written out. Doc Cook did all his own arrangements. He played piano and organ. He was just an average piano player, but he was at his best at the organ. The use of ad lib, hot solos, etc., had not come into too much use at this time in the larger bands. Two of my old friends from New Orleans were in this band, Freddie Keppard and Jimmie Noone. In the afternoon I used to go over to the Musician’s Union Hall at 49th and State. This was a three storey building owned by the Local. The second floor was a recreation hall for the members of the local. There were card tables, and pool tables, with sandwiches and soft drinks on sale, and of course, crap games and a bootlegger who could always get you a pint. This was a great hang-out for a lot of musicians, including Freddie Keppard. Freddie was drinking a lot by this time, although, he never seemed to let it interfere with his work. We spent a lot of time together at the Union Hall and were the best of friends. Freddie was playing very well, with Doc Cook, as well as all the gigs we all used to get around town. In spite of some of the stories about him, he was a pretty good reader, he played all those arrangements Doc Cook wrote, as well as playing with other bands on gigs. These bands would have their own library of music. He had been reading violin music many years before in New Orleans, before he took up the cornet. Freddie had been, in New Orleans, the first of the get off men on cornet, a real pace setter and pioneer. In Chicago, he was more satisfied to let music just be his work. His inspiration to be coming up with something new seemed to be gone. To compare him to Louis Armstrong I would say: they both started out about even as to ability and inspiration, but music was Louis’ whole life and with Freddie Keppard, it got to be just the way he earned his living, just a job. He also had that independent Creole temperament and was not always the easiest guy in the world to get to cooperate. He had his own ideas about a lot of things, but he was a great jazz musician and a good friend of mine. A lot of the New Orleans musicians didn’t hang around the Union Hall at all; for example, Joe Oliver and Johnny Dodds. Johnny was a quiet, serious man, all business. Although we recorded together a lot, this was about the only time we would meet. We never played together on a job except the first few weeks when I came to Chicago. Johnny had come to Chicago several years before I did. Fie had bought a small apartment house where he lived with his family. I would only see him once in a while at the Union Hall when he came in to pay his dues or on a record date. We were always friendly, but not what could be called close friends. I had been good friends with Joe Oliver in New Orleans and of course kept this friendship up in Chicago. Joe didn’t come around the Union Hall much either, although I used to visit him at his home. Joe didn’t like to go out much. He was such a big eater, he always said it embarrassed him to go out to eat, so I would stop by his home now and then for a visit or a meal. He never asked me to join him as he knew I was set with Doc Cook. He was a good-humoured man, liked to joke with his friends, talk with them. He was very business-like, a good band leader and organizer. Jimmie Noone didn’t come around the Union Hall much either. He was quite a ladies man, and usually spent his spare time visiting one or the other of his girl friends. Of the other musicians around in those days George Fields, Ray (Roy) Palmer, Honore Dutrey, Kid Ory, Jelly Roll Morton, Richard M. Jones never spent much time around the Union Hall. Jelly Roll and Richard M. Jones spent most of their time around Melrose Bros Music Store. That is where I first met Jelly Roll. I had known him in New Orleans very slightly. Richard M. Jones kept himself busy with the Okeh Record Company. He was their contact man for their race records. He was a fine fellow, very jolly and a good organizer with a good head. He knew music very well, but he was just an ordinary piano soloist, nothing special. I had made arrangements in 1917 to go to Chicago to join Charlie Elgar, but it was a very cold winter and the spot we were to play

in never opened for that reason. Charlie Elgar was a good legitimate musician and his musicians were more on the sweet side. He was active as a leader while I was in Chicago. Joe Poston was one of my special friends in the Doc Cook Band. He was from Alexandria, Louisiana. He played saxophone and oboe. His music was more on the sweet side. He and Doc Cook and myself were called the Three Musketeers as we always rode to work together. Then, sometimes after work, we would get a pint of prescription whiskey from a druggist we knew and go over to Doc Cook’s. Joe and I would sit around and have a few while Doc worked on his arrangements. Doc always worked at a high desk and stood up to write. He could write out music as fast as I could write a letter. Stump Evans was one of the few musicians not from New Orleans who seemed to fit in with our bunch; that is, his style of playing. He was from St. Louis and had picked up our style off the riverboat bands before he came to Chicago. He was the first sax player I ever heard to play slap tongue. We all liked his work and he got in on a lot of record dates with us for this reason. He played regularly with Erskine Tate at the Vendome Theatre and hung around a pool room at 35th and State. He was very short in height, which gave him his nickname Stump and not Stomp as it is sometimes misspelled. The Musicians’ Union, Local 208, owned their own three storey building. The first floor was offices of the Union, the second floor was devoted to a recreation hall for the Union members. The third floor was a hall rented out to lodges and groups of that type, George Smith was the president of the local at that time. When a band leader would get a gig he could just come down to the local and get all the men he needed. There were a lot of the theatre pit orchestras then, Iike Dave Peyton’s, Erskine Tate’s and Charlie Elgar’s. When they would get a dance job they would pick up some dance men at the Local. Willie and Lottie Hightower had a gigging band. That is to say they had no regular location job. Thee would fill out the band with men from the local. I played many gigs with all of these groups. These leaders all had their own music libraries, and were mostly reading bands, but playing in the hot swing style. Lottie Hightower was the secretary of the local and worked in the office. I had known Willie Hightower in New Orleans. Lottie was from Louisiana, but not from New Orleans. She played good band piano, and Willie played in the New Orleans style, good swinging lead. I knew them both well and played many gigs with them. They used me whenever I had the time off and could make a job with them. There were so many great musicians around Chicago at that time I would never be able to name them all. Also singers, they all worked in Chicago at one time or another when I was there. Doc Cook’s Band worked in the winter at Harmon’s Dreamland Ballroom. In the summers we worked, during the hot weather, in the amusement parks, Riverside, and White City. These parks had all types of amusements such as roller coasters and things of this type. These parks also had large ballrooms for dancing.

Latest news: During April 2013, Lars Falk from Malmö, Sweden, visited the Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University, in New Orleans. There he had access to some less known interviews by William Russell (August 27, 1958) with Johnny St. Cyr - in which St. Cyr, definitively and without hesitations, confirms that he is the banjoist on Doc Cook’s Gennett sides. References: Quite naturally, it seems that a few of the later informants (especially when not adding any new details) have in some cases been relying on the earlier researchers’ writings on the subject - which may in fact carry on some of the mistakes previously made). Hot Notes / Walter C. Allen, 1947 Hendersonia / Walter C. Allen, 1973 Freddie Keppard, Complete 1923-26, Retrieval 79017 / Mark Berresford, 1999 Chicago Defender, 1925 Who’s Who of Jazz / John Chilton, 1985 The World of Earl Hines / Stanley Dance, 1977 Hot Discography / Charles Delaunay, 1938 Jazz Journal / Jerome Don Pasquall interview / Frank Driggs & Thornton Hagert, 1964 Black Beauty, White Heat / Frank Driggs & Harris Lewine, 1982 Music Is My Mistress / Duke Ellington, 1973 Lars Falk, Malmoe, Sweden Swing Out / Billy Butler interview / Gene Fernett, 1970 Harlem Renaissance Lives / Henry Louis Gates Jr., & Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, 2009 (Charles Cooke entry written by Elliott Hurwitt) DoctorJazzWeb / Brian Goggin, May 2007 Record Changer July-August 1951 & December 1953 / William “Bill” Grauer Jnr. Jazzens Väg / Olle Helander, 1947 Pictorial History of Jazz / Orrin Keepnews & Bill Grauer, 1955 Big Band Jazz / Albert McCarthy, 1974 (sometimes McCarthy’s information is no doubt obtained from other accounts, so that mistakes are repeated) Yearbook of Popular Music / Paul Eduard Miller, 1943 Esquire’s Jazz Book / Paul Eduard Miller, 1944 Esquire’s Jazz Book / Paul Eduard Miller & George Hoefer, 1946 Chicago In The Twenties 1926-28, Arcadia 2011 / Dick Raichelson, 1977 (source for Raichelson seems to be Ramsey/Smith or Miller/Hoefer). “Chicago Documentary, Portrait of a Jazz Era” / Frederic Ramsey Junior, 1944 Jazzmen / Frederic Ramsey & Charles Edward Smith, 1939 Jazzways / George Rosenthal, Frank Zachary, Frederic Ramsey & Rudi Blesh, 1946

Jazz and Ragtime Records 1897-1942 / Brian Rust / Malcolm Shaw, 2002 (it would be highly interesting to learn the original source for the personnel entries re. Cook’s recorded output) Freddie Keppard, Herwin 101 / Peter A. Whelan, 19?? Storyville / Laurie Wright & The Storyville Team, 1965-1995 Storyville / Laurie Wright, 2002-03 King Oliver / Laurie Wright, 1987