BY RICHARD WEITZ Special Analytical Report JUNE 2011 · · 2017-04-01BY RICHARD WEITZ Special...

Transcript of BY RICHARD WEITZ Special Analytical Report JUNE 2011 · · 2017-04-01BY RICHARD WEITZ Special...

AN UPDATE ON THE RUSSIAN MILITARY

BY RICHARD WEITZ

Special Analytical Report

JUNE 2011

S E C O N D L I N E O F D E F E N S EDelivering Capabi l i t ies to the War Fighter

h t t p : / / w w w. s l d i n f o . c o m

AN UPDATE ON THE RUSSIAN MILITARY: A SECOND LINE OF DEFENSE SITE VISIT

by Richard Weitz

Enduring Goals! 2

Tour of Russia’s Missile Defense Facilities! 6

Russian Views on the Future of European Missile Defense! 10

Russian Arms Sellers Exude Optimism! 14

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

1

Enduring GoalsI have had the opportunity to participate in the first Defense and Security section meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club in Moscow from May 25-27.

The discussions focused on the modernization of Russia’s Armed Forces and cooperation in international security. The meeting was co-organized by Russian government RIA Novosti news agency, the independ-ent Council on Foreign and Defense Policy think tank, and the Center for Analysis of Strategies and Tech-nology (CAST) research institute.

According to its website, “the Valdai Dis-cussion Club provides a global forum for the world’s leading and best-informed experts on Russia to engage in a sustained dialogue about the country’s political, economic, social and cultural develop-ment.”

The participants included about a dozen foreign military experts from Belarus, France, Germany, Norway, Turkey, and the United States. Almost a dozen other participants came from various Russian organizations.

Credit: http://worldofdefense.blogspot.com/2011/06/state-of-russian-army-by-dr-richard.html

On May 25, the first program day, we traveled an hour outside Moscow by bus to visit the 5th Guards Independent Motor Rifle Brigade. The acting commander led us on a tour of what was formerly known as the Division Tamanskaya. We first learned about the history of the unit through an hour-long tour of its museum. The unit was formed as the 127th Infantry Division in Kharkov on July 8, 1940. It achieved full combat readiness the following year, only two weeks after NAZI Germany launched its surprise attack on Stalin’s underprepared Red Army. The unit fought with distinction throughout the war. It also served in the North Caucasus in the late 1990s, helping to “restore constitutional order to Chechnya.” In line with the current Russian military reform program, the division was restructured as a brigade in the last few years.

After the museum tour, we then visited a barracks for the enlisted personnel. We also toured the gym and ate a decent meal in the canteen. Everything looked very nice though the question naturally arises how S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

2

representative the facilities on display are of conditions in other parts of the Russian military. The brigade is special in at least one respect: the Russian Army uses the unit to test new tactics, techniques, and pro-cedures.

The most interesting part of the tour was the live fire drill. The acting commander explained to us that new recruits undergo three stages of combat training. First, they study theoretical topics in the form of academic lectures. Then they go to the practicing ground near the dormitory to undertake small-scale

simulated training. The final stage involves live-fire training in an open field.

We had the opportunity to watch them engage in the latter two stages of live-fire drills. It was quite a show, with loud explosions and fireworks simulating various combat conditions at the practicing ground. We saw units practice artillery attacks, small unit assaults, medical operations, and even nuclear, biological, and chemical decontamination of a tank with soldiers in personnel protection suits. All the soldiers were male conscripts except for a few male officers and technical specialists.

T-90 Tank http://armour.ws/russian-t-90-tank/

We then saw an exhibition of some of the most modern equipment of the Russian Army. For example, we were given a detailed briefing on the T-90 main battle tank. The commander said that the T-90 had no equivalent in the world. Unlike the M-1 Abrams, which uses a gas turbine engine, the T-90 uses a diesel engine, which is easier to upkeep and more suitable for Russian winters. The T-90 is also much smaller than the Abrams. We also saw the BTR-80 [GAZ 5903] Armored Personnel Carrier, the 2S6 Tunguska inte-grated air defense system (armed with cannons as well as surface to air missiles), and other combat sys-tems as well as the Ural system of trucks. We also were able to handle a number of small arms and light weapons as well as uniforms and other military equipment.

We then went back to downtown Moscow to visit the RIA Novosti press club for a discussion on recent Russian military reforms, introduced by Sergey Karaganov, chairman of the “Valdai” Club. I had the op-portunity to work with Sergey in the mid-1990s, when I was a post-doc at the Center for Science and In-ternational Affairs (CSIA) at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. The CSIA, then led by Graham Allison, collaborated with Karaganov’s Institute on several security projects, some-times in collaboration with a European institution.

At RIA Novosti, Ruslan Pukhov, the head of CAST, reviewed some of the key Russian military reforms. According to his briefing, the Russian army before the reform process began a few years suffered from several major flaws.S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

3

These defects included excessively large command and administrative structures given the number of 100,000 combat-ready troops; a disproportionate number of officers and warrant officers, who comprised approximately half of Russia’s military personnel; less than 13 percent of units being fully manned and combat ready; and hardly any procurement of modern weapons. Several other contextual factors drove the reform process, including a radical transformation in Russia’s military-political situation due to the declining probability of large-scale wars and the growing prospects of Russian military involvement in regional conflicts, insurgencies, and counterterrorism operations.

In addition, modern warfare had evolved with network-centric operations and tactics replacing those for deep attacks, resulting in a rising relative importance of the Air Force and cyber systems and decreasing need for traditional conventional ground forces.

One of the main elements of the reform included transitioning from a mass-mobilization army to a smaller number of better trained and effective permanent combat readiness forces, with the under-manned (“cadre”) units consolidated into a smaller number of fully manned and combat ready brigades.

Most of the personnel cuts were directed against the officer corps, which was to be reduced by more than half, from 355,000 to 150,000, with all warrant officers eliminated and a new noncommissioned officer corps replaced. The main administrative unit was to change from divisions and regiments to smaller and more flexible brigades. The number of Army units was to decrease from 1,890 to 172 units, the number of Air Force units from 340 to 180, and the number of Navy units from 240 to 123.

The reform also envisaged an end to efforts to replace all conscripts with professional contract soldiers because conscript soldiers are cheaper, provided a large well-trained reserve component after they leave active service, and represent a practice more in harmony with Russian history and tradition.

The problem is that the length of the conscription, 12 months, does not provide sufficient time to train soldiers in modern combat operations. The reforms sought to improve the conditions of conscription by allowing them to serve close to their homes in some cases, by establishing a five-day work week (with two days off), and some less pleasant non-combat tasks (such as cleaning and cooking) outsourced to con-tractors.

Thus far, the reforms have achieved mixed results. Critics complain they have been proceeding too rap-idly, with insufficient development and planning. The Russian government’s ability to provide adequate financial and other resources to the reform process has also been questioned. The transformation of the units has been criticized for having insufficient command, reconnaissance, logistics, and rear services components. The ability of civilians to replace so many military personnel is also uncertain. The Ministry of Defense has also not yet made clear how it plans to train and maintain the reserve component.

Konstantin Makienko of CAST delivered a report on “State Armament Program 2011-2020.” The reforms have sought to increase the large-scale acquisition and procurement of modern military equipment. Most S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

4

of this equipment is Russian-made, but some foreign systems are being imported from foreign countries to help keep the Russian defense industries, not wishing to lose their domestic market, competitive. In contrast, the large size of the State Armament Program (SAP) 2011-2020 means that Russian defense in-dustries will now give priority to providing weapons to the Russian military rather than manufacturing systems for exports.

The SAP aims to increase the proportion of modern weaponry in service with the Russian military to 30 per cent by 2015, and to 70 percent (up to 100 per cent for some types of weapons) by 2020. The Ministry of Defense (MOD) will spend 19.5 trillion roubles for its share of the program, with other security services paying smaller sums for their orders. The Ministry’s priority procurement areas will be strategic nuclear

forces, high-precision conventional weapons, and com-mand, control, computers, and Command, Control, Com-munications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems. Military research and development spending will decrease considerably from current levels to 10 per cent of overall spending, while 80 per cent of the MOD SAP will now go to buying new weapons, with the remaining 10 per cent paying for the repair and upgrade of existing equipment.

T-50 Fighter http://www.blogetron.com/2010/06/russian-fighters-vs-american-fighters.html

Under the SAP 2011-2020, the Air Force will procure up to 70 fifth-generation T-50 Fighters, 96 multirole Su-35S fighters, as many as 100 Su-34 frontline bombers, up to 20 An-124 heavy transports, 50-90 Il-476 transports, and as many as 120 Yak-130 advanced jet trainers. The Air Force will also order 900-1000 heli-copters, which includes 250 Mi-28N attack helicopters, as many as 120 Ka-52A and Ka-52K attack helicop-ters, 22 Mi-35M attack helicopters, and as many as 200 air defense systems.

Meanwhile, the Navy will procure 6-8 Project 955A and 955U strategic ballistic missile submarines, 150 R-30 Bulava submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), about 40 R-29RMU-2 Sineva SLBMs, 6 Project 885/885M nuclear-powered submarines, 2 Project 677 diesel-electric submarines, 3 Project 06363 diesel-electric submarines, and 2 foreign-made landing helicopter docks (perhaps France’s Mistral-class ships), 8 Project 22350 frigates, 6 Project 11356M frigates, 1 Project 11661K frigate, and 35 corvettes, including at least 4 of the advanced Project 20381/20385. The Navy will also receive 26 MiG-29K carrier-based fighter planes. The SAP will also finance the repair and upgrade of the Project 11435 heavy aircraft carrying cruiser and the Project 11442 heavy nuclear-powered guided missile cruiser.

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

5

The main threat to the fulfillment of the SAP is Russia’s uncertain macroeconomic situation. Another problem could be the persistent weaknesses in some elements of Russia’s military-industrial complex, which has yet to fully recover from the break-up of the integrated Soviet complex in which defense orders received priority resources. The problems with the development program for the Bulava SLBM are par-ticularly indicative of the problem Russian defense firms have in integrating complex weapons systems when a number of small sub-contractors are responsible for developing and manufacturing key compo-nents.

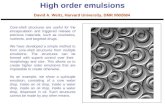

Tour of Russia’s Missile Defense FacilitiesThe second day of the Russia site visit began with a tour of the DON-2N multi-functional radar station at Sofrino, about 90 minutes outside Moscow. The facility is one of Russia’s most im-portant aerospace facilities. It is a ma-jor component of Moscow’s missile defense system, which the Soviet Union constructed to protect the capi-tal.

http://visualrian.com/images/item/905254

The Soviet government preserved the Moscow system as its sole missile defense site permitted by the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty. The DON-2N radar station can detect and track ballistic missiles, analyze targets, and aim interceptor missiles at them.

Furthermore, the radar station contributes to Russia’s unified missile warning and space surveillance sys-tem. It also detects and tracks objects in outer space and sends this data to Russia’s Central Space Surveil-lance Center.

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

6

Although the base commander greeted our group and saw us off, we were given a lengthy tour by Major General Vladimir Derkach, First Deputy Commander of the Russian Space Forces http://www.inf.sch1451.edusite.ru/p12aa1.html

As part of Russia’s military reforms, the Russian Space Forces (Космические войска России) are being merged with the Air Defense Forces into a single command. Earlier, they had been part of the Strategic Missile Forces, but this merger proved detrimental since the offensive forces received priority funding and other treatment. The Space Forces operate the GLONASS global positioning system as well as control the Baikonur, Plesetsk, and Svobodny Cosmodromes.

After we entered the complex and left all our electronic devices behind, the tour of the DON-2N multi-functional radar station began with tea, coffee, and some informal chatting with Derkach. Then we visited the base’s one-room interior museum. General Derkach explained that all Space Force units have such museums to assimilate new officers as well as remind all those at the station of their traditions and val-ues.

Construction of the radar started in 1978. It became operational in 1996. The station’s exterior resembles a four-sided truncated regular pyramid. It is 30 meters high. The sides of its lower platforms measure 140 meters, while its upper platforms are 100 meters in length. The sides house phased array antennas for tracking targets and guiding interceptors.

Many of its systems operate automatically and are highly jam-resistant. It has independent supplies of power, water, food, and other inputs needed to function regardless of its external environment. Its key systems are duplicated to provide redundancies in case of attack, failure in one system, or the need to replace equipment and parts without shutting down.

The radar is capable of monitoring the airspace throughout the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and other areas such as Iran. It works with Russia’s early warning satellites and the new radars Russia is con-structing on its periphery to provide Russian commanders with aerospace situational awareness.

Although this was not discussed in the museum display, for some time in the 1990s, following the disin-tegration of the Soviet Union (many of whose early warning radars were situated in the other Soviet re-publics) and a sharp decrease in military spending (which led to failure to build and launch a sufficient number of new satellites to replace the Soviet-era ones when they went out of service), Russian leaders lost this capacity.

Both Russians and foreigners were concerned about this situation of uncertain early warning, since it could lead Russians to misperceive a nonexistent foreign missile attack on the Russian Federation.

After the museum, we then saw the display where the aerospace information is projected on a big screen. The command center used the kinds of telephones common in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s,

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

7

while the display also looked like it did not use the latest big screen technology. Nonetheless, Derkach said the system was very accurate, and could easily detect objects the size of a soccer ball and focus on select objects with even greater accuracy.

The General explained that the radar’s command and control system operates automatically once it re-ceives authorization to do so from the General Staff. We then entered a section of the station that allowed direct access to its exterior walls, where we saw one of the elements of the phased array being removed for repair.

Unlike the NATO hit-to-kill systems, Russian missile interceptors use nuclear-armed warheads. General Derkach said that Russia planned to transition to the use of only conventional warheads as the detection, targeting, and interception capabilities of the Russian systems improved and as the requirements for Rus-sian missile defense changed.

Due to its explosive power and other ef-fects, a nuclear warhead can more easily destroy incoming warheads as well as their decoys, which present problems for “hit-to-kill” systems that must distinguish between genuine warheads and decoys. NATO countries, which have long aban-doned the use of nuclear warheads for missile or air defense, are eager to pro-mote this conversion since they contribute to the imbalance in the number of so-called non-strategic (also known as tacti-cal) nuclear warheads and make it diffi-cult to negotiate arms control agreements between Russia and the West.

DON-2N Phase Array Radar Station

http://russiamil.wordpress.com/2011/06/02/valdai-club-3-touring-the-don-2n-radar-facility/

Many U.S. Senators have indicated that they would not support another Russian-U.S. strategic arms con-trol agreement unless it placed restrictions on Russia’s large stockpile of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

General Derkach stressed that the DON-2 radar station, and other Russian facilities, could make an im-portant contribution to any joint NATO-Russian missile defense system. He claimed it can detect all mis-sile launches from Iran despite their initial launch site and subsequent trajectory.S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

8

Although the General stressed that Russia’s participation in any multinational missile defense system was a decision for the country’s political leaders, Derkach said it could theoretically save money, augment protection against missile threats, and promote international cooperation.

General Derkach explained that the DON-2 radar was also used to track outer space debris. Space is be-coming more congested with orbital debris and other objects. Estimates are that there are more than 100,000 man-made objects in space, of which current technologies can track some 20,000 items. Even very small and undetectable debris can still threaten the more than one thousand active satellites and manned space ships.

Since my sister works for NASA, I asked the General about the new U.S. National Security Space Strategy, which calls for the United States to cooperate with foreign countries to address the growing quantity of space debris. A priority is sharing more data about debris and orbital locations with the private sector, foreign governments, and intergovernmental organizations.

The collaboration aims to improve the international community’s ability to rapidly detect and respond to adverse developments in space. The new approach recognizes that no one nation has the resources or ge-ography necessary to track every space object. The goal is to avoid collisions by notifying satellite opera-tors much earlier and with much greater accuracy of potentially hazardous conjunctions between orbiting objects.

General Derkach said that cooperation could easily proceed in two ways.

First, Russia, the United States, and other countries should make sure to avoid adding more debris by, for example, testing anti-satellite weapons (which the Chinese did in 2007, breaking a two-decades morato-rium on such tests) or conducting more interceptions in outer space. He said the DON-2 radar station could help target and intercept objects in both the air and in outer space, but that the Russians had never used it for the latter purpose.

Second, Russia, the United States, and other countries could exchange information about the volume and location of space debris to improve situational awareness and minimize accidental collusions. Derkach agreed that orbital debris was becoming a major problem for Russia and other space powers since it dam-aged satellites and threatened space ships

We were all impressed by General Derkach’s professional manner and willingness to answer all our ques-tions in a frank and often detailed way. At one point, he noted that all officers of the Russian Space Forces are educated at the Mozhayskogo Military Engineering-Space Krasnoznamennyy in Saint Petersburg. Even in Soviet times, the officers serving with the strategic offensive and strategic offensive forces were well-respected for their high levels of education and other attributes.

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

9

Meeting the General and his team made us feel that this superior performance continues despite the con-straints placed on Russia’s defense budget and other military capabilities.

Russian Views on the Future of European Missile DefenseMany of our discussions in Russia last week focused on missile defense issues in preparation for the June 9 meeting of the NATO-Russian Council (NRC) at the level of defense ministers.

NATO-Russian differences over ballistic missile defense (BMD) have persisted even after both parties, at the November 2010 NATO and NRC summits in Lisbon, agreed in principle to cooperate on missile de-fense. At the summit, NATO governments dutifully pledged “to explore opportunities for missile defence co-operation with Russia in a spirit of reciprocity, maximum transparency and mutual confidence.”

NATO and Russia have committed to resume joint exercises of their theater BMD systems, which were suspended following the August 2008 Georgia War. And their experts are currently engaged in a joint analysis of the modalities of NATO-Russia collaboration for common territorial missile defense. Their analysis will address such questions as a common architecture could look like, how costs and technolo-gies might be shared, how to apply the knowledge gained from the joint exercises to a more permanent joint NATO-Russia BMD system, and how to cooperate in defense of European territory rather than NATO and Russian military forces on deployment. The experts will report their initial findings to the de-fense ministers on June 9, 2011.

On May 26, RIA Novosti hosted an entire panel devoted to assessing proposals to build a joint NATO-Russia European ballistic missile defense (BMD) architecture. The most optimistic perspective came from Oksana Antonenko of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), who delivered a report on “NATO-Russia Missile Defense Cooperation.” Antonenko first reviewed the history of NATO-Russia BMD Cooperation. She believed some progress was achieved in the 1990s and early 2000s before the Rus-sians became irritated at Bush administration plans to deploy BMD systems in Poland and the Czech Re-public. She believed the Obama administration’s Phased Adaptive Approach toward European missile defense along with Russia’s agreement to consider deep NATO-Russia BMD collaboration have estab-lished the potential for missile defense to become the “game changer” driving NATO-Russian relations to a new level of cooperation.

Antonenko saw several benefits from NATO-Russia BMD cooperation. It could strengthen transparency into US and NATO BMD motives and plans; enhance regional stability more generally; dissuade states from proliferating, deploying, and using ballistic missiles; leverage the technological strengths of the United States, other NATO members, and Russia through integration; and build a strategic NATO-Russia partnership against the common threat from WMD and their delivery systems. Russia in particular would find it better to cooperate in order to gain some influence in the system’s development rather than face

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

10

exclusion from the U.S. and NATO system. Russia could also face genuine threats from rogue states and benefit from the export and import of BMD technologies between NATO and Russia.

Despite these obvious benefits, Antonenko acknowledged that BMD cooperate faces several critical obsta-cles. These include a mutual lack of trust; Russian concerns that U.S. BMD will threaten Russia’s nu-clear deterrent; the U.S. administration’s need to justify paying so much for a European BMD system by equipping it with the advanced capabilities needed to also defend the United States from foreign missile attack; Russian attitudes that treat Central and Eastern Europe as an area near Russia’s borders where Russians do not want U.S. or NATO military infrastructure deployed; and the reciprocal negative attitudes of some central and eastern European countries towards Russia; and the failure of various confidence-building measures proposed by the George W. Bush administration.

http://nato-russia.org/?tag=bmd

Yet, Antonenko still believed that it was possible to develop NATO missile defenses in cooperation with Russia. In her assessment, the parties need to focus on countering threats from short- and medium-range missiles (up to 4,500 km). Russia and the United States should open their long-delayed joint data ex-change centers in Russia, Belgium, and the United States as well as resume joint BMD exercises. Con-versely, they should not compromise on sovereignty issues. NATO and Russia should each defend their own territories, but countries should be allowed to enter into special agreements to receive double protec-tion, an arrangement that might be suitable for North East Europe.

Antonenko referred to a “cooperation paradox” in this area. One element was that, “We can’t know if we are willing to cooperate until we know what cooperation looks like; we won’t know what cooperation looks like until we begin to cooperate.” Another element of the paradox was that, “Technologically and doctrinally there are no problems for establishing compatibility between US/NATO and Russian Missile Defence Systems, all obstacles are political and bureaucratic.”

Her solution was that continuous cooperation builds transparency and trust.

A much less optimistic assessment was provided by the Russian team at the Center for Analysis of Strate-gies and Technology (CAST) in their briefing on “Missile Defense: Implications for Global and Russian Security.” They began by claiming that the United States had a missile defense philosophy that sees BMD

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

11

as a means to restore the invulnerability from foreign attack that the United States enjoyed before the So-viet Union acquired nuclear missiles and established a state of mutual assured destruction.

In their assessment, U.S. missile defense systems would not have the capability to defend against Russia’s nuclear forces for the next 10-15 years. They believe that the current American missile defense system is genuinely directed against missile threats posed by “pariah” countries. The purpose of the BMD systems in Alaska and California is to protect the United States against North Korean missiles, while U.S. BMD systems in Europe aim to protect Europe against Iranian missiles. They maintain that the Standard Missile-3 in Poland and Romania are incapable of catching up with missiles launched from the Russian missile fields at Tatishchevo or Kozelsk.

Nonetheless, the CAST analysts claim that Washington’s strategic aim is to devalue Russia’s and China’s nuclear deterrence forces. The current “limited” missile defense system is thus a necessary stage before constructing a fully capable system aimed against Russia. The CAST team considers U.S. declarations that U.S. missile defense systems aim to defend only against “pariah” states as an attempt to disguise the in-termediary and experimental nature of the U.S. BMD program.

When assessing the Russian response, the CAST team begins by stating that preserving the efficacy of Russian nuclear deterrence is of paramount importance for Russian security. As noted above, they assess that the U.S. BMD systems will threaten this foundation of Russia’s security in the longer term. They do not believe that the U.S. missile defense program can be stopped by political or diplomatic means. They consider proposals to establish a joint missile defense system aimed against pariah states as unrealistic and harmful to Russian interests since it indirectly legitimizes the development of the U.S. system. The CAST team believes that the only realistic and credible response to U.S. BMD plans is for Russia to im-prove the size and capability of its strategic nuclear forces.

Alexander Stukalin, Deputy Editor-in-Chief of the Kommersant daily newspaper a member of the Rus-sian Defense Ministry’s Public Council, likewise highlighted Russian-U.S. differences regarding missile defense. He noted that the conditions that allowed both Moscow and Washington to abstain from devel-oping BMD in their 1972 ABM Treaty have changed so much that by 2001 the new George W. Bush ad-ministration felt compelled to withdraw from the treaty. Not only was there new technology, but there was a new global security order following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. Both Russia and the United States now faced new threats and new security challenges. In principle, these new conditions could have led to the creation of a new joint missile defense, but in practice several recur-ring obstacles have prevented realization of this goal, despite years of discussions and negotiations.

According to Stukalin, the fundamental problem is that Americans and Russians have a “perpendicular” view of missile defense. Americans see a multipolar world in which dozens of states are acquiring medium-range ballistic missile capabilities, which could threaten important America’s European allies. In contrast, Russians perceive a bipolar world in which NATO remains the main security threat. In Stuka-S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

12

lin’s view, “Unfortunately, the United States firmly believes in the existence of new types of missile threat, and is set to neutralize them…. Likewise, Russia is convinced that the [NATO] ballistic missile shield is

targeted at its strategic potential and will soon become a very real threat.”

Stukalin did however highlight a new phe-nomenon. In the last few months, the Russian General Staff has adopted a much higher pro-file in the Russian government’s public dis-cussions on the issue. Until recently, it was the Russian President, Prime Minister, and For-eign Ministry that dominated the dialogue. But now senior Russian generals are out front in stressing the dangers from the U.S. missile defense programs.

Chief of General Staff Nikolai Makarov http://www.acus.org/content/russias-chief-general-staff-gen-nikolai-makarov-baltic-fleets-training-center-kalingrad-sept

This campaign reached its climax a few days before our arrival in Russia, when the General Staff hosted an open conference on missile defense at its Military Academy. According to media reports, the leaders of the Russian General Staff at the conference claimed that U.S. missile defenses in Europe could threaten Russia’s strategic nuclear forces as early as 2015. A briefing by General Staff deputy chief Andrei Tretyak, head of Main Operations Directorate of the General Staff, alleged that the U.S. interceptors stationed in Eastern Europe would by then be able to shoot down intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) launched from western Russia. The speakers also denied that Iran or North Korea would soon be able to launch ballistic missiles capable of hitting targets in NATO countries.

The Obama administration new Phased Adaptive Approach (PPA) toward European BMD in September 2009. The PPA would increase U.S. BMD capabilities in phases, roughly in proportion to the anticipated growth in the Iranian military threat. It would first defend against limited ballistic missile threats, but hedge against emergence of more substantial threats in future. Phase I began in March 2011 with de-ployment of a U.S. cruiser armed with SM-3 Block IA missile interceptors in the Mediterranean. Under Phase II, the United States will deploy ground-based versions of SM-3 in Romania or other NATO coun-tries near Iran in 2015. Phase III would station more advanced interceptor missiles in Central European countries such as Poland as early as 2018 should Iran’s missile capabilities continue to improve. Under

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

13

Phase IV, planned for 2020, US would deploy advanced SM-3 IIB, designed to intercept ICBMs heading toward United States, in Eastern Europe.

According to U.S. experts, only these Phase IV interceptors would have the theoretical capacity to inter-cept some ICBMs launched from Russia, a view shared by some Russian experts, including Yuri Solo-monov , Russia’s chief ballistic missile designer. And the Obama administration has stressed that it would take measures to reassure Russia that the new systems would not present a threat.

Nonetheless, Chief of General Staff Nikolai Makarov told the General Staff conference that he does not trust U.S. claims. He added that a U.S. decision to proceed with the deployments would provoke a new arms race. “If NATO’s plans to build a missile defense system … without consulting Russia, and even more so without her participation, we can not tolerate the threat to the basic element of our national secu-rity – our strategic deterrence forces.”

Russian Arms Sellers Exude Optimism

Some of our most remarkable discussions during the May 25-27 session of the Valdai International Dis-cussion Club in Moscow were with senior military and civilian officials in Russia’s defense community. These occurred under “Chatham House Rules,” which allows us to use the information without attribut-ing it directly to the speaker.

One such dialogue might particularly interest Second Line of Defense readers. On Tuesday, May 25, we had dinner with the head of one of Russia’s main defense corporations. He shared with us his insights on a number of issues, including Russian perspectives on future sales opportunities at home and abroad.

The fall in Russian arms sales to China in the past few years has led many Western defense analysts to believe that Russian arms dealers have essentially given up on the Chinese. Since Russia and China signed a military-technical cooperation agreement in December 1992, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has purchased more than 90 percent of its defense imports from Russian firms. During the 1990s, the value of these deliveries peaked at about one billion dollars annually. During the mid-2000s, this yearly figure has sometimes been twice as much. Between 1992 and 2006, the total value of Russian arms exports to China amounted to approximately $26 billion, or almost half of all the weapons sold abroad by Russian firms (more than $58 billion during that period).

In recent years, this situation has clearly changed. The growing sophistication of China’s defense industry now enables the PLA to buy Chinese-made systems rather than import Russian-manufactured ones. With the PRC government’s encouragement, Chinese defense firms have been exploiting the opportunities for licensed production in order to learn how to manufacture substitute products that, while perhaps not as good as the most advanced Russian weapons, would be still on par with those produced during the late Soviet period. PRC manufacturers are producing either more indigenous advanced weapons systems or more defense technologies, sub-systems, and other essential components that Chinese firms can insert S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

14

directly into foreign-made systems. The Chinese have also objected to the quality of some of the weapons they imported from Russia in addition to poor post-sale servicing of the imported systems. Furthermore, PRC representatives have also complained about how Russian production difficulties have resulted in lengthy delays in the fulfillment of Sino-Russian defense contracts. For their part, Russian and foreign experts suspect that the Chinese have reversed engineered some of the imported Russian military tech-nology.

Since 2005, the PRC has stopped purchasing Russian warships and warplanes and has ceased signing new multi-billion arms sale contracts. The director of Russia’s state-controlled arms export company, Ro-soboronexport, recently forecast that the value of Russian arms sold to China could decline to as low a level as 10 percent of the value of all Russian military exports in the coming years. Some experts believe that figure could fall even lower.

But the defense company head we had dinner with insisted that Russian firms still see opportunities for additional lucrative weapons sales to China. Although he recognized that Russia helped contribute to the improved quality of the PRC defense industry through its license transfer of Su-27 technologies and other means, he still saw future opportunities for profitable collaboration with the Chinese. According to him, such collaboration is possible since most representatives of the Chinese aerospace industry recognize that China’s defense sector is still lagging and therefore needs to rely on foreign partners.

When I asked about the PLA’s recently unveiled “5th-generation fighter,” this defense company leader responded that the Chinese have a long way to go before they will produce a genuine “5th-generation” plane equivalent to the Russian Tu-50. He explained that although some of the subsystems of China’s J-20 might be considered 5th-generation, the Chinese still need much more time to combine all these subsys-tems effectively and produce a genuine state-of-the-art 5th-generation craft.

Conversely, the defense company president also expressed some irritation at the Indians for forgetting that it was Russia, rather than India, who was the leading partner in their defense relationship. He added that, despite the decision of the Indian defense ministry to eliminate Russian (and U.S.) planes from their latest round of competition to sell India its next multi-role fighter, he still considered the country a good sales market as long as New Delhi realized that the process was a two-way street and that Russia had useful things to offer.

In terms of Russia’s own weapons purchases, the business executive expressed his approval for the Rus-sian government’s newly adopted State Armament Program (SAP) 2011-2020, which seeks to increase the large-scale acquisition and procurement of modern military equipment. The SAP envisages raising the proportion of modern weaponry in service with the Russian military from approximately 15 percent to-day to 30 percent by 2015, and to 70 percent (up to 100 percent for some types of weapons) by 2020. The Ministry of Defense (MOD) priority procurement areas will be strategic nuclear forces, high-precision

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

15

conventional weapons, and Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems.

Under the SAP, military research and development spending will decrease considerably from current lev-els of approximately 20 percent to 10 percent of overall spending, while 80 percent of the MOD SAP will

now go to purchas-ing new weapons, with the remaining 10 percent paying for repairs and up-grades of existing equipment. A sen-ior Russian general we met later said that the Russian military has adopted a long-term perspective toward its R&D efforts. The MOD is willing to wait many years before some funded pro-jects yield results.

The Su-30M is armed with precision anti-surface missiles and has a stand-off launch range of 120km.

http://www.airforce-technology.com/projects/su_30mk/su_30mk3.html

The defense company head we met with considered the SAP to be well-balanced between what the Rus-sian arms industry could efficiently produce (in terms of economies of scale) and what the Russian mili-tary can absorb (in terms of training adequate personnel and paying for the systems’ acquisition and up-keep). Russia’s defense industry could produce many more weapons systems, but the Russian Armed Forces would be incapable of incorporating all of them.

The SAP is also sufficiently large as to place the Russian defense companies in a good position to produce more after 2020, when Russian government defense procurement is expected to increase further. He also praised the MOD for adopting a more effective practice of servicing their systems in partnership with Russian firms rather than, as was done previously, trying to do everything in-house.

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

16

In contrast, he argued that Russian defense companies saw few good commercial opportunities in many former Soviet republics. Their defense budgets are so small that they can only afford to buy a few modern systems. Many of these purchases are discounted or subsidized by the Russian government as a means of bolstering the regional security ties.

The CEO, however, acknowledged that Russian firms do have opportunities to service and upgrade these countries’ existing Soviet-origin weapons. In the case of modern aircraft, such servicing and upgrades can be very lucrative. But some of these states, such as Kazakhstan, have pursued what he considered the mistaken policy of having firms from Belarus service their warplanes simply to save money despite the inferior quality of work.

But this official did see good global sales prospects for the Sukhoi T-50 (PKA FA), including those in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and even a few African countries. The Russian Air Force will also continue to purchase these planes through at least the current SAP (2020), and probably beyond, while the Indian Air Force will begin buying the planes around 2015.

He also believes that the Russian aircraft industry would further develop the Su-30/34/35 series, which he argued was completely different from the Su-27 sequence. He also stated that these 4th-generation planes would experience strong sales due to the Sukhoi’s commitment to produce 5th-generation craft. Buyers appreciate the company’s commitment to remain a leading developer of aerospace technology and could see how 5th-generation technology could be backfilled into their 4th-generation planes, as Suk-hoi was doing in the Russian Air Force.

Finally, he confirmed that Russian arms sellers did not consider European military aircraft manufacturers as major competitive threats. Although their planes were often of very high quality, they were typically very expensive due to limited production runs (resulting from the small size of the European domestic markets) and to high European labor and manufacturing costs. (The fact that EADS and Dassault bids have made it to the final round of the Indian multi-role fighter competition, while the Russian entry did not, presumably explains his critical remarks about the Indians not appreciating that their defense rela-tionship with Russia must be a two-way street.)

In our May 27 meeting in the Ministry of Defense, a high-ranking officer confirmed Russia’s willingness to import some foreign weapons systems if the domestic manufacturers lack the capacity to produce items efficiently. Nonetheless, Russian policymakers are aware that purchasing sophisticated foreign weapons is a difficult and expensive path, so it will only be done on a limited basis.

S e c o n d L i n e o f D e f e n s e! J u n e 2 0 11

17