Bloch-Principle of Hope summary

-

Upload

yekbarmasraf -

Category

Documents

-

view

251 -

download

0

Transcript of Bloch-Principle of Hope summary

-

7/23/2019 Bloch-Principle of Hope summary

1/4

8/11/2015 The Principle of Hope - W ikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Principle_of_Hope 1/4

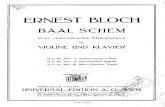

The Principle of Hope

The German edition

Author Ernst Bloch

Original titleDas PrinzipHoffnung

Translator Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, Paul

Knight

Country Germany

Language German

Subject Philosophy

Published 1954 (in German)

1986 (MIT Press, in English)

Media type Print

ISBN 0262522047

The Principle of HopeFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Principle of Hope(German:Das Prinzip

Hoffnung) is a book by Ernst Bloch that has become

fundamental to dialogue between Christians and

Marxists,[1]

published in three volumes in 1954, 1955,and 1959. Bloch explores utopianism, studying the

utopian impulses present in art, literature, religion and

other forms of cultural expression, and envisages a

future state of absolute perfection.

Contents

1 Background2 Synopsis3 Scholarly reception4 References

Background

Originally written between 1938 and 1947 in the

United States,[1]

an enlarged and revised version ofThe Principle of Hopewas published successively in

three volumes in 1954, 1955, and 1959. Bloch, who

had emigrated to the United States in 1938, returned

to Europe in 1949 and became a Professor of

Philosophy in East Germany. Despite having initially

supported the regime, Bloch came under attack for his

philosophical unorthodoxy and support for greater

cultural freedom in East Germany, and publication of

The Principle of Hopewas delayed for political

reasons.[2]

Synopsis

Bloch's theories have been summarized by the philosopher Leszek Koakowski in hisMain Currents of

arxism, and the description that follows is based on Koakowski's account: Bloch observes that

throughout history, and in all cultures, people have dreamed of a better life and constructed various

kinds of utopias. Utopian dreams are present in art forms such as poetry, drama, music and painting, and

in elementary form in children's dreams, fairy-tales, and popular legend. Utopian impulses can also be

found in architecture, medicine, sport, dancing and circuses, as well as in specifically utopian literatureand in the entire history of religion. Some utopias relate simply to immediate private ends, but the higher

kind of revolutionary utopia envisages the end of human suffering. For Bloch, the positive utopia is the

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utopiahttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Currents_of_Marxismhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Currents_of_Marxismhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/0262522047https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Standard_Book_Numberhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_Blochhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_Blochhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophyhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utopiahttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leszek_Ko%C5%82akowskihttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Germanyhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_languagehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Principle_of_Hope_(German_edition).jpg -

7/23/2019 Bloch-Principle of Hope summary

2/4

8/11/2015 The Principle of Hope - W ikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Principle_of_Hope 2/4

expectation of absolute perfection. Revolutionary utopias of past ages were seen by Bloch as reflections

of humanity's desire for perfection, post-Marxist utopias were all seen by him as reactionary. Bloch

insists the only two possible outcomes to history are absolute destruction and absolute perfection.[2]

European philosophy prior to Karl Marx was seen by Bloch as being largely content with interpreting

the existing world rather than planning for a better one. For unclear reasons, philosophy appears to have

been less marked by utopian impulses than other areas of culture. Bloch criticized Plato's theory that

knowledge is anamnesis, the remembering of something previously forgotten, for being centered on thepast, and believed that it had been repeated throughout the history of philosophy. Even philosophies that

projected a future state of perfection were defective in Bloch's view, since they always imagined this

state realized first in the abstract and therefore had no understanding of real change and no orientation

toward the future. Such philosophies, in which perfection or salvation was represented as a return to a

lost paradise instead of the creation of a new one, included those of Philo, Saint Augustine, and Georg

Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.[2]

Twentieth century philosophies, such as those Henri Bergson and Alfred North Whitehead, which

attempted to describe real change and maintain an openness to the future, did not receive Bloch's

approval. Bloch believed that Bergson's philosophy was not one of anticipation: in it the new is simplyan abstraction, a negation of repetition. Koakowski suggests that Bloch believed that not only

philosophy but all human knowledge prior to Marx was capable only of describing the past, and could

not anticipate the future. He viewed this problem as being worsened by capitalism, which turned all

objects into commodities and reified thought. Bloch, who on this point largely follows the views of

Gyrgy Lukcs and the Frankfurt school, believed that reified thought expresses itself as fact-worship,

which is devoid of imagination and incapable of either apprehending the whole or grasping the essential

in the course of history. Koakowski writes that Bloch's comments about non-Marxist philosophies are

little better than casual condemnation and make no attempt at analysis.[2]

Psychoanalysis was seen by Bloch as a negation of the future. Bloch wanted to replace the concept ofthe unconscious with the "not yet conscious", that which is latent within us in the form of anticipation

but is not yet articulate. He was critical of the psychoanalytic unconscious, since he saw it as being

based on accumulations of the past, and therefore containing nothing new. In Bloch's view, this

backward orientation was even more evident in the work of Carl Jung, who interpreted the human

psyche in terms of collective prehistory, than that of Sigmund Freud. Bloch viewed Jung as a fascist,[2]

and related his concept of the collective unconscious to fascist praise for primitive instinct and the will

to power.[3]Alfred Adler's theory of the will to power as a fundamental human impulse was seen by

Bloch as a "typically capitalist idea". Bloch believed that all forms of psychoanalysis were backward

looking because they expressed the consciousness of "the bourgeoisie", a class without a future.[2]Corrington defends Jung against Bloch's criticisms, writing that Bloch fails to recognize that Jung

attempted to balance archetypes against each other precisely to prevent what Bloch saw as the

undesirable consequences of Jungian theory. He states that Marxists such as Bloch are incapable of

recognizing the power of archetypal structures because of the materialism inherent in their framework.[3]

Marxism, according to Bloch, is the only force that has given humanity a full and consistent perception

of the future. Since it recognizes the past only to the extent that it still effects the present, it is entirely

oriented toward the future. Marxism is a science that has overcome the opposition between what is and

what should be: it is both a theory of a future paradise and a method of creating it. Marxism is a utopia,

but one that must be distinguished from the utopias of previous ages because of its concreteness. While

it makes no exact predictions about the future of society, it makes possible conscious participation in the

historical process that leads to the transformation of society. The new society will be free from

alienation and the division of people into classes, and will also achieve the reconciliation of the human

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Augustinehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Junghttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Wilhelm_Friedrich_Hegelhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fascismhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platohttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gy%C3%B6rgy_Luk%C3%A1cshttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philohttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henri_Bergsonhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Adlerhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sigmund_Freudhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anamnesis_(philosophy)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Marxhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankfurt_schoolhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_North_Whiteheadhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unconscious_mindhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitalism -

7/23/2019 Bloch-Principle of Hope summary

3/4

8/11/2015 The Principle of Hope - W ikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Principle_of_Hope 3/4

race with nature. Bloch considered Marx's comments about "humanization of nature" in hisEconomic

and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844to be of key importance: a utopia cannot be concrete unless it

embraces the universe. Utopias that are limited to the organization of society and ignore nature are no

better than abstractions. Marxism's knowledge of this anticipated world and its will to create it have a

counterpart in a higher and more real "essential" order, which is not a perfection already realized

somewhere but invisibly present as an anticipation in the empirical world.[2]

Koakowski, who finds Bloch's concept of non-empirical reality to be typically neo-Platonic andHegelian, writes that Bloch supports it not by appealing to the neo-Platonists or to Hegel, but rather to

the Aristotelian concept of entelechy and the "creative matter" envisaged by Aristotle's followers. Bloch

believed that the world has an immanent purposiveness that leads to the evolution of complete from

incomplete forms. Koakowski writes that while Aristotle's concepts of energy, potentiality and

entelechy are basically intelligible when applied to particular objects and processes, they cannot

intelligibly be applied to reality as a whole. He criticizes Bloch's concepts for being purely speculative

and having no basis in empirical observation. According to Koakowski, Bloch argues that any

objections to the hope of absolute perfection based on existing scientific knowledge are invalid because

"facts" have no ontological meaning. Bloch, recognizing that existing scientific thought does not support

his theories, appeals instead to art and the imagination. Koakowski believes that this approach might bereasonable if Bloch considered himself a poet, but that it is unreasonable given Bloch's claim that his

ideas are in some sense scientific.[2]

Bloch argues that realizing the possibilities inherent in the essence of the universe can only be

accomplished through human will and effort. Whether the universe is destroyed or brought to perfection

depends on the actions of the human race and is not determined in advance. Bloch ascribes to Marx the

idea that the human race is the guide of the universe or of Being as a whole. Koakowski finds that view

to be typically neo-Platonic rather than Marxist, and believes that Bloch can attribute it to Marx only by

distorting Marx's writings. He also believes that Bloch is unclear to what extent the future is contained

within the present: our knowledge of that future may be either real knowledge, or an act of human will.This ambiguity is seen by Koakowski as typical of the Hegelian and Marxist traditions, which blur the

distinction between foreseeing and creating the future. He notes that Bloch attempts to clarify his views

by appealing to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz's "little perceptions", a kind of knowledge that is real even

though inarticulate. Koakowski argues that Bloch's approach is designed to avoid the necessity of

having to provide reasons for his conclusions. He notes that while Bloch believes that the social

organization of his future utopia cannot be described in advance, Bloch nevertheless predicts that it will

contain an entirely new kind of technology that will transform human life.[2]

Bloch believed that while traditional religious beliefs in immortality or reincarnation are pure fantasy,

they are also a manifestation of the utopian will and human dignity. Koakowski interprets Bloch as

arguing that, while the promises of immortality in traditional religions are vain, under communism it

will be possible to overcome the problem of death. Human beings will eventually create God. Bloch

writes that "true Genesis is not at the beginning but at the end". He also believed that socialism would be

able to guarantee Utopia to inorganic nature.[2]

Scholarly reception

Koakowski calls The Principle of HopeBloch's magnum opus, writing that it contains all his important

ideas.[2]The work has been described as "monumental" by philosopher Robert S. Corrington[1]and

psychoanalyst Joel Kovel.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristotlehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Godhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joel_Kovelhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_S._Corringtonhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entelechyhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gottfried_Wilhelm_Leibnizhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_and_Philosophic_Manuscripts_of_1844https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immanence -

7/23/2019 Bloch-Principle of Hope summary

4/4

8/11/2015 The Principle of Hope - W ikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Principle_of_Hope 4/4

References

1. Corrington, Robert S. (1987). The Community of Interpreters: On the Hermeneutics of Nature and the Bible

in the American Philosophical Tradition. Mercer University Press. p. 103. ISBN 0-86554-284-8.

2. Koakowski, Leszek (1985).Main Currents of Marxism Volume 3: The Breakdown. Oxford: Oxford

University Press. pp. 425439. ISBN 0-19-285109-8.

3. Corrington, Robert S. (1992).Nature and Spirit: An Essay in Ecstatic Naturalism. New York: Fordham

University. pp. 6869. ISBN 0-8232-1363-3.

4. Kovel, Joel (1991).History and Spirit: An Inquiry into the Philosophy of Liberation. Boston: Beacon Press.

p. 99. ISBN 0-8070-2916-5.

Retrieved from "https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Principle_of_Hope&oldid=646453959"

Categories: 1954 books 1955 books 1959 books Books by Ernst Bloch

Contemporary philosophical literature Marxist works Social philosophy literature

Philosophy of religion literature Utopias

This page was last modified on 10 February 2015, at 05:06.Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License additional termsmay apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia is aregistered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Standard_Book_Numberhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Philosophy_of_religion_literaturehttps://wikimediafoundation.org/wiki/Terms_of_Usehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/0-8070-2916-5https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/0-19-285109-8https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Standard_Book_Numberhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/0-8232-1363-3https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Standard_Book_Numberhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Help:Categoryhttps://wikimediafoundation.org/wiki/Privacy_policyhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Standard_Book_Numberhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Marxist_workshttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/0-86554-284-8https://www.wikimediafoundation.org/https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:1959_bookshttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Text_of_Creative_Commons_Attribution-ShareAlike_3.0_Unported_Licensehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:1955_bookshttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Social_philosophy_literaturehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Utopiashttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:1954_bookshttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Contemporary_philosophical_literaturehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Books_by_Ernst_Blochhttps://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Principle_of_Hope&oldid=646453959