Asylum Lake fight - Western Michigan University

Transcript of Asylum Lake fight - Western Michigan University

Kalamazoo GazetteAugust 09,2003SectionA 001:1News

.Asylum Lake fightHow a battle over open space nearly stalledKalamazoo's economic engine.

By Julie Mack

It started as a favor, a plea fTomlocalleaders to Western Michigan University. Theyear was 1987. Business leaders, worried

. aboutthe futureof TheUpjohnCo. andGeneral Motors Corp., were anxious todiversify the local economy. Kalamazooofficials were anxious to boost their tax base,especially after voters rejected a city income-tax proposal. They dreamed up a new businesspark and had the perfect site - nearly 600 acresofWMU-owned property along Drake Roadand Parkview Avenue, the city's last large tractof undeveloped land.

In April 1990 WMU unveiled a plan fora business park with an incubation center andan emphasis on research and technology firms,which are generally considered cleaner thanmanufacturing facilities and, consequently,better to put near neighborhoods.

More than 300 acres would bedeveloped on the former Colony Farm Orchardbetween Drake and U.s. 131 and the formerLee Baker Farm south ofParkview. TheAsylum Lake property east of Drake and northofParkview would remain open space.

The business community was thrilled;many neighborhood residents were livid.

"We were surprised by the depth of theopposition and how quickly it built," saidEdward Annen Jr., former Kalamazoo majorand vice major. "It was the issue of open spaceand people saying, 'We walk it, we hike it,'"

Today, 13 years later, the WMUBusiness Technology and Research Park is inplace with six tenants and a businessiO.ncubatorexpected to house a half dozenmore on the former Lee Baker Farm. In

addition, WMU this month will dedicate a new$99 million College of Engineering andApplied Sciences on the south end of theproperty.

The park is a linchpin for future jobgrowth in Kalamazoo County, economicdevelopment officials say. Its importance hasbeen magnified by an unnerving hemorrhage ofjobs in the automotive, pharmaceutical, paperand financial industries.

In its prospects for creating jobs, thepark is touted as a success story, a gleamingarray of new buildings along U.S. 131 thatofficials hope is a harbinger of the county'seconomic revitalization.

Yet there also remains some bitternessabout the project - hard feelings that it took awrenching, decade-long battle before the parkwas built; bitterness that the site is beingdeveloped at all.

Both sides offer the project'scontentious history as a cautionary tale. Forproject supporters, it's about not-in-my-backyard activists blind to economic realities,hurting an entire community in the process. Forcritics, it's about short-sighted governmentofficials gobbling up pristine land and violatingthe public trust

Former City Commissioner Curtis Haanwas among those ftustrated by the delay ingetting the project off the groUnd.

"It put us 10years behind the curve,"said Haan, who was on the commission in theearly 1990s. "The country went through thisbig economic boom in the 1990's and wemissed out on that."

Diether Haenicke, who retired as WMUpresident in 1998, said time has proven himand others right on the necessity for thebusiness park.

"In 1987, we were the Cassandraspredicting a future that would never happen" interms oflocal job losses, he said. "Well, ithappened."

But there are people like city residentRobert Piellusch, who winces whenever hepasses the new business park.

"I'm proud that we tried to stop themonster it's become," he said. "You cansee

© 1970-2004 KALAMAZOO GAZETTEAll rights reserved.Used with permission of KALAMAZOO GAZETTE

once WMU was allowed to go ahead, whatthey did. No more Walden Pond.

"It's just another business parkdevelopment. ... There's brown-fields aplentythey could have used for that."

Prelude to a tussleFrom 1887until the mid-1960s,.

Asylum Lake and Colony Farm Orchard northofParkview served as a diary farm for theKalamazoo Regional Psychiatric Hospital,giving the lake its name. The farm was phasedout when it became cheaper to buy milk thanproduce it, and the dairy barns were tom down.The state deeded the Asylum Lake and Colony

. FarmOrchardpropertyto WMUin the mid1970s, although Michigan State Universityused the 54 acres west Drake Road forpesticide research !Tom1963 to 1988. Deedrestrictions require that both pieces of propertybe used only for recreation.

The 265 acres south ofParkview werefirst settled in 1832, and it was said that EnochHarris, Kalamazoo County's first black settler,was among these who worked the land. Thefarm was eventually purchased by Lee Baker, aWMU agriculture professor who donated theproperty to the university in 1976.

Baker's donation was unrestricted. Thatwasn't true for Asylum Lake and Colony FarmOrchard, which are limited to "recreational oreducational" uses and require legislativeapproval for any construction. Initially, thatwas fine with WMU, which allowed the 274-acre Asylum Lake property to be used forpassive recreational uses such as swimming,hiking, and bird-watching.

"This is open space in the city ofKalamazoo that we hope can be left as openspace," William Kowalski, WMU assistantvice president for administration, said in 1979about Asylum Lake.

That same year, Piellusch moved toMaryland and hung a photograph of AsylumLake in his office.

"I would brag to people that I came!Toma city where there was a place like thisinside the city limits, a place so natural it waslike the Canadian Northwest," said Piellusch,who moved back to Kalamazoo in 1980.

Still, Haenicke was receptive in 1987when approached about the business-park plan.Although "a research park would do very littlefor the university," Haenicke said, it would beWMU's contribution to local economicdevelopment.

WMU gives inThe 1990 development project was

endorsed by the WMU Board of Trustees, theKalamazoo City Commission, the WMUFaculty Committee, the Kalamazoo Board ofRealtors and the CEO Council, thenKalamazoo County's economic developmentarm.

But opposition "grew rapidly. It wasalmost entirely !Tompeople living in ParkviewHills and the Oakwood-Winchellneighborhoods," Annen said. They were aminority in the city, he said, but "a very vocalminority."

"I think Western thought this wouldmove rather smoothly," said city resident MarkHoffinan, one of the leading voices ofopposition. "They miscalculated the reaction ofsurrounding residents."

Dissenters included those who lobbiedfor residential development; those whoaccepted commercial development but fearedpark tenants would be too industrial; otherswho objected when a plan surfaced thatincluded part of the Asylum Lake property.

Then-state Sen. Jack Welborn said theplan violated the deed restrictions for AsylumLake and Colony Farm Orchard. TheKalamazoo Metropolitan Branch of theNational Association for the Advancement ofColored People wanted to preserve Lee BakerFarm because of its link to local black history.Some adamantly opposed development of anysort.

Haenicke believed deeply in the needfor the business park, especially after GeneralMotors announced plans to close its ComstockTownship plant. "We have to aggressively planout future and influence it now before furthercatastrophe strikes," Haenicke told the WMUboard in 1993.

In theory, WMU didn't need localapproval for the business park, at least on Lee

© 1970-2004 KALAMAZOO GAZETTEAll rights reserved.Used with permission of KALAMAZOO GAZETTE

Baker Farm. As a state institution, WMU didnot even need zoning changes. As anotheroption, the university could have sold the landto developers.

In reality, however, WMU was a publicinstitution reliant on public good will - and theuniversity was being pilloried at CityCommission meetings, in letter to the editor inthe Kalamazoo Gazette, and at neighborhoodmeetings, Haan said.

In May 1993, six weeks after WMUtrustees agreed to proceed with Phase 1construction, Haenicke abruptly pulled the plugon the project, citing a "climate of resistanceand hostility."

. "He got tiredof beingbeatenup by theneighborhood groups," Haan said.

The CEO Council then took up thecause, getting permission ftom WMU tomarket the Lee Baker property to businesses,but the group ran into the same wall ofopposition. In 1995, the CEO Council alsodropped the fight. The next year, WMU put asoccer complex on Lee Baker Farm, and it wasclear that opposition still existed to morewidespread development.

Haenicke, who retired in 1998, saidhe's still bitter about the resistance he faced.

"1 could not understand why acommunity in such economic distress didn'twant to be helped, andwhy a relatively smallgroup ruled the day," he said.

'Have you ever seen a cobrafighting amongoose? The cobra goes puff, puff, puff,and when it stops, the mongoose lias it. Wewere the cobra and Western was themongoose. We were so pumped up and thenwe lost steam. 'Prafulla MahantyParkview Avenue resident who foughtdevelopment plans.

The tide turnsWhen Elson S. Floyd took over as

WMU president in 1998, he immediately tooka conciliatory approach.

He took down the brown and gold signsdeclaring Asylum Lake and surroundingproperties reserved for university sports and

recreational use. Neighbors regarded the signsas a move by WMU to underscore its rights tothe property. Furthermore, they perceived thesigns as an in-your-face move to diminish theirrights to public open space.

Floyd pledged to hold public forums toget input on the properties.

"Floyd defused the problem," saidPrafulla Mahanty, a Parkview Avenue residentwho fought development plans. "He played itvery low key. He took the signs out. '" He wasa very good politician."

But Floyd also played a trump card,announcing plans to build a new WMUCollege of Engineering and Applied Sciencesin conjunction with a business park. And hesaid keeping Asylum Lake as open space wascritical to maintaining good communityrelationships. As for the engineering college,he said that was key to both increasing theuniversity's research profile and making theresearch park what it is today.

Forms in the business park must agreeto collaborate with university programs. Thesecollaborations could include research projects,internship opportunities for students, sponsoredprograms and recruitment of students for jobs.

The park "has been a success becausethe university did something fundamentallydifferent," Floyd said. "Usually research parksinvolve seeking private investment withoutpublic investment. So we turned it around andmade a huge public investment and theninvited private investment.

"That's the key ingredient. People mayhave some issues with the cost, but for theeconomic spinoffs that will result, especiallywith what's going on in Kalamazoo right now,it was absolutely the right thing to do."

Barry Broome, chief executive officerof Southwest Michigan First, KalamazooCounty's economic development agency,agreed that putting the engineering college atthe park was a brilliant move.

"The engineering college makes thepark," Broome said. "If it wasn't for theengineering school, it would just be anotherpiece of dirt."

© 1970-2004 KALAMAZOO GAZETTEAll rights reserved.Used with permission of KALAMAZOO GAZETTE

Broome said both Haenicke and Floyddeserve credit for their roles in getting theresearch park developed.

"Diether was a major factor," Broomesaid. "Sometimes it takes 10 years and thepeople standing there at the end get the credit,but Diether deserves a tremendous amount ofcredit."

"What Elson did, in my opinion, he wasa catalyst. He understood what it took to get theproject off the dime."

Lingering emotionsThe battles surrounding the nearly 600

acres haven't completely evaporated. When the. businessparkgot its firsttenant,Richard-Allen

Scientific Co., residents angrily questionedwhether the company would manufacturechemicals that would pollute the air.

A battle continues over putting in pavedtrails, boat launches and other recreationalfacilities at Asylum Lake or leaving theproperty alone. People like Mahanty still thinkthe business park and new engineering campuswere a big mistake and fear their neighborhoodwill be overrun by traffic once classes start atthe WMU Parkview Campus, where 3,000students are expected to attend classes daily.

But even the critics say they hope, nowthat it's there, that the business park will be asuccess. Floyd, who said he "can't take anycredit" for getting the park built, believes theproject is a success already.

"The BTR Park that we have inKalamazoo is really one of a kind," Floyd said."Very few have grown as fast as this one. It's ahuge success story, and I want Kalamazoo toget the recognition for it."

© 1970-2004 KALAMAZOO GAZETTEAll rights reserved.Used with permission of KALAMAZOO GAZETTE

I SPECIAL TO THE GAZEfTE

RobertPiellusch,left, and Mark Hoffman:longtimecriticsofWesternMi~hig~n Univefl)ity:sbusiness1?8rk.re{~~at~

ci l'c c:l~~~ rc c".' ~~ ,"" ,~ aViUwn:;~ ~'c",ca ',' '", )}(i' "'",>,,;;,"",-, ,,",>c C - -- -

© 1970-2004 KALAMAZOO GAZETTEAll rights reserved.Used with permission of KALAMAZOO GAZETTE

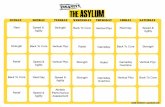

,~. , a~~~~~ehS ~~r;:~.nfacility, the first of the~)

park's t~nar:tts:.Today.heisseVen.tenants who

.Ioeate!n

w

© 1970-2004 KALAMAZOO GAZETTEAll rights reserved.Used with permission of KALAMAZOO GAZETTE

~t:~~o~".bU~!!

.

i"'E'sses and projects"at "estern MichiganUnNerslty's Business

Teflan?logy andRei'$arch Park:

F

Enlneering complex8"'"ege ofEngineering

:I..;.Applied Sciences, .a....OO-square-foot facility~duled for completion

in 4Pmmer2003.O'aper CoatingPilotPla)t,a5O,ooo.square-footfacllJtyscheduled to openFrifAy.

BI'R Park tenantsORich~.Allan Scienti.fiCInc., a120,OOo-square-footfacility,opened in~rlng

.

2002 with about 14.

0 employees.e FluidProcess Equipment Inc., a25,OOO-square-footfacility,opened insummer 2002 with 18 employees.epro UneTechBuilding,a24,OOQ-square-foot, multi-tenant facility.Tenants includeFIshbeck, Thompson, Carr & Huber (since~ne 2002) with20 employe,es;' and ~ASCOTechnologies Corp. (since December 2002)withat leastfiveemployees. .

OGranite Sol~tions, starting constructionthis month, scheduled to move into itsbuilding in 2004 with 30 employees.eWMU's'Energy Resource Cehter,fit12,100-square-feet, opened in spring 2002.A university-operated, natural-gas powerplant.

G Southwest Michigan Innovation Center,a 58,OOO-square-footlife-sciences incuba1Qr.It willbecome home to WMU's BiosciencesResearch and Commercialization Center.The project cof,lld utili~e 25 percent of theInnovation Center. Up to seven companiesled by teams of soon-t~be-~isplaced Pfizer

.scientists could absorb anpther 50 percentof the facility.The balance could be occupiedby other projegts .tf}athave. been hpuaedtemporarily InWMU's McCracken Hall suchas Actives International, which extractsactive ingrec;fients from plants for the

. cosmetic and pharmaceutical industry.

~.\

, L i J

© 1970-2004 KALAMAZOO GAZETTEAll rights reserved.Used with permission of KALAMAZOO GAZETTE