Aquinas-An Examination of his Proofs of the Existence of God_Charles Brand

-

Upload

charles-brand -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

Transcript of Aquinas-An Examination of his Proofs of the Existence of God_Charles Brand

-

8/8/2019 Aquinas-An Examination of his Proofs of the Existence of God_Charles Brand

1/7

ASSIGNMENT REPORT FORMStudent ID58117156

Tutor ID

Name:Date Student sent assignment:Date Received by tutor:Date Sent to Oscail:

Overall Mark

Obtained:

Module:PHIL1Group: 1 TMA No:Summary of Performance*

PerformanceComponents BandsBandsBandsBandsBandsBandsBandsExcellent

(H1)Marksrange:70-100%

Very Good(H2.1)Marks range:60-69%

Good(H2.2)Marksrange:50-59%

Fair(H3)Marksrange:40-49%

WeakMarksrange:35-39%

PoorMarksrange:below35%

Notapplicable

Attention toassignment taskAnalysisStructureUse of sourcesReferencesIntroductionConclusionSpelling/GrammarPresentation (Style)*This table facilitates the assessment of your performance in selected components of your assignment, and is designed to alertyou to the general areas of strength and/ or in need of improvement in your work. Please note that the components are not equalin terms of contribution to your overall mark.Attention to Assignment Task, Analysis and Structure are the three most

important criteria for assessment. Please note that the total mark indicated is based on an evaluation of your overallperformance in the set assignment.

Summary CommentsADVICE FOR FUTURE ASSIGNMENTS

Annotated Feedback

(Refer to Assignment for the sections relating to the following comments)1.2.

Outline Aquinas arguments for the existence of God as postulatedin his Five Ways. Critically analyse whether these Ways are convincing arguments to

prove the existence of God.Introduction

We will begin by outlining Thomas Aquinas' five proofs for the existence of God found inthe SummaTheologiae, part 1, Question2 article 3 (henceforth ST 1a.2.3) without anydetermination on the validity or soundness of the content of the arguments. Then each of the

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ancient-soul/#3.1http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ancient-soul/#3.1http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ancient-soul/#3.1http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ancient-soul/#3.1http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ancient-soul/#3.1http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ancient-soul/#3.1 -

8/8/2019 Aquinas-An Examination of his Proofs of the Existence of God_Charles Brand

2/7

proofs will be examined and analysed in terms of the resilience of their assumptions in light of

subsequent discoveries in the scientific fields of molecular physics, thermodynamics, astrophysicsand quantum physics and the weaknesses these discoveries have exposed in the proofs will be

highlighted. We will then concentrate on the challenges to the proofs from recent philosophical

discourse regarding the general cosmological debate. During this part of the essay we willchallenge some of Aquinas' basic suppositions enshrined in the proofs regarding contingency and

the Causal Principle. We will also attempt to ask some new questions in order to further

encourage discourse on the subject of Aquinas' five proofs and conclude with an explanation ofwhy I feel that Aquinas' proofs, despite the weaknesses demonstrated during the course of theessay, are still very relevant in any discourse around the cosmological argument.The First Way (The Proof from Movement or Change)

The argument from motion is the first proof of the existence of God offered by Aquinas

and he emphasises that his explanation will be based in empirical observation. "It is certain, andevident to oursenses, that in the world some things are in motion" ST 1a.2.3. Aquinas states that things inmotion or changing must be put in motion or changed by something else, or that there must be a

cause for things to be put in motion. He expounds this idea of causality by introducing the idea ofactuality and potentiality, stating that nothing which is in a state of potentiality has the ability to

move to a state of actuality except by something which is already in a state of actuality. Aquinas

demonstrates this through the analogy of fire (which is actually hot) making wood (which has thepotential to become hot) actually hot. This change of state from potentiality to actualitydemonstrates Aquinas' idea of motion insofar as in order for motion to occur something must

acquire a characteristic it did not previously posses.Next Aquinas asserts that something cannot be in both a state of potentiality and

actuality simultaneously ...in the same respect ST 1a.2.3. By this he means that a piece of woodcannot posses the characteristic of being capable of being on fire at the same time as possessing

the characteristic of being on fire since motion or change must consist of the acquisition of acharacteristic not previously held by the subject undergoing change, but the wood can hold the

potential to be on fire and, simultaneously be actually cold since this scenario of possessing bothpotentiality and actuality simultaneously is in different respects. Therefore, according to Aquinas

nothing can change itself or cause itself to be in motion and since this is the case anything whichis changing or in motion must be doing so under the influence of something else. Next Aquinas

claims that if something which is put in motion, or caused to be moved, is itself moving then it

must also have been moved by a previous force and that by a previous force and so on and so on.This causal chain cannot go on indefinitely however since this would eliminate the requirement of

an original cause or force responsible to begin the series and without the original cause or forcenothing would move since nothing would have initiated the beginning of the series. Therefore

Aquinas concludes that there must be an original cause of change or movement which did not

require a cause to move or change. This entity which exists devoid of all potentiality must be theone which we know as God.The Second Way (The Proof from Causation)In the second proof offered by Aquinas he posits the existence of God in much the same way asthe first proof except that he replaces the premise of movement or change with that of causation.

He states that in the observed world there is a serial order to causation and nothing can causeitself for in order to do so it would have to exist before it existed (at least logically, if nottemporally) and this is an impossibility. The next points, those arguing the non-existence of an

infinite series take the same form as the reasons postulated in the first proof and for the samereasons:

An infinite series of causes is an impossibility since All causes follow a series and the beginning of the series is a first cause Without a first cause the is no intermediate cause and no final cause so To remove the first cause is to remove all subsequent causes and This will ultimately remove the final effect but this is false since

-

8/8/2019 Aquinas-An Examination of his Proofs of the Existence of God_Charles Brand

3/7

We observe there are effects so We must conclude there is a first cause and This first cause is known as God.

The Third Way(The Proof from the Contingency of the World)Aquinas begins the third proof for the existence of God by declaring the principle which

underscores the form of the argument;contingency and necessity. This proof involves Aquinas'observation that in the natural world there is a process of things coming into existence and

passing out of existence. According to Aquinas since things do not exist forever; there could havebeen a time when nothing existed but if this were the case then nothing would exist now because

things that exist can only be brought into existence by something already in existence; but as wecan see there are things in existence. From this he concludes that there must be in existence

something which was not brought into being by something already in existence, but instead cameto be from necessity i.e. its existence is not contingent (on the existence of an already existing

being) but necessary. Next, in what seems to be an obvious contradiction, Aquinas states that allnecessary things are themselves either contingent or necessary. Then referring to the Second

Proof he states that the necessity caused in all necessary beings cannot be part of an infiniteseries of causality. Finally Aquinas concludes that a necessary being, responsible for its own

necessity and the necessity in all other necessary beings must exist and this necessary being is

known to men as God.The Fourth Way (The Proof from the Gradation of Things)The forth proof deals with the hierarchical grading of qualities and properties Aquinas observed inthe world. He begins by stating that among beings there are different levels of ...good, true,

noble and the like ST 1a.2.3. He then implies that there is a highest attainable level of allqualities and properties and all gradient levels are relative to this ultimate; as all things hot are

relative to that which is the hottest. Next Aquinas reasons that as there are comparative levels ofhotness and so there are comparative levels of trueness, being best and nobleness, and the most

ultimate being possesses the highest level of truth. Aquinas uses the analogy of fire once more toillustrate his belief that the highest form of any property or quality is that from which all

comparative levels of the quality or property are construed, so all degrees of hotness are relativeto fire since it is responsible for all things being hot. Similarly there must be a being from which

all comparative levels of goodness, truth and all other qualities are derived; that being is known

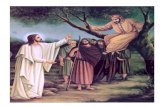

to us as God.The Fifth Way (The Proof from Finality)The final proof of the existence of God sees Aquinas observe all things in the natural world. Heposits that they seem to be guided to attain the best result from their existence. He observes

various animals and that different ...natural bodies... thought to ...lack intelligence... (ST1a.2.3) still seem to behave in the same way, ultimately reaching an end. Aquinas believes that

this is not due to simple good fortune but rather to design. Next he says that these unintelligent

beings could not move towards an end unless they were guided by a being who did possessintelligence and knowledge and uses the analogy of an arrow shot by an archer for illustrative

purposes. He then finally concludes that an intelligent being must exist to provide this direction,this being is called God.Critical Analysis of the Five Ways

Placed within their historical context Aquinas' proofs for the existence of God could make

for a convincing argument in favour of his position. However, since the 13th century advances inthe fields of both science and philosophy have weakened some and deflated other parts of both

-

8/8/2019 Aquinas-An Examination of his Proofs of the Existence of God_Charles Brand

4/7

the form and logic of his proofs. This is not to imply that Aquinas' core assertions have been

disregarded, but they have been honed and developed. We will now scrutinise some of Aquinas'assertions and contrast them with developments in recent scientific and philosophical research.

All five proofs begin with a fact based on experience, namely, that something exists. Inthe first proof Aquinas begins by stating ...whatever is put in motion is put in motion by

another... (ST 1a.2.3). Originating in the Aristotelian understanding of motion as enshrined inPhysics meaning change in position (Locomotion), change in quantity (either moving towards or

away from whatever the absolute value used as a reference) and quality (containing more or lessof a property using an absolute of the quality as a reference) (Aristotle: Book V, chapter 2). But

taking Aquinas' definition of motion and applying to current theories of molecular physics and thelaw of conservation of energy is problematic as physicist Michio Kaku states "gas molecules may

bounce against the walls of a container without requiring anything or anyone to get them moving(Kaku: 1994,194). We see here how advances in the field of molecular physics calls into question

one of Aquinas' basic premises and brings into dispute the requirement for a first mover.The fifth proof, The Proof from Finality can also be juxtaposed with the discourse

apropos emergence and the consequent complexity it actualises. Aquinas' view of the natural

world is illustrated by the following statement and the way in which it metamorphosed from thesimple to the incredibly complex caused him to conclude that it must be guided by God's hand

Now whatever lacks intelligence cannot move towards an end, unless it be directed by somebeing endowed with knowledge and intelligence... (ST 1a.2.3). But there is another

understanding of emergent complexity in both living and non-physical systems which merges thescientific and philosophical positions; and the research and understanding of emergent processes

has been incorporated into many areas of research including the cosmological argument:The emergence perspective offers us ways to think about creation, and creativity, that do not requirea creator. Emergence can be thought of as natures mode of creativity, giving rise to ever morecomplex outcomes by virtue of thermodynamics, morphodynamics, and teleodynamics (Goodenough& Deacon: 2006,865).

So emergence, in terms of the cosmological discussion, brings together the concepts of

thermodynamics and causation. But as we have previously discussed Aquinas' understanding ofmotion is not coherent with our current understanding of the physical laws of thermodynamics. If

gas molecules do not require a first mover for their initial locomotion, then we could posit that thecomplexity of emergent processes do not require guidance by an external force either, but, that

the complex processes shown by the collective of simple forms is self initiating and sustaining.Here we can see the combining of scientific research and philosophical thought pertaining to

emergence theory could undermine Aquinas' requirement for an external guiding force in nature.The first three proofs require an causal explanation for all things in motion, that are

caused and that are contingent; but it could be argued that it is the Proof from Contingency thatis the nexus for all the proofs because if God is not a necessary being then the first mover, first

cause, the being by which all things and qualities are judged and the being which guides allunintelligent things all cease to exist. This does not however mean that the universe would cease

to exist because God is a contingent being, but that the universe is no longer contingent on Godas a necessary being and so there are other possible scenarios:

Both God and the universe are contingent on some necessary being. That the universe is the necessary being and God is a contingent being created at thebeginning of time and space.

Causal principle, what is contingent and what is not are the subject of debate among those

involved in the current cosmological debate. Discussions concerning the origin of the universe(and therefore all things in it) generally begin with an examination of what is commonly referred

-

8/8/2019 Aquinas-An Examination of his Proofs of the Existence of God_Charles Brand

5/7

to as the singularity and the Big Bang. This topic could be viewed as another point at which

philosophy and science intersect.At the instant before the Big Bang is the point of infinite density which is infinitesimally

small called the singularity (Hawking:1988,28). A particular argument in favour of an self-causeduniverse asserts that since the singularity is not governed by physical laws and we know of no

other thing in the universe (so far) that is not governed by any physical laws then we couldassume that the one thing which is does not adhere to any laws is exempt from causality

(Smith:1994,320). Another tranche to Smith's argument ascertains that since ......the big-bang singularity is the simplest possible thing; it has zero spatial dimensions (it is point-like), zero temporal dimensions (it is instantaneous) and is governed by zero laws. It is plausible thatif only one thing can come to be without a cause, this thing will be the simplest possible thing. If thisis the case [...], then the theory that the universe begins with a big-bang singularity will reflect theonly metaphysically possible way in which a universe can come to be uncaused (Smith:1994,321)

So according to Quentin Smith, from a metaphysical perspective the Occam's Razor principle

seems to influence his determination that ifsome thing will come to be, then it will be thesmallest thing possible.The knowledge attained through research in the fields of quantum mechanics and astrophysicswithout which the current hypotheses of The Singularity and The Big Bang could not have been

developed, are central to the recent discourse surrounding causality. Aquinas did not have accessto the current scientific (and subsequent philosophical) discoveries upon which to build his

cosmological argument in terms of causality and infinite regress. Regarding the concepts of

actuality and potentiality we could ask must we presuppose the notion of a beginning, middle andend, and why must the universe conform to this idea? It seems to be the case that it may not and

if this is the case then we must again question whether the foundations of Aquinas' arguments are

completely sound.When we examine the properties of singularity theory in more detail it becomes clear

that it possesses qualities which undermine further some premises held by Aquinas. The first of

these is that an infinite series of regress is an impossibility ...then this also must needs be put in

motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to infinity,... ST 1a.2.3. AsAquinas may have seen it infinite regress was impossible because (1) this removes therequirement of a first mover, (2) without the requirement of a first mover the is no requirement

for God and (3) without a beginning, no series of events could have a middle or end and wouldtherefore not occur at all (Moran:2008,2-6), but what he did not know was that, as quantum

physics hypotheses show, the singularity is a point of no time or space. If we consider this to be

the case we must also consider whether a point of no time or space can exist without beginning orend and do we exclude it from all interpretations of time concluding that if it exists outside of time

is it reasonable to consider it infinite? Again we can see that without the advances in quantumphysics and other not so recent discoveries regarding the very early universe, challenging the

notions that underpin Aquinas' arguments for the existence of God would be much more difficult.Let us examine again Aquinas' assertion that a causal explanation is required for things

in motion, things that are caused and things that are contingent. It could be argued that; confinedby the rigidness of the overall form of his arguments by virtue of his inductive reasoning (that

observed effects affirm a Causal Principle) Aquinas exposes this method to criticism. J.M.Mackie(1982:85) highlights the problem of arguing for the application of the Causal Principle to the

universe from inductive experience. Only through experience is it possible to reason inductively,but is is not possible to experience the universe as a whole therefore we cannot draw conclusions

from an extrapolation of causality beyond experience . David Hume (2007:143) asserts thatattempting to argue in favour of a Causal Principle a prioriresults in a case for conceiving

anything to be so, even though we know it to be false since following this reasoning ...anything

-

8/8/2019 Aquinas-An Examination of his Proofs of the Existence of God_Charles Brand

6/7

may appear able to produce anything. These are philosophical challenges to aspects of Aquinas'

proofs and they are the result of discourse triggered by Aquinas and his attempts to empiricallyprove the existence of God. In so doing however he introduced some other problems.

When examining the proofs from causation, motion and contingency we realise there isfailure to address why God is exempt from requiring a cause, first mover or not a contingent

being. This omission is stark and leaves all three proofs open to the accusation of SpecialPleading; a fallacy occurring when someone argues that a case is an exception to a rule based

upon an irrelevant characteristic that does not define an exception (Cambridge: 2009). If Aquinasis indeed arguing that the special characteristic possessed by God which excludes him from

requiring a cause is the fact that he is God then not only is this a case of special pleading, but alsoa circular argument. Taking into consideration the requirement of a first cause, and accepting that

this is god, there is still no reason put forward by Aquinas that this must be God as he proposeshim to be. Astrophysics has shown that the early universe was nothing more than rudimentary

light and particles (Hawking: 1998,61) we could logically argue that if the early universe that God

created was very rudimentary in nature then God could also have been very rudimentary innature and incapable of creating a universe with the potential to exhibit the complexity of the

present universe?Conclusion

Science it seems has been a tool employed to weaken many of the assumptions made byAquinas in the Proofs for the Existence of God. Also developments in philosophical thought

through the past six hundred years have further served to introduce doubts about some ofAquinas' thoughts on causation and contingency. It seems to be the case that the empirical way in

which Aquinas' sought to underpin his proofs in order to make them as generally acceptable by

the widest audience has ironically become the sword on which they slowly fall. The reasons theproofs have weathered particularly well over such a long time frame are numerous but I believe

there to be one pervading reason; simplicity. The way in which they are written does not impede

one from understanding their meaning. The language is not overly complex and Aquinas does notadopt the use of long streams of complex ideas in order to make his points. These qualities make

the proofs more accessible than other philosophical writings in the cosmological debate and I feelis partly responsible for their popularity and adoption by so many others for many purposes from

the basic conversion of those holding atheist beliefs to the academic wielding of the proofs duringthe philosophical battle of the cosmological argument. Notwithstanding the huge leaps in science

and their impacts on some of the premises found in the proofs, philosophy (in true form) is stilldeciding what the questions should be. As Bruce Reichenbach comments:

...even if the Cosmological Argument is sound or cogent, the difficult task remains to show that thenecessary being to which the cosmological argument concludes is the God of religion, and if so, ofwhat religion (Reichenbach: 2004).

ReferencesBuckle, S. Hume, H. Hume: An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding: And Other WritingsEdition Cambridge: Cambridge University PressDeacon, T.W. Goodenough, U. 2006 The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Science NewYork:Oxford University PressHawking, S. W. 1988A Brief History of Time U.S.A.:Bantam Presshttp://dictionary.cambridge.org/define.asp?key=76283&dict=CALD&topic=debate-and-discussionKaku, M 1994 Hyperspace: a scientific odyssey through parallel universes, time warps, and the

tenth dimension Edition Oxford:Oxford University PressMackie, J. L. 1982 The Miracle of Theism Oxford: Clarendon PressReichenbach, B http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cosmological-argument/

http://dictionary.cambridge.org/define.asp?key=76283&dict=CALD&topic=debate-and-discussionhttp://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cosmological-argument/http://dictionary.cambridge.org/define.asp?key=76283&dict=CALD&topic=debate-and-discussionhttp://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cosmological-argument/http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cosmological-argument/ -

8/8/2019 Aquinas-An Examination of his Proofs of the Existence of God_Charles Brand

7/7

Smith, Quinten 1994 Can Everything Come to Be Without a Cause? Dialogue: Canadian

Philosophical ReviewVolume 33 pp 313-323