Animals, values and tourism — structural shifts in UK dolphin tourism provision

-

Upload

peter-hughes -

Category

Documents

-

view

238 -

download

2

Transcript of Animals, values and tourism — structural shifts in UK dolphin tourism provision

*Tel.: #44-191-515-2730; fax: #44-191-515-2229.E-mail address: [email protected] (P. Hughes).

Tourism Management 22 (2001) 321}329

Animals, values and tourism * structural shifts in UK dolphintourism provision

Peter Hughes*University of Sunderland, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, Priestman Building, Green Terrace, Sunderland, SR1 3PZ, UK

Received 13 November 1998; accepted 29 September 2000

Abstract

General concern for the environment within tourism practices does not guarantee that the rights and welfare of individual animalswill be considered. Indeed, di!erent philosophical positions: environmental ethics, animal welfare and animal rights would each havedi!erent implications if incorporated into tourism development. This paper reports on one case where the deliberate promotion of ananimal rights perspective has brought about a structural transformation in tourism provision. In the UK, over the past ten years, therehas been a complete shift away from viewing dolphins in captivity to viewing dolphins in the wild. This shift is illustrated withreference to the Morecambe Dolphin Campaign of 1989}1991, where animal rights activists brought about the closure ofa dolphinarium through a combination of direct communication with tourists and through lobbying the licensing local authority. Thedi!erent ethical issues associated with the UK's new wild dolphin watching infrastructure are illustrated with particular reference totheMoray Firth, Scotland. The importance of the tourism industry and tourism researchers recognising the signi"cance of animals asindividual actors is highlighted. � 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Animal rights; Animal welfare; Wildlife tourism; Tourism ethics; Dolphins; Moray Firth; Morecambe

1. Introduction

The position, welfare and rights of animals withintourism development are a relatively neglected area (Hall& Brown, 1996). Many of the social sciences and human-ities are currently addressing the implications of theirinherent &speciesism' by creating the space for researchwhich recognises animals as signi"cant actors (Sanders& Hirschmann, 1996; Simons, 1997; Wolch, West,& Gaines, 1995). Existing work within tourism develop-ment studies, while engaged with the broad project ofmapping out the issues arising from the growth in sus-tainable tourism and ecotourism, is largely lacking inanalysis or appreciation of roles played by and responsi-bilities towards individual animals. Even within the areasof wildlife tourism (Shackley, 1996) and ecotourism (Fen-nell, 1999) the di!erent sorts of ethical issues raised bytourist encounters with animals are rarely separated fromthe more general "eld of environmental ethics. Further,

although it is acknowledged that the term &wildlifetourism' should cover both wild and captive situations(Orams, 1996; Shackley, 1996), much of the literature hasfocused solely on the issues arising from people who seekcontact with animals in the wild (for example: Agardy,1993; Davis, Banks, Birtles, Valentine, & Cuthill, 1997;Orams, 1997; Preen, 1998; Russell, 1995).In this paper I aim to explore more fully the implica-

tions for the tourist industries of responding to the chal-lenge of animal welfare and animal rights advocacy. Byreferring to two cases of dolphin tourism in the UK, onecaptive and one wild, I will show how the promotion ofan animal rights perspective has brought about a struc-tural shift in dolphin tourism provision. This is an earlysign for the tourism industry of the power of the animalrights and welfare lobby.

2. Tourism and environmental concerns in the UK

Within the UK, the rise of interest in the environ-mental impacts of tourism, and in the opportunitiesfor nature-based tourism, can be attributed to a growingenvironmental awareness in society. Some people,

0261-5177/01/$ - see front matter � 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.PII: S 0 2 6 1 - 5 1 7 7 ( 0 0 ) 0 0 0 7 0 - 4

agencies and businesses, including those involved intourism, have responded to the second great wave ofenvironmentalism at the end of the 1980s by shiftingtowards a greater degree of environmental responsibilityin their consumption, production and service activities.Alternatively, while organisations for the promotion ofanimal welfare have a longer history than those based onbroader environmental concerns (McCormick, 1989)their speci"c arguments do not appear to have receivedas much consideration within tourism development. Thismay perhaps be attributed to a perception that animalwelfare organisations occupy an extremist position,whereas environmental arguments are more readily ab-sorbed into the mainstream. However, it is business'ability to &greenwash' environmental arguments that hasresulted in, at best, a super"cial incorporation of environ-mental concerns into the activities of the tourist industry.Although the arguments over environmental responsibil-ity are by now well established, only a simplistic readingof the changes that have been occurring within tourismwould be able to suggest that all tourists are now actingwith environmental responsibility, or that all touristproviders have this at the forefront of their concerns. Onthe whole, therefore, Green tourism and mass tourismremain quite distinct sectors. Whether or not tourism isan environmentally responsible practice remains a mat-ter of choice for both the tourists and the providers.Ecologically unsound tourism is still there for those tour-ists that want it, or who do not think about, provided bythose operators who see no advantage or responsibilityin changing their provision. All of the debates over envir-onmental impacts have failed to produce structural cha-nges in tourist provision, or in tourist's values, such thatall tourist experiences are environmentally responsible.However, there is one speci"c aspect of tourist provis-

ion in the UK, the dolphin visitor industry, where sucha structural change appears to have occurred. In thiscase, it is not so much the traditional environmentalargument that has produced change, rather it has beenthe interests, welfare and rights of animals that have beenof key consideration. Within the past 10 years there hasbeen a change from a formal mass tourist provisionbased on viewing captive dolphins performing tricks indolphinaria, to a more alternative tourist provision basedon viewing dolphins in the wild. There are no dolphinarialeft in the UK, but the number of dolphin boat operators,onshore dolphin visitor centres and interpretation sites atcoastal viewing points are on the increase. A key elementof tourist choice in the UK has been removed: tour-ist/dolphin encounters are now only possible in the wild.Here I examine how this change came about. In particu-lar I explore how the promotion of a speci"c animalrights/welfare ethic, rather than more general concernsabout the environment, has played the key role.After outlining some of the debate around animal

welfare, ethics and tourism, the history of two distinct

forms of dolphin tourism: viewing in captivity and view-ing in the wild, is discussed. In particular, an account ofhow these two strands developed in the UK is outlined,before a more detailed discussion of two speci"c cases:Morecambe Marineland and the Moray Firth.

3. Tourism and animals

Animals are incorporated into tourism processes inmany ways. They can be sought out in the wild, capturedand displayed in captivity or utilised as a form of trans-port. In more abstract form they can become a signi"er ofplace, for example on postcards and in brochures, orquite literally consumed as part of the exotic culturalexperience in the form of regionally distinctive food.However, animals are more often objects than subjects intourism. That is, they are more usually manipulated thanrecognised as purposive agents or actors in their ownright. As such they could best be described as havinginstrumental rather than intrinsic value within tourismprocesses; they are recognised for the value which theyprovide for people rather than that which they mightpossess for their own sake. Some attempts to regulateand shape tourist encounters with animals have beenimplemented in, for example, the formation of codes ofconduct and the establishment of accreditation schemesin wildlife tourism (Davis et al., 1997; Fennell, 1999;Malloy & Fennell, 1998; Orams, 1994). While these maybe a sign of a move towards granting animals moralstanding in tourism concerns, that is not necessarily thecase. The key to judging this will be whether animals aregranted individual moral worth, and to clarify where thismay be the case it is necessary to explore the di!erentpositions of environmental ethics and animal welfare andanimal rights perspectives.

4. Environmental ethics, animal welfare andanimal rights * implications for tourism

Recent attempts to introduce a welfare perspective intothe analysis of tourist interactions with host communi-ties, and with the natural environment, have recognisedthe importance of extending our ethical considerationsbeyond people (Hall & Brown, 1996). Within the "eld ofenvironmental ethics, this idea of extending moral con-siderability can be seen as a constantly evolving practice,as people (individually, socially and culturally) movebeyond a solely human-centred perspective. The philos-opher Roderick Nash has suggested that people's values,and with it the range of their moral considerability, startwith themselves before developing to include family,tribe, region, state, race, humanity, non-human animals,plants and "nally, non-living nature (Nash, 1989). WithinNash's scheme, and as shown by his analysis of the

322 P. Hughes / Tourism Management 22 (2001) 321}329

historical extension of considerability, people and socie-ties tend to grant some moral standing to individualanimals before plants or ecosystems. Indeed, debatesover whether animals had any form of moral standingwere quite mature before questions regarding broaderenvironmental ethics began to receive serious attention.More recently though, particularly since the birth of themodern environmental movement in the mid 1960s, con-cerns about animals have either been subsumed withinthe general debate about the environment (for example,as regards whaling or the fur trade) or separated o! asmore marginal or radical (for example, vivisection andfactory farming). With this in mind, it is perhaps notsurprising that concerns about the relationship betweentourist activity and nature has emphasised impacts onlandscape and on environmental quality in general, andsidestepped issues relating to individual animals.Within the literature exploring the questions regarding

the extension of moral considerability to the non-humanworld, it is possible to identify three broad positions:environmental ethics, animal welfare and animal rightsperspectives. For the purposes of this paper, the keydistinction between these rests on their respectivepositions regarding the welfare and moral standing ofindividual animals.One of the foundations of modern environmental eth-

ics is Aldo Leopold's land ethic. This statement positsthat any action is ethically justi"able so long as it doesnot disrupt the integrity of the ecosystem as a whole(Leopold, 1989). It is the ecosystem which has moralconsiderability, rather than its individual constituents(Regan, 1992). Within such a position it would beperfectly acceptable to kill an individual animal, so longas that action did not have wider repercussions thatthreatened the survival of one or more species, forexample through disrupting predator-prey relationships.The systematic destruction of one or more species wouldbe unacceptable.The animal welfare position can be in part consistent

with environmental ethics, in that it also balances theinterests of animals with the interests of people. The maindi!erence though is that the welfare of individual animalsis a signi"cant part of this consideration. An animal'swelfare is compromised when there is some threat ofsu!ering. This su!ering can be induced in captivity or inthe wild. It might result from: human induced injury;spread of disease; the use of &inhumane' methods of cap-ture, trapping or killing; and through disturbance, dam-age or destruction of habitat (Kirkwood, 1992). However,under this perspective, while individual animals mayhave moral considerability, that does not mean that theywould receive the equivalent treatment of humans in thesame position. The animal welfare position is prepared toaccept that some animal su!ering may be justi"ablyincurred if the bene"ts to human welfare, or to the wel-fare of the animal species at large, outweigh the costs

(pain and su!ering) to the individual. As Tom Regan putsit: `...being in support of animal welfare is perfectly con-sistent with utilising animals for human preferences andinterestsa (Regan, 1992, p. 53).Alternatively, proponents of animal rights argue that

any act which adversely a!ects the welfare of an indi-vidual animal is morally wrong (ibid.) and is therefore atleast partly inconsistent with the previous two positions.Animals are granted moral considerability by virtue oftheir sentience; in particular their capacity to feel pain:physical or psychological. Supporters of an animal rightsethic can therefore "nd themselves in con#ict with certaintourism and recreational practices, (Vaske, Donnelly,Wittmann, & Laidlaw, 1995) as will be shown below.The implications of these di!erent philosophical posi-

tions for tourism activity can be illustrated quite simplywith reference to the hunting or culling of animals, or thekeeping of animals in captivity.Hunting and/or culling can be integrated into conser-

vation management regimes that underpin tourism activ-ities. In addition, selling the right to hunt, or to takea trophy, can be part of a tourism development strategy,be it in the Highlands of Scotland, a game ranch in NorthAmerica, or a national park in southern Africa, althoughthe validity of de"ning the killing of an animal as eithersport or recreation is contested (Kheel, 1996). Within thecontext of tourist and animal interactions, big gamehunting and wildlife utilisation in Africa illustrates thisdebate well. Game reserves were established by colonial-ists with a conservation ethic in mind. Indigenouspeoples were translocated in the process, but the popula-tions of particular animals were maintained, albeit fortheir instrumental rather than intrinsic value. More re-cent attempts to make this tourist experience more char-acteristic of sustainable development have focused onrectifying the social and cultural damage in#icted in thepast. Sustainable wildlife utilisation programmes aretherefore judged in terms of their ability to bene"t thelocal community, not in terms of their commitment toindividual animal welfare. Even where tourists hunt withcameras instead of guns, the tourist (wildlife) managerswill be culling animals so that populations remain stable.Under this position, individual animals are sacri"cedfor the greater good. This conservation ethos can beentirely consistent with Leopold's land ethic, as outlinedabove, as the critical factor is the integrity of the ecosys-tem, not the welfare of the individual animal. Animalwelfarists might also support hunting and culling, so longas they were assured that killing was done in a &humane'fashion, and that overall animal welfare would su!er ifconservation regimes were not in place. However, hunt-ing and culling is entirely inconsistent with the animalrights perspective, where the unnatural killing of anyanimal, and the pain in#icted through this act, clearlycontradicts its right not to undergo su!ering and tosimply exist.

P. Hughes / Tourism Management 22 (2001) 321}329 323

Similarly, keeping an animal in captivity might beconsidered just, or unjust, depending on the circumstan-ces and the philosophical position adopted. If captivitywere solely for the purposes of entertainment (forexample, in circuses, bull"ghting or dolphinaria) thenanimal welfarists would generally consider this wrong.Alternatively, if captive display had some broader educa-tional or restorative purpose, then it might be consideredacceptable. Zoos, therefore, might be seen as a validinfringement of individual animal welfare if the purposeof con"nement was to protect and ulimately reintroducea species into the wild, or if there were some educationalelement to captive display, such that the species asa whole were better respected by people. This circum-stance might even be justi"ed under the &land ethic',although another branch of environmental ethics wouldargue that, for example, a condor is meaningless outsideof its natural habitat } in a zoo it ceases to be a condorbecause it can no longer do what a condor does or bewhat a condor is. Quite clearly the animal rights per-spective would reject putting animals in captivity out-right.The purpose of this paper is not to fully explore the

philosophical defensibility of these positions. I merelywish to demonstrate that there is a di!erence betweenenvironmental ethics, animal welfare and animal rightsperspectives. While it is possible to overstate this split(Cooper, 1993; Jamieson, 1998) highlighting the di!eringpositions on the ethics of welfare and su!ering in indi-vidual animals helps to clarify why the incorporation ofsolely an environmental ethic within tourism develop-ment would not necessarily satisfy animal welfare oranimal rights considerations. It will also serve as a usefultool for exploring the ethical debate over the di!erentmodes of dolphin and tourist interaction explored below.

5. Dolphin tourism in captivity and in the wild

Two strands of dolphin tourism have emerged over thelast thousand years. One has capitalised on the tendencyof wild dolphins, either as individuals or as groups, toapparently enjoy, and even seek out, interactions withpeople. The second involves the captive display, trainingand performances of animals before a paying audience.Both of these sets of activities, as they have been incorp-orated into the modern tourism industry, can be analysedin terms of the ethics of the relationship between peopleand individual animals. This paper will show how, withinthe UK, the second strand has been deemed morallyunacceptable, such that the tourism and entertainmentindustries can no longer incorporate it into its provision.The tourist demand for interaction with dolphins isinstead being met with an expanded and formal-ised tourism development of the UK's wild dolphinpopulations.

Orams recently proved an excellent overview of thehistory and current practice of tourist encounters withdolphins in the wild (Orams, 1997). This can be seen aspart of a wider tourism development associated withwhale watching (Du!us, 1996; Du!us and Dearden, 1993;Hoyt, 1994, 1995) which was estimated to be worthUS$504 million worldwide, involving 5.4 million touristsin 1994 (Hoyt, 1995). However, the majority of tourist/cetecea encounters take place in captivity (the nine SeaWorld and Busch Garden parks in the USA alone ac-count for over 21 million visitors a year), so it is impor-tant to outline some of the background to this aspect ofthe industry before exploring both captive and wild dol-phin tourism in two UK based case studies.The history of captive dolphins and whales worldwide

(Johnson, 1990) and in the UK (Klinowska & Brown,1986) has been well documented. The "rst cetecea incaptivity (two white whales) were put on display by P.T.Barnum in 1860 in his American Museum (&freakshow')on Broadway: they died almost immediately. Dolphinswere "rst acquired for display by the New York Aquar-ium in 1913, with the last of "ve dying 21 months later.Marine Studios in Florida took up the tradition in 1938,and it was here that &dolphin dressage' was born: thebeginnings of the trained dolphin acts which are stillperformed in dolphinaria around the world. Between1938 and 1980 the USA alone took over 1500 live dol-phins from the sea, and between 1980 and 1990 Japantook 500 to be used in entertainment. Vancouver Aquar-ium attracted 1 million visitors in 1990 (Kelsey, 1991) andin the same year 40,000 people swam with captive dol-phins in the US (Froho!& Packard, 1995). The Interna-tional Whaling Commission estimates that 4500 ceteceaof various kinds have been displayed in captivity(Johnson, 1990), "gures which don't include the &wastage'that occurs in capture.The dolphinaria industry expanded massively around

the world as the Flipper movie and TV series caught thepopular imagination. By 1965 four dolphin shows ofsome sort had been established in the UK, rising to 25between 1971 and 1975. Most of the dolphinaria wereeither in seaside tourist towns, or were part of a largertourist attraction like a safari park or a theme park.Altogether 41 permanent or temporary sites appearedaround Britain, but by the mid-1980s the number hadfallen to six (Klinowska & Brown, 1986).

6. Animal welfare and animal rights concerns

Animal welfare and animal rights campaigners' con-cerns about dolphinaria rested upon a variety of factors,including:

� the disruption of family groups and wider sophisti-cated social structures during transport;

324 P. Hughes / Tourism Management 22 (2001) 321}329

� death during transport;� in the captive environment: lack of space, sunburn,ingestion of toxic paint in the pool liner, skin peeling inchlorinated water, exposure to human disease andincessant noise pollution;

� encouragement of unnatural behaviour through train-ing methods of food deprivation and reward and,consequently, an overemphasis on entertainment inpublic displays (Johnson, 1990; Pilleri, 1987).

Eventually the UK Department of Environment or-dered a review of conditions in dolphinaria, as concernfor dolphin welfare grew. Despite a call from NGOs likeGreenpeace and Zoo Check (now a division of the BornFree Foundation) to close them down, the o$cial recom-mendations concentrated on reformist measures:minimum pool depths and educational elements toperformance. Based on the distinction between the ani-mal welfare and animal rights perspectives made above,the establishment position settled on the welfare side.This is clear from the emphasis on the reform of captiveconditions, such that the physical and psychological con-ditions of the dolphins would be improved, and also fromthe recommendation for the transformation of the visi-tor/dolphin interaction into an educational experience.Equally clear is the fact that people supporting the ani-mal rights perspective would be dissatis"ed by such a re-sponse. At the end of the 1980s (by which time only fourdolphinaria remained) animal rights activists began totarget campaigns at speci"c dolphinaria: "rstly BrightonAquarium and then Morecambe Marineland.

7. Morecambe Marineland and the Morecambedolphin campaign

While mainstreamNGOs, particularly Zoo Check andthe Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS),continued to monitor and lobby on the issue, it was thegrassroots radical animal rights movement which beganto launch the most concerted and visible campaigns.Most importantly, it was local groups, tackling speci"cdolphinaria, that began to make progress.The Brighton Dolphin Campaign, in late 1980s, suc-

ceeded in raising the pro"le of the issue locally, andgained considerable of public support. However it stalledin its ability to bring about a cessation of dolphin perfor-mances at Brighton Aquarium. It was to prove to beanother local group, the Morecambe Dolphin Campaign(MDC), which would initiate the "rst successful rehabili-tation of a captive dolphin to the wild, and through thatact, ensure the closure of Morecambe Marineland andsignal the end for all other dolphinaria in the UK.Morecambe Marineland was typical of the seaside

aquariums that existed before the new wave of &Sealife'establishments that began to spread through the UK in

the 1990s. Apart from the dolphin exhibitions, which hadbeen in operation since its opening in September 1964,Marineland also had sealions, turtles, alligators andother marine wildlife on display (Klinowska & Brown,1986). The establishment was considered one of the keyelements of Morecambe's tourism portfolio. Although atthe beginning of the 1990s the town was still attractinga signi"cant number of visitors, the economic value oftourism had fallen from C46.6 million in 1973 to C6.5million in 1990 (Williams & Shaw, 1997), making itlargely characteristic of Britain's declining seasideresorts (Urry, 1990). Marineland, as one of the town'sall-weather attractions, was featured prominently in thelocal authority produced annual tourist brochures andwas an established and important part of the local touristeconomy at the time when the Morecambe Dolphincampaign was formed. The campaign focused on thesingle remaining captive dolphin, &Rocky'.The campaign group was based around a core of local

animal rights activists. The winter of 1989/1990 wasspent fundraising, devising a strategy, networking withnational NGOs, and with the Brighton campaign.The campaign strategy had three main elements. First-

ly, there was an attempt to persuade tourists to boycottMarineland. Secondly, there was a goal of persuading theCity Council to remove its tacit and actual support forthe attraction. Finally, there was an aim to givethe campaign a nationwide pro"le, thereby creating anational debate with the hope that the closure of otherUK dolphinaria would be brought about.A picket of the attraction was the foundation for the

rest of the campaign. It was a highly visible action whichsent a clear message to MorecambeMarineland, the CityCouncil and the national NGOs. It also enabled animalrights activists to directly communicate their ethicalstance to Morecambe's tourists. Potential customerswere greeted and had the basis of the protestors' argu-ment outlined to them. The picket was designed to benon-threatening: the aim being to persuade people usingreasoned argument. From the "rst day, well over half thetourists were persuaded not to visit the attraction. As thepicket became more established, and as the activistsbecame more practiced with their arguments, 80}90% ofpotential visitors were being turned away. Thus, theeconomic impact on the attraction was signi"cant. FromEaster, through to the beginning of the summer, the sitewas picketed each weekend and each formal holiday.During the height of the summer season, the campaignerswere present virtually everyday.Once the picket was established, and all parties could

see that the campaign was e!ective and well organised,the City Council were targeted. This part of the campaignwas important because the council issued the licence forthe Marineland operation and devised the tourism bro-chures which featured it so heavily. The MDC's argu-ment was "rstly that, as with many other councils, it

P. Hughes / Tourism Management 22 (2001) 321}329 325

already banned circuses with performing animals fromcouncil-owned land and so support for a dolphinaria wasinconsistent with this. And secondly, that if Morecambetruly wants to modernise its tourist image, it ought to beshifting away from the tacky dolphin shows. MDC "nallywon the right to address a council meeting to put thesearguments directly and to present a petition signed bythousands of tourists and locals supporting the cam-paign. The council was persuaded, and agreed to with-draw the operating license and to cease to promoteMarineland in its tourism brochures.So, by mid-summer the campaign was proving to be

more successful than had been expected. Through the useof ethical arguments aimed at tourists and the localcouncil, a point had been reached where Marineland wasno longer economically viable. Marineland's holdingcompany reached an agreement to sell &Rocky' to thecampaign for a nominal C1. It was at this point that thenational NGOs, particularly Zoo Check, became in-volved more directly, as it was clear that the MDC didnot have the necessary resources to take the campaign toits ultimate conclusion: rehabilitating the dolphin in thewild. So, after negotiation with Zoo Check, a respectedorganisation led by Bill Travers and Virginia McKenna,the national media became involved in a fundraisingcampaign, &Into the Blue'. A million pounds was raised to#y Rocky to a rehabilitation centre in the Turks andCaicos islands, where ultimately he was released backinto the wild (McKenna, 1992). Once Rocky's rehabilita-tion had proved a success, the Brighton dolphins fol-lowed soon after. This left Scarborough's &Flamingoland'and Windsor Safari Park as the only remaining dol-phinaria in the UK. With the moral argument havingbeen so successfully aired at the national level, bothWindsor and Flamingoland sold their animals overseaswithin the next few years as it became clear that theirreputation was becoming tarnished. The success of theMDC therefore resulted in all UK dolphinaria closingdown: a clear example of an ethical argument gainingpublic support and changing the nature of tourismprovision.

8. Viewing wild dolphins in the British Isles

The Morecambe Dolphin campaign might not haveproven so successful had it not been increasingly appar-ent that encounters with wild dolphins were a possibilityin UK and Irish waters. However, the shift towardsviewing dolphins in the wild began to raise di!erentethical issues, for example on issues of feeding, touching,swimming with dolphins, and on the potential impactof boats and boat tours. If dolphinaria have been closeddue to an animal rights and/or welfare ethic, dolphinwatching in the wild might also be assessed in theseterms.

At the time of the campaign, two lone wild sociabledolphins were being featured extensively on nationalmedia: Fungi in Dingle Bay in south-west Ireland, andFreddie, in Amble Harbour, Northumberland. Peopletraveled considerable distances to see, and especially toswim with, both of these dolphins. At Dingle, a consider-able local dolphin tourist infrastructure developed, in-cluding "shing boats taking people out into the harbour,diving equipment hire and a dolphin exhibition. Thisindustry continues to this day. The Amble dolphin, Fred-die, was less internationally famous, but was featured innational media and popular literature in the UK (Will-iams, 1988). The diving community in particular took tovisiting Amble, although Freddie was also a popularattraction for shore-based watchers. For a few years atthe beginning of the 1990s, Amble's tourist economygrew on the strength of the dolphin. In a recent survey ofall the businesses in the town proprietors reported thatturnover had increased during the period and fell backwhen the dolphin died (Kelstrup, 1996).Although the numbers of people travelling to see or to

swim with these two dolphins has probably been smallcompared to those attending dolphinaria in the sameperiod, the cases did serve to highlight the fact that thewaters around the British Isles were dolphin habitat, andthat encounters with wild dolphins were accessible. TheMorecambe dolphin campaigners were able to point tothese examples to demonstrate that a tourist economybased on wild, rather than captive dolphins was possible.Freddie and Fungi also served to bridge the gap betweena formal tourist provision based on viewing captive dol-phins and a formal tourist provision based on viewingthem in the wild. The latter has become a viable optionfor tourists in the UK since the beginning of the 1990s, inthe Moray Firth.

9. Watching wild dolphins in the Moray Firth * thedevelopment of a tourist economy

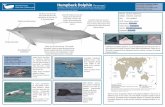

Lone wild dolphins are likely to have only a short-termimpact on a local tourist economy. For the viewing ofwild dolphins to be a long-term alternative to visitingdolphinaria, it is necessary to engage with resident dol-phin populations in their native habitat. In the UK, thereare three major groups: in Cardigan Bay, Wales, inthe Moray Firth, Scotland and a smaller populationo! Devon, Cornwall and Dorset (Simmonds, Irish, &Moscrop, 1997). While all areas exhibit the signs ofdeveloping a local dolphin economy, it is the MorayFirth which has progressed most rapidly (Hughes &Kinnaird, 1997).A population of Atlantic bottlenose dolphins has been

recorded as present in the Moray Firth for over a hun-dred years. There are now thought to be over 130 resi-dent in the area all year round. However, it is only over

326 P. Hughes / Tourism Management 22 (2001) 321}329

the last 10 years or so that these dolphins have beenincorporated into the local tourist economy. One boat-owning family, the Frasers of Cromarty, began takingout their friends in the evenings, before deciding to set upas a tourist oriented business (Fraser, 1997) which ulti-mately became the "rst winner of the Scottish Tourism inthe Environment award (The responsible face, 1996). Asinterest began to grow, more boat operators began o!er-ing dolphin trips to visitors. Most of these new opera-tions represent a form of diversi"cation for businessesalready involved in the tourism sector, for example fromcruise operations on Loch Ness, alongside hotel busi-nesses or as an alternative to angling trips. At the time ofwriting there are two on-shore visitor centres, more than10 individual boat operators and numerous interpreta-tion points on the Moray Firth coast. The seaside townof Nairn has even redesigned its tourist logo to incorpor-ate a dolphin motif. Most recently, alternative tour oper-ators have been o!ering weeklong package trips to seethe dolphins.As the dolphin-watching activity increased, concern

did begin to be expressed about the possible impact ofthis activity on the animals. As one marine biologistworking in the area put it (Thompson, 1992, p. 131):

`Increased public interest in marine mammals is beingparalleled by the realisation that seals and dolphins inScottish waters have great amenity value. Potentialadverse e!ects of disturbance must therefore be takeninto consideration as this sector of the tourist industryexpands.a

In response to these concerns, a voluntary set of guide-lines for regulating encounters between dolphins, touristsand others has been developed (Arnold, 1997).The regulating body responsible for safeguarding Scot-

land's natural environment is Scottish Natural Heritage(SNH), an independent government body which also hasresponsibility for promoting sustainable development(Ross, Rowan-Robinson, & Walton, 1995). SNH has anunusual dual role in that it is both responsible for pro-tecting the environment from insensitive tourism devel-opment, and for encouraging tourism developmentwhich is community based and sympathetic to environ-mental concerns. SNH's handling of the dolphin case iscomplicated by the fact that the Atlantic bottlenose dol-phin is a relatively rare species, and that the Moray Firthdolphinsmake up the most northerly resident populationin Europe. Clearly it is this very fact which alsomakes theanimal so attractive to tourists, what Myra Shackley hastermed the &Galapagos E!ect' (Shackley, 1996). The spe-cies is protected under national, European and globalagreements. The Moray Firth is due to be designateda Special Area of Conservation under the EuropeanUnion's 1992 &Habitats Directive' (92/43/EEC) on thebasis of its dolphin population (Leyshon, 1997; Sim-

monds et al., 1997), although some parts of the localpopulation, and the Highland Regional Council, resistedthis designation on the grounds that it would adverselya!ect local economic development (Dolphin Safety, 1995;Nature heritage, 1995; Protection areas, 1995).In 1993 SNH developed a &Dolphin Awareness Code'

aimed at educating recreational sailing and power boatusers about the possible e!ects of their activities on thedolphins (Arnold, 1997; Leyshon, no date). However, asformal tourism activities began to develop, tourism boatoperators were encouraged to be part of a furtherscheme, the &dolphin space programme' (DSP). The DSPwas developed by SNH in partnership with the ScottishWildlife Trust (SWT) and the European Union LIFEprogramme, which had been set up to fund initiativeswhich might help implement the sustainable develop-ment objectives of the EU's 5th Environmental ActionPlan. A project o$cer was appointed, and a further set ofguidelines developed under advice from University ofAberdeen marine biologists.The &dolphin space programme (DSP) Code of Con-

duct' is similar (and in part derived from) other policiesdeveloped for cetacean-watching in other parts of theworld. However, it is worth reproducing here as it o!ersa clear de"nition of what is considered good and badpractice in human/dolphin interaction, and may there-fore be considered to present in part an ethical stance.The following guidelines make up the DSP:

� Boats should maintain forward progress at a slow,steady speed throughout the trip.

� They should follow an agreed route within the area ofoperation without stops or deviations except for safetyreasons.

� They should always slow down gradually to no wakespeed if cetaceans appear directly ahead and onlyslowly resume cruising speed once clear of the animals.If cetaceans approach the boat or bowride, a slowcruising speed should be maintained.

� The duration, route and number of trips in certainareas sensitive to marine tra$c, such as the KessockChannel and Chanonry Narrows, should be limited.

� Fuel, oil, litter or other contaminants should be dis-posed of in the appropriate containers ashore.

� Passengers or crew should not swim with, touch orfeed dolphins or other marine mammals.

Dolphin boat operators are asked to join the scheme ona voluntary basis, and are awarded a certi"cate and a pen-nant to #y on their boat. In its second year of operation, allof the dolphin boats operating in the Firth were in thescheme, but by the third (1997) boats were beginning towithdraw and the scheme seemed in danger of collapse. Analternative, industry-led voluntary code of practice was indevelopment, and is being promoted amongst all wildlifetour operators in Scotland (Fraser, 1997).

P. Hughes / Tourism Management 22 (2001) 321}329 327

This collapse can be attributed in part to a perceptionthat some of the boat operators have of SNH's role in theaccreditation and monitoring of the scheme. DespiteSNH seeing themselves as merely one of many partners,and as facilitators rather than regulators (Leyshon, 1997),the DSP is seen by at least some boat operators as SNH'sscheme (Fraser, 1997; Gair, 1997). This perception isaccentuated by the widespread feeling in Scotland thatthe agency is biased towards nature and therefore againstthe interests of local populations when there is a poten-tial con#ict between environment and development(Mather, 1993; Barton, 1996; Francis, 1996). It also re-#ects a tension between the science-led regulatory ap-proach implicit in the development and operation of theDSP, and the alternative approach which relies more onlocal lay understanding or folk knowledge and a trust inthe self-regulatory powers of the community (Hughes& Kinnaird, 1997).Anxiety of the potential impacts of tourism activities

on the dolphin population is being expressed by regula-tors, scientists, conservation NGOs and individual boatoperators, but is moral considerability extended to indi-vidual animals? In this instance it is clear that the basicenvironmental value and ethic being expressed throughthe DSP, SNH and scientists operates at the ecosystemand species level. However, in practice the concern forthese wild animals is expressed right down to the level ofindividual animals and therefore contains elements ofanimal rights and welfare positions. Just like captivedolphins they are given names, like &Sundance' and &BenNevis'. These names are based on the scientist's observa-tions, and are reproduced through interpretive materialproduced by scientists (Brough, Thompson, & Wilson,no date). This individualisation is capitalised upon by theWhale and Dolphin Conservation Society in its &Adopta Dolphin Scheme' (Sonar, 1993), which itself part fundsthe activities of marine biologists working in the Firth.Also, while both dolphins and seals compete with thelocal "shing community for salmon stocks, a cull ofdolphins would be considered by all to be unacceptable,while conservationists and "sherfolk alike lobby fora cull of seals. When one of the well-known dolphins diedrecently, &mourning' notices were posted in the mainvisitor centres. It clearly matters whether one individualdolphin dies. Each individual Moray Firth dolphin hasbeen a!orded moral considerablity.

10. Conclusions

Dolphin tourism in the UK represents a clear case ofa branch of the tourism industry which has been struc-turally transformed by responding to concern about thewelfare and rights of individual animals. Tourists andtourism providers have both responded. Dolphinarianow seem untenable in the UK, indeed a proposal for

a new aquarium at Nairn on the Moray Firth deemed itnecessary to declare that it would be unacceptable to keepdolphins in captivity, and that it would instead facilitateviewing of them in the wild from an observation deck.From an animal rights perspective it is clear that

human/dolphin interaction in the wild is the only accept-able form of dolphin tourism. However, the basic ethicalquestions, and the concern for individual animal welfareand rights remain present. If anything, the fact that theMoray Firth dolphins are watched so closely is theirgreatest safeguard. It would seem that a respectful rela-tionship between people and animals is more likely todevelop where they can interact in the &wild' rather than ifthe animals are kept away from people in designatedwilderness preserves (Cooper, 1993).Of course, just because British and other tourists can

no longer see dolphins in captivity in the UK does notmean that in the age of international tourism they cannotsee them elsewhere. Florida and the Mediterranean areboth popular destinations amongst British tourists anddolphinaria are easily accessible. An interesting new de-velopment has seen the British ethical stance reach intothese areas. The UK-based Whale and Dolphin Conser-vation Society has interceded through the EuropeanCommission to halt EU support for the construction ofa dolphinaria in Georgia. It also campaigns against cap-tive cetecea worldwide (Williams, 1996), although the USSea World establishments, with their multinational cor-porate culture (Davis, 1997), are a tough target for activ-ists. This raises other vital questions about the ethics ofimposing, or promoting, the ethics and values of guestsover those of hosts, a phenomenon which has beennoted and criticised in whale watching in Norway (Ris,1993) and in wildlife tourism in southern Africa (Akama,1996). Alternatively, overseas tourism destinations cancapitalise on the UK tourist's perceived ethical stance: inthe late 1990 s Barbados, Australia and Greece all fea-tured encounters with wild dolphins very heavily in theirUK marketing campaigns, but then Florida's captivedolphin shows are also readily apparent in televisionholiday and travel shows.Overall this paper has drawn attention to the fact that

the animal rights and animal welfare lobbies do have thecapacity to in#uence tourism provision. Dolphins areonly one issue. Animal rights and welfare organisationslike People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA)have a whole series of lea#ets and campaigns relating tothe use of animals in the entertainment, leisure andtourism industries. The UK's respected Royal Society forthe Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) also cam-paigns and o!ers advice on being &an animal-friendlytourist'. Tourist operators and managers need to beaware that their activities will be monitored by suchorganisations, and tourism development studies need torecognise the signi"cance of individual animals intourism processes.

328 P. Hughes / Tourism Management 22 (2001) 321}329

References

Agardy, M. T. (1993). Accommodating ecotourism in multiple useplanning of coastal and marine protected areas. Ocean and CoastalManagement, 20(3), 219}239.

Akama, J. S. (1996). Western environmental values and nature-basedtourism in Kenya. Tourism Management, 17(8), 567}574.

Arnold, H. (1997). The Dolphin Space Programme: The development andassessment of an accreditation scheme for dolphin watching boats inthe Moray Firth. Report for the Scottish Wildlife Trust, ScottishNatural Heritage and the EU Life Programme.

Barton, H. (1996). The Isle of Harris superquarry: Concepts of theenvironment and sustainability. Environmental Values, 5(2), 97}122.

Brough, L., Thompson, P., &Wilson, B. (no date).Moray Firth dolphins.Cromarty, Scotland: The Lighthouse Field Station, AberdeenUniversity.

Cooper, D. E. (1993). Human sentiment and the future of wildlife.Environmental Values, 2(4), 335}346.

Davis, D., Banks, S., Birtles, A., Valentine, P., & Cuthill, M. (1997).Whale sharks in Ningaloo Marine Park: Managing tourism in anAustralian protected area. Tourism Management, 18(5), 259}271.

Davis, S. (1997). Spectacular nature: Corporate culture and the Sea Worldexperience. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Dolphin safety zone could hit economy, claims port chief. (1995).Inverness Courier, p. 2.

Du!us, D. (1996). The recreational use of grey whales in the southernClayquot Sound, Canada. Applied Geography, 16(3), 179}190.

Du!us, D., & Dearden, P. (1993). Recreational use, valuation andmanagement of killer whales (Orcinus orca) on Canada's Paci"cCoast. Environmental Conservation, 20(2), 149}156.

Fennell, D. A. (1999). Ecotourism. London and New York: Routledge.Francis, J. M. (1996). Nature conservation and the precautionary prin-ciple. Environmental Values, 5(3), 257}264.

Fraser, B. (1997). Dolphin Ecosse, interview with the author. Cromarty,Scotland, September 4.

Froho!, T. G., & Packard, J. M. (1995). Human interactions withfree-ranging and captive bottlenose dolphins. Anthrozoo( s, 8(1), 44}53.

Gair, S. (1997).Moray Firth Cruises, interview with the author. Inverness,Scotland, September 3.

Hall, D., & Brown, F. (1996). Towards a welfare focus for tourismresearch. Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research, 2, 41}57.

Hoyt, E. (1994). Whale watching and the community: the way forward.Bath, UK: Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society.

Hoyt, E. (1995). The worldwide value and extent of whale watching. Bath,UK: Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society.

Hughes, P., & Kinnaird, V. (1997). Nature/gender/tourism: Watchingdolphins in the Moray Firth, Scotland. Paper presented at the interna-tional conference on gender/tourism/fun?, University of California,Davis, October 24}26.

Jamieson, D. (1998). Animal liberation is an environmental ethic. Envir-onmental Values, 7(1), 41}57.

Johnson, W. (1990). The rose tinted menagerie. London: Heretic Books.Kelsey, E. (1991). Conceptual change and killer whales: Constructingecological values for animals at the Vancouver Aquarium. Interna-tional Journal of Science Education, 13(5), 551}559.

Kelstrup, T. (1996). Animals in tourism: A case study investigation ofAmble, a small Northumbrian coastal town, and Freddie the dolphin.Unpublished dissertation, UK, School of the Environment, Univer-sity of Sunderland.

Kheel, M. (1996). The killing game: An ecofeminist critique of hunting.Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 23, 30}44.

Kirkwood, J. (1992). Wild animal welfare. In R. Ryder (Ed.), Animal welfareand the environment (pp. 139}154). London: Duckworth/RSPCA.

Klinowska, M., & Brown, S. (1986). A review of dolphinaria. London:Department of the Environment.

Leopold, A. (1989). A sand county almanac and sketches here and there.New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leyshon, B. (1997). Scottish natural heritage. Interview with the author.Dingwall, Scotland, September 3.

Leyshon, B. Scottish Natural Heritage's dolphin awareness initiative, Inver-ness. Scotland: Scottish National Heritage, North West Region.

Malloy, D. C., & Fennell, D. A. (1998). Codes of ethics and tourism: Anexploratory content analysis. Tourism Management, 19(5), 453}461.

Mather, A. S. (1993). Protected areas in the periphery: Conservationand controversy in northern Scotland. Journal of Rural Studies, 9,371}384.

McCormick, J. (1989). The global environmental movement. London:Belhaven Press.

McKenna, V. (1992). Into the blue. London: Aquarian Press.Nash, R. (1989). The rights of nature: A history of environmental ethics.Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press.

Nature heritage chief plays down council alarm. (1995). Inverness Cour-ier, p. 3.

Orams,M. B. (1994). Tourism and marine wildlife: The wild dolphins ofTangalooma, Australia: A case report. Anthrozoo( s, VII(3), 194}201.

Orams,M. B. (1996). A conceptual model of tourist-wildlife interaction:the case for education as a management strategy. AustralianGeographer, 27(1), 39}51.

Orams, M. (1997). Historical account of human-dolphin interactionand recent development in wild dolphin based tourism in Austra-lasia. Tourism Management, 18(5), 317}326.

Pilleri, G. (1987). Down with the dolphin zoos! Investigations onCetecea, 20, 283}288.

Preen, A. (1998). Marine protected areas and dugong conservationalong Australia's Indian Ocean coast. Environmental Management,22(2), 173}181.

Protection areas put SNH in "ring line. (1995). Inverness Courier, p. 3.Regan, T. (1992). Animal Rights: What's in a name? In R. Ryder (Ed.),

Animal welfare and the environment (pp. 49}61). London: Duck-worth/RSPCA.

Ris, M. (1993). Con#icting cultural values: Whale tourism in NorthernNorway. Arctic, 46(2), 156}163.

Ross, A., Rowan-Robinson, J., & Walton, W. (1995). Sustainable devel-opment in Scotland: the role of Scottish natural heritage. Land UsePolicy, 12(3), 237}252.

Russell, C. L. (1995). The social construction of orangutans: Anecotourist experience. Society and Animals, 3(2), 151}170.

Sanders, C. R., & Hirschmann, E. C. (1996). Guest editors' introduction:Involvement with animals as a consumer experience. Society andAnimals, 4(2), 111}119.

Shackley, M. (1996).Wildlife tourism. London: International ThompsonBusiness Press.

Simmonds, M., Irish, R., & Moscrop, A. (1997). The dolphin agenda.Bath, UK: Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society.

Simons, J. (1997). The longest revolution: Cultural studies after spe-ciesism. Environmental Values, 6(4), 483}497.

Sonar (1993), Adopt a dolphin project. Sonar, 9, 6}7.The responsible face of nature tourism. (1996). Inverness Courier, p. 4.Thompson, P. (1992). The conservation of marine mammals in Scottishwaters. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 100B, 123}140.

Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze. London: Sage.Vaske, J. J., Donnelly, M. P., Wittmann, K., & Laidlaw, S. (1995).Interpersonal versus social-values con#ict. Leisure Sciences, 17(3),205}222.

Williams, A., & Shaw, G. (1997). Riding the big dipper: The rise anddecline of the British seaside resort in the twentieth century. InG. Shaw, & A. Williams (Eds.), The rise and fall of british coastalresorts (pp. 1}20). London: Pinter.

Williams, H. (1988). Falling for a dolphin. London: Jonathan Cape.Williams, V. (1996). Captive Orcas dying to entertain you! Bath, UK:Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society.

Wolch, J. R., West, K., & Gaines, T. E. (1995). Transspecies urbantheory. Environment and Planning D - Society and Space, 13(6),735}760.

P. Hughes / Tourism Management 22 (2001) 321}329 329