A Valuation Study of Stock Market Seasonality and …2009/10/30 · A Valuation Study of Stock...

Transcript of A Valuation Study of Stock Market Seasonality and …2009/10/30 · A Valuation Study of Stock...

A Valuation Study of Stock Market Seasonality andthe Size Effect

Zhiwu Chen and Jan Jindra

October 30, 2009

Abstract

Existing studies on market seasonality and the size effect are largely based on realizedreturns. This paper investigates seasonal variations and size-related differences in cross-stock valuation distribution. We use three stock valuation measures, two derived fromstructural models and one from book/market ratio. We find that the average valuationlevel is the highest in mid summer and the lowest in mid December. Furthermore, thevaluation dispersion (or, kurtosis) across stocks increases towards year end and reversesdirection after the turn of the year, suggesting increased movements in both the under-and over-valuation directions. Among size groups, small-cap stocks exhibit the sharpestdecline in valuation from June to December and the highest rise from December toJanuary. For most months, small-cap stocks have the lowest valuation among all sizegroups and show the widest cross-stock valuation dispersion, meaning they are also thehardest to value. Overall, large stocks enjoy the highest valuation uniformity and are theleast subject to valuation seasonality.

One of the salient facts in finance is the documented seasonality in stock returns.Specifically, recent losers tend to experience fortune reversals in January (hence, theJanuary effect), whereas recent winners tend to continue and expand their fortunes inDecember (hence, the December effect).1 Most studies on stock market seasonality haverelied on return differences across calendar times. In this paper, we analyze seasonalityfrom a different perspective: cross-sectional valuation movements from one calendar timeto another. Using alternative valuation measures, we investigate how the cross-stockvaluation distributions shift from month to month. Our goal is to study whether suchmonth-to-month variations exhibit any systematic patterns. If seasonal patterns exist,we then want to see whether they can shed new light on the documented January andDecember effects. This approach offers unique insights into the seasonality effects byallowing us to gauge the relative and absolute valuation characteristics of stocks in variousmonths of the year. At the same time, given the documented seasonal return patterns,our study allows us to evaluate alternative valuation measures, with the understandingthat a good stock valuation metric must be able to demonstrate in advance certainseasonal dynamics and predict such return patterns. That is, which valuation measurebest anticipates the return seasonality?

The fact that beaten-down stocks, especially small firms, experience return reversals inJanuary has long been a puzzling phenomenon. There are several proposed explanations,including ”window-dressing” by institutional investors (Lakonishok, Shleifer, Thaler, andVishny [1991]) and the tax-loss selling hypothesis (Grinblatt and Moskowitz [2004]).The window-dressing hypothesis contends that institutional investors sell losers and buywinners to prepare for year-end reporting. Such buying and selling create positive pricepressure on winners and downward pressure on losers before the turn of the year. Asthe selling by institutions stops at year end, prices for beaten-down stocks rebound inJanuary, producing large returns for last year’s losers. The tax-loss selling hypothesisasserts that it is the individual investors faced with capital gains taxation who sell poor-performing stocks to reduce their taxes. To achieve such tax reduction, an investor mustsell the losing stocks before year end as capital losses can be used to offset gains onlyupon realization.2 Both hypotheses predict that losers as of late fall will likely continuegoing lower in December, but will have high returns in January. The window-dressinghypothesis also suggests that strong performers by late fall shall continue going strongin December, which may be a key reason behind the December effect.

The purpose of this paper is to identify and understand what valuation picture isbehind the return seasonality. Such an exercise does not only help deepen our under-standing of the seasonality phenomenon, but also shed new light on the developmentof stock valuation models. Specifically, we implement three valuation measures. Thefirst measure is based on the dynamic stock valuation model developed by Bakshi andChen [2005] and extended by Dong [2000], (“BCD model”). We refer to the percentagedeviation by the market price from a stock’s model valuation as the BCD mispricing.The second measure is the value/price (V/P) ratio, where “value” is determined usingthe residual-income model as implemented in Lee, Myers and Swaminathan [1999]. Thelast measure is the book/market (B/M) ratio, which is a traditional valuation metric.Our results are briefly summarized below:

1

• According to each valuation measure, stocks on average become less favorably val-ued as the year end approaches. In December, stocks are the least favorably val-ued (except that based on the V/P ratio, October/November instead of Decembermarks the lowest valuation month of the year), while stocks reach their highestvaluation in the May-June period. Towards the year end, the cross-stock valuationdistribution also becomes increasingly dispersed and flattened out, with either thestandard deviation or the kurtosis of the valuation distribution growing larger. Thismeans that undervalued stocks become more undervalued whereas overvalued onesbecome more so, implying more differential and uneven treatments of stocks as theyear end approaches. After the turn of the year, all of these valuation trends arereversed.

• Across size groups, small-cap stocks are on average the least favorably valued,followed by mid-cap and then by large-cap stocks. This is true for most calendarmonths. According to each measure, the valuation spread between December andJune is the largest for small-cap and the second largest for mid-cap; Similarly,the December-January valuation spread is also the largest for small-cap. Thus,seasonal valuation patterns are the most severe for small-cap, in terms of changesboth around year end and from year end to mid-year.

• For each given month, the cross-stock valuation distribution is the most widelydispersed (i.e., with the highest standard deviation) for small-cap stocks and theleast dispersed for large-cap stocks. It is again true regardless of valuation measure.

• When we estimate monthly Fama-McBeth cross-sectional return regressions, wefind that the BCD mispricing and size have the highest predictive power, whereasthe V/P and B/M ratios are at best marginal. In particular, the BCD mispric-ing and size are substantially more significant in predicting the mid-December tomid-January returns than in predicting any other monthly returns. The valuationseasonality captured by the BCD model anticipates return seasonalities significantlymore closely than the V/P and B/M ratios.

The findings summarized above are consistent with most returns-based studies onmarket seasonality. The fact that valuation is the lowest in December anticipates the wellknown January return effect. The phenomenon that the valuation distribution becomesmore dispersed towards year end possibly captures two simultaneous, but different trends:tax-loss and window-dressing selling of the losers (making the losers more undervalued)and window-dressing buying of winners (making the winners more overvalued).

We also add a few items to the growing list of conclusions regarding small-cap versuslarge-cap stocks: that most of the year small-cap stocks are the least favorably valued,that their valuation dispersion is the highest, that their June-December valuation pat-terns are the strongest, and that their December-to-January valuation increase is thehighest. These valuation-based findings together suggest that (i) small-cap stocks maysimply be much harder to value and (ii) their mispricing is more difficult to be arbi-traged away. Forces that have been proposed as factors behind these difficulties includeinformational asymmetry, price-impact and trading costs (e.g., Hasbrouk [1991], and

2

Stoll [2000]), liquidity constraints, high information-acquisition costs but low economicbenefits for institutional portfolio managers, and high arbitrage risk (e.g., Wurgler andZhuravskaya [2002]). All these factors favor large-cap and work against small-cap stocks.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Next section discusses the three valuationmeasures and describes the data sample used. The second section documents valua-tion seasonality for the overall sample. In the third section, we divide the sample intothree size groups and address their differences. Section four focuses on Fama-McBethcross-sectional return-forecasting regressions, studying a formal linkage between valua-tion seasonality and return seasonality. Concluding remarks are given in section five.Appendices A and B provide overview of valuation models and their implementation.

VALUATION MEASURES

To make our results independent of a particular valuation model, we use three valuemeasures for each stock: a mispricing measure based on the valuation model in Bakshiand Chen [2005] and Dong [2000] (BCD mispricing), a value/price (V/P) ratio based onthe residual-income model in Lee, Myers and Swaminathan [1999], and book-to-market(B/M) ratio. These value metrics have been applied in the literature and shown to besignificant in predicting cross-sectional stock returns. See, for example, Chen and Dong[2001], Fama and French [1992, 1993], and Lee, Myers and Swaminathan [1999].

The BCD Mispricing

ValuEngine, Inc. provided us with data necessary to calculate the BCD mispricing in thispaper: predicted monthly model prices as well as the concurrent market prices of individ-ual stocks. ValuEngine’s estimation technique is based on the implementation methodused in Bakshi and Chen [2005] and Chen and Dong [2001].3 The BCD model assumesa parameterized stochastic process for each of the firm’s earnings-per-share (EPS), ex-pected future EPS and economy-wide interest rates and leads to a closed-form valuationformula. Appendix A outlines the main points of the BCD model.

It is important to note that the estimation process is independently and separatelyapplied to every stock for each month. For this reason, all model prices used here aredetermined out of sample. For each month and each stock, the BCD mispricing is definedto be the difference between the market and model price, divided by the model price.

The V/P Ratio

The second measure is based on the residual income model as outlined in Lee, Myers, andSwaminathan [1999]. Specifically, we calculate the V/P ratio, where value is determinedby the residual income model and price is taken from the market as of each mid-month.The residual-income model valuation is based on a multi-stage discounting procedurethat involves estimating both the firm’s future EPS in excess of the required return onequity and a terminal value of the stock at the end of valuation horizon. Appendix Bdetails our implementation.

3

B/M Ratio

Market ratios have long been used as indirect measures of value, including book/market(B/M), earnings/price (E/P), cashflow/price, and sales/price. These ratios have beenshown to be significant predictors of future returns.4 Since E/P, cashflow/price andsales/price are generally highly correlated with B/M, we focus on B/M, where the bookvalue of equity is measured once a year at the firm’s fiscal year end, whereas the stockprice is taken at each mid-month. Therefore, there is a monthly B/M value for eachstock.

Data Sample

Four databases are used to estimate the three valuation measures for each stock andin every month. First, we identify all companies with stock price and return data inthe CRSP database. Second, the BCD mispricing data starting in 1977 is provided byValuEngine, Inc. Third, the actual book value data is from COMPUSTAT. Finally, fordetermining each stocks V/P ratio, we use analyst consensus earnings forecasts fromI/B/E/S. Since the I/B/E/S database starts in 1976, our original sample does not startuntil 1976. When it started, I/B/E/S did not cover more than a few hundred large firms.To maintain a robust sample size, we restrict our attention to the 27-year period fromJanuary 1980 to December 2007.

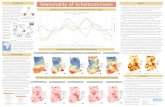

The temporal distribution of the three measures is shown in Exhibit 1. The BCDmispricing sample has 71,392 stock-month observations over the period; The B/M samplehas 105,697 observations, where any observation with either (i) a B/M less than 0.05 orgreater than 30 or (ii) a book value less than $0.1 million is excluded; there are 81,687observations for the V/P ratio sample. The varying sample sizes across the three datasetsreflect the availability of data required for each measure. The sample size for each measurehas steadily increased from 1980 through late 1990’s, due to both the increasing coverageof firms by I/B/E/S and the increasing number of publicly traded firms. Following themarket decline and ensuing consolidation after 2000, all samples decrease correspondingly.

Exhibit 1 also provides summary statistics for each valuation measure, both overthe entire period and year-by-year. Over the entire period, the average estimate forall observations with available data is 1.63% for the BCD mispricing, 84.85% for V/P,and 79.60% for B/M. From 1980 to 2007, both the average valuation and the cross-sectional standard deviation have varied significantly, regardless of the valuation metric.For example, the average BCD mispricing was 5.96% (overvalued) in 1997, the last highestvaluation until the end of the sample; The average V/P continued its downward trendfrom 1994 to 1997, whereas B/M started its down trend in 1990. All measures indicatethat U.S. stocks had become increasingly more overvalued in 2006 and 2007.

SEASONALITY IN VALUATION MEASURES

To examine how the valuation distribution changes from month to month, for each givenmonth of the year and a given valuation metric, we compute the mean, median, standarddeviation, skewness and kurtosis of the metric across all stocks in that calendar month

4

and for all years from 1980 to 2007. That is, we pool together the same-calendar-monthobservations from each year, resulting in 12 calendar-month pools. In total, we obtain12 calendar-month valuation distributions across individual firms.

Exhibit 2 reports valuation statistics for each calendar month. Both the mean andmedian BCD mispricing estimates are the highest in May, implying stocks are on averagethe highest valued during mid-year, with a mean and median mispricing of 4.02% and2.79%, respectively. From May to December, the mean and median BCD mispricing levelsdecrease steadily; Then, from December onward the BCD mispricing reverses directionand rises to approach the highest in May. For a given stock, the average BCD mispricingdifference between December and June is 4.2%. Therefore, stocks are on average the mostunderpriced before year end, with a mean mispricing of -0.72% in December. Januarymarks the beginning of the “correction” process.

The kurtosis of the BCD mispricing also shows a seasonality, increasing each monthfrom October to December, reaching its local high in December. In January, the kurto-sis begins to decrease, reaching its minimum in April. Thus, the cross-stock mispricingdistribution becomes more fat-tailed towards year end than at the beginning of the year.This suggests that as the year end approaches, stocks that are beaten down and under-valued will become even more undervalued, while stocks that are already overvalued willgrow more overvalued. This phenomenon of extremely mispriced stocks becoming evenmore so (on both the under and the over-valued side) is likely due to the working oftwo different factors: one due to performance-chasing at year end by portfolio managersand the other due to tax-loss selling. It anticipates both the December and the Januaryeffect.

Exhibit 3 displays how the fractions of undervalued, fair-valued, and overvalued stocksbased on the BCD mispricing, change from month to month. The undervalued fractionhas a hump-shaped pattern from June to December to May, reaching its peak in Decem-ber, whereas the seasonal variation for the overvalued fraction is U-shaped. On the otherhand, the fair-valued fraction is relatively stable over the year: with around 35% of thestocks fair-valued throughout the year according to the BCD model.5

B/M exhibits similar seasonality as the BCD mispricing. In Exhibit 2, the mean andstandard deviation for B/M start increasing in the summer and reach their peak in De-cember. Thus, again, stocks on average become more undervalued, and the cross-stockvaluation distribution grows more dispersed, as December approaches. For a typicalstock, its average change in B/M is -6.4% from December to June and -4.3% from De-cember to January. The skewness for B/M is the second lowest in December, increasingslightly from November. For V/P, its mean and standard deviation each gradually in-crease from the summer and reach their highest values in October (instead of December),and they start gradually decreasing from October to January.

Based on Exhibits 2 and 3, our conclusions can be summarized as follows. First,regardless of the valuation metric, stocks on average start from year-end’s undervaluationto mid-year’s overvaluation and then back to year-end’s undervaluation again, a seasonalvaluation pattern that anticipates, and is consistent with, the well documented Januarystock-return effect. Second, as the year end approaches, the dispersion of the cross-stock valuation distribution increases, or both tails of the distribution become fatter: theovervalued stocks grow more overvalued and the undervalued become more undervalued.

5

This finding is consistent with both the January effect (which is mostly about movementsin the undervalued tail of the distribution around the turn of the year) and the Decembereffect as documented in Grinblatt and Moskowitz [2004]. The December effect is aboutthe fact that stocks that are winners by the end of November tend to continue doing wellbefore the end of December. Given the relative high correlation between recent returnperformance and overvaluation (the correlation coefficients of BCD mispricing, VP ratio,and B/M with past 12-month momentum is 0.37, -0.15, and -0.16, respectively), thesewinners are also likely to be overvalued in November. Therefore, the December effect isabout how the stocks in the right (overvalued) tail of the mispricing distribution movefrom November to the end of December.

VALUATION SEASONALITY BY SIZE GROUPS

The size effect is another well-documented phenomenon in which small-cap stocks out-perform large-cap stocks (e.g., Banz [1981], Blume and Stambaugh [1983], Fama andFrench [1992, 1993], Keim [1983], and Roll [1983]). Furthermore, there is substantialevidence suggesting that the January effect is largely due to small-cap firms. To help usunderstand the seasonal patterns in valuation, we divide each June’s sample into threesize groups: small-cap, mid-cap and large-cap, each group consisting of 30%, 40%, and30% of that June’s stock universe, respectively. Once the size groups are formed, they arefixed for the next 12 months until the following June when the size groups are re-formed.Within each group, we determine its cross-stock valuation distribution for each monthof the year and according to a given valuation measure. Exhibit 4 shows the resultingseasonal distributions, one panel for each size group.

First, note that in Exhibit 4 the annual re-sorting in June of the stock universe intothree size groups creates noticeable discontinuity from June to July, especially for thesmall-cap group. When stocks are re-grouped according to their market cap in June, thesmall-cap group collects a disproportionately large number of losers. Since those loserstend to be beaten down and hence likely to be undervalued, the average mispricing forthe small-cap group suddenly drops from its pre-sorting level of 3.54% to its post-sortinglevel of 0.17% in July (see Panel A). In contrast, for the mid-cap and large-cap groups,their changes in mispricing are not as dramatic from June to July (Panels B and C).

Panel A of Exhibit 4 shows the seasonal variation in valuation distribution for small-cap stocks. Seasonal changes in average BCD mispricing are much stronger and morepronounced for small-cap than for the overall sample (Exhibit 3). The average BCDmispricing for small-cap is 3.54% in June, but is -3.24% in December, resulting in aDecember-June difference of 6.8%. In contrast, the December-June spread in averageBCD mispricing is 4.2% for the overall sample. By mid-January, the average BCDmispricing jumps to by 3.1% to -0.12% from its December level of -3.24% for small-cap,implying a sharp reversal in valuation from December to January.

Small-cap stocks have the lowest valuation in December according to the B/M ratio,and in October based on the V/P ratio. For these ratios, the change from June toDecember (or, October for the V/P) is gradual, monotonic and highly significant. Theaverage net change in B/M from June to December is 14.2%, while the decline in B/M

6

from December to January is 8.8%, for small-cap, suggesting that most of the year’scorrection in small-cap’s misvaluation occurs in January.

For the mid-cap group in Panel B of Exhibit 4, these stocks also become graduallyless favorably valued going from June towards year end. But, regardless of the valuationmeasure, the change in valuation is not as dramatic from December to June. As notedabove, the average December-June difference in BCD mispricing is 6.8% for small-capfirms, but it is only 3.1% for mid-cap firms. The average December-June difference inB/M is -14.2% for small-cap, but only -5.5% for mid-cap stocks.

According to the BCD mispricing, large-cap stocks still exhibit a seasonal pattern invaluation. In Panel C of Exhibit 4, the average mispricing is 4.50% in July and thengradually goes down to 1.22% by December. The average December-June difference forlarge-cap is only 2.3% in BCD mispricing. Neither V/P nor B/M exhibit a clear seasonalpattern for large-cap stocks.

In summary, small-cap firms show the strongest valuation variations both from mid-year to year-end and around the turn of the year, while large-cap stocks show the least.In fact, according to both B/M and V/P, large-cap stocks have only slight seasonalvariations and these variations even have the wrong sign.

The fact that among all size groups, small-cap stocks have the lowest valuation inDecember is consistent with the extensive evidence that these stocks show the strongestJanuary return effect. As large-cap stocks do not show much seasonal variations invaluation, they should not exhibit much return seasonality either and they do not.

Besides the afore-mentioned difference in valuation seasonality, the valuation distri-bution behaves quite differently among the size groups. We can examine this for eachgiven calendar month, in terms of both the median level and standard deviation of val-uation. First, for each calendar month, the median valuation is the lowest for small-capand the highest for large-cap. For example, in June, the median B/M ratio is 69.54%for small-cap, 61.46% for mid-cap and 57.26% for large-cap. In December, the medianB/M is 79.63% for small-cap, 64.57% for mid-cap and 58.22% for large-cap. The sameobservations can be made based on V/P and, to a lesser degree, on BCD mispricing.The fact that small-cap stocks are consistently less favorably valued than large-caps mayalso explain the persistence of the famous size premium, that is, small stocks on averageoutperform large stocks (e.g., Banz [1981], Grinblatt and Moskowitz [2004], Keim [1983],Loughran and Ritter [2000], and Roll [1983]).

Finally, the cross-stock valuation dispersion (or standard deviation) is the highest forsmall-cap and the lowest for large-cap. For instance, in August, the standard deviationfor BCD mispricing is 28.54% for small-cap, 24.05% for mid-cap and 19.29% for large-capstocks; In November, the standard deviation for B/M is 126.74% for small-cap, 119.10%for mid-cap and 108.66% for large-cap stocks.

This result suggests that small firms are perhaps harder to value and that mispricingfor small-cap is more difficult to be arbitraged away. One explanation may be thatgenerally less information is available about small firms. For example, typically, the largera firm, the more security analysts and portfolio managers following the firm, and hencethe more monitoring and scrutiny of the firm’s activities and news. For large institutionalportfolio managers, it is economically not meaningful to invest in small firms and hencethey may not attempt to gather and process information on these firms. The relative

7

lack of information and the higher information-production costs can be enough to makesmall stocks bounce more easily between different valuation levels. Wider bid-ask spreadsand higher price-impact costs for small-cap firms are also reasons for arbitraging to bedifficult (e.g., Hasbrouk [1991] and Stoll [2000]).

Another explanation is that it is more difficult to find close substitutes for small stocks(Wurgler and Zhuravskaya [2002]). Presumably, when valuation is dispersed across smallstocks, one would want to construct a long-short arbitrage portfolio between the two tailsof the mispricing distribution. Such arbitraging may be the most effective to correct themispricing dispersion. But, since it is difficult to make the long and short sides matchin risk for small-cap stocks, such arbitraging is more risky to do among small-cap thanamong large-cap stocks.

VALUATION AND RETURN SEASONALITY

Using the three valuation measures, the preceding sections have shown that stocks are onaverage the most favorably priced before year end and the least favorably priced in mid-year. Broadly speaking, this valuation seasonality is consistent with the known Januaryeffect, that is, favorable valuations of stocks in December are followed by abnormally highreturns in January. However, we have established this timing consistency between thetwo types of seasonality only at the average stock level and across calendar months. Whatremains to be shown is whether cross-sectionally those stocks that contribute the most tothe January effect are also the most favorably priced in the preceding December. Such anexercise is important because the association between the valuation seasonality and thereturn seasonality could be spurious: even though the average valuation level is the lowestin December, it could happen that stocks that are the most overvalued in December goup in the following January, whereas the undervalued ones stay unchanged or even godown further in January. If that would occur, the average valuation in December wouldbe the lowest and the average January return could still be abnormally high, but the lowDecember valuation would not be the cause behind the high average January return. Torule out such a possibility, we estimate Fama-McBeth return-forecasting regressions inthis section.

Exhibit 5 serves to provide a general picture of the predictive power by differentvaluation measures and size. For this part, we include all months as well as Decemberonly cross-sectional regressions. In the univariate regressions (not shown), each of theBCD mispricing and V/P ratio is a statistically significant predictor of future stockreturns, implying that the more favorably priced a stock, the higher its future one-monthreturn. When all the valuation measures and size are included in a joint forecastingRegression 1, only BCD mispricing, V/P and size are significant and their respectivecoefficient estimates are of the correct sign, whereas the B/M ratio’s coefficient has thewrong sign.

To establish that the valuation seasonality anticipates the return seasonality, we areinterested in the December results as the January effect is the major contributor to stockreturn seasonality. Recall that because of the mid-month sampling practice by I/B/E/S,most empirical results of this paper are based on the mid-month value for each measure

8

and mid-month to mid-month returns. Therefore, the December regression results arefrom using the mid-December to mid-January returns as the dependent variable, hencecovering a crucial time period for the January effect. Thus, the December regressionresults should be the most informative of which ex ante variables are the most predictiveof high January returns.

Based on the December results in Regression 2 in Exhibit 5, BCD mispricing and firmsize are the most significant in predicting a stocks up-coming January return: the moreunderpriced a stock in mid December and/or the smaller the firm, the higher its returnover the next month. In unreported regressions for each calendar month, we note thatboth the magnitude and t-statistic for these two variables’ coefficient estimates are thehighest for December than for any other calendar month. Thus, the return-based sizeeffect is mostly due to the month of January and the low December valuation (a resultconsistent with the findings in Blume and Stambaugh [1983] and Keim [1983]).

The results in Exhibit 5 suggest that tax-loss-selling may not explain all of the Januaryeffect or the size effect. Note that if the year-end tax-loss-selling were the exclusivereason behind the January effect, then the high January returns must be exclusively dueto “valuation corrections” and one would expect the valuation factors to be the onlysignificant predictors of the January effect. In this sense, we can think of the valuationfactors in Exhibit 5 as capturing the tax-loss-selling effect.6 For the regressions, we haveincluded all of the BCD mispricing, V/P and B/M, as these are the known valuationmeasures in the literature. The fact that both BCD mispricing and size are significant injointly explaining the January effect implies that while tax-loss-selling (i.e., the valuationfactor) is a major reason, it is not the only reason behind the high January returns. Sizeappears to capture something beyond the correction of the mis-valuation caused by tax-loss-selling.7

It is worth noting that the BCD mispricing reflects more of a stock’s current valuationrelative to its own past valuation levels, and this “mispricing” assessment is completelyindependent of how other stocks are and have been valued. On the other hand, the sizefactor, when defined by market capitalization, is a cross-sectional variable and serves as aproxy for factors that set firms of different sizes apart and that are not yet known. Thatis, the BCD mispricing captures the stock’s “temporal” variation in valuation, whereassize is a cross-sectional measure. This may explain why both valuation and size aresignificant predictors of the January return effect.

In Exhibit 5, we also divide the sample into three size groups and run the same Fama-McBeth regressions separately for each group. The size-based results re-confirm the abovefinding about BCD mispricing and size. Within each size group and among all calendarmonths, the BCD mispricing, V/P and B/M are statistically significant predictors offuture one-month returns (Regressions 3, 5 and 7). In predicting the January effectwithin the size groups, BCD mispricing and size are significant (Regressions 4, 6 and 8).

The fact that BCD mispricing predicts future returns, and explains the January effect,better than V/P and B/M supports the BCD model valuation as a better measure of astock’s value. The persistence of stock return seasonality is a phenomenon indicative ofregularly recurring mis-valuation by the market, and any empirically acceptable valuationmodel must produce a mispricing pattern that is consistent with, and predicts, the returnseasonality. Among the three valuation measures implemented in this paper, the BCD

9

model has performed the best in this regard.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The focus of this paper has been on documenting and understanding seasonal valuationpatterns for stocks. This is in contrast with most existing studies on stock market season-ality where the focus has been on observed return patterns. When researchers first startedinvestigating stock market seasonality, the most natural and direct approach was clearlyto use realized returns across calendar times as the basis. A return-focused approach isin some sense free of valuation models, hence not subject to model misspecifications.

Given the abundant evidence for return seasonality, it has been a challenge to finda fundamental economic explanation. Window-dressing and tax-loss selling are amongthe front runners in this direction. While the true cause for return seasonality may bewindow-dressing and/or tax-loss selling and possibly others, for asset valuation theoryitself the challenge still remains: how can valuation theory capture and reconcile suchreturn seasonality from a modeling perspective?

In this paper, we have relied on two recent stock valuation models, the BCD modeland residual income model, and one indirect valuation metric, B/M, to study marketseasonality. Our finding indicates that regardless of the valuation measure, stocks areon average the least favorably priced towards year end and the most overvalued in mid-summer. The correction process of December’s low valuation starts in mid-December,accelerates in early January, and ends by March, after which point stocks tend to beginan overvaluation season of the year. Another important finding concerns the differencesacross size groups. For small-cap, the valuation seasonality is by far the strongest andthe January valuation correction is also the sharpest. For most of the year, small-capstocks are the least favorably valued with the widest valuation dispersion, while large-cap stocks are the most favorably priced with the lowest dispersion. Overall, our studysuggests that the BCD model captures a stock’s true value better than V/P and B/M.

APPENDIX

A The BCD Model

For detailed derivations and discussions of this stock valuation model, see Bakshi andChen [2005] and Dong [2000].

To describe the BCD model, assume that a share of a firm’s stock entitles its holder toan infinite dividend stream {D(t) : t ≥ 0}. Our goal is to determine the time-t per-sharevalue, S(t), for each t ≥ 0. Bakshi and Chen [2005] make the following assumptions:

• The firm’s dividend policy is such that at each time t

10

D(t) = δ Y (t) + ε(t) (A-1)

where δ is the target dividend payout ratio, Y (t) the current EPS (net of all ex-penses, interest and taxes), and ε(t) a mean-zero random deviation (uncorrelatedwith any other stochastic variable in the economy) from the target dividend policy.

• The instantaneous interest rate, R(t), follows an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck mean-revertingprocess:

dR(t) = κr

[µ0

r −R(t)]

dt + σr dωr(t) (A-2)

for constants κr, measuring the speed of adjustment to the long-run mean µ0r, and

σr, reflecting interest-rate volatility. This is adopted from the well-known single-factor Vasicek [1977] model on the term structure of interest rates.

In Bakshi and Chen [2005], the assumed process for Y (t) does not allow for negativeearnings to occur. To resolve this modeling issue, Dong [2000] extends the originalBakshi-Chen earnings process by adding a constant y0 to Y (t):

X(t) ≡ Y (t) + y0 (A-3)

X(t) can be referred to as the displaced EPS or adjusted EPS. Next, Dong [2000]assumes that X(t) and the expected adjusted-EPS growth, G(t) follow

dX(t)

X(t)= G(t) dt + σx dωx(t) (A-4)

dG(t) = κg

[µ0

g −G(t)]

dt + σg dωg(t) (A-5)

for constants σx, κg, µ0g and σg, where G(t) is the conditionally expected rate of

growth in adjusted EPS X(t). The long-run mean for G(t) is µ0g, and the speed at

which G(t) adjusts to µ0g is reflected by κg. Further, 1

κgmeasures the duration of the

firm’s business growth cycle. Volatility for both the adjusted-EPS growth and changesin expected adjusted-EPS growth is time-invariant. The correlations of ωx(t) with ωg(t)and ωr(t) are respectively denoted by ρg,x and ρr,x.

Under the given model assumptions, the equilibrium stock price is

S(t) = δ∫ ∞

0{X(t) exp [ϕ(τ)− %(τ) R(t) + ϑ(τ) G(t)]− y0 exp[φ0(τ)− %(τ)R(t)]} dτ

(A-6)where

ϕ(τ) = −λxτ +1

2

σ2r

κ2r

[τ +

1− e−2κrτ

2κr

− 2(1− e−κrτ )

κr

]− κrµr + σxσrρr,x

κr

[τ − 1− e−κrτ

κr

]

11

+1

2

σ2g

κ2g

[τ +

1− e−2κgτ

2κg

− 2

κg

(1− e−κgτ )

]+

κgµg + σxσgρg,x

κg

[τ − 1− e−κgτ

κg

]

−σrσgρg,r

κrκg

{τ − 1

κr

(1− e−κrτ )− 1

κg

(1− e−κgτ ) +1− e−(κr+κg)τ

κr + κg

}(A-7)

%(τ) =1− e−κrτ

κr

(A-8)

ϑ(τ) =1− e−κgτ

κg

(A-9)

φ0(τ) =1

2

σ2r

κ2r

[τ +

1− e−2κrτ

2κr

− 2(1− e−κrτ )

κr

], (A-10)

subject to the transversality conditions that

µr >1

2

σ2r

κ2r

(A-11)

µr − µg >σ2

r

2 κ2r

− σrσxρr,x

κr

+σ2

g

2κ2g

+σgσyρg,x

κg

− σgσrρg,r

κgκr

− λx (A-12)

where λx is the risk premium for the systematic risk of earnings shocks, µg and µr arethe respective risk-neutralized long-run means of G(t) and R(t). Formula (A-6) representsa closed-form solution to the equity valuation problem, except that its implementationrequires numerically integrating the inside exponential function. Therefore, the equilib-rium stock price is a function of interest rate, current EPS, expected future EPS, thefirm’s required risk premium, and the structural parameters governing the EPS and in-terest rate processes. We refer to this stock-pricing formula as the Bakshi-Chen-Dong(BCD) model.

In the original research by Bakshi and Chen [2005], the structural parameters neededto be estimated. To reduce the number of parameters to be estimated, the followingparameters were preset ρg,x = 1 and ρg,r = ρr,x ≡ ρ, that is, actual and expectedadjusted-EPS growth rates are subject to the same random shocks. In addition, for eachindividual stock estimation, the three interest-rate parameters are preset at µr = 0.0794,κr = 0.109, σr = 0.0118. These parameter values are based on a maximum-likelihoodprocedure using a 30-year yield time-series (Bakshi and Chen [2005]). A justification forthis treatment is that the interest-rate parameters are common to all stocks and equityindices. Note that these estimates are comparable to those reported in Chan, Karolyi,Longstaff, and Sanders [1992]. Then, there are 8 firm-specific parameters remaining tobe estimated: Φ = {y0, µg, κg, σg, σx, λx, ρ, δ}. At each time point of valuation, the mostrecent 24 monthly observations on a stock (and interest rates) are used as the basis toestimate Φ (see Chen and Dong [2001] for details on this choice). Specifically, for eachstock and for every month in the sample, Φ is chosen so as to solve

MinΦ

24∑

t=1

[ S(t)− S(t) ]2 (A-13)

12

where S(t) is as given in formula (A-6) and S(t) the observed market price in montht.

Once the parameters are estimated for a given stock and in a given month (usingdata from the prior years), the parameter estimates, plus the current R(t), Y (t) and G(t)values, are substituted into formula (A-6) to determine the current model price for thestock in that month. After the model price is calculated for the stock in that month, theparameter estimation steps and the calculation are repeated for the same stock, but forthe following month and so on. This process is independently and separately applied toevery stock in the sample and for each month. For this reason, all the model prices aredetermined out of sample.

B The Residual Income Model

A stock’s intrinsic value is defined as the present value of the expected future cash flowsto shareholders:

V (t) =∞∑

i=1

Et(D(t + i))

(1 + re)i(B-1)

where Et(D(t + i)) is the expected future dividend for period t + i conditional on allavailable information at time t, and re is the cost of equity. Ohlson [1990, 1995] demon-strates that if the firm’s earnings and book value are forecasted in a manner consistentwith clean-surplus accounting (i.e. a dollar of earnings increases either dividends paidout or book value by a dollar), the intrinsic value may be rewritten as:

V (t) = B(t) +∞∑

i=1

Et [NI (t + i)− reB(t + i − 1 )]

(1 + re)i(B-2)

= B(t) +∞∑

i=1

Et [(ROE (t + i)− re)B(t + i − 1 )

(1 + re)i(B-3)

where B(t) is the book value at time t, Et[NI(t + i)] and Et[ROE(t + i)] are theconditional expectations of both net income and after-tax return on book value of equityfor period t + i.

The above equation expresses a stock’s intrinsic value in terms of an infinite sum.However, for practical purposes, only limited future earnings forecasts are available. Thislimitation introduces a need for an estimate of a terminal value. That is, we measure theintrinsic value in the following way:

V (t) = B(t) +2∑

i=1

EPS (t + i)− reB(t + i − 1 )

(1 + re)i+ TV (B-4)

where EPS(t) is the consensus earnings forecast for period t, and TV is the terminalvalue estimate based on the average of the last two years of data (in order to smoothcases of unusual performance in the last year, D’Mello and Shroff [2000]):

13

TV = B(t) +1

2re(1 + re)2

3∑

i=2

EPS (t + i)− reB(t + i − 1 )

(1 + re)2 (B-5)

When implementing the model, we estimate the current book value per share, B(t),from the most recent financial statement. Book value for any future period t+ i, B(t+ i),is given by the beginning-of-period book value, B(t + i − 1), plus the forecasted EPS,EPS(t + i), minus the forecasted dividend per share for year t + i. The forecasteddividend per share is estimated using the current dividend payout ratio. The forecastedearnings per share, EPS(t + 1), are given by the analyst consensus forecast for therelevant year and as reported in I/B/E/S. The cost of equity capital, re, is estimatedusing the CAPM and following Fama and French [1997]: 60 monthly observations priorto the month of estimation are used to estimate the stock’s beta, and then the cost ofequity capital is determined by the market T-bill rate of the month plus the beta timesthe market risk premium, where the market risk premium is the average excess returnon the NYSE/AMEX/Nasdaq portfolio from January 1945 to month t-1.

ENDNOTES

Zhiwu Chen is a Professor of Finance at Yale School of Management, 135 ProspectStreet, New Haven, CT 06520, [email protected], Tel. (203) 432-5948; Jan Jindrais an Assistant Professor at Menlo College, 1000 El Camino Real, Atherton, CA 94025,[email protected] and telephone: (650) 804-6807.

The authors would like thank ValuEngine, Inc. for graciously providing data used toestimate BCD mispricing. Any errors are our responsibility alone.

1The January effect has been documented by Rozeff and Kinney [1976], Dyl [1977],Roll [1983], Keim [1983,1989], Reinganum [1983] and others. Grinblatt and Moskowitz[2004] find such a December effect.

2Sikes [2008] finds calendar year end stock return patterns for stocks with negativeyear-to-date returns are related to year end changes in ownership of institutions withincentives to sell such stocks for tax purposes.

3See http://www.valuengine.com/pub/main?p=0.4For example, Daniel and Titman [1997], Davis, Fama, and French [2000], Fama and

French [1992,1993,1995,1996,1997], Frankel and Lee [1998], Jegadeesh and Titman [1993],Lakonishok, Shleifer, and Vishny [1994], Grinblatt and Moskowitz [1999].

5As a robustness check, we also examine the distribution of the undervalued, fair-valued, and overvalued stocks for a period prior to 1998. For this earlier period, thepatterns in the distribution of undervalued and overvalued stocks are even more pro-nounced.

14

6This reasoning can be best seen in Roll [1983, p. 20]: “There is downside pricepressure on stocks that have already declined during the year, because investors sellthem to realize capital losses. After the year’s end this price pressure is relieved and thereturns during the next few days are large as those same stocks jump back up to theirequilibrium values.”

7Reinganum [1983] constructs a measure of a stock’s tax-loss-selling potential, to studythe extent to which the January effect is due to tax-loss-selling. He concludes that aftercontrolling for tax-loss-selling, firms still exhibit a January seasonal effect that seems tobe related to market capitalization. In our case, we use mid-December’s valuation as aproxy for the extent of tax-loss-selling potential.

15

REFERENCES

Bakshi, Gurdip and Zhiwu Chen, ”Stock Valuation in Dynamic Economies.” Journal ofFinancial Markets, 8 (2005), pp. 115-151.

Banz, Rolf W., ”The Relationship Between Return and Market Value of Common Stocks.”Journal of Financial Economics, 9 (1981), pp. 3-18.

Blume, Marshall and Robert Stambaugh, ”Biases in Computed Returns: An Applicationto the Size Effect.” Journal of Financial Economics, 12 (1983), pp. 387-404.

Chan, K.C., Andrew Karolyi, Francis Longstaff, and Anthony Sanders, ”An EmpiricalComparison of Alternative Models of the Short-Term Interest Rate.” Journal of Finance,47 (1992), pp. 1209-1227.

Chen, Zhiwu and Ming Dong, ”Stock Valuation and Investment Strategies.” Workingpaper, Yale University, 2005.

Daniel, Kent and Sheridan Titman, ”Evidence on the Characteristics of Cross SectionalVariation in Stock Returns.” Journal of Finance, 52 (1997), pp. 1-34.

Davis, James L., Eugene Fama, and Kenneth French, ”Characteristics, Covariances, andAverage Returns: 1929-1997.” Journal of Finance, 55 (2000), pp. 389-406.

D’Mello, Ranjan and Pervin Shroff, ”Equity Undervaluation and Decisions Related toRepurchase Tender Offers: An Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Finance, 55 (2000),pp. 2399-2424.

Dong, Ming, ”Stock Valuation with Negative Earnings.” Working paper, Ohio StateUniversity, 2000.

Dyl, Edward, ”Capital Gains Taxation and Year-End Stock Market Behavior.” Journalof Finance, 32 (1977), pp. 165-175.

Fama, Eugene and Kenneth French, ”The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns.”Journal of Finance, 47 (1992), pp. 427-465.

–. ”Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds.” Journal of FinancialEconomics, 33 (1993), pp. 3-56.

–. ”Size and Book-to-Market Factors in Earnings and Returns.” Journal of Finance, 50(1995), pp. 131-156.

–. ”Multifactor Explanations of Asset Pricing Anomalies.” Journal of Finance, 51 (1996),pp. 55-84

–. ”Industry Costs of Equity.” Journal of Financial Economics, 43 (1997), pp. 153-194

Frankel, R. and C. Lee, ”Accounting Valuation, Market Expectation, and Cross SectionalStock Returns.” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25 (1998), pp. 283-319.

16

Grinblatt, Mark and Tobias J. Moskowitz, ”Do Industries Explain Momentum?” Journalof Finance, 54 (1999), pp. 1249-1290.

–. ”Predicting Stock Price Movements from Past Returns: The Role of Consistency andTax-Loss Selling.” Journal of Financial Economics, 71 (2004), pp. 541-579.

Hasbrouk, Joel, ”Measuring the Information Content of Stock Trades.” Journal of Fi-nance, 46 (1991), pp. 179-207.

Jegadeesh, N. and Sheridan Titman, ”Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers:Implications for Stock Market Efficiency.” Journal of Finance, 48 (1993), pp. 65-91.

Keim, Donald, ”Size Related Anomalies and the Stock Return Seasonality: FurtherEmpirical Evidence.” Journal of Financial Economics, 28 (1983), pp. 67-83.

–. ”Trading Patterns, Bid-Ask Spreads, and Estimated Security Returns: The Case ofCommon Stock at Calendar Turning Points.” Journal of Financial Economics, 25 (1989),pp. 75-97.

Lakonishok, Josef, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny, ”Contrarian Investment, Extrap-olation, and Risk.” Journal of Finance, 49 (1994), pp. 1541-1578.

Lakonishok, Josef, Andrei Shleifer, Richard Thaler, and Robert Vishny, ”Window Dress-ing by Pension Fund Managers.” American Economic Review, 81 (1991), pp. 227-231.

Lee, Charles, James Myers, and Bhaskaran Swaminathan, ”What Is the Intrinsic Valueof the Dow?” Journal of Finance, 54 (1999), pp. 1693-1741.

Loughran, Timothy, ”Book-to-Market Across Firm Size, Exchange and Seasonality: IsThere an effect?” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 32 (1997), pp. 249-268.

Loughran, Timothy and Jay R. Ritter, ”Uniformly Least Powerful Tests of Market Effi-ciency.” Journal of Financial Economics, 55 (2000), pp. 361-390.

Ohlson, James A., ”A Synthesis of Security Valuation and the Role of Dividends, CashFlows, and Earnings.” Contemporary Accounting Research, 6 (1990), pp. 648-676.

–. ”Earnings, Book Values, and Dividends in Equity Valuation.” Contemporary Account-ing Research, 11 (1995), pp. 661-687.

Reinganum, Mark, ”The Anomalous Stock Market Behavior of Small Firms in January:Empirical Tests for Tax-Loss Selling Effects.” Journal of Financial Economics, 12 (1983),pp. 89-104.

Ritter, Jay R., ”The Buying and Selling Behavior of Individual Investors at the Turn ofthe Year.” Journal of Finance, 43 (1988), pp. 701-717.

Ritter, Jay R. and Navin Chopra, ”Portfolio Rebalancing and the Turn of the YearEffect.” Journal of Finance, 44 (1989), pp. 149-166.

17

Reinganum, Marc R., ”The Anomalous Stock Market Behavior of Small Firms in January:Empirical Tests for Tax-Loss-Selling Effects.” Journal of Financial Economics, 12 (1983),pp. 89-104.

Roll, Richard, ”Vas ist das? The Turn-of-the-Year Effect and the Return Premia of SmallFirms.” Journal of Portfolio Management, 9 (1983), pp. 18-28.

Rozeff, M. S. and W. R. Kinney, Jr., ”Capital Market Seasonality: The Case of StockReturns” Journal of Financial Economics, 3 (1976), pp. 379-402.

Sikes, Stephanie A., ”The January Effect and Institutional Investors: Tax-Loss Sellingor Window-Dressing?” Working paper, Duke University, 2008.

Stoll, Hans R., ”Friction.” Journal of Finance, 55 (2000), pp. 1479-1514.

Wurgler, Jeffrey and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya, ”Does Arbitrage Flatten Demand Curvesfor Stocks?” Journal of Business, 75 (2002), pp. 583-608.

18

Distribution of Valuation Measures by Year

BCD Mispricing V/P B/M

Year N Mean Std. Dev. N Mean Std. Dev. N Mean Std. Dev.

1980 1,001 14.85% 23.66% 1,562 104.43% 61.61% 3,333 112.59% 104.58%

1981 1,279 20.04% 26.15% 1,630 94.40% 53.93% 3,358 99.87% 91.72%

1982 1,508 8.15% 28.27% 1,598 109.25% 60.72% 3,366 111.99% 96.47%

1983 1,540 26.09% 31.19% 1,684 78.90% 42.49% 3,179 76.16% 89.08%

1984 1,731 8.50% 28.49% 2,244 86.00% 50.48% 3,429 83.74% 93.72%

1985 1,734 1.08% 24.63% 2,197 78.02% 46.29% 3,424 81.30% 105.89%

1986 1,812 -6.99% 22.30% 2,173 72.79% 46.15% 3,260 73.28% 111.62%

1987 2,068 4.16% 27.55% 2,375 79.01% 51.31% 3,444 73.22% 107.21%

1988 1,929 -6.47% 24.78% 2,347 87.52% 52.69% 3,451 84.79% 114.46%

1989 2,004 -0.41% 25.15% 2,419 74.85% 44.11% 3,437 82.32% 111.75%

1990 2,186 -6.94% 26.72% 2,453 88.42% 58.37% 3,399 100.44% 129.34%

1991 2,274 2.20% 27.69% 2,422 81.14% 59.43% 3,381 92.61% 128.81%

1992 2,360 1.87% 25.31% 2,679 79.02% 52.01% 3,497 80.58% 120.09%

1993 2,526 -2.91% 23.04% 2,958 80.07% 49.52% 3,716 71.71% 111.57%

1994 2,673 2.95% 25.05% 3,502 85.52% 53.42% 4,534 75.97% 112.46%

1995 2,924 -1.20% 25.00% 3,669 76.64% 48.85% 4,840 75.93% 115.92%

1996 3,113 3.51% 26.89% 3,928 72.37% 44.95% 4,958 72.17% 119.31%

1997 3,360 5.96% 27.39% 4,231 68.98% 46.54% 5,072 71.12% 128.74%

1998 3,456 -6.84% 28.71% 4,060 77.70% 67.53% 4,926 78.44% 141.01%

1999 3,570 -4.21% 33.49% 3,885 89.64% 71.77% 4,217 73.91% 79.44%

2000 3,435 -7.19% 36.43% 3,517 99.41% 82.11% 4,151 86.18% 108.52%

2001 3,176 -5.09% 33.45% 3,367 90.87% 79.67% 3,782 96.20% 125.99%

2002 2,978 -6.97% 33.43% 3,262 103.34% 84.27% 3,362 93.53% 118.68%

2003 3,152 -5.38% 32.12% 3,297 103.28% 84.27% 3,391 74.14% 82.24%

2004 3,341 2.02% 31.41% 3,439 85.63% 65.67% 3,620 52.67% 47.43%

2005 3,397 -1.94% 27.65% 3,571 82.08% 68.41% 3,819 52.10% 42.30%

2006 3,450 3.18% 26.79% 3,644 76.45% 66.09% 3,737 49.36% 41.14%

2007 3,415 3.69% 27.71% 3,574 69.99% 58.88% 3,614 52.46% 45.58%

All Years 71,392 1.63% 27.87% 81,687 84.85% 58.98% 105,697 79.60% 100.89%

EXHIBIT 1

EXHIBIT 2

Calendar-Month Distributions of BCD Mispricing, V/P and B/M Ratios

Month Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt. Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt. Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt.

Jul 2.97% 1.83% 25.41% 0.69 2.91 83.42% 71.95% 56.44% 4.48 39.92 88.77% 62.26% 123.43% 6.94 75.93

Aug 1.94% 1.01% 24.96% 0.65 2.78 84.86% 73.25% 57.60% 4.65 42.82 90.47% 62.93% 125.85% 6.78 72.12

Sep 1.22% 0.08% 24.84% 0.71 2.95 85.69% 73.99% 58.30% 4.57 40.72 90.84% 62.91% 126.71% 6.79 72.43

Oct 0.23% -0.71% 24.97% 0.63 2.53 87.96% 75.27% 61.57% 4.49 37.80 92.88% 63.73% 127.71% 6.45 65.86

Nov -0.35% -1.28% 24.89% 0.61 2.62 87.61% 74.93% 61.87% 4.75 41.93 93.75% 63.79% 131.02% 6.41 63.88

Dec -0.72% -1.60% 25.26% 0.63 2.84 80.40% 68.85% 57.98% 5.32 52.43 94.67% 65.01% 132.45% 6.43 63.09

Jan 1.27% 0.15% 25.15% 0.65 2.76 78.89% 68.22% 54.07% 4.91 48.37 90.32% 64.55% 123.57% 6.96 74.68

Feb 1.89% 0.67% 25.33% 0.64 2.70 80.98% 69.86% 55.16% 4.72 44.67 88.81% 63.60% 121.37% 7.04 76.90

Mar 1.34% 0.19% 25.19% 0.61 2.70 82.01% 70.73% 55.29% 4.49 40.10 88.72% 63.53% 121.51% 7.05 76.57

Apr 3.02% 1.98% 25.64% 0.57 2.39 82.66% 70.99% 56.86% 4.64 41.53 88.87% 63.13% 122.47% 7.21 80.73

May 4.02% 2.79% 25.77% 0.58 2.49 82.53% 71.07% 56.26% 4.55 40.35 87.91% 62.16% 121.98% 7.19 79.87

Jun 3.50% 2.41% 26.25% 0.61 2.67 83.00% 71.01% 58.08% 4.77 43.68 88.28% 61.70% 126.02% 7.33 80.95

Diff. Diff. Diff.

Jun v. Dec 4.2% 2.6% -6.4%

Jan v. Dec 2.0% -1.5% -4.3%

Difference in means is calculated only for stocks present during both relevant months. S.E. denotes standard error, and p reports the p-value for the hypothesis that the valuation level is

the same between the two calendar months.

p

0.000

0.000 0.42%

0.43%

S.E.

B/M RatioV/P RatioBCD Mispricing

0.16%

0.22%

p

0.000

0.000

Test of Differences in Valuation Measure Between Calendar Months

S.E.

0.12%

0.06%

p

0.000

0.000

S.E.

Fair Valued group contains observations with BCD mispricing greater than -10% and less than or equal to 10%.

EXHIBIT 3

Seasonal Distribution of All Firms Based on BCD Mispricing

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

30.0%

35.0%

40.0%

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

30.0%

35.0%

40.0%

EXHIBIT 4

Seasonal Distributions of BCD Mispricing, V/P and B/M Ratios by Size

Month Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt. Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt. Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt.

Jul 0.17% -0.97% 29.14% 0.70 1.96 107.95% 89.15% 82.08% 4.07 25.52 99.63% 74.77% 110.20% 4.86 40.84

Aug -0.65% -2.08% 28.54% 0.66 1.85 110.96% 91.43% 83.03% 4.13 26.67 102.24% 75.64% 115.32% 4.73 38.78

Sep -0.91% -2.50% 28.48% 0.72 2.12 111.80% 92.22% 81.93% 3.86 23.61 102.65% 75.74% 116.85% 4.85 39.96

Oct -1.73% -3.25% 28.51% 0.69 1.89 117.30% 96.44% 86.35% 3.67 20.31 103.76% 76.03% 119.45% 4.90 41.17

Nov -2.61% -3.96% 28.30% 0.68 1.92 112.08% 92.89% 82.91% 3.90 24.17 106.69% 77.02% 126.74% 4.86 39.98

Dec -3.24% -4.46% 29.04% 0.75 2.24 103.01% 84.74% 80.73% 4.44 32.28 109.95% 79.63% 127.41% 4.78 37.16

Jan -0.12% -1.81% 28.91% 0.73 2.10 99.98% 83.82% 73.00% 3.78 23.58 101.14% 75.48% 113.86% 4.92 42.01

Feb 0.99% -0.63% 28.88% 0.66 1.86 103.58% 86.18% 75.27% 3.87 25.71 99.46% 74.81% 108.72% 4.55 35.63

Mar 0.96% -0.49% 29.08% 0.67 1.91 106.51% 88.61% 75.41% 3.72 24.06 99.03% 73.21% 114.13% 4.90 40.27

Apr 2.25% 0.56% 29.62% 0.58 1.51 107.95% 89.81% 77.30% 3.69 23.21 98.10% 72.16% 115.63% 5.26 48.50

May 3.58% 2.01% 30.07% 0.57 1.39 106.45% 88.07% 75.14% 3.47 20.22 96.84% 70.28% 113.00% 4.99 42.60

Jun 3.54% 1.56% 30.53% 0.65 1.72 106.16% 87.64% 78.80% 3.83 23.29 95.78% 69.54% 112.66% 5.45 50.98

All 0.19% -1.33% 29.09% 0.67 1.87 107.81% 89.25% 79.33% 3.87 24.39 101.27% 74.53% 116.16% 4.92 41.49

Diff. Diff. Diff.

Jun v. Dec 6.8% 3.1% -14.2%

Jan v. Dec 3.1% -3.0% -8.8%

Panel A of EXHIBIT 4: Small Cap

BCD Mispricing V/P Ratio B/M Ratio

Test of Differences in Valuation Measure Between Calendar Months

0.19% 0.000 0.79% 0.000 0.69% 0.000

0.35% 0.000 1.03% 0.000 0.79% 0.000

pS.E. p S.E. p S.E.

Month Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt. Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt. Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt.

Jul 4.39% 2.80% 24.43% 0.76 2.79 83.72% 73.04% 56.33% 4.27 34.40 81.03% 60.56% 103.69% 7.23 84.03

Aug 3.10% 1.72% 24.05% 0.78 3.14 86.97% 75.37% 60.71% 4.89 44.68 83.39% 61.17% 109.17% 7.00 78.76

Sep 2.38% 1.02% 23.94% 0.86 3.62 89.57% 77.06% 61.88% 4.44 36.77 84.68% 61.31% 114.87% 7.49 88.02

Oct 1.02% -0.15% 23.83% 0.65 2.47 93.77% 79.55% 66.82% 4.65 40.31 86.84% 62.57% 113.44% 6.88 75.86

Nov 0.53% -0.70% 23.57% 0.67 2.78 89.88% 76.19% 68.04% 5.37 50.46 87.14% 62.07% 119.10% 7.23 81.35

Dec 0.27% -0.86% 23.83% 0.66 2.74 81.74% 69.28% 63.17% 5.73 61.31 89.28% 64.57% 117.62% 6.92 74.86

Jan 2.26% 0.72% 24.03% 0.71 2.70 80.09% 69.26% 55.78% 5.06 54.80 85.66% 64.56% 110.69% 7.45 86.68

Feb 2.54% 0.96% 24.18% 0.77 3.02 85.47% 73.68% 59.35% 4.99 51.57 83.62% 62.83% 107.62% 7.49 86.53

Mar 1.74% 0.35% 23.90% 0.63 2.55 87.78% 75.70% 59.40% 4.41 37.56 83.93% 63.49% 104.65% 7.12 82.03

Apr 3.52% 2.41% 24.29% 0.62 2.47 87.43% 74.96% 60.20% 4.55 40.51 83.99% 62.95% 105.44% 7.15 82.35

May 4.37% 3.13% 23.98% 0.64 2.69 86.15% 74.18% 59.53% 4.46 37.80 83.45% 61.84% 107.72% 7.32 83.75

Jun 3.36% 2.15% 24.20% 0.65 2.76 86.36% 74.70% 59.03% 4.13 31.44 83.75% 61.46% 111.49% 7.45 83.60

All 2.46% 1.13% 24.02% 0.70 2.81 86.58% 74.41% 60.85% 4.75 43.47 84.73% 62.45% 110.46% 7.23 82.32

Diff. Diff. Diff.

Jun v. Dec 3.1% 4.6% -5.5%

Jan v. Dec 2.0% -1.7% -3.6% 0.000

0.23% 0.000 0.66% 0.000 0.69% 0.000

0.12% 0.000 0.51% 0.001 0.68%

S.E. p S.E. p S.E. p

Panel B of EXHIBIT 4: Mid Cap

BCD Mispricing V/P Ratio B/M Ratio

Test of Differences in Valuation Measure Between Calendar Months

Month Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt. Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt. Mean Med Std. D. Skew. Kurt.

Jul 4.50% 2.94% 20.03% 0.80 3.49 77.34% 67.80% 51.20% 4.55 39.76 76.74% 57.81% 103.79% 7.65 91.01

Aug 3.40% 1.96% 19.29% 0.70 3.06 79.15% 69.13% 53.37% 5.13 49.86 77.62% 57.66% 106.37% 7.70 91.61

Sep 2.21% 0.88% 19.52% 0.79 3.39 81.17% 71.01% 55.19% 5.47 59.33 76.92% 56.99% 107.11% 7.80 93.56

Oct 1.69% 0.31% 20.01% 0.75 3.31 83.45% 72.50% 57.60% 4.89 44.73 78.41% 57.55% 106.34% 7.46 85.34

Nov 1.51% 0.14% 19.51% 0.63 2.76 80.20% 69.66% 54.24% 4.65 42.98 78.39% 57.86% 108.66% 7.69 90.41

Dec 1.22% -0.25% 19.67% 0.65 3.27 76.01% 63.32% 66.70% 6.54 62.10 78.16% 58.22% 106.83% 7.49 85.43

Jan 2.18% 0.90% 19.24% 0.66 3.19 73.84% 64.19% 54.43% 6.15 68.26 78.32% 59.99% 104.05% 7.52 87.97

Feb 2.42% 1.02% 19.52% 0.59 2.87 78.68% 68.44% 53.26% 5.12 50.39 76.50% 58.49% 100.82% 7.66 93.32

Mar 1.66% 0.43% 19.71% 0.62 3.35 79.33% 69.46% 52.47% 4.85 45.65 76.14% 58.09% 100.65% 7.70 93.43

Apr 3.15% 2.16% 19.76% 0.55 3.07 79.65% 69.21% 57.28% 5.67 56.37 77.16% 58.00% 105.95% 8.21 101.89

May 4.25% 2.88% 19.63% 0.74 3.74 79.46% 68.58% 57.68% 5.70 56.66 75.66% 57.36% 102.48% 8.15 102.18

Jun 3.55% 2.70% 19.82% 0.61 3.23 80.42% 69.14% 60.88% 6.33 69.84 75.06% 57.26% 103.33% 8.04 98.59

All 2.65% 1.34% 19.64% 0.68 3.23 79.06% 68.54% 56.19% 5.42 53.83 77.09% 57.94% 104.70% 7.76 92.90

Diff. Diff. Diff.

Jun v. Dec 2.3% 4.4% -3.1%

Jan v. Dec 1.0% -2.2% 0.2%

Small-, Mid-, and Large-cap groups are determined based on the market cap of each firm in June of year t and remain fixed for July-December of year t and for January to June of

year t+1. Difference in means is calculated only for stocks present during both relevant months. S.E. denotes standard error, and p reports the p-value for the hypothesis that the

valuation level is the same between the two calendar months.

0.11% 0.000 0.67% 0.001 0.75% 0.790

p

0.22% 0.000 0.80% 0.000 0.76% 0.000

S.E. p S.E. p S.E.

Panel C of EXHIBIT 4: Large Cap

BCD Mispricing V/P Ratio B/M Ratio

Test of Differences in Valuation Measure Between Calendar Months

EXHIBIT 5

Regression of Stock Returns on Valuation Measures

No. Specification Intercept BCD Mispr. V/P B/M Ln(Size) Adj- R2

No. Obs.

1 All Months 2.171 -0.013 0.448 -0.075 -0.101 0.028 324

Whole Sample (3.22) (5.02) (3.68) (2.61) (2.60)

2 December 9.956 -0.043 0.330 0.069 -0.561 0.046 27

Whole Sample (5.35) (4.28) (0.72) (0.67) (6.64)

3 All Months 1.977 -0.012 0.637 -0.115 -0.082 0.016 324

Small Cap (1.78) (4.46) (4.18) (1.72) (0.95)

4 December 15.512 -0.048 -0.164 0.194 -0.988 0.035 27

Small Cap (4.41) (5.01) (0.31) (1.02) (3.37)

5 All Months 1.634 -0.016 0.432 -0.120 -0.059 0.026 324

Mid Cap (1.33) (5.09) (2.53) (2.00) (0.70)

6 December 8.504 -0.052 0.381 0.135 -0.499 0.048 27

Mid Cap (2.28) (4.29) (0.49) (0.41) (2.02)

7 All Months 1.314 -0.013 0.323 -0.193 -0.038 0.046 324

Large Cap (1.54) (3.07) (1.65) (1.76) (0.79)

8 December 8.394 -0.035 -0.372 0.744 -0.450 0.059 27

Large Cap (3.24) (2.23) (0.44) (1.49) (3.41)

The dependent variable is the future 1-month holding return. For each given month during the sample period, a cross-

sectional regression of future returns is run on BCD mispricing, V/P and B/M ratios, and natural log of company's

market capitalization. The table reports the time-series average of coefficient estimates from cross-sectional regressions

with a corresponding t-statistic (given in parentheses). Adj-R2

is the time-series average of the Adjusted R2

for the cross-

sectional regressions. The number of observations reported in the last column is the total number of monthly cross-

sectional regressions.