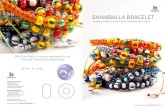

A Bracelet to Die For

-

Upload

amanda-hill -

Category

Documents

-

view

111 -

download

0

Transcript of A Bracelet to Die For

1

A Bracelet to Die For: The Beaker Vambrace and Community Defence

Against the Threat of the Copper Dagger.

Graham E Hill

Introduction.

For several years this writer has been conducting systematic field walks and focussed

searches of „hot-spots‟ on the available ploughed land surface close to a spring and

stream in West Penwith, Cornwall. This has yielded a dense and complex GPS map of

Mesolithic to Bronze Age flint-work, ground greenstone axes and groups of pottery

including Earlier Neolithic Hembury Ware, possible Middle Neolithic Impressed Ware

and Later Neolithic Grooved Ware and Beaker pottery(Portable Antiquities

Scheme.2007-10). In 2008 it was not a complete surprise to see on a stone-ridge,

deposited during potato harvesting a more than half complete slate „archer‟s‟ wrist-

guard.(Hill.unpublished cat., 547.2) and CORN-B38773(P.A.S.)

Image:„Wrist-guard‟ 547.2 , length incomplete, 59mm

The find in this writer‟s opinion was then only a formality to identify by specialists

available to The Portable Antiquities Scheme. Before handing it in it was shown to the

writer‟s father-in-law; Rodney Blunsdon who has experience in archery including

modern composite and traditional longbows. His reaction was unexpected. He dismissed

the archer‟s wrist-guard description, saying that it was impractical and possibly

hazardous to use and that he would use a leather wrist-band.

In the July/August 2010 edition of British Archaeology an article by Matt Mossop

outlined this writer‟s field-walking and finds recording methods and included this

drawing.

An email response from Scott Chandler, a collector of American Paleo-Indian artefacts

followed in which he too questioned the archer‟s wrist-guard description accompanying

the illustration. Giving them the term; gorgets, he wrote that similar objects found in

North America were „tied around the neck as a necklace by the leaders or chiefs of the

clan to delineate power, as archaeologists over here believe..‟ This writer in the

exchange of emails that followed began the learning process that expanded into this

essay. In popular archaeology books at home the drawing of The Driffield

Burial(Burgess,1980) and the photograph of the grave of The Amesbury

Archer(Pearson, 1993),( the only examples found until H. Fokkens‟ bountiful paper)

show wrist-guards on the outside of the wrist and hence not in a position to protect from

the bow-string. Popular in this writer‟s collection ; Beakers..,D.L.Clarke showed a

striking association between wrist-guards and metal daggers, a new and possibly

destabilising addition to Later Neolithic life with what might be combat or sparring

scratches emphasised in the drawings of the Brandon and Sittingbourne wrist-guards.

2

Harry Fokkens‟ paper dealt systematically with the position of the wrist-guard and

confirmed doubts about the bow-string protection assertion. Anna Tyacke, Finds

Liaison Officer for Cornwall Portable Antiquities Scheme is in communication with this

writer concerning wrist-guard 547.2 and Ann Woodward and Fiona Roe et al., whose

paper „Beaker Age Bracers in Britain‟ is in Antiquity 2006. The points raised by this

paper and those of „Bracers or Bracelets‟; (Fokkens, 2008) appeared possible to be

addressed using a new idea, supported by internet resources, practical and thought

experiments. However before discussing their work; here is a remarkable letter to The

Telegraph newspaper, found late in the research for this essay. (13 Dec. 2010, Google

„wrist-guard theories‟).

„Letters

Slate wrist guard theory

David Band, Surbiton, Surrey 12:01 AM BST 27 Aug 2002

Sir- The Slate wristguards described as being found with the remains of the Bronze Age

“prince of Stonehenge” (report, Aug 21) may not have been all they seem.

Stone is not a material of choice for the forearm guards that archers refer to as bracers:

a few shots, and the precious bowstring would be cut through.

Furthermore, some of the stone bracers of this period have protruding studs at the

corners, which would catch the bowstring and inflict a painful injury on the archer.

As an archer, I suggest that, while the stone clearly was part of a bracer, it was worn on

the outside of the forearm and acted as a closure for a leather bracer worn in the

customary fashion on the inside of the forearm.

Modern archers sometimes clip useful (pencils, score pads) to the outer fastenings of

their bracers. The slate of the Stonehenge bracer would have been ideally placed for

touching up bronze arrowheads- even if these prestige items were complex to

manufacture, needed sharpening and were less deadly than the flint arrowheads used

by all and sundry.‟

This writer disagrees about the function of the stone bracer. Atkinson(1987) suggests

that flint barbed and tanged arrowheads were „imitating metal originals‟ but physical

evidence is so far lacking, at least in the popular literature. It would seem to be illogical

for copper examples to be in use to lose or embed in an enemy until the material was

„cheap‟ and plentiful for the purpose. Indeed flint barbed and tanged arrowheads were

some of the last formal flint tools to be used, well into the Middle Bronze Age; up to

1000 Cal BC.(Bond 2004).

The achievement of this letter is in its‟ priority in dismissing the bowstring protection

assertion, with attention drawn to the danger from the riveted bracers in this role and

in putting the bracer in a position on the outside of the wrist. Where Mr Band goes

beyond the conclusions of Woodward and Fokkens is in assuming a practical function

for the stone wrist guard. That idea will be developed after looking at the contributions

of Woodward and Fokkens and their research teams.

A Review of A.Woodward‟s paper of 2006 and H. Fokkens‟ paper of 2008;

emphasising points that this essay wishes to answer.

1.Beaker age bracers in England: sources, function and use, by Ann Woodward et al.

Ann Woodward notes that the archer‟s wrist-guard interpretation has a historical

development and that other interpretations have been considered. The association of

wrist-guards or bracers with barbed and tanged arrow-heads is not the only significant

3

one. The most common association is with Beaker pots, but after that some authors

claim that the next most likely association is with a dagger or copper knife. This writer

thinks that the distinction between dagger and knife is not supportable and will explain

under a later heading. The position of bracer in the grave when it was apparently worn

is noted as on the lower arm. Recent radiocarbon dates have supplemented the theories

about Beaker pottery style development with contemporary bracer styles going from A

to B to C(Atkinson) with various complications and disappearing before the latest

Beakers. The diversity of bracer size and styles is discussed with a fine corpus of bracer

photographs including the Hemp Knoll example covered in what appear to be use

scratches and the Amesbury examples of strikingly coloured stone. Lack of decoration

apart from incised margins of some Eastern European bracers is tabulated. Colour

variations of British bracers are different to those in Europe. This writer wonders

whether that might be due to a different range of rock types available? British bracers

are often of dark and dull colours but red and green tinges are noticed by Woodward.

Fragmentation is discussed with various degrees of damage before deposit with rather a

high degree of damage and loss commented upon. This writer will expand upon this

observation. Woodward‟s table of properties of the 26 bracers studied is useful here and

strongly supports the photographs, showing the degree of loss, mass and dimensions

amongst other properties. Corner damage was common and perhaps to be expected but

some examples seem to have been broken cleanly through the middle and some were

reworked to make a new smaller bracer. Again these observations will be explained in

this paper.

The finish and patterns of striations tabulated and discussed by Woodward may be

explained in this essay by manufacturing experiments producing bracers, perhaps

making it easier to distinguish use wear and damage from that left by working

available material from rough-out to polished article with the goal of identifying the

after manufacture wear and explaining its‟ cause. For instance, holes drilled in

archaeological examples will be shown to be similar to those using this writer‟s simple

drilling technique and attachment techniques with rivets and thongs discussed by

Woodward, will be put into practice. The utility of riveting, with or without gold-

capped mounts will be justified.

Wear is considered and its‟ difficulty to notice on hard stones. The puzzling

phenomenon of cut-down bracers is again considered with the possibility of them being

heirlooms. This writer will suggest a more immediate reason for curation without

entirely disagreeing. Woodward suggests that the cutting down has rendered the bracer

impractical for archery practise. Later in the paper Woodward suggests that the stone

bracer was only ever representing archery and this writer would therefore infer it to be

impractical at any size. This writer asserts that the bracer was never associated with

archery practically or symbolically and even cut down it had practical merit for a

different use with enormous psychological augmentation to the wearer of a cut down

example due to the story of how it got broken! Breakage across one corner hole was

questioned and the possibility of manufacturing breakage discounted. This writer

agrees, having reproduced it with a hard strike. Soft gold caps to rivets were said to

show signs of use wear so bracers embellished with them were more than just a grave

deposit. „Irregular denting‟ of the caps was indicative of use.

Woodward‟s paper analyses the 26 bracers petrographically using low power

microscopy and tested their chemical composition using sophisticated non-destructive

methods. Parallels were found between the rock groups used for Neolithic ground axes

and those used for bracers. Fine grained stones were preferred by the manufacturers as

4

were those capable of splitting into parallel layers. This proved true for experiments

detailed in this essay.

Geochemical analysis of the 26 bracers showed good agreement with the petrographic

analysis as to the origin of the pieces and coincided with Neolithic axe manufacturing

areas. Tables of data were included to support this conclusion.

In the discussion that followed, the weak association between bracers and other archery

equipment was commented upon. The high quality of workmanship and finish of the

bracers was admired. Little evidence was found of wear. Degree of wear and other

striations were tabulated. This writer is trying to discern a distinction between

striations occurring during use and those from material flaws and manufacturing

processes. From existing photographs and drawings; Sittingbourne, Brandon and Hemp

Knoll might be worth further consideration. The standing rivets on some Bracers in

Woodward‟s opinion were an argument against the bracer being used in archery and a

Tudor treatise prohibiting the use of rivets is cited. Gold cappings of some rivets were

said to suggest wear in use whereas the bracer itself was pristine. The arched bracer

was suggested to be non-functional (in archery) and bracers were seen as symbolic.

Associations were found between axe manufacturing sites and bracers, both

petrographic and geochemical analysis being in agreement with that. Manufacture from

axe-heads themselves was dismissed. This writer agrees and will show why from his

experiments. Woodward considered that a functional archery bracer was no-longer a

viable interpretation but did not entirely depart from a symbolic association with

archery. This writer is grateful to Woodward and colleagues for this paper, highlighting

the corpus of photographs, supported by the tables of data and observations which

answer questions and pose new ones.

2.Bracers or Bracelets? About the Functionality and Meaning of Bell Beaker Wrist-

guards, by Harry Fokkens et al: a review again biased towards bringing out points to

answer in this essay.

Harry Fokkens begins by examining the tradition by archaeologists of attributing the

bracer as a bow-string wrist-guard. The practicality of the stone bracer is questioned

and Fokkens points out that the stone examples seem to be a cultural feature of only one

society. He sets out a programme to study the wrist-guards and embeds this within The

Leiden Project study of Beaker cultures in Europe. He chooses to focus his attention on

the position of the wrist-guard on the body and to look for ethnographic parallels and

further clues from the art of archery.

In discussing form and typology Fokkens notes the different terms for the object and

the different classification systems, based upon plan, section and number of holes. He

chooses Jonathan Smith‟s of 2006. Woodward chose that of Atkinson (Clarke 1970).

This writer will use Atkinson and propose a new classification! Fokkens tabulates 400

bracers from Britain, Continental Europe and Ireland showing considerable variation

of style in different localities.

The position of the wrist-guard on the arm is dealt with next and in this writer‟s opinion

completes the work of Woodward in removing the bow-string wrist-guard assertion

from future literature as effectively as Woodward concords the bracers to rocks, areas

and axes. 31 grave drawings containing wrist-guards, apparently worn on the arm were

discovered. The wrist-guard positions were grouped into 7 categories with

accompanying bone/bracer diagrams. These were totalled and a bar chart created with

an indication as to whether these grave positions were likely from an inside or outside

wrist position pre-decomposition. He reasonably draws the conclusion that some bracer

5

in grave positions are difficult to interpret but that in the worst case 60% indicate that

the bracer was worn on the outside of the wrist. He takes the outside position on the

wrist to be non-functional and in the context of a bow-string wrist-guard it is hard to

disagree. He discusses functional and non-functional and perhaps ornamental positions

and that while the outside of the wrist position was in the majority, the inside wrist

position also occurred. Much of the paper is made up of descriptions and excavation

drawings of Beaker graves and indeed they continue after the references making a

fascinating resource in themselves.

The outside position of the Amesbury Archer‟s wrist-guard is noted by Fokkens as is

that of the Driffield burial, however he tempers this with the observation that this

drawing is a 19th

century artist‟s impression and perhaps not very trustworthy.

Fokkens develops his theme of the ornamental bracer by describing their impractical

design (for a bow-string guard), in their variation in size from 200mm to less than

50mm in length and the gold adorned and riveted examples. Fokkens agrees with

Woodward that protruding rivets would damage the bow-string.

Attachment of the bracer is considered and it is thought to be often by thongs with a few

exceptions obviously riveted, probably onto a wrist-band. Some 2 hole bracers may also

have been on a wristlet due to difficulty of attaching by thongs alone. These comments

are in agreement with this writer‟s bracer attachment and wearing experiments. Finally

there is a drawing of an archer firing an arrow with the wristlet protecting his inner

arm from the bow-string and the 2-hole bracer riveted to the outside. The

accompanying caption emphasises the ornamental role of the bracer but reads,

„probably with a symbolic value with respect to the warrior/archer‟s personal status.‟

The second major section of the paper titled „The Ethnographic Record‟ describes the

use of bow-string wrist-guards in history and with associated literature, noting the gap

to prehistory when the unique stone examples are to be found.

American Indian organic examples are discussed and the ornamental silver ketohs worn

on the outside arm position of Hopi leather wrist-guards photographed. The position of

the archer in society is expanded upon and what being an archer might mean as a way

of life. Ishi; the last undiscovered American Indian, his life and death are gleaned for

clues(Kroeber,1961). This writer did the same when discovering the book of his story.

Fokkens detects that in the prehistory of World cultures there is a shift from hunter to

warrior but that some of the ideas and outlook persisted, perhaps retaining stone

artefacts embodying these beliefs. Fokkens seems to be forming the view towards his

concluding remarks that the wrist-guard has a martial meaning and that the qualities of

high craftsmanship and working difficult and not locally available stone „suggest such

values as bravery, righteousness, stability, tranquillity of mind‟. This writer feels that

Woodward and Fokkens are moving toward a martial meaning with the bracer

carrying these virtues. If the following essay can remove the confusing archery

„baggage‟ then the function and meaning of the bracer may become clear.

Fokkens again claims the wrist-guard to be ornamental, if symbolic when on the outside

of the arm. In „Chiefs or Ideal Ancestors‟ Fokkens notes the oft combination of wrist-

guards and daggers in Beaker burials and in „concluding remarks‟ he states „We have

resisted the temptation to discuss the quite frequent association of wrist-guards with

copper daggers..‟ Harry cautions further research before this is done. This writer will

risk seizing that opportunity!

6

16th

Dec. 2010; another paper was discovered and only for reason of late inclusion will

be commented upon only briefly in this section. To this writer it makes a fascinating

comparison to those discussed and anticipates the practical manufacturing and wearing

experiments of stone bracers carried out by this fellow experimenter:

Early Bronze Age Stone Wrist-Guards in Britain: archer‟s bracer or Social

Symbol. By Jonathon Smith, Ba Hons, 2006. This paper notes an association

between daggers and wrist-guards and finds a common origin in the „Carpathian

Basin‟. Central graves of males with concentrations of metal goods; often daggers were

found with wrist-guards. Smith found that a stone wrist-guard might be feasible as a

bowstring guard in experiments but it slipped and a leather band felt safer. Smith

emphasised the status conferred upon the wearer of the wrist-guard and asked

questions about how this was expressed as a grave good. The immediacy of his extended

wear experiments seem to have enlivened his thoughts about the subject. This

experimenter feels fortunate to have not discovered this paper earlier as he might not

have troubled to make and wear wrist-guards with the similar and significantly

different conclusions reached. Smith‟s Carpathian dagger associations appear to be

richly born out with short internet research and might be the basis for a comparative

study of Eastern European versus Western European evidence. Email evidence

confirms a discourse between Smith(fugue 2006) and Woodward with Fokkens citing

them both.

Experiments in the Manufacture of Soft Slate and Metamorphosed Basalt

Bracers. 1.Soft Slate. On the land surface of Cornwall as with many other places in Britain there is a fair

chance of finding a re-deposited piece of former roofing slate, typically split to a

thickness of about 4mm. It is with this material that this writer made two 4-hole bracers

in the late summer of 2010. The bracers were of similar thickness to find 547.2 but of a

slightly different feel, suggesting a different source notwithstanding the mellowing effect

of 4000 years of exposure to soil conditions. Fashioning the slate into a suitable plan was

carefree with the edges chipped semi-abruptly with any edged stone available. Flaked

chert was to hand for this. When close to plan and before over-flaking the hammer-

stone/chisel was put down and spoilt for choice of local grinding materials, the final

form was ground on a soil corroded granite rubbing stone with water to unclog the

grindstone pores. A very simple technology was employed for drilling the holes.

Conserved flint and the coarser chert from previous experiments was chipped with

another stone( usually tough diorite) to produce denticles on flakes and stronger

triangular section awls on broken pebble chunks. Working from one side, conical holes

were produced, supporting the bracer in the palm of the other hand. The moment of

breakthrough was felt and turning the piece over, a little clearing of the hole from the

other side produced results apparently similar to ancient work.

Each hole took a few minutes to drill and altogether the slate bracer took no more

than an hour to make!

7

Image: page 132 from Experimental Archaeology: Primitive Stonework, showing

cardboard/wool bracer and card dagger experiment articles and slate bracers; 7 and 8

with attachment options.

8

Against this a properly symmetrical bracer would involve more time to make from

trueing up and a greater removal of material but a time of 2 hours would be more than

enough for a slate or similarly soft and flat bracer of 4 or less holes. The time and effort

to acquire the suitable piece of rock might be much greater than the investment in

manufacture.

The wearing of a 4-hole bracer similar to 547.2 was simulated with a corrugated

cardboard copy with a single permanently knotted loop of wool. This produced an

adjustable loop at each end making putting on and taking off the bracer easy.

This writer considers this to be a real solution for 4 hole bracers but not the only one.

The real weight slate bracers were considered worth using in extended wear

experiments. They were both riveted to versions of leather wristlets, split in order to go

over the bulky hand onto the wrist and then with various and not totally satisfactory

arrangements of leather thongs, the wristlet was closed around the fore-arm. The

psychological and social signalling implications will be explained under a later heading.

The cutting of the leather had interesting consequences. It was found that flint as short

broken edges and flakes was indifferent at cutting as although mostly sharp, any blunt

or crested areas caught in the leather, pulling it into fibres and impeding progress. Less

sharp but less uneven modern metal knives cut more cleanly. Extension of this

experiment into stabbing produced similar results with the leather holding back the

flint. These observations will be expanded upon in this essay.

Riveting was achieved with modern copper wire bent over into loop fastenings in the

manner of a split pin. The other bracer used hardware store copper tacks with the

sharp end squashed over until it pressed the slate. Hammering the rivet was abandoned

after missing the target and breaking off a corner through the hole. This may have been

a closer simulation of a hard knock in service rather than a likely riveting accident. No

other corners were broken when rivets were squashed in and indeed no holes have been

broken in drilling holes in bracers, axes and mace-heads by this writer. The advantages

and mishaps of pecking holes is another story beyond the scope of this essay.

2.Metamorphosed Basalt Another resource available was a selection of tough flakes derived from stone axe

manufacture. The method of producing fine axes in the style of European Jadeite celts

from very tough fine-grained diorite was to hammer elongated, possibly slightly

laminated(schistose) cobbles against outcrops of similar material. When successful, very

large primary flakes would detach. Sometimes a symmetrical bifurcation would occur

leaving complete platform edges for a pair of rough-outs to be developed by further

bloc-en-bloc technique against a softer, more gripping granite outcrop, with perhaps

some more conventional hammer-stone work to tidy them up. On the upper beach near

to the former Werrytown offshore mine some of these flakes were harvested. As well as

the wonderful set of stone resources on the beach, the writer is aware of the

undesirability of doing stonework that might contaminate a prehistoric site. Flint

master; Errett Callahan(Google) has laid out a code of conduct which includes a

prohibition of this. Cornish Stone master; Dave Weddle(2007) disposes of flint debitage

mixed with broken glass to landfill. This writer hopes that the active beach and

industrial history will tidy up after him.The major component of the beach material is

derived from basalt which has been altered by the heat from a nearby major magma

upwelling that became the granite of Dartmoor and other exposures throughout

Cornwall. Various rates of cooling produced small and microscopically grained rocks

from the adjacent re-melted basalts. The former when corroded slightly green can be

pecked and flaked freely and was favoured (continues on page 10.)

9

Image: bracer no.3

reverse, with conical

holes and accidental

drilling scratch

around upper left

hand hole.

Image: rough-out for no.6 after

several sessions of grind-

ing/chert pecking.

Image: Materials

used(from top left

clock-wise) on cor-

roded granite rub-

bing stone; beach

grit, flint hammer-

stone, chert chunk

and flakes, sand and

quartz crystal. Not

shown are a hard

stick and a similar

greenstone axe, used

to polish no.6 to try

to improve finish.

10

to make widely traded axes in the Neolithic and Bronze Age. The latter very fine

material is much tougher and makes a ringing note when struck. Like Jadeite(Weddle

2010) it resists pecking and this writer vividly remembers the first hammer-stone

removed flake in 2007 as it scythed passed his wrist. Older people call this material

„Elvan‟, but quartz-porphyry(Goode,1988) might be a more accurate term. Elvan

grades to greenstone and the rock-picker tests many pieces to find one worth the effort

of working up and tests it hard for flaws to avoid a disappointing failure later in

manufacture. Material judged too schistose to make an axe that is reliable in service

may save much work in grinding off thickness if split down for a bracer. Experience in

the finish of grinding slightly different stones when axe-making may be even more

valuable when the manufacture of a bracer of outstanding appearance is considered.

There is certainly a great advantage in shared material and experience in the co-

production of axes and bracers so Woodward‟s findings of rock concordance are

welcome. One of the flat bracers produced was indeed worked from a triangular axe

rough-out but it was so thin that it was rejected for that purpose and then conveniently

reworked to a rectangular form before grinding to a bracer. This exception in no way

refutes Woodward‟s conclusion that axes were not ground down to make bracers. It is

much easier and less costly in time to harvest waste flakes and other available material.

The use of primary flakes and other pieces with a long exposed surface may result in

deeply oxidised pockets and other alterations which may be visible in the highly finished

surface of some bracers as noticed by Woodward. Manufacturing of a hard-stone flake

beyond the hammer-stone trimming of a good flake or nicely split schistose piece is in

the case of the toughest „elvans‟ completed by grinding alone. Every slightly

unfortunate step fracture left from the rough-out is paid for by about an hour per

millimetre to remove. The otherwise favoured 1-2mm sized beach-sorted grit on a

granite rubbing stone has only a fraction of useful grits; mainly quartz with a little

chert. Much effort is expended in destroying the rest of the softer grit to a grey paste

without attacking the rough-out. It is a characteristic of grinding that once the uneven

rough-out is flattened then the grinding becomes more efficient. This writer believes

that this is because rough-out high spots concentrate force and crush the gravel. With

the corollary of the flat rough-out, the individual gravel pieces are evenly loaded and

kept sharp. Belief is essential to cut hard stones! Augmentation or replacement of the

gravel with crushed chert pebbles or curated flint and chert waste is very effective. On a

granite rubber some of it embeds producing tiny scores on the piece, demonstrating a

powerful action. Until summer 2010 this method of grinding was uncompetitive because

over 80% of the chert flew away on crushing and much of the remnant did the same

when grinding with the ubiquitous water. This problem has been entirely resolved by

wrapping the chert in one of the softer sea-weeds before crushing. The cutting paste

needs no further water and is sticky enough to stop larger chert fragments spitting out

early in the grind. With the end of bulk removal in sight then less scratching methods

improve the surface to the point where it can be polished. Various pieces of sandstone

will be collected by a stoneworker. Some are so well cemented, perhaps by silica

solutions or iron minerals that the individual quartz grains remain embedded and grind

flat so are only capable of further grinding when applying great pressure. Others are

weakly bound and are more of a handy source of sand to grind smooth on the granite

rubber. A rare but happy medium works every particle hard in the matrix before

releasing it into the paste and exposing a fresh sharp particle. The corroded micro-

granite rubbing stone, cleared of grit, completes the grind. Like the perfect sandstone

the weakened matrix softens the cut of embedded quartz and refreshes itself on hard

11

work. It takes the smoothness to a point where though matt in appearance a shine is

likely to develop within an hour of further work. In difficult concavities like under a

Driffield(C1) type bracer then final stages may be difficult to achieve and so tend to

leave the scratch-works of effective grinding; concurring with Woodward‟s

observations of striations on these bracers. The last operation before polishing is

drilling so that untidy edges and slips can be blended into the final scheme. On the mind

of this experimenter is the effort of drilling and this is mitigated by grinding thinner on

the hard stones and going for a 2 hole scheme rather than 4 or more if possible. There

may be a relationship to be explored between bracer thickness, rock hardness and

number of holes for someone to assess in the prehistoric examples.

The drilling method I employed was similar to that for the soft slate, for which in

principle many varieties of stone, flaked to awls could have been used. For the hard-

stone this was limited to just one or two. Quartz as elongated hexagonal crystals and in

more massive rocky pieces is available in the topsoil and outcrops in this area of

Cornwall. Its‟ hardness being greater than any common materials would make an ideal

drill but for the limited directions of this virtue. A modest twist under pressure and the

quartz shatters because of its‟ many weaknesses. Fine flint, a chemically related

material but for hydration and glassy structure, is nearly as hard, with a sharp cut, but

against the very toughest hard-stones again shatters like glass under all but light

torsional load. Never-the–less awls were quickly fashioned and almost as quickly

destroyed in service, leaving no evidence of their existence beyond flint waste. On one

Bracer an outer partial circumferential score was left by the awl where the „shoulder‟ of

the tool had accidentally contacted during a hard twist. This fits Woodward‟s

observation that she attributed to the width of the bow-drill on the Hemp Knoll

example. Dave Weddle is a champion of the use of chert in drilling and grinding; a view

which this experimenter has only slowly grown to accept. The definition of chert can be

disputed(Wikipedia,2010) but may be a broad term including other hydrated quartzes

including flint but specifically slightly coarser material that is not associated with the

chalk formations to be found east of Cornwall. Orangey Broom chert as complete

Palaeolithic hand axes is rarely found in Cornwall from its‟ prolific source in

Devon.(Exeter Museum,2008). However chert makes up a significant minority of stone-

age flake-work found in Cornwall with raised beaches containing flint and chert

pebbles within the county available to knowledgeable Mesolithic and Neolithic peoples,

as evidenced from their blade and flake tools as far West as Lands‟ End.(Hill,unpubl.).

In the Later Neolithic perhaps boat-loads of lightly rolled flint and mined flint appeared

from out of county, along with more Broom or similar chert.(Hill, unpubl.). Where

Broom is superior to flint is in its toughness, making longer lasting tools and in the case

of drilling holes in quartz-porphyry makes a job that is possible without prohibitive

retooling. This experimenter picked up a nice pebble in a car park just inside Devon

that worked to a stout triangular section point on a pebble grip in the palm; with re-

chipping, drilling 4 holes of 3-4mm deep in 2 hours.

Next flint and chert flakes and points were used to incise „Beaker Vambrace‟

propaganda diagrams and airliner motifs near to the drilled holes. This might have

relevance to incised examples from Eastern Europe but apart from publicity for this

project will label these objects as likely being from the present culture, even after this

document has disappeared. This satisfies another of Errett Callahan‟s protocols, to

mark work to prevent it from being confused with that of ancient workers.

12

Image: pair of hard-stone bracers; nos. 4 and 5, detailed in the following table.

Preparation for the polishing stage has been good without visible scratches or tiny pits.

A little oil, (that from the skin may be enough) is added to prevent adding scratches and

a smooth hard-stone pebble of similar material to the bracer used to polish it. A great

trick from Dave Weddle is to polish 2 axes of similar material against each other. This

was ideal for the pair of bracers from one group of axe debitage. Dust on an oiled piece

of leather or hard polishing with the end of a dry old stick or polishing against the facet

of a large quartz crystal or with a small, smooth, un-fractured cortex chert pebble.

These methods alone and in different combinations bring pieces to a finish in which

sometimes the face can be darkly discerned.

A Table of Modern Bracers after Woodward

A: Number

B: Owner

C: Type(Atkinson)

D: Number of holes

E: Colour

F: Rock type

G: Time to make/hours

H: Mohs hardness*

I: Length/mm

J: Maximum width/mm

K: Minimum width/mm

L: Maximum thickness/mm

M: Hole diameter/mm

N: Mass/g

O: Back striations

P: Front striations

Q: Decoration

R: Main reference: page(s) from .Hill.Experimental Archaeology:Primitive Stonework

(unpublished)

*Applies to single crystals and problematic on coarser grained rocks.>6 scratches glass.

Slate used here embeds copper whilst being scratched by it.(Mohs 3ish)

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R

1 H.Fo

kkens

A

2

2 black dior

ite

2

0

>6 1

1

4

5

3

3

3

8 7 - Fl

a

ke

sc

ar

Crac

ks,fi

ne

pits

Jets/dag

ger

fight

P

12

0-

12

0

13

s

fi

ne

D

A

2 R.Blu

nsdon

A

2

2 black dior

ite

1

5

-

2

0

>6 1

3

6

4

6

2

5

6 7 - Fi

ne

L

Som

e

fine

L

Jets

/dagger

fighter

P

12

1

3 A.Ty

acke

B

2

4 black dior

ite

2

0

>6 9

8

4

7

4

5

5 5 - S

o

m

e

fi

ne

L

a

n

d

T

Som

e

fine

pits

Jets/

grab

dagger

arm

P

12

2

4 G.Hil

l

A

1

2 black dior

ite

1

5

>6 9

1

4

1

4

0

4 6 2

6

S

o

m

e

fi

ne

T

nil Jets/

grab

dagger

arm

P

12

5

5 G.Hil

l

A

1

2 black dior

ite

1

5

>6 9

7

4

3

4

1

4 6 3

1

S

o

m

e

fi

ne

T

nil Jets

/grab

dagger

arm

P

12

5

6 G.Hil

l

C

1

2 Dk.gr

ey/dk.

grn

gree

nsto

ne

2

5

5-6 1

1

8

3

3

2

9

4 7 4

6

Fi

ne

L

Som

e

fine

D

Jets/

‟Beaker

Vambra

ce‟

P

13

0-

1

7 G.Hil

l

B

2

4+1ma

nu.bre

ak

Lt.gre

y.

slate 1 3 7

9

4

8

3

8

4 5 c.

3

0

ni

l

nil jet P

13

2

8 G.Hil

l

B

2

4 Lt.gre

y

slate 1 3 7

2

4

5

3

9

4 5 c.

3

0

ni

l

nil none P

13

2

Abbreviations:column D:manu;manufacturing,E:Lt;light,Dk;dark,grn;green,O and

P:T;transverse,L;longitudinal, D;diagonal

3.Complex Arched Bracer of Greenstone.

In order to accommodate the greater depth in form of this type the rough-out was not

developed from a flake but a large but flattish pebble. Early hammer-stone work tested

for obvious cracks and flaws and ability to peck off small spots of material as well as

14

larger but less controllable flakes. Passing these tests a not very sharp but tougher

quartz-porphyry hammer-stone waisted the top and sides and marked the underside

channel in an hour. Progress continued as with the harder stone bracers using beach

grit on granite rubber grinding but with cutting from a greater proportion of the grit.

With the greenstone peckable the grinding sessions were interspersed with sharp chert

hammer-stone percussion, then down-sizing to scrapers striking along the serrated edge

then finally individual chert flakes with chiselling strikes as the rough-out reduced in

thickness. When the flakes attacking the piece were judged little more powerful than

grinding and the danger of breaking the piece acute then grinding alone was used with

sandstone and chert pieces working the underside cavity and these plus grit and then

granite rubbing stone alone were used on the outside, leaving the outside smoother but

for some tangential scratches near the margin. Drilling was as for the quartz-porphyry

bracers but with the luxury of using the sharper flint as well as the tougher but blunter

orangey chert for awls. Finish was slightly disappointing with only a matt/shiny finish

despite quartz crystal and similar greenstone rubbing from the experimenter‟s axe

cache.

This image: bracers(left to right); 4,7on wristlet,

6, 8 on wristlet and 5.

Next image: bracer 6 with left section showing

sessions of removals by grinding and chert

pecking from the rough-out.

Description of Copper Daggers, Function and Significance

Knives found with Beaker vessels and less commonly with barbed and tanged arrow-

heads and/or bracers vary in size. D.L.Clarke‟s corpus shows a range in length from

just over 40mm to nearly 200mm. In their classification some authors have drawn a

distinction between knives and daggers, apparently based upon the small size of some.

However the Beaker blades of all sizes have important characteristics in common. They

are remarkably thin at 1-3mm thick, perhaps to make the most impressive object from

a small amount of precious metal, whether copper or copper alloy.

15

In form, unlike blunted-back flint blades of the Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic and

modern penknife blades, cutlery and butchery knives, the Beaker knives are

symmetrical in plan with both edges sharp, converging to a point. The metal blade edge

where one might put a guiding finger when using the knife as a tool would make it

unpleasant to use and its‟ very thinness liable to buckling in all but the lighter tasks. A

workaday tool in such a precious material also seems difficult to imagine. This writer

dismisses the term knife for Beaker blades if it is meant as a non-martial term. The

tracing of blades from pages 296-7 of Clarke‟s Beaker corpus versus some sharks‟ teeth

from this writer‟s collection is designed to suggest a similarity in mechanical action,

whereby the first point of contact is at the point where extreme force overcomes the

strength of flesh, then as it tears the sharp edges continue to rend the skin until the

whole tooth or dagger plunges through! On p.260 of Clarke‟s first volume: „a division

into large and small daggers seems over arbitrary since the smaller examples often show

whetting down from the larger size.‟

Should the reader continue to think that at 40mm long, a dagger, or knife wielded for

that purpose is too small then this writer will supply an anecdote from his experience:

There once was a friend that I and others respected as a big man.

Sometimes he operated outside the arc of protection that we assume over the social

contract of civilization.

Once he showed me a dagger, larger in plan than a great white shark‟s tooth but

smaller than that of megalodon(Macquitty,2002) with a pommel fitting into the palm of

the hand.

Maybe it was never deployed but it could plunge, twist, release and in that moment of

shock enable escape.

It was said in those times: “A gun for show: a knife for a pro.”(No ref. offered).

Image: typological comparison of Eocene fossil sharks‟ teeth from London Clay,

Sheppey, Kent.(B.M.1971) from this writer‟s collection and daggers from CLARKE,

D.L.1970. Beaker Pottery of Great Britain and Ireland Il., p.296-7. Reproduced with the

kind permission of Cambridge University Press.

Returning to the material from which these daggers were made. When first seen by

Later Neolithic people in Britain, metal must have shone with the sun‟s rays and

16

commanded awe. With its‟ malleability and ability to melt without degradation, copper

has the properties of a precious commodity with a value based upon its‟ weight and it

can be fashioned into a desirable object, enhancing its‟ intrinsic value with the potential

of being remodelled or combined with other currency stock to produce greater treasure.

This shiny and miraculous material must have made an impression which has been

reproduced almost to the point of indifference in the modern world. The first traded

copper, perhaps as free metal; which can still be found as a rare exhibit in geological

collections such as at the Royal Cornwall Museum (RCM) could have been beaten,

perhaps with softening from a hearth to bangles, pendants and other shiny, attractive

objects, stretching the small lumps into larger-appearing wearable, portable property.

It must have been within a blink of prehistoric time that devious and violent theft

became an alternative method of acquiring copper, whether by individuals or by a band

with shared intent, at least until the spoils were divided. The immediate and satisfying

solution to this problem was in this writer‟s opinion to make the copper into an object

that would protect itself and its‟ bearer. At once this valuable and unique material is

displayed to show the qualities of a flat sheet of shine, almost disappearing in profile; it

is far thinner than any practical stone dagger can be made. A discreet person can

conceal this upon the body or show a handle hafted on the waist-band; ready to be

lethal, but only if challenged. It was on the dagger hilt that was surely the safest place to

carry the even more precious metal; gold as embellishment of rivet covers or patterns of

tiny pins; a pommel decoration that developed to a high degree in the Early Bronze

Age.

Once created, the copper dagger not only solved the personnel and property protection

problem when carrying desirable commodities, but brought likely unintended

consequences that for many of us have resonance today. As effective as a deterrent for

defence, the dagger bearer had an advantage of surprise and lethality in pursuit of

portable treasure or other personal gain. For some the temptation to turn the dagger

into a tool of leverage for threatening others must have been overwhelming. There must

have followed an intensified period of raiding by dagger-bearing bands in search of

more copper and trophies and resorting to mayhem if their wants were not satisfied.

Owners of copper under this threat may have been able to martial people and resources

to fight back, but for the poor, marginalised and bearers of only stone, the threat of the

copper dagger may have been magnified in their imagination.

Life may have changed to a more unstable and fearful one for Later Neolithic

communities, but eventually a new balance was found and daggers of greater size and

frequency accommodated into socially acceptable frameworks of rules.

Before moving on it is worth considering whether a copper dagger is actually a more

lethal weapon than one made of flint.

A thin flint dagger, judging by contemporary examples and those of flint-masters of all

ages and cultures is thicker than the copper examples. Anything approaching it in

fineness; and this writer recommends looking at the Pre-dynastic Egyptian ripple-

flaked knives in The British Museum, would only take one drop onto a hard surface to

not only be chipped but broken to pieces. The copper dagger on dropping might suffer a

„ding‟ that might be beaten and polished out in a few minutes, giving the owner

confidence to wear the dagger at all times without care. As has been explained a flint

tool with flake scars in its‟ cutting edge is not as penetrating against skin and

particularly leather as it might appear. This definition would include Beaker flint

daggers(Tyacke, 1993) which would have had a less than lethal effect against the

accidental armour of a leather outer garment or the perhaps more intentionally

deployed archer‟s leather bowstring- guard wristband when parrying the attack or even

17

trying to catch the attacker‟s arm or dagger itself. The properties of flint let it down in

very sharp blades when highly loaded due to its‟ glass-like brittleness. Practical flint

axes have an included angle at the blade tip of at least 60 degrees. (This definition along

with more subjective criteria such as degree and extent of high finish might be used to

define non-utilitarian celts, as opposed to axes intended to chop wood!) Many ground

stone axes approach 90 degrees of included blade tip angle and to the modern eye look

unable to fell a tree, but actually require a shallower angled cut, producing a cut trunk

looking like two sharpened pencils pushed together. The wide blade angle is to

strengthen the brittle stone against impacts for which axes and necessarily dagger tips

are designed. (Webster,1980). Even so, stone blades tend to pressure flake, even against

softer materials like wood or bone in a mirror image of the intentional pressure flaking

using these materials as tools to lever off long flakes from acute angled flaking

platforms. Hence impact resistant stone tools have to be blunter than tougher if softer

metal ones. The intersecting flake ridges on a flaked dagger and any chips missing on a

ground stone tool are a place of holding up penetration through leather. A sharp tip

may pierce the layer but in stretching around this dimple the leather separates into a

netlike fabric of fibrils which snag and concentrate around blunt parts of the blade,

interrupting progress of the rend and perhaps giving the advantage back to the

defender. All this imagined from cutting leather on the backyard with a broken pebble!

Medieval and Modern Protection Against the Dagger with pointers to

Martial Arts in the Ancient World.

Stone and Copper daggers appeared in Britain in the Later Neolithic and since then

there has been a co-evolution with armour and less obviously in an archaeological sense;

defensive techniques. It is suggested here that „play-fighting‟ , whether it be wrestling,

boxing, mixed „all in‟ or stick fighting and perhaps all of them were carried out under

the rules of play in Later Neolithic times in Britain. Play-fighting for honour as well as

dominance are to be found in Gilgamesh(Poliakoff 1987), ancient Greek accounts and

The Legend of Robin Hood. A new story will be written under a later heading.

Accounts of martial arts and depictions on pot sherds, papyri and wall friezes from the

very beginning of history are brought together in „Combat Sports in the Ancient World‟

(Poliakoff 1987). Stick fighting is depicted in 12th

century B. C. E. Egypt with a forearm

shield lashed on with thongs. Mesopotamian boxers wore small wrist bands and

Classical Greeks wore bindings of thongs, around the wrist and sometimes additionally

around the knuckles. More relevant to this essay, Poliakoff translates an account of

disarming the dagger which will be repeated here:

„During a drinking party in the camp of Alexander the Great, a Macedonian named

Koragos challenged Dioxippos, victor at Olympia in pankration in 336 B.C.E., to a duel.

Alexander appointed a day for the fight and thousands of his soldiers came to watch.

The Macedonian appeared like Ares himself in full armor, Dioxippos came naked and

oiled, carrying only a club. Koragos first hurled a javelin, which Dioxippos dodged, then

attacked with a stabbing spear, only to have his opponent smash it with his club. Finally

Koragos reached for his dagger; Dioxippos, in the best Olympic form, grabbed

Koragos‟s right hand with his left, and with his other hand pushed him slightly off his

feet, then kicked his legs out from under him. Dioxippos completed his triumph by

putting his foot on his opponent‟s throat while raising his club and looking to the

crowd.‟

18

In historical times treatises have survived on defence against the dagger and fighting

techniques, notably those of Fiore dei Liberi and Achille Marozzo. In 1536 Marozzo

described how to grab the opponent‟s blade, which while likely to produce cuts would

have been preferable to being stabbed. Whether this is a viable method depends upon

the audacity of the defender and perhaps upon a strong but not necessarily very sharp

weapon designed to puncture the steel armour of the day. What is clear from studying

video and photos from defence against the dagger training is that an early part of the

defence is to grab the wrist area of the attacker‟s dagger

hand, before rapidly or simultaneously making a „special

move‟ of one‟s own. It is central to this writer‟s case that an

outer dagger-resistant wrist-guard gives significantly

greater confidence to „fish‟ for the attacker‟s dagger hand;

a point that will be returned to under a later heading.

Image:(Demonstrated on oneself). A grab too far from the

attacker‟s hand leaves the outer wrist open to pricking and

slashing from the dagger.

Before introducing the text from a „thread‟ from a modern

internet forum about the injury problems of modern dagger

sport fighting and their solution it is necessary to define a word, unfamiliar to this

writer before researching the work:

Vambrace (Wikipedia, 19/08/2010)

„Vambraces (French language avant-bras Polish language karwasz, sometimes known as

lower cannons in the Middle Ages are “tubular” or “gutter” defences for the forearm,

developed first in the ancient world by the Romans, but only formally named during the

early 14th

century, as part of a suit of plate armour. They were made of either leather,

sometimes reinforced with longitudinal strips of hardened hide or metal (a crafting

method named “splinted armour”), or from a single piece of worked steel and worn

with other pieces of armour. Vambraces are generally called forearm guards, with or

without separate couters. Vambraces formed the integral part of the Great Steppe,

Central Asian and Islamic warrior armour. The highest forms of vambraces, in terms of

art and utility, were developed in Italy and Germany during the Renaissance in Europe

and by the Persian and Turkish armorers during the corresponding time period in Asia.

Vambraces remained long in use after the high mark of Renaissance armour in Europe

, for example in Poland until 1770s, while on the fringes of Europe (the Caucasus) until

the second half of the 19th

century, while in Asia at least until the mid-19th

century

(Persia and Indian subcontinent). Archers often wear bracers, a variant of vambraces,

to protect their arms while shooting.‟

From swordforum.com

The Historical European Swordmanship forum.

„Wrist Protection for Dagger Work‟ On 03-02-2005, 08:19 AM Jessica Finley asks:

„Has anyone else run into this problem?

19

Last night we were working dagger plays, and were trying to work them with some

resistance and vigor. At one point, we were working at the trapping lock at the dagger.

Of course, I bear the marks of this fun evening at close range on the bones of my wrist.

Both of us wear long-cuffed gloves but this has proven to be not enough protection for

dagger work, even using wooden rondel wasters.

I pondered using steel gauntlets, but fear that would introduce too much difference into

the plays to make them feel and work right in unarmoured dagger play.

I am thinking of making thick leather bracers to protect the wrist and wrist bones, but

am not sure if this is really a viable option.

What solutions to this have the rest of you come up with?‟

03-02-2005, 08:48 AM Keith Jennings replies:

„The best wrist/forearm guard I have seen is the LAMECO arm guard:

http://inosanto.com/product_info.php...493e6cc7f4779b

I picked one up at a FMA seminar a few month back, and I love it. It is able to

withstand full cuts with even aluminium knife trainers. A bit expensive, but well worth

the money.‟

Other contributors mentioned padded sparring gloves but limited to use with wooden

daggers and there were problems of lack of realism with some combinations of

simulated dagger and over-protection.

03-02-2005, 10:23 AM fhunt adds:

„We‟ve used an archery wrist guard and it has worked well enough.‟

03-02-2005, 01:43 PM Pete Kautz suggests:

„I recommend a mix of a good wrist guard and a safer training weapon for those

applications.

There is no way around the fact that the scissors-hold especially – a staple of any

Medieval treatise – is designed to attack the bone structure of the body. Rob‟s

comments are spot on about a rolled up paper or magazine. This is what I have done for

years at my Bowie and Medieval seminars because it is easy, quick, and inexpensive yet

they are plenty stout and will hit as hard as you want, especially on a thrust!

(Edited to note: be sure to roll tightly from the spine of the paper or magazine and

cover in duct tape – especially the ends – otherwise these can give serious skin damage

on a thrust)

Remember as far as wrist guards go that there are training wrist guards and daily

street-wear wrist guards and they are not the same. A training wrist guard will overall

be stouter and more obvious than a street wrist guard. Ones for the street often are

slimmer and have strips of spring steel in them as well to protect against cuts

Best of all,

Pete Kautz

http://modernknives.com „

GaryG suggests heavy gauntlets and Christopher Blakey found soccer shin-pads to offer

maximum protection.

03-02-2005, 10:47 PM. Pete Kautz returns and explains methods and links to making

wrist guards. His closing paragraph reads:

„Overall, I advise people to always get a pair that is narrower than you think you need.

Many folks I know have gotten really long bracers and then not liked them as much as a

narrower pair. Also, they don‟t pass unseen on the street like a 3” bracer does…‟

The discussion continues with the relative merits of different dagger simulators

including rolled up newspapers and various degrees of padding debated with

contributions from James Roberts, Tony Wolf and V. Gable.

03-03-2005, 06:10 AM. Jessica Finley returns with:

20

Thank you all for your wonderful suggestions!

I think a combo of the magazines and some wrist bracers should solve our problem

nicely.

Jess

The thread continues with a little sparring over a statement from parisi carlo that

„females are more sensitive and fragile (but have better articulations, try wrist locks and

see)‟.Spirited responses from Jessica Finley and others demonstrated that women were

fully up for the fight!

03-04-2005, 09:30 AM Roger Siggs makes the final contribution to the thread and in the

following paragraph compares training to the real thing:

„For my part, the idea that both people have a knife, or that a defender is well aware of

the attack coming, and/or where the attack is coming from, implies a level of

predetermined consent for the action to occur. A knife „fight‟ does not fall under the

level of consent, and generally occurs with frightening swiftness and violence. It‟s not

the sort of optimistic action we see in a lot of the manuals, or even in most traditional

EMA work.‟

Functionality of a Stone Bracer in a Dagger Fight.

This writer is indebted to Harry Fokkens for his systematic study of the position of the

stone bracer on the arm in inhumations. Where it is ascertained it has been found on

the lower forearm at or slightly above the wrist, allowing full articulation of the hand.

The variability of position of the bracer as far as inside or outside the wrist is noted and

will be explained under the next heading, but for the purpose of the dagger fight only

the outside position will be considered as the functional one; in contradiction of

previous papers.

Practical defence against dagger attack has to take into account the unexpected timing

of the attack. A system of purely defensive armour to be worn nearly all the time would

have been cumbersome and enervating as a comprehensive Nuclear/Chemical/Biological

(NBC) suit is to a modern warrior. Much of the protection against a dagger is vigilance,

preferably shared in „watches‟ and in a spirit of mutual protection between members of

a community combined with a technique for attacking the dagger wielder so that the

dagger arm is caught and a special move applied by the free hand. This experimenter

has attempted to defend against a little play from cardboard and blunt cutlery

simulators but defers to experience of the Practitioners at swordforum who spoke under

the previous heading. The only comment to make is that a lot of their work is evenly

matched with a dagger each so that there is an element of dagger interlocking in their

play with other wrist injury possibilities not explored by this experimenter. What

appears common to both scenarios is damage over the wrist bones. When grabbing the

opponent‟s forearm to prevent a stabbing attack a less than ideal hold will leave enough

articulation in the dagger wielder‟s wrist to continue to prick at the outer forearm over

a limited area over the wrist bones and lower forearm. A leather wristlet in this

position, perhaps for the purposes of protecting against an archer‟s recoiling bowstring

might be adequate to prevent the hold being broken if repeatedly pricked by a stone

dagger, but a sharper copper knife would make the hold unsustainable due to a

disabling puncture. A stone bracer of rather small size would therefore be of use to a

vigilant defender. The protection against wrist damage afforded with the addition of

dulling the blade or turning over the tip of the dagger, rendering it less effective would

be a useful insurance should the defender‟s special move fail.

21

Leading up to this moment the defender will have practised in more and more realistic

training. Perhaps if able to train against copper with a hard-stone bracer it will proudly

display the streaks. More likely a softer bracer will carry the scratches and jabs from a

flint knife. (Flint; due to its‟ chips and flake scars may produce grouped parallel

scratches). Comfortable bracers; perhaps damaged may be retained, perhaps with re-

drilling when vulnerable corners have been damaged across a hole. As we have seen

with modern practitioners it is a tendency to begin training with what turns out to be an

unnecessarily large bracer(Kautz, 2005 ibid). It may be broken and carved down

without loss of function when worn by the now more experienced martial artist.

This writer is discerning a dichotomy in the class of objects called stone bracers;

based upon perceived mode of wear and function implied. The classification will be

quantified later. For the narrative, the distinction is based upon whether the bracer is to

be hidden under the clothing or displayed outside. This simple difference has great

consequences for the individual and their community and its‟ perception of them and

again will be discussed later.

The bracer implied up to now in this section is of the hidden type, at once not drawing

attention to the possible capabilities or intentions of the individual. It may be small,

lacking in bulk and light enough to be worn discretely for most of the time by anyone.

The second type is a larger and bulkier bracer. The complex arched (C1) type would be

an outstanding example. This would be difficult to hide under the clothing and it

appears that this is not the intention. It might prove inconvenient and uncomfortable to

wear for much of the time. Its‟ wearing might represent a different fighting style,

perhaps formalised combat at a chosen time, more evenly matched, with larger daggers

if the more recent dates for C1 bracers are agreed. A stronger and larger stone bracer

would give the option of using the bracer as a small shield to strike out at the dagger

and defeat it in one motion, in the style of the Medieval Buckler shield.(Wikipedia)

To digress, it seems likely that bracers were not the only experiment in protection

against daggers beginning in the Beaker period. Whilst making the complex arched

bracer(no.6), this experimenter could not help thinking of a split shinbone skeuomorph.

Bone armour is of likely utility but would be a rare survival. The only examples

suggested here are the bone spatulas of D.L.Clarke‟s Beaker corpus. They can appear

singly, in pairs and threes and the reader is invited to imagine wearing them along their

arm and leg bones in the manner of splinted armour. One of the 3 in the group in

fig.776 is suggestively decorated with diagonal slashes. The 2 pairs of improbably fine

and elongated „whet stones‟ on page 389 may be just that but they appear similar to the

bone spatulas in form and association; if not function? A development of the dagger;

increasing its‟ reach without making it more costly in precious copper was to mount it

as a spear or at 90 degrees as a halberd, perhaps as a direct response to self-defence

techniques against the dagger.

Use of rivets in the context of a dagger shielding bracer contacting a dagger is a

practical proposition. Raised rivets may catch the dagger and give time to the defender

to take advantage or at least stop it slipping to cut the arm. A rivet is always preferable

to an exposed piece of cord but a knot nearly flush to the surface, in a conical hole might

be nearly as good. The Hemp Knoll (C1) bracer has the cord attachment indicated: „a

shallow groove was chased between the perforations at either end to allow the thong to

lie flush to the surface of the bracer.‟ (Woodward, 2006). Hence the bracer most

impractical in shape for an archer‟s wrist-guard still needed its‟ attachment cord not

exposed. Attention to detail is required for equipment on which one‟s life might depend

and a cut cord would be dangerous if the encounter did not end quickly to the

defender‟s advantage.

22

Gold coverings to rivets would be a rather arrogant way of both protecting one‟s

valuables and offering a challenge at the same time to jealous people and their knives.

But credit to someone who shows off their treasure and is prepared to defend it but

without being aggressive, unlike what is possible when bearing a gold embellished

dagger. However Barnack man takes no chances with gold adorned bracer on his left

arm and a copper dagger in his right hand. Or is the dagger tied to under his left elbow

on the upper arm, where he would withdraw it as he brought his bracer up defensively?

The last thing the attacker would see would be a flash of gold in front of his eyes before

the unseen straight thrust to his middle. Check the grave drawing. (Fokkens, 2006).

There is an issue as to whether the gold fittings of the Barnack bracer cover the rivets

or replace them and hence its‟ wearability. Fokkens prefers the former view and this

writer agrees, based upon the front and back images in Smith(2006).

The prospect of „fishing‟ with the hand against an opponent who is slashing and

stabbing with a sharp dagger is an unhappy prospect, being less skilled than Dioxippos.

However keeping the fingers retracted a little towards the inner wrist with the little

stone wrist-guard outwards towards and tracking the threat it was possible with

confidence to feel for the opponent‟s wrist and with a lightning flick, grab their

forearm.

Variable Bracer Orientation on the Wrist: an Experimenters Perspective.

H. Fokkens‟ paper has demonstrated from his analysis of burials that at least 60% of

the bracers are on the outside of the wrist in what he describes as an ornamental or

non-functional position. While disagreeing with his conclusion this writer is impressed

by his methodology. Fokkens describes and quantifies a minority of internments in

which the bracer is on the inside the wrist position and some which are in an

intermediate position. He is open about the degree of uncertainty produced by the

process of internment and from processes post internment; including settling of the

tissues, rat disturbance and the overburden of sediments. What emerges is a picture of

some definite outside the wrist positions, less inside the wrist and some intermediate

positions. Why?

This experimenter sought to answer some questions about bracer use by wearing a slate

reconstruction on a longitudinally split wristlet, secured by thongs as daily attire and

accidentally found answers to the question posed in this chapter.

The putting on of a wristlet is not as straightforward as might be supposed. The hand

being bulkier at its‟ widest point over the knuckles than the wrist means that the cuff

needs to be either flexible like a modern garment or if leather, has to be split

longitudinally before in some way laced or tied tight to the forearm. All this needs to be

done with one hand and reasonably quickly given its‟ suggested vambrace role. It can

be done and there were surely several solutions, which being organic may never be

discovered. This problem is similar for thong -only attachments but one elegant solution

for the 4 hole bracer was described earlier.(Exp.Arch.,p.132).

The leather cuff was comfortable to wear despite the binding being tight enough so that

the top-heavy bracer did not slip on moving the hand. The bracer was often forgotten

about; hidden under long sleeves. However during daily activities slippages of the

bracer did occur and it was not difficult to understand why; no matter how tight the

binding. The lower forearm is basically of flattened truncated conical form. The wristlet

or bindings stay in place by friction unless disturbed. In an arm the inevitable

movement of muscles and tendons moves the bracer and attachments toward the hand.

The taper on the forearm leaves enough looseness for the bracer to find a more stable

23

position, slipping sideways during grinding an axe, or after an hour or so of normal life.

Cycling over a rough road took the bracer to the under the wrist position before it could

be corrected but the side and under the wrist position were also found after a night‟s

sleep. Similar but less convincing results(due to lack of mass) were obtained from

prolonged wear of the 4 hole cardboard and continuous loop of wool bracer.

This essay aims to show that the smaller bracers were meant to be worn nearly or all

the time. With perhaps hourly, almost subconscious adjustments the bracer could be

maintained in its‟ functional position outside the wrist if that was desired.

The variable bracer position and its‟ adjustment would have given it strong social

signalling possibilities when worn visibly and more subtly to community members if a

hidden one were adjusted under the clothes.

Taking the martial associations of the bracer with which Fokkens agrees there are

situations in which the position of a warrior‟s bracer will have clear meanings.

In a relaxed situation we might find the bracer at the side or slipped by default or

deliberate etiquette to the side or underside of the wrist. A warrior might be seen here

in family or community life, typically entering the home of a friend or relative without

causing alarm. In death, that might be an aspect of the warrior or their life and times to

be expressed. The position to the side or under the wrist might mean; „Rest in Peace‟.

It only takes a nervous twist from the other hand and the wrist-guard is in the „on‟

position, protecting the outside of the wrist-bones. This flick in a social situation is a cue

to everyone. On guard! It is not a greeting to a friend. It may be deployed at the edge of

familiar territory to be relaxed by a reverse twist as a message after a stranger has been

assessed as non-threatening.

A warrior buried with the wrist-guard on the outside of the wrist may have died in

battle but more likely than that is that the „Minutemen‟ side of their character is being

expressed; ever ready to protect their family and community.

Image: The children play outside and can be supervised while chert drilling the hard-

stone. The work has caused the bracer to slip to the underside of the wrist where it is

left for convenience. The dagger threat is considered low and that is the social signal to

be communicated to people outside the home. A right handed wearing of the bracer

might mean an aggressive dagger fighter, protecting their attacking arm from an

opponent‟s drawn dagger. A bracer might be worn on each arm for this as in modern

symmetrical dagger play

24

A Story from a Modern Community during and After the Fear of

Knife Crime

This is a true story but this writer believes that there are other true stories that may

contradict this one.

A family moved into a dwelling in a small hamlet but found it difficult to make friends.

Differences of opinion were not easily discussed and could be met by verbal threats.

There seemed to be a community but they felt excluded. People laughed around their

fires but it sounded harsh against the dark. In daytime violent disturbances went

unchallenged.

Feeling particularly threatened one night, the outcasts waited miserably.

Seeing a young warrior man-handling a woman, who was complaining loudly; the low

status man had nothing to lose and challenged the behaviour.

Offended; the warrior broke property of the outcasts. Demanding “a piece of you!”

nearly naked, the outcast wrestled the warrior to the ground. After an unbalanced

struggle, representatives of the community separated the pair and blood was seen but

there was honour and no weapons involved.

At this point modern life intervened and the police officer wearing blue plastic

disposable gloves told the former outcast that “people have been stabbed for less” and

that charges of assault should be pressed but the new member of the community

strongly disagreed and said that “All injuries are superficial”, but agreed to put some

clothes on. (AP/10/2308).

Soon after that night the commotion in a dwelling beyond ended. It was said that knife

wielding in daylight had frightened many people, but the outcast family, not knowing

anyone in the community had thought that it was only them that were suffering and

that everyone else was reconciled to it.

Now denounced and banished, the knife wielder is missed every day that children play

in the street and every night that former outcasts and warriors, young and old laugh

and settle their differences around the communal fire.

Should the person return; may they live in peace with their community.

Real peace is recognised and appreciated.

This is a life worth defending. October 2010.

Image: Injury sustained over the outer wrist bones from a struggle on a hard surface.

The Greeks prepared soft surfaces; skamma(Poliakoff 1987) for this purpose. An

archer‟s leather wristlet would have protected here but a stone bracer would have

25

needed to stay on the inner wrist position or it may have been broken. Deployment to

the outer position against a dagger would not have been required due to the honourable

nature of the opponent.

The Psychological Significance of a Stone Bracer to Individual Dagger

Defence.

This has to be at least as important in challenging the dagger as the physical properties

of the stone bracer. What one believes or feels about wearing it overcomes the hesitation

to plunge one‟s hand towards the blade.

This experimenter found that the prolonged wearing of the bracer on a wristlet

conferred additional confidence in walking abroad, with a plan ready to deploy. A

vigilant but relaxed state of mind was maintained. The preference was to wear the

bracer concealed under the sleeve, giving maximum surprise to the defender, but in our

culture of personal adornment the bracer could be worn slipped to the under-wrist on

the exposed arm without drawing glances on the street or when paying in a shop. As a

covert wearer of the wrist-guard the individual has a certain flexibility of approach to a