3 ante ING:Layout 1 - domenico...

Transcript of 3 ante ING:Layout 1 - domenico...

Rosa MenkmanOrder and Progress

Rosa MenkmanOrder and ProgressCurated by Domenico Quaranta

January 15 _ February 25 2011

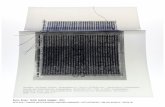

From the series "A Vernacular of File Formats" (2010):

Downsampled Joint Photographic Experts Group (.JPG)Baseline optimized. (irreversible databend)

Graphics Interchange Format (.gif), interlaced, animated256 colors, restricted pattern (with dither)(irreversible databend)

Joint Photographic Experts Group committee in 2000;low res (.JPEG 2000) (irreversible databend)

VIA Alessandro Monti 13 I -25121 BRESCIA _ Italywww.fabioparisartgallery.com

7. Yet, if it was just that, it wouldn’t be thatinteresting. Rosa Menkman’s work and, morebroadly, Glitch Art and the best contemporarycomputer-based art is not just an attempt toliberate a medium and its own languages – itis also an attempt to use them to saysomething that could never be said otherwise.Let’s look back to the early examples of theuse of deterioration and accidents in art.Edvard Munch “matured” his paintingsbecause conventional painting techniques didnot allow him to express the existential dramahe wanted to convey. The Surrealists adoptedautomatic techniques such as frottage andgrattage as a means to access theunconscious. The original shooting of theVernacular of File Formats would never havesucceeded in saying what its seventeeniterations do say. However interesting as animage, it is the result of a medium undercontrol. It is just a nice, black and whitepicture file where a heavily made-upMenkman is seen combing her hair (an explicitreference to Marina Abramovic’s Art Must BeBeautiful, 1975). It is like AnnLee before shewas bought and shared by Philippe Parrenoand Pierre Huyghe back in 1999: a ghostimage waiting to be rescued from an industrythat had condemned her to death. Similarly,the flow of data it consists of has beencondemned to be always visualized in thesame way. In his essay “Art in the Age ofDigitalization” [10], Boris Groys claims thatevery digital image is a mere copy of aninvisible original – the image file. The image fileis an invisible string of digital data; the digitalimage is the way that file is visualized (that is,

performed) in a given context. Introducing aglitch between the image file and the digitalimage, Menkman liberates the latter from itsstatus of copy of an invisible original. The same image is now different every time itis performed. From its birth to its death, it hasmany possible lives. It is no longer a copy: it isthe source of many possible originals. In the Vernacular of File Formats, this story –actually an illustrated theory – is told with anextraordinary level of pathos. The womanportrayed in the picture fades into pixel

blocks, gets grainy, duplicates, disappearsbeyond a coloured camouflage, thenreappears, violently slashed.The same oxymoron – an apparently cold,geeky theory expressed in a warm, emotionalway - can be found in her video works,especially Dear Mr Compression (2009) andCollapse of PAL (2010). In the first work,Rosa – impersonating Benjamin’s Angel ofHistory – writes a poem to Mr Compression.The dialogue appears to take place in a chatroom, and the Angel of History expresses herfeelings while a silent Mr Compression turnsher attempt at communication into anincreasingly corrupted signal. In the latter, theAngel of History reflects on the PAL signal, itstermination, and its survival “as a trace” in newer technologies. How poetry can becomposed about such a technical issue issomething we should ask Lucretius orRaymond Roussel. PAL was the analoguetelevision encoding system used in Europe,South Asia and other countries. Wholegenerations grew up with it, and got used toits specific characteristics and glitches. And Mr Compression is the personification ofa computer process. Do they deserve apoem? According to the Angel of History,they do. But Dear Mr Compression is alsothe story of a woman talking to a man thatmakes her suffer; and the live TVperformance that originated Collapse of PALwas also, according to Menkman [11], a lastattempt to deliver a message to somebodygetting the PAL signal. Is this medium-specificity? According to the Angel of History,it isn’t.

[1] Oliver Laric, Versions, 2009 – 2010. Online at www.oliverlaric.com

[2] Trond Aslaksby, “The Weathered Paintings of EdvardMunch. Artist’s intention, conservation, display – atriangle of conflicts”, 1998. Online at www.munch.museum.no/40/6/aslaksby.pdf

[3] Sylvere Lotringer, Paul Virilio, The Accident of Art,Semiotext(e), New York 2005, p. 63.

[4] James Der Derian, “Is the Author Dead? An Interviewwith Paul Virilio”, 1997. Online athttp://asrudiancenter.wordpress.com/2008/11/26/interview-with-paul-virilio/.

[5] «A glitch is a short-lived fault in a system. It is often usedto describe a transient fault that corrects itself, and istherefore difficult to troubleshoot. The term is particularlycommon in the computing and electronics industries». In Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glitch

[6] Rosa Menkman, “Glitch Studies Manifesto”, 2009 –2010. Online at http://rosa-menkman.blogspot.com/2010/02/glitch-studies-manifesto.html

[7] In Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photography[8] Nicolas Bourriaud, The Radicant, Sternberg Press, New

York 2009, p. 138.[9] Rosa Menkman, “Glitch Studies Manifesto”, op. cit.[10] Boris Groys, “From Image to Image File – and Back: Art

in the Age of Digitalization”, in B. Groys, Art Power, TheMIT Press, Cambridge – London 2008, p. 84.

[11] Email to the author, December 16, 2010.

fabioparisartgallery

3_ante_ING:Layout 1 30-12-2010 16:27 Pagina 1

Life and Death of an Image

Domenico Quaranta

1. Deterioration has always been part of thelife of an image. Any image we can think of,from prehistoric cave paintings to the latestHollywood movie, can be described in termsof its level of deterioration. Deterioration canstart straight away or come later; it can bealmost invisible, or have a huge impact on thecurrent perception of a given image. In arecent video essay [1], artist Oliver Laric showshow, paradoxically, iconoclasm made true“icons” of images that would probably havebeen of little interest for the modern tourist ifthey were not damaged; and if we think aboutRomantic painting as dark and contrasted, itis mainly thanks to the widespread use ofbituminous colours, that darken over time.That said, deterioration is usually perceived asnegative. The general view is that a damagedpiece needs restoration. But what ifdeterioration is adopted as an artistic strategy,integrated into the creative process? Beforethe age of mechanical reproduction, EdvardMunch was the only artist to address this. Hisinfamous “hestekur” (a Norwegian term thatcan be translated into “horse cure”) consisted

in leaving his paintings in the open, exposedto rain, snow, high and low temperatures,sunlight and humidity, dust and mould, tomake them physically “mature” – or die [2].

2. While deterioration has usually beenconsidered something bad, as a creativestimulus the accident has a long tradition inart: from Leonardo, who looked into the stainson walls, ashes, clouds and mud, to theSurrealists’ automatic techniques, theaccident – accidental revelations, incidentsand mistakes – has often heralded epiphany.Rosa Menkman often quotes Paul Virilio: «The accident doesn’t equal failure, butinstead erects a new significant state, whichwould otherwise not have been possible toperceive and that can “reveal somethingabsolutely necessary to knowledge”.» [3]

3. Virilio’s interest in accident is stronglyrelated to the zeitgeist of the 20th century.Today, images are not made to last; theydeteriorate at an incredible rate. Furthermore,in the age of electronic – and, later, digitalmedia – errors in communication andvisualization occur on a daily basis.Transmission goes wrong, storage media getobsolete, file formats disappear, readingsoftwares are updated. If «to invent the train isto invent derailment» [4] and «to invent the shipis to invent the shipwreck», then to invent filmis to invent scratches (as in Nam June Paik’s

Zen For Film, 1964); to invent video is toinvent white noise and signal distortions; andto invent files is to invent glitches [5]. Researchon technology has been always guided, asRosa Menkman puts it, by a «dominant,continuing search for a noiseless channel.» [6]

Artists, on the other side, have always beenmuch more interested in noise, errors, failures,glitches. But why?

4. New media – from photography tocomputers – are not neutral tools, like apencil. They have been designed to get acertain result, and they have been perfected inorder to make the process smoother and theresult better. Let’s take photography.Technically, it is a process that consists in«creating still pictures by recording radiationon a radiation-sensitive medium.» [7]

Yet it has been always viewed as a way torepresent reality, and any technicaladvancement was made with this target inmind. This is the ideology of the medium. Ifyou use it properly, there is no way to actoutside of this ideology. The only way to do itis to hack the medium. Produce noise. Triggermistakes. Exploit failures.Of course, a lot of good art has beenproduced without questioning the ideology ofa given medium. Yet, the more that mediumbecomes a mirror of power, the more noisebecomes an interesting artistic strategy. This is why hacking video is more interestingthan hacking photography. Furthermore, themore a given medium attempts to turn anycreative option into a convention, a filter, anoption in a menu – inevitably normalizing it –

the more working outside of operatingtemplates becomes interesting. That is whyhacking computers – and any computerizedmedium, including digital photo and videocameras – is definitely more interesting thanhacking any pre-digital medium.

5. And that is why exploiting the medium at itsbest has become a prerogative of mainstreamculture, while art prefers, in Nicholas Bourriaud’swords, to focus on “the indeterminacy of itssource code”: «today, one must struggle, not– as Greenberg did – for the preservation of anavant-garde that is self sufficient and focusedon the specificities of its means, but rather forthe indeterminacy of art’s source code, itsdispersion and dissemination, so that itremains impossible to pin down – inopposition to the hyperformatting that,paradoxically, distinguishes kitsch.» [8]

This quote might seem out of place here.Bourriaud is arguing against mediumspecificity, and what could be more medium-specific than exploiting a medium’s shortfalls?

This is the dead end that much criticismregarding the current artistic use oftechnology comes up against. Today, manyartists are interested in noise and glitches, lowresolution aesthetics, poor images, old media,dirty styles, but also, paradoxically, in anunprofessional, amateurish use of defaultsand presets. Is their work formalist, in thesense codified by Greenberg? Definitely not,for two main reasons.

6. It is, first and foremost, a political act ofliberation and resistance against control. They focus on the medium because they arecombating the medium’s “order and progress”ideology – the ideology brings us to the“hyperformatting that distinguishes kitsch”. In order to do so, in Menkman’s terms, they«find catharsis in disintegration, ruptures andcracks; manipulate, bend and break any

medium towards the point where it becomessomething new; utilize glitches to bring anymedium to a critical state of hypertrophy, to(subsequently) criticize its inherent politics.» [9]

They do this with the acute awareness thattheir time is short, because what they aredoing will, sooner or later, become a style, afashion, and a filter in the “tools” bar of somecommercial software. This can be seen verywell in Rosa Menkman’s work, particularly inher crazy jumping from one experiment to theother. She never uses the same glitch twice.She doesn’t like effects that are reproducible.She always looks for the unexpected, theunpredictable, the uncanny. She is a true“nomad of noise artifacts”. Let’s take theVernacular of File Formats (2010), acollection of 7 videos and 10 file formatsimages where, as she wrote, she activelydemystifies the most popular glitch effects. The Vernacular is, at the same time, an essay,a tutorial for wannabe glitch artists, and acollection of experiments that should not berepeated, but that will be inevitably be repeateduntil their aesthetic potential is exhausted.

Frame from Dear mr Compression(2010), 03’:40”

Frame from Dear mr Compression(2010), 03’:40”

Frame from Collapse of PAL(2010), 17’:00”

3_ante_ING:Layout 1 30-12-2010 16:27 Pagina 2

![Page 1: 3 ante ING:Layout 1 - domenico quarantadomenicoquaranta.com/public/CATALOGUES/2011_01_Menkman_ENG.pdf · Digitalization” [10], Boris Groys claims that every digital image is a mere](https://reader042.fdocuments.us/reader042/viewer/2022031321/5c1101ac09d3f2b60f8b661f/html5/thumbnails/1.jpg)

![Page 2: 3 ante ING:Layout 1 - domenico quarantadomenicoquaranta.com/public/CATALOGUES/2011_01_Menkman_ENG.pdf · Digitalization” [10], Boris Groys claims that every digital image is a mere](https://reader042.fdocuments.us/reader042/viewer/2022031321/5c1101ac09d3f2b60f8b661f/html5/thumbnails/2.jpg)