1.8 Calatrava Dreammachine

-

Upload

claudia-milea -

Category

Documents

-

view

29 -

download

0

Transcript of 1.8 Calatrava Dreammachine

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

Santiago Calatrava

and the Dream Machine School Program for Grades 6 8 (a collaboration with Discovery World at Pier Wisconsin)

Docent Resource Packet

Prepared by Jane Nicholson, School and Teacher Programs Manager

January 2008 [Updated February 2009]

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

2

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

3

About This Docent Resource Packet This docent resource packet describes the Santiago Calatrava and the Dream Machine school program, a collaboration with Discovery World at Pier Wisconsin. It includes background information, program goals and objectives, tour implementation ideas, and program logistics. The Milwaukee Art Museums docent-guided Calatrava tour is an opportunity for students to explore Santiago Calatravas innovation and the creative design process from the idea through the product using the Museums Quadracci Pavilion and Reiman Pedestrian Bridge as an example of his work. Also, students will have the opportunity to continue to explore the creative design process through technology, including prototyping and industrial automation, using Discovery Worlds interactive Rockwell Automation Dream Machine exhibition and hands-on Prototyping Lab. If you have suggestions or questions regarding the Santiago Calatrava and the Dream Machine school program, please contact our School and Teacher Programs Manager by calling (414) 224-3827.

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

4

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

5

Table of Contents What is the Santiago Calatrava and the Dream Machine School Program? 7 Program Summary Goals and Objectives Program Description

Program Outline

Santiago Calatrava and His Creative Design Process 9 Santiago Calatrava 9

Introduction Biography Santiago Calatravas Creative Design Process 12 Introduction Drawings Sculptures Interviews with Santiago Calatrava

Summary of Calatravas Design Process for the Milwaukee Art Museum Santiago Calatrava and the Milwaukee Art Museum Quadracci Pavillion 19 Introduction A Short History of the Milwaukee Art Museum The New Addition Design Evolves Fun Facts Interview with Santiago Calatrava Santiago Calatravas Statement About the Milwaukee Art Museum Addition Visit Descriptions and Information 31 Visit to the Milwaukee Art Museum Visit to Discovery World at Pier Wisconsin

Calatrava Tour Implementation at Milwaukee Art Museum

Calatrava Quadracci Pavilion Study Worksheet for Students 37

Vocabulary 39

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

6

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

7

What is the Santiago Calatrava and the Dream Machine School Program?

PROGRAM SUMMARY The Milwaukee Art Museums and Discovery World at Pier Wisconsins Santiago Calatrava and the Dream Machine collaborative school program provides students in grades 68 an opportunity to learn about the creative design process combining art, science, and technology. This program includes a one-hour docent-guided Calatrava tour at the Milwaukee Art Museum and a one-hour hands-on experience in Discovery Worlds Rockwell Automation Dream Machine exhibition and Prototyping Lab. Using the work of Santiago Calatrava at the Milwaukee Art Museum, students explore Calatravas innovation and the creative design process from the idea through the product. Using the interactive Rockwell Automation Dream Machine exhibition and hands-on Prototyping Lab at Discovery World, the students continue to explore the creative design process through technology, including prototyping and industrial automation.

PROGRAM GOALS AND OBJECTIVES The primary goals of the Santiago Calatrava and the Dream Machine collaborative school program are:

To provide students in grades 68 with an opportunity to learn about the creative design process combining art, science, and technology.

To help students make personal and practical connections with the creative design process.

To engage students in discussions and the creative design process.

To raise an awareness about careers in art, architecture, engineering, science, and technology.

To help teachers use art, science, and technology with their existing classroom curricula to teach about the creative design process.

To utilize both the Milwaukee Art Museum and Discovery World at Pier Wisconsin as teaching resources.

The primary learning objectives of the school program are that students will:

Understand that innovation/creativity begins with an idea.

Identify basic steps of the creative design process, including: o defining the problem or goal o finding solutions and ideas o documentation of ideas o testing, reflecting, and refining ideas o production

Explore connections between Santiago Calatravas creative design process and their own creative design process.

Discuss the relationship of art, architecture, science, and technology.

Develop a basic understanding of prototyping and industrial automation.

Create a product prototype using science/technology.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION The Milwaukee Art Museums and Discovery World at Pier Wisconsins Santiago Calatrava and the Dream Machine collaborative school program provides students in

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

8

grades 68 an opportunity to learn about the creative design process combining art, science, and technology. Trained docents lead The Milwaukee Art Museums one-hour thematic visit, actively and creatively engaging the students in the specific topic of the tour. Tours include various questioning and critical thinking strategies, along with use of gallery teaching aids. After the Calatrava tour at the Milwaukee Art Museum, students walk to Discovery World at Pier Wisconsin for a one-hour hands-on experience in the Rockwell Automation Dream Machine exhibition and the Prototyping Lab. Students explore and discuss the exhibition, which uses models of local landmarks to show how automation and control are a part of our daily lives, and create an automata prototype. This 2-hour program is developed for school groups of 10 30, maximum, students. Groups of 26 or more students will rotate activities while at Discovery World. This program is available Tuesday through Friday, except Thursday mornings. Lunch facilities are available at Discovery World upon request. Call the Milwaukee Art Museum at 414-224-3842 to schedule your Calatrava tour, and then call Discover World at 414-765-8625 to schedule your Rockwell Automation Dream Machine and Prototyping Lab visit.

FEE Regular general school group tour fees of $2 per student apply to your Milwaukee Art Museum visit. One adult chaperone per ten students is required; these adults are admitted free of charge. An additional fee of $5 per student is charged by Discovery World at Pier Wisconsin for this collaborative school program.

PROGRAM CONTACT For more information about how your school can participate in this collaborative school program, contact: School and Teacher Programs Manager Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive Milwaukee, WI 53202 phone: 414-224-3827 fax: 414-271-7588

February 24, 2009

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

9

Santiago Calatrava and His Creative Design Process

SANTIAGO CALATRAVA Introduction In a century dominated by specialization and fragmentation, Santiago Calatrava is one of the few designers who can be called universal. His numerous buildings, engineering projects, sculptures, and furniture designs, consistently create a unique poetics of morphology that merges structure and movement. He transgresses the artificial distinctions between art, architecture, science, and technology, between reflection and action, between memory and creation, between problem-solving and wonder, in order both to posit a cultural vision permeating personal and professional lives, and to establish a new paradigm for practice. Within this new paradigm, Calatrava selectively recalls established knowledge, then reuses and reinterprets it to serve each projects requirements. He casts seemingly hackneyed analogies in a new light. He critically reassesses architectural rules and deepens our understanding of the more fundamental, more comprehensive problems of architecture. He invites us to rethink form, construction, and use of buildings by breaching current professional routines and by overcoming existing barriers between professional institutions. His sculpture serves as a research laboratory for highly technical projects. His technical infrastructure projects, in turn, offer the text and plot for highly abstract aesthetic essays, sculpture, and engineering techniques that promote cultural quality, life, and meaning in the human community.

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

10

Calatravas designs work on three levels. First, they solve problems by providing optimal schemes. These solutions, in turn, represent the core beliefs and desires that explain the designs. And finally, Calatravas design solutions encourage us to question where these beliefs and desires come from and why they are essential to humanity. Calatrava responds to all three issues. His basic design strategy is to make the search for optimal solutions, the discipline of critical inquiry, and the spirit of experimentation and adventure work together in the same scheme. His projects are unique because they satisfy views not through compromise but through a higher level of synthesis. This requires not only an excellent grasp of multiple domains but also the cognitive competence to create. The offspring of this process is a new type of design artifact: an amalgam of sculpture and tool, a new, broader, definition of technology, and a new type of contemporary practice for architects, engineers, and artists. By overcoming the borders separating art, architecture, and engineering, Calatrava broadens our collective understanding of the artificial environment and provides new ways to improve cities and landscapes and the human communities within them. [Excerpted from Tzonis, Alexander. Santiago Calatrava: The Poetics of Movement. New York: Universal

Publishing, 1999. pp. 9-10.]

Speaking Spanish, English, French, and German with almost equal fluency, crossing barriers between art, architecture, and engineering as easily as he seems to change countries, Santiago Calatrava is clearly a figure to be reckoned with, a leading light of the genration that is now beginning to dominate world architecture.

Biography Santiago Caltrava is an architect, artist, and engineer. He was born in the town of Benimamet, near Valencia, Spain, in 1951. Calatrava is an aristocratic name, passed down from a medieval order of knights. The family on both sides was engaged in the agricultural export business, which gave them an international outlook that was rare during the Franco dictatorship. Santiago Calatrava attended primary and secondary school in Valencia, Spain. From the age of eight, he also attended the Valencia School of Arts and Crafts, where he began his formal instruction in drawing and painting. When he was thirteen, his family took advantage of the recent opening of the borders and sent him to Paris, France, as an exchange student and to learn French. At age seventeen, his mother sent him to Zurich to learn German. He later traveled and studied in Switzerland as well. His travels and the challenge of mastering new languages quickly enriched Calatravas cultural and design experiences, while simultaneously establishing a sense of independence, self-mastery, and responsibility. Immediately after completing high school in June 1968, Calatrava enrolled at the Escole des Beaux-Arts in Paris only to discover the school, students, and city in total upheaval. The social unrest of Mau 1968 had not only closed the Ecole, but its proponents declared dead the very institutes of art, design, and architecture that Calatrava had come to Paris to embrace. Returning to Valencia out of practicality, Calatrava enrolled in both the Architecture School and the Arts and Crafts School. He received his undergraduate degree from the Escuela Tecnica Superior de Arquitectura, Valencia, Spain. His undergraduate years were bracketed with formal study in two other subjects that also exort strong influences on his built work: one year of study in art and a graduate course in urban studies.

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

11

Trained in the 1970s, Calatrava felt undernourished by the functionist rhetoric then in vogue in European architecture schools: It was time for a revolution. To discuss aesthetics was considered bourgeois, decadent. He was frustrated by didactic instruction and wanted to find his own way to understand architecture: Learning was handed to meI preferred to hear a bird singing rather than a person singing like a bird. Dissatisfaction with his architectural education was one reason he went on to study engineering, but his intellectual hunger was stronger. Instead of choosing a major he chose everything. I love drawing and painting and sculpture. I also love the rigor of mathematics. My descision was to stay in between. Soon after graduating in 1975, he departed for Zurich, Switzerland, to refine his art and architecture training. Calatrava earned a doctorate in civil engineering at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich. Caltrava spent four years on his doctorate in engineering. His thesis was a systematic examination of foldable or movable structures. Until I was 30, I worked rigorously at this. In that program, Calatrava felt he was unshackled. He received his Ph.D. in 1981. To those who think structural engineering is a purely technical field, the idea that it was liberating to Calatrava may seem odd. Engineering design does not mean calculating things; that is just a small part of it, Calatrava says. For him, engineering supplies the last piece: with it he could solve the entire problem himself. So finally, the architecture design and the engineering design became the same thing. After completing his studies, Calatrava took a position as an assistant at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and began to accept small engineering commissions. He also began to enter competitions, believing this was his most likely way to secure commissions. His first winning competition proposal, in 1983, was for the design and construction of Stadelhofen Railway Station in Zurich, the city in which he established his office. In 1984, Calatrava won the competition to design and build the Bach de Roda Bridge, commissioned by the Olympic Games in Barcelona. This was the beginning of the bridge projects that established his international reputation. Among the other notable bridges located in Spain that followed were the Alamillo Bridge and La Cartuja Viaduct, commissioned for the Worlds Fair in Sevilla (1987-92); Lusitania Bridge in Merida (1988-1991); Ondarroa Bridge in Ondarroa (1989-1995); Campo Volantin Footbridge in Bilbao (1990-1997); and Alameda Bridge and Underground Station in Valencia (1991-1995). The attendant growth of his practice led him to establish a second office in Paris in 1989.

During this phase of his career, Calatrava won a reputation for designing other large-scale public projects as well. These included BCE Place Mall in Toronto (1987-1992); Lyon-Stolas Airport Railway Station in France (1989-1994); Sondica Airport in Bilbao (1990-2000), Tenerife Concert Hall in the Canary Islands (1991-2003); the City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia (1991-2004); and the Orient Railway Station in Lisbon (1993-1998). He also won the design competition to complete the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City (1991), a project that has not been realized. A large number of Calatravas projects are engaged with movement. They do this in two principle ways: first, through parts of the structure that serve functional needs by explicitly moving (unfolding, rising, revolving, or channeling) objects, people, and vehicles; and second, through parts of the structure that implicitly represent movement

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

12

through their form. In the latter case, the very designs prompt us to reenvision the problem-solving process of the designer. He has developed a rare knowledge set and it informs all of his design work. The Milwaukee Art Museum addition is such a complete synthesis of design and engineering that it could not have been conceived by someone without training in both fields. [Excerpted from Kent, Cheryl. Santiago Caltrava Milwaukee Art Museum Quadracci Pavilion. New York: Rizzoli, 2005. p. 39, 114-115; and excerpted from Tzonis, Alexander. Santiago Calatrava: The Poetics of Movement. New York: Universal Publishing, 1999. pp. 15-29.]

CALATRAVAS CREATIVE DESIGN PROCESS Introduction Santiago Calatravas projects recall the way the body of a complex living organism is put together. This is one of the reasons his bridges, observation towers, and building complexes fit and enhance the landscape like enormous organisms growing out of it or living within it. His forms, however, are not mimetic. His is not an organic style. His schemes, rather, draw on nature, taking cues from the way the skeleton, the circulatory system, and the skin of organisms especially the human body function and flourish. In searching to develop a morphology of movement, he draws dramatic significance from the human bodys acrobatic action the dancers gravity-defying gestures to capture the shape of change and immerse it in a world of flux. As a result, Calatravas structures, when embedded in the landscape like a tree, tend to enhance that landscapes own uniqueness rather than subjugate its character. When placed in forgotten, peripheral parts of a city, Calatravas creation brings about hope and renew desire. [Excerpted from Tzonis, Alexander. Santiago Calatrava: The Poetics of Movement. New York: Universal

Publishing, 1999. p. 12.]

There are two highly polarized ways to invent a design scheme: the analytical and the analogical. In the context of the division of labor and the institutional split of Western architecture and design, engineers prefer the first, and architects and artists the second. Calatrava employs both. In his theoretical study On the Foldability of Space Frames, completed at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Calatrava took the analytical path. He developed a general method to transform all possible types of space frames into planar shapes and lines, similar to the way an umbrella opens a broad plane or folds into a stick. As a result of his research, Calatrava found in the method a very useful tool that enabled him to make structures spread easily in all directions, taking different forms. He could give concrete form to his visions of fluid, waving structures, and incorporate them into any component of a project that could move with and adapt to a world in flux. It is obvious that designers rely on analysis only to a very limited degree. In most cases creative design is motivated by imagination, intuition, or insight. These terms, however, indicating the act of looking inside, disclose very little about the complexity of thinking that generates original designs or about the nature of the mysterious mind that gives birth to what Herbert Read (author of The Forms of Things Unknown, Ohio, 1963) has called the form of things unknown. The concepts of analogy and metaphor come closer to the process of transferring knowledge from one domain to another, the mental leaps that underlie creativity. In contrast to the process of analysis, which begins with a very simple list of principles and definitions to construct carefully, step by step, a rich

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

13

world of new objects, the process of analogy creates unprecedented design through the rethinking of precedents. Most artists, architects, and even some engineers do not build their inventions on unformed experiences and knowledge. The new does not come from nowhere as much as the avant-garde has often claimed. In fact, the unprecedented design often emerges from a thorough understanding of history. The best ally of invention is memory. Looking at the work of Santiago Calatrava from this perspective, and considering the notebooks full of drawings of the natural world and the human body alone or in groups, loosely gestured or carefully detailed, and combined with bridges or buildings or animals we see the role such precedents played as sources for analogies and metaphors in his architecture and engineering projects. Positions, gestures, profiles, skeletons, muscles, organs, skin, wings, trees, plants, and birds are constantly recalled, reinterpreted, and projected into project schemes. They invite new ways of looking at structure and enclosure. They make the unfamiliar familiar and make possible inventive solutions to difficult problems of structure and site.

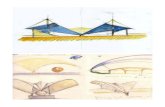

Drawings As we look through Calatravas notebooks and the strange forms of his projects, we rediscover the components of the human form and bird wings from the sketchbooks in the mobile elements of his architectural projects. And the fronds of the palm tree, human spine and ribs, or once again fingers in this case, interlocking hands reappear as roof components in the Kuwait Pavilion and Milwaukee Art Museum Quadracci Pavilion. In Calatravas sketchbooks, eyelids are transformed into the roof of an observatory, a birds beak into a roof shell, dancing men into interlocked support nets. Calatravas projects are compositions that involve seeing one thing as something else. For Calatrava, new objects/structures (or solutions) are born from pairing previously unrelated objects (or problems). They become fused because of a common formal similarity, a homology of parts, a parallelism between contour lines, or co-location of figures. It is this property that permits the seeing of one thing as another. Out of its similarity a new form may be inferred in analogy to an old one. Again and again, Calatravas sketches/designs reveal the subtle similarities between configurations he has drawn from trees, blossoms, birds, human bodies, hands, eyes, or fish and his schemes. Calatravas drawings/ideas, however, not only disclose similarities between static objects or forms at rest but also between the movements carried out by different objects. Thus, the movement of one object prototype is applied to a new design project. Buildings, sculptures, or engineering projects expand and contract, burgeon and bloom, open and close, dilate and billow, rise and fall in analogy to a movement characteristic of a bird, a flower, a part of a human body. In other words, in addition to reframing life forms into architectural features, Calatrava also redesigns life processes themselves. Calatravas sketchbooks reveal that whenever he is compelled to invent the form of a new column, or beam, or roof structure to fulfill new programmatic requirements or contextual conditions, he gives shape to objects not yet born by using the forms of existing objects to fulfill a certain task. By bridging past and future objects, he engages in a transfer of design knowledge instead of assembling it piece by piece. Analogies such as those on which Calatravas design thinking is founded reveal our innate ability to act upon and react to new environments by using forms found in nature and artifacts.

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

14

Calatravas work has the following characteristics: o He draws human figures, bodies, faces, hands, eyes, plants, birds, all shapes

from which he draws inspiration for his structures. In his sketches he develops and transforms his ideas into architectural forms: his projects are illustrated in great detail, and he makes clear their technical and constructional requirements. In his creative design process and work, the drawing plays a fundamental part.

o The prevalence of curves in tension, used not as static, geometrical forms but as dynamic figures, the product of points or forces in sequence; or rather of a point or force moving in space; lines whose reduplication, multiplication, and organization into systems generate surfaces and structures; lines evoking, or containing, a movement.

o Some kind of empathy with building materials, prior even to that with natural form, leading to wisdom in the selection, use, and modeling of materials and their combination steel, wood, glass, marble, reinforced concrete that stems from an almost tactile familiarity with the material, and understanding of its suitability for a particular shape or form.

o The relationship between the single element and the whole, that repeated, defines the rhythm, and the proportions between the various parts of the building, create a fourth dimension elevated by explicit and implicit movement. The fixed structural shapes, crucial to defining architectural space, become unpredictable under the changes and movement of the natural light, and moveable forms appear to follow the solar cycle.

o A concern for defining and controlling every last detail of the work, allied to the creative intent more even than to any technical necessity.

o The great stimulus and inspiration to his architecture is in the natural world of plants and human and animal forms -- bones and their articulation into the machines that underlie the flesh organs and connective tissue of complex animals. For example, wings so prominent among his most striking roofs are really a sub-department of skeletal articulation. They are conceived as bony webs that open and close controlling light and shade as with a brise soleil or on which a fabric or covering is stretched. His architecture is organic, not in the sense that it reproduces the shapes of humans, animals or plant fossils, but because it applies structural solutions that have already been found and tested by Nature.

Sculptures How can the human body be envisioned as a building? How is an analogy drawn? For Calatrava the answer lies in another series of his artworks: the sculptures, which have been as important and as numerous as his figure sketches. Made of elementary parts often cubes and prisms, rods, cables, or planar folded surfaces they are the first level of the concrete through which Calatrava maps and matches forms and ideas, reframes bodies as design schemes, and begins to think metaphorically. His sculpture serves as a research laboratory for highly technical projects. Calatravas abstract sculptural forms are unique in their intention to discover through abstract combinations of form the rules of morphology and movement of the concrete body in motion. In combining both the analysis and analogy approaches, Calatravas morphological investigations are close to the humanist tradition to Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) in their interest in understanding the structure of natural organisms and abstract forms and linking structure to movement. In fact, Calatravas use of mathematics brings him closer to da Vinci than to Goethe, who found mathematics inappropriate for analyzing organic nature.

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

15

The relationship of Calatravas sculptures to his built designs is complex, even if some forms, such as the bird-like wings of the Milwaukee Art Museum addition, are readily identifiable in his sculptures. Sometimes I create structural compositions, which you can call sculptures if you like, says Santiago Calatrava. They are based on very personal ideas. Just like Federico Fellini (1920-1993, Italian film director) or Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998, Japanese film director and screenwriter) made drawings before their movies, I make sculptures. Santiago Calatrava makes frequent references to the art, and this is undoubtedly one of the keys to his work.

INTERVIEWS WITH SANTIAGO CALATRAVA

By Architectural Records AR: How do you formulate your ideas and develop them? CALATRAVA: I try to emphasize the importance of place. The very first impression will come from the place. And I think it is fundamental to establish a link of feeling with this place. Another relevant element that I would like to emphasize is the human context. So along with the topographical landscape, climatic environment, and cultural landscape as a natural event, we also have the human climate. And with those elements I then begin a work of synthesis. I try to express ideas as best I can maybe by sketching on paper. At this point, the sketch is the first manifestation of the idea. In terms of a graphic language, it is just the result of an idea that comes from these factors combined. I explained that in a very rational way, but things dont always happen so rationally. Sometimes you think this is the real shape for a place. But, when you say the real shape you also mean this is the shape that solves the problems or part of them, because you are also able through your experience or capacity for synthesis to understand that [problems can be solved] in this shape or in this volume. Understand? This is most easily done in buildings that dont have very complex structures in terms of function. For example, if we are thinking of a bridge, which is a simple link, or a station. When I work on projects with more complex structures I subdivide the objects in two parts. One we could call a container, in which many things can happen, and another will be a single part. This technique, this method of approach, was used at the station in Lyon and in Lisbon. AR: In Lisbon? CALATRAVA: And in Milwaukee also. You design a part of the building that is much more the idea part and then the rest of the building, because the rest of the building in all its complexity needs a certain operational understanding of the development of the architecture, in terms of economics, in terms of the structure, in terms of modulation and division. Very briefly, I dont believe very much in causality. As an architect I think you have to control your ideas and your shapes, which should emerge very much from a rational

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

16

effort. For this it is necessary to create a theoretical background or a background of research. In my work this research is based on morphology, that I do through sculpture. AR: Your research involves what we call art. Do you use sketching as a method of seeing? CALATRAVA: The sketch is the instrument that helps me materialize the ideas to another level. And the most abstract way to do studies of morphology probably is sculpture. One draws the human body to understand the movement, the gesture. The place, the landscape, the human landscape, and topography are important for me. These will inspire or bring the essence [to a project]. Then, also the analysis of the functional program is important. You can channel all the impulses of free thinking, free feeling, shape, form, the natural [flow], and this goes from the sketches and the human body into the sculptures.

[Excerpted from an interview of Santiago Calatrava by Rober Ivy, editor-in-chief at Architectural Records http://archrecord.construction.com/people/interviews/archives/0008Clatrava-1.asp]

By John Tusa from BBC Radio JT: Lets talk about this business of biomorphism, that is the fact that your buildings, not just some but a lot of yours, look like shapes from the physical world: birds, inside ribcages, etcetera. Why is biomorphism important to you? Is it important from the metaphorical point of view, or is it important from an engineering point of view as well? CALATRAVA: In the beginning you see of my work I was very much looking for patterns of understanding a way you know to, to lets say who will permit me to get out of the academic standards from which I was merging, you understand, so I came after forty years of studies you see as a free professional, and of course you see the first reflects will be almost you know repeat..?.. this what you has learnt, what it is what your teachers has shown you that you should do, so JT: It is just, were you taught essentially in the modernist post Bauhaus tradition? CALATRAVA: Exactly, and the first thing I approached was the fact of finding patterns of thought. For example, it could be one like this: the larchitectura depende del la membra deluomo, which is just a very old Italian sentence written in the Renaissance: the architecture depends on the human members, of the human JT: Human limbs? CALATRAVA: Yes, and it means that your body almost is architecture. So indeed you see if you put your hands together you see or, or your face you see the expression of your mouth, you see even your, the proportions. Of your body, all those things you see has an archi, lets say are patterns of understanding of architecture. And it is very interesting looking at the human person because finally its the use also of the building. Isnt it? So the, the human person became the cannon not only for the measurement and the proportion of the internal and more intimate parts of the building: the things that you can touch, where you sit, where you sleep and things like that; but it became also the cannon and the pattern for the overall building. I thought that quite a fascinating idea.

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

17

. . . JT: So theres no reason why buildings should just be matchboxes, you can design them to do anything? CALATRAVA: Yes, and although if you look at the engineers approach to know and study the water, you know, by watching water, and study lets say the slopes of the soil, you understand what I mean by watching the soil and, and will make a retaining wall you know to retain water and has to deal with something so natural like wild stream or things like that, so the relation of engineering and natural is a wonderful key. Its you see whatever you think is artificial, you understand, whatever we think so I can draw an apple, you see I can draw an apple, but you see nothing to do with an apple its just a drawing, you understand it is similar to an apple so you can also note you see its not edible, you understand so I mean its, its just to tell you that as soon as you project a thought you are in an artificial world. So this is all faculty also, so featuring natural we create, we create craters you see who has following the patterns of the natural belongs to a completely different world which it is the world of our mind and through that they become art, artifacts, they became artificial, they became artifacts and they may, even maybe they may become art. JT: So they, of course, are not animals, or the fact they look like animals is an engineering solution rather than a, well it is a metaphorical solution but youre saying that it has been modified. The original idea of saying let us make something which is like a human being so to say, but by the time you have made the building it doesnt matter that its like a human being, it is a building, its completely artificial? CALATRAVA: Its very beautiful as you define it, it looks like animals. You see, another author you know who impressed me very much is Victor Hugo, he has a wonderful book called Notre Dame de Paris, and he describes in Notre Dame de Paris the cathedral as an animal, you know with the legs inside the column. Indeed when you go there nothing to do with an animal, but its a way, its a metaphorical way to introduce you in a world of understanding something. So you see, even artists like Victor Hugo you know needs also the use of metaphor to express something about a wonderful building, so you can now feed back, you see you could have started by the metaphor and you may maybe be in a way you see close to undertanding a poetic issue to wrap a building.

[Excerpted from an interview of Santiago Calatrava by John Tusa at BBS Radio http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio3/johntusainterview/calatrava_transcript.shtml]

Summary of Calatravas Design Process for the Milwaukee Art Museum 1. Look at nature for inspiration after viewing project site; sketches of natural

objects and human forms [2-dimensional]

2. Pencil sketches and watercolor drawings of architectural ideas [2-dimensional]

3. Prototype/maquette scale model (white model) of proposed architectural idea [3-dimensional]

4. Photomontage/computer-generated image of exterior architecture (color) [2-dimensional]

5. Formal architectural drawings and mechanical plans [2-dimensional]

6. Construction of full-scale building [3-dimensional]

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

18

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

19

Santiago Calatrava and the Milwaukee Art Museum Quadracci Pavilion

INTRODUCTION In 1994, Spanish-born architect, artist, and engineer Santiago Calatrava (b. 1951) was chosen to design the Milwaukee Art Museums new addition. In 1996, his dynamic design was unveiled and ground was broken in December 1997. The Calatrava-designed Quadracci Pavilion, completed in October 2001, was his first completed building in the United States. The new addition features a 90-foot high glass-walled reception hall enclosed by the Burke Brise Soleil, a sunscreen that can be raised and lowered creating a unique moving sculpture. The Quadracci Pavilion, itself a work of art, is a stunning mixture of white concrete, glass, maple wood floors, white Carrera Italian marble floors, and breathtaking views of Lake Michigan and the City of Milwaukee. This work also encompasses an elegant cable-stayed bridge, connecting the Museum and lakefront to downtown streets.

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM Milwaukee in the 1880s was a thriving port city, mostly German-speaking, with an industrial base that included wheat traders, meat packers, tanneries, shipyards, brickyards, and breweries. The stream of new immigrants arriving daily was mainly northern Europeans Irish, German, Scandinavian, Polish, Czech, and Italian. They brought with them their culture languages, traditions, and renowned craftsmanship. These craftspeople included a large group of talented German artists who specialized in panorama painting. These large-scale panoramas were hugely popular entertainment at the time a precursor to the movies. The experience included narration and music. Civil War battles were especially popular. After their run in Milwaukee, the giant canvases were rolled up and sent on tour to other cities. These panorama artists, along with several Milwaukee businessmen, formed the Milwaukee Art Association, which organized its first public exhibition in 1888. The Milwaukee Art Association encouraged Frederick Layton, owner of a meat packing business to fulfill a promise he made earlier to establish Milwaukees first art gallery. A classic-styled building was built downtown on the corner of Mason and Jefferson Streets and opened in 1888 as the Layton Art Gallery. By 1912, the Milwaukee Art Society, an outgrowth of the Milwaukee Art Association purchased a building on Jefferson Street near the Layton Art Gallery. By 1918, the Society changed its name to the Milwaukee Art Institute. After World War II several groups began looking for a suitable memorial for the war dead. After several years, plans for a center on the shore of Lake Michigan took shape, to include county veterans organizations and an art center. Famed Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen was commissioned to design the building. After the architect died in 1950, his son Eero Saarinen took over the project. Construction began in 1955, supervised by Milwaukee architects Maynard W. Meyer & Associates. Eero Saarinens innovative design for the War Memorial Center was influenced by the abstract geometry of modern French architect Le Corbusier. Saarinen incorporated many of Le Corbusiers ideas: lifting the bulk of the building off the ground on reinforced columns; eliminating load-bearing walls to allow a freeform faade and open floor plan;

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

20

and using plazas, courtyards, and rooftop terraces to allow an interaction between internal and external spaces. The building, a concrete, steel, and glass cruciform floating on a pedestal, included three major components, as Saarinen described: One is the base, which builds the mass up to the city level and contains the art museum; the second, on the city level, is the memorial court with a pool The court is surrounded by the polyhedron-shapes piers, which support the building and also make frames for the breathtaking views of the lake and sky. The third part is the superstructure, cantilevered outward thirty feet in three directions, which contains the meeting halls and offices of the veterans organization. In 1957, the War Memorial Center was opened and dedicated To Honor the Dead by Serving the Living. The western face of the building features a memorial mural by Wisconsin artist Edmund Lewandowski, a mosaic of 1.4 million pieces of marble and glass. The Milwaukee Art Institute and the Layton Art Gallery merged their collections and projects to form the Milwaukee Art Center. In the late 1960s, Peg Bradley, wife of Harry Lynde Bradley who co-founded the Allen-Bradley Company offered her entire collection of more than 600 modern American and European artworks to the museum. She also made a $1 million challenge to Milwaukeeans for an addition to the Art Center.

Eero Saarinen Architect David Kahler Architect Milwaukee County War Memorial Center (1957) T he New Wing (1975)

In 1970 architect David T. Kahler of Kahler, Slater, Fitzhugh Scott, Inc. (a local firm now know as Kahler Slater Architects, Inc.) drew a plan for expanded galleries, a changing exhibition space, a theater, and an educational center. The new addition opened in 1975. In 1980 the name was changed to the Milwaukee Art Museum, to reflect the developing role of American art institutions. Museum attendance and membership increased dramatically. The Milwaukee Art Museum also had an ever-increasing role in educating Wisconsins youth through its programs. More space was needed to house the collection and conduct educational programs. By the 1990s, the groundwork was being laid for yet another major addition. In 1994, Santiago Calatrava was chosen as the architect to design the new addition. The building opened on September 14, 2001.

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

21

THE NEW ADDITION DESIGN EVOLVES People say when somebody writes his first novel it is always autobiographical. I think in a way, that this [Milwaukee Art Museum addition] is a little like that autobiographical because it has part of my interest in movement and the bridge.

Santiago Calatrava, Zurich, August 30, 2004 In the Milwaukee Art Museum, Calatrava found a problem that could be solved with the things he most liked to design and to build, a bridge and a large moving architectural form. But origianlly neither the bridge nor the brise soleil was a part of the design. The first scheme was bold. Santiago Calatrava imagined a great hall suspended out past the Lake Michigan shore and hovering above the water. Not only was the idea impractical because of what damage ice and waves could do to the building, but it also placed the buildings emphasis on the waterfront, away from the city. Returning to the design, he focused on connecting the Museum to the city. The rough outlines of the solution came to him: long galleries running north-south brought the museums new entry near its southern end in line with one of Milwaukees principal east-west streets, Wisconsin Avenue. The basic building layout would be similar to cathederals in Western ecclesiastical architecture. A long central nave [made up of the Museums Lubar Auditorium, Museum Store, and Baker/Rowland Galleries] flanked by aisles [includes both the Baumgartner (east) and Schroeder (west) Gallerias] and with a transept [forming the main entrance to Windhover Hall and prow] sticking out past the sides of the building. The bridge also became a part of the design, literally connecting the Museums front door with downtown Milwaukee. In July 1995, Calatrava presented this design to the building committee, which embraced it.

Watercolors by Santiago Calatrava

At the same time, Calatrava had begun to think about the brise soleil. Calatrava had made one rough model that was operated by pulling a string. By February 1996, the architect had a refined model and a video he showed to the building committee. Immediately, the building committee agreed to add the brise soleil.

Prototype models by Santiago Calatrava

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

22

The completed Milwaukee Art Museum project features the new Santiago Calatrava-designed Quadracci Pavilion, renovated and reinstalled galleries in existing Museum buildings designed by Eero Saarinen (1957) and David Kahler (1975), and an elegant network of gardens, hedges, plazas, and fountains designed by landscape architect Dan Kiley.

Photo: Christophe Valtin Photo: Jim Brozek

Galleria, Quadracci Pavilion

The first Calatrava-designed building to be completed in the United States, the Milwaukee Art Museums Quadracci Pavilion, incorporates both cutting-edge technology and old-world craftsmanship. The hand-built structure was made largely by pouring concrete into one-of-a-kind wooden forms.

Drawing courtesy Milwaukee Art Museum

Computer-generated photomontage of Photo: Christophe Valtin the Reiman Pedestrian Bridge

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

23

Signature elements of the Calatrava design include the Reiman Pedestrian Bridge, a 250-foot long suspended pedestrian bridge that links downtown Milwaukee directly to the lakefront and the Museum. The bridge features a distinctive 200-foot angled mast with cables that reflects Calatrava's unique experience in bridge design throughout Europe. Windhover Hall is the grand entrance hall for the Quadracci Pavilion. It is Santiago Calatravas postmodern interpretation of a Gothic Cathedral, complete with flying buttresses, pointing arches, ribbed vaults, and a central nave topped by a 90-foot-high parabolic-shaped glass roof. An average-sized, two-story family home would fit comfortably inside the reception hall.

The halls chancel is shaped like the prow of a ship, with floor-to-ceiling windows looking over Lake Michigan. Adjoining the central hall are two-arched promenades, the Baumgartner Galleria and Schroeder Foundation Galleria, with expansive views of the lake and downtown. The Burke Brise Soleil, the movable, wing-like sun screen comprised of 72 steel fins, rests on top of the glass-enclosed reception hall and is raised and lowered to control both temperature and light in the structure. With fins ranging in length from 26 feet to 105 feet, the Burke Brise Soleil wingspan spreads 217 feet at its widest point, wider than a Boeing 747-400 airplane, and weighs 90 tons. It takes 3.5 minutes for the wings to open or close. Sensors on the fins continually monitor wind speed and direction; whenever winds exceed 23 mph for more than 3 seconds, the wings close automatically. According to Santiago Caltrava, in the crowning element of the brise soleil, the buildings form is at once formal (completing the composition), functional (controlling the level of light), symbolic (opening to welcome visitors), and iconic (creating a memorable image for the Museum and the city). Calatrava's designs are often inspired by nature, featuring a combination of organic forms and technological innovation. The Milwaukee Art Museum expansion incorporates multiple elements inspired by the Museum's lakefront location. Among the many maritime elements in Calatrava's design are: movable steel louvers inspired by the wings of a bird; a cabled pedestrian bridge with a soaring mast inspired by the form of a sailboat; and a curving single-storey galleria reminiscent of a wave. "Rather than just add something to the existing buildings, I also wanted to add something to the lakefront. I have therefore worked to infuse the building with a certain sensitivity to the culture of the lake - the boats, the sails, and the always changing landscape". - Santiago Calatrava, ca. 2001 [Excerpted from http://www.arcspace.com/architects/calatrava/milwaukee_art_museum/]

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

24

FUN FACTS

Quadracci Pavilion

30% increase in gallery space from 90,000 sq. feet to 117,000 sq. feet

Pavilion length = 293 feet

Total building weight = 93 million pounds

Structural mast: length = 198 feet; lean angle 41.64 Cable-stayed Reiman Pedestrian Bridge:

o length = 280 feet o supported by 3,300 feet of locked coil cables o suspension cable diameter is 50 mm (approximately 2 inches) or

35 mm (approximately 1 inches) o 200-foot long angled mast o Longest tension cable is 252 feet long nearly as long as a

football field

Windhover Hall: parabolic-shaped glass enclosed with a 90-foot high ceiling

o parabola (pronounced /p rbl/)

Quadracci Pavilion Architect: Santiago Calatrava, Spain.

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

25

Cudahy Gardens

Fountains have seven separate sump pumps that hold approximately 12,000 gallons of water each supplying the two fountains and five troughs.

Main garden site is 600 feet long and 100 feet wide and parallels the new addition/pavilion

Fountains rise to 35 feet within a 40-foot pool

Cudahy Gardens landscape Architect: Dan Kiley (1912-2004), Boston Burke Brise Soleil

Wingspan: 217 feet at its widest point, individual fins range in length from 26 to 105 feet, wider than a Boeing 747-400 airplane

The 72 fins weigh 90 tons and are operable via 22 hydraulic cylinders.

Two ultrasonic wind sensors automatically close the wings if the wind speed reaches 23 mph or greater.

Materials Used:

Concrete: roughly 20,000 cubic yards, weighing 81 million pounds.

Steel: approximately 2,100 tons of reinforcing rod has been used in the concrete, laid end-to-end, would stretch 339 miles (or roughly from Milwaukee, WI to the Twin Cities, MN).

Glass: approximately 915 separate panes. Fewer than 6% are standard orientation window glass; the rest are either tilted, curved, or both. 235 panes of glass for the roof of the grand reception hall were imported from Greanollers, Spain.

Marble: one acre of marble from Carrera, Italy, for the floors. Consists of six miles of PVC piping through which water circulates for heating/cooling.

Comparing the Milwaukee Art Museums Calatrava-designed Addition

to a Boeing 747-400 Airplane:

Burke Brise Soleil wingspan 217 feet Boeing 747-400 wingspan 211 feet

Quadracci Pavilion length 293 feet Boeing 747-400 length 240 feet

Windhover Hall capacity 800; 500 if seated Boeing 747-400 capacity 416, not including crew

MAM total building weight 83 million pounds Boeing 747400 weight 398,780 pounds

The Milwaukee Art Museums Calatrava-designed Addition Compared to other Famous Structures:

MAM structural mast length 198 feet Leaning Tower of Pisa height 185 feet

MAM mast lean angle 41.64 degrees Leaning Tower of Pisa lean angle 5.25 degrees

MAM suspension cable diameter 50 mm (approximately 2 inches) or 35 mm

Brooklyn Bridge suspension cable diameter 15 inches

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

26

(approximately 1-3/8 inch)

INTERVIEW WITH SANTIAGO CALATRAVA About Milwaukee Art Museums Pavilion

By Opera Progetto International Review of Contemporary Architecture (Excerpts are from magazine edition OP/O pp. 27- 53; interview took place in Zurich, Switzerland, September 3, 2001, between Umberto Trame and Santiago Calatrava.)

OP: Your sketches show very different solutions for the extension of the work and its location vis vis the pre-existing museum (Milwaukee Art Museum).

CALATRAVA: In fact, we had lots of doubts about the extension of the plan. Then I added a precise geometric definition that went way beyond the initial estimates The entire process lasted about a year, which led to definition of the design and then, two or three important elements were further refined. And maquettes were used to this purpose: a first, a second, and a third one. We were able to design the moveable roof, not originally in the plan, with general optimism. This design emerged fairly organically and with the combined efforts of the customer.

OP: How was your project influenced by the fact that the new pavilion is located near a building designed by an architect of the caliber of Eero Saarinen and is set in the unusual lakefront position?

CALATRAVA: I was quite aware of the difficulties involved in working opposite Saarinens buildingIt is a cruciform building in concrete, fairly heavy, with dramatic connotations there is a list of names of those who lost their lives in the war and therefore, it has very special meaning. So, I said to myself, how can I design this museum and still safeguard the relationship with the existing building? I tried to read the texture of the city, and used it as a benchmark. The building by Saarinen is located at the end of Mason Street. I walked about a city block away, then another block. Then I crossed Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukees most important thoroughfare, which bisects the city from east to west, and I put the bridge of the building-pavilion on its axis. It lies about one hundred meters from Milwaukee, about the same distance between the axis of my building and Saarinens. I introduced a low building (seven meters high on average) connected to the foundation of Saarinens building and the one by Kahler. I intentionally designed a low building so that the view of the park would be left unobstructed. I also wanted the horizon and the lake to still be visible. I wanted the pavilion to complement Saarinens building as much as possible, and tried to establish a sort of parallelism, but at the same time I wanted to avoid mimicry. In fact, the War Memorial is a concrete building, while the new pavilion is entirely constructed in a glass and steel structure and can open. If the former is a building suspended in the air by supports, the letter is quite the opposite, bound to the earth.

OP: Lets talk about this aspect of the construction. It surely emerges from the design, from the idea that you aimed to express with this sort of project, but it also requires perfect execution, without errors or modifications. As we know that frequently solutions made on site can modify the initial program.

CATATRAVA: I had proposed to make the structural elements in concrete (practically 90% of all structural elements), cast on siteit entailed working with very sophisticated moulds that required extremely high concentration and great care in order to achieve a qualitatively high result.

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

27

There were shapes that crossed, horizontal lines along the walls that followed a rhythm seeking modulation. With one module, we obtained one height, with a double mould we obtained the height of one step, with a quadruple mould we obtained the height of the external lines and so forth. T-shaped forms were also used. Then there was the issue of the proportion of concrete to steel. The building is supported almost entirely on a single point under the car park, and there, there are large iron joints. On the first floor, the arches reverse their direction and there too, there are iron joints. Therefore, there is rhetoric in the way to guide the forces, in the way to make the transitions between the arches and the lateral walls, from the lateral walls through the slab up to the final central element, and from the central element to the foundation. There is an entire rhetoric that stems from using reinforced concrete and steel. Then we have two independent elements that are exclusively in steel: the roof covering the reception hall and the suspension bridge. The bridge is a steel structure with a steel mast anchored in the rear according to a precise geometry of cables fastened to a reinforced concrete structure. This geometry in the cables is echoed in the geometry of the great roof on the reception hall. Therefore they are coherent geometries because they share the same origin, only that one lies on one side and the other is on the other; one is somewhat flatter and the other is a bit longer. However, when you look at them in the longitudinal sense, they overlap and cover each other. Two vastly different elements like the stayed bridge and the roof communicate with each other through that fact that they belong to the same geometric family. This could have been accomplished in many ways, for instance, by using a similar color, but I thought the result would be more effective if they shared geometry. Aside from the very large overhanging portions that we have to the south and east of the entrance hall, the rest of the building is very serene and quite peaceful from the outside. By contract, the interior of the museum is fairly dynamic. I designed the inside in concrete and the outside in steel. The ceiling in the reception hall has a sort of covering made with steel fins that rise up 32 and a half meters, from the iron joints to the peak, and open mechanically. While they have structural character, they speak in a sculptors language. In constructing the sail, I forewent the use of reinforced concrete even though in the past we had created moving shapes in concreteI mean to say we could have built the sail in concrete, but we deliberately built it in steel in order to use concrete exclusively for the interior spaces. We used the less expensive grey concrete instead of the white variety, which is not even produced in the United States. Then we cured it and painted it white

OP: Lets talk more about this building, so tied as you say to the nature and feel of the place, and examine some aspects of the composition of the internal space of the building. I noticed that the layout of the pavilion is very elementary

CALATRAVA: Very, very simple...the best projects always have simple layouts.

OP:And yet the section is particularly complex. As you mentioned earlier, some structural aspects interact with this complexity while others are more functional.

CALATRAVA: Ive come to the conclusion that it is better to do simple layouts. In my mind, the order comes from the layout in the respect for clarity of circulation, orientation, and the logic between the spacesI made a tremendous effort to simplify things as much as possible in the layout. And also in Milwaukee I wanted the purity of the layout to be left uncontaminated

The entrance hall has a roof of glass and steel and above that there are ribs that give a complementary protection to the interior against sunlight. These are a sort of brise soleil,

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

28

a half functional and half sculpture element in which I used my research work as sculptor along with the architectural experience required to make these ribs open.

ARCHITECT SANTIAGO CALTRAVAS STATEMENT ABOUT THE MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM PAVILION

For me, the project of expanding the Milwaukee Art Museum was an opportunity to help people make the most of an extraordinary situation. They had the institution, first of all, with its dramatic, original building by Eero Saarinen, which is very strong, and whose integrity had been preserved by David Kahlers understated extension. They had the topography of the city, which descends to Lake Michigan from hilltop terraces. And of course, they had the whole sweep of the shore, looking out as far as the horizon. These were the invaluable assets that the people of Milwaukee entrusted to me. And they offered me something else as well, which is absolutely crucial for any architect. In the trustees of the Milwaukee Art Museum, I had clients who truly wanted from me the best architecture that I could do. Their ambition was to create something special for their community. So the design did not result from a sketch. It came out of a close collaboration with the clients, who enthusiastically accepted the key idea that emerged from our discussions. Instead of adding something more to the Saarinen building, I proposed to add something to the lakefront. The extension, as such, is a kind of pavilion, transparent and light, which contrasts with the massive, compact Saarinen building. Reaching out from the Quadracci Pavilion, like an arm extended to the city, is a bridge. I thought this design might establish a pattern

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

29

of events for possible future additions; a bridge to the city, and a very shallow pavilion that interrupts the view of the lake as little as possible. Besides being a link to the city, the bridge is a part of a composition. Its leaning mast conveys a sense of direction, of movement, which is taken up by the roof, the cables, and the canopies that extend on each side. These strong lines culminate in the Burke Brise-Soleil, which translates their dynamism into actual motion. In the crowning element of the brise-soleil, the buildings form is at once formal (completing the composition), functional (controlling the level of light), symbolic (opening to welcome visitors), and iconic (creating a memorable image for the Museum and the city). It is because of the strong encouragement and support of the Milwaukee Art Museum that the building has taken shape as it did. Thanks to them, I was able to give my best. Thanks to them, the magnificent landscape architect Dan Kiley has designed the beautiful plaza in front of the Quadracci Pavilion. Thanks to them, this project responds to the culture of the lake: the sailboats, the weather, the sense of motion and change. I hope that when the new Milwaukee Art Museum opens and people see its realized form, that they will feel we have designed not a building, but a piece of the city. -- Santiago Calatrava, ca. 2000

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

30

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

31

Calatrava and the Dream Machine School Program

Visit Descriptions and Information

PROGRAM SUMMARY The Milwaukee Art Museums and Discovery World at Pier Wisconsins Santiago Calatrava and the Dream Machine collaborative school program provides students in grades 68 an opportunity to learn about the creative design process combining art, science, and technology. This program includes a one-hour docent-guided Calatrava tour at the Milwaukee Art Museum and a one-hour hands-on experience in Discovery Worlds Rockwell Automation Dream Machine exhibition and Prototyping Lab. Using the work of Santiago Calatrava at the Milwaukee Art Museum, students explore Calatravas innovation and the creative design process from the idea through the product. Using the interactive Rockwell Automation Dream Machine exhibition and

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

32

hands-on Prototyping Lab at Discovery World, the students continue to explore the creative design process through technology, including prototyping and industrial automation.

PROGRAM GOALS AND OBJECTIVES The primary goals of the Santiago Calatrava and the Dream Machine collaborative school program are:

To provide students in grades 68 with an opportunity to learn about the creative design process combining art, science, and technology.

To help students make personal and practical connections with the creative design process.

To engage students in discussions and the creative design process.

To raise an awareness about careers in art, architecture, engineering, science, and technology.

To help teachers use art, science, and technology with their existing classroom curricula to teach about the creative design process.

To utilize both the Milwaukee Art Museum and Discovery World at Pier Wisconsin as teaching resources.

The primary learning objectives of the school program are that students will:

Understand that innovation/creativity begins with an idea.

Identify basic steps of the creative design process, including: o defining the problem or goal o finding solutions and ideas o documentation of ideas o testing, reflecting, and refining ideas o production

Explore connections between Santiago Calatravas creative design process and their own creative design process.

Discuss the relationship of art, architecture, science, and technology.

Develop a basic understanding of prototyping and industrial automation.

Create a product prototype using science/technology.

Visit at Milwaukee Art Museum One-hour docent-guided Calatrava tour at the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Using the work of Santiago Calatrava at the Milwaukee Art Museum (Quadracci Pavilion and Reiman Pedestrain Bridge), students explore Calatravas innovation and the creative design process from the idea through the product.

Topics included in docent-guided tour: o Who is Santigo Calatrava? o Relationship between careers architect, engineer, artist o Calatravas creative design process for Quadracci Pavilion, from the idea

through the product including inspirations, concepts, two-dimensional images and plans, three-dimensional images and structures.

o Nature as model for architecture (biomimicry and morphology) o Calatravas inspirations from nature and use of elements and principles of

art in architecture o Function and aesthetics of architecture

After the Calatrava tour at the Milwaukee Art Museum,

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

33

students walk to Discovery World at Pier Wisconsin.

Visit at Discovery World at Pier Wisconsin

One-hour hands-on experience in Discovery Worlds Rockwell Automation Dream Machine exhibition and Prototyping Lab facilitated by Discovery World Staff

Using the interactive Rockwell Automation Dream Machine exhibition and hands-on Prototyping Lab at Discovery World, the students continue to explore the creative design process through technology, including prototyping and industrial automation.

Educational Objectives: Rockwell Automation Dream Machine Tour Students will:

will engage with CNC machines, sample cutters, as well as Discovery Worlds original Dream Machine to learn how technology can influence design and manufacturing.

investigate the practical application of three axes spatial mathematics as related to computer aided drafting (CAD).

learn how computer assisted design functions for the designer and the engineer.

explore analogue programming and investigate how it automates the manufacturing process.

investigate the practical applications of technologies explored in the exhibit and how they benefit the precision, efficiency, flexibility, and standardization in the manufacturing world.

Prototyping Project: Students will:

follow technical instructions to assemble a three-dimensional mechanical model from a two-dimensional template.

relate the use of the laser cutter to the fabrication of the tangible product they will take away with them.

explore the design process from conception to the final product by examining stages of product development specific to their final project.

Rockwell Automation Dream Machine exhibition Docent Presentation (20 minutes):

Introduction/Welcome/Overview Docent leads students through the Rockwell Automation exhibit area focusing on each of the following components:

o Lynde Bradley Exhibit Theme: Space and time (sensory devices) Focus: Presentation will feature an interactive demonstration of proximity sensing devices.

Exhibit detects presence of movement in the area

Display activation

Recognition and reaction to movement

Removal of stimulus=discontinues operation

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

34

Application of demonstrated technologies in industry o CNC Milling Machine

Theme: Organizing design into workable elements (X, Y, Z coordinates) Focus: Use of Computer Assisted Design (CAD) to translate ideas into code that can provide directions for machines to fabricate, assemble, and test usable products.

Demonstration of machine in use (Dream Machine Cloudburst Logo) o Explain the use of codes that create instructions based

upon tool position (X, Y) and depth (Z). o Sample Maker

Theme: Application of CNC technology Focus: Flexibility/economic savings afforded by CNC

technologies

Present Scenario: Client needs prototype cartons for customers and manufacturers of corrugated products companies. o Fitness for use concepts (size, strength, appearance,

durability)

o Expense of developing tools for high volume production- allows instead for prototypes (cheaper, flexible)

Demonstrate operation of machine o Using multiple tools o CAD information system o Flexibility of machine-other applications

o Dream Machine Theme: Pulling it all together Focus: History, applications, and function of the Dream Machine

Created by Rockwell Automation for Discovery World (one-of-a-kind)

Showcases all stages of the manufacturing process: o warehouse o production o distribution

Designed as educational piece rather than for high production output

Demonstration of technology: o Order entry process o Performance of individual components

Remstar storage Cognex camera and proximity sensing

devices (4) Robot controller Laser cutting device (CAD driven) Die cutter/die storage machine Pick N Place robot Conveyors Recognition and reporting Sensors Order entry and inventory evaluation

sensors

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

35

o Technological Advantages Theme: Technology and Practicality Focus: Explore how the use of technologies such as those in the

exhibit makes for better manufacturing operations.

Time and space efficiency

Repeatable performance

Interchangeability

Regional production

Precision control=higher quality Prototyping Project Educator Presentation (30 minutes):

Welcome/Introduction/Overview o Butterfly Assembly

Students will follow technical directions to assemble the butterfly project they will take home.

The Design Process

Students will learn that the design process is lengthy often resulting in numerous versions of the same design that work to improve function, efficiency, and aesthetic.

o Compare to the work of Calatrava and his many designs for the Milwaukee Art Museum expansion.

o Apply how this practice influences all areas of innovation and design.

Students will observe the design process of the butterfly project by comparing and contrasting early prototypes with the final project.

Calatrava Tour Implementation Ideas at Milwaukee Art Museum Gallery Teaching Aids

Santiago Calatravas Creative Design Process for the Milwaukee Art Museum binder of images: Calatravas watercolors, models, photomontages, and architectural drawings for the Museums addition

Pages from Santiago Calatravas Sketchbooks (various projects and ideas) binder

Santiago Calatrava, Nature, and Milwaukee Art Museum Architectural Features packet

Calatrava-designed Quadracci Pavilion Study worksheets and pencils/clipboards

For Discussion with Students Calatravas Design Process for the Milwaukee Art Museum

Using the Santiago Calatravas Creative Design Process for the Milwaukee Art Museum binder of images: Calatravas watercolors, models, photomontages, and architectural drawings for the Museums addition, discuss Calatravas creative design process with the students.

Summary of Calatravas Design Process for the Milwaukee Art Museum

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

36

o Look at nature for inspiration after viewing project site; sketches of natural objects and human forms

[2-dimensional] o Pencil sketches and watercolor drawings of architectural ideas

[2-dimensional] o Prototype/maquette scale model (white model) of proposed architectural idea

[3-dimensional] o Photomontage/computer-generated image of exterior architecture (color)

[2-dimensional] o Formal architectural drawings and mechanical plans

[2-dimensional] o Construction of full-scale building

[3-dimensional]

Santiago Calatrava said when describing the brise soleil that While they have a structural character, they speak in a sculptors language. What do you think Calatrava meant by this statement?

Calatrava has stated, The principles I follow are based on repetition. This reminds you of nature because nature often works in patterns. Have the students find examples of this in the architecture and discuss how the examples are reminiscent of nature. Consider having the students complete the Calatrava-designed Quadracci Pavilion Study worksheets and then discuss their responses as a group, connecting their responses to similar patterns found in nature.

Beyond function, architecture is about experiencing space and evoking feeling(s) within a space. What feeling(s) do you think Santiago Calatrava was trying to evoke from the pavilion? Have students list feeling and/or adjectives that describe the space and explain their word/feeling choices. What about the space or architecture makes you say that?

Nature as Model for Architectural Forms and Shapes When people build structures, they often use shapes and designs that are found in nature or are inspired by nature. Santiago Calatrava is an architect who uses forms in nature and the human body to inspire his buildings and other structures. Calatrava believes that nature offers architects many ideas. Folded hands, birds, eyes, trees, human body, flower blossoms, fish, bones, and the rest of the natural world all give Calatrava ideas for structures. The best designs, he thinks, develop from within, so that their form is matched to their function.

Calatrava stated, I approached this project [Milwaukee Art Museum addition] with nature as the teacher. I am always trying to learn from nature. Looking closely at the images of objects from nature, what shapes and forms do you see? Can you match each of them with an architectural component or feature of the Calatrava-designed Quadracci Pavilion that it may be an inspiration for its design? What other shapes and forms in nature do you think Calatrava used as inspiration for the pavilion and components of the pavilion?

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

37

Using Santiago Calatrava, Nature, and Milwaukee Art Museum Architectural Features packet, give each student or pair of students an image from nature and have them find the architectural feature with the pavilion that may be inspired by the natural object. Have students look on own, and then regroup to discuss findings. KEY OF IMAGES

Nature Image: Quadracci Pavilion Feature:

pigeon with wings spread human spine and rib cage fern frond compound

leaves butterfly wings compound leaves on a

branch

Burke Brise Soleil

wave on lake exterior view of each galleria

cliff swallow nests barnacle shell group

grouping of circular vents on upper walls near main entrance

leaves stink bug pine cone tulip single petal shape

looking up at vaulted, glass-enclosed, parabolic-shaped reception hall; outer edge shape

sea shell clam pattern of glass supports/grid of pavilion roof

line of trees with bending branches

supports along each galleria

geological cave entrance triangular supports along each gallerias exterior walls

Calatrava has stated, The principles I follow are based on repetition. This reminds you of nature because nature often works in patterns. Have the students find examples of this in the architecture and discuss how the examples are reminiscent of nature. Consider having the students complete the Calatrava-designed Quadracci Pavilion Study worksheets and then discuss their responses as a group, connecting their responses to similar patterns found in nature.

Calatravas projects are engaged with movement. They do this in two principle ways: first, through parts of the structure that serve functional needs by explicitly moving (unfolding, revolving, rising, or channeling) objects, people, and vehicles; and second, through parts of the structure that implicitly represent movement through their form and repetition of forms/shapes. Have the students discover explicit and implicit movement in the Calatrava-designed addition and discuss how each function within the building.

Calatrava has stated that his designs are based on morphology. Assist students with defining and discussing morphology and how Calatrava uses it in the pavilion. Consider including the following statement by Santiago Calatrava as

-

2008 Milwaukee Art Museum 700 N. Art Museum Drive, Milwaukee, WI 53202 www.mam.org

38

part of the discussion with regard to moving from nature/organic shapes/forms to geometrical shapes/forms.