Zero Reject and School Choice: Students With Disabilities in Texas? Charter Schools

-

Upload

mary-bailey -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of Zero Reject and School Choice: Students With Disabilities in Texas? Charter Schools

This article was downloaded by: [Northeastern University]On: 24 November 2014, At: 07:21Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Leadership and Policy in SchoolsPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/nlps20

Zero Reject and School Choice:Students With Disabilities inTexas’ Charter SchoolsMary Bailey EstesPublished online: 09 Aug 2010.

To cite this article: Mary Bailey Estes (2003) Zero Reject and School Choice: Students WithDisabilities in Texas’ Charter Schools, Leadership and Policy in Schools, 2:3, 213-235

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1076/lpos.2.3.213.16532

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information(the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor& Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warrantieswhatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purposeof the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are theopinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed byTaylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon andshould be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor andFrancis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands,costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever causedarising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of theuse of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes.Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expresslyforbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Leadership and Policy in Schools 1570-0763/03/0203-213$16.002003, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 213–235 # Swets & Zeitlinger

Zero Reject and School Choice: Students With Disabilitiesin Texas’ Charter Schools

Mary Bailey EstesUniversity of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA

ABSTRACT

In an effort to ‘‘raise the bar’’ of student achievement, educators and policymakers over the pastdecade have embraced the concept of school choice, and charter schools as a form of choicewithin the public sector. Envisioned as a tool for enhanced academic achievement throughinnovation and deregulation, charter schools are often small, offer distinctive curricula, andappeal to parents. Amidst the charter movement, however, lies the reality of students withdisabilities and federal disability law, mandating an appropriate education for all. This articlereviews the literature regarding the extent to which students with disabilities are accessingcharter schools nationwide, and then presents research assessing the extent of ‘‘zero reject’’ inTexas’ charter schools.

In an effort to improve what some perceived to be the failure of American

public schools, educators and policymakers during the past decade have

embraced the concept of school choice, a reform designed to ‘‘raise the bar’’

of student achievement. Freedom of educational choice, some argue, results in

increased achievement as a consequence of market style competition (Chubb

& Moe, 1990). One form of school choice that has been widely endorsed is

charter schools, and 40 states have adopted legislation aimed at the

establishment of these schools (The Center for Education Reform, 2003).

Viewed by some as combining the advantages of public and private

schooling (Finn, Bierlein, & Manno, 1996; Nathan, 1996), charter schools are

often small and may offer distinctive curricula. Parents appreciate smaller

student/teacher ratios, and observers report an unusual degree of parental

Address correspondence to: Prof. Mary Bailey Estes, 4808 Winding Oaks Court, Arlington, TX76016-1708, USA. Tel.: þ1-940-369-7219. Fax: þ1-940-565-4055. E-mail: [email protected]

Accepted for publication: May 22, 2003.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

involvement (Blakemore, 1998; Bomotti, Ginsberg, & Cobb, 1999; Carruthers,

1998; Nathan). State charter statutes provide for some degree of deregulation

in return for educational innovation and academic accountability (Carruthers;

Finn et al.; Nathan).

What prompted the emergence of these ‘‘boutique schools,’’ about which

some parents and educators are so pleased? A history of the school choice

movement reveals it arose as an indirect response to a cry for higher

achievement in the wake of A Nation at Risk (National Commission on

Excellence in Education, 1983) (see Estes, 2001; Hubley & Genys, 1998;

Nathan, 1996; National Education Association [NEA], 1998a; Rider, 1998).

Published by the U.S. Department of Education, this document precipitated

concern about the state of public education in this country like nothing since

the Soviets’ successful launch of Sputnik twenty-six years before (Bracey,

1994). Comparing American students’ test scores with those from other

nations, A Nation at Risk read, ‘‘Our once unchallenged preeminence in

commerce, industry, science and technological innovation is being overtaken

by competitors throughout the world,’’ (National Commission on Excellence

in Education, p. 5). That the research was questionable seemed ignored by the

media and many politicians (Albrecht, 1984; Bracey; Gardner, 1984; Guthrie

& Reed, 1991). Nevertheless, the years following its publication spawned

numerous reform efforts, among them, competency tests for teachers, stiffer

graduation requirements, extended school day/year, and criterion-referenced

tests designed to determine readiness for promotion and graduation (Cookson,

1994; Guthrie & Reed). Conservative politicians, noting the popularity of

private schools, proposed issuing tuition vouchers to parents, allowing them to

choose private education at public expense. Charter schools arose as a

compromise, offering parents another choice (Cookson; Finn et al., 1996;

Henig, 1999; Morken & Formicola, 1999; Nathan).

Perhaps because the reforms were aimed at higher standardized test scores,

advocates for students with disabilities were concerned that students with

special needs were overlooked, at least initially, by charter school proponents

(Szabo & Gerber, 1996; Ysseldyke, Lange, & Algozzine, 1992; Zollers &

Ramanathan, 1998). Indeed, Szabo and Gerber reported that in April 1995,

only four of twelve state charter laws mentioned special education or the

requirements of federal disability law. Other articles and policy documents

made mention of special education as a federal requirement, and that charter

schools were not to discriminate on any basis, including disability, and left it at

that (Ahearn, 1999; Rhim & McLaughlin, 1999). That same year, Finn et al.

214 MARY BAILEY ESTES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

(1996) wrote that charter school teachers were expected to meet the needs of

all students, that few specialized staff members were hired, and that few pull-

out programs were offered. In retrospect, students with special needs appear to

have been an afterthought to the school choice movement (Estes, 2001;

Ysseldyke et al., 1992).

Regardless of the significance of students with disabilities to the emergence

of school choice, legal analysts have reminded operators that no child with a

disability may be denied either freedom of choice, or the protections and

programs defined by federal disability law (Heubert, 1997; Hubley & Genys,

1998; McKinney & Mead, 1996). There is no question that charter schools are

subject to all of the mandates of the Individuals with Disabilities Education

Act (IDEA) and other disability statutes (Council for Exceptional Children

[CEC], 1999; Heubert, 1997; McKinney, 1998; L.F. Rothstein, 1999). The

principle of ‘‘zero reject’’ is a cornerstone of the IDEA, which, as Public Law

94–142, arose in 1975 in response to growing concerns that the right to an

education was denied to some due to their disabilities (Fiedler & Prasse, 1996;

Turnbull, Turnbull, Shank, Smith, & Leal, 2002).

The implementing regulations to the 1997 amendments to IDEA clearly state

that students with disabilities enrolled in charter schools retain all rights to a

free and appropriate public education (Section 300.312[b–d]). Have students

with disabilities received equal access to charter schools? In this article, I

review the literature regarding a potential for discrimination in charter schools

and some concerns of legal commentators. I then present the results of a study to

assess the degree to which students with special needs have been served in

public charter schools in Texas. Compliance with zero reject is evaluated, and

the disability categories of students are examined. Although the quality of

special education matters, the thrust of this article is zero reject. Therefore, the

provision of appropriate public education is not herein addressed.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Students With Disabilities in Charter SchoolsBefore examining the degree to which students with disabilities are accessing

charter schools, it is appropriate to ask if their parents are seeking such

educational options. According to the literature they are, and for many of the

same reasons as other parents (Carruthers, 1998; Lange & Lehr, 2000; L.F.

Rothstein, 1999), including characteristics of the school, underlying philosophy

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 215

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

of the charter, indicators of school success, and overall support for the unique

needs of students (Carruthers, 1998; Fiore, Harwell, Blackorby, & Finnigan,

2000). Also cited are school philosophy, discipline, and special education

service provision (Fiore et al.; Lange & Ysseldyke, 1998). When asked for

more than one reason, 64% of parents questioned by Lange and Ysseldyke

stated their child’s educational needs were better met in the school of choice;

41% were either unhappy with the former school or wanted their child to

attend the same school as friends and/or siblings; 38% felt the special

education teachers kept them ‘‘better informed’’ (p. 259); 36% were looking

for a ‘‘fresh start’’ for their child (p. 259); 33% found ‘‘more options in special

education programs’ (p. 259); and 33% preferred the teachers in the choice

school. Fiore et al. found that class and school size, staff, academics, school

safety, and a ‘‘fresh start’’ (p. 18) were important to parents.

Are the doors to charter schools opening to students with disabilities? To

answer this question I turned once again to the existing literature base. If

students with disabilities face discrimination when attempting to access

choice, I reasoned, then fewer students with disabilities will be found in

charter schools than traditional public schools. This appears to be the case.

Even when including schools designed for students with specific disabilities,

data from the US Department of Education (2000) reveals that an average 3%

fewer students with disabilities attended charter schools than all public

schools combined during 1998–99 (8% versus 11%). The percentage was

within 5% in most states. Ohio, an exception, enrolled 5% more students with

disabilities in charter schools, and Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Louisiana,

Michigan, and New Jersey enrolled at least 5% fewer (US Department of

Education).

Average figures may mask the reality within individual schools, however.

The National Education Association (NEA) (1998b) reported that in 1997 a

quarter of all newly organized California charter schools enrolled no students

requiring special services, and well established ‘‘conversion’’ charters, once

operated as private schools, enrolled only 6% students with special needs.

Similarly in Arizona, during 1995–96 only 17 of 46 charter schools served

students with disabilities, and 262 of nearly 7,000 charter students were

enrolled in special education. In Massachusetts, 50% of charter schools had no

students with special needs during the 1995–96 academic year (NEA).

Henig (1999) wrote that in 1997, 7% of charter school students received

special education services compared with 10% nationwide, despite a roughly

proportionate number from low socioeconomic backgrounds. In only two

216 MARY BAILEY ESTES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

states, Minnesota and Wisconsin, did charter schools serve a proportionate

number of students with disabilities, and these two states supported a number

of schools designed for students with specific disabilities (Henig; Research,

Policy, & Practice International, 1997). Likewise, Estes (2000), reported that

of 3700 students attending 17 charter schools in northern Texas during 1998–

1999, slightly more than 7% had special needs, compared with approximately

12% in traditional public schools (Estes, 2001).

Expertise?A study conducted by the Education Commission of the States (1995) found

that charter school directors in seven states felt unprepared to accept the

challenges of students with disabilities. This finding has been echoed by

other researchers (Estes, 2000; Glascock, Robertson, & Coleman, 1997; L.F.

Rothstein, 1999; McLaughlin & Henderson, 1998; Rider, 1998; Vanourek,

Manno, Finn, & Bierlein, 1997; Vernal, 1995). Specific concerns mentioned

included numbers of students served, funding, and responsibility for providing

services. Grutzik (1997) noted a lack of familiarity with special education

forms and procedures. The US Department of Education (1998) reported that

relatively few charter school operators were trained educational adminis-

trators, precipitating concern that relatively few charter school directors were

‘‘conversant with the requirements of IDEA or other federal disability law’’

(p. 2). Vernal expressed concern that charter school administrators were

unfamiliar with the rules of special education funding, and unaware of the

procedures and costs of testing and evaluation. Blanchette (1997) wrote that

the technical skills necessary to implementing the IDEA are not trivial, and

states must provide sufficient assistance.

Expense?Requirements of disability law may tax young, free-standing charter schools

already facing financial difficulty. Charter schools in Texas have no designated

capital funds and cannot assess taxes (C. Ausbrooks, personal communication,

February 1999; Taebel et al., 1998). Building acquisition and restoration, as

well as other start-up costs, can be particularly burdensome (Hill, 1999).

Texas’ open enrollment charter schools operate as independent LEAs, and as

such are fully responsible for all services provided by the larger, more

experienced school districts. If students with special needs are to be provided

appropriate services, increased funding may be necessary (McKinney, 1998;

L.F. Rothstein, 1999).

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 217

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

Discriminatory Practices?Since the movement’s infancy, legal analysts have expressed concern for the

mandates of federal disability law in the context of school choice. McKinney

(1993) expressed fear that students with disabilities would face discrimination

as they sought choice. McKinney and Mead (1996) recommended that schools

(a) ensure their plans do not categorically exclude students with disabilities,

(b) recognize the continuing obligation to provide a free, appropriate public

education (FAPE), (c) design child-centered programs consistent with FAPE,

(d) maximize equity within choice, (e) determine which special education

accommodations can or cannot be effectively provided on site and make

arrangements for all, and (f) ensure that choice procedures in no way

contaminate the procedural safeguards of the IDEA.

Heubert (1997) reported that in two respects autonomous public charter

schools, such as those in Texas, may ‘‘paradoxically have greater obligations

than most traditional public schools to serve students with disabilities’’ (p.

303). Heubert asserted that since charter schools are often distinctive, they

cannot deny admission without denying the right to a distinctive education.

For example, a school offering cosmetology that denies entrance to a student

with a disability denies that student training in cosmetology. In Heubert’s

words, ‘‘Precisely because these schools are distinctive, however – and

because students with disabilities would not be similarly educated if assigned

to different schools – those who operate charter schools and other unusual

educational programs have a greater duty than traditional public schools to

admit and serve students with disabilities’’ (p. 331).

Zollers and Ramanathan (1998) reported that charter schools run on a

‘‘for-profit’’ basis (p. 299; see also Bulman & Kirp, 1999, p. 580) serve far

fewer students with significant disabilities than do local school districts.

Zollers (2000) noted two methods used by schools to exclude students with

disabilities. First, some who gain admission by lottery are barred once

their disabilities are discovered; and second, some are returned to their

former districts after admission because the charter school declares it has

no suitable program for them. Some writers have expressed concern that

schools may be ‘‘counseling out’’ students with challenging needs by

suggesting to parents that the children would be better served elsewhere (R.

Rothstein, 1998; Silver, 1998; Zollers). Students with disabilities can be

expensive to educate yet, ‘‘Parents of students with complicated disabilities

should not need another IDEA to give them a choice in public education’’

(p. 304), wrote Zollers and Ramanathan. R. Rothstein reported that charter

218 MARY BAILEY ESTES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

schools may effectively limit special education obligations with recruitment

and counseling procedures that formally meet requirements but discourage

enrollment of students with Individualized Education Programs (IEP).

McKinney (1998) called such counseling measures ‘‘clearly inappropriate’’

(p. 571).

Students With Behavioral DisordersParticularly troubling are clauses within state educational statutes that allow

charter schools to exclude students with a history of behavior problems. The

Texas Education Code (TEC), for example, enables charter directors to

exclude students with a ‘‘documented history of criminal offense, juvenile

court adjudication, or discipline problems under Chapter 37, Subchapter A’’

(State Board of Education, 1999). Disciplinary offenses delineated under

Chapter 37 of the TEC involve known violations of the local education

agency’s (LEA) student code of conduct, and may vary widely between school

districts.

Do such clauses discriminate against students with emotional and/or

behavioral disorders (E/BD)? Do charter school directors realize that

‘‘discipline problems under TEC’’ may indicate emotional disorders? Are

charter directors aware that the IDEA holds schools responsible for providing

disciplinary protections to students for whom there is a documented indication

of a possible disability, with or without a diagnosis (20 U.S.C. section1415

[k][8][B])? Because federal law overrides state statute, schools that screen out

applicants with a history of behavioral problems, or expel students for

disciplinary incidents, may be acting illegally. This, however, has yet to be

tested in court (L.F. Rothstein, 1999).

Texas and the Charter School MovementTexas’ charter statute, the nation’s nineteenth strongest according to the

Center for Education Reform (2003), was adopted in 1995 and enthusiasti-

cally endorsed by then Governor George W. Bush. The first 20 schools opened

during 1996–97, and by August of 2001, 180 charters were operational

(Charter School Resource Center of Texas, 2001). Although Texas law grants

charters to four types of sponsoring entities, the ‘‘vast majority’’ (Charter

School Resource Center of Texas, p. 4; F. Kemerer, personal communication,

June, 1999) have gone to tax-exempt non-profit corporations. Texas’ open

enrollment charter schools operate as independent LEAs, and as such are fully

responsible for all of the services provided by the larger, more experienced

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 219

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

school districts. Unlike other LEAs, however, charter boards have no power to

collect taxes or exercise the right of eminent domain, and they receive no

capital funds from the state (C. Ausbrooks, personal communication, February

1999; Charter School Resource Center of Texas; Taebel et al., 1998).

Although newly organized schools are eligible for federal funds from the

Charter School Expansion Act of 1998, state funds are allocated in the same

manner as to other public schools (N. Rainey, Texas Education Agency

[TEA], personal communication, January, 2002). Special education funds are

derived from two sources, (a) IDEA Part B funds, based on a formula that

provides for a base amount, with additional funds available based ‘‘85% on

total school population and 15% on students in poverty’’ within that

population. Approximately $1,000 per child with a disability has been

procured under this Part B formula grant. State funds provide another source

of special education funds, and are computed from a formula that considers

average daily attendance, special education instructional arrangement, an

average contact hour factor ‘‘related to time spent in special education which

is part of a full time equivalent student (FTE) calculation,’’ and a weighting

factor applied to the FTEs for various instructional arrangements (L. Taylor,

TEA, personal communication, January, 2003). Per pupil funds are

automatically allotted to schools that report the enrollment of students with

disabilities; however, more funds are provided to schools whose students

spend the day in inclusive environments than to those whose students attend

separate classes (C. Dietrich, TEA, personal communication, January, 2002;

L. Taylor, personal communication, January, 2003).

METHOD

It was felt that a logical first step to determining compliance with zero reject

was to compare numbers of students with disabilities enrolled in both public

school formats. As the literature revealed on a national level, I hypothesized

that in Texas fewer students with disabilities would be found among the ranks

of charter school students. If this proved to be the case, it was my intent to

pursue reasons for the discrepancy with qualitative interviews. I was also

interested in determining which disability categories were represented in the

charter enrollment. I gathered two types of data: (a) descriptive statistics

garnered from a state database, and (b) qualitative data derived from in-depth

interviews.

220 MARY BAILEY ESTES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

Quantitative Data CollectionI turned to the database of Texas’ Public Education Information Management

System (PEIMS) to determine the extent of charter school service to students

with disabilities. PEIMS is utilized by the state of Texas to collect all of the

information necessary for the legislature and the TEA to ‘‘perform their

legally authorized functions in overseeing public education’’ (TEA, 2000a,

p. 1). All local school districts and public charter schools are required to

submit data concerning student demographics, academic performance,

personnel, finances, and organization to PEIMS (TEA).

I used data from PEIMS to calculate (a) the percentage of students with

disabilities attending public charter schools in Texas, and (b) to determine the

types of disabilities ascribed to those students. For the purposes of the study,

the charter school data were limited to the 142 schools active in 1999–2000.

The Texas state educational agency makes no distinction between autonomous

charter schools and independent school districts, considering each an LEA

(TEC, Section 12.1005[b]; TEA, 1998). Therefore, the information requested

was supplied for all public schools. The two reports retrieved included, (a)

Texas Public School Districts including Charter Schools, Disabled Students

Receiving Special Education Services by Disability and Age, Fall 1999–2000

PEIMS Data, and (b) Texas Public School Districts Including Charter

Schools, Student Enrollment by Grade, Sex, and Ethnicity, Fall 1999–2000

PEIMS Data. The figures were current as reported to TEA on December 1,

1999.

Qualitative Data Collection

Participants

Qualitative procedures were used to verify the quantitative findings and

identify reasons for the results. The publication, Texas School Directory:

Active Charter Schools (TEA, 2000b) was consulted for the purpose of

identifying and locating potential charter school administrators to interview.

Administrators were selected based on the location of their schools (rural vs.

urban), the composition of their student bodies, their proximity to the

researcher, and their willingness to participate. Those selected were initially

contacted by telephone, at which time the study was described, the subjects

were assured of anonymity, and the interview sessions were scheduled. The

participants signed a research consent form prior to commencement of the

session. Six interviews were conducted, one with two individuals, for a total of

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 221

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

seven administrators. Although seven participants is a small sample, the

nature of qualitative research involves deriving in-depth information from a

small number of subjects (Silverman, 2001). Because some interviewees were

responsible for more than one school, 21 separate campuses were represented.

All of the schools were located within Texas, the majority (17) within

Education Service Center Regions X and XI. These two service centers

provided resources and training for all public schools within the 18 counties

incorporating and surrounding the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex.

The individuals selected reflected the diverse array of area charter schools.

The first five interviews were with (a) an administrator of a middle school with

two campuses, one in an upwardly mobile, predominantly white neighbor-

hood, the other in a racially/ethnically diverse urban locale, (b) an adminis-

trator of a K-12 conversion school serving white children, predominantly,

from upper income homes, (c) a rural PreK-10 school with a racially diverse

student body, (c) a secondary ‘‘drop-out recovery’’ school on two campuses

with students from lower middle to middle income ‘‘working class’’ homes,

and (d) a school in an inner city neighborhood with a student body that was

94% African-American and 6% Hispanic. The sixth interview was with the

special education director of a non-profit charter school corporation that ran

14 schools in a variety of settings, including a Montessori preschool, three

hospital schools, ‘‘several’’ schools affiliated with churches, and ‘‘several’’

secondary (8–12) drop-out recovery schools. Her schools ranged in enrollment

from 10–20 students to over 200. All of the drop-out recovery schools provided

students with individualized, self-paced work packets designed for course

completion, and thus credit toward high school graduation.

Several of the schools were chartered as ‘‘at-risk,’’ meaning that at least

75% of their students were classified ‘‘at-risk of dropping out of school,’’

according to the TEC, Chapter 29, Subchapter C (TEA, 1998). All of the at-

risk schools were racially diverse. None of the schools were specifically

chartered to serve students with identified disabilities.

Interview Format

An open-ended, semi-structured interview was conducted that utilized

questions prepared in advance, yet allowed for new avenues of inquiry to

emerge (Gall, Borg, & Gall, 1996; Glesne, 1999; Mahoney, 1997). I

incorporated ‘‘depth probes’’ (Frey & Oishi, 1995; Glesne, p. 93; Mahoney)

into the discussion to maximize information collection. Designed to elicit rich

information, these include ‘‘Tell me more,’’ or ‘‘Anything else?’’ statements,

222 MARY BAILEY ESTES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

strategically timed silences, and questions arising from comments made by the

interviewees (Frey & Oishi; Glesne, p. 87). A copy of the interview guide is

included in the Appendix.

The interviews took place at the convenience of school personnel, and

lasted an average 1 hour and 30 minutes. Each session was audiotaped and

transcribed, and the accuracy of the data was verified by the respondents (see

Gall, Borg, & Gall, 1996; Glesne, 1999). Two participants requested changes

to their transcripts.

RESULTS

Quantitative

Extent of Service

In order to calculate the percentage of students with disabilities served, I

determined the statewide charter school enrollment, and then sought the

numbers of students with disabilities making up that enrollment. I was

surprised to discover that acquiring precise data was not possible because (a)

50 charter schools, or 35.21%, did not report numbers of special education

students served during the academic year 1999–2000 (T. Hitchcock, TEA,

personal communication, September 12, 2000), and (b) it is the policy of TEA

to withhold exact numbers below five to ensure student confidentiality. An

accurate determination of special education enrollment, even within those

schools reporting, proved particularly problematic, therefore, because a

number of the schools were small (<100) and enrolled fewer than 5 students

with disabilities. Given the data provided to TEA and subsequently to the

researcher, however, it was calculated that approximately 8.6% of the

students enrolled in Texas’ charter schools during 1999–2000 had identified

disabilities. For purposes of comparison, traditional public schools reported

12.3% of students with identified disabilities.

This figure (8.6%) is misleading unless the schools are examined

individually. Of 142 charter schools operating within the state of Texas

during 1999–2000, 92 reported the enrollment of special education students.

Of those 92, 19 served fewer than five students with disabilities. A small

number of schools with unusually large numbers, therefore, skewed the mean

percentage. For example, the enrollment of students with disabilities in five

charter schools in the state was reported to be above 65%, with one school

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 223

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

designed for students with hearing impairments reporting that 87.2% had

disabilities. Of those schools submitting data, 47.6% (20 schools) reported

fewer than 5% students with disabilities, and 6.5% (6 schools) reported fewer

than 2%. If one were to assume that the 50 schools reporting no special

education data served no special education students during 1999–2000, one

might conclude that in 49.3% of charter schools in Texas, fewer than 5% of

students received services. Because funding is based on numbers of students

enrolled, those schools that did not report students with disabilities received

no special education funds for the following year (L. Taylor, personal

communication, January, 2003).

Several schools within Education Service Center Regions X and XI

received no special education funds for the next year. This was pertinent

information because 17 schools studied by qualitative means were supported

by those two centers. The reports showed that 10 of 29 charter schools in those

regions submitted no special education data for 1999–2000, and 5 schools

served fewer than 5 students with disabilities. Based on submissions, it

appeared that only 3.6% of all students attending charter schools in these two

regions were students with disabilities.

Disability Categories

The failure of many schools to submit data, and the TEA policy masking

student counts under five, complicated interpretation by disability category, as

well. Examination of the data supplied, however, indicated that of those

charter schools reporting, more than 51% of the students with disabilities had

learning disabilities (LD), more than 19% were categorized as emotionally

disturbed (ED), and more than 4% had speech and/or language impairments.

The numbers of students with other disabilities were either not reported or not

released.

Qualitative

Discrimination?

The mean percentages as reported to PEIMS (i.e., 3.6% students with

disabilities regionally and 8.6% statewide), prompted concern that students

with special needs were turned away or counseled to go ‘‘elsewhere.’’ ‘‘Zero

reject,’’ according to Fiedler and Prasse (1996, p. 29), is a foundational precept

of the IDEA: an education cannot be denied on the basis of a disability. None

of the participants acknowledged their school turned students with disabilities

224 MARY BAILEY ESTES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

away. It is not enough to initially admit students, however, if one is not willing

to educate them. With that in mind, I analyzed the comments of the interview

subjects regarding three components of zero reject: (a) the school(s) accepted

all who wished to enroll regardless of disability, (b) the school(s) were

wheelchair accessible, and (c) the school(s) did not expel without providing

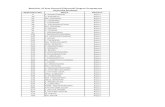

services. Table 1 illustrates the findings. (The issue of counseling out is not

considered in this analysis.)

Mild Disabilities

Students with disabilities were enrolled in all represented schools, and ranged

from 6.3% of the student population to 23% in the conversion charter (a

former private school for students with learning disabilities), for an average

11.6%. Typical of statewide figures, the administrators reported that the vast

majority of their special education students had learning disabilities. Other

categories included emotional disorders, speech impairments, and mild

mental retardation.

Moderate Disabilities

All participants verbalized a general willingness to admit all students;

however, one headmaster, a former public school administrator experienced

with students with Down Syndrome, stated he ‘‘didn’t know what he would

do’’ if the parents of a student with a moderate to severe mental impairment

wished to enroll their child. Most administrators asserted there was little

interest in charter schools among parents of students with significant

developmental needs. All of the schools utilized a full inclusion format, all

taught the general education curriculum, and none offered a continuum of

alternative placements. One director put it this way:

Special Ed. Director: [Parents of children with mental retardation] prefer a

more traditional setting where the services are already in place, and I’ve

found that trend in other charter schools, too, because there is just the

concern that we would not have that level of services.

Counseled Out?

The administrators described an interview process used to introduce

prospective parents and students to the programs offered. When asked to

explain this process, and whether it differs for students with disabilities, five of

seven asserted that they are ‘‘honest’’ with all of the parents, including those

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 225

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

Table 1. Comments Pertinent to Zero Reject in Texas Charter Schools.

Interview 1 Interview 2 Interview 3 ��Interview 4 Interview 5 Interview 6

Accepts all # X X X X X XWheelchair accessible X X �XNo expulsion without services X X X

Note. X Indicates the interviewee reported this to be the case in his/her school.�Indicates that one of the interviewee’s schools is not wheelchair accessible.# Indicates the administrator does not feel prepared to serve students with significant disabilities.��Indicates two respondents.

226

MA

RY

BA

ILE

YE

ST

ES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

of children with special needs. When asked to elaborate, they explained that

they tell parents what they offer, describe the programs, and relay some of the

advantages and disadvantages of their instructional model (full inclusion). The

enrollment decision is left to the parents. An actual response follows:

Researcher: Describe the interview process utilized with prospective

parents and students.

Special Ed. Director: What we always do is come in, and each parent is

interviewed, each family’s interviewed, and each family is oriented, and

that’s part of the situation . . . part of the whole enrollment process. They’re

all interviewed, told this is what we do, this is how we do it . . . is your child

going to fit here?

Another put it this way, ‘‘We tell the parents, ‘We will take your child, but

here’s what it is and this is what we do.’’’

Expulsion Without Services

It should be noted here that charter schools in Texas have ‘‘permission’’ to

deny enrollment to students with a history of behavior problems (TEC, Section

12.111[6]; TEA, 1998). Students were occasionally expelled if they failed to

keep an agreement to meet behavioral expectations, regardless of a ‘‘link’’

between the behavior and the disability. Because the IDEA requires that

schools provide disciplinary protections, including the continuation of

services, to students for whom there is documentation of a suspected

disability (34 C.F.R. Section 300.527 [b]), and because students with a history

of behavioral incidents may be exhibiting symptoms of emotional disorders,

serious questions are raised concerning the legality of this clause in the

Texas statute. One director described a typical behavior-related conference

thus:

Special Ed. Director: Now, we do have the option in the particular charter

that . . . we sit down and if this model is not working for them, we bring

the family in and say, ‘‘Look . . . the child is not doing . . .’’ Because

they’re [working] independent[ly] quite a good bit of the time, too.

There’s still rules, there’s still regulations, there’s still manners that have

to be followed. But, they have to be able to do independent work, and if

they are not succeeding with that we don’t want them to continue to fall

through the cracks. It may be that the more traditional setting is more

appropriate.

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 227

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

Accessibility

As Table 1 illustrates, three of the administrators oversaw schools that were not

wheelchair accessible. When asked, one minimized the importance of

accessibility, insisting that the law does not require accessibility to all portions

of the building. Two administrators acknowledged they were concerned about

accessibility. Most charter schools opened in buildings that were previously used

for other purposes. For example, one of the schools held classes in a renovated

house. Another was located in a small building that formerly held offices. Both

had classrooms that were small, somewhat crowded, and wheelchair inaccess-

ible. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires that schools allow for

wheelchair accessibility as renovations occur (28 C.F.R. Section 35.151 [b]).

Perhaps it is not required that all areas within schools be immediately

accessible, but a Texas special education hearing officer ruled in Jason L.v.

Seashore Learning Center Charter School of Corpus Christi, Texas, that the

rights of a ten-year-old student had been violated. Jason, a child with an

orthopedic impairment who used a wheelchair, was denied adaptive P. E. and

other educational programs as prescribed in his IEP, and was unable to access

the playground and certain campus buildings due to architectural barriers.

Evidence was presented that the school was in non-compliance with Title II of

the ADA and the IDEA. The hearing officer ordered Seashore Learning Center

Charter School to immediately remove all architectural barriers and

implement all special education services necessary to fulfill the IEP. The

school was also ordered to reimburse Jason’s parents for privately provided

services (Jason L.v. Seashore Learning Center Charter School, 1999).

SUMMARY AND IMPLICATIONS

The PEIMS data indicated that, as expected, fewer students with disabilities

attended Texas’ public charter schools during 1999–2000 (approximately

8.6%) than traditional public schools (12.3%). However, the average

percentage of students with disabilities attending the administrators’ schools,

11.6%, was almost 3% higher than the PEIMS data indicated, statewide. I

suggest the following explanations for the difference in enrollment figures: (a)

35.2% of Texas’ charter schools did not report special education numbers for

1999–2000 to the state, as requested, (b) data from schools with fewer than

five students with disabilities were not released, (c) at least three of the schools

represented in the interviews opened for the first time in the fall of 2000, and

228 MARY BAILEY ESTES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

(d) the average of students with disabilities in some of the schools was greater

than the average of charter schools statewide.

Fifty schools did not report special education numbers to the state. If

funding is tied to reported numbers, why would charter school directors be

hesitant to report students with special needs? One of the participants oversaw

one of those 50 schools, and hinted he hoped to avoid state oversight and the

‘‘bureaucratic red tape’’ associated with reporting. I wondered if his students

were denied the benefits of oversight, as well.

Why do traditional schools serve more students with disabilities? I can

speculate. Students with disabilities are expensive to educate, particularly if

they require instructional aides or self-contained settings. Several writers (e.g.,

Hill, 1999; McKinney, 1998; L.F. Rothstein, 1999) cited financial concerns.

One interviewee, an administrator of a school that was not designated ‘‘at-

risk,’’ questioned the ability of at-risk schools to remain open. In his words:

Headmaster: The ironic thing is that at the at-risk campuses . . . [and] we’re

underfunded . . . they’re putting little pockets of the most difficult,

expensive, difficult children to teach and then not funding them.

Researcher: They don’t get anymore money than you?

Headmaster: Not that I’m aware of.

Researcher: Right. I’m not, either.

Headmaster: So, the most expensive, challenging students to teach are now

being allowed to group together, and given no more money.

Another possibility is that some directors doubt their capacity to meet

students’ needs. A number of researchers have expressed concern about a lack

of expertise in disability law among charter school operators (e.g., Blanchette,

1997; Estes, 2000; Grutzik, 1997; McLaughlin & Henderson, 1998; L.F.

Rothstein, 1999). The Texas charter school statute does not require that

teachers be certified, or even college educated [Texas Education Code, Section

12.129, TEA, 2001]. One of the administrators told me he is hopeful his

‘‘Director of Special Education’’ will one day acquire a special education

certificate.

Another interviewee, one with expertise in disability law, worried that his

two campuses were not equipped to handle students with moderate to severe

impairments. The charter schools are less experienced with special educa-

tion and related services than traditional schools, which have had almost 30

years to practice. While most administrators expressed confidence in their

abilities and resources, there were no provisions in place for students for

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 229

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

whom the mainstream was inappropriate, and three schools were inaccessible.

As a result, some parents may prefer the special education programs available in

traditional schools.

Are parents discouraged from enrolling their children as a result of the

interview process? Perhaps. Several writers expressed concern that charter

schools ‘‘counsel students out’’ (e.g., McKinney, 1998; R. Rothstein, 1998;

Zollers, 2000). The schools studied utilized an interview process during which

parents were informed of programs, instructional format, and services. If

parents of students with disabilities desired that their children attend after

hearing an ‘‘honest’’ description of the programs offered, the schools accepted

those students. In their pursuit of an ‘‘honest’’ assessment of their services,

school personnel may consciously or unconsciously plant the seeds to suggest

that another choice is preferred for those with disabilities significant enough to

preclude success in the general curriculum. It should be remembered,

however, that the interview process did not preclude an average 11.6%

enrollment of students with special needs within the participants’ schools.

Do these findings have merit beyond these 20 Texas schools? Seven

participants constitute a small sample; however, Rubin and Rubin (1995)

wrote that the goal of such a study should not be generalizability, but rather

completeness [italics added], in which the work is continued until the

necessary information is obtained. ‘‘Sometimes interviewing one very well

informed person is all that is necessary . . . What is important is not how many

people you talked to, but whether the answer works’’ (p. 73). It is my opinion

that the answers I obtained pertinent to zero reject, a cornerstone of federal

law, are applicable to charter schools throughout the country.

Regardless, if school choice remains a viable option within public

education, there is no question that students with disabilities deserve, and

are legally entitled to, equal access. The 1975 passage of the original IDEA

brought about the public school education of throngs of children and youth

who had heretofore been excluded from the nation’s schools due to dis-

abilities. It is essential that we monitor our nation’s charter schools to ensure

that the spirit, as well as the letter, of the law is maintained.

REFERENCES

Ahearn, E.M. (1999). Charter schools and special education: A report on state policies.Alexandria, VA: Project FORUM at NASDSE.

Albrecht, J.E. (1984). A nation at risk: Another view. Phi Delta Kappan, 65, 684–685.

230 MARY BAILEY ESTES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101–336, 28 C.F.R. 35 (1992).Blakemore, C. (1998). A public school of your own: Your guide to creating and running a

charter school. Golden, CO: Adams-Pomeroy.Blanchette, C.M. (1997). Charter schools: Issues affecting access to federal funds. (Testimony

before the Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Youth and Families, Committee onEducation and the Workforce, House of Representatives.) Washington, DC: GeneralAccounting Office. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 414 620).

Bomotti, S., Ginsberg, R., & Cobb, B. (1999). Teachers in charter schools and traditionalschools: A comparative study. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 7. Retrieved June 12,2003, from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v7n22.html

Bracey, G.W. (1994). Transforming America’s schools: An Rx for getting past blame. Arlington,VA: American Association of School Administrators. (ERIC Document ReproductionService No. ED 383 095).

Bulman, R., & Kirp, D.L. (1999). From vouchers to charters: The shifting politics of schoolchoice. In S.D. Sugarman & F.R. Kemerer (Eds.), School choice and social controversy:Politics, policy and law (pp. 36–67). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Carruthers, S. (1998). The reasons parents of students with and without disabilities chooseColorado charter schools (Doctoral dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, 1998).Dissertation Abstracts International, 59, 257A.

Center for Education Reform. (2003). Charter schools in the United States. RetrievedSeptember 6, 2001, from http://www.edreform.com/charter�schools/map.htm

Charter School Resource Center of Texas. (2001). About CSRCT: Frequently askedquestions. San Antonio, TX: Author. Retrieved December 31, 2001, from http://www.charterstexas.org/about�csrct.php

Chubb, J.E., & Moe, T.M. (1990). Politics, markets, and America’s schools. Washington, DC:Brookings Institution.

Cookson, P.W. (1994). School choice: The struggle for the soul of American education. NewHaven, CT: Yale University Press.

Council for Exceptional Children. (1999). CEC speaks out on charter schools and specialeducation funding. CEC Today, 5, 10.

Education Commission of the States. (1995). Charter schools: What are they up to? A 1995 survey.Denver: Author. Retrieved August 12, 1999, from http://www.ecs.org/ecs/ecsweb.nsf

Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, Pub. L. No. 94–142 (1975).Estes, M.B. (2000). Charter schools and students with special needs: How well do they mix?

Education and Treatment of Children, 23, 369–381.Estes, M.B. (2001). Choice for all? Charter schools and students with disabilities. (Doctoral

dissertation, University of North Texas, 2001).Fiedler, C.R., & Prasse, D. P. (1996). Legal and ethical issues in the educational assessment and

programming for youth with emotional or behavioral disorders. In M.J. Breen & C.R.Fiedler (Eds.), Behavioral approach to assessment of youth with emotional/behavioraldisorders (pp. 23–79). Austin, TX: Pro-ed.

Finn, C.E., Jr., Bierlein, L.A., & Manno, B.V. (1996). Finding the right fit: America’s charterschools get started. The Brookings Review, 14, 18–21.

Fiore, T.A., Harwell, L.M., Blackorby, J., & Finnigan, K.S. (2000). Charter schools andstudents with disabilities: A national study. (Prepared for the Office of EducationalResearch and Improvement, U.S. Department of Education). Rockville, MD: Westat.(ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. 452 657)

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 231

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

Frey, J.H., & Oishi, S.M. (1995). The survey kit 4: How to conduct interviews by telephone andin person. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gall, M.D., Borg, W.R., & Gall, J.P. (1996). Educational research: An introduction (6th ed.).White Plains, NY: Longman.

Gardner, W.E. (1984). A nation at risk: Some critical comments. Journal of Teacher Education,35, 13–15.

Glascock, P.C., Robertson, M., & Coleman, C. (1997). Charter schools: A review of literatureand an assessment of perception. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of Mid-South Educational Research Association, Memphis, TN. (ERIC Document ReproductionService No. 416 041)

Glesne, C. (1999). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction (2nd ed.). New York:Longman.

Grutzik, C.F. (1997). Teachers’ work in charter schools: From policy to practice (Doctoraldissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1997). Dissertation AbstractsInternational, 58, 3078A.

Guthrie, J.W., & Reed, R.J. (1991). Educational administration and policy: Effective leadershipfor American education (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Henig, J.R. (1999). School choice outcomes. In S.D. Sugarman & F.R. Kemerer (Eds.), Schoolchoice and social controversy: Politics, policy and law (pp. 68–107). Washington, DC:Brookings Institution.

Heubert, J.P. (1997). Schools without rules? Charter schools, federal disability law, and theparadoxes of deregulation. Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 32,302–353.

Hill, P.T. (1999). The supply side of school choice. In S.D. Sugarman & F.R. Kemerer (Eds.),School choice and social controversy: Politics, policy and law (pp. 140–173).Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Hubley, N.A., & Genys, V.M. (1998). Charter schools: Implications under the IDEA.University Park, PA: Pennsylvania Education Policy Center, Penn State College ofEducation. Retrieved April 5, 2000, from http://www.psrn.org/charter.htm

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Amendments of 1997, Pub. L. No. 105-17 (1997).Jason L.v. Seashore Learning Center Charter School, Docket No. 075-SE-1098 (Texas 1999).Lange, C.M., & Lehr, C.A. (2000). Charter schools and students with disabilities: Parent

perceptions of reasons for transfer and satisfaction with services. Remedial and SpecialEducation, 21, 141–151.

Lange, C.M., & Ysseldyke, J.E. (1998). School choice policies and practices for students withdisabilities. Exceptional Children, 64, 255–270.

Mahoney, C. (1997). Common qualitative methods. In J. Frechtling & L. Sharp (Eds.), User-friendly handbook for mixed method evaluations. Rockville, MD: Westat. RetrievedAugust 25, 2000, from http://www.ehr.nsf.gov/EHR/REC/pubs/NSF97-153/CHAP�3.HTM

McKinney, J.R. (1993). Special education and parental choice: An oxymoron in the making.West’s Education Law Reporter, 76, 667–677.

McKinney, J.R. (1998). Charter schools’ legal responsibilities toward children with disabilities.West’s Education Law Reporter, 126, 565–576.

McKinney, J.R., & Mead, J.F. (1996). Law and policy in conflict: Including students withdisabilities in parental-choice programs. Educational Administration Quarterly, 32,107–141.

232 MARY BAILEY ESTES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

McLaughlin, M.J., & Henderson, K. (1998). Charter schools in Colorado and their responseto the education of students with disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 32,99–107.

Morken, H., & Formicola, J.R. (1999). The politics of school choice. Lanham, MD: Rowman &Littlefield.

Nathan, J. (1996). Charter schools: Creating hope and opportunity for American education.San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

National Commission on Excellence in Education. (1983). A nation at risk: the imperative foreducational reform. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved April14, 2000, from http: www.ed.gov/pubs/NatAtRisk/intro.html

National Education Association. (1998a). New roles, new rules? The professional work lives ofcharter school teachers. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved April 15, 2000, from http://www.nea.org/issues/charter/newrules.html

National Education Association. (1998b). Charter schools: A look at accountability.Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved May 23, 2000, from http://www.nea.org/issues/charter/accnt98.html

Research, Policy, and Practice International. (1997). A study of charter schools: First yearreport. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Rhim, L.M., & McLaughlin, M.J. (1999, March). Charter schools and special education:Balancing disparate visions. Paper presented at the 2nd Annual National Charter SchoolConference, Denver, CO. Retrieved March 23, 2000, from http://www.nasdse.org/Project%20Search/project� search� documents.htm

Rider, B.A. (1998). Establishing Texas charter schools: A policy study (Doctoral dissertation,Texas A&M University-Commerce, 1998). Dissertation Abstracts International, 60,126A.

Rothstein, L.F. (1999). School choice and students with disabilities. In S.D. Sugarman &F.R. Kemerer (Eds.), School choice and social controversy: Politics, policy and law(pp. 332–364). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Rothstein, R. (1998). Charter conundrum. The American Prospect, 39, 1–16.Rubin, H.J., & Rubin, I.S. (1995). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.Silver, K.O. (1998, November). Charting the course for special education in charter schools

How straight the course, turbulent the waters, and prepared the crew? Conversationsession presented at the annual meeting of the Teacher Education Division of TheCouncil for Exceptional Children, Irving, TX.

State Board of Education (SBOE). (1999). Open-enrollment charter guidelines andapplication: Application and procedures for applying for approval of an open-enrollment charter: Fourth generation. Austin, TX: Author.

Silverman, D. (2001). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analysing talk, text andinteraction ( 2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Szabo, J.N., & Gerber, M.M. (1996). Special education and the charter school movement. TheSpecial Education Leadership Review, 3, 135–148

Taebel, D., Barrett, E.J., Chaisson, S., Kemerer, F., Ausbrooks, C., Thomas, K., Clark, C.,Briggs, K.L., Parker, A., Weiher, G., Branham, D., Nielson, L., & Tedin, K. (1998). Texasopen-enrollment charter schools: Second year evaluation. A research report presented tothe Texas State Board of Education.

Texas Education Agency. (1998). Texas School Law Bulletin. Austin, TX: Author.

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 233

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

Texas Education Agency. (2000a). PEIMS: Public education information management system.Austin, TX: Author. Retrieved June 17, 2000, from http://www.tea.state.tx.us/peims/about.html

Texas Education Agency. (2000b). Texas school directory: Active charter schools. Austin, TX:Author. Retrieved June 17, 2000, from http://www.tea.state.tx.us/cd-rom/start/quickrpt/school/charsc/fmt/menu.htm

Texas Education Agency. (2001). Texas Education Code. Austin, TX: Author. RetrievedJanuary 16, 2003, from http://www.capitol.state.tx.us/statutes/ed/ed0001200.html#ed081.12.129

Turnbull, R., Turnbull, A., Shank, M., Smith, S., & Leal, D. (2002). Exceptional lives: Specialeducation in today’s schools (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

US Department of Education. (1998). Charter schools and students with disabilities: Review ofexisting data. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved May 19, 2000, from http://ed.gov/PDFDocs/chart�disab.pdf

US Department of Education. (2000). Students of charter schools: Students with disabilities.Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved May 23, 2000, from http://ed.gov/pubs/charter4thyear/c3.html

Vanourek, G., Manno, B.V., Finn, C.E., & Bierlein, L.A. (1997). The educational impact ofcharter schools: Charter schools in action, final report, Part V. Washington, DC: HudsonInstitute.

Vernal, S. (1995). Problems faced by existing charter schools. Education Policy AnalysisArchives, 3(13). Retrieved May 17, 2000, from http://olam.ed.asu.edu/epaa/v3n13/problems.html

Ysseldyke, J.E., Lange, C., & Algozzine, B. (1992). Public school choice: What about studentswith disabilities? Preventing School Failure, 36, 34–39.

Zollers, N.J. (2000, March 1). Schools need rules when it comes to students with disabilities.Education Week, pp. 46, 48.

Zollers, N.J., & Ramanathan, A.K. (1998). For-profit charter schools and students withdisabilities: The sordid side of the business of schooling. Phi Delta Kappan, 80,297–304.

234 MARY BAILEY ESTES

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014

APPENDIX

Interview Guide1. How would you describe the focus of your school?

2. For what purpose was your school chartered?

3. (a) Tell me about the composition of your student population (e.g., male/

female, at-risk, minority, gifted, disabled)?

4. Classify your students with disabilities according to disability category.

5. How well prepared do you feel your school is to serve students with mild

disabilities (in terms of facilities, personnel, resources)?

6. How prepared is your school to serve students with moderate to severe

disabilities (e.g., emotional/behavioral, mental retardation, or other dis-

ability that might necessitate a self-contained classroom)?

7. In what way does the nature of the student’s disability affect the

availability of service?

8. Describe the interview process utilized with prospective parents and

students.

9. Describe the way in which this process differs for families of students

with disabilities.

10. Tell me about the continuum of services provided by your school.

11. Are your schools wheelchair accessible?

12. What disciplinary methods do you normally employ, and do these differ

for students with disabilities?

13. Describe the process by which you request and receive special education

funds.

ZERO REJECT AND SCHOOL CHOICE IN TEXAS 235

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

07:

21 2

4 N

ovem

ber

2014