Youth4Job Case Study

Click here to load reader

description

Transcript of Youth4Job Case Study

“This publication is supported by the European Union Programme for Employment and Social Solidarity - PROGRESS (2007-2013). This programme is implemented by the European Com-mission. It was established to financially support the implementation of the objectives of the European Union in the employment, social affairs and equal opportunities area, and thereby contribute to the achievement of the Europe 2020 Strategy goals in these fields.The seven-year Programme targets all stakeholders who can help shape the development of appropriate and effective employment and social legislation and policies, across the EU-27, EFTA-EEA and EU candidate and pre-candidate countries.For more information see: http://ec.europa.eu/progressThe information contained in this publication does not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission”.

CASE STUDY

Job tendencies and vocational orientation and guidance in the ICT sector

“Youth4JOB” ProjectIdentification of Good Practices and Quality Services in terms of Vocational Orientation and Guidance for Young People

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 3

1 Introduction to the Case Study topic .................................................................................. 4

1.1 Situation in Slovakia ....................................................................................... 5

1.2 Situation in ICT sector ................................................................................... 6

2 Support Services to Youth Jobseekers .................................................................................. 7

2.1 Project on Regional development and employment – case study ..................... 8

2.2 InoPlaCe Project: Improving of Key Supporting Services for Young Innovators

across Central Europe – case study ........................................................................ 9

3 Labour Market Mechanisms ............................................................................................... 10

3.1 Skills supply in the ICT sector ........................................................................ 10

3.2 Skills mismatches in the ICT sector ................................................................ 11

4 Gender Issues ..................................................................................................................... 13

5 Skills Forecasting & Anticipation in ICT sector ................................................................. 14

5.1 Up skilling and the need for a non-technical and soft skills ............................. 15

5.2 Current and forecasted labour and skills demand in the ICT sector ................ 16

6 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 17

7 Conclusions ....................................................................................................................... 18

8 References .......................................................................................................................... 19

Table of Contents

3

The present case study describes the topic of the Job ten-dencies and vocational orientation and guidance in the ICT sector. Due to the topic of the Youth 4 Job project, special focus of the case study is given to the youth pop-ulation.

Statistics show that at the end of 2012 in average 22,8 % of young people in the European Union were un-employed. Hence, the EU is working to reduce youth unemployment and to increase the youth-employment rate in line with the wider EU target of achieving a 75% employment rate for the working-age population (20-64 years).

The ICT sector plays an important role in the economy in its own right and as a vital supplier to the private, pub-lic and third sectors and also an important jobs cradle. ICT sector companies and jobs are not evenly distributed across EU countries and regions. In absolute terms, the computer programming and consultancy sector is most developed in the United Kingdom and Germany repre-senting 37% of the entire EU workforce in the sector. However, relative to the total workforce, it is in Den-mark, Sweden and Ireland where the sector has the larg-est share of the entire workforce (2% or more) while in Bulgaria, Romania and Greece, the sector’s contribution to total employment is 0.5% or less.

Across the EU, the sector has experienced continuous growth. Between 2000 and 2011, the sector gained around 600,000 additional workers - a growth of 29 %. However, the trend across individual countries differs significantly, from substantial sector growth in Slovenia,

Slovakia and Portugal to zero growth in the UK, Roma-nia and Italy and a small decline in Denmark and Ice-land. Some countries have mature ICT sectors, whereas in others the sector has only recently developed.

There are important structural differences between coun-tries in relation to skills demand in the ICT sector. The demand for skills is likely to be stronger in those countries which are ‘lagging behind’ and where the economy is less mature in terms of the adoption and diffusion of ICT, and which therefore are expected to experience relatively greater growth in demand for computer programming, consultancy and related services. The computing services sector will continue to expand in the EU. Employment growth of 7.6% is forecast, from 3 million workers in the sector in 2010 to 3.2 million in 2020. Compared with the average of 3.4% employment growth forecast across all sectors, ICT will be one of the fastest growing sectors in Europe.

Reforming education systems and increasing digital skills learning opportunities will help prepare young Europe-ans for the jobs of both today and tomorrow.

Executive Summary

4

Statistics show that at the end of 2012 in average 22,8 % of young people in the European Union were unem-ployed.

Chart no 1: Unemployment rate of young under 25 years - annual average, %

GEO/TIME 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007

Austria 8,7 8,3 8,8 10,0 8,0 8,7

Bulgaria 28,1 25,0 21,8 15,1 11,9 14,1

Czech Republic 19,5 18,1 18,3 16,6 9,9 10,7

Germany 8,1 8,6 9,9 11,2 10,6 11,9

Euro area (16 countries)

23,1 20,8 20,9 20,2 16,0 15,5

Greece 55,3 44,4 32,9 25,8 22,1 22,9

Spain 53,2 46,4 41,6 37,8 24,6 18,2

European Union (27 countries)

22,8 21,4 21,1 20,1 15,8 15,7

Italy 35,3 29,1 27,8 25,4 21,3 20,3

Japan 8,1 8,2 9,3 9,1 7,3 7,7

Norway 8,6 8,7 9,2 9,2 7,3 7,2

Portugal 37,7 30,1 27,7 24,8 20,2 20,4

Slovenia 20,6 15,7 14,7 13,6 10,4 10,1

Slovakia 34,0 33,5 33,9 27,6 19,3 20,6

United Kingdom 21,0 21,1 19,6 19,1 15,0 14,3

United States 16,2 17,3 18,4 17,6 12,8 10,5

Source: Eurostat

Above presented, classic youth unemployment rates can create a distorted view of reality. For example, the pro-

portion of under qualified young people who are actually on the job market is far greater than it is in the entire population of 15- to 24-year-olds that includes students. Anyone who drops out of school at 14 gets statistically grouped into the workforce and they are likely to be un-employed.

Meanwhile, the best students often pursue their educa-tions the longest, during which time they remain left out of the data. Those who go on to earn a master’s degree or Ph.D. often don’t enter the labour force until they are past 25, which means they never even appear in the youth employment statistics. Thus, Eurostat has also made an alternative calculation that accounts for the entire young population by age brackets, including students which shown that the situation is slightly better. Chart no 2: Young people not in employment and not in any edu-cation and training, by age (NEET rates)

GEO AGE/TIME

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

European Union 27

15›24 10,9 10,9 12,4 12,8 12,9 13,2

European Union 27

15›19 6,5 6,5 7,0 7,0 6,9 7,0

European Union 27

15›29 13,2 13,1 14,8 15,2 15,4 15,9

European Union 27

20›24 15,2 15,0 17,5 18,0 18,2 18,6

European Union 27

25›29 17,3 17,0 19,0 19,7 19,8 20,6

Source: Eurostat

1 Introduction to the Case Study topic

5

According to the widely cited 2012 Euro found, there is considerable variation in the NEET rate between EU Member States, varying from below 7% (Luxembourg and the Netherlands) to over 17% (Bulgaria, Ireland, It-aly and Spain).

NEETs are a highly heterogeneous population. The larg-est subgroup tends to be those who are conventionally unemployed. Other vulnerable subgroups include sick and disabled persons and young carers, as well as dis-couraged workers and young people who are disengaged from society. Non-vulnerable subgroups include young people simply taking time out and those constructively engaged in other activities such as art, music and self-di-rected learning. Some young people are at greater risk of being NEET than others. Those with low levels of educa-tion are three times more likely to be NEET compared to those with tertiary education, while young people with an immigrant background are 70% more likely to become NEET than nationals. Young people suffering from some kind of disability or health issues are 40% more likely to be NEET than those in good health. Family background also has a crucial influence. Being a NEET has severe adverse consequences for the individual, society and the economy. Spending time as a NEET may lead to a wide range of social disadvantages, such as alienation, insecure and poor employment prospects, delinquency, and men-tal and physical health problems (Eurofound, 2012).

In 2011, the economic loss due to the disengagement of young people from the labour market in Europe was estimated to be €153 billion, corresponding to 1.2% of European gross domestic product (GDP). There is great variation between Member States, but some countries are paying an especially high price of 2% or more of their GDP: Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia and Poland (Eurofound, 2012).

1.1 Situation in Slovakia

Slovakia has one of the highest youth unemployment rates in the EU. Unemployment in Slovakia, including youth unemployment, is one of the highest. Among 15 to 24 year-olds, the percentage of people out of work, measured by the so-called Neither in Employment nor in Education or Training (NEET) rate, was 13.8% in 2012.

Using a different measure, the simple unemployment rate for this age group, Slovakia is currently in the third worst position in the EU, with 34.5%. Only Portugal (37.7%) and Spain (53.2%) are worse. These percent-ages are higher than in NEET figures, because they are calculated from a narrower base, of people available for employment, rather than the whole age group.

Slovakia had one of the highest youth unemployment rates in the EU even during the economic boom of 2005 - 2007, Therefore young people, especially those with el-ementary and secondary education, have been experienc-ing major difficulties finding a job. Yet, very few active labour market measures can be said to be targeted at this group.

In 2002, Slovakia enacted the Law on Employment Ser-vices, a state-financed framework for internships and ap-prenticeships. The intention was to guarantee the young unemployed some employment experience and to pre-vent them from working illegally. The mechanism is cur-rently used by employers mostly for temporary jobs and it is mostly viewed as a tool for preserving the working experience of the unemployed. Employers bear no la-bour costs for employing young people temporarily and the young unemployed are not bound by any working contract. This allows employers to rotate the young un-employed without creating real jobs. The state-sponsored internship scheme does have some positive effects, as it at least provides some work experience. However, similar to other internship programs, only a very low number of participants find a permanent job through this mecha-nism.

Slovakia´s experience, while still worse than others, is not dramatically different from the situation elsewhere. Young people have been encountering problems finding a job for a long time in the majority of EU member states. Internships, with a weak prospect of turning into a real job, are widespread in many older EU member states. It is estimated that in Great Britain only 9 percent of all interns stay at their position after the internship ends.

On contrary, in Austria and Finland, close cooperation with employers, the education system and job centres form the bedrock of the policy, and the long-term effect is ensured through a conceptual approach aimed at school-to-work transitions. The effects are visible in Eurostat figures. For example, Austria, with its 7% NEET rate, has one of the lowest numbers of young unemployed in the EU. Simply put, the efficiency of the Youth Guaran-tee is based on long-term cooperation with employers. If this cannot be ensured, the policy can lead to undesirable outcomes, such as a frequent turnover of the unemployed in internships or trainee programs with no real job pros-pects.

In Slovakia, with its rigid labour market policy, this dan-ger of creating too many temporary placements that do not lead to stable jobs is quite real. With a ready supply interns at low price, employers might even decrease the availability of regular jobs. The problem lies in the lack

6

of supportive measures that would help lock graduates in jobs by providing them with training, for example. According to the Law on Employment Services, young people are considered to be one of the disadvantaged groups on the labour market. This qualifies them to some support besides the internship scheme, such as addition-al training and education. However, the expenditures on education and training of the unemployed are persistent-ly one of the lowest in the EU.

The Youth Guarantee as proposed by the EU commission is not a bad policy. The question is whether the individual states will change the approach to labour market policy and improve the connectivity of labour market needs and education of school graduates, or whether it will, per-versely, lead dropouts and graduates into a long chain of internships. The example of Slovakia, where the govern-ment haven’t establish appropriate framework for school-to-work transitions even in the face of staggeringly high youth unemployment, is not encouraging.

Policy makers could use the momentum provided by the on-going discussion on the Youth Guarantee to pressure the weak-performing member states into a range of fur-ther labour market reforms.

1.2 Situation in ICT sector

The ICT sector plays an important role in the economy in its own right and as a vital supplier to the private, pub-lic and third sectors. As information and communication technologies have expanded across virtually all economic sectors, the boundaries of the sector are difficult to draw. National statistical definitions of the ICT sector differ. In some contexts, the ICT sector is viewed ‘as a com-bination of manufacturing and services industries that capture, transmit and display data and information elec-tronically’. ICT is among the leading sectors in Europe and affects economic growth across the economy in three ways:

1. For the EU as a whole, the ICT sector share of total business value added is 8.5 % and the ICT sector employment constitutes 3 % of total business sector employment in the EU.

2. The most important benefits of ICT arise from its effective use. ICT investments help to raise labour productivity.

3. The use of ICT throughout the value chain en-ables firms to increase their overall efficiency

and makes them more competitive.

Currently two relevant estimates of the number of ICT employees are available in Slovak Republic.

The first one refers to the selective determination of work force (further only VZPS), which is consequently applied to the most current demographical status at the time of determination. According to this estimate, the ICT sec-tor has 33,193 employees.

VZPS is based on a quarter-yearly determination of the situation in the labour area and the employment rate in households by means of a questionnaire. Regions of the SR, age groups and gender are taken into account. An employed person is such person who in the course of the monitored week worked for at least one remunerated hour. Employed people include the maternal/paternal care in business-persons’ households, who do not get any wage or remuneration for their activity, professional members of armed forces, as well the civil service. Em-ployed people are also persons who have a job but they are not working in the course of the monitored week be-cause of illness, vacation, a proper maternity leave, edu-cation training, bad weather, strike or closure, excluding persons on a long-term unpaid leave and persons on pa-rental leave. With regard to the limited sample of house-holds (10,250), this system of quantification brings a certain risk of inaccuracy. The parameters obtained using this method are also presented by Eurostat.

The second estimate of the employment rate in the sec-tor is based on Statistical Office data on the registered number of employees. The office acquires data on the ba-sis of the obligation of enterprises to submit statements on the number of employees. That is why this method is more accurate to a certain extent, but its success is influ-enced by insufficiencies in the statistics for units where the number of employees is estimated using selective de-termination.

Statistical Office data shows that the ICT sector had 33,193 employees in 2010 and 9,962 self-employed in 31.12.2009.

7

The EU is working to reduce youth unemployment and to increase the youth-employment rate in line with the wider EU target of achieving a 75% employment rate for the working-age population (20-64 years).

According to the European Commission - Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion - Youth employment depart-ment, there can be mentioned several reasons why the EU is tackling this issue:

· Youth unemployment rate is more than twice as high as the adult one – 23.3 % against 9.3 % in the fourth quarter of 2012.

· The chances for a young unemployed person of finding a job are low – only 29.7 % of those aged 15-24 and unemployed in 2010 found a job in 2011.

· When young people do work, their jobs tend to be less stable – in 2012, 42.0 % of young employ-ees were working on a temporary contract (four times as much as adults) and 32.0 % part-time (nearly twice the adults’ rate).

· Early leavers from education and training are a high-risk group – 55.5% of them are not em-ployed and within this group about 70% want to work.

· Resignation is an increasing concern – 12.6 % of inactive youth wanted to work but were not

searching for employment in the third quarter of 2012.

· In 2011, 12.9% of young people were neither in employment nor in education or training (NEETs).

· There are significant skills mismatches on Eu-rope’s labour market.

· Despite the crisis, there are over 2 million unfilled vacancies in the EU.

In December 2012, the European Commission proposed a package of measures to help deal with youth unemploy-ment.

Youth Employment Package (2012) is the follow-up to the actions on youth laid out in the wider Employment Package and includes:

· A proposal to Member States to establish a youth guarantee – agreed upon by the Employment and Social Policy Council (EPSCO) in February 2013

· Second-stage consultation of EU social partners on a quality framework for traineeships

· The announcement of a European Alliance for Apprenticeships and ways to reduce obstacles to mobility for young people.

2 Support Services to Youth Jobseekers

8

The Employment package (launched April 2012) is a set of policy documents looking into how EU employment policies intersect with a number of other policy areas in support of smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. It identifies the EU’s biggest job potential areas and the most effective ways for EU countries to create more jobs.

Youth Employment Initiative (2013) reinforces and accelerates measures outlined in the Youth Employment Package. It aims to support particularly young people not in education, employment or training in regions with a youth unemployment rate above 25 %. The Youth Em-ployment Initiative was proposed by the 7-8 February 2013 European Council with a budget of €6 billion for the period 2014-20.

Youth on the Move (to which aims also Youth4Job proj-ect) is a comprehensive package of policy initiatives on education and employment for young people in Europe:

· Youth Opportunities Initiative (2011) includes actions to drive down youth unemployment

· Your first EURES Job aims to help young people to fill job vacancies throughout the EU.

Moreover, EU Skills Panorama is EU-wide tool gather-ing information on skills needs, forecasting and develop-ments in the labour market.

Central to the Commission’s proposal is the Youth Guar-antee: a pledge underpinned by policy measures to pro-vide employment, continued education or training for people younger than 25 within four months of leaving formal education or becoming unemployed. It is up to the member states to choose the exact form of imple-menting this in practice.

Some countries already have schemes in place similar to the proposed Youth Guarantee. The Finnish and Austrian systems, in fact, partly served as an inspiration for the EU proposal. Similar measures can be found outside the continent as well. For example, New Zealand has started a Youth Guarantee Scheme in 2013. Nevertheless there remains an open question whether a guarantee can re-solve deep-seated labour market problems?

Moreover, the European commission’s recently an-nounced “opening up education” initiative is a step in the right direction. The initiative will integrate existing and new actions to promote the use of ICT and open ed-

ucational resources in education and training. “Opening up Education” will also be designed to address common challenges faced by several education sectors (schools, vo-cational and education training, higher education, adult education) and to support sectors as they address their own specific needs.

2.1 Project on Regional development and employment – case study

This project promotes cooperation between the vocational schools, employers’ organisations and industrial associations. The aim is to make vocational training more attractive and more responsive to the requirements of the Slovakian labour market. The project takes into account the experience of the Swiss dual educational system.

The main form of vocational training in Switzerland involves working in a company and taking courses in a vocational school. This is known as the dual educational system. Training is geared to the actual demand for voca-tional qualifications and to the jobs available. Thanks to this direct connection to the labour market, Switzerland has one of the lowest rates of youth unemployment in Europe.

Slovakia does not have a dual training system. Vocational training schools train apprentices in theory and practice but in some cases they do not know what Slovakian com-panies require from apprentices or how the labour mar-ket is developing. As a result, there are sometimes gaps between the skills acquired in training and the wishes of companies. This is a factor in the increase of youth unem-ployment, which totalled 34% at the end of 2012.

The Slovakian State Education Institute (SIOV) is re-sponsible for the project on the Slovakian side. On the Swiss side, the Federal Institute of Vocational Training (EHB) is participating in the project; 85% of the financ-ing of this project comes from the Swiss contribution to the reduction of economic and social disparities in the enlarged European Union.

The experiences of the EHB in the field of vocational training are crucially important for this project. The Swiss vocational schools and the Swiss system of vocational training as a whole are considered particularly good and in close touch with industry and with companies. This knowledge transfer will have positive long-term effects on the Slovakian vocational training system.

This project promotes greater and lasting cooperation between the main actors in the Slovakian education-

9

al system, especially between employers and vocational schools. This will enable the vocational training system to react more effectively to changes in demand on the la-bour market. This in turn will increase the employability of young Slovakian professionals, will make them more attractive to employers and in the long run will reduce youth unemployment.

2.2 InoPlaCe Project: Improving of Key Supporting Services for Young In-novators across Central Europe – case study

Young innovators are important potential driving force for the innovation in regions of Central Europe, but as the matter of fact their potential is used in very limited amount. It is also concerned that their needs for support is particularly the same as for other Innovators, particu-larly they faced specific issues according to their experi-ences, knowledge and social inclusion.

Project InoPlaCe is targeting the young innovators as one of the key driven forces of development, bringing to re-gions high innovations potential.

Project aims to improve their framework conditions by the following general objectives:

1. Develop transnational action plan for development and improvement of Key Services for Young Innovators.

2. Improve the access of Young Innovators to existing ser-vices which are supporting the innovations.

3. Develop and improve at least one service in each part-ner’s region with realization of Pilot Actions.

Project also developed the Regional Innovation Labs (RILs) which present a non-profit platform for direct in-volvement of young innovators into project activities. In every participating region RIL has min 20 members;

Benefits for participants:

· possibility to actively influence what services of what quality will be offered

· Involvement in the RIL brings space for network-ing

· The good practices identification and transfer

means the opportunity to make the grass equally green as it is behind the neighbour´s fence.

· The opportunity to introduce the needs to a broad audience including various stakeholders in the in-novation process (RTD institutes, universities…) and regional policy makers who shape the envi-ronment in which the young innovators operate.

· Broader perspective on the supporting services for young innovators outreaching their region

· Voluntary activity in the field of innovation and EU co-funded project may enhance the CVs of RIL members and their attractiveness for the em-ployers.

10

A large share of the ICT sector’s workforce is made up of ICT professionals whose tasks include consulting activi-ties and the design of ICT services, ICT development (in-cluding software and applications, systems development, web design, security, etc.) and running or delivering ICT services (user support, systems and network administra-tions, database management, etc.). It is important, how-ever, to distinguish between ICT professionals and the ICT sector. The ICT sector employs ICT professionals and a large number of non-ICT professionals across a range of roles, for example sales and marketing, admin-istrative, finance and human resources. Whilst the ICT sector remains the single largest sector employing ICT professionals, in the EU, 55% of ICT professionals work outside the core ICT sector (EU Skills Panorama Analyt-ical Highlight. 2012).

Around 2.7 million people in the EU worked in the ICT sector, in computer programming, consultancy and re-lated activities in 2011, accounting for 1.25% of the en-tire workforce. In 2009, the sector consisted of around 450,000 enterprises, many of which were micro enter-prises or small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs). The average number of employees per enterprise was 5,4.

ICT sector companies and jobs are not evenly distribut-ed across EU countries and regions. In absolute terms, the computer programming and consultancy sector is most developed in the United Kingdom and Germany accounting for one million jobs (representing 37% of the entire EU workforce in the sector). However, relative to the total workforce, it is in Denmark, Sweden and Ire-land where the sector has the largest share of the entire

workforce (2% or more) while in Bulgaria, Romania and Greece, the sector’s contribution to total employment is 0.5% or less.

ICT is a fast growing sector shaped by national specific development paths and global trends

3.1 Skills supply in the ICT sector

Levels of ICT skills interest and competence amongst young people provide an indication of the future poten-tial supply of skills for the ICT sector. Students’ access and use of ICT at school has improved since 2000. On average across OECD countries, the percentage of stu-dents who reported having a computer at home increased from 72% in 2000 to 94% in 2009. During the same pe-riod, Internet access at home grew from 45% to 89%, on average across the OECD. The vast majority of European countries show large increases in students’ self-confidence in being able to undertake high-level ICT tasks. Despite this improvement, a divide in the student access and use of ICT is evident between countries (EU Skills Panorama Analytical Highlight. 2012).

As graduates from science, technology, engineering, and math often move into the ICT sector, their availability is also important for the supply of future potential skills. The supply of tertiary education graduates with STEM skills varies significantly across the countries, with STEM graduates constituting around 11-12% of all graduates

3 Labour Market Mechanisms

11

in the UK, Germany, Greece and Ireland compared to around 5% in Latvia, Lithuania, Romania and Bulgar-ia. Importantly, however, across the EU, the number of tertiary education graduates in science, mathematics and computing fields has declined slightly in the 2006-2010 period, from 9.8% in 2006 to 9.1% in 2010. Coun-try-level trends are very different, with significant in-creases in the number of STEM graduates apparent in Malta and Slovenia (albeit from a rather low baseline) and Denmark and Germany, but significant decreases in Belgium, Ireland, Cyprus and Austria (EU Skills Panora-ma Analytical Highlight. 2012).

More directly, a large part of the future technical work-force in the ICT sector is also expected to come from the pool of computing graduates, especially at the tertiary level. However, the annual number of students graduat-ing in computing in the EU-27 has been declining over the last five years, following a peak in 2005-2006. Im-portant to note is the variation in the number of gradu-ates by ISCED levels:

· At Level 4 (Post-secondary non-tertiary education - pre-vocational and vocational programme orien-tation) and Level 5 (first stage of tertiary educa-tion) the numbers of graduates have declined in the last five years following a peak in 2005-2006;

· At Level 6 (second stage of tertiary education) the number of graduates has continued to increase throughout the last decade (from 1,839 graduates in 2011 to 3,468 graduates in 2010), although representing relatively low numbers.

3.2 Skills mismatches in the ICT sec-tor

ICT sector is facing issues with an insufficient supply of particular ICT graduates. The EU Skills Panorama Ana-lytical Highlight from 2012 demonstrated the situation in the following country examples:

· In the Czech Republic, the number of university graduates in informatics increased significantly between 2005-2010, and is expected to remain at around 1,100-1,200 graduates per year to 2016. In contrast, the demand for ICT sector workers is expected to grow by 31% in the 2010-2020 period (from around 56,000 workers in 2010 to around 73,000 workers in 2020), significantly above the average 2% growth in employment ex-pected across all sectors.

· In Ireland, a significant gap is anticipated up to 2015 between ICT sector demand and the do-mestic supply of computing graduates of about 2,000-3,000 and hundreds for electronics grad-uates. Such concerns remain relevant in the post-crisis context and the gap between demand and domestic supply will have to be bridged by an inflow of graduates from outside Ireland.

· In Slovakia, research in the region of eastern Slo-vakia suggested that the number of graduates participating in ICT-oriented tertiary study pro-grammes will not cover the growing demand for ICT workers. Additionally the brain drain from the region is exacerbating the skills gap.

· In Sweden, there is an excess supply of program-mers forecast until 2025, after which a shortage is forecast.

· In Iceland, the expansion of the ICT sector will depend on the availability of computing pro-gramming graduates. Currently, the number of graduates in science, mathematics and comput-ing remains low and it has even declined recent-ly (18.2% of all graduates in the academic year 2000-2001 to 15.6% in 2009-2010).

It is important however to highlight that across the coun-tries, new waves of ICT graduates will only represent part of the workforce joining the sector. For example, in the UK, on an annual basis up to 2015 it is expected that 18% (22,600) of the average annual net recruitment needs will be met by tertiary education graduates, com-pared to 43% from those already in work in other sectors (and 39% from other sources) (EU Skills Panorama Ana-lytical Highlight. 2012).

The existence of hard to fill vacancies

Prior to the recent economic recession, skills shortages and gaps in the ICT sector have been widely reported in various EU countries. In the Czech Republic, for exam-ple, employers have repeatedly reported job vacancies in the ICT sector as hard-to-fill.

Commonly reported hard to fill vacancies concern func-tions such as:

- help desk or end-user support functions

- data centre specialists

- network specialists

12

- storage specialists

- security specialists

- application designers or programmers

- system architects

- project managers

According to an employer survey across Europe, the types of hard skills that were most difficult to find include ‘net-working’ and ‘security’; a shortage of systems architects and project managers were also reported in some coun-tries.

Skills mismatches by country and by type of skills remain a concern for the sector (EU Skills Panorama Analytical Highlight. 2012):

· In Ireland, currently the recruitment difficulties are evident among computer software engineers, personnel with foreign language skills and ICT technical background, ICT network specialists and engineers, ICT security experts, ICT tele-communications, ICT project managers with technical background; and sales and marketing personnel with IT technical background and rele-vant industry knowledge.

· In Italy, 23.7% of all hires were considered dif-ficult in the ICT sector in 2011, a percentage similar to the share for all sectors. However, re-cruitment difficulties are more prevalent among computing professionals and computer associate professionals where about one third of hires pro-jected for 2011 were considered difficult.

· In Norway, shortages of engineers are reported in the ICT sector and well as skills shortages in soft-ware development and data technicians. Accord-ing to an employer survey in 2012, 17% of ICT firms had to recruit persons with an educational background other than that initially required.

· In the UK, according to the 2011 IT employer survey, 11% of IT employers are aware of skills gaps among employees and, of these, one third report this for IT and telecoms staff (34%). Skills gaps are prevalent in large firms and seem to be concentrated in the occupations of programmers / software development professionals and web design / development professionals. Non-techni-

cal skills gaps were also a concern for about two thirds of employers reporting skills gaps. Gaps most commonly mentioned are interpersonal skills and sales-related skills, and to a lesser extent, the ability to align IT activity with business needs and to identify new product/process opportuni-ties enabled by IT and telecoms.

Assuming a continuation of past trends, skills gaps will emerge in relation to high level technical skills among ICT professionals (for the design and development of ad-vanced services) but also in terms of managerial/customer oriented skills. However, a decline in demand may oc-cur for other types of ICT hard skills such as traditional programming, given the introduction of more innovative programming techniques.

The re-emergence of skills gaps and the rapid evolution of new skills/applications within the sector pose particular challenges for on-going skills development and supply. In these circumstances strong co-operation between ICT companies and the education and training sector is essen-tial to guarantee that learning and development is flexi-ble, up-to-date and rapidly responsive to needs.

13

Historically, employment in the sector has been and re-mains predominantly male. In 2011, only 22% of em-ployees were women and this has not changed in the last decade. The Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Norway are among the countries where the proportion of women in the sector is below the EU average (EU Skills Panorama Analytical Highlight. 2012).

The lack of trained female professionals means that in OECD countries, women now account for less than 20 per cent of ICT specialists. It also means that most de-veloped countries are forecasting an alarming shortfall in the number of skilled staff to fill upcoming ICT jobs. The European Union calculates that in ten years’ time there will be 700 000 more ICT jobs than there are pro-fessionals to fill them; globally, that shortfall is estimat-ed to be closer to two million. One of the reasons why the ICT sector continues to be generally perceived as a male-dominated industry is because most high-value and high-income jobs in this sector are occupied by men (A Bright Future in ICTs opportunities for a new generation of women. 2012).

Research conducted for the study made by International Telecommunication Union, Telecommunication De-velopment Bureau in both developed and developing countries found classic cases of vertical gender segrega-tion, with women strongly represented in lower level ICT occupations. Although women are making inroads into technical and senior professions, the study indicat-ed a ‘feminization’ of lower level jobs. On average, this research found that women accounted for 30 per cent of operations technicians, only 15 per cent of managers and

a mere 11 per cent of strategy and planning profession-als. There is also space for significant improvement in the number of women holding leadership positions at board and senior management levels

Gender balance in high value ICT jobs in both manage-ment and on company boards has been proven to improve business performance. Studies exploring the link between women in leadership positions and business performance have shown a direct positive correlation between gender balance on top leadership teams and a company’s finan-cial results. More balanced teams make better informed decisions, leading to less risk-taking and more successful outcomes for companies. Over time, therefore, a nation’s ICT competitiveness depends significantly on whether and how it educates and utilizes its non-discriminatory human capital (A Bright Future in ICTs opportunities for a new generation of women. 2012).

The age profile of employees in the sector is relatively young, with only 13.7% of the workforce in 2011 aged 50-64 compared to 26.1% across the entire economy (EU Skills Panorama Analytical Highlight. 2012).

4 Gender Issues

14

Future developments in the ICT sector will be largely shaped by the following factors (EU Skills Panorama An-alytical Highlight. 2012):

· The current pathway of development and growth of the ICT sector in each country

· The speed of technological developments and the diffusion of ICT-based innovation

· The level of public and private decisions to step up ICT investments

· Globalisation and general economic trends.

There are important structural differences between coun-tries in relation to skills demand in the ICT sector. The demand for skills is likely to be stronger in those coun-tries which are ‘lagging behind’ and where the economy is less mature in terms of the adoption and diffusion of ICT, and which therefore are expected to experience rel-atively greater growth in demand for computer program-ming, consultancy and related services.

In other countries where the ICT sector has grown sub-stantially in recent decades, growth will continue but is expected to remain modest. For example, the ICT con-sultancy services sector is expected to remain relatively stable in Denmark after having experienced a 30% in-crease since 2005. Similarly in the UK, the ICT services market is mature and largely saturated and further invest-ment and innovation will be the key to maintaining or growing markets. In Norway, the ICT sector has turned

into one of the country’s flagship industries and is expect-ed to continue as such.

The long-term impact of the current recession on the ICT sector is relatively hard to assess, past evidence sug-gests that ICT sector growth rates do follow general eco-nomic trends, however, the sector has recently performed better than the overall economy. Indeed, ICT companies were better equipped to deal with the current recession by comparison with the situation observed after the 2001 ‘dot-com’ crisis.

The computing services sector will continue to expand in the EU. Employment growth of 7.6% is forecast, from 3 million workers in the sector in 2010 to 3.2 million in 2020. Compared with the average of 3.4% employment growth forecast across all sectors, ICT will be one of the fastest growing sectors in Europe.

Emerging demand for ICT services in countries locat-ed outside ‘mature’ European markets could lead ICT companies to open new research centres and branches in these new markets. Off-shoring of ICT services is also considered to be an important trend for the sector. While the manufacturing of computer hardware has been off-shored for some time, the relocation of the ICT service industry outside Europe is a more recent phenomenon. The growth of off-shoring activities depends on several factors such as the availability of skills in the offshore lo-cation, local ICT infrastructure and the success of devel-opments such as cloud computing or utility computing and whether or not services are suitable to be provided from a distance. Off-shoring of ICT services is expect-

5 Skills Forecasting & Anticipation in ICT sector

15

ed to remain relatively limited as a proportion of overall ICT services revenues. The impact of off-shoring on the European ICT sector labour market thus far has not been negative as indeed, the sector has expanded at the same time as relocations have taken place. Going forward, the EU is more likely to off-shore mature, low value add-ed ICT services (with lower profit margins) to non-EU countries while exporting higher value added new and innovative ICT services.

In the medium term, the outlook for the ICT sector will remain positive, as demonstrated by these country examples (EU Skills Panorama Analytical Highlight. 2012):

· In Cyprus, the ICT sector is expected to be one of 10 high growth sectors. Employment in the sec-tor is expected to grow by 3.4% per year between 2010 and 2020. During this period, there will be increasing demand of 5% per year for ICT man-agers, 3% per year for Analysts and Programmers and 5% per year for ICT assistant technicians and for PC assistant technicians.

· In France, the ICT sector is expected to create around 81,000 net new jobs during 2010 - 2020, from a base of 534,000 jobs in 2010. The jobs created in the ICT sector are expected to consti-tute around 5% of the 1.5 million net new jobs anticipated by 2020.

· In Ireland, strong growth in the demand for soft-ware engineering professionals (42.4%) and com-puter associate professionals (25%) is anticipated. The ICT sector has to some extent recovered the job losses suffered after the 2008 downturn.

· In the UK, after a period of a decline, output levels in the ICT sector are expected to pick up significantly in the coming decade. The net im-pact on employment is modest in relation to the pre-recession growth. Professional occupations are still expected to dominate the sector. The occupational structure of the sector favours the highest-qualified. This is expected to continue, moving from the current 55% of employees being highly-qualified to 60% by 2020. Intermediate level qualifications are anticipated to fall signifi-cantly (to under 20% of the workforce), while the share of low level qualifications are projected to rise slightly.

5.1 Up skilling and the need for a non-technical and soft skills

The ICT sector relies on a mix of hard technical and soft skills among its workforce, with a trend towards general up-skilling across the different categories of ICT occu-pations. The numbers of less knowledge intensive ICT jobs are expected to fall as the structure of skills demand changes. The demand for low-end developers and data-base administrators are expected to be replaced by de-mand for business analysts, sales specialists and high-end developers. There has been a shift in the skills mix of the sector with lower-skilled jobs being replaced by high-er-skilled jobs and that up-skilling is expected to contin-ue in the foreseeable future.

As demand for specialist skills evolves very quickly in the ICT sector, the risk of skills obsolescence is particular-ly important. Recently, growing needs have been iden-tified for ‘hard’ ICT professional skills in fields such as data privacy, server technology, general networking and network infrastructure. For example in the UK, studies have identified increased demand for ICT professionals with technical skills especially those linked to Microsoft products. Due to the increased application of ICT across all economic sectors, specialist ICT technical skills are becoming increasingly transferable outside the core ICT sector increasing demand and competition for skills.

According to both European and national evidence, a range of soft skills will become increasingly important for both ICT specialists and the rest of the sector’s workforce. In the UK, interpersonal skills and sales-related skills are seen as key shortages by ICT sector employers. The key non-IT skills in demand in the ICT sector include:

· Business skills – including creativity and inno-vation, customer service skills and sales

· Project management and administration – including organisational, managerial and finan-cial skills

· Communication – including verbal and writ-ten presentation to internal and external audi-ences, ability to work collaboratively with other employees;

· Foreign language skills

16

5.2 Current and forecasted labour and skills demand in the ICT sector

Across the EU, the sector has experienced continuous growth. Between 2000 and 2011, the sector gained around 600,000 additional workers - a growth of 29 %. However, the trend across individual countries differs significantly, from substantial sector growth in Slovenia, Slovakia and Portugal to zero growth in the UK, Roma-nia and Italy and a small decline in Denmark and Ice-land. Some countries have mature ICT sectors, whereas in others the sector has only recently developed.

Increasing demand for ICT professionals in the sector

Recent recruitment trends in the ICT sector reveal an in-creasing demand for ICT professionals, as demonstrated in the following country examples:

· In Belgium, 71% of ICT sector enterprises report-ed serious problems in representatives, analysts/programmers, project leaders and IT technicians while the larger ICT enterprises require develop-ers/analysts programmers and IT project leaders.

· In Ireland, vacancies in the sector have increased

notably since the 2008 global financial crisis. Va-cancies are reported for programmers and soft-ware developers, network experts, IT business an-alysts, architects and systems designers, IT project managers and multilingual IT technical support.

· In Italy, almost four fifths of total hires in the ICT sector in 2011 were in high skilled occupations.

· In Slovakia, ICT companies in the eastern Slo-vakia region planned to increase the number of workers by 40.4% in 2009 (some 1,068 new jobs). In absolute terms, most new jobs were ex-

pected for IT technicians, programmers and tes-ters.

· In Slovenia, computer engineers were the ninth most sought after occupation in 2011.

· In Norway, quarterly ICT industry job vacancies grew by 35% from an average of 2,300 in 2010 to 3,100 in 2011.

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

ISDKITROUKNLSEIENOEEFRBEDEFILTHUMTELPLLUBGATCZHRESCYLVPTSKSI

Chart no 4 : growth in employment in computer programming, consultancy and related activities from 2000 – 2011 (%)

Source: Eurostat, Labour force survey

17

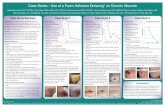

Based on the present case study the key recommenda-tions are being made and are illustrated in the chart no 5.

The key measures in order to assure better matching of the required skills from the side of employers and skills and knowledge of the young graduates can be summed up in the following 4 points:

- Appropriate policy measures to boost youth employment and to promote entrepreneurship

- Improvement of cooperation between employ-ers and educational organizations and stronger

involvement of the employers to the drafting of the study programmes

- Introduction of measures and promotion in order to attract more women in ICT related studies

- Promotion of STEM (science, technology, engi-neering, and math) fields of study among young people to bridge the shortage of skills

6 Recommendations

High overall unemployment rate in youth population across the EU

Growth of demand of high-level skills

and non-ICT skills in ICT sector

ICT sector as a male-dominated sector

Existence of hard to �ll vacancies

Policy measures to boost youth employment and to promote entrepreneurship

Improvement of mutual

communication between

employers and educ. org.

Introduction of measures to attract more women in ICT

Promotion of STEM �elds of

study among young

Chart no 5: key recommendations

18

Reforming education systems and increasing digital skills learning opportunities will help prepare young Europeans for the jobs of both today and tomorrow.

The European commission warns that by 2015 Eu-rope will lack up to 900,000 ICT professionals, a shortfall that will be aggravated by a projected de-cline in computer science graduates.

This situation is a result not only of the economic crisis experienced in some member states, but also of an opportunity divide or a gap between those who have the access, skills, and opportunities to be successful and those who do not. The main question that policymakers and industry leaders must now tackle is how to close this gap during times of eco-nomic downturn?

The European commission’s recently announced “opening up education” initiative is a step in the right direction. The initiative will integrate existing and new actions to promote the use of ICT and open educational resources in education and train-ing. “Opening up Education” will also be designed to address common challenges faced by several ed-ucation sectors (schools, vocational and education training, higher education, adult education) and to support sectors as they address their own specific needs.

Young Europeans have got talent. But often they lack the digital skills they need to excel in the jobs of today and tomorrow. Reforming European ed-ucation systems and increasing adaptive-learning components will help close the opportunity divide.

Technology is both the key and the vehicle for mak-ing this happen. It is clear that ICT can upgrade the quality of education in several ways - includ-ing more personalised learning programmes, which would address the individual needs and interests of students, widening access to education through in-ternet and cloud computing as well as facilitating global collaboration among students through com-munication platforms such as Skype.

Overall, we need to create a level playing field for young Europeans, by offering them digital skills which will lay the foundations for their profession-al success. The issue is urgent: the European com-mission estimates that by 2020 as much as 90 per cent of jobs in the EU will require digital skills. Closing the gap between demand and supply of these skills is a challenging goal which cannot be achieved by a single government, sector or organi-sation alone. Decision makers from the public and private sector must join forces to pool their resourc-es and expertise to help pupils, students and teach-ers to fully benefit from the digital revolution.

7 Conclusions

19

1. Afke Schaart. September 2013. The Parliament Digital skills crucial in closing ‘opportunity divide’ for EU’s youth unemployed http://www.thepar-liament.com/latest-news/article/newsarticle/digital-skills-crucial-in-closing-opportunity-divi-de-for-eus-youth-unemployed/#.UkWv535BuIc

2. Der Spiegel. Alexander Demling. 2013. Distorted Stats: Europe’s Youth Unemployment Fallacy.

3. E-skills. 2012. Diagnosis about the improvement of employment opportunities for young people in the ICT sector

4. EU Skills Panorama. 2012. Information and Com-munications Technologies (ICT) Sector Analytical Highlight, prepared by ICF GHK for the Europe-an Commission

5. Eurofound report. 2012. NEETs – Young people not in employment, education or training: Charac-teristics, costs and policy responses in Europe

6. European Commission - Employment, Social Af-fairs & Inclusion - Youth employment: http://ec.eu-ropa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1036&langId=en

7. Federal Department of Foreign Affairs FDFA. Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Educa-tion and Research EAER:

http://www.contribution-enlargement.admin.ch/en/Home/Projects/Focus_on_projects/Reform_

of_the_Slovakian_vocational_education_system

8. InoPlaCe project: www.inoplace.eu

9. International Telecommunication Union. Tele-communication Development Bureau. 2012. A Bright Future in ICTs opportunities for a new gen-eration of women. DIGITAL INCLUSION 2012. Geneva.

10. Košice IT Valley. 2009. Identifikacia sucasnych a ocakavanych potrieb firiem v oblasti informacnych a komunikacnych technologii v regione vychodneho Slovenska (‘Identification of current and expected needs of enterprises in the ICT sector in Eastern Slo-vakia’): http://www.kosiceitvalley.sk/public/File/identIT/IdentIT-online.pdf

11. Max Uebe. 2012. Speech: Conference “Working together to foster youth employment” 13 November 2012. European Commission

12. Monika Martišková. 2013. EU’s Youth Guarantee is Unlikely to Dramatically Help Slovakia’s Young Unemployed. Visegrad Economy. 15.2.2013.

13. Slovak investment and trade development agency - SARIO: http://www.sario.sk/?ict-en

14. European Commission – education and culture. 2013. “Opening up Education – a proposal for a European Initiative to enhance education and skills development through new technologies”

8 References