Young Children and Technology - ccie.com · written extenstively and is perhaps best known for his...

Transcript of Young Children and Technology - ccie.com · written extenstively and is perhaps best known for his...

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 43

➤ Young Childrenand Technology

Child Care Information Exchange ¥ PO Box 3249, Redmond, WA 98073-3249 ¥ (800) 221-2864

Computers for Infants and Young Children by David Elkind

Using Technology to Enhance Early Learning Experiences by Kirsten Haugen

Creative Use of Technology with School-Agers by Ina Lynn McClain

Evaluating and Selecting Software for Children by Charles Hohmann

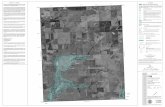

Photograph by Bonnie Neugebauer

Be

gin

nin

gs W

ork

sho

p

➤

➤

➤

➤

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 44

The fastest growing crop of educational software is socalled lapware for infants and toddlers from six monthsto two years. As the term lapware implies, this softwareis targeted to an infant who is seated upon her parentÕslap. While a limited exposure of children three yearsand older to computers can be justified, a comparablecase cannot be made for infants and toddlers. The parentÕs lap notwithstanding, the use of computerswith the very young carries many more risks than itdoes benefits. In this article I will present a cost/benefitanalysis of computer use for the two age groups Ñinfancy and toddlerhood (ages 0-2) and the preschoolyears (ages 3-5).

At the outset, I want to make clear that I am notopposed to technology or to computers. Technologyand computers are simply tools that can be used forgood or ill. It is the misuse of technology in general,and of computers in particular, that can do harm tochildren.

■ Infancy and Toddlerhood

The following is the sales pitch for a lapware programcalled Colors designed for infants and young children.

by David Elkind

Computers forInfants andYoung Children

Be

gin

nin

gs

Wo

rksh

op

David Elkind is a professor of child development atTufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. He haswritten extenstively and is perhaps best known for hispopular books Ñ The Hurried Child, All Grown Up and No Place to Go, and Miseducation. Professor Elkind is a past president of NAEYC. Hecurrently is the co-host of the Lifetime television series, ÒKids These Days.Ó

These programs are, however, more than just wasteful;they are potentially harmful. An infantÕs visual systemis not fully developed until about the second year. WedonÕt know what the effect of watching a computerscreen may be on the visual system which is notadapted to that type of stimulation or overstimulation.In addition, encouraging the child to concentrate onvisual stimuli could lead him to neglect informationcoming from the other senses. Yet this is an age whenchildren should be developing all of their senses to aidin sensory integration. Auditory discrimination, forexample, must be integrated with visual discrimina-tions for children to move successfully into reading. Atoo early concentration on the visual could impair thedevelopment of the other senses and the wholeprocess of sensory integration.

An even more serious side effect of such program-ming is their potentially harmful impact upon theparent-child relationship. One of the characteristicsof such programs is that they suggest to the parentthat there are right and wrong responses the infant ortoddler can make to the screen. Without even beingfully aware of it, parents may emotionally rewardthe baby when he makes a right response and emo-tionally withdraw when he makes a wrong response.Parents may even get frustrated and angry at theinfantÕs wrong responses. This puts the young childin an unnecessarily stressful situation in whichbehavior that is meaningless to him gets randomlyrewarded or punished. Lapware thus has the poten-tial for impairing the childÕs sense of trust and secu-rity that are essential for the infant to explore hisworld with pleasure and confidence.

There are many good reasons, then, for not exposinginfants and toddlers to lapware. The people whodesign the programs donÕt know infants and youngchildren and try to teach them either what theyalready know or what is far beyond their intellectualreach. In addition, getting a young child to focus herundeveloped visual system on a computer screenmight do damage to that system and also inhibit thedevelopment of the other senses and their integration.Finally, by putting parents in a right/wrong mind set,such lapware may impair an infantÕs healthy attach-ment to, and trust in, parents. The resulting insecuritycould have a negative affect upon healthy develop-ment.

■ Early Childhood

By the age of three, most children are well along inboth their sensory motor development and integration,and in their language development. At this age, some

ÒDoes your child know his primary colors? Colorssounds and graphics will capture the young oneÕs atten-tion and before they know it they are learning. Colors isdesigned as infantware. Colors will aid your toddler inlearning his or her primary colors. It also helps themassociate letters and the written word with the spokenword.Ó ÒEcho KidsÓ (Infant Software, The Net)

Let us examine this claim that Colors will teach infantsand toddlers the primary colors and help them associ-ate the printed letters and words with the spoken one.First of all, it is well established that infants can identifycolors during the first few months of life without theaid of any computer program. By about two months,babies can tell red from green; and by four months,they can respond selectively to red, green, blue, andyellow. Like adults, they also prefer red and blue to theother colors (Bornstein, 1976; Teller and Bornstein,1987). Clearly, the writers of Colors do not know any-thing about infant visual development or they wouldnot have designed a program to help infants learnsomething they already know.

The program also purports to teach infants and youngchildren to associate printed letters and words with thespoken word. Here again, this assertion is totally atvariance with the abundant research regarding theattainment of literacy. First of all, the infantÕs visualsystem is relatively undeveloped. It is only after abouttwo years that toddlers have the visual acuity to dis-criminate between different letters, and the ability toidentify words comes even later. It is only during thethird year that some children learn to associate thesediscriminations with letter and word names. Secondly,children do not begin to associate letters with the(abstract) sounds that they represent until at least agefour or five. Finally, the first words children learn arenot color words but rather function words that are tiedto concrete actions, such as ÒstopÓ and Ògo.Ó The under-standing that letters and printed words are symbols forsounds and spoken words is an extraordinarily complexachievement that most children do not acquire untilages five or six (e.g., Baron, 1992).

The above critique reveals the major problem with so-called lapware and indeed with much of the softwarefor infants and young children. Basically, those writingthe software do not know child development and makeno effort to learn even the basics of what research has totell us about what children learn and when. As a result,they make the two errors that were illustrated above;namely, they either instruct the child in something shealready knows, or they attempt to teach the child skillsthat are far beyond the childÕs developmental reach. Forthese reasons, such programs are a waste of both timeand money.

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 45

Be

gin

nin

gs W

ork

sho

p

Sesame Street that although television helps childrenlearn their numbers and letters earlier than ever before,this does not translate into better reading and mathskills. That fact is clearly evidenced by our falling read-ing and math scores and by our low standing on inter-national comparisons of academic achievement. Iftelevision has not been successful in teaching youngchildren higher order reading and math skills, whyshould computer programs?

Computers for young children are, then, far from anunmixed blessing. While some exposure of childrenover three to well designed and age appropriate pro-gram may do no harm, it is unlikely that such exposurewill have important benefits. There is no evidence thatthis experience gives children an edge in computer literacy, self-confidence, or self-esteem. In this regard, itis well to remember that Bill Gates did not have a com-puter as an infant and young child, nor did the majorityof those individuals designing the hardware and writ-ing the software for computers. All of the purportedbenefits of exposing infants and young children tocomputers can easily be acquired through other meansand with less risk.

■ References

Baron, N. (1992). Growing up with language. Reading,MA: Addison Wesley.

Bishop, P. (1998). Toddler tested: Little tykes stake aclaim for their place at the PC. Family PC, January.

Bornstein, M. (1976). Infants are trichromats. Journal ofExperimental Child Psychology, 21, 425-445.

Teller, D. Y., and Bornstein, M. (1987). Infant colorvision and perception. In P. Salapetek and L. B. Cohen,(editors), Handbook of infant perception. New York: Academic Press.

exposure to the computer and carefully selected com-puter programs is much less risky that it is at the ear-lier age levels. But even for this age group, some of thebasic errors of the lapware developers are again in evi-dence. For example, those who advocate software fortoddlers argue that it teaches them that they have con-trol over their own learning. Yet infants who discoverthat a rattle makes a sound when it is shaken do notneed a computer program to tell them that they havecontrol over their own learning.

Other reasons for exposing young children to computerprograms were expressed by teachers and parentsparticipating in a study of how children under four

respond to computer programs carried out by Bishop(1998). The parents and teachers looked at eight titlesdesigned for children four years and under. Thetesters were generally pleased with what they found.The reasons given for introducing computers tochildren at a young age were predictable. ÒTeachingyoung children computer skills gives them a headstart for the skills they will be learning at school.Ó Or, computer programs Òallow children to makechoices and encourage them to become confident self-motivated learners.Ó

Yet many computer skills are learned more quickly,and more effectively, at a later age than at an earlyone. An eight year old will pick up keyboard andmouse skills more quickly than an infant and be lesslikely to develop bad habits and misunderstandings.Likewise, there is no evidence that computers giveinfants an academic head start. On the other hand,there is abundant evidence that children can learn tomake choices and to become self-motivated, confidentlearners without computers.

Bishop also argues that in addition to the abovebenefits, computer programs introduce children to the ABCs, to 1,2,3s, to color recognition, and otherbasic skills. Yet we know from more than 20 years of

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 46

Be

gin

nin

gs

Wo

rksh

op

When one sees computers as number-crunching, word-processing, video game-playing machines, itÕs hard toenvision how they could play a beneficial role in theplay and learning of young children. But set one upwith developmentally appropriate software, place it ona low, wide table Ñ or even on the floor Ñ and bringalong some books and props, a few peers, and a caring,informed adult, and the computer becomes a magical,multi-sensory environment inviting exploration anddiscovery!

Computers have become a pervasive (perhaps invasive)presence in our lives. Technology will impact youngchildren, but early childhood educators have an oppor-tunity to help ensure early experiences with technologyare developmentally appropriate and empowering forall children, regardless of gender, socioeconomic back-ground, or ability. ÒIn practice computers supplementand do not replace highly valued early childhood activities and materials. . . . Research indicates thatcomputers can be used in developmentally appropriateways beneficial to children and also can be misused,just as any tool canÓ (NAEYC, 1996).

What We Know About Technology and Kids

Researchers have been observing young learners inter-act with microcomputers for over two decades. We nowknow something about choosing developmentallyappropriate software, and about the kinds of computeractivities that can positively impact learning and socialbehavior.

Using Technology toEnhance Early Learning Experiences

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 47

Be

gin

nin

gs W

ork

sho

p

by Kirsten Haugen

Kirsten Haugen works as a consultant for adaptive and educational technology in Gainesville, Florida.Learning from real experiences with local kids formsthe foundation of her teacher trainings, conference presentations, and curriculum development activities.

ateness for a given child, group, or activity. Select com-puter activities to support class themes. Provide propsand manipulatives, inviting children to use all learningmodalities.

■ Modeling. While it is not our primary job to walkkids through a particular software program, modelingplays a critical role in successful computer use. Notonly can we model safe and appropriate use of com-puters, turn-taking, and other social skills, we can alsomodel ways of thinking and talking about an activity.ItÕs helpful for a skilled adult to interact with childrenaround an activity before allowing them to explore ontheir own. This will guide them in their explorationand help focus their attention.

■ Facilitating. Pair students with complimentaryskills. Encourage problem-solving Ñ ÒWhat wouldhappen if . . . ?Ó Simply describe what children aredoing and ask questions Ñ ÒOh, youÕve made a house!Tell me about the shapes you used.Ó Sometimes whenkids get stuck, gentle suggestions on when to taketurns, divide a task, or try something new may beappropriate. And when the inevitable technical difficul-ties occur, invite children to help with trouble-shooting.

■ Observing. ÒAs we listen and question, we discovermore often than not that we are the learnersÓ (Wrightand Shade, 1994). Take time to simply watch and listento children at the computer (and elsewhere) to learnabout how they perceive, solve problems, communi-cate, and collaborate. Computers can support or com-pensate for developing motor or language skills, thusobserving computer play can help identify emergingskills.

Level Playing Fields and Curb Cuts

One special benefit of technology is the many ways inwhich it can level the playing field for kids with specialneeds by supporting their efforts to communicate,explore, play independently, or cooperate with a peer.In return, many products and strategies initiallydesigned to accommodate children with special needsare now finding useful roles in mainstream early learn-ing environments. Just as wheelchair curb cuts makelife easier for people with strollers, bicycles, and handtrucks, typical kids benefit from more accessible andmeaningful tools like Touch Windows,¨ software thattalks, and alternative keyboards like IntelliKeys,¨ whichuse custom overlays of pictures and words.

Kids with disabilities also benefit from low-tech tools,such as large button-like switches for safely and easily

While the market has been flooded with childrenÕs soft-ware, by no means is all of it appropriate or beneficial(Haugland and Shade, in Wright and Shade, 1994).Children themselves donÕt always make the mostappropriate choices, so teachers play a critical role inselecting software. Open-ended software, in which children are free to explore and experiment (rather thanworking through a preprogrammed sequence of prob-lems), has many beneficial as well as enticing featuresfor young children.

■ Children click on a word in the Living Booksª

version of The Cat and the Hat, and the word is spoken,spelled, or animated, providing a rich context for

language exploration.

■ Using a painting program, two children make acircle, fill it in, change the color, add a sad face, thenmake it a happy face, narrating and negotiating asthey go. Opportunities to repeat, alter, or undoactions allow children to experiment at their ownpace. And when theyÕre done, copies can be printedfor each child and for a class album.

■ Children click fish on screen one by one to makethem swim to the other side; the computer countsaloud and shows the number, helping childrendevelop number sense and one-to-one correspon-dence. Carefully designed constraints, cues, and feed-back provide scaffolding for skills just beyond achildÕs mastery.

Computer play can also positively impact social skills.Numerous studies demonstrate that when using com-puters, young children prefer to work with othersrather than alone, and prefer seeking help from peersrather than adults. Apart from practicing turn-takingskills, children also do a great deal of talking, negoti-ating, and cooperating to explore, create, or problem-solve within computer environments (NAEYC, 1996).

Computers, however, do not replace teachers. Thesebenefits have been realized through the efforts of adultswho understand the technology and the reasons forusing it, and are available to facilitate, just as theywould in other activities.

The Adult’s Role

As with many activities, adults help to set the stage,model the activity, facilitate, and observe.

■ Setting the stage. Safely set up the computer toencourage exploration and cooperation (see box onpage 55). Choose software by evaluating its appropri-

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 48

Be

gin

nin

gs

Wo

rksh

op

more familiar materials. Tying the computer into yourfavorite themes gives computer use a purpose andfocuses the process of selecting software and introduc-ing activities. In addition, a theme provides clear conti-nuity across all the activities in the classroom, givingyoung learners a leaping off point for their own explo-rations.

■ All Aboard! The library corner is filled with books ontrains. The playhouse is now a station, with suitcases,engineerÕs hats, and bandannas added to the dress ups.The blocks suddenly become buildings, train cars, andtracks. A field trip to the local subway or Amtrak sta-tion is planned. Tracks appear in the sand table. In theart corner, large boxes are ready to be transformedinto box cars, cabooses, engines, and more. In themath area, small train cars are ready for counting orsorting by color, type, or size.

How can technology add to this rich thematic experi-ence? Imagine pairs of children telling a story byusing a slideshow program to sequence their owntrain pictures and record their voices Ñ on-screen,itÕs a talking book, with a printed copy for each child.Other children decide to print up tickets and a sched-ule for the train station Ñ the computer allows themto try out several different designs. With multimediaauthoring software like IntelliPics¨, the teacher createsa simple but effective activity for matching, counting,and coloring different types of train cars. Childrenexplore train themes further using multimedia CD-ROMs like The Way Things Work (Dorling Kindersley)and integrate this knowledge back into their imagina-tive and social play.

■ Mary Wore Her Red Dress. Another approach to cre-ating a theme is to start with a favorite piece of soft-ware and build a theme around it. Kit Kehr, of theUCLA Intervention Program, describes a week-longtheme built around the multimedia story Mary WoreHer Red Dress (Don Johnston, Inc.). Every day, theteacher facilitates activities built around the software.For example, a large laminated copy of Mary withclothing to Velcro on provides the basis for a group lan-guage activity. In addition, similar clothing for thedolls, dress ups, and felt paper dolls allow kids toextend the activities in other ways. Week-long themesare helpful because ÒitÕs developmentally more mean-ingful to have that repetition, which is what kids aredrawn to do.Ó And by the end of the week, kids haveencountered the concepts of color, clothing, categoriza-tion, and sequencing in an array of related contexts.While experts rely on this approach all the time, it alsoworks especially well for teachers who donÕt have thetime or skills to create custom activities.

controlling electrical appliances, and simple communi-cation devices which allow a child to talk by touchingone or more pictures to play a recorded message. Expe-rienced teachers combine these high- and low-techtools with more familiar early childhood materials togive kids with disabilities essential early learning expe-riences which are otherwise inaccessible, and to facili-tate learning opportunities for all kids.

These extensive efforts have shown positive results. Ina study by the UCLA Intervention Program, toddlersand preschoolers with disabilities showed more activeengagement, enjoyment, and social play during age-appropriate computer activities involving peers andadults than during similarly structured activities awayfrom the computer (Howard et al., 1996). Another pro-gram in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, used computers andassistive devices for story time activities, and foundÒchildren with disabilities demonstrated an increase inspontaneous interactions, turn-taking, initiatingwants/needs, and simple problem-solving skillsÓ(Baldwin et al., 1996).

Technology Outreach Time (TOT), a new pilot literacyproject for educationally disadvantaged and disabledfour year olds, puts these findings to work. CarolinaComputer Access Center director Judy Timms writes,ÒWe already know that good software and assistivetechnologies, if used effectively by trained teachers, canbe classroom equalizers for children with disabilities.They also give children from disadvantaged environ-ments self-confidence and important knowledge thathelps level the playing fields with typically developingpeers.Ó TOT is a collaboration of CCAC, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, and three innovative technologyvendors.

Programs like TOT which reach out to disadvantagedchildren are vital, but generally Òthe most needystudents are getting the least access to technologyÓ(NAEYC, 1996). Child care centers and preschools serv-ing children from disadvantaged backgrounds have anopportunity to level the playing field for these childrenby providing developmentally appropriate experienceswith computers.

Putting It All Together: Using Technology with Thematic Units

The key to the successful integration of technology intoearly childhood settings is to see computers in the samelight as traditional materials rather than as somethingapart. Perhaps the best starting point for using comput-ers to benefit young learners is to incorporate them intothematic teaching units in much the same way we use

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 49

Be

gin

nin

gs W

ork

sho

p

■ NAEYC (1996). Position statement on technology andyoung children Ñ Ages 3 through 8. Washington, DC:NAEYC, April.

■ Timms, J. (1998). ÔTOTÕ takes off. Link Up, Winter, Vol. 9, No. 1. Charlotte, NC: Carolina Computer Access Center.

■ Wright, J. L., and Shade, D. D. (editors) (1994). Youngchildren: Active learners in a technological age. Washing-ton, DC: NAEYC.

Resources

■ Alliance for Technology Access (ATA), (415) 455-4575,<www.ataccess.org>

■ Broderbund/Living Books, (800) 474-8840,<www.broderbund.com/education> (Kid Pix, Living Books, more)

■ Carolina Computer Access Center (TOT Program),(704) 342-3004, <http://ccac.ataccess.org>

■ Closing the Gap, <www.closingthegap.com>

■ Creative Communicating, (801) 645-7737, <www.creative-comm.com> (Storytime software andadapted books)

■ Don Johnston, Inc., (800) 999-4660, <www.donjohnston.com> (Circletime Tales¨ andUKanDu¨ software, Discover¨ tools for computeraccess, more)

■ Edmark, (800) 362-2890, <www.edmark.com> (Kid Desk¨, ÒHouseÓ series for young children; TouchWindow¨; more)

■ IntelliTools, (800) 899-6687, <www.intellitools.com>(IntelliKeys programmable keyboard, IntelliPicsauthoring software, Animal Habitats, more)

■ National Association for the Education of YoungChildren (NAEYC), (800) 424-2460, <www.naeyc.org>

■ Toys for Special Children, (800) 832-8697, (Cheap Talkcommunication devices, ability switches, adapted toys,more)

■ UCLA Intervention Program/UCLA MicrocomputerProject, (310) 825-4821

■ Animal Habitats. A third time-saving approach tobuilding a theme is to base it on a purchased packagewhich includes both traditional and computer-basedactivities. Animal Habitats (IntelliTools) is one suchpackage, based on the story of The Curious Polar Bearwho travels the world visiting other habitats. Childrenexplore the book in print and in a talking version on-screen. Five different animal habitats provide the basisfor interactive computer activities exploring animalfacts, phonics, and language activities. The teacherÕsguide includes blackline masters and ideas for off-computer activities.

Concluding Comments

Focusing on curriculum is the key to successfully inte-grating computers into early childhood settings.Using technology to support favorite thematic unitscan help guide our thinking about technology andchildren. Computers will impact the lives of youngchildren either positively or negatively. Using com-puters to provide developmentally appropriate activi-ties for young learners helps ensure that as they grow,children will approach technology with confidence,realize its benefits and limitations, and use it as a toolin their life-long journey of learning and growth.

References

■ Alliance for Technology Access (1996). Computerresources for people with disabilities (2nd edition).Alameda, CA: Hunter House.

■ Baldwin, L., Dahlquist, L., and Miller, T. (1996).Reverse integration: Building the bridge withtechnology. Closing the Gap, October/November.

■ Bradley, M. (1996). Computer play for the veryyoung: More than cause and effect. Closing the Gap,June/July.

■ Cormier, C., Folland-Tillinghast, A., and Skau, L.(1998). Using assistive technology in thematicactivities. Closing the Gap, February/March.

■ Haugen, K. (1995). Using technology to help children with diverse needs participate and learn.Child Care Information Exchange, September/October.

■ Howard, J., Greyrose, E., Kehr, K., Espinosa, M., and Beckwith, L. (1996). Teacher-facilitated micro-computer activities: Enhancing social play and affectin young children with disabilities. Journal of SpecialEducation Technology, Spring, Vol. xiii, No. 1.

■ King-DeBaun, P. (1995). Babes in bookland. Closingthe Gap, October/November.

Be

gin

nin

gs

Wo

rksh

op

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 50

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 51

Be

gin

nin

gs W

ork

sho

p

Setting Up a Computer for Kids■ Set up the computer in an area large enough for at least two kids, an adult, and books, props, manipula-

tives, word cards, etc. Invite kids to work together by providing multiple chairs or cushions.

■ Get the interactive elements of the computer (the keyboard, mouse, monitor, and microphone) at kid levelÑ on a low table or even on the floor! If need be, use Velcro or other fasteners to stabilize these parts.

■ Keep the CPU (the box), disk drives, printer, etc., out of kidsÕ reach Ñ in a cabinet or up on a counter orshelf. Or buy or make covers for delicate parts. (Numerous commercial and homemade boxes have beendesigned to prevent damage or theft Ñ put a creative parent to work!)

■ Some centers with limited space or budget house the computer on a rolling cart so it can be shared amongrooms or put away during high energy activities.

■ Teach kids proper computer use and care, and post signs to remind them of the rules. Liquids, food, sand,and magnets can all damage a computer or its parts.

■ Trackballs or touch screens may be easier for young kids, as may alternative keyboards with fewer, largercolorful keys and alphabetical layouts, and flat, touch-sensitive keyboards which can use your custom layouts of words and pictures.

■ Use a kid-proof utility (Kid Desk¨, Fool Proof¨, etc.) to make the kidsÕ software and files easier to access,and to deter kids from moving, trashing, or changing key files and settings. Kid Desk¨ provides a kid-friendly environment with added features, such as a printable calendar with Òstickers,Ó and Òvoice mail.Ó

■ Not all software needs to be available all the time; the computer doesnÕt even have to be on all the time.Provide a sign to show when the computer area is open.

■ Select software to go with your favorite themes. Decorate the computer area to go with the theme. Offerindependent, cooperative, and group activities at the computer.

■ More is not better Ñ be wary of inexpensive software packages claiming to address every developmentalarea. Reputable educational software companies will send a demo disk or let you preview software.

■ Save $$ Ñ your local library or other resources may loan software or CD-ROMS; try software out beforeyou buy it; share recommendations with other educators and parents.

■ Use a digital camera or scanner to incorporate photos of kids and events into computer activities and art-work. Scanners can cost under $100.

■ If you have money for a new computer set-up, donÕt spend more than half on hardware. Use the remain-ing half for software and staff training.

Special Thanks to:

Suzanne Felt, Kit Kehr, Rick Metheny, Jennifer Ray, Judy Timms, Joe Valentine, Paula Weinberger,

Alice Wershing, and others for contributing their ideas and resources for this article.

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 57

Be

gin

nin

gs W

ork

sho

p

Megan and Rachel are industriously taking apart a computer.They have tested the hard drive of the computer they are nowdisassembling to find out why it does not work. The casecomes off the computer and they locate the hard drive andexamine how they will remove this part of the computer.They formulate a plan. With tools in hands, they chat abouttheir task as they proceed to remove the hard drive. They areonly aware of the others around them when they need infor-mation from an older youth or adult in the group. Once thehard drive is removed, they begin to do the same operation onanother computer. Their goal is to swap the hard drives. Theyextricate the hard drive from the second computer, slip it intoplace in the first, and secure it. Eagerly, they put the case onthe computer and test the hard drive. They squeal withdelight when it works.

Megan and Rachel (nine and ten years old) are part of a4-H Hardware Project. This project helps demystify themachine for youth involved by allowing them to takesurplus computers and physically upgrade the harddrive and/or add memory to the machine to handletheir favorite software. It also provides a mechanism forputting computers into communities, providing youthand families with more access to computers. Bill Past,

by Ina Lynn McClain

Ina Lynn McClain, MS, is a state 4-H youth development specialist with University Outreach and Extension located at the University of Missouri-Columbia. She has 19 years of experience working with communities to create non-formal educationalopportunities for positive youth development including school-age child care environments.

Creative Use of Technology with School-Agers

Kansas. Learning experiences for the youth integrated a variety of content areas Ñ- food preparation andsafety through campfire cooking, dramatic play, gamesand other recreation, and hiking the portion of the trailon the Army installation. The staff used the computerlab in the SAS program to enhance the learning experi-ences for the youth.

The software, The Oregon Trail by MECC, helped theyouth build a context for other learning experiences.The youth developed geographical concepts of wherethe trail began at St. Joseph, Missouri, and the end ofthe trail at Willamette Valley, Oregon. The softwareallowed the students to make choices about provisionsto purchase for the journey and the software providedfeedback as to whether these choices were wise or not.Weather and illness variables plagued the youth in thesimulation as they did the actual pioneers so manyyears ago.

Another software package titled StoryBook Weaver, alsoby MECC, allowed the youth participants to chronicletheir Oregon Trail experiences. A group of girls wereintrigued by an authentic diary at a local museum of ayoung girl chronicling her experience on the trail inwhich she described her moral dilemma of who shouldtake the last of the quinine medicine when she and heryounger sister were both ill. Having chronicled theirown experiences on the trail, the girls were interestedin reading an authentic diary. The subject of the diaryentry provided the staff and youth an opportunity todialogue about the moral dilemma facing the girls andexamine what they might have or have not done giventhe same situation.

Creating Supportive Connections

The United States Departments of Agriculture (Family,4-H, and Nutrition) and Army created a collaborationcalled the Army/USDA School-Age and Teen (ASA&T)Project to enhance the youth development experiencesfor the youth on Army installations. Computer labsaccessible to school-age children and teens are an integral part of the project. This project created a Computer Lab Operations Manual for School-Age andYouth Services staff but is available to the public at<www.USDA-Army-asat.org>. Barbara Brown, school-age coordinator, says: ÒThis manual instructs staff on how to create computer labs that foster positiveyouth development. A list of approved software isincluded in this manual as well as a tool for evaluatingsoftware.Ó

Youth on installations created home pages describingactivities, opportunities, schools, and other topics of

educational technologist with the Missouri 4-H YouthDevelopment Program, states: ÒThis project helpsyouth who do not have computers at home have moreopportunities to learn with and about computers. Mostelementary and middle school-aged youth only haveone to two hours per week working with computersduring school time. Increasing access to computers during out of school times allows youth to spend recreational time learning about math, science, geogra-phy, and other academic topics.Ó

Non-Formal Educational Settings

The purpose of this article is to provide examples ofcreative use of technology programs are using withschool-age youth in non-formal educational settingsÑ after-school care; computer labs at community centers; or other youth group settings such as 4-H,Scouts, or Campfire Boys and Girls. Such settings pro-vide opportunities for youth to participate voluntarilyand to follow their interests. As a result, a very posi-tive interaction occurs among the youth, staff, andvolunteers who become a community of learners.

Increasing Access to Computer Technology

Another twist on increasing access to computers is toopen computer labs located in the schools during theout of school hours. Missouri 4-H Youth DevelopmentPrograms and the Missouri Department of Elemen-tary and Secondary Education are working togetherto help middle schools create community learningcenters. This is the same concept of the 21st CenturyLearning Centers of the United States Department ofEducation. ÒThere are three critical elements to creat-ing a successful computer lab experience for school-age youth,Ó states Alison Copeland, the projectdirector with Missouri 4-H. ÒEasy access to the com-puter lab is essential for youth and families. Qualitysoftware (see <www.nnst.org> for a Software Selection

Guide published by the National Network for Scienceand Technology of the Cooperative Extension System)and educational and technical support for both thehardware and software keeps problems to a minimumand enhances the learning experiences for the youthand family members.Ó

Enhancing the Learning Experience

At Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, the School-Age Services(SAS) program theme for last yearÕs summer programwas The Oregon Trail. The trek of settler families takingthe Oregon Trail West began at Fort Leavenworth,

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 58

Be

gin

nin

gs

Wo

rksh

op

References

Wright, J. L. (1994). Listen to the children: Observingyoung childrenÕs discoveries with the microcomputer.In J. L. Wright and D. D. Shade (editors), Young children:Active learners in a technological age. Washington, DC:National Association for the Education of YoungChildren, 3-17.

Lemerise, T. (1993). Piaget, Vygotsky, and Logo. TheComputing Teaching, 24-28.

interest to youth. As youth move from post to post,they can learn about their new location prior to arriv-ing by browsing these home pages. The technologicallink allows youth and staff to proactively reach out tothe youth prior to and at arrival to welcome them tothe community. This helps the families make morepositive transitions to a new location.

Taking Time to Explore the Technology

An eclectic collection of sounds were emanating fromthe computer lab. Animal sounds could be heard fromsome machines, music from others. The whoosh of jetscame from the machines with aerospace software. Whowas creating all this noise? Ñ participants at theNational School-Age Child Care Alliance annual con-ference. Participants spent an average of an hour and ahalf at the lab. Many indicated that this was the firsttime they had the opportunity to explore the software.

Researchers emphasize the importance of hands-onexperience to create an in-depth knowledge ofprograms (Wright, 1994). Such knowledge wouldenable the educator to use the program to enhance theeducational program. Providing youth with open-ended projects rather than free exploration was foundto increase the interest of children to actively seekmultiple ways to solve the task (Lemerise, 1993).

And the Children Shall Lead

Another school of thought to overcome barriers to usetechnology, educational software, and the World WideWeb is to develop a community of learners. The youthparticipants become the teachers of the adults andother youth. The adults become collaborators with thestudents. In this environment, youth are not sittingalone at the computers under the silent watchful eye of a teacher-manager. The educator is interactive,helping youth interpret and create meaning out of theinformation.

Beyond a Print-Base Paradigm

To effectively create this community learning environ-ment of youth and adults, the emphasis needs to betaken off the technology and shifted to the informationit accesses for the youth, educators, and parents. Muchas we teach children to read and write to access infor-mation, we need to be thinking about using computersand the Web resources as tools of access. This is think-ing beyond a print-based paradigm for communication.Information and communication technology shouldbecome as integral a part of our lifestyle as a means ofmeaningful inquiry as a dictionary, encyclopedia, orcalculator.

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 59

Be

gin

nin

gs W

ork

sho

p

for young children should take into account bothaspects of content. A good range of software for youngchildren should ideally include content from manydomains of childrenÕs learning Ñ language arts, mathe-matics, science, social learning, visual arts, music, andmotor development.

For some domains of young childrenÕs learning, com-puters offer a very limited amount of content. Exceptfor the coordination involved in moving and clicking amouse, computers donÕt, as yet, support a particularlywide range of motor activities or motor skill develop-ment. Touch typing is a motor skill that can be learnedwith the help of a computer, but it is inappropriate formost children before second grade.

Computer activities involving visual arts are somewhatlimited as well. Computer displays are two dimen-sional and can only simulate three dimensional views.Computers are also a very restricted medium for visualarts, providing little of the sensory feedback of moretraditional media like paper, canvas, liquid paints, pencils, crayons, and clay. Still, computer generated art is finding many applications in the world today and offers opportunities for artistic exploration anddevelopment.

The traditional subject areas for childrenÕs learning Ñlanguage, mathematics, science, and social studies Ñlend themselves somewhat more readily to computeractivities; and it is here that the greatest number of soft-ware applications designed as aids to childrenÕs learn-ing can be found.

What are the elements of good programs for children?

■ Content strength and multiple levels of challenge.LetÕs start by looking at a software example to under-stand the role that content plays in software evaluation.Millie and Bailey Preschool by Edmark contains contentfrom the domains of language and mathematics. Thelevel of this programÕs content Ñ alphabet letters andletter names, rhyming words, making greeting cardsand simple stories Ñ is a good match for skills andconcepts that develop during the preschool years. Themath content, too Ñ counting and number words, size

With hundreds of titles to choose from, selecting goodcomputer software for young children can be a chal-lenging task. The most basic aim in selecting softwarefor children is that it promote the childÕs learning andpersonal growth. Second, it must attract and hold thechildÕs interest so that he can benefit from whatever the

software has to offer. And, third, it must be safe forthe child to use and not expose the child to damagingor inappropriate material. It is to these three broadaims that we will devote our attention.

The learning of young children is defined not just interms of content: the concepts and skills appropriatefor a given age or stage of development. It is alsodefined in terms of the context for learning: the typeof activity, the amount of creative input required, andconnections to the world around them. Good software

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 60

Be

gin

nin

gs

Wo

rksh

op

by Charles Hohmann

Evaluating and Selecting Software for Children

Charles Hohmann is an educational research psycholo-gist at High/Scope Educational Research Foundationwhere he has directed curriculum development since1972. In addition, he conducts workshops for educatorson computer learning for young children and methodsfor integrating technology in classroom learning. He isthe author of Young Children & Computers and theHigh/Scope BuyerÕs Guide to ChildrenÕs Software.

activity. This is an area where some software designsfall down. Entertainment features can overwhelm thecontent of software activities. Too much music and ani-mation can take away from the childÕs opportunities tointeract if she spends too much of the time waiting forentertainment features to run their course.

■ Supportive use of feedback. One of the powerfulfeatures of computer activities is the capacity of thecomputer to evaluate childrenÕs input and providefeedback. This kind of contingent responsiveness is anessential of good teaching and of effective learningenvironments. How, when, and in what form this feed-back is used constitutes a large measure of the art ofgood instruction, whether from human teachers or incomputer activities. Though it can be said that welearn from our mistakes, any goal-directed activity,like learning, requires a reasonable likelihood of success. Without the prospect of success, children (aswell as adults) become frustrated and will soon giveup and turn to something more rewarding. Childrenare particularly sensitive to failure and this is espe-cially true in the context of computer activities.

Good software programs provide feedback to children (and to parents and teachers) in terms ofprogress toward learning goals and of the quality oraccuracy of childrenÕs input. Progress indicators suchas a small animal climbing to the top of a pole or thefilling in of blanked icons helps to set a completiongoal for computer activities and to signal progress in achieving it. Completing a product requiring acertain number of parts, such as building a mousehouse (from Millie and Bailey Preschool) or selectingcharacter, setting, and actions for a simple story, isanother way of showing progress toward a goal.Allowing a child to exit an activity that has becometoo hard, even if not completed, is essential to limit-ing possible frustration.

Feedback on the accuracy of childrenÕs input to acomputer activity often takes the form of ÒCorrectÓor ÒWay to goÓ responses voiced by the computer. The

voiced feedbackis sometimesaccompaniedby encourage-ment andcorrective feed-back. Encour-agement seeksto keep thechild workingon the problemwith responseslike ÒNo. Try

comparisons, geometric shapes, and shape names Ñare at an appropriate level for the preschool years ofapproximately three to five years old. The fact that thelanguage and math content stands in the forefront ofthe Millie and Bailey Preschool activities gives this pro-gram good content strength.

Software with good content strength has not only anappropriate level of content but also presents the con-tent in multiple levels and has room for children togrow. Good software provides an appropriate entrylevel for starting an activity as well as increasing levelsof challenge. In Millie and Bailey Preschool, many of theactivities have several levels of difficulty to choosefrom.

LetÕs look at thecontext of theMillie and BaileyPreschoolcontent. The programÕsactivities ÑÒKid Cards,Ó inwhich childrencreate and printtheir own greet-ing cards, ÒMouse House,Ó where children construct ahouse or other building from geometric shapes, andÒRead-A- Rhyme,Ó where children create mad-librhymes Ñ put the learning content in a constructivereal-world context. Allowing constructive input bothpromotes learning and motivates involvement. Goodsoftware provides constructive involvement for chil-dren. Computer activities that encourage constructiveinvolvement engage children in problem solving situa-tions, stimulate thinking, and put content in the richestand most memorable context possible. Short-answerdrill activities tend to be most limiting of constructiveinvolvement.

■ Attracting and holding childrenÕs attention. Even if the content of a software program is strong with multiple and age-appropriate levels, itÕs value in termsof learning will be limited unless a child is motivatedto spend a reasonable amount of time in the activities.Good software with appropriate content should beable to attract and sustain the involvement of pre-school and kindergarten aged children for about tenminutes or more per session and to motivate repeatedsessions over a period of weeks, months, or longer.

Software designers also use a variety of entertainmentfeatures to make software activities attractive: memo-rable characters, colorful graphics, animations, sounds,and music, as well as fast moving overall pacing of the

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 61

Be

gin

nin

gs W

ork

sho

p

■ Value. A large number of computer activities for alow price can still be a poor value if the software isweak in the terms we have been describing. Most chil-drenÕs software containing three or more activities andpackaged on CD-ROM will cost in the range of $30 to$50. It is possible that a program with a single pro-gram can be worth a price of $100 or more if it meets aparticular need and does so very well Ñ voice recogni-tion software for a child with limited manual dexterity,for example, or a multimedia encyclopedia. If the soft-ware has good content of appropriate levels, has goodfeedback and adult options, is easy to use, and sustainschildrenÕs involvement, it is likely to be a good value.

Resources for Evaluating and Selecting Software

References cited contain additional information aboutselecting childrenÕs software. In addition, several Internet sites with information about childrenÕs soft-ware are listed below.

■ Children’s Software Information on the Internet

ChildrenÕs Software Revue (also in print and on AOL)<www.childrenssoftware.com>

High/ScopeÕs Recommended Software for Children<www.highscope.org>

NewsweekÕs ParentÕs Guide to ChildrenÕs Software<www.newsweekparentsguide.com>

School House Software Reviews<www.worldvillage.com>

SuperKids Educational Software Review<www.superkids.com>

Thunderbeam<www.thunderbeam.com>

■ References

Buckleitner, W. (editor) (1998). ChildrenÕs Software Revue,May/June. Flemington, NJ: Active Learning Associ-ates.

Haugland, S., and Wright, J. (1997) Young children andtechnology, Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Hohmann, C., McCabe-Branz, C., and Carmody, B.(1996). The High/Scope buyerÕs guide to childrenÕs software.Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press.

again.Ó Corrective feedback allows several tries, whilereducing the range of possible responses, to guide thechild to a correct solution. In the best cases, softwareactivities with right and wrong responses include situa-tions with more than one right answer Ñ a sophisticatedreflection of real-world complexity. (See, for example,SammyÕs Science House by Edmark.)

Success and the positive feedback that accompanies itcan be very stimulating and can motivate a childÕs con-tinued involvement with a software activity. However,such feedback can be of limited value if it causes chil-dren to select and repeat activities that they have alreadythoroughly learned, so that they are simply repeating

what they already know. Good software can help avoidthis by tracking the success rate of its user(s) and mov-ing on to new topics and levels of challenge automati-cally when a high level of accuracy is attained in anyparticular area. Good software includes features tomanage the sequencing of learning, as well as addi-tional learning options that can be set by adults.

Certain kinds of software, such as creative environ-ments for writing, drawing, and painting, do not lendthemselves to feedback on childrenÕs accuracy mainlybecause evaluating creative products involves so many different dimensions and can be quite complex.Creative software tools do, however, often allow children to print products that can be shared with others and can serve as evidence of a childÕs work from independent computer use.

■ Avoiding bias, violence, and inappropriate con-tent. We want to be sure that software does not involveviolent or abusive content. Good software should pro-mote prosocial behaviors and tolerant social attitudes.Good software, like good childrenÕs literature, shouldpromote balanced gender roles and positive role models. In addition, any childrenÕs software thatallows children Internet access should include safe-guards that direct children to appropriate Internet sites and prevent access to sites that may contain

inappropriate material.

■ Ease of use. Computers are complex electronicdevices Ñ still more complex and confusing to set upand use than many people would like. To make com-puter activities suitable for children, many efforts havebeen taken to overcome the inherent complexity of com-puters and to make computer activities for children easyto use. Choices should be easy to make, and the childshould be able to stop an activity when he wishes tochange to a different portion of the program. Multi-media computers use voice sounds to guide children tooyoung to read and provide simple icons to allow chil-dren to navigate from one part of a program to another.

Child Care Information Exchange 9/98 — 62

Be

gin

nin

gs

Wo

rksh

op

![ñ,] .Çw* .MÏ ÄÀ ñ,] .Çw* .MÏ ÄÀ ñ, ] . w* .MÏ ÄÀ](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/618d896376628a0d9504af5b/-w-m-w.jpg)

![Den konturlösa borgaren Mukhtar-Landgren, Dalia; Gundnäs ...lup.lub.lu.se/search/ws/files/4823391/772539.pdf · §í 1 -]Ñ ,]Ñ 1 / , , Ñ" Ñ7, ° È Ó i Ñ Ñ°Å `Þ Ó i Ѳ](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5f04b1bf7e708231d40f3de3/den-konturlsa-borgaren-mukhtar-landgren-dalia-gundns-luplublusesearchwsfiles4823391.jpg)