Yen for Global Growth

-

Upload

ashish-patodia -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of Yen for Global Growth

-

7/31/2019 Yen for Global Growth

1/7

An appreciating yen and a stagnant domesticmarket make global expansion a logical move forJapanese companies with bold growth aspi-rations. Indeed, Japanese companies are makinginternational forays, albeit quietly: it is a little-reported fact that the number of outbound M&A

deals in Japan has been on an upward trajectory inrecent years. If the trend continues, Japanesecross-border M&A activity will soon surpass its1990 peak.

Deal levels would be even higher if Japanesecompanies were not haunted by past M&A failures.Pitfalls abound along the road to internationalM&A, and although some of them are now

well-known and thus studiously circumvented,othersparticularly those having to do withfundamental differences in business and manage-ment cultureseem almost impossible forJapanese companies to avoid. Retaining foreigntalent presents a particular challenge.

To gain insights into how Japanese companiesshould manage international acquisitions,

we interviewed non-Japanese executives whosecompanies have been acquired by Japanesecompanies in large cross-border M&A deals withinthe past decade. We also conducted in-depthoutside-in analyses on a handful of deals in whichJapanese companiessuch as Hitachi

Keiko Honda,

Keith Lostaglio, and

Genki Oka

A yen for global growth: TheJapanese experience in cross-border M&A

Japanese companies have embarked on an increasing number of international

acquisitions in recent years. Can they learn from past failures and create value fromcross-border deals?

A U G U S T 2 0 1 2

c o r p o r a t e f i n a n c e p r a c t i c e

-

7/31/2019 Yen for Global Growth

2/7

2

Construction Machinery, Suzuki Motors, TakedaPharmaceuticals, and Toshibawere able to boostinternational sales through cross-border M&A. 1

Our ndings indicate that there is no silver-bulletapproach to capturing the greatest value froman international acquisition. Companies have hadsuccess using a variety of approaches, eachtailored to the acquirers strategic intentions, itsunique characteristics, and the dynamics of the industry. Although a companys particularindustry, context, and objectives should dictate thespeci c tactics it uses, the approaches we studiedcan give acquirers a starting point to consider whether that star ting point entails focusing on onesuch tactic or emulating all of them.

Perspectives of the acquired

Most Japanese executives who have played theglobal M&A game are familiar with the mostcommon obstacles: disagreement between theacquirer and the acquired over how much value ought to be captured immediately after thedeal closes or the positioning of the new sub-sidiary within the parent company, assumptions by Japanese leaders that what works for theircompany must also work elsewhere, inattentionto the acquired companys employees, anda lack of postacquisition-management leadershipand skills.

What may be less familiarand even surpr isingto them are the observations of executivesat US and European companies that have beenacquired by Japanese companies. Interviews with executives from six such companies of varioussizes (from $200 million to $1 billion in value)indicate a number of stumbling blocks. The rstfour, in particular, are detrimental to talentretention; they are the main reasons that non-

Japanese executives do not stay long at suchcompanies.

A hands-o approach. Although Japaneseexecutives may think the acquired company wouldprefer to be left aloneand although the parentcompanys restraint may at rst appear admirableand wisemany foreign executives come to feelthat this is the wrong approach. One major bene tof being acquired, they say, should be that thesubsidiary can fully leverage the capabilities of itsparent company. Foreign executives want theacquirer to engage with its new subsidiary and jointly tackle issues as they arise.

An ambiguous power structure. Non-Japaneseexecutives have dif culty determining wherethe true power lies within a Japanese organization.For example, the deal executive in an M&A situation could have a lofty title (such as seniormanaging director). The target company mighttherefore focus on building a relationship with thisperson, continue to interact with him after theacquisition, and belatedly discover that he actually has no direct reports and no in uence over day- to-day business. In one case, the deal executive waskept on staff only because he was a favorite of the former CEO.

The tyranny o the middle. Our interviewees saidthat middle managers at the parent company

can be destructive forces: they derive power fromtheir proximity to the Japanese CEO and try to control information. A common example: if theacquired company requests additional capitalinvestment for growth, middle managers may choose not to raise this request to the CEO. Whenthe leaders of the acquired company follow up

with the CEO a few months later, they learn thatthe CEO was never informed of the request.

-

7/31/2019 Yen for Global Growth

3/7

33

Incidents such as this can cause middle manage-ment to lose the respect of line leaders at theacquired company.

The glass ceiling or oreigners. Japanesecompanies often have an insular culture. Thegeneral assumption is that a foreigner can rise only so high in the organization. Foreign executivesthus consider leaving not because of unsatisfactory compensation but because they feel their careersare unfairly capped.

Detail orientation. American and Europeanexecutives have dif culty understanding Japaneseattention to detail. A Japanese companys due-diligence checklist, for example, is typically threetimes longer than that of an acquisition-savvy

Western company, in part due to Japanese com-panies risk aversion. In a postacquisitionsetting, a Japanese company would want to under-stand, for instance, the discrepancy between asales forecast and actual sales. It could very welldecide to investigate assumptions made a yearago, whereas a Western company would care only about the actual sales gure and how to improve it.

Poor postacquisition planning. Attention to detailnotwithstanding, Japanese companies tend to be laissez-faire about what happens immediately after a deal closes. They do not see value increating a concrete architecture in the interim to

ensure a successful transition. Foreign executivesoften lament that transition governance andinterim processes for decision making, resourceallocation, and escalation of business-criticalissues are insuf ciently discussed.

Sudden metamorphosis rom riendly partner to

distant boss. Our interviewees reported severalexperiences in which the initial integration phase was friendly and collaborative, then abruptly

morphed into an intense discussion aboutsteep cost reduction. Although this happens in non-Japanese settings as well, it is particularly pronounced in Japanese M&A because Japanese buyers can be extremely politeto a pointthat foreigners sometimes nd misleading. Inone case, even though the acquirer had already decided to eliminate the target companys researchdepartment, executives still made multiple visitsto the targets research sites to keep up appearances.

When employees at the target company learnedthat the decision was made months ago, their trustin the parent company crumbled.

Four approaches

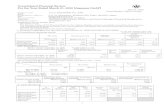

To nd out how Japanese companies haveaddressed one or more of these pitfalls, we examinedthe approach of the very small number of com-panies14, to be exactthat completed at least

ve acquisitions during the past decade and generatemore than half their revenues from overseasmarkets. In each of the deals we examined, theacquirer used a different postacquisition approachdepending on the focus of the change program(exhibit). The approaches are not mutually exclusive. A company can emulate elements fromall of them, depending on its particular industry,context, and objectives.

Establishing mentorship or exchange programs

to build leadership talent

For acquirers whose main objectives includeleadership development, one tactic involves pairinghigh-potential managers from the acquiredcompany with an executive from the parent com-pany as a coach and mentor. This helps buildalignment between the acquirer and the acquired.The frequent and direct communication betweenleaders at both entitieswithout having togo through middle managementalso allows fortighter coordination.

-

7/31/2019 Yen for Global Growth

4/7

4

When in 2002 Japanese automaker SuzukiMotor acquired a majority stake of Indian company Maruti Udyog, Suzuki engineered change atthe top. It appointed a Suzuki executive as presidentand CEO of Maruti and took over 6 of the 11 boardseats. But it also promoted four high-potentialMaruti leadersin sales, marketing, R&D,and administrationto corporate-of cer roles andassigned each a functional executive fromSuzuki as a mentor. The pairs were held jointly accountable for formulating new strategies. If postacquisition performance is any indication, thementorship program has worked: Marutis saleshave quadrupled, and pro ts are up 17 times from2002 levels.

Exhibit Japanese acquirers used four types of postacquisition

change programs.

Focus of change Management approach

Top management

Division

Front line

Entire organization

Establish mentorship/exchange programs to build leadership talent Pair local high-potential managers with executives from parent company

for one-on-one coaching Facilitate mutual exchange of senior-management members

Create a special coordination unit at the division level Assemble a large team drawing from both parent and acquired company Convene a small team for intervention chosen by parent company

Develop local trainers as change agents Provide training by the parent company to create trainers at the

acquired company

Implement company-wide culture-infusion programs Establish mechanisms that model the parent companys values and conduct

Another promising tact ic is two-way dispatch of executives (from acquirer to target and vice versa).

When Takeda acquired US pharmaceuticalcompany Millennium in 2008, it engineered anexchange of personnel to facilitate mutualunderstanding of corporate cultures. It invitedMillenniums CEO to join Takedas manage-ment team. Researchers from both companiestraveled between Japan and the United States tostrengthen their research capabilities. In 2011,Takeda transferred several Millennium researchersto its new research center in Japan. And Takedarecently named Millenniums head of strategya

Westerneras head of business developmentfor Takeda, showing the companys openness to

-

7/31/2019 Yen for Global Growth

5/7

5

high-potential leaders from its subsidiary. Thanksto Millennium, which has been put in charge of all oncology efforts at Takeda, the company is now preparing to begin trials of three or four cancer-drug candidates per yeara signi cant increasefrom historical levels.

These talent-development programs signalto foreign executives that the parent company is will ing to invest in their professional advance-ment, giving them con dence that they can break through the perceived glass ceiling.

Creating a special coordination unit at the

division level Another model entails the creation of a dedicatedcoordination of ce or unit to manage theintegration. Depending on the companys objective,the unit can be large or small. A large coordi-nation of ce may make sense if there is a strong

appetite for capturing value from cost synergies(by streamlining operations) and revenue synergies(by launching new initiatives that leverage bothcompanies strengths). If the goal is intervention inone or two functions, a smaller, SWAT-typeteam may be more apt. In either case, the modelhelps avoid a leadership gap in postacquisitionmanagement. With a dedicated team, there is noquestion as to who is leading the integration effort.

Toshiba acquired US-based Westinghouse Electricin 2006 to raise Toshibas global presence innuclear generation. Toshiba sought to in uence

Westinghouse while also allowing it a degreeof autonomywhich was critical, since the twocompanies had different types of nuclear tech-nology. Toshiba set up two coordination of ces: one within Westinghouse, whose members weredrawn from Toshiba and its strategic partners Shaw Group and IHI (both of which had minority stakes in Westinghouse), and another withinToshiba. The of ces worked together on strategy development and implementation. Three yearslater, Toshiba had record orders, including its rstUS orders for two large-scale projects.

Hitachi Construction Machinery took a slightly different tack when it acquired a majority stake inIndian construction-equipment manufacturerTelcon, a joint venture with Tata Motors, in 2010.

With the goal of increasing the quality of Telcons products, Hitachi dispatched seven Hitachiexperts to the Telcon functions that neededfundamental change, such as quality assuranceand product design. This specialist team, which was expanded in 2010, had full authority to direct Telcons performance-improvementefforts and created plans to optimize manufac-turing processes, support services, and

Talent-development programs signal to foreignexecutives that the parent company is willing to investin their professional advancement, giving themcon dence that they can break through the perceivedglass ceiling.

-

7/31/2019 Yen for Global Growth

6/7

6

employee training. By creating a dedicatedteam, a company can begin to build internalskills that will prove useful in subsequentacquisitions. In the best cases, the individualschosen for the coordination of ce are high-potential executives with excellent communicationskills and business savvy.

Developing local trainers as change agents

In the third model, the front line is the focus of change. Employees from the foreign company are brought to Japan for train the trainer sessionsthat are more than a means of technology transferthey also become opportunities to promoteJapanese corporate values and management philo-sophy. These sessions help create a sense of belonging among the acquired employees that can,in turn, lead to greater motivation and higheremployee-retention rates.

When a Japanese manufacturer acquired aSoutheast Asian company in 2006, it became theindustrys second-largest player. The acquirer

was deliberate in how it chose to transfer its tech-nology to its new subsidiary: it abandonedits traditional system of sending senior Japaneseengineers to overseas subsidiaries to serve astrainers. Instead, select employees from theacquired company came to Japan for training, thenreturned to their home countries to train localemployees. Approximately 700 non-Japanese

employees have now undergone training in Japan;60 of them have gone on to further study and been designated expert trainers. Although theJapanese corporation suffered along with therest of the industry during the economic crisis, thecombined company was recently able to beatthe market leader for a high-pro le contractanachievement in which the new subsidiary played a critical role.

By choosing not to dispatch its own employees but rather to bring in employees from theacquired company, Japanese companies can createroom for translation: the change agents at thenew subsidiary come to understand the corporatestrategy and the vision for the integrated entity,and they develop a greater understanding of andappreciation for the technical advantages thateach company offers. These change agents becomeeffective champions of Japanese techniquesand practices.

Implementing company-wide culture-in usion

programs

To infuse Japanese business culture into an acquiredcompany, acquirers can launch initiativesthat differ completely from those preceding themand ensure frequent communication on allfronts (for example, through employee newslettersor town halls). The most effective initiativesappear to be informal mechanisms that modelJapanese norms while also bridging the divide between management and the front line. Company- wide programs, implemented correctly, can helpmotivate and retain target-company employees.

Suzuki, for instance, gave all Maruti employeessuf cient exposure to Suzukis unique way of doing things. It promoted an open corporate culture, which was foreign and jarring in the Indiancontext. Top management and employees eat in

the same cafeteria. Everyone, from the CEOto the factory worker, wears the same uniform to

work. All employeesagain, including theCEOparticipate in morning exercise routines.(Although several Japanese companies holddear the ritual of morning exercises, no others, toour knowledge, have introduced it at a non-Japanese subsidiary.)

-

7/31/2019 Yen for Global Growth

7/7

7

These case examples should give Japaneseexecutives the con dence to venture beyond Japans borders. Our ndings indicate that there are a variety of promising approaches to postacquisitionmanagement and that leaders of Japanesecompanies must develop their own winningapproachsometimes through trial and error andconstant re nement. Their rst step should beto compile a list of acquisition targets that makesense given their strategic intentions. They should then come up with guiding principles anda blueprint for a postacquisition-managementapproach, tailored to their companys strengths andthe key value drivers of the industry. Japanesecompanies canand indeed, if they want to grow,mustgo global.

Keiko Honda ([email protected]) is a director in McKinseys Tokyo o fce, where Keith Lostaglio ([email protected]) and Genki Oka ([email protected]) are partners. Copyright 2012McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

1 We focused on deals in which the acquirer sought partial inte-gration (neither full autonomy for the subsidiary nor a completemerger) since this is a common model applied by Japanesecompanies, many of which do not have the con dence to fully integrate an overseas entity.