woznyj.weebly.comwoznyj.weebly.com/.../civil_war_battle_overview.docx · Web viewA Union fleet,...

Transcript of woznyj.weebly.comwoznyj.weebly.com/.../civil_war_battle_overview.docx · Web viewA Union fleet,...

Fort Sumter

April 12 - 14, 1861

Charleston Harbor, South Carolina

When South Carolina seceded from the Union on December 20, 1860, United States Maj. Robert Anderson and his force of 85 soldiers were positioned at Fort Moultrie near the mouth of Charleston Harbor. On December 26, fearing for the safety of his men, Anderson moved his command to Fort Sumter, an imposing fortification in the middle of the harbor. While politicians and military commanders wrote and screamed about the legality and appropriateness of this provocative move, Anderson’s position became perilous. Just after the inauguration of President Abraham Lincoln on March 4, 1861, Anderson reported that he had only a six week supply of food left in the fort and Confederate patience for a foreign force in its territory was wearing thin.

On Thursday, April 11, 1861, Confederate Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard dispatched aides to Maj. Anderson to demand the fort’s surrender. Anderson refused. The next morning, at 4:30 a.m., Confederate batteries opened fire on Fort Sumter and continued for 34 hours. The Civil War had begun! Anderson did not return the fire for the first two hours. The fort's supply of ammunition was not suited for an equal fight and Anderson lacked fuses for his exploding shells--only solid shot could be used against the Rebel batteries. At about 7:00 A.M., Union Capt. Abner Doubleday, the fort's second in command, was afforded the honor of firing the first shot in defense of the fort.

The firing continued all day, although much less rapidly since the Union fired aimed to conserve ammunition. "The crashing of the shot, the bursting of the shells, the falling of the walls, and the roar of the flames, made a pandemonium of the fort," wrote Doubleday. The fort's large flag staff was struck and the colors fell to the ground and a brave lieutenant, Norman J. Hall, bravely exposed himself to enemy fire as he put the Stars and Stripes back up. That evening, the firing was sporadic with but an occasional round landing on or in Fort Sumter.

On Saturday, April 13, Anderson surrendered the fort. Incredibly, no soldiers were killed in battle. The generous terms of surrender, however, allowed Anderson to perform a 100-gun salute before he and his men evacuated the fort the next day. The salute began at 2:00 P.M. on April 14, but was cut short to 50 guns after an accidental explosion killed one of the gunners and mortally wounded another. Carrying their tattered banner, the men marched out of the fort and boarded a boat that ferried them to the Union ships outside the harbor. They were greeted as heroes on their return to the North.

Winner: CSA

Principal Commanders: Maj. Robert Anderson [USA]; Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard[CSA]

Estimated Casualties: None

Bull Run

First Manassas

July 21, 1861

Fairfax County and Prince William County , Virginia

Though the Civil War began when Confederate troops shelled Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, the war didn’t begin in earnest until the Battle of Bull Run, fought in Virginia just miles from Washington DC, on July 21, 1861. Popular fervor led President Lincoln to push a cautious Brigadier General Irvin McDowell, commander of the Union army in Northern Virginia, to attack the Confederate forces commanded by Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard, which held a relatively strong position along Bull Run, just northeast of Manassas Junction. The goal was to make quick work of the bulk of the Confederate army, open the way to Richmond, the Confederate capital, and end the war.

The morning of July 21st dawned on two generals planning to outflank their opponent’s left. Hindering the success of the Confederate plan were several communication failures and general lack of coordination between units. McDowell’s forces, on the other had, were hampered by an overly complicated plan that required complex synchronization. Constant and repeated delays on the march and effective scouting by the Confederates gave his movements away, and, worst of all Patterson failed to occupy Johnston’s Confederate forces attention in the west. McDowell’s forces began by shelling the Confederates across Bull Run. Others crossed at Sudley Ford and slowly made their way to attack the Confederate left flank. At the same time as Beauregard sent small detachments to handle what he thought was only a distraction, he also sent a larger contingent to execute flanking a flanking movement of his own on the Union left.

Fighting raged throughout the day as Confederate forces were driven back, despite impressive efforts by Colonel Thomas Jackson to hold important high ground at Henry House Hill, earning him the nom de guerre “Stonewall.” Late in the afternoon,

Confederate reinforcements including those arriving by rail from the Shenandoah Valley extended the Confederate line and succeeded in breaking the Union right flank. At the battle’s climax Virginia cavalry under Colonel James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart arrived on the field and charged into a confused mass of New Yorkers, sending them fleetly to the rear. The Federal retreat rapidly deteriorated as narrow bridges, overturned wagons, and heavy artillery fire added to the confusion. The calamitous retreat was further impeded by the hordes of fleeing onlookers who had come down from Washington to enjoy the spectacle. Although victorious, Confederate forces were too disorganized to pursue. By July 22, the shattered Union army reached the safety of Washington. The Battle of Bull Run convinced the Lincoln administration and the North that the Civil War would be a long and costly affair. McDowell was relieved of command of the Union army and replaced by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who set about reorganizing and training the troops

Winner: CSA

Principal Commanders: Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell [US]; Brig. Gen. Joseph E.Johnston and Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard [CS]

Casualties: USA 2,950; CSA 1,750

Fort Donelson

February 11 - 16, 1862 Stewart County, Tennessee

With Kentucky’s decision to not join the Confederacy, southern military leaders were forced to create key defensive positions along the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, south of the Kentucky border. Forts Henry, Heiman, and Donelson were devised to protect western Tennessee from Union forces using the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers as approach avenues. Unfortunately for the Confederacy, there were few good locations to choose from along the two rivers.

Henry Halleck approved Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s plan to move swiftly to attack Fort Henry before Confederate reinforcements could arrive. As Grant’s two divisions began their march south, gunboats under the command of Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote proceeded down river to attack the Confederate forts on the Tennessee. In a swift, violent exchange of gunfire, Forts Heiman and Henry quickly fell to the Union gunboats on February 6, 1862.

Now consolidated around the two former Confederate forts on the Tennessee River, Grant was determined to move quickly on the much larger Fort Donelson, located on the nearby Cumberland River. Grant’s boast that he would capture Donelson by the 8th of February quickly ran into challenges. Poor winter weather, late-arriving reinforcements, and difficulties in moving the ironclads to the Cumberland, all delayed Grant’s departure for Donelson.

Despite being fairly convinced that no earthen fort could withstand the power of the Union gunboats, Confederate Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston allowed the garrison at Fort Donelson to remain and even sent new commanders and reinforcements to the site. On February 11th, Johnston appointed Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd as the commander of Fort Donelson and the surrounding region. 17,000 Confederate soldiers, combined with improved artillery positions and earthworks convinced Floyd that a hasty retreat was unnecessary.

By February 13th, most of Grant’s Union soldiers had arrived in the vicinity of Fort Donelson and had begun to arrange themselves around the landward side of the fort. Several inches of snowfall and a cold winter wind sent shivers through both armies. With Grant’s reinforced army now blocking a landward exit, the Confederate forces knew that they would have to fight their way to freedom.

On February 14, 1862, Foote’s ironclads moved upriver to bombard Fort Donelson. The subsequent duel between Foote’s “Pook Turtles” and the heavy guns at Fort Donelson led to a Union defeat on the Cumberland. Many of Foote’s ironclads were heavily damaged and Foote himself was wounded in the attack. Grant’s soldiers could hear the Confederate cheers as the Union gunboats retreated.

While Grant was now contemplating an extended siege, the Confederate leaders had devised a bold plan to move all the forces they could to the Union right and to force open a path of escape. Early on the morning of February 15th, the Confederate assault struck the Union right and drove it

back from its positions on Dudley’s Hill. Brig. Gen. John McClernand’s division attempted to reform their lines, but the ongoing Rebel attacks continued to drive his forces to the southeast. Disaster loomed for the Union army.

But in what would become one of the oddest and most improbable acts on any Civil War battlefield, Confederate Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow, sensing a complete victory over the Union forces, ordered the attacking force back to their earthworks, thereby abandoning the hard-fought gains of the morning.

Grant, who had hurriedly returned to the front, ordered Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace and McClernand to retake their lost ground and then rode to the Union left to order an attack upon the Confederate works opposite Charles Smith’s division. Grant reasoned, correctly, that the Confederate right must be greatly reduced in strength given the heavy Confederate assault on their left. Smith’s division surged up to the works and overwhelmed the one Confederate regiment holding an extended line. Capturing large stretches of the Confederate earthworks, Smith’s division was stopped only by the onset of darkness.

During the night of the 15th and 16th, Confederate leaders discussed their options. Despite many disagreements, it was determined that surrender was the only viable option for the Confederate army. Generals Floyd and Pillow managed to make various excuses and crossed the river to safety. Lt. Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest, disgusted with the Confederate decision to surrender, took his cavalrymen and escaped down the Charlotte Road. Even with these defections, more than 13,000 Confederate soldiers remained at Donelson.

With a Union attack poised to strike Fort Donelson, the Federal soldiers were surprised to see white flags flying above the Confederate earthworks. Brig. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, now left in command, met with Ulysses S. Grant to determine the terms of surrender. Buckner, who was hoping for generous terms from his old West Point friend, was disappointed to get Grant’s response. “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.” The great Union victory at Fort Donelson, and Grant’s uncompromising demand brought an avalanche of acclaim to the Brig. General from Galena, Ohio.

Winner: USA

Principal Commanders: Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant [US]; Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd[CS] and Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman [CS]

Casualties: USA 3,730; CSA 13,925

Shiloh

Pittsburg Landing

April 6 - 7, 1862

Hardin County, Tennessee

Following fall of Forts Henry and Donelson in February of 1862, the commander of Confederate forces in the West, Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, was compelled to withdraw from Kentucky, and leave much of western and middle Tennessee to the Federals. To prepare for future offensive operations, Johnston marshalled his forces at Corinth, Mississippi—a major transportation center. The Confederate retreat was a welcome surprise to Union commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, whose Army of the Tennessee would need time to prepare for its own offensive along the Tennessee river. Grant's army made camp at Pittsburg Landing where it spent time drilling raw recruits and awaiting reinforcements in the form of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio. Johnston needed to strike Grant at Pittsburg Landing before the two Federal armies could unite.

Aware of Grant's location and strength—and that more Yankees were on the way—Johnston originally planned to attack the unfortified Union position on April 4, but weather and other logistical concerns delayed the attack until April 6. The Confederate's morning assault completely surprised and routed many of the unprepared Northerners. By afternoon, the a few stalwart bands of Federals established a battle line along a sunken road, known as the “Hornets Nest.” After repeated attempts to carry the position, the Rebels pounded the Yankees with massed artillery, and ultimately surrounded them. Later in the day Federals established a defensive line covering Pittsburg Landing, anchored with artillery and augmented by Buell’s men, who had begun to arrive. Fighting continued until after dark, but the Federals held. Though they had successfully driven the Yankees back, there was, however, one significant blow to the Confederate cause on April 6. Johnston had been mortally wounded early during the day and command of the Confederate force fell to Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard.

With the addition of Buell's men, the Federal force of around 40,000 outnumbered Beauregard’s army of fewer than 30,000. Beauregard, however, was unaware of Buell’s arrival. Therefore, when William Nelson’s division of Buell’s army launched an attack at 6:00 am on April 7, Beauregard immediately ordered a counterattack. Though Beauregard's counter thrust was initially successful, Union resistance stiffened and the Confederates were compelled to fall back and regroup. Beauregard ordered a second counterattack, which halted the Federals' advance but ultimately ended in stalemate. By this point, Beauregard realized he was outnumbered and, having already suffered tremendous casualties, broke contact with the Yankees to began a retreat to Corinth.

Winner: USA

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant [US]; Gen. Albert SydneyJohnston [CS]; Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 23,746 total (USA 13,047; CSA 10,699)

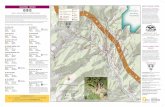

Jackson's Valley Campaign

(March-June 1862)

Maj. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson's Valley Campaign of 1862 is one of the most studied campaigns of military history. This campaign demonstrates how a numerically inferior force can defeat larger forces by fast movement, surprise attack, and intelligent use of the terrain. In March 1862, as a Federal force under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks began to advance cautiously up the Valley, General Jackson retreated to Mount Jackson where he could defend the Valley Turnpike. His task was two-fold--to prevent deep penetration into the Valley and to tie down as many opposing forces as possible. When he learned that Banks was ready to detach part of his force to assist the Army of the Potomac then being concentrated on the Peninsula to threaten Richmond, Jackson marched down the Turnpike and fought the First Battle of Kernstown on March 23.

Although defeated, Jackson's aggressive move convinced Washington that Confederate forces in the Valley posed a real threat to Washington, and Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, with his army preparing to move on Richmond, was denied reinforcements at a critical moment in the Peninsular Campaign.

In late April, Jackson left part of his enlarged command under Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell at Swift Run Gap to confront Banks and marched with about 9,000 men through Staunton to meet a second Union army under Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont, whose vanguard approached on the Parkersburg Road from western Virginia. Banks was convinced that Jackson was leaving the Valley to join the Confederate army at Richmond. But on May 8, Jackson turned up to defeat two brigades of Fremont's force, under Brig. Gens. Robert Milroy and Robert Schenck, at McDowell. Although the Confederates suffered more casualties than their counterparts the Battle of McDowell was a victory for the South.

After a short pursuit of the fleeing Federals, Jackson abruptly turned and marched swiftly back in the heart of the Valley to unite with Ewell against Banks. On May 23, Jackson overran a detached Union force at Front Royal and advanced toward Winchester, threatening to cut off the Union army that was concentrated around Strasburg. After a running battle on the 24th along the Valley Turnpike from Middletown to Newtown (Stephens City), Banks made a stand on the heights south of Winchester. On May 25, Jackson attacked and overwhelmed the Union defenders, who broke and fled in a panic to the Potomac River. Banks was reinforced and again started up the Valley Turnpike, intending to link up with Brig. Gen. James Shields's Union division near Strasburg. Shields's division spearheaded the march of Irwin McDowell's corps recalled from Fredericksburg, while Fremont's army converged on Strasburg from the west. Jackson withdrew, narrowly avoiding being cut off from his line of retreat by these converging columns.

The Union armies now began a three-prong offensive against Jackson. Fremont's troops advanced up the Valley Turnpike while Shields's column marched up the Luray Road along the South Fork. At this point nearly 25,000 men were being brought to bear on Jackson's 17,000. Jackson's cavalry commander, Brig. Gen. Turner Ashby was killed while fighting a rear guard action near Harrisonburg on June 6.

Jackson concentrated his forces near the bridge at Port Republic, situating himself between the two Union columns that were separated by the mountain and the rain-swollen Shenandoah South Fork. On June 8, Fremont attacked Ewell's division at Cross Keys but was driven back. The next morning (June 9), Jackson with his remaining force attacked Shields east and north of Port Republic, while Ewell withdrew from Fremont's front burning the bridge behind him. Ewell joined with Jackson to defeat Shields. Both Union forces retreated north, freeing Jackson's army to reinforce the Confederate army at Richmond.

In five weeks, Jackson's army had marched more than 650 miles and inflicted more than 7,000 casualties, at a cost of only 2,500. More importantly, Jackson's campaign had tied up Union forces three times his strength. Jackson's victories infused new hope and enthusiasm for the Confederate cause, and materially contributed to the defeat of McClellan's campaign against Richmond.

Winner: CSA (Overall)

Principal Commanders: Gen. Stonewall Jackson [CS] and various Union generals

Estimated Casualties: 2,441[CS] 5,735 [US]

Second Manassas

Second Bull Run, Groveton, Brawner's Farm

August 28 - 30, 1862

Prince William County, Virginia

After compelling Union Gen. George B. McClellan to withdraw from the outskirts of Richmond to Harrison’s Landing on the lower James River, Gen. Robert E. Lee turned his attention to the threat posed by the newly formed Union Army of Virginia, under the command of Gen. John Pope. The Lincoln administration had chosen Pope to lead the reorganized forces in northern Virginia with the dual task of shielding Washington and operating northwest of Richmond to take pressure off McClellan’s army. To counter Pope’s movement into central Virginia, Lee sent Gen. T. J. “Stonewall” Jackson to Gordonsville on July 13. Jackson’s force crossed the Rapidan River and clashed with the vanguard of Pope’s army at Cedar Mountain, south of Culpeper, on August 9. Jackson’s narrow tactical victory proved sufficient to instill caution in the Union high command. The initiative shifted to Lee.

Confirming that McClellan’s Army of the Potomac was departing the Virginia Peninsula southeast of Richmond to join forces with Pope in northern Virginia, Lee ordered James Longstreet’s wing of the Army of Northern Virginia to join Jackson. After providing for Richmond’s defense, Lee arrived at Gordonsville on August 15. Lee intended to destroy Pope before the bulk of McClellan’s reinforcements could arrive and bring overwhelming numbers to bear against the Confederates. However, Pope foiled Lee’s plans by withdrawing behind the Rappahannock on August 19.

To draw Pope away from his defensive positions along the Rappahannock, Lee made a daring move. On August 25 he sent Jackson on a sweeping flank march around the Union right to gain its rear and sever Pope’s supply line. At sunset on August 26, Jackson’s forces completed a remarkable 55-mile march, striking the Orange and Alexandria Railroad at Bristoe Station and subsequently capturing Pope’s supply depot at Manassas Junction overnight. As expected, Pope abandoned the Rappahannock line to pursue Jackson, while Lee circled around to bring up Longstreet’s half of the Confederate army. After fending off the advance of Pope’s army near

Bristoe, Jackson torched the remaining Union supplies at Manassas and slipped away, taking up a position north of Groveton, near the old Bull Run battlefield.

Alerted that Lee had reached Thoroughfare Gap and would arrive the following day, Jackson struck a lone Union division on the Warrenton Turnpike, resulting in a fierce engagement at the Brawner Farm on the evening of August 28. Believing that Jackson was attempting to escape, Pope directed his scattered forces to converge on the Confederate position. Throughout the day on August 29, Union forces made piecemeal attacks on Jackson’s line, positioned along an unfinished railroad, while Pope awaited a flanking movement by Fitz John Porter’s command. Although the Union assaults pierced Jackson’s line on several occasions, the attackers were repulsed each time. Late in the morning, Lee arrived on the field with Longstreet’s command taking position on Jackson’s right and blocking Porter’s advance. Lee hoped to unleash Longstreet on the vulnerable Union left, but Longstreet convinced the Confederate commander that circumstances did not favor an attack.

August 30 dawned on a morning of indecision, as Pope confronted conflicting intelligence and weighed his options. Convinced that the Confederates were retreating, the Union commander ordered a pursuit near midday, but the advance quickly ended when skirmishers encountered Jackson’s forces still ensconced behind the unfinished railroad. Pope’s plans now shifted to a major assault on Jackson’s line. Porter’s corps and John Hatch’s division attacked Jackson’s right at the “Deep Cut,” an excavated section of the railroad grade. However, with ample artillery support, the Confederate defenders repulsed the attack.

Lee and Longstreet seized the initiative and launched a massive counterattack against the Union left. Longstreet’s wing, nearly 30,000 strong, swept eastward toward Henry Hill, where the Confederates hoped to cut off Pope’s escape. Union forces mounted a tenacious defense on Chinn Ridge which bought time for Pope to shift enough troops onto Henry Hill and stave off disaster. The Union lines on Henry Hill held as the Confederate counterattack stalled before dusk. After dark, Pope pulled his beaten army off the field and across Bull Run. A final Confederate effort to flank Pope resulted in a bloody fight at Chantilly (Ox Hill) on September 1, hastening the Union retreat toward the Washington defenses. With Union forces in disarray, Lee grasped the opportunity to lead his army across the Potomac into Maryland for its first incursion into the North.

Winner: CSAPrincipal Commanders: Maj. Gen. John Pope [USA]; Gen. Robert E. Lee and Maj. Gen.Thomas J. Jackson [CSA]Estimated Casualties: 22,180 total (USA 13,830; CSA 8,350

Antietam

Sharpsburg

September 16 - 18, 1862

Washington County, Maryland

On September 16, 1862, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan and his Union Army of the Potomac confronted Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Sharpsburg, Maryland. At dawn on September 17, Maj. General Joseph Hooker’s Union corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee’s left flank that began the Battle of Antietam, and the single bloodiest day in American military history. Repeated Union attacks, and equally vicious Confederate counterattacks, swept back and forth across Miller’s cornfield and the West Woods. Despite the great Union numerical advantage, Stonewall Jackson’s forces near the Dunker Church would hold their ground this bloody morning. Meanwhile, towards the center of the battlefield, Union assaults against the Sunken Road would pierce the Confederate center after a terrible struggle for this key defensive position. Unfortunately for the Union army this temporal advantage in the center was not followed up with further advances.

Late in the day, Maj. General Ambrose Burnside’s corps pushed across a bullet-strewn stone bridge over Antietam Creek and with some difficulty managed to imperil the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, A.P. Hill’s division arrived from Harpers Ferry, and counterattacked, driving back Burnside and saving the day for the Army of Northern Virginia. Despite being outnumbered two-to-one, Lee committed his entire force at the Battle of Antietam, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his Federal force. McClellan’s piecemeal approach to the battle failed to fully leverage his superior numbers and allowed Lee to shift forces from threat to threat. During the night, both armies tended to their wounded and consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan on the 18th, while removing his wounded south of the Potomac. McClellan, much to the chagrin of Abraham Lincoln, did not vigorously pursue the wounded Confederate army. While the Battle of Antietam is considered a draw from a military point of view, Abraham Lincoln and the Union claimed victory. This hard-fought battle,

which drove Lee’s forces from Maryland, would give Lincoln the “victory” that he needed before delivering the Emancipation Proclamation — a document that would forever change the geopolitical course of the American Civil War.

Winner: USA (strategic win, CSA left the field)

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan [US]; Gen. Robert E. Lee [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 23,100 total (U.S.A 12,401; C.S.A 10,316)

Perryville

Battle of Chaplin Hills

October 8, 1862

Boyle County, Kentucky

Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg's autumn 1862 invasion of Kentucky had reached the outskirts of Louisville and Cincinnati, but he was forced to retreat and regroup. On October 7, the Federal army of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, numbering nearly 55,000, converged on the small crossroads town of Perryville, Kentucky, in three columns. Union forces first skirmished with Rebel cavalry on the Springfield Pike before the fighting became more general, on Peters Hill, as the grayclad infantry arrived.

The next day, at dawn, fighting began again around Peters Hill as a Union division advanced up the pike, halting just before the Confederate line. The fighting then stopped for a time. After noon, a Confederate division struck the Union left flank and forced it to fall back. When more Confederate divisions joined the fray, the Union line made a stubborn stand, counterattacked, but finally fell back with some troops routed. Buell did not know of the happenings on the field, or he would have sent forward some reserves. Even so, the Union troops on the left flank, reinforced by two brigades, stabilized their line, and the Rebel attack sputtered to a halt.

Later, a Rebel brigade assaulted the Union division on the Springfield Pike but was repulsed and fell back into Perryville. The Yankees pursued, and skirmishing occurred in the streets in the evening before dark. Union reinforcements were threatening the Rebel left flank by now. Bragg, short of men and supplies, withdrew during the night, and, after pausing at Harrodsburg, continued the Confederate retrograde by way of Cumberland Gap into East Tennessee. The Confederate offensive was over, and the Union controlled Kentucky.

Winner: USA (strategic win, CSA left the field)

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell [US]; Gen. Braxton Bragg [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 7,407 total (USA 4,211; CSA 3,196)

Fredericksburg

December 11 - 15, 1862

Fredericksburg, Virginia

The Battle of Fredericksburg, fought December 11-15, 1862, was one of the largest and deadliest of the Civil War. It featured the first major opposed river crossing in American military history. Union and Confederate troops fought in the streets of Fredericksburg, the Civil War’s first urban combat. And with nearly 200,000 combatants, no other Civil War battle featured a larger concentration of soldiers.

Burnside’s plan at Fredericksburg was to use the nearly 60,000 men in Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin’s Left Grand Division to crush Lee’s southern flank on Prospect Hill while the rest of his army held Longstreet and the Confederate First Corps in position at Marye’s Heights.

The Union army’s main assault against Stonewall Jackson produced initial success and held the promise of destroying the Confederate right, but lack of reinforcements and Jackson’s powerful counterattack stymied the effort. Both sides suffered heavy losses (totaling 9,000 in killed, wounded and missing) with no real change in the strategic situation.

In the meantime, Burnside’s “diversion” against veteran Confederate soldiers behind a stone wall produced a similar number of casualties but most of these were suffered by the Union troops. Wave after wave of Federal soldiers marched forth to take the heights, but each was met with devastating rifle and artillery fire from the nearly impregnable Confederate positions. Confederate artillerist Edward Porter Alexander’s earlier claim that “a chicken could not live on that field” proved to be entirely prophetic this bloody day.

As darkness fell on a battlefield strewn with dead and wounded, it was abundantly clear that a signal Confederate victory was at hand. The Army of the Potomac had suffered nearly 13,300 casualties, nearly two-thirds of them in front of Mayre’s Heights. By comparison, Lee’s army had

suffered some 4,500 losses. Robert E. Lee, watching the great Confederate victory unfolding from his hilltop command post exclaimed, “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.”

Roughly six weeks after the Battle of Fredericksburg, President Lincoln removed Burnside from command of the Army of the Potomac.

Winner: CSA

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside [US]; Gen. Robert E. Lee [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 17,929 total (USA 13,353; CSA 4,576)

Stones River

Murfreesboro

December 31 - January 2, 1863

Rutherford County , Tennessee

With morale flagging as the Civil War dragged into its second year, Abraham Lincoln and General-in-Chief Henry Halleck sought to unleash a strategic combination that would produce a decision in the bloody struggle. They sought to take advantage of their material superiority over the South, launching a three-pronged coordinated offensive that would overwhelm the Confederacy's ability to shift reinforcements along its interior lines. As Gen. Ambrose Burnside advanced in Virginia and Gen. Ulysses S. Grant advanced in Mississippi, the responsibility for Tennessee, the strategic central position, fell to Gen. William S. Rosecrans. On December 26, Rosecrans's army left Nashville and marched on Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg's position at Murfreesboro.

The two armies met on a battlefield on the banks of Stones River on the evening of December 30. Both generals formed plans of attack for the next morning while their soldiers uneasily slept on their muskets--in some places the opposing lines were less than four hundred yards apart. On December 31, Bragg's dawn assault struck home before the Union army could form for its own attack. After six hours of savage fighting the Confederates bent the Union line nearly in half, but Gen. Phil Sheridan organized a determined defense in a cedar thicket now known as the "Slaughter Pen" and prevented disaster. Braxton Bragg, seeking to dislodge Sheridan and splinter the line once and for all, spent the afternoon directing a series of assaults on a salient that had formed in the Round Forest, or "Hell's Half-Acre." The Southerners went in piecemeal and were unable to carry woods.

Having inflicted severe damage on the Union army, Bragg spent the day of January 1 waiting for Rosecrans to retreat. When January 2 dawned with Rosecrans still in position, Bragg realized that his own situation was becoming untenable. The Federals had managed to reform into a strong defensive line and they would soon be receiving heavy reinforcements. That afternoon, Bragg ordered Gen. John Breckinridge's division to seize a hill that could function as a deadly artillery platform in the Union rear. Breckinridge objected on the grounds that his men would be advancing across an open field under cannon fire towards a numerically superior foe, but Bragg overruled him. Breckinridge's division was shattered in the determined charge. With no cards left to play, Bragg ordered a retreat.

The Battle of Stones River was a strategic Union victory. The grand offensive had failed to the east (The Battle of Fredericksburg) and west (The Battle of Chickasaw Bayou), but Rosecrans's success in Middle Tennessee reassured the weary Northern public. Braxton Bragg's army spent months paralyzed by an officers' revolt that sought to remove Bragg from command as punishment for his failure at Stones River. When Rosecrans launched his next attack in the summer of 1863, he took

the bickering Confederates by surprise and forced them into Georgia. The Battle of Stones River secured Union control of Middle Tennessee for the remainder of the war.

Winner: USA

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans [US]; Gen. Braxton Bragg [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 23,515 total (US 13,249; CS 10,266)

Chancellorsville

April 30 - May 6, 1863

Spotsylvania County, Virginia

General Ambrose E. Burnside only lasted a single campaign at the head of the Army of the Potomac. His abject failure at Fredericksburg, followed by further fumbling on January's "Mud March," convinced President Abraham Lincoln to make a change.

Hooker's energetic make-over polished the Northern army into tip-top condition, and with more strength than ever before. The army commander outmaneuvered Lee in late April, when the weather finally allowed roads to harden enough for marching.

Swinging far beyond Lee's left, Hooker closed up on the Chancellorsville intersection on the last evening in April. He never managed to escape the clutches of the Wilderness, though—the tangled, brush-choked thickets that covered about 70 square miles around Chancellorsville.

On May 1, Lee hurriedly gathered his army from its far-flung camps across the Old Dominion. He used his regiments to hem the quiescent Hooker into the Wilderness, pushing west along the two primary corridors in the region—the Orange Turnpike and the Orange Plank Road.

That evening Lee and his incomparable lieutenant, Stonewall Jackson, conceived their greatest, and last, collaboration. Early on May 2 Jackson took nearly 30,000 men off on a march that clandestinely crossed the front of the enemy army and swung around behind it. That left Lee with only about 15,000 men to hold off Hooker's army. He managed that formidable task by feigning attacks with a scant line of skirmishers.

Soon after 5 p.m. Jackson, having completed his circuit around the enemy, unleashed his men in an overwhelming attack on Hooker's right flank and rear. They shattered the Federal Eleventh Corps and pushed the Northern army back more than two miles.

When Jackson's men burst out of the thickets screaming the Rebel Yell that afternoon, they dashed across the high-water mark of the Army of Northern Virginia. About three hours later the army suffered a nadir as low as the afternoon's zenith, when Jackson fell mortally wounded by the mistaken fire of his own men.

The long marches, high risks, and veiled stratagems of May 1-2 gave way on the 3rd to a slugging match in the woods on three sides of Chancellorsville intersection. Hooker abandoned key ground in a further display of timidity; Confederate artillery roared from a crucial hilltop, employing a brand-new battalion organization; and Southern infantry doggedly pushed ahead.

When a Confederate artillery round smashed into a pillar against which Hooker was leaning, the Federal leader spent an unconscious half hour. His return to semi-sentience disappointed the veteran corps commanders who had hoped, unencumbered by Hooker, to employ their army's considerable untapped might.

By mid-morning, Southern infantry smashed through the final resistance and united in the Chancellorsville clearing. Their boisterous, well-earned, celebration did not run long: word came from the direction of Fredericksburg that a Northern rearguard had broken through and threatened the rear.

The May 3 Battle of Salem Church, just west of Fredericksburg, halted the threat from the east. Lee went to that zone in person to ensure final success on the 4th, then returned to Chancellorsville to superintend the corralling of Hooker's defeated army.

Hooker re-crossed the Rappahannock River to its left bank, whence he had come, early on May 6. The campaign had cost him about 18,000 casualties, and his enemy about 13,000. None of the losses on either side would resonate as loudly and long as the death of Stonewall Jackson.

Winner: CSA

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker [US]; Gen. Robert E. Lee and Maj. Gen.Thomas J. Jackson [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 24,000 total (US 14,000; CS 10,000)

Gettysburg

July 1 - 3, 1863

Adams County, Pennsylvania

After his astounding victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia, in May 1863, Robert E. Lee led his Army of Northern Virginia in its second invasion of the North—the Gettysburg Campaign. With his army in high spirits, Lee intended to collect supplies in the abundant Pennsylvania farmland and take the fighting away from war-ravaged Virginia. He wanted to threaten Northern cities, weaken the North's appetite for war and, especially, win a major battle on Northern soil and strengthen the peace movement in the North. Prodded by President Abraham Lincoln, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker moved his Union Army of the Potomac in pursuit, but was relieved of command just three days before the battle. Hooker's successor, Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade moved northward, keeping his army between Lee and Washington, D.C. When Lee learned that Meade was in Pennsylvania, Lee concentrated his army around Gettysburg.

Elements of the two armies collided west and north of the town on July 1, 1863. Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. John Buford slowed the Confederate advance until Union infantry, the Union 1st and 11th Corps, arrived. More Confederate reinforcements under generals A.P. Hill and Richard Ewell reached the scene, however, and 30,000 Confederates ultimately defeated 20,000 Yankees, who fell back through Gettysburg to the hills south of town--Cemetery Hill and Culp's Hill.

On the second day of battle, the Union defended a fishhook-shaped range of hills and ridges south of Gettysburg with around 90,000 soldiers. Confederates essentially wrapped around the Union position with 70,000 soldiers. On the afternoon of July 2, Lee launched a heavy assault on the Union left flank, and fierce fighting raged at Devil's Den, Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard and Cemetery Ridge. On the Union right, demonstrations escalated into full-scale assaults on Culp's Hill and East Cemetery Hill. Although

the Confederates gained ground, the Union defenders still held strong positions by the end of the day.

On July 3, fighting resumed on Culp's Hill, and cavalry battles raged to the east and south, but the main event was a dramatic infantry assault by 12,000 Confederates against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge--Pickett's Charge. The charge was repulsed by Union rifle and artillery fire, at great losses to the Confederate army. Lee led his army on a torturous retreat back to Virginia. As many as 51,000 soldiers from both armies were killed, wounded, captured or missing in the three-day battle. Four months after the battle, President Lincoln used the dedication ceremony for Gettysburg's Soldiers National Cemetery to honor the fallen Union soldiers and redefine the purpose of the war in his historic Gettysburg Address.

Winner: USA

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. George G. Meade [US]; Gen. Robert E. Lee [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 51,000 total (US 23,000; CS 28,000)

Vicksburg

May 22, 1863 - Jul 4, 1863

All through traffic on the Mississippi River was controlled by the Confederate fortress at Vicksburg, Mississippi. Situated atop seemingly insurmountable cliffs, the fort and its big guns determined whose men and supplies flowed down the critical water highway.

So well defended by nature and big guns was the fort that Union General Ulysses S. Grant spent more time trying to figure out how to circumvent the fort than attack it. Several schemes involving canals, dredges, and levees were explored; if a new ditch could be dug, Vicksburg could be avoided and Northern military transports could work their way down Ol’ Muddy. But none of these schemes panned out. Grant had no choice but to take Vicksburg if he were to take the Mississippi. And perhaps where modern technology had failed, ancient military tactics could succeed.

Grant began by marching his army down the western bank of the Mississippi well past Vicksburg located on the eastern bank. To cross the river he had no other choice but to order his transport boats to parallel his movement—that is, float past the fort and its deadly accurate guns. Those ships that made it, ferried Grant and his men to the Vicksburg side of the river about 25 miles south of the fort.

Next, Grant marched 50 miles east to Jackson, the state capital, to establish control over the supplies that might be used to restock Vicksburg. For a time, the Confederate commander at Vicksburg, John C. Pemberton, was confused by Grant’s movements and distracted by some diversionary raids order by Grant and led by Col. Benjamin Grierson. But soon enough, Pemberton figured out what was up –Grant was planning to lay siege to his fortress. Caught in something of a Catch-22—afraid to leave Vicksburg undefended but anxious to support the small army engaged in delaying Grant’s progress, Pemberton sent out a small force to help intercept the Union general. But his desperate gambit failed. Pemberton was forced to retreat to the heavily barricaded city with Grant hot on his heels.

Grant, a hard charger by nature, initially tried take the fort by storm, first on 19 May and then again three days later. But after taking heavy casualties, he settled in for a long siege. His 75,000 men easily contained the 30,000 Pemberton had entrenched within the city-fort. Grant’s troops also proved sufficient to fend off General Joe Johnston’s desperate attempt to break Grant’s stranglehold by attacking from the east.

Without reinforcements and without supplies, Pemberton's army and the civilian population of the city faced terrible hardships. To escape the barrage let loose by Union gunboats hovering outside, locals hid in caves. To fend off starvation, they ate anything they could find—by late June all the army’s mules had been stewed. Yet Grant’s grip was relentless, his siege could not be broken. On 4 July 1863—four score and seven years after the Declaration of Independence was read—and one day after Pickett’s charge sent the Confederacy to a devastating defeat at Gettysburg—Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to Grant. The North now controlled the Mississippi.

Winner: USA

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant [US]; Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 19,233 total (US 10,142; CS 9,091)

The Peninsula CampaignFROM HAMPTON ROADS TO SEVEN PINES

By early April 1862, the Army of the Potomac — over 120,000 strong — had been transported to the tip of the Virginia peninsula between the York and James Rivers and was in position to move on the Confederate capital of Richmond. The training was over; this would prove the ultimate test.

Major General George B. McClellan (National Archives) GEORGE BRINTON MCCLELLAN, often fondly called "Little Mac" or the "Young Napoleon," seemed to have the magic touch when he arrived in Washington in August 1861 following the Union debacle at Bull Run. The 34-year old major general, fresh from his victorious campaign in western Virginia, radiated success and quickly transformed the demoralized Army of the Potomac into the most powerful army ever witnessed in America. McClellan provided his troops with the best training, armaments and organization then known to military science and had replaced the aged Winfield Scott as General-in-Chief of the Union army. Yet by late 1861, "Little Mac" had not given any indication of how or when he might strike against the Confederate army nearby at Manassas. President Abraham Lincoln, who purportedly quipped, "If General McClellan and does not intend to use his army, may I borrow it?", pressed the general into presenting some plan of action against the Confederate capital in Richmond. McClellan's response would set in motion one of the war's most pivotal events — the Peninsula Campaign. McClellan believed that Richmond held the fate of the Confederacy, yet he eschewed the notion of marching overland toward the Confederate capital. This direct approach, McClellan rationalized, would enable the Confederates to use their interior lines to develop a defensive concentration, which would result in extensive Union casualties. Instead, the Union general initially purposed an indirect strategic movement whereby he would interdict his army between the Confederate forces arrayed throughout Virginia and Richmond by way of Urbanna, located on the Rappahannock River. Before McClellan could put his plan into motion, General Joseph E. Johnston pulled his Confederate army from Manassas to Fredericksburg on March 7, 1862. Johnston's withdrawal invalidated the strategic strengths of McClellan's Urbanna plan. Nevertheless, the Union general immediately offered a second amphibious operation to strike at Richmond by way of the Virginia Peninsula.

Northern and Southern leaders alike had recognized from the war's onset the Peninsula's strategic position. The Virginia Peninsula, bordered by Hampton Roads and the Chesapeake Bay as well as the James and York Rivers, was one of two major approaches to the Confederate capital at Richmond. Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler was the first Federal commander to try to exploit this avenue of advance against Richmond. Even though Butler's troops blundered their way to defeat during the June 10, 1861 Battle of Big Bethel, Union actions had secured Fort Monroe and Camp Butler on Newport News Point. Fort Monroe, the largest moat-encircled masonry fortification in North America, was the only fort in the Upper South not to fall into Confederate hands and commanded the entrance to Hampton Roads. Even though the Confederates maintained control of Norfolk and Gosport Navy Yard, Fort Monroe became a major base almost overnight for Federal fleet and army operations.

Joe Johnston's retreat ruined the Urbanna Plan's prospects. McClellan thought that by "using Fort Monroe as a base," the Army of the Potomac could march against Richmond "with complete security, altho' with less celebrity and brilliancy of results, up the Peninsula." McClellan's plan was a sound strategic concept as it employed a shrewd exploitation of Union naval superiority; gunboats could protect his flanks and river steamers could carry his troops toward the Confederate capital.

Confederate prospects looked bleak as McClellan moved his massive army to the Peninsula. Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside's troops were finalizing their conquest of eastern North Carolina and Union forces appeared invincible along the Mississippi River. Many Southerners feared that if Richmond were to fall, the Confederacy might collapse. Confederate hopes were pinned on the ability of the C.S.S. Virginia to hold Hampton Roads, and Major General John Bankhead Magruder's small "Army of the Peninsula" to delay the Union juggernaut's advance toward Richmond.

On April 4, 1862, McClellan's army began its march up the Peninsula, occupying abandoned Confederate works at Big Bethel and Young's Mill. The next day, the Army of the Potomac assumed its march only to find its path to Richmond slowed by heavy rains, which turned the already poor roads into a muddy morass. The army then was blocked by Magruder's 13,000-strong command entrenched along a 12-mile front. Brigadier General John G. Barnard, the Army of the Potomac's chief engineer, called the comprehensive series of redoubts and rifle pits arrayed behind the flooded Warwick River "one of the most extensive known to modern times." The Union army halted in its tracks as "Prince John" Magruder, despite being heavily outnumbered, created an illusion of a powerful army. He "played his ten thousand before McClellan like fireflies," wrote diarist Mary Chesnut, "and utterly deluded him."

The events of April 5 changed McClellan's campaign. Not only were his plans for a rapid movement past Yorktown upset by the unexpected Confederate defenses along the Warwick River, but also by Lincoln's decision not to release Irwin McDowell's I Corps to his use in a flanking movement against the Southern fortifications at Gloucester Point. Lincoln feared for Washington's safety and held McDowell near the Federal capital. The U. S. Navy, too, refused to support McClellan's advance. Flag Officer Louis Goldsborough thought that the C.S. S. Virginia might attack the Union fleet while it attempted to silence the Confederate guns at Yorktown and Gloucester Point. Since McClellan's reconnaissance, provided by detective Alan Pinkerton and Professor Thaddeus Lowe's balloons, confirmed his belief that he was outnumbered by the Confederates, he besieged their defenses.

As McClellan's men built gun emplacements for the 103 siege guns he brought to the Peninsula, General Joseph E. Johnston began moving his entire Confederate army to the lower Peninsula. Johnston thought the Confederate position was weak, noting that, "no one but McClellan could have hesitated to attack." McClellan's men did make one attempt to break the midpoint of the Confederate line. Brigadier General William F. "Baldy" Smith sent soldiers of the Vermont Brigade across the Warwick River to disrupt Confederate control of Dam No. 1. The poorly coordinated and supported assaults on April 16, 1862, failed to break through this Confederate weak point.

The siege continued another two weeks even though Johnston counseled retreat. Johnston advised that "the fight for Yorktown must be one of artillery, in which we cannot win. The result is certain; the time only doubtful." Finally, just as McClellan made his last preparations to unleash his heavy bombardment on the Confederate lines, Johnston abandoned the fortifications during the evening of May 3.

Lincoln, disenchanted with what he deemed McClellan's general lack of initiative, arrived at Fort Monroe May 6. Since the Confederate army was now in retreat toward Richmond, Lincoln sought to open the James River to the Union's use. The only obstacle was the C.S.S. Virginia.

The Confederate retreat from the lower Peninsula exposed the port city of Norfolk to Union capture. Lincoln directed Flag Officer Louis N. Goldsborough and Major General John E. Wool to end the Virginia's control of Hampton Roads by occupying its base. Major General Benjamin Huger, threatened by the Union advance, was forced to abandon the port city on May 9. Without its base, the ironclad's deep draught made the vessel unable to steam up the James to Richmond. Consequently, the Virginia was destroyed by its crew off Craney Island on May 11, 1862. "Still unconquered, we hauled down our drooping colors ... and with mingled pride and grief gave her to the flames," Chief Engineer Ashton Ramsay reflected. The door to the Confederate capital via the James River now lay open. A Union fleet, including the ironclads Galena and Monitor; slowly moved up the river to within seven miles of Richmond. On May 15, 1862, hastily constructed Confederate batteries perched atop Drewry's Bluff repelled the Union naval advance. Obstructions limited the mobility of Federal vessels as plunging shot from Confederate cannons severely damaged the Galena.

Despite the repulse given to the Federal fleet's thrust up the James River, McClellan's army neared the outskirts of the Confederate capital by the end of May. McClellan had established a major supply base near West Point and appeared ready to invest Richmond with his siege artillery. However, his delays on the lower Peninsula once again altered his plans. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's operations in the Shenandoah Valley threatened Washington, prompting Lincoln to continue to withhold McDowell's Corps at Fredericksburg. McClellan, extending his right flank to meet the expected reinforcements, found his army divided by the swampy Chickahominy River.

Taking advantage of heavy rains, which made the Chickahominy nearly impassable, Johnston attacked McClellan's army south of the river at Seven Pines/Fair Oaks. The poorly coordinated assaults on May 31 failed to destroy the exposed Union corps. Johnston was seriously wounded riding across the battlefield. The next day, June 1, 1862, Robert E. Lee assumed command of the Confederate forces around Richmond.

The Southern assaults at Seven Pines confirmed McClellan's opinion that his army was outnumbered. Rather than striking directly at the city, his primary goal was to reach Old Tavern on the Nine Mile Road and entrench. He was confident a classic siege would result in Richmond's capture. Lee, formerly Jefferson Davis's military advisor, recognized McClellan's siege mentality and transformed the sluggish, yet seemingly victorious Union advance into a vicious Confederate counteroffensive, known as the Seven Days' Battles. Lee's offensive, although costly in men, achieved its objective — Richmond was saved.