World Trade Trends

-

Upload

lovleshruby -

Category

Documents

-

view

17 -

download

1

description

Transcript of World Trade Trends

INTRODUCTION

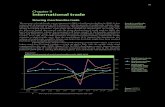

The volume of world merchandise trade rose 5.0 per cent in 2011, accompanied by global output

growth of 2.4 per cent. This marked a significant slowdown from 2010, when trade advanced 13.8

per cent and output expanded by 3.8 per cent (see Figure 1.1).1 Slower growth in both trade and

output had been anticipated for 2011, but multiple economic shocks held back economic activity and

trade during the year.

The earthquake, tsunami and nuclear incident that hit Japan in March sharply depressed the country's

exports in the second quarter, while flooding in Thailand reduced the supply of key parts and

components in the fourth quarter and further distorted global production networks. Turmoil in North

African countries took a toll on the region's exports, especially in Libya, where oil production and

exports plunged. Finally, negative gross domestic product (GDP) growth

in the European Union reduced demand for imported goods in the fourth quarter as the euro

sovereign debt crisis came to a head.

The sluggish pace of economic growth in 2011 reduced import demand in the largest economies and

resulted in global export growth below the WTO's forecast of 5.8 per cent. Japan's output contracted

in the fourth quarter after recording just one-quarter of expansion on the year in the third quarter.

Even China’s dynamic economy appeared to be slowing towards the end of the year as its fourth

quarter GDP growth slipped to an annualized rate of 7.8 per cent after averaging around 9.5 per cent

over the first three quarters, according to data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

Economic indicators improved in the United States in the closing months of 2011 as output growth

accelerated to 3.0 per cent annualized in the fourth quarter and unemployment fell to 8.3 per cent in

December according to data from the OECD, but this only partly made up for earlier setbacks.

Developed economies exceeded expectations with export growth of 4.7 per cent in 2011 while

developing economies (for the purposes of the analysis, this includes the Commonwealth of

Independent States, or CIS) did worse than expected, recording an increase of just 5.4 per cent. In

fact, shipments from developing economies other than China grew at a slightly slower pace than

exports from developed economies (including disaster-struck Japan). The relatively strong

performance of developed economies was driven by a robust 7.2 per cent increase in exports from

the United States, as well as a 5.0 per cent expansion in exports from the European Union.

Meanwhile, Japan's 0.5 per cent drop in exports detracted from the average for developed economies

overall.

Several adverse developments disproportionately affected developing economies, including the

interruption of oil supplies from Libya that caused African exports to tumble 8 per cent in 2011, and

the severe flooding that hit Thailand in the fourth quarter. The Japanese earthquake and tsunami also

disrupted global supply chains, which penalized exports from developing countries such as China, as

reduced shipments of components hindered production of goods for export (see quarterly volume

developments for selected economies in Appendix Figure 1).

Significant exchange rate fluctuations occurred during 2011, which shifted the competitive positions

of some major traders and prompted policy responses (e.g. in Switzerland and Brazil). Fluctuations

were driven in large part by attitudes towards risk related to the euro sovereign debt crisis. The value

of the US dollar fell 4.6 per cent in nominal terms against a broad basket of currencies according to

data from the Federal Reserve, and 4.9 per cent in real terms according to data from the International

Monetary Fund, making US goods generally less expensive for export. Nominal US dollar

depreciation also would have inflated the dollar values of some international transactions.

The developments outlined above refer to trade in real (i.e. volume) terms, but nominal flows (i.e. in

currency terms) for both merchandise and commercial services were similarly affected by recent

economic shocks. In 2011, the dollar value of world merchandise trade advanced 19 per cent to US$

18.2 trillion, surpassing the previous peak of US$ 16.1 trillion in 2008. Much of

the growth was due to higher commodity prices, but monthly trade flows were mostly flat or

declining in many major traders over the course of the year (see monthly nominal developments in

Appendix Figure 2). The share of developing economies and the CIS in theworld total also rose to 47

per cent on the export side and 42 per cent on the import side, the highest levels ever recorded in a

data series extending back to 1948.

The value of world commercial services exports increased by 11 per cent in 2011 to US$ 4.2 trillion,

with strong differences in annual growth rates for particular countries and regions. African exports

were hit hard by the turmoil in Arab countries, recording zero growth as Egypt’s exports of travel

services plunged more than 30 per cent. Quarterly data on services jointly prepared by the WTO and

the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) also showed a sharp

slowdown in the fourth quarter, coinciding with the heightened level of financial market turmoil

surrounding the euro debt crisis.

The 5.0 per cent growth of world merchandise trade in 2011 was below the pre-crisis average of 6.0

per cent for 1990–2008, and was even below the average of the last 20 years, including the period of

the trade collapse (5.4 per cent). As a result, trade volume of world trade was even further away

from its pre-crisis trend at the end of 2011 than it was a year earlier. In fact, this gap should continue

to increase as long as the rate of trade expansion falls short of earlier levels (see Figure 1.2).

Eliminating this divergence would require faster than average growth at some point in the future.

Conceivably, this could happen after governments, businesses and households in developed

countries reduce their debt burdens to more manageable levels, but this process of deleveraging

(reducing reliance on debt) and fiscal consolidation (reducing budget deficits) is likely to take years.

In the meantime, the world may have to resign itself to a long period of slower-than-average growth

in international trade.

STATE OF THE WORLD ECONOMY AND TRADE IN 2011

The rate of world output growth fell to 2.4 per cent in 2011 from 3.8 per cent in the previous year,

weighed down by the on-going sovereign debt crisis in Europe, supply chain disruptions from

natural disasters in Japan and Thailand, and turmoil in Arab countries. This pace of expansion was

well below the 3.2 per cent average over the 20 years leading up to the financial

crisis in 2008 (see Table 1.1).

Japan’s 0.5 per cent contraction in output, brought on by the catastrophic earthquake in March 2011,

contributed to the lacklustre 1.5 per cent growth of developed economies in 2011. Growth of GDP

(total production in the country) in the United States was slightly faster than the average of all

developed economies at 1.7 per cent, while the EU’s rate was in line with the average at 1.5 per cent.

The fastest growing regions were the Middle East at 4.9 per cent, followed by the Commonwealth of

Independent States at 4.6 per cent and South and Central America at 4.5 per cent. Africa, with GDP

growth of 2.3 per cent, might have grown even faster ifnot for the uprisings that occurred in Libya,

Tunisia, Egypt and elsewhere.

Once again, China’s GDP growth outpaced the rest of the world at 9.2 per cent, but this rate was no

better than what the country achieved at the peak of the global financial crisis in 2009. In contrast to

this performance, the newly industrialized economies of Hong Kong, China, of the Republic of

Korea, of Singapore and of Chinese Taipei together grew at less than half the rate of China (4.2 per

cent). Developing economies and the CIS together recorded a 5.7 per cent increase in 2011.

Aggregate quarterly figures for world GDP growth are not readily available, but such growth likely

slowed towards the end of 2011 in the face of headwinds from the European sovereign debt crisis.

Output of the euro area contracted at a 1.3 per cent annual rate in the fourth quarter, marking the first

quarter of negative growth since the currency bloc emerged from recession in 2009 (see Figure 1.3).

At the same time, China’s economy slowed and Japan remained mired in

recession. Growth picked up in the United States in the fourth quarter as unemployment eased, but

thiswas likely outweighed by developments elsewhere.

2.

Merchandise trade in volume (i.e. real) terms

World merchandise trade volume grew 5.0 per cent in 2011, and Asia’s 6.6 per cent increase led all

regions (see Table 1.1). One of the more significant developments in 2011 was the 8.3 per cent

contraction in the volume of Africa’s exports. This was largely due to the civil war in Libya, which

reduced the country’s oil shipments by an estimated 75 per cent. Japan’s exports also fell by the

same 0.5 per cent as the country’s GDP, while shipments from the CIS advanced just 1.8 per cent.

Although Africa recorded a respectable 5.0 per cent increase in imports, other resource-exporting

regions performed better. Imports of the CIS grew faster than those of any other region at 16.7 per

cent, followed by South and Central America’s at 10.4 per cent. Meanwhile, Japan’s import growth

was the slowest of any major economy or region in 2011 at 1.9 per cent. India had the fastest export

growth among major traders in 2011, with shipments rising 16.1 per cent. Meanwhile, China had the

second-fastest export growth of any major economy at 9.3 per cent.

The combination of low export volume growth and high import volume growth seen in the

Commonwealth of Independent States in 2011 can be attributed to the 32 per cent rise in energy

prices for the year, which boosted export earnings and allowed more foreign goods to be imported

(see Table 1.2).

The decline in extra-EU imports (i.e. imports from outside the European Union) measured -3.8 per

cent in the fourth quarter, equivalent to 14.4 per cent at an annualized rate. Such a rate of decline is

unlikely to go on for very long, but it helps to explain the weakness of exports of other

economies at the time. Imports of the United States were flat rather than falling during 2011, but

both the United States and the European Union saw their exports rise over the course of the year.

The other major development was the slump in Chinese imports that occurred around the time of the

Japanese earthquake in the second quarter of 2011.

Between the first and second quarters, China’s imports dropped 6.1 per cent, equivalent to 27 per

cent annually, but in subsequent quarters trade rose 4.2 per cent (18 per cent annualized) and 7.3 per

cent (32 per cent annualized). This is consistent with a strong but relatively short-lived direct impact

from the disaster, although other indirect influences might be just as important. It also demonstrated

the strong insertion of China in Asian value chains.

Although not shown in the charts, the volume of Thailand’s exports plunged 8.5 per cent in the

fourth quarter due to flooding that significantly affected exports of intermediate goods, further

disturbing global production networks.

3. Merchandise and commercial services trade in value (i.e. dollar) terms

The total dollar value of world merchandise exports jumped 19 per cent to US$ 18.2 trillion in 2011

(see Table 1.3).1 This increase was nearly as large as the 22 per cent rise in 2010 and was driven in

large part by higher primary commodity prices.Commercial services exports also grew 11 per cent in

2011 to US$ 4.1 trillion. The share of commercial services in total goods plus commercial services

trade (on a balance of payments basis) was 18.6 per cent, the smallest such share since 1990.

Transport services recorded the slowest growth of any sub-category of services (8 per cent),

followed by other commercial services (11 per cent) and travel (12 per cent).

The slow growth of transport services is perhaps not surprising considering the close relationship

between this category of services and trade in goods, whichstagnated in the second half of 2011. An

oversupply of new container ships may have also depressed revenues in the shipping sector.

Appendix tables 1 to 6 provide detailed information on nominal merchandise and commercial

services trade flows by region and for selected economies. They also include tables of leading

exporters and importers with and without intra-EU trade (i.e. trade between EU members). Some

noteworthy developments for merchandise trade and commercial services are summarized below.

(a) Merchandise trade

The dollar value of North America’s merchandise exports rose 16 per cent in 2011 to US$ 2.28

trillion (equal to 12.8 per cent of the world total), while imports grew 15 per cent to US$ 3.09 trillion

(17.2 per cent) (see Appendix Table 1).

South and Central America’s exports advanced 27 per cent to US$ 749 billion (4.2 per cent of the

world total), buoyed by stronger primary commodity prices. At the same time, the region’s imports

increased by 24 per cent to US$ 727 billion (4.0 per cent). Europe’s nominal exports grew 17 per

cent to US$ 6.60 trillion, or 37.1 per cent of the world total. The region’s imports were also up 17

per cent to US$ 6.85 trillion (38.1 per cent).

Exports of the Commonwealth of Independent States jumped 34 per cent to US$ 788 billion,

supported by rising energy prices. Imports also increased by 30 per cent to US$ 540 billion. Shares

of CIS exports and imports in world trade were 4.4 per cent and 3.0 per cent, respectively.

Africa’s exports were up 17 per cent to US$ 597 billion (3.4 per cent of the world total) while

imports rose 18 per cent to US$ 555 billion (3.1 per cent).

Exports from the Middle East surged 37 per cent in dollar terms to US$ 1.23 trillion (or 6.9 per cent

of the world total) as a result of rising oil prices. In contrast to this, imports only increased by 16 per

cent to US$ 6.65 billion (3.7 per cent).

Finally, Asia’s exports were up 18 per cent in 2011 to US$ 5.53 trillion (31.1 per cent of the world

total) while imports advanced 23 per cent to US$ 5.57 trillion (30.9 per cent).

The top five merchandise exporters in 2011 were China (US$ 1.90 trillion, or 10.4 per cent of world

exports), the United States (US$ 1.48 trillion, 8.1 per cent), Germany (US$ 1.47 trillion, 8.1 per

cent), Japan (US$ 823 billion, 4.5 per cent) and the Netherlands (US$ 660 billion, 3.6 per cent). The

leading importers were the United States (US$ 2.27 trillion, 12.3 per cent of world imports), China

(US$ 1.74 trillion, 9.5 per cent), Germany(US$ 1.25 trillion, 6.8 per cent), Japan (US$ 854 billion,

4.6 per cent) and France (US$ 715 billion, 4 per cent) (see Appendix Table 3).

If we ignore trade between European Union member countries and treat the EU as a single entity, the

top exporters were the European Union (US$ 2.13 trillion, or 14.9 per cent of the world total), China

(13.3 per cent), the United States (10.3 per cent), Japan (5.7 per cent) and the Republic of Korea

(US$ 555 billion, or 3.9 per cent). The leading importers, excluding trade

between EU countries, were the European Union (US$ 2.34 trillion or 16.2 per cent of world

imports), the United States (15.6 per cent), China (12.0 per cent), Japan (5.9 per cent) and the

Republic of Korea (US$ 425 billion, or 3.6 per cent).

There were few significant moves up or down in the world rankings in 2011. The Russian Federation

went from being the 12th largest exporter of merchandise in2010 to being the ninth in 2011

(including EU members).(b) Commercial services trade The region with the fastest growth in

commercial services exports in 2011 was the CIS, with 20 per cent growth in the dollar value of its

exports. Africa had the slowest export growth of any region at zero per cent. All other regions

recorded double-digit growth between 10 and 14 per cent. The slow growth of African exports was

largely due to the turmoil in North African countries. Egypt and Tunisia were especially hard hit as

their commercial services exports fell 20 per cent and 19 per cent, respectively. However, Sub-

Saharan Africa's exports increased in line with the world average

of 11 per cent.

Meanwhile, African services imports rose 9 per cent, slightly less than the world average of 10 per

cent. In contrast to exports, there was not as much of adivergence between Northern Africa and Sub-

Saharan Africa on the import side, as the former grew 7.0 percent and the latter 9.5 per cent. The

region with thefastest growth in services imports was the CIS at21 per cent, followed closely by

South and Central America at 18 per cent. Other regions recorded growthrates for commercial

services imports between 8 and 14 per cent.

The top five exporters of commercial services in 2011 were the United States (US$ 578 billion, or 14

per centof the world total), the United Kingdom (US$ 274 billion,7 per cent), Germany (US$ 253

billion, 6 per cent), China(US$ 182 billion, 4 per cent) and France (US$ 161 billion,

4 per cent). The United Kingdom replaced Germany as the world’s second-largest exporter of

services compared with last year's tables, but this was mainly due to a large upward revision in

official statistics on UK exports ofother business services and financial services, whichtogether

make up roughly half of all UK commercial services exports.

The top five importers of commercial services were the United States (US$ 391 billion, or 10 per

cent of the world total), Germany (US$ 284 billion, 7 per cent), China (US$ 236 billion, 6.1 per

cent), the UnitedKingdom (US$ 171 billion, 4 per cent) and Japan (US$ 165 billion, 4.3 per cent).

There were no changes in the ranking of the top importers.

The above figures include intra-EU commercial services trade, i.e. services trade between European

Union member countries. If this trade is excluded from the world total and the European Union is

treated as asingle entity, the EU becomes the top exporter ofcommercial services (US$ 789 billion,

24.8 per cent ofthe world total), followed by the United States (US$ 578 billion, 18.2 per cent ),

China (US$ 182 billion, 5.7 per cent), India (US$ 148 billion, 4.7 per cent) and Japan (US$ 143

billion, 4.5 per cent). The European Union also becomes the leading importer (US$ 639 billion, 21.1

per cent of the world total), followed by the United States (US$ 391 billion, 12.9 per cent), China

(US$ 236 billion, 7.8 per cent), Japan (US$ 165 billion, 5.4 per

cent) and India (US$ 130 billion, 4.3 per cent).

4. Sectoral developments

Prices for traded manufactured goods have tended to be more stable than those of primary products,

both before and after the economic crisis. As a result, movements in nominal trade flows reflect

changes in quantities reasonably well. With this in mind,Figure 1.4 shows year-on-year growth in

the quarterlyvalue of world trade in several classes of manufactured goods.

All types of manufactured goods saw year-on-year growth fall towards zero over the course of 2011.

For example, world trade in automotive products slid from 44 per cent in the first quarter of 2010 to

10 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2011. Office and telecom equipment went from positive to

negative, as year-onyear growth rates fell from around plus 14 per cent inthe first quarter to minus 2

per cent in the fourth quarter.

5. Exchange rates

The Japanese yen and the Swiss franc both recorded significant nominal appreciations against the

US dollar in 2011. The yen was up 10 per cent year-on-year, partly due to the safe haven role of the

currency during times of uncertainty. Meanwhile, the franc jumped 17 per cent, prompting

interventions by the Swiss National Bank in currency markets to force down the value of the

currency, especially against the euro. The Brazilian real was also up 5.4 per cent against the

dollar, and the Chinese yuan and Korean won rose 4.7 per cent and 4.3 per cent, respectively.

Despite the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, the euro appreciated 5 per cent against the dollar (see

Figure 1.5).

Nominal

exchange rates such as these may over- or under-state the competitive effects of exchange rate

movements. As a result, “real effective” rates that average the exchange value of a currency against

many trading partners while adjusting for differences in inflation rates may provide a better

indication of the competitiveness of a country’s exports.

Real effective exchange rates supplied by the International Monetary Fund show that the US dollar’s

depreciation in 2011 was even stronger in realeffective terms (-4.9 per cent) than in nominal

terms.On the other hand, the average appreciation of othermajor currencies was over-stated. The

Japanese yenonly appreciated 1.7 per cent in real terms while theChinese yuan rose 2.7 per cent.

Brazil’s currencyregistered a strong increase of 4.7 per cent in real effective terms, while the euro’s

rise of 1.8 per cent was relatively small.

SLOW GLOBAL GROWTH TO HIT TRADE IN 2012 AND 2013: WTO

Slowing global output growth has led WTO economists to downgrade their 2012 forecast for world

trade expansion to 2.5% from 3.7% and to scale back their 2013 estimate to 4.5% from 5.6%. “In an

increasingly interdependent world, economic shocks in one region can quickly spread to others.

Recently announced measures to reinforce the euro and boost growth in the United States

The global economy has encountered increasingly strong headwinds since the last WTO Secretariat

forecast was issued in April. Output and employment data in the United States have continued to

disappoint, while purchasing managers’ indices and industrial production figures in China point to

slower growth in the world’s largest exporter. More importantly, the European sovereign debt crisis

has not abated, making fiscal adjustment in the peripheral euro area economies more painful and

stoking volatility. Figures for world trade include trade between EU countries (i.e. EU intra-trade),

making them highly sensitive to developments in this region.

All of these factors have contributed to an easing of global trade growth, which slowed to a crawl in

the second quarter according to new quarterly merchandise trade volume statistics compiled by the

WTO (Chart 1 and box).

Chart 1 — World merchandise trade volume, 2005Q1-2013Q4 Seasonally adjusted index, 2005Q1=100

Source: WTO Secretariat.

The volume of world trade as measured by the average of exports and imports only managed to grow

0.3% in the second quarter compared to the first, or 1.2% at an annualized rate. The trade slowdown

in the first half of 2012 was driven by an even stronger deceleration in imports of developed

countries and by a corresponding weakness in the exports of developing economies, which for the

purposes of this analysis includes the Commonwealth of Independent States (Table 1).

The WTO now expects world merchandise trade volume to grow by 2.5% in 2012 (down from 3.7%

in April). On the export side, we anticipate a 1.5% increase in developed economies’ trade (down

from 2%) and a 3.5% expansion for developing countries (down from 5.6%). On the import side, we

foresee nearly stagnant growth of 0.4% in developed economies (down sharply from 1.9%) and a

more robust 5.4% increase in developing countries (down from 6.2%).

Table 1 — World merchandise trade and GDP, 2008-2013 a Annual % change

a Figures for 2012 and 2013 are projections.

b Average of exports and imports.

Source: WTO Secretariat for trade, concensus estimates of economic forecasters for GDP.

Figures for 2013 are provisional estimates based on strong assumptions about medium-term

economic developments, including:

1. that current policy measures will be sufficient to avert a breakup of the euro, and

2. an agreement will be reached to stabilize public finances in the United States, thereby

avoiding automatic spending cuts and tax increases early next year.

Failure of these and other assumptions could derail the latest projections.

As a result, these figures should be interpreted with caution. Based on current information, the WTO

expects trade growth to rebound to 4.5% in 2013. Exports of developed and developing economies

should increase by 3.3% and 5.7%, respectively, while imports of developed and developing

countries should advance 3.4% and 6.1%.

Chart 2 — Merchandise trade of major developed

economies, 2010Q1-2012Q2

Seasonally adjusted volume indices, 2010Q1=100

Although developed countries collectively recorded modest increases in both exports and

importsin2012, some grew faster than others. Chart 2 shows seasonally adjusted quarterly trade

volume indices for the largest developed economies since the beginning of 2010.

Exports of the United States and shipments from the EU to the rest of the world (i.e. extra-EU

exports) grew steadily over the past year, with year-on-year increases of around 7% and 5%,

respectively, in the second quarter. Japanese exports have been mostly flat since mid-2010, but even

they recorded an 8.5% year-on-year increase in the second quarter. Imports of the United States and

Japan have also held up relatively well despite the crisis, with year-on-year growth of roughly 5%

and 6% in the latest period. However, import demand in the European Union has weakened

significantly, resulting in less tradebetween EU countries (intra-trade down3.5% year-on-year in the

second quarter) and fewer imports from the rest of the world (also down 3.5%). The weight of the

EU in total world trade (around 35% on both the export and import sides in 2011, including EU-intra

trade), combined with the larger-than-expected year-on-year drop in EU imports through the first

half of 2012, explains much of the downward revision to the forecast. The EU also represents nearly

60% of developed economies’ imports, which accounts for the stagnation in projected imports of

developed economies in 2012.

Weak import demand in developed countries and softer domestic demand in China have contributed

to sagging trade flows in the developing world, most noticeably in dynamic export-oriented

economies in Asia. Chart 3 shows year-on-year growth in China’s merchandise trade flows in

volume terms (not seasonally adjusted), which have declined steadily over the last two and a half

years. Export growth dropped to 2.9% and import growth fell to 2.8% in the first quarter of 2012

before rebounding slightly in the second quarter, but available monthly data suggest that the third

quarter results may be weaker still.

Chart 3 — Merchandise exports and imports of China, 2010Q1-2012Q2

(year-over-year % change in volume, not seasonally adjusted)

Source: WTO Secretariat.

Chart 4 shows year-on-year growth in monthly merchandise exports and imports for selected

economies in current dollar terms, including partial data for the third quarter. Those economies that

have already reported figures for August show either stagnation (e.g. China) or decline (e.g. Brazil,

Japan, Singapore), which suggests that that the recent weakness of trade will persist into the third

quarter. Risks to the forecast will remain mostly on the downside as long as financial uncertainty in

Europe remains elevated. Other events could also intrude to produce worse outcomes for trade,

including a “hard landing” for the Chinese economy or geopolitical tensions. However, there is also

some upside potential if the European Central Bank’s recently announced bond purchasing program

has an immediate salutary effect on EU import demand. In this case we might see slightly faster

growth in the fourth quarter and for 2012 as a whole, but possibly less growth in 2013 as the

reversion to recent trends would be weaker. The growth of world trade observed in the first half of

2012 is less than what traditional econometric models would predict given current rates of growth in

gross domestic product (GDP). This also occurred during the trade collapse of 2008–09 that

accompanied the global financial crisis and may be related to issues such as access to trade finance

or, in the case of the sovereign debt crisis, the re-introduction of exchange rate risk into peripheral

euro area economies.

Chart 4 — Merchandise exports and imports of selected economeis, January 2011-August 2012

(Year-on-year % change in current dollar values)

Sources: IMF International Financial Statistics, Global Trade Information Services GTA database, national statistics.

http://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres12_e/pr676_e.htm

EMERGING TRENDS IN GLOBAL TRADE

Today, five countries produce 70 percent of the world’s rice, three countries produce 80 percent of

our soybeans, five countries produce 70 percent of our maize. And this concentration of production

is mirrored, if not accentuated, in international trade. For example, 85 percent of all

soybeans in the international market are exported by two countries.

Trade Reflects Economic Activity

World trade generally rises and falls with the overall level of global economic activity. Global

trading activities have been sluggish over the past few quarters. In the second quarter of 2011, world

merchandise trade contracted by 0.5 percent quarter-on-quarter and recorded subdued growth of 1

percent in the third quarter. The recent weakness resembles 2008-09, when world trade contracted

due to a steep fall in global output.

A number of factors such as composition and inventory effects, financial constraints, and vertical

linkages were found to have amplified the collapse in trade in 2008 and 2009. The following graph

mirrors co-movement of world industrial production and world trade.

South-South Trade

Until about two decades ago, South-South trade (trade between developing countries) in goods had a

minor share of world trade. Records based on UNCTAD data spanning 1955 to 1985 reveal no

discernable trend. By 1985, South-South trade as a share of total world trade had increased only

marginally to 7.8 percent from 7.1 percent and represented less than a third of developing countries’

total merchandise exports. South-South trade increased at a rate of 13.7 percent per year between

1995 and 2010—well above the world average of 8.7 percent. Over the same period, the South’s

merchandise exports to the North increased by 9.5 percent per annum. South-South trade in goods

has expanded considerably during the last two decades. Its share of merchandise trade rose from

about 7 percent in 1990 to 17 percent in 2009.

Dominance of BRICS

While the recent import demand in most developing countries has remained vigorous, only a few of

these countries have succeeded in climbing up the global value chain. In fact, about 83 percent of the

increase in the share of developing countries’ total world trade between 1995 and 2010 was accrued

to the emerging economies, mainly BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) plus

Mexico and the Republic of Korea. China, India and Korea accounted for about one-third of world

exports and two-thirds of developing country exports in 2010. Some of these gains result from

growing cross-border specialization involving smaller segments of value chains, which in turn

increase trade shares and the value of shipments, imports and exports.

Shifting Patterns in International Trade

According to a UN report released in February 2012, the share of developed countries in world

merchandise trade in value terms declined from 69 percent to 55 percent between 1995 and 2010,

while that of developing countries increased from 29 percent to 41 percent. Over this 15-year period,

China’s share alone increased fourfold from 2.6 percent to about 10 percent. Over the same period,

the share of Latin America and the Caribbean increased from 4.5 percent to 5.9 percent. The value of

Africa’s merchandise exports rose from $100 billion in 1995 to $560 billion in 2010, while its share

in world trade improved modestly from 2 percent to 3.2 percent. The marked weakness of import

demand from developed countries comes on top of a decade-long decline of their predominance in

international trade.

The shifting patterns of trade are associated with the rapid industrial growth of developing countries.

Moving from agricultural and other primary production to manufacturing tends to drive up the

import intensity of production. Moreover, global trade increasingly involves value chains with

different geographical locations contributing various parts to the production processes. Such shifting

patterns of trade as well as increased demand for primary commodities from the rapidly-growing

economies have strengthened South-South trade.

TRENDS IN INDIA'S FOREIGN TRADE

India’s Trade Performance

India’s merchandise exports reached a level of US $ 251.14 billion during 2010-11 registering a

growth of 40.49 percent as compared to a negative growth of 3.53 percent during the previous year.

India’s export sector has exhibited remarkable resilience and dynamism in the recent years. Despite

the recent setback faced by India’s export sector due to global slowdown, merchandise exports

recorded a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 20.0 per cent from 2004-05 to 2010-11.

World Trade Scenario

As per IMF’s World Economic Outlook October, 2011, world trade recorded its largest ever annual

increase in 2010, as merchandise exports surged 14.4 per cent. The volume of world trade (goods

and services) in 2011 is expected to slow down to 7.5 per cent compared to the 12.8 per cent

achieved in 2010. Growth in the volume of world trade is expected to decline in 2012 to 5.8 per cent

as per IMF projections.

The IMF has moderated its growth projections of world output to 4 per cent in 2012. The advanced

economies are expected to grow at 1.9 per cent in 2012 while the emerging and developing

economies to grow at 6.1 per cent. The projected growth rates in different countries are expected to

determine the markets for our exports.

As per WTO’s International Trade Statistics, 2010, in merchandise trade, India is the 20th largest

exporter in the world with a share of 1.4 per cent and the 13th largest importer with a share of 2.1

per cent in 2010.

The year 2011 has been a difficult year with Japan facing a major earthquake and tsunami, the

swelling of unrest in the Middle East oil producing countries, the slowing down of US economy and

the Euro area facing major financial turbulence. The current global economic slowdown has its

epicenter in the Euro-region but the contagion is being witnessed in all major economies of the

world. As a result, India’s short-term growth prospects have also been impacted.

Exports

Exports recorded a growth of 40.49 per cent during April-March 2010-11. The Government has set

an export target of US $ 300 billion for 2011-12. With merchandise exports reaching US $ 217.66

billion in 2011-12(Apr-Dec), the export target of 300 US $ billion is expected to be achieved. Export

target and achievement from 2004-05 to 2010-11 and 2011-12 (Apr-Dec) is given in the Chart 2.1

below:

Imports

Cumulative value of imports during 2011-12 (Apr-Dec) was US $ 350.94 billion as against US $

269.18 billion during the corresponding period of the previous year registering a growth of 30.4 per

cent in $ terms. Oil imports were valued at US $ 105.6 billion during 2011-12 (Apr-Dec) which was

40.39 per cent higher than oil imports valued US $ 75.2 billion in the corresponding period of

previous year. Non-oil imports were valued at US $ 245.35

Chart 2.1

Export Target & Achievement

billion during 2011-12 (Apr-Dec) which was 26.49 per cent higher than non-oil imports of US $

194.0 billion in previous year.

Trade Balance

The Trade deficit in 2011-12 (Apr-Dec) was estimated at US $ 133.27 billion which was higher than

the deficit of US $ 96.21 billion during 2010-11 (Apr-Dec). Performance of Exports, Imports and

Balance of Trade during 2004-05 to 2011-12 (April-Dec) is given in the table below:

(Values in Crores)

S.N

o

Year Exports %Growth Imports %Growt

h

Trade

Balance

1 2004-2005 3,75,340 27.94 5,01,065 39.53 -1,25,725

2 2005-2006 4,56,418 21.6 6,60,409 31.8 -2,03,991

3 2006-2007 5,71,779 25.28 8,40,506 27.27 -2,68,727

4 2007-2008 6,55,864 14.71 10,12,312 20.44 -3,56,448

5 2008-2009 8,40,755 28.19 13,74,436 35.77 -5,33,680

6 2009-2010 8,45,534 0.57 13,63,736 -0.78 -5,18,202

7 2010-2011

(Provisional)

11,42,649 35.14 16,83,467 23.45 -5,40,818

8 2010-11 (Apr-

Dec)

7,89,069 12,28,074 -4,39,006

9 2011-12 (Apr-

Dec)

10,24,707 29.86 16,51,240 34.46 -6,26,533

Data Source: DGCIS, Kolkata

S.N

o

Year Exports %Growt

h

Imports %Growth Trade

Balance

1 2004-2005 83,536 30.85 1,11,517 42.7 -27,981

2 2005-2006 1,03,091 23.41 1,49,166 33.76 -46,075

3 2006-2007 1,26,414 22.62 1,85,735 24.52 -59,321

4 2007-2008 1,63,132 29.05 2,51,654 35.49 -88,522

5 2008-2009 1,85,295 13.59 3,03,696 20.68 -1,18,401

6 2009-2010 1,78,751 -3.53 2,88,373 -5.05 -1,09,621

7 2010-2011

(Provisional)

2,51,136 40.49 3,69,769 28.23 -1,18,633

8 2010-11 (Apr-Dec) 1,72,965 2,69,175 -96,210

9 2011-12 (Apr-Dec) 2,17,664 25.84 3,50,936 30.4 -1,33,272

Chart 2.2

Month-wise Growth during 2011-12 (April-Dec) over 2010-11 (April-

Dec)

Strategy for Doubling Exports

Global economic outlook is a major determinant of export performance of any country. Export

growth cannot, therefore, be viewed in isolation from economic outlook in the world economy.

Keeping in view the urgency of managing the growing trade deficit and uncertain global economic

scenario, Department of Commerce, in May 2011 finalized a Strategy Paper for doubling

merchandise exports in three years from US $ 246.00 billion in 2010-11 to US $ 500 billion in 2013-

14. Exports were envisaged to increase at compounded average growth of 26.7% per annum.

Exports by Principal Commodities

Disaggregated data on exports by Principal Commodities, both in Rupee and Dollar terms, available

for the period 2011-12 (April-October) as compared with the corresponding period of the previous

year are given in Table 2.1, and 2.2 respectively. Exports of the top five commodities during the

period 2011-12 (April-October) registered a share of 53.1 per cent mainly due to significant

contribution in the exports of Petroleum (Crude & Products), Gems & Jewellery, Transport

Equipments, Machinery and Instruments, Drugs, Pharmaceuticals & Fine Chemicals.

The share of top five Principal Commodity Groups in India’s total exports during 2011-12 (April-

October) is given at Chart 2.3 below:

Chart 2.3

Share of Top Principal Commodities in India’s Export 2011-12 (April-October)

The export performance (in terms of growth) of top five commodities during 2011-12 (April-

October) vis-a-vis the corresponding period of the previous year is shown at Chart 2.4.

Chart 2.4

Top five commodities of Export by Growth 2010-11 & 2011-12

Plantation Crops

Export of Plantation crops during 2011-12(April–October), increased by 39.29 per cent in US $

terms compared with the corresponding period of the previous year. Export of Coffee registered a

growth of 77.50 per cent, the value increasing from US $ 313.53 million to US $ 556.52 million.

Export of Tea also increased by 9.34 per cent.

Agriculture and Allied Products

Agriculture and Allied Products as a group include Cereals, Pulses, Tobacco, Spices, Nuts and

Seeds, Oil Meals, Guar gum Meals, Castor Oil, Shellac, Sugar & Molasses, Processed Food, Meat &

Meat Products, etc. During 2011-12 (April–October), exports of commodities under this group

registered a growth of 62.90 per cent with the value of exports increasing from US $ 8165.03 million

in the previous year to US $ 13300.63 million during the current year.

Ores and Minerals

Exports of Ores and Minerals were estimated at US $ 4700.29 million during 2011-12 (April-

October) registering a negative growth of 8.32 per cent over the same period of the previous year.

Sub groups viz. Processed Minerals and Iron Ore has recorded a negative growth of 17.22 per cent

and 23.29 per cent. Coal registered a growth of 35.76 per cent and Other ores & minerals 78.37 per

cent respectively. Mica has registered a growth of 5.74 per cent

Leather and Leather Manufactures

Export of Leather and Leather Manufactures recorded a growth of 27.64 per cent during 2011-12

(April-October). The value of exports increased to US $ 2704.51 million from US $ 2118.86 million

during the same period of the previous year. Exports of Leather and Manufactures have registered a

growth of 30.19 per cent and Leather Footwear also registered a growth of 24.55 per cent.

Gems and Jewellery

The export of Gems and Jewellery during 2011-12(April-October) increased to US $ 27664.09

million from US $ 16770.33 million during the corresponding period of last year showing a growth

of 64.96 per cent.

Chemicals and Related Products

During the period 2011-12 (April-October), the value of exports of Chemicals and Allied Products

increased to US $ 21977.24 million from US $ 16276.94 million during the same period of the

previous year registering a growth of 35.02 per cent. Rubber, Glass & Other Products, Residual

Chemicals & Allied Products, Basic Chemicals, Pharmaceuticals & Cosmetics and Plastic &

Linoleum have also registered a positive growth.

Engineering Goods

Items under this group consist of Machinery, Iron & Steel and Other Engineering items. Export from

this sector during the period 2011-12(April-October) stood at US $ 36694.23 million compared with

US $ 27098.96 million during the same period of the previous year, registering a growth of 35.41 per

cent. The growth in export of Iron & Steel Bar rod stood at 51.86 per cent, Transport Equipments

39.38 per cent, Primary & semi-finished iron & steel 23.20 per cent, Non ferrous metals 13.59 per

cent, and Machine Tools at 10.99 per cent.

Electronic Goods

During the period 2011-12 (April-October), exports of Electronic Goods as a group was estimated at

US $ 5024.92 million compared with US $ 4299.36 million during the corresponding period of last

year, registering a growth of 16.88 per cent.

Textiles

During the period 2011-12 (April-October), the value of Textiles exports was estimated at US $

15101.96 million compared with US $ 11987.38 million in the corresponding period of the previous

year, recording a growth of 25.98 per cent. The export of Readymade Garments registered a growth

of 28.60 per cent, Cotton yarn/Fabrics/Made-ups etc. registered a growth of 23.06 per cent, Wool

and Woolen manufactures 54.21 per cent, Coir and coir manufactures 38.85 per cent, Manmade

Textiles & Made Ups has shown a growth of 30.25 per cent, Natural Silk Textiles and Jute

manufactures registered a negative growth of 35.15 per cent and 4.67 per cent respectively.

Handicrafts and Carpets

Exports of Handicrafts declined to US $ 101.67 million during 2011-12 (April- October), from US $

128.24 million during the corresponding period of the previous year registering a negative growth of

20.72 per cent. Export of carpets decreased to US $ 439.66 million from US $ 536.98 million during

the same period last year registering a negative growth of 18.12 per cent.

Project Goods

During 2011-12 (April-October), the export of Project Goods were estimated at US $ 29.05 million

compared with US $ 38.18 million during the corresponding period of last year registering a

negative growth of 23.91 per cent.

Petroleum Products

Export of Petroleum Products increased to US $ 34667.02 million during 2011-12 (April- October),

as compared with US $ 21135.13 million during the same period of last year recording a growth of

64.03 per cent.

Cotton Raw including Waste

There was a growth in the exports of Cotton Raw including waste by 178.63 per cent from US $

389.52 million in 2010-11 (April-October) to US $ 1085.30 million during 2011-12 (April-

October).

Imports by Principal Commodities

Disaggregated data on imports by principal commodities, both in Rupee and Dollar terms, available

for the period 2011-12 (April– October), as compared to the corresponding period of the previous

year are given in Table 2.5 and Table 2.6 respectively. Imports of the top five commodities during

the period 2011-12 (April-October) registered a share of 62.8 per cent mainly due to significant

imports of Petroleum (Crude & Products), Gold, Electronic Goods, Pearls, precious and semi-

precious stones and Machinery except electrical and electronic.

The share of top five Principal Commodity in India’s total imports during 2011-12 (April– October)

is given at Chart 2.5 below:

Chart 2.5

Share of Top Five Principal Commodities in India’s Imports 2011-12 (April-

October)

The import performance by growth of top five Principal commodities during 2011-12 (April–

October) vis-a-vis the corresponding period of the previous year is shown at Chart 2.6.

Chart 2.6

Top Five Commodities of Import by Growth 2009-10 & 2010-11

Fertilizers

During 2011-12 (April–October), import of Fertilizers (manufactured) decreased to US $ 4413.85

million from US $ 4695.51 million in April-October 2011 recording a negative growth of 6.00 per

cent.

Petroleum Crude & Products

The import of Petroleum Crude & Products stood at US $ 85002.32 million during 2011-12 (April -

October) as against US $ 58175.62 million during the same period of the previous year registering a

growth of 46.11 per cent.

Pearls, Precious and Semi-Precious Stones

Import of Pearls and Precious and Semi-Precious Stones during 2011-12 (April– October) increased

to US $ 17187.45 million from US $ 16907.33 million during the corresponding period of the

previous year registering a marginal growth of 1.66 per cent.

Capital Goods

Import of Capital Goods, largely comprises of Machinery, including Transport Equipment and

Electrical Machinery. Import of Machine Tools, Non-Electrical Machinery, Electrical Machinery

and Transport Equipment registered a growth of 43.24 per cent, 26.87 per cent, 26.39 per cent, and

(-) 8.74 per cent respectively.

Organic and Inorganic Chemicals

During 2011-12 (April– October), import of Organic and Inorganic Chemicals increased to US $

10884.61 million from US $ 8847.19 million during the same period of last year, registering a

growth of 23.03 per cent. Import of Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Products increased to US $

1615.63 million from US $ 1425.68 million during the corresponding period of last year registering

a growth of 13.32 per cent

Coal, Coke & Briquettes

During 2011-12 (April– October), import of Coal, Coke & Briquettes increased to US $ 9870.14

million from US $ 6570.07 million during the same period of last year, registering a growth of 50.23

per cent.

Gold & Silver

During 2011-12 (April– October) import of Gold and Silver increased to US $ 38817.81 million

from US $ 23320.39 million during the corresponding period of the previous year registering a

growth of 66.45 per cent.

Direction of India’s Foreign Trade

The value of India’s exports and imports from major regions/ countries both in Rupee and Dollar

terms are given in Table 2.3, 2.4, 2.7 and 2.8 respectively. Share of major destinations of India’s

Exports and sources of Imports during 2011-12 (April– October) are given in Chart 2.7 and 2.8

respectively.

Chart 2.7

Major Destinations of India’s Exports for 2011-12 (April-October)

During the period 2011-12 (April– October), the share of Asia and ASEAN region comprising South

Asia, East Asia, Mid-Eastern and Gulf countries accounted for 50.69 per cent of India’s total

exports. The share of Europe and America in India’s exports stood at 19.73 per cent and 16.68 per

cent respectively of which EU countries (27) comprises 17.81 per cent. During the period, United

Arab Emirates (11.82 per cent) has been the most important country of export destination followed

by USA (11.51 per cent), Singapore (6.13 percent), China (5.35) per cent), Hong Kong (4.44 per

cent).

Asia and ASEAN accounted for 61.36 per cent of India’s total imports during the period followed by

Europe (19.27 per cent) and America (8.92 per cent). Among individual countries the share of China

stood highest at (12.00 per cent) followed by UAE (7.51 per cent), Switzerland (7.21 per cent),

Saudi Arabia (6.06 per cent), USA (4.78 per cent) Iraq (3.85 per cent), Germany (3.25 per cent),

Nigeria (3.25 per cent), Indonesia (3.06 per cent), Australia (2.96 per cent).

Chart 2.8Major Source of India’s Imports for 2011-12 (April-October)

http://commerce.nic.in/publications/anualreport_chapter2-2011-12.asp

ROLE OF INDIA IN WORLD TRADE

According to the International Monetary Fund’s International Financial Statistics (July 2012), the

value of world merchandise export grew by 14.8 per cent during 2011-12, lower than 21.2 per cent

during 2010-11 (Chart 2). Subdued growth conditions in advanced economies began to weaken

external demand for Emerging and Developing Economies (EDEs) in the latter half of 2011-12.

Consequently, India’s export growth also showed concomitant moderation which was nearly half of

that recorded in 2010-11. Going forward, the risks of weaker growth in advanced countries remain

elevated with knock-on effects to developing countries like India. Even though there was some

recovery in trade at global level during Q1 of 2012 (January-March), a resurgence in fi nancial

market stress in the Euro Area since April 2012 along with decline in business and consumer confi

dence may keep the import demand from euro zone countries weak in coming period. In the latest

WEO update of July 2012,the IMF has retained its earlier projections of export volume growth for

advanced economies at 2.3 per cent during 2012, whereas the same has been revised downwardly

from 6.6 per cent to 5.7 per cent in case of EDEs.

Cross-country comparison of export performance indicates that India’s export growth was largest

among the major advanced and EDEs during 2010-11 and 2011-12 enabling a corresponding

increase in India’s share in world export (Table 7). Going forward, downward risks to India’s

exports continue to be on account of slower global recovery, fi nancial contagion related to the

eurozone sovereign debt crisis and geopolitical risks.

World Commodity Prices

During 2011-12, world commodity prices remained subdued as the average growth in all

commodities prices decelerated to 19.8 per cent during 2011-12 from 24.0 per cent 2010-11. Among

major commodities,growth in metals prices fell sharply from 40.2 per cent in 2010-11 to 3.0 per cent

in 2011-12 mainly on account of continued concerns about weakening global demand and the

uncertainty about near-term global economic prospects (Chart 3). Furthermore, in the fi rst quarter of

2012-13, growth (year on year) in all major commodities prices such as food, metal and energy

turned negative as concerns relating to weaker global demand prospects, particularly in Europe and

China, intensifi ed. Apart from growth concerns, high and rising stocks led to decline in prices of

most of metals. Crude-oil prices declined in Q1 of 2012-13, particularly in the month of June not

only on account of global growth concerns but also due to apparent easing of oil supply concerns

related to Iran and increase in oil production above the quota by OPEC countries. Similarly, coal

prices fell in Q1 of 2012-13 due to anticipated weak global consumption and rising supply.

Growth rates and shares of Exports: Cross-Country Comparison

In the wake of the global crisis and the problems being faced by exporters, the Reserve Bank of

India (RBI) had reduced the interest rate ceiling to 250 bps below the benchmark prime lending rate

(BPLR) on pre-shipment rupee export credit up to 270 days and post-shipment rupee export credit

up to 180 days. This facility was available up to 30 June, 2010. In addition, the Government of India

in its Union Budget for 2010-11 extended interest rate subvention of 2 per cent on pre and post

shipment rupee export credit for certain employment-oriented export sectors such as handicrafts,

carpets, handlooms, and small and medium enterprises up to 31 March 2011. On 9 August 2010, the

interest rate subvention scheme was further extended to leather and leather manufacturers, jute

manufacturing including floor covering, engineering goods, and textiles for the period from 1 April

2010 to March 31, 2011. With the introduction of a base rate, the lending rates charged on rupee

export credit were deregulated with effect from 1 July 2010. However, the RBI has stipulated that

banks may reduce the interest rate chargeable as per the base rate in the sectors specified above by

the subvention available, even if the interest rate charged to exporters goes below the base rate,

subject to a ceiling of 7 per cent.

EXAMPLES

Indian Engineering Sector : Need for More Focus

The engineering industry is the largest segment of the Indian industrial sector. It accounts for 3 per

cent of India’s GDP with a 30.5 per cent weight in the index of industrial production (IIP); 29.9 per

cent share of total investment; and 62.8 per cent share in foreign collaborations. Engineering exports

are one of the largest foreign exchange earners for the country and account for over 20 per cent of

India’s total exports with around 35 per cent of the engineering exports contributed by the micro,

small, and medium enterprises (MSME) sector. India’s export of engineering goods grew at 25.2 per

cent (CAGR) during 2000-01 to 2007-08. In 2008-09, the growth moderated to 18.7 per cent and in

2009-10 it declined by 19.6 per cent because of global recession, with its share in total exports

falling to 18.2 per cent. In the first half of 2010-11, there was a robust growth of 46.0 per cent

partially due to base effect and partially due to global recovery following stimulus measures. The

performance of principal categories of engineering items export shows that in 2009-10, all the major

categories of engineering goods had negative growth. In the first half of 2010-11, all the major

categories like machinery, iron and steel, and other engineering goods registered high growth with

the major sub-categories like transport equipment, primary and semi-finished iron and steel, non-

ferrous metals and manufactures of metals registering whopping growths of 61.8 per cent, 65.0 per

cent, 61.5 per cent, and 40.3 per cent respectively. Only one major sub-category, i.e. machinery and

instruments registered moderate growth of 10.5 per cent (see Table 1)

Table 1 : Export Performance of Different Engineering Goods

The major markets for Indian engineering exports are the USA, Singapore, UAE, UK, China,

Germany, and Italy. Notably, while there was a fall in growth of India’s engineering exports to most

of the markets in 2009-10, its engineering exports to China grew by over 62 per cent. With a 0.8 per

cent share of world engineering exports in 2008, India ranks 30th—below all comparable countries

— in the global engineering exports market. This low position is primarily attributable to three

factors: 1) Low exportsto- GDP ratio: exports-to-GDP ratio of 15 per cent for India vis-à-vis 27 per

cent for comparable countries 2) Low engineering-to-total exports ratio: engineering exports to total

exports ratio of 24 per cent for India vis-à-vis 30 per cent for comparable countries 3) Low

technology-intensity of engineering exports: share of high and medium technology products in

engineering exports is 62 per cent for India vis-à-vis 71 per cent for comparable countries. Given

India’s current low share of world engineering exports and the significant scope for improvement in

competitiveness, there is potential for achieving higher growth in this major sector of world trade.

Performance of SEZs in India

SEZs are becoming increasingly important in India’s exports. The performance of SEZs is mainly

examined in three areas, exports, employment, and investment.

Exports: A total of 130 SEZs are already exporting. Out of this 75 are information technology (IT)/

IT enabled services (ITES), 16 multi-product and 39 other sector specific SEZs. The total number of

units in these SEZs is 3139. The physical exports from the SEZs have increased by 121 per cent to `

2,20,711 crore in 2009- 10 with a CAGR of 58.6 per cent during 2003-04 to 2009-10 compared to

the CAGR of 19.3 per cent for total merchandise exports of the country for the same period. When

the whole world including India was reeling under the effects of the global recession, growth in

exports from SEZs was 121 per cent in 2009-10 compared to a paltry 0.6 per cent growth in total

exports from India. Exports during the first three quarters of the current year have been to the tune of

` 2,23,132 crore. The share of SEZs in India’s total exports has increased consistently from 4.7 per

cent in 2003-04 to 26.1 per cent in 2009-10 and 29.7 per cent in the first three quarters of 2010-11

(see Table 1).

SEZs Exports and India’s Total Exports: A Comparison Year

One of the criticisms SEZs face is that exports are mainly from the old SEZs which were formerly

free trade zones (FTZs) and not from greenfield SEZs. It is interesting to know that not only have

many greenfield SEZs started exporting but also the exports of new SEZs, i.e. SEZs notified under

the SEZ Act 2005, have grown rapidly over the years resulting in the highest share of 53.4 per cent

for this category in 2009-10 compared to Central Government SEZs and State Government /private

SEZs established prior to the SEZ Act 2005 (see Table 2).

Exports from New and Old SEZs

Employment: Out of the total employment of 6,44,073 persons in SEZs, an incremental

employment of 5,09,369 persons was generated after February 2006 when the SEZ Act came into

force. At least double this number obtains indirect employment outside the SEZs as a result of the

operations of SEZ units. This is in addition to the employment created by the developer for

infrastructure activities.

Investment: The total investment in SEZs till 31 December 2010 is approximately ` 1,95,348 crore

including ` 1,91,313 crore in the newly notified zones. In SEZs 100 per cent FDI is allowed through

automatic route.The Government’s role has been more as a facilitator by fast tracking the approvals

rather than providing any direct monetary support. SEZs being set up under the SEZ Act 2005 are

primarily private investment driven.

Issues: Some important issues relating to SEZs are the following:

Direct Tax Code (DTC) Impact: The issue is related to deadlines for profit-linked deductions: As per

the DTC, SEZ developers will be allowed profit-linked deductions for all SEZs notified on or before

31 March 2012. Units in SEZs that will commence commercial operations by 31 March 2014 too

will be allowed profit-linked exemptions. Developers and units notified after these dates will only

have investment-linked exemptions and not profit-linked exemptions. There is concern about these

dates among developers and units particularly in the big SEZs with long gestation time. Goods and

Services Tax (GST): As per the GST model being considered, GST will be levied on imports with

necessary constitutional amendments. Though full and complete set off would be available on the

GST paid on import of goods and services, after the introduction of the GST, tax exemptions,

remissions, etc. related to industrial incentives should be converted, if at all needed, into cash refund

schemes after collection of tax, so that the GST scheme on the basis of a continuous chain of set-offs

is not disturbed.

Regarding special Industrial Area Schemes, such exemptions, remissions would continue up to

legitimate expiry time both for the Centre and the States. However, any new exemption, remission,

or continuation of an earlier one would not be allowed. In such cases, the Central and State

Government could provide reimbursement after collecting the GST. Issue of Power generation and

distribution: Another area of concerns is the generation and distribution of power by the SEZ

developers/units. While one opinion is that it should be left to the entrepreneur to decide whether he

would like to provide power as an infrastructure, as defined in the SEZ Act, or set up a unit to sell

power as a good, another view is that power cannot be an infrastructure and can be only a good to be

generated and distributed by the unit. It may be worth considering appropriate policy to encourage

power generation and distribution.

Coordination issues: The Directors, STPI, have been declared Development Commissioners (DCs)

for the IT SEZs under their respective jurisdiction. An STPI is under administrative control of the

Department of Information Technology. Other multi-product and sector-specific SEZs are under the

charge of DCs appointed by the Department of Commerce. However a number of issues, for

example processing of notification of IT SEZs, coordination with state governments etc, relating to

IT SEZs are also looked after by the DCs appointed by the Department of Commerce. This leads to a

situation of dual control adversely impacting effective coordination and needs to be resolved.

Disinvestment: The new SEZs have come up mainly in the private sector with no funding from the

Government. Now the time has possibly come to see whether some of the established SEZs which

are state owned could also be privatized. Disinvestment in these SEZs could not only add to the kitty

of the Government and release more money for social-sector development but could also make these

SEZs more efficient.

CONCLUSION

WORLD trade slowed last year, as major countries like Japan and Germany shipped exports that

were worth less than those in 2011. The United States bucked the trend to some extent, but the 4.5

percent increase in exports was far smaller than the 15.8 percent jump in 2011.

The accompanying charts show the change in exports and imports of goods in 12 large countries —

the industrialized countries in the Group of 7, in addition to Australia and four emerging economies,

China, Brazil, India and South Korea. All figures are in United States dollars.

Of the 12, only China, with an 8 percent gain, posted faster growth in exports than the United States.

Canada reported a small gain, but the others showed declines. In their local currencies, South Korea

and India had gains, but they were erased by the decline of those currencies against the dollar.

Import totals can provide an indication of economic woes, as declining incomes cause consumers to

buy less, including fewer items from abroad. Imports fell in Germany, France and particularly Italy.

This week, the European Union reported that the euro zone economy declined in the fourth quarter

— the third consecutive fall. Germany’s economy, which had been growing slowly, also shrank.

In the United States, imports of goods rose just 3 percent in 2012. It was the second consecutive

year, and the sixth year in the last seven, that exports grew more — or, in 2009, shrank less — than

imports. Before that, imports rose faster than exports for eight consecutive years, from 1998 through

2005.

The United States runs a trade surplus in services, not shown in the chart, but the trade deficit in

goods widened slightly in 2012 to $727.9 billion. That figure is still well below the deficits from

2004 through 2008, before the credit crisis and recession caused international trade to decline rapidly

in 2009. The strong gains many countries experienced in 2010 and 2011 reflected a return to more

normal levels.

Exports plunged in all countries during the crisis, but the trends since then have varied. German

exports in 2012 were 3 percent lower than in 2008, while French exports were off almost 8 percent.

Japanese and British exports were about 2 percent higher. The United States, by contrast, reported

exports of goods in 2012 that were up 20 percent from 2008, and Brazilian exports were 23 percent

higher.

Those gains pale next to those of developing Asian economies. South Korean exports in 2012 were

30 percent higher than in 2008, while China bolstered its shipments by 43 percent. Indian exports

were 50 percent higher.

The charts also show changes in American trade with the other 11 countries listed. Exports to most

of the European countries fell in 2012, but exports to France rose sharply. France has resisted

austerity more than most of its neighbors, something that may have contributed to the rise.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/16/business/economy/in-world-trade-data-signs-of-a-

slowdown.html?_r=0