WM-doubles

-

Upload

david-kells -

Category

Documents

-

view

39 -

download

2

Transcript of WM-doubles

_ 05.March. 2014

MANAGING WASTE

PAGE 08BRING BACKBOTTLEDEPOSITS

PAGE 10AIMINGAT ZEROWASTE

PAGE 07ENERGYFROMWASTE

MANAGING WASTE

raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur 03

Ȗ The waste management business has always been an essential but unglamorous part of the economy, largely out of sight and out of mind unless something goes wrong.

But there has been a quiet revolu-tion going on in the last few years that has led to a change of outlook and a new approach.

Companies in the wider economy have to cope with concerns about the increasing scarcity and cost of raw materials. There is tighter regulation on waste disposal, with the landfill tax and a range of Euro-pean directives that demand prod-ucts, such as cars and consumer electronics equipment, are fully recyclable once they reach the end of their useful life.

There is also a growing concern about the amount of waste that companies – and society at large – are producing.

Every year, “well over one billion tonnes of waste is generated along food and agribusiness supply chains around the world, and almost 2,000 cubic kilometres of water, or more than 500 million Olympic-size swimming pools, are required to produce this wasted food”, accord-ing to a report by Rabobank Food & Agribusiness Research.

This combination of pressures

is making companies look more closely at the waste they pro-duce. “We have to treat waste as the raw material for tomorrow’s products,” says Alan Knight, sus-tainability director at Business in the Community.

And the waste industry is having to change as a result.

Waste is one of the economy’s “golden sectors”, says Steve Lee, chief executive of the Chartered Institute of Waste Management, because it is one of the industries, like water and energy, which ties all the other parts of the econ-omy together.

“This is the most exciting and forward-looking time I have ever seen in the industry,” Mr Lee adds. “The industry is moving away from the role of being a coping indus-try, where our job was to receive whatever society threw at us and make it go away. Now the industry is about resource management imperatives. We can’t lose sight of the fact that we still keep the streets clean, but we are using more of the waste in a productive way than ever before.”

Materials, such as rare minerals, which are used in products rang-ing from consumer electronics to wind turbines, are expensive, says

Nicola Jenkins, associate director at the consultancy Anthesis. “If you can bring them back into the system, you are cutting the cost of your raw materials,” she says.

As a result, the waste sector’s customers – and competitors – are changing. “Manufacturers who need resources might want to get into this space; mining companies might want to do the same, espe-cially when you think that there is more gold in a New York landfill

site than in a typical gold mine,” says Dr Knight.

“Waste management companies can have a very strong role in this new resource-conscious econ-omy,” says Dr Forbes McDougall, corporate solid waste leader, global product stewardship, at Procter & Gamble. “But if they do not find solutions for our waste streams and we do, we will just take it away from them.

“They have to become materials management or resource manage-ment companies because, if they don’t, they will lose their competi-tive advantage. If they come to us and say they can turn our waste costs into recycling revenue, we’re going to listen to them.”

This is what the industry is doing. “We can see that landfill is coming to an end. It never used to matter what came into our facilities. It was all just waste,” says Richard Kirk-man, technology director at Veo-lia. “We’re now focused on what materials we can recover. We have had to put in place a huge change management process. We have had

to up-skill our staff. We didn’t have the mentality of manufacturers and that has had to change.”

This shift in mentality has been helped by changes in design that mean many products and packag-ing are easier than ever before to dismantle in order to recover mate-rials, while advances in technology have made it possible to separate and recycle more difficult products, such as Tetra Pak drinks cartons.

Rather than just being the recipi-

ent of other sectors’ waste, the industry is now starting to engage all the way up the value chain to engineer hard-to-dispose materi-als out of the system.

However, many industry figures say the policy environment in the UK is uneven. “Scotland, Wales and increasingly Northern Ireland are more forward-looking, and see this as important not just from an environmental point of view, but an economic and social point of view as well,” says Mr Lee. “The coalition does not see it that way. The English approach is based more on compliance because the government doesn’t want any bur-dens on the public purse. I think they are missing a trick.

“This industry is part of the green growth opportunity for jobs, skills and resource security.”

Nonetheless, he adds: “It was not so professionally satisfying to be the industry that coped with what people threw at us. It’s much more fulfilling to be the industry that helps to manage resources more efficiently.”

Recycling waste into valuable raw material is transforming the industry’s outlook, as Mike Scott reports OVERVIEW

WASTE IS NO LONGER JUST A RUBBISH INDUSTRY

There is more gold in a New York landfill site than in a typical gold mine

DISTRIBUTED IN

PUBLISHING MANAGERDavid Kells

COMMISSIONING EDITORMike Scott

MANAGING EDITORPeter Archer

FELICIA JACKSONEditor at large of Cleantech magazine and author of Conquering Carbon, she specialises in issues concerning the transition to a low-carbon economy.

JIM McCLELLANDSustainable futurist, speaker, writer and social-media commentator, his specialisms include built environment, corporate social responsibility and ecosystem services.

SARAH MURRAYSpecialist writer on environmental sustainability and corporate responsibility, she is a regular contributor to the Financial Times and other leading titles.

TIM PROBERTFreelance energy journalist, he was formerly deputy editor of Power Engineering International and an editor of commodity reports.

MIKE SCOTT Freelance journalist, specialising in environment and business, he writes regularly for the Financial Times, Bloomberg New Energy Finance and 2degrees Network.

CONTRIBUTORS

PRODUCTION MANAGERNatalia Rosek

Although this publication is funded through advertising and sponsorship, all editorial is without bias and sponsored features are clearly labelled. For an upcoming schedule, partnership inquiries or feedback, please call +44 (0)20 3428 5230 or e-mail [email protected]

Raconteur Media is a leading European publisher of special interest content and research. It covers a wide range of topics, including business, finance, sustainability, lifestyle and the arts. Its special reports are exclusively published within The Times, The Sunday Times and The Week. www.raconteur.net

The information contained in this publication has been obtained from sources the Proprietors believe to be correct. However, no legal liability can be accepted for any errors. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior consent of the Publisher. © Raconteur Media

Share and discuss online at raconteur.net

DESIGN, ILLUSTRATION, INFOGRAPHICSThe Surgery

Colourful waste doors brighten

up a building site in South Korea’s

capital Seoul

04 05raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur04 05

MANAGING WASTE MANAGING WASTE

Ȗ By allowing its customers to upgrade early, Vodafone is satisfy-ing demand among mobile phone consumers for the very latest devices. Looked at another way, however, the company is now leas-ing rather than selling handsets, giving it a means of retrieving and recycling equipment.

As the rising cost of materials, as well as legislation such as Europe’s Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) directive, increase the pressure to return materials to the industrial sup-ply chain, the idea of a circular economy is gaining momentum.

But some argue that, if the con-cept is to take hold on a massive scale, radical shifts in mindset will be needed and companies must learn to work more closely with each other.

Certain models provide easy wins for companies and consum-ers. For Vodafone customers on a 24-month plan, the new Red Hot programme gives them access to the latest devices by allowing them to upgrade 12 months early.

At the other end of the chain, companies adopting this type of model – another is O2 Lease, a smartphone leasing service – can sell their phones into secondary markets or to recycling companies that extract the valuable materials from them for reuse.

What is interesting about such business models, however, is that companies are not necessarily promoting the idea of green or sustainable products. Rather, the appeal for mobile phone consum-ers lies in the ability to get hold of the latest model as soon as it comes out.

“They don’t tell you you’re leasing it; they tell you you’ll get access to the best performance and because of the business model, they can

Taking a circular, rather than linear, approach to production and designing products with recycling in mind saves money – and the Earth, writes Sarah Murray

CIRCULAR ECONOMY

INNOVATION

WHAT GOES AROUNDCOMES AROUND…

TOP TECHNOLOGIESMAKING A MARK

Often opportunities are missed because companies are unaware that other businesses could find uses for their waste

Bottle deposits

Page 08

give you a better deal,” says Jamie Butterworth, chief executive of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which is working with companies such as Cisco, Philips, Renault and Kingfisher to accelerate the transi-tion to the circular economy.

Of course, in some ways the idea of the circular economy is nothing new. The cradle-to-cradle phi-losophy of production and manu-facturing pioneered by William McDonough and his consultancy, MBDC, has been around for more than a decade.

The idea of taking a circular, rather than a linear, approach to industrial production, also referred to as closed loop manu-facturing, has long been embraced by companies such as Desso and Interface. Both flooring companies have developed innovative recy-cling technologies.

For Umicore, the Belgium-based materials technology group, the shift to the re-use model started in the 1990s, when the company transformed its business by exiting its traditional mining operations to become a specialty metals refining, recycling and recovery business.

Developing advanced recycling technologies was part of this. “And metals can be recycled infinitely without losing any of their physi-cal chemical properties,” explains Marc Grynberg, the company’s chief executive.

Umicore can retrieve precious metals from everything from min-ing and industrial waste to the circuit boards from old computers and mobile phones.

Its transformation was prompted by the need to address the negative environmental impact associated with mining and smelting. “We started with a problem to fix,” says Mr Grynberg. “But as we moved in this direction, we found there were opportunities that others could not seize.”

Often these opportunities are missed because companies are unaware that other businesses could find uses for their waste.

It was for this reason that Peter Laybourn founded International Synergies. Its National Industrial

Symbiosis Programme (NISP) uses resource matching work-shops and other means of sharing knowledge to help companies explore whether their energy and by-products can be turned into valuable resources that can be sold to other companies.

In the UK, for example, NISP helped Denso Manufacturing, which makes air conditioning units, engine cooling systems and automotive components, find a way to remove the moisture from the filter cake produced in its effluent treatment plants so that it could be used by other-companies.

When crushed, the cake becomes an active agent in the absorption of oil and solvent. This agent can then become a fuel source and the residual ash can be used to improve the qual-ity of soil. Meanwhile, Denso is saving £30,000 a year.

Intermediaries such as NISP play a critical part in the circular economy, argues Mr Laybourn, by filling information gaps and

acting as a matchmaker for com-panies. “The key success factors are bringing people from different sectors together face-to-face and having good, clean, accurate data,” he says.

Mr Grynberg believes companies must start thinking about resource management in a different way. “You need to move from seeing sustainability as a set of additional constraints, like having to reduce your CO2 footprint or water use, to detecting new opportunities if you work differently,” he says.

As raw materials continue to rise in price, these opportunities look increasingly compelling. “What we’ve seen in the past ten years is

a significant increase in the price of energy, metals, and agricultural and non-agricultural commodi-ties,” says Mr Butterworth of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. “And that’s really beginning to drive some action.”

This is why the foundation has done research to quantify the financial benefits of the approach. It reckons that, if companies work together to build circular supply chains which dramatically increase recycling and re-use rates, $1 trillion a year could be added to the global economy by 2025. “Putting a figure on the size of the prize gains a lot of interest,” says Mr Butterworth.

PLASMA ARC

Ȗ One of the most exciting innovations in waste to energy, this involves a plasma arc which ionises waste to create syngas and slag. Air Products is constructing a plant on Teesside using Altern NRG technology; while in Canada, Plasco is operating a full-scale 50,000-tonne plant transforming municipal waste into syngas.

The challenge with plasma arc is high parasitic loads, making it an expensive approach to waste management.

However, at Stopford Projects Dr Ben Herbert says the group is working on a small plasma demonstration plant with a major utility and power generator. The new plant is using a new pro-cess utilising microwave to generate heat, creating a far lower parasitic load, with lower operating and capital expenditure.

SEWAGE MINING

Sewage waste is a rich source of energy and materials, especially high in fats. When not properly managed it can mean clogged sewers – remember the infamous London fatberg – and high-cost cleaning. Removing this waste to generate new products could prove the future of waste management.

Ostara has developed a process that takes 80 to 90 per cent of phosphorus and nitrogen out of waste water, removing con-taminants and developing a secondary product – an effective non-water soluble fertiliser. The company is already operating a plant for Thames Water, as well as five in the United States and one in Canada.

Isreael’s Applied CleanTech has developed a sewage mining system, which picks out and recycles useful fibres from raw urban and industrial waste water, increasing the efficiency of treatment plants and reducing the amount of unwanted sludge and the cost of waste water treatment by 20 to 30 per cent.

BIOPLASTICS

The development of bioplastics and other plant-based materials could have a dramatic impact on industrial reliance on petro-chemicals, being not just biodegradable but compostable. It could also address waste by-products in the supply chain.Biome Bioplastics, for example, develops its products and materials from potato starch, a by-product of the wallpaper paste industry. According to director Paul Mines, the company has already developed a plant-based material for biodegrad-able coffee pods, offering one of the first sustainable packaging alternatives in the single-serve market.

“We’ve had traction in high-value, relatively niche sectors, like coffee pods, disposable razors, even tree protectors for horticul-ture,” he says.

While the cost of bioplastics is currently two to three times that of oil-derived plastics, Mr Mines expects to see rapid devel-opments in industrial biotechnology. He says: “I can see a path where we can make cheaper bioplastics, probably within three to four years.”

In conclusion, Allan Barton, Arup’s director and global leader, resources and waste management, advises: “There are two basic approaches to take. If the waste is organic, then cycle as nature intended by burning or composting. If it’s inorganic, then cycle it around and around the supply chain. We need to look at the waste stream as a source of materials to refine, just as petrochemical companies refine oil."

Felicia Jackson examines new technologies in the waste sector and assesses their impact

A YEAR COULD BE ADDED TO A CIRCULAR

GLOBAL ECONOMY BY 2025

Source: Ellen MacArthur Foundation

$1trn

NEW JOBS COULD BE CREATED FOR THE NEXT FIVE YEARS

100,000

Source: NISP

OF CO2 EMISSIONS CUT BY UK COMPANIES WORKING WITH NISP

42m tonnes

48m tonnes

OF WASTE REDIRECTED FROM UK LANDFILL

07

MANAGING WASTE

raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur06 raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur

Ȗ Every year the average per-son in the UK generates 500kg of waste. Of this, half usually ends up in landfill. Driven by the EU direc-tives on waste, for which the UK must reduce landfilling to 35 per cent of biodegradable municipal waste on 1995 levels by 2020, Brit-ain is making strides to turn waste into energy and wealth.

Energy from waste (EfW) is not particularly new. Landfill gas has been used for decades and gener-ates more than 5,000GWh a year of electricity from over 1GW of installed capacity.

Similarly, the large, typically 250,000 tonnes a year waste-to-energy plants burning unsorted, municipal solid waste (MSW), popularly known as incinerators, generate around 2,300GWh a year from approximately 600MW of installed capacity.

The landfill tax introduced in 1996, which saw councils charge a tax of £8 a tonne of material disposed in landfill, is perhaps the single most effective piece of legislation to incentivise efficient waste management practice. It has transformed the perception of waste to that of being a resource. A landfill tax escalator has seen the level steadily rise to £80 a tonne, with Chancellor George Osborne putting a floor under this figure until 2020.

Moreover, almost all EfW pro-jects are eligible for three main revenue streams. These are the gate fee paid for processing waste instead of paying the landfill tax;

the sale of the produced electricity; and one of two incentive regimes – renewable obligation certificates and feed-in tariffs.

Although so far not widely deployed, the Renewable Heat Incentive offers an additional inducement primarily for CHP (combined heat and power) anaer-obic digestion (AD) plants. Non-CHP incinerators do not qualify for support.

Local opposition to thermal treatment technologies or incin-erators can be fierce. Concerns are often raised about the health

implications and the wider envi-ronmental impacts of burning waste. However, government and the industry argue the evidence shows the thermal treatment of waste is safe, while plants using cleaner technologies, such as advanced gasification and pyrolysis systems, which create synthetic gas and reduce air pol-lution, are increasingly common.

But there are fears market saturation has created overcapac-ity and undersupply of energy feedstock, with some councils locked into punitive contracts to provide waste to incinerators instead of recycling. Indeed, fears about potential white elephants have forced the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs to withdraw hundreds of millions in funding to build new incinerators.

According to Nigel Aitchison, partner and co-head of environ-mental at investment management

Harnessing energy from waste enables companies to cut costs as well as carbon emissions, but there is potential for greater progress, as Tim Probert discovers ENERGY

ENERGY FROM WASTE IS GENERATING INTEREST

firm Foresight Group, talk about overcapacity is misplaced. He says: “When people talk about over-capacity they tend to talk about municipal waste, not the full waste market including commercial and industrial (C&I) waste produced by manufacturers, industry, hotels, restaurants and so on. In dry recy-clables, there may be overcapacity and a number of facilities have closed, but there haven't been any closures of EfW plants.”

The trouble is nobody is quite sure how much waste there is available or will be in future. It is widely accepted that the waste datasets are not fit for purpose.

Waste management consultancy Ricardo-ASA assumes that by 2020, there will be 53 million tonnes of MSW, C&I, and con-struction and demolition waste in need of treatment at thermal, organic and sorting facilities. On current capacity projections, how-ever, this is 15 million tonnes more than both the operational facilities and known infrastructure likely to be delivered by 2020.

The absence of reliable waste data is a major hindrance to inves-tors; this applies to both the quan-tity of waste and the detailed infor-mation about its composition. The lack of sound data using a common methodology makes putting a busi-ness case together challenging and one of the core reasons for limited financing for new infrastructure.

“What we’ve seen is a number of EfW projects that haven’t gone for-ward, not because they haven’t got the land or planning permission, but because they didn’t adequately structure the project in a way which meant it was investable,”

The landfill tax has transformed the perception of waste to that of being a resource

says Mr Aitchison. To this end, the role of the Green Investment Bank (GIB) as a cornerstone investor is increasingly important, particu-larly for larger EfW projects.

Foresight Group recently forged a consortium with the GIB to construct a £47.8-million 10.3MW recovered wood gasification pro-ject in Birmingham. The GIB also invested £20 million in a 49MW waste-to-energy plant on Teesside in a consortium of SITA UK, Sembcorp Utilities UK and Japan’s Itochu.

Mr Aitchison sees AD as a signifi-cant area for growth. This uses nat-ural bacteria, which breaks down waste to produce biogas for power and heat generation, and slurry which can be used for fertiliser.

AD accounts for more than 500GWh a year of electricity gen-eration from 122MW of installed capacity, a tenfold increase in only five years. There are two main segments of AD – source-generated food waste (SSFW) and on-farm AD. SSFW units tend to be the larger of the two, typically 1 to 1.5MW with approximately 30,000 tonnes a year capacity. On-farm AD typically comprises sub-500kW units.

The planning process for AD is considerably less controversial than larger waste management incinerators because they are smaller, less intrusive facilities and are usually designed to manage locally sourced waste. Mr Aitch-ison has an eye on a possible move to ban food to landfill, as proposed by the Labour Party should they be successful at the 2015 general election, as giving a big boost to the AD sector.

Figures from the Waste & Resources Action Programme estimate 7.3 million tonnes of food waste is produced by UK households each year. “There is a progression to incentivising this,” says Mr Aitchison. “A landfill ban on food waste, which some peo-ple have said would be difficult to police, would undoubtedly be a benefit.”

There are some caveats. The UK as a whole is poor at collecting waste material, with more than 100 different ways used to collect waste, be it bag, box or bin. Indeed, most local authorities do not col-lect food waste separately.

Furthermore, the Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC) last month confirmed feed-in tariffs for AD would be cut by 20 per cent, which the Renewable Energy Association fears will make some sub-500kW projects uneconomic.

If the Labour Party gets in in 2015 and keeps its pledge to ban food waste from landfill, however, AD is likely to be back in vogue.

Source: DECC

Source: Ricardo-ASA

Source: Waste & Resources Action Programme

OF UK ENERGY FROM WASTE GENERATION CAPACITY

599mw

OF UK WASTE REQUIRING TREATMENT IN 2013

102.7m tonnes

7.3m tonnes

OF FOOD WASTE PRODUCED BY UK

HOUSEHOLDS EACH YEAR

Share and discuss online at raconteur.net

An energy from waste incinerator on Teesside

Achieving a circular economyis the responsibility of us allAs one of the UK’s leading recycling and resource management companies, SITA UK has a large role to play in the UK’s journey towards a “circular economy”, where all discarded resources are collected, processed and returned back to the manufacturing process, so that the cycle can start again

are always working to find new ways to make use of materials that would otherwise be landfilled and to improve the proportion of collected materials that can be recycled. For example, SITA UK is currently commission-ing the UK’s first end-of-life plastics facility, which converts plastics that cannot be recycled, such as micro-wave meal film lids, into diesel fuel.

“But improving recycling rates and diverting as much material from land-fill as possible requires the buy-in of everyone involved in the lifecycle of a product, from designer, through to manufacturer, retailer and consumer.”

Mr Hayward-Higham points out that collecting materials, which have been discarded, and feeding them back into the manufacturing cycle is not the fi rst step towards a circular economy.

“Design is one of the major cul-prits of waste and we need to think about how we can design products for their whole lifecycle,” he says. “By carefully considering design of products and packaging, we can minimise the amount of raw materi-als that enter the circular economy in the fi rst place, ensure they have a long lifespan before they are dis-carded and, fi nally, ensure they are easy to extract resources from to return to the manufacturing pro-cess at the end of their life.

“For example, products that are designed to be upgraded or reman-ufactured would allow for them to be returned, renewed, restyled and resold as an improved version of the original, which is the reason most of us ‘upgrade’. This already occurs in products, such as photocopiers, where the ‘chassis’ might be used a number of times, but each time it looks new, feels new, has new func-tions and still does the job.”

In fact, Mr Hayward-Higham says there are even wider, more funda-mental, cultural changes society can make as a whole to minimise waste.

“If you stand back and take a look at the reasons why materials have been discarded, you begin to think about changes we could make to the way we live our lives, which opens a huge number of opportu-nities,” he says. “For example, we could move towards a model where products are replaced by services, known as ‘servitisation’.

SITA UK, a subsidiary of SUEZ ENVI-RONNEMENT, is a recycling and resource management company, which serves more than 12 mil-lion people and handles 8.5 million tonnes of domestic, commercial and industrial waste each year. The company provides services for over 42,000 public and private-sector customers, and operates a network of facilities, including recycling, composting, biomass production, waste collection, energy-from-waste plants and landfi ll sites.

Although it might seem counter-intuitive, the ultimate goal of SITA UK is to operate in a world with no more waste, where best use is made of all discarded materials by feed-ing them back into the cycle of pro-duction and consumption, instead of losing them forever to landfi ll.

SITA UK’s technical development director Stuart Hayward-Higham explains why this isn’t a case of “tur-keys voting for Christmas” and why waste management companies only play a small, if not important, part in achieving a more sustainable model of consumption.

“The word ‘waste’ no longer means that something is lost forever, it only means that the producer of the waste no longer has a need for it. Oth-ers may be able to use it, or the raw resources, and that’s the job of busi-nesses like ours – to find a sustain-able use or users for the materials others throw away,” he says.

“Resource management companies

“For instance, householders buy drills to make holes, but they don’t necessarily need to buy a drill to make a hole; they just need access to one, perhaps through a short-term rental. This means that the drills can be managed through the hirer, and their repair and mainte-nance can be conducted in an eco-nomical way. The result is that they are used for longer and not thrown away by the householder when a part breaks or wears out.”

For many, the circular econ-omy is a slightly abstract con-cept, aand it is difficult for organ-isations and individuals to know what they can do to make a differ-ence. Increasingly, SITA UK is help-ing customers to make the shift to a circular and sustainable model by providing practical solutions.

For more information about SITA UK and its services, visit www.sita.co.uk

Design is one of the major culprits of waste and we need to think about how we can design products for their whole lifecycle

Stuart Hayward-Higham, technical development director, SITA UK, is responsible for technical and policy innovation, and has worked in the recycling and waste industry for almost 30 years

In partnership with SITA UK, Keep Britain Tidy has begun a national study to fi nd new ways of improving recycling rates in Eng-land’s major cities.

Recycling in England is fl at-lining and, while some areas of the country are reaching recycling rates near-ing 70 per cent, other areas are only achieving 15 to 20 per cent.

Among those authorities with the lowest recycling rates, many have densely populated urban areas, which pose a signifi cant challenge to e� ective recycling.

England is also facing the danger that it won’t achieve its EU 2020 recycling target of 50 per cent. However, despite this, the govern-ment has withdrawn funding and focus from sustainable resource use, placing its future in the hands of the waste management industry.

Keep Britain Tidy is looking for new and innovative ways to boost recycling rates in England’s cities by asking members of the public to come up with real-world solutions with the help of waste industry experts.

Volunteers from London and Man-chester, none of whom have any prior knowledge of the waste and recycling industry, are working alongside indus-try experts to find practical ways to encourage people to recycle more.

The solutions devised by these groups will then be tested by a wider independent public poll of more than 1,000 people, and the outcomes of both studies will be presented in a report and short fi lm in June.

Keep Britain Tidy’s campaigns and communications director Andy Walker says: “Tackling waste is something in which the public has a big role to play, but all too often debates about recycling do not include ordinary people.

“These sessions are an opportunity for the man, or woman, on the street to have their say on an important issue that a� ects us all.”

NATIONAL RECYCLING STUDY

8 9raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur

MANAGING WASTEMANAGING WASTE

8 09

One of the most effective means of diverting useful resources from waste is the introduction of a bottle deposit scheme, writes Felicia Jackson

BOTTLE DEPOSITS

TIME FOR RETURNOF OLD-FASHIONEDBOTTLE DEPOSITS

Ȗ Recycling glass can save 80 per cent of raw materials mined and, with recycled aluminium saving 95 per cent of the energy it takes to make new aluminium, the impact in terms of energy costs and CO2 emissions can be considerable.

Sweden offers a world-leading example of how to deal with waste from drinks bottles and cans. Operated by Returpack, a recycling company co-owned by the drinks companies and brewers in Sweden, the Swed-ish deposit return scheme sees a small deposit added to the cost of drinks which is refunded when the container is returned.

Pelle Hjalmarsson, chief executive of Returpack, says a key element of the system is that it was introduced and managed by the different stake-holders working together. “Eve-rybody had a very high interest in creating a well-functioning deposit system,” he says.

Implementation of the scheme has resulted in recycling rates of more than 90 per cent of its drinks containers. These are then made into new containers or, in the case of some of the plastic bottles, into clothing, bags and other goods.

There can be difficulties in the deployment of such a scheme, especially if there is push-back from retailers or producers. Clearly the ability to make manufacturers, fillers, packers and retailers work together has a critical role to play. In Britain, disagreements among the stakeholders about where the on-cost of recovery should be placed resulted in a compromise in UK packaging legislation.

The legislation sets percentage

targets for the recovery of card-board, glass, plastic and aluminium, and companies within the supply chain need to report a number of certificates or producer responsi-bility notes (PRNs) to regulators representing each year’s targets.

This shares the responsibility for recycling throughout the sup-ply chain, rather than encouraging co-operation, while at the end of the chain waste management companies had no specific obli-gation for recycling. Effectively it created a market for PRNs which, combined with rising landfill tax, meant a greater push

towards recycling, but not a holis-tic approach to reclamation.

There are three elements to the value of a bottle deposit scheme: the value of the materials retrieved themselves; fees to industry; and the value of unredeemed deposits. Allan Barton, Arup’s director and global leader, resources and waste management, says: “The beauty of reward schemes is that some people will act, some people won’t and that fraction will fund the programme.”

Mr Hjalmarsson admits that one of the biggest challenges can be consumer behaviour, especially outside the home. But, he says of the Swedes: “It’s in our blood to make deposits.” In the UK, as Will Griffiths of the Carbon Trust points out: “The challenge is con-sumer engagement and incentivis-ing them sufficiently.”

In Europe alone, more than 100 million people live in coun-

Litter rates would fall, our streets would be cleaner and recycling would increase dramatically

tries with bottle deposit schemes, including Norway, Denmark, Fin-land and Estonia. Rauno Raul, chief executive of the Estonian Deposit System, says: “The advan-tage of a deposit system, compared to other alternative or parallel sys-tems, is the fact that the monetary incentive – the deposit sum – guar-antees very high collection rates. Deposit systems usually can collect from 80 to 96 per cent of input.”

The impact of such a scheme can move far beyond simply man-aging part of the waste stream. A 2010 report by Eunomia, for the Campaign to Protect Rural

England (CPRE), demonstrated that a drink container deposit refund scheme (DRS) would greatly reduce litter and increase recycling rates. Running costs of around 0.8p per container would be supported by revenue from unclaimed deposits.

Hopes for a UK DRS were hit in 2011 when the government’s review of waste policy identified the high cost of running such a scheme as a barrier to success. The Industry Council for Research on Packaging and the Environment argued that encouraging the use of existing recycling process through kerbside collection would be bet-ter value for money. However, this ignores the importance of behav-iour outside the home.

Dominic Hogg, director of Euno-mia, says: “At the moment, council tax payers meet the costs of recy-cling, clean-up of litter and land-

RECYCLING WASTE BOTTLES INTO ASSETS

Share and discuss online at raconteur.net

fill, irrespective of their purchases. But under a drinks container deposit refund scheme, the costs of dealing with beverage packag-ing would be met by industry and by those who forego their right to the refund of their deposit. Litter rates would fall, our streets would be cleaner and recycling would increase dramatically.”

Following the victory of the Scot-tish National Party (SNP) north of the border in 2013, Zero Waste Scot-land ran a pilot scheme, which the group is now analysing to see what it would take to expand the project.

Iain Gulland, Zero Waste Scot-land’s director, says the SNP wanted to increase recycling rates, as well as the quality of recyclate, and to promote anti-litter cam-paigning. The pilot project con-sisted of ten sites, eight of which were reverse vending and two deposit return. He says that, while the report on the pilot will not be out until later this year, all the schemes were used and recycling rates increased.

“Our objective was to look at the impacts and at public accept-ance,” he says. “While there were

challenges, the pilot showed that rewarding people does work under certain circumstances.”

One of the big unknowns in the Eunomia study for CPRE was a monetary value for the disamenity or adverse impact of litter. A 2013 Eunomia study for Zero Waste Scotland on the indirect costs of litter showed that the disamenity value is higher than had previously been thought and so adds weight to the case for deposit systems.

As part of this work, Eunomia explored the links between litter and crime, and the effects of litter

on mental wellbeing. Focusing solely on crime, the annual costs attributable to litter, for Scotland, were identified as being up to £22.5 million. For mental health and wellbeing, the study estimated attributable costs for Scotland to be £53 million.

While the recycling system in the UK has worked reasonably well, the growing focus on recovering resources has meant that materi-als recovery is happening at many different stages and it can be dif-ficult when one particular stream is removed.

Peter Jones, director at Ecolat-eral, says: “The system is work-ing, but it’s crying out for reform. If you’re in the waste industry, it’s no longer economic to put waste in landfill, so the remain-ing options are composting or anaerobic digestion, or thermo-chemical treatment.”

Mr Barton, at Arup, adds: “We need an integrated waste strategy that will work on an international scale.” What this means is that schemes such as Sweden’s bot-tle deposit approach could have an impact through reducing one

waste stream and encouraging the exploitation of the remain-ing streams with a range of new technologies.

Estonia’s Mr Raul concludes: “The initiative has to come from the government side. That was the case in Estonia when the packag-ing and packaging excise law was introduced in 2004. It is very unlikely that producers or retailers would do something really serious in terms of recycling on their own. The state has to introduce and enforce a concrete framework of rules to get real results.”

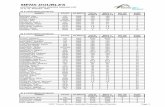

BEVERAGE DEPOSIT MODEL

EUROPEAN BOTTLE DEPOSIT SCHEMES

SOURCE: ZERO WASTE EUROPE

SOURCE: PLASTICS RECYCLING EXPOSOURCE: PETCORE EUROPE

SOURCE: RACONTEUR/EUNOMIA

WHOLESALERS AND DISTRIBUTION CENTRES STORE

POINT OF COLLECTION

CENTRAL SYSTEM (FINANCIAL CONTROL)

££££££ £££

BEVERAGE INDUSTRY

CONSUMER

DEPOSIT PAYMENT FLOWMATERIAL FLOW

GERMANY

NETHERLANDS

DENMARK

NORWAY

SWEDEN

FINLAND

ESTONIA

CROATIA

COUNTRIES/REGIONS WITH AN INSTALLED DEPOSIT SYSTEM FOR ONE-WAY CONTAINERS

COUNTRIES/REGIONS THAT ARE IN THE PROCESS OF EVALUATING A DEPOSIT SYSTEM FOR ONE-WAY CONTAINERS

PACKAGING INDUSTRY

Aluminum and plastic are also the most energy intensive of the three leading container types, each accounting for

It is estimated that every UK household uses

In the decade from 2001 to 2010, the value of wasted beverage container materials exceeded

plastic bottles each year

47%$22bnof the total energy lost when containers are landfilled or burnt

RECYCLERS (PROCESSING FACILITY)

500

10 11raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur

MANAGING WASTEMANAGING WASTE

10 11

ZEROING IN ONWASTE-FREE LIVINGWith the government under pressure to hit a 70 per cent recycling target by 2020, more businesses must embrace the environmental – and economic – case for zero waste, writes Mike Scott

Ȗ Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, wherever goods have been made, they have been accom-panied by the creation of waste. “It was just seen as the cost of doing business,” says Forbes McDougall, corporate solid waste leader in the global product stewardship team at Procter & Gamble (P&G).

But today, a growing number of companies, including P&G and other global giants such as car-maker GM, are working to ensure that their facilities do not send any waste to landfill.

P&G, which makes everything from toothpaste and shampoo to nappies and pet food, has already made 54 of its 160 sites around the world zero waste and plans to

have completed the process at 70 plants by the end of the year.

The rationale is quite simple, Dr McDougall explains: “Everything you divert from landfill is avoided cost.” With landfill tax soon to hit £80 a tonne, those costs are considerable. P&G believes it has saved more than $1 billion over the last five years by reducing waste. “You have already paid for these materials up front. If you don’t recycle it, you have to pay again to dispose of it,” he adds.

Businesses are realising that “they have to be part of a move from a linear economy to a circu-lar economy,” says Alan Knight, sustainability director at Busi-ness in the Community. “There

is a change in the business model from disposing of waste in landfills to a focus on resource recovery.

“Dumping stuff that is worth money on a planet that is running out of resources does not add up – we have to be smarter in the way we run society,” Dr Knight adds.

The move towards zero-waste economies has been driven in part by tougher regulation, such as the landfill tax and EU directives requiring the recycling of cars and electronic equipment, helped by a growing interest in sustainability from consumers. Companies are also more concerned about the increasing scarcity of many resources, their cost and the abil-ity to secure supplies, which these

Dumping stuff that is worth money on a planet that is running out of resources does not add up – we have to be smarter in the way we run society

Don’t rubbish the power of waste

The Climate Change Act 2008 estab-lished a target for the UK to reduce its carbon emissions by at least 80 per cent of 1990 levels by 2050 . It’s a challenging target and one that requires all sectors, including the waste industry, to reduce green-house gas emissions.

Reducing methane from landfill sites is one of the waste sector’s big-gest challenges in that regard. And with landfill tax becoming evermore expensive – from April it increases from £72 to £80 per tonne – the industry is seeking different treat-ment options.

One alternative is to use more of this active waste – the waste that remains after the recycling fraction has been taken out – as a feedstock for energy plants. Refuse-derived fuel (RDF), as it is known, can be used in a variety of treatment plants, including energy from waste (EFW), mechanical bio-logical treatment, anaerobic digestion and increasingly gasification, to gen-

erate electricity and heat.England and Wales currently use

about 5-6m tonnes of waste mate-rials for this purpose, but in the UK 19m tonnes is still landfilled, while just 1.5m tonnes (2013) is processed into RDF and exported to Europe where it is used as fuel in Dutch and Scandinavian energy plants.

So why are England and Wales only using a fraction of this valuable low-carbon feedstock, and land-filling and exporting the rest? The problem is one of capacity. Here in the UK there are simply not enough

plants to deal with the amount of waste produced.

The reason for this, according to Biffa Waste Services’ chief execu-tive Ian Wakelin, is the RDF mar-ket’s immaturity – everything from the lack of EFW infrastructure and planning delays for new plants, to a lack of confidence in the business case and hard-to-access finance for new plants.

“The economic case for both RDF production and energy production is unproven or at least in its infancy in the UK,” he says. “The challenge is then to secure finance for any facility either producing or using RDF.”

Planning delays don’t help, according to Jacob Hayler, an econ-omist at the Environmental Ser-vices Association.

“The problem is one of uncer-tainty. Developers have no idea how long it’s going to take to get plants built and any delay adds tremen-dously to costs,” he says.

economically and in terms of emis-sions reduction, could be substantial if these challenges within the energy-from-waste sector can be overcome.

“There is undoubtedly a strong commercial opportunity for RDF but, as ever in the waste industry, one that’s littered with challenges,” says Biffa’s Mr Wakelin. “It will be interesting to see who wins.”

References1 https://www.gov.uk/government/poli-cies/reducing-the-uk-s-greenhouse-gas-emissions-by-80-by-2050 2 See link to incineration spreadsheet: http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/research/library/data/150326.aspx) 3 (See Landfill Tax Bulletin: https://www.uktradeinfo.com/statistics/pages/taxanddutybulletins.aspx) 4 Environment Agency5 From interview with Hayler from the ESA

Instead of resorting to landfill, more waste should be used to power UK energy plants, says Biffa

“It’s a chicken-and-egg situation. We are exporting RDF because we don’t have the capacity to use it in this country, but we can’t build a busi-ness case for using it here because we’re currently exporting it.”

His solution to unlocking this conundrum is for the government to incentivise the use of heat gen-erated by energy from waste more than it currently does. Energy from waste plants operate at about 20-30 per cent efficiency if they only gen-erate electricity; if they use the heat generated as well, that rises to about 60-70 per cent .

This makes them more economi-cally viable and able to compete with European energy-from-waste plants, which are often subsidised by governments and can thus charge a lower fee than their UK counterparts for taking RDF waste, ensuring a regular feedstock supply.

Within the increasingly competitive waste industry, the rewards, both

Refuse-derived fuel can be used in a variety of treatment plants

NOSE TO TAILIN PARK LANE

CASE STUDY

A commitment to eliminat-ing waste is not necessarily what you would expect from a glitzy hotel – but that is what is happening at the Lancaster London on Park Lane, one of the capital’s most glamorous addresses.“We understand that as a hotel and food business, we have a massive carbon footprint,” says Eibhear Coyle, executive assistant manager for operations. “We wanted to reduce our impact.”The impetus came about when the hotel kitchens underwent a refit. “It was a massive investment and we wanted to make it sustainable for the next 25 years,” Mr Coyle adds. “One of the first things I did was to remove the waste compactors because they made it harder to change the culture among the staff. It is difficult to change the culture because zero waste means more work for staff, but people have bought into it.”One of the biggest con-tributors to the hotel’s waste was bottled water,

which used to result in 50,000 plastic bottles being thrown away every year. Now the hotel filters and bottles its own water in reusable bottles.In addition, Lancaster London asked its suppli-ers either to deliver food in crates that can then be reused or to decant sup-plies in the loading bay to reduce packaging waste.Another driver was a desire to achieve a rating from the Sustainable Restaurant Association. Front of house, the hotel’s restaurants and banquet-ing facilities adopted a “nose-to-tail” approach that reduces food waste by using “forgotten” cuts of meat that are often neglected. Not only did this reduce costs and the carbon foot-print of the dining facilities, but it has also become a selling point, particularly on the banqueting side. “The majority of our cus-tomers are big corpora-tions that have their own corporate social respon-sibility policies and this aligns with their values.”

place in an economy which tries to squeeze the most value out of each atom.”

The other aspect of zero waste is to rethink how products are designed and produced so they retain some value once they come to the end of their primary use, says Alban Foster, a director at SLR Consulting. “Zero-waste thinking demands that a business continually considers better ways of managing any materials that have the potential to be ‘waste’,” he says.

This can range from recycling aluminium drinks cans so they can be used to make new cans, to turning waste from one produc-tion process into a totally new product. P&G, for example, is turning toothpaste waste into jewellery cleaner, while UK com-pany Knowaste recycles nappies, turning them into plastic that goes into products from bike helmets to park benches and even flood defences. The process also produces fibre that is used for eve-rything from cardboard packaging to bricks.

“Nappies never rot. They would sit in landfill for at least 500 years,” says Paul Richardson, business development director at the company, which is hoping to build five to ten processing plants around the country that would be capable of dealing with some 40 per cent of the 1.1 million tonnes of nappies and hygiene products cur-rently sent to landfill every year.

Even waste management com-panies, which you would think is the one sector of the economy that would not embrace the zero-waste concept, are getting in on the act. “Our focus has changed from getting waste out of cities and into landfill to what materials we can find that have value,” says Richard Kirkman, technology director at Veolia.

Wastewater

Page 15

days come from all over the globe, in the face of challenges such as extreme weather events.

“Zero waste is about the econ-omy, it’s about jobs, it’s about sav-ings to industry – it’s not just an environmental thing,” says Iain Gulland, director of Zero Waste Scotland, which is charged with making Scotland a zero-waste economy by 2025. The move will create about 12,000 new green

jobs in the country, he adds.A zero-waste approach can cut

upstream costs and increase rev-enues by locking customers into your service, says David Bent, head of sustainable business at Forum for the Future. “For example, leasing out uniforms instead of selling them would save money for the consumer and vast amounts of resources. Businesses need to find their

Technological developments mean that metals can be extracted from street sweepings and plastics from sewage sludge, which can also generate heat and electricity.

“Ultimately, we’re going to need an economy where we don’t burden the natural world with waste,” says Forum for the Future’s Mr Bent. “We don’t need every company to be zero waste;

we just need each company to be able to sell its ‘waste’ as ‘food’ to another company – an open-loop economy. Companies need to experiment and invest in new business models where each link round the chain benefits from passing on stuff to the next user, so that nothing goes to waste.”

ZERO WASTE

12 13raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur

MANAGING WASTEMANAGING WASTE

12 1322

the exception. Until then, we and oth-ers are moving into prime position to take advantage of the many business opportunities afforded by what we hope will be the growing take-up of circular economy principles.

Time for change

With a number of notable excep-tions, the vast majority of global production is deeply unsustainable. It’s a “take-make-dispose” linear system that generates staggering amounts of waste and causes sub-stantial environmental damage.

Increasingly, businesses are look-ing at alternatives, one of which is the “circular economy”. This takes its inspiration from nature – that human systems should work like organisms, processing biologi-cal and technical inputs, which can be fed back into the process, and reused again and again. Zero waste is a key component of this process.

It’s not just a theory. There are businesses out there applying cir-cular economy principles, but they tend to be large corporates rather than smaller companies. If closed loop is achievable, why is it not more widespread throughout the busi-ness community?

Part of the problem is the frag-mented nature of the waste sector. This makes it hard for companies to offer national solutions to the larg-est waste producing sectors in the UK, including construction, which

comprises more than 70 per cent of Reconomy’s core business.

Progress towards circular econ-omy business models is happening, but a more collaborative approach between partners is required to make it more commonplace.

There is a lack of understanding, skills and knowledge of how com-panies can work together to achieve this aim. Businesses can overcome this by outsourcing their recycling and waste operations to a national provider which uses local supply networks. This reduces companies’ operational burden, allowing them to focus on waste reduction, re-use and minimisation strategies.

Reconomy ’s co l l abor at i ve approach enables us to come up with innovative ways to work with clients. As part of our recent part-nership with Travelodge, to date we have collected about 1,500 unwanted beds from the hotel chain and refurbished half of them for use by charities, such as British Heart Foundation. Not zero waste, but a step in the right direction.

Zero waste was, however, a condi-tion of Reconomy’s waste manage-ment work at the Olympic Aquatic Centre. We sent all waste that couldn’t be recycled to Northumber-land Wharf, east London, from where it was transported by barge along the Thames to a refuse-derived fuel facility. The constraints of the Olym-pic Park site and limited waste trans-port options meant we had to come up with a creative solution.

Infrastructure challenges aside, the business case for the circu-lar economy is clear – low or no waste means lower landfill costs. But judging by the few examples out there, this doesn’t seem to be enough of a driver. In the end, it’s the responsibility of both clients and the waste sector to come up with inno-vative ways to reduce waste.

To move towards a circular econ-omy, organisations need to break away from the traditional ways of doing things and explore new cross-sector partnerships with dif-ferent clients.

Waste operators should be pro-viding solutions for companies that bridge the skills and knowledge gap within the sector, and by work-ing together, aim to reduce waste as much as possible.

If this happens, it’s likely that compa-nies such as Reconomy will become the rule rather than, as they are now,

CO

MM

ERC

IAL FE

ATUR

E

The waste and business sectors need to work together in new ways if they want to exploit the commercial opportunities within the “circular economy”, says Paul Cox, managing director of Reconomy

Increasingly, businesses are looking at alternatives, one of which is the ‘circular economy’

70%

of Reconomy's core business is providing waste solutions to the

construction sector

1,500unwanted beds from Travelodge have been refurbished for use by charities such as the British Heart Foundation

65%

of the recycled beds were suitable for reuse, generating £57,000 for the

British Heart Foundation

LIVING INA MATERIALE-WORLDEnvironmental, cost and supply pressures are bringing about a shift in design priorities to avoid expensive waste of materials, notably in the electronics sector, as Jim McClelland reports

DESIGNING OUT WASTE

Ȗ Gold, silver and platinum will be among precious metals worth £1.5 billion purchased unwittingly in the UK between now and 2020. This hoard of hidden treasure will be scattered throughout ten mil-lion tonnes of electronic products bought by organisations, compa-nies and private individuals alike.

Electronic, digital and mobile technologies are big business. The marketplace is competitive, evolving constantly and rapidly. Sales are strong, not least because products date and break.

As a result, product and mate-rial recovery, recycling and reuse is also an area of rising concern – and opportunity. Waste electri-cal and electronic equipment (WEEE) is now the fastest growing waste stream worldwide, with an estimated two million tonnes dis-carded in the UK every year.

In response, new European Union WEEE regulations com-ing into force this year seek to encourage producers to consider the environment at disposal and end of life, designing out waste and adopting cradle-to-cradle (C2C) responsibility for products.

What will be the effect of these legislative changes? The new obli-gations carry potential implica-tions for all stakeholders and life-cycle stages, from design, though manufacture, to consumption and finally recovery. How will the market react?

“The majority of rethinking of e-waste is driven by clear and con-sistent regulatory requirements, primarily emanating from the European Commission,” explains Will Schreiber, co-author of the WRAP report Reducing the envi-ronmental and cost impacts of electrical products, and associate director at Best Foot Forward.

“Whether televisions or washing machines, the overall trend in the

electrical sector has been to make products less repairable and have shorter lifetimes,” he says. “The changes that we see in response to legislation, however, are starting to have an effect on the business mod-els some companies are developing by reducing hazardous substances, offering longer warranty periods or providing buy-back options.”

This emerging trend will ask questions of product designers, a community that has been relatively slow to respond to the waste issue creeping up the corporate and

regulatory agenda, according to designer and head of sustainability at Seymourpowell Chris Sherwin.

“I don’t think designers have considered the waste and disposal stages of products anywhere near as much as they should,” he says. “Most of what we do in design processes is to become the cham-pion of the consumer experience. The main problem with that is it misses off the front and especially the back-end aspects. We need a broader, more holistic approach.”

The conditions for change are gradually becoming manifest in electronics markets, with a com-bination of contributory factors in evidence, he says. “It is no secret that carbon/energy has been the main driver for the electronics sector, but companies are turning more to waste and resource con-sumption, driven by concepts like C2C, the circular economy, rising materials costs, better recycling and recovery infrastructure. It seems more of a priority in design now.”

Momentum in waste markets still seems more push than pull though, as Mr Schreiber describes the dynamic. “Unlike energy con-sumption, which has direct con-sumer benefits and therefore demand, material control and optimisation are mostly driven by

cost savings and regulations for critical raw materials, such as rare earths, Dodd-Frank [regulated] conflict minerals,” he says. “The biggest proponents of change have been the brands themselves setting a clear strategy. The problem is that few organisations have actu-ally looked at waste as a business opportunity rather than a burden.”

This limited response may well be explained in part by the weak signals being received in general from a customer base typically

still stuck in consumer mode, as Adam Read, practice direc-tor – waste management and resource efficiency, at Ricardo-AEA, explains: “Unfortunately, the drive of consumerism is a little like the Titanic – difficult to slow, almost impossible to divert and ultimately destined for failure. Although consumers may not be changing on their own, with strong government leadership, responsi-ble manufacturers and increasing public awareness that recycling is good, but waste prevention bet-ter, we can expect to see a shift in direction in the next decade or so.”

Are we nearing a tipping point? Sophie Thomas, co-director of design at the RSA and one of the founders of the Great Recovery Project, reimagining products and material flow cycles, seems to think so. She counsels though that things could yet go one of two ways, with the waste sector “either on the cusp of something great or the edge of a cliff”.

Dr Read concludes that breaking traditional take-make-waste para-digms depends on a clear business case emerging on the supply-side and a circle more material than virtuous. “Ultimately, we are fac-ing significant resource risks in the electrical products world, from rare-earth metals in particular, so price will continue to increase as scarcity worsens,” he says. “This will drive innovation in product design and processing, includ-ing more closed-loop solutions where electrical products are never owned, just leased/rented from manufacturers, thus ena-bling them to control the supply of increasingly valuable materials.”

For all the virtual community and cloud computing advantages afforded us by the latest electronic and mobile technology, the means to these online ends are still very much grounded in physical com-modities and mineral properties. Paradoxical as it might seem, we are living in a material e-world.

With strong government leadership, responsible manufacturers and increasing public awareness that recycling is good, but waste prevention better, we can expect to see a shift in direction in the next decade or so

Share and discuss online at raconteur.net

CASE STUDY

THIS YEAR’S MODULEIS A PHONEBLOK

There are now more iPhones sold every day worldwide than babies born and more mobile devices on Earth than people.Since the first call made on a 23cm-long 1.1kg Motorola in 1973, the accelerating rate of obsoletion means an average US cellphone is now kept for just 18 months. Despite leasing initiatives, cashback offers, drawers of “retired” kit, plus some reuse and recycling, global e-waste mountains are growing at a rate in excess of ten million mobiles a month.For innovation and disruptive technology to make a successful start tackling mobile-related resource consumption and waste, it is wrong however to assume size matters.As Phonebloks founder Dave Hakkens explains: “To tackle a big problem, you do not necessarily need a big solution. With the emerging technology empire soon to embrace the “internet of things”, even one solution – such as a mobile phone – to just one part of the bigger electronics problem still represents something of significance and starts the market shift to modular thinking.”Phonebloks launched last year via viral video and “crowdspeaking” social media, campaigning to demon-strate the mass-market appeal of modular and attract commercial production partners. Billed as “a phone worth keeping”, Phonebloks challenges the notion that electronics are not designed to last.A collaborative open-platform venture, the concept handset comprises detachable blocks – providing a processor and storage capabilities, camera and screen functions, for example – all connected through pins on a base. The modular nature allows easy upgrading of components.This same designed-in interchangeability also facili-tates customisation, described by Mr Hakkens as a demand priority identified in market research.“Talking to a diverse mix of technology users around the world, with different priorities and situations, the first rule of phone design we learnt is that there has to be more to a mobile than just battery life and megapix-els,” he says. “For some owners, being able to meas-ure diabetes indicators or monitor a heartbeat features much higher up the agenda than camera capability. Any solution that aspires to become universal must cater for the particular – customisation is key.”It is important for marketability that users can person-alise purchases with custom features and so invest in a sense of ownership, choosing blocks they want and supporting brands they like.Coming full circle, Phonebloks has now teamed up with Motorola, raising the prospect that modular might just answer the call for more sustainable mobile tech-nology begun four decades ago.

Motherboards from Panasonic

home appliances are recycled in

Kato, Japan

14 15raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur raconteur.net twitter: @raconteur

MANAGING WASTEMANAGING WASTE

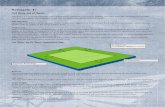

EXPLOITINGLIQUID ASSETSTHE GREAT RECOVERY

OF EARTH’S RESOURCES

Ȗ With global water stress an increasing worry to companies, governments and others, atten-tion is focusing on how to conserve this precious natural resource. However, as materials scarcity becomes more evident, another question is now on the lips of cor-porate leaders and policymakers – what value can be extracted from waste water?

Of course, part of the challenge is to prevent water from being wasted in the first place. The oil industry, for example, generates large volumes of waste water.

“They separate the oil and water, and inject it back into a salt water disposal well a mile underground and it’s never used,” explains James Wood, chairman and chief executive of US-based ThermoEn-

ergy. “That’s fine where you have enough water. But it’s not so good in west Texas, where they have very bad drought conditions.”

ThermoEnergy’s flash vacuum distillation technology is a phys-ical-chemical process that uses temperature and reduced pres-sure to separate chemicals, metals and nutrients from waste water. This technology, argues Mr Wood, could be used to turn the waste water produced by the extractive industries into water that could be used by farmers, particularly in areas of drought.

However, waste water contains rich seams of chemicals and min-erals, from nitrogen and phospho-rus to propylene glycol and heavy metals. Once viewed merely as a costly or even toxic problem to be dealt with, waste water and the materials it contains are increas-ingly being viewed as a means of creating value.

Nitrogen and phosphorus, for example, can create purification and algae blooms in waterways. Yet they are also valuable materials in the manufacture of fertiliser.

For this reason, Vancouver-based Ostara Nutrient Recovery Tech-nologies has developed a way of recovering phosphorus and nitro-gen from municipal and industrial waste water, and transforms them into fertiliser.

“The technology is very much geared towards making a market-able product,” says Phillip Abrary, Ostara president and chief execu-tive. “We’ve changed our mindset from seeing these things as a source of pollution to developing technologies that can take them out and turn them into something with the same or greater value.”

Many of Ostara’s clients are municipalities for whom the appeal is that they are able to tackle pollution on several fronts. While the technology enables the cleaning of waste water, the

Once considered a source of pollution, waste water now has fresh potential, writes Sarah Murray

The myth that our Earth can provide the human race with unlimited natural resources has been well and truly busted, says Sophie Thomas

WASTE WATER

OPINION

Ȗ The rising cost and restricted supply of materials that go into making the products we use every day is creating a global race for sup-plies of oil, gas, water, metals and minerals, and fuelling geo-political conflicts around the world.

And yet more than 30 tonnes of waste are produced for every one tonne of products reaching the consumer, 90 per cent of which are thrown away – mostly into landfill – within six months of purchase, according to the World Economic Forum.

This linear model of “take-make-dispose” is lending new meaning to the concept of fast-moving consumer goods and is throwing up

major economic, social and envi-ronmental challenges.

Ever since the Industrial Revolu-tion, businesses have pursued the model of “more, faster, cheaper”, but now, with growing extraction costs, increasingly volatile markets and the spectre of climate change upon us, it is time to rethink our basic systems of demand and sup-ply, manufacture and disposal.

The Great Recovery project was born at the RSA in 2012 in response to some of these global pressures. Along with my RSA co-director of design Nat Hunter, I set out to dis-cover what role design could play in the re-programming of our linear methods of production in order to achieve something altogether more circular, a system where products are continuously reused, repaired or reprocessed.

As a communications designer for many years, experience had taught me that much of our waste was, in essence, a design flaw. European Commission estimates show that more than 80 per cent of a product’s environmental impact is deter-mined at the design stage, largely through a lack of understanding, an uncaring brief and the lack of incen-tives to do anything differently.

The Great Recovery set out to challenge the case for “business as usual” by providing a space in which designers can come together with policymakers, manufactur-

ers, academics, waste managers, chemists, retailers and consumers to understand the challenges, and co-create the new processes and products that will be needed in a circular economy.

Over the last 18 months, we have been building these collaborative networks and using the practi-cal lens of the design industry to focus on some of the problems and opportunities involved in “closing the loop”.

Our programme of workshops and events set in the industrial landscapes of recovery and recy-cling facilities, disused tin mines and materials research labs has brought people from across all sec-tors to participate in “tear down” and “design up” sessions.

By literally pulling products off the recycling pile and taking them apart to understand how they are

currently designed, manufactured and disposed, and then trying to redesign and rebuild them around our four design models for circular-ity, we learnt some valuable lessons:

» The role of design is crucial to circularity, but very few designers understand or think about what happens to the products and services they design at the end of their life;

» New business models are needed to support the circular economy;

» The ability to track and trace materials is key to reverse engi-neering our manufacturing pro-cesses and closing the loop;

» Smarter logistics are required, based on better information;

» Building new partnerships around the supply chain and knowledge networks is critical.

This first phase of work also sup-ported the Technology Strategy Board, which has invested £1.25 million into a range of feasibility studies proposed by business-led groups and collaborative design partners, through its New Designs on a Circular Economy competition.

The inaugural 2014 Resource exhibition sees the launch of the next phase of work for The Great Recovery in a two-year programme that will bring together material-science innovators, design experts, leading manufacturers, and cru-cially, end-of-life specialists to explore the relationships between design, materials and waste.

Our growing “re-materials” library will be a tangible way for people to experience the innova-tions and challenges associated with circular-economy thinking: we may have efficient recycling facilities to reprocess certain mate-rials, for instance, but how are we innovating to create longer-lasting products or redesigning business models for service or leasing?

In a move to nurture disruptive thinking across the network, we will be developing short-term immersive design residencies that can set up inside recovery facilities around the UK. The design teams will be there to observe and expe-rience the complexity of recovery systems, and to help inform think-ing around current waste streams and new product designs.

As well as building our online platform and expanding our net-work with events and investiga-tions, we will be establishing the first innovation hub in central London. The hub will be a physical focus for the exchange of ideas, prototyping and experimentation, and will also host bespoke business workshops and consultations.

The Great Recovery is part of the Action Research Centre at the Royal Society for the Encourage-ment of the Arts, Manufacture and Commerce (RSA) and is supported by the Technology Strategy Board

With growing extraction costs, increasingly volatile markets and the spectre of climate change upon us, it is time to rethink our basic systems of demand and supply, manufacture and disposal

Often the extraction of materials from water is driven by legislation primarily designed to conserve water, preserve clean water or safely dispose of waste water

fertiliser Ostara produces with the recovered phosphorus and nitrogen is a slow-release product that, because it does not dissolve in water, prevents the run off of chemicals into surrounding rivers and waterways.

Often the extraction of materi-als from water is driven by legis-lation primarily designed to con-serve water, preserve clean water or safely dispose of waste water.

ThermoEnergy, for instance, developed its waste water treat-ment technology in New England after the introduction of federal standards for drinking water. The legislation – the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System – requires a disposal per-mit for any water being put into a sewerage system.

In New England, with a vibrant metal-plating industry, the legis-lation created demand for tech-nology that could clean dissolved metals, such as chrome, nickel and zinc, from the water these

companies use in the metal-plating process.

However, a second benefit of ThermoEnergy’s technology has emerged. “The metal-plating industry now uses this machine to recover metals they otherwise would have thrown away,” says Mr Wood.

Another use is in extracting gly-col used in the de-icing fluid that is sprayed on to planes at airports during freezing weather. “You have this flow back of water, from which they look to recover the chemicals because they are valuable,” he says.

Another extremely valuable com-modity that can be extracted from water is alginate. In the Netherlands, Delft University of Technology and a consortium of partners have developed Nereda, a low-energy technology that makes minimal use of chemicals to extract alginate from waste water.

The alginate is currently used in food and medical products, but could also potentially be used in

industries such as agriculture, chemicals, paper production and textiles.

With demand for raw materi-als rising, along with the price of these commodities, more of these kinds of technologies are likely to emerge. “As a growing population around the world, we need more of the things that we’re consuming and discarding – that’s a continu-ous trend,” says Mr Abrary. “So a sustainable source of materials and basic elements is key.”

Share and discuss online at raconteur.net

Sophie Thomas is co-director of design at the RSA and project director of The Great Recovery programme