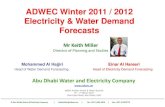

Winter 2011

-

Upload

campus-blueprint -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Winter 2011

BluePrintCAMPUS

WINTER 2011

8SUSTAINABLE CITIES

Dear Readers,

Whether it’s with projects in de-

velopment work, use of natural

resources, or a university dealing

with budget cuts, the buzz word

is sustainability. In a world with fi-

nite resources and seemingly infi-

nite problems, our solutions need

to be sustainable. We need cures

and prevention, not mere band-

aids. But while we all might rec-

ognize the need for sustainability,

the prevailing notion is that sus-

tainable solutions mean sacrific-

ing quality.

This is simply not so, and we

aim to highlight this in Campus

BluePrint. This issue focuses in on

one of the many types of applica-

tion of the concept of sustainabil-

ity: environmental sustainability.

Climate change and resource scar-

city are threatening to be two of

the deadliest forces of the twen-

ty-first century. Our generation

needs to reorient our lifestyles ac-

cordingly to combat these global

challenges. The theme for this is-

sue centers on sustainable cities

across North America and Europe,

including one of the most impres-

sive examples of a sustainable

city in the U.S., North Carolina’s

very own Raleigh.

Enjoy,

Chelsea Phipps

Editor-in-Chief

FROM THE EDITOR CONTENTS

On the cover:Man in Turban, Oil on Canvas ,

by Charlotte Lindemanis

chelsea phipps editor-in-chief

sarah bufkin assistant editor carey hanlin managing editor

sally fry creative director

cari jeffries photo editor

travis crayton social media editor

russell mcintyre treasurer

joseph biernacki, hayley fahey, troy homesley, molly hrudka,

akhil jariwala, alice martin, dinesh mccoy, rachel myrick,

jenn nowicki, libby rodenbough, kyle sebastian, luda shtessel, kyle

villemain, peter vogel, kelly yahner staff writers

carey hanlin, jasmine lamb, cassie mcmillan

production and design

anne brenneman, molly hrudka, cari jeffries, alice martin,

kyle sebastian, saurav sethia, kelly yahner copy editors

kevin diao, gihani dissanayake, hannah nember,

stefanie schwemlein, cary simpson, renee sullender ,

jennifer tran photographers

rachel allen, hayley fahey, charlotte lindemanis,

aaron lutkowitz, dinesh mccoy, jenn nowicki, wilson parker,

sarah rutherford, neha verma bloggers

STAFF

UNESCO Defunded

Chapel Hill: Fair Trade Town

Health Care: Vermont’s Plan

Sustainability in the Capital City

Restricting Abortion

Palestine in Poetry

Sudanese Art Exhibit

15PERSONHOOD AMENDMENT

18PHOTO ESSAY: ARAB SPRING

03040607

131620

WINTER MINI2011 • 3

After the United Nations Educational,

Scientific and Cultural Organization

formally recognized Palestine as an

independent state and a full member,

the United States withdrew its funding

from the cultural organization. Without

US funds, UNESCO will lose out on $80

million a year, approximately 22 percent

of its current budget, throwing up hefty

obstacles for the international institu-

tion.

In late October, the 195 member

states of UNESCO voted, with only 14

members dissenting, to admit Pales-

tine as a full member. The vote came

despite threats by the United States to

defund UNESCO if Palestine was accept-

ed. After the vote, cheers rang through

the chambers of the Paris-based organi-

zation as one delegate shouted, "Long

Live Palestine" in French. Soon after, the

United States acted on its promise to

defund the program with Israel follow-

ing suit.

The United States’ withdrawal of its

funds from UNESCO has already levied

massive implications upon the organi-

zation.

"So we have to take drastic action,

and we must take it now,” UNESCO Di-

rector-General Irina Bokova told UNES-

CO members at the organization’s gen-

eral conference. “I have suspended all

of our commitments. I have suspended

our projects during this period of revi-

sion until the end of the year.”

UNESCO understood the implica-

tions of admitting Palestine as a mem-

ber state, but this did not deter their

decisions. As Palestine continues to

gain recognition around the world, the

United States must decide whether to

support independence or lose their

standing in international institutions

by eliminating funding. Irina Bokova

revealed this sentiment following the

UNESCO vote in support of Palestine

when she clarified that although she

is worried about the financial stability

of the organization, the "admission of a

new member state is a mark of respect

and confidence."

UNESCO aims to contribute to peace

and security by promoting international

collaboration through education, sci-

ence, and culture in order to further

universal respect for justice, the rule

of law and human rights along with

fundamental freedoms proclaimed in

the U.N. Charter. UNESCO is known for

its support of international literacy, cul-

tural understanding, human rights and

the promotion of free and independent

media sources.

After such a massive victory within

UNESCO, Palestinian leaders hope that

this recognition will set a precedent for

recognition in other international insti-

tutions.

"Now we are studying when we are

going to move for full membership on

the other U.N. agencies,” said Ibrahim,

Khraishi, Palestine’s top UN envoy. “It's

our target for [us to join] the interna-

tional organizations and the U.N. agen-

cies.”

As Palestinian leaders begin to apply

for recognition by international institu-

tions such as the World Health Organi-

zation and the U.N. World Intellectual

Property Organization, many are ques-

tioning how long the United States

can justify its withdrawal of funding to

organizations that recognize Palestine.

Current U.S. law requires the defunding

of any organization that recognizes the

Palestine Liberation Organization as an

equal to member states. •

TROY HOMESLEY

UNESCODEFUNDED

PHOTO BY WIKIMEDIA

4 • WINTER MINI2011

Fair trade in the United States is go-

ing through an identity crisis. Fair Trade

USA, the largest fair-trade certification

organization in the United States, re-

cently split from the International Fair

Trade body in order to pursue more

business friendly policies.

While the larger movement is debat-

ing whether fair trade is moving away

from its roots, locally the movement is

going strong.

Starting in the spring of 2010, soci-

ology professor Judith Blauh and her

class petitioned local businesses and

UNC students to build support for fair

trade in Chapel Hill. In June, the Chapel

Hill Town Council passed a resolution

officially supporting the fair-trade mod-

el and thereby completing the first of

five steps necessary for Chapel Hill to

be officially recognized as a Fair Trade

Town.

Becoming a Fair Trade Town would

provide a big boost in marketing Cha-

pel Hill as a sustainable city, according

to Keilayn Skutvik, the manager of Ten

Thousand Villages in Chapel Hill. Ten

Thousand Villages is one of the found-

ing members of the World Fair Trade

Organization and sells crafts from thir-

ty-eight different countries throughout

the United States.

Ten Thousand Villages is not alone in

pioneering fair-trade in the Chapel Hill

area. Open Eye Café, a locally-owned

coffee shop in Carrboro, is widely known

for its high-quality coffee as well as its

dedication to fair trade.

Chapel Hill

FAIRTRADETOWN

KYLE VILLEMAIN

“We’re hoping that younger and younger people start shopping

with a conscience.”

WINTER MINI2011 • 5

Its success in fair trade is partially

due to its partner business, Carrboro

Coffee Roasters.

Carrboro Coffee Roasters is able to

buy directly from producers because it

is a wholesale store, not a retail store,

according to co-owner Scott Conary. Re-

tail stores are more dependent on third-

party suppliers who act as middlemen

between producers and stores.

Carrboro Coffee Roasters, however, is

able to develop personal relationships

with the growers, and as a result buys

seven of its coffees directly from coffee

growers.

Currently, Carrboro Coffee Roasters

is building its eighth partnership with

a farmer in Guatemala. Conary just re-

turned from a visit to the country where

he met with the coffee grower.

Building each relationship is differ-

ent, Conary says. Sometimes he sam-

ples the coffee and backtracks to meet

the farmer while other times he learns

about the farmer first and then tries the

coffee.

The relationships Open Eye Café has

built via Carrboro Coffee Roasters have

insulated the coffee shop from some

of the recent turmoil in the fair-trade

industry. The coffee segment of the fair-

trade movement has especially been

undergoing change.

Fair trade is designed to ensure a fair

living wage is paid to the growers and

producers of fair-trade goods; it essen-

tially promises a minimum price so that

producers can rest assured that they

will have a steady income.

In the commodity market, however,

the price of coffee has more than dou-

bled in just six months. And that is just

the price of commercial-grade coffee,

which is far from the quality coffee that

Open Eye Café sells.

The high price of coffee, however,

means that producers are now charg-

ing a higher price than the fair-trade

price, rendering the latter meaningless.

The long-term partnerships that Co-

nary and fellow co-owner Beth Justus

have established, however, ensure that

the huge spikes in the commodity mar-

ket that send coffee prices soaring do

not bankrupt Open Eye Café and future

drops in the commodity market that

send coffee prices plummeting do not

bankrupt the coffee growers.

Elsewhere in Chapel Hill and Car-

rboro other fair-trade businesses are

also growing. Weaver Street Market

in Carrboro buys fair-trade wine and

chocolate, among other goods, and it

works to make sure its suppliers are

paid enough money per pound to sup-

port the cost of production, regardless

of the whims of the global market.

Ben and Jerry’s, Café Driade, Whole

Foods and Twig – selling ice cream, cof-

fee, groceries and “eco-friendly special-

ty goods,” respectively – are all listed as

fair-trade stores by Fair Trade Town USA,

the organization that Ten Thousand Vil-

lages is working to have recognize Cha-

pel Hill as a Fair Trade Town.

To be recognized, Chapel Hill now

needs to include community outreach,

and Skutvik is planning on doing just

that. The steering committee is the next

concrete step, while raising general

awareness is also a priority. She hopes

to also involve university students and

possibly even work to make UNC recog-

nized as a Fair Trade University. Today,

customers at Ten Thousand Villages are

mainly female and generally older.

“We’re hoping that younger and

younger people start shopping with a

conscience,” Skutvik said.

On a national level, Fair Trade USA,

the American fair-trade group that has

come under criticism for adopting more

business-friendly practices, is working

to spur big growth, with a goal to dou-

ble fair-trade sales by 2015. Its methods,

which include allowing factories and

plantations to earn fair-trade certifica-

tions, may undermine the principles

of fair trade or may allow it to have a

greater impact than it ever has before.

In Chapel Hill and Carrboro, however,

it seems that regardless of the state of

the national fair-trade movement, lo-

cal businesses will continue to provide

ethically-purchased goods that benefit

both the consumer and the producer.

Skutvik looks to the organic movement

as a blueprint for the future of fair trade

in the community.

“If you look at the organic food indus-

try in the 80s and 90s, it was driven by

increasing consumer demand,” Skutvik

said. “People need to demand to know

[where the goods come from] and that

will make retailers accountable.” •

6 • WINTER MINI2011

VERMONT’S NEW PLAN

“We gather here today to launch the

first single-payer health care system

in America, to do in Vermont what has

taken too long…,” Vermont Governor

Peter Shumlin said earlier this year as

he signed into law the bill that would

make his state the first in the nation

with full publicly funded health care.

According to Vermont’s Health Care Re-

form website, the plan, called Green

Mountain Care, would provide “unin-

sured Vermonters with access to quali-

ty, comprehensive health care coverage

at reasonable costs.”

“We must control the growth in

health care costs that are putting fami-

lies at economic risk and making it

harder for small employers to do busi-

ness,” Shumlin said. He also said the

law “recognizes an economic and fiscal

imperative.”

Under Green Mountain Care, Vermont

hospitals will be paid a set amount of

money to provide care for citizens of

the state, who in turn will pay a set

monthly premium based on income

and members per household. As with

the Patient Protection and Affordable

Care Act signed by President Barack

Obama last year, Green Mountain Care

will completely overhaul the traditional

method of paying doctors on a per-visit

basis. But Green Mountain Care is not a

part of PPACA; in fact, the state had to

opt out of the federal health care plan

before Shumlin could sign the bill into

law, which proved tricky.

According to the Daily Kos, President

Obama initially wanted to strip out

an ACA amendment that would allow

states to create their own single-payer

health care systems. But progressive ra-

dio host Thom Hartmann attributed Ver-

mont’s difficulties more to Republican

lawmakers than to President Obama.

“…Republicans are trembling at the

thought of Vermont having a single-

payer health care system to serve as a

model for other states,” he said. “Can-

ada’s single-payer health care system

started in just one province – Saskatch-

ewan – and then spread across the

country because people in other prov-

inces demanded it.”

Shumlin’s critics say that while the

plan promises to provide adequate

low-cost health care, the bill doesn’t

require the governor to develop a con-

crete way to pay for it until 2013 – after

Shumlin campaigns for a second term.

But proponents insist that while the

bill still needs to be improved in some

ways, it will ultimately improve the

quality of health care by discouraging

unnecessary care while encouraging

coordination.

But one of the central aspects of the

plan is its ability to cut costs. According

to the Green Mountain Care website, a

family of four earning approximately

$41,500 annually will have a monthly

premium of about $49 per person,

while a family of four earning less than

$11,225 annually will have no month-

ly premium to pay at all. In an age

where the average family can expect

to pay thousands of dollars annually

on health insurance premiums, such a

single-payer health care program has

to sound less like socialism and more

like common sense.

CAREY HANLIN

”...Republicans are trembling at the thought

of Vermont having a single-payer healthcare

system to serve as a model for other states...”

WINTER MINI2011 • 7

Communities within North Carolina no

longer need look to European cities as

paradigms of sustainability. A mere 30

miles from Chapel Hill, the city of Ra-

leigh has been nationally recognized

for its green ventures.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Chamber of

Commerce named Raleigh the “Nation’s

Most Sustainable Mid-Size Community.”

The award lauded a “Sustainable Ra-

leigh” initiative, which addresses three

elements of sustainability: economic

strength, environmental stewardship

and social equity. The city integrated

these principles into its local gover-

nance through two endeavors, the En-

vironmental Advisory Board and the Of-

fice of Sustainability.

John Burns serves as the chair of the

Environmental Advisory Board, which

Mayor Charles Meeker started back in

2007.

“The board exists to advise the city

council on matters related to environ-

mental quality and to promote com-

munication among various elements

of city government relating to environ-

mental protection and sustainability,”

Burns said.

The board’s recent accomplishments

include endorsing the U.S. Mayors Cli-

mate Protection Agreement, developing

a greenhouse-gas reduction strategy

and drafting Raleigh’s 2030 Compre-

hensive Plan.

“We also advise the city on interpre-

tations of existing regulations,” Burns

said. “If these regulations do not align

with sustainability goals, we talk about

why that is and how we can change it.”

To complement the Environmental

Advisory Board, Raleigh created its first,

full-time city position in sustainability

in 2008. Dr. Paula Thomas directs the

Office of Sustainability, funded in part

by a federal block grant emphasizing

local energy efficiency.

Thomas works with each of the 21 de-

partments within the city government

to ensure their activities are energy ef-

ficient and financially sound.

“One of the first things the office did

was actually to inventory the programs

in place,” Thomas said. “We wanted to

help departments recognize the things

they were already doing.”

Both Thomas and Burns cite progres-

sive initiatives in Raleigh’s transporta-

tion sector as examples of sustainabil-

ity success stories.

“Transportation is a huge environ-

mental problem, and Raleigh has made

immense efforts to control fossil-fuel

usages in the city fleet,” Burns said.

“We now have a motor pool, made up

mostly of vehicles that run on alterna-

tive fuel.”

Thomas also highlights the tremen-

dous progress the city has made by in-

troducing electric vehicles.

“When I started talking about hybrid

vehicles as part of our fleet three years

ago, people dismissed the idea,” Thom-

as said. “Now, we’re one of the leading

cities in the nation for an electric vehi-

cle infrastructure.”

In implementing these changes, the

city recognizes that environmental poli-

cies must be approached from a practi-

cal standpoint.

“Most people will only consider these

changes if a business case can be made

for it. We have started to shift the ex-

isting paradigm by showing that some

changes that are environmentally

friendly are cheaper in the long run,”

Thomas said.

Katie Perry, a junior at UNC-Chapel Hill

from Raleigh, notes that many sustain-

able initiatives are visible to the public.

“New downtown developments were

built with energy conservation and sus-

tainability in mind,” Perry said. “In 2008,

our trash company offered each cus-

tomer a can specifically for recycling,”

he said. “I appreciated the effort be-

cause it made recycling accessible and

easy.”

Thomas feels that sustainability ini-

tiatives have improved the city overall.

“My personal opinion is that there

has been a move towards embracing

sustainability both in personal lives

and in work functions,” he said. •

SUSTAINABLERALEIGH

RACHEL MYRICK

“Nation’s Most Sustainable Mid-Size Community”

8 • WINTER MINI2011

MOLLY HRUDKA Lists of sustainable cities tend to have

repeat visitors. Curitiba, Brazil, is often

cited for its municipal park network

maintained in part by 30 lawn-trimming

sheep. Amsterdam has made a name

for itself as the city of bikes, and Copen-

hagen as the pioneer of wind power.

Malmö earned acclaim from the devel-

opment community when it unveiled

its sustainable harbor project. Portland

is far ahead of other North American cit-

ies when it comes to public transit, and

Seattle is inspiring other U.S. commu-

nities to set citywide emission-reduc-

tion goals. Reykjavik sits on a wealth

of geothermal energy, and Vancouver

leads North America in urban planning.

So why are some cities doing more

on the sustainable development front

than others? What is it that drives a city

to pursue urban sustainability? What

are the different forces driving sustain-

able urban development in European

versus North American cities? Are there

patterns that evolve in Europe we don’t

see in North America? To answer these

questions, I traveled to two environ-

mentally-progressive regions of the

world, the Pacific Northwest and Scan-

dinavia, to interview professionals in

Portland, Oregon; Vancouver, British Co-

lumbia; Malmö, Sweden; Copenhagen,

Denmark and Reykjavík, Iceland.

PortlandSince settlement of Oregon’s frontier

began in the mid 1800s, the state, par-

ticularly the Willamette Valley, has en-

joyed a thriving natural-resource econ-

omy driven by forestry and agriculture.

According to Eric Hesse, a Strategic

Planning Analyst at Portland’s public

transportation system, the city began

looking at its environmental impact de-

cades ago.

“In the 1960s Portlanders began to

realize that urban growth really pre-

sented a threat to agriculture and for-

estry,” Hesse said.

Because the state didn’t support

many industries other than those de-

pendent on natural resources, citi-

zens understood that the encroaching

sprawl had to be stopped. Alisa Kane,

the Green Building and Development

Manager at the Bureau of Planning and

Sustainability, also cited this as an im-

portant part of Portland’s unique devel-

opment.

“With its waterways, temperate cli-

mate and rich resources, people saw

early on that this was a place to pre-

serve,” Kane said.

Beginning in the late 1960s and

1970s, the people of Portland began

electing progressive leaders who prom-

ised to ease concerns about preserving

natural industry and resources.

According to Nancy Pautsch, a board

member of Portland’s Bicycle Trans-

portation Alliance, leaders like Gover-

nor Tom McCall (1967-1975) and Mayor

Neil Goldschmidt (1973-1979) had real

foresight and made the decisions that

would form the foundation for the city’s

sustainable urban development. The

SUSTAINABLE

CITIES

“When a city has established a creative,

open-minded culture, it self-reinforces.”

—Alisa Kane

WINTER MINI2011 • 9

PHO

TOS

BY M

OLL

Y H

RU

DKA

most important piece of legislature to

be passed in this era, the Oregon Sen-

ate Bill 100, was signed into law on

May 29, 1973. This piece of legislature

ushered in Portland’s invaluable urban-

growth boundary. In an effort to control

urban sprawl, it separated high-density

urban areas from traditional farmland

where limitations on non-agricultural

development are very strict.

As in many other cities, the 1990s

saw Oregon’s economy transform from

a resource-driven one to a technology-

driven one. Instead of hindering the

city’s sustainability progress, however,

the transformation continued to en-

courage it.

According to Hesse, the technology-

based economy attracts young, creative

people to the area, which further en-

courages sustainable measures.

“When a city has established a cre-

ative, open-minded culture, it self-rein-

forces,” Kane said. “The city continues

to attract those creative spirits.”

VancouverThe beginning of Vancouver’s sustain-

able urban development is nearly iden-

tical to that of Portland’s. In the 1960s

and 1970s, residents began to under-

stand the escalating threat of urban

sprawl. But unlike in Portland where

leaders took the initiative to solve the

issue, Vancouverites took the issue into

their own hands.

According to SkyTrain’s literature,

“On Track–The SkyTrain Story,” the 1960s

“saw the citizens of Vancouver oppose

the construction of urban freeways and

in so doing they had, albeit unwittingly,

set the stage for a conventional light

rail or rapid transit solution. Vancouver

is unique among North American cities

in that it has less than two kilometers

of freeway within the city limits.”

Instead, the city developed on a

grid system with heavily-used arterial

streets functioning as freeway replace-

ments.

Vancouver’s unique city arrange-

ment is what Peter Stary, the Sustain-

able Commuting Program Coordinator

for the City of Vancouver, refers to as

the “pre-existing conditions” that made

the future development of bicycle infra-

structure possible. But while high fuel

costs and a lack of freeways contrib-

uted to higher numbers of cyclists in

the 1970s, it wasn’t until the 1980s and

1990s that bicycles began to take off in

the city.

According to Stary, the city is now

“full of bike lanes and separated bike

facilities as well as bike buttons and

traffic calming in areas with bikeways.”

The result is a basic network of bike fa-

cilities around the city.

“Vancouver is probably the first city

in North America to put all of these el-

ements into a widespread network,”

Stary said.

Malcolm Shield, a Greenest City Ac-

tion Team Scholar and Climate Policy

Analyst for the City of Vancouver, em-

phasized the importance of Vancouver’s

civic pride in his work on the ‘Greenest

City 2020’ action plan.

“Vancouver has a lot of civic pride,”

Shield said. “People are proud to live

here. Take for example the riots after

the Stanley Cup Finals. Thousands of

volunteers were on the street the next

day to help clean up. It’s a very respon-

sive city, and this translates into sup-

port for our efforts.”

ReykjavikReykjavík, the capital and largest city in

Iceland, with 120,000 people, is located

on the southern shore of Faxaflói Bay

in the southwestern part of the coun-

Vancouver Community Garden— a glowing example

of Vancouver Civic Pride

10 • WINTER MINI2011

In April 2003, the world’s first

commercially-avaiable hydrogen refueling

station opened in Reykjavik.

try. The city is second to none when it

comes to drawing electricity from clean

energy sources. Geothermal energy

from underground hot springs powers

26.5 percent of electricity in Iceland.

Another 73.4 percent comes from hy-

dropower, while only 0.1 percent comes

from other sources. The city’s use of

geothermal energy presently prevents

up to four million tons of carbon di-

oxide from entering the atmosphere

each year. The use of these alternative

energy sources has helped transform

Iceland from a relatively poor country

to one that enjoys a very high standard

of living.

According to Guðrún Lilja Kristinsdót-

tir, a research assistant at Icelandic New

Energy, the drive for sustainability not

only stemmed from the presence of nat-

ural resources, but also from economic

reasons.

“When Reykjavík started using geo-

thermal heat for district heating, the

drive was mainly economic. The oil crisis

in the 1970s was an important factor,”

Kristinsdóttir said.

Because Iceland was forced to rely

on imported oil to fulfill its remaining

energy needs, leaders began to ex-

plore hydrogen as an alternative energy

source. In April 2003, the world’s first

commercially-available hydrogen re-

fueling station opened in Reykjavik. It

was just a small part of an EU-backed

plan to use Iceland to test the logistics

of implementing a hydrogen economy

in the future.

But according to Kristinsdóttir, the

hydrogen project has come with its fair

share of obstacles.

“When working with a new technol-

ogy, as we do here at Icelandic New En-

ergy, there are always some critics, and

many people are skeptical about the

first steps,” Kristinsdóttir said.

As a result, the project is several

years behind schedule and is currently

stagnating; the refueling stations in

the city lie deserted. In an article pub-

lished by the Christian Science Monitor,

Professor Bragi Arnason, the University

of Iceland chemist who first conceived

Iceland’s “hydrogen experiment,” said

that this slow progress is normal when

advocating a change in energy sources.

“If you look back in history, every

change from one type of energy to

another – wood to coal, coal to oil – it

always takes 50 years,” he said. “I will

only see the first steps, but when my

grandchildren are grown, I am sure we

will have this new economy.”

MalmöMalmö is a city of 300,000 inhabitants in

southwestern Sweden that lies across

the Øresund Sound from Copenhagen,

Denmark. Walking around Malmö, I

found several examples of sustainable

urban development. The city’s Western

Harbor was unlike anything I had seen

during my travels. Powered by 100 per-

cent local, renewable energy, it is one of

the most popular areas in the city and a

resounding economic success.

In addition to being completely car-

bon neutral, the area’s buses are pow-

ered by biogas from residents’ waste.

The neighborhood is high density and

mixed use and uses a sophisticated

rainwater collection system. The build-

ings are designed with the most high-

efficiency passive and active features;

examples including window place-

ments that maximize natural light and

solar panels respectively.

Malmö’s transition to one of the

world’s most sustainable cities be-

gan with the Swedish Shipyard crisis

in the 1980s when the city was strug-

gling with the loss of 25 percent of its

jobs. According to Malin Sarvik, the

Communication Officer at the City of

Malmö’s Environment Department, four

main components played a key role in

Malmö’s turnaround. The first? Swe-

den’s 1995 integration into the EU.

The beginning of Vancouver’s sustainable

urban development is nearly identical to that of

Portland’s.

WINTER MINI2011 • 11

All of the cities I visited were dedicated to developing and promoting sustainable projects.

“Second, Malmö University College

was established in 1998,” Sarvik said.

“It started attracting young, creative

people who shared knowledge, created

industry and started companies. This

change in populace steered the direc-

tion of Malmö’s future development.”

In 2001, the Øresund Bridge linking

Malmö to Copenhagen opened, bring-

ing back much of the industry that

had been lost in the 1980s and 1990s.

Finally, Malmö was chosen to host the

Bo01 ‘City of Tomorrow’ European Hous-

ing Exposition in the summer of 2001,

which motivated the construction of the

Western Harbor.

The first thing I observed about

Malmö, which I noticed as soon as I

walked out of Central Station, was the

overwhelming number of bicycles. Even

though its population of 300,000 is sig-

nificantly smaller than Copenhagen’s

1,199,224, Malmö’s cyclists enjoy over

400 kilometers of bicycle lanes to Co-

penhagen’s 350 kilometers. The city also

has sophisticated cycling infrastructure.

Many of the major bikeways are named

so that they can be plotted in GPS sys-

tems. The train that crosses the bridge

between Copenhagen and Malmö fea-

tures seatbelts, especially for bikes. Bi-

cycle buttons and handrails abound at

red lights and one of the most popular

bikeways has a ‘bicycle barometer’ that

counted over 1,000,000 passing cyclists

in its first six months. Government sur-

veys show that more than 80 percent of

Malmö’s citizens support campaigns to

improve the city’s bikability.

CopenhagenRenowned as one of the most livable

cities in the world, Copenhagen is also

one of the most sustainable. Much like

Malmö, Denmark’s capital is world fa-

mous for its bikability, with over 350

kilometers of bicycle routes and accom-

panying bicycle infrastructure. The city

is also known for its harbor restoration

project, sophisticated waste manage-

ment system and its groundbreaking

wind-energy industry.

According to Sustainable Cities Proj-

ect Manager and Danish Architecture

Copenhagen Harbor—Copenhagen’s Harbor Bath project is the city’s most defining development initiative.

12 • WINTER MINI2011

Center Geographer Søren Smidt-Jensen,

Copenhagen’s Harbor Bath project is

the city’s most defining development

initiative.

“In 1996, the city decided to clean

the Harbor, and by 2000 we had a

harbor that citizens could use safely,”

Smidt-Jensen said. “It involved a mas-

sive cleaning initiative and the instal-

lation of better sewage management

systems.”

Interestingly, the project wasn’t

originally intended to make the harbor

useful for recreational purposes. The

harbor initiative aimed to fulfill some

city objectives, national government re-

quirements and EU regulations. But as

a result of the restoration, the city also

had all these new recreational possi-

bilities.

“The people of Copenhagen have

been supportive of this project from

day one, long before they knew it

would benefit them for recreational

use,” Smidt-Jensen said. “They were

purely motivated by the idea of having

a clean harbor. A lot of our solutions are

very much supporting livability, walk-

ability and bikability. The key is, though,

that this has been the Danish mentality

since the 1950s.”

All the cities I visited were dedicated

to developing and promoting sustain-

able projects, Portland and Vancouver

took a different approach than the Eu-

ropean cities of Reykjavik, Malmö and

Copenhagen. North American cities

put more emphasis on their public-en-

gagement pieces than their European

counterparts, as they couldn’t always

assume their citizens would be sup-

portive of proposed projects. Citizens

in European cities, however, seemed

mostly welcoming to sustainable devel-

opment initiatives, displaying a strong

sense of collective responsibility.

According to Dr. Arun Jain, a promi-

nent urban strategist and the former

Chief Urban Designer of Portland, this

difference between European and

North American cities boils down to un-

derstanding environmental psychology

and behavior.

“Europeans don’t talk about sustain-

able watershed streets, LEEDS rated

buildings and all that stuff; they just do

it,” Jain said.

Instead of focusing on consuming

less and implementing simple sustain-

able behaviors like hanging clothes out

to dry on sunny days, residents in North

American cities tend to focus on expen-

sive, grandiose technologies like solar

panels. According to Jain, this is a case

of misguided priorities.

“It’s not sustainable to put up solar

panels when the alternative is free,” he

said.

Jain explains that the North Ameri-

can approach is a product of guilt about

what has already been done to the

planet.

“If we cared enough about living

sustainably, if it was part of our mental

DNA, then we would go about doing it,”

he said.

“There is no substitute for not con-

suming at all, and much of the conver-

sation about sustainability is in fact try-

ing to justify a way of living by making

it more efficient,” Jain said.

But this is by no means a case of ‘too

little too late.’ Portland and Vancouver

are at the forefront of a group of North

American cities that are making huge

strides toward catching up with Reyk-

javik, Copenhagen and Malmö. They are

leading the North American effort in

making a sustainable lifestyle the norm

rather than an exception. •

North American cities tend to focus on

expensive, grandiose technologies like solar

panels. According to Jain, this is a case of misguided priorities.

WINTER MINI2011 • 13

“I can’t imagine a world in which politicians are deciding what doctors are saying to me.”

The “Woman’s Right to Know Act,” re-

cently passed in North Carolina, man-

dates a 24-hour waiting period before

an abortion and requires doctors to

provide women seeking abortions with

an ultrasound and information on alter-

natives.

North Carolina Governor Bev Perdue

(D), who vetoed the law, has called the

law, “a dangerous intrusion into the

confidential relationship that exists be-

tween women and their doctors.”

Six major organizations, including

the ACLU and Planned Parenthood,

have filed suit against the new act,

which is currently undergoing judicial

review.

Around the nation, similar and even

more controversial arguments about

abortion restrictions have developed.

In Mississippi, voters recently rejected

the controversial “Personhood Amend-

ment,” proposed by their conservative

state legislature to define life as begin-

ning at conception. Critics opposed the

extreme measures of the amendment,

which would have made certain con-

traception and fertility practices in the

state possibly illegal under the new re-

strictions.

Senior Leah Josephson works at Lil-

lian’s List, a political action committee

dedicated to increasing the number of

pro-choice women in North Carolina

public office.

“I can’t imagine a world in which

politicians are deciding what doctors

are saying to me,” Josephson said. “If I

go to the doctor, I want to hear a pro-

fessional medical opinion.”

Dr. Jan Boxill, the director of the UNC

Parr Center for Ethics, thinks that the

objectives of the new law should cer-

tainly raise questions.

“Women know what’s inside of

them,” Boxill said. “What is the purpose

of making a woman listen to the heart-

beat?”

Josephson thinks that such mea-

sures are an attempt to push conser-

vative values on the public, much like

the failed Mississippi law. She worries

about the implications of conservative

efforts to limit access to abortion for

women, especially in the personhood

movements that have emerged that

could limit access to contraceptives.

“It’s hypocritical,” Josephson said.

“If you’re going to force people to go

through with unplanned pregnancies,

they should have access to birth con-

trol. I think it would be really productive

if anti-choice people spent time trying

to combat unplanned pregnancies.”

Despite the importance and rel-

evance of the debate, the lack of will-

ingness for public dialogue is some-

thing that concerns Journalism and

Mass Communication Professor Dr. Jane

Brown.

“Abortion is becoming symbolically

annihilated,” said Brown, who research-

es how the media influences adoles-

cent health. “We can’t even talk about

a legal option for women. The show

Sixteen and Pregnant shows only one

girl considering abortion. It’s not very

realistic.”

In fact, Brown thinks that by making

abortion a taboo topic, the entertain-

ment media has perpetrated a polar-

ized view of abortion.

“The media has adopted the political

dialogue on this issue,” Brown said. “It’s

EFFORTS TO RESTRICTABORTIONThe “Woman’s Right to Know Act” of North Carolina

DINESH MCCOY

become incredibly hard for people on

the pro-choice side to talk about when

life begins. And it’s hard for people on

the pro-life side to talk about the pos-

sibility of exceptions.”

At the April 2010 Lunch and Learn

event, “Why Can’t We Talk About Abor-

tion?,” Boxill highlighted the need to

establish commonalities in the abor-

tion discussion. Her four-part model for

examining one’s position on abortion

includes discussing the goal, looking

at the social reality, offering a deeper

analysis and devising strategies used

to achieve the goal.

“No one is anti-life, and no one is

completely anti-choice,” Boxill said.

“We have to be willing to look at the

seriousness of this issue. It’s not so

simple.”

14 • WINTER MINI2011

ON THE SUBJECTOF PERSONHOOD

In the wake of the failed Mississippi

personhood amendment, which would

have declared that human life begins at

fertilization, I find myself feeling legis-

latively teased—my appetite for amend-

ments has been whetted and left want-

ing.

The personhood amendment had its

appeal, no doubt. Vesting any entity

with such a particularly magnificent

“-hood” could only be a feel-good en-

deavor for everybody, right? Unfortu-

nately, there were quibbles over such

minutiae as the criminalization of cer-

tain birth control methods and of failed

attempts at in-vitro fertilization (not to

mention all forms of abortion, even in

cases of rape).

But all is not lost! I say we stick to the

personhood theme—it’s such a good

one—and merely reallocate our grand

endowment. Rather than granting per-

sonhood to the newly-fertilized, let’s

extend it to some individuals who were

not only fertilized but also went on to

be born and live deceptively human-

looking lives: namely, the homeless,

the poor, the elderly, the non-white and

the non-American.

I’m a lover of traditions myself (I may

never shake the compulsive need to

see Santa’s cookies lying half-eaten on

a plate by the fireplace on Christmas

morning at my parents’ house), but

this time-honored custom of ours—de-

humanization, that is—may be due for

reassessment.

Sure, it has made things easier, es-

pecially in the public sphere. You have

to admit, if we thought of our benefi-

ciaries as people, it would be a hell of

a lot trickier to deprive underprivileged

American children of welfare assistance

or to grant foreign aid that renders

farmers and other citizens in need de-

pendent, often for life, on profit-driven

industrial food conglomerates like

Monsanto. And it’s possible we’d lose a

bit of our gusto for armed conflict—and

thus our giddy inclination to sign off

on channeling exorbitant sums toward

such ends—if we stopped picturing our

enemies as bull’s-eye-shaped terrorism

receptacles and allowed ourselves to

see human faces standing in front of

the oil fields.

I’m sure Kansas state Rep. Virgil Peck

(R) would have hesitated to suggest—

in casual jest, of course!—that “it might

be a good idea to control illegal immi-

gration the way the feral hog popula-

tion has been controlled—with hunters

shooting from helicopters” if he saw

fewer resemblances between illegal

immigrants and pigs than between

those immigrants and his own friends

and family.

This amendment, I’ll concede, may

have some life-altering implications for

many of us. We will have to acknowl-

edge the humanity of the vagrant lying

on the park bench directly in our path,

no matter how unseemly his dress. We

will be forced to cease our categoriza-

tion of “the poor” as a migraine-induc-

ing problem with which we must deal,

somehow, and recognize the enormous

tragedy that there are people who

share all our innate human qualities

and rights living in squalor and desper-

ate need, all over the world and right

under our noses. We will have to treat

LIBBY RODENBOUGH

Rather than granting personhood to the

newly-fertilized, let’s extend it to some

invidivudals who were not only fertilized but

also went to be born and live deceptively human-

looking lives...

We will no longer be able to dismiss the plight of

suffering people simply because they do not look

or speak exactly like us.

WINTER MINI2011 • 15

the senile ramblings of an elderly rela-

tive as the words of a human being,

and a human being who has known

more of the world than most of the rest

of us at that. We will no longer be able

to dismiss the plight of suffering peo-

ple simply because they do not look or

speak or live exactly like us. In short, by

conveying personhood to these people,

we will be forced also to extend empa-

thy, if indeed we still have the capacity

for it.

Although I’m sure the concept has

seemed strikingly novel to you as you

have read the preceding words, it turns

out people have been suggesting the

extension of personhood for some

years now. Back in 1948, Woody Guth-

rie appealed to Americans to remember

the names of 28 migrant farmwork-

ers who were killed in a plane crash

while being deported from California

back to Mexico (media coverage of the

crash listed the names of the deceased

American flight crew and security guard

but referred to the others succinctly as

“deportees”). Most people today reject

the dehumanization of Jewish individu-

als and others that facilitated the Ho-

locaust and the three-fifths-of-a-person

status upon which American society

justified its enslavement of Africans and

their African-American descendents.

But dehumanization can be quite a

bit subtler than genocide or enslave-

ment as they are traditionally under-

stood. And it’s the sort of thing we all

find convenient, even necessary, to ig-

nore in our own worldviews. It would

be easy to dismiss a call to re-humanize

as a philosophical exercise, especially

at a time so fraught with immediate

practical concerns. But as long as we

are getting so worked up over the con-

tested personhood of zygotes, isn’t it

only fair that we devote some of our

energy and emotion toward the per-

sonhood of those we already generally

accept to be people? If the significance

of such distinctions seems merely

philosophical, you need not look to ex-

treme examples like Nazism but only

to consider the drastic inequity both

within America and throughout the

world to understand the implications

of dehumanization—implications that

are detrimental to humanity at large al-

though they may fatten the pockets of

a select few.

So, after concentrating on distinct

categorizations of individuals for the

bulk of this article, I’m now asking that

we amend the way we categorize, that

we begin to regard all such categories

as equal and far lesser subgroupings of

their parent designation: human. •

Personhood Now march, from Wikimedia Commons

16 • WINTER MINI2011

THE POETRY

In a packed room with nothing but

guitars, notebooks and their voices as

tools, a number of poets and perform-

ers spoke and sang Palestine to life.

The inaugural Palestine Poetry Night,

organized by UNC’s Students for Justice

in Palestine, aims to promote dialogue

about the long-standing conflict be-

tween Israel and Palestine in a unique

way.

To Ken Norman, a senior Chemistry

major and SJP’s president, the conflict in

Palestine is a human rights issue. And

as such, it demands an artistic response.

“Poetry, music and art as a means of

resisting injustice are great,” Norman

said. “You’re able to present a struggle

in a way that makes people think about

it in ways that they haven’t before.”

Suja Sawafta, a graduate student

in French and Franco-Arab Studies, first

introduced the event to a small café

in Greensboro, NC. Sawafta’s inspira-

tion came from the Gaza War of 2008,

in which Israel led a three-week inva-

sion into Gaza territory. As a Palestinian-

American, Sawafta sought some way to

express her frustration.

“Gaza was being bombarded; the

numbers of people dying were enor-

mous, and before we knew it, it was

1200 people dead,” Sawafta said. “I

thought, there’s so much more to Pales-

tine than this.”

Although initially uncertain about

the turnout she would receive, Sawafta

was encouraged by local artists’ energy.

“The main goal [was] to find a way

to show the survival of it, to see a side

that people wouldn’t normally see,” she

said. “If anything, the Palestinian ex-

perience speaks of love, and I wanted

to find a way to show that experience

without [it] being politicized.”

Since its start in 2010, SJP has worked

to change the narrative most students

receive on the conflict by planning

events to deepen their understanding.

“Our events on campus thus far have

been primarily educational in nature,”

Norman said. “The situation isn’t black

and white – it’s incredibly complex – and

that can also make it hard for people to

really understand.”

One of the group’s major obstacles,

Norman and Sawafta agree, is the rep-

resentation in American media of Israel

and Palestine, which often portrays Pal-

estinians as the sole aggressors and ne-

glects their perspective on the conflict.

“The media portrays Israel as need-

ing to defend itself at all costs,” Sawafta

said. “But the people who are oppressed

are the Palestinians—they’re the ones

who’ve been erased off the map.”

According to the Palestine Monitor,

an online magazine organized by writ-

ers, commentators and activists living in

Palestine, only 12 percent of historic Pal-

estinian land remains since the UN Par-

HAYLEY FAHEY

”Poetry, music and art as a means of resisting

injustice are great.” —Ken Norman

PALESTINEOF

WINTER MINI2011 • 17

tition Plan took effect in 1947. Norman

finds that, along with the issue of land,

many students also misunderstand the

roots of the problems between Israel

and Palestine.

“I think most people believe that the

conflict between Jews and Arabs is an

inherently religious conflict that’s exist-

ed for millennia, and that’s just not the

case,” Norman said. “Jews and Muslims

[have been] together in Palestine for

centuries without conflict. The religious

component has only been introduced

relatively recently by those wishing to

capitalize on it for their own militant

purposes.”

But alongside the conflict has

emerged new forms of creative expres-

sion. According to Sawafta, the tension

has brought a new significance to the

production of art, both as a means of

resistance to occupation and also as a

means of cultural expression.

“There’s a heritage, an artistic resis-

tance and art movement coming out of

this that people don’t know,” Sawafta

said. “Palestinian people don’t have an

army, a state—they don’t have anything.

Anything being created under that con-

dition is saying, ‘Look at us. Look at our

story.’ So the cultural production coming

out of Palestine is conveying a sense of

survival, a sense of love for the nation.”

As just one outlet within the Pales-

tine art movement, poetry speaks of

the troubling conditions that Palestin-

ians face daily as a result of the border

conflict. For many Americans, however,

these conditions are simply not recog-

nized.

“It’s important for people to realize

that there is another side of the con-

flict,” Norman said. “The Palestinians are

suffering under a military occupation

that permeates every aspect of their

lives, prevents them from traveling free-

ly even within their own territory. There

is a human side that people often only

see as a result of violence on the Pales-

tinian side, but rarely as a result of the

impact of Israel’s military occupation.”

For Sawafta, poetry has been one

way of revealing the human side of

the Palestinian experience—the side

that goes beyond politics and into the

actual lives of Palestinians. Inspired by

the work of Palestinian poet Mahmoud

Darwish, Sawafta locates the power of

poetry in the nostalgia that it evokes,

connecting the artist to his or her home.

“There’s a feeling you get when you

think about the colors of where you’re

from, when you’re reading poetry,” she

said. “And it’s something [the Def Poet]

Mark Gonzales calls ‘genetic memory.’”

This genetic memory, or connection

with one’s homeland, has been the pri-

mary inspiration for Sawafta’s own po-

ems about Palestine.

“While I was living in France, I was

questioning my place there, thinking

about how every time I drank chamo-

mile tea, I thought of Palestine, how the

sage in my tea tasted like Palestine,”

Sawafta said. “I wanted my poem to

convey this sense of a Palestinian nest

without the blood, bones, and num-

bers—the real tie that Palestinians have

to the land.”

In 1948, David Ben Gurion, Israel’s

first Prime Minister, made a prediction

about the fate of Palestine that many

still cite today: “The old will die,” he

said, “and the young will forget.” But

for artists like Sawafta dedicated to pre-

serving the voice of Palestine, this pre-

diction has not, and will never, become

truth.

“The Palestinian people are so

proud, but the way the Second Intifada

changed the way of life there, you have

very defeated and pessimistic people,”

Sawafta said. “But no matter what they

[Israeli occupiers] do to impose restric-

tions, there’s always going to be this

sense of a movement, because there’s

this sense of connection to the land.” •

The genetic memory...has been the primary inspiration for Sawafta’s own

poems about Palestine.

LAMPEDUSA

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

The author spent two weeks in Lampe-

dusa in July, as part of a summer re-

search project on the refugees of the

Arab Spring. She interviewed migrants,

activists, humanitarian workers and

locals to understand the experiences

of those affected by the transnational

movement caused by the revolutions in

North Africa.

Between February and March 2011, an

estimated 35,000 migrants left from Lib-

yan and Tunisian ports and crossed the

Mediterranean to reach Europe. Their

first stop: Lampedusa, a 20-square km

path of Italian sand with a population

of 6,000 people, situated just 100 km

from the North African coast. (photo 1)

Some, in quest of better lives away

from the economic uncertainties of

the Arab Spring, paid a smuggler up to

2,000 euros for their perilous journey.

Others, mainly sub-Saharan and Ban-

gladeshi labor workers of Libya, were

thrown into boats by Gaddafi’s army.

With this bold move, the late dicta-

tor hoped to upset the Italians whose

NATO bases helped the advancement

of Libyan rebel troops. (photo 2)

Beyond the risks of dehydration, the

most dangerous obstacle for the mi-

grants to overcome was the sea. “Our

boat was four meters long and had a

small engine,” Jaafar, a Tunisian refugee

who arrived last February, said. A month

earlier, he failed his first attempt at

crossing when his boat capsized and he

was brought back to the Zarzis shore.

(photo 3)

Commandante Morana, who oversees

the port operations, leads rescue mis-

sions when boats are in distress. He

recounts this vivid memory where an

overcrowded boat containing 150 peo-

ple threatened to capsize in the middle

of sea. “The conditions were rough but

my men managed to save 53 lives,” he

said. “I remember the eyes and faces of

my team at that time: they would have

liked to save more.” (photo 4)

Those who reached Lampedusa did not

always receive the warmest welcome.

“In March, they waited on the harbour’s

deck to prevent the migrants from

landing,” Georges Alexandre, a French

activist who arrived in Lampedusa in

November last year, said. George Alex-

andre started his own NGO, “Kayak per

il diritto alla vitta.” He kayaked from Tu-

nisia to Malta and Lampedusa to raise

awareness about what he believes to

be the European Union’s failed immi-

gration policies.

Some islanders interviewed felt that

the migrants’ story – which attracted

prominent media such as Al-Jazeera

and the BBC – failed to present their

stories. Locals said they lost more than

half of the revenue usually gained from

the high touristic season because the

early coverage showed 8,000 Tunisians

free on the island. (photo 5)

On April 4, after three months of freez-

ing under makeshift tarps and being

fed pasta that, according to Alexandre

was suspected to have been infused

with tranquilizers, former Prime Minis-

ter Berlusconi emptied the island and

relocated the excess migrants to other

parts of Italy. (photo 6)

Lampedusa’s “retention” center none-

theless detained 2,000 people, more

than twice its capacity. Detention can

span anywhere from a few weeks to 18

months, during which the government

decides whether to grant migrants

asylum, refugee statuses or seasonal

working permits depending on each

individual’s circumstance. Some end up

being deported to their country of ori-

gin. Georges Alexandre knew of desper-

ate men who swallowed razor blades

in the hope that a trip to the hospital

would spare them the long stay in the

detention center.

Lampedusa may be a transit point in

Europe, but remains a major stop in the

migrants’ lives. (photo 7)

THE GHOSTSat the DOOR OF EUROPE

AUDERY ANN LAVALLEE

20 • WINTER MINI2011

TOWARD GREATER AWARENESS

When sculptor Mitch Lewis began re-

searching African totems, he never

imagined his project would turn into an

in-depth look at the horrific genocide

occurring in Darfur. Much of Lewis’ past

work has focused on studying the hu-

man condition, but Lewis says it was

his Jewish heritage that drew him to

creating an exhibit focused on Darfur.

“After the Nazi Holocaust [the world

said] ‘never again’ and to me that

meant…all of humanity,” Lewis said.

Lewis was shocked at how few peo-

ple were aware of the genocide occur-

ring in Darfur.

“I decided to try to raise awareness

about it and the best way for me to do

that was through my sculpture; that

was how I could reach the most peo-

ple,” Lewis said.

The exhibit “Toward Greater Aware-

ness” is made up of a series of fig-

ures crafted from terracotta, high-fired

stoneware, resin and metals and seeks

to “address the physical and psycholog-

ical scars left on mankind by a culture

of violence and brutality,” according to

Lewis’ artist statement.

The pieces focus primarily on women

and children and how they are affected

by the conflict. Lewis touches on the

tragedy of child soldiers and the use of

rape as a weapon of war.

“Women are targeted. When [the

Janjaweed] invade a village…there are

men whose particular assignment is

raping women,” Lewis said.

The assault is intended to trauma-

tize the woman and shame their fami-

lies. Those children too young to be

forced to participate in the conflict as

child soldiers are burned in trashcans

by the Janjaweed, the roaming militias

supported by the government of Sudan

who attack villages suspected of sym-

pathizing with rebel groups such as the

Justice and Equality Movement.

Those displaced by the conflict are

left to fend for themselves in refugee

camps in Darfur and Chad, where mal-

nutrition and violence, especially gen-

der-based, are widespread. The govern-

ment’s tacit support for the genocide

perpetrated by the Janjaweed in Darfur

has led to the International Criminal

Court charging Sudan’s President Bashir

with crimes against humanity in 2009.

Despite a 2006 peace agreement

between the government of Sudan and

the Sudanese Liberation Army, violence

in the region has continued, peaking in

2010.

Lewis’ work on Darfur has resulted in

a partnership with “United to End Geno-

cide” an organization that seeks “a

peaceful resolution to the crisis in Dar-

fur and to prevent and stop large-scale

violence against civilians throughout

North and South Sudan,” according to

endgenocide.org.

“Art can reach people on such an

emotional level and can have a pro-

found impact…I see that as my role to

try to reach those people,” Lewis said.

He hopes his exhibit will serve as a

call to action, especially among univer-

sity students.

“After you see this exhibit you can

never again hide behind the veil of ig-

norance. Now you’ve seen it, now you

know about it and now you must act,”

Lewis said. “Collectively, if we all make

our voices heard, something might get

done.” •

KYLE SEBASTION

“Art can reach people on such an emotional

level and can have a profound impact.”

Preventing Violence through Sudanese Art

pho

tos

by s

tefa

nie s

ch

wem

lein

WINTER MINI2011 • 21

Published with support from:

Campus Progress, a division of the Center for American Progress.

Campus Progress works to help young people — advocates, activists,

journalists, artists — make their voices heard on issues that matter.

Learn more at CampusProgress.org

Also paid for in part by student fees.

Campus BluePrint is a non-partisan student publication that aims to provide a forum for open

dialogue on progressive ideals at UNC-Chapel Hill and in the greater community.