Winning china's apparel market (1)

-

Upload

muhammad-omer-mirza -

Category

Lifestyle

-

view

186 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Winning china's apparel market (1)

1Winning China’s Apparel Market

Winning China’s Apparel MarketChina’s apparel industry is growing rapidly— accompanied by some major challenges. While there is no one-size-fits-all strategy for success, finding the right fit will be vital.

2Winning China’s Apparel Market

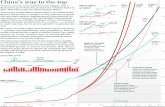

Even in the face of an expected economic slowdown, the growth of China’s apparel industry— an estimated 14 percent—is likely to outpace the nation’s projected 7-8 percent growth in gross domestic product. The population’s ongoing migration to urban centers and its increased levels of disposable income are major forces driving growth in all apparel categories (see figure 1). A closer look reveals more details about the development of these categories over the years.

Sportswear: maturing. The early entry of global giants such as Nike dates back to the early 1980s, and spurred three decades of tremendous growth. Today the industry has emerged from its adolescence and reached early maturity. The sportswear market has grown to about $11 billion, with five players capturing about half the market. By 2011, Li-Ning, the eponymous leading domestic company founded by China’s former Olympic gymnastics gold medalist, had more than 8,000 sales outlets, leaving limited potential for opening more new stores. (That same year the company experienced its first top-line shrink since its 2004 initial public offering.) Recently, overstocks of obsolete inventory have troubled some leading companies, especially local ones, as competition gets stiffer. The trend today is for companies to grow by optimizing existing stores’ performance rather than by opening new stores.

Casual wear: scaling. The 1990s brought more personal freedoms to China, and that was reflected by middle-aged Chinese abandoning their work uniforms in favor of formal wear. Today’s consumers spend more on casual wear as they embrace a more liberal lifestyle and enjoy a wider range of brands and styles from which to choose. Within the category, fashionable casual wear accounts for two-thirds of the casual-wear market and is projected to grow at a 15 percent annual rate over the next three to five years. The smaller business casual-wear subcategory is likely to experience even higher growth—about 20 percent annually—thanks to a larger customer base and wider range of choices.

Estimated market size (2012, $ billion)

Growth forecast(CAGR 2012-2016)

Developmentstage

Stagecharacteristics

Apparel category

Men’s formal wear

Sportswear

19 ~8%-10%

11 ~10%

Maturing

Note: Sportswear excludes footwear and accessories; outdoor excludes footwear and equipment.

Sources: Company annual reports, Euromonitor; A.T. Kearney analysis

Figure 1 Stages of development for select major apparel categories

• Growth slowdown • Intense competition• Price wars• Industry consolidation

Women’s casual wear

Men’scasual wear

67 ~15%

56 ~17%

Scaling up • Rapid growth• Fragmented market,

increased competition• New store openings

(leaders grab market share)

Baby wear(0-5 years)

Outdoor

5 ~20%-25%

1 ~20%-30%

Opening • Low penetration (but increasing fast)

• Limited competition

3Winning China’s Apparel Market

The women’s casual-wear category is more developed and competitive than men’s casual wear. Entry barriers are lower than those for sportswear, due in part to the smaller marketing investment required up front—in other words, expensive endorsements and sponsorships aren’t needed to impress casual-wear consumers. Metersbonwe, a leading domestic casual-wear player that opened its first specialty outlet in 1995, now operates more than 4,500 stores to sell its two brands. However, brand life cycles for casual wear are shorter than for sportswear, and success is achievable within a relatively short period of time. For example, GXG, a domestic menswear brand launched in 2007, already ranks among the top-selling brands in many shopping malls.

Baby wear: scaling. As urbanization continues and the one-child policy loosens up, China’s urban baby population, defined as children up to five years, is expected to grow at a steady 2.1 percent annually. Together with expanding middle-class income levels and household size, this growth is driving baby-wear market growth at a 20 percent annual rate.

The trend today is for companies to grow by optimizing existing stores’ performance rather than by opening new stores.The baby-wear category is extremely fragmented, with the top five companies sharing just 7 percent of the market. Competition, obviously, is fierce. A few international players, including Gap, Zara, H&M, Uniqlo, and even luxury brands such as Armani and Burberry, have joined the many domestic brands that compete mainly in the middle and low-end segment, where a piece of winter outwear sells for less than $100. There’s also a large group of non-branded competitors that garners a 30 to 40 percent market share. The children’s-wear market, targeting children up to 13 years old, is also experiencing excellent growth, with forecasts of about 20 percent annually over the next three to five years. The network size of companies differs significantly, depending on segment coverage and price positioning. For example, Balabala, the largest baby-wear and children’s-wear player, has about 3,000 retail outlets, while Yeehoo, another leading baby-wear player, has more than 650 stores.

Outdoor: opening. China’s outdoor-wear market is in its infancy, with only about 5 percent of the population engaging in outdoor sports (compared to 50 percent in the United States). But the popularity of outdoor sports is growing steadily, and consumers also buy outdoor apparel for everyday use, favoring their comfort and functionality. Demand, then, is up, and companies are stepping up their efforts to meet that demand. In 2007, there were 377 outdoor- wear brands in China—that number doubled by 2011. Most of the new players have limited market shares, while five brands have cornered about half the market. Over the past decade international brands such as The North Face, Columbia, Jack Wolfskin, and Northland have been competing in similar price ranges with Chinese brands that include Ozark and Toread. All leading players are actively expanding their sales network—Toread had about 1,200 stores in 2012, while Columbia’s numbered about 600. The network size is still small for the vast China market.

4Winning China’s Apparel Market

Despite the differences in stages of development, competition is heating up in every apparel category. Many leading players have announced ambitious expansion plans:

• Nike aims to double its sales in China by 2015

• Among its global business regions H&M expects to realize its highest growth rate of expansion in China

• The North Face is expanding its retail outlets from its current 500 stores to 1,000 by 2015

The ChallengesA study undertaken by the Chinese Apparel Association shows that from 2000 to 2005 the average life cycle of the top 500 domestic brands in China was just 1.5 years. This is a result of fierce market competition combined with consumers’ fast-changing tastes. Companies adopt different growth models, reacting to different generations’ varying tastes in apparel, especially casual wear. For example, people born in China in the 1980s enjoy more disposable income than those only 10 years older, and had wider choices in their childhood and teen years as China’s economy opened up. Meanwhile, the highly individualistic post-1990 generation is even more aggressive in pursuing stylish dress.

The battle will be fierce when income levels and brand awareness in smaller cities catch up with those in megacities.The moral of the story is this: As time goes by, loyal consumers can outgrow a brand’s target age ranges and forsake it in favor of new entrants, especially fashionable international brands, that offer identities and styles. To meet this challenge and capture growth opportunities, companies often launch multiple brands to cover different age groups and designs. It is important to carefully plan and execute investments to build new brands and realize synergies in manage- ment resources, brand awareness, cross-selling potentials, supply chains, and negotiations with landlords.

Top players in more-developed categories have established large sales networks. For example, Anta’s 8,000-store network reaches into tier 3 and 4 cities. Other leading sportswear players, such as Nike, have more than 6,000 stores, top casual-wear players Metersbonwe and Semir have more than 4,500 outlets each, and Only and Vera Moda can be found in nearly every shopping mall in China. Once the saturation point is reached, expanding the retail network to grow sales is no longer effective; moreover, rapid network expansion, if not managed properly, can result in both a fragmented, hard-to-control distributor base and—when eagerness for growth exceeds customers’ willingness to spend—inventory problems. For example, the failure of some large sportswear companies to balance aggressive growth plans with their stores’ ability to sell has led to channels overstocked with hard-to-sell off-season products. As China’s macroeconomy slowed, many apparel companies suffered sales decline in 2012, making overstocking a prevalent issue in multiple categories. Unless the lessons of the recent past are absorbed, history is likely to repeat itself.

5Winning China’s Apparel Market

Boosting Brand VisibilityIt is never easy to spread a brand’s presence across a national market, let alone one as heteroge-neous as China’s where disparity of spending power and brand awareness persists. Nevertheless, multinationals are trying to penetrate tier 3 and 4 cities, where local players compete at lower price points (see figure 2). Adidas and H&M, for example, have announced plans to increase their presence in lower-tier cities by 2015. At the same time, several domestic brands are striving to reposition themselves at higher price points to attract consumers in tier 1 and 2 cities. In 2010, Li-Ning planned to open upgraded flagship stores in tier 1 cities, part of a series of repositioning moves to compete with international brands. The battle will be fierce when income levels and brand awareness in smaller cities catch up with those in megacities.

In megacities, higher rental and labor costs are squeezing retailers’ margins and making it more difficult for low-performing brands to survive. Penetrating lower-tier cities brings with it other challenges, of which the most obvious is site selection (see figure 3 on page 6). There are often fewer well-developed high-end commercial areas offering desirable retail formats and a good mix of brands in tier 3 and 4 cities. Leading brands often leverage their ability to attract customers as a bargaining chip to secure good locations with favorable lease terms.

In the era of the Internet, of course, e-commerce is an alternative means of reaching rural areas and smaller cities, not to mention savvy consumers seeking bargains—a natural for clearance sales. Companies that launch online sites need to determine a supply-chain setup for covering target geographic areas and meeting customers’ service and cost needs to mitigate negative impact on sales at brick-and-mortar stores.

Finally, the rapidly expanding fast-fashion segment has not only piqued consumer interest in affordable, edgily fashionable clothes but is also challenging the way mass-brand players

Strengths

Local players Multinationals

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis

Figure 2Apparel players battle for market position across cities

• Deep knowledge of local market• Strong local government support • Long-time relationships with local distributors• Ideal site locations• Flexible, able to adapt quickly

• International brands • Management expertise• Deep pockets and access

to capital• Professional management

processes and systems

Weaknesses • Less depth of management capabilities• Very little strategic branding experience• Growth restricted to home market• Limited access to capital

• Scarce local market and consumer insights

• Weak government and local market connections

• Limited presence in tier 3 and 4 cities

DefendDominated by local players

Dominated bymultinationalsPenetrate

Tier 3 and 4 cities Tier 1 and 2 cities

6Winning China’s Apparel Market

do business. Giant fast-fashion retailers Zara and H&M have entered first-tier cities and are looking to grow quickly. Zara is well on its way to doubling its 2012 roster of more than 120 stores, with most of the new ones to be located in cities other than Beijing and Shanghai. The company also plans to launch an online retail channel.

A well-controlled self-owned supply chain and retail channel help Zara keep time-to-market to as short as two weeks. The retailer’s marketing strategy stresses in-store experience, and consumers visit Zara stores more often than they do traditional mass-brand outlets. Some leading domestic companies are trying to copy the Zara model. Metersbonwe, for example, operates on a Zara-esque philosophy of quality fashion at an attractive price. It employs a combination of trade-fair (70 percent) and current-season ordering (30 percent) to ensure fast response to the latest sales trends. Similar to Zara, Metersbonwe maximizes its supply-chain efficiency by investing heavily in logistics and information technology.

So far, however, most players’ attempts to imitate Zara have fallen short, mostly due to below-runway-standard fashion products and sales that are too low to support large, trendy stores in prime locations and a powerful supply chain. Some domestic companies are attempting to switch to a pull operating model, increasing their number of annual trade fairs to follow trends more closely. Others are increasing their percentage of same-season replenishment or even same-season designs, requiring more robust supply chains to reduce inventory risks.

Challenges

Sources: Local government statistics bureaus; A.T. Kearney analysis

Figure 3Site selection in lower-tier cities presents challenges

Sites• Limited core

commercial areas • New areas far from

city centers• Shabby secondary

streets with little tra�ic

• Changing hot spots

Formats• Limited openings

along main street• Tend toward small• Odd-shaped

Developers• Unethical behaviors • Misaligned profit

incentives• Bundled deals with

unproven locations• Unfamiliar with

retail requirements• Limited brand

recognition

Changxing, Zhejiang ProvinceUrban disposable income per capita($, 2010)

• Several large shopping centers• Mostly small storefronts• New areas with minimal traic

5,956

4,829

4,186

3,703

2,898

2,576

~1,500

Shenzhen (Tier 1)

Hangzhou (Tier 2)

Xi’an (Tier 2)

Chengdu (Tier 2)

Kaifeng (Tier 3)

Changxing (Tier 4)

Core,mature,high density

Secondary streets or centers

Newareas, quieter

7Winning China’s Apparel Market

Dressed for SuccessAs consumer preferences change, the shrewdest companies carefully review their product design and positioning, then reposition their brands—or launch new ones—to:

• Attract next-generation consumers

• Address brand life-cycle issue

• Cover different segments to enlarge customer base

• Increase growth potential

• Minimize risk

Esprit offers an excellent example of successful repositioning. Realizing loyal customers were beginning to associate its brand more with purposeful dressing and less with fashionable, Esprit repositioned itself back to its heritage of offering more self-expressive elements. New brand campaigns, a dedicated design hub in China, and changes at the executive level, including a new head of product and design and a new China chief executive officer, support the turnaround plan.

Backed by data-analysis tools, a multiple-store network can share stock and adjust in-season merchandising to meet local market needs.Conversely, Li-Ning’s repositioning has been less than successful. In an attempt to make its brand more appealing to the post-1990s generation of consumers the company changed its logo and slogan, a move that analysts say alienated many loyal customers.

While many companies choose to reposition existing brands, others launch new ones. Ochirly, a leading women’s casual-wear company, launched Five Plus to target younger consumers that eschew the more mature Ochirly brand. Adidas has introduced its NEO line, targeting teenagers with casual products more affordable than the flagship brand. Anta, a leading local sportswear company, has acquired FILA to capture first-tier consumers and, in the process, learn how to operate a leading international brand.

So we see that there are three keys to launching a new brand successfully:

1. Finding new customer segments that have synergy with an existing brand

2. Determining the right positioning in those segments, including product characteristics that are differentiated from the mass market and that target customers will welcome

3. Assembling an experienced, knowledgeable management team

Where to invest the always important marketing dollar is another crucial factor. Leading players often use celebrity endorsement and mass-media marketing to strengthen brand awareness and create attractions. Typical marketing expenses range from 1 percent to 5 percent of sales. Some international retailers, such as Zara, seek to impress consumers with best-in-class

8Winning China’s Apparel Market

shopping experience in the best locations. Zara invests heavily in store design and decoration, and carefully manages in-store merchandising, such as displaying men’s, women’s, and children’s clothes in the same store, a trend being copied by shopping malls and mass-brand players. Many brands have also started marketing themselves on social media and other online platforms.

Diversified channels help not only to capture sales but to ease inventory pressures. Backed by data-analysis tools, a multiple-store network can share stock and adjust in-season merchan-dising to meet local market needs. Suburban outlets and online channels selling off-season products at discounted prices are helpful for clearing obsolete inventory. Given their mush- rooming popularity and low cost, online channels are particularly promising for inventory cleanup—online sales account for as much as 10 percent of sales for some leading casual-wear brands. It is important to note that careful site selection of factory outlets and a clear merchandising strategy for various channels are crucial for avoiding cannibalization.

Finding the Perfect FitDepending on a brand’s development stage and local context, companies need to select the right country model and the right mix of store ownership and operating mode (see figure 4). The chief-agent model is typically employed by leading international brands entering a local market with which they’re unfamiliar. As business grows, companies typically will take over to increase control and improve performance. At the store level, companies choose different levels of equity ownership in their distributor base for various strategic reasons, and the models can evolve as business grows and the competitive landscape changes. A typical strategy is to rely on distributors initially, then gradually increase the percentage of self-owned stores by replacing low-performing distributors, especially in core markets.

Distributors and franchisee

Agent Joint venture

Subsidiaryonly

Low HighEquity stake in distribution

Distributor management model

Implications

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis

Figure 4Distribution model implications for stakeholders

• Typical industry practice

• Able to balance retail management and distribution channel expansion

• Advance product purchase unnecessary

• Commission-based sales

• Distributor’s local knowledge valuable (for example, secure store location)

• More control of distribution

• Brand companies have flexibility to tackle inventory issues

• Stronger retail performance

• Large investments• Preferred strategy

of global brands and fast fashion retailers

Brand

Self-

owne

d

Dis

trib

utor

Brand

Self-

owne

d st

ore

Age

nt

Nor

mal

fr

anch

isee

Brand Brand

Subs

idia

ry

Join

t ven

ture

Dis

trib

utor

Subsidiary

Self-ownedstore

9Winning China’s Apparel Market

To smooth transitions, some companies form joint ventures, sign franchise agreements with phasing-out terms, or hire agents in remote markets. Bestseller, which owns women’s casual-wear brands Only and Vero Moda, leveraged its distributor base early on to expand rapidly and increase awareness and market share. It eventually phased out distributors and took back the retail network on its own to gain more control and maximize financial returns.

In addition to equity links, brand companies use various tools to guide operations of distributor-owned stores. Leading players have installed unified IT systems at almost all retail outlets to ensure sales and inventory transparency. These companies analyze transaction and inventory data to facilitate stock-pooling and help decide on the next season’s designs and discounts.

We’re also seeing another trend in China’s apparel industry. Traditionally, brands have allowed distributors and subsidiaries to order whatever they expect to be best-selling items. Leading brands have started to provide guidance in ordering, such as bundling stock-keeping units to build consistency in different outlets by displaying a complete set of merchandising, a move that also eases supply-chain planning pressures.

Truth be told, there is no one-size-fits-all strategy for success in China’s apparel market. Its unprecedented growth over recent years is expected to double over the next decade, but of course that doesn’t guarantee that every player will succeed. Established and aspiring players that rethink their strategy, and perhaps reinvent their brands, will be best placed to win a share of China’s burgeoning apparel market.

Authors

Sherri He, partner, Shanghai [email protected]

Jason Li, consultant, Shanghai [email protected]

Grace Ling, consultant, Shanghai [email protected]

A.T. Kearney is a global team of forward-thinking partners that delivers immediate impact and growing advantage for its clients. We are passionate problem solvers who excel in collaborating across borders to co-create and realize elegantly simple, practical, and sustainable results. Since 1926, we have been trusted advisors on the most mission-critical issues to the world’s leading organizations across all major industries and service sectors. A.T. Kearney has 59 offices located in major business centers across 39 countries.

Americas

Europe

Asia Pacific

Middle East and Africa

AtlantaCalgary ChicagoDallas

DetroitHoustonMexico CityNew York

San FranciscoSão PauloTorontoWashington, D.C.

BangkokBeijingHong KongJakartaKuala Lumpur

MelbourneMumbaiNew DelhiSeoulShanghai

SingaporeSydneyTokyo

AmsterdamBerlinBrusselsBucharestBudapestCopenhagenDüsseldorfFrankfurtHelsinki

IstanbulKievLisbonLjubljanaLondonMadridMilanMoscowMunich

OsloParisPragueRomeStockholmStuttgartViennaWarsawZurich

Abu DhabiDubai

JohannesburgManama

Riyadh

A.T. Kearney Korea LLC is a separate and independent legal entity operating under the A.T. Kearney name in Korea.

© 2013, A.T. Kearney, Inc. All rights reserved.

The signature of our namesake and founder, Andrew Thomas Kearney, on the cover of this document represents our pledge to live the values he instilled in our firm and uphold his commitment to ensuring “essential rightness” in all that we do.

For more information, permission to reprint or translate this work, and all other correspondence, please email: [email protected].