WILLAERT - CHANSONS, MADRIGALI, VILLANELLE

-

Upload

outhere-music -

Category

Documents

-

view

253 -

download

9

description

Transcript of WILLAERT - CHANSONS, MADRIGALI, VILLANELLE

Recorded in June 1994, église Saint-Apollinaire à Bolland

Artistic direction, recording & editing: Jérôme Lejeune

Cover: Gertit van Honthorst, Musical company (1629)

Leipzig, Museum der Bidenten Künste

Photo: © akg-images, Paris

ADRIAEN WILLAERTc. 14901562CHANSONS, MADRIGALI, VILLANELLE—ROMANESQUEKatelijne Van Laethem: sopranoHannelore Devaere: harpSophie Watillon: treble and bass viol, viola bastardaPiet Strykers: bass viol, percussionsFrank Liégeois: bass viol, citternBart Coen: recordersPhilippe Malfeyt: lute, bass lute, chitarrone, percussions

Philippe Malfeyt: conductor

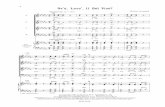

1. Qual dolcezza giamai Adriaen Willaert 4'28 Soprano, 3 viols, bass lute, harp, recorder

2. Zoia zentil Adriaen Willaert 1'48 Soprano, 2 viols, recorder, lute, harp

3. Dessus le marché d'Arras Adriaen Willaert 1'07 Soprano, lute, harp, viol

4. Dessus le marché d'Arras Pierre Attaingnant 1'20 Recorder, 3 viols

5. Allons, allons gay Adriaen Willaert 2'52 Soprano, 2 viols, lute, harp, cittern 6. Canzon Allez mi faut di Adriano Giovanni Antonio Terzi 4'52 Lute, harp

7. Quante volte diss'io Adriaen Willaert 3'14 Soprano, 3 viols, lute

8. Vecchie letrose, non valete niente Adriaen Willaert 1'39 Soprano, 3 viols, lute, harp, percussions

9. Chi la dira Adriaen Willaert 2'12 Soprano, recorder, 3 viols

10. Chi la dira disminuita Antonio Valente 2'39 Lute, harp

11. Tiento IV sobre Qui la dira Antonio de Cabezon 2'33 Recorder, 3 viols

12. E se per gelosia Adriaen Willaert 1'40 Soprano, 3 viols, harp, lute, recorder

13. Un giorno mi pregò Adriaen Willaert 1'52 Soprano, 3 viols, lute

14. A la fontana Giovanni Bassano 4'55 Recorder, harp, chitarrone

15. Cingari simo Adriaen Willaert 2'12 Soprano, recorder, 3 viols, harp, percussion

16. O quando a quando havea Adriaen Willaert / 5'25 Soprano, lute, harp, 3 viols Giulio Aabondante 17. Joyssance vous donneray Adriaen Willaert 2'34 Soprano, recorder, 3 viols

18. Joyssance Vincenzo Bonizzi 5'23 Viola bastarda, chitarrone

19. Arousez vo violette Adriaen Willaert 1'24 Soprano, 3 viols, lute

20. O bene mio famm'uno favore Adriaen Willaert / 2'34 Soprano, lute Diego Pisador21. Ricercar X Adriaen Willaert 3'40 Recorder, 3 viols

22. Occhio non fu gamai Adriaen Willaert 2'40 Soprano, harp

23. Sempre mi ride sta Adriaen Willaert 2'15 Soprano, recorder, 2 viols, cittern, lute, harp

ADRIAEN WILLAERT

—

Le fl amand Adriaen Willaert (ca. 1490-1562) est bien le compositeur qui, vers le milieu du XVIe siècle, domina la vie musicale en Italie. Il naquit probablement à Roeselare, mais durant sa jeunesse des liens solides l'unissaient à la ville de Bruges. Après des études auprès de Jean Mouton à Paris, il entra vers 1515 au service de la famille d'Este à Ferrare. C'est grâce à cette cour, l'une des plus fl orissantes de la Renaissance, qu'il entra en contact avec la cour papale à Rome. En 1527, il fut nommé maître de chapelle à Saint-Marc de Venise, fonction qu'il conserverait jusqu'à sa mort. Bien que le pouvoir économique de cette riche ville marchande fût en déclin, son rayonnement culturel se propageait à toute l'Europe. La ville n'épargnait aucun eff ort pour avoir toujours à son service les meilleurs chanteurs et instrumentistes, ce qui faisait d'elle un bouillon de culture d'innovation et de talents musicaux. La place de maître de chapelle de Saint-Marc était alors considéré comme étant un poste important pour la vie musicale européenne.

La réputation de Willaert était telle que de nombreux jeunes compositeurs affl uaient dans la ville des Doges pour prendre des leçons avec « Messer Adriaeno » ; c'est ainsi que Willaert infl uença toute une génération de musiciens. Parmi ses élèves, citons Andrea Gabrieli, Cipriano de Rore, Jacob Buus, Constanzo Porta, Nicola Vicentino ainsi que le théoricien Gioseff o Zarlino.

Adriaen Willaert était un compositeur éclectique. En ce qui concerne la musique d'église, il contribua au développement du motet et encouragea la naissance de la musique polychorale avec ses psaumes à doubles choeurs. Mais il s'intéressait également à la musique profane. Il composa des chansons françaises, non seulement durant son séjour parisien, mais également en Italie où la musique française était à la mode, entre autres chez le pape Léon X ainsi qu'à

la cour d'Ercole II d'Este, qui avait épousé Renée de France. Ses premières chansons étaient encore infl uencées par Josquin et Mouton : par exemple, le malicieux Dessus le marché d'Arras, avec la typique alternance entre les voix de dessus et de grave, ainsi que Allons, allons gay à trois voix. Les chansons extraites des derniers recueils, entre autres Jouyssance vous donneray et Qui la dira la peine de mon cœur, se distinguent par une ligne mélodique plus fl uide, une plus ample sonorité et un style imitatif riche, apparenté au motet. On ne connaît pas avec certitude le compositeur du petit air à double sens Arousez vo violette, mais certaines sources l'attribuent à Willaert.

Celui-ci se distingua également comme compositeur de madrigaux, mais pas tant que Verdelot et Arcadelt qui étaient les spécialistes du genre. Parmi ses premières œuvres Quante volte diss'io à quatre voix trahit la prédilection qu'avait Willaert pour le poète Pétrarque. Il amorça une nouvelle évolution dans l'art du madrigal avec Qual dolcezza giamai, qu'il dédia à la chanteuse Polissena Pecorina ; l'écriture est ici à cinq voix et le style polyphonique est fortement apparenté au motet. Par rapport au madrigal, plutôt sérieux et sophistiqué dans l'expression poétique et musicale, la villanesca alla napolitana est beaucoup plus légère et simple.

Cette forme devient à la mode vers 1530 et, en 1544-14445 Willaert en fi t publier un recueil. Les textes décrivent de petites scènes populaires tirées de la vie quotidienne : un amoureux se moquant de vieilles femmes (Vecchie letrose), une dame ridiculisant publiquement un ancien soupirant (Sempre mi ride sta), un jeune homme chantant une sérénade pour obtenir un rendez-vous avec son aimée (O bene mio). Cingari simo est un mascherata alla napolitana qui décrit des individus masqués, travestis en bohémiens libérant quelques vaches et ceci avec des jeux de mots à double sens. Dans cette pièce, Willaert s'inspire de la voix de soprano d'une version à trois voix de Giovanni da Nola, mais en la transcrivant pour la voix de ténor. Les versions pour voix solo et luth de O quando a quando havea et O bene mio furent transcrites en tablatures par le virtuose espagnol Diego Pisador dans son Libro de musica de vihuela (1552). Un giorno mi pregò est une villotta, une variante des villanelles du nord de l'Italie. Celles-ci sont,

en fait, des airs de danse utilisés lors des représentations de pantomimes. Zoia zentil et Occhio non fu giamai appartiennent à un genre sérieux : ce sont des canzones écrites par le poète Angelo Beolco, surnommé « Il Ruzzante ». La chanson E se per gelosia se singularise par le côté mordant du texte. Celle-ci parut en 1541 dans un recueil de bicinia, pièces à deux voix qui étaient volontiers utilisées pour l'enseignement de la musique.

Adriaen Willaert écrivit également de la musique instrumentale. Il publia en 1540, avec son collègue Julio da Modena ainsi que quelques élèves, le recueil Musica Nova, une collection de ricercare, pièces instrumentales polyphoniques dans un style de motet. Ce sont les premières œuvres du genre à être publiées. Exemple rapidement suivi par d’autres compositeurs, et Willaert publia un recueil de ricercare à trois voix.

Il était très populaire de son vivant, ce qui explique les nombreuses transcriptions instrumentales qui paraissaient un peu partout en Europe. Provenant d'une tablature pour clavier, Dessus le marché d'Arras futpublié en 1544 par l'éditeur parisien Pierre Attaingnant. Sa version reste fi dèle à l'écriture de Willaert, seules les ornementations ont été ajoutées. Claveciniste virtuose et aveugle, le napolitain Antonio Valente écrivit une version diminuée de Chi la dira (Intavolatura de cimbalo, 1576) tandis que la Canzona Allez mi faut di Adriano (Il secondo libro de intavolatura di liuto, 1599) de Giovanni Antonio Terzi étaient à l'origine un duo pour deux luths. Par contre, le Tiento IV sobre Qui la dira de l'espagnol Antonio de Cabezon était une nouvelle composition, sur le même thème que la chanson de Willaert.

C'est vers la fi n du XVIe siècle que la virtuosité instrumentale prit de l'importance en Italie. Les caractéristiques sont ici les diminutions des voix d'œuvres polyphoniques richement ornementées et qui peuvent être interprétées comme une sorte de commentaire de l'œuvre originale. A la fontana du cornettiste vénitien Giovanni Bassano (Ricercate, passaggi et cadentie, 1585) est basé sur la partie supérieure de la chanson À la fontaine de Willaert. Joyssance, de Vincenzo Bonizzi (Alcune opere, 1626), organiste et violiste originaire de Parme, est écrit pour la viola bastarda. Ces diminutions ne se limitent pas à une seule voix de l'œuvre

initiale de Willaert, mais sautent continuellement du haut vers le bas et remplissent ainsi la tessiture complète de la basse de viole.

PIET STRYCKERS

ADRIAEN WILLAERT

—

Als er één komponist was die het Italiaanse muziekleven rond het midden van de 16e eeuw domineerde, dan was het wel de Vlaming Adriaen Willaert (ca. 1490-1562). Mogelijk werd hij geboren in Roeselare, maar tijdens zijn jeugdjaren had hij sterke banden met de stad Brugge. Na een studietijd bij Jean Mouton in Parijs, trad hij rond 1515 in dienst van de adellijke familie d’Este, die er in Ferrara één van de bloeiendste renaissancehoven op na hield, en die hem tevens talrijke kontakten bezorgde met het pauselijke hof in Rome. In 1527 werd hij dan kapelmeester van de San Marco te Venetië, een positie die hij tot aan zijn dood zou bekleden.

Alhoewel de ekonomische macht van deze rijke handelsstad al iets aan het tanen was, was haar kulturele uitstraling nog altijd toonaangevend voor gans Europa. De stad spaarde geen moeite om de allerbeste zangers en instrumentisten in dienst te nemen, en ze werd een broeinest van muzikaal talent en innovatie. Het kapelmeestersschap van de San Marco werd dan ook aanzien als één van de topposities van het Europese muziekleven. Willaerts faam was spoedig zo groot dat talrijke jonge komponisten naar de dogenstad afreisden om er van "Messer Adriaeno" les te krijgen, en op die wijze beïnvloedde Willaert een ganse generatie van musici. Andrea Gabrieli, Cipriaan de Rore, Jakob Buus, Constanzo Porta, Nicola Vicentino en de theoreticus Gioseff o Zarlino behoorden tot zijn leerlingen.

Adriaen Willaert was een veelzijdig komponist, bedrijvig in vele genres. Op het gebied van de kerkmuziek leverde hij een belangrijke bijdrage tot de ontwikkeling van het motet, en stimuleerde hij het ontstaan van meerkorige muziek met zijn dubbelkorige psalmen.

Maar ook profane genres genoten zijn interesse. Franse chansons schreef hij niet enkel tijdens zijn Parijse jaren, maar ook in Italië, waar een frankofi ele smaak in de mode was, o.a.

bij paus Leo X en aan het hof van Ferrara, waar Ercole II d’Este gehuwd was met Renée de France. De vroegste chansons verwijzen nog naar het voorbeeld van Josquin en Jean Mouton: zo bijvoorbeeld het schalkse Dessus le marché d’Arras met de typische afwisseling tussen een hoog en een laag stemmenpaar, en ook het driestemmige Allons, allons gay. De chansons uit de latere verzamelingen zoals Iouissance vous donneray en Qui la dira la peine de mon coeur onderscheiden zich door vloeiendere melodische lijnen, een grotere klankvolhied en een rijke imitatieve stijl, verwant aan het motet. Van Arousez vo violette, een liedje met een dubbelzinnige tekst, is het auteurschap niet met zekerheid vast te stellen, maar in enkele bronnen wordt het aan Willaert toegeschreven.

Ook als madrigaalkomponist speelde Willaert een rol, naast komponisten als Verdelot en Arcadelt die zich meer in dit genre specialiseerden. Het vierstemmige Quante volte diss’io is een vroeg werk, maar verraadt reeds Willaerts voorkeur voor de dichter Petrarca. Met Qual dolcezza giamai, een lofl ied aan de zangeres Polissena Pecorina, wijst Willaert naar een nieuwere fase in zijn madrigaalkunst: vijfstemmigheid wordt de norm, en de polyfone stijl is sterk verwant met het motet.

Terwijl het madrigaal eerder ernstig en gesofi stikeerd is van poetische en muzikale uitdrukking, is de villanesche alla napolitana veel lichtvoetiger en eenvoudiger. Rond de jaren 1530 kwam deze vorm in de mode, en Willaert liet er in de jaren 1544/45 een verzameling van verschijnen. De teksten schilderen allerlei volkse tafereeltjes, uit het leven gegrepen: een vrijer die spot met oude wijven (Vecchie letrose), een dame die haar afgewezen minnaar op straat uitlacht (Sempre mi ride sta), een jongeling die in een serenade een afspraak met zijn liefj e probeert te versieren (O bene mio). Cingari simo is een mascherata alla napolitana, waar als zigeuners gemaskerde individuen enkele lichtekooien opvrijen met hoogst dubbelzinnige toespelingen. In dit stuk ontleende Willaert de cantuspartij van een driestemmige versie van Giovanni Da Nola, maar plaatste ze in de tenorstem. De versies voor solostem en luit van O quando a quando havea en O bene mio zijn intabulaties van de Spaanse vihuelaspeler Diego

Pisador (Libro de musica de vihuela, 1552). Un giorno mi prego is een villotta, een Noord-Italiaanse variante van de villanesche. Deze waren eigenlijk dansliederen die gebruikt werden bij pantomimevoorstellingen. Zoia zentil en Occhio non fu giamai behoren tot een ernstiger genre: het zijn canzones, gedicht door Angelo Beolco, bijgenaamd «Il Ruzzante». Een buitenbeentje is het venijnige E se per gelosia. Dit verscheen in 1541 in een bundel met bicinia, tweestemmige stukken die dikwijls bij het muziekonderricht gebruikt werden.

Adriaen Willaert schreef ook pure instrumentale muziek. In 1540 publiceerde hij samen met zijn collega Julio aa Modena en enkele leerlingen de bundel Musica Nova, een verzameling Ricercares, polyfone instrumentale stukken in een motetachtige stijl. Het waren de eerste werken in die soort die ooit gedrukt werden. Spoedig kregen ze navolging van andere komponisten, en ook Willaert liet later nog een reeks driestemmige Ricercares volgen.

Dat Willaerts muziek in zijn tijd reeds overbekend was, daarvan getuigen de vele instrumentale bewerkingen die her en der in Europa verschenen. Dessus le marché d'Arras komt uit een klaviertabulatuur van de Parijse muziekuitgever Pierre Attaignant uit 1544. Zijn versie volgt Willaerts stemvoering getrouw, maar voegt er versieringen aan toe. De blinde Napolitaanse klaviervirtuoos Antonio Valente maakte een gediminueerde versie van Chi la dira (Intavolatura de cimbalo, 1576), en Giovanni Antonio Terzi’s Canzon Allez mi faut di Adriano (Il secondo libro de intavolatura di liuto, 1599) is oorspronkelijk een duet voor twee luiten. Daarentegen is de Tiento IV sobre Qui la dira van de Spanjaard Antonio de Cabezon een nieuwe kompositie op hetzelfde thema als Willaerts chanson.

Instrumentale virtuositeit was een element dat tegen het eind van de 16e eeuw sterk opkwam in Italië. Typisch hierbij zijn de diminuties, dit zijn rijkelijk uitversierde stemmen van polyfone werken, die als een soort van kommentaar bij het oorspronkelijke werk konden uitgevoerd worden. A la fontana van de Venetiaanse cornetist Giovanni Bassano (Ricercate, passagi et cadentie, 1585) is gebaseerd op de superiuspartij van Willaerts chanson À la fontaine. Joyssance van de Parmesaanse organist en gambaspeler Vincenzo Bonizzi (Alcune opere,

1626) is geschreven voor de viola bastarda. Deze diminuties beperken zich niet tot één enkele stem van Willaerts origineel, maar verspringen voortdurend van hoog naar laag, en bestrijken zo de volledige tessituur van de viola da gamba. PIET STRYCKERS

ADRIAEN WILLAERT

—If we had to name one composer who dominated Italian musical life in the middle of the

16th century, it would have to be the Fleming Adriaen Willaert (c. 1490-1562). He was probably born in Roeselare, but during his youth had strong links with the city of Bruges. After a period of study with Jean Mouton in Paris he entered the service of the noble family of Este in Ferrara in approximately 1515; this family held one of the most fertile of the Renaissance courts and he was thus assured of numerous contacts with the Papal Court in Rome. In 1527 he became maestro di cappella of St. Mark’s in Venice, a position that he was to occupy until his death.

Notwithstanding the fact that the economic might of that rich merchant city was beginning to wane, its artistic splendours still set the tone for the whole of Europe. Th e city spared no eff ort to engage the best singers and instrumentalists that were available and thus became a breeding-ground for musical talent and innovation. Th e musical direction of St. Mark’s was therefore seen as one of the most elevated positions of contemporary European musical life. Willaert’s fame increased so rapidly that many young composers travelled to the City of the Doges to study with "Messer Adriaeno"; in this manner Willaert was able to infl uence a whole generation of musicians. Andrea Gabrieli, Ciprian de Rore, Jakob Buus, Constanzo Porta, Nicola Vincentino and the theoretician Gioseff o Zarlino were but a few of his pupils.

Adriaen Willaert was a composer of many facets, one who was active in many genres. In the fi eld of religious music he fulfi lled an important role in the development of the motet and stimulated the creation of polychoral music with his psalms for two choirs.

He was nevertheless active in secular music; he had written French chansons during his Paris years and continued to write them in Italy where a taste for things French was fashionable at the time, notably with Pope Leo X and the Court of Ferrara, thanks to Ercole II d’Este’s marriage to Renée de France. His earliest songs still betray the infl uences of models by

Josquin and Mouton, as we can see in the mischievous Dessus le marché d’Arras with its typical alternations between high and low voices and also in the three-part Allons, allons gay. Th e songs from his later collections such as Jouissance vous donneray and Qui la dira la peine de mon coeur can de distinguished by their fl owing melodic lines, an increased fullness of sound and a richly imitative style that was more usually applied to the motet. Th e exact origin of Arousez vo violette and its suggestive text cannot be stated with any certainty, although several sources attribute its authorship to Willaert.

Willaert also composed madrigals, alongside composers such as Verdelot and Arcadelt who specialised more in the genre. Th e four-part Quante volte diss’io is an early work, but already demonstrates Willaert’s preference for the poet Petrarch. Willaert points towards a new style in his madrigal writing with Qual dolcezza giamai, an ode to the singer Polissena Pecorina; fi ve-part writing became the norm and the polyphonic style strongly resembles that of the motet. Th e madrigal was more serious and sophisticated in its poetical and musical expression, but the villanesca alla napolitana was much lighter and simpler. Th is form became fashionable in the 1530s, whilst Willaert published a collection of them in 1544-1545.

Th e texts depict all sorts of popular tableaus taken directly from life; a suitor who pokes fun at old wives (Vecchie letrose), a lady who ridicules her rejected lover on the street (Sempre mi ride sta), and a youth who tries to arrange a rendezvous with his lover in a serenade (O bene mio). Cingari simo is a mascherata alla napolitana in which individuals disguised as gypsies try to chat up a few courtesans with highly suggestive texts. Willaert borrows the cantus part in this piece from a three-part version by Giovanni da Nola, but places it in the tenor voice. Th e versions for solo voice and lute of O quando a quando havea and of O bene mio are intabulations of works by the Spanish vihuela player Diego Pisador, taken from his Libro de musica de vihuela (1552). Un giorno mi pregò is a villotta, a Norhern Italian variant of the villanesca. Th ese works were originally songs for dances that were used in pantomime performances. Zoia zentil and Occhio non fu giamai belong to a more serious genre; they are canzone, with words by Angelo Beolco,

nicknamed "Il Ruzante". Th e odd one out in this collection is the venomous E se per la gelosia; it appeared in 1541 in a collection of bicinia, two-part pieces that were also used for music teaching.

Adriaen Willaert also wrote pure instrumental music. Together with his colleague Julio da Modena and several pupils he published a collection entitled Musica Nova in 1540; this was a collection of ricercare, polyphonic instrumental pieces in motet style. Th ese were the fi rst works in such a style to be printed. Th ey were rapidly followed by works by other composers, whilst Willaert himself would later publish a series of three-part ricercare.

Th e many instrumental arrangements that appeared all over Europe of Willaert’s music bear witness to the fact that his music was, if anything, too well-known in his lifetime. Dessus le marché d’Arras comes from a keyboard tabulature from the Parisian music publisher Pierre Attaingnant dated 1544. His version follows Willaert’s voice-leading exactly, although he adds decorations to it. Th e blind Neapolitan keyboard virtuoso Antonio Valente made a reduced version of Chi la dira (Intavolatura de cimbalo, 1576), whilst Giovanni Antonio Terzi’s Canzon Allez mi faut di Adriano (Il secondo libro de intavolatura di liuto, 1599) was originally a duet for two lutes. On the other hand, the Tiento IV sobre Qui la dira by the Spanish composer Antonio Cabezon is a new composition on the same theme as Willaert’s song.

Instrumental virtuosity was a strongly growing element in music in Italy at the end of the 16th century. Typical of this are the divisions, which are richly ornamented voices from polyphonic works that can be performed as a type of commentary on the original work. Th e Venetian cornettist Giovanni Bassano’s A la fontana (Ricercate, passaggi et cadentie, 1585) is based upon the superius part of Willaert’s song À la fontaine. Jouyssance by the Parma organist and gamba player Vincenzo Bonizzi (Alcune opere, 1626) is written for the viola bastarda. Th ese divisions are not limited to the single line of Willaert’s original, but continually leap from high to low, covering the whole range of the viola da gamba.

PIET STRYCKERS

TRANSLATION: PETER LOCKWOOD

ADRIAEN WILLAERT

—

Der Flame Adriaen Willaert (ca. 1490-1568) beherrschte um die Mitte des 16. Jahrhunderts das Musikleben Italiens. Er wurde wahrscheinlich in Roeselare geboren, doch verbanden ihn in seiner Jugend feste Bande mit der Stadt Brügge. Nach seinem Studium bei Jean Mouton in Paris trat er um 1515 in den Dienst der adeligen Familie Este, die in Ferrara einen der blühendsten Höfe der Renaissance unterhielt. Da wurde ihm auch geholfen, in Kontakt mit dem päpstlichen Hof in Rom zu treten.

Im Jahre 1527 wurde er zum Kapellmeister der Markus-Kirche in Venedig ernannt, und hatte diesen Posten bis zu seinem Tod inne. Obwohl die wirtschaftliche Macht dieser reichen Handelsstadt im Niedergang begriff en war, so verbreitete sich ihre kulturelle Ausstrahlung weiterhin über ganz Europa. Die Stadt schreckte vor keinerlei Bemühungen zurück, um stets die besten Sänger und Musiker in ihrem Dienst zu haben, wodurch sie zu einem Nährboden für Talente und musikalische Neuerungen wurde. Der Titel eines Kapellmeisters der Markus-Kirche wurde also für das gesamte europäische Musikleben als bedeutend betrachtet. Willaerts Ruf wurde so groß, daß sich zahlreiche junge Komponisten in die Dogenstadt begaben, um Unterricht von "Messer Adriaeno" zu erhalten, und so beeinfl ußte Willaert eine ganze Musikergeneration. Unter seinen Schülern fi ndenwir Andrea Gabrieli, Cipriano de Rore, Jacob Buus, Constanzo Porta, Nicola Vicentino sowie den Th eoretiker Gioseff o Zarlino.

Adriaen Willaert war ein eklektischer Komponist. Was die Kirchenmusik anbelangt, so trug er zur Entwicklung der Motette bei und förderte die Entstehung der polychoralen Musik mit ihren Psalmen und Doppelchören. Doch er interessierte sich auch für die weltliche Musik. So komponierte er französische Lieder, und das nicht nur während seines Aufenthalts in Paris, sondern auch in Italien, wo die französische Musik in Mode war, unter anderem bei

Papst Leo X. sowie am Hof Ercoles II. von Este, der Renée von Frankreich geheiratet hatte. Die ersten dieser Lieder sind noch von Josquin und Mouton beeinfl ußt: so zum Beispiel das schelmische Dessus le marché d’Arras, bei dem die Diskantstimmen und die tiefen Stimmen in typischer Weise abwechseln, sowie das dreistimmige Allons, allons gay. Die Lieder, die aus den letzten Bänden stammen, wie zum Beispiel Jouissance vous donneray und Qui dira la peine de mon coeur, unterscheiden sich durch eine fl ießendere melodische Linie, größere Klangfülle und einen reichen imitativen Stil, der der Motette verwandt ist. Der Komponist der kleinen Weise mit dem doppelsinnigen Text Arousez vo violette ist nicht mit Sicherheit bekannt; das Werk wird aber von einigen Quellen Willaert zugeschrieben.

Auch als Madrigalkomponist zeichnete sich Willaert aus, jedoch nicht im gleichen Maße wie Verdelot und Arcadelt, die Spezialisten dieser Gattung waren. Unter seinen ersten Werken verrät das vierstimmige Quante volte diss’io die Vorliebe, die Willaert für den Dichter Petrarca hatte. Mit Qual dolcezza giamai, einem Loblied auf die Sängerin Polissena Pecorina, begann er eine neue Phase seiner Madrigalkunst; der Satz ist hier fünfstimmig und der polyphone Stil mit dem der Motette nah verwandt. Während das Madrigal in seinem dichterischen und musikalischen Ausdruck eher ernst und erlesen ist, ist die Villanesca alla napolitana weit leichter und einfacher. Diese Form kommt um 1530 in Mode, und 1544/45 veröff entlicht Willaert davon einen Band. Die Texte schildern kleine volkstümliche Szenen aus dem täglichen Leben: ein Verliebter, der sich über alte Frauen lustig macht (Vecchie letrose), eine Dame, die öff entlich einen ehemaligen Verehrer lächerlich macht (Sempre mi ride sta), ein junger Mann, der eine Serenade singt, um von seiner Liebsten ein Stelldichein zu erhalten (O bene mio). Cingari simo ist eine Mascherata alla napolitana, die maskierte Leute beschreibt, die als Zigeuner verkleidet sind und einige Freudenmädchen befreien, wobei Wortspiele und Doppelsinniges nicht fehlen. In diesem Stück ließ sich Willaert vom Sopran einer dreistimmigen Fassung von Giovanni da Nola beeinfl ussen, transkribierte sie allerdings für Tenor.

Die Fassungen für Solostimme und Laute von O quando a quando havea und O bene mio sind Intabulierungen des spanischen Virtuosen Diego Pisador (Libro de musica de vihuela, 1552). Un giorno mi pregò ist eine Villotta, eine Variante der norditalienischen Villanesche. Es handelt sich eigentlich um Tanzweisen, die bei Pantomimeauff ührungen Verwendung fanden. Zoia zentil und Occhio non fu giamai gehören zur ernsten Gattung: es sind zwei «Canzonen», die vom Dichter Angelo Beolco, mit dem Beinamen "Il Ruzzante" geschrieben wurden. Das Lied E se per gelosia zeichnet sich durch seinen ätzenden Text aus. Es erschien 1541 in einem Band mit Bicinia, zweistimmigen Stücken, die gerne beim Musikunterricht eingesetzt wurden.Adriaen Willaert schrieb auch Instrumentalmusik. Er veröff entlichte im Jahre 1540 mit seinem Kollegen Julio de Modena sowie mit einigen Schülern den Band Musica Nova, eine Sammlung von x, d.h. von polyphonen Instrumentalstücken im Motettenstil. Es handelt sich hier um die ersten veröff entlichten Werke dieser Art.

Andere Komponisten folgten dem Beispiel sehr bald, und Willaert veröff entlichte auch noch einen Band von dreistimmigen Ricercari. Daß Willaerts Musik zu seinen Lebzeiten sehr beliebt war, davon zeugen die zahlreichen Instrumentaltranskriptionen, die überall in Europa erschienen. Das von einer Claviertablatur stammende Dessus le marché d’Arras wurde 1544 vom Pariser Herausgeber Pierre Attaingnant veröff entlicht. Seine Fassung bleibt der Komposition Willaerts treu und fügt bloß Verzierungen hinzu. Der blinde Cembalovirtuose Antonio Valente aus Neapel schrieb eine diminuierte Fassung von Chi la dira (Intavolatura de cimbalo, 1576), während die Canzon Allez mi faut di Adriano(Il secondo libro de intavolatura di liuto, 1599) von Giovanni Antonio Terzi ursprünglich ein Duo für zwei Lauten waren. Dagegen ist Tiento IV sobre Qui la dira des Spaniers Antonio de Cabezon eine neue Komposition auf das gleiche Th ema wie das Lied Willaerts.

Gegen Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts gewinnt die instrumentale Virtuosität in Italien an Bedeutung. Charakteristisch dafür sind Diminutionen der Stimmen von reich verzierten polyphonen Werken, die als eine Art Kommentar zum ursprünglichen Werk interpretiert

werden können. A la fontana des venezianischen Kornettspielers Giovanni Bassano (Ricercate, passaGgi et cadentie, 1585) baut auf dem obersten Part des Liedes À la fontaine von Willaert auf. Jouissance von Vincenzo Bonizzi (Alcune opere, 1626), einem Organisten und Gambisten aus Parma, ist für Viola bastarda geschrieben.

Hier beschränken sich die Diminutionen nicht auf eine einzige Stimme von Willaerts Originalwerk, sondern springen unaufhörlich von oben nach unten und füllen so den gesamten Tonumfang der Baßgambe aus.

PIET STRYCKERS

ÜBERSETZUNG: SILVIA BERUTTIRONELT

1. Qual dolcezza giamaiQual dolcezza giamaiDi canto di SirenaInvolò i sensi e l’alm’a chi l’udiro,Che di quella non sia minor assaiChe con la voce angelica e divinaDesta nei cor la bella Pecorina.A la dolce armoniaSi fa serena l’aria,S’acqueta il mar, taccion’i venti,E si rellegra il ciel di gir’in giro.I santi angeli intentiChinand’in questa part’il vago visoS’oblian’ogni piacer del paradiso.Et ella in tant’honoreDice con lieto suon: qui regn’ Amore.

Doux est le chant de la sirèneQui a toujours séduit celui qui l’écoute.La croix de la belle Pecorina,Angélique et divine,Séduit tout autant nos cœurs.Par cette harmonie, L’air devient serein,La mer se calme,Les vents se taisentEt le ciel nous encercle de joie,Les anges attentifsInclinent leurs beaux visages vers elle.Ils oublient tous les plaisirs du Paradis.Et elle, honorée par tous,Dit gaiement : l’Amour règne ici.

What sweetness of the Sirens’ song once seduced the senses and the souls of those who heard them.Th at which the fair Pecorina arouses in our hearts with her angelically divine voiceis no less beautiful. Th rough its sweet harmony the air becomes serene,the sea is calm and the winds are silent,whilst the heavens rejoice from day to day. Th e holy angels are full of attentionand bow their fair heads to her.Th ey forget the pleasures of Paradise.She, honoured by all,says merrily: Love reigns here.

2. Zoia zentilZoia zentil che per secreta viaTen vai di cuor in cuore,Portando la legrezza de l’amore.Col to venir celatoTanto ben m’hai portato,Che per legrezza tantaEt m’è forza che canta:Fa li le li lon.

Beato colui son Ch’a lo so amor in don,L’amor n’è bel n’è caroChe s’ha col so darano.Pì ch’eli se paga, manco è da stimare,L’amor donato non si po pagare.

Joie gentille, tu vas d’un cœurÀ l’autre par des chemins secretsEn portant la légèreté de l’amour avec toi.Ta venue discrèteM’a apporté tant de bienQue cette grande joieMe fait chanterFa li le li lon.

Heureux est celuiQui reçoit l’amour en cadeau,L’amour n’est ni beau, ni cherS’il faut l’obtenir avec de l’argent,Plus on le paye, moins il est estimé,L’amour off ert ne se paye pas.

Kindly joy, you run from one heartto another on secret pathscarrying the lightness of love with you.your hidden arrivalhas done me so much goodthat through an excess of joyI must sing fa li le li lion.

Happy is he who receives love as a gift.Love is neither beautiful nor to be cherishedif it is obtained with money.Th e more you pay, the less you value it;love that is given is beyond price.

3. Dessus le marché d’ArrasDessus le marché d’Arras,Myrely, myrela bon bas,Jay trouvé ung espagnart, Sentin, senta, sur le bon pas,Myrely, myrela, bon bille,Myrely, myrela, bon bas,Il me dist, fi lle escouta,Myrely...De l’argent on vous donra,Sentin, senta... Myrely...

5. Allons, allons gayAllons, allons gay m’amye, ma mignonne,Allons, allons gay, gayement vous et moy.Mon père a faict fair ung chasteau,Il n’est pas grand, mais il est beau !Et allons, allons gay, gayement, ma mignonne.Il n’est pas grand, mais il est beau,D’or et d’argent sont les carreaulx :Et allons, allons gay, gayement, ma mignonne.Et si a troys beaux chevaulx,Le roy n’en a point de si beaulx :Et allons, allons gay, gayement, ma mignonne.L’ung est gris, l’autre est moreau,Mais le petit est le plus beau :Et allons, allons gay, gayement, ma mignonne.Ce sera pour aller jouer,Pour ma mignonne et pour moy :Et allons, allons gay, gayement, ma mignonne.J’irons jouer sur le muguet,Et y ferons ung chappeletPour ma mignonne et pour moy :Et allons, allons gay, gayement, ma mignonne.

In the market at Arrasmyrely, myrela, good and cheap,I met a Spaniard,sentin, senta, good and cheap,myrely, myrela, marble and good.He said to me "Girl, listen",myrely..."you’ll get some money",sentin, senta... myrely...

Come, let’s be merry, my sweet, my darling,come, let’s be merry, merry you and I.My father had a castle built;it’s not big, but it’s beautiful!Come, let’s be merry, my darling.It’s not big, but it is beautiful;the tiles are of gold and silver.Come, let’s be merry, my darling.He also has three fair horses;the king had none so fi ne.Come, let’s be merry, my darling.One is grey, the other dark brown,but the smallest is the most beautiful.Come, let’s be merry, my darling.He is the one we’ll use to go out and play,he’s for my darling and I!Come, let’s be merry, my darling.I’ll go and sing amidst the lily of the valley;we’ll make a garland out of themfor my darling and I.Come, let’s be merry, my darling.

7. Quante volte diss’ioQuante volte diss’io,Alhor pien di spavento:«Costei per fermo nacque in paradiso ! »Cosi carco d’oblioIl divin portamentoE’l volto e le parole e’l dolce risoM’haveano, e si divisoDa l’imagine vera,Ch’io dicea sospirando:«Qui come venn’io, o quando?»Crecendo esser in ciel, non là dov’era.Da ind’in qua mi piaceQuest’herba si ch’al trove non ho pace.

Combien de fois ai-je dit,Le cœur plein d’angoisse« Elle est certainement née au paradis ! »J’ai complétement oubliéSon attitude divine, son visage,Ses paroles et son doux sourireQui m’avaient éloigné De son image réelleEt j’ai dit en soupirant :Comment et quand suis-je venu ici ?M’imaginant au ciel et non dans la réalité,Depuis ce jour-là, j’aime tant ces plainesQue je ne trouve pas la paix ailleurs.

How many times have I said,my heart full of fear,"She was certainly born in Paradise!"Filled with forgetfulness as I was,her divine bearing, her face,her words and her sweet smilehad taken me so far from her real imagethat I said sighing"How and when have I come here?"believing myself to be in Heaven and not where I wasFrom that day I have loved these meadows so muchthat I can fi nd no peace elsewhere.

8. Vecchie letrose non valete nienteVecchie letrose non valete nienteSe non a far l’aguaito per la chiazza.Tira alla mazzaVecchie letrose scannaros’e pazze.

Laides vieilles, vous ne valez rien,Si ce n’est pour épier.Frappez au bâton,Laides vieilles, égorgeuses et folles.

9. Qui la dira la peine de mon cœurQui la dira la peine de mon cœurEt la douleur que pour mon amy porte,je ne soutiens que tristesse et langueur,J’aymeroie mieux certes en estre morte.

12. E se per gelosiaE se per gelosiaMi fai tal compagnia,La colpa non è mia,La causa vien da te.Io te farò stentar,Stentar sul buso,D’ho marito me.

Et si c’est par jalousieQue tu restes toujours auprès de moi,La faute n’est pas mienne,La raison vient de toi.Je te ferai patienter,Une querelle te fera patienterParce que j’ai un mari.

Nasty old hags you are wothless,except to set an ambush in the thicketPull on the club,nasty old hags, thieving and mad.

Who can tell the pain in my heartand the sorrow that I bear for my friend.I know only sadness and weariness,I would much rather be dead.

If it is because you are jealous of me that you are always near me, It is not my fault Th e reason comes from you.I will make you suff er,You will be hurt in a brawl,because I have a husband.

13. Un giorno mi pregòUn giorno mi pregò una vedovellaD’andar un dur scoglio con lei passare.Navigando su la sua navicellaCon arte il timon sa ben governare.Ma coni la lingua intrigaGridando barca siaSta lì tien duro vogaPrem’a sta bona via.Co’l rem’in mezo mi miss’a vogareA lei molto piacque’l mio gran stentare.Co’l vent’in poppa pensai d’anegare.Ma m’aiutò da Berghem mio compareEt sospirando dissi:Così tratti gl’amiciSu la tua navicella.

Un jour une jeune veuve m’a priéDe franchir avec elle un dur écueil.Elle dirigeait son petit bateauEn utilisant adroitement le gouvernail,Mais dans un langage étrangeElle encourageait son embarcationÀ garder la bonne direction.Moi aussi je Me suis mis à ramerMes grands eff orts l’ont ravis.Avec le vent en poupe, j’ai craint de me noyer.Mais un ami de Bergame m’a secouruEn soupirant j’ai dit :Alors, ma jeune veuves traites-tuToujours ainsi tes amis dans ton petit bateau ?

One day a young widow asked me to sail round a dangerous reef with her.She directed her little boatand knew how to use the rudder skilfully.With a sly and crafty voiceshe called to her boat"stay there, keep going, row, you’re on the right track."I picked up the oars and began to row.My great eff orts pleased her greatly.I thought that I would drown, there was so much wind in my sails,but a friend from Bergamo came to help me.Sighing, I said"Well, my young widow,do you always treat friends like thiswhen they’re in your boat?"

15. Cingari simoCingari simo venit’a giocareDonn’alla coriolla de bon core.Ch’el è dentro ch’el è furoreS’el è dentr’ha più sapore.

Calate iuso per ve solazareCa iocarimo un po per vostr’amoreCh’el è dentro ch’el è furoreS’el è dentr’ha più sapore.

Se noi perdiamo pagamo un carlinoE se perdete voi pagate il vino.Ch’el è dentro ch’el è furoreS’el è dentr’ha più sapore.

Nous sommes des tziganes et nous sommes venus Vous jouer de bon cœur « La femme à la couronne de fl eur ». Qu’il soit à l’intérieur ou à l’extérieur,S’il est dedans il a plus de saveur.

Venez en bas et reposez-vous parce que Nous jouons un peu par amour pour vous. Qu’il soit à l’intérieur ou à l’extérieur, S’il est dedans il a plus de saveur.

Si nous perdons, nous vous paierons un souEt si vous perdez, vous paierez le vin.Qu’il soit à l’intérieur ou à l’extérieur, S’il est dedans il a plus de saveur.

We are gypsies and we have come to play you"Th e Lady With Th e Crown Of Flowers" with all our heart.It can be inside, it can be outside,if it is inside it will be better.

If we lose, we’ll pay you a carlino;if you lose, you’ll pay for the wine.It can be inside, it can be outside,if it is inside it will be better.

Come down here and take your ease, forWe play partly out of love for you.It can be inside, it can be outside,if it is inside it will be better.

16. A quand’a quand’haveva A quand’a quand’haveva una vicinaCh’era a vedere la stella Diana.Tu la vedevi, tu li parlaviBeato te se la basciati tu.

Che veramente pare una reginaOgn’uno ne faria inamorare.Tu la vedevi, tu li parlaviBeato te se la basciati tu.

Che quando se levava la matinaPhebo per scorno se ne ritornava.Tu la vedevi, tu li parlaviBeato te se la basciati tu.

Mo mi credeva starne contentoEt trovoomi le mani pien di vento.Tu la vedevi, tu li parlaviBeato te se la basciati tu.

Un jour, j’ai eu une voisineComparable à l’étoile Diane.Tu l’as vue,tu lui a parlé,Heureux si tu pouvais l’embrasser.

En vérité, pareille à une reine,Chacun en est amoureux.Tu l’as vue, tu lui a parlé,Heureux si tu pouvais l’embrasser.

Quand elle se levait le matinApollon se retirait honteuxTu l’as vue,tu lui a parlé,Heureux si tu pouvais l’embrasser.

J’ai cru être heureux avec elle,Mais me voici les mains vides.Tu l’as vue,tu lui a parlé,Heureux si tu pouvais l’embrasser.

Once, once I had a neighbourwho looked like the morning star Diana.You saw her, you spoke with her,lucky were you, if you kissed her.

In truth she looked like a queen,she made everyone fall in love with her.You saw her, you spoke with her,lucky were you, if you kissed her.

When she rose in the morning,Apollo the sun god retired abashed.You saw her, you spoke with her,lucky were you, if you kissed her.

I, I believed that I was happy with her,but here I am now with only the wind in my hands.You saw her,you spoke with her,lucky were you, if you kissed her.

17. Joyssance vous donnerayJoyssance vous donnerayMon amy ie vous menerayLa ou pretent nostre’ esperanceVivant ne vous laisserayEncroire quant mort serayL’esprit aura en souvenance.

19. Arousez vo violetteArousez vo violette,Arousez vo violier,Arousez vo violette :La fi lle d’un jardinierEstoit aymant par amourette,Son amy luy donne un baiser,Pretendant faire la chosette,Le jeu d’amours trop bien luy haitte,Luy a dit : « Mon amy cher,Arousez vo violier,Arousez vo violoette,Arousez vo violier. »

I shall give you joy;my friend, I will lead youto that for which we hope.I shall not leave you whilst I live,and even when I am deadyour spirit will remember me.

Water your violets,water your stocks,water your violets.Th e girl fell in love,fell for a gardener.Her friend gave her a kissand wanted to go much further.He ardently desired to play Love’s games,but she replied "My dear friend,go water your stocks,go water your violetsgo water your stocks".

20. O bene mio famm’uno favoreO bene mio famm’uno favoreChe questa sera ti possa parlare. E s’alcuno ti ci trovaE tu grida: «chi vend’ova».

Vieni senza paura e non bussareButta la porta che porai entrare.E s’alcuno ti ci trovaE tu grida: chi vend’ova.

Alla fi nestra insino alle due horeFarò la spia che porai entrare.E s’alcuno ti ci trovaE tu grida: chi vend’ova.

Ma chère, fais-moi une faveur,Que je puisse te parler ce soir.Si on te découvre,Tu cries « qui vend des oeufs ? » Viens sans peur, sans frapper,Ouvre la porte, tu peux entrer.Si on te découvre,Tu cries « qui vend des oeufs ? »

À la fenêtre jusqu’à l’heure,Je ferai le guet afi n que tu puisses entrerSi on te découvre,Tu cries « qui vend des oeufs ? »

My darling, do me the favourof letting me speak with you tonight.And if someone should fi nd you here,call out "Eggs for sale!"

Come without fear and don’t bother to knock.Open the door, for you may enter.And if someone should fi nd you here,call out "Eggs for sale!"

I will watch by the windowuntil two o’clock to let you in.And if someone should fi nd you here,call out "Eggs for sale!"

22. Occhio non fu giamai che lachrimasseOcchio non fu giamai che lachrimasseCon sì rason di doia da morire.O car’ amore, O bell’ amore,O dolc’ amore, O fi n’ amore,Che tien il mondo inamorà,Hai corona di quanti amor fu ma’.

Jamais yeux versèrent des larmesAvec autant de raisons de devoir mourirO cher amour, O bel amour,O doux amour, O fi n amour,Tu rends le monde amoureuxTu portes la couronne de chaque amour qui fut.

23. Sempre mi ride sta Sempre mi ride sta donna da beneQuando passeggio per mezo sta via.La riderella, la pazzarella,Non vi ca rideHa Ha Ha ridemo tutti Per darli piacere.

Cette dame se moque toujours de moiLorsque je passe dans la rue,La petite moqueuse,la petite folle,Il vaut mieux en rireHa ha ha viens en cœurPour lui faire plaisir.

Th ere were never eyes that weptwith so much reason over the pains of death.O dear love,o beautiful love,o sweet love, o fi ne love,you make the world fall in love,you bear the crown of every love that has ever been.

Th is well brought up lady always laughs at mewhen I go down the street.Th e laughing little woman,the mad little woman,she does nothing but laugh.Ha, ha, ha, we all laugh to make her happy.

creating diversity...

Listen to samples from the new Outhere releases on:Ecoutez les extraits des nouveautés d’Outhere sur :

Hören Sie Auszüge aus den Neuerscheinungen von Outhere auf:

www.outhere-music.com

RIC 331

Outhere is an independent musical productionand publishing company whose discs are publi-shed under the catalogues Æon, Alpha, Fuga Libera, Outnote, Phi, Ramée, Ricercar and Zig-Zag Territoires. Each catalogue has its own welldefined identity. Our discs and our digital productscover a repertoire ranging from ancient and clas-sical to contemporary, jazz and world music. Ouraim is to serve the music by a relentless pursuit ofthe highest artistic standards for each single pro-duction, not only for the recording, but also in theeditorial work, texts and graphical presentation.We like to uncover new repertoire or to bring astrong personal touch to each performance ofknown works. We work with established artistsbut also invest in the development of young ta-lent. The acclaim of our labels with the public andthe press is based on our relentless commitmentto quality. Outhere produces more than 100 CDsper year, distributed in over 40 countries. Outhereis located in Brussels and Paris.

The labels of the Outhere Group:

At the cutting edge of contemporary and medieval music

30 years of discovery of ancient and baroque repertoires with star perfor-mers

Gems, simply gems

From Bach to the future…

A new look at modern jazz

Philippe Herreweghe’sown label

Discovering new French talents

The most acclaimed and elegant Baroque label

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Here are some recent releases…

Click here for more info