“Wicked” problems can’t be Strategy as a Wicked Increas ... · PDF...

Click here to load reader

Transcript of “Wicked” problems can’t be Strategy as a Wicked Increas ... · PDF...

www.hbr.org

Strategy as a Wicked Problem

by John C. Camillus

“Wicked” problems can’t be

solved, but they can be tamed.

Increasingly, these are the

problems strategists face—

and for which they are ill

equipped.

Reprint R0805GThis document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact

[email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

Strategy as a Wicked Problem

by John C. Camillus

harvard business review • may 2008 page 1

CO

PYR

IGH

T ©

200

8 H

AR

VA

RD

BU

SIN

ESS

SC

HO

OL

PU

BLI

SHIN

G C

OR

PO

RA

TIO

N. A

LL R

IGH

TS

RE

SER

VE

D.

“Wicked” problems can’t be solved, but they can be tamed.

Increasingly, these are the problems strategists face—and for

which they are ill equipped.

Over the past 15 years, I’ve been studying howcompanies create strategy—the most impor-tant responsibility of senior executives. Manycorporations, I find, have replaced the annualtop-down planning ritual, based on macroeco-nomic forecasts, with more sophisticated pro-cesses. They crunch vast amounts of consumerdata, hold planning sessions frequently, anduse techniques such as competency modelingand real-options analysis to develop strategy.This type of approach is an improvement be-cause it is customer- and capability-focusedand enables companies to modify their strate-gies quickly, but it still misses the mark a lot ofthe time.

Companies tend to ignore one complicationalong the way: They can’t develop models ofthe increasingly complex environment inwhich they operate. As a result, contemporarystrategic-planning processes don’t help enter-prises cope with the big problems they face.Several CEOs admit that they are confrontedwith issues that cannot be resolved merely bygathering additional data, defining issues more

clearly, or breaking them down into smallproblems. Their planning techniques don’tgenerate fresh ideas, and implementing thesolutions those processes come up with isfraught with political peril. That’s because, Ibelieve, many strategy issues aren’t just toughor persistent—they’re “wicked.”

Wickedness isn’t a degree of difficulty.Wicked issues are different because traditionalprocesses can’t resolve them, according toHorst W.J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber,professors of design and urban planning atthe University of California at Berkeley, whodescribed them in a 1973 article in PolicySciences magazine. A wicked problem has in-numerable causes, is tough to describe, anddoesn’t have a right answer, as we will see inthe next section. Environmental degradation,terrorism, and poverty—these are classic ex-amples of wicked problems. They’re the oppo-site of hard but ordinary problems, whichpeople can solve in a finite time period byapplying standard techniques. Not only doconventional processes fail to tackle wicked

This document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact [email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

Strategy as a Wicked Problem

harvard business review • may 2008 page 2

problems, but they may exacerbate situationsby generating undesirable consequences.

In the areas of public policy, software devel-opment, and project design, experts such asPeter DeGrace, Leslie Hulet Stahl, and JeffConklin have developed ways of spottingwicked problems and coping with them. De-Grace and Stahl wrote Wicked Problems, Righ-teous Solutions: A Catalogue of Modern SoftwareEngineering Paradigms (1990); Conklin au-thored Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Un-derstanding of Wicked Problems (2006). Policymakers, in particular, have put this powerfulconcept to good use, but it has been largelymissing from strategy discussions. Althoughmany of the problems companies face are in-tractable, they have been slow to acknowledgethe wickedness of strategy issues.

Between 1995 and 2005, I completed threeresearch projects that provided insights intowicked strategy problems. First, as part ofbenchmarking projects that the APQC (for-merly known as the American Productivity &Quality Center) and the Hong Kong Productiv-ity Council conducted, I analyzed 22 NorthAmerican, European, and Asian enterprisesthat use innovative strategic-planning tech-niques. They include ABB, Alcoa, Honeywell,John Deere, PPG Industries, Royal DutchShell, Siemens, Sprint, Whirlpool, and Xerox(China and USA). Second, I studied strategyimplementation in depth at seven of these en-terprises. Third, a colleague, Gaurab Bhardwaj,and I tracked DuPont’s pharmaceuticals busi-ness to learn how companies draw up strate-gies when returns will accrue only in the longrun and are highly uncertain. Based on thesestudies, I’ll explore in the following pages howcompanies can tame—since they can’t solve—such problems. I’ll conclude by describing aplanning process that helps PPG Industriestackle wicked issues.

What

Is

a Wicked Problem?

There are several ways to define a wickedproblem, but according to Rittel and Webber,it has some or all of 10 characteristics. (See thesidebar “The 10 Properties of Wicked Prob-lems.”) Caveat: The criteria are not a set oftests that mechanically determine wickedness;rather, they provide insights that help youjudge whether a problem is wicked.

Wicked problems often crop up when or-ganizations have to face constant change or

unprecedented challenges. They occur in a so-cial context; the greater the disagreementamong stakeholders, the more wicked theproblem. In fact, it’s the social complexity ofwicked problems as much as their technicaldifficulties that make them tough to manage.Not all problems are wicked; confusion, dis-cord, and lack of progress are telltale signs thatan issue might be wicked.

In my consulting work, I’ve found that whenfive characteristics are present in a strategy-related issue, executives agree they have awicked problem on their hands. I’ll list the keycriteria below and use them to show how thechallenge of growth that Wal-Mart faces todaymay well be wicked.

The problem involves many stakeholderswith different values and priorities. As Wal-Mart tries to grow faster, numerous stakehold-ers are watching nervously: employees andtrade unions; shareholders, investors, andcreditors; suppliers and joint venture partners;the governments of the U.S. and other nationswhere the retailer operates; and customers.That’s not all; many nongovernmental organi-zations, particularly in countries where the re-tailer buys products, are closely monitoring it.Wal-Mart’s stakeholders have different inter-ests, and not all of them share the company’sgoals. Each group possesses the capacity, invarying degrees, to influence the company’schoices and results. That wasn’t the case in1962, when Sam Walton set up his first store inRogers, Arkansas.

The issue’s roots are complex and tangled.Wal-Mart’s slowing growth in the U.S. is a con-sequence of, among other things, a saturatedmarket, its customers’ limited disposable in-comes, and intense competition from rivalssuch as Target and Costco. Wal-Mart also facesresistance to imports, criticism about thewages and benefits it offers employees, andcharges that illegal aliens work in its stores. Allthis has generated unfavorable publicity andstrengthened people’s opposition to Wal-Mart’sopening stores in urban areas. Compoundingthe challenge, some of the company’s advan-tages have turned into disadvantages. For in-stance, Wal-Mart’s large market share in someproduct categories makes it tough to growsame-store sales rapidly. Its low-cost sourcingpractices have rendered it vulnerable to thehealth and safety concerns that surroundproducts made in China. Its supply chain

John C. Camillus

([email protected]) is the Donald R. Beall Professor of Stra-tegic Management at the University of Pittsburgh’s Joseph M. Katz Graduate School of Business.

This document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact [email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

Strategy as a Wicked Problem

harvard business review • may 2008 page 3

expertise doesn’t help in the case of fashionand organic products, and its low-price imagehurts its ability to sell upscale products. More-over, Wal-Mart’s deep roots in rural Americaare of little use in overseas markets.

The problem is difficult to come to gripswith and changes with every attempt to ad-dress it. Wal-Mart has several options. It cantry to boost revenues and profits by increasingsales from existing stores or raising prices, byexpanding into urban markets in the U.S., byentering emerging economies, by diversifyinginto upscale product lines and creating newstore brands, by forecasting better, or by cut-ting suppliers’ margins. These strategies de-mand different capabilities, are risky, andsometimes conflict with one another.

Consider two of the least complex optionsbefore Wal-Mart. It could boost profits by hik-ing prices, but until now, everyday low priceshave helped the company fend off rivals. Ifconsumers resist higher prices, the retailer’ssales will fall and profits will drop. To preventthat, Wal-Mart must first modify its value prop-osition, stock some upscale products, and de-velop a brand persona that warrants higherprices—challenges that have little to do with

boosting profits immediately. Alternatively,Wal-Mart could enter a fast-growing emergingmarket, as it has done in India. It has found thegoing tough there, however. In India, locallaws don’t allow foreign companies to operatemultibrand retail outlets, so Wal-Mart has hadto develop a special business model: cash-and-carry wholesale stores for local retailers. Be-sides being unfamiliar, the strategy containsthe nucleus of another problem. When India’slaws change and allow Wal-Mart to sell toconsumers, it will have to compete with theretailers it supplies.

The challenge has no precedent. The twostrategies we just discussed pose completelynew challenges for the company. For instance,Wal-Mart would have to alter its brandimage—for the first time in its 46-year history—to justify higher prices. Its recent foray intohigher-priced garments is an experiment anddoesn’t appear to have worked. Similarly,Wal-Mart’s India strategy differs from theM&A strategy it has used to enter other devel-oping countries. Wal-Mart is a novice at man-aging partnerships, but it has had to team upwith an Indian conglomerate, Bharti Enter-prises. The group, whose primary business is

The 10 Properties of Wicked Problems

In 1973, Horst W.J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber, two Berkeley professors, published an article in

Policy Sciences

introducing the notion of “wicked” social problems. The arti-cle, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” named 10 properties that distin-guished wicked problems from hard but ordi-nary problems.

1. There is no definitive formulation of a

wicked problem.

It’s not possible to write a well-defined statement of the problem, as can be done with an ordinary problem.

2. Wicked problems have no stopping

rule.

You can tell when you’ve reached a so-lution with an ordinary problem. With a wicked problem, the search for solutions never stops.

3. Solutions to wicked problems are not

true or false, but good or bad.

Ordinary problems have solutions that can be objec-tively evaluated as right or wrong. Choosing a solution to a wicked problem is largely a matter of judgment.

4. There is no immediate and no ulti-

mate test of a solution to a wicked prob-

lem.

It’s possible to determine right away if a solution to an ordinary problem is work-ing. But solutions to wicked problems generate unexpected consequences over time, making it difficult to measure their effectiveness.

5. Every solution to a wicked problem is a

“one-shot” operation; because there is no

opportunity to learn by trial and error,

every attempt counts significantly.

Solu-tions to ordinary problems can be easily tried and abandoned. With wicked problems, every implemented solution has consequences that cannot be undone.

6. Wicked problems do not have an ex-

haustively describable set of potential solu-

tions, nor is there a well-described set of

permissible operations that may be incor-

porated into the plan.

Ordinary problems come with a limited set of potential solutions, by contrast.

7. Every wicked problem is essentially

unique.

An ordinary problem belongs to a class of similar problems that are all solved in the same way. A wicked problem is substan-tially without precedent; experience does not help you address it.

8. Every wicked problem can be consid-

ered to be a symptom of another problem.

While an ordinary problem is self-contained, a wicked problem is entwined with other prob-lems. However, those problems don’t have one root cause.

9. The existence of a discrepancy repre-

senting a wicked problem can be explained

in numerous ways.

A wicked problem in-volves many stakeholders, who all will have different ideas about what the problem really is and what its causes are.

10. The planner has no right to be wrong.

Problem solvers dealing with a wicked issue are held liable for the consequences of any ac-tions they take, because those actions will have such a large impact and are hard to justify.

This document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact [email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

Strategy as a Wicked Problem

harvard business review • may 2008 page 4

telecommunications, wants to tap Wal-Mart’sexpertise to set up a supply chain to get Indianproduce onto Western tables! Wal-Mart willhave to work with India’s bureaucracy to buildthe infrastructure that will support its opera-tions, but in the past, dealing with govern-ments hasn’t been the company’s strong suit.

There’s nothing to indicate the rightanswer to the problem. In Wal-Mart’s case,going upmarket could boost profits, but it isn’teasy for a discount chain to develop a relation-ship with higher-income shoppers. Moreover,the retailer cannot ignore its existing consumers,who shop at Wal-Mart for inexpensive prod-ucts. How much of a focus on higher-marginproducts and higher-income customers isappropriate? The company has no way ofknowing that in the beginning. In like vein,Wal-Mart’s India strategy may be an effectiveway to enter a number of rapidly developingeconomies. However, the company will losesome of its competitive advantage when itshares expertise with local partners. What’sthe optimal level of knowledge transfer?That’s impossible to estimate; Wal-Mart willfind out only after it has shared best practices—and possibly created new rivals.

Growth is a hard problem for many compa-nies, but it may not always be wicked. In Wal-Mart’s case, as we have just seen, the challengebears all the signs of wickedness.

Managing the Wickedness of Strategy

It’s impossible to find solutions to wicked strat-egy problems, but companies can learn tocope with them. In accordance with Occam’srazor, the simplest techniques are often the best.

Involve stakeholders, document opinions,and communicate. Companies can managestrategy’s wickedness not by being moresystematic but by using social-planning pro-cesses. They should organize brainstormingsessions to identify the various aspects of awicked problem; hold retreats to encourageexecutives and stakeholders to share theirperspectives; run focus groups to better under-stand stakeholders’ viewpoints; involve stake-holders in developing future scenarios; andorganize design charrettes to develop and gainacceptance for possible strategies. The aimshould be to create a shared understanding ofthe problem and foster a joint commitment topossible ways of resolving it. Not everyone will

agree on what the problem is, but stakehold-ers should be able to understand one another’spositions well enough to discuss differentinterpretations of the problem and work to-gether to tackle it.

Companies must go beyond obtaining factsand opinions from stakeholders; they shouldinvolve them in finding ways to manage theproblem. Getting a variety of opinions helpscompanies develop novel perspectives. It alsostrengthens collective intelligence, whichcounteracts groupthink and cognitive bias andenables groups to tackle problems more effec-tively than individuals, as Tom Atlee, thefounder and codirector of the Co-IntelligenceInstitute, and Howard Bloom, a visitingscholar at New York University, have pointedout. Involving more stakeholders makes theplanning process more complex, but it also ex-pands the potential for creativity. Buy-in is animportant result; companies should look notonly for countermeasures but also for stake-holders to get on board with some of them.

Companies believe that shareholders andcustomers are important stakeholders, but em-ployees are even more crucial. Their tacitknowledge and commitment often help enter-prises develop innovative strategies. MerrillLynch Credit Corporation, for example, placesa great deal of emphasis on semistructured so-cial processes, frequently organizing socialevents and encouraging employees to interactwith one another. Everyone lunches in thecompany cafeteria, which allows employees tomix with senior executives routinely. A com-pany intranet supports virtual social interac-tions such as blog-based discussions.

It may seem trivial, but documenting stake-holders’ assumptions, ideas, and concernson an ongoing basis is important. It helpsenterprises understand stakeholders’ hiddenassumptions and gauge the effectiveness ofthe actions they have taken. Documents alsohelp executives communicate ideas, which isessential if plans are to become reality.

All planning processes are, at their core, ve-hicles for communication with employees atall levels and between business units. Thisis particularly true of processes that tacklewicked issues. Smart companies emphasizesuch communication. At John Deere, corporateplanners say that the quality of senior execu-tives’ communications with divisions is themost important indicator of the effectiveness

This document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact [email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

Strategy as a Wicked Problem

harvard business review • may 2008 page 5

of strategy planning. Whirlpool believes thateven the “janitor on the third shift” should befamiliar with the company’s strategic goals. Soassembly lines at Whirlpool shut down on aregular basis to enable managers and workersto discuss the progress of plans. At Shell a glo-bal electronic network, organized into forumswith moderators, allows hundreds of managersand planners to discuss planning issues. AtMerrill Lynch Credit Corporation, the corpo-rate planners’ three most important rules foreffective planning are simple: “One, com-municate! Two, communicate! And three,communicate!”

The documentation process is a good wayto generate new ideas. It needn’t be confinedto recording decisions already reached; somecompanies have been creative in using the pro-cess to communicate the nature of the prob-lems they face. In 2002 SAE International, anorganization that sets standards and providestraining in the automobile, aerospace, andcommercial vehicle industries, was looking fornew strategies. It commissioned a case studyon its situation and then invited 30 senior exec-utives with reputations for creative thinking todiscuss the case with its top managers. SAErecorded the ideas that emerged during thesession and has implemented several of them.Without the case study that captured the orga-nization’s dilemma, the brainstorming mightnot have been productive.

Define the corporate identity. While a com-pany dealing with a wicked problem has to ex-periment with many strategies, it must staytrue to a sense of purpose. Mission statementsare the foundations of strategy, but in a fast-changing world, companies change their “con-cept of business,” “scope of activities,” or“statement of purpose” more often than theyused to. A company’s identity, which serves asa touchstone against which it can evaluate itschoices, is often a more enduring statement ofstrategic intent.

An organization’s identity, like that of an in-dividual, comprises the following:

• Values. What is fundamentally importantto the company?

• Competencies. What does the company dobetter than others do?

• Aspirations. How does the company envi-sion and measure success?

An identity provides executives with direc-tion and focuses attention on opportunities

and threats. For instance, in August 2007,Campbell Soup decided it would sell offthe Godiva business. The company didn’tbase the decision on financial performance;Godiva is a superpremium chocolate brandand a profitable business. Trouble is, Camp-bell’s values, competencies, and aspirationsfocus on nutrition and simplicity—andGodiva chocolates don’t fit in with thatself-image. “Although the premium choco-late category is experiencing strong growthand Godiva is well-positioned for the future,the premium chocolate business does not fitwith Campbell’s focus on simple meals,” ex-plained Douglas R. Conant, Campbell Soup’sCEO, while announcing the decision. InDecember 2007, the company reached anagreement to sell Godiva to Yildiz Holding,which owns the Turkish company ÜlkerGroup, for $850 million. By relying on itsidentity, rather than on financial projections,Campbell made the decision to sell Godivaquickly and painlessly.

Focus on action. In a world of Newtonianorder, where there is a clear relationship be-tween cause and effect, companies can judgewhat strategies they want to pursue. In awicked world of complex and shadowy possi-bilities, enterprises don’t know if their strategiesare appropriate or what those strategies’consequences might be. They should thereforeabandon the convention of thinking throughall their options before choosing a single one,and experiment with a number of strategiesthat are feasible even if they are unsure ofthe implications.

To pick a starting point, executives can bor-row a leaf from policy makers. Bureaucratsfocus on the few actions they will be able totake rather than the myriad options beforethem, Yale University’s Charles Lindblompointed out in 1959. Doing so enables policymakers to analyze options quickly and makedecisions that meet the goals of several constit-uents. Calling it the science of muddlingthrough, Lindblom argued that over time, gov-ernments will make progress by constantlymaking small policy changes. In a similar way,companies can formulate strategies that willdeliver results in various scenarios—I call theserobust actions—and use Pareto analysis toprioritize a small number of them that willproduce the most impact. That’s what PPG In-dustries does—as shown in the exhibit below,

This document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact [email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

Strategy as a Wicked Problem

harvard business review • may 2008 page 6

“PPG’s Framework for Responding to WickedIssues,” and described later in this article.

However, even executives willing to embarkon a number of robust actions often becomeindecisive when they realize that every re-sponse to a wicked issue will alter the problemthe company faces and necessitate anotherchange in strategy. They keep analyzing theissue rather than doing something about it.They would do better to try out some strategyas a starting point; the consequences will givethem a better handle on the real problem theyface. So, to tackle wicked problems, smart com-panies conduct experiments, launch innovativepilot programs, test prototypes—and make

mistakes from which they can learn. Compa-nies like GE and Fujitsu encourage risk takingand celebrate thoughtfully implemented initia-tives even if they turn out to be business fail-ures. These companies believe that unexpectedand even unsatisfactory results contribute toorganizational learning.

Adopt a “feed-forward” orientation. Com-panies design planning systems to work basedon feedback; they compare results with plansand take corrective actions. Though it’s a pow-erful source of learning, feedback has limitedrelevance in a wicked context. Feedback al-lows enterprises to refine fundamentallysound strategies; wicked problems require

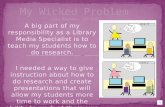

PPG’s Framework for Responding to Wicked Issues

PPG Industries develops strategies after seeking and documenting stakeholders’ assumptions, preferences, and alternate views. It evaluates the appropriateness of the strategies it draws up against its statement of identity and continually scans the environment and tests assumptions to see if it needs to change course. The assessment of possible scenarios helps PPG formulate new options, and its managers apply Pareto analysis to identify a small number of actions that are likely to have a large impact.

feed back findings

envision the future

test appropriateness

Continuously scan environment

Articulate identity

■ Values ■ Competencies ■ Aspirations

formulate options

ApplyPareto

analysis

choose priorities

evaluate options

Conductscenarioanalysis

validateassumptions

modify strategy

modifystrategy

Develop and refine strategyby documenting stakeholders’ assumptions, preferences, and views

This document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact [email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

Strategy as a Wicked Problem

harvard business review • may 2008 page 7

executives to come up with novel ones. Feed-back helps people learn from the past; wickedproblems arise from unanticipated, uncertain,and unclear futures. Feedback helps peoplelearn in contexts such as the movie GroundhogDay, where the protagonist (Phil Connors)encounters the same set of circumstancesevery day, which enables him to perfect hisresponses over time. Wicked problems arisein circumstances such as those in the TV se-ries Quantum Leap, where the protagonist(Sam Beckett) finds himself in an unfamiliartime and place in each episode. Compre-hending the challenge he faces is itself theinitial problem.

To develop a feed-forward orientation as acomplement to the feedback practices theycurrently use, corporations must learn to envi-sion the future. In this variation of scenarioplanning, enterprises should describe the set ofexternal and internal circumstances that theywould like to see in the next 10, 20, or 50 years.This will open executives’ minds to the rangeand unpredictability of possibilities that the fu-ture may bring. Enterprises must then pursuestrategies that will increase the likelihood ofthose circumstances’ becoming reality. For in-stance, in the early 1980s, Alcoa envisioned afuture in which aluminum, rather than steel,would be automobile manufacturers’ metal ofchoice. In 1982, it allied with Audi to make thathappen. By the mid-1990s, the collaborationbetween the two companies had produced thebreakthrough Audi Space Frame, an alumi-num structure into which car body panels areintegrated so that they can perform a load-bearing function, which later became theindustry norm.

Wicked strategy issues don’t occur accord-ing to a timetable. Companies must constantlyscan the environment for weak signals ratherthan conduct periodic analyses of the businesslandscape. (See, for example, George S. Dayand Paul J.H. Schoemaker, “Scanning the Pe-riphery,” HBR November 2005.) It’s increas-ingly difficult to identify the boundaries of thearenas companies should watch. Changes inone industry or segment often affect compa-nies in others. For instance, who could haveimagined that changes brought about by thecomputer industry and the internet would af-fect the music industry so radically? Businessesshould scan sources of regulatory and tech-nological change in addition to monitoring

suppliers, competitors, potential entrants, andcustomers all over the world.

To forge effective approaches to wicked is-sues, executives must explore and monitor theassumptions behind their strategies. One wayof doing that is through discovery-driven plan-ning, where executives list the assumptions un-derlying the revenues and income they expectand test the validity of each premise. (See RitaGunther McGrath and Ian C. MacMillan,“Discovery-Driven Planning,” HBR July–August1995.) By sharing those assumptions, execu-tives can better align decision making through-out the organization.

Case Study: How PPG Battles Wickedness

PPG Industries’ strategic-planning practicesconstitute an effective response to wickedstrategy issues. The company, founded over acentury ago as a plate-glass manufacturer,makes chemicals and coatings too. With 125manufacturing facilities and partners in 25countries, PPG is a global player. Although itoperates in mature industries, the companyhas paid dividends every year since 1899—andhas maintained or increased dividends everyyear since 1972.

PPG first became aware of strategy’s wicked-ness in the late 1980s. Two missteps taught thecompany that diversification, be it into otherindustries or countries, is fraught with peril.Realizing that growth was slowing down, PPGexpanded its portfolio by acquiring medicalelectronics businesses from Honeywell and Lit-ton Industries in 1986 and from Allegheny In-ternational in 1987. However, the biomedicalindustry’s volatility and the units’ focus on cus-tomization didn’t fit the company’s compe-tence in low-cost, standardized production.Seven years later, PPG had to sell the division.The company’s other wicked challenge wasChina, where PPG’s initial focus was glass. Al-though it entered the market in 1987, PPG’soperations there were unprofitable until themid-1990s. The company then realized that itwould have to focus on coatings if it wanted tomake money in China.

These experiences changed the company’sapproach to planning strategy in three ways.First, in the mid-1980s, PPG revisited its mis-sion and articulated its identity in a documentcalled the Blueprint. The company stated thatit valued steady growth that met stakeholders’

This document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact [email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

Strategy as a Wicked Problem

harvard business review • may 2008 page 8

expectations; that it believed it was capable ofachieving high levels of operational efficiencyand using technology to develop innovations;and that it aspired to remain a profitable glo-bal player in all its businesses. Since then,PPG’s identity has been more or less un-changed. The 2006 iteration mentioned thesame core values and expressed a similar aspi-ration, with some modification in PPG’s goals.It also identified a richer set of competencies.Although PPG’s business portfolio haschanged, with coatings assuming primacy overglass in the 2000s, its identity has endured.

Second, PPG’s plans have become living doc-uments. They change frequently as the resultof technology reviews conducted by teams ofsenior and R&D executives; examinations ofthe business portfolio at the corporate level;brainstorming sessions that promote freshthinking by executives and employees; and

scanning of markets, technologies, and regu-latory issues by its three business units. PPG’sexecutives say that the planning process is con-tinuous, with the company constantly identify-ing problems and developing responses. Thecompany often draws up possible scenariosand works to create the future it desires. Theexhibit “PPG’s Alternate Futures” shows the fu-ture scenarios it drew up in 2004 after makingassumptions about two key variables: the costof the energy required for its manufacturingoperations and the extent of the opportunityto compete globally through differentiation.When PPG’s senior executives studied the sce-narios, they identified three kinds of actionsthat would deliver results in all four cases:

• Emphasize operational excellence throughcost efficiency (using lean manufacturing tech-niques and improved logistics) and quality(through Six Sigma programs).

• Enhance differentiation through technology-based innovations and new services that willmeet customer needs.

• Generate cash to support strategic initia-tives, to manage the portfolio of businesses,and to pay dividends.

Using Pareto analysis, PPG then identifiedthe 20% of strategy options that would have80% of the impact that could be derived frompursuing all of them. Developing a technol-ogy that would reduce the minimum efficientscale of its manufacturing facilities, execu-tives felt, would be a key action. Reducing thescale would allow PPG to respond to a rangeof issues:

• It would enable the company to expandinto countries and regions that lacked thedemand to support the scale of its currenttechnology.

• It would reduce warehousing and in-ventory levels as well as improve deliverytimes by allowing factories to be located closerto customers.

• It would use less energy in each locationand disperse energy consumption.

• It would require lower levels of investmentby the company.

• The efforts to reduce the scale would mostlikely give rise to newer, more efficient, andmore reliable technologies.

Not surprisingly, PPG has invested heavilyin developing such a technology.

PPG’s approach to strategy is comprehen-sive, with the various techniques the company

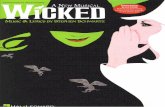

PPG’s Alternate Futures

To tackle wicked strategy problems, PPG Industries tries to envisage different futures it might face. In 2004, it drew up four possible scenarios by combining the biggest opportunity—namely, entering emerging markets—and the biggest challenge, the cost of energy, it would face in the next 10 years.

This allowed PPG to identify three strategies that will deliver results in any of the four circumstances:

•

pursue operational excellence by emphasizing cost efficiency and quality;

•

enhance differentiation through technology and service innovation; and

•

generate cash.

Co

st o

f en

erg

y

mo

der

ate

and

sta

ble

Turn up the heat

Success will depend on capturing share with new products

Promised land

Success will require having the resources to pursue new opportunities

hig

h a

nd

vo

lati

le Winter of discontent

Success will demand a change in strategic direction

Cool the fire

Success will require more-efficient processes

weak and slow strong and fast

Opportunity for differentiation and growth in emerging markets

This document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact [email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

Strategy as a Wicked Problem

harvard business review • may 2008 page 9

uses reinforcing one another and enabling it tobeat back the wicked challenges it faces. Partlyas a consequence, even though PPG operatesin highly competitive markets, it reported reve-nues of $11.2 billion in 2007—a 13% increaseover 2006—and net income of $834 million,compared with $711 million in 2006.

• • •

When confronting frustrating problems, anenterprise would do well to recognize thatthey may be wicked. Moving from denial to ac-ceptance is important; otherwise, companieswill continue to use conventional processesand never effectively address their strategy

issues. Moreover, when executives look afreshat the problems they face, they shouldn’t beshocked to find so many wicked ones. “Theeasy problems have been solved. Designingsystems is difficult because there is no consen-sus on what the problems are, let alone how tosolve them,” wrote Mary Poppendieck, thelean-software development guru, in 2002.That’s true for many businesses today.

Reprint R0805G

To order, see the next pageor call 800-988-0886 or 617-783-7500or go to www.hbr.org

This document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact [email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

Further Reading

To Order

For

Harvard Business Review

reprints and subscriptions, call 800-988-0886 or 617-783-7500. Go to www.hbr.org

For customized and quantity orders of Harvard Business Review article reprints, call 617-783-7626, or [email protected]

page 10

The

Harvard Business Review

Paperback Series

Here are the landmark ideas—both contemporary and classic—that have established Harvard Business Review as required reading for businesspeople around the globe. Each paperback includes eight of the leading articles on a particular business topic. The series includes over thirty titles, including the following best-sellers:

Harvard Business Review on Brand Management

Product no. 1445

Harvard Business Review on Change

Product no. 8842

Harvard Business Review on Leadership

Product no. 8834

Harvard Business Review on Managing People

Product no. 9075

Harvard Business Review on Measuring Corporate Performance

Product no. 8826

For a complete list of the

Harvard Business Review paperback series, go to www.hbr.org.

This document is authorized for use only by Bengt Skarstam ([email protected]). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact [email protected] or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.