WHY DEVELOPING COUNTRIES FAIL TO DEVELOP - …978-1-349-21343-6/1.pdf · Why developing countries...

Transcript of WHY DEVELOPING COUNTRIES FAIL TO DEVELOP - …978-1-349-21343-6/1.pdf · Why developing countries...

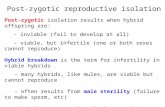

WHY DEVELOPING COUNTRIES FAIL TO DEVELOP

International Economic Framework and Economic Subordination

Why Developing Countries Fail to Develop

International Economic Framework and Economic Subordination

Purushottam Narayan Mathur Emeritus Professor University College of Wales, Aberystwyth

Preface by Wassily Leontief New York University

Foreword by Y oshimasa Kurabayashi Hitotsubashi University

Palgrave Macmillan

ISBN 978-1-349-21345-0 ISBN 978-1-349-21343-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-21343-6

© Purushottam Narayan Mathur, 1991 Preface© Wassily Leontief, 1991 Foreword © Yoshimasa Kurabavashi. 1991 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1991 978-0-333-47634-5

All rights reserved. For information, write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010

First published in the United States of America in 1991

ISBN 978-0-312-05329-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mathur, P. N. (Purushottam Narayan), 1925-Why developing countries fail to develop/Purushottam Narayan Mathur. p. em. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-312-05329-1 1. Developing countries-Dependency on foreign countries. 2. Developing countries-Economic policy. 3. Developing countries-Economic conditions. 4. International economic relations. I. Title. HC59.7.M348 1991 338.9'009172' 4--dc20 90-44836

CIP

To my grandfather

B. Brij Behari Mathur

who stopped the cultivation of the cash crop (Indigo), realising it as one of the causes of famine of 1890s and started informal rationing as well as mango tree plantation work in the village

And To my dear wife

Mrs Sushila Rani Mathur who not only made this book possible with constant help and encouragement, but also freed the author from the other chores of daily living

Contents

List of Figures xiv

List of Tables xv

Acknowledgements xvi

Preface by W assily Leontief xvii

Foreword by Yoshimasa Kurabayashi xviii

Introduction 1

Non-applicability of received economic doctrines 1 Towards a new perspective 2 The international framework and the problem of price relatives 3 Failure of development 4 Structure of the book 4

PART I THE CENTRAL ARGUMENT

1 The Development Dilemma 9

Collapse of development in the 1980s: an unexplained phenomenon 9 Different paradigms in economic analysis 10 The patterns of development 12 Wage levels for developing countries and loan repayment 12 Price structure in low-wage countries 13 Two groups of developing countries 15 Macroeconomics of developing countries 17 Nominal wage rates in developing countries 26 The international economic order as an impediment to development 29

VII

viii Contents

PART II DEVELOPMENT THEORY AND EXPERIENCE

2 Metaeconomics 33

Economic environment and factors of production 33 Formalisation of the production process 35 Micro management and microeconomic problems 38 The macroeconomic problem 41 International constraints or worldwide macro limitations 43 Recapitulation 44

3 A Synoptic View of Economic Historic States in Theoretical Perspective: Before the Industrial Revolution 46

An idealised history of economic progress 46 Tribal self-sufficient economy: no surplus 47 Labour as the scarce factor: slave economy 47 Land as the scarce factor: feudal economy 49 International trade as a factor: mercantilism 49 Colonial economy 51 Subject economy and economic drain 53 Imperialism and structural change 55 Social theories of economic growth 58 Innovation and the process of growth 59

4 A Synoptic View of the Industrial Revolution in Theoretical Perspective 62

The basic character of the industrial revolution 62 Availability of risk capital 63 Cheap raw materials 66 The size of the market 68 The 'backwash' mechanism in developing countries 70 Institutions for industrialisation 71

5 Types of Developing Countries 77

Introduction 77 Classification of developing countries 79 Concluding remarks 86

Contents ix

PART ill AN INTERNATIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR NATIONAL ECONOMIES

6 Determination of International Commodity Prices 89

Introduction 89 Commodity price determination in international markets 91 Short-term price determination 92 Duties on commodity imports and exports 93 Long-term supply curve 94 Secular decline of long-term supply price 96 An illustration of the short-term supply curve 98 Idealised story of commodity supply curves after 1945 100 Recapitulation 102

7 Commodity Price Shocks and World Economies 104

Introduction 104 Commodity prices and industrial production 105 Commodity prices and inflation 106 Strategy of monetary expansion 112 Transition to low commodity prices 113 Commodity prices and developing countries 114 Determination of exchange rates in developing countries 115 Changing wage levels in developing countries with changing commodity prices 117 Price structure with differing import requirements 120 Poverty as a necessary condition of export promotion? 121

8 Changing Export Income and the Developing Countries' Economy: A Diagrammatic Representation 123

Introduction 123 Labour-constrained economies with traditional techniques for producing wage goods 123 A diagrammatic representation of macro relations 125 Effects of export commodity price increases 125 Effects of decreases in commodity prices 127 Land-constrained developing countries with traditional techniques of foodgrain production 128 Developing countries with modem technology 130

X Contents

The development dilemma 132 The 'fallacy of composition' and the barrier to the increase of real wage rates in the long run 133

PART IV MACROECONOMICS OF DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

9 The Macroeconomics of Economic Subordination and Drain 139

Economic subordination and drain 139 The macroeconomics of a traditional land-scarce economy 140 The macroeconomics of a subject or indebted economy 141 The macroeconomics of land-scarce developing countries with a traditional pattern of trade 142 The macroeconomics of labour-constrained under-developed countries 144 Imperialism in new countries 147 The demographic myth 148

10 The Wage Goods Constraint for Employment and Development 151

Prices and availability of basic consumption goods 151 UN study of purchasing power parity 152 Semi-feasibility of importing wage goods in a developing country 153 Wage goods constraints for employment and development 154 Autonomous expenditure in a wage goods-constrained economy 157 Moving unemployment due to an unsustainable development effort 158 Effect on marketed surplus in a semi-monetised economy 159 Recapitulation 161

Contents xi

11 Violations of Macro Constraints and Inflation: Different Types of Demand-pull and Cost-push Inflations, with Indian Illustrations 162

Introduction 162 Classical demand-pull inflation 163 Wage cost-push inflation 164 The paradox of the Indian case 165 Constrained demand-pull inflation 165 The logic of cost-push inflation 166 Nominal interest rate-push inflation 168 Import-push inflation 169 Recapitulation 169 Indian experience of demand-pull inflation with foodgrains as the bottleneck 169 Characteristics of bottleneck-induced demand-pull inflation 173 Interest cost-push inflation in India after 1975--6 174 Concluding remarks 176 Mathematical appendix 177

PARTV THE MICROECONOMICS OF DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

12 The Role of Scarcity V aloe and Market Price 181

Economics as a relationship between ends and scarce means 181 Value of scarce means and general equilibrium system 182 Non-scarce factors of production and the difference between scarcity value and price 183 The classical equivalence of value and price 185 The neoclassical equality of scarcity value and price and its practical futility 187 Differences between scarcity values and prices as a rationale of commodity taxes and subsidies 189 Some uses of differences between value and price in economic policy 190

13 Implications of Adopting Modern Technology 196

Introduction 196

xii Contents

Methods of increasing agricultural productivity 197 Diminishing returns to fertiliser use 200 Fertiliser use in developing countries 203 Subsidies, etc. for adjusting price ratios 204 Technology transfer in industry: transfer of existing or almost obsolete rather than appropriate technology 204 Economic feasibility of technology transfer in industry 206 Cost of production in new industry 207 Technological layers and transfer of know-how 208 Wage sacrifice for manufacture for export: some indications 210 Some conditions for successful technology transfer 212

14 The Economics of Technology Transfer 214

Introduction 214 Lewis's model for the isolated development of the modem sector 214 Establishment of a modem sector through loans 216 Establishment of a partial modem sector 217 Implications of transfer of less efficient techniques 218 Conclusions 221

Appendix: Feasible Price Structure and the Range of its Variations. 223

PART VI STRATEGIES FOR DEVELOPMENT

15 The Role of Subsidies and Import Controls in Modernising Low-income Countries 229

Introduction 229 Development through judicious subsidies and taxes 231 The case of direct subsidies: Egypt 231 Indirect subsidisation: India 233 Limits to price adjustments for growth 238 Restraining overall industrial growth 239 Contours of the way forward 242

16 Partnership in Development? 244

The dilemma of an individual country's development: A recapitulation 244

Contents xiii

Some necessary conditions for development 246 A South-South common market 248 Multilateral Project-based Partnership (MPP) 249 Multilateral Vertically Integrated Commodity Development Projects (MVICDP) 251 Shadow price ratios between inputs and outputs 255 The long-run effects of MPP 256

17 Foreign Exchange-constrained Developing Economies 258

Determination of production, etc. 258 Effect of the commodity price crash in the 1980s on Latin America 259 Import substitution industrialisation (lSI) of Latin America and the Caribbean 262 Productivity in import substitution industries 264 Steps forward 265

PART VII APPENDIX: TOWARDS AN INTERNATIONAL TRADE THEORY WITHOUT SAY'S LAW

18 Why International Price Structures Differ 273

Introduction 273 The conventional explanation: international productivity differences 273 Difficulties with the conventional explanation 274 Impetus to exports for developing countries and traded goods 276 Wage rate determination in commodity exporting countries 277 The level and structure of prices 277 Implications of changes in commodity price for internal prices 279 The production possibility frontier 279 Conclusion 280

Notes 282 Bibliography 289 Index 294

List of Figures

1.1 Lewis's development model: diagrammatic representation 19

6.1 Short-term commodity supply-demand curve 93 6.2 Short-term commodity supply-demand curve:

movement over time 95 8.1 Macroeconomics of labour-constrained developing

countries 126 8.2 Macroeconomics of labour-constrained developing

countries: with increasing commodity prices 127 8.3 Medium-term macroeconomics with decreasing

commodity prices 129 8.4 Macroeconomic representation of foreign

exchange-constrained economies 131 8.5 Changes in wage rates with increasing exports 134

13.1 Net returns on fertilisers 201

xiv

List of Tables

1.1 Average price indices for groups of countries (1975) 14 1.2 Average industrial wage in developing countries

(1985) 27 7.1 Industrial production in some developed countries

(1973-85) 105 7.2 Primary factor contents in final demand in the UK 110 7.3 Inflation, manufacturing production and factor

returns in the UK 111 7.4 Movement of relative wages in some countries 118 7.5 Real wages and terms of trade in the Philippines 119 9.1 Population in relation to arable land in some

countries 149 10.1 Prices of some consumer goods in developing

countries 153 11.1 Different types of inflation 170 11.2 Foodgrain and wholesale price indices for India

(1955-6 to 1981-2) 171 15.1 Average manufacturing wages in Egypt 232 15.2 Price, cost and prices of foodgrains in Egypt 232 15.3 Food subsidies in Egypt 232 17.1 Per capita GDP, investment and wages in America 261 18.1 Average price indices for groups of countries (1975) 275

XV

Acknowledgements

The ideas contained here have been developed in book form at the instigation of Professor I.F. Pearce, who encouraged the author to collect the various threads of his ideas into this volume; the author is grateful to him for his continuous help and encouragement. Part of the text was reproduced in University College London, Discussion papers in Economics.

Quite a few colleagues have also helped me at various stages. It is not possible to acknowledge all of them by name, but I would like to mention in particular Messrs David Law, Michael Cain, and Nicholas Perdikis, all my colleagues at the University College of Wales, at Aberystwyth. Dr M. Mahdi, post-doctoral fellow at University College of London, and Dr Mushtaq Ahmed, Associate Professor at University of Multan in Pakistan.

Parts of the text were delivered at seminars at various research institutions, and I am grateful to the participants in these for their comments. Prominent among these were the University of Puerto Rico, at San Juan and MayaGuez Campuses; the Government Development Bank, Puerto Rico; the ESRC/Development Study Group, United Kingdom; North-East Hill University, Shillong, India; Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi; the Institute of Growth, Delhi; the University of Bombay; the Institute of Social Sciences, Ahmedabad; the Institute of Social and Economic Research, Trivandrum; the Maharashtra Association for Cultivation of Sciences, Poona; the University of Baroda, Baroda; the 1986 Tokyo Conference of the World University. Also discussions with Dr M. AL Eigailly and Dr Y. M. Sulaiman of the UN Economic Commission for Africa during the author's consultancy with UNECA were very helpful. I am also obliged to Prof Y oshimasa Kurabayashi for writing such a perceptive foreword.

I am particularly beholden to Nobel Laureate Professor Wassily Leontief, whose theoretical point of view was an inspiration for the development of the ideas expressed in this book. He has been a constant support in my long quest for understanding, the sinews of the workings of the economic system. He was also kind enough to write a few lines for the preface.

P.N.MATHUR

XVl

Preface

Forty-five years ago Professor Arthur Lewis made a path-breaking contribution to the understanding of the less developed economies that later earned him a Noble prize.

Mathur - who also comes from a less developed country, India -while teaching in England has centred his research on the fundamental analytical study of underdevelopment in the third world.

His conclusions presented in this volume deserve as much attention as Professor Lewis's observations attracted half a century ago.

WASSIL Y LEONTIEF

xvii

Foreword

In this volume Professor Mathur develops a system of equations which enables one to determine the internal price structure of goods and services for a given level of value added by industry in a country on the basis of the Leontief type of input-output relations. It is shown by the system of equations that the wages in one country should be less than and the value of imported commodity more than those in the partner developed country to which the commodities are exported. It naturally follows from this theoretical framework that the goods having higher import content will be more than proportionately costly. Nontradable services are likely to contain a small portion of commodity input, so it is more inclined to be on the cheap side. In contrast, transport equipment, producers durables, etc., are likely to have large direct and indirect import content, and here they should be more than proportionately costly.

Based upon this theoretical framework and with the help of statistical evidence, the author observes that five groups of developing countries are distinguished. They are:

(a) labour-constrained dual economies, traditional sectors being almost self sufficient;

(b) land-constrained dual economies, traditional sectors being almost self-sufficient;

(c) foreign-exchange-constrained new economies, some sectors having international trade-dependent wage goods technology;

(d) sovereign entities working as locations for offshore assembly plant;

(e) oil exporters.

Those developing countries which fall into the category (a) are characterised as a dualism between a self-sufficient and traditional society and commercialised segments. It is notable to see in the dualism that commercialised segments hardly interact with their stagnant counterpart. The author observes that the illustration of the developing economies of category (a) seems to be sufficiently appropriate for explaining the characteristics of those developing economies in sub-Saharan Africa. By contrast, in the developing countries which belong to the category (b) it is not labour but the land which

xviii

Foreword xix

causes the bottleneck of production. It is implied by the constraint of land that, with the current technique of production, agricultural production is not sufficient to reach the full employment of the whole labour force. In such circumstances, the only way to move towards better standards of living for the people is to increase land productivity. However, the increase of agricultural productivity requires the application of fertilisers and other chemicals to crops and the extensive use of more advanced agricultural instruments and machinery. Thus, it naturally follows that the supply price of wage goods is greatly dependent on international prices of the required imports. The rise of export prices which results from increasing the supply of wage goods tends to reduce the exports and this becomes a major bottleneck for the development of those countries which are classified as this type. The author suggests that some big developing countries like India and Pakistan might fall into this category.

Category (c) is essentially directed towards identifying former colonial economies of Latin America. As a result of historical development in these economies, they are crucially dependent on the imports of intermediate inputs. Any lack of foreign exchange will immediately lead to a shortage of imported intermediate goods. This will force the agriculture sector in the economies to leave the land either uncultivated or starved of the necessary inputs, thus resulting in the decline of economic activity. It is most likely with the wide fluctuations in the prices of internationally traded commodities that the foreign exchange availability of these economies will be changing fast from relative abundance to relative scarcity. Professor Mathur's new work provides a crystal-clear, sharp-edged and bright explanation of why most developing economies have been forced to stay at a standstill in the 1980s and suffer from the collapse of commodity prices in the developed countries. This volume is a valuable contribution to the discussion of a new international economic order which both economists and politicians in the world have sought in recent years.

YOSHIMASA KURABA YASHI