What is angiodysplasia?

-

Upload

dorothy-stewart -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

1

Transcript of What is angiodysplasia?

TISANGIODYSPLASIA?Often insidious,symptoms may bemistaken for canceror diverticulosis.

DOROTHY STEWART

Until recently, many episodes oflower gastrointestinal bleeding inpersons 65 and older were attributed to diverticular disease. Because of improved diagnostic techniques, specifically selective visceral angiography and colonoscopy,these episodes are being more frequently identified as angiodysplasia of the colon(l-6).

Approximately 10 years ago, J.S. Galdabini coined the term "angiodysplasia," meaning deformityof blood vessels, to describe the tangles of vessels. Angiodysplasia is anacquired disease in which bloodvessels, primarily those in the cecum and proximal descending colon, become dilated and tortuous.The lesions have been called hemangiomas, angiomas, arteriovenous malformation, and vascularectasias (dilation)(7).

Pathogenesis

One of the most widely acceptedexplanations of the pathogenesis of

180 Geriatric Nursing July/August 1986

angiodysplasia is proposed by S. J.Boley who claims that the "directcause of ectasias is chronic, partial,intermittent low grade obstructionof the submucosal veins especiallywhere they pierce the circular andlongitudinal muscle layers of thecolon"(l).

During muscular contraction anddistention of the bowel, pressureexerted against the submucosalveins causes transient and partialocclusion and, consequently, increasing pressure within the vein.Accumulated effects of such episodes repeated over time can precipitate the primary event in theangiodysplasia sequence-dilatation and deformity of the submucosal veins. The process is progressiveand eventually the venules and capillaries become dilated, and theprecapillary sphincters lose competency, thus permitting blood to beshunted through arteriovenouscommunications with subsequentdilatation of arterioles. Mucosaover severe advanced lesions is replaced by a maze of dilated anddistorted blood vessels(l).

Angiodysplasia is associated withseveral diseases commonly seen in

Dorothy Stewart, RN, MS, is assistant professor, Purdue University School of Nursing, West Lafayette, IN.

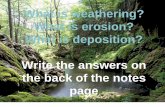

Illustration depicts the more common sitesfor angiodysplastic lesions of the colon.

the elderly: atherosclerosis, corQnary artery disease, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, andchronic obstructive pulmonary disease, in addition to diverticulosisand cancer of the cecum. Severalstudies indicate that approximately20-25% of persons with angiodysplasia have aortic stenosis. In aorticstenosis there is a drop in perfusionpressure secondary to decreasedleft ventricular output. Oxygen tension in the end-arteriolar supply ofthe superior mesenteric artery is

POSSIBLE NURSINGDIAGNOSES

FOR CUENTS WITHANGIODYSPLASIA

• Alterations in bowel elimination: constipation or diarrhea related toiron therapy

• Knowledge deficit related to home management regimen

AFTER SURGERY

• Knowledge deficit related to post-surgery management

• Potential alterations in bowel elimination: diarrhea related to bowelresection

• Actual or potential alterations in comfort; acute pain related tosurgical trauma

AFTER ASSESSMENT

• Activity intolerance related to fatigue secondary to chronic bloodloss

• Anxiety related to declining health status

• Anxiety related to unknown cause of rectal bleeding

• Potential for injury: falling, related to decreased cerebral perfusionsecondary to blood loss

• Ineffective coping related to persistent stress secondary to multi·pie bleeding episodes

• Fear related to invasive diagnostic procedure

• Fear related to outcome of diagnostic procedure

• Fluid volume deficit related to abnonnaJ blood loss

• Knowledge deficit related to angiodysplasia, invasive diagnosticprocedures, and treatment plan

• Self-care deficit related to fatigue

• Self-care deficit related to decrease in vision and motor abilities

• Powerlessness related to loss of privacy

• Grieving related to actual or perceived loss of independence

WITH IRON THERAPY

diminished. Early investigators ofangiodysplasia believed that chronic low perfusion pressure somehowcaused the vascular lesions. Recently investigators postulated thatcardiovascular changes do not contribute to the development of angiodysplasia. but do cause ischemicnecrosis of the endothelium thatcovers the ectatic lesions, therebyincreasing the chance of bleeding(I,4,7-11).

Assessment

Because the typical client withangiodysplasia is over 65 years ofage with several chronic pathological. conditions. early symptomsmay be overlooked, attributed toother causes, or dismissed as justanother sign of old age. Blood lossis the principal problem. If theblood loss has been slow but sufficient to produce chronic anemia.then symptoms of anemia such asfatigue, apathy, and depression willbe present. The client or those closeto him or her may notice a recentonset of mild confusion and disorientation. If the bleeding has beensubstantial (> lOOOcc) and has occurred over a short period of time.the client may have symptoms ofhypovolemia and shock requiringprompt intervention.

Complete and relevant information is more readily obtained whenthe nurse allows for the client'sdiminished physiological status.When immediate intervention isnot required and the client is notdiscomforted by waiting. appointments for diagnostic procedures onan outpatient basis can be scheduled over several days. Since thecondition of the client rather thanchronological age must be considered when planning care, take acareful health history. Includingsignificant others will help thenurse obtain additional and perhaps more accurate data if theclient is acutely ill or has impairedmemory. Particular attention isgivs:n to any antecedent bowelproblems and current bowel function. Some people are embarrassedby such detailed discussion of theirfeces and bowel habits. A direct,matter-of-fact approach will help

the person maintain dignity. Conducting the interview where theconversation will not be overheardwill respect the individual's right toprivacy.

Rectal bleeding does not necessarily occur in angiodysplasia. butif it is reported it is important forthe nurse to elicit an accurate description. Because angiodysplastic

lesions are small and initially involve venules and capillaries, theusual pattern of bleeding is a slowintermittent ooze. Continuous andmassive bleeding suggests arterialdiverticular hemorrhage or an advanced stage of angiodysplasia. Lesions in the cecum and proximal ascending colon are most common;the client will report blood in the

Geriatric Nursing July/August 1986181

stool as bright red, maroon, burgundy, or port wine in color. Melena, dark, pitchy stools, will be reported when blood from lesionshigher in the GI tract has been oxidized by intestinal enzymes.

Some clients are not able to describe bleeding accurately becauseof the intermittent nature of theepisodes or because they attributethe bleeding to other causes such ashemorrhoids. Testing for occultblood in the feces and a hematocritscreen may be done by the nurse toconfirm suspicions of blood loss,but normal results do not precludethe necessity of performing moreconclusive diagnostic procedures.

When blood loss is slow, symptoms of anemia may not be noticeduntil the client's hemoglobin isquite low, around 8 gm/dl. Fatigue, dyspnea, diaphoresis, andpalpitations associated with exertion are among the first to be noticed. Orthostatic dizziness (whichmay result in falls), sensitivity tocold, complaints of feeling "pinsand needles" in the fingers andtoes, tachycardia, weakness, andheadache may be reported whenthe blood loss is more severe.Symptoms of myocardial ischemiamay occur particularly in thoseclients who have co-existing cardiovascular or lung diseases. Bleedingcaused by angiodysplasia is painless, whereas bleeding accompanied by colic and local abdominalpain is typical of inflammatory andischemic processes.

After the health history has beencompiled, a complete physical examination and sigmoidoscopy aredone. A hemogram will help determine the nature and extent of bloodloss. Coagulation studies, includingtests to determine platelet function,are necessary because of the reported association with coagulopathies. Radionuclide imaging helpslocate the angiodysplastic lesionsand can detect bleeding when bloodloss is as slow as 0.1 ml/min. Afterradiopharmaceutical agents aregiven intravenously, a sequence ofimages is taken. Accumulation ofthe radiopharmaceutical agent willbe seen only if angiodysplastic lesions are bleeding(6,12).

182 Geriatric Nursing July/August 1986

Selective Mesenteric Angiography

Selective mesenteric angiography is a primary tool in definingangiodysplasia as a pathologicalentity. Complications that may result are allergic reactions to thecontrast media, embolism, infection, and hemorrhage. Before theprocedure, advise the client that heor she will feel a slight shock whenthe catheter is inserted into the artery and will experience a bad tastewhen the contrast media is injected. After the procedure, bedrest with the involved leg extendedand immobile is maintained for

Electrocoagulation oflesions through thecolonoscope avoidsh~zards of surgery.

several hours. The nurse will checkthe vital signs, dressing over the femoral artery, and peripheral pulsesin the ipsilateral lower extremity atfrequent intervals( 13).

Because bleeding from angiodysplastic lesions is usually low gradeand occurs in the venous phase,there is little or no extravasation ofcontrast media into the bowel. Forthis reason the radiologist mustlook for more subtle signs. Thepresence of dense slowly emptyingveins, a tangle of small vessels, andan early filling vein are criteria forestablishing the diagnosis of angiodysplasia(14).

Colonoscopy

Diagnosis may also be confirmedby colonoscopy. Biopsy and sometimes treatment of local lesions byelectrocoagulation techniques canbe done through the colonoscope.The nurse must be alert to the complications that may result from colonoscopy and electrocoagulation:perforation of the bowel, uncontrolled bleeding, cardiac and respiratory arrest from oversedation,and vagal stimulation. Thorough

preparation of the colon is necessary in order to visualize all of thecolonic mucosa and to eliminatethe hazard of explosion of the colonfrom accumulated gases (hydrogenand methane) when electrocauteryis used. Intravenous meperidineand diazepam are given immediately before insertion of the colonoscope. Angiodysplastic lesions areinconspicuous and difficult to identify. Those that are seen throughthe colonoscope are cherry red andusually between 5-10 mm in diameter(1,10,15).

Treatment

With the completion of assessment, medical and nursing diagnoses are made. (See box on preceeding page.) If bleeding is mild,anemia may be corrected with irontherapy. If there have been recurrent episodes of bleeding and/orbleeding has been severe, transfusions will be done before more aggressive treatment is tried.

The accepted treatment for angiodysplasia of the colon is surgicalremoval of the involved area. Whenthe lesions are confined to the cecum and the proximal colon, righthemicolectomy is rep<?rted to be curative in the majority of clients. Butas previously noted, angiodysplastic lesions are frequently inconspicuous and may occur throughoutthe colon. Recurrent colonic bleeding after the client has had a righthemicolectomy has been reportedto occur in as many as 23% ofcases. Subtotal colectomy is thetreatment of choice when there aremultiple lesions and bilateral coloninvolvement or when there is coexisting diverticular disease andmultiple polyps(1,4,16).

Reports of successful treatmentof angiodysplasia of the colon byelectrocoagulation through a colonoscope have been encouraging. Atreatment that avoids the hazardsand costs of major surgery is appealing, especially when the clientis elderly and has other serious systemic diseases. But because it isdifficult to identify and cauterizeall lesions, repeated electrocoagulation or surgical resection may berequired(9,1 0, I5).

I;'XPEGTE.D;CU.ENt ,QU:'teOMES'WllHJ1flON'tHE/1A'P~

.) HemogJ1UfiwiD: IfmI \W11hrllJnonnft~ nmrtitl.

.' StQ(l(Qld fj~1 ,nQI)li.a1anmufit and1..mfl$T~I~ngyJ.i • INO' avoTl1~l;)r(llCl)mp1foalTo.ml1 willi occur..

.'Client williparJICJ.pate, ill:da-1&'~mi at o.pfinmlJ if.aD.1J iQfi fUtlofionTng.I .1 GIJellt endj is.TgnIfic.ant' others: bav.a,a, cbancre (OJ:expTara, COfi'" '

cem$..i aUeni elldi iSlgnIDoJulJ] lothem lwiItde.scDbmIU\$lGl rOJ)i'lCepUII (it an:gjo.tJj$'prB~raidiet~rtm IfOUtlwEd,l):tQcetfilrsJ IOJfaRingJ ~roj)) ltteparJil[onstD.e}lsuteBi tel promote nonnal) lRlWeE e1i1nTl:ralJ'aDJ$YJ'Qpf11ms, that requTre»hYstcianlcm mRDcmilaati<tlma alld,damsof; lolrow·uj); care~

IIFiCEIt8I1J1G.E1W

• Inoision' wtrr !b:e~J ,normallYJ.•• Utifia~ 8.fid bowel 'elimina:tion,wlltbe ,re.e~fabtrshedi

• No avofdable' corriplicatloos WiD occur.-Olient willi ,peJticTpateln dalty !oare!at:oPtlmallev:efoff.unctiOJlIilD~

-onent afitfslgniftcantothers havee Cha-nceta, ,gxpl<1re 'CQIl~cems.

-Sefore, dlscbarQe~cJrentandsignIficant 'Olber$i will:·desclibe:diet to be :foJ(Qw.ed.need:f<1r adequate fJUJd! Iruak.s,c.araot ilt'iClslOfil'mm.«i1 'fa trnQrJ;ra.~~~Q1M~ !tt~t()lemledJ

m"Q!liCDlJons., d"os.age"IItne~ ,P_Ur'Pns.e.. aOdlst(f.eJeff.e,tt$!symploms: 1bat: Ire:qQJrephyslctan: iOl1nurse CpnlaCf)time ~ntl)(lQle~ fonOW;·JJPiCare.

Client TeachingRegardless of the treatment op

tion chosen, there is a need forclient teaching. Including significant others is a must. For the clientwho is in a retirement or nursingfacility, this will mean includingnursing and dietary personnel.

Lack of knowledge about a disease of which few people haveheard and whose name and presenting symptoms may be confusedwith cancer can increase fear andanxiety. Fear and anxiety mayheighten feelings of powerlessnessand dependency. Identifying andutilizing the client's existing support systems and constructive coping strategies will ease this uncomfortable state and help the client tobecome more receptive to learningabout the disease.

Supportive Therapies

For those persons whose anemiawill be treated medically, instructions about diet and iron replacement therapy will be necessary.The client must be told that ironpreparations will cause the feces tobe dark brown or black' in color.Since iron therapy will produce afalse positive result in tests for occult blood in the feces, it will bemore difficult to monitor furtherbleeding. The client can be instructed to be alert for other indications of bleeding and report anythat occur. Iron preparations contribute to constipation. Strainingwith defecation increases intraluminal pressure and may initiate anepisode of bleeding. Good bowelhygiene and the occasional use of amild laxative will prevent constipation problems.

A person who is anemic will absorb up to 30% of ingested iron differing from the 3-10% absorbed bynon-iron deficient persons. Oraliron preparations with ascorbicacid (Vitamin C or citrus juices)will increase the absorption of ironfrom the GI tract, while antacidscontaining magnesium trisilicate(Gaviscon tablets), tetracyclines,eggs, and milk will interfere. Oraliron preparations irritate GI mucosa and may cause nausea, vomiting,and diarrhea. For this reason, it

may be necessary to take iron withmeals or snacks even though it isbetter absorbed if taken when thestomach is empty. Dental stainingfrom liquid iron preparations canbe avoided by removing any dentalprosthesis, and diluting the iron solution and drinking it through astraw(I7).

Intramuscular injections of irondextran can be given to those persons unable to take oral iron preparations. Iron given in this manner isirritating to subcutaneous tissueand will stain the skin if allowed toleak back into superficial tissues.Superficial stains and irritation canbe prevented by injecting iron dextran into the larger gluteal muscles

using Z track technique and rotating sites(18). The nurse is alert tocomplaints of pain, staining, andinfl.ammation around injectionsites. The client is instructed to report these and any other adversereactions to iron therapy.

Blood replacement may be necessary for those clients with more severe blood losses. Multiple transfusions, which are often required, increase the possibility of complications. The nurse must be alert forhemolytic reactions. Early signsand symptoms may occur within tominutes after the transfusion hasbegun and include fever, chills,headache, chest tightness, low backpain, tachypnea, dyspnea, hypoten-

Geriatric Nursing July/August 1986 183

sion, and shock. If these occur, stopthe transfusion and follow agencyprotocol. After therapy, persistentlow hemoglobin and low grade fever will be indications of a delayedhemolytic reaction. The washingtechniques used to prepare leukocyte-poor and frozen-thawed red\Jlood cells remove many of the substances which cause hemolyticreactions.

The elderly person with arteriosclerotic vessel disease is at greaterrisk for developing fluid volumeoverload. Symptoms which may beevident as early as one hour afterthe transfusion has begun includeheadache, distended neck veins,rapid bounding pulse, dyspnea,anxiety, and moist breath sounds,especially in the. base of thelungs(l9). Fluid overload may beprevented by giving packed redblood cells instead of whole blood,administering furosemide (Lasix),and infusing a unit slowly overthree to four hours~

Surgical Treatmept

The care for the client who willbe treated surgically is not substantially different from care that allsurgical clients receive. Changesassociated with advanced age, particularly diminished cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, and musculoskeletal function, increase therisk for intraoperative and postoperative complications. The goal ofpreoperative care is to minimize therisks by ensuring that the client isin the best possible condition beforesurgery. The nurse assists with efforts to improve or stabilize coexisting clinical problems. Fluidand electrolyte imbalances will becorrected, and blood losses will bereplaced. Pulmonary toilet may berequired. The bowel will' becleansed, and antibiotics that areeffective against intestinal florawill be given two to three days before surgery in order to reduce therisk of wound infection. The decreased ability of the elderly to metabolize and eliminate drugs requires that anesthetic, analgesic,and antibiotic agents be carefullyselected. Monitoring blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels

184 Geriatric Nursing July/August 1986

is necessary for prompt detection ofrenal dysfunction.

Recognizing how the decreasedphysiological status of older clientsincreases the risks for postoperativecomplications will help the nurseplan interventions that will reducemorbidity. The elderly often have adecrease in vital capacity and lungcompliance and thicker mucus andsaliva. These changes plus the presence of a nasogastric tube and postoperative pain increase the need forthe nurse to encourage the client todo postoperative respiratory exercises and change positions every 1to 2 hours. Assisting the client towalk as soon as possible will increase ventilation and perfusion. Italso decreases venous stasis andthereby the risk for developingthrombophlebitis, promotes elimi~

nation, maintains muscle tone, andfosters a more hopeful outlook.

When peripheral vascular circulation is impaired, absorption of intramuscular analgesia will be delayed, and pain relief will be inadequate. If the second dose is givenbefore the first dose is completelyabsorbed, sedation and respiratorydepression may occur. Accumulation of drugs in the elderly also occurs because of decreased clearance by the liver and kidneys. Frequent assessment of the client's level of pain and vital signs will helpthe nurse schedule analgesia for optimal effect. Increasing the intervalbetween doses and giving analgesiaintravenously might be considered.

There is an increased potentialfor delayed return of bowel function because of sluggish peristalsisassociated with aging and the extensive surgical procedure. Nasogastric intubation will be necessaryuntil peristalsis returns to preventaccumulation of fluid and gas inthe bowel. Removal of all or part ofthe colon reduces the capacity toabsorb water, some electrolytes,and bile salts. Diarrhea may occurafter the bowel begins to function.When large portions of the colonare removed, feces will always bemore liquid. The nurse must monitor for fluid and electrolyte imbalances and maintain appropriate intravenous therapy.

EyaluationThorough and ongoing assess

ment of the client will give thenurse appropriate data by which toevaluate care. Expected client outcomes are listed in the box on page183. Angiodysplasia of the colon isa disease entity that is not wellknown. The nurse who is knowledgable about this common, progressive disease will be more effectivein all aspects of nursing care.

ReferencesI. Boley. S. J.• and others. On the nature and

etiology of vascular ectasias of the colon. Degenerative lesions of aging. Gastroenterology72:650-660. Apr. 1977. .,

2. Nath, R. L., and others. Lower gastroIntesttnal bleeding. Diagnostic approach and management conclusions. Am.J.Surg. 141:478481, Apr. 1981.

3. Patras, A. Z., and others. Managing GIbleeding: it takes a two-tract mind. Nursing84 14:26-33, July 198.4.

4. Groff, W. L. Angiodysplasia of the colon.Dis.Colon Rectum 26:64-67, Jan. 1983.

5. Ryan, P: Changing concepts in diverticulardisease. Dis.Colon Rectum 26:12-18, Jan.1983.

6. Smith, G. F., and others. Angiodysplasia ofthe colon. A review of 17 cases. Arch.Surg.119:532-536, May 1984.

7. Scully, R. E., and McNeely, B. U. Weeklyclinical pathological exercises (Case 36)N.Engl.J.Med. 291:569-575, 1974.

8. Weaver, G. A., and others. Gastrointestinalangiodysplasia associated with a?rtic val~edisease: part of a spectrum of angtodysplaslaof the gut. Gastroenterology 77: I-II, July1979.

9. Rogers, B. H. Acquired angiodysplasia. (letter) Am.J.Gastroenterol. 78:846-847. Dec.1983.

10. Howard, O. M., and others. Angiodysplasia ofthe colon. Experience of 26 cases. Lancet2:16-19, July 3,1982.

I I. Galloway, S. J., and others. Vascular malformations of the right colon as a cause of bleeding in patients with aortic stenosis. Radiology113:11-15, Oct. 1974.

12. Johnson, D. G., and Coleman, R. E. Newtechniques in radionuclide imaging of the alimentary system. Radiol.Clin.North Am.20:635-651, Dec. 1982.

13. Fischbach, F. T. A Manual of Laboratory Diagnostic Tests. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, J. B.Lippincott Co.• 1984, pp. 775-778.

14. Sprayregen. S .• and Boley. S. J. Vascular ectasias of the right colon. JAMA 239~962-964,

Mar. 6. 1978. .15. Rogers, B. H. G., and Adler, F. Hemangio

mas of the cecum: colonoscopic diagnosis andtherapy. Gastroenterology 71(6):1079-1082,1976.

16 Carpenito, L. J. Nursing Diagnosis: Application to Clinical Practice. Philadelphia, J. B.Lippincott Co., 1983.

17. Scherer. J. C. Lippincott's Nurses' DrugManual. Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott Co.,1985, pp. 597-599.

18. Shepherd, M. J., and Swearington, P. L. Z·track injections. Am.J.Nurs. 84:746-747,June 1984.

19. Querin, J. J., and Stahl, L. D. Twelve simple,sensible steps for successful blood transfusions. Nursing 83 13:34-43, Nov. 1983.