jstamatel.files.wordpress.com€¦ · Web viewPre-Publication Version. Stamatel, Janet P., Shawn...

Transcript of jstamatel.files.wordpress.com€¦ · Web viewPre-Publication Version. Stamatel, Janet P., Shawn...

Pre-Publication Version

Stamatel, Janet P., Shawn Bushway, and William Roberson. (2013) “Shaking Up Criminal Justice Education with Team-Based Learning.” Journal of Criminal Justice Education. DOI:10.1080/10511253.2013.782054

SHAKING UP CRIMINAL JUSTICE EDUCATION WITH TEAM-BASED

LEARNING

Janet P. Stamatel*Assistant Professor

Department of SociologyUniversity of Kentucky

1571 Patterson Office TowerLexington, KY 40506

Shawn D. BushwayProfessor of Criminal Justice

Professor of Public Administration and PolicySchool of Criminal Justice

219 Draper HallUniversity at Albany135 Western AvenueAlbany, NY 12222

William D. RobersonDirector, Institute for Teaching, Learning and Academic Leadership

069 LibraryUniversity at Albany

1400 Washington AveAlbany, NY 12222

*corresponding author

Biographical Information of Authors

Janet P. Stamatel is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of

Kentucky. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Chicago. Her research

interests include cross-national crime comparisons, the consequences of macro-level social

changes on social order, and quantitative methods.

Shawn D. Bushway is Professor of Criminal Justice and Professor of Public Administration and

Policy at the University at Albany (SUNY). He received his Ph.D. in Public Policy Analysis and

Political Economy in 1996 from the Heinz School of Public Policy and Management at Carnegie

Mellon University. His current research focuses on the process of desistance, the impact of a

criminal history on subsequent outcomes, and the distribution of discretion in the criminal justice

sentencing process.

William D. Roberson is Director of the Institute for Teaching, Learning and Academic

Leadership at the University of Albany (SUNY). He received his Ph.D. in Comparative

Literature from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. His professional work and

research in faculty development is focused on design of courses and learning sequences to

promote critical thinking.

Abstract

This article introduces readers to the philosophy and design of Team-Based Learning (TBL), a method developed by Dr. Larry Michaelsen that was influenced by literature in organizational psychology and pedagogy documenting what actually motivates adults to learn and how they master higher-order learning skills. We describe how TBL was implemented in several criminal justice courses and illustrate how this method has drastically reduced student apathy, increased attendance, improved performance, and eliminated frustration for both instructors and students. Additionally, we reflect on how this method has reshaped our roles as educators.

“Students don’t care about learning.”“Students never come to class.”

“Students don’t do the required readings.”“Students are just not prepared for college.”

These statements comprise some of the common complaints that instructors have about

teaching college students. This list certainly is not exhaustive, but these problems are often the

subject of media articles or blog posts on higher education, not to mention less formal faculty

discussions. For example, one educational website referred to student apathy as “public enemy

number one” (Fertig, 2010), while another warned parents about the “apathy generation”

(College Parents of America, n.d., para. 1). Poor attendance and poor academic performance

have been discussed in media outlets as consequences of either poor secondary preparation (e.g.,

Vevea & Harris, 2011) or market pressures to obtain college degrees despite any real desire for

higher education (e.g., Steinberg, 2010).

While experts debate the root causes of these problems, the reality that many instructors have

to face is that our traditional methods for teaching liberal arts courses — namely large lectures or

didactic seminars — do not adequately address these problems and may even exacerbate them.

Budget constraints that produce larger class sizes, less individualized attention for students, and

fewer campus resources to deal with various students’ needs (e.g., tutors or writing centers)

compound these problems (“Monstrous Class Sizes Unavoidable at Colleges,” 2007).

Additionally, higher education has come under attack for not improving students’ learning or

skill development. In Academically Adrift, authors Arum and Roska compiled numerous studies

that showed disturbing findings such as “no statistically significant gains in critical thinking,

1

complex reasoning and writing skills for at least 45% of students,” after four years of college

(2011, p. 36).

As college class sizes increase, student motivation and preparation decrease, and external

pressures for accountability build, faculty are faced with the challenge of how to help college

students acquire higher-order learning skills to adequately prepare them for the 21st century

workforce. The default method under these conditions is to lecture to students who choose to

come to class. In this setting, students who are motivated to attend class spend the majority of

class time listening to the professor convey content with very limited input of their own. Often

when there are opportunities for greater student input, such as recitation sections for large

lectures or seminars for upper-level courses, the students’ lack of preparation severely limits the

quality of the discussions, creating conditions where instructors naturally revert to lecturing or

scolding in order to fill up the class time.

In response to these challenges, faculty of large lecture classes have experimented with a

variety of techniques to engage students and encourage participation, such as the use of

individual response systems (i.e., “clickers”) or “think-pair-share” discussions (Fies & Marshall,

2006; Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011). These methods are fairly easy to implement and can

provide positive results, but they do not fundamentally transform the learning experience of

students or address all of the problems mentioned above.

An alternative approach is to radically rethink learning objectives, change the nature of

classroom interactions, and redefine roles in order to create an environment more conducive to

learning rather than listening. Imagine a scenario where students spend class time actively

working with material rather than passively listening to the instructor; where students learn how

to become co-creators of knowledge; and where students acquire valuable life-long skills in

2

addition to mastering new content. We attempted to accomplish these lofty goals through one

instructional strategy, the Michaelsen method of Team-Based Learning (TBL), and found that it

fundamentally altered our classroom experiences and redefined our roles as educators. In our

experiences, TBL drastically reduced student apathy, increased attendance, improved

performance, and eliminated frustration for both instructors and students.

In this article we introduce readers to the philosophy and design of TBL, describe how it was

implemented in several criminal justice courses, and illustrate what we were able to accomplish

with this approach. Not only will we discuss how we eradicated the problems that introduced

this article, but we will provide specific examples of our successes. Finally, we will reflect on

how this method has fundamentally reshaped our roles as educators.

What is Team-Based Learning?

Team-Based Learning (TBL), developed by Dr. Larry Michaelsen, was influenced by

literature in organizational psychology and pedagogy documenting what actually motivates

adults to learn and how they master higher-order learning skills (Michaelsen, Knight, & Fink,

2004). In contrast to the largely passive learning environment of a lecture class where students

are encouraged to come to class, pay attention, and take notes, TBL is an active learning

environment where students work in permanent teams of 5-7 students to tackle challenging

problems that require concrete and public decisions. The ability of teams to effectively make

quality decisions depends on how well they have prepared for class and processed course

content. Students are frequently held accountable for out-of-class preparation so that they have a

common foundation of material with which to work during the team exercises. The permanent

3

team structure gives students time to develop skills for making sound decisions together

(Michaelsen, Knight, & Fink, 2004).

TBL differs from traditional lectures in two important ways. First, in the lecture format

the majority of time is spent conveying content with application activities typically completed

outside of class (e.g., homework, papers, and/or exams). In the TBL environment, learning basic

content is completed individually outside of class, but preparation is assessed in class and then

the bulk of class time is spent engaging in application activities that are typically completed by

teams. The second way in which the two approaches differ is that in the lecture format, the

instructor is the creator and conveyor of knowledge and is centrally responsible for the learning

environment. With TBL the instructor is a facilitator of knowledge creation and students

become co-creators of knowledge (Michaelsen, Knight, & Fink, 2004; Michaelsen & Sweet,

2012; Sibley, 2012). In other words, TBL is an example of the flipped or inverted classroom in

terms of changing both the structure and the roles of a traditional college class (Demetry, 2010;

Fink, 2004; Talbert, 2012).

A typical Team-Based Learning course will have 4-7 instructional units. For each unit,

the instructional activities over a period of 2-4 class meetings consist of the following:

1) A substantial reading assignment (outside of class)

2) Readiness Assurance Process (in class), consisting of a test of individual preparation

followed by a test of team preparation

3) Clarification of lingering confusion about the assigned readings (in class)

4) Team application tasks using the material to delve more deeply into complex ideas (in

class)

4

5) Assessment of learning (individual and/or team tests or assignments) (in or outside of

class) (see Fink, 2004).

The Readiness Assurance Process (RAP) is the first step in team development. Early in

each unit students take an individual, multiple choice, Readiness Assessment Test (RAT) to

measure their understanding of the assigned content as a result of their own, independent efforts.

Immediately afterward, without knowing the results of their individual tests, the student teams

take the exact same test for a team score. Both components factor into students’ grades. This

individual-then-team evaluation process has a double psychological function. First, the

Individual RAT ensures that students do not use their teams to cover over their individual failure

to prepare. Second, the Team RAT requires the team to practice analysis, reflective thinking, and

decision-making early and often.

The Team RATs are administered using a special instrument called the IF-AT form

(Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique, produced by Epstein Educational Enterprises),

which is pictured in Figure 1.1 The IF-AT form functions much like a scratch-off lottery card, in

which the correct answer is hidden under a screen and appears when scraped with a coin. Teams

get full credit for uncovering the correct or preferred answer on the first try and reduced credit

for getting it right on other tries. In this way, students immediately learn if they chose the right

answer, and they can start to figure out ways to arrive at a better answer if they were initially

incorrect. The possibility of partial credit in the team exam provides an incentive for teams to

continue to work toward figuring out the right answer, encouraging students to master the course

content and to work on decision-making skills.

The final stage of the RAP is an appeals process, whereby students can write an argument

asserting that a question was wrong, vaguely worded, or too narrowly conceived. This is not an

1 These forms are available for different numbers of questions.

5

opportunity to simply complain; rather, students must construct logical arguments and support

them with evidence from the course readings. They are allowed to use their books and notes at

this time. If the instructor grants the appeal, only the team that writes an appeal is given credit

for the corrected answer. This process encourages students to carefully consider the course

material and it builds their confidence in their mastery of the material. This is an important

mechanism for allowing students to become co-creators of knowledge.

[Insert Figure 1 here]

Roberson often encourages professors to make an occasional mistake on RATs on purpose

to encourage teams to actively engage in this appeal process. The goal is to encourage

individuals and teams to take responsibility for their learning by giving them a structure that

rewards exactly the type of critical thinking that the professor hopes to promote. Appeals are

only awarded if the team makes a valid argument, based on the reading, for why an alternative

answer should be accepted. Good appeals will often acknowledge the validity of the “correct”

answer, but provide a compelling argument for an alternative perspective. Therefore, even in an

apparently simple test for preparation and basic comprehension, students can begin to wrestle

with the nuances of the course content. This part of the process can be disconcerting for new

TBL instructors because it shifts the locus of control for learning and, to some extent, for grades

to the students. However, we have found that the appeals process generates lively, stimulating

discussions and encourages students to invest in their own learning.

When the appeals are submitted, the instructor then takes a few minutes to review questions

that teams found problematic and questions from individual students. This is the time to lecture.

Unlike traditional lectures that cover everything the professor believes is important, in TBL the

professor clarifies only the most difficult concepts to an informed and receptive audience that has

6

just spent a fair amount of time trying to answer questions on these concepts. In the authors’

experiences, it is common to hear exclamations of “now I get it” during this process. This does

not usually happen in traditional lecture, because students have not yet grappled with the

concepts on their own. This part of the class is brief, and we have found that students do not

need extensive lectures precisely because they have already taught themselves the material

outside of class and during the RAP.

After the RAP, a TBL class moves on to team tasks and challenges, which are the core of

the TBL experience. The purpose of these tasks is to problematize the course material through

situations and scenarios that require students to use their new information and their reasoning to

solve problems (reach decisions) that go well beyond recall and comprehension. They are

specifically designed to teach students higher-order learning skills, such as applying, analyzing,

evaluating, or creating (Bloom, 1974; Sweet & Michaelsen, 2012). There are some general

principles for these exercises, sometimes referred to as the four S’s. The tasks should pose a (1)

Significant problem, which is the (2) Same problem for all teams. The teams are asked to make

a (3) Specific choice, and then are required to report out (4) Simultaneously (Sibley, 2012). We

provide a specific example of a team exercise below.

A unit starts with the RAP and then continues with multiple days of exercises and follow-up

discussions, depending on the depth that the instructor has planned to reach in a unit. Once this

phase is completed, then the unit ends with an assessment of what the students learned

throughout the sequence. This unit assessment can be an exam, paper, or other kind of graded

activity and it can be administered individually and/or as a team assignment.

Why Does TBL Work?

7

Psychologically, TBL provides a motivating framework that builds from both cognitive

processes and socializing forces. On the cognitive side we know from research in neuroscience

that it is the active, applied decision-making of individuals and teams that drives the learning

process. The brain responds to information that it can use and ignores information that is not

perceived to be immediately usable (Zull, 2002). By focusing on student actions as decisions

that will be improved through use of available, relevant information (course content), TBL

ensures that students’ encounters with course information will be active and analytical, based on

reflections such as: How will this information help me? How will this information be useful?

This process stands in stark contrast to the traditional lecture format, where information is

presented, often in large amounts, long before students will have the opportunity to test its

usefulness. As a result, the brain dumps much of the information covered in a lecture course

before being fully processed.

In terms of the social framework, TBL creates a dynamic in which students must function

within and be responsible to a community of peers. Students will often, initially, resist the notion

that their peers might affect their perceived success or failure. However, experience in the teams

teaches that the group is more effective and collectively more intelligent than any given

individual. As confidence in the collective capacity of the community grows, so does individual

student confidence in his/her own, individual ability to master information and participate

meaningfully in the team’s decision-making. The result is a community of growing candor and

improving competence that makes students more open to new ideas and information.

Also contributing to the learning dynamic of TBL is the fact that, because of the group

interactions, every student receives a level of feedback rarely attained in more traditionally

taught courses. In a standard lecture course, the instructor often serves as the single source of

8

feedback for dozens of students. In the TBL classroom, the feedback occurs at multiple levels.

First, the individual quiz provides direct feedback on the students’ individual preparation. The

team quiz then ensures an additional level of peer-to-peer feedback. The team tasks and other

assignments offer more opportunities for feedback within a group and between the teams and the

instructor. When the teams report publicly via the 4S process, they receive yet another level of

feedback because they compare their responses with those of the other teams.

Evidence of Success

Stamatel and Bushway have used TBL in 14 undergraduate criminology and criminal justice

courses to date and four graduate classes. Courses consisted of introductory criminology; upper-

level, special-topics courses including economics and crime, information use in criminal justice,

and comparative criminology; and a graduate class on research methods. Class sizes ranged

from 15 to 75 students. Student populations consisted of first-years, seniors, and MA students,

including older, non-traditional students. Although we have yet to conduct a systematic outcome

evaluation of our TBL courses, we have witnessed remarkable transformations in our classes that

have been substantiated by outside observations by Roberson and members of our departments

conducting peer teaching reviews. The transparency of the TBL method makes the changes

readily visible to instructors, students, and outside observers. The examples below illustrate how

TBL was able to address the four teaching challenges introduced at the beginning of the paper:

apathy, attendance, preparation, and skill development. We acknowledge that the evidence is

anecdotal and more systematic evaluations are warranted; however, our purpose in this paper is

to explain how TBL works and what it can accomplish from the point of view of the instructors’

experiences.

Apathy

9

How often do you see students smiling, cheering, and high-fiving one another after a test?

This is a regular occurrence in our TBL classes. The permanent team structure and frequent

interactions create an environment where students care about their own learning and they care

about what others think about them. There are also a lot of small interactions between the

instructor and the students, both in teams and individually, so that even in large classrooms you

eradicate the anonymity that breeds apathy. We know all of our students by name and interact

with each of them often.

Prior to implementing TBL, Bushway described his classes as tense, as students tried to

make it through challenging material in a required class. He noticed a marked shift in the class

atmosphere after he began teaching the same course using TBL. As students take ownership of

their learning, the instructor becomes an ally in the battle to conquer the material, rather than a

member of the opposition. Students routinely report newfound interest in material that they

would have never even considered prior to TBL. For example, the following comment was

provided in a year-end course evaluation for Bushway. “The team-based learning aspect of it

really helped me out, and got me thinking in ways I wouldn't have otherwise. He also showed

that he cared about the students, asking how the course is going periodically to individuals which

[sic] showed me that he really has a desire to help us learn and understand the material.”

Students become invested in the course because they feel the instructor and classmates are

invested in them. The team structure and lively classroom environment keep students engaged

and provide many intrinsic rewards for learning, such as respect, confidence, curiosity, pride,

and, importantly, a sense of community that includes the instructor.2

Attendance

2 Video clips of Bushway’s TBL classes, including student interviews, can be found on the University at Albany’s Institute for Teaching, Learning, and Academic Leadership website at http://www.itlal.org/.

10

Frequent assessments, whether RAPs, team tasks, or summary unit assessments improve

attendance by building a high degree of accountability into the structure of the course. Aside

from these grading requirements, students actually want to come to class because they are

invested in their own learning experiences. Students frequently comment on their improved

attendance in verbal communications with instructors and in end-of-semester course evaluations.

Stamatel was often frustrated by class attendance when teaching small, upper-level seminar

classes where only 50-70% of students would come on any given class. With TBL, attendance in

her small seminars typically has been 99% with only occasional absences and it is generally over

85% in her large class. There are few “repeat offenders” as students quickly learn that the price

for not attending is high. Traditional lecturers dread the often-asked question from students who

have missed class — “Did I miss anything important?” TBL students no longer ask this

question. They know that not only is the answer “yes,” but also that they cannot recreate the

class learning experience on their own; therefore, the cost of missing class is higher in TBL

classes than traditional lectures where students can “get the notes” in order to catch up.

Bushway has had a similar experience with improved attendance once switching to TBL. The

modal attendance in his undergraduate class is now 100%, despite the fact that attendance is not

required.

Preparation

When students do attend class in a traditional lecture or seminar, they are often not prepared

to actively participate in the class, which can be very frustrating for both instructors and the

students who are prepared. This problem may be less obvious in a large lecture class than a

small seminar, but in either setting students who do not complete the required work outside of

class are not learning as much during class as the students who are prepared.

11

TBL alleviates this problem by building accountability into every step of the learning

sequence. The most obvious way this happens in TBL is through the RAP described above. The

testing process is transparent so that during the team portion of the test it becomes quite obvious

who is prepared and who is not. The penalty for not being prepared is more than just a low test

score. Students are regularly receiving feedback about their contributions, or lack thereof, from

teammates. When students are taking the team test, the instructor circulates among the teams

and listens to their conversations, primarily to gather immediate feedback about how well

students understand the content. In one class, Stamatel overheard a discussion in which a student

was complaining about how poorly she did on an Individual RAT. Another student asked if she

had done all of the reading. She replied that she had read some, but had skimmed all of it. Her

teammate rolled his eyes and emphatically replied: “You know that you can’t skim in this class!”

Because the team had been working together for several weeks at this point, this exchange came

across as a friendly reminder to be responsible for your own work. It was lighthearted, but

nonetheless effective because young adults care what their peers think of them. Additionally, the

structure of TBL creates an environment whereby students are invested in both their teams and

their own learning. This type of exchange, which happens regularly in a TBL class, is much

more meaningful than having an instructor endlessly remind, threaten, or beg students to come to

class prepared. Students recognize that preparation really matters in this environment. For

example, Bushway had a student report on the course evaluation that “team based learning

challenged me and my team members to be prepared for every class.”

There are also intrinsic rewards for being prepared. Teams value members who are

consistently prepared and often praise them for “saving” a team on a particularly difficult RAP

question. They also congratulate teammates who initially struggle with the material but who

12

improve their performance, even if they never “ace” a RAT. It is also not unusual to overhear

teams discussing strategies for reading large amounts of material or for preparing for the RAP.

Bushway routinely assigns over 100 pages of a reading a week. Although there is some

grumbling, students figure out that they need to read differently than they have in other classes,

and share strategies for accomplishing that task. Bushway teaches the students how to read

criminology papers with a focus on research methods. Students have commented that they have

found that these strategies apply to their reading assignments in other classes. Students teach one

another how to be successful, and those skills are portable to other classes and to other settings

outside of higher education.

Skill Development

The final challenge that TBL has successfully addressed in our experiences is student

preparation for college in general and, more importantly, for life beyond college. Faculty often

lament that students lack basic skills like reading and writing, not to mention higher-order skills

like critical and creative thinking, which makes teaching upper-level and graduate courses

particularly challenging. TBL facilitates various kinds of skill development. The previous

section already described how students learn study habits from one another. In this section, we

will use a fairly simple, but effective, team exercise to illustrate how TBL develops a range of

other skills, including basic reading and writing, critical and creative thinking, and soft skills.

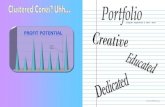

Figure 2 is a typical exercise used by Stamatel in an introductory criminology course.

[Figure 2 here]

Before the assignment is administered, students have already read the chapter of the

textbook on neoclassical theories and have completed the RAP for this material so they have a

basic understanding of the course content needed to complete this task. Stamatel does not lecture

13

on the material before administering this assignment because it is unnecessary. This case was a

high-profile hate crime committed by young adults that received a lot of media attention

(significant problem). First, students have to read the case study by themselves in class (same

problem). When students have to read a lengthy assignment in class, they will often ask one

another to define terms with which they are unfamiliar, thereby giving them an opportunity to

improve their reading comprehension. The permanent team structure provides students with a

comfortable environment where all questions are welcome. Next, students begin to tackle the

assignment by reviewing the different theories in their textbook or notes because they had read

the chapter on this topic several days before. Students practice using the book index, taking

good notes, or highlighting important text because they know they will have to revisit the

material after reading it the first time. Then they begin their discussions about the theories by

clarifying their understanding of the material. For example, they may discuss the differences

between rational choice and deterrence theories. By applying the material to a specific case, they

begin to wrestle with the nuances and complexities of the theories rather than just repeating

definitions that have been memorized. Next they move on to making a choice. While some

answers may be better than others (in this case deterrence theory is not well supported by the

information available in the newspaper article), there is no “right answer” so there is a significant

amount of discussion about how to settle on one answer (specific choice). Here students practice

soft skills like deliberation, persuasion, negotiation, collaboration, compromise, and, ultimately,

decision-making.

Once a decision has been reached, Stamatel has the team write an argument defending their

choice and supporting it with evidence. Because they have already argued the strengths and

weaknesses of their choice, the written arguments tend to be well developed and logically

14

constructed. They have already convinced one another of the soundness of their decision and

now they have to convince the instructor. Stamatel uses these types of assignments to implement

frequent writing activities in a large class without the burden of excessive grading. Even though

each student is typically not writing the assignment (although some teams will divide the labor in

this way), they are still all participating in the writing process. They often have the best writer

on the team submit the written product, allowing the others an opportunity to witness how good

writers work. All team members typically review and edit the assignment before submission,

giving them an opportunity to discuss writing with their peers. We often hear students

discussing spelling, punctuation, grammar, organization, and clarity, in addition to the substance

of the assignment. Students rarely have such opportunities outside of writing classes.

Finally, having the students report out their choices simultaneously to the rest of the class

adds a measure of accountability. They do not want to be embarrassed in front of the whole

class by not coming to a decision on time or by not having a sound argument, so there is some

built-in pressure and good-natured competition to encourage teams to perform at their best level

rather than just turning something in. Teams then have an opportunity to debate each other,

thereby allowing them to consider even more perspectives on the material and teaching them to

defend their choices. These debates tend to be very lively and well-constructed, since students

understand the content very well at this point.

In the course of a 50-minute class, this simple exercise, implemented within the larger TBL

framework, allows students to practice a range of skills in addition to gaining a deeper

understanding of the course content than would be possible in a lecture format or even in a

didactic seminar. Throughout the course of a semester, they practice the same skills numerous

times and their improvement is noticeable. Students are often not aware of all of the different

15

skills they are learning because they are so focused on the task at hand and thoroughly engaged

in discussing the case study. In other words, they are having too much fun to complain about

how hard they are working!

How TBL Changed Us as Teachers

TBL is transformative in terms of how the class environment is structured, how content is

complemented with skill development, and the high level of interactivity, as illustrated in the

examples above. The vast majority of our students have responded positively to the experience,

as evidence by the scores and comments on our formal end-of-semester evaluations as well as

less formal communications with students. Additionally, we have witnessed a number of

positive changes in our students, as TBL has alleviated the four problems we discussed above.

What has perhaps been most surprising for us, however, is how TBL fundamentally has changed

how we perceive our roles as educators. We specifically noticed changes in the following areas:

1. Backward engineering

2. Classroom leadership

3. Locus of attention

4. Immediate feedback

Backward Engineering

Backward engineering is the premise that what you do in class should be driven by what you

want the students to learn (Sweet & Michaelsen, 2012). In the TBL context, the learning goal is

not some body of knowledge that they can regurgitate but an application task that requires the

mastery of a set of skills and concepts. Once the instructor decides what it is that students should

be able to accomplish at the end of class that they could not do at the start of class, the instructor

16

can start making intelligent decisions about what she needs to do to accomplish these goals.

Notably, Roberson has worked with many faculty who cannot articulate what it is that they want

the students to be able to do, although they can list content areas that they want students to

master. Once the instructor clearly identifies the goals of the class (typically 1-3 per class) then

planning a productive class session flows easily from those learning goals.

For example, in one unit of an upper-level, undergraduate course on economics and crime,

Bushway wanted students to be able to identify how organized crime maintains cartels with

violence. Once he clarified this goal, he then constructed a four-week sequence of activities

where students first learned about competitive equilibrium and monopoly/cartel equilibriums

from a textbook. Then students played a game in class, which highlighted the benefits of

collaborating and the incentives to cheat that individual cartel members faced. Next the students

read an article by economist Thomas Schelling arguing that the goal of organized crime is to

create and extract monopoly profits. Then students practiced reading short newspaper articles

about organized crime where they learned to recognize monopoly situations. They next moved

on to two sets of academic articles about real life examples of cartels, one on the mob in the

waste removal industry in New York City and one on the Mexican drug “cartels” (which are not

actually cartels). By articulating the goals up front, Bushway was able to focus a series of

classes on tasks that would meet those goals.

To wrap-up this unit, Bushway used an idea from Michaelsen to assess student learning with

an exam based on a movie. Students watched the movie outside of class before the exam and

then they were tested on how well they could apply the knowledge learned in class to the movie.

In this example, Bushway assigned the movie Untouchables with Robert DeNiro. The key

learning task was to recognize that Capone was the leader of a cartel and that he was enforcing

17

the cartel when he took the baseball bat to a cartel member who had cheated by lowering prices.

The facts of this particular case were never discussed in class. Nonetheless, the majority of the

students were able to recognize that the mob group is a cartel, and that Capone was enforcing the

cartel when he took the baseball bat to the head of a cartel member who had cheated by lowering

prices. One student even reported explaining this to his father as they watched the movie

together prior to the exam.

Bushway took the concept of backward engineering to another level in the graduate class on

research methods. The MA students often questioned the requirement to learn research methods

because they do not intend to be researchers. Yet, faculty know that many graduates go on to

take analyst positions, which requires at least rudimentary research skills and awareness of best

practices. Bushway, with the help of Roberson, developed a collaboration with the state police.

The state police provided data and a series of simple questions that they wanted answered using

the data they had collected but not analyzed. For their final grade, the students were required to

give a presentation to the state police answering these questions. Given that most of the students

had never worked with data before (most didn’t know Excel), choosing this final task

simultaneously identified the key lessons students needed to learn in the class, and provided the

necessary motivation to learn these lessons. Over multiple iterations of the class, Bushway was

better able to structure the class to provide the students the necessary tools they needed to

accomplish this task successfully.

Classroom Leader

Roberson runs a center called the Institute for Teaching, Learning and Academic

Leadership. The inclusion of leadership in the name of what is otherwise a traditional academic

teaching center is intentional. Most instructors, when asked, do not view what they are doing as

18

leading. Yet once the goals of the class are identified, the job of the instructor is to lead the class

towards its goals. That may involve traditional “teaching,” but it may not, if that is not the best

way to accomplish the goal. In Team-Based Learning, the role of the instructor is fundamentally

redefined from someone who does certain identifiable tasks (lecturing, deliver tests), to that of

leader.

Neither Stamatel nor Bushway would have identified their role as leader prior to the

introduction of Team-Based Learning into their courses. Yet Team-Based Learning requires that

the faculty member create classroom content that accomplishes clear tasks according to a clear

set of rules. This forces the instructor to focus on the learning goals, which then allows the

faculty member to become more acutely aware of whether those goals are accomplished. In a

traditional class, the goal is accomplished when the faculty member delivers the content. In the

TBL classroom, the goal is not accomplished until the students can successfully apply what they

learned in a specific situation. The instructor does not accomplish anything – the students do.

The leader is only successful when the students are successful.

Dwight D. Eisenhower is credited with saying that leadership is the “the art of getting

someone else to do something you want done because he wants to do it.” This succinctly

describes the job of a university instructor. Many students are not intrinsically motivated to learn

the material presented in the class, but success only comes when they do, in fact, learn. Team-

Based Learning provides the tools and techniques by which an instructor leads students to

success. The process starts by clearly identifying what the students will learn and then finding

ways to motivate the students to take the necessary steps to accomplish those goals.

This transformation to leader became clearer to Bushway after he made the choice to feature

classroom presentations to the state police as part of the final assessment of MA students in a

19

research methods course. The students’ grades depended in part on the officers’ rating of their

performance. Bushway had many incentives to “look good” since the dean attended the

presentations and significant capital was used to encourage the cooperation of the state police.

But Bushway wasn’t doing the presentation, the students were. In such a situation, Bushway

could only lead his students to success – achieving it was ultimately in their hands.

All three authors have found this role transformation to be incredibly rewarding. There is

nothing intrinsically rewarding about delivering content; however, there is something

exhilarating about helping students accomplish learning goals that the students themselves want

to accomplish but did not think possible.

Locus of Attention

In a traditional lecture, the instructor is the center of attention. All eyes and ears are focused

on him/her. Even if a student asks or responds to a question, everyone looks to the instructor for

a response to the student’s input. The classroom is typically physically structured to keep the

instructor at the center of attention. In TBL, the attention dramatically shifts toward the students.

They do the majority of both the talking and listening. The classroom is physically structured

around the teams, even in large lecture halls. The instructor weaves in and out of the groups

rather than standing in the center of the room.

TBL is inherently student-centered, which empowers students to take control of and

responsibility for their own learning. This shifting of attention away from the instructor can be

disconcerting at first as a new TBL instructor may feel like they are giving up control of their

class. In reality, this is not true because of the highly structured nature of the TBL classroom.

Most of the instructor’s control, however, is implemented behind the scenes. The instructor

maintains control by designing effective RAPs and team activities so that their role during class

20

can be minimized. Rather than threatening the authority of the instructor, shifting the locus of

attention to students is instead very liberating. It allows faculty to focus energy on the intellectual

tasks of teaching rather than the “stage performance” required in a large lecture or the emotional

tasks of dealing with unmotivated and/or unprepared students. It makes teaching more

interesting, less stressful, and more enjoyable. In the classroom, the instructor becomes the

facilitator and the leader— listening, learning, and capitalizing on student-generated “teachable

moments” in order to lead students to achieving the course learning goals.

Immediate Feedback

We have already discussed how students receive a lot of immediate feedback on their

performance from the structure of the RAP and from the frequent interactions with one another

and with the instructor. These same processes also provide immediate feedback to the instructor.

In a large lecture, an instructor either gauges students’ comprehension from facial expressions or

responses to the “Do you have any questions?” prompt, neither of which is a very reliable way of

knowing what the entire class is thinking. Even in smaller seminars, a few vocal students

dominate discussions and they are not representative of the entire class. Often it is only at exam

times or during end-of-semester evaluations that instructors know how effective their methods

are and how much students are learning.

In TBL, instructors have a steady stream of feedback by which they can gauge the level of

understanding across the entire class, even a large one. The information comes from multiple

sources, such as listening to the Team RAT discussions assessing basic comprehension of the

material, watching students actively work through problems in team activities, or answering

questions from students who will catch the instructor passing by and take advantage of a semi-

private exchange rather than asking a question in front of the entire class.

21

The feedback is truly eye opening. Stamatel realized that a book that she had used for two

semesters in a didactic seminar was a very difficult read for her students only after she had used

the book for the first time in a TBL class. Listening to the Team RAT discussions provided

important information, such as “I don’t know half the words this guy is using” or “I really tried,

but I just couldn’t understand this book.” Students are unlikely to make such admissions in front

of the entire class for fear that they may be the only one struggling.

In another example, Stamatel would introduce the concept of a crime rate to students by

explaining the rationale for the concept, showing how a crime rate is calculated, and then guiding

students through a few examples. She would always follow up asking if students understood her

presentation and if there were any questions. She rarely got any requests for clarification and

sometimes she would be told that it was a familiar concept that students had already learned in

other classes. Needless to say, it was very frustrating when students would later make incorrect

comparisons of crime across different locations because they did not truly understand crime

rates.

When Stamatel introduced the same idea in a TBL class, she did not lecture about it at all.

Instead she gave teams an apparently simple exercise with some crime counts and population

data and asked teams to calculate crime rates and explain the results in lay terms. She thought

this would be a quick exercise. Instead it became immediately apparent that this was a very

difficult task. Students first looked nervously at their teammates. Then there was awkward

silence, which is especially unusual in a TBL classroom. Finally, one person on each team

would either admit that they didn’t understand the exercise or attempt to complete it. Others

would then join in, mostly mumbling that they didn’t know what they were doing. The instructor

quickly learned that the math behind the calculation was either intimidating or difficult and that

22

the rationale behind the concept was completely lost on the students. It was a deflating moment,

but an informative one. Eventually students worked together to figure out the assignment and

the instructor spent a considerable amount of time debriefing the exercise. More importantly,

Stamatel completely restructured how she taught this foundational concept in future classes

based on the feedback that she obtained only because of the structure of TBL.

The immediate feedback provided by TBL challenges instructors’ assumptions about what

students know. The information that TBL provides about prior knowledge, ability to read

productively, or current understanding of the course material can sometimes be depressing, and

we can lament about what our students are lacking. However, the important advantage of TBL is

that it makes the unknown transparent and provides instructors with specific cues about where

students are in their learning trajectories. Only then we can turn our lamentations into concrete

actions to improve student learning.

Conclusions

The problems we experienced as college instructors are not unique to us. Student apathy,

poor attendance, and lack of preparation have been well documented in both academic and lay

circles. We were able to combat these problems effectively and quickly using Michaelsen’s

Team-Based Learning method. By leveraging both cognitive processes and socializing forces,

TBL motivates students to come to class, and teaches students valuable skills, in addition to

conveying course content.

Our goal in this paper was to explain how and why TBL works and to document the positive

transformations that we have experienced. We acknowledge that our anecdotal evidence needs

to be substantiated with more systematic evaluations of teaching methods and learning outcomes,

23

but this can only be possible if more instructors are willing to implement and evaluate TBL in a

variety of settings.

We have witnessed remarkable transformations in our class environments, students’

performances, and our interactions with students as a result of TBL. Additionally, the method

has reshaped how we define our roles as instructors. It has made teaching – and we believe

learning – more enjoyable. It has also affected our careers in positive ways. Bushway, for

example, was able to dramatically improve his teaching evaluations and get promoted, while still

increasing the rigor of his classes. We contend that TBL is also an important tool for changing

the culture of teaching and learning across college campuses from one where apathy and

disengagement are normal to one that empowers students to be responsible for their learning and

that gets both students and instructors excited again about spending time together in the

classroom.

24

References

Arum, R., & Roksa, J. (2011). Academically adrift: Limited learning on college campuses. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bloom, B. S. (1974). Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York, NY: David McKAY.

College Parents of America. (n.d.). Is your college student a member of the “apathy generation”? Retrieved June 19, 2012, from http://www.collegeparents.org/members/resources/articles/your-college-student-member-%E2%80%9Capathy-generation%E2%80%9D

Demetry, C. (2010). Work in progress -- An innovation merging “classroom flip” and team-based learning. 40th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education. Washington, DC.

Fertig, Jason. (2010). Student apathy - public enemy number one. Retrieved June 19, 2012, from http://www.mindingthecampus.com/originals/2010/11/student_apathy_public_enemy.html

Fies, C., & Marshall, J. (2006). Classroom response systems: A review of the literature. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 15(1), 101–109. doi:10.1007/s10956-006-0360-1

Fink, L. D. (2004). Beyond small groups: Harnessing the extraordinary power of learning teams. In L.K. Michaelsen, A.B. Knight, & L.D. Fink (Eds), Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups in college teaching (pp. 3–26). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Michaelsen, L. K., Knight, A. B., & Fink, L. D. (Eds.). (2004). Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups in college teaching. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Monstrous class sizes unavoidable at colleges. (n.d.).msnbc.com. Retrieved from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21951104/ns/us_news-education/t/monstrous-class-sizes-unavoidable-colleges/

Sibley, J. (2012). Facilitating application activities. In M. Sweet & L.K. Michaelsen (Eds.), Team-based learning in the social sciences and humanities (pp. 33–50). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Steinberg, J. (2010, May 23). Many of my students really did not belong in college. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html

Svinicki, M. D., & McKeachie, W. J. (2011). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

25

Sweet, M., & Michaelsen, L. K. (2012). Criticaling cognitive apprentices with team based learning. In M. Sweet & L. K. Michaelsen (Eds.), Team-based learning in the social sciences and humanities (pp. 5–32). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Talbert, R. (2010). Inverted classroom. Colleagues, 9(1), Article 7. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/colleagues/vol9/iss1/7

Vevea, R., & Harris, R. (2011, September 9). Educators tackling problems in two crucial age groups. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/09/us/09cncschools.html

Zull, J. (2002). The art of changing the brain. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

26

Figure 1. Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique (IF AT) form.

27

Figure 2. Team exercise on neoclassical theories.

Read the CNN story about a recent murder in Jackson, Mississippi

(http://www.cnn.com/2011/CRIME/08/06/mississippi.hate.crime). Which neoclassical theory

best explains why this crime happened?

1. rational choice

2. deterrence

3. routine activities theory

Briefly explain the theory. Then build an argument explaining how the theory you chose can

explain this particular case. Use evidence from your textbook and the CNN story to support your

argument. Lastly, discuss the limitations of the chosen theory for explaining this case.

28