WARFAREINTHEEUROPEANNEOLITHIC - UMass...

Transcript of WARFAREINTHEEUROPEANNEOLITHIC - UMass...

Acta Archaeologica vol. 75, 2004, pp. 129–156 Copyright C 2004

Printed in Denmark ¡ All rights reserved ACTA ARCHAEOLOGICAISSN 0065-001X

WARFARE IN THE EUROPEAN NEOLITHICby

J C

INTRODUCTIONThe Neolithic of northwestern Europe has been de-scribed as peaceful and idyllic, while the subject ofwarfare has been given little or no consideration.Warfare is an important factor in social and culturalchange, however, and the frequency and scale of war-fare had a significant impact on the development ofNeolithic society. Warfare is difficult to prove archae-ologically, since evidence of warfare, such as skeletonswith injuries, may have other interpretations. Thequestion of whether armed conflicts occurred in theNeolithic is linked to the interpretation of the socialstructure, and anthropological analyses of small-scalewarfare in primitive societies are therefore important(1). Anthropological surveys of the prevalence,character and causes of war cannot prove that therewas war in the Neolithic, but they might help to ex-plain the patterning of material remains and candemonstrate the social conditions of war.

This article attempts to employ the anthropologicaltheories concerning warfare in an archaeological con-text. The evidence for violent conflicts is studied, andthe development of warfare is traced from its originto the end of the Neolithic. It is not a complete surveyof sites and objects connected to warfare, but merelyan attempt to demonstrate that evidence of war canbe found throughout northwestern Europe (includingPoland, Germany, France, Benelux, Southern Scand-inavia and the British Isles). The introduction of agri-

1. The term primitive is employed in this article to describe societiesthat are not urban or literate and which use pre-industrial tech-nology.

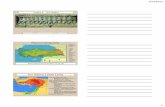

culture did not occur at the same time across the area,so a simplified chronology, based on the terms frommid Germany, is used to designate the differentperiods (Fig. 1).

DEFINING WARThe first important step is to define warfare. Warshould be considered part of the larger category ofconflict, which also includes murders and feuds(Chagnon 1990, 79f.). Warfare is differentiated bybeing a social activity, sanctioned by society, and di-rected against another group (Otterbein 1994, 97ff.).The organization separates war from random brawlsor simple murder, but war is more than actual com-bat, and also includes preparations for battle, train-ing, organisation and transport (Ehrenreich 1997, 9).A state of war does not have to end with a battle, thepossibility or mere threat of combat can sometimesdecide a conflict. Defining the war-making unit is im-portant, in order to distinguish primitive forms of jus-tice, like vendetta and feuds, from warfare against an-other group (Schneider 1968, 238f.). This is problem-atic however, since group boundaries are oftenflexible or unclear. Common language and culturalidentity does not necessarily mean that differentgroups consider themselves part of the same society,

5500–4200 BC Early Neolithic4200–2800 BC Middle Neolithic2800–2200 BC Late Neolithic

Fig. 1. Simplified chronology.

130 Acta Archaeologica

and some societies wage war on the same groups theytrade or exchange marriage partners with (Ross 1983,174).

In the present context I will use a rather wide defi-nition of warfare, which is relevant to the study of apre-state society documented through archaeologicalevidence. War can be defined as the use of organised

lethal force by one group against another independent group.

This definition excludes individual aggression and fo-cuses on the fact that war is a social activity.

THE PREVALENCE OF WARThe frequency and prevalence of war among primi-tive societies described by ethnographers is an import-ant analogy. If warfare was universal and frequent insocieties that can be compared to the Neolithic societ-ies in the archaeological record, it cannot be claimeda priori that warfare was non-existent in the EuropeanNeolithic. Cross-cultural surveys of primitive societiesfrom around the World give a general picture of theprevalence of war. One survey, with a sample of 50societies, showed that 15 rarely or never went to war,but that only 4 of these had no military organization,and thus no capability to wage war (Otterbein 1989,148). In another sample of 90 societies only 11 groupswere found to engage in warfare rarely or never,while 53 societies went to war at least once a year(Ross 1983, 182f.). The results indicate that warfareis common among primitive societies, and that only10% did not participate frequently in armed conflicts.Most of these societies were living in areas with lowpopulation densities, were geographically isolatedfrom other groups or were defeated refugees drivenfrom their former territory. Moreover many of the so-called ‘‘peaceful’’ societies had a very high homiciderate. Among agriculturists truly peaceful societies areeven rarer, probably because their fields, food storesand possessions keep them from fleeing conflicts, analternative to war often used by more mobile hunter-gatherers (Keeley 1996, 28ff.).

Some modern anthropologists have neverthelessclaimed that warfare is rare in pristine societies, andthat the ethnographically documented wars arecaused by contact with the western civilisation (Fergu-son 1990, 51ff.). If this is indeed the case, then ethno-graphic sources cannot shed light on the origins of

war. The question of whether war has existed sincethe birth of mankind can only be answered by archae-ology (Haas 1999, 13).

WAR IN PRIMITIVE SOCIETIESSome anthropologists see a fundamental differencebetween ‘‘true war’’, distinguished by being seriousand deadly wars of conquest fought by civilized states,and primitive warfare, described as being stylized,ritualistic and harmless (Newcomb 1960, 328).

The anthropologist H. Turney-High characterizedprimitive warfare by, among other things, weak lead-ership, absence of organized and trained units, inef-fective tactics, as well as poor mobilization and logis-tics. These deficiencies are not caused by militaryshortcomings, however, but by the social and econ-omic organization of primitive societies. Coercingpeople into an army, training them to obey ordersand arrange supplies to keep the army in the fieldrequires the centralised leadership and economicpower of a state. The differences in the conduct ofwarfare are thus a direct consequence of the weakerauthority of leaders, the egalitarian social structure,smaller populations and less surplus production (Kee-ley 1996, 42ff.).

Primitive warfare was not considered very deadly,since ethnographers observed that most battles werebroken off when both sides had suffered a few casual-ties. This does not describe the mortality of war, butits form, since the number of dead was not comparedto the size of the population. In primitive societies theproportion of deaths caused by warfare is 10–40%,while the percentage is below 5% in civilized societies.Because primitive societies have a higher frequencyof war and a smaller population, even a few losses perbattle can cumulate to a catastrophic level (Keeley1996, 88ff.).

THE CHARACTER OF WARWarfare is more than set piece battles between twoarmies, but can be divided into the following types:

Ambushes and raids is the most frequent form ofwarfare in primitive societies (Otterbein 1989, 40).They range from elaborate ambushes, where an at-tacker waits for the enemy; to simply sneaking into

131Warfare in the European Neolithic

enemy territory, killing anyone encountered. Attack-ing an enemy village just before dawn is the mostcommon form of raid. The victims of both raids andambushes are usually surprised, unarmed and out-numbered. Casualties are often relatively few how-ever, since the attacker hurries away before a counter-attack can be mounted, but frequent raiding can re-sult in a high cumulative fatality rate (Keeley 1996,65f.). Raids are characterised by the fact that mostvictims are killed when they try to flee, and are there-fore attacked from behind, and that a high proportionof the victims will be women or children.

Massacres are surprise attacks whose purpose is toannihilate an entire village or social unit, and areknown from several simple societies (Vayda 1968,280). The casualties rarely amount to more than 10%of the population, but cases of total annihilation areknown. Massacres occur only infrequently, but oncea generation is not unusual (Keeley 1996, 67f.). Thevictims of a massacre comprise both men and women,adults and children.

Battles between two armies are often arranged inprimitive societies, and usually involve decorativedress and exchange of insults. These features are con-sidered ritualistic in nature, but it is important to re-member that all battles require the co-operation ofboth parties in order to take place (Keeley 1996, 59f.).Most primitive societies used projectile weapons, suchas spears or bows, in formal battles, while meleeweapons were used only to dispatch a wounded ora fleeing enemy. Advanced tactics and manoeuvresrequire discipline, training and leaders, so a simpleline was often the only formation used in primitivebattles (Otterbein 1989, 39f.). War leaders are foundin several egalitarian societies, but they lead from thefront, instead of directing the battle from behind.Many primitive societies have warriors trained incombat, but they train as individuals, not as co-ordi-nated units. The weak command systems do notmean that battle plans or tactics were never used.Flank or rear attacks, ruses or co-ordinated ma-noeuvres by separate groups have been commonlyused in primitive societies (Keeley 1996, 42ff.). Thevictims of a battle are usually only men, since womenrarely, if ever, participate in combat.

Campaigns are beyond the logistic capabilities ofmost primitive societies. They can only provide sup-

plies and ammunition to keep an army in the field fora few days (Newcomb 1960, 328f.), and the use ofstrategic planning is thus severely limited. The im-plementation of most strategies were customaryrather than deliberate, but primitive societies can besaid to have used attrition, by frequently raiding theenemy, while massacres of entire settlements can betermed a total-war strategy (Keeley 1996, 48).

THE OBJECTIVES OF WARThe objective of primitive warfare is another elementwhere we find important anthropological analogies. Itwas once a common assumption that economic andpolitical motives were lacking in the earliest forms ofwarfare (Malinowski 1968, 259), which were motiv-ated by personal goals, such as obtaining prestige.Cross-cultural surveys indicate, however, that econ-omic motives were predominant in primitive societiesas well (Keeley 1996, 115).

Defence and revenge. The most frequent and funda-mental cause of war in primitive societies is the needto defend against an aggressor, but a few peacefulsocieties, who always decided to flee rather than de-fend themselves, are known from the ethnographicrecord (Keeley 1996, 30f.). Revenge for violationsagainst the group is also a common motivation, butcan be regarded as an active form of defence, since italso serves as a deterrent against further attacks (Vay-da 1967, 87). Retaliatory strikes may be caused bymurder, insults or economic issues, such as theft orpoaching, but there is a great deal of variation in thetype of offences which calls for revenge (Ferguson1990, 45).

Territory and plunder. Primitive societies also foughtover land and the right to use important resources,but complete occupation of an enemy’s territory wasrare. Frequent losses in warfare could force a groupto abandon parts of its territory, allowing the victorto gradually expand into the resulting unsettled bufferzone (Vayda 1976, 30f.). Another important goal inprimitive warfare was the plunder of portable wealth,such as livestock, food stores or even prisoners (oftenwoman), but slaves are only found in hierarchical so-cieties (Ferguson 1990, 38).

Trophies and honour. Prestige was often a goal inprimitive warfare, but not as important as economic

132 Acta Archaeologica

objectives (Otterbein 1989, 66). In many primitive so-cieties status is achieved by showing bravery in battleor by taking trophies, such as heads, scalps or otherbody-parts. These trophies had a huge symbolic sig-nificance, as a proof of the warrior’s worth or as aninsult to the slain enemy and to enrage his living rela-tives. In some societies trophies were used in initiationrites or were believed to have spiritual powers thatstrengthened the possessor (Keeley 1996, 99ff.).

Conquest and subjugation. Wars of conquest, where anoccupied territory is added to the victor’s and thepopulation subjugated, are only fought by states, sincepre-state societies do not have the necessary insti-tutions to achieve political control of another society(Otterbein 1989, 68).

WAR AND SOCIETYThe character of war is determined in particular bythe social structure, and in turn war is an importantfactor in the development of the social organization.The Neolithic societies in northwestern Europe areusually classified as tribes (Milisauskas 1978, 120), aterm used by anthropologists to describe relativelyegalitarian societies organized by pan-tribal associ-ations, such as kin groups, age-grades or sodalities,and usually incorporating a few thousand individuals.The tribal leader has influence rather than power,unlike the more hierarchical and centralized chiefdoms,where the chief controls and redistributes the econ-omic surplus (Keeley 1996, 26f.). Warfare has anenormous influence on the social complexity and thepopulation size of a society. In regions where war isfrequent the population will concentrate in largergroups, since there is a tactical advantage in greaternumbers. Fear of raiding also increase sedentism,partly because of the advantage of defence works, andpartly because an increased group size requires anintensification of production (Ferguson 1994, 88f.).Warfare also creates a need for leaders able to co-ordinate and organize an army. The status of a warleader often depends on military success, whichmeans they will have a personal interest in warfare,and often seek to institutionalize their authority (Fer-guson 1994, 94). A separate class of military specialistscan, combined with an intensified production, in-crease the social stratification (Ferguson 1984, 56f.).

MILITARY ORGANISATION

The military organisation of primitive societies aredetermined by kinship patterns and the social struc-ture. Social institutions, such as patrilocality, thatunite men into fraternal interest groups gives a higherfrequency of internal warfare or feuds, since thesegroups are able to use force when settling disputes(Otterbein 1980, 204ff.). If men’s loyalties are divided,by matrilocal postmarital residence for example, thefrequency of internal war is reduced, but this createscross-cutting ties between different groups which en-ables the mobilization of larger forces, thus increasingthe likelihood of external warfare against other societ-ies (Ferguson 1994, 16ff.).

The use of professional warriors and the degree ofsubordination are also important aspects of the mili-tary organisation. Political centralization is not a pre-requisite for the existence of professional warriors, butthey are most common in centralized societies, whichcan redistribute resources to an army (Otterbein1989, 20ff.). Professional warriors might belong to astanding army, age-grades or military sodalities, whilesocieties without professional warriors commonlyhave a military organisation consisting of every adultmale. Professional warriors frequently have a highsubordination, but even in egalitarian societies thewar leader’s commands are usually followed (Otterbe-in 1989, 25). Though participation in war was volun-tary in tribal societies the mobilized part of the malepopulation was often higher than in modern states(Keeley 1995, 34f.).

WAR AND EXCHANGE

Warfare obviously have a profound effect on the re-lations between different societies, but war does notpreclude peaceful interactions, such as trade or eventhe exchange of marriage partners (Keeley 1996,121ff.). Exchange and trade are therefore not an indi-cation of the absence of war.

Alliances are another important relation betweenindependent groups, they can provide reinforcements,intelligence, logistic support or a safe refuge. Alliancesare thus of decisive importance in a conflict, andmight be necessary in order to have secure flankswhen fighting an enemy. It is primarily by the nego-tiation of military alliances that leaders gain a per-

133Warfare in the European Neolithic

sonal influence on warfare and the opportunity to in-crease their authority. Durable alliances can also leadto the formation of a tribe (Ferguson 1994, 96ff.).

THE CONSEQUENCES OF WAR

War has a major impact on the social structure, butalso affects other aspects, such as settlement patternsand demography. Casualties in war can lower the sizeof a group, but the assimilation of prisoners of warcan actually increase the population (Vayda 1968,280f.). Warfare often leads to replacement of groups,when defeated groups are forced to flee their terri-tories; this might create unsettled buffer zones be-tween hostile groups. Settlement nucleation is anotherresult of warfare, since larger groups are able to de-fend themselves better, but on the other hand warfaremight also lead to a dispersal of the population, inorder to reduce the risk for each settlement.

The economic consequences of war are enormous,in addition to the loss of life a defeated group mighthave their food stores plundered, livestock stolen andhouses and fields burned to the ground. A successfulraid can increase the wealth of the victor, however,providing moveable valuables and other resources.Warfare has costs in itself, though, such as expensesfor the army’s equipment and supplies, or by requir-ing labour to the construction of fortifications (Fergu-son 1994, 90f.).

The ideology of a society is also affected by war-fare, and psychological accommodations are oftennecessary to accustom people to a regular use of viol-ence. Belligerent societies emphasise martial values,such as bravery in battle, and cultivate personal ag-gression. Warriors usually have a high social statusand might demonstrate their military accomplish-ments by taking war trophies (Ferguson 1990, 44ff.).Warfare is often accompanied by rituals and religioussymbolism, such as the use of magic to weaken theenemy or divining the outcome of a battle. Ritualsare frequently used to maintain the resolve of the war-riors, but are also needed before warriors returningfrom battle can re-enter the society (Ehrenreich 1997,10ff.). These psychological adjustments create anideology that justifies violent conflict and the costs ofwar, and makes war seem ‘‘natural’’ to society (Fergu-son 1994, 98ff.).

A warlike society influences neighbouring societies,forcing them to use violence in order to defend them-selves. The only alternative is to flee the area, andthis is not always a feasible solution, especially foragricultural societies, which depend on their livestock,crops and food stores. Societies with an aggressiveneighbour will have to develop a more efficient mili-tary organization, or be destroyed, thus intensifyingthe warfare in an entire region (Keeley 1996, 127ff.).

The conduct of war also changes when the socialcomplexity increases. Centralized and hierarchical so-cieties have a greater military sophistication and aremore successful in war (Otterbein 1989, 104ff.). Theyuse professional warriors, develop better tactical sys-tems, have a higher subordination and often use ar-mour and shock weapons instead of missile weapons(Otterbein 1989, 73ff.).

THE CAUSES OF WARThe cross-cultural surveys mentioned above clearlydemonstrate that war was common in many primitivesocieties, but they also show that peace was possible.Why do some societies make war, when others donot? What are the causes of war?

A number of popular theories explain warfare as aresult of individual human aggression, postulatingthat all humans are born with an innate ‘‘killer in-stinct’’, which means that aggression and warfare arenatural and unavoidable. This does not explain thegreat variations in how aggression manifests itself, andsocial or cultural influences are not considered (Hol-loway 1967, 33ff.). Cultural values have a great im-pact, however, by selecting for particular personalitytypes or through child rearing patterns. Aggressioncan also be explained using psychological approachesinstead of biology. The frustration-aggression hypoth-esis argues that aggression is always induced by theenvironment, while the displaced aggression hypoth-esis describes how internal conflicts within a groupcan be redirected to external groups (Brothwell 1999,26). Psychological theories are often used implicitly toexplain the motivations for warfare, such as a desireto gain revenge or prestige, but these theories do notexclude other explanations (Ferguson 1984, 14f.).

Sociobiological theories are based on the assump-tion that natural selection takes place between indi-

134 Acta Archaeologica

viduals, not between groups or cultures, and that re-production is as important as survival (Chagnon1990, 78f.). Reproductive success is gained not onlyby having children, but also by helping relatives withsimilar genes (a concept called inclusive fitness). Con-flicts of reproductive interests and competition overresources are inevitable, but striving for prestige andstatus can also result in conflicts, since high esteemusually leads to reproductive success. Conflicts beginat the individual level, but has the potential to esca-late to war between different groups, though hostilit-ies can also be resolved by means other than violence(Chagnon 1990, 93ff.).

Cultural ecology describes how populations adaptto environmental constraints, and resource scarcity isregarded as the primary cause of war. War is part ofa response mechanism in a functional system, whichcan re-establish a balance between population and re-sources, although the functions and consequences ofwar may not be recognized by the individual actor(Ferguson 1984, 28ff.). The ecological theories havebeen reformulated, however, and the functionalmodels are now de-emphasised. Materialist theoriesare based on the premises that the infrastructure hascausal primacy, that selection takes place betweengroups, which means that groups with less efficientmilitary practices may be eliminated, and finally thatwar is motivated by material objectives (Ferguson1990, 28f.). The infrastructure describes a society’senvironment, demography and technology, and thesefactors explain why war occurs and how it is prac-tised. Structural factors, such as kinship patterns,economy and politics, explain the social patterning ofwar (like the military organization) and determineswhy a particular war starts. The superstructure is theperceptions and beliefs of a society, which may re-inforce the warriors’ resolve and make them morewilling to fight, but they are not the actual causes ofwar (Ferguson 1994, 87ff.). The development of morehierarchical societies means that the infrastructuralconstraints are lessened, and structural factors willhave an increasing influence on war (Ferguson 1990,48f.).

Finally, there are researchers who claim that eachwar has its own historical context, and that there areno universal causes of war. The different theories in-dicate some of the factors and conditions which leads

to war however, and further research may demon-strate some of these causes in the archaeological rec-ord from the European Neolithic.

THE ORIGINS OF WARWarfare is a social phenomenon, and leaves only in-direct traces in the archaeological record. The ac-knowledgement of warfare thus depends on the inter-pretation of the archaeological sources. There arethree main sources to demonstrate the existence ofwar: Weapons, fortifications and injuries on skeletons.Weapon traumas are the most direct form of evi-dence, while both offensive and defensive weapons, aswell as fortifications, have been interpreted in manydifferent ways. Another source is iconographic rep-resentations, which might show weapons made frommaterials that are rarely preserved, or even battlescenes, perhaps allowing a glimpse of tactics.

A general problem in the study of prehistoric war-fare is the visibility and preservation of the archae-ological record. A battle will rarely generate any cer-tain material remains, because bodies and weaponsare often removed from the site, or will not be pre-served if they are left on the battlefield (Vencl 1999,69). Most objects of organic materials, such as bows,slings and spear shafts, have disappeared from settle-ments and graves, but it is still important to remem-ber the existence of these perishable objects (Vencl1984, 122ff.).

The earliest signs of human aggression, in the formof traumas, come from the Palaeolithic, but they arefew, scattered and often uncertain (Keeley 1996, 36f.).The oldest recorded case suggestive of interpersonalviolence is a skeleton from Israel (Skhul IX), dated tothe Upper Palaeolithic, which has perimortem in-juries probably inflicted by a spear (Frayer 1997, 183).The earliest evidence of injuries possibly caused bywarfare is from Jebel Sahaba in Sudan. Site 117 is acemetery with 107 burials dated to the Late Palaeo-lithic (12–10,000 B.C.). Weapon traumas and projec-tile points imbedded in, or associated with, the skel-etons suggests that about half the people buried at thesite died a violent death (Wendorf 1968, 992f.).

There is more evidence of mortal injuries causedby violence in the Mesolithic. Likely cases of homicideare known from Teviec in France, where an adult

135Warfare in the European Neolithic

man had two arrowheads imbedded in the spinal col-umn, or from a triple grave on Henriksholm/Bøge-bakken, Denmark, where one male had been killedby a bone point in the throat (Frayer 1997, 183). Thefirst example of what might be a mass murder is the‘‘skull nests’’ from the Ofnet cave in Bavaria, where38 heads had been placed in two pits and heavilystained with red ochre. Women and children consti-tuted most of the individuals and some of the skulls,especially the male, had elliptical holes probablycaused by a blunt weapon. The exact number ofskulls is still under debate, and it is not clear whetherthe heads were placed in the pits on a single occasionor added one at a time. The site has been interpretedas the remains of a massacre, where part of a popula-tion was killed and decapitated (Frayer 1997, 207f.),but the demographic characteristics might also sug-gest a regular burial (Peter-Röcher 2002, 8f.).

Weapons known from the Palaeolithic and theMesolithic are hunting gear, such as spears and bows,or tools, like axes of stone or antler, but such tool-weapons can easily be used in warfare (Chapman1999).

The earliest example of fortifications is from theNear East. Around 7,500 B.C. (in Pre-Pottery Neo-lithic A) the city of Jericho was protected by a rock-cut ditch 9 metres wide and 3 metres deep and a solid1.7 metres wide stonewall, preserved to a height ofup to 4 metres, with a 8.5 metres tall stone tower(Roper 1975, 304ff.). The fortifications of Jerichohave been regarded as the first evidence of warfare inthe world, but the wall has also been interpreted asflood protection (Keeley 1996, 38 note 32). In Europethe earliest fortifications are found in Greece at thebeginning of the 7th millennium B.C., where the Tellof Sesklo was defended by a wall (Höckmann 1990,58).

Iconographic evidence of warfare is known fromeastern Spain, in the form of rock paintings. Thesepaintings have been considered the most substantialevidence for Mesolithic warfare, but they shouldprobably be dated to the Neolithic (Beltran 1982,73f.). Some pictures shows groups of archers attackingeach other, such as in a picture from Les Dogue, Aresdel Maestra (Castellon) where eleven standing archersare being attacked by seventeen running archers,rendered in another style. At a scene from Cueva del

Fig. 2. Neolithic archers. Rock painting from Cueva del Roure,Morella, Spain (Beltran 1982).

Roure, Morella (Castellon) four archers are con-fronted by three others, whose attentions are centredon the leader. One of the four attackers seems to beexecuting a flank attack (Fig. 2). Other pictures showwounded archers or scenes that can be interpreted asexecutions, where a row of archers stand in front ofa wounded or dead person. Bows and arrows are themost common weapons, but javelins are also de-picted. The arrows are rather long, and held in thehand, while the bows are a little shorter than theheight of a man (Beltran 1982, 44ff.).

SKELETONSPerimortem trauma on skeletons is the most directevidence of the consequences of war. Anthropologicalanalyses can indicate which weapon types havecaused the injuries, the location of the wounds canshow how the battle was fought and the frequency ofinjuries can indicate how large a proportion of thepopulation died as a result of warfare. The interpreta-tion of weapon traumas depends largely upon thepreservation of the skeleton, because a mortal blowdoes not necessarily damage the large bones that aremost often preserved (Vencl 1984, 127). Projectiles

136 Acta Archaeologica

often hit the soft part of the body, and will thereforebe found detached among the bones. An arrowheadin a grave might thus represent the cause of death,rather than a gift.

Burials might also show indirect evidence of war-fare. Mass graves containing several individuals aremost likely a result of war or homicide, instead ofepidemic diseases or accidents, especially if one ormore persons have injuries indicating a violent death.Signs of cannibalism and ritual treatment of bodyparts might also be relevant to the study of warfare,since the victims are often provided through war ormurder (Frayer 1997, 181ff.). There might also be alink to rituals connected with warfare (Keeley 1996,103ff.). Finally biological anthropology can provideinformation on demographics and the populationshealth, as well as identify different populations.

EARLY NEOLITHIC (5,500–4,200 B.C.)

Many graves are known from the Linear Pottery cul-ture (LBK), often from regular cemeteries. The pre-dominant burial rite was inhumation, with the corpseplaced in a hocker position, but cremation was alsoused. Only a few injuries have been identified on skel-etons from burial grounds (Petrasch 1999, 507), butseveral mass graves have been found.

In Herxheim near Landau, Germany, excavationshave uncovered a LBK settlement from around 5,000B.C. that was surrounded by two parallel ditches. Theremains of at least 180 individuals were found at thesite, 4% in the village, 32% in the outer ditch and64% in the inner ditch. Only a few individuals havebeen given a regular burial, but many skulls havebeen placed in ‘‘nests’’. The examined skeletons allshow signs of trauma, cutmarks and old healed in-juries (Häussler 1998, 47f.).

In Vaihingen (see Fortifications below) over 100hocker-graves were placed in an old ditch surround-ing a village. In pits between the houses human bonesfrom a more robust population were found. Twophysiologically different populations, buried in differ-ent ways, could well suggest a less than friendly re-lationship between two distinct ethnic groups (Krause1998, 8f.).

A Linear Pottery enclosure from Schletz/Asparn inAustria had a two metre deep ditch in which at least

67 skeletons were found. The skeletons are very frag-mentary and show marks from predators, which indi-cates they must have been lying above ground forseveral months. All the skulls show trauma caused byblows from a stone axe. The massacre is dated to theend of the LBK, and marks the final settlement at thesite (Petrasch 1999, 508).

At the end of the Linear Pottery culture, atTalheim, Kr. Heilbronn, Germany, 34 persons werethrown into a large pit, among them 18 adults (9 menand 7 women) and 16 children/subadults. At least 18individuals have holes in the skull caused by blowsfrom polished adzes and axes, and 10 of these haveseveral fractures. The injuries show that most of thevictims had been struck down from behind, such asan older man who had been hit in the back by anarrow, and a young man who had an arrow pointembedded in the neck. The victims have not beenable to defend themselves, since the normal traumasresulting from close combat, namely injuries on thearms or shoulders, are absent. The sex ratio indicatesthat a normal group was attacked and wiped out(Wahl & König 1987).

Several examples of massacres are thus knownfrom the Linear Pottery culture, but skeletons are alsofound in the ditches of the Kreisgrabenanlage (enclos-ures) from the following Lengyel culture. In a partiallyexcavated ditch at Ruzindol-Borova 10 skeletonswere found. They had all suffered a violent death,and calculations show that the ditch might contain60–70 individuals (Vencl 1999, 64).

MIDDLE NEOLITHIC (4,200–2,800 B.C.)

Interments still dominate, but the burial customs be-come more varied in the Middle Neolithic: Flat orearth graves, common graves in pits (some insidesettlements), long mounds and megalithic tombs arefound throughout the Neolithic cultures of north-western Europe (Whittle 1996, 241ff.). The focus onlarge communal graves, sometimes monumental, andrecurring burials in passage graves is new, but unfor-tunately means that the skeletal material has been dis-turbed and is often in a very fragmentary state (Midg-ley 1992, 451ff.).

Arrowheads embedded in bones are known froman allee couverte at Castellet, France, where an arrow

137Warfare in the European Neolithic

point was embedded in a vertebra, and from the caveof Villevenard, where an arrowhead shows that a per-son had been hit in the stomach (Cordier 1990,464ff.).

In Porsmosen, north of Næstved, Denmark, a 35–40 years old man from the Funnel Beaker culture(TRB) had been hit by bonetipped arrows in theupper jaw and the sternum (Bennike 1985, 110ff.).The arrows must have been fired from a position ob-liquely above the victim, which indicates he was killedin an ambush.

A young man clutching a small child in his armswas found in the ditch surrounding the Stepleton en-closure in Dorset, England. After being shot in theback with an arrow he had fallen forward into theditch, smothering the child beneath him, and bothwere covered by rubble from the burning fortifi-cation. Two other skeletons were only partly coveredby the rubble collapse and show signs of being gnaw-ed by scavengers, while a robust young man was bur-ied in a pit (Mercer 1989b, 8).

Graves from the Michelsberg culture are very rare,but skeletons have been found in ditches from enclos-ures and pits at settlements. The frequency of traumais high, compared to the low number of finds, andinjuries are known from both children and adults,men and women (Nickel 1997, 121). Heidelberg-Handschusheim is a communal grave from the Mich-elsberg culture. In a hollow, at the bottom of a pit,six individuals were found: An adult man and a wo-man, one older man, two children and a baby. In-juries caused by the blunt end of a stone axe werefound on the skulls of four individuals, and the lefthumerus of the adult man also had a wound. Thefind probably represents a family group which wasattacked and killed (Wahl & Höhn 1988, 167ff.).

In a ‘‘Totenhütte’’ at Schönstedt from the Walterni-enburg-Bernburger culture 64 individuals, from allage groups, had been buried. Most were placed inhocker, but two male skeletons were buried differentlyand both showed perimortem fractures on the skull,probably made by a stone axe. Another male skeletonhad a trauma on the left lower arm (Bach & Bach1972, 103f.). In another Totenhütte from Niederbösathree skulls with lethal injures have been found, whilea right humerus from an adult male has an arrowpoint embedded in the bone. The man survived the

wound, however, since the bone shows signs of heal-ing (Feustel & Ulrich 1965, 195ff.).

LATE NEOLITHIC (2,800–2,200 B.C.)

Burial rites in the Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cul-tures were mainly single graves, sometimes undersmall mounds, and often at burial grounds, but re-burial in passage graves still occurs (Probst 1991,398ff.).

A skeleton from the Bell Beaker culture, found inWeimar, Germany, shows fractures from a killingblow to the left parietal bone (Bach 1965, 218ff.).

A young man, from the English Bell Beaker cul-ture, lay in a ditch at Stonehenge. He had been hitby three arrows, from different directions, and had awrist guard on the left forearm (Harrison 1980, 96).At Fengate, England, a grave with four individualsfrom the Peterborough culture was found: A youngwoman, two children and a young man with a leafsh-aped arrowhead embedded between two ribs (Pryor1976, 232f.).

At Vikletice, a burial ground from the CordedWare culture, six skulls have fractures at the left side(Vencl 1999, 72). The skeletal material from the siteshows that young men (15–30 years old) died 15%more frequently than they should have done nat-urally. The most likely explanation for the high mor-tality among young men is warfare (Vencl 1999, 64).

In a tomb at Roaix, in the south of France, morethan 100 persons had received a hasty burial. Bothsexes and all age groups are represented, and the skel-etons were found in anatomical connection, which in-dicates that they were buried at the same time. Manyof the skeletons had arrow points embedded in thebones, suggesting that they were killed in a war (Mills1983, 117).

RITUAL TREATMENT OF SKELETONSThe most common form of what can be termed ‘‘rit-ual behaviour’’ seen on the skeletal material is trepa-nation, where a part of the skull is removed by scrap-ing a hole, or cutting out a disc. Trepanations areknown sporadically from the Mesolithic, but becomemore frequent in the Neolithic. Most trepanatedskulls show signs of healing, indicating that the sur-

138 Acta Archaeologica

vival rate was high (Piggott 1940, 119). A ‘‘real’’trepanation is made on a non-damaged skull, prob-ably because of magical-religious beliefs or as a surgi-cal attempt to ease pains in the head (Grimm 1976,274). Another possibility is that trepanations weredone in order to smooth splintered bone and removebone fragments from a fracture. This interpretation issupported by the fact that most trepanations arefound on male skeletons and on the left side of theskull, i.e. the side where one is hit by a right-handedattacker (Bennike 1985, 98).

Many trepanated skulls have been found in France,where more than 200 trepanations are known fromthe Seine-Oise-Marne culture in the Paris basin.They are found in communal graves in megalithictombs and caves, but many were discovered alreadyin the 19th century and are poorly documented. Theproportion of skeletons with trepanations was veryhigh, however, in some graves almost 8% (Piggott1940, 116). Another concentration of trepanations isfound in Germany. In the Walternienburg-Bernburg-er culture many skulls have trepanations, and 92% ofthese are male skeletons (Probst 1991, 380). Severaltrepanations are also known from the Globular Am-phora and the following Corded Ware culture, againgenerally situated on the left side of the skull (Ullrich1971, 50).

It has been suggested that several Neolithic culturespractised cannibalism. A cave burial from the LinearPottery culture at Jungfernhöhle, by Tiefenellern inGermany, containing 38 women and children, manyof whom have injuries, has been interpreted as proofof human sacrifice and ritual cannibalism (Probst1991, 263f.). At least 44 individuals, which had beencut up and burned, were found in another cave burialat Hohlenstein, Baden-Würtemberg, dated to theRössen culture (Probst 1991, 296). Cutmarks andfractures have also been ascertained on 16 skeletonsfrom the Furfooz cave in Belgium, dated to the Mich-elsberger culture (Probst 1991, 322). The anthropo-logical analyses are not conclusive however, andweapon trauma or cultic manipulation of bodiesmight also cause the fractures found on the above-mentioned sites, perhaps during rituals connected towarfare (Petrasch 1999, 511). Special burials of skulls,known for instance from the Baalberger culture(Probst 1991, 340), are often interpreted as an indi-

cation of ancestral worship, but could also be wartrophies (Keeley 1996, 100).

THE EVIDENCE FROM THE SKELETALMATERIALEven though many fractures and weapon traumas areknown from the Neolithic in northwestern Europe itis very difficult to estimate the frequency of warfare.The palaeopathological literature provides plenty ofindividual cases, but few regional syntheses with aperspective on population (Walker 2001, 584). Thenumber of injuries seems to rise in the Neolithic, how-ever, and traumas are most often seen on male skel-etons (Vencl 1999, 71). This indicates that culture,and not just random accidents, which might be dis-tributed equally among both sexes, conditions the in-juries. Warfare is the most logical explanation, be-cause the ethnographic record shows us that this ismostly a male activity. The frequency of injuries hasonly been calculated for the Linear Pottery culture,where nearly 20% of the skeletal material sufferedfrom trauma (Petrasch 1999, 509). Most of the skel-etons with injuries were found in a few mass graves,so the actual figure might be significantly lower.

Anthropological analyses of trauma can also giveinformation about the character of war. The manfrom Porsmose shows the result of an ambush, butsingle skeletons with injuries, can also represent thevictims of an ambush. The Early Neolithic massgraves often contain many women and children, andthe location of the injuries show that many individualshave been struck down from behind (Wahl & König1987, 175ff.). A similar pattern is seen in the mass-acres described in anthropological sources. Massacresare also known from the later parts of the Neolithic,e.g. the mass grave with more than 100 individualsfrom Roaix, and the number of victims often corre-sponds to the size of an average group or settlement(Keeley 1996, 68f.). The skeletons with trauma inter-preted as evidence for cannibalism could also repre-sent the, perhaps mutilated, victims of a massacre.Regular battles are suggested by the many fracturesand trepanations on the left side of the skull, probablya result of close combat with a right-handed opponent(Bennike 1985, 98).

Injuries are very important to the analysis of Neo-

139Warfare in the European Neolithic

lithic warfare, but it is difficult to estimate the fre-quency of war. Some skeletons showing indications ofa violent death also have older healed wounds, whichtestify that war was not always a unique incident(Wahl & König 1987, 177). Though victims left on abattlefield are hardly ever preserved and it can bevery difficult to detect trauma, the skeletal materialclearly shows that violent conflicts took place in theNeolithic period of northwestern Europe.

WEAPONSWeapons are the most important technological con-dition for war, and the character, distribution and fre-quency of weaponry shows the importance of war-fare. There are two types of weapons: Shock weaponsused in close combat, and missile weapons used at adistance. These weapon types are used differently inbattle, and are therefore an indication of the form ofcombat. In addition to offensive weapon types therewas defensive weaponry, such as armour and shields.Transportation is also of great tactical and strategicimportance: Horses or war chariots can be used inbattle, and increases mobility, while boats, wagons oreven roads facilitate the movement of armies andtheir logistical support.

It can be very difficult to distinguish betweenweapons and tools or hunting gear, which might alsobe used in battle, but cannot be considered properevidence of warfare. Specialized weapons of war area relatively late phenomenon and a result of a stand-ardization in the conduct of warfare and the use ofarmour (Vencl 1999, 65). Weapons can therefore bedivided into the following categories: Tool-weaponsare multi-functional and can be used in both domesticwork and warfare. Weapon-tools have primarily amilitary function, but other uses are possible, whilespecialized weapons are only usable in combat (Chap-man 1999, 103f.).

BOWS AND ARROWS

A bow is actually a piece of highly advanced tech-nology, with very exact properties. The heaviest poss-ible impact, a long range and a flat trajectory aredesirable in both warfare and hunting, and evensimple bows, made of one piece of wood, have a

range of several hundred metres. An arrow has a lowstriking energy, but because it has a relatively highweight and a cutting edge, it makes a deep, openwound, which causes the target to bleed to death(Rausing 1967, 29f.).

Neolithic bows were simple segment bows madefrom the core of yew trees, or from shadow grownelm in Northern Europe. Many longbows are knownfrom the Cortaillod culture in Schwitzerland and thenorth European wetlands, they have a D-formedcross section with a flat back and rounded sides andbelly. The length is around 170 cm, i.e. a little largerthan the average height (Rausing 1967, 132ff.). Theexistence of composite bows, made of layers of horn,wood and sinew, are inferred from a rockcarving ina Corded Ware tomb in Gölitzsch near Merseburg,depicting what is probably an angular non-reflexcomposite bow (Rausing 1967, 38f.).

Complete arrows are very rare, but most of thediscovered arrow shafts are more than 70 cm long(Clark 1963, 72ff.). Many different types of projectilepoints are known from the Neolithic, they are gener-ally made of stone (flint), but bonepoints are alsofound. Transverse arrowheads are found in the west-ern part of the Linear Pottery culture, as well as theFunnel Beaker and the SOM culture. Pointed bifacialpressure-flaked arrowheads are common in theMiddle Neolithic: Triangular points are known fromthe SOM and Altheim cultures for example, and leafor lozenge shaped arrowheads in the Chasseen andWindmill Hill cultures (Clark 1963, 71). In the LateNeolithic the Bell Beaker culture had triangular ar-rowheads, often barbed and tanged, but sometimeshollow-based (Harrison 1980).

Other forms of equipment can also demonstratethe significance of archery. Wrist guards and arrowshaft smoothers are sometimes found in graves fromthe Bell Beaker culture. Wrist guards are often foundtogether with copper daggers, but rarely with arrowpoints (Harrison 1980, 53). The existence of wristguards, which shields the wrist from the lash of thebowstring, was perhaps connected to the use ofpowerful composite bows in the Late Neolithic (Raus-ing 1967, 47). Wrist guards were also used in theMiddle Neolithic, however, and they might also havebeen made of materials such as bone, leather orwood, which are not preserved (Clark 1963, 77).

140 Acta Archaeologica

The distribution of bows and arrows can be an indi-cation of the prevalence of warfare. Arrowheads areonly found in the western part of LBK for instance, butsince hunting was just as rare as in Eastern Europe, thearrows were probably used in warfare (Kruk & Mili-sauskas 1999, 298). It is difficult to determine the func-tion of an arrow based on the shape of the arrowhead,but war points were often barbed or connected to theshaft in such a way that they remained in the woundwhen the arrow was extracted. The popular broad tri-angular arrow points are probably meant for warfarerather than hunting (Keeley 1996, 54ff.).

AXES

Polished flint axes are found during the entire Neo-lithic period and their occurrence in graves andhoards might suggest they also had a symbolic sig-nificance. They were probably tools for woodworking,but perfectly usable in combat (Whittle 1996, 277)and can therefore be considered as tool-weapons.

Bone and antler axes with shafthole and a sharpedge or point were also used in the Neolithic. Theywere tool-weapons used as hoes or weapons of war(Chapman 1999, 109).

Polished stone adzes are known from the LinearPottery culture, in the form of shoe-last adzes and flatadzes. Use-wear analyses show that they were usedfor woodworking, but they could also have been usedin combat (as demonstrated by the Talheim massgrave). Stone axes used as grave goods show that theywere also a status symbol for men (Vencl 1999, 65).Battle-axes in many shapes have been found from thelast part of the Early Neolithic onwards. They usuallyhave one edge, but double-edged axes are alsoknown, while others have a flat or knob-shaped neckusable as a hammer (Zapotocky 1992, 154ff.). Someresearchers believe that battle-axes were ritual orsymbolic objects and not used for practical purposes,because of their small size or slight shafthole. Thevariation in size is the same as ordinary Iron age axes,and the shafthole is not any narrower than that onantler axes from the Mesolithic. There is a group ofminiature battle-axes however, that can only havehad a symbolic or ritual function. The great morpho-logical variation and the elaborate edges indicate thatstone battle-axes were weapon-tools, or weapons,

while the hammeraxes likely were tool-weapons. Afew finds suggest that the battle-axes had 50–60 cmlong shafts, and they were probably held in one hand.The edge was not sharp enough to cut, so the battle-axes were likely used as a crushing weapon (Zapo-tocky 1992, 158ff.).

Copper axes are known from the Middle Neolithic,in the Funnel Beaker culture for instance, and battle-axes made of copper (so-called ‘‘Hammeräxte’’) havebeen found on sites from the Altheim culture, whileothers probably belong to the Corded Ware culture(Müller-Karpe 1974, 234f.). Copper axes from south-eastern Europe are the most likely models for manybattle axe types. The solid copper axes can be de-scribed as tool-weapons, since some have use-wearfrom woodworking or mining, but their greater valueand weight makes it improbable that they were notused in combat like the stone axes (Chapman 1999,111).

MACES

The simple wooden club is probably one of mankind’soldest weapons, but they are rarely preserved. Polish-ed stone maceheads with a drilled shafthole areknown from the Early Neolithic onwards, but theyare most common in the Corded Ware culture, wherethey are round, with a smooth surface and a conicalshafthole (Bekova-Berounska 1989, 219ff.). Stonemaces can be considered the first specialized weapon,or perhaps a weapon-tool, but other uses than combatis hard to imagine. A mace is a crushing weapon, andthe small maceheads might have been used to finishoff a wounded enemy (Chapman 1999, 110f.).

SPEARS

A spear is a very effective weapon that can be usedboth in a melee and at a distance. Spear points arerelatively rare in most of the Neolithic period, butspears made entirely of wood might have been used(Vencl 1979, 688f.). Wooden spears have been foundin Switzerland, while a 1,85 m long pointed spearmade of hazel was found in Somerset, England(Green 1980, 170).

Flint points weighing more than ten grams wereprobably meant for spears rather than arrows (Raus-

141Warfare in the European Neolithic

ing 1967, 164). Examples might be the large leafshap-ed points (up to 10 cm long) from England or fromthe Altheim culture. Bifacial pressure-flaked flintpo-ints, which can also be interpreted as spears, arefound in several Middle Neolithic cultures. Longblades are known from the SOM culture, but theycould also have been used as daggers (Howell 1983,71). Spears become much more common in the LateNeolithic, where they are found in the Corded Wareculture, for instance (Müller-Karpe 1974, 233). In theMiddle Neolithic copper spear points were used insoutheastern Europe, at the same time as points madeof stone and bone, which can be considered lower-status imitations of the metal weapons (Chapman1999, 128ff.).

DAGGERS

Knives made of flint and bone are known from theentire Neolithic period, but daggers are relatively late.Blades of Grand-Pressigny flint are known from theSOM culture (Howell 1983, 71), while pressure-flakedflint daggers are known from the end of the Late Neo-lithic in Denmark and England (Harrison 1980, 103).

Daggers have the widest distribution in the CordedWare and the Bell Beaker cultures, where they aremade of flint or copper. In the Globular Amphoraand the Corded Ware cultures leafshaped rivettedcopper daggers are found in hoards, often with battle-axes (Müller-Karpe 1974, 237). Daggers are espe-cially known from the Bell Beaker culture where tang-ed flat copper knives, sometimes with rivet holes, arefound as grave goods (Müller-Karpe 1974, 237).

DEFENSIVE WEAPONS

Only one defensive weapon is known from the Neo-lithic, a wooden shield from a Late Neolithic Globu-lar Amphora tumulus in Langeneichstädt, Kr. Quer-furt, Germany (Vencl 1999, 66). The earliest forms ofarmour were probably just reinforced clothing, usingseveral layers of covering or stiff leather. Shields couldhave been made of wood, either solid or a frame ofwood covered with leather. Such types of defensivearmour are made of organic materials and havetherefore disappeared from the archaeological record(Vencl 1979, 692). Armour, shields and helmets are

fully developed in the Bronze Age, however, so primi-tive versions have probably existed in the Late Neo-lithic, if not before.

TRANSPORTATION

According to some researchers the horse was domesti-cated on the Pontic steppes around 4,000 B.C., basedon the appearance of wear traces on horseteeth (An-thony & Brown 1991, 35f.). The evidence is not con-clusive, however, and the date still under debate. Theuse of horses is often connected to a pastoral subsist-ence strategy, but they are also of great military im-portance. Horses provide tactical manoeuvrabilityand allows rapid surprise attacks and raids at a longerdistance. The use of horses would therefore have hada profound influence on warfare in the Neolithic, butthere is no decisive evidence for a military use ofhorses or the appearance of mounted warlike pastor-alists (Chapman 1999, 134ff.). The Globular Am-phora culture and other Late Neolithic cultures mighthave used horses, and horse burials are known fromthe Corded Ware culture in Poland (Kruk & Mili-sauskas 1999, 339).

The use of wagons is indicated by double burialsof cattle (probably draft animals), clay models andpictures of wagons from the Middle Neolithic, butthe earliest wagon parts are from the Late Neolithic(Sherratt 1981, 263ff.). Parts of two-wheeled vehicleswith wooden wheels have been found in Holland,Denmark and Germany. These carts were likely pull-ed by oxen and were very slow (Kruk & Milisauskas1999, 322f.), but they could have been logistically im-portant during raids. The use of wagons is also sug-gested by the presence of roads built through bogareas, such as a one kilometre long and four metreswide track way built of wood in Meerhusener Moorin Niedersachsen, Germany (Probst 1991, 239f.). Fi-nally dug-out boats could have provided transpor-tation along rivers or coasts, and allowed an attackingforce to carry more supplies, thus increasing its effec-tive range, and to transport more plunder.

THE IMPORTANCE OF WEAPONSWeaponry in the Early Neolithic can, as mentioned,be described as tool-weapons, which were primarily

142 Acta Archaeologica

used for woodworking or hunting. The bow was themost sophisticated weapon, and ranged combat prob-ably dominated. In due time specialized battle-axesand maces were developed, showing that close com-bat was now perhaps of greater importance, and thatthe intensity of conflicts increased. Shock weapons arevery effective, but they also put the wielder in greatrisk of being killed or wounded. In the Late Neolithicthe number of burials containing battle-axes rises dra-matically, probably corresponding to an increase inwarfare (Kruk & Milisauskas 1999, 328ff.). Othermelee weapons, such as spears with a flintpoint anddaggers, are also commonly found, and the develop-ment of protective armour might have started in thisperiod. The dagger could have been used to delivera coup-de-grace to a wounded enemy, and might in-dicate that warfare had become more deadly. An-other interpretation might be that warfare becamemore ritualised, since the use of a dagger would haverequired an extremely close fighting situation. Thebow dominates again in the Bell Beaker culture,where wrist guards and arrowheads in the gravesshow its importance.

The use of weapons as grave goods appears to havebeen mainly symbolic, and weapon sets cannot be in-ferred from the burial data, but weapons were clearlyseen as status symbols. Stone axes and adzes arefound in male graves as early as the Linear Potteryculture (Whittle 1996, 173), and they are prevalent inthe Corded Ware culture. In the last part of the LateNeolithic the battle-axe was replaced by the daggeras the main status symbol (Harrison 1980, 37). Thesymbolic nature of buried weaponry has led to theconclusion, that they had no practical function what-soever. Maces for example are described as symbolsof power, rather than weapons (Dolukhanov 1999,82), and copper axes as a form of money. The sym-bolic importance of weapons must have a reason,however, and the most likely explanation is their usein warfare.

ENCLOSURESFortified sites indicate the need to defend against en-emies, and therefore demonstrate the importance ofwarfare. This type of Neolithic structure has manyterms (enclosures in English, Einhegungen in German

and enceinte in French), but not all enclosures aredefensive in nature. Fortifications can be either forti-fied settlements or refuges without occupation, butenclosed sites also include structures with other func-tions, such as folds for animals, ritual centres or cen-tral assembly places. Defended sites provide evidenceof many different aspects of Neolithic warfare. Thecharacter of the defensive structures and the topo-graphical placement of the sites might indicate theirdefensive or offensive significance as well as the re-lation to important resources, and lines of communi-cation can possibly show the strategic importance.The co-operation necessary to build large-scale forti-fications also provides evidence about the structure ofsociety.

EARLY NEOLITHIC (5,500–4,200 B.C.)

The first farming settlements in northwestern Europebelong to the Linearbandkeramik (LBK) Culture(5,500–5,000 B.C.), which settled on the loess soilsfrom southeastern Europe to the Rhine. In the begin-ning the enclosures consisted of a single rectilinearditch, like Eilsleben in the northern Harz, Germany(Höckmann 1990, 67). From the later phases of LBKseveral enclosures are known (60 according toHöckmann 1990), and they are usually placed promi-nently, such as on promontories near several settle-ments. The enclosures are surrounded by a palisadefence and a ditch (V-shaped, pointed or flat-bottom-ed). They are often rounded and the size is usually 1hectare, but larger enclosures are known (Andersen1997, 174). Some of the structures surround houses,while others have no occupation (Keeley & Cahen1989, 158).

In Vaihingen an der Entz parts of a fortified settle-ment have been excavated. In the first phase thesettlement was composed of several houses, but laterone to two palisades and a flat-bottomed ditch (1.5–2.5 m wide and 1–1.3 m deep) surrounded an area ofnearly two hectares. The ditch lay open in one or twogenerations before it was reused as a burial ground(see Skeletons) (Krause 1998, 6ff.).

Darion in Belgium is a similar enclosure from lateLBK (Fig. 3). The oval enclosure consists of a seriesof interrupted pointed ditches (1.5–2.5 m deep) infront of a palisade (in some places a double palisade),

144 Acta Archaeologica

and surrounding four Linear Pottery houses. In thesouthern end a ‘‘baffled’’ gate protects an opening,and in the northern end a rectangular structure mightbe interpreted as a tower. Darion is 1.6 hectare large,but the northern part seems to have been used forpasture (Keeley & Cahen 1989, 160ff.).

On the Aldenhovener Platte several settlementclusters, as well as nine enclosures, has been un-covered. Langweiler 8 for instance had three concen-tric ditches, while Langweiler 9 consisted of a singleditch interrupted by three entrances (Whittle 1996,174). The sites had no traces of palisades or occu-pation, but small vertical stakes in the bottom of someof the ditches might represent sharpened stakes usedas a form of defence (Modderman 1988, 103).

Köln-Lindenthal from the last part of the LBK Cul-ture consists of a sequence of enclosures, among thema large enclosure with a more than one metre deepditch and a palisade, and a smaller enclosure sur-rounded by a pointed ditch. More than 30 houses havebeen found at the site, which also had open areas(Probst 1991, 254), but the occupation phases mightnot be contemporary with the defensive structures.

Today the Linear Pottery sites are usually regardedas cult places, contrary to earlier interpretations asanimal pens or fortifications (Andersen 1997, 177).The use of the LBK enclosures as fortifications mightbe supported by their distribution, however, sincemost enclosures are found in the western parts of theculture and along the limits of the LBK settlementzone. This suggests that the enclosures were build asa defence against the Mesolithic hunters living be-yond the loess soils. In Belgium there is also a no-man’s land between the Mesolithic and the LBKsettlement, even in areas where there were no geo-graphic barriers (Keeley 1997, 306ff.). The criticalsituation is noted at the Oleye enclosure, in the samearea, where the first Neolithic settlement was de-stroyed by fire, and subsequent houses were sur-rounded by a ditch and a palisade (Keeley & Cahen1989, 164f.). Several facts thus suggest that the re-lations between the western part of LBK and the localhunter-gatherers were less than peaceful.

In the last part of the LBK, around 5,000 B.C., theculture dissipates into several local groups, such asLengyel in the eastern part of central Europe, Stich-bandkeramik in parts of Germany and Poland as well

as Hinkelstein and Grossgartach near the Rhine.These groups are superseded by, for example, Rössenin Germany and Cerny in northern France (Whittle1996, 177).

A number of characteristic enclosures are found inthe Stichbandkeramik and Early Lengyel cultures. A‘‘Kreisgrabenanlage’’ or ‘‘Rondel’’ has up to threeconcentric circular ditches and palisades, and usuallyfour symmetrically placed entrances (Andersen 1997,155). The ditches are often pointed, about one metredeep and one to ten metres wide (Petrasch 1990,449ff.). Sometimes the entrances are marked by acurve in the ditches, seen for example at Svodin inSlovakia, or they are connected by a trench, as atKünzing-Unterberg in Bavaria. The larger structureshave a higher number of ditches and palisades. Atsome sites the material from the ditches have formeda rampart behind a palisade, but at Svodin the soillay between a triple palisade, thus forming a fourmetres high and eight metres wide wall (Petrasch1990, 473ff.). The enclosures are placed in the samelocations as ordinary settlements, but they show nosigns of occupation. The ‘‘Kreisgrabenanlage’’ areusually interpreted as religious or political centres (Pe-trasch 1990, 512f.).

Enclosures are also known from the latest part ofthe Early Neolithic in France and Germany. Theyare often oval or circular in shape, with a ditch andsometimes a palisade, but generally without traces ofoccupation. Causewayed ditches begin to appear andsome enclosures are now positioned in high, con-spicuous places. Barry-au-Bac in the northeasternFrance was a circular earthwork with a diameter of140 metres, it had a shallow ditch in front of a pali-sade, probably with a rampart behind. The only en-trance was one metre wide, and four timber buildingswere found in the interior (Ilett 1983, 29f.). Fortifiedsettlements are also known from the Rössen culture.A settlement at Goldberg in Baden-Württemberg wasfortified on the approachable western side with aditch and a palisade, but the site was destroyed by aconflagration (Probst 1991, 293).

MIDDLE NEOLITHIC (4,200–2,800 B.C.)

Middle Neolithic enclosures are known from severaldifferent cultures all over northwestern Europe, such

145Warfare in the European Neolithic

as Chasseen in France, Michelsberg in the westernparts of Germany and the Funnel Beaker culture inGermany and Poland. Agriculture also spread to theBritish Isles and Scandinavia in this period, whereenclosures are known from the Windmill Hill and Fu-nnel Beaker cultures respectively (Andersen 1997,183).

Many enclosures are found in the western part ofFrance, belonging to the Chasseen culture and itsmany local variations (especially the Matignon andPeu-Richardien groups, 3,800–2,900 B.C.). The en-closures are often of considerable size, with one to fivecausewayed ditches and sometimes a rampart, wall orpalisade. The shape is circular or semicircular and thesize ranges from one to nine hectares. The enclosuresare sometimes placed very close together, often nearwetlands or on neighbouring hills. The most commonform of enclosure is characterized by a special type ofgate with a protective outwork called ‘‘pince de crab-be’’, seen for example at Chez-Reine, Semussac (Fig.4) (Andersen 1997, 233ff.). Another type of enclosureis Champ Durand, which had three causewayed dit-ches. The innermost ditch was rock-cut, five metreswide and 2.5 metres deep, while the other ditcheswere successively smaller. Dry-stone foundations sug-gest there might have been stone walls and a stonetower, while postholes indicate substantial timberconstructions at the gate (Scarre 1983, 254ff.).

In eastern France enclosures are known from theNMB culture (Neolithique Moyen Bourgignon,3,800–3,400 B.C.). The enclosed sites are oftenlocated on high ground, and typically consist of astone rampart and a ditch, which cut off a promon-tory. Some of the sites were possibly occupied, whileothers were refuges (Andersen 1997, 216f.).

Similar enclosures are also found in southernFrance, while the Fontbouisse culture built enclosuressurrounded by stone walls with circular towers (And-ersen 1997, 143). Boussargues in Herault was 30 m x45 m and had six circular bastions attached to thedry-stone enclosure wall. The site was located on aprominent topographical position (Mills 1983, 121ff.).

The many enclosures belonging to the Michelsbergculture (4,300–3,400 B.C.) were located on slopingground, on plateaus or beside rivers. The form wasoval or curved, with one side protected by the localtopography. The size was typically 5–5.75 hectares,

Fig. 4. Chez Reine from France, with outworks protecting the gates(Scarre 1983, 255).

but both smaller and much larger enclosures areknown (Andersen 1997, 185ff.). The sites were sur-rounded by a palisade and up to five causewayed dit-ches, both elements can be found separately or incombination (Eckert 1990, 408). Ramparts were rare,but the palisades were of considerable size, with postsup to 85 cm in diameter and a height of five or sixmetres (Andersen 1997, 196f.). Urmitz is a large semi-circular enclosure beside the Rhine. It was composedof two causewayed ditches and a single palisade, per-haps constructed in several phases (Eckert 1990, 402).Ten bastions, i.e. small projecting passageways or rec-tangular enclosures, were found at the causeways ofthe innermost ditch. They might have served as extraprotection of the gate or have been used for specialactivities, and are also known from several otherMichelsberg enclosures (Andersen 1997, 198).

East of the Michelsberg culture, in Germany andPoland, there were several different subgroups of theFunnel Beaker culture (TRB), many of which had en-closures. Fortified sites located on high ground are

146 Acta Archaeologica

called Höhensiedlungen, but the term includes bothnormal and fortified settlements (Midgley 1992,346f.). In the Elbe-Saale area, for example, 20–30%of the settlements are fortified (Kruk & Milisauskas1993, 314). The enclosure Dölauer Heide near Halleprobably belongs to the Baalberger culture (4,200–3,500 B.C.), and lay on a high plateau like most en-closures from this culture (Fig. 5). Up to six ditchesand ramparts in front of a single palisade enclosed anarea of 25 hectare. Only three gateways provided ac-cess to the interior, which unfortunately has not beenexcavated, so the function of the site is not known(Andersen 1997, 208). Altheim is a 0.24 hectare largeenclosure from the Altheim culture in southern Ger-many (3,800–3,400 B.C.), with three ditches, a pali-sade and two entrances. In the up to five metres wideand 2 metres deep ditches broken pottery, 174 arrowpoints and at least twenty skeletons were found. Thefinds are interpreted as sacrifices at a cult site or asthe traces of a battle (Petrasch 1999, 505f.).

In the Alps several different cultures, like Cortaillodin Switzerland for example, were contemporary withMichelsberg. Large fortified sites are unknown, butsmall settlements near lakes or wetlands were oftenbuilt on piles and surrounded by palisades (Probst1991, 476ff.).

Enclosures and Höhensiedlungen continued to bebuilt in the last part of the Middle Neolithic, and areknown from the Wartberg, Chamer and Walternien-burg-Bernburger cultures for example. The sites wereoften settlements located on high ground, with up tofive parallel ditches and a palisade. The form variesand often depends on the local topography (Probst1991, 368ff.). Enclosures with no traces of occupationare also found, like Calden from the Wartberg cul-ture, which had two ditches and two palisades enclos-ing an area of 14 hectare. There were seven gateways,but two were blocked by projecting bastions (Fig. 6)(Andersen 1997, 204ff.). The enclosures from theWalternienburg-Bernburger culture were smaller (upto 3.5 hectares), but varied greatly in form and con-struction. Langer Berg, for example, was an oval en-closure with a palisade and a ditch. The palisade wasdouble on one side, forming a 35 metres long en-trance passage (Andersen 1997, 213ff.).

The northern part of the TRB culture also beganto construct enclosures with causewayed ditches and

palisades. They were placed on hilltops or promon-tories, like Sarup on Funen, Denmark, often close towetlands. Objects found at the sites seem to havebeen specially selected and suggest that the sites wereused for rituals (Andersen 1997, 270ff.). Recent findsindicate that a second generation of enclosures wereconstructed in the late Funnel Beaker culture and theBattleaxe Culture. These enclosed sites consisted ofsingle or multiple palisades, but lack ditches. Thepalisade enclosures probably had multiple functions,including defence, ritual activity and axe production(Svensson 2002, 45ff.).

In England 63 enclosures are known from theWindmill Hill culture, most from the southern partsof the country. These sites generally have up to fourcausewayed ditches and are placed in prominent posi-tions relative to the local topography (Andersen 1997,244ff.). At Hambledon Hill in Dorset several enclos-ures have been excavated, the main enclosure waslocated on the top of the hill and had a causewayedditch surrounding an area of nine hectares (Fig. 7).The occurrence of burials and prestige objects sug-gests that this enclosure served as a cult place. At thesoutheastern spur of the hill was the Stepleton enclos-ure, which covered one hectare and was almost circu-lar. Stepleton had a 1.5 metres deep causewayed ditchand a rampart encased in a timber framework, nobuildings were discovered in the interior, thoughdomestic rubbish suggests it was occupied. The sitewas still in use when the fortifications were greatlyenhanced. The whole hilltop of Hambledon, an areaof 60 hectares, was enclosed by a causewayed ditchand a rampart revetted with timber. Later two lesserditches and a rampart were added on the south side,where the hill was most easily approached. In spite ofthese massive fortifications the site seems to have beenattacked, and at least 120 metres of the timberworkson the rampart were destroyed in a conflagration(Mercer 1989b, 6ff.) (see also Middle Neolithic skel-etons). Crickley Hill, a small enclosure near Chelten-ham, had a causewayed ditch and a low bank with apalisade behind (during one phase). More than 400arrow points were found at the site, and their distri-bution indicates that archers attacked the enclosure(Fig. 8). Concentrations of arrow points were foundnear the entrances and along the palisade, whichseems to have been used as a breastwork (Dixon

147Warfare in the European Neolithic

Fig. 5. Dölauer Heide near Halle, Germany (Andersen 1997, 209).

148 Acta Archaeologica

Fig. 6. Bastion at the Calden enclosure near Kassel, Germany (redrawn from Andersen 1997, 204).

1988, 82). Carn Brae in Cornwall was a small 1-hec-tare enclosure, surrounded by a greater enclosurecomposed of a ditch and a stone revetted rampartwith complex gates (six hectares). The inner enclosurehad a more than two metres high stone wall, built ofmassive boulders, and housed a small settlement.Carn Brae was destroyed in a fire and at least 800arrow heads left on the site suggest it was attacked bya large force of archers (Mercer 1989b, 2ff.).

LATE NEOLITHIC (2,800–2,200 B.C.)

The construction of enclosures almost ceased in thenorthwestern parts of Europe during the Late Neo-lithic. The settlement pattern changed and theCorded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures are character-ized by small and dispersed settlements (Starling1985, 34f.). Enclosures continued to be built in Eng-land, however, in the form of so-called Henge Monu-ments, which were circular structures composed ofditches and timber posts or stones (like Stonehenge)

(Andersen 1997, 265f.). In the Mediterranean smallenclosures with stone walls and bastions were con-structed up until 2,000 B.C. (Andersen 1997, 145).

THE FUNCTION OF ENCLOSED SITESEnclosures have been interpreted as refuges, fortifiedsettlements, corrals (so-called kraals) or centres usedfor ceremonial, social or economic activities. Todaymost enclosures are regarded as cult sites, on accountof the finds of pottery and parts of skeletons in theditches. It is also claimed that the sites have no tracesof proper occupation and that the physical barriersdid not have a defensive function (Andersen 1997,301ff., Whittle 1996, 266ff.).

There are two types of enclosures: Fortified settle-ments and enclosures without occupation. Housesand settlement waste has been found at many sites,but it can be difficult to ascertain that the settlementand defensive structures are contemporary. There areseveral examples of regular fortified settlements, how-

149Warfare in the European Neolithic

Fig. 7. Hambledon Hill in Dorset, with reconstruction of the Stepleton enclosure (redrawn from Andersen 1997, 245).

ever (some of which have been mentioned above), butditches and palisades can also be a symbolic markingof the settlement, rather than a defensive structure,and are therefore not irrefutable proof of warfare(Chapman 1999, 107). It is even more difficult to de-termine the function of enclosures with no trace ofoccupation. Kraals are often used to protect animalsfrom being stolen, and thus might be an indication ofraiding (Modderman 1988, 103), but the often verycomplex structures contradict an interpretation ascorrals (Keeley & Cahen 1989, 170). The interpreta-tion of the enclosures as central assembly places orceremonial sites is supported by the fact that someenclosures seem to have had no defensive function,like the Langweiler sites which only had a single ditch,or Kreisgrabenanlage without palisades. At someMiddle Neolithic sites the ditches seem to have beendeliberately refilled (Andersen 1997, 287f.), which ex-cludes that the ditch had a defensive function andthe existence of a rampart. But is it really possible todetermine whether 5–6,000 year old ditches have

been refilled immediately or after a few years? Thespecially selected objects and the many causeways arealso traits, which have been used as arguments againsta defensive function, but some of the causeways arenot entrances, since there is no opening in the pali-sade behind the ditch (seen for example at Urmitz).Objects found in the ditches have often been de-posited after the construction, and therefore do notnecessarily reflect the original function of the site.

One of the major problems with the interpretationof the Neolithic enclosures is that the same model isused on a large and very diverse group of sites. It istherefore more appropriate to examine which fea-tures might be of defensive importance, rather thandiscuss whether the enclosures were exclusively forritual activities or fortifications.

Fortifications are composed of three elements: Aditch, a rampart and a palisade or wall, either separ-ately or in combination. Several consecutive barrierscan be termed a ‘‘defence in depth’’ (Mercer 1989a,16f.). The palisade probably had the greatest distri-

150 Acta Archaeologica

Fig. 8. Distribution of arrows at Crickley Hill (redrawn from Dixon 1988, 83).

bution and importance in the Neolithic, ramparts arefound at many sites while stone walls are very rare.Ditches alone do not protect the defender from miss-ile attacks, but they can slow down a charge.

Fortifications can be characterized by the followingfeatures: Traces of fighting, such as weapons, fire, orsigns of destruction. The presence of entrances, whichrestricts and controls access to the interior. Multipli-cation of defensive barriers, especially at vulnerableplaces, which reveals a concept of defence in depth.Protection of the palisade or wall by flanking towersor bastions. Placement at inaccessible locations witha good view (Vencl 1999, 68f.).

Weapons are rarely found at enclosures, apart from

the arrowheads found at some English enclosures, butsigns of destruction are known from several sites,Goldberg and Stepleton for example. The weakestpoint in a fortification is the entrance, and severalNeolithic enclosures have elaborate gate construc-tions, such as an extra palisade which shields the en-trance (as at Darion and Langer Berg) or the protec-tive outworks, called ‘‘pince de crabbe’’, found on theMiddle Neolithic enclosures in France. A defence indepth is known from many enclosures, such as the sixditches at one side of Dölauer Heide (Fig. 5). Thistype of barrier delays the enemy and keeps them in a‘‘killing zone’’, where the defenders may dispatchthem with missile fire before they reach the palisade

151Warfare in the European Neolithic