Wanderlust - Davidson College

Transcript of Wanderlust - Davidson College

Lhere is a feeling--a tangle of nerves and anxiety fighting a losing battle against excitement--that surfaces the moment you first truly realize your journey is about to begin. Perhaps that moment occurs when you receive a required vaccination, snap a passport photo, say goodbye to your family, or at last when you step aboard the plane. In this moment, you take a breath, release your last holds to home, familiarity, predictability and go.

Six days, six weeks, or six months later, another feeling no less powerful and all the more conflicting arises. Going home--something that always seemed so distant for so long--at last seems to be upon you. The thought is both thrilling and terrifying. Now that you’ve seen, tasted, smelled another world, you can’t help but wonder if you can survive--thrive--in what was originally your standard of familiar, comfortable. In this moment, “home” becomes a slightly foreign place. Home will never be the same because of all of the new experiences you’ve had, adventures you’ve gone on, and people you’ve met.

Wanderlust is about reliving your journeys, vicariously tagging along for those of others, and inspiring new ones in the future. It gives us the chance to think about what travel means and how it affects us, the thrilling and wondrous parts as well as the slightly terrifying or overwhelming or heartbreaking parts. It gives us the chance to reflect on what is important to us and learn what is important to others. It is a building of connections and a building of relationships, something that is celebrated in the writings and artwork of Davidson student travelers.

Laura Chuckray and Whitley RaneyWanderlust Editors 2013

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Bill Giduz and Shireen Campbell for their help with judging our entries and choosing winners. Thank you for the support of Dean Rusk Student Advisory Committee and the student travelers.

T

Letter from the editors:

Contributors:Olivia Brown

Katie Voegtli

Chai Lu Bohannan

Stephanie Hunt

Ivana Masimore

Tim Rauen

Claire McDonald

Andrea Becerra

Catherine Wu

Jessie Blount

Rosie Kosinski

Valerie Slade

Ashley Parker

Madison Rogas

Anna Elizabeth Ike

Hannah Schorr

Aly Dove

Jordan Luebkemann

Lee Crittenberger

Christine Bell

Allan Spiegel

Rosie Kosinski, Petra, JordanCover: Aly Dove,

Preikestolen, Norway

B 5

Rosie Kosinski, East Jersalem, Palestine/Israel

through the BattLefieLd ~Tim Rauen~

rom the Marriot brochure,

Where Caribbean zephyrs sway

The rubbery, synthetic-seeming palms;

Where pretty tides never offer

Their jellyfish to pretty sands;

Where all the women are attractive, despite

Their cellulite and freedom of undress;

The tourist district spits out

The highway

Runs breathlessly, lofted

Over clay roof prairies and satellite dishes,

Cleaves the ribcage of a mountain

Shorn and tiered by dynamite.

The valley belongs to the cell towers

And the relay stations

And the power lines that pry open the green horizon.

The highway goes and goes, deep

Into the Other as it can reach

And there are no exits, no matter what

The signs say

Welcome to the capillaries.

Green and tangerine adobe

Pixilate the patchwork-frescoed barrio

Beneath black mold and lichen

And another man’s treasure or kindling.

Rust grows on tin roofs and weather vanes

A mustang graveyard guards the gap-toothed skulls

Of the Marriot brochure writers

And their paradise becoming more and more unreal.

Opposite contagions, man and un-

Man, struggle to overgrow the other

In a warzone

A thin film of garbage holds back the jungle.

Vines and power lines crisscross the canopy

Of a landscape in virile disrepair.

Cows graze in a hauled-out quarry,

One brushstroke each.

Green is.

Up the mountain, higher, higher, houses

On stilts huddle near the roadway

As the earth erodes beneath them,

Sculpting a lush and craggy vista,

And finally, the Arecibo telescope transcends

The tree line, aimed Godward.

Contest Winner: #1

F

4

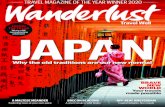

T imono-clad ladies flutter around me.

Flitting among bowls, caddies, and whisks, they prepare for Japan’s most elaborate cultural performance—sado. Often called tea ceremony but better translated as the Way of Tea, sado entered Japan from China during the ninth century. The ritual spread from monks to warriors and finally to the entire nation. Today, natives and tourists savor the traditional taste of sado.

Well-prepped by my Japanese host mother, I am about to attend a summertime sadoōat the teahouse of Kennin-ji. The oldest Zen temple in Kyoto, Kennin-ji lies at the heart of the historic Gion district. While reflecting the Buddhist roots of sado, this venue also toasts Gion Matsuri, a religious festival that rouses Gion with lipstick-red lanterns and takoyaki-eating crowds.

I just caught a backstage sado, before being ushered to the front entrance of the teahouse. Bending low, I scoot through the hobbit-hole that presses all guests to shed their social distinctions as they enter the moment of tea. This moment transpires in a room that exemplifies the wabi-sabi aesthetic. Bare plaster walls, curtain-free windows, floor uncluttered by furniture. Insisting upon the acceptance of transience and imperfection, wabi-sabi exalts the simple, modest, and austere.

Still on my knees, I bow, bending the waist as I press my hands into the tatami mat before me. Encased in a summer-blue kimono, I carefully cross to the alcove at the far side of the room. Kneeling again, I bow before a hanging scroll, then lean forward to admire ragged streaks of ink that delineate the Japanese character for “God.” Above floats a smoky mountain, below the red

splash of a parade float. I bow again, then pivot to face the flower arrangement. A single hiougi sprig tips towards me. The prized flower of Gion Matsuri, it flushes fair as a geisha.

Pressing back into my heels, I rise to join the L-shaped line of guests. We sit in the seiza posture, thighs folded over calves and seat-bones resting on heels. After a few still moments, the teisyu (hostess) enters. Her back curls, and her hair frizzles. Still, she kneels before the low table by the wall with the poise of an priestess. Her piano-player hands glide over the tea articles as she begins to heat water. Another kimono drifts into the room, bearing a gold-rimmed bowl of wagashi (Japanese confectionery).

When my neighbor to the right passes the bowl, we exchange bows. Thank you. Turning to left, I bow again. Thank you for letting me go first. After these silent niceties, I remove a delicate sheet of kaishi (pocket paper) from my purse. I serve myself a cube of clear jelly, speckled with sweetened beans. This summer sweet evokes a cool, pebble-studded stream, which I slice with my kasikiri (sweet cutter). After sliding the jelly-bites into my mouth, I daintily wipe my kasikiri with the corner of my kaishi. I slip them both back into my purse.

As the empty wagashi bowl floats away, the teisyu prepares the first cup of tea. She scoops matcha (green tea powder) into a cup. She ladles in hot water. She whisks the two together. Simple actions, performed with a fencer’s finesse. The most honored guest receives the first cup, but my own soon appears. I bow my thanks before lifting the cup. I twist it clockwise twice, so as not to dirty the front, then raise the foamy brew to my lips. My tongue curls. The wagashi’s sweetness only enhances the matcha’s bitterness. Sweet and bitter; sad celebrates both in their most potent forms.

I finish in three long sips, then join the other guests in cup-ogling. My fingertips travel over the pottery’s uneven terrain. Again, the wabi-sabi aesthetic prompts me to cherish life’s unpolished wonders.

The kimonos flutter in, flutter out. The Moment of Tea has ended. As the tea master Sen no Rikyu once said, Ichi-go, ichi-e.

Treasure each meeting. It will never come again.

Contest Winner: #2

the Way of tea ~Katie Voegtli~

K

6 7

Rosie Kosinski, Temple Mount, Jersalem, Israel, first place

Chave to say that I am truly in love with Paris! Out of all the cities I have visited thus far, I must say that Paris is one of the most culturally dense. There were so many attractions and sights to see and do. I sadly did not get to cover everything; however, it would be amazing to go back and pick up where I left off. I went on this trip alone, but I had an amazing time meeting new people and exploring the city. But...get this, since my visa was scheduled for at least six months, I got into everywhere, minus climbing the Eiffel Tower, for free! How awesome is that! The Louvre, the Palace of Versailles, and the list goes on and on. I visited the ancient catacombs, which was a fulfilling yet eerie experience, being underground in a dark, damp tunnel surrounded by thousands of bones and various inscriptions (none of which I actually understood). My visit to the annual Salon du Chocolat was even more gratifying. There were various performances and modeling (in outfits made of chocolate, of course) and the best part...LOADS OF CHOCOLATE! Now, I’m a big chocolate lover, so this festival was literally heaven on earth for me. My dentist wouldn’t be so happy about it but boy did I sample. Every booth had hundreds of different kinds of luscious goodness to try and buy. Even to my surprise, I did considerably well by just making three purchases, but I would have loved to just buy the entire festival and have chocolate on demand for

the rest of my life, but that probably would not have been the best decision in life. Aside from my chocolate rant, the walking tours, and all the rest, I would have to say that climbing the Eiffel Tower was by far the best experience. Growing up, my mother always told me about the Eiffel Tower, how much she would love to see it, and how amazing it is, but to experience it for myself...and vicariously for her.... will probably be one the everlasting highlights of my life! While I was climbing I videotaped everything so that once I got home, my mother could climb along with me. Once I finally got to the top, I was so filled with emotions that I unexpectedly found myself crying. Filled with confusion regarding my tears, awe because of the view, and an accomplished feeling of success, I couldn’t help but think of my mother and how much she would have wanted to be there. Still now, even as I am recalling this moment my eyes cannot help but to well up with tears waiting to spill over. The entire experience seemed so majestic and unreal that the only way I knew it had actually occurred was by looking at the ticket over and over, as it never left my hands. It’s moments like this that makes me reflect on life and appreciate all the opportunities that I have been granted to come thus far. Not only was climbing the tower a tourist’s ‘must-do’, it was an ‘Olivia’s most cherished memory’.

fLying the Coup ~Olivia Brown~

I

10

Hannah Schorr, Italy

11

T

She sound of a sewing machine rumbling reminds me of my mother. My mother, Ivy, works as tailor in a local boutique in Durham, NC. As a child, I could usually find my mother in her sewing room working on her clients’ clothes or a sewing project for fun. Many of the garments my sister and I wore growing up were custom made by my mom. My mother sewed us many things, including, smoking dresses, bedspreads, and Halloween costumes. She would often bring my sister and me along to shop for buttons, zippers, and thread. While walking through the fabric store, my hands would move across the endless rows of fabric rolls; cotton, fleece, polyester, leather, silk and satin.

Last week, I made a trip to the South Bund Fabric Market in Shanghai. This market is popular among travelers and locals looking to buy custom made shirts, dresses, suits and jackets. When I walked through the front doors of the building, my mind immediately flashed back to the times I spent roaming different colors, textures and prints with my mother. The South Bund Fabric Market is a three story building jammed packed with individual vendor stalls. I was a bit overwhelmed at first; every stall was covered in fabric, model designs and

finished orders from floor to ceiling. I did not know where to start.

After wandering around some, Shanel and I entered a stall on the first floor that was recommended by our professor. We were both looking to order traditional Chinese dresses known as cheongsams (qípáo). From my understanding, one or two storefront merchants operate each stall. These merchants help customers pick designs, choose fabrics and measure sizes. Orders are then sent to neighboring buildings and laborers to be made. Customers typically wait about one week to pick up their custom made pieces.

The stall we selected was about ten square-meters in area and was run by a husband and wife team. Before making any concrete decisions, we asked the storekeepers how much one cheongsam would cost. The woman merchant grabbed the calculator from her desk and typed “450¥.” We knew this was a good and fair starting price, but proceeded to bargain for a discount. In the end, we agreed to buying five cheongsams between the two of us priced at 360¥ each. So, this meant each custom made silk cheongsam cost about $60, a price impossible to find back home.

siLk orders at the south Bund ~Chai Lu Bohannan~

Chai Lu Bohannan, Chongming Island, Shanghai, China

14 15

Through watching my mother sew, I have developed an appreciation for good craftsmanship and hands-on work. My mother has built up her clientele based on her quality workmanship. In the tailoring business back home charging $60 for a custom made cheongsam would result in negative profits. The South Bund Fabric Market’s low prices are made possible by China’s abundance of willing workers and low labor costs. Our vendor told us that the price of fabric and materials make up most of the retail price. The prices we encountered were lower than “off-the-shelf” items back home. For example, Nicky ordered three custom fit suit sets for the price of one off-the-shelf suit in the United States.

Sewing is a disappearing trade in the developed countries. It has become a specialty skill as more and more textile factories get outsourced to developing countries. There seem to be more tailoring booths in the South Bund Fabric Market building than there are in the city of Durham. The difference between tailoring prices and choices in China and the United States interests me. In my Chinese Marketplace class, my group is researching and conducting a field study of the South Bund Fabric Market. We will be digging deeper into the vendors’ daily lives, the power structure within the market and the supply chain. But, for now, I am most excited to pick up my three cheongsams tomorrow afternoon.

SChai Lu Bohannan,Great Wall, China

16 17

Z hen I first arrived in Zambia

it struck me that this country existed in brighter and sharper focus than my life in the United States. At home I took for granted the landscape, the wildlife, the clothes of the people around me, even the texture of the ground beneath my feet. All of these things existed more vividly for me in Zambia.

My memories of people in the town of Mwandi are similarly bright and sharp. I saw a woman in labor who barely cried out, but involuntary crinkles in her nose betrayed her buried pain. I remember a young girl who first played in the sand with me, then wanted to trace words in the sand, and finally began to scratch words onto her arm; trying to keep the letters with her.

Perhaps my sharpest memory from Zambia came from a conversation with a woman who worked at the house where we were staying. Lillian spoke with determination about working for a formula replacement program among HIV+ mothers in Mwandi. I knew that the program was controversial. Formula can increase infant mortality, in spite of reducing HIV transmission, due to higher rates of gastrointestinal disease. But Lillian, who is HIV+ herself, had used formula exclusively with her youngest child. In doing

so, she spared him vertical HIV transmission during breastfeeding. Hearing her story gave me a clearer me understanding of the complexity of this issue. How can you not be passionate about an intervention that spared your own child from a death sentence?

Even as I tell these stories I know that my memories of Zambia are changing. I want my mental image of Zambia to resist the fading and distortion that comes with time. But that is ultimately inevitable, and it is just as inevitable that Zambia itself will change with time. Part of what is so incredible about visiting Africa is that life there seems to exist in a simpler, earlier era. It is tempting to want to press pause on Africa. Many fear that a modernization will dull Africa’s colors, people, and culture. These are real fears. But just as real is my fear that the devastation of AIDS will continue forever, or that women’s voices will continue to be discounted in Zambian society, or that people in Mwandi will never escape a cycle of poverty. In the end, neither my memories of Zambia, nor Zambia itself can truly stay the same.

And although the status quo seems safer, better, more familiar, some change may be for the best.

memories from ZamBia ~Stephanie Hunt~

W

Ashley Parker, Senegal, third place

18 19

esson #3. Vanity is to be expected.2:05 p.m., July 12th. I have arrived at canal

ATV twenty minutes early in all black except for a colorful scarf I was lent to look less like I was attending a funeral. In my high heels, I towered over every single person in the waiting room so I gladly took a seat when one of the receptionists told me that Jóse, the man I had been arranging my visit with via email, would come a bit later to greet me. As I was waiting, the receptionists seemed to spend the whole time doing their make-up or fixing their hair (vanity example #1). Meanwhile, teenagers started piling into the waiting room. When Jóse finally arrived, he introduced himself and explained to me that I would be in the audience for the taping of the show “Vidas Extremas: Talento Peruano” to get a taste of behind-the-scenes action and be seated where I would most likely be on TV. Not too sure I knew what I was getting myself into, my instinct told me go for it, and Jóse left again for “un ratito” leaving me in the room full of teens who I presumed would be participating in the show in some way as well.

4:00 p.m. After making friends with some of the people who were also waiting to be directed to the set of the show, Jóse finally came back to take us into the TV station’s headquarters. Here, we were directed to a hallway where we waited more than an hour more (surprise, surprise). Might I remind you I am still in heels, and I am still at least a foot taller than everyone else around me. Also noted during the wait is that they have toilet paper in their bathrooms. And soap. This is a big deal, but I forget about it and continue to focus on the adventure at hand.

5:20 p.m. We have finally entered the set and it is SPECTACULAR. Compared to ATV SUR, ATV in Lima is much larger, cleaner, bigger, brighter, and better organized. I was directed to the center of the first row of the audience section where, according to Jóse, I would be filmed a great deal. As people were bustling to get to their places, many celebrities began piling onto the set (I didn’t actually know they were famous until these two girls next to me quickly educated me on Peruvian pop culture–I did recognize the Cuban salsa singer Vernis Hernandez, though. And let me tell you, I was STARSTRUCK).

Since I didn’t recognize the “status” of these show hosts and performers, and since I was one of the only foreigners in the room (still, somehow, towering over the rest), I attracted a lot of attention. Thanks to this, though, I could have genuine conversations with a few of them where I explained what I was doing there and they shared their thoughts on the TV program. I was told that there’s some unfair politics in the competition of the show, and for that reason, there’s tension between the performers and the producers (which is comically visible during commercial breaks). One example is how the wardrobe of the show participants is controlled by the channel, and no matter how uncomfortable the performer feels in the revealing outfit, they go along with it (vanity example #2). Also, the mother of one of the show contestants was seated behind me and said her daughter, as well as the other contestants, has been on a strict diet since the start of the show. She says she’s been watching her daughter lose weight fast to the approval of the show directors (vanity example #3… must I go on?).

Lessons Learned from the Latin ameriCan mediaL

~Ivana Masimore~

LIvana Masimore, Montevideo, Uruguay

20 21

Aadjustments ~Claire McDonald~

W hen I travelled to Peru with the Davidson study abroad program last spring, I expected some culture shock. Some things came easily: learning not to flush toilet paper, wearing sunscreen all the time because of a missing ozone layer, walking around with my backpack on my front to avoid pickpocketers (okay, I stopped that after one day). Other things were harder: I developed a serious Starbucks Frappuccino habit because I could never wait until my host family’s 3 p.m. lunch time, for example, and I got lost at least once a day the whole five months I was there. The food, usually good, could also be hard to get used to. One time, my host family decided to take me out for anticuchos (beef hearts cooked on a stick), which they typically ate in the car after ordering from a little window on the side of the road. Luckily, I was in the backseat by myself, so I managed to eat only my potatoes and hide the rest in my purse. Then, when unfamiliar food led to stomach viruses, my host family bought me a huge bottle of a pink electrolyte drink called “Fruity Flex,” which tasted disgusting and came with instructions to “drink within 24 hours.” But as much of an adjustment as it was, all those little moments of culture shock made my five months in Peru the incredible experience it was. Though it wasn’t always easy living so far away, I always felt at home and I came back with a true appreciation for Peru’s culture of generosity and kindness.

22

Ivana Masimore, Infierno, Peru

23

Oinally! A place with refrigerated dairy products! I reach out and grab the yogurt, but to my disgrace it is lukewarm. I look at the clerk behind the counter, “is the refrigerator broken?” My stomach churns—reminding me that it is still getting acquainted to the Ayacuchan diet. “The electricity bill is too expensive,” she replies; “we never keep it on.” I grab a bag of crackers, hand her one sol and then head back to FINCA. The afternoon desert sun has already begun to rot the meat in the market and the pungent smells of dead produce meld with the led-infused smoke that spills out of the exhaust of the car in front of me. I tuck my head into my jacket in an effort to evade the smell and I make my way between two boney dogs parading the market with their tails tucked between their hind legs, awaiting the leftovers. (If they weren’t walking I’d have declared them dead). I pass by a vendor selling chicha morada, a typical Peruvian beverage made with boiled purple maize, and I feel a wave of queasiness—sure that it got me sick the last time I had it. I am a few blocks away from FINCA, or a financiera, as one fellow called it on my first day trying to find it. After two weeks the noise of the cars’ incessant honks, women calling out the price of their vegetables with their Quechuan accents, and the occasional cat-call from the men on the streets has become the background noise of these daily walks. The sight of a five-year-old child carrying their baby sibling, a fruit seller (with nowhere

else to go) squatting in her pollera to pee on the street, and an elderly women carrying loads of heavy produce on her diligent back—these are the symptoms of underdevelopment, I thought as I made my way into FINCA; I grabbed my notebook, ready for the day’s interview.

The woman I was assigned to interview that day didn’t have a particularly unique story to share, but nearly two years later I still remember the youthful eyes that belonged to her weathered face, whose wrinkles marked the laborious hours spent under the sharp sun. “What have you accomplished with your microfinance loans?” I asked her, as I had already done so with many other women. She told me about the increase in sales and then she said, for the first time “I’m finally able to rebuild my home with noble material;” “noble” I thought, and I recalled the sturdy walls that surrounded me in my life in the United States—the walls of my Miami home that had endured the powerful winds of Hurricane Andrew—I had never seen them as “noble.” I knew I was fortunate to live under a roof, but I had never thought to describe the material with such a word—it was a description full of appreciation. Her account became one of many interactions that gave the bleak Ayacuchan landscape a vibrant color, forever hiding the symptoms of underdevelopment and repainting the scene with the inspiring stories I heard.

overComing the symptoms of underdeveLopment ~Andrea Becerra~

F

24 25

Jordan Lubekemann, Tunis, Tunisia

Jfinally reach my destination and escape the two hour frenzy of immigration. I breathe a sigh of relief. “Here I go,” I murmur. The automatic doors part. I confidently stride out, but it’s not what I expected. My host family is frantically asking a group of other Asian girls if they are Catherine Wu and trying to convince them that they are.

I was the only Asian in my town of Antonio Carboni. I lived three months in rural Argentina, surrounded by cows, farms and cow farms. For a tried and true city girl, it was a big change. My family was really curious about my life back home, in America.

“Do you need sticks to eat your food?” “No. It’s alright. I can use forks.” I tried

not to burst out laughing from the irony because I’m usually the one that asks for a fork at Chinese restaurants.

“Do you sleep on a bed?”“What do you mean, like a mattress? Yes, I

actually sleep on two mattresses up really high!”I had never met people in my life that

genuinely believed this many stereotypes about my race. We are so politically correct and uptight in America, it is easy to forget they even exist. I had difficulty convincing people that I even was American. They would always ask:

“No, but where are you really from?”The misconceptions were sometimes

uncomfortable, and often outrageous. At the same time, it was incredibly refreshing to know

that I defined their interpretation of an Asian, and an American. I was a novelty, exotic, an ambassador. I introduced them to my culture, and they opened my mind to Argentina.

At first, I thought everything was... quaint. I would see the school and my class with eight kids—how quaint! The grocery store where the cashier picked out your groceries for you—how quaint! The dirt roads, the 40 minute drive to the next town, the entire family together for dinner—how quaint! The truth is, I didn’t think that everything was quaint and adorable. I was just lying to myself. I was homesick. I judged everything; held it up to the light, comparing it to my comforting standards.

But eventually the kindness and sincerity of Argentina broke down my barriers and I let go. I learned to enjoy drinking mate, making strange hand gestures as I talked, kissing random strangers on the cheek and living in the slow, leisurely pace of Latino culture.

So what is diversity to me? It’s progress. It’s making personal connections. It’s hilarious. It’s wondering for months what the strange appliance next to the toilet is. It’s watching the Simpsons every night in Spanish. It’s the marketplace of ideas, fusion of passions. It’s the humanity within us. It’s a wordless feeling, a stolen kiss, a laugh line. It’s the awareness that the world is queerer than we could’ve ever imagined, that we are all different, but incredibly the same.

on judging and Being judged

~Catherine Wu~

I

26

Madison Rogas, Frutillar, Chile

27

nepaLi homeComing

N~Jessie Blount~

Jessie Blount

28 29

I

“Little Gidding”We shall not cease from explorationAnd the end of all our exploringWill be to arrive where we startedAnd know the place for the first time —T.S. Eliot

t is still dark outside when my wristwatch alarm chirps 5:00 a.m. Careful not to wake, Sangita, my new Nepali roommate, I slip into trail runners and running pants and perform the now-habitual exercise I had picked up from yoga school in India; I chug water in a squat for “the health of my organs” as Guru had claimed. By 5:10, I am winding my way through Kathmandu’s sleepy alleys and garden paths.

The city is just beginning to wake up. People clear their throats violently and spit off rooftop balconies, Nepal’s performance version of the rooster crow. Even after only a week in Kathmandu, I’ve found that if you claim Nepali nationality, you must cleanse your sinus passageways. Loudly. Every morning. Before 6:00 a.m.

I pass men drinking steaming shots of chai and women filling buckets at the community tap, their bright korthas a blurred palette of greens and reds. I dodge street vendors hanging bananas on white strings that dangle from push carts. My steps fall in unison with the Hindi filmi songs that blast from university students’

cell phones as they pick their way through littered streets to the library.

With all of Kathmandu as my witness, I make the steep uphill climb to Chobar, one of the city’s holiest temples. And it seems all of Kathmandu is not only watching me run but also joining the run; the closer I am to the top, the more crowded Chobar’s dirt path becomes.

Almost to the top, the man in front of me pauses. He looks out into the valley. Doing as the locals do, I turn around and my breath catches. The sun shyly peaks her nose around the Himalayas. Kathmandu is gilded in orange. I hear the far away hiss of pressure cookers echoing from kitchen to kitchen below and the scent of breakfast lentil soup that follows. Nearby, women pray, men breathe their way through pranayama exercises, and prayer wheels jangle softly. Together we watch the same sunrise, but see a different view. I see a day that begins with a journey. I see a new familiarity.

As I stand next to the fifty-something man in his blue and white 80s warm-up jacket, I feel home.

I

SCoConut LentiL soupSubmitted by Jessie Blount

Daal inspired by the everyday chefs of Nepal.Serves 4.

1 can coconut milk 1 cup red lentils 4 cups vegetable or chicken broth or water 1 tsp salt 2 Tbsp coconut or peanut oil1 tsp mustard seed1 tsp red pepper flakes (2 tsp if you like it hot)1 onion, diced2 cloves garlic, minced1 tsp ground turmeric1 tsp ground cumin½ tsp ground cinnamon Fresh cilantro, for garnish

1. Cook lentils until soft in broth with salt. If you’re using a pressure cooker, let lentils stew on low heat for 5 minutes after pot reaches pressure.

2. As the lentils cook, warm coconut or peanut oil in a medium saucepan on medium-high heat. Test oil’s heat with one mustard seed; when your tester mustard seed begins to sizzle, add remaining mustard seeds and red pepper flakes. Breathe in deeply and enjoy the culinary aromatic experience.

3. Let spices fry until just beginning to brown. Turn heat to medium-low, add onion, minced garlic, pinch of salt, turmeric, cumin, and cinnamon and let onion caramelize. When browned, take out of pan and put aside.

4. When lentils are done, add onion-spice oil mix and coconut milk. Let simmer on low heat for 5–10 minutes, stirring often.

Serve with lime, a dollop of Greek yogurt, vinegary cucumber salad, and naan toasted in butter and minced garlic.

Jessie Blount

30 31