Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

-

Upload

abelsanchezaguilera -

Category

Documents

-

view

15 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 1/27

Wagner, 'On Modulation', and "Tristan"Author(s): Carolyn AbbateSource: Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Mar., 1989), pp. 33-58Published by: Cambridge University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/823596

Accessed: 27/07/2010 17:48

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cambridge

Opera Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 2/27

Cambridge

Opera

Journal,

1,

1,

33-58

Wagner,

'On

Modulation',

and

Tristan

CAROLYN ABBATE

I look

down towardshis

feet;

but that's

a fable.

So

says

Othello,

confronting Iago

for

the last

time in

Shakespeare's

play.

He

looks down to seek for the cloven hoof of a demon, for only if Iago is satanic

can

Othello

understand what has

come to

pass.

Looking

down

-

the

physical

gesture

-

represents

an

impulse

to

interpret,

to

find

clues,

codes,

signs

there

in

the darkness.

But

Iago

is no

supernatural

being:

'that's a

fable'. What

remains

is

an

enigmatic

Iago

more

frightening

than

any

demon

-

the

attempt

to

interpret

undermined

by

the

sign

not

given.

The

Iago

of

Verdi's Otello is

far less

terrifying.

When

Verdi's

Iago

sings

his

credo,

we are

twice

comforted;

first,

by

the

litany

of

belief

that

seems

to

explain

his

deeds,

and then

by

what that

credo

affirms,

the

possibility

of

explana-

tion.

The

misanthropic

baritone

-

in the

twentieth

century

at

least

-

has

been

seen as less inscrutable than his

Shakespearian

ancestor;

the credo to some extent

satisfies our

search

for

meaning

behind

Iago.

The

difference between

the two

Iagos

-

insoluble

riddle,

motivated

villain

-

points up

one

effect of

any

credo:

it

keeps

at

bay

the

menace of

inexplicability,

for a

credo is not

only

an

expression

of

faith,

but a

voice

that

justifies

and

elaborates

upon

'I',

upon

itself. Verdi's

Iago

describes

Iago.

While

we

might

question

his

probity

(he

may

be

lying),

who

questions

his

authority

or

his

voice? But

the

more

explicable Iago

is not

necessarily

to

be

preferred.

The

credo

also

blocks

interpretation,

by

channelling

it

into

narrower

limits,

defined

by the authority of that voice. The ShakespearianIago invites an attitude of

listening

and

the

impulse

to

decipher

the

fragmentary

and

obscure.

Othello,

marvelling,

will

always

look

down,

and

never

find his

answer.

What

do

Othello's

downward

glance

and

Iago's

credo

have to

do

with

Wagner?

Wagner's

characters

also

tend

towards

self-explanation;

in

Wotan's

case,

some

might

say,

at

narcotic

length.

But

it

is

not

Wagner's

characters

but

Wagner

himself

who

can

be set

against

the

two

Iagos.

Wagner's

credos

were no

brief

spatter

of

verse,

but

the

volumes of

the

Gesammelte

Schriften,

the

letters,

the

autobiography

and even

the

autographs

in

Wahnfried's

vault;

of

these,

it is

the

literary

credos that

have

commanded

the

lion's

share

of

atten-

tion.

Perhaps

the

voluminousness of

these

credos

explains

many

Wagnerians'

faith

in

Wagner's

'elaborations

upon

"I"',

a

belief

which

supports

their

labour of

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 3/27

Carolyn

Abbate

interpretation.

Wagner

is

frequently

called

upon

for

a

blessing

from

beyond

the

grave,

and

- as Shaw

pointed

out

- he can be counted

on to bless

almost

anything,

so

contradictory

are his

opinions.1

Does the

extent of

Wagner's

credos

explain

the

astonishing

conviction of his critics?

Over-confident

assertions

about how

Wagner

composed

or how his

music works are

endemic

to

analytical

writing,

and

scepticism

about

single

and

finite

explanations

has

yet

to

unsettle

the bluff

conviction

of

most

Wagnerian

analyses.

To

be

sure,

such

confidence,

even

arrogance,

is

not limited

to

writing

on

Wagner,

but it

seems

more

pro-

nounced there than

elsewhere on the

music-analytical

scene.

Even the

critical

position

that takes

the

composer's

voice

as

guide

does

not

create a

secure

ground

for

interpretation:

a

truism

that

needs

to be

stressed.

Declaring

an

author the most

privileged

observer of

his own

work

cannot in

any

case

enable

us

to

retrieve his

opinions

as

they

'really

were',

beyond

a

century

of interpretation (intuitions about any text are unavoidably shaped by a sense

of

its

reception

history),

the

distance

engendered by

time,

by

the

tenuousness

of

our

human bond to the

culture that

produced

Wagner.

The

invocation of

these

commonplaces

is

a

prologue

to

speculation

about

a few

sentences

Wagner

wrote in

about

1856,

a

tiny

credo,

a

voice of

authority

heard

imperfectly,

a

voice

that

necessarily

channels

interpretation

in

certain

directions.

Thinking

about this

credo

may

thus do

no

more

than

expose

the

mutability

of all

Wagnerian

readings,

and

remind

us

that

Wagner's

voice,

unlike

Titurel's,

cannot

really

be

compelled

to

speak,

cannot

command

that

some

analytical

Grail

be

unveiled. This

particular

credo,

however, impinges

on

central

issues in

Wagnerian

criticism: whether

Wagner's

music is coherent in

'purely

musical'

terms,

how

music

projects

either

poetic

meaning

or

staged

dramatic

events,

the

problems

of

taking

Wagner's

prose

as

primer

for

Wagnerian

analysis,

and,

finally,

the

interpretation

of

Tristan.

So

while the

credo

alone

may

not

compel

attention

-

or fix

belief

-

the

questions

it

raises

are

still

honourable,

still

urgent.

1

The

symphonic myth

To a

great

extent

the

'interpretation

of

Tristan'

is a

central

issue

because

Tristan's

reputation

in

the

Wagnerian

canon is

special:

the

most-analysed

opera,

the

most

'absolute'

score.

Of

course,

testimonials to

the

purely

musical

power

of

the

other

operas

abound:

Bruckner,

notorious

for

consuming

Wagner's

operas

as

music

alone,

asked

after

Walkire:

'why

do

they

burn

Briinnhilde at

the end?'

Yet

Joseph

Kerman's

'Opera

as

Symphonic

Poem'

-

Tristan,

of

course

-

is

a

phrase

that

embraces the

intuitions

and

interpretations

of

a

hundred

years

past,

even

as it

nudges

the

reader

towards

some

traditional

assumptions

that

1

George

Bernard

Shaw,

The

Perfect

Wagnerite

(New

York,

1909),

118.

34

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 4/27

Wagner,

'On

Modulation',

and

Tristan

Kerman

calls

into

question.2

'Symphonic',

then,

makes both

a statement

about

the

relationship

of music to

poetry

or

staged

drama,

and

a

value

judgement

concerning

the music:

the

one,

that we need

not

appeal

to external

elements

-

whose relation to

the

music

may

be tenuous - to

account for

musical

events;

the

other,

that

the

music

is

'unified' or

'coherent'

in

purely

musical

terms.

In

all

this

it

is

important

to

remember that

poetry

and

'staged

dramatic

events'

are

not

the same as

'drama',

which is a

much

more

nebulous,

transverbal

phenomenon.

Absolute

music,

after

all,

can

be drama. More than

this:

the

'drama'

in

Wagner's

works,

as

Dahlhaus

has

pointed

out,

is

'the

outcome

of

a

conjunction

of

text,

music and

stage

action' and not

something

resident

only

in

the

concrete

'dramatic'

libretto.3

Wagner

argued

(with

rare

consistency)

from

Oper

und

Drama in 1851 to the

'Anwendung'

in

1879 that a

poetic

idea,

which first takes shape as text, is projected into music born of that 'poetic

intention',

and

the

music realises

this

poetic

idea

in

the

'region

of

perception

that has no

need of

words. The drama can

proceed,

according

to

Wagner's

dogma,

only

from

the

musical

realisation.'4

If

Wagnerians

agree

about

any-

thing,

of

course,

it

is

that

Wagner's

works

are

drama

to

the

highest

power.

The

symphonic myth

calls into

question

not

this

abstract

'drama',

but

rather

the

connection of

music

to

specific

verbal,

concrete

elements

(poetry,

stage

events).

The

argument

that

Tristan contains the

least

text-bound of

Wagner's

music

can

appeal

to

documentary

evidence.

Many

of

the musical

sequences

used in

the

opera

drifted around from text

to

text;

part

of the

music that

ended

up

as

'Brangane's

Consolation'

in

Act I

began

in

sketches for

Act

III

of

Siegfried.5

Peripatetic

tendencies like

these

may

well

suggest

that

Tristan's

music

has

little

enough

to

do

with

specific

poetic

or

staged

events.

Advocates

of

Tristan's

sym-

phonic

status

have,

however,

been

concerned not

only

to

downplay

poetry

and

stage-action,

but also

to

demonstrate

the music's

coherence,

or

'unity',

and so

have

appealed

to the

score as

well.

Kerman

was

fashioning

out of

his

title

a

snare for

those who

would also

swallow

this

second

aspect

of

symphonic

myth,

and saddle

Tristan's

music

with

the

dubious

pedigree

of

'structure'

2

Joseph

Kerman,

Opera

as

Symphonic

Poem',

in

Opera

as

Drama

New

York,

1956),

192-216.

3

See

Richard

Wagner's

Music

Dramas,

rans.

Mary

Whittall

Cambridge,

979),

54-5.

Pierluigi

Petrobelli

hasmade he

same

point

aboutVerdi's

dramaturgy;

ee

'Music n

the

Theatre A

Propos

of

Aida,

Act

III',

in

James

Redmond, d.,

Themes

n

Drama3:

Drama,

Danceand

Music

Cambridge,

980),

129.

4

Wagner's

Music

Dramas

see

n.

3),

55.

5

The

wandering

musicwas

discussed n

Curtvon

Westernhagen,

he

Forging

f

the

Ring,

trans.

Arnoldand

Mary

Whittall

Cambridge, 976),

149;

see

the

critiqueby

John

Deathridge,Wagner's ketches ortheRing:SomeRecentStudies',TheMusicalTimes

(May, 1977),

386-7;

andthe

discussion

by

Robert

Bailey,

The

Methodof

Composition',

in Peter

Burbidge

nd

Richard

utton,

eds.,

The

Wagner

CompanionLondon,

1979),

317-26.

35

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 5/27

Carolyn

Abbate

and

'organisation'

that reductive

analysis

will

inevitably

mistake

for

virtue.6

Reductive

analyses

of

Wagner

have

never been

hard to find. Tristan's

sym-

phonic reputation

was hardened into

dogma early

in this

century,

in two

articles

by

Karl

Grunsky, particularly

his

analysis

of Tristan Act

III,

'Wagner

als

Sym-

phoniker'.7

The

title

says

it

all,

and

phrases

like

'closed,

organised

form'

or

'a

work

shaped

simultaneously

according

to a

poetic

and

a musical

plan'

mingle

with the

inevitable

hagiography.8 Today

we can still

read

of: a

'formal

structure that

encompasses

the whole

work'

(Tristan);

'large Wagnerian

units'

(the

mature

operas

in

general);

a 'harmonic model

for the tonal

structure

of

the entire

new

ending'

(Tannhauser

Act

I

scene

2);

a

'preconceived

plan

of

the

entire work'

(the

Ring);

an

'opera

[that]

has

become a unified

musical

form'

(Tristan

again)9

-

all

this

presented

in

a

matter-of-fact tone of

common

sense,

as if such benumbing 'forms', 'plans' and 'structures' were immanent in this

intricate and

undermining

music.

This

litany

was

culled from

essays

that

represent very

different

analytical

approaches

-

formal,

harmonic,

global-tonal,

thematic; and,

to be

sure,

by

being

taken out

of context

the formulae to

some extent

misrepresent

the

authors'

views. For

instance,

Anthony

Newcomb,

even

though

he

pointed

to

the

lack

of

any

consideration of

'large-scale

forms' as

a

'defect'

of

recent

German-language

Wagner analysis,

has all

the same

followed

Dahlhaus's

pathbreaking

work

in

stressing

the

'ambiguity

and

incompleteness

of

Wagner's

forms'.10

What is strik-

ing,

however,

is how

ritualistic

the

words in

the

litany

have

come to

be,

even

6

Wagner's

wn

arguments

bout he

'symphonic'

roperties

f

his music

have,

I think

it is

fair o

say,consistently

been

exaggerated

nd

befoggedby

his

commentators.

he

point

has

beenmade

by

Carl

Dahlhaus;

ee for

exampleWagners

Konzeption

es

musikalischen

ramas

Regensburg,

971),

103-6.

The issue s

also

discussed

by

Egon

Voss,

Richard

Wagner

nd

die

Instrumentalmusik:

agnersymphonischer

hrgeiz

(Wilhelmshaven,

977),

154-81,

and

Wolfram

Steinbeck,

Die Idee

des

Symphonischen

bei

Richard

Wagner:

Zur

Leitmotivtechnikn

"Tristan nd

Isolde"',

n

Christoph-

Hellmut

Mahling

and

Sigrid

Wiesmann,

ds.,

Bericht ber

den

Internationalen

Musikwissenschaftlichen

ongress ayreuth

981

Kassel,1984),

424-36. All

three

point

out that

Wagner's

otion of

symphonic

form'

was of a

vague,web-likeseriesof looselyrelated

motifs,

not some

gargantuan

nd

encompassing

tructure. uch

revisionist

accountsas

these

have

yet

to be

taken

up by

most

English

anguage

writing;

one

notable

exception

s

John

Deathridge,

Wagner's

Unfinished

Symphonies'

paper

eadat

the1986

meeting

of

the

Royal

Musical

Association,

orthcoming).

7

SeeKarl

Grunsky, Wagner

ls

Symphoniker',

Richard-WagnerJahrbuch,(1906),

227-

44;

and

Das

Vorspiel

und

dererste

Akt von

Tristan nd

Isolde',

Richard-Wagner

Jahrbuch,

(1907),

207-84.

8

Grunsky,

Wagner

ls

Symphoniker'see

n.

7),

231.

9

The

citations

are

aken

rom:

William

Kinderman,

"Das

Geheimnis

erForm" n

Wagners

Tristan nd

Isolde',

Archiv

iir

Musikwissenschaft,

0

(1983),

187;

Anthony

Newcomb,

'The

Birthof

Musicout

of

the

Spirit

of

Drama',

19th-Century

Music,

5

(1981-82),

52;

Carolyn

Abbate,

The

Parisian

Venus"

nd

the

"Paris"

Tannhauser',

ournal

f

the

AmericanMusicologicalociety,36(1983),109;RobertBailey, TheStructure f theRing

and

ts

Evolution',

19th-Century

Music,

1

(1977),

61;

and

Rudolph

Reti,

The

Thematic

Processn

Music

New

York,

1951),

342.

10

Newcomb,

46

and

64.

36

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 6/27

Wagner,

'On

Modulation',

and Tristan

in

analyses

sensitive to

ambiguities, suggesting

a

bias towards

'harmonising'

terms

(structure,

form,

plan, large-scale,

unity)

that

most

emphasise Wagner's

'commonality

with lesser

works or

ordinary

values'.

1

My frustration with large-scale structuralistand reductive analysis is evident

from

my

language

and

my

tactics

(both

of which

may

seem

blunt),

but

this

frustration stems from

suspicion

that the

'insights'

generated by

such

analysis

do indeed

shrink

Wagner

into

the

negligible, by

the

very

discourse

of the

inter-

pretation.

What do we

gain

by

saying

that

Tristan Act III is 'in' B

major?

Or,

more

alarmingly,

that it

is

in sonata

form?

Or that

it

is

'unified'?

So

are

many

lesser

works;

the

more unified a

work,

the

more

unquestionable

its

design,

the

more

reduced,

ordinary

and

negligible

it

becomes.

'Symphonic'

interpretations may

well

consider the

relationship

of

poetry,

stage

action and

music in the same

'harmonising'

terms that

inform

their

discus-

sion of music qua music. Grunsky, for instance, regardedWagneras an infallible

Gesamtkiinstler;

he

claimed that the

poetry

was

admirably

symbolised

in

the

music,

falling

into a

tautological

argument

that

was to

become

another ritual

formula in

subsequent Wagner analysis

(music

is

at

once

hand in

glove

with

poetry

or

stage

drama and

nonetheless

purely-musically

coherent,

because

the

poetic

structure

is

calculated

to

go

hand in

glove

with the

pure

musical

structure,

and

round and

round).

Indeed,

most

opera

criticism,

not

just

the

Wagnerian,

has

warmed

itself

at this

hearth. But the

cosiness of

the

argument

seems,

again,

dubious. For

one

thing,

the

music

may

well

be

self-sufficient

to

the

extent

that it ignores or even contradicts both the poetry and the staged drama in

opera,

and

proceeds

on its

own

way.12

For

another,

Wagner's

music

may

be

regarded

as

driven

by

poetry

to

transcend

the

limited

orderliness of

absolute

music and

'form'

-

an

animating

idea

that

Wagner

himself

proposed.13

Both

reject

the

'harmonising

bias'.

Wagner's

tiny

credo

may

be

understood

both

as an

anti-harmonising

and

anti-symphonic

voice,

for

this is

what it

says:

Uber Modulation n

der

reinen

Instrumentalmusik

nd im

Drama.

Grundverschieden-

heit. Schnelle

und

freie

Ubergange

ind

hier

eben

oft so

nothwendig

als

dort

unstatthaft,

wegen

der

fehlhenden

Motive.

[On

modulation n

pure

instrumentalmusic and in drama.Fundamental ifference.

Swift

and free

transitionsare n the

latter

often

just

as

necessary

as

they

are

unjustified

in

the

former,

owing

to

a lackof

motive.]

But

when

was

this

written,

and

why?

Dominick

LaCapra,

Rethinking

ntellectual

History

and

Reading

Texts',

n

Dominick

LaCapra

nd

StevenL.

Kaplan,

ds.,

Modern

European

ntellectual

History:

Reappraisals

and

New

PerspectivesIthaca,

1982),

51.

12

SeeCarlDahlhaus,Wagners KunstdesUbergangs" derZweigesangn "Tristan nd

Isolde"',

n

G.

Schuhmacher,

d.,

Zur

musikalischen

nalyse Darmstadt,

974),

475-86.

13

For

moreon

Wagner's

ranscendencef

'coherence'

ee

my

essay,

Symphonic

Opera,

A

Wagnerian

Myth',

in

Carolyn

Abbate

and

Roger

Parker,

ds.,

AnalyzingOpera:

Verdi

and

Wagner

Berkeley,

1989),

92-123.

37

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 7/27

Carolyn

Abbate

2 The

sketchbook,

and

Wagner

besieged

Wagner's

credo

may

have been the seed

of a

potential essay

on

modulation,

one that never came to

fruition,

and so

joined

the Buddha

opera

Die

Sieger

and the late symphonic sketches in a limbo inhabited by Wagnerianephemera.

These sentences 'iiber Modulation' were written on

page ninety-three

of

the

Tristan

sketchbook,

a sketchbook that is

very tiny,

has

an

ornamental

clasp,

and

contains an assortment that includes a

prose

sketch

for

the so-called

'Scho-

penhauer' ending

to

Siegfrieds

Tod

(made

in

1856),

a

prose

sketch

for

Die

Sieger

(dated

May

1856),

sketches

for Tristan

(both

textual and

musical),

prose

frag-

ments

concerning

critics and

criticism,

the record

of

a

bizarre

dream.14

The

actual Tristan sketches have been

transcribed

and

discussed at

length,

in

a

natural

focus

upon

material of

palpable

interest

that

has,

perhaps,

distracted

attention

from the other

fragments

in

the

book.15

The

sketchbook

begins

with the

Table of

Contents

for a

Gesammelte

Schriften,

which

may

be

gnomic

in

interpreting

what follows.

This

Gesammelte

Schriften

was

to be

systematically organised;

all the

essays

listed in

it were

written

before

1854,

with one

exception:

'Uber das

Dirigieren',

not

finally

written

until

1868-

69.

Wagner's

plan,

then,

embraces

a

potential

essay

in

addition

to those

already

finished.

And

many

of

the

prose fragments

in the

sketchbook

seem to

be

thoughts

for

other

potential

essays.

The words on

page

thirteen-

'Beethoven

-

Schumann/

musik.

Anschauungen

u.

Begriffe'

-

have

the air of a

title. These

prose

fragments

jostle

savage

and

pessimistic

remarks

about the

critics to

whom

exegetical

prose

essays are futile ripostes; yet Wagner will offer these essays to the public so

that,

'conquered

by ignorance

and

vulgarity',

he

may

retreat into

silence and

write no

more.16

Even the

strange

dream

recorded

on

page fifty-five

can

be

drawn into

this

circle.

In

the

dream,

Wagner

and

Georg

Herwegh

are

surrounded

by

a

crowd

that

sings

at

them;

Wagner

can see their

open

mouths

and

tongues

as

they press

in

upon

Herwegh

and

himself: a

menacing

and

comic vision

of

14

Bayreuth,

Nationalarchiv er

Richard-Wagner-Gesellschaft,

II a

5;

discussed n

Robert

Bailey,

The

Genesisof Tristanund

Isolde',

Ph.D. diss.

(Princeton,

1969),

16-29

(the

sketchbook

s

referred

o

as the 'Brown

Diary').

On

dating

he

sketchbook,

ee

John

Deathridge,

Martin

Geck

and

Egon

Voss,

Verzeichnis

er

musikalischen

Werke

Richard

Wagners

nd

ihrer

Quellen Mainz,1986),

431-5.

15

See

Deathridge

t

al.

(n.

14),

431-5

for a

complete

bibliographical

isting

of

transcriptions

and

discussions.

16

Tristan

ketchbook

see

n.

14),

8-9.

'Erst

wenn sich

dieses

rre,

wirre,

trivialeund

selbst

boshafte

..

.] Gerede

n

Bezug

auf

meine

nun bereits

vor

Jahrender

Offentlichkeit

iibergebenen

Kunstanschauungen

erstummt ein

wird,

also erst

dann,

wenn

eine

Widerlegung

olcher,

die einstmir

widerlegen

ichtaber

kennenlernen

ollten

[..

.]

kann

ich michbestimmt iihlen,mich ibermanches nmeinen riiheren chriften nklar

gegebenes

der

eidenschaftlich

ufgefasstes

rklarend

..

.] noch

einmal

vernehmen

u

lassen.Bis dahin

mogen

meine

Freundemich

vom

Unverstand nd

der

Gemeinheit

esiegt

und

zum

Schweigen

ebracht

nsehen '

38

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 8/27

Wagner,

On

Modulation',

and

Tristan

besiegement

by

a

multitude.17 he theme

of

vituperation

nd attack

s

repeated

in

the latter

part

of

the

book,

in remarks

on

English

and German

critics,

and

on

the

final

page,

'how

to react to a man like me

can never be

made

clear

to theworld,because hathappensonly rarely'.18

I

read the

sketchbook

fancifully,

as

if

the book

itself,

and the

composite

of its

contents,

were some artfulcreation.But the

book is

a

miscellany;

t

has

no

coherence

except

what

we

impose.

The

prose

fragments

about

explanation

and

ill-disposed

critics have

nothing

to do with

their

neighbouring

Tristan

sketches,

or

Die

Sieger,

or

the new

ending

for

Siegfrieds

Tod.

Or do

they?

Some link

between

Wagner's

wounded

resignation

and

the

passive

nihilism

of

Die

Sieger

or

Tristan

might

be

envisaged:

f

facile,

the

association

does

not

ring wholly

false. Yet if the

sentences

on

modulationare

called a

credo,

the

name

proposes

another,

more tenuous

association,

one between

the

fragment

(andits statement)and anapproacho interpretingTristanwhosegenesis s en-

tangled

with the

fragment,

between he

covers

bound

by

that

ornamental

lasp.

3

Wagner

on

modulation

'On

modulation n

pure

nstrumental

musicand n

drama.

Fundamentally

iffer-

ent.

Swift and free

transitionsare in

the

latter

often

just

as

necessary

as

they

are

unjustified

in

the

former,

owing

to a

lack of

motive.' In

these

brief

phrases

there is

much

to

consider,

and

the

implications

for

modish

habits of

Wagnerian

analysis

are

disquieting.

If the

constraints

governing

harmonic

language

in

absol-

ute music are wholly unlike those in 'drama' - which I take to mean opera

or

more

specifically,

perhaps, opera

in

the

sense

of

Wagner's

own

operas

as

poetic-cum-musical

drama

this is

because

freer

harmonic

gestures

are

permitted

in

opera,

where

they

are

motivated

by

poetic

ideas

or

stage

events.

This

is

the

motivation

lacking

in

pure

instrumental

music,

in

which the

quick

modula-

tory

transitions

are

unjustified

because

nonsensical:

not

animated

by

something

outside,

in

the

poetry

or

the

stage

action,

they

will

exist as

grotesque

harmonic

flailings

that are

meaningless

in

any pure

musical

context.

Wagner

proposes,

as he

had

before in

Oper

und

Drama,

that

his

music

trans-

cends

canonic rules

governing pure

music.

But

he

also

makes

a

point

about

music's means for

symbolising

the

poetic

idea

justifying

this

transcendence:

that

modulation,

a

harmonic

phenomenon,

is a

metaphor

for

meaning

residing

in

words.

The

latter

is

perhaps

the

more

telling point,

for

it

was

one

Wagner

was

to

make

again

and

again:

that

music's

representation

of

poetry

resides

17

Tristan

ketchbook

see

n.

14),

55.

'Ein

Traum

Paris).

Mit

Herwegh.

Menschen

umringen

und

singen

uns an.

H.

verwundert.

ch:

"hatsich

das

nicht

auch

Gessler

sic]

m

Tell

gefallen

assen

miissen?"

dann

h6chst

acherliche

Mund-

und

Zungenarbeit

ines

Knaben

beim

singen.'

Wagner

was in

Paris

briefly

at

the end

of

February

855,

but

the

indication

'Paris'

might

mean

not

thathe

had

the

dream n

Paris,

but

that

he

dream

was

set in

Paris.

18

Tristan

Sketchbook

see

n.

14),

107.

'Der

Welt

wird

jede

Art

von

Wohlverhalten

egen

Andre

gelehrt;

nur

wie sie

sich

gegen

einen

Menschen

meiner

Art

zu

verhalten

at,

kann

ihr

nie

beigebracht

erden,

weil

es zu

selten

vorkommt.'

39

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 9/27

Carolyn

Abbate

not

solely

or

primarily

n the

fashioning

f

leitmotifs,

but n harmonic

nfoldings.

Again,

there

are echoes

from

Oper

und Drama

Part

III,

particularly

rom

a

famous

passage

which

prepares

he discussionof

'poetic

musical

period':

Nehmenwirz.B.einen tabgereimtenersvonvollkommenleichem mpfindungsge-

halte

an,

wie:

'Liebe

giebt

Lustzum

Leben',

o

wiirde

hierder

Musiker

...]

keine

natiirliche

eranlassung

um

Hinaustretenusder

einmal

ewahlten

onart

rhalten,

sondernr

wiirdedie

Hebung

nd

Senkung

es

musikalischen

ones

...]

in

derselben

Tonart

bestimmen.

etzen

wir

dagegen

inenVersvon

gemischter

mpfindung,

ie:

'DieLiebe

bringt

Lustund

Leid',

o wiirde

ier,

wie

der

Stabreimwei

entgegengesetzte

Empfindungen

erbindet,

er

Musiker uch usder

angeschlagenen,

er

ersten

Empfin-

dung

entsprechenden

onart,

n

eine

andre,

er

zweiten

Empfindung,

ach

hremVer-

haltnisseu

der n

dererstenTonart

estimmten,

ntsprechenden

Tonart]

iberzugehen

sich

veranlafit

iihlen

...]

Die

Rechtfertigung

ur

sein

Verfahren,

asals

ein

unbedingtes

unswillkiirlich ndunverstindlichrscheinen iirde,erhaltderMusiker aheraus

der Absicht

des

Dichters.19

[For

example,

et us

take

an

alliterativeine

of

consistent

emotional

content,

such as:

'Love

brings

joy

to

life'.

In this

case the

Composer [...]

would

receive

no

natural

inducement

o

depart

from the

initially

chosen

key;

rather

he

would

arrange

he

rise

and fall

of the

pitches

[...]

within

the same

key.

Let

us

contrast

with this

a

line of

mixed

emotional

content,

such

as:

'Love

brings oy

and

sorrow'.

Here,

just

as

the

alliteration

binds

together

two

contrasting

entiments,

so

the

Composer

would

feel

licensed to

modulateout of the

initial

key,

associated

with

the

initial

sentiment,

nto

another

key,

associatedwith

the

second

sentiment,

and

related o

the first

key

in

the

same

degree

as the

second

emotional

colour is to

the

first

[...]

The

Composer thus

receives

from

the

intent

of

the

Poet

the

justification

for

his

procedure,

which

since

unres-

tricted

might

seem

arbitrary

and

inexplicable.]

The

direct

analogy

between

the

semantic

caesura

separating

'Lust'

and

'Leid'

and

the

distance between

keys

is

worked

into a

secondary

analogy

in

the

final

sentence,

that the relative

distance

between the

two

keys

would

reflect

the

depth

of

the

fissure

between the

words'

meanings.

Some

abstract

harmonic

hierarchy

-

the

close

relations between

some

keys,

the

distance

between

others

-

lies

behind the

idea. But

typical

of

Wagner's

dialectical

thinking

is

the

inevitable

antithetical term, as the abstractharmonic canon - the juxtaposition of closely

related

keys

is

unremarkable,

'arbitrary

or

inexplicable'

modulation

between

keys

more

distant is

forbidden

-

must

be

undermined if

the

music is

to

symbolise

the

distance

spanned

by

the

leap

in

poetic

meaning.

Wagner

in

effect

proposes

that the

harmonic

caesura be

twice told in

music:

directly

by

the

modulation,

and

indirectly,

as it

were

philosophically,

by

transgression

of

prim

harmonic

convention,

by

a rule

that is

broken.

This

passage

could

be cited

to

refute

one of

the

commonest

misconceptions

about

Oper

und

Drama,

that

the book

concerns

'words

versus

music' in

a

battle

that

subordinates music

to

poetry.

Wagner

views

his

music not

as

subordi-

nate to poetry, but as driven by poetry to transcendence, a realm of freedom

19

Gesammelte

Schriften,

IV

(Leipzig, 1872),

190-2

(my

emphasis).

40

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 10/27

Wagner,

On

Modulation',

and Tristan

not

open

to absolute music.

Far from

being

humbled

n

servitude,

his

music

(Wagner's,

of

course)

is

bei

den

Gottern.

Wagner's

conception

of 'modulation'

is

very

different

from

thatof

contempor-

ary theory.

His

scale is

small;

he is

discussing

modulation

within

a setting of one

or

two short

lines

of

verse,

internal modulation

that a

reductionist

analysis

would

view as

ripples

on the

surface,

no modulation

at all.

A

reading

of

the

'Alte

Weise'

shaped

by Wagner's

idea

might

speak

of

passages

in

Eb

major,

or

C

major,

or

Ab

major,

while Schenker's views

them all as

epiphenomena

arising

out of F

minor.20

The

misunderstanding

of

Wagner's

minute

scale

of modulation

has

had

a

profound

effect

on

Wagnerian

reception

in

the

twentieth

century,

through

the

agency

of

Lorenz. As

Dahlhaus

pointed

out two

decades

ago,

Wagner

describes

the

'poetic-musical

period'

as a

longer

series

(langere

Reihe,

that

is,

longer

than

Wagner's

two-line

examples)

of those

single,

internally

modulating

lines;

that is, a period of at most twenty to thirty-odd measures.21Lorenz's 'poetic-

musical

periods'

were,

of

course,

hundreds

of

measures in

length,

each 'in'

a

single key

and

each

encompassing

the

single poetic

idea

summarised

by

his

marvellous

titles,

'Wotan's

Rest',

'Siegfried's

Hubris',

'Polite

Behaviour'

(in

Tristan

Act

I).

Wagner's

semantic

caesura

between

two

words,

and

the

tiny

modulation

that

spanned

it,

were

made

monstrous.

Lorenz's

misreading

of

Wagner

-

his

mutation of the

argument

in

Oper

und

Drama

-

and his

enlargement

of the

'poetic-musical

period'

resonate

in

all

analyses

that

embrace certain

fundamentally

Lorenzian

assertions,

even

as

they

make

motions towards

rejecting

Lorenz.

These

assertions

include the

idea

that

long

stretches of

Wagner's

operas

can

be

said

to

be

'formally

organised',

or

'in'

a

certain

tonic.22

And

his

vision

of

scale has

infused

much

English-language

(particularly

American)

Wagner

analysis

with

robust

and

manly

rhapsodies

to

largeness,

vastness,

immensity.

Contemporary

German

Wagner

criticism,

informed

directly

and

indirectly by

Adorno's

demythicisation

of

Wagnerian

monumentality,

has

long

been more

concerned

with

detail.

4

Analysing

Tristan

The

fragment

from

Oper

und

Drama,

the

fragment

'On

Modulation', suggestthat

music's

capacity

to

symbolise

poetry

resides in

harmonic

allegories

for

20

Heinrich

Schenker,

Harmony,

trans.

Elizabeth

Mann

Borgese

(Chicago,

1954),

112.

21

See

Carl

Dahlhaus,

'Wagners

Begriff

der

"dichterisch-musikalischen

Periode"',

in

Walter

Salmen,

ed.,

Beitrage

zur

Geschichte

der

Musikanschauung

m

neunzehnten

Jahrhundert

(Regensburg,

1965),

179-94.

22

See,

for

example,

Bailey

(n. 14),

147-61.

Other

tonal

analyses

include

Nors

Josephson,

'Tonale

Strukturen im

musikdramatischen

Schaffen

Richard

Wagners',

Die

Musikforschung,

32

(1979),

141-9;

for a

discussion

of the

issues

raised

by

this

type

of

tonal

analysis,

see

Newcomb

(n. 9),

48-54.

Stefan

Kunze

has

made a

provocative

suggestion

that

Wagner

often

plays

a

game,

gestures

towards a

'structural

tonic

arrival'

that is in

many

cases

illusory,

as the

key

arrived at

often

has

only

momentary significance,

and is neither adumbrated in the music that precedes it, nor

important

to that which

follows;

see

'Uber

Melodiebegriff

und

musikalischen Bau

in

Wagners

Musikdrama',

in

Carl

Dahlhaus,

ed.,

Das

Drama

Richard

Wagners

als

musikalisches

Kunstwerk

(Regensburg,

1970),

especially

124-8.

41

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 11/27

Carolyn

Abbate

meaning.

This

is a

challenge

to the traditional

notion

that

leitmotifs

are

Wagner's

chief means

of

symbolising poetic images.

His music

actually projects

poetry

and

stage

action in

ways

far

beyond

motivic

signs.

This

should be

a

commonplace

of Wagnerian criticism (not only, of course, because Wagner made the sugges-

tion),

but

has

yet

to overcome

the

leitmotif's

hegemony.

The

Wolzogian

labels

for

Wagner's

motives

are,

of

course,

no

longer quite

consumed

at face

value,

though

once

they

were;

Newman's

The

Wagner Operas

feasts

upon

name-tags.23

Much

Wagnerian

analysis

has

been

directed

towards

demonstrations

of how

motivic-thematic ideas are

used not as

signs,

but

to

create

hints of

formal

shape.24

But

the

underlying

assumption

is,

nevertheless,

that

music's

obligations

to

symbolise

poetic

language

or

stage

events are

indeed

met

chiefly

by application

of motif

as

leitmotif

-

hence this

dialectic of

motif

as both

form-defining

and

referential,

which

was

already

in the

nineteenth

cen-

tury a commonplace of Wagneriancriticism.25

While

Wagner

may

have

deplored

an

over-symbolic

reading

of

his

motifs,

he

nonetheless

insisted

that his

music was

symbolic,

and for this

reason

funda-

mentally

richer than

pure

music had

any right

to

be.26

Wagner's

thoughts

'On

Modulation'

suggest

one

beginning:

that we

search for

the

connections

between

poetry

and

music

in

a realm

other

than

semiotics.

More than

this:

as an

anti-

harmonising,

anti-symphonic

voice,

the

fragment

'On

Modulation'

might

form

the

impetus

to a

more

generous

reading

of

detail,

a

digressive

reading

that

touches

upon

the

classic

donnees

of

Wagnerian

analysis (leitmotif,

form,

text

structure),

to

suggest

that

they

have

pushed

down

and

away

-

because in their terms inex-

plicable

-

eccentricities,

looseness,

an

indeterminate

musical

symbolism

not

consistently applied.

Tristan has

been

behind

much of

the

foregoing

discussion,

and

with

it,

of

course,

the

reputation

the

opera

has

achieved

as

Wagner's

purest

score.

Testi-

monials to this

reputation

abound

(one

need

only

count the

analyses),

so it

may

seem

unnecessary

to

dwell

upon any

single exegesis.

Carl

Dahlhaus's

1974

analysis

of the

Act

II

'Tagesgesprach'

nonetheless

compels

our

attention,

because

it

raises

explicitly

the

question

of

text

symbolisation

to

argue

a

radical

position:

that

the

music

contradicts at

times

both the

structure and

the

sense

of

the

poem.27

Thus one 'harmonising'bias- an 'apparentlyunequivocal assumption of musical

23

This

despite

he

fact that

Wagner

himself,

irst

among

he

sceptics,

criticised

Wolzogen

for

limiting

his

analyses

o

motif-naming,

hus

gnoring

he

ways

motifsalso

serve o

weavea

musical

web.

'Uberdie

Anwendung

der

Musik

aufdas

Drama',

Gesammelte

Schriften,

X

(Leipzig,1883),

241-2.

24

The

locus

classicuss

Dahlhaus's

iscussion

of

Wagner's

luid

and

open-ended

vocations

of

conventional

musical

orms,

'Formprinzipien

n

WagnersRing

des

Nibelungen',

n

Heinz

Becker,

ed.,

Beitrage

ur

Geschichte

er

Oper

Regensburg, 969),

95-129.

25

For

a

modern

nstanceof

analysis

basedon

this

dualism,

ee

Arnold

Whittall's

iscussion

of

'structure'

ersus

the

dramatic

ignificance

f

thematic

omponents'

n

his

chapter

or

Lucy

Beckett's

Richard

Wagner:

arsifal

Cambridge, 981),

61-3.

26

SeeAbbate n. 13),96-102.

27

See

n.

12.

That

ension

rather

han

agreement)

an

exist

between

operatic

musicand

the

poetry

or

stage

drama t

sets is an

dea

opera

criticism

would

do well

to

nurture;

it

is

this

tension,

perhaps,

hat

raises

ertain

peratic

works

above he

ordinary.

42

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 12/27

Wagner,

On

Modulation',

and Tristan

analysis',

the demonstration

of

unity, correspondence, agreement

- is

rightly

called into

question

as a remnant of

classical

aesthetics,

which has limited

histori-

cal relevance to

nineteenth-century

art.28

Dahlhaus's

interpretation

has, then,

provoked the dialogue that follows.

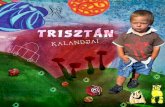

How does

Tristan's music

speak independently

of text?

Dahlhaus

offers

as

an

instance

of

textual-musical

disjunction

the

passage

in

Ex.

1. An

important

rhetorical turn in the

poem

occurs at

Isolde's 'Im

Dunkel

du,

im

Lichte

ich'

[You

in

the

darkness,

I

in the

light],

which

is

followed

by

Tristan's

'Das

Licht

O

dieses

Licht '

[The

light

Ah,

this

light ]

The

former is

the last in

a

long

chain

of one-line

antitheses,

but

by

introducing

the

word

'Licht'

it also

prepares

the text

that

follows,

Tristan's

speech

about

light/day,

which,

as a

long speech

for

a

single

speaker,

breaks

the

pattern

of

single

antithetical

lines. The

music,

however,

passes

over the

structural turn

by

continuing

to

spin

out the

'Liebesju-

bel' motif; an

abstractly

musical

imperative

of motivic

continuity

has thus over-

ridden

a textual

signal

for

change.

This

non-correspondence

of

textual

and

musical structure

is,

for

Dahlhaus,

a

sort of

'art of

transition'.29

A more

complex

series of

disjunctions

is

at

work

in

Tristan's

long

speech

and

Isolde's

reply

shown

in

Ex.

2.

The

music for

the two

speeches

patterns

itself

into

roughly parallel

strophes;

both

speeches

are set to

the

same

sequence

of

thematic

sentences,

both have

the

same

striking

cadence at

the

end.

Similar

musical

arguments

-

the

parallel

'strophes'

-

thus

accompany

texts

whose

con-

tent,

at

least,

is

different,

for

Isolde

speaks

of

extinguishing

the

torch,

whereas

Tristanhad spoken of setting it alight. The musical-formalimperativeof strophic

variation,

a

musical

impulse

towards

periodicised

shape,

has

brought

a

'disregard

for

the

meaning

of the

text',

even

while

an

element of

text

structure

(the

'character

of

dialogue',

the

alternating

speakers)

is

projected

by

the

alternating

strophes.30

As

another

instance of

textual-musical

disjunction,

Dahlhaus

emphasises

the

ways

in

which

Wagner

uses

leitmotifs in

wholly

formal

ways,

in

order

to

shape

periods.

When

the

'Sehnsuchtsmotiv'

sounds

under

Isolde's line

'fur

Marke

mich zu

frei'n'

[to

woo me for

King Marke],

its

recurrence is

'wholly

musically-

formally,

and

not

poetically

motivated'.31

Not

poetically

motivated:

the

ques-

tion

being

asked

is

blunt

enough,

what has

'Sehnsucht'

got

to

do

with

King

Marke? Apparent contradictions between the leitmotif's semiotic

baggage

and

the text

it

accompanies

are

advanced

as

proof

that

'the

justification

[of

musical

28

See

n.

12,

477.

29

478;

the

reference o the

'artof

transition'

s,

of

course,

o

Wagner's

amous

etter

o

Mathilde

Wesendonck

bout

he

'secret'

f

musical

orm

n

Tristan.

n a

letterof

29

October

1859,

Wagner

alled

he

'Kunst

des

feinsten

allmahlichen

berganges'

as

evinced

in

the

Tristan

Act

II

love

duet,

with

its

transition

rom

renetic

greetingo languorous

metaphysics)

he'Geheimnismeinermusikalischen

orm';

ee

Wolfgang

Golther,

ed.,

Richard

Wagner

n

Mathilde

Wesendonck

Berlin,1904),

189.

3

479.

31

481.

43

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 13/27

Carolyn

Abbate

Etwas

msiiger

im

Tempo

^ ISOLDE

Sehr bitter.

-

Klagende,

nicht

grol3e

Bewegungen

T

^

pti-

+ _

r - - t 3

m Dun

-

kel

du,

im

Lich te

ich

'Liebesjubel'

motive

p

dim.

-

--

-

Tristan

entfernt

sich

etwas von

Isolde

-

Heftige

Bewegung

TRISTAN

-".

."

Das

Licht Das

Licht

0

die-

ses

-

'Liebesjubel'

motive

-i

|Ur

t

rf-T1

=

?

L^

f

.--

f

-f

f--

/0

rLi,

wi

e

g

ver-J

es nt

Licht,

wie

lang

ver-losch

es nicht

Die

I-

_

4L~- .(..

_i

t

.,J

l

f.n

dim. - - - - - - p I cresc. - - - - - -

t4p--

r

y

.... ^

- M

- f

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~j'r

'

--J

^

i'ij ..

L

-^-I

--

E

I

Ex. 1

44

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 14/27

Wagner,

On

Modulation',

and Tristan

events]

by

the

text,

described

n works

like

Oper

und Drama

and

"Zukunfts-

musik",

s

absent'

rom

Tristan.32

Dahlhaus'sevocation

of the

leitmotif

must

provoke

a

response

n

the

form

of a question:why assume hat thesemioticbaggage for instance, Sehnsucht'

- is

somehow immanent n the

motif and the score?

Only

if

'Sehnsucht'

s

an inevitableand real

component

of

the

musical

gesture

can

we

argue

hat

text

is

ignored,

that the motif's

portmanteau

named desire

seems to

contradict

Isolde'swords.

Opera

criticism

would

face a

dizzying

liberation f the

conven-

tional

assumption

about

leitmotif

- that the referential

meaning

s

immanent

-

were turnedon its

head.

My

own view is that

Wagner's

motifs

haveno

referential

meaning; hey

may,

and of

course

do,

absorb

meaning

at

exceptional

nd

solemn

moments,

by

being

used

with elaborate

calculation as

signs,

but

unless

purposely

maintained in

this artificial state, they shed their specific poetic meaning and revert to their

natural

state as

musical

thoughts.

The

Ring, perhaps,

is

unique

in

that

so

much

energy

is used to

keep

the

motifs

suspended

against

gravity,

in

this

complex

semiotic

condition;

certainly

Wagner

did not

try

this in

any

other

opera,

and

in

Tristan the

motifs

are,

all in

all,

without

poetic

significance.

Should

opera

critics

convert to this

faith,

there

could be a

scene of

absolution

rivalling

the

one

Tannhauser witnessed

in

Rome,

as

hundreds of

opera

composers

are

absolved of

'misusing'

their

own leitmotifs to

contradict

the

text,

and

bidden

to

rise,

shriven of

sin.

Dahlhaus

has,

of

course, routinely

and

properly castigated

those

who

uncriti-

cally

accept

the

labels in the

conventional

leitmotivic

guides.33

Scoffing

at

labels

(while

continuing

to

use

them)

is

a ritual

feature of

most

modern

Wagnerian

analysis;

Deryck

Cooke's

argument

about the

mis-labelling

of

the

Ring's

'Flight'

motif is

one

locus

classicus.34

But

scepticism

about

labels is

not

the

same

as

disbelief in

an

immanent

meaning

for

motives;

and

Dahlhaus

treats

leitmotif

in

the Tristan

analysis

as if

the idea

expressed

by

the

label

-

'Sehnsucht'

-

were

indeed

bred into

the motif's

very

existence.

Were

this

not a

fundamental

assumption,

the

idea that a

leitmotif

recurs

for

musical-formal

reasons

in

defiance

of

text

would

be

unthinkable.

By now it is clearthat Dahlhaus's lively readingof Tristan'smusic - as unfold-

ing

to

demands of

absolute-musical-logic,

as

disregarding

the

poem

-

falls

out

of

an

analysis

dealing

with

form. The

textual

analysis

privileges

rhetorical

fea-

tures,

larger

elements of

structure;

these

are,

indeed,

occasionally

'confirmed'

by

the

periodic

structure of

the

music;

it

is

content

that

is most

often

contra-

dicted.

Music is

read as

fluid

formal

shape,

defined

most

often

by

thematic

events

(repetition

of

a

certain

theme,

patterns

of

cadential

figures).

In all

this,

32

Dahlhaus

(see

n.

12),

481,

'Die

Verklammerung

st

ausschliefilich

musikalisch-formal,

nicht

dichterisch

begriindet:

eine

Rechtfertigung

durch

den

Text,

wie

sie in

"Oper

und

Drama"

und in "Zukunftsmusik" postuliert wurde, fehlt.'

33

See,

for

example,

'Zur

Geschichte

der

Leitmotivtechnik bei

Wagner',

in

Das

Drama

Richard

Wagners

als

musikalisches

Kunstwerk

(Regensburg,

1970),

17-22.

34

Deryck

Cooke,

I

Saw the

World

End

(Oxford,

1979),

48-56.

45

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 15/27

Carolyn

Abbate

'STROPHE1'

rh

I

h

i

e

.

,

.

I

.

h

l

Son

-

ne

sank,

der

Tag

ver

-

ging;

doch

sei

-nen

P doce

r

/5

^h

Jn

Neid erstickt'

er nicht:

sein

scheu

-

chend Zei

chen

ziin

- det er

an,

und

0

t,JE

N

Su-

-o

Vo

)I

o

,

. L.

I I

1

1

dd

20

r?g

r

r

J

p

F'

steckt's an der Lieb - sten Tii - - re, daB nicht ich zu ihr

'

'H

trj

*

"dim.

-

i _

.

p

*

11-

IL

Sie nahert ich Tristan

ISOLDE

22

'STROPHE

2'

Doch

der Lieb

sten Hand

lhe

Dochder

Lieb

-

sten

Hand

liosch - -

-

te

das

t~

-

--

re.

iiRLit

Yd

"I

a

fl

r

- - -

-

-

-

p dolce

,,

ff

JiT

J J J J

I

-1,-1 1

I

T-

-

i

Ex. 2

46

II

T.

T.

fuh

I

I

T

(a

G_._

P

d--

--

--

'

-

---S9-

-

-.

,

-I,

s4,14.f-iA

,

-

-f

9 --

-

I

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 16/27

Wagner,

'On

Modulation',

and

Tristan

mit

groRem, reudigem

Stolze

25

_

I.

X

Cd

?

8#'e

4

I 7l

r

I

-T

1

IJ

K

I

Licht,

wes

die

Magd

sich wehr

-

te,

scheut' ich

mich

.. nTr

nicht:

in

Frau

Min

-

nes_

Macht und

Schiitz,

cresc.

cresc.

d

m-

(cresc.

dim.

'

'

30

I.

Dem

Ta

- - -

-

[ge ]

47

I

7/17/2019 Wagner, On Modulation, And Tristan

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/wagner-on-modulation-and-tristan 17/27

Carolyn

Abbate

Dahlhaus

responds

in

part

to a conventional

nineteenth-century

ssociation

between rhetorical

or

structural

periods

in

poetry

and

the

theoretical

notion

of

musical

period'.

The credo in 'Uber Modulation'and the famous 'Lust und Leid' passage,

however,

press

for another

reading.

In

Oper

und

Drama,

Wagnerpreached

more

than

he

general

irtues

of

poetic-musical orrespondences, roposed

more

than

eitmotif

as a