Vol 9-10, 2004

Transcript of Vol 9-10, 2004

CONTENTS

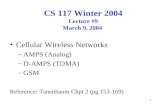

TRADITIONSGatra: A Basic Concept of Traditional Javanese Gendingby Rahayu Supanggah

Wayang Wong Priangan: Dance Drama of West Javaby Yus Ruslaianatranslated, edited, and augmented by Kathy Foley

INTERVIEWSDivining the Diva: an interview with Nyi Tjondroloekitoby Nancy Cooper

Sinta Wullur and the Diatonic Gamelanby Huib Ramaer

Komang Astita: the performance of soundby Elaine Barkin

INSTRUMENTATIONGambang Cengkok in Slendro Manyuracompiled by Carter Scholz

SCORESTetabeuhan Sungut (Onomatopoeia)by Slamet Abdul Sjukur

a little piece for pianoforteby Michael Asmara

Rag for Deenaby Barbara Benary

Gending Moonby Lou Harrisonnotes by Jody Diamond

Waton by Komang Astitaby Elaine Barkin

Trimbat by Ida Bagus Made Widnyanaby Andrew McGraw

RECORDINGHomage to Tradition CD notesby Rahayu Supanggah

MONOGRAPH (print issue only)

The Mills College Gamelan documented by Will Ditrichdesigned by Lou Harrison and William Colvig

EDITORIAL

Words from the past, music from the present, andhopes for the future are all presented in this edition ofBalungan. Through the years, many people havesubmitted articles and interviews that never appearedin print. We take this opportunity to bring some thosecontributions to light: Elaine Barkin’s 1990 interviewand report on Komang Astita's residency at UCLA in1995, and an extensive compendium of gambangcengkok compiled by Carter Scholz in the early 90s.

As happens with the passage of time, the gamelancommunity has lost many good friends and teachers inrecent years. Nancy Cooper gives us an interview ofone of the most popular and at the same time uniqueJavanese pesindhen, Nyi Tjondroloekito (192?–1997).Rag for Deena, by Barbara Benary, was dedicated toDeena Burton (1948–2005), an artist and scholar activein Indonesian arts in New York City. New music inIndonesia lost a great champion in Harry Roesli, adedicated composer and activist based in Bandung butwell known throughout the nation. Many will miss theAmerican composer and gamelan enthusiast LouHarrison (1917–2003). This issue includes a previouslyunpublished score, and the documentation of thegamelan Harrison and partner William Colvig(1917–2000) built at Mills College in California.

Two previously unpublished Indonesian composershave scores here. The composition by Slamet Sjukur isentirely vocal; a sort of “mouth-gamelan.” MichaelAsmara’s piece for piano is also quite theatrical.

The most recent information is in AndrewMcGraw’s discussion and transcriptions of Trimbat byIda Bagus Made Widnyana, drawn from Andy’s just-completed dissertation on new music in Bali. Also newto many readers will be the English version of RahayuSupanggah’s important theoretical article on theJavanese musical concept gatra, as well as the completenotes for his self-produced CD Homage to Tradition.

Looking to the future, this issue marks the debut ofthe electronic version of Balungan. Articles appear atwww.gamelan.org/balungan, with some additions.

I appreciate the support shown by several librariesto continue a print edition; an exclusive monographwill be included in each annual issue. OTOH,www.gamelan.org serves an ever-growing cyber-community of gamelan players, scholars, and othersinvolved in Indonesian arts and their internationalcounterparts.

jody diamondhanover, nh

7/7/2005

1

13

27

30

34

38

59

71

72

74

80

83

92

95

Deena Burton1948 – 2005

1951 – 2005

Lou Harrison William Colvig1917 – 2003 1917 – 2000

Balungan 1

TRADITIONS

Gatra: A Basic Concept of Traditional Javanese Gendingby Rahayu Supanggah

IntroductionIn daily life, the Javanese community takes the wordor term gatra to mean a beginning, a bud, the earlyform or embryo of a final form of something, whichwill provide both life and meaning to that thing. Itmay be a living creature, either plant or animal. Whena baby in a mother’s womb first begins to take humanshape, the Javanese describe it as wis gatra, whichmeans it already has its early form. In Old Javanese orKawi, gatra means body or picture. Likewise, when aseed begins to sprout and its shoot becomes visible, orwhen a branch or twig begins to grow leaves, theshoot or bud can be called a gatra. Thukulan, thokolan,or bean sprouts can also be called gatra.

Why the Javanese karawitan community uses theword gatra to describe one of its highly important andconceptional elements has not been established. Not asingle karawitan theoretician has explained theconcept of gatra from the perspective of an early formof life. All practitioners and students of traditionalkarawitan, whether they realize it or not, will beunable to separate their karawitan, or musicianship,from what they call gatra. A singer or instrumentalplayer — whether of gender, rebab, bonang, gambang,sindhen, kendhang, siter, suling, or saron — and anyother musicians involved in a karawitan (gendhing)performance, will always take the various elementsand aspects of gatra into consideration as animportant point of reference for their treatment orgarap of the music. Although the importance of theposition and role of gatra in karawitan is known, notmany people have undertaken a deeper, more detailedexplanation or analysis of the mystery that is gatra.

Sindusawarno, Martopangrawit and Judith Beckerhave all touched on the importance of gatra as anobject for the analysis of pathet. Sindusawarno with hisding-dong concept (1962),1 Martopangrawit with hisconcepts of maju-mundur and direction of seleh notes(Martopangrawit 1975: 57), and Judith Becker with hercontour concept (1980) have opened our eyes to theimportance of gatra in traditional Javanese karawitan,especially in Surakarta style, which is the stylediscussed here.

GatraSo far, in everyday discussions on traditional

karawitan, gatra is often understood to mean thesmallest unit in a gendhing, a composition ofJavanese karawitan, consisting of four balunganstrokes.

• • • •A B C D

Important karawitan figures have proposed atleast two sets of terms to describe each part of agatra; both are used in traditional Javanesekarawitan circles. Ki Sindusawarno used the termding kecil to describe the first balungan stroke (A),dong kecil for the second balungan stroke (B), dingbesar for the third balungan stroke (C), and dongbesar for the fourth balungan stroke (D).Sindusawarno’s format for a gatra is thus:

ding kecil (A)dong kecil (B)ding besar (C)dong besar (D)

Ki Sindusawarno was a teacher with abackground in the hard sciences; he mastered boththeory and practical skills of western music. He hada great love and interest in the development of thetheory of Javanese karawitan, and wrote IlmuKarawitan [Theory of Karawitan], which became animportant reference in the world of karawitantheory. Some of his ideas still reverberate in certain(conservative) karawitan communities, particularly[the national high school conservatory]Konservatori Karawitan Indonesia or KOKAR.(This school subsequently became known asSekolah Menengah Karawitan Indonesia, or SMKI,and has now become Sekolah Menengah Kejuruanor SMK 8.) As of the year 2000, Ki Sindusawarno’sbook is still used as a main textbook.

Martopangrawit, with his background as amaster artist or musician of karawitan, or pengrawitempu, and an intellectual pioneer in the field ofkarawitan theory, chose to use terms of a moreartistic nature. This is particularly evident in hischoice of terms related to (practical) karawitantreatment, in which he uses references drawn from

2 Volume 9–10, 2004

the kosokan (direction of bowing) of the rebab.Martopangrawit’s format for a gatra is:

maju/forward (A)mundur/back (B)maju/forward (C)seleh (D)

Judith Becker does not assign special terms to eachseparate part of a gatra but rather identifies gatra (orbalungan) according to its contour, which is classifiedand distinguished by looking at the different orders ofpitch in the balungan. For example, the gatra (with thebalungan) 2321 has the contour:

This actually has the same contour as the balungan5653, 3532, etc. The gatra 6365 with the contour:

has the same contour as the gatra (with the balungan)!5!6 or 5253, and so on.These three scholars basically see the gatra more as

an object with a fixed form, although I should notethat Martopangrawit already sensed that gatra wassomething both alive and dynamic (for which see hisconcept of irama).

HierarchyFrom the names given to the parts of a gatra by

Sindusawarno and Martopangrawit, we shall attemptto understand their concepts of a gatra. Sindusawarnomore explicitly reflects that each part of a gatra has itsown dimension or hierarchical role, with a differentfunction or position, whose level depends on itsposition within the gatra.

The term dong, face to face with ding, clearlyindicates a difference in dimension or level, in whichdong is considered more important (higher) thanding.2

This will become clearer if we attempt to refer to andcompare it with the same term, dong, which is used intraditional Balinese karawitan. Dong is a karawitanterm that refers to the name of a pitch with the mostimportant function in (most) Balinese karawitancompositions/gending, or the pitch often used for thefinal gong note (used to end most gending), whose roleor function is more important than [the other Balinesepitch names] deng, dung, dang or ding. Ki Sindusawarnoexplicitly used the term dong to correspond to thewestern term tonic. He often used the term tonic in hisdiscourse about the theory of karawitan(Sindusawarno, 1962: 22-23). The use of the terms kecil(small) and besar (big) together with ding and dong

clearly show the difference in hierarchical functionor role of each part of the gatra.

Although less explicit, Martopangrawit’sconcept of gatra also implies the existence of ahierarchy of role or function of each part of thegatra. The use of the word seleh [end of cadence orgoal tone] for the final stroke of a gatra clearlyshows his awareness of or intention to denote theimportant role of the final part of the gatra. Seleh is amusical point of reference; almost every instrumentin an ensemble is orientated to the seleh note. Selehalso means terminal, the end point of a journey oraction, or it can also mean a feeling of submission orresignation, to stop or end something with a feelingor relief.

There is a similarity of meaning betweenMartopangrawit’s seleh and Sindusawarno’s dong,in connection with its role or position as a musicalreference point for instrumental and vocal treatmentin traditional Javanese karawitan. Meanwhile, maju(forwards) and mundur (backwards), which refer tothe bowing of a Javanese rebab, indirectly indicatethat mundur is heavier than maju. This may beobserved at almost every important point (especiallyseleh) in a gending, when the rebab player uses abackward bowing motion.3

If this assumption is correct, the hierarchicalorder of the balungan strokes in each gatra,according to these two karawitan experts, may beformulated as follows:

a) Sindusawarno gives the order of strength as D-B-C-A (dong besar is the strongest, dong kecilsecond strongest, ding besar weak and ding kecilweakest).

b) Martopangrawit gives the order of position orstrength as D-B-A/C (seleh is the strongest part,mundur is the second strongest part and maju, inboth position A and C, has the same weakposition).There is no outstanding difference between the twoin the hierarchy of each part of the gatra. Both agreethat D holds the strongest position, followed by B. Aslight difference of opinion then appears as to thepositions of A and C. In this case, Martopangrawitchooses to be more careful, not differentiatingbetween the two, or choosing to place the two (Aand C) on the same level, as is reflected in the namegiven to both: maju.

We can look more closely at gatra, by placing itas a concept with wider dimensions. In my opinionat least, I understand gatra to contain the followingelements. A gatra:

1. Is a unit;2. Has a long measurement, by dividing the

unit into different parts;

Balungan 3

3. Has each part with its own hierarchicalfunction, position and role (aside fromwhether or not we agree withMartopangrawit or Sindusawarno’shierarchy) according to its place within thegatra;

4. Has a melodic journey or movement. It shouldbe noted that although, at certain times, thebalungan gending may be fixed on one pitchfor a relatively long duration (possibly morethan one gatra), as in the case of balungannggantung, nevertheless the instrumentaltreatment does not always stay on the samepitch but may play around the pitch of thebalungan nggantung.4 It is this melodicmovement of a gatra that is often presented as“types” of balungan arrangement (forexample balungan mlaku, nibani, nggantung,muleg, ngandhal, pacer, pin mundur, dhe-lik,maju kembar, mlesed and so on), contour ordirection of pitch. Due to these characteristics,a gatra:

5. Has both shape and form (including what isimplied in Judith Becker’s contour concept); agatra also has:

6. A specific character;7. And what is most important (and to my

knowledge, has not yet been touched upon bykarawitan theoreticians in various discussionson the theory of karawitan, which is reasonenough to call attention to it) is that gatra alsocontains the meaning of something that is“alive”. Gatra, like a shoot or an embryo,implies the existence of life, which shouldgrow, change and develop, and whose degreeof fertility is highly dependent on a number offactors, elements or aspects (including someoutside the gatra itself, such as theartist/musician and various aspectssurrounding his/her background) connectedwith the world of gatra or the world ofkarawitan in general.

I would like to present my opinion of the gatra assomething which is alive and therefore constantlychanging and developing. I prefer to look at gatrafrom a wider perspective, including various otherelements of karawitan with a nature or charactersimilar to or the same as gatra. One of these elementsof karawitan is gending — a musical composition ofJavanese karawitan, particularly in Surakarta style.

Martopangrawit describes gending as anarrangement of pitches with shape and form

(Martopangrawit: 1975:3). In my opinion,gending is in fact something more complex thanmerely an arrangement of notes with form.Karawitan, which traditionally belongs to thefamily of oral music, is in fact a gending or newcomposition, which may only be enjoyed orobserved (through listening) after beingperformed by a group of musicians (andvocalists when necessary, certain types ofgending — such as gending bonang and sampak —do not include vocalists) to produce a sound. Thewritten tradition only became known in theworld of karawitan after karawitan notationappeared, especially Kepatihan notation, at theturn of the 20th century. (Prior to this, ondo orladder notation and rante notation were used,although only in limited circles). After thewritten tradition entered the world of karawitan,especially with the large numbers of peoplemaking documentations or teaching or recordingbalungan gending with Kepatihan notation(some of which have even been published anddistributed to the general public), many peoplebegan to call this balungan notation gending(Supanggah, 1988:3).

Gending is an abstract and imaginary concept. AsI have already mentioned, a gending only existswhen it is performed by a group of musiciansthrough the treatment (garap) of karawitan. Agending is a tapestry or combination of the overallsound of the ensemble created by all theinstruments and vocalists, through the musicians’interpretation of the karawitan composition(imaginary, inner melody5, or unplayed melody6)according to the time and context of theperformance. Thus, the materialization of a gendingdiffers on each occasion it is performed, and ishighly dependent upon its musicians and context.

Comparing Gending and GatraIn his book entitled Pengetahuan Karawitan

(Knowledge of Karawitan) Volume I,Martopangrawit names at least 16 (sixteen) forms ofgending (Martopangrawit, 1975:7). Gending withthe forms merong kethuk loro kerep and above (ketuk4 kerep, ketuk 2 arang, ketuk 4 arang, ketuk 8kerep, which incidentally are also called by thesame term, gending7, in Javanese karawitan), andinggah (ketuk 2 or ladrang, ketuk 4, ketuk 8, andketuk 16) in fact display several characteristicssimilar to those of the gatra.

Like gatra, a gending is single unit with differentparts consisting of gong units (phrases), commonlyknown as cengkok units. In a written composition,a gong unit is often analogous with a paragraph, a

4 Volume 9–10, 2004

part of a composition that implies a complete idea.The size of a gong unit varies according to the form ofgending. The form of a gending, on the other hand, ispartly determined by the number of balungan strokesin each gong unit8.

As such, the form of a gending may be said to beparallel with the size of a gending. The existence of agatra as a unit is also implicit in the way in which agatra is written, with a space between each gatra andthe next. For example, here is part of the inggah fromGending Rebeng, kethuk 8, laras pelog patet nem:

•16• 1653 •635 6126 •123 •123 6532 3565Compare this gong unit with a gatra unit, which

consists of four parts, marked by balungan strokes inwhich each balungan stroke has its own different roleor position.

We can divide the above gong unit into smallersections (usually consisting of two or four sections)marked by kenong units (a structural or punctuatinginstrument). Javanese musicians consciously see theimportance of the role of kenong units as smallerterminals. The kenong terminal is often consideredanalogous with a full stop in a written composition,indicating the end of a (musical) sentence, complete inboth form and impression. The importance of theposition of a musical kenong unit is visible fromexpressions, statements or questions asked by variousmusicians in practical karawitan situations on a day-to-day basis: “(Wis tekan) kenong pira iki?” (Whichkenong unit [are we up to in this gending?]).

The importance of the role of a kenong as anindependent unit is also visible from the way in whichnotations for Javanese gending are written. Usually aspace is left between one kenong unit and the next,even when there is sufficient room to continue writingthe next kenong unit on the same line; it is also thenumber of kenong units in a gong unit thatdistinguish between a ladrang (consisting of 4 kenongunits in a gong unit) and ketawang (consisting of 2kenong units in a gong unit) form of gending.

Here is an example of how a Javanese gending isusually written, with each kenong unit [kenongan]written on a separate line, as in ladrang Mugi Rahayu,slendro manyura:3 y 1 • 3 y 1 n2 first kenongan3 y 1 • 3 y 1 n2 second kenongan3 5 2 3 6 ! 6 n5 third kenongan! 6 5 3 6 1 3 g2 fourth kenonganEach kenongan has a different function, position

and role, and its hierarchy depends upon its positionin the gending; this division seems to be identical withthe role of the balungan strokes in each gatra.

Each kenong unit and gong unit consists of a

melodic phrase or arrangement of melodic phrases.It is natural therefore that one way of determiningor identifying the form of a gending is by looking atthe structure of its melodic phrases. This structurecovers the number, length, type and position of amelodic phrase within a kenong unit, gong unit orthe entire karawitan composition – the gending.Since its characteristics make it similar to a gatraand cengkok, a gending therefore also:

Further, like a gatra, each gending has aparticular character, nature or feeling.

These characteristics may be summarized toshow that one gong unit of a gending has the sameor similar qualities of a gatra: it is a unit dividedinto four (or two or three parts according todifferent view points), whose functional hierarchyhas melodic movement (phrase) with a particularcharacter, which may also be called a cengkok orgongan. In other words, a cengkok or gongan orgending may also be called a gatra, or cengkok, ona larger scale or format. This is why I say that theconcept of gatra is “alive.” It is a shoot or anembryo, which will grow and develop intosomething larger, a gending.

A gatra is a unit consisting of four hierarchicalparts. The hierarchy of each part of a gatra is basedon the consideration of two important factors inkarawitan, namely:

a. Garap/TreatmentThere is no doubt that the final part of a “gatra”

(whether in a small format or large format, i.e. thefourth balungan stroke or kenongan/kenong unit)almost always has the most important position orrole. The gong in a gending or the fourth balunganstroke in a gatra is almost always the mostimportant point of reference, and often becomes thesource of almost all the instrumental treatment.Martopangrawit has strong reason to call this partof the gatra seleh. Under certain conditions or incertain cases, such as in the arrangement of abalungan (which Martopangrawit also uses for thename garap or treatment) type mlesed, mbesut andseveral other cases, the strength of this final part ofa gatra may be reduced or shifted.

This is also the case in the treatment of specialcengkok, often known as cengkok mati(Martopangrawit) or cengkok adat (I first heard thisterm used by Pak Mloyowidodo, although I laterrealized that several other musicians also used thesame term, while many others use the termcengkok blangkon), in which the last part of thegatra is not strictly the strongest, apart from the lastpart of the final gatra. This is visible in thetreatment salah gumun in which the final note of acengkok in an instrumental or vocal part deviates

Balungan 5

from the seleh note of the gatra9.From the treatment we can also learn that the

second part (balungan stroke) has the second mostimportant position after the fourth part. This issignified by the application of a cengkok or pattern oftreatment known as “separo” (half) - in particular onthe gender and bonang instruments. In certain cases(balungan arrangements), a gatra may be treated astwo separate halves, each half with its own seleh orterminal, requiring special attention as a small (seleh)terminal or seleh antara. This often occurs in abalungan arrangement or gatra, half of which uses thesame balungan pitch, known as balungan kembar ornggantung, such as in the example: 2216 (in gendingLoro Loro Topeng), in which the note 2 (gulu) is a smallterminal or ”seleh antara” requiring attention, inaddition to the note 6 (nem), which as the final note ofthe gatra of course is given more attention. Also in thecase of balungan maju kembar such as 6 3 6 5 (seeladrang Diradameta), note 3 (dada), as the second partof the gatra and note 5 (lima) as the final part of thegatra are given more attention than the note 6 (nem)on the first and third strokes.

Another example of a treatment which indicatesthat the note in the second part of a gatra is alsoimportant (after the note at the end of the gatra) iswhen there is a change in the treatment of irama, inparticular changes in irama which lengthen(Martopangrawit describes it as “widening”) thegatra, such as the change in irama from lancar totanggung, tanggung to dados, dados to wilet and soon. In line with my opinion that gatra is somethingalive, I prefer to say that the consequence of a changein irama also effects the development or change of agatra. The movement of one balungan stroke to thenext is altered, both in content and in shape. In thisdevelopment, it is possible for quite significantchanges in the balungan arrangement, reflected in thenew balungan arrangement.

IntermezzoI have great respect for Pak Martopangrawit, who

pioneered and provided a brilliant explanation aboutthe concept of (changes in) irama, as a widening ornarrowing of a gatra. In his opinion, if a change inirama occurs, this means a widening or narrowing of agatra in a ratio of 1 to 2 and multiples thereof. If agatra is widened, the gaps or distance betweenbalungan strokes will be filled by the frontinstruments (or garap instruments, to use my ownterm). As a tool to measure the level of irama, PakMartopangrawit uses the number of saron penerusstrokes per gatra or per balungan stroke.

Once again, in line with my idea of the gatra beingalive, I am more inclined to agree with him that the

gatra actually changes and develops. I do not usethe term widen or narrow but rather mulurmungkret, with a high level of tolerance orflexibility. Thus, there is also the possibility that achange in gatra is not always in the ratio 1 to 2 ormultiples thereof. In reality, in the case of gendingsekar (including palaran) and new gending in tripletime (or lampah tiga, such as the Gending LangenSekar by Ki RC Hardjo Subroto, which has beenimitated by many other “composers”; Ngimpi byPak Narto Sabdo, and Parisuka by PakMartopangrawit), the gatra can develop accordingto the creativity of the artist or the requirements ofthe age. This embryo appeared long ago when pastmaster musicians began to compose GendingMontro Madura slendro manyura and Loro LoroTopeng, also in slendro manyura (in which onegong unit consists of three kenong units), orGending Majemuk slendro pathet nem, in which onegong unit consists of five kenong units. Anothercase is Ladrang Srundeng Gosong, pelog pathet nem,in which the fourth kenong unit has six gatras.

This connection with the concept mulurmungkret of the gatra is also reflected in theconcept padang ulihan, in which the gatra in itslarger format may be flexible in size andstructure/composition of its padang ulihan, notalways balanced as in the concept maju-mundur-maju-seleh, in which the second part of a gatra (in aflexible format) “must” have the second mostimportant role after the seleh. The structure ofpadang ulihan may be P P P U, or P U P U, or P P PP P P P U, or a combination or these structures(using P for padang and U for ulihan).

There is one more point I would like to suggest inline with the concept of gatra as something alive. Inorder to identify the level of irama in Javanesekarawitan, I am inclined not to use the number ofstrokes on the saron penerus, but rather prefer touse the keteg or ketegan (pulse or beat) of thekendang. My reasons for this are:

Firstly, the word keteg has a meaningful nuancesuggesting life, such as the keteg or beat/pulse ofthe human heart. Incidentally, according toinformation obtained from a number of oldkendang players (I am also a former kendangplayer), a standard reference for the speed of anormal irama (irama dados) is to play the ketegan ofthe kendang in the same tempo (laya, irama) at thespeed of the normal adult heart beat.

Secondly, the kendang is used in almost all typesof gamelan ensemble, whereas the saron penerus isnot always present in a karawitan ensemble (suchas in gending kemanak, siteran, gadhon, palaran and soon). It is true that at times the ketegan on the

6 Volume 9–10, 2004

kendang are not clearly audible, but the keteg isalways present in the mind of the kendang player, inour minds, and in our imagination.

Thirdly, the use of ketegan kendang is in accordancewith the tradition upheld by the traditional Javanesekarawitan community, who place the kendang as thepandega, the leader (pamurba) of irama, both in termsof differences in gradation or level of dimension/sizeof gatra (in connection with the factor of space, timeand content), and in terms of tempo or laya(concerned with the element of time).

We are all aware that a change in irama (not in thesense of laya or tempo) in traditional Javanesekarawitan is a change in level (content) of the musicaltreatment in a ratio of 1 to 2 (or multiples thereof).When this occurs, then (in considerations of garap ortreatment) the notes in the second part of each gatrawill “go up in status”, as if they become the fourthnote of the (new) gatra. As such, the status of thesenotes is like that of a seleh note. The importance of thenew fourth note, as usual, is followed by the secondnote of each gatra, and this is acknowledged and feltby almost every practicing musician and theoreticianof Javanese karawitan.

In cases of changes in irama, it is possible that eachpart of the (original) gatra may have a new, moreimportant function, or may even become independent.However, it is necessary to note that in cases ofchanges in irama or changes in balungan due to thechange in form (from merong to inggah), although inprinciple the garap instruments can and may quitelegitimately use the same cengkok with differentwiledan, in practice many alterations are made by themusicians to adapt to the new balungan. See theexample of Gending Bujanggonom slendro manyura10:

Merong (with balungan mlaku)

3 3 . . 6 5 3 2 . . 2 3 5 6 5 3In the inggah (becoming balungan nibani)

. 5 . 3 . 5 . 2 . 3 . 2 . 5 . 3With the change or adaptation to the new balungan,

especially when there is a change in irama, there is anew orientation of treatment on the garap/treatmentinstruments, taking into account the new balungan. Inthe example of gending Bujangganom, the garapinstruments change their orientation to suit thebalungan changes shown in bold: 3 to 5 (at the end ofthe first gatra), and 3 to 2 (at the end of the thirdgatra).

In this case, is there actually a change in hierarchyof the position of the first and third balungan notes,and their relationship with the second and fourthbalungan notes of each gatra? Through anobservation of the treatment, there are signs of thisdifference in hierarchy. The first part (balungan

stroke) of the gatra appears to have a moreimportant position than the third. This is evidentfrom the frequency with which the first part of thegatra is used as a reference point for the treatment.This can be seen in mlesed or plesedan treatment.

The various types of mlesed in Javanesekarawitan, such as mlesed, mbesut, mungkak, andnjujug, have been discussed in depth byMartopangrawit in his book Tetembangan (1970).Mlesed is basically the way in which one or severalinstruments are played — usually kenong, bonang,rebab, gender, vocal (especially sindhen) and so on,where the final part or seleh note is not always thesame as the balungan gending, in particular theseleh note, but rather these instruments are inclinedto go past the seleh notes and lead towards thenotes, tuning or register of the next gatra or nextpart of the gending. Mlesed style of playing, orplesedan as it is often called, usually occurs when aseleh note is followed by balungan nggantung orbalungan kembar (twin balungan notes). Theinstruments or vocalist playing the mlesed styleusually refer to the balungan nggantung orbalungan kembar coming after the seleh note. Anexample of this type of balungan is:

5 6 3 5 1 1 • •In such a case, the mlesed playing of a number of

instruments and vocalist do not lead towards theseleh 5 (lima) but refer to or lead towards note 1(barang) (as the first note in the balungan kembaror nggantung). Cases of balungan nggantung orkembar may not yet give a clear enough example ofthe importance of the first note in a gatra, since inthese cases, the first note is the same as the second,which already has a strong position in the gatra.Another example is in the case of Ladrang Wilujeng:6 5 3 2 5 6 5 3

in which the seleh note 2 (gulu) is followed bynote 5 (lima); or

Ladrang Eling-eling Kasmaran:3 2 1 6 5 6 1 2where the seleh 6 (nem) is followed by note 5

(lima); andLadrang Moncer:6 5 3 2 1 6 5 3, andother examples in cengkok blangkon such as: \2 2 . 3 5 6 5 3,where the first notes following the seleh note

often become the reference point for the direction ofthe instrumental and vocal playing of a number oftraditional Javanese karawitan artists, although inthese cases, the first balungan stroke is not the startof a balungan nggantung.11

On the contrary, the third notes of each gatra, as

Balungan 7

far as I can observe, are very rarely, or even never,used as a reference point for the direction of the garapinstruments or vocalist. The third balungan stroke orpart of the gatra often even uses notes which have theweakest position in the pathet used for that gatra orgending.

Thus, the hierarchical order of the role or position ofdifferent parts of the “Gatra” (in its large format as agong or gending) in traditional Javanese karawitan(Surakarta style) is as follows:

A_ as the first part (note) of the gatra, has the thirdstrongest position,

B_ as the second part (note) of the gatra, has thesecond strongest position,

C_ as the third part (note) of the gatra, has theweakest position, and

D_ as the final part (note) of the gatra, has thestrongest position.

Or the hierarchical order of the position of strengthof the different parts of the gatra is as follows:

D _ B _ A _ Cb. Composition (Structure) of GendingIf we wish to make an analogue between gatra and

cengkok (in the sense of gongan or gong unit) andgending in (traditional) Javanese karawitan, it appearsthat the above concept of hierarchy in the parts of agatra can also be applied to the cengkok (in the senseof gongan) and gending (which is considered a gatraon a macro scale or with a larger format). The firstkenong can be compared with the first part of thegatra, the second kenong with the second part of thegatra, the third kenong with the third part of the gatra,and the gong can be compared with the fourth part orseleh note of the gatra.

As a simulation, we can observe several examples ofgending:

Gambirsawit, slendro pathet sanga12:

• 3 5 2 • 3 5 6 2 2 • • 2 3 2 n1• • 3 2 • 1 2 6 2 2 • • 2 3 2 n1• • 3 2 • 1 6 5 • • 5 6 1 6 5 n32 2 • 3 5 3 2 1 3 5 3 2 • 1 6 g5A summary of the kenong tones in one gong unit is:

1 1 3 5.Loro-loro, slendro pathet manyura:

. . . . 3 3 2 1 6 5 3 . 3 5 1 n6

. . . . 3 3 2 1 6 5 3 . 3 5 1 n63 3 . . 3 3 . . 3 3 . 2 3 1 2 n3j.12 j.13 3 2 1 6 . 6 5 3 2 1 2 g6. . . . 6 6 5 3 2 2 . 3 1 2 3 n2

6 6 . . 6 6 5 3 2 2 . 3 1 2 3 n23 3 . . 3 3 . . 3 3 . 5 6 1 2 n1. . . . 1 2 6 5 3 3 . 5 6 3 5 g6A summary of the kenong tones in the Gending

Loro-loro (gendong) is: 6 6 3 6 (in the first gong) and2 2 1 6 (in the second gong).The above examples are taken at random from

popular gending (adhakan or srambahan) as anillustration to support my hypothesis about theprofile of gatra in Javanese karawitan. I would liketo show that the third part of a gatra or (kenongunit of a) gending is the part with the weakestposition; weak in terms of the notes in the selehposition for the kenong — especially from theperspective of garap or treatment — but also weakin the context of the function of the note in theperspective of a particular pathet. It is believed thateach note has a particular hierarchical function ineach pathet.13

Although until now there is no strong consensusabout which note has what function in a particularpathet, nevertheless the hierarchical function of anote is still felt and believed to be present. Researchand discussions on this topic are always interestingand still necessary.

Whether we realize it or not, the tradition ofmaking the third part of a gatra or gending theweakest part can be understood logically (at leastaccording to the reasoning of the writer, as both apractitioner and composer of new traditional andnew experimental gending). It is because of itsweak position, on the third stroke immediatelybefore the end of the gatra or the final kenong(approaching the gong), that this part of the gatrahas the function and position as a preparatory partor bridge to strengthen or solidify the position ofthe seleh or gong as a terminal with the strongestposition. For this purpose, it is necessary to havetwo contrasting positions side by side, or in otherwords weak followed by strong.

Also in connection with the need to strengthenthe position of the final part of the gatra or gong ofthe gending, it is sometimes also necessary to“lengthen the duration” of the seleh part, forexample, by repeating the final note or part of thegatra or gong. In Javanese karawitan, thislengthening is realized in the form of nggantung orrepetition. This is frequently used in Javanesekarawitan gending in the form of short extensions(one balungan stroke) or longer extensions (severalbalungan strokes or several gatra, or even severalkenong).14

It is necessary to explain that the understanding

8 Volume 9–10, 2004

of balungan nggantung is not merely limited tobalungan kembar or balungan pin (empty), but alsoincludes other balungan arrangements which give theimpression of “remaining” or staying on (around) aparticular area of sound (note). Inexperiencedmusicians sometimes have trouble identifying thistype of balungan nggantung, as feeling plays animportant role in this identification, even more so inbalungan nibani and also in balungan tikel. A fewexamples of balungan nggantung are:

3 3 . . (Wilujeng)

3 2 1 . (Umbul donga)

3 5 2 3 (Mugirahayu)

6 3 5 6 7 6 5 6 (Tropongan)

.1.6 .5.6 .5.6 (Gonjang-ganjing)A number of illustrations of balungan arrangements

of the nggantung type are as follows:Kawit, slendro manyura, after gong 3 (dada):• • • 3 • 1 2 3 • 1 2 3 etc.In this example from Gending Kawit, the gatra• 1 2 3 is shown with an empty balungan

(balungan kosong) in the first part of the gatra, which isa short extension (one balungan stroke) of the seleh inthe previous gatra – note 3 (dada). This example alsoillustrates the importance of the position of the firstpart of the gatra, by filling it with the same note as theseleh note, note 3 (dada). This type of balungan ismuch more frequent in thousands of other (parts of)gending than a balungan with nggantung (pin orempty) in the third balungan stroke (part) of a gatra,such as the example: 1 2 • 3. In Gending Kawit,there is also an example of a longer extension of aseleh note, lasting one gatra plus an extra balunganstroke, such as the example: 3 • • • 3 • 1 2 3.This type of balungan is also found in thousands ofother Javanese gending. A longer example may beseen in Gending La-la:

5 • • • • 5 5 • • 5 5 • 3 5 2 3 5 etc.In a larger format, the form of extension may be a

repetition of a kenong phrase, in which the final noteof the kenong is same as the gong note. An example isGending Kutut Manggung is as follows:

g1 . . . . 1 1 2 3 5 6 5 3 2 1 2 n1 . . . . 1 1 2 3 5 6 5 3 2 1 2 n1Similar examples can be found in hundreds of other

gending in the Javanese karawitan repertoire, such asin Titipati, Majemuk, Widasari, Lobong, and Loro-loro.Some repetitions last for more than two kenong units,such as in Gending Damarkeli, Ladrang Bedhat,

Ladrang Sumirat and Ladrang Bolang-bolang.15

Likewise, the part repeated also varies. It may bethe first, second or third kenongan or the gong, aswell as other parts (the middle) of the gending.

An example is gending Ladrang Sumirat slendromanyura:

A 5 6 5 2 5 6 5 n35 6 5 2 5 6 5 n35 6 5 2 5 6 5 n3! 5 6 • ! 6 5 g3

B ! 5 6 • ! 6 5 n3! 5 6 • ! 6 5 n3! 5 6 • ! 6 5 n35 6 5 2 5 6 5 g3

The first kenong is repeated in the second and thirdkenong, or since a performance of a gending inJavanese karawitan may be repeated in every part,the three above kenong units may be considered arepetition of the fourth kenong. This kind ofexample occurs in many gending, for example in:Ladrang Wilujeng

2 1 2 3 2 1 2 n63 3 • • 6 5 3 n25 6 5 3 2 1 2 n62 1 2 3 2 1 2 g6

in which the first kenong is a repetition of the fourthkenong, not the fourth kenong a repetition of thefirst kenong.

From the above illustrations, the parallelism andsimilarity of the hierarchy of the gatra (and itsparts) and the gending become more evident. It isnatural and cannot be denied that the larger theformat (such as in an example of a gending in theform kethuk 4 awis or kethuk 8 kerep), the moredifficult it is to trace this parallelism or similarity.This is, once again, due to the live nature of thegatra, whose changes and developments areextremely flexible according to its time, place andfunction, and also depend on the musician or artist,which is also connected with its cultural context(Supanggah, 1985). Nevertheless, the hierarchicalregulations within the gatra, both in its small and

Balungan 9

large format, are basically consistent with, and do notfall far short of, this discussion.

Changes in Format or ScaleIn the tradition of Javanese karawitan, a change in

format or scale is not uncommon. This may be seen inthe reduction or diminution of a number of gending,such as Gending Rondhon kethuk 4 arang, which isreduced to Rondhon Cilik, kethuk 2 kerep, GendingRenyep kethuk 4, which is reduced to Gending Renyepkethuk 2 kerep, Sangupati kethuk 4 arang, which isreduced to Sangupati kethuk dua kerep and so on. Thisreduction or diminution of gending also occurs inlong gending, which are shortened while retaining thesame form, such as in the version of Ladrang Playonpelog lima with 13 gong units, which is shortened tobecome Ladrang Playon with three gong units, orGonjang-ganjing (Lik – Tho) slendro sanga with threegong units, which is shortened to become GonjangGanjing (bedayan) with two gong units.

Changes in format can also occur in the oppositedirection, in the form of enlargement or expansion offormat. Many cases of this can be found in gendingyasan Kepatihan (from the first half of the 20thcentury). One example is Gending Wilujeng kethuk 2kerep, which is an enlargement of Ladrang Wilujeng.Other examples are Gending Siyem, GendingBrongtamentul, Gending Kapidhondhong and so on(Mloyowidodo, 1976 vol. 3). This enlargement offormat accompanied by a change in form can also beseen in certain cases of gending sekar, which arebasically a change or development in form from avocal performance (usually sekar macapat, tengahanand/or bawa) in irama mardhika or free irama, whichare then treated to become more fixed and at timeseven metric, according to the frame of the gending,which already has a certain form, such as ladrang,ketawang, or other forms such as ayak-ayakan orsrepegan. From this point of view, in fact, gendingpalaran can also be included in this category ofgending sekar. Gending palaran is also a concreteexample of a case of developing the gatra with theconcept mulur mungkret.

Changes in format and/or form occur or arespecifically used when there is a change in function,use or contextual change of a gending/karawitan.Cases of gending Bedhaya, Srimpi and Wireng are clearexamples of a change in function of gending klenenganto become gending beksan. Likewise, examples ofgending dialogue used in theatre or the performingart forms Kethoprak and Langendriyan show a change infunction from vocal pieces or tembang to becomegending sekar: gending Ketoprak and gendingLangendriyan.

Whatever the direction of the change in format and

form (whether enlargement or reduction), theresults of the change still appear to adhere to thenorms of the concept/character of gatra, which isalso the core idea or concept of gending in Javanesekarawitan.

CharacterIn connection with the fact that gatra (in all its

formats and dimensions) has a form or shape,determined partly by its step, structure, contour,register and especially treatment, there are a varietyof different characters of a gatra (or gending). In thetradition of Javanese karawitan, these characters areoften described as rasa (feeling). There are gendingwith the character regu (powerful), tlutur (sad),sigrak (joyful), gecul (humorous), prenes (romantic),gobyog (lively, fresh and entertaining), sereng(angry), and so on. In accordance with my beliefthat a gending only exists when it is performed by agroup of musicians or vocalists, in fact the feelingof a gending is relative and highly dependent uponthe artists themselves (and the various factorsinfluencing their backgrounds), within theframework of its space, time and function – bothaesthetical and contextual.

However it cannot be denied that the character ofa gending can also be determined by its gatra orarrangement of gatra. Numerous gending may beidentified by the arrangement of gatra, whichsometimes may be found only in a particulargending. An example is:

5 5 . . 5 5 . . 5 5 6 5 3 5 6 1. . 3 2 . 1 6 5 3 5 . 2 3 5 6 5A musician will quickly identify this balungan or

arrangement of gatra as Gending Laler Mengengslendro sanga. Likewise, the balungan orarrangement of gatra:

4 3 4 . 4 3 4 . 4 3 4 6 4 3 4 2will be identified as Gending Tukung pelog barang,or:

• • 7 6 5 3 2 6 • • 7 6 5 3 1 2will be identified as Gending Miyanggong pelognem, and so on.

On the contrary, the balungan or arrangement ofgatra such as:

2 1 2 • • 1 2 6 3 5 6 ! 6 5 2 3 or

• 6 5 • 5 6 1 2 1 3 1 2 • 1 6 5 or

2 3 2 5 2 3 5 6 6 6 7 6 5 4 2 1and many other examples may be found in almostall gending in that particular pathet. This type ofbalungan or arrangement of gatra is what I have

10 Volume 9–10, 2004

described as balungan adat or blangkon.The method of identification of a gending from the

arrangement of its balungan/gatra with a particularcharacter, whether highly specific, rather specific, orwith gatra or cengkok adat, was often used by oldmaster musicians (at least until the 1970s), when theywere training or teaching their pupils to memorize,master or treat “new” gending. For example theteacher would shout “Klewer!” when the pupils wereplaying gending Endol Endol pelog pathet barang. Thismeant that there is a particular part of gending EndolEndol that should be treated in the same way asgending Klewer, which has a part similar or the sameas part of gending Endol Endol. Likewise, the teacherwould shout “Adat!” when the student reached thepart of a gending similar to that found in many othergending in the same pathet. Complete or totalidentification (of the balungan/gatra arrangement,irama, patet, and instrumental treatment or garap)became an important part of the oral system used.

In order to obtain accurate results, it is necessaryand in fact essential to carry out more in-depthresearch, accompanied by statistical analysis of theentire population of gending in the Javanesekarawitan repertoire. It is important to be aware toothat karawitan, as with other art forms, also has someworks or actions containing exceptions, for creative orinnovative purposes, to create a surprise, or for otherpurposes of artistic expression. However, as a branchof the traditional arts, karawitan is also inclined todisplay certain regularities, similarities andregulations or even rules, all of which provide aunique character for traditional Javanese karawitan.

EpilogueAlthough the material in this paper is not yet

supported by data covering the whole repertoire ofJavanese karawitan gending, I would hope that thereader could gain a picture of the gatra as animportant concept in the vocabulary of karawitan“knowledge”. The gatra, with its various elements andcharacteristics, is also the core of the conception ofcengkok (gongan) and also traditional Javanesekarawitan gending. The gatra can no longer beseparated from the cengkok, wiled, kenongan,gongan, gending, and so on.

The understanding of the core of (the cengkok, orgongan, of) the gending is not necessarily the same asthe understanding (with a nuance of meaning similarto the gatra) of theme or motif in the world of westernmusic. The theme or motif in the world of westernmusic is also the core of a western (classical) musicalcomposition. The theme or motif is a musical idea(melodic or rhythmic), which provides the basis orframe of a composition. This theme or motif is often

repeated, imitated, altered and developed by theinstruments, in the hope of unifying thecomposition by reminding or “binding” the listenerso as not to break free from the composition. It isthe highly flexible and imaginary nature of thegatra that distinguishes it from the concept oftheme or motif, the realization of which is clearlyidentifiable to our ears, in addition to its othercharacteristics mentioned above. It is quite possibletoo for the idea of theme or motif (in traditionalwestern music) to be applied to the world ofkarawitan, especially in new works which arebeginning to be more individualistic. It is clear thatSri Hastanto in his composition Ro-lu-ma-nem (2356)and Supardi in his composition Lu-ro-ji-nem (3216)used an approach with a sense of theme or motifcommonly used in western classical music. This isespecially evident in Sri Hastanto’s composition,while Supardi develops the concept of the gatra3216 in a more variational and complex exploratoryway.

I have carried out this small scale and incompleteresearch independently and in a relaxed way in thetime available amidst my day-to-day activities. Ihope that it will provide both stimulation and acontribution to the formation of karawitan theory,and also for the purposes of creative activities suchas the appearance of new karawitan treatment andor new karawitan compositions. If this research iscontinued, in a more serious and proportional way,we will of course obtain much better results (andperhaps also theories). Hopefully this hypothesiswill become positive and be accepted.

We are aware of the importance of this concept ofgatra as a starting point for subsequent work, suchas a tool for the analysis of treatment (garap),pathet, composition, and other types of analysis inthe field of karawitan. At least from the explanationof the concept of gatra, we are able to understandthe position of (the concept of) gatra and relate it toother concepts in the constellation of concepts inJavanese karawitan. As we have all read, at presentmany theoreticians of karawitan carry out theiranalysis using the balungan or gatra as the object ofanalysis. Without knowing more about the gatra,with its character, nature and form, including on animaginary level, I can guarantee that their resultswill be far from satisfactory, however good themethodology used.

Karawitan knowledge or theory is a new theory,which is beginning to grow, be built and developedin Indonesia. Its material, knowledge and conceptsare in fact quite complex and abundant, and stillscattered all over the place. These conditionsprovide a challenge and also an opportunity

Balungan 11

requiring our willingness to approach, collect, compileand develop them into a firmer cluster of theories. Insuch a situation, we believe that however small theresult achieved, it will still have great value andsignificance in the development of the world ofkarawitan theory.

In the world of practical karawitan, the gatra alsohas an important role as a point of reference for thework of karawitan artists or musicians in playing andtreating their instrumental and vocal performance.This is also the case in efforts to develop creativeactivities such as creating new compositions orgending, new vocabulary for garap (cengkok orwiledan), and so on.

For this reason, once again with all limitations andwith the classic reason — time and costs — I wouldlike to put this small and simple observation of one ofthe important concepts of karawitan, gatra, to thereader, to obtain a response, criticisms andsuggestions. I would be delighted if these ideasmanage to rouse us all into undertaking more intenseresearch or studies for the sake of developing ourknowledge of karawitan.◗

Notes1 Its use was made popular through theory andpractical karawitan lessons at KOKAR, by R.M. PanjiSutopinilih.2 It is customary in Javanese society to associate thevocal sounds “o” or “ong” with greater importancethan the vowels “u”, “a”, “e” or “i”, or each of thesevowels with the ending ng. As an example, theJavanese often refer to the sound gong (with the vowel“o”) as more impressive than the sound gung (with thevowel “u”), as is often used to describe the sound of akempul, even more so compared with the sound ging(with the vowel “i”), which has the impression ofsomething even smaller or with a higher pitch, such asthe sounds of the kempul with barang pitch (1) andmanis (2).3 Although some people believe that the regulations orstandardization of treatment or garap, including thebowing for the rebab, were established during theKepatihan (Wreksodiningrat) era, at the turn of the 20th

century.4 In this nggantung, a high degree of creativity isdemanded of the musician. As in the case of gendingpilaran, the level of artistry of agender/gambang/siter/kendang player is visible fromthe way in which they treat the nggantung part.5 Sumarsam, Inner Melody, Master’s Thesis inEthnomusicology, Wesleyan University, 1976.6 Marc Perlman, Unplayed Melody, dissertation inEthnomusicology, Wesleyan University, 1993.

7 As we know, other types and forms of gendingsmaller than kethuk loro kerep are usually called bythe form or name alone, such as Ayak-ayakan slendromanyura, or Ketawang Sinom Parijatha or Jineman UlerKambang, and are rarely called by the name ofGending Ayak-ayakan slendro manyura or GendingKetawang Sinom Parijatha or Gending Jineman UlerKambang, or by the name Sinom Parijatha, GendingKetawang or Uler Kambang, gending jineman, such asin the case of Onang-onang, gending kethuk kalih kerepminggaah kethuk sekawan, and so on. It is possible thatin former times, musicians consciously onlyregarded a composition of Javanese karawitan as a(“standard”) gending if it was kethuk loro kerep orabove. Other compositions would then becategorized merely as “songs” (“lagu” or “lagon”).8 As we know, the form of a gending, in addition tobeing determined by the number of balunganstrokes in each gong unit, is also determined by the“tapestry” or structure/pattern of the structuralinstruments (ketuk, kempyang) and the compilationof musical phrases within a gong or kenong unit.9 Cengkok mati or adat or blangkon are usually a seriesof treatments (melodic or rhythmic) requiring aframework for treatment or performance time longerthan a single gatra (measuring the performance of agending in irama dados).10 See also Supanggah “Balungan”in Balungan.11 In writing these examples, the seleh notes arewritten in bold print and the nggantung notes areunderlined.12 Take the example of Gambirsawit, as not only isthis gending known among all karawitanpractitioners and theoreticians but it is alsoconsidered to have a pathet which is “pure” slendrosanga.13 See also Sindusawarna, Martopangrawit, MantleHood, Judith Becker, Sri Hastanto, and others.14 A more detailed explanation of nggantung can beseen in Marc Benamou’s thesis (Benamou 1990).15 See also Gending Gongjang Anom Pelog Nem,ketuk 8 kerep minggah ketuk 8, the longest gendingin the repertoire of Javanese gedning in Surakartastyle.

Balungan 13

TRADITIONSWayang Wong Priangan: Dance Drama of West Javaby Yus Ruslaiana

Translated, edited, and augmented by Kathy Foley

The relationship between human performanceand puppetry in Indonesia is strong. If wayang wongjawa (Javanese dance drama) is a reflection of wayangkulit , the leather shadow puppetry of Central Java,which uses humans as actors (Soedarsono, 1997:1),then wayang wong Priangan, the dance drama ofPriangan—the mountainous highland area of WestJava— can be spoken of as a personification of wayanggolek, the wooden three-dimensional puppetry of theSundanese speakers who live in this highland area ofWest Java.

Performances borrow from the repertoire of thisimportant puppet theatre in which stories of theMahabharata, Ramayana, Arjuna Sasra Bahu andMenak cycles are performed. As in wayang golek adalang (puppet master) delivers narration and moodsongs. The musical repertoire of wayang golek’sgamelan is used the performance structure adoptspupptry’s patterns. Differences are that in wayangwong (called wayang orang in Indonesian) thechoreography performed by individual dancers ismore complex than that executed by the wayanggolek dolls; the dialogue is usually delivered by eachdancer representing his or her character rather thanby a solo narrator/puppeteer; and the performance ismore streamlined, lasting a mere two to four hoursrather than the seven or eight of a puppet play.

Wayang wong Priangan developed in the latenineteenth century, peaked in the regencies ofBandung, Sumedang, Garut and Sukabumi in theperiod before World War II, and receded by the latel960s as audiences waned. This article will introducewayang wong Priangan, detailing its history andaspects of performance practice and repertoire.History

Wayang in Kawi (Old Javanese) means “shadow”and wang means “human.” Wayang wang was aperformance in the style of wayang kulit, the shadowtheatre of Central Java wherein actors and actressestook the puppets roles. The first written reference to

the form is on the stone inscription Wimalarama fromEast Java dated 930A.D. (Soedarsono, l997: 4-6) Thegenre is currently done in masked and unmaskedvariations in Central Java, Bali, and Cirebon (a city onthe north coast of West Java), as well as in Sunda(West Java).1 Since Cirebon’s wayang wong is thedirect antecedent of wayang wong Priangan,understanding Cirebonese practice is important to thediscussion.Wayang Wong in Cirebon

Cirebon has two styles of wayang wong. The firstis a village version in which the performers aremasked. 2 The second is a palace variant where theperformers dance unmasked. Cirebonese wayangwong developed in the beginning of the nineteenthCentury and fed into the wayang wong Priangan bythe end of that century.

From 1811 to 1816 the English were a colonialpresence in Cirebon. When they left, they werereplaced by the Dutch. In this period the palaces ofthe Kanoman and Kasepuhan were centers of culturalconservation and artistic development.3 These kraton(palaces) encouraged the artistic practice of the villageperformers as well as supporting presentations byartists who were of noble descent. For example, theKanoman Palace records note a performance in 1842of a badaya (female court dance) done by sixperformers which drew on the Menak cycle, a legendthat tells the history of Amir Hamzah uncle of theProphet Mohammed (Soedarsono l972: 115-6). Later,during the reign of Sultan Raja Zukarmaen (l873-1934) and Sultan Anom Nurbuat (l934-5), attention tothe arts continued at the Kanoman. Palacechoreographies included a badaya rimbe (a femalegroup dance performed by the Sultan’s femaledaughters), which was last performed in l966 at aKanoman circumcision. Wayang wong, presentingtales from the Amir Hamzah repertoire. Kanomandancers performed wayang wong without masks andcharacters spoke their own dialogue while the dalang

14 Volume 9–10, 2004

delivered only the mood songs (kakawen/ suluk), andnarration (nyandra). Performers were generally villageartist who were given rights to work lands andconsidered abdi dalam, retainers of the ruler. Someartists, especially dalang, were given the title NataPrawa. Palace performances were open to the publicby l925, but as the patronage of the palace falteredwith independence and economic dearth, wayangwong ceased by l966 due to lack of funds.

The wayang wong which was favored at theKasepuhan palace was different. There a villagetroupe which would be invited into the palace toperform for Islamic holy days, for life-cyclecelebrations, and for exorcistic ceremonies (ruwatan).In the period of Sultan Raja Atmaja (1880-1899) thetroupe of Dalang Resmi was most noted. There weremany artists especially from the surrounding villagesof Mayung, Gegesik, Palimanan, Slangit, andSuranenggala. These performers were allowed towork royal land and might be given titles. Forexample, Dalang Kandeg, one of the most notedCirebonese artists of the last generation, was giventhe title Patmadjawinata, while Dalang Dirja receivedthe title of Ngabehi. Such individuals also were giventhe honorific title Ki or Kyai . These two dalangs andtheir troupe were frequent performers in the palaceperformance halls, Pringgondani and Srimati,between l939-l942. Their performances included wellknown wayang stories such Pergiwa-Pergiwati, JabangTutukla, Gandamanah, Brajamusti—stories named aftertheir featured character—The Forest of Alas Amer,Somantri Breaks his Vow, Partakrama (Arjuna’sWedding), Campang Curiga, Prabu Kuliti KunmbangAli-Ali (Mintaraga/Arjuna’s Meditation), and, for theexorcism, Batara Kala (The God/Demon Kala).Costumes and masks for these performances followedthe iconography of the wayang kulit shadow theatreof Cirebon. (Pigaud, l938: 120). The batik cloth inwhich dancers would wrapped themselves waspainted with the traditional designs of Cirebon. In theKasepuhan performances the dalang delivered all thedialogue as well as the mood songs and narration, ashe would in a puppet performance. Movement was inthe style of Cirebon topeng (mask dance). Palaceperformance used both the slendro prawa and pelogorchestras. Performances outside the palace, bycontrast, were more modest would use only one set ofinstruments tuned to either the slendro or pelogscales.

The Kanoman Palace developed an aristocratic,unmasked variant of wayang wong where performers

were nobles or their retainers. The maskedKasepuhan Palace model was dominated by villagersand these performances were more suffused with avillage aesthetic. The former style needed manytrained palace performers, but the latter style was thepurview of professionals/semi-professionals. Thissecond group would in the late nineteenth centurycarry the art to the Piangan highlands, travelling forparts of the year as itinerant troupes.Wayang wong in the Priangan area

According to Pak Kandeg, the most authoritativeCirebonese wayang wong dalang of the lastgeneration, a dalang by the name of Ki Kempung wasthe first to tour the genre outside the palace and toPriangan while the second was NagbehiNatawigunan (Maman Suriaatmaja 1970: 236).Performances could be of two types: firstly, that hiredfor a set fee by a family or group holding a ceremonyor celebrating a festive occasion, or, secondly, paid forby viewers who purchased individual tickets. Thelatter type of presentation was called bebarangan orngamen (itinerant performance). As these groupstraveled, wayang wong spread to major cites of theSundanese area such as Sumedang, Garut, Sukabumi,and Bandung.

The dalangs of this time who were best knownwere Wentar and Koncar. Wentar’s given name wasKundung, but he received the nickname Wentar(kawentar, “famous”) from R. A. A. Martanegara, theregent of Bandung at the turn of the twentiethcentury. Wentar was patronized by the aristocracyand was known for teaching topeng-style mask danceof Cirebon to highland nobles. Meanwhile Koncarwho was closer to the commoners, focused onperforming wayang wong with his troupe for hislower class audience. Originally the dialogue used bysuch troupes was in the Cirebonese dialect ofJavanese, but soon the local Sundanese language,which could be understood by the viewers, wasemployed. According to Dalang Kandeg, the realname of Koncar was Ki Konya. The moniker Koncarcomes from kakoncara, meaning “well-known.”Wentar helped lay the groundwork for what wouldbecome known as wayang wong priyayi (literally,“civil servant” [i.e., upper class] wayang wong) as hetrained members of the aristocracy in danceperformance. Koncar whose work was later continuedby Dalang Kamsi, popularized the genre among thehoi poloi. Due to this pair and their followers, by theend of the nineteenth century we find wayang wong

Balungan 15

Priangan developing in the highlands of West Java asan indigenous performance.

On January 1, 1871 the Dutch colonialadministration implemented re-organization of thePriangan area by assigning a Dutch resident officer tooversee several regents, called bupati. It was in citiesoverseen by these bupati, that wayang wong laterflowered. Let us consider some of the developmentslooking at the cites closer to Cirebon first.

Sumedang is the gateway to Priangan fromCirebon on the north coast. Prince Suria KusumahAdinata (l836-l882), the bupati of Sumedang was awayang aficionado and ordered palace dancers to betrained in wayang wong. He determined that thefemale dancers would wear masks while headdressesfor his troupe were made of copper or tin (Pigeaud1938,121). In 1893 it was similar headdresses that thenext Bupati of Sumedang sent to the ColombiaExposition in Chicago along with the gamelan setcalled Sari Oneng Parakan Salak, a set of nineteenthcentury instruments (Abdullah Kartabrata l996: 9,41).4

Garut is also close to Cirebon. This was whereWentar and Koncar had found audiences at the end ofthe l9th century. The dance training given by Wentarcontributed to the development of wayang wongamong the upper classes in that city. During the timeof Bupati R.A.A. Suryakartalegawa (l915-1931) therewas a group of wayang wong priayayi. In the l920s itwas sponsored by the kabupaten, the government ofthe area, and all performers were civil servants, whowere the elite of that time. Mahabharata stories wereperformed on major holidays. No masks were usedand dancers spoke their own lines. No clown roleswere included, perhaps because it was difficult to findpriyayi who were the right types and/or willing toplay the comic roles. Also in Garut, Dalang Bintang(“Star”) from Tarogong began to perform wayangwong Priangan after he married a daughter of DalangKoncar, who was his teacher. Dalang Bintangperformed with his wayang golek apprentices. Thegroup used masks. All the dialogue was initiallydelivered by the dalang. But, in time, the groupdiscarded masks and performers began to presenttheir own dialogue. Mahabharata, Arjuna Sasra Bahuand some sempalan stories were in their repertoire.5

Bandung, the present capital of West Java, isfurther from Cirebon and the coastal influencesarrived here a bit later. Here the arts were supportedby Bupati R .A. .A. Martanegara who ruled l893-1918.A building in the official complex of the kabupaten

was called the Hall of Priangan Culture. Here dance,music, and theatre were practiced. The arts werelinked to status and class. By the l920s, Bupati R. A. A.Wiranatakusumah V, known as Dalam Haji, (1920-31and l935-42) led the regency (Nina H. Lubis, l998:315). Under Wiranatkusumah’s leadership priyayipresented maskless Mahabharata episodes with thedialogue spoken by the dancers. Costumes followedwayang golek iconography and the group performedfor congresses and major holidays. R. SambasWirakusumah excelled as the knight Laraskonda andR. Tjetje Somantri as Baladewa (R. Tjetje Somantri1948: 4). These two individuals were to become themost noted dance masters of the twentieth centuryand their legacies in Sundanese dance and theatreremain profound. While the bulk of performers at thekabupaten in Bandung were priyayi, musicians andfemale performers were drawn from the lower class.

Outside the kabupaten, these priyayi artistssometimes developed their own ensembles, as did R.Sambas Wirakusumah when he became headman(lurah) of Rancaekek near Bandung. In the l930s inCimindi to the east of Banding, another group wasestablished by Ibuk, who himself was a pupil ofDalang Oneng from the city of Sukabumi. This troupewas known for its cross-gender casting. Womenpresented refined knights and men played femalecomic roles. In l938 in Babakan Tarogong KotaprajaBandung, another troupe, wayang wong Kayat, led byPak Kayat was established. This group was oftenhired to provide entertainment for family ceremonies.It also staged ticketed performances. Dancerspresented their own dialogue with the dalangproviding only mood songs and narration. Theperformance, as with other troupes, followed wayanggolek’s model.

After independence the pendapa, the open airpavilion, of the Bandung kabupaten was no longerused as a performance or training space, and wayangwong’s future was fully in the hands of the commonpeople. Many of the great artists of the periodparticipated in the genre. R. Sambas Wirakusumahcontinued to be active. In l957 he gave a performancewhich included music by the noted artist R. NugrahaSudireja, narration by Dalang Iding Martawisastra,and direction by Enoch Atmadibarata (a majorchoreographer and scholar of the present) in aperformance of the Birth of Gatotkaca. (Yuli Sunarya,l997:99) This performance was more structured thanthose of an earlier period. The dialogue was based ona set text rather than improvised in performance as

16 Volume 9–10, 2004

earlier was the norm. The choreography and positionson the stage were predetermined rather than left tothe discretion of the performers, and the transitionswere worked out. In such performances the fluidity ofthe past with its reliance on the choices of the trainedindividual artist was being replaced by a moreunified and predetermined aesthetic. In the postWorld War II period, Kayat revived his group and itbecame a training ground for many artists of thepresent. But by the late 1960s there was little demandfor performances of this genre. By l968 Wayang wongKayat found annual independence day celebrationsthe only call for its artistry. Unneeded, artist retreatedto wayang golek or migrated to other genres such assandiwara (improvised drama where dance isdeemphasized and the repertoire is not confined tothe wayang tales) and sendratari, which forgoesdialogue in favor of mimed action.The Troupe

A troupe of wayang wong Priangan wouldinclude dancer-actors (penari), a dalang to narrate,musicians (wiyaga or nayaga) to play the gamelan, anda female singer (pasinden or juru kawih) whose lyricscomplemented the show and filled in during

the scene transitions. Dancers were usuallyassigned roles by the troupe leader, often the dalang,who in casting took into consideration the performersability in dance and speaking. Seasoned performersusually had a character that was considered theirspecialty (kostim). All roles were not equallydemanding and performers fell into three groups.Primary players (wayang utama) played the core rolesin the story presented. The dancer who played aheroic roles was apt to become the idols of theviewers. The antagonist was equally necessary for theconduct of the story and would portrayed the villain.Secondary characters (wayang pamanggul) supportedthe hero or villain. Supporting characters (wayangpangeuyeub) took minor roles such as rank and fileogres.

The dalang was usually not responsible for thedialogue, but provided the mood songs andnarration. Additionally this performer cued thegamelan with the wooden hammer (cempala) and metalplates (kecrek) which he used to accent the movementof the dancers and to make sound effects whichenlivened the energy of the scene. Unlike wayang golekwhich since the l960s has allowed female dalang, thedalang of wayang wong was always male.

There were about ten musicians who played the

gamelan instruments which consisted of a bowed lute(rebab), drums (kendang and kulanter), metalophones(saron I, saron II, the deeper-voiced panerus), thehorizontal gongchimes (bonang, rincik), a xylophone(gambang) and set of large hanging gongs (goong,kempul). One female singer who was called pasinden orjuru kawih was customary. Among the musicians, thedrummer had a preeminent role as he set the rhythmand provided percussive accent for the movements ofthe dancers.

Balungan 17

Chart A: Character Types

The following chart details the character types that would be found in wayang wong Priangan with examples ofwell-known characters that fall into that type and notes on their movement and vocal practice. (Characters fromthe Mahabharata are designated by an M, Ramayana with an R and Arjuna Sasra Bahu by ASB.)

Type Characteristics, Dance Steps, Voice CharactersPutriLungguh

Refined female who moves in slow sustained style. Names of signaturemovements include adeg-adeg lontang nutpup (stance with closedarms), jankung ilo reundeuk (low approaching movement), keupat anca(refined walking). She speaks in suara biasa or regular voice.

Subadra (M),Drapadi. (M), Sita(R), Citrawati (ASB)

Putri Ladak Semi-refined female who moves more quickly, but is still refined.Signature movements are adeg-adeg lontang buka (stance with openarms), jankung ilo batarubuh (approaching movement with shouldermovement), and keupat salancar (medium walking). She speaks in suarabengek or high voice.

Srikandi (M),Mustakaweni (M),Rarasati (M), Trijata(R)

SatriaLungguh

Refined knight who moves in a sustained, slow way but has a widerstance than the putri lungguh. Movements include keupat anca (refinedwalk), adeg adeg baplang (stance to the baplang rhythm), and tincak tilu(stepping in threes). He speaks in suara biasa or regular voice.

Arjuna (M),Abimanyu (M),Yudistira (M), BataraGuru (M), Rama (R),Arjuna Sasra Bahu(ASB)

SatriaLadak

Refined knight who moves in a medium tempo but more directly andenergetically than the refined character. Movements included keupatsatria (knight walk), ecek, santana (side stepping), and adeg-adegsembada (semi-refined stance). He speaks in suara bengek or high voice.

Kresna (M), Karna(M), Somantri (ASB)

MonggawaLungguh

Refined warrior who stands in a wide stance, his head low but histempo even but rather fast. Movements include adeg-adeg capang(stance fixing armbands), jankung ilo cikalong (strong approach), gedut(striding), gedig anca (small stepping with weight transfer). He speaksin suara gangsa or deep voice created by tightening vocal cords.

Gatotkaca (M),Antareja (M),Hanoman (R)

MonggawaDangah

Proud warrior who is aggressive and uses dynamic movement.Signature steps include adeg adeg capang sonteng (stance fixingarmbands dynamically), pak blang (stepping forward and back to thepak blang drum pattern), and gedig salancar (wide stepping withweight transfer.) ). He speaks in suara gangsa or deep voice created bytightening vocal cords but using a quick and somewhat forced tone.

Baladewa (M),Jayadrata (M),Suyudana (M),Inrajit (R)

DanawaPatih

Ogre minister who has a wide stance but whose head is down a bit, andmoves in a steady and rather quick tempo, gazing straightforward.Movement include adeg adeg japang ngalaga (stance fixing armbandsfor battle), sirig and jankung ilo batarubuh (approach with shouldertapping). ). He speaks in suara gangsa with a deep voice created bytightening vocal cords.

Sakipu (M),Brajamusti (M)

Danaw Raja Ogre king who has straight wide leg stance, energetic and fast rhythm,and straightforward and high gaze. Movements include adeg-adegkiprahan (preening stance), banrongsayan, pak blang gancang (faststepping forward and back to pak blang rhythm), gedig barungbang(strong stepping with weight shift). ). He speaks in suara gangsa or deepvoice created by tightening vocal cords, but voice can swoop up anddown and the breath is forced.

Naga Percona (M),Niwata Kawaca (M),Rawana (R)

Pawongan Clown servant with comical and exaggerated movements. Specificvoices are prescribed for each of the clowns. They appear in all the storycycles whether Mahabharata, Ramayana or Arjuna Sasra Bahu.

Semar, Cepot,Dawala, Gareng

18 Volume 9–10, 2004

Performance Practice

Dance is especially important to depict battles,and these dance confrontations are of three types.Solo Battles called perang tanding (battle duel),which will be discussed at greater length below.Perang rempugan is when a hero or heroine fights 2-3 opponents simultaneously as when Abimanyu isslain by the Kurawa in the Mahabharata. Perang balad(battle of the rank and file soldiers) pits groups oflow class characters against one another, as whenthe rank and file of the Kurawa army face the footsoldiers of the Pandawa in the Mahabharata.

Perang tanding is a pair battle that can takemany variations. It may be a dance battle betweennobles in which case it is called perang tanding satria.Two knights one refined (lungguh) and the secondsemi-refined (ladak) confront each other with therefined one winning, as when the refined Pandawahero Arjuna fights his semi-refined half-brotherKarna on opposing sides in the Bharata Yudha.Another example is when the semi-refined Ekalaya,an uninvited student, is defeated by the refinedArjuna at the order of their teacher Dorna. A finalexample is the refined Raja Arjuna Sasra Bahu in theepic cycle named after him, who is an incarnation ofthe god Wisnu (Vishnu) and defeats the semi-refined Somantri who will later become hisminister. In each of these instances, the refineddefeats the semi-refined. This loss supports theideological order of the wayang universe. In wayang,the most refined always wins, in spirit if not alwaysin fact.

It is not customary for knights of the samecharacter type to battle. A lungguh character willnot oppose another lungguh figure. Perhaps this isbecause the redundancy would contradict theideology behind. A truly refined character is neverthe attacker, hence, there can be no challenge tobattle when two lungguh characters meet

While not strictly perang tanding, another pairsbattle pits two females against one another. Themartial wife of Arjuna, Srikandi, often stars in thesescenes—in one story she fights Mustakawi, inanother story Rarasati. Such episodes are confinedto the semi-refined (ladak) females. The refined(lungguh) females, by contrast, abstain from battleand are ideologically more valued by virtue of theirnon-violent nature.

Perang gagah (strong battle) is the term when a

strong monggawa warrior fights another warrior, anogre minister, or an ogre king. Examples would beGatotkaca (monggawa lungguh) either fighting hisdemonic uncle Brajamusti (danawa patih) or, as achild, slaying the serpent King Naga Persona(danawa raja).

Perang Pancalan is the term used to refer to abattle between a knight (lungguh or ladak) and astrong figure (monggawa or danawa). For examplethe fight between the Pandawa hero Arjuna(lungguh) and the ogre king Niwata Kawaca(danawa raja) for the hand of the heavenly goddessSupraba would fall into this group as would thefight of Abimanyu (a lungguh young son of Arjuna)with the proud warrior (monggawa danggah)Jayadrata who slays him. Semi-refined knightsmight be Karna in his successful battle against thePandawa hero Gatotkaca (monggawa lungguh) orSomantri, when minister of Raja Arjuna Sasra Bahu,against the demonic king, Rawana (denawa raja).