· Web viewBad for Business? The Effect of Hooliganism on English Professional Football Clubs R....

Transcript of · Web viewBad for Business? The Effect of Hooliganism on English Professional Football Clubs R....

Bad for Business?

The Effect of Hooliganism on

English Professional Football Clubs

R. Todd Jewell1

Rob Simmons2

Stefan Szymanski3

March 2014

Abstract

Football hooliganism, defined as episodes of crowd trouble inside and outside football stadiums on match days, is commonly perceived to have adverse effects on the sport. We are especially interested in the effects of football-related fan violence on a club’s potential for generating revenues. In this paper we measure hooliganism by arrests for football-related offenses. We analyze two distinct periods in the history of hooliganism in the English Football League: an early period during which hooliganism was a fundamental social problem (seasons from 1984/85 to 1994/95), and a more recent period in which hooliganism has been less prevalent (2001/02 to 2009/10). In the early period we find evidence of an adverse effect of arrests on football club revenues for English League clubs. This effect disappears in the more recent period showing that hooliganism, while still present but at lower levels, no longer has adverse effects on club finances. Our results support a hypothesis that recent “gentrification” has reduced hooliganism and thereby has had a positive influence on revenue generation.

1 Department of Economics, PO Box 311457, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203-1457. Phone: 940.565.3337, Fax: 940.565.4426, E-Mail: [email protected] The Management School, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YX, United Kingdom, Phone: 44-1524-594234, FAX: 44-1524-594244, E-mail: [email protected] School of Kinesiology, University of Michigan, 3118 Observatory Lodge, 1402 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2013, Phone: 734 647 0950, Fax: 734 647 2808, [email protected]

1

Introduction

Disorder at football stadiums – hooliganism, violence in the crowd, and other forms of

crowd disturbance – is sometimes called “the English disease.” While crowd violence at sports

arenas has a long history (see Dunning, Murphy and Williams (1988)) and has been documented

across the world (see Dunning, 2000), it has been synonymous with English football since it first

became an issue of national concern in the 1960s, and an international concern by the 1980s,

culminating in the five-year ban of English clubs from European football competition after the

Heysel tragedy of 1986. There is a large literature on hooliganism in sociology, criminology, and

anthropology, examining the roots of football violence and the motives of the actors. A smaller

literature relates hooliganism to match day attendances. As far as we know, there has been no

research on the impact of hooliganism at football matches on the sporting performance and

finances of football clubs.4

The lack of research on the effects of crowd violence on the sporting and business side of

the game is surprising, given that hooliganism has been blamed for declining attendance at

English football from the 1960s to the mid-1980s.5 Moreover, given the extensive economic

literature on favoritism under social pressure (e.g., Garicano et al. (2005)) influencing the

outcome of competitive sports, one might imagine that fan violence could be a very potent form

of social pressure. One explanation for this gap may be the limited research by economists on

crowd disturbances. A second might be the paucity of data on crowd violence. This paper uses

one of the few data sources available to examine the relationship between crowd disorder and

team success, both on and off the pitch. Since the 1984/85 season, the number of arrests by the

4 Throughout this study, we refer to the sport of association football as “football,” as this is the accepted term in the UK. In some countries, notably the US, football refers to gridiron football and the National Football League.5 As early as 1968, The Harrington Report warned that hooliganism was affecting attendance (chapter 11, p. 52), and recent works such as Dobson and Goddard (2011, p. 156) confirm this belief.

2

police at football stadiums in England has been published annually for four divisions of

professional football in England. Excluding data for the 1995/96 to the 2000/01 seasons, the

arrest data are disaggregated at the club level, but club-level data on arrests are otherwise

available up to the 2009/10 season. Luckily, the gap in the club-level data occurs at a natural

breakpoint. Following the Hillsborough disaster of 1989 and the Taylor Report of 1990, English

football stadiums were radically overhauled. The creation of the Premier League in 1992 led to a

dramatic increase in club revenues especially among the larger clubs, providing significant

resources for stadium investment. As a result clubs were able to invest in significantly more

powerful systems (most notably CCTV systems) to identify those engaged in disorderly

behavior, while changes in the law made it easier to exclude known perpetrators from stadiums.6

These changes were being adopted just before the break in our data starts and were fully in place

by the time the break ends.

In this paper, we use the club-level arrest data, as well as club-level revenue data, to

address two questions. First, how were arrests related to league performance over the season?

Second, how were club revenues affected by arrests? We find that in the early period (1984/85 –

1994/95) crowd violence, as measured by the rate of football-related arrests per fan, was a

decreasing function of the on-field success of the team, while club revenues were a decreasing

function of the arrest rate. In the later period (2001/02 – 2009/10) we continue to find evidence

of an inverse relationship between arrest rates and on-field success but find no relationship

between and revenues and rate of fan violence as measured by arrests per game.

We take the estimated negative relationship between arrests and club success as evidence

that disturbances at football matches are in part a reflection of fans’ disappointment with the

poor performance of the team. The fact that this relationship seemed to spill over into reduced 6 Priks (forthcoming) offers evidence from Swedish micro data to show that the introduction of CCTV can causally lead to a reduction in disorderly behavior.

3

revenues of the club in the early period suggests that disturbances deterred fans from attending

games or otherwise contributing financially to their clubs. In the recent period the frequency of

arrests has fallen significantly which, combined with significantly tighter security and

surveillance, suggests that crowd disturbances are no longer a significant deterrent to attendance

at games, even if such disturbances have not entirely disappeared. This account seems to be

borne out in the literature on the decline of hooliganism.

Care must be taken in linking arrests to hooliganism, since policing methods can also

affect the number of arrests. Nonetheless, it is highly likely that the two are correlated. Based on

an assumed correlation, our data and results tell a very plausible story. The earlier era was the

high point of hooligan concerns, and a period in which it seemed that English football as a whole

was in danger of collapse. The later period is often remarked upon for its rapidly rising ticket

prices and “gentrification” of the game, as well as a perceptible decline in the “hooligan

problem.”7

Hooliganism and Crowd Control in English Football

The study of hooliganism has been almost exclusively the preserve of sociologists.

Reviews of the historical record show that violent acts by football fans date back to the 19th

century (e.g., Dunning, Murphy, and Williams (1988)), although football violence was not

recognized as a social problem in England until the start of the 1960s. Harrington (1968)

produced the first government report on the subject and identified several dimensions of

7 By “gentrification” we mean soccer crowds that are composed of older fans with higher incomes. This may reflect a change in the social composition of the fans (a larger share of white-collar, professional, technical or managerial employees) or alternatively just an aging of the fan base, and hence a lower propensity to rowdy behavior. Interestingly, one of the earliest demand studies in English soccer (Bird (1982)) referred to the notion of gentrification, which he associated with the idea of introducing all-seater stadiums in order to restrain hooliganism. All-seater stadiums were in the end mandated by the government in the aftermath of the 1989 Hillsborough Disaster. One interpretation of the notion of gentrification is the conversion of fans with a sense of ownership of and participation in their club into mere customers, albeit wealthy fans who pay high prices (see e.g. King (2002)).

4

hooliganism: rowdyism; horseplay and threatening behavior; foul support (e.g., throwing

missiles); footballmania (collective misbehavior by mobs of 50 or so youths on the streets);

football riots (fights between rival fans); individual reactions (e.g., assaulting policemen);

vandalism; and physical injuries caused by fists, razors, knives, etc.

In this paper, we use data on arrests at football stadiums as an indicator of the extent of

disturbances. A 1978 report on public disorder at sporting events identified four principal laws

under which the police could intervene – the Public Order Act of 1936 (threatening or abusive

behavior in a public place), the Police Act of 1964 (obstructing a constable in the execution of

his duty), the Prevention of Crime Act of 1953 (having an offensive weapon in a public place

without reasonable excuse), and the Criminal Law Act of 1977 (which increased the penalties for

assault and resisting arrest). Further legislation followed (i) the Heysel Stadium disaster in 1985,

in which 39 Juventus fans died when a wall collapsed as they tried to escape from an assault led

from the section of the stadium reserved for Liverpool fans, (ii) the Bradford City disaster in

which 56 fans died in a fire that started in the main stand (not hooligan-related), and (iii) the

Hillsborough disaster of 1989, in which 96 fans were crushed to death (also not hooligan-

related).

Part of the legislation aimed at improving conditions inside stadiums, but reducing

hooliganism was also the focus. Thus, the Sporting Events (control of alcohol) Act (1985) made

it an offence to consume alcohol at football stadiums and on trains or buses going to stadiums.8

The Football Spectators Act (1989) allowed the courts to ban fans from a stadium and to require

an individual to surrender his passport if suspected of being a hooligan likely to travel to a game

being played overseas. The Football Offences Act (1991) made it illegal, inter alia, for fans to

enter the playing area, to engage in racist chanting, or to throw missiles at a football match. 8 This legislation is specific to the United Kingdom; such restrictions on sale and consumption of alcohol inside football stadia are absent in the rest of Europe.

5

These laws were further strengthened by the Football (Offences and Disorder) Act (1999) and

the Football (Disorder) Act (2000). Football clubs and the police have focused on prevention,

primarily through the segregation of fans, increased surveillance, and heavy policing. The

number of arrests at football matches suggests that they have not been wholly successful.

However, a by-product of legislation has been increasingly accurate quantification of hooligan-

related activities, at least insofar as they are measured by arrests.

Sociological studies have generally tried to place hooliganism in the context of broader

social problems.9 One of the earliest approaches by Taylor (1971) viewed hooliganism as a

response by working class fans to the appropriation of football clubs by owners and directors

intent on commercializing the game. In this explicitly Marxist framework, violence was a

response to alienation from control of the club, which traditionally rested with the fans. Not

surprisingly, this approach was widely rejected since (a) it was not clear that a golden age of fan

ownership ever existed, and (b) fan violence seemed to be largely aimed at other fans, not the

owners. Others, such as Marsh et al. (1978), tried to derive a more anthropological view. They

argued that much of what happened at football matches, while appearing disorderly to outsiders,

actually represented a ritual that was highly codified and involved much less violence than

commonly thought.

By the 1980s, the evidence made it impossible to believe that real violence was not

involved, but the ritualistic aspect was taken up by the so-called Leicester School (e.g., Dunning

et al., 1988), which argued that hooliganism was a form of “aggressive masculinity.” Elements of

codification and ritual helped to establish identities and a certain kind of social order, including a

means to “promotion” for those engaged in hooliganism. This model has also come in for

significant criticism because hooliganism is clearly not restricted to the working class and 9 An excellent survey of this literature is provided by Taylor (2008, pp. 309-319).

6

because of the school’s insistence that hooliganism was an ever-present phenomenon, while most

researchers have been prepared to accept that there was a clear shift in the 1960s. More

pragmatic accounts have tended to focus on issues such as the decline of authority, greater

individual freedom, and, to some extent, adverse economic conditions.

There can be little doubt that the poor quality of stadiums helped to engender a negative

attitude, and antagonism between the police and fans was a two-way street. The tragedy at

Hillsborough in 1989, where 96 fans were crushed to death while the police stood by and did

little or nothing, perfectly illustrates the breakdown in social relationships. While subsequent

inquiries have demonstrated conclusively that neither hooliganism nor excessive consumption of

alcohol (often associated with crowd violence) contributed in any way to the tragedy, senior

police officials tried to put the blame on rowdy fans.10

More generally, some scholars have argued that police tactics can affect the extent of

hooliganism; for example, it has been argued that an aggressive approach by the police can

provoke fans into acts of hooliganism (Pearson, 1999). The effects of more aggressive policing

on hooliganism are a priori ambiguous. Poutvaara and Priks (2009) present Swedish evidence to

show that selective targeting of hooligan groups by police backed up by police intelligence can

reduce hooligan activity. On the other hand, indiscriminate police tactics such as use of teargas

to disperse unruly fans or random prison sentences for convicted fans could actually raise

hooligan activity by reinforcing the idea that the relationship between fans and police is

necessarily antagonistic.

10 The Hillsborough disaster is in many ways the defining event of modern English football. It has taken many years to establish that some police authorities badly mismanaged the response to the disaster and then attempted to cover up the evidence. Ultimately, however, the tragedy has resulted in a significant re-evaluation of the relationship between fans and the police. The events and subsequent response to Hillsborough has been exhaustively documented on the website of the Independent Panel hillsborough.independent.gov.uk. Tsoukala (2009) assesses the relationship between policing and hooliganism across Europe from a criminologist’s perspective.

7

An interesting aspect of the Harrington Report was a survey of about 2,000 readers of

The Sun, a tabloid newspaper, 90% of whom claimed that hooliganism was an increasing

problem. Two-thirds of respondents believed that “supporting a losing team” was a contributory

factor, making it the most commonly cited reason (ahead of “needle match or league match”,

“foreign influences”, “overcrowding on terraces”, “poor ground facilities”, or “supporting a

winning team”). Subsequent research has almost completely neglected this explanation. The

reasons for this neglect are not entirely clear. Since there will always be losers, perhaps

researchers feel uncomfortable that the explanation amounts to something that cannot be

avoided. Perhaps anger at defeat is too simple an explanation, and researchers are more

concerned with the deeper question of why defeat triggers a violent reaction in some but not

others. Alternatively, hooliganism as a negative response to a losing team might be regarded as

an untestable proposition. Certainly, arrests data were not published until the mid-1980s, and it

was only in the mid-1990s, when the problem was already coming under control, that a time

series that was large enough for econometric testing had been generated.11

As far as the adverse effects on clubs are concerned, there also seems to have been little

interest in identifying winners and losers. One recent study (Rookwood and Pearson, 2012) did

point out that most fans do not see hooligans as an entirely negative phenomenon and identified

benefits that non-hooligans might derive from the presence of hooligans ̶ distraction, protection,

and reputation. No one associated with a club could openly claim that they had benefited from

hooliganism, even though this view is consistent with the well-established literature on

favoritism under social pressure (Garicano et al, 2005).12 11 The North American literature on sports-related offences is sparse. Rees and Schnepel (2009) argue that arrest rates in college, gridiron-football towns rise when the home team suffers an unexpected loss.12 Hooliganism could be one factor that enhances home advantage. Referees might offer greater decision-making bias in favor of home teams if they are successfully intimidated by potentially violent home fans. In Italy, stadiums that are scenes of severe outbreaks of hooliganism (including racist behavior) are closed to all fans for a number of subsequent games. Pettersson-Lidbom and Priks (2010) present evidence on Italian soccer to show that referee bias was reduced when home teams were forced to play behind closed doors (i.e., without fans present).

8

We hypothesize that fan violence will be associated with two effects. One effect runs

between hooliganism and team performance. In this paper we investigate the possibility that

hooliganism is a response to poor team performance, although one might also consider the

possibility that hooliganism might have a positive effect on team performance by intimidating

the referee and opposing team. In the longer term, however, if a team comes to be associated

with hooliganism it may lose support, since non-violent fans may fear for their safety, and its

costs will increase since the police will insist on a heavier presence. In the English system each

club is required to pay for the policing at their own stadium. So far as we know, this is the first

study to analyze the relationship between hooliganism and the financial performance of football

clubs. At the very least, we know that clubs have to pay for the policing of their own games, and

so the greater the perceived hooligan problem the greater the cost. Using a database of financial

accounts we are able to examine the effects in detail.

Methodology and Data

Our approach is to model both violent behavior (measured by arrests) and revenues

simultaneously.13 Revenue is assumed to be a function of on-pitch performance (P) and fan

violence (V). Club revenue is also influenced by market potential (M).

(1) Revenueit = R(Pit, Vit, Mit)

This relationship is stated in equation (1), where i and t index clubs and seasons, respectively.

We hypothesize that ∂R/∂P > 0 (better on the pitch performance increases revenues) and ∂R/∂V <

13 No doubt some will consider it controversial to identify arrests with hooliganism, given the well-known antagonism between the police and some fans. We expect that our data are subject to measurement error. Biases are possible in either direction. Arrests could overstate the extent of hooliganism to the extent that police indiscriminately arrest fans as part of an overzealous approach, but arrests involve considerable police effort in terms of processing charges. Police then have an incentive to arrest fans only if they really feel these fans have committed offenses. Then hooliganism may be understated by the number of arrests. In the absence of detailed evidence, we assume that these biases are offsetting.

9

0 (greater violence reduces revenues). The direction of the effects of market size on club

revenues will vary depending on the empirical measures employed.

We assume that fan violence is influenced by a club’s on the-field performance.

Specifically, we hypothesize that fans are less likely to engage in violent behavior at any given

football match if the team is performing better:14

(2) Violenceit = V(Pit) , where ∂V/∂P < 0

The financial accounts of English football clubs were obtained from Companies House, a

UK government agency.15 Revenueit is measured as total revenues for each club i in each season

t, valued in real millions of UK pounds. Since both revenues and wage bills have risen at a much

faster rate than general inflation, use of a consumer price index to deflate revenues is

inappropriate. We construct a football price index based on wage inflation. We take a team wage

bill series compiled from club balance sheets. The wage bills are separated by division and a

division-varying wage index is compiled with a base season of 2009/10. This enables the wage

index to reflect the greater rate of increase in wages and revenues in the top division, now the

Premier League, than in lower divisions. The cost of achieving a given rank in the league varies

with the wage costs of the players hired. But this wage cost is rising much faster in the top

division, most recently through the high growth rate of broadcast rights values, in turn

transmitted directly into team payrolls. If we were to deflate lower division revenues by an

average wage cost across all divisions, the real incomes of lower-division teams would appear

14 This might be a direct consequence of disappointment at defeat, but it might also be a signal of dissatisfaction with club management, especially the Chairman and Board of Directors, and thus a form of lobbying for reform. 15 Financial information for the last decade or so at least can downloaded for a small fee from this website http://wck2.companieshouse.gov.uk/c3e6ddbd60434f4088c2fcfcf1db83ac/wcframe?name=accessCompanyInfo. Data from 1974 to around 2000 can be obtained by request on a CD-rom. Prior to 1974, only paper records exist.

10

lower than they really are. Hence, we deflate Revenue by our division wage cost index to

generate revenue in real English football terms.16

Our measure of hooliganism is in terms of football-related arrests. We rely on arrest data

from two distinct sources and eras. First, we have data by season and by club on the total number

of arrests in and around football stadiums in England and Wales over the seasons 1984/85 to

1994/95.17 These data were supplied by the Association of Chief Police Officers, collated by the

Sir Norman Chester Centre for Football Research at the University of Leicester and published in

the Digest of Football Statistics. Our second data set covers a later period, 2001/02 to 2009/10

and comprises United Kingdom Home Office arrests data. Arrest data for seasons between

1995/96 and 2000/01 are available from the Home Office, but these data are available at the

division level but not by club.

An important difference between the data in our early and late periods is that the former

refers to total arrests at each stadium, while the latter refers to total arrests of supporters of each

team, broken down by whether they were arrested at the home games (i.e., at the home stadium)

or at away games. Thus for the later period, we are unable to identify exactly how many fans

were arrested at each stadium, only the arrests of home fans. Hooliganism, by creating the

impression that attending the game is not safe, tends to reduce attendance. For each club the

problem is likely to be greater the higher the incidence of hooliganism at the home stadium and

16 We could have left revenues in nominal terms, letting year dummies take care of inflation, or we could have deflated revenues by CPI letting year dummies control for ‘excess’ inflation. Our results are robust to these alternative treatments of revenue.17 “Arrests” covers all arrests defined under schedule 1 of the Football Spectators Act 1989 and includes soccer-specific offences, such as violent behavior, throwing missiles, pitch encroachment and a wide range of generic criminal offences committed in connection with a soccer match. The offences need not be committed immediately before, during or after the match; the Home Office states that a football-related arrest can occur “at any place within a period of 24 hours either side of a match.” This flexibility is designed to capture alcohol-related offences that might occur sometime before or after matches are actually played. There are 39 observations (16 in the early period and 23 in the later period) with number of arrests equal to zero. We set those observations to one arrest in order to compute the log arrest rate.

11

so will adversely affect revenues by comparison with rival teams.18 The relationship between

hooliganism and league performance is more complex. In this paper, we assume that causality

runs from performance to hooliganism and not vice versa. In particular, we hypothesize that poor

performance on the pitch will lead to fan violence. Thus the early-period variable total arrests at

the stadium is probably best suited to measuring the revenue effects, while the later-period

variable arrests of home fans at home games is probably best suited to measuring the impact of

on-the-pitch performance on hooliganism. In any case, for the later period we also experiment

with total arrests of home fans (i.e., at both home and away games).

Our data cover the 92 clubs participating in the top four divisions of English professional

football.19 Until 1992, the clubs in these four divisions constituted the Football League. After

1992, the top division broke away to form the Premier League (to gain control of all broadcast

money generated in this division while retaining the promotion and relegation relationship with

the lower divisions), and so the Football League constituted only the second, third and fourth

tiers of competition. Notwithstanding the issues of financial control, the four divisions represent

a single sporting structure in both our periods, which we will refer to generically as Professional

English Football (PEF). Because we have annual data, we normalize the total number of arrests

per season by the aggregate number of fans attending in that season (i.e., arrests per 1,000 fans

per game). In this way, we control for differences in the size of the fan base and the potential

population of offenders. Average attendance is approximately 30,000 per game in the top

division and about 4,000 in the fourth tier. Thus, in general, the greatest number of arrests occurs

at clubs with the highest average attendance, but a higher arrest rate per 1,000 fans likely

signifies a greater problem for the club and should have a larger influence on club revenues.

18 Gate revenue sharing for league games was abolished in the 1983/84 season.19 The divisions are connected through the system of promotion and relegation, whereby the weakest teams in a given division, measured by their win/tie/loss records, are automatically sent to play in the next division down in the following season, to be replaced by the strongest teams (again measured by win/tie/loss record) from that division.

12

Reconsider equations (1) and (2) in the presence of unobservable variables that influence

both club revenue and the amount of fan violence. For instance, assume there exists an

unobservable measure of “passion for your club,” which increases both revenue and arrests.

Specifically, teams with more “passionate” fans tend to have higher revenues, ceteris paribus, but

these teams also tend to see fan violence as “passion” that spills over into hooliganism. The

existence of such unobservable measures in systems of equations leads to an estimation bias,

termed “unobserved heterogeneity bias” or “endogeneity bias.” In the case of unobserved

heterogeneity in fan passion, OLS estimation of equation (1) would result in a positive bias on

the coefficient on V in the revenue equation. Since we hypothesize that ∂R/∂V is negative,

endogeneity bias will lead the coefficient on V to be biased toward zero.

We utilize 2SLS estimation to control for the potential endogeneity of fan violence.

Specifically, we estimate a first-stage regression of equation (2) using the relevant measure of

arrests for the period in question (i.e., Total Arrest Rate or Home Arrest Rate) and create fitted

values for fan violence, which are used as instruments for fan violence in a second-stage

regression of equation (1). 2SLS requires at least one exclusion restriction to identify fan

violence separately from club revenue. We use lagged values of the relevant arrest rate as an

exclusion restriction, as past values of arrests are indicative of a tendency toward or against

current rates of fan violence.20 Note that usage of the lagged arrest rate means that we must drop

the earliest year of data in each period for the estimation. Thus, our estimation samples cover the

seasons 1985/86 to 1994/95 and 2002/03 to 2009/10.

20 Using a single exclusion restriction implies that the fan violence equation is exactly identified. We investigated additional exclusion restrictions, including measures of policing intensity, without finding any other suitable instruments. The major drawback to our use of a single exclusion restriction is that there is no way to statistically test for the appropriateness and strength of the exclusion restriction in exactly-identified equation systems. Specifically, the instrument needs to be uncorrelated with the error term from the second stage regression. Without multiple restrictions, this cannot be directly tested.

13

On-pitch performance is measured as the negative of season-ending position for club i in

season t and for each division n (Rankitn) and, defined this way, is expected to be positively

related to team revenues (Szymanski and Kuypers, 1999; Szymanski and Smith, 1997). We also

test for a non-linear relationship between performance and revenues by employing the negative

log of ending position as well as position dummies. In general, the implications of the results

change little with difference measures of club performance. Past performance may influence club

revenues, especially if the club in question was relegated or promoted at the end of the previous

season. The variables Lag Promotedit and Lag Relegatedit are indicator variables that equal one if

a club was promoted or relegated, respectively, in the previous season. The coefficients on Lag

Promotedit and Lag Relegatedit cannot be signed a priori.

Market potential is measured with several variables. First, we include fixed effects

dummies for club, division, and season. Adding fixed effects may also partially control for

differences in policing practices by division, club, and season.21 Second, we expect that clubs

with all-seater stadiums generate greater revenues. Allseaterit equals one if the club played in

such a stadium in season t. Traditionally, football stadiums included large sections without seats

where standing was the only option (“terraces”). Following the Hillsborough disaster, terraces

have been phased out, especially at the higher division clubs. Third, we include indicators of the

number of derby games in each season for each club. Derby1itn equals one if club i has one

traditional rival in division n during season t. Derby2itn if a club plays more than one traditional

rival in league play in season t.22 The coefficients on the derby indicators are expected to be

positive, since rivalry games generally lead to greater attendance demand and should lead to

greater revenues.

21 We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting this.22 What makes for genuine “derby” is a matter of judgment, but is usually well understood by the fans. Our definition is based on the following webpage: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Local_derbies_in_the_United_Kingdom.

14

In the next section, we present results of IV regressions of equation (1) of the following

general form, where , , and are vectors of fixed effects for club, season, and division

respectively, and it is a white noise error term.

(3) Revenueit = 0 + 1*Rankitn + 2*Predicted Log Total/Home Arrest Rateit

+ 3*Lag Promotedit + 4*Lag Relegatedit + 5*Derby1itn + 6*Derby2itn

+ 7*Allseaterit + *Clubi + *Seasont + *Divisionn + it

Predicted Log Total/Home Arrest Rateit is the predicted value of log of the relevant arrest rate per

1,000 fans per game computed based on a first-stage regression of the log of the arrest rate on all

the exogenous variables in the system and the log arrests per 1,000 fans per game lagged one season

(Log Lag Total/Home Arrests).23

Results and Discussion

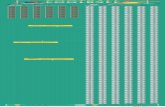

The overall trend in our dependent variable is illustrated in Figure One, which shows the

average Total Arrest Rate per 1,000 fans attending league games in each of the four tiers of PEF

from 1984/85 to 2007/08. Figure One shows that hooliganism was in fact in decline from the

earliest point in our data, and in the recent era has remained relatively low. This reflects both a

decline in the number of arrests – total league game arrests averaged 5,141 per year in our first

period, and only 2,980 in the later period- and an increase in attendance – from 19.3 million per

year in the first period to 28.3 million per year in the second period.

[Insert Figure One about here]

23 It could be argued that financial insolvency might influence both revenues and arrests. We were unable to investigate this possibility given time constraints. One reason that club insolvency might not affect revenues or arrests is the presence of a soft budget constraint (Andreff, 2014). Insolvent football clubs are not usually wound up, so fans do not necessarily care about bad financial performances of their clubs so long as their teams can continue to play (i.e., fulfill their fixtures). A similar argument applies to the debt-assets ratio. We expect that when teams underperform in the league then their revenues fall relative to spending. The debt-assets ratio rises and if this is not controlled then insolvency is the result. In that sense, insolvency is a consequence and not a driver of low revenues. For details of individual insolvency cases see Beech et al. (2008). Szymanski (2012) articulates a model of debt and insolvency in English soccer.

15

[Insert Table One about here]

Table One contains summary statistics for our two estimation samples, 1985/86 to 1994/95

and 2002/03 to 2009/10. Recall that the first year for each period is lost due to taking a one-year lag

in the arrest rate. In the first period, we use total arrests at league games per 1,000 fans per game

(Total Arrest Rate). In the second period, we use two measures: the number of arrests of home fans

at all home games per 1,000 fans per game (Home Arrest Rate), and total arrests of club fans at all

home and away games per 1,000 fans per game (Total Arrest Rate). Recall that the arrest data from

the earlier period is by club and the arrest data in the later period are by stadium. Further, note that

the number of arrests (home and away) in the later period are summed for all games, while arrests

are only for league games in the early period. In the early period, the arrest rate is computed using

the number of league games and the average attendance at league matches. In the later period, the

arrest rates are computed using the number of all games played (or ½ the total number of games for

Home Arrest Rate) and the average attendance at league matches. 24 Thus, Total Arrest Rate is

measured differently in the two periods and, therefore, is not directly comparable.

Era of “The English Disease”: 1984/85 to 1994/95

Research has highlighted the significance of hooliganism as a social problem in 1980s

Britain, so much so that hooliganism has been termed the “English Disease.”25 Table Two

presents estimates of the first-stage arrest equation using data from this period in the history of

English football measuring Rank linearly, in logs, and by quartile within each division (upper,

24 League games comprise 85% of all games played in the later period, so we do not expect that this will result in biased estimates.25 “The English disease” is a term that was used by several journalists to characterize crowd trouble triggered by English soccer hooliganism both at home and abroad. The reason for calling it the “English disease” rather than the “British disease” appears to be the notoriety of fans of the English national team when travelling abroad, who have often been involved with violent incidents, as compared to the fans of the Scottish national team, who, while also consuming excessive quantities of alcohol, have been generally peaceable. However, hooliganism was as much a problem in Scotland in the period under consideration as it was in England, and was often associated with sectarian conflict between “protestant” Rangers fans and “catholic” Celtic fans. Our data concerns English league soccer, which is organized separately from Scottish league soccer.

16

middle, lower middle and low with high as the excluded category). As in all other estimates

reported in this paper, team, season, and division fixed effects are included in both the first and

second-stage estimates. Additionally, standard errors are corrected for clustering on club. All

three specifications indicate that lower rank in a division is associated with higher arrest rates.

Thus, it appears that in the era when hooliganism was at its worst, football-related arrests can be

linked to poor on-field team performance. In that sense we find that hooliganism was a response

to the (low) quality of play of the home team in the early period of analysis

Table Two also shows that teams that are promoted into a higher division tend to bring

with them higher arrest rates. There is a tendency for promoted teams to struggle in the new

division and the increase in arrest rates for promoted teams may reflect low expectations on the

part of fans, who then substitute misbehavior for viewing their teams’ (expected) weak

performances in a higher division. Alternatively, it could be that promoted teams are “importing”

higher rates of fan violence from the lower divisions. The division fixed effects show that the

level of fan violence in lower divisions is not significantly different from that in the top division.

That is, there does not appear to be a greater tendency toward fan violence in the lower divisions

of English football, at least in this earlier period, illustrating the pervasive impact of hooliganism

on all levels of the professional game. In addition, teams that had been relegated in the previous

season are not associated with higher arrest rates, controlling for end-of-season rank.

[Insert Table Two about here]

We also do not find evidence that having local rivalries (Derby1 and Derby2) is

associated with higher arrest rates than at those clubs that do not have local rivals. This is

surprising since it seems plausible that particular local rivalries act as a focal point for those

interested in engaging in hooliganism or provoke more extreme reactions for those fans who

might normally be more quiescent. It may be that where fans consider their team to have several

17

minor local rivals (e.g., around London or Manchester where distances between teams are small),

fan agitation is likely to be spread more thinly across a greater number of games, with more or

less the same impact on arrests as when teams have a few intense rivalries.

As expected, Lag Total Arrest Rate has a positive, significant coefficient in the arrests

equation, indicating that there is a persistence effect to fan violence in our earlier sample period.

The coefficient size suggests that this persistence effect is not large; a one percent increase in the

lagged arrest rate is predicted to increase the current arrest rate by less than 0.2 percent. The high

level of significance suggests that the variable is a suitable instrument for the arrest rate in the

revenue equation, although there is no way to test the validity of a single instrument. Some

indirect support for the validity of the instrument lies in the result that when we run an OLS

reduced-form model of revenues in the early period, we find that Lag Total Arrest Rate has an

insignificant coefficient in the revenue equation.

Results from estimates of the revenue equation for the early period are shown in Table

Three. Models with Log Real Revenue are preferred to those with real revenue measured linearly

(not reported) due to better goodness of fit as measured by R2. As expected, a higher rank in a

division is associated with increased real revenue. Teams that were relegated in the preceding

season bring with them greater revenues from the higher division as compared to incumbent

teams. Having two or more local rivals (Derby2) also raises revenues as expected.

[Insert Table Three about here]

In all three of these specifications, the coefficient of our instrument, Predicted Log Total

Arrest Rate, is negative and significant at the 10% level or better. The negative relationship

between arrests and revenues is robust across several functional forms. The elasticity of revenue

with respect to the arrest rate is consistently estimated between -0.16 and -0.18, which appears to

be a plausible value. The endogeneity tests reject the null hypothesis of exogeneity at the 5%

18

level for columns 1 and 3, and slightly above this level for the specification in column (2).

Hence, in the 1980s and 1990s there is evidence suggesting that increased hooliganism had an

adverse effect on teams’ financial performances through real revenues. Although this result

probably won’t surprise many scholars, ours is the first study that shows this result. The

interesting question that follows is whether these adverse effects persist in a more recent period,

after the Premier League was formed and club revenues soared.26

Era of Gentrification: 2001/02 to 2009/10

The top division in PEF broke away from the remaining three division of the Football

League to form the English Premier League (EPL) in 1992. This was in large part motivated by

the desire of the biggest clubs to negotiate and retain broadcast rights income independently of

the clubs in the lower divisions. The mid to late 1990s saw a huge increase in revenues for

English football, with the lion’s share accruing to EPL clubs. However, revenues for all PEF

clubs increase after the mid-1990s, owing much to the gentrification of the sport.

Table Four presents 2SLS and first-stage results of the arrest rate and revenue equations

for the later estimation period (2002/03 to 2009/10, where one season’s data is lost due to lag

construction). Here, the arrest rate is based on arrests of home team fans at home team games.

We report two different specifications, one using the negative log of league rank, the other

identifying league rank by quartile within division. The main findings from this Table Four can

be summed up as the following: the inverse relationship between league rank and the arrest rate

found in the earlier period holds for the arrest rate for home fans in the more recent period; also,

contrary to our findings for the earlier period there is no evidence to suggest that the home arrest

rate significantly affect revenues in the later period.

26 We jointly test the significance of the performance measures in the revenue equations reported in Tables 3, 4, and 5, finding that these measures are jointly significant at better than the 1% level in all specifications. Likewise, the measures for market potential are jointly significant in the revenue equations of Tables 3, 4, and 5. These results are available from the authors upon request.

19

[Insert Table Four about here]

Furthermore, the lagged arrest rate does not affect the current arrest rate in the more

recent era, implying that the former is not a valid instrument. It is no surprise that the

endogeneity tests in the revenue model in Table Four comprehensively fail to reject the null

hypothesis of exogeneity. Moreover, the coefficient of Predicted Log Arrests is clearly not

statistically significant in the revenue equation. Apart from this major difference, the results in

Table 4 for both revenues and arrests bear a strong similarity to those in Tables 2 and 3,

suggesting that the structure of relationships has remained relatively stable while hooliganism

has subsided and match day revenues were overtaken by broadcast revenues as the primary

source of club income.

[Insert Table Five about here]

For completeness, we also considered the impact of total arrests of team supporters (at

both home and away games) in Table Five. We did not expect to find any significant relationship

between arrests and revenues in this case, since the arrests of a team’s fans at away games is

more likely to be a financial problem for the host club than the club that the fans support. This

hypothesis is confirmed by Table Five, which also shows that there is no significant relationship

between arrests and on the pitch performance of the team. Note that in this specification there is

not even a significant relationship between revenues and league rank. But, in Tables Four and Five

show something very interesting that was not found in the earlier sample; it appears that teams in PEF

divisions below the top tier have higher arrest rates than the top tier, suggesting that the “gentrification”

of English football is concentrated in the top tier. In the appendix, we report OLS regressions for revenues

using arrests rather than its instrument. The results here resemble those of existing revenue models (e.g.

Szymanski and Smith (1997)), while the arrests variable is insignificant.

20

Conclusion

Football hooliganism, defined as episodes of crowd trouble inside and outside football

stadiums on match days, is commonly perceived to have adverse effects on the sport. However,

hooliganism might also have beneficial effects for the home team, if it generates social pressure

on players and officials through intimidation and so increases the probability of home team

winning. Alternatively, fans might turn to violence when their team performs poorly, leading to

an inverse correlation between arrests and team performance. Surprisingly, there appears to be

no research estimating the size of these effects (good or bad).

Identifying these effects empirically is difficult. In this paper, we measure hooliganism

by arrests for football-related offenses. Using a unique database we find that in the period

1984/85-1994/95 arrest rates were negatively related to team performance and negatively related

to football club revenues in England and Wales. In the period 2001/02-2009/10, we find that

arrest rates are negatively related to team performance, but we can find no relationship between

arrest rates and football club revenues in England and Wales in either 2SLS or OLS models for

our later period. We conclude that arrests are orthogonal to club revenues from 2001/02 onwards.

The decline in football hooliganism since the 1980s is consistent with an economic model

of crime (Becker, 1964; Ehrlich, 1973; Fajnzylber et al., 2002). Although hooliganism is similar

to violent crime in that it can often be instinctive or pathological, it is still conducive to economic

analysis. In particular, the opportunity costs of committing hooligan offences have risen through

increased detection probability (CCTV; improved stewarding and policing) and greater

sentencing costs (banning orders). Also, it is likely that tastes for hooligan activity (which we

associate with arrests) have shifted with a more diverse (‘gentrified’) and pacific crowd inside

the typical English football stadium. While we lack the detailed data needed to disentangle these

21

effects, we have shown that such hooligan activity as remains in England and Wales is no longer

detrimental to club finances.

22

References

Andreff, W. (2014). Building blocks for a disequilibrium model of a European sports league, International Journal of Sport Finance, 9: 20-38.

Becker, G. (1968) Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy. 76: 175-209.

Beech, J., Horsman, S. & Magraw, J. (2008) The circumstances in which English football clubs become insolvent, Coventry University Centre for International Business of Sport Discussion Paper 4.

Bird, P. (1982) The Demand for League Football. Applied Economics, 14, 637-49

Dobson S. and Goddard J. (2011) The Economics of Football (2e). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Dunning, E (2000) Towards a sociological understanding of football hooliganism as a world phenomenon. European Journal of Criminal Policy and Research, 8,141-162.

Dunning, E., Murphy P. & Williams J (1988) The Roots of Football Hooliganism: a Historical and Sociological Study. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Ehrlich, I. (1973). Participation in illegal activities: a theoretical and empirical investigation. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 551-565.

Fajnzylber, P., Lederman, P. and Loayza, N. (2002). What determines violent crime? European Economic Review, 46, 1323-1357.

Garicano L., Palacios-Huerta I, & Prendergast C (2005) Favoritism under social pressure. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87, 208-216.

Green, C. and Simmons, R. 2014. The English disease: Has football hooliganism been eliminated or merely displaced? Lancaster University Management School Working Paper.

Harrington, J. (1968). Soccer Hooliganism. Bristol: John Wright

King, A (2002) The End of The Terraces. London: Leicester University Press.

Marsh P, Rosser E & Harré R. (1978). The Rules of Disorder. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Pearson, G. (1999). Legitimate targets? The civil liberties of football fans. Journal of Civil Liberties, 4, 28-47.

Pettersson-Lidborn, P. and Priks, M. (2010). Behavior under social pressure: Empty Italian stadiums and referee bias. Economics Letters, 108, 212-214.

Poutvaara, P. & Priks, M. (2009). Supporter violence and police tactics. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 11, 441-453.

23

Priks, M. (2010). Does frustration lead to unruly behaviour? Evidence from the Swedish hooligan scene. Kyklos, 63, 450-460.

Priks, M. (forthcoming). Do surveillance cameras affect unruly behaviour? A close look at grandstands. Scandinavian Journal of Economics.

Rees, D & Schnepel, K. (2009). College football games and crime. Journal of Sports Economics, 10, 68-87.

Rookwood, J. and Pearson, G. (2012) “The hoolifan: Positive fan attitudes to football ‘hooliganism’ ”, International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 47(2), 149-164

Stott, C. & Pearson, G. (2007). Football ‘hooliganism’. London: Pennant Books.

Szymanski, S. (2012). Insolvency in professional football: Irrational exuberance or negative shocks? International Association of Sports Economists and North American Association of Sports Economists, Working Paper 1202.

Szymanski, S. & Kuypers, T. (1999). Winners and losers: The business of football. London: Viking Press.

Szymanski, S. & Smith, R. (1997). The English football industry: Profit, performance and industrial structure. International Review of Applied Economics, 11, 135-153.

Taylor I. (1971). Football mad: a speculative sociology of football hooliganism. In E Dunning (ed.) The Sociology of Sport: A Selection of Readings. London: Frank Cass.

Lord Justice Taylor (1990) The Hillsborough Stadium Disaster. London: HMSO, Cm962

Taylor, M. (2008) The Association Game: A History of British Football. Pearson.

Tsoukala, A. (2009) Football Hooliganism in Europe: Security and Civil Liberties in the Balance. London: Palgrave Macmillan

24

Table OneSummary Statistics

1985/86 to 1994/95 (n = 839)

Variable Mean Std. Dev. Min MaxNominal Revenue (£m) 2.94 4.41 0.20 60.62Log Real Revenue 2.95 1.43 0.37 6.73Total Arrest Rate 0.15 0.14 0.003 1.14Log Total Arrest Rate -2.24 0.89 -5.94 0.13Lag Log Total Arrest Rate -2.16 0.92 -5.94 0.24Rank -11.92 6.61 -24 -1Log Rank -2.24 0.81 -3.18 0Lag Promoted 0.11 0.31 0 1Lag Relegated 0.11 0.31 0 1Allseater 0.09 0.28 0 1Derby1 0.29 0.45 0 1Derby2 0.08 0.27 0 1

2002/03 to 2009/10 (n = 551)

Variable Mean Std. Dev. Min MaxNominal Revenue (£m) 42.00 63.27 0.17 379.86Log Real Revenue 2.87 1.33 -1.78 5.94Home Arrest Rate 0.05 0.04 0.002 0.36Log Home Arrest Rate -3.35 0.90 -6.29 -1.03Lag Log Home Arrest Rate -3.33 0.88 -6.29 -1.03Total Arrest Rate 0.05 0.04 0.002 0.25Log Total Arrest Rate -3.19 0.80 -6.01 -1.39Lag Log Total Arrest Rate -3.18 0.79 -6.01 -1.39Rank -11.35 6.63 -24 -1Log Rank -2.17 0.83 -3.18 0Lag Promoted 0.12 0.32 0 1Lag Relegated 0.11 0.32 0 1Allseater 0.81 0.39 0 1Derby1 0.32 0.47 0 1Derby2 0.11 0.31 0 1

25

Table TwoArrest Rate Equation Dependent Variable = Log Total Arrest Rate1985/86 to 1994/95 (n = 839)

Variable Coefficient(robust s.e)

Coefficient(robust s.e)

Coefficient(robust s.e)

Lag Log Total Arrest Rate 0.171 (0.044)*** 0.170 (0.044)*** 0.171(0.044)***Rank -0.013 (0.006)**Log Rank -0.080 (0.048)*Rank Upper Middle 0.064 (0.082)Rank Lower Middle 0.215 (0.087)**Rank Low 0.177 (0.115)Lag Promoted 0.276 (0.079)*** 0.266 (0.078)*** 0.269 (0.080)***Lag Relegated 0.051 (0.082) 0.053 (0.083) 0.047 (0.083)Allseater -0.113 (0.124) -0.114 (0.125) -0.117 (0.124)Derby1 0.079 (0.076) 0.083 (0.076) 0.084 (0.075)Derby2 0.079 (0.146) 0.083 (0.145) 0.089 (0.151)Division2 0.147 (0.126) 0.130 (0.128) 0.139 (0.126)Division3 -0.057 (0.171) -0.095 (0.168) -0.076 (0.170)Division4 -0.047 (0.225) -0.102 (0.222) -0.079 (0.220)

R2 0.418 0.416 0.418All estimations include fixed effects for year and club*significant at 10% level**significant at 5% level***significant at 1% level

26

Table Three Revenue EquationDependent Variable = Log Real Revenue1985/86 to 1994/95 (n = 839)

Variable Coefficient(robust s.e)

Coefficient(robust s.e)

Coefficient(robust s.e)

Predicted Log Total Arrest Rate

-0.175 (0.088)** -0.163 (0.087)* -0.169 (0.087)*

Rank 0.017 (0.003)***Log Rank 0.146 (0.019)***Rank Upper Middle -0.187 (0.037)***Rank Lower Middle -0.229 (0.039)***Rank Low -0.304 (0.047)***Lag Promoted 0.073 (0.053) 0.075 (0.053) 0.075 (0.052)Lag Relegated 0.093 (0.033)*** 0.091 (0.031)*** 0.093 (0.032)***Allseater 0.004 (0.064) 0.015 (0.063) 0.016 (0.064)Derby1 0.055 (0.041) 0.055 (0.041) 0.049 (0.040)Derby2 0.136 (0.067)** 0.131 (0.071)* 0.121 (0.070)*Division2 -1.355 (0.048)*** -1.364 (0.044)*** -1.361 (0.047)***Division3 -2.134 (0.075)*** -2.141 (0.071)*** -2.119 (0.074)***Division4 -2.853 (0.100)*** -2.859 (0.096)*** -2.826 (0.098)***

R2 0.965 0.967 0.966Endogeneity Tests (p values)Wooldridge Score 0.038 0.053 0.037All estimations include fixed effects for year and club*significant at 10% level**significant at 5% level***significant at 1% level

27

Table Four Home Arrest Rate and Revenue Equations 2002/03 to 2009/10 (n = 551)

Dependent Variable

Log Home Arrest RateFirst Stage

Log Real Revenue

2SLS

Log Home Arrest RateFirst Stage

Log Real Revenue

2SLSCoefficient(robust s.e)

Coefficient(robust s.e)

Coefficient(robust s.e)

Coefficient(robust s.e)

Predicted Log Home Arrest Rate

0.205 (0.381) 0.087 (0.204)

Log Lag Home Arrest Rate

-0.049 (0.047) -0.054 (0.047)

Log Rank -0.096 (0.048)** 0.092 (0.042)**Rank Upper Middle

-0.002 (0.103) -0.107 (0.036)***

Rank Lower Middle

0.096 (0.113) -0.139 (0.045)***

Rank Low 0.152 (0.125) -0.239 (0.051)***Lag Promoted 0.295 (0.139)** -0.081 (0.125) 0.296 (0.135)** -0.045 (0.101)Lag Relegated -0.114 (0.124) 0.200 (0.067)*** -0.103 (0.122) 0.175 (0.053)***Allseater -0.462 (0.431) 0.292 (0.259) -0.467 (0.425) 0.230 (0.205)Derby1 0.119 (0.108) 0.033 (0.062) 0.126 (0.110) 0.040 (0.052)Derby2 0.268 (0.155)* 0.007 (0.127) 0.294 (0.152)* 0.012 (0.113)Division2 0.173 (0.151) -1.161 (0.114)*** 0.152 (0.155) -1.158 (0.101)***Division3 0.416 (0.203)** -1.640 (0.196)*** 0.364 (0.202)* -1.612 (0.152)***Division4 0.642 (0.301)** -2.187 (0.281)*** 0.570 (0.302)* -2.136 (0.213)***R2 0.463 0.971 0.461 0.979Endogeneity Test (p values)Wooldridge Score 0.700 0.686All estimations include fixed effects for year and club*significant at 10% level**significant at 5% level***significant at 1% level

28

Table Five Total Arrest Rate and Revenue Equations 2002/03 to 2009/10 (n = 551)

Dependent Variable Log Total Arrest Rate

First Stage

Log Real Revenue2SLS

Coefficient(robust s.e)

Coefficient(robust s.e)

Predicted Log Total Arrest Rate 1.212 (2.942)Log Lag Total Arrest Rate -0.024 (0.060)Log Rank -0.014 (0.047) 0.088 (0.067)Lag Promoted 0.246 (0.094)*** -0.314 (0.729)Lag Relegated -0.134 (0.096) 0.339 (0.412)Allseater -0.185 (0.292) 0.429 (0.709)Derby1 0.041 (0.071) 0.006 (0.153)Derby2 0.128 (0.125) -0.095 (0.397)Division2 0.234 (0.111)** -1.403 (0.721)*Division3 0.343 (0.163)** -1.966 (1.015)*Division4 0.521 (0.240)** -2.681 (1.538)*R2 0.605 0.804Endogeneity Test (p values)Wooldridge Score 0.176All estimations include fixed effects for year and club*significant at 10% level**significant at 5% level***significant at 1% level

29

APPENDIXOLS Revenue Equations Dependent variable = Log Real Revenue

Total Arrest Rate 1985/86 to 1994/95

(n = 839)

Home Arrest Rate 2002/03 to 2009/10

(n = 551)

Total Arrest Rate 2002/03 to 2009/10

(n = 551)Variable Coefficient

(robust s.e)Coefficient(robust s.e)

Coefficient(robust s.e)

Log Arrests -0.008 (0.014) -0.012 (0.015) -0.017 (0.024)Rank 0.188 (0.002)*** 0.010 (0.002)*** 0.010 (0.002)***Lag Promoted 0.032 (0.043) -0.013 (0.035) -0.013 (0.034)Lag Relegated 0.078 (0.033)** 0.165 (0.043)*** 0.164 (0.043)***Allseater 0.027 (0.064) 0.180 (0.142) 0.183 (0.141)Derby1 0.040 (0.039) 0.057 (0.042) 0.057 (0.041)Derby2 0.117 (0.066)* 0.048 (0.096) 0.047 (0.096)Division2 -1.380 (0.051)*** -1.118 (0.089)*** -1.116 (0.088)***Division3 -2.114 (0.073)*** -1.550 (0.103)*** -1.549 (0.102)***Division4 -2.834 (0.093)*** -2.053 (0.118)*** -2.051 (0.117)***R2 0.971 0.981 0.981All estimations include fixed effects for year and club*significant at 10% level**significant at 5% level***significant at 1% level

30