Veneers

-

Upload

mirfanulhaq -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Veneers

-

PRACTICE

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 193 NO. 2 JULY 27 2002 73

Crowns and other extra-coronal restorations:Porcelain laminate veneersA. W. G. Walls1 J. G. Steele2 and R. W. Wassell3

Porcelain veneers are resin-bonded to the underlying tooth and provide a conservative method of improving appearance ormodifying contour, without resorting to a full coverage crown. The porcelain laminate veneer is now a frequently prescribedrestoration for anterior teeth. The sums spent by the Dental Practice Board on this type of treatment increased from quarterof a million pounds in 1988/89 to over seven million in 1994/95,1 representing some 113,582 treatments. Since that time thenumber has stabilised at over 100,000 veneers prescribed each year.2 The objective of this paper is to give a practical guideon providing these restorations.

1*Professor of Restorative Dentistry,2,3Senior Lecturer in Restorative Dentistry,Department of Restorative Dentistry, TheDental School, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 4BW; *Correspondence to: Prof A. W. G. Walls,Department of Restorative Dentistry, TheDental School, University of Newcastleupon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 4BWE-mail: [email protected]

Refereed Paper British Dental Journal 2002; 193:7382

The development of porcelain veneers Longevity and factors affecting it Tooth preparation, and management of existing restorations Impression recording and temporisation (in those few cases which require it) Try in, bonding and finishing Non-standard porcelain veneers

I N B R I E F

Whenever possible guidelines for provision ofporcelain laminate veneers are based on datafrom the dental literature, but where this is notpossible they will be based on our clinical expe-rience and practice. Veneers are often placed onthe buccal aspect of maxillary anterior teeth butother applications are possible and these aredescribed at the end of the article.

HISTORY The concept of veneering was first described inthe dental literature some time ago,3 although itis only with the advent of efficient bonding ofresins to enamel and dentine and the use ofetched, coupled porcelain surfaces that aestheti-cally pleasing, durable and successful restora-tions can be made.4 These restorations are nowan accepted part of the dentists armamentari-um.57 Custom-made acrylic resin veneers pre-ceded them, but these showed unacceptable lev-els of failure and of marginal stain.8 Alternativeveneering materials are still available, usuallyeither direct or indirect composite resin materi-als. However, these may suffer from degradationof surface features and accretion of surface stainwith time.911

Porcelain veneers have traditionally beenmade from aluminous or reinforced feldspathicporcelains, which have relatively poor strengthin themselves but produce a strong structurewhen bonded to enamel. Porcelain veneers canbe made from most of the high strength ceramicsdiscussed in the second article of the series. Suchmaterials may hold promise for the future. Astudy of 83 IPS Empress veneers placed over a 6-year period in private practice reported onlyone failure, but as yet there are no clinical data

making a direct comparison between these andthe traditional materials.

That the strength of traditional porcelain isgenerally adequate for anterior porcelainveneers is supported by a number of clinicalstudies. Some authors9,1217 have reported lowrates of failure because of the loss of retentionand fracture (05%) with short and medium-term studies of up to 5 years. Indeed, a long-termfollow-up18 of veneers placed over a 10-yearperiod shows a survival rate of 91% at 10.5 years(calculated with the Kaplan Meyer method).These excellent results may, amongst otherthings, reflect careful case selection, but it isworth noting that other authors,5,13,19,20 havereported much higher rates of failure of between714% over 25 years. Such studies suggest thatthe risk factors for veneer failure are:

Bonding onto pre-existing composite restora-tions (which is considered later)

Placement by an inexperienced operator Using veneers to restore worn or fractured

teeth where a combination of parafunction,large areas of exposed dentine and insufficienttooth tissue exist.

Another risk factor, shown up by in-vitrowork, is the tendency for thermal changes incombination with polymerisation contractionstresses to cause cracking of the veneer when theporcelain is thin and the luting compositethick.21 A thick composite lute may occur as aresult of a poorly fitting veneer or the use ofcopious die spacer in an attempt to mask under-lying tooth discolouration. Least cracking wasseen with a ceramic and luting composite thick-ness ratio above 3.

12

CROWNS AND EXTRA-CORONALRESTORATIONS:1. Changing patterns and

the need for quality2. Materials considerations3. Pre-operative

assessment4. Endodontic

considerations5. Jaw registration and

articulator selection6. Aesthetic control7. Cores for teeth with

vital pulps8. Preparations for full

veneer crowns9. Provisional restorations 10. Impression materials and

technique11. Try-in and cementation

of crowns 12. Porcelain veneers13. Resin bonded metal

restorations

-

PRACTICE

74 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 193 NO. 2 JULY 27 2002

In-vivo, minor chipping and cracking may besmoothed or repaired without the need toremove the whole veneer. Dunne and Millarreported that the incidence of such repairabledefects (8%) was similar to the number ofveneers requiring total replacement (11%).5

It is useful to be aware of the above data whenpatients ask how long their proposed veneers arelikely to last. It may also be prudent to warn themthat although most (80100%)7 patients remainsatisfied with the aesthetics, veneers are prone tomarginal staining, the amount of which will varyfrom patient to patient. Staining may be causedby one or more of the following:

Microleakage at the cervical margin, especial-ly where located in aprismatic enamel or,worse still, dentine

Wear and submargination of the luting com-posite, especially with an open margin

Marginal excess of luting composite

To some extent, these factors can be con-trolled or influenced by careful attention to clin-ical technique.

CLINICAL TECHNIQUEA key element in success with porcelain veneersis carefully controlled but appropriate tooth tis-sue reduction.2224 The aims of tooth prepara-tion are to:

Provide some space into which the techniciancan build porcelain without over-contouringthe tooth

Provide a finished preparation that is smoothand has no sharp internal line-angles whichwould give areas of high stress concentrationin the restoration

Maintain the preparation within enamelwhenever possible

Define a finish line to which the techniciancan work.

It may be possible to prepare veneer prepara-tions without local anaesthetic. However, in ourexperience, sub-gingival margin placement,inadvertent dentine exposure and the unpleas-ant coldness from the water spray and aspiratorusually make its use advisable.

Depth of preparationIt is desirable for the tooth preparation to remainwithin enamel so careful control of preparationdepth is important. Obviously, the enamel thick-

ness varies from the incisal edge to the cervicalmargin. Hence the preparation depth will need tovary over the length of the tooth to avoid (if pos-sible) exposing dentine. The preparation depthshould be of the order of 0.4 mm close to the gin-gival margin, rising to 0.7 mm for the bulk of thepreparation. This is best achieved by using adepth mark of some sort. In our experience formaldepth grooves can be of limited value in this areaas there is a tendency for the bur to catch and runinto the groove during buccal reduction, accentu-ating the groove. The alternative is to use depthpits prepared on the surface of the tooth using a 1mm diameter round bur sunk to half its diameter(Fig. 1). The buccal surface reduction can then beundertaken to join the base of the pits. The reduc-tion should mimic the natural curvature of thetooth in order to provide an even thickness ofporcelain layer over the tooth surface, hence itshould be in at least two planes.24

When the tooth concerned is markedly dis-coloured, it is sensible to undertake a greater levelof reduction to give the technician more chance tomask the underlying stain without over-contour-ing the tooth. This will have obvious disadvan-tages, as the preparation is likely to extend intodentine with greater depth of tooth reduction.

Nattrass et al.25 have demonstrated that evenwith experienced operators and careful controlof cutting instruments there is a tendency fordentine to be exposed in the cervical and proxi-mal regions of the preparations, where theenamel is thinnest. This should be borne in mindwhen deciding on the type of luting agent to beused in veneer placement. They also found thatthere was a tendency for variations in toothpreparation depth across their samples with leastreduction in the mid-incisal region. There is nosuggestion in the literature as yet that this caus-es any long-term damage to the tooth or affectsthe longevity of the veneer.

Incisal edge reductionOne important decision to make before com-mencing the preparation is whether or not theincisal edge of the tooth is to be reduced. Thereare four basic preparation designs that havebeen described for the incisal edge (Fig. 2):

Window, in which the veneer is taken close tobut not up to the incisal edge. This has theadvantage of retaining natural enamel over theincisal edge, but has the disadvantage that theincisal edge enamel is weakened by the prepa-ration. Also, the margins of the veneer wouldbecome vulnerable if there is incisal edge wearwhilst the incisal lute can be difficult to hide.

Feather, in which the veneer is taken up to theheight of the incisal edge of the tooth but theedge is not reduced. This has the advantagethat once again guidance on natural tooth ismaintained but the veneer is liable to be frag-ile at the incisal edge and may be subject topeel/sheer forces during protrusive guidance.

Bevel, in which a bucco-palatal bevel is pre-pared across the full width of the preparation

Fig. 1 A 1 mm round diamond burbeing used to create depth marks onthe buccal surface of UR1 (11)

-

PRACTICE

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 193 NO. 2 JULY 27 2002 75

and there is some reduction of the incisallength of the tooth. This gives more controlover the incisal aesthetics and a positive seatduring try in and luting of the veneer. The mar-gin is not in a position that will be subjected todirect shear forces except in protrusion. How-ever, this style of preparation does involvemore extensive reduction of tooth tissue.

Incisal overlap, in which the incisal edge isreduced and then the veneer preparationextended onto the palatal aspect of the prepa-ration. This also helps to provide a positiveseat for luting whilst involving more exten-sive tooth preparation. This style of prepara-tion will also modify the path of insertion ofthe veneer which will have to be seated fromthe buccal/incisal direction rather than thebuccal alone. Care needs to be taken to ensurethat any proximal wrap around of the prepa-ration towards the gingival margin does notproduce an undercut to the desired path ofinsertion for the veneer. It may be necessary torotate such veneers into place by locating theincisal edge first then rotating the cervicalmargin into position.

There is little data available upon which tobase a decision over incisal edge preparation.Hui et al.26 demonstrated that veneers in win-dow preparations were best able to resist incisaledge loading and that an overlap design frac-tured at the lowest loads. However, the magni-tude of loading at which the overlap designveneers failed was much greater than thatencountered clinically for such teeth. Further-more, a clinical study was unable to distinguishany difference in failure rate between incisalpreparation designs after two and a half years ofservice.27 If the operator intends to eitherimprove the incisal edge aesthetics or to increasethe length of a tooth then either an overlap orbevel design would be the preparation of choice.If it were not necessary to extend the incisaledges, then it may be possible to use a feather-edge design, however the operator has less con-trol of incisal edge aesthetics with this approach.Nordbo et al.14 report no failures but 5% incisalchipping at 3-years for veneers placed using afeather-edge design and 0.3 to 0.5 mm buccaltooth reduction.

The authors would not recommend the buccalwindow, as it is very difficult to mask the incisalfinish line of the restoration. As this style ofrestoration is used to improve the appearance ofteeth, the introduction of an aesthetic defectwould be inappropriate. If the incisal edge is to bemodified then the length should be reduced bysome 0.50.75 mm28 to allow adequate strengthwithin the porcelain incisal edge without elongat-ing the tooth. Depth grooves can be used to moni-tor accurately incisal edge reduction (Fig. 1); wewould strongly recommend this approach.

Axial tooth reductionAxial tooth reduction is best undertaken usingdiamond burs in either an airotor or a speed

accelerating handpiece with a conventionalmotor. It is easier to achieve predictable toothreduction using either a parallel sided or taperedbur with straight sides rather than a flame-shaped bur (Fig. 3). Some clinicians advocatepreparing the gingival finish line as the first stepusing a round diamond bur of appropriate diam-eter, which will automatically produce a cham-fered finish line. Alternatively a torpedo shapedbur can be used to produce both the axial reduc-tion and the gingival finish line (Fig. 4), which isthe method we prefer.

Conventional diamond burs leave a macro-scopically roughened surface on enamel. Furtherpreparation of the tooth using either a small par-ticle size diamond bur or a multi-fluted tungstencarbide finishing bur will smooth the surface ofthe preparation and can be used to refine the fin-ishing margin. At this stage the gingival tissues

a) b)

c) d)

Fig. 2 Four incisal preparations are possible for veneers: a) window , b) feather , c) bevel or d) incisal overlap

Fig. 3 Straight sided torpedo-shapeddiamond bur provides morepredictable axial reduction inassociation with depth marks than aflame-shaped bur

-

PRACTICE

76 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 193 NO. 2 JULY 27 2002

can be protected from damage using a flat plas-tic instrument (Fig. 5) or gingival retraction cordcan be packed for the same purpose, which willin turn facilitate the impression. It is oftenimpractical to provide provisional restorationsfor porcelain veneers (see later) but somepatients are conscious of the roughened toothsurface in their mouths, which should besmoothed.

Proximal finish linesIt is best if the proximal finishing margins forthe preparation do not extend beyond the con-tact point in the incisal third of the tooth inother words, the contact point with adjacentteeth should be maintained. If it proves neces-sary to prepare through the contact area thensome form of provisional restoration would berequired to prevent inadvertent tooth movementbetween tooth preparation and fitting of theveneers. Cervically it may be necessary toextend the preparation into the gingival embra-sure to mask discoloured tooth substance in theproximal zone immediately above the interden-tal papilla. Care must be used not to create anundercut preparation in this area to the proposedpath of insertion of the restoration.

It is usually necessary to trim the proximalfinish line with a chisel to avoid the sharp lip ofenamel that often results from being unable totake the bur to the very edge of the preparation.In this respect it is better to change to a smallerdiameter bur to prepare the proximal margins ofa single tooth being veneered to permit limitedtooth reduction without damaging the adjacenttooth.

Cervical finish linesThe cervical finish lines for a veneer should be achamfer with about a 0.4 mm maximum depth.

The rounded internal line angle will help toreduce stresses in the margin of the veneer thatmay otherwise develop during firing. Also,porcelain will adapt more readily to this shapeduring manufacture. The finish line should liejust at the crest of the free gingival margin,unless the veneers are being used to mask severestaining when greater sub-gingival extensionmay be required for aesthetic reasons. This posi-tion for the gingival extension of the veneerusually gives the best compromise between aes-thetic control of the finished restoration and theease with which the clinician can control mois-ture during luting.

It is helpful to have a defined cervical finish-ing margin so that the porcelain technician willbe able to identify clearly the desired extent ofthe veneer. However, there is a tendency for thecervical margins of finished veneers to be over-bulked to give greater durability during clinicalhandling. These margins should therefore bethinned as well as finished after luting.

Coping with pre-existing restorationsSome teeth that require veneers will have exist-ing composite resin restorations in place. Thereare two ways to deal with this:

Bond to a prepared composite resin surface.This is difficult, particularly if the compositerestoration has been in place for any length oftime. Water sorption, exposed un-silanatedsurfaces of filler particles and limited opportu-nities for further polymerisation of the resincomponent of the set material all contribute toa reduced bond strength.

Replace the restoration. This can be done rela-tively easily, but should be done at the visitwhen the veneer is luted to the tooth so thenew composite has the best chance of bondingto the porcelain veneer as well as the tooth tis-sue. This makes the procedure for bonding theveneer more complex. The old restorationneeds to be removed before the veneer isattached to the tooth. The veneer is then lutedin place using the requisite bonding systemand subsequently the composite resin restora-tion replaced in the same manner as whenplacing a conventional Class III or IV compos-ite filling. It can be difficult to avoid produc-ing overhanging margins using this tech-nique, so care is required to ensure that anysuch overhangs are identified and eliminated.

One of the causes for failure that Dunne andMillar5 identified was that veneers were attachedto pre-existing restorations. It would seem sensi-ble to replace such restorations at the time ofveneer placement to reduce this as a possiblecause of early failure of the veneer. Alternative-ly, if there are extensive restorations present itmay be more sensible to provide a crown.

Recording an impressionImpression technique and soft tissue handlingare dealt with elsewhere in this series, so we willnot go into great detail here. However it is

Fig. 4 The torpedo bur can also beused to create the gingival bevel

Fig. 5 A flat plastic instrumentprotects the gingivae duringfinishing of the chamfer with amulti-fluted tungsten carbide bur. A speed accelerating handpieceprovides greater control than anairotor

-

PRACTICE

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 193 NO. 2 JULY 27 2002 79

appropriate to use short sections of retractioncord around the margins of the preparations tofacilitate the capture of both the finishing edgeof the preparation and the adjacent area ofunprepared tooth. Electro-surgery is best avoid-ed because of the risk of gingival recessionrevealing the veneer margin.

An impression of the opposing arch is indis-pensable if the incisal edges of the veneers areinvolved in guidance.

Laboratory prescription and manufactureAgain, communication with your technician andachieving maximum aesthetics is covered else-where in this series. Of particular importance inrelation to veneers is careful shade selection,especially if you are planning to modify thecolour of the tooth. If you intend to attempt tomodify the shade of the veneer with the lutingagent then it is sensible to ask the technician toprovide space for the luting resin using a propri-etary die-spacing system but bear in mind thatthe porcelain should not be so thin that there is arisk of it being cracked by the thick compositelute.21 In addition, if a diagnostic wax-up hasbeen used to demonstrate a modification inanterior aesthetics then this should be sent to thelaboratory as well. It can also be beneficial tosend a study cast of the teeth prior to prepara-tion if one is available should you want to pre-serve the original tooth form.

There are a variety of methods for manufac-ture of porcelain veneers using either a refracto-ry die material, a platinum matrix laid down ona conventional working model or one of thecastable ceramic materials prepared using thelost wax technique. Sim and Ibbetson29 haveshown that the best quality of marginal fit wasobtained with a platinum foil system, followedby a refractory die and that the worst fit wasassociated with cast glass restorations.

It is best to ask your laboratory for the veneerto be etched with hydrofluoric acid but not toapply the silane-coupling agent. These agentsneed to be applied just prior to luting the veneerin place (whether or not the laboratory hasapplied silane) and are provided in most com-mercially available resin luting kits. Too early anapplication of a coupling agent, or contamina-tion of the coupling agent coated surface prior tobonding can reduce the strength of the attach-ment between resin and veneer. Also, two com-ponent silane systems must not be kept aftermixing as the silane polymerises to an unreac-tive polysiloxane, again with a reduction inbond strength.7

Provisional restorationsIt is difficult and time-consuming to provideprovisional restorations for teeth prepared forporcelain veneers. It is often best simply to leavethe teeth in their prepared state providing thepatient is aware that this is going to happen andthe teeth are not sensitive.

A variety of techniques have been describedfor placement of provisional restorations if they

are required. These include directly placed com-posite resin veneers and producing a transparentmatrix from a thermoplastic material to allowmultiple composite veneers to be made simulta-neously.30 Such provisional restorations need tobe attached to the enamel surface and the onlypractical way to do this is using the acid etchtechnique. Obviously, only a very small area ofenamel in the centre of the preparation shouldbe spot-etched to provide attachment for thecomposite resin, which can then be removedeasily during the next visit without damagingthe periphery of the preparation. It is best toavoid the margins of the preparations whendoing this with spot etching at the centre only.

Provisional restorations should be made withcare, avoiding gingival excess. Any such excesswould cause gingival irritation whilst theveneers are being made and may result in analteration of the position of the gingival marginor cause difficulty with bleeding during luting.

Provisional restorations are useful when youplan to alter the position of the teeth usingveneers. The diagnostic wax-up can be used toprepare a thermoplastic matrix. This matrix isthen used to make composite resin veneersdirectly in the mouth. This will allow the patientto experience the planned changes to their teethat first hand and to approve the change in theirappearance before the definitive restorations aremade, avoiding a potential cause for grievance.

Trial placement. The veneers should bereturned from the laboratory in a foam-linedbox rather than on the working model of thepatient. It is important that neither you nor thelaboratory place the etched veneers back on thestone dies. Any contact between the etchedporcelain surface and dental stone will result inabrasion of the stone model and some stone dustbecoming trapped in the delicate veneer surface.Swift et al.31 have shown that such contamina-tion results in a substantial fall in the bondstrength between veneer and resin. They alsofound that it was very difficult to clean anetched porcelain surface that has been contami-nated with dental stone.

Handling porcelain veneers can be difficult;they are small and delicate. There are commer-cially available devices to help with this, eitherin the form of a tiny suction cup or a small rodwith a tacky resin at one end. Alternatively a lit-tle piece of ribbon wax on the end of an amal-gam plugger makes a useful substitute.

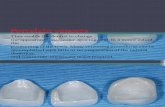

Check the quality of fit and gingival extensionof the veneer against the tooth, which shouldhave been cleaned with pumice in water prior tothe trial. Once you are happy that the quality of fitis acceptable, the next stage is to assess the colourmatch. The colour of a porcelain veneer cannot beassessed if the veneer is simply placed on the sur-face of the tooth. Much of the overall colour forthe final restoration comes from the tooth struc-ture, so a colour-coupling agent is neededbetween the tooth and the veneer (Fig. 6).

In its simplest form water will allow thecolour of the tooth to be expressed through the

-

PRACTICE

80 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 193 NO. 2 JULY 27 2002

veneer and give a reasonable guide to the overallappearance if a neutral coloured luting resin isto be used.

If it is necessary to try to modify the colour ofthe finished restoration using the luting resinthen the veneer must be tried in with an appro-priate colour of paste. This can either be the lut-ing agent itself or, alternatively, some manufac-turers provide trial pastes that will not set buthave similar optical properties to the luting resin.If the definitive luting resin is used great caremust be taken to ensure that the resin does not setunder the action of the operating light and thatthe paste used for the trial is removed completelyfrom the veneer. Some manufacturers trialpastes are water-soluble making their removalrelatively straightforward. However if a resinbased trial paste is used this needs to be removedusing an organic solvent. Swift et al.31 found thatacetone, an agent that has often been suggestedand used for this role, produces markedlyreduced bond strengths. A more acceptable alter-native would be ethanol. Once the quality of fitof the veneer and the shade of the luting pastehave been assessed the etched surface of theporcelain should be coated with a silane couplingagent, following the manufacturers instructionsfor the product chosen.

Luting the veneerHaving established that the veneer is of anappropriate shade, or can be modified with a lut-ing resin to be satisfactory, it is ready to be bond-ed to the supporting enamel and dentine. In viewof the reported high prevalence of dentine expo-sure on veneer preparations25 we would advisethe routine use of a dentine bonding agent.

Good moisture control is critical if adhesivetechniques are to work. Contamination of eitherthe prepared tooth surface or the veneer fitting

surface with saliva, blood or crevicular fluid willresult in reduced bond strengths. Moisture con-trol can be achieved using rubber dam, butwhere this is impractical gingival retraction cordcan be a helpful adjunct to prevention of con-tamination from the gingival crevice. The resid-ual enamel should be cleaned using pumice andwater and then etched, washed and dried. Detailsof technique will not be given here, as they areso material specific. It can be tempting to cutcorners during this stage, but it is vital that youuse the luting resins as the manufacturer sug-gests to achieve optimal results.

Having applied the dentine/enamel bondingsystem the veneer should be loaded with lutingresin and located on the surface of the tooth. Atthis stage the excess of unset resin around theperiphery of the veneer can best be removedusing a metal instrument (Fig. 7) or a brushdipped in unfilled resin. Removal needs to beundertaken with care, as there is a tendency forresin to be pulled out from the periphery of thelute space leaving sub-margination, particularlyif dental floss is used.

Once all gross excess is removed the lutingresin can be cured using a visible light activationunit. It is essential to ensure an adequate exposureto cure fully the luting resin through the porcelainveneer. Most manufacturers guidelines suggest3040s cure times. This is inadequate withresearch suggesting that 60s is more realistic.3234

Light-activation of a luting agent through anopaque veneer or one of greater than 0.7 mmthickness, is not adequately effective.35 In thesecircumstances a dual-curing resin, which is ini-tiated both by admixing the pastes to give achemical set and by visible-light activation,should be used. Such dual-cure agents shouldnot be used on thinner veneers as they do notpolymerise as effectively as a visible-light acti-vated equivalent alone and may be susceptibleto colour change with time as a product of theresidue of the chemical initiating system.36

Post placement finishingThe final stage for any restoration is finishing themargins of the restoration and any functionalcontacts to give a smooth and harmonious transi-tion from tooth to restoration. It is particularlyimportant to eliminate any occlusal interferences.The finishing process for porcelain veneersinvolves using small particle size diamond burs ormulti-fluted tungsten carbide burs in either anairotor or a speed accelerating handpiece (Fig. 8).Burs are available in a variety of grit sizes to pol-ish the margins progressively and ideally shouldbe followed by the use of 10 mm particle size dia-mond polishing paste to maximise the lustre onthe porcelain and the cement lute (Fig. 9). Finish-ing can also be achieved using rotating abrasivedisks that are available for composite resinrestorations (eg Soflex discs, Super-Snaps etc).

When finishing the gingival extent of theveneer it is sensible to protect the gingival tis-sues using a flat plastic instrument. You willwant to show the finished result to your patient,

Fig. 6 The advantages of using acolour-coupling agent are seen here.The veneer at UL1(21) looksrelatively translucent (try-in pasteused) compared with the opaqueUR1(11) (no try-in paste used)

Fig. 7 Prior to curing the lutingagent, excess material must beremoved from the margin of theveneer and the gingival crevice.Note the small sections ofMelamine matrix used to preventthe luting agent from bonding teethtogether

-

PRACTICE

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 193 NO. 2 JULY 27 2002 81

who will not be impressed if the gingival tissuesare lacerated and bleeding! Many operators pre-fer to delay the detailed finishing until a subse-quent appointment at which time any excessmaterial is much easier to identify.

NON-STANDARD VENEERSVeneers are generally prescribed for the buccalaspects of maxillary anterior teeth, but there area number of non-standard applications. Theseinclude veneers for:

The palatal/lingual aspect of teeth which havebeen worn or fractured

Diastema elimination using slips restricted tothe proximal aspects of teeth

Lower incisors Posterior occlusal onlays

All of these applications require some carefulthought to ensure a satisfactory result.

Palatal veneersThere are two main problems with palatalveneers.

Firstly, it is not possible to adjust the occlusalcontacts on the veneer until it is luted in place.This will inevitably result in the need to adjustporcelain in situ. When this is required it isessential that the adjusted porcelain surface bepolished with graded abrasives, culminating indiamond paste, to ensure that the opposing teethare not subject to excessive wear from rough-ened unglazed porcelain.

Secondly, the finish line for such veneers oftenextends onto the buccal surface of the tooth. Itcan be very difficult to disguise that line as theresin luting agent can prove highly visible at thejunction between porcelain and tooth (Fig. 10).One option is to try to hide the finish line as muchas possible. There are three ways to improve this: Never make the finish line a straight line. The

human eye is very good at identifying straightlines, but is less good at seeing wavy lines. Ifthe finish line is made serpentinous, using thenormal anatomy of the tooth to rise over themamelons and dip between them, it becomesmore difficult to see (Fig. 11).

Extend the finish line over onto the buccalsurface of the tooth significantly. Then askyour technician to gradually increase thequantity of translucent porcelain in the over-lapping section so that more and more colourfrom the restoration is drawn from the toothand less and less from the veneer. This avoidssudden change in optical properties betweentooth and porcelain restoration. (Figs 10,11)

Use a luting agent that is colour neutral withthe tooth so that it blends as much as possible.

Lateral porcelain slipsThere are once again two problems with this sortof porcelain addition, commonly used to obliter-ate a diastema between teeth.

Care must be taken to avoid a bulky gingivalemergence profile. It is not acceptable to pro-

duce artificial overhangs that are not cleans-able and are liable to act as plaque traps.

The junction between porcelain and toothshould be disguised. This is best hidden withinthe natural anatomy of the tooth by placingthe finish line within the intermamelongroove closest to the addition and by using thesame concepts as above to blend tooth andporcelain. In this circumstance it may be pos-sible to have a straight finish line, at worst itmimics a crack on the crown surface.

An alternative is simply to extend the veneerover the whole buccal surface with an appropri-ate extension into the proximal space.

Veneers for mandibular incisorsMandibular incisors can be managed withporcelain veneers but the preparation usuallyhas to be extended over the incisal edge of thetooth, particularly if the tooth is in functionalcontact. The incisal coverage of porcelain has tobe sufficiently thick to be durable under contin-uing rubbing contact with the opposing tooth.This would necessitate incisal edge reduction bybetween 0.75 and 1 mm. Obviously if the tooth isnot temporised there is a risk of over-eruption of

Fig. 8 Finishing the gingival marginof the veneer with a small particlesize diamond bur in a speedaccelerating handpiece. Once again,a flat plastic instrument protects thegingival tissues

Fig. 9 Final polishing of the gingivalmargin of the veneer using a rubbercup and diamond polishing paste

Fig. 10 Unsightly, porcelain-toothjunctions at the incisal overlap ofthe palatal surface veneers at UL1,UL2 and UL3 (21, 22 and 23). Thejunctions are clearly visible due tothe abrupt change in opticalcontrast and the straight finish line

-

PRACTICE

82 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 193 NO. 2 JULY 27 2002

the opposing tooth or the prepared tooth in theperiod between preparation and fit of theveneers. Space maintenance is best provided byadding composite resin to the palatal surface ofthe upper teeth to produce a stable occlusal stopbetween the upper and lower arches, rather thanrisking damage to the prepared enamel surfaceof the lower.

Posterior occlusal onlaysPorcelain occlusal onlays (sometimes termedshims) have the potential to offer an elegantand aesthetic means of reconstructing theocclusal surfaces of worn or broken-down teeth.However, despite the initial enthusiasm of someauthors37 the results with traditional aluminousor feldspathic porcelains have proved disap-pointing. We have experienced both debondingand fracture, especially when restorations areattached mainly to dentine, and subject to therigors of bruxism. It may be that one or more ofthe high strength ceramics would be suitable forthis purpose,38 but it is too early to make anyfirm recommendations.

CONCLUSIONSPorcelain veneers are a useful adjunct to thearmamentarium of the dentist to help in themanagement of aesthetic problems in patients,both young and old. Care needs to be taken dur-ing tooth preparation and particularly duringthe luting phase to ensure maximal results areobtained for the patient.

1. DPB. Dental Data Digest of Statistics. Dental Practice Board,1996.

2. DPB. Dental Data Digests of Statistics for 1997,1998,1999,2000 and 2001. Dental Practice Board, 2001.

3. Pincus C. Building mouth personality. Alpha Omega 1948;42: 163-166.

4. Horn H R. Porcelain veneers. Dental Clinics of North America1983; 27: 671-684.

5. Dunne S M, Millar B J. A longitudinal study of the clinicalperformance of porcelain veneers. Br Dent J 1993; 175: 317-321.

6. Guidelines. Restorative indications for porcelain veneerrestorations. In: Gregg T, editor. Faculty of Dental SurgeryNational Clinical Guidelines. London: Faculty of DentalSurgeons of Royal College of Surgeons of England, 1997.

7. Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G.Porcelain veneers: a review of the literature. J Dent 2000; 28:163-77.

8. Walls A W G, Murray J J, McCabe J F. Composite laminateveneers: a clinical study. J Oral Rehabil 1988; 15: 439-454.

9. Rucker L M R W, MacEntee M, Richardson A,. Porcelain andresin veneers clinically evaluated: 2-year results. J Am DentAssoc 1990; 121: 594-596.

10. Harley K E, Ibbetson R J. Anterior veneers for the adolescent

patient: 1. General indications and composite veneers. DentUpdate 1991; 18: 55-6, 58-9.

11. Welbury R R. A clinical study of a microfilled composite resinfor labial veneers. Int J Paed Dent 1991; 1: 9-15.

12. Clyde J, Gilmoure A. Porcelain veneers: a preliminary review.Br Dent J 1988; 164: 9-14.

13. Strassler H, Nathanson D. Clinical evaluation of etchedporcelain veneers over a period of 18-42 months. J AesthetDent 1989; 1: 21-28.

14. Nordbo H, Rygh-Thoresen N, Henaug T. Clinical performanceof porcelain laminate veneers without incisal overlapping: 3-year results. J Dent 1994; 22: 342-345.

15. Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B, Lambrechts P, Vuylsteke-Wauters M, Vanherle G. Five-year clinical performance ofporcelain veneers. Quintessence Int 1998; 29: 211-221.

16. Kihn P, Barnes D. The clinical evaluation of porcelain veneers:a 48-month clinical evaluation. J Am Dent Assoc 1998; 129:747-752.

17. Fradeani M. Six-year follow-up with Empress veneers. Int JPeriodont Rest Dent 1998; 18: 216-225.

18. Dumfahrt H, Schaffer H. Porcelain laminate veneers. Aretrospective evaluation after 1 to 10 years of service: PartIIClinical results. Int J Prosthodont 2000; 13: 9-18.

19. Christensen G, Christensen R. Clinical observations ofporcelain veneers. J Aesthet Dent 1991; 3: 174-179.

20. Walls A W. The use of adhesively retained all-porcelainveneers during the management of fractured and wornanterior teeth: Part 2. Clinical results after 5 years of follow-up. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 337-40.

21. Magne P, Kwon K R, Belser U C, Hodges J S, Douglas W H.Crack propensity of porcelain laminate veneers: A simulatedoperatory evaluation. J Prosthet Dent 1999; 81: 327-334.

22. Calamia J R. Materials and techniques for etched porcelainfacial veneers. Alpha Omega 1988; 81: 48-51.

23. Garber D. Traditional tooth preparation for porcelainlaminate veneers. Comp Cont Ed Dent 1991; 12: 316, 318,320, 322.

24. Harley K E, Ibbetson R. Anterior veneers for the adolescentpatient: 2 Porcelain veneers and conclusions. Dent Update1991; 18: 112-116.

25. Nattrass B R, Youngson C C, Patterson C J, Martin D M, RalphJ P. An in vitro assessment of tooth preparation for porcelainveneer restorations. J Dent 1995; 23: 165-170.

26. Hui K, Williams B, Davis E, Holt R. A comparative assessmentof the strengths of porcelain veneers for incisor teethdependent on their design characteristics. Br Dent J 1991;171: 51-55.

27. Meijering A C, Creugers N H, Roeters F J, Mulder J. Survival ofthree types of veneer restorations in a clinical trial: a 2.5-year interim evaluation. J Dent 1998; 26: 563-568.

28. Calamia J. Materials and techniques for etched porcelainfacial veneers. Alpha Omega 1988; 81: 48-51.

29. Sim C, Ibbetson R J. Comparison of fit of porcelain veneersfabricated using different techniques. Int J Prosthodont1993; 6: 36-42.

30. Raigrodski A J, Sadan A, Mendez A J. Use of a customizedrigid clear matrix for fabricating provisional veneers. J EsthetDent 1999; 11: 16-22.

31. Swift B, Walls A W, McCabe J F. Porcelain veneers: the effectsof contaminants and cleaning regimens on the bondstrength of porcelain to composite. Br Dent J 1995; 179:203-208.

32. Strang R, McCrossan J, Muirhead M, Richardson S. Thesetting of visible light cured resins beneath etched porcelainveneers. Br Dent J 1987; 163: 149-151.

33. Warren K. An investigation into the microhardness of a light-cured composite when cured through varying thicknesses ofporcelain. J Oral Rehabil 1990; 17: 327-334.

34. OKeefe K, Pease P, Herren H. Variables affecting the spectraltransmittance of porcelain through porcelain veneersamples. J Prosthet Dent 1991; 66: 434-438.

35. Linden J J, Swift E J, Jr., Boyer D B, Davis B K. Photo-activationof resin cements through porcelain veneers. J Dent Res 1991;70: 154-157.

36. Berrong J M, Weed R M, Schwartz I S. Color stability ofselected dual-cure composite resin cements. J Prosthodont1993; 2: 24-27.

37. Mabrito C, Roberts M. Porcelain onlays. Curr Opin CosmeticDent 1995: 1-8.

38. Denissen H, Dozic A, van der Zel J, van Waas M. Marginal fitand short-term clinical performance of porcelain-veneeredCICERO, CEREC, and Procera onlays. J Prosthet Dent 2000;84: 506-13.

Fig. 11 Here the incisal overlap hasbeen hidden. The palatal veneers onUR1 (11) and UL1 (21) have hadtheir incisal margins extended some2mm onto the buccal surface of thetooth with a gradual increase intranslucency of the porcelain toimprove colour transmission. Also,the finish line is serpentinous