V genes in primates from whole genome shotgun data · V genes in primates from whole genome shotgun...

Transcript of V genes in primates from whole genome shotgun data · V genes in primates from whole genome shotgun...

V genes in primates from whole genome shotgun data

David N. Olivieri1,2 and Francisco Gambon-Deza3

1 School of Computer Science, University of Vigo, Ourense 32004, Spain.2 Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge MA, 02142, USA.

3Servicio Gallego de Salud (SERGAS), Inmunologıa, Hospital do Meixoeiro, 36210 Vigo, [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected]

Abstract

The adaptive immune system uses V genes for antigen recognition. The evolutionary diversifica-tion and selection processes within and across species and orders are poorly understood. Here, westudied the amino acid (AA) sequences obtained of translated in-frame V exons of immunoglobu-lins (IG) and T cell receptors (TR) from 16 primate species whose genomes have been sequenced.Multi-species comparative analysis supports the hypothesis that V genes in the IG loci undergobirth/death processes, thereby permitting rapid adaptability over evolutionary time. We also showthat multiple cladistic groupings exist in the TRA (35 clades) and TRB (25 clades) V gene lociand that each primate species typically contributes at least one V gene to each of these clade. Theresults demonstrate that IG V genes and TR V genes have quite different evolutionary pathways;multiple duplications can explain the IG loci results, while co-evolutionary pressures can explainthe phylogenetic results, as seen in genes of the TR loci. We describe how each of the 35 V genesclades of the TRA locus and 25 clades of the TRB locus must have specific and necessary rolesfor the viability of the species.

Keywords: Immunologic Repertoire, Primate Evolution

1. Introduction

The adaptive immune system contains natural molecular recognition machinery that is able todistinguish self from non-self and defend the body against infections (Janeway Jr, 1992). Thismolecular recognition system consists of two molecular structures, immunoglobulins (IG) and Tlymphocyte receptors (TR). Immunoglobulins recognize antigen in soluble form and are com-posed of two types of molecular units, a heavy chain (IGH) and a light chain (either IGK or IGL).The recognition site is composed of the variable (V) domains present in the NH2-terminus of bothchains. The antigen binding site is composed of two V domains, one from each chain. Within theseprotein domains, zones have been described that interact with antigen (called the complementaritydetermining regions, CDR) and framework regions (FR). For IG, there are three CDR and threeFR regions within each V domain. The interaction site with antigen consists of six CDR supportedby six FR regions. The TR recognize antigen that are presented by the molecules of the major his-tocompatibility complex (MHC), as antigen-MHC molecular complexes. Despite this substantialdifference between TR and IG with respect to the mechanism of antigen recognition, both possess

Preprint submitted to Elsevier July 7, 2014

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

similar structures. In particular, each have two chains possessing V domains at the site within themolecule that is responsible for antigen-MHC recognition. These domains are similar to those inIG, containing three FR regions and three CDR per chain (Janeway et al., 2001).

Because the amino acid (AA) sequences of the IG and TR V domains are so similar, it has beenhypothesized that all such sequences present today were derived from an ancestral gene (Hughes,1994). This ancestral gene was assigned to immune recognition in the epoch coinciding with theorigin of vertebrates. Evidence comes from the present-day IG and TR sequences in fish, whosestructures have been maintained in all extant vertebrates (Ghaffari & Lobb, 1991).

Genes of the V domains are distributed across seven unique loci. The genes from three ofthese loci are used to construct IG chains, while the other four loci contain genes that encode TRchains (Janeway et al., 2005; Brack et al., 1978; Tonegawa, 1983; Davis & Bjorkman, 1988). Theantigen recognition repertoire that an organism possesses is dictated by the total available set ofthese genes. These genes have two exons, one for the peptide leader and the other that encodesmost of the V domain (V in-frame exon) (The Immunoglobulin FactsBook (Lefranc & Lefranc,2001a); The T cell receptor FactsBook (Lefranc & Lefranc, 2001b); (Lefranc, 2014). Within theV exon, there are coding sequences for the first two complementarity determining region (CDR1and CDR2) for antigen recognition and the three framework regions (FR1, FR2, and FR3) (theinternational ImMunoGeneTics information system, http://www.imgt.org (Lefranc et al., 2009), IMGT/GENE-DB (Giudicelli & Lefranc, 2004). A third complementarity determining region(CDR3) is generated through a gene rearrangement process, called VDJ recombination, wherebyV exons are moved from their location in order to join with other gene segments, called D and J.This process is somatic and only occurs within lymphoid cells (Tonegawa, 1983).

The number of V exons for IG and TR is highly variable across different species, especiallywith respect to the IG loci. For example, there are approximately 600 IGHV genes for the microbat(Mioitis lucifugus), while for other mammals, such as those living in aquatic environments (e.g.seals, dolphins and walruses) have much fewer IGHV genes (Olivieri et al., 2013). From the Vexon sequence data available at http://vgenerepertoire.org, the number of genes in the TRBV locusbetween species is approximately constant, while there is a large variance in the number of TRAVgenes, particularly pronounced in the Bovine species of the Laurasiatheria. The causes for thisvariability amongst species is presently unknown.

In this paper, we describe organizational and phylogenetic relationships of the amino acid (AA)sequences derived from the V exons of the order Primates uncovered from whole genome shot-gun (WGS) datasets. In particular, we studied 16 representative Primate species whose genomeshave been sequenced in order to identify evolutionary patterns that could explain the present-daygenomic repertoire of V genes. Our results show that in the IG loci, duplications and losses of Vexons are common, while in the TRAV and TRBV loci, complex selection mechanisms may beresponsible in order to conserve V exons between species.

2. Material y methods

For these studies, we used genome data from whole genome shotgun (WGS) assemblies ofspecies that are publicly available at the NCBI. For the majority of these species, the V geneshave not been annotated or only partial annotations have been performed in specific loci, (IMGT

2

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

Repertoire, http://www.imgt.org). All curated genes were entered in IMGT/GENE-DB (Giudicelliet al., 2005) and IMGT gene nomenclature has been provided to Gene at NCBI (Lefranc, 2014).We used our VgenExtractor bioinformatics tool [http://vgenerepertoire.org/downloads/] (Olivieriet al., 2013) to identify the in-frame V exon sequences from an analysis of these genome files bysearching for well established signatures and motifs. Our software algorithm searches and extractsin-frame V exon sequences based upon known motifs. In particular, the algorithm scans largegenome files and extracts candidate V exon sequences. These V exon sequences are delimited atthe nucleotide level by an acceptor splice a the 5′ end and at the 3′ end by the V recombinationsignal (V-RS). These V exon (and its translation) includes the second part of the signal peptide(L-PART2) and the V-REGION (IMGT-ONTOLOGY 2012, for a detailed description (Giudicelli& Lefranc, 2012)). The IMGT unique numbering starts at the beginning of the V-REGION. Theexons fulfill specific criteria: they are flanked in 3′ by the V recombination signal (V-RS), theyhave a reading frame without stop codon, the length is at least 280 bp long, and they containtwo canonical cysteines and a tryptophan at specific positions (1st-CYS 23 and 2nd-CYS 104,CONSERVED-TRP 41 according to the IMGT unique numbering ((Lefranc et al., 2003), (Lefranc,2011)).

Since the VgenExtractor algorithm scans entire genomes by matching specific motif patternsalong the exon sequence, a fraction of the extracted sequences can fulfill the conditions of ouralgorithm for being functional V-genes, yet are structurally very different. Such sequences areeasily discarded with a Blastp comparison against a V-gene consensus sequence. We found thatan ample threshold (evalue=1e-15) is sufficient for eliminating all sequences that are not V genes.

The VgenExtractor algorithm can be modified to identify pseudogenes by relaxing the motiffilters or by relaxing the condition of stop-codon translation. Nonetheless, this would only uncovera fraction of the complete set of pseudogenes that could otherwise fulfill different criteria. Acomplete set of pseudogenes would remain elusive due to random alterations of sequences overevolutionary history. Thus, we limited all further study to specifically targeted functional genes, orthose exons that possess the requirements seen in all V genes sequences annotated to date ( IMGTRepertoire, http://www.imgt.org).

Once we identified functional V exons, we analyzed the set of translated amino acid (AA)sequences with a pipeline that we implemented within the Galaxy toolset (https://usegalaxy.org/).The steps of the workflow are as follows. First, we performed multiple BLAST alignment ofthe AA sequences against V exon consensus sequences obtained from previously annotated Vgenes (IMGT Repertoire, http://www.imgt.org). Those sequences with a BLAST similarity score> 0.001 were retained, while other sequences were discarded. From the resulting AA translatedV exon sequences, we performed multiple alignment with ClustalO(Sievers & Higgins, 2014)and phylogenetic comparison studies using SEAVIEW (Gouy et al., 2010). For the tree construc-tion, we used a maximum likelihood algorithm and the LG matrix. Finally, we used the MEGA5(Tamura et al., 2011) and FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) to produce tree graph-ics.

We classified the V exon sequences into one of the 7 loci (IGHV, IGKV, IGLV, TRAV, TRBV,TRDV and TRGV) by obtaining a heuristic score based upon a BLASTP against the NCBI NRprotein database. The score is computed by mining the text description from protein hits that havea similarity score above a predetermined threshold in order to obtain a relevant word frequency

3

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

indicative of exon type. For each protein description, the word frequency is weighted by theBLAST similarity score, so that the most similar protein descriptions contribute more to the finalloci classification.

We developed a python analysis script (called Trozos, which can be freely downloaded athttp://vgenextractor.org/downloads/), which we used for extracting the CDR and FR sequencesfrom the AA translated V exon. First, we studied the V exon amino acid sequences and couldidentify the presence of the two canonical cysteines and the presence of tryptophan, W41 (IMGTunique numbering (Lefranc et al., 2003; Lefranc, 2011)). Between each V exon, the number ofamino acids in the CDRs varies, however we used the standardized IMGT naming/nomenclatureto define the regions. In particular, CDR1 contains six amino acids and begins at the position ofthe first cysteine (ie., + 3 to cysteine + 10). The CDR2 is defined as the sequence located betweenW41 + 15 and W41 + 22. The framework sequence regions are located between the CDRs.Stretches of sequences, which we indicate by (i), refer to sequences we obtained computationally.For a particular set of sequences, some parameter adjustment in the Trozos algorithm is necessaryfor consistency, validating the final result against a visualization of the sequence alignment. For adetailed study of the alignments and a study of the conservation sites, we used the software Jalview(Waterhouse et al., 2009).

We obtained the V exon sequences of 16 primates whose WGS sequences are available at theNCBI. The primates included in our study and their corresponding abbreviated accession numbersare the following: the Lemuriformes: Daubentonia madagascariensis (AGTM01), Otolemur gar-nettii (AAQR03), Microcebus murinus (AAHY01), the Tarsiformes: Tarsius syrichta (ABRT01),the NewWorldMonkeys: Callithrix jacchus (ACFV01), Saimiri boliviensis (AGCE01), the OldWorld Monkeys: Macaca mulatta (AANU01), Macaca fascicularis (CAEC01), Chlorocebussabaeus (AQIB01), Papio anubis (AHZZ01), the Hominids: Nomascus leucogenys (ADFV01),Pongo abelii (ABGA01), Gorilla gorilla (CABD02), Pan paniscus (AJFE01), Pan troglodytes(AACZ03), and Homo sapiens (AADD01). Details of these WGS data sets are provided in Sup-plementary Table 1.

3. Results

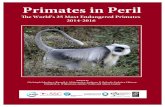

Previous work have described variations in the number of V genes between species (Guo et al.,2011; Niku et al., 2012). Likewise, we recently demonstrated the presence of distinct evolutionaryprocesses between the IG and TR V genes (Olivieri et al., 2013). Nonetheless, the origin of thisvariation is still unknown. In order to understand the reason for this V gene number variation,we compared these genes amongst species of specific mammalian orders and families. Here wedescribe such a comparative study in primates. In particular, we studied the V exon sequencesfrom the 16 primate species represented in Figure 1. We extracted the V exon sequences fromWGS public datasets, listed in Table 1. We carried out studies in the five major simian branches.Nonetheless, there is a greater representation (six species) from the hominid group simply basedupon the maturity of available WGS data.

3.1. Immunoglobulin GenesThe IGHV locus has been described in many vertebrate species (Berman et al., 1988; Miller

et al., 1998; Deza et al., 2009; Gambon-Deza et al., 2010). The joint study of all species with all4

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

Papio anubis

Macaca fascicularis

Chlorocebus sabaeus

Macaca mulatta

Pan paniscus

Pan troglodytes

Homo sapiens

Gorilla gorilla

Pongo abelii

Nomascus leucogenys

Saimiri boliviensis

Callithrix jacchus

Tarsius syrichta

Daubentonia madagascariensis

Otolemur garnettii

Microcebus murinus

0204060 Mya.

Eocene Oligocene Miocene toHolocene

New World monkeys

Old World monkeys

Lemuriformes - Prosimians

Tarsiiformes

Hominides

Figure 1: Phylogenetic tree of the primates included in the study. The tree was constructed from recent molecularphylogenetic data provided in (Perelman et al., 2011).

5

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

Table 1: Distribution of V-genes amongst the IG and TR loci.

Specie ighv igkv iglv trav trbv trgv trdv all

LemuriformesD. madagascariensis 4 10 10 40 17 2 5 88O. garnettii 9 49 42 69 31 5 13 218M. murinus 40 26 52 38 30 3 3 191TarsiiformesT. syrichta 38 50 26 40 12 3 6 175NewWorld monkeysC. jacchus 75 24 27 30 43 3 6 208S. boliviensis 27 29 14 37 36 4 2 159OldWorld monkeysM. mulatta 63 65 51 45 57 5 6 292M. fascicularis 67 66 48 44 56 4 7 292C. sabaeus 64 63 44 36 53 3 7 270P. anubis 68 78 47 38 58 5 6 300HominidsN. leucogenys 28 33 20 42 37 4 5 169P. abelii 72 42 31 42 62 4 9 262G. gorilla 44 30 22 41 49 3 5 194P. paniscus 30 26 28 36 51 6 6 183P. troglodytes 53 41 27 52 55 5 4 237H. sapiens 44 46 33 42 49 3 6 193

V exon sequences has identified three evolutionary clans (IMGT (Lefranc, 2001)). The clans aredefined by specific sequences in the Framework 1 (IMGT-FR1) regions and Framework 3 (IMGT-FR3) regions, which are influential in antigen recognition functionality (Kirkham et al., 1992). TheIGKV and IGKL loci are less well studied and there are no published work that clearly indicatethe existence of clans in these loci, as is the case in the IGHV locus.

From the 16 species of primates studied (Table 1), we obtained a total of 701 IGHV exonssequences. Two species, (D. madagascariensis and O. garnetti), have markedly fewer IGHVgenes than the average, while the rest of the primates have an average of between 30 to 60 IGHVgenes in this locus.

To compare the V exon sequences in extant primate species, we carried out multi-species phy-logenetic analysis by first aligning the AA translated sequences with clustalO (Sievers & Higgins,2014) and then performing tree construction with FastTree (Price et al., 2010) (using maximumlikelihood and WAG matrices). Subsequently, we used Figtree or MEGA5 (Tamura et al., 2011)for visualization. The resulting phylogenetic trees show the presence of three major clades (ClanI, II and III) which have already been described in vertebrates (Kirkham et al., 1992; Lefranc &Lefranc, 2001a; Giudicelli & Lefranc, 1999) (see the IMGT clans http://www.imgt.org) (Figure 2).Additionally, due to the large number of sequences in this study, we can discern the presence of

6

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

subclades within each of the defined IGHV locus clans. Thus, from the primate V exon sequencesfound within Clan I, the 182 sequences form three subclades (A-29 Seq, B-22 Seq, and C-131Seq), the 139 sequences in Clan II form two subclades (A-41 Seq and B-98 Seq), and the 380sequence in Clan III 380 can be grouped into three subclades (A-104 Seq, B-94 Seq, and C-182Seq).

Clues about the origins of V gene sequences can be gained by observing the distribution ofthe primates amongst the clades. While Old World monkeys and Hominids have sequences in allclades, New World Monkeys have no sequences within clade III-B and Tassiforms and Lemureshave no sequences within the IGHV clade II (Table 2). We also observe that species typically haveseveral V genes per clade, as seen in Figure 2), which may be due to recent duplication events.

Table 2: Distribution of IGHV exons across the clans.Clan I Clan II Clan III

Specie a b c a b a b cLemuriformesD. madagasca. 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0O. garnettii 2 0 0 0 0 2 4 1M. murinus 0 0 9 0 0 5 10 13TarsiiformesT. syrichta 2 0 16 0 0 5 8 8NewWorld monkeysC. jacchus 7 2 18 1 2 3 0 40S. boliviensis 2 2 8 2 1 2 0 10OldWorld monkeysM. mulatta 2 1 4 4 14 14 9 15M. fascicularis 2 2 6 3 15 13 9 17C. sabaeus 2 0 10 1 7 11 8 8P. anubis 2 3 9 4 18 12 7 13HumanoidsN. leucogenys 1 2 6 2 4 4 3 6P. abelii 3 3 9 6 18 13 10 10G. gorilla 1 2 9 3 6 6 6 11P. paniscus 1 1 7 3 2 3 5 8P. troglodytes 1 2 8 7 8 6 8 12H. sapiens 1 2 10 5 3 5 7 11

From each of the clades, we determined the 90% consensus sequences. These sequences arerepresented in the lower part of Figure 2, showing sequence conservation in the framework regionsand the existence of motifs that can be used to define separate clades in these regions. As expected,the least conserved regions correspond to those of the CDRs.

We found similar results in the IG light chain V genes. In particular, we found that across

7

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

0.2

Clan I

Clan II

Clan III

A

B

A

B

C

A

B

C

FR1-IMGT CDR1-IMGT FR2-IMGT CDR2-IMGT FR3-IMGT CDR3-IMGT

A B BC C C' C'C" C" D E F FG

1 10 15 16 23 26 27 38 3941 46 47 55 56 65 66 74 75 84 85 89 96 97 104 105 |........|....| |......|..| |..........| |.|....| |.......| |........| |.......| |........| |...|......| |......| |...

——————————————> ——————————> ———————> ————————> ————————> —————————> ———————————> ———————>

Clan IIA V*S QVTLKESGP*LVKP T*TLTLTCT*S GFSLS **G** **WIRQPP *KALEWLA* I*** D* K*YS*SLK* RL*I*KDTSK *QVVLTMTNMDP VDTATYYC A**Clan IIB VLVLS QV*L***GP*LVKP **TL*LTC*** G*S*S ***** **WIRQ*P GK*LEW*** I*** S*** **Y**SLK* R*T*S*DTSK *Q**L******* *DTA*YYC A**

Clan IA VCA **QLVQS*AEVK*P GESL*ISC**S GYSF ***W I*WVRQ*P GKGLE**G* I*** DS* T*Y*PSFQG **TISAD*S* *T**LQW*SLKA SD*A*YYC A*Clan IB ***QV QLVQSG*E*K*PG* SVKVSCKASGY *FT *Y* *NW**QA* GQ*LEWMGW *NT* *G* P*YAQGF** *F*FS*DTS* ST*YLQISSLK* ED*A*YYC *RClan IC **S*V QLVQSG*EV**PG* SVK*SCK*SGY TF* *** **WV*Q** **GLEW*G* ***MP **G* **Y*QKFQ* RVT*T*D*S* *T*YMEL*SLR* ED*A*YYC **

Clan IIIA VQCEV QL*E*GGGLVQPGG SLRLSC**SGF TF* *** M*WV*QAP GKG*EWVG* *R*KA *G* **YA*SVKG RFTISRDDSK S***LQM**L*T EDTAVYYC *RClan IIIB VQCEV QLVESGGGLVQPGG SL*LSCAASGF TFS *** M*WVRQA* GKGLEWV** ***K** *** **YA**VKG RFTISRDDSK N**YLQM*SLKT EDTAVYYC **Clan IIIC RVQC*V QLVESGGGL**PGG SLRLSC*ASSG FTF* *** M*W*RQAP GKGLEWV** I**** *** **Y*DSVKG RFTISR*N*K N*L*LQMNSL** EDTA*YYC **

Figure 2: The phylogenetic trees of the AA translated sequences from IGHV exons from 16 primates species. V exonsequences are obtained from whole genome shotgun (WGS) datasets using the Vgenextractor algorithm. Alignmentof the amino acid sequences was performed with clustalO, tree construction with FastTree using the WAG matrix, andvisualization with Figtree. (Left:) the tree of all IGHV exon sequences; (Right:) a detailed view of the subclade, ClanI-C, showing the names of constituent species. The leaves of the taxon, P. albelii, are highlighted in order to easilyillustrate the distribution of a particular species within the subclade. In the bottom part of the figure, the consensussequences of each clade are given. The amino acids that are found in more than 90 % of the sequences are marked bytheir letter, while the variable regions are represented by an asterisk (”*”) .

8

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

the primate species, there was wide variability in number IGKV genes (coding for the κ, or IGK,chains), ranging between 10 and 66 V genes. With respect to the number of IGLV (coding for theλ, or IGL, chain), we found a similar variability, between 10 and 51 V genes. Also, some variationexists between the number ratios IGKV/IGLV within each of the primate species studied. Theseratios are of interest, because it is well established that in humans and mice, there is more IGKthan IGL both in serum as well as with respect to the number of genes (ie., in humans, there are46 IGKV genes and 33 IGLV in humans, while in serum there is approximately 70% IGK chainantibodies as compared to 30% IGL antibody chains). In all primate species, we found a largernumber of IGKV compared to IGLV genes, with only two exception, in prosimians, in which theratio is unity, and in the case of the M. murinus for which the ratio is inverted with respect to otherprimates.

From the 16 primate species in our study, we obtained a total of 629 IGKV exon sequences.The resulting phylogenetic tree from the corresponding AA translated sequences indicates theexistence of two large (or principal) clades and two smaller clades having a lower number ofsequences (Clade I -210 sequences- and II-419 sequences- seen in Figure 3). The two principalclades have representative sequences from all the primates studied, except for prosimians, whichdo not have sequences in clade IIA.

We obtained a total of 522 IGLV exon sequences from the 16 primate species studied. Thesesequences group into five principal clades, each having representatives from all species. This cladestructure may be significant, since it corresponds to the five clades in IGLV locus we described ina previous publication (Olivieri et al., 2014). Indeed, this structural conservation seen in the IGLVclades may have functional significance, because it is also maintained in distant reptiles species.

From sequence alignments within each clade, we deduced motifs from the 90% consensus se-quences (those sequences whose AA positions possess 90% similarity) given in Figure 3 (bottom).The AA in the sequences are present in nearly all sequences, while the ”*” represents sites of vari-ability. Similar to what we showed for the IGHV exons, the clades are defined by sequence motifspresent in the frameworks FR1 and FR3. The sequences in the FR2 region from different cladesare similar, while variability can be detected in regions that contain the CDRs.

3.2. The TR V genesWe used our gene calling algorithm, Vgenextractor, to obtain the TRV exon sequences and

study the AA sequences of the V exons from the TRA and TRB loci in 16 different primate species.In particular, we obtained 670 TRAV exon sequences and found that the number of TRAV exonsranges between 30 (in C. jacchus) and 69 (in O. garnettii). From a phylogenetic study of theAA sequences of the TRAV exons, six major clades can be identified. Also, each of these cladeshave several subclades. From a detailed examination of these subclades, at least one sequencefrom each species is found to be common, indicating that these are clades of orthologous genes.Figure 3 shows phylogenetic tree of the AA translated sequences from the TRAV exon sequences,showing a natural grouping into 35 subclades. Most of these subclades have sequences for at leasttwelve species. In the figure, we zoomed in on specific subclades to expose the taxa to which theconstituent sequences originate.

Table 5 lists the V exon sequence distribution for each species per clade. In general, eachspecies is represented within each of the 35 clades with one or two genes. There are clades where

9

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

Table 3: Distribution of V exons from IGKV and IGLV across clades and species.IGKV IGLV

Specie I IIA IIB IIC mI mII I II III IV VLemuriformesD. madagasca. 2 0 3 3 1 1 3 4 2 1 0O. garnettii 17 0 2 25 2 1 5 13 4 16 4M. murinus 15 0 2 8 0 1 13 24 3 5 7TarsiiformesT. syrichta 15 3 1 27 0 3 6 8 5 4 3NewWorld monkeysC. jacchus 8 2 4 8 1 0 13 10 1 1 2S. boliviensis 11 2 4 10 2 0 4 3 3 3 1OldWorld monkeysM. mulatta 19 9 6 29 1 1 14 22 6 5 4M. fascicularis 20 9 6 28 1 1 10 22 6 5 5C. sabaeus 21 5 3 15 1 0 12 16 6 3 7P. anubis 24 14 6 32 1 1 12 20 6 4 5HumanoidsN. leucogenys 15 2 1 14 1 0 6 11 0 1 2P. abelii 9 8 4 20 1 0 10 14 2 1 4G. gorilla 5 3 3 17 1 0 9 9 2 1 1P. paniscus 9 3 2 12 0 0 8 11 3 3 3P. troglodytes 6 4 3 27 1 0 10 11 1 3 2H. sapiens 1 2 4 7 1 0 10 14 3 2 4

10

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

0.2

IGLVIGKV

I

II

I

II

III

IV

V

0.2

FR1-IMGT CDR1-IMGT FR2-IMGT CDR2-IMGT FR3-IMGT CDR3-IMGT (1-26) (27-38) (39-55) (56-65) (66-104) (105-117)

A B BC C C' C'C" C" D E F FG (1-15) (16-26) (27-38) (39-46) (47-55) (56-65) (66-74) (75-84) (85-96) (97-104)

——————————————> ——————————> ———————> ————————> ————————> —————————> ———————————> ———————> 1 10 15 16 23 26 27 38 3941 46 47 55 56 65 66 74 75 84 85 89 96 97 104 105 11112 |........|....| |......|..| |..........| |.|....| |.......| |........| |.......| |........| |...|......| |......| |.....||

Clade I **G D*VMTQ*PL*L**T* G***SISCR*S QSL**S****TY L*W**QKP GQ*P**LIY **.......S *R*SGVP.D RFSGSG*..G TDFTLKIS*V*A ED*GVYYC *Q****PClade IIA SDT*G **V*TQSPATLS*SP GE**T*SCRAS QSV*.....S** LAWYQQKP GQAP*LLI* *A.......S *RATGIP.* RFSGSGS..G T*FTLTISSLEP ED**VY*C *******Clade IIB *** ****TQSP******* *****I*C*A* ***SI**G**** **WYQQ*P ***P***** **.......* ****G**.* RF*G***..G T*F**TI***** *D*A*Y*C *Q****PClade IIC **C *IQMTQSPS*LSAS* GD*VTI*C*AS Q*I......*** L*WYQQKP G**P**LIY *A.......S *L**G*P.S RFSGSGS..G T***LTI**LQ* ED*A*YYC ******PClade minor I *** ****TQSP**LA*** G*R*T**CK** *S*L**S**K** **W*QQ*P GQ*PK**** **.......S *R*SGVP.* R*SG**S..G TDFTLTIS**** *DV**YYC ****S*PClade minor II V*G D****Q*PASL*A** GE**SISC*AS A*V......HGE *SW*RIKL GQ*LEPLIS HV.......T TLAPGVP.* *YS***S..G *SY*FSIS*L*P GDSG*YYC *HD*GW*

Clade I S** ***LTQ***.VSV** GQ***ITC*G* ***......*** **W*QQK* *Q*PVL*IY **.......* *RPSGIP.* RFS*S*S..G ****LTI***** *DEADYYC ***D*****Clade II S*A ****TQ**S.*S*** ****T*SC*** S****...**** V*WYQQ** G**P****Y **.......* *RPSG**.* RFSGS**SS* **ASL*I*GL** EDEADYYC *********Clade III **S Q*VV*QE*S.****P G*TVTLTC**S *G*V*...**** **W*QQ** *Q*P**LI* *T.......* ******P.* *FSGS**..G *KAALT**GAQ* *DE**YYC *L*****IAClade IV *** ***LTQ**S.ASAS* G*S**LTCTL* S**S.....*Y* **W*QQ** ***P***M* ****G..*V* **G*GIP.D *F*GS*S..G **RYLTI*N*Q* *DEA*Y*C ********Clade V SLS Q***TQP*S.*SA** GAS**L*CT** *****...**** **W*QQKP G*PPRYLL* ***D...S*K **GSGVP.* R*SGS*D*** N*G*L**S*LQ* EDEADYYC *****S*

A

B

C

minor Clade I

minor Clade II

KAPPA

LAMBDA

Figure 3: The phylogenetic trees of the AA translated sequences from (IGKV -left- and IGLV -right-) exons from 16primates species. V exon sequences are obtained from whole genome shotgun (WGS) datasets using the Vgenextractoralgorithm. Alignment of the amino acid sequences was performed with clustalO, tree construction with FastTreeusing the WAG matrix, and visualization with Figtree. The root of the major clades are marked with Roman numerals.Significant subclades in the tree are identified to the right. In the bottom part of the figure, the consensus sequences ofeach clade are given. The amino acids that are found in more than 90 % of the sequences are marked by their letter,while the variable regions are represented by an asterisk (”*”).

11

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

the V exon sequences of some species are absent, however this could be because we did not detectthe V exon with our gene calling algorithm. In previous publications, we show that our algorithmdetects approximately 95% of V exon sequences (Olivieri et al., 2013).

Similar to the method we used in the IG loci, we determined the 90% consensus sequencesfor each of the 35 clades for V exons in the TRA locus. Clear differences can be seen betweensequences from different clades and conservation exist within the same clade. Table 4) shows thevariability that exists within each of the V exon sequence regions (FR1, CDR1, FR2, CDR2 andFR3). Within each of these five regions, we determined the fraction of the number of locationshaving variability (with positions shown as ’*’) to the total number of positions including theamino acid conserved sites. As expected, the CDR regions are those that exhibit the most AA sitevariability, however CDR2 is less variable than the CDR1, suggesting an underlying conservationprocesses. When compared against the framework regions, the CDR2 region is slightly morevariable.

Table 4: Percentage of AA sites along the translated V exon primate sequences, derived from the alignments providedin Figures 4 and 6.

Locus FR1 CDR1 FR2 CDR2 FR3TRAV 32% 54% 30% 38% 30%TRBV 34% 43% 27% 59% 31%IGHV 24% 54% 31% 68% 29%IGKV 44% 56% 35% 50% 32%IGLV 50% 85% 51% 83% 39%

For TRBV exon sequences, we obtained similar results with respect to clade grouping as wefound for the TRA locus. In particular, we obtained 696 TRBV exon sequences and we can deduce25 clades from a tree analysis. As in the previous cases discussed, we found that all clades containV sequences from the majority of primate species. Table 6 shows the distribution of AA translatedTRBV exon sequences across the different subclades for species. As can be seen, each speciecontributes one or more sequences per clade. Figure 6 shows the phylogenetic tree of all the AAtranslated TRBV exon sequences, together with the alignment within each clade to obtain the 90 %consensus sequences. As before, we studied the variability between the canonical IMGT definedregions. The results are shown in Table 4, where it can be seen that the greatest variability isdetected within the CDRs. Also, in amongst the TRAV genes, the sequences of CDR1 have lowervariability than those of CDR2.

The phylogenetic results from the TRBV and TRAV loci show that V exons sequences existthat are maintained throughout evolution across primate species, since each species contributesone such gene to the subclades of the tree. To confirm these results and to study which parts of thesequences are involved in the process of selection, we studied independently the framework andCDR sequences separately from each V exon sequence. To separate the four separate the FR1,FR2, FR3, and the CDRs from the AA translated V exon sequences, we developed a python utilityprogram, called Trozos.py. Three sequences correspond to framework regions FR1, FR2 and FR3,while the fourth sequences is constructed by combining the two sequences from CDR1 and CDR2.

12

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

29

0.4

101112

1314

15

16

1718

1920

21

2223

2425

2627

2829

303132

3334

35

21

29

0.4

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

TRAV

12

34

56

7

8

9

Vs349|Homo_sap

Vs295|Pan_panis

Vs579|Pong

Vs123|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs970|Otolemur_garnett

Vs531|Macaca_fascicularis|t

Vs418|Papio

Vs345|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs748|Daubentonia_mad

Vs229|Daubentonia_madaga

Vs652|Callithrix_jacchus

Vs503|Nomascus_leucogeny

Vs301|Pan_

Vs724|Pongo_ab

Vs904|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|tra

Vs730|Pongo_ab

Vs126|Gorill

Vs322|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs395|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs1065|Otolemur_garnettii|tr

Vs65|Daubentonia_madagascariensis|trav

Vs289|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs214|Tarsius_syrichta|t

Vs326|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs125|Gorilla_go

Vs116|Gorilla_go

Vs727|Microcebus_murinus|

Vs300|Pan_panis

Vs573|Saim

Vs915|Chloroceb

Vs973|Otolemur_garnett

Vs113|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs1042|Otolemur_garnettii|tr

Vs339|Homo_sapiens|tra

Vs357|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs586|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs663|Daubentonia_madaga

Vs660|Daubenton

Vs386|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs527|Macaca_fa

Vs638|Callith

Vs506|Noma

Vs353|Homo_sap

Vs496|Nomascus

Vs969|Otolemur_

Vs517|Macaca_fascicula

Vs380|Pan_troglodytes|t

Vs324|Maca

Vs316|Macaca_m

Vs309|Macaca_mulatta|t

Vs521|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs572|Saimiri_bo

Vs492|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs534|Maca

Vs392|Pan_troglo

Vs298|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs922|Chloroceb

Vs397|Pan_troglo

Vs907|Chlorocebus_sab

Vs558|Papio_anu

Vs766|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs524|Macaca_fa

Vs244|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs232|Daubentonia_madaga

Vs500|Nomascus

Vs1045|Otolemur_garnettii|tr

Vs505|Nomascus

Vs353|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs533|Macaca_fa

Vs580|Saimiri_bo

Vs520|Daubenton

Vs763|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs1029|Otolemur_garnettii|tr

Vs360|Homo

Vs923|Chlor

Vs727|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs536|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs359|Homo_sap

Vs665|Tarsius_sy

Vs911|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs586|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs964|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs323|Macaca_m

Vs420|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs107|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs582|Saimiri_boliviensi

Vs283|Pan_paniscus|tra

Vs417|Papio_anu

Vs919|Chlorocebus_sabaeu

Vs398|Pan_

Vs679|Tarsius_sy

Vs575|Saimiri_bo

Vs486|Nomascus_leuco

Vs465|Papio_anu

Vs469|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs293|Microcebu

Vs608|Pan_

Vs313|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs650|Callithrix_jacchus|trav

Vs341|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs285|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs1080|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs346|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs584|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs1030|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs562|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs282|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs375|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs584|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs56|Daubentonia_madagascariensis|trav

Vs305|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs577|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs337|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs390|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs296|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs525|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs118|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs283|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs539|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs364|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs1043|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs521|Daubentonia_madagascariensis|trav

Vs556|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs329|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs306|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs977|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs382|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs133|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs132|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs292|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs524|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs205|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs578|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs388|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs913|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs559|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs106|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs966|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs393|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs764|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs317|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs363|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs467|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs463|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs288|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs555|Daubentonia_madagascariensis|trav

Vs57|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs626|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs311|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs228|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs307|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs266|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs554|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs516|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs1068|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs917|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs402|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs177|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs409|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs1026|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs906|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs488|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs529|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs1015|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs285|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs379|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs895|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs978|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs485|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs494|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs920|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs20|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs1105|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs1028|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs329|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs128|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs525|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs635|Callithrix_jacchus|trav

Vs555|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs240|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs1104|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs909|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs130|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs320|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs903|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs47|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs46|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs293|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs355|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs364|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs1163|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs237|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs515|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs144|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs347|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs511|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs725|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs143|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs501|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs109|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs338|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs494|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs216|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs723|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs764|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs376|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs378|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs765|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs105|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs653|Callithrix_jacchus|trav

Vs498|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs176|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs351|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs894|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs211|Daubentonia_madagascariensis|trav

Vs519|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs644|Callithrix_jacchus|trav

Vs121|Gorilla_gorilla|trav0.3

Vs488|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs129|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs343|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs132|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs736|Daubentonia_madagascarien

Vs1033|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs379|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs111|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs422|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs304|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs1025|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs700|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs36|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs538|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs514|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs625|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs526|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs8|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs527|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs1103|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs963|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs531|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs367|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs48|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs836|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs405|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs622|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs896|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs423|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs1040|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs363|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs384|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs135|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs1071|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs1027|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs558|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs1101|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs365|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs637|Callithrix_jacchus|trav

Vs1107|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs362|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs146|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs627|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs583|Pongo_abelii|trav

Vs550|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs461|Daubentonia_madagascariens

Vs553|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs523|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs131|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs100|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs403|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs367|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs1082|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs140|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs347|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs306|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs1016|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs552|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs563|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs1067|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

Vs401|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs287|Pan_paniscus|trav

Vs107|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs490|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs1097|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs145|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs698|Daubentonia_madagascarien

Vs134|Papio_anubis|trav

Vs902|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs888|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs239|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs678|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs623|Callithrix_jacchus|trav

Vs391|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs208|Tarsius_syrichta|trav

Vs430|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs49|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs533|Daubentonia_madagascarien

Vs540|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs557|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs628|Callithrix_jacchus|trav

Vs142|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs414|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs374|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs892|Chlorocebus_sabaeus|trav

Vs328|Macaca_mulatta|trav

Vs561|Saimiri_boliviensis|trav

Vs133|Gorilla_gorilla|trav

Vs557|Macaca_fascicularis|trav

Vs512|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs377|Homo_sapiens|trav

Vs365|Pan_troglodytes|trav

Vs234|Daubentonia_madagascarien

Vs92|Daubentonia_madagascariensis|trav

Vs93|Daubentonia_madagascariensis|trav

Vs636|Callithrix_jacchus|trav

Vs345|Microcebus_murinus|trav

Vs510|Nomascus_leucogenys|trav

Vs1069|Otolemur_garnettii|trav

FR1-IMGT CDR1-IMGT FR2-IMGT CDR2-IMGT FR3-IMGT CDR3-IMGT

A B BC C C' C'C" C" D E F FG

(1-15) (16-26) (27-38) (39-46) (47-55) (56-65) (66-74) (75-84) (85-96) (97-104) ——————————————> ——————————> ———————> ————————> ————————> —————————> ———————————> ———————>

(1-26) (27-38) (39-55) (56-65) (66-104) (105-117)

1 10 15 16 23 26 27 38 3941 46 47 55 56 65 66 74 75 84 85 89 96 97 104 105 |........|....| |......|..| |..........| |.|....| |.......| |........| |.......| |........| |...|......| |......| |.....

Clade 1 GT* SNSVKQ.T*Q***SE GASVTMNCT** **G......YPT *FWYV*YP *KPLQ*LQ* E........T MEN.....S KNFG**NIKD KNSP**K*SV*V SDSA*YYC LL*DTVL*Clade 2 *** GD*VTQTEG*VTL*E *****LNCTYQ **Y*.....**F *FWYVQ** *K*P*LLLK SSSE...*Q* ***.....* GF*A***KSD SSFHL*K*S*Q* SDSAVYYC ***Clade 3 G** GDSV*QTEG**LLSE **SL*VNCSYE ***......YP* L*WYVQYP G*G**LLLK A*K*N..D** *SN.....K *FEA*Y**ET TSFHL*K*SV*E SDSAVY*C ALSClade 4 RT* G*SV*Q*EG**TLSE ***L*INCTYT ***......YP* LFWY*QYP GEG*QLLL* A***...*** G*N.....K GFEA*Y**ET TSFHL*K*SV** SDSAVY*C AL*Clade 5 GLR AQ*V*QP***V*V*E G*PLT*KCTYS *SG......*PY LFWYVQ*P **GLQFLLK Y*TGD..NLV KG*.....Y GFEAEFNKSQ TSFHLKK*SAL* SDSA*YFC AV*Clade 6 GTR AQ*VTQPEK*LSVF* GAPV*LKC*YS YSG......SP* LFWYV*YP *QRLQLLLR HI......SR ES*.....K GFTADLNK** TSFHL*K*FAQE EDSA*YYC ALSClade 7 GT* AQSVTQ*D****V*E *****LRCNYS SSS*.....*** LFWYVQYP NQGL*LLLK Y**G..**LV *GI.....* *F*AEF*KSE TSFHL*K*S*H* SD*A*YFC AV*Clade 8 **R AQ*V*Q*******SE ****EL*CNYS Y***.....*** LFWYVQ*P *Q*LQLLL* ****..***V *GI.....K GFEAE***** *SF*L*K***** SD*A*YFC A**GAClade 9 **S LAKTTQ.PI*M*SYE GQEVNI*C*H* *IAT.....*** I*WY*QFP *QGPR*IIQ GYK.....*N **N.....E VASLF***DR KSSTL*LPR**L SD*AVYYC ***Clade 10 T*I DAKTTQ.P*SMDC*E G*A*NLPCNHS TI**.....*EY **W*RQ** S**PQY**H GL*.....N* *TN.....* MASL*I**DR KSSTL*LPH*TL RD***YYC IVRVClade 11 I*G DAKTTQ.PNS*E**E EEPV*LPCNHS TISG.....**Y **WYRQ** *Q*PEYVIH GL*.....*N V**.....* MA*L*I**DR KSSTLIL***TL *D*AVY*C I*RClade 12 SS* SQ*VIQ*QPAIS*QE GET**LDC*** T***.....YY* **WYK**P ****I*LI* Q*T**..*T* ***.....* *YSV****A* *TI*LIIS*SQP EDSATYFC *L*EClade 13 *GI AQK*TQ******VQE KE*VTL*CTYD T***.....*Y* LFWYKQPS SGEMI**I* Q*SY..***N *TE.....G RYSLNFQKA* K***LVISASQ* *DSA*YFC A***Clade 14 *SM **KVTQ****IS**E K**VTLDC*Y* ****.....*YY L*WYKQ** **E***L** **S*..*EQ* ***.....G RY**NFQK*T SS***TI*A*Q* *DSA*YFC AL**Clade 15 *** AQTVTQ*Q*EMSV*E *E*VTL*CTY* *S**.....*Y* L*WYKQ*P S*QM***I* Q**Y..*QQN A**.....N RFSVNFQKAA KS*SL*IS*SQL *D*A*YFC A***Clade 16 *T* GQ***Q.P*E*TA*E G**VQ*NCTYQ TS*......F*G L*WYQQ** G*AP**LSY **L....DGL ***.....G *FSSFL**S* *Y*YLLL**LQ* KDSASY*C AVRClade 17 V** *****Q*P**L***E G****LNC*** ***......*** **WFRQDP GKG**SL** IQS*...Q*E Q**.....* *****L*K** **S******S*P *DSATY*C A****LPClade 18 M*R G***EQSP*FL*V*E GD**VINCTYT DS*......STY *YWYKQ*P G**LQLL** I*SN...*D* KQD.....* RL*V*LNK** KHLSL*I*D*Q* *DSA*YFC A*SClade 19 V** GENVEQ*PSTL*VQ* GD**VI*CTYS DSA......S*Y FPWYKQEL GKGP***ID IRSN..**** NK*.....* R**V*LNK*A KH*SLHI***QP *DSA*YFC AA*Clade 20 *** *E**GLH*PT**VQE GD*S*INC*YS *SA......S*Y **WYKQE* GKGPQ*I*D IRSN...**K ***.....* R*TV*LNKT* KHLSL*I**T** GDSAVYFC AE*Clade 21 *SQ *K*VEQ******V*E ******NCTYS ***......*** F*WYRQ** *K*P*L*** *YS*...*** N**.....G RFT******S *Y*SL*IRDS** SDSATYLC A**Clade 22 *SG KNQVEQSPQSL*ILE G*NCTLQCNYT V*P......F*N LRWYKQD* G*GP**L** MT*S...*N* *S*.....G RYTATLDA** K*SSLH*TA*QL SDSASYIC VV*Clade 23 VNS QQGEE**.Q*LSIQE GENA**NCSYK *SI.......** LQWYRQ*S *R****L*L IRSN...*RE ***.....G RLR*TL*TS* KSSSL*I*A**A ADTA*YFC A**Clade 24 V*S QKIEQN*.**L*I*E G**A**TCNYT *YS......P** *QWYRQDP G*G*VFLLL IREN...E*E K**.....* RL*VTFDTTL KQ**F*I*ASQP ADSATYLC A*DClade 25 VRS Q***Q*P.***I**E GE****NC*SS **L.......YS V*WYRQK* *E***FLM* LLKG...GEQ K*H.....D KI*A**NEKK QQSSL****SQ* *YS*TYFC **EClade 26 **S QE*EQSP.*SL**QE G**LTI*C*SS KTL.......Y* **WY*QKY GEGGLIFLM *L**..*GEE KSH.....* KITAKLDEKK QQS*LHITA**P SH*GIYLC G**Clade 27 VSG QQLNQSP.QS***QE *EDVSMNCTSS S*F.......N* *LWYKQD* GEGPVLL** L*K*...GEL T*N.....G RL*AQFGITR KDSFLNISAS*P *DVG*YFC AGClade 28 V*T Q*LEQSP.*FLSIQE GE**T*YCNSS S*F.......** L*WYR**P GEGPVLL** *V**...GE* KK*.....K RLTFQFGDAR KDSSLHIT**QP GDTGLYLC AGClade 29 **G QQ**QIP.Q**H*QE GEDF*TYCN** **L.......** *QWYKQRP GG*PV*L** L*K*...GEV KK*.....K RLT**FGE** K*SSLHITA*QT *DVGTYFC A*AQCS*Clade 30 V*S *LNVEQSPQSL*VQE GDSTNFTCSFP SS*......FYA LHWYRWET AK*P**LFV M*LN...GDE KK*.....G R***TLNTKE GYSYLYIKGSQ* EDSATYLC A*Clade 31 VSS EDKV*Q*P**L*VHE *D**T**C*YE ***......F*S L*WYKQEK *AP*FLF*L *SSG....IE KKS.....G *LSSILD*** **S*LNITAT*T *DSA*YLCA*EAQCSLClade 32 **G E*QV***P**L**Q* G***S**C*Y* VS*......*** L*WYRQ** G*GP**L** *YS.....AG *EK.....* K*RL*A*L*K **S*L*IT***P EDSA*Y*C AV*Clade 33 L*G E*KV*Q*PL*LSTQE G***TIYCNYS ***......S*R L*WYRQDP GKSLE*LFV LLSN...GAV KQE.....G *L*ASLDTKA RLS*LHI*A*** *LSATYFC AVClade 34 V**A*NEV*QSPQ*LT*QE GE*ITINCSYS *G*.......** L*WLQQ*P GGGIVSLF* LSS.....** KK*.....G RL*ATIN*QE *HSSLHITAS*P RDSA*YIC AVClade 35 *VR G**V*QSP**L***E G****L*CNFS ***.......** *QWF*QNP *G*LI*LF* ***.....GT KQ*.....G RL**T****E **S*L*I***Q* *DS**Y*C A***QCSP

Figure 4: The phylogenetic trees of the AA translated sequences from TRAV exons from 16 primates species. V exonsequences are obtained from whole genome shotgun (WGS) datasets using the Vgenextractor algorithm. Alignmentof the amino acid sequences was performed with clustalO, tree construction with FastTree using the WAG matrix, andvisualization with Figtree. The original tree with all V exon sequences are shown to the left. Clades are collapsed inthe center tree to better illustrate the sequence similarities. Representative subclades, 8 and 23, are shown to the rightto illustrate the distribution of constituent primate taxa. At the bottom part of the figure, the consensus sequences ofeach clade are shown, where the amino acids that are found in more than 90% of the sequences are marked by theirletter, while the variable regions are represented by an asterisk (”*”)

13

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

0.08

TDSSSTY---IF

SNMDM

Vs285|Panpaniscu

s

SDSASNY---IR

SNEHE

Vs463|P

apioanubis

TDSSSTY---IL

SNTDL

Vs519|Macacafascicu

laris

SDSASDY---IR

SNMAK

Vs320|Macacamulatta

TDSSSTY---IL

SNMDL

Vs311|Macacamulatta

SNSASDY---IR

SNMDK

Vs121|Gorilla

gorilla

SDSASSY---IR

SNMGK

Vs329|Micro

cebusmurinus

SDSASNY---IR

SNAHE

Vs525|M

acacafascicularis

TDSASTY---IF

SNMDK

Vs237|Tarsiu

ssyrich

ta

TDSSSTY---IL

SNMDL

Vs554|Papioanubis

TDSSSTY---IF

SNMDM

Vs382|Pantroglodytes

SNSASDY---IR

SNMDK

Vs355|Homosapiens

TDSSSSY---IL

SNTDM

Vs584|Saimirib

olivie

nsis

SDSASNY---IR

SNVDK

Vs644|Callith

rixjacch

us

SDSASTY---IR

SNMDK

Vs205|Tarsiu

ssyrich

ta

SDSASNY---IR

SNVGE

Vs118|Gorilla

gorilla

SDSASNY---IR

SNVGE

Vs498|N

omascus

leucogenys

SDSASDY---IR

SNMAK

Vs467|Papioanubis

TDSTSTY---L

SNAEKK

Vs966|Otolemurgarnettii

SDSASNY---IR

SNMGE

Vs725|P

ongoabelii

TDSTFTY---IL

SNVDK

Vs521|Daubentoniamadagasca

riensis

TDSSSTY---IF

SNMDL

Vs488|Nomascu

sleucogenys

SDSASNY---IR

SNVGE

Vs351|H

omosapiens

SDSASDY---IR

SNMAK

Vs917|Chlorocebussabaeus

SNSASIY---IR

SNRDK

Vs346|Micro

cebusmurinus

SDSASDY---IR

SNMDK

Vs723|Pongoabelii

SDSASNY---IH

SNMGE

Vs390|Pantroglodytes

SDSASNY---IR

SNVDK

Vs577|Saimirib

olivie

nsis

SDTASSY---IR

SNEGK

Vs176|Tarsius

syrichta

TDSSSTY---IF

SNMDM

Vs109|Gorilla

gorilla

SDSASSY---IR

SNVNR

Vs1043|Otolemurgarnettii

TDSSSTY---IF

SNMDM

Vs341|Homosapiens

TETTSTY---IF

SYEDK

Vs283|Micro

cebusmurinus

SDSASDY---IR

SNMAK

Vs529|Macacafascicu

laris

SDSASSY---IR

SNMDK

Vs177|Tarsiu

ssyrich

ta

SDSASNY---IR

SNMGE

Vs293|P

anpaniscus

SDSASTY---IR

SNMGK

Vs555|Daubentoniamadagasca

riensis

SDSASNY---IR

SNAHE

Vs317|Macaca

mulatta

SNSASDY---IR

SNMDK

Vs393|Pantroglodytes

SDSASDY---IR

SNMDK

Vs501|Nomascu

sleucogenys

TDSSSTY---IL

SNTDL

Vs909|Chlorocebussabaeus

TDSSSTY---IF

SNMDL

Vs764|Pongoabelii

SNSASDY---IR

SNMDK

Vs296|P

anpaniscus

Clade18

Clade19

Clade20

CDR1(i)

CDR2(i)

Framework

3Framework

2Framework

1

CDR1(i)

CDR2(i)

Figure5:

Detailed

representationof

theclades

18,19and

20form

edfrom

thealignm

entofthe

AA

sequencesof

TR

AVexon

sequencesof

primates.

The

phylogenetictree

(left)showthe

CD

R1(i)and

CD

R2

(i)sequencesin

ordertodem

onstratethe

similarity

ofthesesequences

between

mem

bersofthe

same

clade.Sequencealignm

ent(right)isshow

nforclade-18

andclade-20.T

heregions

thatarem

arkedhave

beendefined

byouranalysis

software,Trozos,(see

materialand

methods).

14

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

0.3

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

1

345

67

8

9

10

12

13

1415

16

1718

1920

21

2223

24

25

2

11

0.3

FR1-IMGT CDR1-IMGT FR2-IMGT CDR2-IMGT FR3-IMGT CDR3-IMGT

A B BC C C' C'C" C" D E F FG

(1-15) (16-26) (27-38) (39-46) (47-55) (56-65) (66-74) (75-84) (85-96) (97-104) ——————————————> ——————————> ———————> ————————> ————————> —————————> ———————————> ———————>

(1-26) (27-38) (39-55) (56-65) (66-104) (105-117)

1 10 15 16 23 26 27 38 3941 46 47 55 56 65 66 74 75 84 85 89 96 97 104 105 |........|....| |......|..| |..........| |.|....| |.......| |........| |.......| |........| |...|......| |......| |.....

Clade 1 *L ***VSQ*PSR*ICK* G*SV*IEC*** DFQ......ATT MFWYRQ** *Q*L*L*AT SN*G..S**T YEQG***.* *F*I*H*.*L T*S*LTV**AHP EDSSFY*C S**Clade 2 V* ****SQKPSR**CQ* GTS**IQC*** SQ*.......** MFWY*Q*P G****L*AT ANQG..S*AT YE**F**.D KFPIS*P.NL *FST**VSN**P EDS**Y*C S**Clade 3 ** DG*ITQSPKYLFRKE GQ*VTL*CEQN LNH.......DA MYWYRQDP GQGLRLIYY S**....V*D *QKGDI*.E GYSVSRE.*K *SFPLTVTSAQ* N*TAFYLC ASSIClade 4 P* EAQVTQNPRYLITVT GKKLTVTCSQN MNH.......*Y MSWYRQDP GLGLRQIYY S*N....V** *DKGD*P.E GY*VSRK.EK RNFPLI*ESP*P *QTSLY*C ASSLClade 5 LV ***VTQ**R*L*KR* GE*V*LEC*QD MDH.......** MFWYRQDP GLGLRLIYF S*D....*** *E*GD*P.* GY*VSR*.KK **FSL*L*SA*T *QTS*YLC ASS*SAClade 6 ** *A***Q*PR***I*T GK***L*CSQ* M*H.......** MYW***** G*******Y S**....**S TE*GD*S.* ***VSR*.** **FPLTLESA** **TS*YLC ASS*Clade 7 *M DA*VTQTPRN*I*KT G**I*LECSQT **H.......** MYWYRQDP GLGL*LIYY S**....V*D **KGE*S.* GY*VSR*.*Q *KFSLSLE*A** NQTALYFC A*S*Clade 8 H* DA*ITQ*PR*K*TET G**VTL*CHQT **H.......** M*WYRQD* G*GLRLI*Y S**....*** **K*EV*.D GY*VSRS.** E*F*LTLESA** SQTSVYFC A*S*Clade 9 ** *A*VTQ*P****L** GQ**T**C*QD M*H.......** M*WYRQD* G*GLRLI*Y S**....*G* T**GEV*.* GY*VSR*.** **F*L*L*SA** SQTS*YFC ASS*ATVClade 10 *R *QT*HQWPA**VQP* GSPLSLECTV* GTS......NP* LYWYRQ** ***LQLLFY S**.....** Q**SE**.Q NLSASR*.Q* **F*LSSKKLLL SDSGFYLC AWSClade 11 H* **MVIQNPRYQ*T** *KPVTLSCSQN *NH.......** MYWYQQK* SQAPKLL** YYD....*** N*E*DT*.D NFQ**RP.NT SFC**DI*S*GL *D*A*YLC A*S*Clade 12 *L DTAV*QTPKYL*TQ* G****LKCEQ* LGH.......** MYWYKQDS *K*LK*MF* Y*N*....** **NET**.* RFSP*S*.DK A*L*LHI*S*E* GDSAVY*C ASS*Clade 13 P* ****TQTP*HLV*** **KK*L*CEQ* *GH.......** MYWY*Q** *K**E*MF* Y**....*** **N**VP.S RF*PE**.*S S*L*LH***LQP EDSA*YLC ASSQClade 14 *V *AGV*Q*PR*LIK*K *E*A*L*CYP* **H.......*T VYWYQQ*P *Q**QFLIS *Y*....KMQ **KG*IP.* RF*AQQF.*D YHSE*N*SSLEL GDSA*Y*C ASS*Clade 15 *V D*GVTQTPKHL*TA* GQ*VTLRCSPR SGD.......*S VYWY*QSL *Q*LQFLIQ YYN....G*E **KGNI*.E RFS*QQF.** **SELNLSSLEL GDSALYFC ASS*Clade 16 ** **GVTQ*P**LIK*R GQQVTL*CSP* SGH.......** V*WYQQ** GQG*Q**** Y**....*** ***GNFP.* RFS**QF.** **SE*NV***** *DSALYLC ASSLClade 17 L* NAG**QNPRHLVRR* GQEA*L*CSP* KGH.......*H VYWY*QL* *EGLKFM*Y LQKE...**I DESGMP*.* *FSAEFP.KE GPS*L*IQQA** *DSA*YFC ASS*Clade 18 SP GEEV*QTP*HLV*G* GQKA*LYC*PI *G*.......*Y *FWYQ*VL *KEFKFLIS FQN*...N*F D*TGMPK.* RFSAKC*.*N S*CSLEIQAT** *DSA*Y*C ASSQClade 19 S* DT*VTQ*PR**V*** *QK*K*DCVP* K*H.......SY VYWY*K*L *EELKFL*Y *QN*...**I *K*E*IN.* RF*AQC*.*N S*C*LEIQSTE* GD***YFC A*S*Clade 20 *F *A*VTQTPG*L*K*K G*K**M*C*P* *GH.......** **WYQQ*Q NKE***L** FQ**...*** **TE**K.* RFS**CP.** *PC*L*I*S**P GD*ALY*C ASS*Clade 21 ** DAGV*Q*P*H*VTEM G**VT*RC*PI *GH.......** **WYRQT* **GLE*L*Y F***...*** DDS*MPK.D RFSA*MP.** ***TLKIQP*EP *DSA*Y*C AS*LClade 22 H* *AGVTQFPSH*VIEK GQ*VTLRCDPI SGH.......** L*WYRR*M GKE*KFL** F***...**Q DESGMP*.* RF*A**T.GG T*STL*VQ*AEL EDSG*YFC ASS*Clade 23 *T EP*V*QTPSHQVT*M GQ*VIL*C*PI **H.......** FYWYRQI* GQK*EFL** F***...*I* **SEIF*.D *FS**R*.*G ***TLKI*STKL EDSA*YFC ASS*Clade 24 ** EA*V*QSPRYKI*EK *Q*V*FWC*P* SGH.......*T LYWY*Q*L GQGP*LL** ****...**V DDSQLPK.D RFSAER*.KG V*STL*IQPA*L *DSA*YLC ASSLClade 25 H* *AGVSQ*P**K**** G**V***CDPI S*H.......** LYWY*Q** GQG*E*L*Y F***...*** **SGL**.* RF*A*R*.*G S*STL*IQ*T*Q *DSA*YLC ASS*ARA

Figure 6: The phylogenetic trees of the AA translated sequences from TRAV exons from 16 primates species. V exonsequences are obtained from whole genome shotgun (WGS) datasets using the Vgenextractor algorithm. Alignmentof the amino acid sequences was performed with clustalO, tree construction with FastTree using the WAG matrix, andvisualization with Figtree. The original tree with all V exon sequences are shown to the left. Clades are collapsed inthe center tree to better illustrate the sequence similarities. Representative subclades, 3, 16, and 33, are shown to theright to illustrate the distribution of constituent primate taxa. At the bottom part of the figure, the consensus sequencesof each clade are shown, where the amino acids that are found in more than 90% of the sequences are marked by theirletter, while the variable regions are represented by an asterisk (”*”).

15

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

Table 5: Number of TRAV exons present in each clade by specie in the phylogenetic tree defined in Figure 4.

Clade D. m

adag

asca

r.

O. g

arne

ttii

M.m

urin

us

T .sy

rich

ta

C. j

acch

us

S.bo

livie

nsis

M.m

ulat

ta

M.f

asci

cula

ris

C. s

abae

us

P.an

ubis

N. l

euco

geny

s

P .ab

elii

G. g

orill

a

P .pa

nisc

us

P .tr

oglo

dyte

s

H. s

apie

ns

1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 12 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 03 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 14 3 4 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 15 1 2 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 16 0 0 0 0 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 2 27 2 1 1 2 0 3 2 3 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 38 4 8 5 4 2 3 2 2 1 2 3 3 4 3 4 39 1 2 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

10 1 0 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 111 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 2 1 0 2 112 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 013 2 2 0 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 114 2 5 1 2 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 115 1 15 0 1 1 0 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 216 0 2 0 1 1 2 2 2 1 2 1 3 2 1 2 217 1 1 0 2 1 1 1 1 3 0 2 2 1 1 1 118 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 119 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 120 1 0 2 2 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 121 3 5 3 2 3 3 2 3 2 3 3 2 3 3 3 322 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 123 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 124 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 125 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 026 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 127 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 128 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 2 129 1 1 3 1 0 0 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 0 3 130 1 0 0 0 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 0 1 1 2 131 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 132 0 0 0 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 2 2 2 233 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 134 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 135 4 7 4 2 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

16

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

Table 6: Number of TRBV genes present in each primate species in the phylogenetic clades defined in Figure 6.

Clade D. m

adag

asca

r.

O. g

arne

ttii

M. m

urin

us

T .sy

rich

ta

C.j

acch

us

S.bo

livie

nsis

M. m

ulat

ta

M.f

asci

cula

ris

C.s

abae

us

P.an

ubis

N.l

euco

geny

s

P .ab

elii

G. g

orill

a

P .pa

nisc

us

P .tr

oglo

dyte

s

H.s

apie

ns

1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 22 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 13 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 14 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 15 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 16 1 0 0 0 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 3 2 2 2 27 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 18 1 2 1 0 2 3 2 2 3 3 2 3 2 2 3 29 0 4 2 0 3 3 3 5 6 7 4 8 6 8 8 6

10 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 111 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 112 0 2 4 1 2 1 2 4 3 4 3 3 2 2 2 113 1 3 4 0 4 1 4 3 3 3 4 4 2 3 3 314 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 115 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 116 1 2 5 0 5 4 5 7 8 8 4 7 6 7 7 617 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 118 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 119 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 3 2 1 1 120 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 221 1 2 1 1 4 3 4 3 3 3 1 5 3 2 2 322 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 123 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 3 3 3 4 1 1 1 124 0 1 1 2 2 0 2 3 3 3 1 2 2 2 3 325 1 3 3 1 4 4 4 9 6 9 2 5 7 6 6 5

17

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

Once the sequence fragments FR1, FR2, FR3, and the CDRs were separated, we studiedwhether each V exon of the TRV is unique to each species and whether it has an ortholog inother species (as suggested by the results of the phylogenetic trees). Figure 7 shows the par-ticular case of a randomly selected V exon sequence for illustration (Vs367 of H. sapiens forthe TRAV and Vs168 of M. mulatta from the TRBV locus; sequences can be obtained fromhttp://vgenerepertoire.org). For example, in the case of the TRAV sequence shown (ie., Vs367Homo sapiens), each of the 4 segments (CDRS, FR1, FR2 and FR3) differ significantly from otherTRAV sequences within the same species, appearing as an outlier in the boxplot of Figure 7. In12 primate species, we found one or two sequences which are similar, indicating that that they areorthologs. This phenomenon occurs in each of the segments, indicating the uniqueness of eachV gene. We repeated the same experiment for the TRBV genes (ie., the Vs168 exon sequenceof Macaca mulatta, shown in Figure 7 (bottom)). The results are similar to those of the TRAV,however unique V exon sequences were not found in the FR2 regions.

The data generated from the phylogenetic tree suggests frequent changes in the gene loci of IGas well as a reduced permissiveness in the genes of the TR chains. The theory of birth and death ofgenes has been postulated as a mechanism that directs the evolutionary processes of these genes.In Figure 8 we studied this hypothesis by quantifying sequence similarities higher than 90 % insegments over 3000 bases in the IGHV, TRAV and TRBV loci between the orangutan, human andmacaque species. The results show that In the IGHV locus, there are more tracks and cross linkingas compared to the TR loci. Also, comparing species uncovers relationships in the IGHV locusover evolutionary time. For example, the number of IGHV tracks and crossovers is higher betweenhuman and macaque (more distantly related species) than between human and orangutan (moreevolutionarily close species). In the TRAV and TRBV loci, the tracks are approximately parallel,indicating that in these loci, less duplication/deletion processes took place between speciationevents, contrasting what can be observed in the IGHV locus.

4. Discussion

In previous studies (Olivieri et al., 2013, 2014), we showed data indicating a different evolu-tionary process between the V genes of IG and TR. In IG, the processes of birth and death are quiteevident. We also highlighted the grouping of sequences into established IMGT clans and proposednew clades. For the species studied in this work, we describe the clustering of the IG light chainsequences into major clades. While these groupings are not as obvious as the three clans of theIGH chains, we can establish these light chain clades with certainty due to the large number ofsequences, supporting their existence. The grouping of the IGL chains into five clades is of par-ticular interest, since these clades originated prior to the diversification of mammals and reptilesand interestingly both have remained in evolutionary lines for over 300 million years, suggestinga functional significance of each clade which is still unknown.

All loci containing V exons are very similar. Despite this wide similarity, there are starkevolutionary differences amongst the IG and TR loci. The IG loci exhibit a more pronounced rateof change as than the TR loci. This is seen by observing sequences between species of primateswhere there is greater sequence conservation in the TCR loci. Besides the evidence left as relicsin genomic sequences, frequent duplications of IG genes generate recent clades with multiple

18

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

05

10

15

05

10

15

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

01

02

03

04

0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Vs2

08

05

10

15

20

25

30

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

05

10

15

05

10

15

20

25

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

11

12

13

14

15

16

05

10

15

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

01

02

03

04

0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

CDRs(i)Vs367 Homo sapiens

PSSNFYA---MTLNGDE

Frame 2(i)Vs367 H

om

o sa

pie

ns

LHWYRWETAKSPEALFV

Frame 3(i)Vs367 H

om

o sa

pie

ns

LNGDEKKKGRISATLNTKEGYSYLYIKGSQPEDSATYLCA

Frame 1(i)Vs367 H

om

o sa

pie

ns

VSSILNVEQSPQSLHVQEGDSTNFTCSF

CDRs(i)Vs168 M

aca

ca_m

ula

tta

NLNHDAM---SQIVNDI

Frame 1(i)Vs168 M

aca

ca_m

ula

tta

TMDGRITQSPKYLFRKEGQNVTLSCEQ

Frame 2(i)Vs168 M

aca

ca_m

ula

tta

MYWYRQDPGQGLRLIYY

Frame 3(i)Vs168 M

aca

ca_m

ula

tta

NDIQKGDIAEGYSVSRERKESFPLTVTSAQRNPTAFYLCASS

TRAVTRBV

Num

ber o

f identica

l sequence

sN

um

ber o

f identica

l sequence

sN

um

ber o

f identica

l sequence

sN

um

ber o

f identica

l sequence

s

Hom

o sa

pie

ns

Pan

trog

lod

yte

s

Pan

pan

iscus

Gorilla

gorilla

Pon

go a

belii

Nom

ascu

s leu

cog

en

ys

Pap

io a

nu

bis

Ch

loro

ceb

us sa

baeu

s

Maca

ca fa

scicula

ris

Maca

ca m

ula

tta

Saim

iri boliv

iensis

Callith

rix ja

cchu

s

Tarsiu

s syrich

ta

Micro

ceb

us m

urin

us

Oto

lem

ur g

arn

ettii

Dau

ben

ton

ia m

ad

ag

asca

rien

sisVs506

Vs633

Vs565

Vs837

Vs544

Vs898

Vs1041

Vs514

Vs133

Vs531

Vs1097

Vs367

Hom

o sa

pie

ns

Pan

trog

lod

yte

s

Pan

pan

iscus

Gorilla

gorilla

Pon

go a

belii

Nom

ascu

s Leu

cog

en

ys

Pap

io a

nu

bis

Ch

loro

ceb

us sa

baeu

s

Maca

ca fa

scicula

ris

Maca

ca m

ula

tta

Saim

iri boliv

iensis

Callith

rix ja

cchu

s

Tarisiu

s syrich

ta

Micro

ceb

us m

urin

us

Oto

lem

ur g

arn

ettii

Dau

ben

ton

ia m

ad

ag

asca

rien

sis

Vs506 V

s633

Vs565

Vs837

Vs544 V

s898

Vs1041

Vs514

Vs133

Vs531

Vs405

Vs367

Vs506

Vs239

Vs633

Vs565

Vs36

Vs544

Vs898

Vs1041

Vs514

Vs133

Vs531

Vs405

Vs367

Vs367

Vs405

Vs531

Vs133

Vs514

Vs1041

Vs898

Vs544

Vs36

Vs565

Vs633V

s506

Vs223

Vs202

Vs827

Vs488

Vs144

Vs876

Vs652

Vs418

Vs168

Vs179

Vs158

Vs563

Vs223

Vs202

Vs827

Vs488

Vs144

Vs876

Vs652

Vs418

Vs168

Vs179V

s158

Vs563

Vs223

Vs202

Vs827

Vs488

Vs144

Vs192

Vs876

Vs652

Vs418

Vs168

Vs179

Vs158

Vs674

Vs383

Vs707

Vs463

Vs223

Vs202

Vs827

Vs488

Vs144

Vs192

Vs876

Vs652

Vs413

Vs163

Vs179

Vs158

Vs563

Vs687

Figure7:

Participationof

eachof

thecanonical

segments,

FR1,

FR2,

FR3,

CD

R1,

andC

DR

2,from

theam

inoacid

translatedV

exonsequences

ofthe

uniquelyidenticalgenes.From

thesesequences,w

eobtained

thefram

ework

regions(1,2

and3)and

othersequencescreated

artificiallyw

iththe

two

CD

Rs

(1and

2).A

concretecase

ofsequences,originating

froma

TR

AVsequence

(top)w

ascom

pared(identity

number)

with

therestof

thefragm

entsobtained

fromallT

RAV

exonsfrom

allspecies.The

same

experimentw

asperform

edw

ithspecific

sequencesofa

TR

BV

(bottom).

19

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

1V 2V3V 4V 5V 6V 7V8V 9V 10V

11V12V

13V

14V15V16V

17V

18V19V

20V21V22V

23V

24V

25V26V27V

28V29V

30V

31V32V

33V34V35V

36V37V38V

39V40V41V42V

43V44V45V

46V47V

48V49V

50V51V

52V

1VR

1V 2V3V 4V 5V6V 7V 8V9V 10V11V12V13V14V15V

16V17V

18V19V

20V

21V

22V23V24V25V26V

27V28V29V

30V31V32V33V

34V35V36V

37V38V

39V

40V

41V42V

43V

1VR

1V 2V 3V 4V 5V 6V 7V8V 9V 10V11V

12V13V

14V

15V16V17V18V

19V

20V

21V

22V23V24V

25V

26V

27V

28V29V30V31V32V

33V34V35V36V37V

38V39V40V

41V42V

43V

44V

1VR

macaco record macaco record macaco record macaco record macaco record

Human record Human record Human record Human record Human record

orangutan record orangutan record orangutan record orangutan record

IGHV

TRAV

TRBV

P. abelii

H. sapiens

M. mulatta

P. abelii

H. sapiens

M. mulatta

P. abelii

H. sapiens

M. mulatta

1000000

1VR2VR

3VR4VR

5VR6VR

7VR8VR

9VR10VR

11VR12VR

13VR14VR

15VR16VR

17VR18VR

19VR20VR

1VR2VR

3VR4VR

5VR6VR

7VR8VR

9VR10VR

11VR12VR

13VR14VR

15VR16VR

17VR18VR

19VR20VR

21VR22VR

23VR24VR

25VR26VR

27VR28VR

29VR30VR

31VR32VR

33VR34VR

35VR36VR

37VR38VR

39VR40VR

41VR42VR

43VR44VR

45VR

1VR2VR

3VR4VR

5VR6VR

7VR8VR

9VR10VR

11VR12VR

13VR14VR

15VR16VR

17VR18VR

19VR20VR

21VR22VR

23VR24VR

25VR26VR

27VR28VR

29VR30VR

31VR32VR

33VR34VR

35VR36VR

37VR38VR

39VR40VR

41VR42VR

43VR44VR

45VR46VR

47VR

macaco record macaco record macaco record

Human record Human record Human record Human record

orangutan record orangutan record orangutan record orangutan record orangutan record

1000000

1V 2V 3V 4V 5V 6V 7V8V 9V 10V

11V

12V13V

14V

15V

16V

17V18V

19V20V

21V

22V23V24V

25V26V27V28V29V30V

31V

32V

33V34V

35V36V37V

38V39V

40V

41V

42V

1VR

1V 2V 3V 4V 5V 6V 7V 8V9V10V

11V

12V13V14V

15V16V

17V

18V

19V

20V21V

22V

23V

24V

25V26V27V28V

29V

30V

31V32V

33V34V

35V36V

37V38V39V

1V 2V 3V 4V 5V 6V 7V 8V9V 10V

11V

12V

13V14V

15V

16V

17V18V19V

20V

21V

22V

23V

24V

25V

26V

27V28V

29V30V

31V32V33V

34V

1VR

macaco record macaco record macaco record macaco record macaco record

Human record Human record Human record Human record

orangutan record orangutan record orangutan record orangutan record

Figure 8: Identical Sequence within the IGHV, TRAV and TRBV loci from the three species of primates, H. sapiens, P.abelii and M. mulatta. For each species, the V exon sequences were extracted from genomic segments available at theEnsemble repository www.ensembl.org. For our analysis pipeline, we used Galaxy (http://galaxy.wur.nl). Sequencesfor the tracks were obtained in the following way: we performed a BLASTN against the orangutan and macaquesequences (ie., the db), with the query consisting of human sequence. We selected sequence identities > 60% and analignment length > 3000 bases and the figure was made with a custom python script. The locations of the V exons,marked in red, were obtained with Vgenextractor (http://vgenerepertoire.org/).

20

peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/006924doi: bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 8, 2014;

members. Evolution provides a defense mechanism of an organism for rapid adaptation of IGchains to a rapidly changing external infectious environment.

In the TRA and TRB loci, there is a conservation of V exons and a low duplication permis-siveness. In particular, we found a conservation of 35 TRAV exon sequences and 25 TRBV exonsequences. Nonetheless, in some species, we did not detect any conserved V exons. This may be amethodological error (Vgenextractor only detects 95 % of the V exons from WGS data sets) or thesystem may be slightly redundant, permitting some V exon loss without compromising the sur-vival of the individual. Similarly, in the TR loci we detected duplication events but never observedmultiple duplications, such as those in the IG loci.