Utilization of Multiple Restorative Materials in Full-Mouth...

Transcript of Utilization of Multiple Restorative Materials in Full-Mouth...

Utilization of Multiple Restorative Materials inFull-Mouth Rehabilitation: A Clinical Report

JUNG NAM, DMD, MS, MSD*

ARIEL J. RAIGRODSKI, DMD, MS†

HARALD HEINDL, MDT‡

ABSTRACTMany different restorative materials are currently available for use in modern dentistry. Clini-cians and dental technicians should be able to choose the most suitable materials for eachpatient based on research, anecdotal evidence, clinical experience, as well as patient’s expecta-tions and desires. The purpose of this article is to share the challenges presented in full-mouthrehabilitation and to describe the considerations in selecting three different restorative materialsto achieve a successful restoration in terms of biomechanics, function, and esthetics.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCEInterdisciplinary treatment planning, knowledge of available restorative materials, sequencingtreatment modalities, and adequate communication between all parties involved are key to asuccessful treatment outcome when pursuing full-mouth restorative rehabilitation.

(J Esthet Restor Dent 20: 251–265, 2008)

I N T R O D U C T I O N

Satisfying patients’ high expecta-tions for dental esthetics is one

of the challenges in contemporarydental therapy for both cliniciansand dental technicians. As part oftreatment planning, cliniciansshould be able to choose theappropriate restorative materials toachieve excellence in naturalesthetics as well as proper biome-chanics and durability.1 Whiletreatment planning for restorativeprocedures, many different factorsmust be considered. Cliniciansshould evaluate the prognosis of

the individual dentition in terms ofgingival and periodontal health,structural compatibility and vital-ity, and position. In addition,patients must be evaluated compre-hensively in terms of parafunc-tional habits, occlusal wearpatterns, existing occlusal schemes,skeletal relationships, inter- andintra-arch relationship, verticalheight and horizontal width of theresidual alveolar ridges (forimplant-supported restorations aswell as for pontics), and dentofa-cial esthetics. Additional factorsto be considered are the type of

individual restoration required(complete crowns, fixed partialdentures [FPDs], partial-coveragerestorations), shade of individualteeth and the harmony of shadebetween adjacent restorations, thetype of foundation restoration ifneeded, the type of implant abut-ment and restoration, and the typeof pontic. Bearing in mind all ofthe above considerations and withthe ample restorative materialsavailable for indirect restorations,material selection should be cus-tomized to the individual needs ofthe patient while taking into

*Former resident, Graduate Prosthodontics, Department of Restorative Dentistry, School of Dentistry,University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; private practice, Seoul, Korea

†Associate professor and director, Graduate Prosthodontics, Department of Restorative Dentistry,School of Dentistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

‡Master dental technician, Aesthetic Dental Creations, Mill Creek, WA, USA

© 2 0 0 8 , C O P Y R I G H T T H E A U T H O R SJ O U R N A L C O M P I L AT I O N © 2 0 0 8 , W I L E Y P E R I O D I C A L S , I N C .DOI 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2008.00188.x V O L U M E 2 0 , N U M B E R 4 , 2 0 0 8 251

account the materials’ mechanicaland optical properties, its biocom-patibility, and the skills of thedental ceramist and the clinician.

Although gold and metal-ceramicshave been used for many yearswith a high level of clinicalsuccess,2–4 the challenge of achiev-ing ideal esthetics may be facili-tated with the use of all-ceramicrestorations. With highly translu-cent teeth, matching the shade andother optical properties to adjacentteeth restored with metal-ceramicrestorations may pose a challengeto the dental ceramist and restor-ative dentist. Therefore, the pros-pect of using different all-ceramicmaterials to match in different seg-ments of the mouth, which mayrequire different mechanical prop-erties, may prove advantageous.

There are three major categories ofdental ceramic core materials: glass-ceramics, glass-infiltrated ceramics,and polycrystalline ceramics. Eachcategory of ceramic core materialshas sub-branches with differentchemistry and composition.5 Clini-cal studies have demonstrated thatdifferent ceramic cores showed dif-ferent levels of clinical success andlongevity. Although some materials’success has been limited to the ante-rior segment, others have demon-strated clinical success in theposterior segment as well.6–11 Theselection of an all-ceramic systemis confounding because of many

available different systems andscarcity of information regardingtheir long-term use in particular forposterior FPDs.12 On the otherhand, clinical studies demonstratedhigh success rates with metal-ceramics2–4 and porcelain laminateveneers13–16 and proved theirsafety of use.

As dental materials continue toevolve, new all-ceramic materialswith superior mechanical proper-ties, such as high flexural strengthand high fracture toughness, arecontinuously being introduced tothe market.17,18 Such are thezirconia-based computer-aideddesign and computer-aided manu-facturing (CAD/CAM) systems,which have been introducedrecently.19 These systems aregaining popularity in both theanterior and posterior segmentsfor multiple indications.20–24

Zirconia is the strongest andtoughest ceramic material availableso far.20 Clinical reports and anec-dotal evidence demonstrated thatzirconia-based restorations couldbe used for both anterior and pos-terior complete crowns andFPDs.20–22 Moreover, short-termclinical studies demonstrated favor-able results on the use of zirconia-based systems for posterior FPDs,which is the ultimate and mostchallenging mechanical and func-tional clinical test. In terms ofmechanical challenges presented by

zirconia-based systems, thesestudies reported some minor cohe-sive chipping of the veneering por-celain mainly on the secondmolars, which did not require thereplacement of the restoration.Thus, with these types ofrestorations, the weak link may bethe veneering porcelain.22–24

The purpose of this article is todemonstrate and discuss the chal-lenges of material selection for full-mouth fixed rehabilitation. Thefollowing clinical report describesthe different considerations inselecting different restorativematerials to achieve asuccessful restoration.

C A S E P R E S E N TAT I O N

A 57-year-old Caucasian malepatient presented with the follow-ing chief complaints: “I would liketo have longer teeth and have abetter-looking smile.” His medicalhistory was noncontributory exceptfor history of gastroesophagealreflux disease (GERD). The patientwas referred to the gastroenterol-ogy department for evaluation.However, his medical consultationreported that he did not have anycurrent signs or symptomsof GERD.

Extraoral examination indicatedrelative facial symmetry, straightfacial profile, asymptomatictemporomandibular joint (TMJ),and asymptomatic muscles of

U T I L I Z AT I O N O F R E S T O R AT I V E M AT E R I A L S I N F U L L - M O U T H R E H A B I L I TAT I O N

252© 2 0 0 8 , C O P Y R I G H T T H E A U T H O R SJ O U R N A L C O M P I L AT I O N © 2 0 0 8 , W I L E Y P E R I O D I C A L S , I N C .

mastication and facial expression.Dentofacial analysis demonstratedvisually a shortened facial heightfor the lower third of the face anda slightly enlarged interocclusalspace, implying a minor loss ofvertical dimension of occlusion.25

The maxillary dental midline devi-ated 1.0 mm to the right side ascompared with the facial midline.At rest, the patient did not displayany portion of his teeth (Figure 1),but in full smile, he displayedabout 90% of his maxillarycentral incisors.26

Clinical examination revealedseveral “cupping” lesions on theocclusal surfaces of his posteriordentition. The patient was recom-mended the use of fluoride mouthrinse and toothpaste to increase thepotential for remineralization anddecrease the potential for deminer-alization.27 The patient presentedwith composite-resin and amalgamrestorations, missing teeth, a goldonlay, gold crowns, and metal-

ceramic crowns. Some of these res-torations were failing because ofoverhanging margins, recurrentcaries, and fractures. The majorityof the posterior dentition was struc-turally compromised. Tooth #3 wasextracted because of fracture a yearprior to the initial examination.Moderate tooth structure loss wasnoticed in the anterior as well asposterior dentition because oferosion. Although exposed dentinwas noticed on the palatal surfacesof maxillary incisors and on someof the occlusal surfaces of premo-lars and molars, the patient did notreport or demonstrate any signs orsymptoms of sensitivity. The clinicalcrown length of maxillary centralincisors was 8 mm and that ofmandibular central incisors was5 mm. Thus, in general, thepatient displayed short clinicalcrowns (Figures 2–4).

Periodontal examinationwas within normal limits, withthe patient revealing a thick

periodontal biotype. Radiographicexamination demonstrated gener-ally adequate bone levels andcrown-to-root ratios, with theexception of the endodonticallytreated tooth #29, which presentedminimal bone loss, nonfavorablecrown-to-root ratio, and a periapi-cal pathosis (Figure 5).

Diagnostic data collection includedclinical examination, full-mouthperiapical radiographs, a pan-oramic radiograph, diagnosticcasts, dentofacial analysis, photo-graphic documentation, and adiagnostic wax-up. The dentofacialanalysis was made utilizing anindirect acrylic-resin occlusionrim.28,29 The treatment planincluded initial preparation andcaries removal and complete-mouth clinical crown lengtheningsurgical procedures to expose 1.5to 2 mm of tooth structure circum-ferentially for adequate ferrule forresistance and retention forms atthe posterior segments, and to

Figure 1. An initial frontal view of the patient atrest position.

Figure 2. A frontal view of the patient’s dentition in maximumintercuspal position.

N A M E T A L

V O L U M E 2 0 , N U M B E R 4 , 2 0 0 8 253

facilitate esthetic gingivallevels anteriorly.30

The patient expressed his desire todisplay more teeth both at rest andsmile. As the patient did notdisplay any maxillary teeth at rest,the maxillary incisors were plannedto be lengthened 2 mm incisally.31

Thus, the maxillary central incisorswere planned to be lengthened1.5 mm apically and 2 mm inci-sally. The vertical dimension ofocclusion was planned to be

restored by a 3-mm increase at theincisor area in order to gain morespace for the restorative materialsand to make longer maxillary andmandibular incisors.25 After anadequate healing period, restor-ative procedures were planned forthe full-mouth rehabilitation,including complete crowns andFPDs and porcelain laminateveneers for the mandibularanterior dentition. Additionally,tooth #29 was planned to beextracted because of poor crown-

to-root ratio, poor ferrule,external root resorption, andpathologic mobility.

After the removal of failing resto-rations and caries removal, estheticclinical crown lengthening surgicalprocedures were performed asplanned with the diagnosticwax-up (Figure 6). According tobone sounding procedures madeprior to surgeries, normal crestdentogingival dimensions werenoticed.32 In addition, the

Figure 3. A preoperative maxillary occlusal view. Note thefailing restorations and the structurally compromisedbicuspids. Cupping lesions can be noted on the bicuspidsand second molars as well as wear on the anterior teeth.

Figure 4. A preoperative mandibular occlusal view. Notethe failing restorations and tooth wear.

Figure 5. Preoperative full-mouth periapical radiographs. Figure 6. A frontal view of the diagnosticwax-up.

U T I L I Z AT I O N O F R E S T O R AT I V E M AT E R I A L S I N F U L L - M O U T H R E H A B I L I TAT I O N

254© 2 0 0 8 , C O P Y R I G H T T H E A U T H O R SJ O U R N A L C O M P I L AT I O N © 2 0 0 8 , W I L E Y P E R I O D I C A L S , I N C .

cementoenamel junction (CEJ) wasdetected 1.5 mm below the freegingival margins. A vacuum-formed surgical template was usedas a reference for the prospectivedesired gingival levels during thesurgeries. Full-thickness flaps withscalloped incisions were elevated topreserve interdental papillae.33,34

Osteotomy was performed accord-ing to surgical templates to develop2.0 mm of biologic width and1.0 mm of sulcular depth.35,36

After 9 months of healing, the gin-gival tissues were matured andready for the restorative treatment(Figure 7).37 The teeth were pre-pared according to a vacuum-formed preparation guide, and self-cured acrylic-resin shells wereclinically relined to fabricate self-cured acrylic-resin interim restora-tions.38 The complete crowns andFPDs were prepared and planned tobe completed prior to the treatmentwith porcelain laminate veneers on

the mandibular anterior dentition(Figures 8 and 9). The diagnosticinterim restorations were modifieduntil the patient was satisfied withphonetics, esthetics, and function(Figure 10). The interim restora-tions were placed on prepared teethand functioned for about 4 monthsto assess the patient’s adaptation tothe proposed new vertical dimen-sion of occlusion and the new clini-cal crown lengths. Subsequently, thegingival tissue around the tooth

Figure 7. A frontal view of the patient’s dentition in maximumintercuspal position after healing post crown lengtheningprocedures.

Figure 8. An occlusal view of the maxillarypreparations.

Figure 9. An occlusal view of the mandibularpreparations.

Figure 10. A frontal view of the patient’s smile with theprovisional restorations.

N A M E T A L

V O L U M E 2 0 , N U M B E R 4 , 2 0 0 8 255

preparations had matured and wasready for making the masterimpressions using polyvinylsiloxaneimpression material (Imprint IIIlight body & Imprint II PentaHeavy body, 3M ESPE, St. Paul,MN, USA). The double-cord tech-nique was utilized to retract thetissues to expose preparation finishlines. First cord, a #00 (Ultrapack,Ultradent, South Jordan, UT, USA),was used, and the second cord wasselected as needed among #0, 1,and 2 (Ultrapack, Ultradent). Acentric relation record was made,utilizing the anterior interim resto-rations as an anterior referencepoint and silicon interocclusalrecord material in the posterior seg-ments (Jet-bite, Coltène/Whaledent,Altstatten, Switzerland).

In choosing the restorative materi-als, zirconia-based crowns and an

FPD (Lava, 3M ESPE, St. Paul,MN, USA) were selected, excludingteeth #’s 2-p-4, 15, 17, 22 to 27,and 31 (Figures 11–13). The man-dibular anterior dentition wasplanned to be restored with feld-pathic porcelain laminate veneers,and teeth #’s 2-p-4, 15, 17, and 31were planned to be restored withmetal-ceramic crowns and an FPD.Zirconia-based restorations wereselected because of the patient’sexpectations and demands of highesthetics, metal-free oral environ-ment, high biocompatibility, properfunction, and longevity in both theanterior and posterior segmentsand for FPDs as initially demon-strated in clinical studies. An addi-tional consideration was the abilityto use one all-ceramic system thatcould be delivered using conven-tional luting procedures because ofthe patient’s gingival health, which

was less than perfect. Metal-ceramic restorations were selectedfor the second molars and for theFPD with the second molar retainerbecause of reports of chipping ofveneering porcelain mainly on thesecond molars in clinical studiesevaluating posterior zirconia-basedFPDs. After the definitive cast wasfabricated and sectioned, a defini-tive full-contour wax-up was com-pleted and tried in the patient’smouth to verify esthetics (Fig-ure 14). The dies were scanned forthe fabrication of the all-ceramiccopings and the FPD framework.

Lava Ceram Overlay Porcelain(3M ESPE) was selected for layer-ing porcelain of the zirconia-basedall-ceramic restorations, and IPSD-Sign (Ivoclar, Schaan, Liechten-stein) was selected for the metal-ceramic restorations, with high

Figure 11. The mandibular FPD is designed utilizing theCAD unit. Note that an interocclusal record is used toallow for adequate design of the framework to allow foradequate space and support for the veneering porcelain.

Figure 12. An occlusal view of the maxillary zirconia-basedcopings on the maxillary definitive cast.

U T I L I Z AT I O N O F R E S T O R AT I V E M AT E R I A L S I N F U L L - M O U T H R E H A B I L I TAT I O N

256© 2 0 0 8 , C O P Y R I G H T T H E A U T H O R SJ O U R N A L C O M P I L AT I O N © 2 0 0 8 , W I L E Y P E R I O D I C A L S , I N C .

noble alloy (Aquarius XH, IvoclarWilliams, Amherst, NY, USA), andfor the porcelain laminate veneers.Porcelain butt margins were usedon the facial aspect of tooth #4retainer of the metal-ceramic FPD.A silicone-based disclosing agent(Fit Checker, GC, Tokyo, Japan)was utilized for fit verification andas try-in paste prior to the defini-tive cementation for final estheticevaluation and initial occlusal

adjustments. The teeth were air-particle abraded with 50 mm Al2O3

prior to the cementation proce-dures. The definitive completecrowns and FPDs of the maxillaryarch and the mandibular posteriorsegments were ready for cementa-tion (Figures 15–18). Because ofthe excellent mechanical propertiesof zirconia, a conventional cemen-tation technique was selected. Aself-etching, self-adhesive, dual-

cured composite resin cement(RelyX Unicem, 3M ESPE) wasused for all crowns and FPDs. Atranslucent shade was used for thezirconia-based crowns and FPD.

With the aid of a silicone matrixmade of the diagnostic wax-up, A2shade light-cured direct compositeresin buildups (Filtek Supreme PlusUniversal Restorative, 3M ESPE)were completed for the mandibular

Figure 13. An occlusal view of the mandibularzirconia-based copings and the FPD framework onthe mandibular definitive cast.

Figure 14. A frontal view of the full-contour wax-up.

Figure 15. An occlusal view of the maxillary restorationson the definitive cast.

Figure 16. An occlusal view of the mandibular restorationson the definitive cast.

N A M E T A L

V O L U M E 2 0 , N U M B E R 4 , 2 0 0 8 257

anterior teeth right after thecompletion of the cementation pro-cedures for the crowns and FPDs.This allowed the clinicians toprovide the patient with thedesired new anterior guidanceimmediately on the day of cemen-tation. The composite resin build-ups were also utilized aspreparation guides for the prospec-tive porcelain laminate veneers.

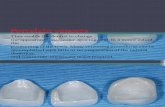

Subsequently, the mandibular inci-sors and canines were prepared for

feldspathic porcelain laminateveneers (Figure 19) and provision-alized utilizing an indirect bis-GMA (Synfony, 3M ESPE), whichwas temporarily cemented withflowable composite resin after spotetching. Feldspathic porcelain lami-nate veneers were fabricated usingthe refractory die technique. IPSD-Sign porcelain (Ivoclar Vivadent,Amherst, NY, USA) was used forthe veneers’ fabrication. Once triedin, the porcelain laminate veneerswere bonded with a translucent

shade of light-cured compositeresin cement (RelyX Veneer, 3MESPE) (Figures 20–22). A heat-processed hard occlusal guard(Lucitone Clear, Dentsply, York,PA, USA) was delivered for manag-ing clenching habit, providing thepatient with a mutually protectedocclusion (Figures 23–25).

D I S C U S S I O N

Loss of tooth structure presentedwith this patient was attributed tothe erosion caused by GERD.

Figure 17. A view of the intaglio surface of the maxillary anteriorrestorations with zirconia margins.

Figure 18. A close-up of the maxillary centralincisors definitive restorations. Note the detailedcharacterizations.

Figure 19. An occlusal view of the mandibularveneer preparations.

Figure 20. A postoperative frontal view of the patient’srestoration in maximum intercuspal position.

U T I L I Z AT I O N O F R E S T O R AT I V E M AT E R I A L S I N F U L L - M O U T H R E H A B I L I TAT I O N

258© 2 0 0 8 , C O P Y R I G H T T H E A U T H O R SJ O U R N A L C O M P I L AT I O N © 2 0 0 8 , W I L E Y P E R I O D I C A L S , I N C .

Figure 21. A postoperative lateral view of the patient’s leftside in left laterotrusive movement.

Figure 22. A postoperative lateral view of the patient’sright side in right laterotrusive movement.

Figure 23. A close-up of the patient’s smile. Note the blending between thezirconia-based crowns and the feldspathic porcelain laminate veneers.

Figure 24. A postoperative view ofthe patient’s full face smile.

Figure 25. Postoperative full-mouth periapical radiographs.

N A M E T A L

V O L U M E 2 0 , N U M B E R 4 , 2 0 0 8 259

GERD is one of the intrinsic causesof dental erosion. Patients withGERD present with delayed acidclearance. Tests such as endoscopicexamination and 24-hour esoph-ageal pH monitoring are used foraccurate diagnosis. Avoiding fattyand spicy foods and elevating thehead of the bed is part of the treat-ment being rendered. Histamine-2blockers and proton pump inhibi-tors as well as medications toenhance gastric motility are pre-scribed to treat GERD. The physi-ologic type of GERD may betemporary and thus may notrequire medications. The treatmentof dental erosion resulting fromGERD must be multidisciplinaryand should include the physician,gastroenterologist, restorativedentist, and dietary consultant.27

The patient did not show any signsor symptoms of parafunctionalhabits or nocturnal bruxism exceptfor self-reporting of minor clench-ing habits during the day. The res-toration was built with mutuallyprotected occlusion.39

Clinical crown lengthening proce-dures were performed prior to therestorative procedures in order tominimize the duration of theinterim restorative phase, thusreducing the prospects of provi-sional cement wash out and thedevelopment of recurrent caries.40

The restorations differed betweenthe maxillary anterior dentition

and the mandibular anterior denti-tion. Restoring the maxillary ante-rior teeth required the use ofcomplete crowns because of theexposure of dentin on the palatalsurfaces and the prospect ofincreasing the vertical dimension ofocclusion. However, porcelain lami-nate veneers were selected torestore mandibular anterior denti-tion, thus allowing predictableconservative restorations withrelatively less invasive clinical pro-cedures.41 Complete crowns andFPDs were completed prior totreatment with porcelain laminateveneers. This was done because ofthe challenge of predictably main-taining interim veneers during therelatively extended interim restor-ative phase. Zirconia-based restora-tions were selected for the crownsand an FPD, excluding the secondmolar restorations where metal-ceramics restorations with porce-lain occlusal surfaces were utilizedbecause of the overriding consider-ations of managing higher occlusalforces42 and the evidenceof longevity.2–4

Zirconia was selected from avariety of different all-ceramic corematerials because of its uniqueproperties. Zirconia presents withhigh biocompatibility, facilitatinggingival response,43,44 less frame-work distortion during firingcycles,20 and adequate marginalfit.20 In addition, the recommendedsize of posterior connectors for a

zirconia FPD framework is 9 mm2,which may provide better estheticresults with an ideal embrasureform and a better periodontalresponse as compared to other all-ceramic core materials.23 Moreover,most zirconia-based systems allowfor shaded copings and frame-works as related to the prospectivecolor of the restoration, whileallowing some level of light trans-mission similar to alumina-basedceramic systems.45 With itssuperior mechanical properties interms of flexural strength and frac-ture toughness as compared toother all-ceramic materials,zirconia-based restorations mayserve as a restorative alternativefor both the anterior andposterior segments.22–24,46,47

The integration of different typesof restorative materials in complexfull-mouth rehabilitations can be achallenging task for the dentaltechnician. It requires thoroughknowledge, understanding, andcreativity to match the shades andhandle the different materials.Various veneering porcelains anddifferent types of core materialsexhibit different optical properties,light reflection, and light absorp-tion. Thus, the ceramist must takeseveral steps in order to compen-sate for the color discrepancies ofdifferent types of ceramic cores.

A careful selection of the veneeringporcelains under the aspect of

U T I L I Z AT I O N O F R E S T O R AT I V E M AT E R I A L S I N F U L L - M O U T H R E H A B I L I TAT I O N

260© 2 0 0 8 , C O P Y R I G H T T H E A U T H O R SJ O U R N A L C O M P I L AT I O N © 2 0 0 8 , W I L E Y P E R I O D I C A L S , I N C .

color matching is a necessity. Acomparison of the individual shadetabs of the porcelain systems isrequired to translate shade fromone porcelain system to the other.In the presented patient, a superiorharmony of the dentins and effectenamels used with metal-ceramicporcelain and the veneering porce-lain for the zirconia frameworkfacilitated an adequate translationfrom one system to the other interms of shade matching.

It is imperative to follow a strictlayering protocol throughout theporcelain stratification. Such layer-ing protocol is the blueprint for theporcelain buildup process andderived from the buildup conceptof suitable single-tooth restorationscertainly in accordance with thepatient’s wishes and preferences.The shade properties of the feld-spathic porcelain laminate veneersfor the mandibular anterior teethare influenced to a certain degreeby the color of the underlyingtooth structure. The zirconiaframework is a substructure with arelatively high value and a whitishappearance in strong contrast tothe metal framework, which exhib-its an unfavorable gray opaquecolor. The gray color of the metalsubstructure must be compensatedby certain measures. Thus, thevalue of the metal-ceramic restora-tions must be slightly elevated tocompensate for the metal’s lowervalue. With the presented patient, a

material with a high value wasplaced underneath the dentinbuildup to obtain the desiredeffects and color match. Thismeasure is also recommended toachieve better harmony betweenthe feldspathic porcelain laminateveneers and the metal-ceramic res-torations. The utilization of thesame veneering material is clearlyindicated. The intense chroma ofthe prepared teeth required a slightcompensation with an opaceousceramic material.

C O N C L U S I O N S

A successful esthetic result usingthree different restorative materialswas achieved in the presented full-mouth rehabilitation. The use ofthree different restorative materialsand different techniques posed achallenge in achieving naturalesthetic appearance, and in satisfy-ing biomechanics and function aswell as the patient’s ultimatedesires. However, although techni-cally challenging, this approachfacilitated a more conservativetreatment in terms of usingconservative porcelain laminateveneers in the mandibular anteriorsegment and achieving esthetics inboth the anterior and posteriorsegments utilizing selectively bothall-ceramics and metal-ceramicswithout neglecting biomechanicalconsiderations. Interdisciplinarytreatment planning, adequate treat-ment sequencing, excellent commu-nication between all members of

the treatment rendering team, anda good understanding of the mate-rials in terms of their mechanicaland optical properties by both cli-nicians and dental ceramists arekey to a successful result of thistype of comprehensive therapy.

D I S C L O S U R E A N D

A C K N O W L E D G M E N T S

The authors thank Drs. SimoneVerardi and Byung-Do Ham forthe periodontal surgeries presentedin this case and to Ms. DanielaHeindl for the metal frameworkfabrication presented in this case.

The authors do not have anyfinancial interest in the companieswhose materials are included inthis article.

Some of the photos as well assome of the information in thismanuscript were published inMaterials Selection for Complete-Coverage All-CeramicRestorations—Ariel J. Raigrodskiin “Interdisciplinary TreatmentPlanning: Principles, Design, Imple-mentation” Editor: Michael,Cohen. Permission for use wasgiven by Quintessence Publishing,Carol Stream, IL, USA.

R E F E R E N C E S

1. Cortellini D, Canale A, Giordano A,et al. The combined use of all-ceramicand conventional metal-ceramic restora-tions in the rehabilitation of severe toothwear. Quintessence Dent Technol2005;28:205–14.

N A M E T A L

V O L U M E 2 0 , N U M B E R 4 , 2 0 0 8 261

2. Walton TR. A 10-year longitudinal studyof fixed prosthodontics: clinical charac-teristics and outcome of single-unit metal-ceramic crowns. Int J Prosthodont1999;12:519–26.

3. Walton TR. An up to 15-year longitudi-nal study of 515 metal-ceramic FPDs:part 1. Outcome. Int J Prosthodont2002;15:439–45.

4. Rosenstiel SF, Land MF, Fujimoto J.Contemporary fixed prosthodontics. 4thed. St. Louis (MO): Mosby Elsevier;2006. p. 258–85.

5. Raigrodski AJ. All-ceramic full-coveragerestorations: concepts and guidelines formaterial selection. Pract Proced AesthetDent 2005;17:249–56.

6. Moffa JP, Lugassy AA, Ellison JA. Clini-cal evaluation of castable ceramic mate-rial. Three year study. J Dent Res1988;67:118.

7. Hankinson JA, Cappetta EG. Five years’clinical experience with a leucite-reinforced porcelain crown system. Int JPeriodontics Restorative Dent1994;14:138–53.

8. Segal BS. Retrospective assessment of 546all-ceramic anterior and posterior crownsin a general practice. J Prosthet Dent2001;85:544–50.

9. Oden A, Andersson M, Krystek-Ondracek I, Magnusson D. Five-yearclinical evaluation of Procera AllCeramcrowns. J Prosthet Dent 1998;80:450–6.

10. Lehner C, Studer S, Brodbeck U, ScharerP. Short-term results of IPS-Empress full-porcelain crowns. J Prosthodont1997;6:20–30.

11. Fradeani M, Redemagni M. An 11-yearclinical evaluation of leucite-reinforcedglass-ceramic crowns: a retrospectivestudy. Quintessence Int 2002;33:503–10.

12. Sorensen JA, Cruz M, Mito WT, et al. Aclinical investigation on three-unit fixedpartial dentures fabricated with a lithiumdisilicate glass-ceramic. Pract PeriodonticsAesthet Dent 1999;11:95–106.

13. Friedman MJ. A 15-year review of porce-lain veneer failure—a clinician’s observa-tions. Compend Contin Educ Dent1998;19:625–32.

14. Dumfahrt H, Schaffer H. Porcelain lami-nate veneer. A retrospective evaluationafter 1 to 10 years of service: partII-clinical results. Int J Prosthodont2000;13:9–18.

15. Peumans M, De Munck J, Fieuws S, et al.A prospective ten-year clinical trial ofporcelain veneers. J Adhes Dent2004;6:65–76.

16. Fradeani M, Redemagni M, Corrado M.Porcelain laminate veneers: 6- to 12-yearclinical evaluation—a retrospective study.Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent2005;25:9–17.

17. Raigrodski AJ. Contemporary materialsand technologies for all-ceramic fixedpartial dentures: a review of the litera-ture. J Prosthet Dent 2004;92:557–62.

18. Raigrodski AJ. Contemporary all-ceramicfixed partial dentures. Dent Clin NorthAm 2004;48:531–44.

19. Witkowski S. CAD/CAM in dental tech-nology. Quintessence Dent Technol2005;28:169–84.

20. Sorensen J. The lava system for CAD/CAM production of high-strength preci-sion fixed prosthodontics. QuintessenceDent Technol 2003;26:57–67.

21. McLaren EA, Giordano RA. Zirconia-based ceramics: material properties,esthetics, and layering techniques of anew veneering porcelain, VM9. Quintes-sence Dent Technol 2005;26:99–111.

22. Vult von Steyern P, Carlson P, Nilner K.All-ceramic fixed partial denturesdesigned according to the DC-Zirkontechnique. A 2-year clinical study. J OralRehabil 2005;32:180–7.

23. Raigrodski AJ, Chiche GJ, Potiket N,et al. The efficacy of posterior three-unitzirconium-oxide-based ceramic fixedpartial dental prostheses: a prospectiveclinical pilot study. J Prosthet Dent2006;96:237–44.

24. Sailer I, Feher A, Filser F, et al. Five-yearclinical results of zirconia frameworks forposterior fixed partial dentures. Int JProsthodont 2007;20(4):383–8.

25. Kois J, Phillips K. Occlusal verticaldimension: alteration concerns.Compend Contin Educ Dent1997;18:1169–77.

26. Tjan AH, Miller GD, The JG. Someesthetic factors in a smile. J Prosthet Dent1984;51:24–8.

27. Barron RP, Carmichael RP, Marcon MA,Sandor GK. Dental erosion in gastroe-sophageal reflux disease. J Can DentAssoc 2003;69:84–9.

28. Phillips K, Morgan R. The acrylicocclusal plane guide: a tool for estheticocclusal reconstruction. Compend ContinEduc Dent 2001;22:302–6.

29. Magne P, Belser U. Novel porcelain lami-nate preparation approach driven by adiagnostic mock-up. J Esthet Restor Dent2004;16:7–17.

30. Magne P, Gallucci GO, Belser UC. Ana-tomic crown width/length ratios ofunworn and worn maxillary teeth inwhite subjects. J Prosthet Dent2003;89:453–61.

31. Vig RG, Brundo GC. The kinetics ofanterior tooth display. J Prosthet Dent1978;39:502–4.

32. Kois JC. Altering gingival levels: therestorative connection part I: biologicvariables. J Esthet Dent 1994;6:3–9.

33. Cattermole AE, Wade AB. A comparisonof the scalloped and linear incisions asused in the reverse bevel technique. J ClinPeriodontol 1978;5:41–9.

34. McGuire MK. Periodontal plasticsurgery. Dent Clin North Am1998;42:411–65.

35. Vacek JS, Gher ME, Assad DA, et al. Thedimensions of the human dentogingivaljunction. Int J Periodont Rest Dent1995;14:154–65.

36. Gargiulo AW, Wentz FM, Orban B.Dimensions and relationships of the den-togingival junction in humans. J Period-ontol 1961;32:261–7.

37. Pontoriero R, Carnevale G. Surgicalcrown lengthening: a 12-month clinicalwound healing study. J Periodontol2001;72:841–8.

38. Yuodelis RA, Faucher R. Provisionalrestorations: an integrated approach toperiodontics and restorative dentistry.Dent Clin North Am 1980;24:285–303.

U T I L I Z AT I O N O F R E S T O R AT I V E M AT E R I A L S I N F U L L - M O U T H R E H A B I L I TAT I O N

262© 2 0 0 8 , C O P Y R I G H T T H E A U T H O R SJ O U R N A L C O M P I L AT I O N © 2 0 0 8 , W I L E Y P E R I O D I C A L S , I N C .

39. Parker MW. The significance of occlusionin restorative dentistry. Dent Clin NorthAm 1993;37:341–51.

40. Ramirez OI, Schuler RF, Heindl H.Treating complex cases using an interdis-ciplinary approach for predictable aes-thetic and functional outcome. PractProced Aesthet Dent 2005;17:275–81.

41. Dietschi D. Bright and white: is it alwaysright? J Esthet Restor Dent 2005;17:183–90.

42. Mansour RM, Reynik RJ. In vivo occlusalforces and moments: I. Forces measured in

terminal hinge position and associatedmoments. J Dent Res 1975;54:114–20.

43. Warashina H, Sakano S, Kitamura S,et al. Biological reaction to alumina, zir-conia, titanium and polyethylene particlesimplanted onto murine calvaria. Biomate-rials 2003;24:3655–61.

44. Cales B, Stefani Y. Yttria-stablilizedzirconia for improved orthopedic prosthe-sis. In: Wise DL, editor.Encyclopedic handbook of biomaterialsand bioengineering. New York (NY):Marcel Dekker; 1995.pp. 415–52.

45. Edelhoff D, Sorensen J. Light transmis-sion through all-ceramic framework andcement combinations. IADR 2002(abstract 1779).

46. Hauptmann H, Suttor D, Frank S,Hoescheler H. Material propertiesof all-ceramic zirconia prostheses.J Dent Res 2000;79:507.

47. Suttor D, Hauptmann H, Frank S,Hoescheler S. Fracture resistanceof posterior all ceramic zirconiabridges. J Dent Res 2001;80:640.

N A M E T A L

V O L U M E 2 0 , N U M B E R 4 , 2 0 0 8 263