Using Examinations to Improve...

Transcript of Using Examinations to Improve...

WORl D BA.NK TECHNICAL PAPER NUMBER 165

AFRKI. A TECHNICAL DEPART MEN,T SERES

Using Examinations to Improve Education

A Study in ]Fourteen African Countries

Thomas Kellaghan and Vincent Greaney

A L

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

Pub

lic D

iscl

osur

e A

utho

rized

RECENT WORLD BANK TECHNICAL PAPERS

No. 103 Banerjee, Shrubs in Tropical Forest Ecosystems: Examples from India

No. 104 Schware, The World Software Industry and Software Engineering: Opportunities and Constraintsfor Newly Industrialized Economies

No. 105 Pasha and McGarry, Rural Water Supply and Sanitation in Pakistan: Lessons from Experience

No. 106 Pinto and Besant-Jones, Demand and Netback Values for Gas in Electricity

No. 107 Electric Power Research Institute and EMENA, The Current State of Atmospheric Fluidized-BedCombustion Technology

No. 108 Falloux, Land Information and Remote Sensing for Renewable Resource Management in Sub-SaharanAfrica: A Demand-Driven Approach (also in French, 108F)

No. 109 Carr, Technologyfor Small-Scale Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa: Experience with Food Crop Productionin Five Major Ecological Zones

No. 110 Dixon, Talbot, and Le Moigne, Dams and the Environment: Considerations in World Bank Projects

No. 111 Jeffcoate and Pond, Large Water Meters: Guidelines for Selection, Testing, and Maintenance

No. 112 Cook and Grut, Agroforestry in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Farmer's Perspective

No. 113 Vergara and Babelon, The Petrochemical Industry in Developing Asia: A Review of the CurrentSituation and Prospects for Development in the 1990s

No. 114 McGuire and Popkins, Helping Women Improve Nutrition in the Developing World: Beating the ZeroSum Game

No. 115 Le Moigne, Plusquellec, and Barghouti, Dam Safety and the Environment

No. 116 Nelson, Dryland Management: The "Desertification" Problem

No. 117 Barghouti, Timmer, and Siegel, Rural Diversification: Lessons from East Asia

No. 118 Pritchard, Lending by the World Bankfor Agricultural Research: A Review of the Years 1981through 1987

No. 119 Asia Region Technical Department, Flood Control in Bangladesh: A Plan for Action

No. 120 Plusquellec, The Gezira Irrigation Scheme in Sudan: Objectives, Design, and Perfornance

No. 121 Listorti, Environmental Health Components for Water Supply, Sanitation, and Urban Projects

No. 122 Dessing, Support for Microenterprises: Lessons for Sub-Saharan Africa

No. 123 Barghouti and Le Moigne, Irrigation in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Development of Publicand Private Systems

No. 124 Zymelman, Science, Education, and Development in Sub-Saharan Africa

No. 125 van de Walle and Foster, Fertility Decline in Africa: Assessment and Prospects

No. 126 Davis, MacKnight, IMO Staff, and Others, Environmental Considerations for Port and HarborDevelopments

No. 127 Doolette and Magrath, editors, Watershed Development in Asia: Strategies and Technologies

No. 128 Gastellu-Etchegorry, editor, Satellite Remote Sensing for Agricultural Projects

No. 129 Berkoff, Irrigation Management on the Indo-Gangetic Plain

No. 130 Agnes Kiss, editor, Living with Wildlife: Wildlife Resource Management with Local Participationin Africa

No. 131 Nair, The Prospects for Agroforestry in the Tropics

No. 132 Murphy, Casley, and Curry, Farmers' Estimations as a Source of Production Data: MethodologicalGuidelines for Cereals in Africa

No. 133 Agriculture and Rural Development Department, ACIAR, AIDAB, and ISNAR, AgriculturalBiotechnology: The Next "Green Revolution"?

(List continues on the inside back cover)

v<o)AFRICA TECHNICAL DEPARTMENT SERIES

Technical Paper Series

No. 122 Dessing, Support for Microenterprises: Lessons for Sub-Saharan Africa

No. 130 Kiss, editor, Living with Wildlife: Wildlife Resource Management with Local Participation in Africa

No. 132 Murphy, Casley, and Curry, Farmers' Estimations as a Source of Production Data: MethodologicalGuidelines for Cereals in Africa

No. 135 Walshe, Grindle, Nell, and Bachmann, Dairy Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Study of Issuesand Options

No. 141 Riverson, Gaviria, and Thriscutt, Rural Roads in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from World Bank Experience

No. 142 Kiss and Meerman, Integrated Pest Management and African Agriculture

No. 143 Grut, Gray, and Egli, Forest Pricing and Concession Policies: Managing the High Forests of Westand Central Africa

No. 157 Critchley, Reij, and Seznec, Water Harvestingfor Plant Production, vol. I: Case Studiesand Conclusions for Sub-Saharan Africa

No. 161 Riverson and Carapetis, Intennediate Means of Transport in Sub-Saharan Africa: Its Potentialfor Improving Rural Travel and Transport

Discussion Paper Series

No. 82 Psacharopoulos, Why Educational Policies Can Fail: An Overview of Selected African Experiences

No. 83 Craig, Comparative African Experiences in Implementing Educational Policies

No. 84 Kiros, Implementing Educational Policies in Ethiopia

No. 85 Eshiwani, Implementing Educational Policies in Kenya

No. 86 Galabawa, Implementing Educational Policies in Tanzania

No. 87 Thelejani, Implementing Educational Policies in Lesotho

No. 88 Magalula, Implementing Educational Policies in Swaziland

No. 89 Odaet, Implementing Educational Policies in Uganda

No. 90 Achola, Implementing Educational Policies in Zambia

No. 91 Maravanyika, Implementing Educational Policies in Zimbabwe

No. 101 Russell, Jacobsen, and Stanley, International Migration and Development in Sub-Saharan Africa,vol. I: Overview

No. 102 Rlussell, Jacobsen, and Stanley, International Migration and Development in Sub-Saharan Africa,vol. H: Country Analyses

No. 147 Jaeger, The Effects of Economic Policies on African Agriculture: From Past Harm to Future Hope

WORLD BANK TECHNICAL PAPER NUMBER 165

AFRICA TECHNICAL DEPARTMENT SERIES

Using Examinations to Improve Education

A Study in Fourteen African Countries

Thomas Kellaghan and Vincent Greaney

The World BankWashington, D.C.

Copyright © 1992The Intemational Bank for Reconstructionand Development/THE WORLD BANK1818 H Street, N.W.Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A.

All rights reservedManufactured in the United States of AmericaFirst printing February 1992

Technical Papers are published to communicate the results of the Bank's work to the developmentcommunity with the least possible delay. The typescript of this paper therefore has not been prepared inaccordance with the procedures appropriate to formal printed texts, and the World Bank accepts noresponsibility for errors.

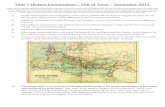

The findings, interpretations, and condusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s)and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or tomembers of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. The World Bank does notguarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility whatsoeverfor any consequence of their use. Any maps that accompany the text have been prepared solely for theconvenience of readers; the designations and presentation of material in them do not imply the expressionof any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Bank, its affiliates, or its Board or member countriesconcerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, or area or of the authorities thereof orconcerning the delimitation of its boundaries or its national affiliation.

The material in this publication is copyrighted. Requests for permission to reproduce portions of it shouldbe sent to Office of the Publisher at the address shown in the copyright notice above. The World Bankencourages dissemination of its work and will normally give permission promptly and, when thereproduction is for noncommercial purposes, without asking a fee. Permission to photocopy portions fordassroom use is not required, though notification of such use having been made will be appreciated.

The complete backlist of publications from the World Bank is shown in the annual Index of Publications,which contains an alphabetical title list (with full ordering information) and indexes of subjects, authors,and countries and regions. The latest edition is available free of charge from the Distribution Unit, Officeof the Publisher, Department F, The World Bank, 1818 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A., orfrom Publications, The World Bank, 66, avenue d'I6na, 75116 Paris, France.

ISSN: 0253-7494

Thomas Kellaghan is director of the Educational Research Centre, St. Patrick's College, Dublin.Vincent Greaney is an education specialist at the World Bank.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kellaghan, Thomas.Using examinations to improve education: a study in fourteen

African countries / Thomas Kellaghan and Vincent Greaney.p. cm. - (World Bank technical paper, ISSN 0253-7494; no.

165. Africa Technical Department series)Includes bibliographical references (p. ).ISBN 0-8213-2052-11. Examinations-Africa, Sub-Saharan. 2. Educational evaluation-

-Africa, Sub-Saharan. I. Greaney, Vincent. II. Title.Im. Series: World Bank technical paper; no. 165. IV. Series:World Bank technical paper. Africa Technical Department series.LB3058.A357K45 1992371.2.'6'0967-dc2O 92-164

CIP

Foreword

Public examinations tend to exert enor- country are outlined in the report. Issuesmous influence on the nature of learning and discussed include low pass rates, the back-teachLing; they tend to dictate not only what wash effect that examinations have on teach-is taught but also how it is taught. In devel- ing and on grade repetition, the roles ofcping countries, while most examinations school-based and practical assessment, theserve a number of functions, including cer- implications of national language policies,tification and accountability, their main func- the use of quotas and compensation proce-tion is to select students for the next highest dures, the publication of national schoollevel of the educational system. Their im- rankings based on examination performance,pact is most pronounced due to the short- and the low level of technical support avail-age of places, particularly at the secondary able to examination authorities. Guidelinesand tertiary levels of formal schooling. are offered for improving the quality of ex-

This study presents for the first time a aminations and for using examinations todetailed description of the types, functions, improve education.performance levels, governance, administra- Many current international issues in thetion, and funding of public examinations in controversial topic of examinations anda range of African countries with different assessment are addressed. Thus, the studyeducational traditions. The national public- should be of interest to ministry of educa-examination systems of fourteen Sub- tion officials, national examination bodies,Saharan countries are reviewed. Six of the development agencies, and national and in-countries are Anglophone (Kenya, Lesotho, ternational educational organizations. ByMauritius, Swaziland, Uganda, and Zambia) offering concrete proposals for improvingand six Francophone (Chad, Guinea, Mada- the quality of public examinations, and bygascar, Mauritania, Rwanda, and Togo). The focussing on the close interrelationshiptwo remaining countries are Cape Verde and between formal assessment, teaching andEthiopia. Public examinations are offered learning, it helps pinpoint the way to rais-in virtually all of the countries at the end of ing the level and the quality of education ofprimary, lower-secondary, and upper- pupils in Sub-Saharan Africa.secondary school.

Procedures for funding examinations; forconstructing, administering, and scoringpapers; and for reporting results in each

Ismail SerageldinDirectorTechnical DepartmentAfrica Region

v

Preface

The studies synthesized in this report to deepen and extend the studies. Follow-originated from the emphasis on improve- ing consultation, fourteen countries agreedment in educational quality in the World to participate in a set of studies under theBank's policy paper, Education in Sub-Sa- terms of reference. Public examination sys-haran Africa, published in January 1988. tems in six Anglophone countries (Kenya,This emphasis was highlighted by twelve Lesotho, Mauritius, Swaziland, Uganda, andAfrican Ministers of Education at the first Zambia), six Francophone countries (Chad,plenary meeting of the Donors to African Guinea, Madagascar, Mauritania, Rwanda,Education (DAE), established in the same and Togo) and two other countries (Capemonth to support priority educational de- Verde and Ethiopia) were investigatedvelopments. When the DAE Task Force met The studies were started in early 1989in June 1988, a Working Group on School under AFTED management, with Bank andExaminations (WGSE) was also established, Irish Government funding. Ireland agreedin recognition of the important role exami- to act as lead donor, operating through thenations can play in quality improvement. Irish Aid Agency, Higher Education for De-

The World Bank Education and Train- velopment Cooperation (HEDCO). An ini-ing Division of the Africa Technical Depart- tial model study was carried out in Swazi-ment (AFTED), in assuming responsibility land. Studies of examination systems in thefor developing appropriate activities to fur- six Anglophone countries and in Ethiopiather quality improvement, then prepared were carried out under the direction of theterms of reference to undertake studies on ERC, Dublin; examination systems in Fran-examinations in primary and secondary edu- cophone countries and in Cape Verde werecation in Sub-Saharan Africa. The main ob- studied by Management Planning and Re-jectives of the studies may be summarized search Consultants (MPRC), Bahrain. Anas follows: important feature of these studies was the(1) to improve educational quality in a cost- active participation of counterparts nomi-effective way through adjustment of inputs nated by Ministries of Education (MOE). Inrelative to examination systems addition, lead donor Ireland hosted periodic(2) to help develop institutional capacity in meetings of the WGSE to advance the imple-Sub-Saharan countries accordingly. mentation process. Progress reports were

Five studies (funded by the Bank's Eco- presented at DAE Task Force meetings. Thenomic Development Institute (EDI) and the findings of this synthesis report were dis-Irish Government), completed in Fall 1988 cussed at a November 1990 World Bank-by the Educational Research Centre (ERC), sponsored seminar in Killiney, Dublin, at-Dublin, were discussed at a seminar on Us- tended by examination officials from eaching Examinations and Standardized Testing of the fourteen countries and representativesto Improve Educational Quality in Lusaka, of donor agencies.Zambia in November 1988. At this semi- This synthesis report is based on: (1) annar, AFTED presented its terms of reference analysis of existing examination systems;

vii

(2) diagnosis of qualitative problems; and Preparation of the series of studies on(3) assessment of existing institutional ca- Using Examinations to Improve Educationpacity. The report draws also on research was managed by James McCabe, Principalevidence from work undertaken in Western Education Planner, Education and Trainingas well as African countries to form an as- Division, Africa Technical Department of thesessment of examination practice in Africa World Bank.and to suggest guidelines for the construc- Individual country studies were pre-tion and administration of examinations that pared in collaboration with Ministry of Edu-improve the quality of education. cation authorities in each country, by the

following principal authors:

1. Ethiopia: R. Reilly, M. O'Donoghue, V. Greaney2. Kenya: S. McGuinness, M. O'Donoghue, A. Yussufu, M. Kithuke3. Lesotho: J. McCabe, E. MacAogain, T. Kellaghan4. Mauritius: N. Baumgart, M. O'Donoghue5. Swaziland: T. Kellaghan, J. McCabe, S. Sukati6. Uganda: J. Sheehan, S. McGuinness7. Zambia: T. Kellaghan, M. Martin, J. Sheehan8. Chad: A. Brimer, J. Hosman, D. Ouman Hamid9. Guinea: M Chaibderraine, I. Sankhon

1 0. Madagascar: N. Constantine, J. Hosman, Mr. Rakoto, et al.11. Mauritania: M Chaibderraine, M. El Hafed Ould12. Rwanda: A. Brimer, J. Hosman, D. Kayinamura, E. Munyantwali13. Togo: N Constantine, A. Sewa14. Cape Verde: F. Oliveira, 0. Carvalho

The authors are indebted to Stephen MacAogain, and Ingvar Werdelin for com-Heyneman for his input into the de- ments on an earlier draft; and to Thomassign stage of the studies; to Marlaine Poole, Alicia Hetzner, and Michael MatovinaLockheed, George Madaus, Eoghan for preparing the report for publication.

viii

Acronyms for Public Examinationsand Examination Authorities

BEPC Brevet d'etudes du premier cycle. External examination taken at end of first cyclesecondary (four years) in Togo, in Guinea, and in Chad.

CEE Elementary certificate, taken at the end of primary school, Mauritania.CEP Certificat defin d'etudes primaires. Primary-school leaving examination, Rwanda.CEPD Certificat de fin d'etudes de l'enseignement du premier degre External certificate

examination at end of primary; also admission examination to secondary school,Togo.

CEPE Certificat d'etudes primaires elementaires. External examination taken at end ofprimary school in Madagascar, Chad.

CEPEA Certificat d'etudes primaires 6Mementaires. External examination taken at end of

primary school in Chad, for Arabic-speaking students.CFE/FP1 Certificat defin d'etudes de laformation professionnelle du niveau 1. External

examination taken at end of first two-year vocational training period (Level I) inMadagascar.

CFE/FP2 Certificat defin d'etudes de laformation professionnelle du niveau 2. Externalexamination taken at end of second two-year vocational training period (LevelII) in Madagascar.

CFEPCES Certificat de fin d 'etudes du premier cycle de I 'enseignement secondaire.External examination taken at end of first cycle of secondary school in Madagascar.

CPE Certificate of Primary Education, Mauritius.DEC Director of Examinations and Concours, Togo.ESLCE Ethiopian School Leaving Certificate Examination.HSC Higher School Certificate, Mauritius.KCPE Kenya Certificate of Primary Education, taken at the end of the eight-year

primary cycle.KCSE Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education taken at the end of the four-year

secondary cycle (introduced in 1989).KNEC Kenya National Examinations Council.MES Mauritius Examination Syndicate.PC Primary Certificate.PLE Primary Leaving Certificate.SC School Certificate, Mauritius.SEC Service of Examinations and Concours, Chad.UACE Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education.UCE Uganda Certificate of Education.UCLES University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate.UNEB Uganda National Examinations Board.

ix

Contents

1. SUMMARY 1

2. THE NEED FOR REFORM IN AFRICAN EDUCATION 5Growth in Education 5Concern with Quality 6Strategies to Improve Education 7Examinations and Reform 8

Effects of Examinations on Curricula 8Quality of Examinations 9Role of Examinations in Reform 11

3. THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEMS OF FOURTEEN COUNTRIES 15Countries in the Study 15Current Size and Participation Rates of Educational Systems 16Concern with Quality of Provision 16Scarcity of Places 18Repetition 18Dropout 19Teacher Quality 20

4. PUBLIC EXAMINATIONS 23Tradition 23Titles and Descriptions of Examinations 23Size of Examination Enterprise 24Setting of Examinations 24Use of Aptitude Tests 24School-based Components of Examinations 26Scoring 27Technology 28Functions of Examinations 28

Selection 28Certification 29Accountability 30

Performance 30Examination Repetition 32Governance and Administration 33Localization of Examinations 33Funding 34

Fees 34

Security 35Feedback 36

Comparisons among Schools/Districts 36Analysis of Results 37Timeliness 37

Challenges to Examination Results 37Outside-School Tuition 38

5. ISSUES IN EXAMINATIONS AND ASSESSMENT 39Expanding Enrollments 39Resources for Examinations 40Effects of Examinations on Curriculum and Teaching 40Reducing the Burden of Examinations and

Introducing School-based Assessment 42Use of Multiple-Choice Tests and Their

Associated Technology 44Validity 45Accountability 47Language of Examination 48Comparability of Performance 48Quotas 49

6. USING EXAMINATIONS TO IMPROVE EDUCATION 51Action Plans 52

Administration 52Technical and Training Requirements 55Equipment 56Construction/Rehabilitation 56Cross-National Cooperation 56

Improving Assessment in Public Examinations 57Anticipating Problems and Undesirable Effects 60Conditions to Improve the Administration of Examinations 62

Examination Authority 62National Cooperation 63International Cooperation 63Number and Format of Public Examinations 64Formal Training 64

7. CONCLUSION 658. REFERENCES 679. APPENDICES 73

National Education Systems 73Titles and Descriptions of Examinations 74Kenya Certificate of Primary Education: 80Sample Essay and Marker's Comments 81

1 Summary

This Synthesis Report summarizes data Students in virtually all of the systemsand information from a set of studies un- take public examinations at the end of pri-dertaken in: mary, first cycle secondary and second cycle

(1) Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritius, Swazi- secondary school. Candidates for primary-land, Uganda and Zambia; school leaving certificate examinations in(2) Chad, Guinea, Madagascar, Mau- most countries far exceed those taking sec-ritania, Rwanda, and Togo, and ondary school examinations. Countries in(3) Cape Verde and Ethiopia. Francophone areas tend to require their stu-

It outlines the findings, issues and rec- dents to take more formal examinations thanommended improvements from the four- those in Anglophone areas; most often theyteen individual studies undertaken on pri- also offer term, end-of-year and concoursmary and secondary school examinations. (competitive selection) examinations.

Considerable reliance has been placed Setting of examinations seems a ratheron public examinations in African educa- haphazard exercise, with some notable ex-tion as a means of ensuring that teachers ceptions. In some instances, a final selec-and students cover a common curriculum, tion is simply made from a pool of ques-and accordingly as a particularly effective tions submitted by teachers. Most of theinstrument for raising academic standards. examinations reviewed show serious weak-However, it has also been argued that while nesses. Very little use is made of school-public examinations may help raise aca- based assessment.demic standards, they may also give rise to Most scoring (or correction) of public ex-problems in the educational system. The aminations is carried out by teachers, thoughfindings of the fourteen studies confirm this a relatively small number of systems use op-point. tical scanning and/or computer equipment.

Two countries (Ethiopia and Swaziland)Findings have had to abandon optical scanning.

The important issue of marker reliabilityPublic examinations have three main does not appear to have been addressed in

functions: certification, selection and ac- most countries, though it should be, givencountability. While most examinations the seriousness of the decisions made on theserve all three to some extent, selection is basis of examination performance.undoubtedly the main function. The para- Pass rates tend to be low. In some in-mount importance of selection is reflected stances the pass rate is determined by thein the large numbers each year who are not number of places available at the next high-promoted to the next highest level of the est level of schooling. Data on pass rateseducational system. There is also a grow- should be interpreted with caution. For ex-ing tendency to use a single examination ample, quota systems are sometimes usedfor purposes of both selection and certifica- to attain national objectives such as equalitytion of level of attainment. of male and female pass rates. Pass marks

from region to region within countries may

1

vary in an effort to ensure regional equality Issuesof opportunity.

Public examinations undoubtedly exert To date, not enough attention appears toenormous pressure on activities in schools. have been focused on the educational con-Teachers tend to gear teaching to the tests sequences of existing examination systems.to be taken and to ignore material not fea- However, the likely impact of changingtured in such tests, even if it is mandated in present systems needs to be studied care-the official curriculum. fully, given the experience with public ex-

Most of the questions in public examina- aminations in non-African settings.tions tend to measure students' ability to It must be appreciated that however ex-recall facts. Relatively little attention is given cellent a test is in terms of validity, reliabil-to higher-order cognitive skills such as those ity, and efficiency, the pressure on studentsinvolved in synthesis or evaluation. Exami- to perform will remain substantially un-nation content tends also to be academic in changed while lack of places at the next high-nature; life outside of school seldom features est level persists. Where such bottlenecks ex-in examination questions. In most countries, ist, it is naive to think that teachers will notparticularly those of Francophone tradition, attempt to gear teaching to testing, or thatexaminations are of the written essay or oral students will not seek outside help to enabletype. Other forms of assessment (multiple- them to advance to the next level.choice, project, practical, or aural) are less In this context also, it must be empha-frequently used. sized that the high repetition rate attribut-

Whereas Ministries of Education admin- able to "failure" may represent a seriousister public examinations in Francophone waste of scarce educational resources.countries, independent or semi-independent The need for definition and implemen-examination boards generally fulfil this func- tation of language policies by governmentstion in Anglophone countries. In a small is urgent, and in that regard, decisions arenumber of countries, universities have re- required on the most appropriate languagessponsibility for the secondary-school leav- to be used in public examinations. In mosting examination. countries the present emphasis on French

For examinations run by Ministries of and English has probably contributed to lowEducation, fees are generally not charged at pass rates.the primary level. However, Anglophone Clearly, practical subjects and school-countries are more likely to charge fees. based assessments will tend to receive littleMost systems charge fees for secondary emphasis until they are incorporated intoschool leaving examinations; fees can be very public examinations. These types of assess-high in some cases. ment, however, are time-consuming, expen-

Concern over security is a conspicuous sive, and difficult to moderate.feature of most systems. Legal provision for Efforts to localize (or nationalize) exami-breaches of security vary. nations, following long experience with sys-

Examination results are seldom used to tems such as those offered by the Univer-provide useful feedback to schools, admin- sity of Cambridge Local Examination Syn-istrators or curriculum bodies. Thus, a good dicate, run the risk of undermining publicopportunity to effect change is little ex- confidence in the examination system.ploited.

2

likely impact of such tests on the vast ma- should be taken of factors other than teach-jority of students who may not proceed to ing effort.the next highest level must be considered. 6. The number of public examinations

Publication of school results and national should be reduced to help diminish repeti-rankings are designed to provide "incentive tion and dropout rates and the inevitableinformation," a form of public accountabil- sense of failure experienced by students.ity expected to motivate schools. Cogni- 7. The amount of time teachers spend onzance should also be taken, however, of the testing and preparing for public examina-many factors (e.g., socio-economic) other tions should be lessened to provide morethan teaching effort and quality elements time for teaching.that affect examination performance. 8. Detailed, timely feedback should be

Efforts to modernize the processing of provided to schools on levels of pupil per-examination data should take into account formance and areas of difficulty in publicthe level of technical support available and examinations.particularly the extent to which foreign cur- 9. Predictive validity studies of public ex-rency is likely to be available for procure- aminations should be conducted.ment of required equipment, materials, and 10. The professional competence of exami-expertise. nation authorities needs to be developed, es-

pecially in test construction.Recommended Improvements 11. Each examination board should have a

research capacity.It is clear that a public-examination sys- 12. Examination authorities should work

tem can exert a highly positive influence not dosely with curriculum organizations andonly on the nature of assessment, but much with educational administrators.more importantly on the nature of teaching 13. Regional professional networks shouldand learning. While examinations cannot be developed to initiate exchange programschange the educational system, they can be and share common interests and concerns.made to reflect the objectives of curriculum An example is the Association of Heads ofdevelopers and educational planners. The Institutions Responsible for Examinationsfollowing recommendations are offered: and Education Assessment in East and

Southern Africa.1. Examinations should reflect the full cur- 14. A post-graduate degree course shouldriculum, not merely a limited aspect of it. be established in an African country for ex-2. Higher-order cognitive skills should be amination authority personnel.assessed to ensure they are taught.3. Skills to be tested should not be lim- Finally, while implementation of theited to academic areas but should also be above can effect improvement, it should berelevant to out-of-school tasks. recognized that other factors such as avail-4. A variety of examination formats ability of places, language of instruction andshould be used, including written, oral, au- assessment, amount and quality of literacyral, and practical. materials and quality of teaching, together5. In evaluating published examination with examinations, will play critical roles inresults and national rankings, account improving the quality of education.

3

2 The Need for Reform in African Education

After a period of massive expansion, edu- tween 1960 and 1983, the number of pri-cation in many African countries has, dur- mary-school pupils in Sub-Saharan Africaing the last decade, encountered a series of increased by well over 400 percent, fromproblems. While demand remains high, 11.85 to 51.35 million. Gross enrollment ra-progress towards universal provision at the tio over the same period rose from 36 to 75primary level and expansion at the second- percent (World Bank 1988). At secondaryary level has slowed, mainly because of a level, the increase, at 1,400 percent, was evenshortage of money. More limited financial greater. Student numbers rose from .79 toresources than had been available in the past 11.12 million and gross enrollment ratio fromare being spread more thinly over increas- 3 to 20 percent (World Bank 1988).ing numbers of students (Fuller 1986; WorldBank 1988). Given this situation, the choice Despite massive expansion, the discrep-for policymakers, for at least the remainder ancy between provision at primary and sec-of this century, would appear to lie either in ondary levels remained great. The percent-increased efficiency in the use of existing age of students in Sub-Saharan countriesresources or in the acceptance of declining who transferred from the last grade of pri-standards of access, equity, and scholastic mary school to the first grade of secondaryachievement (Windham 1986). general education in 1983 was 43 (World

Bank 1988). This figure has a particularIn this chapter, we outline some current relevance to examinations because they are

concerns about education in Africa. Pro- used to control the flow of students at thisposals to address these concerns relate to a juncture, as well as at other points, in thevariety of actions-the provision of books educational system. The success or failureand equipment, teacher training, enlisting of a student at any of the important selec-the support of children's homes, and im- tion points in the system can have very se-proving the nutritional status of children. rious consequences for his or her educationalOur concern is with the possible role of and occupational future. It is precisely be-public examinations, a well-established fea- cause of their role as gatekeepers in educa-ture of African educational systems, in im- tional systems, in that the number of placesproving educational achievement. diminishes as one ascends the educational

hierarchy, that examinations have acquiredGrowth in Education the importance they possess in African coun-

tries.Africa has the lowest primary, second-

ary, and university enrollment rates of any Educational growth in Africa has slowed,wforld region (Nafziger 1988). This is so and in some countries has stagnated or ac-despite the fact that educational systems tually declined, in recent years. This hasthroughout the continent expanded rapidly been attributed largely to poor economicin the 1960s and 1970s. For example, be- conditions that were aggravated, in the first

5

instance, by the oil crisis in the 1970s and, for economic reasons (see, for example,more recently, by increasing levels of debt- Swaziland, Ministry of Education 1986; Tanrepayment obligations (Windham 1986). To- 1985; Zambia, Ministry of Education 1977).tal public expenditure on education in Af- Attempts to meet these commitments canrica declined from $10 billion in 1980 to $8.9 be expected to contribute to the growth inbillion in 1983, while per-pupil expenditure, numbers attending school.both in absolute terms and as a proportionof gross national product, declined mark- Concern with Qualityedly at both primary and secondary levels(World Bank 1988). Side by side with the problems of de-

creased financial resources and stagnatingThere are a number of reasons why the enrollments, commentators in a number of

educational systems of Africa are particu- African countries, as in countries elsewherelarly vulnerable to economic circumstances throughout the world (see Heyneman andand the conditions of government finances. White 1986), have expressed concern aboutFirst, the role of the public sector in financ- a decline in quality of the education beinging education is a major one. In 1983, for offered in schools (see, for example, Evalu-example, 85.4 percent of primary students ation Research of the General Educationand 85.1 percent of secondary students were System in Ethiopia - ERGESE, 1986; Kellyin public schools. The proportion for Fran- 1991; Zambia, Ministry of Education 1977).cophone countries was larger than for An- Although many countries now collect edu-glophone countries (World Bank 1988). cational statistics, for example on participa-Second, state subsidies are large, as fees for tion rates, on a fairly routine basis, evidencepublic education recover only 5.7 percent of relating to the quality of provision or ofthe cost of primary education, 11.4 percent output is more difficult to come by. Thereof the cost of secondary education, and 1.9 is some evidence of decline in the quality ofpercent of the cost of higher education. provision. Supplies of key inputs, especiallyThird, because of the low level of gross books and other learning materials, are re-national product (GNP) in many African ported to be critically low in many coun-countries, the cost of public education for tries (World Bank 1988). Concern has alsoone student as a percentage of per capita been expressed about decline in quality ofGNP is higher in Africa than in any other output (as measured, for example, by stu-region (Mingat and Psacharopoulos 1985; dent achievement). Such concern is basedNafziger 1988; Unesco 1990, Table 19). for the most part on impressionistic evi-

dence, evidence, of course, that should notAlthough resources are limited, and even be ignored. The available empirical evi-

diminishing, school-age populations are in- dence on a decline in standards, however,creasing rapidly. During the past twenty is far from satisfactory. While the Interna-years, over 50 million new pupils enrolled tional Association of the Evaluation ofin school throughout the continent, and it is Eduactional Achievement (IEA) studies ofexpected that the number that will become achievement in mathematics in Nigeria andeligible in the next twenty years will be 110 Swaziland have been cited as evidence ofmillion (Windham 1986). In addition, the declining standards (World Bank 1988, p.demand for educated manpower to support 33), these studies do not tell us anythingeconomic growth is likely to grow, putting about change as they were carried out onpressure on governments to expand educa- only one occasion.tional facilities. Moreover, many countriesmade commitments following independence Examination performance over time is ato provide education for social as well as possible source of evidence regarding chang-

6

ing standards (see Kahn 1990). However, Hallak 1990; Heyneman 1985,1987; Mingatthe characteristics of students taking an ex- and Psacharopoulos 1985). The World BankamLnation as well as the standard required (1988) has shown a particular interest in thisto aLchieve a particular grade in an examina- problem and has identified three major ar-tion, particularly if a predetermined propor- eas to be considered in the formulation oftion of students is assigned to each grade, policy:may vary from year to year. Thus, knowl-edge of the numbers achieving particular (1) Adjustment to current demographic andgrades over time does not permit unambigu- fiscal realities, that will require: (a) diversi-ous inferences about changes in standards. fication of sources of finance (in the form ofIt is worth noting, however, that in Swazi- increased cost sharing in public educationland, pass rates increased on the Cambridge and encouragement of nongovernmentalOverseas School Certificate (that was con- suppliers of educational services); and (b)trolled by the Cambridge Syndicate) from unit-cost containment, that will be of greater36 percent in 1980 to 54 percent in 1988. importance than cost sharing in countries inThere was an even greater increase in the that the scope for cost sharing is negligiblepercentage of first and second-class passes. or non-existent. One aspect of the organiza-It is of interest, in the context of the present tion of education that could contribute toreport, that the improvements have been at- unit-cost containment would be a reductiontributed to strategies (that were implemented in the amount of grade repetition.between 1984 and 1987) designed to increasethe competence of inspectors and teachers (2) Revitalization of the existing educationalin the assessment of students (Lulsegged infrastructure, that will include: (a) a re-1988). It is also of interest that the nature of newed commitment to academic standardsstudent assessment in Swaziland, even be- (principally by strengthening examinationfore the efforts to improve it, may have dif- systems); (b) restoration of an efficient mixfered from that in other countries. An analy- of inputs in education (especially increasingsis of IEA data, that were collected in Nige- the amount of textbooks and other learningria and Swaziland in 1980-81, indicates that materials); and (c) greater investment in thetime spent by teachers in monitoring and operation and maintenance of physical plant.evaluating student performance was posi-tively associated with achievement in Swazi- (3) Selective expansion, that will be viableland but not in Nigeria (Lockheed and only after measures of adjustment and re-Kormenan 1989). The Swazi data, however vitalization have begun to take hold andone interprets them, do seem to contradict will involve: (a) renewed progress towardsthe general perception of declining standards the long-term goal of universal primaryof achievement in African schools, under- education; (b) the development of alterna-lining the need for more systematic empiri- tive ways of delivering educational servicescal evidence relating to standards of achieve- (including distance education); (c) trainingment over time. for those who have entered the work force

in job-related skills; and (d) research andStrategies to Imrprove Education postgraduate education.

Because of the perceived need in many In a document adopted by the Worldcountries not jutst to maintain standards of Conference on Education for All, that wasaccess, equity, and academic achievement convened jointly by the executive heads ofbut to improve them, a number of strategies the United Nation's Children's Fundhave been considered for educational reform (UNICEF), United Nations Development(see Fuller 1986; Fuller and Heyneman 1989; Programme (UNDP), Unesco, and the World

7

Bank; and was held in Jomtien, Thailand, were written verbal and reading comprehen-from March 5 to 9, 1990, the emphasis on sion tests. This did not seem to make muchbasic education and the achievements of stu- sense given the tasks that gunners were sup-dents who receive that education is again posed to do, such as maintaining, adjusting,evident. Article 3 of the World Declaration and repairing guns. On examining whaton Education for All (1990) states that "Basic went on in training, the researcher foundeducation should be provided to all children, that classes consisted of lecturing and dem-youth and adults" (p. 4). Recognizing that onstrating how to use equipment, ratherthe provision of such education is only than having students do the actual tasksmeaningful if people actually acquire useful themselves. He then designed performanceknowledge, reasoning ability, skills, and tests in that students were required to dem-values, Article 4 of the Declaration states that onstrate competence by, for example, remov-the focus of basic education must be "on ing and replacing the extractor plunger on aactual learning acquisition and outcome, 5 /38-inch anti-aircraft gun. Few of the stu-rather than exclusively upon enrolment, dents could perform the tasks.continued participation in organized pro-grams and completion of certification re- New students soon found out what thequirements" (p. 5). new performance tests were like and began

practicing the assembly and disassembly ofExaminations and Reform guns. The instructors also moved from lec-

turing to more practical work with guns andThe idea that examinations may have an gun mounts. At the end of the course, stu-

important role to play in effecting a reform dents performed very much better on thein education in developing countries arises performance tests than students who hadfrom the belief that they exercise a strong experienced the older instructional method.influence on what is taught in schools and Further, the predictive validity of the verbalcan be used as instruments of accountabil- and reading tests dropped while the valid-ity. It can also be argued that they provide ity of the mechanical aptitude and mechani-a relatively simple means of controlling a cal knowledge tests improved.system in that resources for other means ofcontrol, such as school inspection and The interesting point of this anecdote isteacher training, are limited and in that stu- that no attempt was made to change the cur-dents attend private schools and non-formal riculum or teacher behavior. The dramaticeducational establishments as well as pub- changes in curriculum and achievement camelic schools. about solely through a change in testing.

Effects of Examinations on Curricula In the day-to-day workings of schools,the effects of assessment on curricula and

What evidence do we have that exami- on student achievement are not so dramatic.nations affect curricula and teaching in However, there can be little doubt that ex-schools? Perhaps the most striking example aminations, to which high stakes are at-of how an assessment procedure can affect tached, exert considerable influence on whatthe content and skills covered in a curricu- goes on in schools (Fredericksen 1984;lum is to be found in an anecdote of a per- Madaus and Kellaghan, in press). Thoseson who carried out research on the selec- involved in an educational system that hastion and training of U.S. naval personnel such examinations will attest to the fact thatduring the second World War (Fredericksen the topics that teachers and students attend1984). This person found that the best tests to in class and in study are the topics thatfor predicting grades given by instructors are likely to appear on examination papers.

8

One commentator has concluded that since many examinations contain very little refer-examinations represent "the ultimate goal ence to the everyday life of students outsideof the educational career, they define what the school, dealing with scholastic topics andare the important aspects of a school cur- applications for the most part, rather than,riculum and they dictate to a large degree for example, trying to find out if a studenttheA quality of the school experience for both can use money in the market place. Fifth,teacher and student alike" (Little 1982). the quality of actual items used in tests is

often poor (see Cambridge Educational Con-If the examinations are good, this might sultants 1988; ERGESE 1986; Kelly 1991:

be a satisfactory situation. If the objectives Lesotho 1982; Little 1982; Myeni 1985;and skills to be measured are carefully cho- Oxenham 1983).sen and if the tests truly measure them, thenthe goals of instruction will become explicit If schools gear their teaching to suchand well-defined targets for teachers and examinations, then they are unlikely to bestudents on that they can focus their efforts. very successful in developing in theirFurthermore, the examinations will provide students the kind of knowledge and skillsstudents and teachers with standards of ex- that most people would regard aspected achievement. Given this situation, desirable-skills of observation, problemthere should be no reason why students identification, problem-solving andshould not work for marks, and good rea- reasoning, and particularly knowledge andsons why they should ( Fredericksen 1984). skills that can be applied in the day-to-dayIn practice, however, examinations may lack life of the many students who will have only"construct validity" or, for other reasons, minimal exposure to formal education (seemay not meet the high standards that would National Commission on Testing and Publicjustify teachers and students devoting their Policy - NCTPP, 1990; Nigam 1982). Rather,efforts to performing well on them. the effect of such examinations, as was

observed in Ghana, is likely to be "to supportQuality of Examinations and encourage rote-memorization, routine

drilling, bookishness" (Brooke andEvidence from many countries through- Oxenham 1984, p. 158). Indeed, the view

out the world over the past century sug- was expressed in a government report ingests that public examinations suffer from a Lesotho (1982) that many problems withvariety of defects (Madaus and Kellaghan, curriculum and instruction seem to stemin press). In African countries, defects of fromexaminations have been pointed out on nu- ... .the inordinate emphasis givenmerous occasions, in both official and unof- to the preparation for terminalficial reports. First, most examinations, at examinations which undermines theboth primary and secondary level, are lim- attainment of certain objectives thatited to pencil-and-paper tests and so ignore are critical to the country's economica variety of skills that cannot be measured development...in this way. Second, examinations empha- The JC [Junior Certificate]size the achievement of scholastic skills (par- examination heavily emphasizes theticularly language and mathematics at the accumulation of factual knowledgeend of primary schooling) paying very little and neglects general reasoning skillsattention to more practical skills. Third, in and problem-solving activities" (p.most examination questions, the student is 94).required to recall or recognize factual knowl-edge, rather than to synthesize material or In Ghana, Brooke and Oxenham (1984)apply principles to new situations. Fourth, have noted that teachers tend to neglect non-

9

examination subjects even though the offi- labus, only six of 39 authors named werecial timetable might require that allocation African, and only three of these were Westof time be adhered to strictly. Teachers even African. As well as studying Shakespeare,pick topics within subjects according to students had the option to study the poetrywhether they judge them as likely or not to of Chaucer, John Donne, and Georgeappear in examinations. The same phenom- Herbert. The Senegalese Baccalaureat of-enon has been observed in Uganda, where fered examinations in ten languages, noneneglect of the teaching of practical skills, es- of them African (Bray, Clarke, and Stephenspecially at the primary level, and the conse- 1986).quences of this for students on leavingschool have been noted (Uganda, Ministry While examinations at the primary levelof Education 1989). In such situations, the are controlled locally in all countries, for-effect of examinations can be inhibiting, serv- eign influences are to be found in curriculaing to distort or prevent learning rather than and examinations at this level also. In ato promote or facilitate it (Heyneman and study of the national primary-certificate ex-Ransom 1990; Little 1990). aminations of ten Anglophone countries,

Hawes (1979) found that, in 1978, five usedThe use of examinations that were set only the English language, a further four

and marked outside of African countries used English in all papers except in the oneprobably contributed to the perpetuation of examining the local language, and only onethe situation in that examinations took little used a local language as the main examin-cognizance of the conditions in that students ing language. Reliance on English in theselived and were likely to live in the future cases invariably reflects the fact that there(Kellaghan 1991). As late as 1981, the school- are several, in some cases a great many, localleaving certificate examinations in seven languages, none of that is spoken through-African countries were set and marked by out the country. In linguistically heteroge-the University of Cambridge Local Exami- neous situations, learning and being exam-nations Syndicate (Bray, Clarke, and ined in a metropolitan language is perceivedStephens 1986), a situation that has now to favor no particular group. Furthermore,changed. Since preparation for examinations the use of metropolitan languages, such aswas important in schools, we might expect English and French, is seen as conferringthat the examinations contributed signifi- benefits, particularly on those who are likelycantly towards the maintenance of a west- to proceed to third-level education (Eisemonern academic education. The examinations 1990). However, the advisability of teach-also, of course, contributed to the mainte- ing and examining through English ornance of standards and acceptance of certi- French students who have poor proficiencyfication at the international level, important in the language and who rarely if ever useconsiderations in developing countries. the language outside school is something

that has been questioned many times. Stu-The setting up of local examination dents with limited knowledge of a language

boards did not result in a sudden break with will inevitably be handicapped in the ac-the traditions of the colonial system in the quisition of knowledge and skills presentedcontent of curricula or examinations or in in the language as well as in their ability tomodes of examining. For example, the West demonstrate in examinations the knowledgeAfrican Examinations Council was set up in and skills they have acquired (Eisemon1951 to serve the Gambia, the Gold Coast, 1990).Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and later Liberia, as alocal independent body. However, in its A further problem with many external-1980 Advanced-level English Literature syl- examination systems in Africa is that their

10

pr-mary use is to control the flow of stu- tributing to the problems, while others see adents through the educational system. This role for examinations as part of a possibleuse is understandable, and the selection solution. Those who perceive examinationsfunction of examinations will no doubt con- as part of the problem cite the evidencetinue to be important as long as there is a considered above concerning the inadequacyshortage of places at higher levels of educa- of examinations. If examinations serve totional systems. However, there are a num- distort or prevent desirable learning, it mightber of dangers inherent in focussing on the not seem unreasonable to conclude thatuse of examinations for selection. First, the public examinations should be abolished.examinations will tend to be geared to the Together with this view, it is usually pro-needs of pupils who are doing relatively well posed that a system of school-based assess-in the systerm while the needs of lower ment should be installed in place of exter-achieving students may not be adequately nal examinations.met. And, second, it is likely that the ex-amriinations will focus on academic topics. An alternative view is that since there isIn the early 1970s, the ILO (1972), in a com- a lack of the resources that would be neededrment that could have been applied to the to introduce alternative assessment proce-educational systems of many African coun- dures, for example school-based assessment,tries, noted that, in Kenya, most primary cur- to the educational systems of most Africanricula and examinations ignored the needs countries and since the need for selectionof terminating students. will continue in the foreseeable future, it

would appear to be unrealistic to talk of dis-To help avoid such undesirable effects pensing with present examination systems.

in constructing examinations, it is important This view also recognizes that examinationto keep clearly in mind the need for certify- systems in Africa are perceived by many toing the achievements of all students, as well be relatively fair and impartial and that theyas the need for selection. Further, cognizance also serve to legitimate the allocation ofshould be taken of the motivational effect of scarce educational benefits. Before an alter-examinations on students and the influence native system could be introduced, it wouldof examinations on what is taught and em- be necessary to demonstrate that it couldphasized in schools. Examinations that are fulfil this task equally well. It is also ar-designed for only the top 20, 30, or even 50 gued that examinations, if properly de-percent of students and the curricula that signed, could have a beneficial effect on theprepare students for such examinations are quality of education in schools. Because oflikely to be seen as irrelevant to lower- the high stakes associated with examinationsachieving students. in terms of student opportunities and teacher

accountability, changes in examinationsRole of Examinations in Reform would most likely be reflected in changes in

educational practice in schools. If theGiven the importance of public exami- changes involve improving the quality and

nations in educational systems, to an extent scope of examinations, these in turn shouldthat a school's success may be "judged result in improving the educational experi-strictly by the performance of its students in ences of students in schools (Heynemanthe examinations" (Fafunwa 1974, p. 193), it 1987; Heyneman and White 1986;is not surprising that the role of examina- McNamara 1982). In Little's (1984) words,tions has received particular attention in the examination improvements could help turncontext of the problems facing education in the educational system into one "which en-Africa today. For some observers, external courages, rather than stultifies, desirable out-public examninations are perceived as con- comes" (p. 228). Again, Little (1982) argues

11

that "the quality of the examination system and over time might even have importantitself can have a considerable impact on the effects on the economic performance of aquality of skill formation encouraged by the nation (Heyneman 1987). However, such aeducation system, that skills in turn could system could have serious and damaginghave a considerable impact on the inputs to effects on the educational experiences ofthe labor market" (p. 177). many students if it ignores the fact that for

many students-in fact the majority-learn-The possible role of examinations in edu- ing has to have utility beyond that of quali-

cational reform has been considered in a fying individuals for the next level of edu-number of policy documents. In the World cation (World Bank 1988). Thus, a procedureBank (1988) strategies outlined above, the that most efficiently selects students may beneed to strengthen examination systems in inadequate for certification purposes. Simi-the interest of raising academic standards is larly, a procedure that is adequate for certi-specifically mentioned in the context of re- fication is unlikely to be the most appropri-vitalizing the existing educational infrastruc- ate one for monitoring the quality of perfor-ture. Further, examination and assessment mance of a school or of the educational sys-systems could be rationalized and made tem in general.more efficient; this seems important at a timewhen numbers taking examinations are In considering examination reform, it isshowing large increases in many countries. important to bear in mind the different func-Again, assessment procedures could be used tions of examinations and the many possiblein a formative way to guide instructional effects of examination systems on schools,and learning processes in schools to reduce teaching, and learning. It is also importantdropout rates and grade repetition. In their to realize that in selecting the specific inno-important role in educational selection, ex- vations most likely to fulfill a country's re-aminations could contribute to greater effi- quirements, insofar as is possible, effectsciency in the educational system by identi- should be anticipated and judged as desir-fying students most likely to benefit from able or undesirable in the context of thefurther education. Finally, in future expan- general goals and aims of each country'ssion of educational systems, examination own educational system (Eckstein and Noahand assessment procedures could be as- 1988; Heyneman 1987). We shall return tosigned an important role in the provision of these issues in Chapter 5.feedback information to schools on studentachievement levels. They could also have Efforts to reform curricula and examina-an important role in ensuring comparability tions are already in evidence in a number ofof standards between school-based and non- countries. For example, a program of cur-school-based candidates, if non-school-based riculum reform has been carried out in Le-ways of delivering educational services are sotho. Syllabi in the core subjects (Sesotho,developed further. English, Science, Mathematics, Social Stud-

ies) have been designed and disseminated.The fact that systems of examinations and Syllabi comprise units, specific objectives,

assessment can be used for a variety of pur- suggested activities, skills and concepts toposes should not be taken to imply that a be learned by students, and resource mate-single system of examinations or assessment rials. Side by side with these activities, skillscan readily serve all purposes equally well. checklists for Sesotho, English, and Math-For example, an examination system that ef- ematics (Standards 1-3) and sample testficiently selects the pupils most likely to ben- question booklets in English and Mathemat-efit from further education might contrib- ics (Standards 4-6) have been constructed toute to the identification of a technical elite reflect the new curricula.

12

Initiatives in Kenya have been more ob- certificate examination although the infor-viously directed towards the use of exami- mation did not receive wide publicity untilnations to improve the quality of learning after the 1978 examination. The first full-in schools. In these initiatives, that have length newsletter was based on the 1978 ex-been reported by Somerset (1987, 1988), the amination results.content of the public examinations at the endof primary schooling was changed and a sys- Only limited information is available re-tern to provide feedback information to the garding the impact of these procedures onpublic and to schools was introduced. The school practice or student achievement. Atreform in the content of examinations in- the time he prepared his report, Somersetvolved the inclusion of a much broader spec- (1987) indicated that relevant data on teach-trum of cognitive skills than had previously ing methods and content had not been col-been included in examinations, skills de- lected. He did, however, provide informa-signed to measure comprehension and ap- tion on changes in the relative mean scoresplication, as well as skills that could be ap- of districts throughout the country betweenplied in a wide range of contexts, in and out 1976 and 1981. He attributed changes inof school. This was done in recognition of these scores between 1976 and 1979 mainlythe fact that examinations should not be con- to the impact of the incentive feedback sys-fined to the measurement of students' abil- tem. If that is correct, then the impact wasity to memorize factual information but negative since mean performances betweenshould also promote the teaching and learn- districts, that it had been hoped would nar-ing of competencies that would be useful row, substantially widened during the pe-not only to those who stay in school but riod. In the following two years, duringalso to the majority who would leave after which guidance information was available,the examination. Little (1984) has described the trend was reversed and some districtsthe changes between 1971 and 1979 in the in which mean scores had been relativelydistribution of items designed to test knowl- low improved their positions. It may beedge, comprehension, and application in the that guidance information contributed to thisCertificate of Primary Education in Kenya improvement, but any firm conclusionsas "dramatic," about the effects of any of the changes in

the examinations system are not possible onIn the feedback system in Kenya, lists of the basis of the available information.

schools were published that reported theoverall mean of the performance of students Since students' test performances on thein each school on the examination. Mean primary-certificate examination each yearstandard scores for each district in the coun- were converted to standard scores derivedtry were also published. This was described from a distribution with a mean of 50 and aas "incentive information." "Guidance in- standard deviation of 15, inferences cannotformation," based on an analysis of the per- be drawn about possible trends in studentformance of students nationally on indi- achievement over time. Yussufu (1989), how-vidual questions, was also provided in a ever, has stated that the performance of can-newsletter that was sent to schools. The didates on the Kenya Certificate of Primarynewsletter explained changes in the content Education Examination (KCPE), first intro-and skills covered in examinations, identi- duced in 1985, "'has, in general terms, shownfied topics and skills causing problems, and a steady consistent improvement." This con-suggested ways of teaching these topics and clusion is presumably based on changes inskills. The incentive information was first students' raw scores. Information about thepublished following the 1976 primary-school nature or extent of the changes, however, is

not provided.

13

Neither is information available on other will not necessarily make schools anypossible effects of the examination and re- more effective especially insofar asporting systems, though we might expect fostering outcomes like better healtheffects on, for example, retention, repetition, are concerned.and dropout rates in schools.

How precisely examinations might con-Eisemon, Patel, and Abagi (1987) observe tribute to the improvement of education in

that the introduction of new question items ways that everyone regards as desirable ison the primary-school leaving examination not clear. Is it, for example, necessary toin Kenya has not, in their opinion, changed build tests in accordance with cognitive theo-primary-school instruction "in ways in ries of the measurement of achievement, aswhich greater emphasis on problem solv- Eisemon and others suggest? While such aning, reasoning and explanation can be dis- approach might be helpful, though its limi-cerned." They stress the need to build ex- tations must also be recognized in light ofaminations in accordance with cognitive our poor understanding of the process oftheories of the measurement of achievement achievement measurement, it would hardlyif the examinations are to have a beneficial seem to be necessary. Insofar as we know,effect on school practice. They studied the no such theories guided the work of theimpact of examinations that had been con- person involved in the measurement of thestructed in accordance with such a theory performance of the young navy personnelon instruction and learning in a Nairobi pri- in Fredericksen's study (1984), describedmary school. The study is limited in its above. Even if construction of a test alongscope in a number of respects: it is confined certain principles is more likely to assist into one school; it deals only with health edu- student learning than a test that does notcation; and it was carried out under experi- follow those principles, we know very littlemental conditions. Thus the findings might about the mechanism that can translate ex-not apply in the normal circumstances un- perience of examinations and knowledge ofder which examinations are administered. results (that might be in the heads of stu-In some instances examination items assess dents, teachers, parents, or administrators)pupils' abilities to integrate existing and new into higher student academic achievement.knowledge. These items are explicitly related So long as that is so, we should be circum-to the competent performance of target be- spect in our recommendations about the usehaviors. Because of this deliberate structur- of examinations in the interest of raisinging of items, teachers' explanatory behav- student achievement. Actions based on de-iors and their emphasis on procedures to cisions taken on an a priori basis, and with-foster pupil understanding will improve. out the benefit of conceptual analysis andOn the basis of this study and of their con- empirical evidence, run the risk of being atsideration of reform efforts in Kenyan edu- best ineffective and at worst damaging. Be-cation, Eisemon and others (1987) conclude cause of this, we emphasize the need to con-that: sider possible problems and undesirable ef-

Psychometric manipulation of exami- fects that can arise when examinations arenation items in the absence of more used to direct the activities of teachers andresearch into instructional and cogni- students. We consider these problems intive processes may produce better Chapter 5 after we set out guidelines relat-tests and different teaching, but this ing to the improvement of examinations.

14

3 The Educational Systems of Fourteen Countries

Countries in the Study

In this report, we are concerned with the Table 2.1examination systems of fourteen African POPULATION, AREA, AND PER CAPITA GNP

countries. While many of these countries OF STUDY COUNTRIES, 1984experienced a variety of colonizers (Arab,Belgian, British, French, German, Italian, and Countries/ Population Area Per capitaPortuguese), they are sometimes categorized linguistic (millions) (thousands of GNP ($)in terms of the European language that in status square kms)

addition to local languages, is used in thecountry today. Using this criterion, six of Anglophonethe countries can be described as Anglo-phone (Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritius, Swazi- Kenya 19.5 583 310

land, Uganda, and Zambia); six as Franco- Lesotho 1.5 30 530phone (Chad, Guinea, Madagascar, Mauri- Mauritius 1.0 2 1,090

tania, Rwanda, and Togo); while two fall Sinto neither of these categories (Cape Verde, Swaziland 0.7 17 790Ethiopia). Uganda 15.0 236 230

Zambia 6.4 753 470At the outset, it has to be recognized that

great variation exists among (and oftenwithin) the countries that were studied for Francophone

this report. They range in population from Chad 4.9 1,284

less than a million (Cape Verde, Swaziland) Guinea 5.9 246 330

to over 40 million (Ethiopia). They also varyconsiderably in size, from less than 2,000 Madagascar 9.9 587 260

square kilometers (Mauritius) to 1,222,000 Mauritania 1.7 1,031 450square kilometers (Ethiopia). Eleven of the Rwanda 5.8 26 280

countries fall into the World Bank (1990)low-income category and three into the Togo 2.9 57 250middle-income category. Economic differ-ences are reflected in annual per capita GNP Otherthat ranges from $110 (in Ethiopia) to $790 CapeVerde 0.3 4(in Swaziland) and $1,090 (in Mauritius) Ca Vd.3

(Table 2.1). Even these figures may under- Ethiopia 42.2 1,222 110

estimate the extent of poverty in countries(Swaziland, Ministry of Education 1985). Source: WorldBank(1988),exceptforCapeVerde,forwhich

Since they are based on the monetary as- Unesco (1988) data for 1985 are used.sessment of activities related to the modernsector of the economy (that in many casesrelies heavily on foreign capital), they throw

15

little light on the standard of living of the countries exceeded 100. Figures over 100majority of the population who in all the percent can be attributed to the relativelycountries live in rural areas and are engaged high number of over-age pupils in primaryin the traditional sector of the economy, that school. The percentage of primary-schoolis mainly agriculture. students who were female ranged from a

low of 28 percent (Chad) to a high of 56Some of the countries are ethnically and percent (Lesotho).

culturally fairly homogenous; others arevery diverse. In some countries, for ex- Relatively small numbers of students ad-ample, a single language is spoken by most vance to secondary school. In all but threeof the population (Cape Verde, Lesotho, countries, the gross enrollment ratio at theMadagascar, Swaziland). In others, and this secondary level was less than 25 percent inis the more common situation, a diversity of 1986. Ratios at the secondary level exceededlanguages and dialects is in use (see World 20 percent in only five of our study coun-Bank 1988). tries (Lesotho, Madagascar, Mauritius,

Swaziland, Togo). Female participation wasDifferences among countries, that we will lower at the secondary than at the primary

again advert to when considering the edu- level. In nine of the fourteen countries, fe-cational and examination systems of the males constituted less than 40 percent of to-countries, are outlined here to draw atten- tal enrollment (Table 2.2). Lesotho is thetion to the fact that any general conclusions only country in which the number of femalereached in this report will have to be secondary-school students was greater thanadapted and interpreted within the context the number of males. The ratio of primaryof the particular circumstances of each indi- to secondary pupils was particularly largevidual country. in a number of countries, most notably

Rwanda (43:1), Uganda (12:1), Kenya (11:1),Current Size and Participation Rates of Zambia (9:1), and Lesotho (8:1). Clearly, forEducational Systems the vast majority of pupils, formal educa-

tion can be equated with primary school-Twelve of the fourteen countries in- ing.

cluded in our survey have either twelve orthirteen school grades altogether; one has Concern with Quality of Provisioneleven and one has fourteen. All the sys-tems are divided into primary and second- In recent decades, in each of the four-ary sectors. At the primary level, one coun- teen countries reviewed, the challenge fortry has five grades, seven have six grades, Ministries of Education was to providefour have seven grades, and two have eight schools and teachers for a dramatically in-grades. At the secondary level, one country creasing population. To date, the emphasishas four grades, four have five grades, five appears to have been on quantity rather thanhave six grades, and four have seven grades on quality, with the result that concern has(Appendix 1). been expressed with many aspects of the

quality of educational provision. In manyKenya has the largest number of pupils countries, teacher morale, for instance, ap-

in primary schools followed by Ethiopia, pears to be low. In Ethiopia, one studyUganda, Madagascar, and Zambia (Table reported that 40 percent of primary and 762.2). In 1986, the gross primary enrollment percent of secondary teachers would, ifratio of the countries varied from 29 percent given the opportunity, abandon the teach-(Guinea) to 115 percent (Lesotho) (Table 2.2). ing profession (ERGESE 1986). In LesothoThe gross enrollment ratio for six of the in 1988, 805 teachers and almost 55,000 pu-

16

pils had no shelter. In four of the fourteen In its policy study, Education in Sub-countries, class size has increased between Saharan Africa, the World Bank (1988) con-1983 and 1986. The pupil-teacher ratio in cluded that "... the safest investment in edu-Mauritania has gone from 24:1 (1970-71) to cational quality in most countries is to make5X.:1 (1986-87). Class sizes as large as 120 sure that there are enough books and sup-have been reported for Togo. In many in- plies" (p. 4). Other studies have shown that,stances, attendance rates are poor. Children in the case of developing countries, factorsmay be absent to help their parents either in such as school facilities, textbook availabil-the home or with planting or harvesting. ity, and teacher training account for a large

Table 2.2 portion of the variation in student achieve-ENMROLLMENT AND PARTICIPATION RATES ment (Eisemon 1988; Fuller 1987; Heyneman

and Loxley 1983).

Primary Secondary Resources that are lacking include suchbasic items as desks and chairs as in Togo.

Countries/ Gross Gross Many of the national reports commented onLngiuistic Number enrollment Number enrollment the lack of basic materials, most notably text-

atus (DODS) %femnale ratio (0COs) %femnale ratio books. In Madagascar, up to ten students

share a textbook. Over a sixteen-year pe-Anglophone riod, education in Guinea was conducted

Kenya 5124* 49* 96* 540* 40* 20 practically without any textbooks. Many

Lesotho 330* 56 115 39 60* 24 textbooks used in Cape Verde are producedMauritius 145 49 107 71 47 51 in Portugal, primarily for the home market,

Mand do not provide an adequate coverageSwaziland 142 50 105 32 50 42 of the official local syllabus. In Kenya andUganda 2204 45 68 187 33 9 Madagascar, as well as in other countries,

Zambia 1366 47 96 145 37 18 basic science equipment is either in shortsupply or, in some instances, is nonexistentin secondary schools.

Francophone

Chad 341 28 43 44 16* 6 Resource availability has implicationsGuinea 270 31 29 77* 25* 15* both for the format and functioning of pub-

lic examinations. In particular, practical ex-Madagascar 1492* 48 124 357* 44 42 aminations in subjects such as woodwork,

Mauritania 157* 40* 51 37* 30* 16 metalwork, and home economics requireRwanda 904 48 65 21 34 3 basic materials, not alone at examination

time but also during the school year. LackTogo 511 38 102 78* 24 21 of appropriate resources is one of the main

impediments to the introduction of more

Other appropriate forms of assessment (essay,Cape Verde 66* 49 108 7* 30* 14 practical, oral, and aural) in Ethiopia. Prob-

lems have been experienced in Chad andEthiopia 2884* 39 38 843* 39* 14 Swaziland, as well as in other countries, in

the acquisition of equipment for practical

Source: World Bank (1990). subjects.

* Updated in national report.

17

Scarcity of Places educational systems that cannot accommo-date all children of school-going age, repre-