'Use of Geotextile Disks for Container Weed Control

Transcript of 'Use of Geotextile Disks for Container Weed Control

HORTSCIENCE 25(6):666-668. 1990.

Use of Geotextile Disks for ContainerWeed ControlBonnie L. Appleton1 and Jeffrey F. Derr2

Hampton Roads Agricultural Experiment Station, Virginia PolytechniciS

,

d

ines used: 2-chloro-1- (3-ethoxy-4-nitrophen-en); N-(1-ethylpropyl)-3,4 -dimethyl-2,6-di-dichloro-5 -(1-methylethoxy)phenyl]-5-(1,1-oxadiazon); 4-(dipropylamino) -3,5 -dinitro-utyl-N-ethyl-2,6 -dinitro-4-(trifluoro-,N-dipropyl-4-(ttifluoromethyl)benzenamine

addition, Wells and Constantin (1986) re-ported extended weed control by placing” pinebark mulch sprayed with various preemerg-ence herbicides atop container media.

An additional alternative method of weedcontrol is the use of physical barriers otherthan mulch layers. Materials, such as paper,

1987 no herbicides were registered for con-tainer-grown nursery stock, Chong (1987)reported testing several “surface covers”(composition not specified) as alternatives tochemical weed control with good results.

Our preliminary studies were conducted toscreen the weed-control capability in con-tainers of certain geotextiles marketed forlandscape weed control and to compare theeffectiveness of these geotextiles with con-ventional preemergence nursery herbicides.Included in the study was a new geotextile–preemergence herbicide combination prod-uct {Biobarrier [Typar geotextile; Reemay,Old Hickory, Term., plus trifluralin (Tre-

Institute and State University, VirginAdditional index words. Pinus strobiformis, chinensis, Chinese pistache, Rhododendron inlandscape fabrics, weed barriers, oxyfluorfen

Abstract. Disks of several geotextiles, papcompared with the herbicides oxyfluorfen pplus benefin for suppression of weed growwhite pine (Pinus strobiformis Engelm.), Chand ‘Fashion’ azalea [Rhododendron indicumcontrol was obtained with a combination alin) disk, indicating a possible new methobarrier materials, including heavy wrappinpolyethylene, and one spunbonded geotextweeds growing around the disk edges or cenoted among the treatments. Chemical namoxy)-4-(trifluoromethyl) benzene (oxyfluorfnitrobenzenamine (pendimethalin); 3-[2,4-dimethylethyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-(3H)-one (benzenesulfonamide (oryzalin); N-bmethyl) benzenamine (benefin); 2,6-dinitro-N(trifluralin).

A major problem with container produc-tion of nursery stock is weed control. Weedsdetract from the appearance of the plants atsale time and reduce both crop size and qual-ity (Fretz, 1972; Walker and Williams, 1985).

Weed seed is introduced into productionvia wind, irrigation, or medium or liner con-

tamination. The major weed control mea-sures for container production are the use ofherbicides and hand weeding. While culti-vation is an additional weed control measurein field nursery production and landscapemaintenance, it is not feasible in containerproduction.Although an adequate number of effectivepreemergence herbicides exist, some grow-ers are hesitant to use herbicides due to thepotential for damage, the limited number ofspecies labeled, the timing required, or at-tempts to reduce chemical use. In addition,as more container growers recycle irrigationwater, contamination of both recycled waterand ground water is forcing growers to con-sider alternative weed control measures.

One alternative application method forcontainer production is slow-release herbi-cide tablets (Gorski et al., 1989; Smith andTreaster, 1987; Verma and Smith, 1981). In

Received for publication 27 July 1989. Use oftrade names in this publication is solely for iden-tification. No endorsement of the products namedis implied by VPI & SU. The cost of publishingthis paper was defrayed in part by the payment ofpage charges. Under postal regulations, this papertherefore must be hereby marked advertisementsolely to indicate this fact.1Dept. of Horticulture.2Dept. of Plant Pathology, Physiology, and WeedScience.

666

a Beach, VA 23455outhwestern white pine, Pistacia

dicum × ‘Fashion’, ‘Fashion’ azalea, pendimethalin, oxadiazon, oryzalin, benefin

er, fiberglass, and black polyethylene werelus pendimethalin, oxadiazon, and oryzalinth around container-grown Southwesterninese pistache (Pistacia chinensis Bunge.), (L.) Sweet × ‘Fashion’]. The greatest weedgeotextile-preemergence herbicide (triflur- of container weed control. Several of theg and compressed peatmoss papers, blackle, were inferior due to degradation or toter hole. No difference in crop growth was

polyethylene, and the new geotextiles (syn-thetic fabrics), used in landscapes and invegetable and fruit production have shownpromise for nursery weed control. Derr andAppleton (1989) reported acceptable weedcontrol when various geotextiles were usedfor landscape weed control, with control

Table 1. Growth of weeds seeded atop weed-controfor Chinese pistache.)z

Prostrate

PlantsTreatments (no./pot)

No weed check 3.8Weedy check 160Oxy + pendy 25White sbx 29Yellow sb 18Red sb 7.0Blue sb 9.0Black sb 6.8Gray sb 79Black woven 5.5White woven 12Fiberglass 8.8Paper 62Geo-herbw 0.0LSD (0.10) 30.6zMeans of four single container replications. MeayOxy + penal = oxyfluorfen plus pendimethalin (OxSb = spunbonded.wGee-herb = geotextile–preemergence herbicide com

generally better if the geotextiles were leftunmulched. Danielson (1967) reported thatan herbicide-impregnated cellulose acetatecloth was generally as effective as spray ap-plications in field trials.

Taylor (1963), using herbicide-impreg-nated burlap disks for container weed con-trol, reported “good weed control with mostherbicides, but had some test crop injury.Brown (1985) reported good weed controlwithout crop quality reduction in containerswith a felt funnel-shaped barrier and blackor white polyethylene disks. The major dis-advantage cited was the time required to wirethe polyethylene film over the container rims.Wells et al. (1987) reported satisfactory weedcontrol using black roofing felt, polyethyl-ene (no color given), and woven geotextile“liners or covers” in containers if the ma-terials remained in place. Geotextiles havethe major advantages of permitting waterpenetration and allowing fertilizer applica-tion on top of their surface, thus not requir-ing their removal. In Canada, where before

flan); Elanco Products, Indianapolis]} beingadvertised for rerouting tree roots in land-scape situations.

In addition, altering the color of the geo-textiles was investigated due to reports ofenhanced growth with certain vegetables andfruits using colored mulches. Decoteau et al.

l barriers. (Prostrate spurge for azaleas, crabgrass

spurge Largecrabgrass

Shoot fresh wt shoot fresh wt(g/pot) (g/pot)

1.82 19.930.1 179

6.20 91.110.6 82.311.3 76.56.98 67.2

12.5 69.914.3 83.124.1 75.710.8 74.113.2 73.617.9 59.926.5 126

0.00 0.0010.7 30.3

n separation in columns by LSD, P = 0.10.H2).

bination product.

HORTSCIENCE , VOL. 25(6), JUNE 1990

ir

the more aggressive large crabgrass. Large

Fig. 1. Problems with weed control barriers–a lgrowth (left top) and black plastic rolling up (ultraviolet light-inhibitors (bottom).

(1988, 1989) and Loy and Wells (1988) re-ported that colored mulches increased to-mato growth and yield. Oh et al. (1986)reported increasing the growth and produc-tion of grapes with silver polyethylene mulch.Moreshet et al. (1975) increased the growthand production of apples with laminatedplastic film vacuum-coated with aluminum.

In the first study, 2-year-old, untrans-planted Southwestern white pine (Pinusstrobiformis) seedlings were potted in 4-liter

plastic containers in a medium of 3 groundpine bark : 1 sphagnum peatmoss : 1 sand(by volume) and topdressed with a 17N-2.6P-9.9K plus micronutrient slow release fertil-izer (Sierra Controlled Release Fertilizer,Sierra Chemical, Milpitas, Calif.) at 9 g/container. The weed control treatments con-sisted of the two herbicides oxadiazon (Ron-star, Rhone-Poulenc Agricultural, ResearchTriangle Park, N. C.) and oryzalin plus ben-efin (XL, Elanco), paper disks consisting oftwo layers of heavy brown wrapping paper,6-mil (6-mm) black polyethylene disks, anddisks, cut from one of three geotextiles: agray spunbonded (Typar, Reemay), a “fuzzy”black woven (DeWitt; DeWitt, Sikeston,Me.), and a slick black woven type (Geo-scape, Innovative Geotextiles, Charlotte,N.C.). All disks were cut slightly larger thanthe container diameter to fit snuggly in place,avoiding tedious wiring.The seven treatments plus a control were

HORTSCIENCE , VOL. 25(6), JUNE 1990

ght-weight geotextile being pushed up by weedight top); decomposition of geotextiles lacking

replicated five times (single container) in acompletely randomized block design on asloped, black polyethylene-covered nurserybed with overhead irrigation. No weed seedwas introduced, so all weeds that grew re-sulted from contamination sources.

In the second study, 12-cm-tail ‘Fashion’azalea rooted liners and 15-cm-tall Chinesepistache seedlings were potted into 4-literplastic containers in the same medium asabove and topdressed with the same fertilizerat 3 g/azalea and 9 g/Chinese pistache. Weed

control treatments consisted of one herbicidecombination product; oxyfluorfen plus pen-dimethalin (OH2, O.M. Scott and Sons,Marysville, Ohio); one paper disk (Horto-paper, Actagro, Fresno, Calif.); one fiber-glass disk (Figer-Mulch, Buckley Industries,Wichita, Kan.); eight geotextile disks (a whitespunbonded) (Exxon, Landscape Supply,Roanoke, Vs.); the above-noted white spun-bonded sprayed with yellow, red, blue, andblack enamel paint; a white woven (DuPont,TEI, Baltimore); a gray spunbonded (Duon,Blunks Wholesale Supply, Bridgeview, Ill.);and a black woven type (DeWitt); and disksfrom the Biobarrier geotextile-preemergenceherbicide combination product.Pots containing the Chinese pistache wereseeded with large crabgrass [Digitaria san-guinalis (L.) Scop], and the azalea withprostrate spurge (Euphorbia supina Raf.) (ontop of the barriers), and were compared with

no weed and weedy controls. The 12 treat-ments plus two controls were replicated fourtimes (single container) in a completely ran-domized block design on a sloped, blackpolyethylene-covered nursery bed with over-head irrigation.

After 21 weeks in the first study, the treat-ments were visually evaluated on a ratingscale, where” 1 = no weeds, 2 = 1 to 2weeds, and 3 = 3 or more weeds per con-tainer. Fewer weeds were observed with ory-zalin plus benefin and the gray spunbondedand slick black woven disks (all 1.4) than inthe control (2.1). No significant differences(P = 0.10) were observed with the otherfour treatments (paper, 2.0; oxadiazon, blackpolyethylene, and fuzzy black woven disks,1.7). Weed growth had begun under the pa-per disks due to disk decomposition andaround the outside edge of the black poly-ethylene disk because the polyethylene hadbegun to roll up (Fig. 1). All geotextiles werebeginning to photodecompose due to a lackof ultraviolet light inhibitors, allowing weedgrowth (Fig. 1).

No significant growth differences werenoted with the pines, presumably becausewhat weed growth existed at the study’s ter-mination was relatively small.

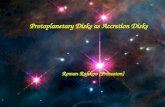

After 20 weeks in the second study, thegreatest overall control of both prostratespurge and large crabgrass was obtained withthe geotextile-preemergence herbicide disk(Table 1 and Fig. 2). Significantly moreprostrate spurge plants grew in the paper (39%of weedy check) and the gray spunbondeddisk (49%) treatments than in the combina-tion disk (0%), the no weed check (2%), theherbicide treatment (16%), and the remain-ing geotextile disks (3% to 18%) (Table 1).Prostrate spurge fresh shoot weights weresignificantly lower for the combination disk(0% of weedy check), no weed check (6%),herbicide treatment (21%), and red spun-bonded (23%) disks than for the fiberglass(59% of weedy check), gray spunbonded(80%), and paper (88%) disks (Table 1). Allother disks were intermediate.

Even greater differences developed with

crabgrass fresh shoot weights were signifi-cantly lower for the combination disk (0%of weedy check) and the no weed check (11%)than for all other treatments (34% to 71% ofweedy check) (Table 1).

Much of the failure of the geotextiles toadequately control weeds was lack of fit ofthe disks. Many weeds grew around the out-side edges and through the hole cut in thecenter to fit around the liner or seedling. Inaddition, when light was transmitted throughthe geotextile due to color (white spun-bonded) or when decomposition of the geo-textile had begun (gray spunbonded), moreweeds grew. Geotextile success as a weedbarrier depends on fabric opaqueness, de-composition resistance, and a very tight fitaround the container edge and liner.

No significant growth differences O C-curred with Chinese pistache or azaleas rel-ative to barrier type or color (data not

667

Fig. 2. Weedy check and geotextile-preemergence herbicide disk seeded with large crabgrass (top)and prostrate spurge (bottom). Small dark spots on geotextile represent herbicide attachment points.

presented). We assume that the adequatelevels of medium moisture and fertilizer thatwere maintained prevented crop growth re-duction during the study, a result that wouldbe expected to change during a typicallyl o n g e r p r o d u c t i o n c y c l e .

Nonsignificant differences in weed controlbetween the herbicide and most of the geo-textiles alone (without preemergence herbi-cides) showed that use of the geotextiles forcontainer weed control is not warranted. Thegeotextile-preemergence herbicide combi-

668

nation product provided superior weed con-trol and should be considered as a potentialmethod of container weed control.

Literature CitedBrown, W.L. 1985. Weed control in containers

with physical barriers and/or herbicide. Proc.Southern Nursery Assn. Res. Conf. 30:278-281.

Chong, C. 1987. Propagation and culture of nur-sery ornamental. Highlights of Agr. Res. inOntario 10(4):15-17.

Danielson, L.L. 1967. Evaluation of herbicide-

impregnated cloth. Weeds 15:60-62.Decoteau, D. R., M.J. Kasperbauer, D.D. Dan-

iels, and P.G. Hunt. 1988. Plastic mulch coloreffects on reflected light and tomato plant growth.Sci. Hort. 34:169-175.

Decoteau, D. R., M.J. Kasperbauer, and P.G. Hunt.1989. Mulch surface color affects yield of fresh-market tomatoes. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci.114:216-219.

Derr, J.F. and B.L. Appleton. 1989. Weed con-trol with landscape fabrics. J. Environ. Hort.7:129-133.

Fretz, T.A. 1972. Weed competition in containergrown Japanese holly. HortScience 7:485-486.

Gorski, S. F., S. Reiners, and M.A. Ruizzo. 1989.Release rate of three herbicides from controlled-release tablets. Weed Technol. 3:349–352.

Loy, J.B. and O.S. Wells. 1988. Wavelength se-lective plastic mulches for vegetables. ASHS/CSHS 1988 Annu. Mtg., East Lansing, Mich.,Prog. & Abstr. HortScience 23(3):763[107].

Moreshet, S., G. Stanhill, and M. Fuchs. 1975.Aluminum mulch increases quality and yield of‘Orleans’ apples. HortScience 10:390-391.

Oh, J. Y., J.K. Byun, S.B. Lee, and D.U. Choi.1986. The effects of cane bagging with poly-ethylene film, reflective (silver) and transparentfilm mulch on vine growth and berry ripeningof ‘Campbell Early’ (Vitus labruscana B.) grape.J. Kor. Soc. Hort. Sci. 27:127–135.

Smith, E.M. and S.A. Treaster. 1987. An eval-uation of cyanazine, terbacil and metolachlorslow-release herbicide tablets on woody land-scape crops. Ohio Agr. Res. and Dev. Ctr. Res.Circ. 289. p. 15-16.

Taylor, J.L. 1963. Herbicide treated burlap as amethod of applying preemergence herbicides tocontainer grown nursery plants. Proc. SouthernWeed Conf. 16:143-144.

Verma, B.P. and A.E. Smith. 1981. Dry-pressedslow release herbicide tablets. Trans. Amer. Sot.Agr. Eng. 24:1400-1403, 1407.

Walker, K.L. and D.J. Williams. 1985. Weed in-terference by three grass species in containergrown nursery crops. Proc. North Central WeedControl Conf. 40:96.

Wells, D.W. and R.J. Constantin. 1986. Herbi-cide-treated pine bark mulch for container-grownornamental. HortScience 21:934. (Abstr.)

Wells, D. W., R.J. Constantin, and W.L. Brown.1987. Weed control innovations for large, con-tainer-grown ornamentals. Proc. Southern WeedSci. Soc. 40:137.

HORTSCIENCE , VOL. 25(6), JUNE 1990