U.S. Policy Toward Japanese Military Normalization

-

Upload

sean-boldt -

Category

Documents

-

view

60 -

download

2

Transcript of U.S. Policy Toward Japanese Military Normalization

U.S. Policy Toward Japanese Military Normalization

Sean Boldt

Joey Cheng

Wesley Collins

Dean Ensley

Matthew Seeley

Submitted to Professor Christopher A. Kojm

The George Washington University

Elliott School of International Affairs

May 4th, 2015

Table of Contents

1. Executive Summary

2. Introduction

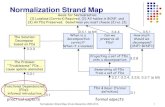

3. Policy Recommendations

a. Promote Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance Sharing

b. Support New Doctrine, Platforms, and Programs

c. Strengthen Japan-Australia-U.S. Security Partnerships

4. Metrics of viability

a. Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

i. It counters the regional threat.

ii. It provides a new, unique SDF capability.

iii. It mitigates the risks of military normalization.

b. Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

i. It contributes toward a joint posture.

ii. It increases confidence within Japan for U.S. guarantees.

iii. It reduces the burden on the U.S.

c. Can it be implemented?

i. It is domestically palatable within Japan.

ii. It is domestically palatable within the U.S.

iii. It is within the current technological and industrial capabilities of involved

parties.

5. Program Analysis

a. International Partnerships

i. Japan-Australia

b. Maritime Security

i. Amphibious Force and Capability

ii. Port Infrastructure Development

iii. Submarine Capacity Building

c. Air Security

i. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

ii. F-35 Joint Strike Fighter

iii. Airborne C4ISR

d. Ballistic Missile Defense

i. Increased Aegis capability

ii. SM-3 Block IIA

iii. Sea-Based X-Band Radar

e. Space Programs

i. Space Situational Awareness

ii. Remote Sensing and Positioning/Navigation/Timing

6. Implementation and Conclusion

7. Appendices

a. Key assumptions

i. The Japanese government will continue to move toward military

normalization

ii. The United States will continue to support the military normalization of

Japan

iii. The PRC will continue to rise and become an increasingly dominant

power in the region

iv. Territorial conflicts will continue to plague the relationship between Japan

and the PRC

b. National Police Reserve; SDF 1954-2015

c. Unresolved historical conflicts

d. Abe’s government

e. Guidelines for U.S.-Japan Defense Cooperation

f. Summary of Japanese Ministry of Defense Budgets (2011-2015)

g. Summary of Program Analysis

h. Regional Threat Assessment

i. People’s Republic of China

ii. Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

i. Current military dispositions

Executive Summary

This paper examines potential U.S. policy options in response to Japan’s recent military

normalization, covering international partnerships and the maritime, air, ballistic missile defense,

and space domains. Our purpose is to either encourage or discourage the recent efforts in these

areas initiated by Japanese officials in order to improve U.S.-Japan and regional defense

cooperation. In the future, those Japanese efforts will have a significant effect on regional

security dynamics and the Japanese-American defense relationship, while increased capabilities

will additionally affect other U.S. regional partners.

Through a literature review and approximately 25 interviews with Japanese and U.S.

defense officials, academic experts, and policymakers, we assessed specific programs within the

aforementioned domains against metrics based on regional security risks, benefits to the U.S.-

Japan alliance and other partnerships, and the feasibility of the programs.

Through this analysis, we recommend that the U.S. move in three broad areas: Promote

intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance information sharing; support new doctrine,

platforms and programs; and strengthen Japan-Australia-U.S. security partnerships. These are

thematic principles for improving the U.S.-Japan alliance in the context of Japanese military

normalization and the U.S. rebalance to the Asia-Pacific. Each principle is supported by several

specific, actionable policy recommendations. We also highlight areas in which expanded efforts

are less feasible to demonstrate inherent challenges.

Our specific recommendations for individual programs include:

Agree to 2-way information sharing for space situational awareness

Ensure GPS/QZSS interoperability

Support technology sharing and joint development of drones

Lease Aegis technology for additional upgrades to existing destroyers

Expand maritime gray zone exercises

Encourage Japanese competition in Australia’s submarine tender

Promote JSDF to full partner in Talisman Saber/Sabre exercises

Plan trilateral F-35 interoperability training

Despite potential risks involved with these recommendations, these policies will improve

U.S.-Japan defense posture, ties with other partners -- namely Australia, and overall regional

capabilities.

1

Introduction

In response to Japan’s actions in East Asia and the Pacific prior to and during the Second

World War, Japan’s 1947 Constitution renounced the sovereign right of belligerency in war and

the possession of war material.i Shortly thereafter, however, the United States policy toward

Japan shifted from that of an occupying power to that of a security patron, as it desired an

economically vibrant Japan to act as a bulwark against communist encroachment in East Asia.

Japan, benefiting from U.S. security guarantees and favorable access to domestic consumer

markets, rose within a generation from the ruins of war to possess the world’s second largest

economy. However, in keeping with the intent of Article Nine of the Japanese Constitution, and a

legally imposed limit to defense expenditure spending of one percent of gross national product

since 1976, successive Japanese administrations historically did not develop a military force

commensurate with the size of its economy.

This does not, however, suggest a lack of military investment over the years. Under

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Japan has pursued a policy of military normalization by seeking the

conventional capabilities and political relationships associated with traditional national armed

forces, in contrast to the historically limited scope of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF). On

July 1st, 2014, the Abe administration announced its intention to reinterpret Article Nine to allow

the SDF to participate in collective defense missions with other states. Due to a changing

security environment in East Asia, the Abe government correspondingly passed a record defense

budget of almost ¥5 trillion (~$43 billion) in January 2015. The budget expands the SDF’s

conventional capabilities, funds new military technologies, and facilitates changes to current

doctrine and governmental defense structure. The Abe administration has also eased restrictions

2

on arms exports, revised the U.S.-Japan Defense Cooperation Guidelines, and seeks to improve

bilateral and multilateral relationships with other Asia-Pacific nations.

The purpose of this paper is to recommend specific U.S. policy responses to either

encourage or discourage the recent efforts undertaken by Japanese officials within the context of

Japanese military normalization in order to improve U.S.-Japan defense cooperation. This is a

significant area of research for two factors. First, the policy question of Japanese military

normalization will have a significant effect on regional security dynamics and the Japanese-

American defense relationship. Enhanced Japanese military capabilities will additionally affect

other U.S. regional partners. Second, because Japan’s military normalization efforts are

accelerating, a balanced debate regarding how the U.S. should respond has yet to fully develop.

Existing work on the topic of Japanese military normalization simply does not cover the current

trend and has a tendency to examine the historical issue of the Japanese military in a what-if

fashion.

In order to appropriately pursue such an objective, a basic discussion of Japan’s stance on

the future of U.S.-Japan defense cooperation is required. The Abe administration has three

specific pillars to strengthen the U.S.-Japan security alliance: reinforcement of bilateral security

and defense cooperation, cooperation based on strategic views of the Asia-Pacific region, and

enhancement of cooperation in addressing global issues.ii In the first pillar, Japan has revised the

Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation Guidelines, improving collaboration in areas of maritime safety

and security, ballistic missile defense (BMD), cyber security, outer space, extended deterrence,

and carrying out the realignment of the U.S. Forces in Japan. In the second pillar, Japan plans to

work with the U.S. in ensuring the region is ruled by law, not by force, and promote partnerships

and encourage trilateral cooperation with the Republic of Korea (ROK), Australia, India and

3

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). This includes finalizing the Trans-Pacific

Partnership (TPP) and jointly addressing issues such as the Democratic People’s Republic of

Korea’s (DRPK) missile tests and nuclear launches or the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC)

actions around the Senkaku Islands, known in the PRC as the Diaoyu Islands. In the third pillar,

Japan plans to partner with the United States in addressing global challenges such as promoting

women’s empowerment, development, counter-terrorism, climate change, and the situations in

Ukraine, the Middle East, Africa, and elsewhere.

As Japan seeks to advance each of these three approaches to improving U.S.-Japan

defense cooperation, it is carrying out numerous changes relating to policy, doctrine, strategy,

and technology. The scope of this paper will be limited to a handful of specific aspects of the

process of Japanese military normalization, divided into the five categories of international

partnerships, maritime security, air security, ballistic missile defense, and space programs. The

United States should prioritize these categories because they provide the greatest potential for

tangible cooperation and interoperability. Each of these specific aspects will be measured against

various metrics of viability in order to establish their merit as an area the U.S. should endeavor to

support as a method to improve U.S.-Japan defense cooperation. Through such a systematic

review, clear policy recommendations for which specific aspects the U.S. should support will be

made evident.

4

Policy Recommendations

Promote Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance (ISR) Sharing

In general, the United States should support the transition of Japan from the status of

being primarily a customer of ISR data to that of being a provider. Programs and policies in the

field of ISR may move more slowly than those in other domains, requiring a longer-term

approach in many areas, but the potential results are worth this effort.

Conclude a Comprehensive Two-way Space Security Awareness (SSA) Information Sharing

Agreement with Japan

In the field of SSA, key geographical and technological advantages offered by a greater

Japanese role should be exploited to work toward building a more robust and wide-ranging

global SSA capability. The mixed civil, commercial, and military nature of these programs

renders them less vulnerable to a backlash from other regional nations or the Japanese public,

and the global nature of SSA will promote long-term integration between Japan and the United

States. In the intermediate- to long-term, Japanese efforts toward the construction of additional

space surveillance radars should be encouraged, while in the near-term the United States should

establish permanent mechanisms for two-way SSA data sharing with Japan. Such an agreement

would be low cost, and involves only existing technologies. While some hesitance to such a deep

degree of information provision by the United States will need to be overcome within the

intelligence community, strong support within NASA, the Departments of State and Defense, and

the private sector should render this proposal feasible.

Deepen Global Positioning System/Quasi-Zenith Satellite System (GPS/QZSS) Interoperability

5

In the field of Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT), inherent geographical

elements and the built-in interoperability of the QZSS system make it a prime choice for U.S.

support in the immediate-term to supplement and reduce the burden on GPS, facilitate the

interoperability of U.S. and Japanese forces in the region, and fundamentally improve the

redundancy and resiliency of critical U.S. military space systems in the face of growing PRC and

Russian anti-satellite (ASAT) capabilities. Again, the dual nature of PNT technologies and the

popularity of resulting services among the Japanese public mitigates opposition to further

development here, while some joint efforts could be conducted in a clandestine manner.

Enhanced Japanese capabilities in this area will further promote deeper U.S.-Japan integration

across multiple domains, and will serve to develop Japan’s space industry. Efforts should be

made to ensure that U.S. forces operating in the region are fully equipped and trained to fall back

on QZSS capabilities in the event of GPS degradation, while the United States should also push

to allow GPS payloads to be included in QZSS launches. Such policies can be put into place

within two years, and Japan can be incentivized to include GPS payloads with U.S. concessions

in other areas such as provision of SSA and remote sensing data.

Share Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-related Operational Knowledge and Technology

In the field of UAVs, the U.S. military should provide operational knowledge to Japan in

order to help develop its nascent UAV force. The U.S. should also encourage technology sharing

between the industries of the two countries. Currently, UAVs, despite their obvious benefits, are

not seen as a top priority by Japanese military and policy officials, leaving significant room for

growth in the future. Japan’s expertise in robotics, combined with U.S. operational experience,

could significantly yield benefits for each country in terms of both long-term strategic

development and near-term Japanese UAV operations for C4ISR. Strengthening cooperation here

6

could also link the well-established UAV industry in the U.S. to advanced technology created in

Japan.

Resist Expanding the Sea-Based X-Band Radar Program

Regarding the SBX-1, The Missile Defense Agency (MDA) should explicitly deny any

possibility of additional production or permanent forward basing in Japan. Simply put, while the

SBX-1 is a uniquely capable and useful platform, there is neither interest in the Department of

Defense (DoD) nor operational necessity for further production. Additionally, its maritime

mobility and radar functions are somewhat duplicated in other platforms, so its most significant

contribution to the alliance is ‘showing the flag’ through temporary deployments in response to

crises. The MDA, and by extension the DoD, should reassert the SBX’s role as a form of the

U.S. guarantee for Japanese security, but resist any discussion of expanded operational uses, such

as different mission priorities or deployments to the East or South China Seas.

Support New Doctrine, Platforms, and Programs

Lease the Aegis Weapon System to Upgrade Japanese Destroyers

The U.S. DoD should continue to lease the Aegis Weapon System to Japan in order to

upgrade the BMD capability of additional destroyers, as has been done with the Atago-class.

Potential platforms include the Hatsuyuki, Asagiri, Abukuma, and Hatakaze classes, all of which

are funded for life extension measures in recent Japanese Ministry of Defense (MoD) budgets. In

contrast to constructing new Aegis-equipped destroyers, upgrading existing platforms will

counter the regional threat while not portraying an aggressive or expansive maritime posture.

Moreover, using destroyers to provide a BMD function is more desirable than Aegis Ashore,

which would force U.S. to reconsider Aegis Ashore’s current intended role as a European

platform and be built in the vicinity of the Japanese public. If done on a ship-by-ship basis,

7

continuing the current leasing design for Japanese platforms is advantageous for the U.S.

because it will relieves American burdens to provide BMD and enables U.S. assets to be

reallocated within the rebalance to the Asia-Pacific policy.

Conduct More Bilateral Amphibious Exercises

In order to facilitate the creation of the Dynamic Defense Force (DDF) in the SDF, the

U.S. should advocate for an increasing number of amphibious military exercises in the Asia-

Pacific region. The U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) should take the lead to provide guidance to the

DDF and other participating amphibious forces from the region. The implementation of

additional amphibious exercises can combat potential gray zone scenarios and quell Japanese

fears of U.S. disinterest in these smaller ticket items. Additionally, these amphibious exercises

can promote seamless defense cooperation between the Ground Self-Defense Forces (GSDF) and

the Maritime Self-Defense Forces (MSDF), plus the militaries of the U.S. and Japan as a whole.

Minimize Port Infrastructure Development in the Southwest Island Chain

The port infrastructure development process is beneficial to the U.S.-Japan alliance, but

incurs too great a risk when expanded to contentious areas of the southwest island chain. The

first obstacle to the implementation of this strategy is domestic opposition in Okinawa. A second

obstacle to implementation is the potential irritation of neighboring countries. For example, the

PRC will view port infrastructure development deep into the southwest island chain as

antagonistic. This process would exacerbate an already contentious relationship with the PRC

over maritime territory. Furthermore, additional neighbors in the area of the South China Sea

may disapprove of Japan extending its reach further into the southwest region, especially if

military basing opportunities are incorporated.

8

Strengthen Japan-Australia-U.S. Security Partnerships

Expand Competition to Replace Australia’s Collins-class Submarine

The U.S. and Japanese governments should encourage Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and

the Kawasaki Shipbuilding Corporation to join Australia’s open tender and compete to design the

Collins-class replacement submarine. Assuming either or both firms would design and build a

modified Soryu-class or entirely new submarine to meet Australia’s strategic requirements,

Japan’s domestic defense sector would receive an immediate stimulus as the purchase would

roughly double the current demand in Japan. The Japan-Australia relationship would also receive

long-term benefits as those two countries’ defense sectors and maritime forces would enjoy a

positive relationship over the lifetime of the replacement submarines.

Expand Japan’s Role in the Talisman Saber/Sabre Exercises

The U.S. government also should evaluate the possibility of bringing the Japanese SDF

on as a full partner in the Talisman Saber/Sabre biennial exercises. This would entail not only

expanding the size and scope of training but, more importantly, putting the SDF into the

exercise’s leadership rotation, thereby giving Japan real operational experience for Japan-

Australia contingencies. Additionally, the U.S. should invite the Australian Defense Forces

(ADF) to participate in greater numbers in already existing joint U.S.-Japan training maneuvers,

and continue exercises such as Southern Jackaroo.

It is highly probable the joint Japan-Australia submarine ventures, or increased training

exercises, will not be well received by the PRC government or body-politic as both initiatives

focus on the kinetic spectrum of military operations. However, given Australia’s submarine

requirement and the scarcity of potential suppliers, it is unlikely the government would reject a

9

Japanese bid. Likewise, the ADF has few peers in the region and the benefits of developing a

true interoperability between its longtime ally, the U.S., Japan and itself would likely outweigh a

PRC demarche. Finally, if the U.S has an interest in strengthening Japan’s security through

expanded partnerships as well as its own position as first ally among equals, then Japanese

participation in both the Collins-class replacement project and regional training exercises is a

necessary requirement.

Link Japanese and Australian Contributions to the F-35 Program

The U.S. government should leverage the F-35 platform to link partners in the Asia-

Pacific region, in particular Australia and Japan. Once the F-35 reaches initial operational

capability, the U.S. should encourage the inclusion of F-35 interoperability missions into both

Japanese bilateral and multilateral exercises such as Exercise Cope North and the

aforementioned Talisman Saber/Sabre. The U.S. should encourage Australia to allow the use of

the Woomera Test range by Japanese F-35s for long range weapons and operational testing, as

Japan lacks large overland test and training areas, especially for electronic warfare tests.iii While

the focus should be on increasing ties with Australia in the short-term, the F-35 could, in the

future, be leveraged in the same way to improve interoperability with other F-35 users, namely

the ROK.

10

Metrics of Viability

1. Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. It counters the regional threat.

This aspect will evaluate new political and strategic initiatives as well as specific intelligence

and weapons platforms and programs in order to determine whether or not they promote a power

balance that is in favor of the alliance, vis-à-vis the PRC and DPRK. By maintaining a favorable

power balance, Japan will be able to maintain its territorial sovereignty and freedom of maneuver

in East Asia region and strengthen the U.S. regional position.

b. It provides a new, unique SDF capability.

This aspect should provide a military capability that the SDF did not previously possess. This

could be a niche capability that the U.S. cannot provide or leverage a Japanese comparative

advantage it possesses over its alliance partner due to its geographic proximity, economic

integration, or cultural alignment in the region. This aspect will therefore have an outsized

impact on the partnership’s defense capabilities.

c. It limits the regional security risks of military normalization.

This aspect will see programs and policies evaluated against their risk of provoking a more

aggressive attitude or response from Japan’s regional adversaries in the PRC and DPRK, causing

a deterioration in ties between Japan and partner nations, such as the ROK or the countries of

ASEAN, or worsening the East Asian regional security environment in general. Promoting East

Asian stability is a major goal of U.S. policy, and unresolved historical issues and territorial

11

conflicts between Japan and several of its neighboring states create vulnerabilities and

sensitivities that must be carefully navigated in Japan’s process of military normalization.

2. Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. It contributes toward a joint posture.

This aspect should provide room for growth of joint collaboration between various sectors

within each nation. Such a posture can be described as military-military, political-political, or

otherwise. Opportunities include humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR), ISR

sharing, maritime security, undersea warfare, and BMD. Increasing joint posture implies

increasing awareness of interconnectedness, demonstrating collaboration to domestic audiences,

and announcing collective efforts to the international community.

b. It increases confidence within Japan for U.S. guarantees.

This aspect should provide clarity for domestic audiences within Japan regarding the U.S.

commitment to the Asia-Pacific. As the U.S. is constantly involved in operations around the

globe, the Japanese public is becoming increasingly skeptical of U.S. commitment to the region

and needs reassurances. Moreover, there is worry over increasing U.S. public attention and

realignment toward the PRC and away from Japan.

c. It reduces the burden on the U.S.

This aspect should promote parity in security or political encumbrances carried by each

nation. While each nation faces fiscal and domestic partisanship difficulties, the U.S. has

numerous global responsibilities that correspondingly limit its ability to wholly dedicate its

12

resources to Japanese security. Burden reduction can come in the form of increasing Japanese

military spending, political presence, domestic willingness and support, or otherwise.

3. Can it be implemented?

a. It is domestically palatable within Japan.

This aspect should be acceptable to domestic audiences within Japan. While the Abe

administration has been a major force behind military normalization, significant opposition still

exists in the form of left-wing opposition parties, Abe’s Komeito coalition partner, and a

Japanese public that remains uneasy regarding military expansion. Japan’s ability to financially

sustain elements of a more robust defense posture is an additional consideration of this aspect.

b. It is domestically palatable within the United States.

This aspect should be acceptable to domestic audiences within the United States. While the

Obama administration is implementing the rebalance to the Asia-Pacific, the process of Japanese

military normalization may or may not align with U.S. interests. There is at least broad support

for this trend, but opposition could arise against dramatic Japanese policy changes or operational

postures. Of critical importance, any increased American role must fit within the confines of the

current fiscal climate.

c. It is within the current technological and industrial capabilities of involved parties.

This aspect must be feasible in terms of the technology and industry requirements necessary

for implementation. All involved parties must have the wherewithal and understanding in order

to develop and produce new platforms, carry out new operations, and apply new policies. There

must also be sufficient resources in order to accomplish the desired aspect.

13

International Partnerships

Recognizing the importance of Japan to its own strategic position in the Asia-Pacific, the

U.S. seeks to bolster Japan’s security through the expansion of regional partnerships. iv Japan and

Australia, two separate but longtime U.S. allies, could develop a security partnership with one

another. This would benefit Japan and Australia as well as the U.S. because all parties share

commitments to democratic governance, rule of law, and open trade. Currently the heads of both

the Japanese and Australian governments enjoy a positive relationship and Japan’s move to relax

its longstanding prohibition on arms exports offers an avenue to partnership.

This section will examine the sale of Japanese submarines to Australia and joint exercises

between the two nations.

Submarine Deal

In 2007, the Australian government identified the requirement to replace its aging

Collins-class diesel-electric submarines with a new class or evolved design. In 2014, a deal for

Australia to outright purchase the Japanese Soryu-class submarine fell through. In 2015, the

Abbot Administration announced an open tender for the design, building and maintenance of the

Collins-class replacement. French and German submarine manufacturers are officially exploring

build options with the Australian government, and elements within the Japanese defense sector

have speculated that Japanese manufacturers might join the tender.v

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. The sale of Japanese submarines to Australia would help counter the regional threat by

providing the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) with increased defense capability as well as

helping to build a Japan-Australia security partnership.

b. Submarine sales would not provide the SDF with a new or unique capability, though it would

boost Japan’s defense sector.

14

c. Submarine sales do not mitigate the risk of military modernization. It is possible that the PRC

government will view Japanese arms exports and MSDF-RAN interoperability in a negative

light.

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. Submarine sales contribute to a joint posture between Japan and Australia, two U.S. allies,

but not with the U.S. itself. The deal would help create MSDF-RAN interoperability and link

Japanese and Australian defense industries.

b. Submarine sales will have little to no direct impact on Japanese confidence on the U.S.-Japan

security alliance.

c. Submarine sales would strengthen the RAN and MSDF-RAN interoperability, which lessens

the U.S. defense burden.vi

Can it be implemented?

a. Submarine sales are domestically palatable inside Japan as revisions to arms export controls

have generated only limited opposition.

b. The U.S. has no reason to object to Japanese submarine sales to Australia.

c. Submarine sales are implementable assuming Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Kawasaki

Shipbuilding Corporation can build a conventionally powered submarine with a range of

9,000 nm. It will also require that the submarines are partly or wholly built inside Australia.vii

Based on this analysis, Japanese submarine sales to Australia would help counter the regional

threat by providing a potential security partner with increased maritime defense capability. It

would not however, give Japan an inherently new or unique capability; and it does not mitigate

against regional security dilemmas. The deal could deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration as it

would tie two American allies into a security partnership of their own. Finally, a deal could be

struck assuming Japan’s defense industry can build submarines to RAN specifications and satisfy

Australian political pressure related to its domestic building industry.

SDF-ADF Joint Exercises

The Abe administration desires to expand the SDF cooperative security mandate to

include aiding ADF should they come under fire while conducting training or surveillance

maneuvers.viii This would tie the armed forces of both countries together as well as combine the

spokes in the U.S.-led hub and spoke system. The SDF and ADF have recently begun joint

15

exercises in order to develop interoperability between the forces. In 2013, the U.S. and

Australian Armies and the GSDF conducted the first ground based training exercise in

Australia.ix In late 2014, the SDF was given an invitation to participate in the biennial U.S.-

Australia Talisman Saber/Sabre exercise.x

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. Joint exercises would help to counter the regional threat because it will increase U.S., Japan,

and Australian interoperability.

b. SDF-ADF interoperability brings a new, but not unique capability to Japan.

c. Japan-Australia joint exercises do not necessarily mitigate regional responses to military

modernization. It is likely that the PRC government will disapprove.

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. Joint exercises increase joint posture by building interoperability between U.S., Japanese and

Australian forces.

b. Joint exercises increase Japanese confidence toward the U.S.-Japan alliance because it brings

Japan into a larger alliance structure.

c. Joint exercises reduce security burdens on the U.S. because they increase the capacities of

Japan and Australia to work together in the region.

Can it be implemented?

a. Joint exercises are domestically palatable inside Japan as long as they do not take place in

heavily populated areas.

b. Joint exercises are domestically palatable in the U.S. due to the general political support for

greater integration among its allies.

c. Joint exercises are technologically feasible as each partner country possesses the requisite

capabilities to contribute.

Based on this analysis, bringing the SDF into more joint exercises involving the U.S. and

Australia would help counter the regional security threat by developing real interoperability

between all three national forces. It would not impart a new or unique capability to the SDF other

than increased ability to lead joint operations, but it could upset other regional actors. Joint

exercises will increase U.S.-Japan defense integration and is implementable.

16

Maritime Security

The defense of Japanese islands, including the Ryukyu Islands and contentious Senkaku

Islands in the Southwest Region, has headlined maritime security issues in recent years. As a

result of constant PRC provocations in the area surrounding these islands, a ‘gray zone’ scenario

is considered to be one of the most immediate threats to Japanese security. Gray zone scenarios

are defined as “violations of Japanese sovereignty that are not clear military invasions requiring

the issuance of a defense mobilization order but are beyond the policing capacity of the Japan

Coast Guard.”xi The fact that Japan does not have a legal mechanism or contingency plan in

place to address these scenarios further adds to the complexity of the situation. Another issue

related to the gray zone threat is the PRC establishment of an Air Defense Identification Zone

(ADIZ) in the East China Sea in 2013. Ongoing land reclamation and facility construction efforts

in the South China Sea suggest that the PRC may be gearing up to announce a new ADIZ to

cover this area.xii

Amphibious Force and Capability

A potential countermeasure to the gray zone threat has been the proposal for a new

amphibious branch of the SDF, referred to as the DDF in the National Defense Program

Guidelines in 2010. The appeal of such a force is reflected in the potential of an amphibious

force that can defend and retake island territories and perform HADR operations. However, some

have emphasized that an amphibious capability should remain in the GSDF, and that the several

thousand GSDF Special Forces that are stationed throughout the island chain already perform

these functions adequately.

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

17

a. An amphibious force counters the regional threat by adding a new DDF that can effectively

defend and retake island territories.

b. This force provides a new niche SDF capability – an amphibious force that can provide a

similar role to that of the USMC.

c. It will aggravate regional security risks in the region, especially in regards to the PRC,

because of the utility of this force for the ongoing island territory disputes.

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. A new amphibious force contributes to a joint posture within the U.S.-Japan alliance in the

region by increasing the ability of Japan to participate in critical military-military exercises

and HADR operations.

b. This force will not increase confidence within Japan for U.S. guarantees because the SDF

will be filling a gap in their own military structure that the USMC previously covered.

c. The new amphibious force will reduce the burden on the U.S. by lessening the burden on the

USMC forces in the area.

Can it be implemented?

a. It is domestically palatable in Japan because it would serve an important role in HADR

operations and counter the gray zone threat.

b. It is domestically palatable within the U.S. because it would reduce the burden on the USMC

and allow for a joint response to gray zone threats.

c. It is within current technological and industrial capabilities because the DDF will employ

pre-existing technologies such as the Amphibious Assault Vehicle.

Based this analysis, the U.S. should encourage the implementation of the DDF. This

would allow for burden sharing opportunities between the U.S. and Japan, and ultimately

increase Japan’s ability to counter gray zone incidents. The force, in terms of its HADR aspect,

will be palatable to Japan’s domestic audience.

Port Infrastructure Development:

Japan is seeking to increase their port development efforts throughout the southwest

island chain, which currently lacks large port infrastructure. These port development efforts can

provide significant benefits to the U.S.-Japan alliance, including greater operational flexibility

and the potential for new U.S. bases in the region. However, these developments would likely

face opposition from both domestic and foreign factions.

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

18

a. It counters the regional threat by providing increased infrastructure and basing opportunities

to deter enemies and enable a quick response.

b. The port development provides a niche capability to ensure increased reach for the SDF

around the maritime nation.

c. It aggravates the regional security risks by establishing additional Japanese ports closer to

neighbors in the South China Sea and the PRC.

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. It contributes to a joint posture by potentially allowing for increased U.S. forward

deployment points in and around Japan.

b. The port developments could increase confidence within Japan for U.S. guarantees if the

U.S. were to establish new forward deployment points as a result.

c. The development of new ports in the region may reduce the burden on the U.S., depending

on if they provide additional basing opportunities for the U.S. military.

Can it be implemented?

a. The project may face domestic opposition from citizens closest to the new ports. Depending

on the exact location of the new ports that are developed, it may also anger the people of

Okinawa.

b. It is domestically palatable within the U.S. because it extends the reach of the SDF and

potentially provides additional basing opportunities for the U.S. military.

c. It is within current technological and industrial capabilities for the SDF to build additional

port infrastructure in the region.

Based on this analysis, port infrastructure development in the southwest island chain is a

risky venture. While it allows for increased power projection of the U.S.-Japan alliance in the

region, there is the potential for opposition from domestic constituencies as well as foreign

neighbors that feel threatened by Japan extending its reach further into this area.

Submarine Capacity Building:

The MSDF already boasts some of the most advanced technology when it comes to

submarines, including the stealthy Hakuryu, known as the “ninja of the seas.”xiii Over the next

ten years, the MSDF plans to increase their Soryu-class submarine fleet from 16 to 22 vessels.xiv

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. It counters the regional threat posed by the advanced submarine fleets of the PRC and DPRK.

b. It does not provide a new capability, even though it builds upon the pre-established

comparative advantage of the Soryu-class submarines.

c. It will antagonize regional adversaries that already view the Japanese submarine fleet as a

threat.

19

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. It will not contribute to a joint posture because it is a Japanese endeavor with Japanese

funding.

b. It will not increase confidence within Japan for U.S. guarantees because this is a wholly

MSDF process using Japanese money and effort.

c. It will reduce the burden on the United States Navy in the region by bolstering the capability

of the MSDF.

Can it be implemented?

a. It is domestically palatable as it counters the strengths of adversaries in the region, namely

the PRC and DPRK.

b. It is domestically palatable within the U.S. because it strengthens the overall naval power

projection of the MSDF.

c. It is within current industrial capabilities because the MSDF already employs this

technology; they are just looking to expand their fleet.

Based on this analysis, Japan should continue to build up their Soryu submarine fleet. These

submarines give the MSDF a competitive advantage in the field and counter the strong

submarine forces of rivals such the PRC and DPRK.

20

Air Security

The Air Self-Defense Forces (ASDF), which fields a variety of U.S. and indigenously

designed aircraft, is responsible for the protection of Japanese territory from air incursion. As of

late, there have been a record-breaking number of scrambles made by Japanese fighter planes to

intercept Russian and PRC planes. The dispute between the PRC and Japan in the Senkaku

Islands is believed to be largely behind the increased activity, though some scrambles are in

response to Russian activity near the disputed Kuril Islands.xv

This section assesses programs for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), the F-35 Joint

Strike Fighter, and airborne Command, Control, Communication, Computers, Intelligence,

Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR).

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

UAVs represent systems with significant potential to provide a niche capability for Japan,

with some types more viable than others. Unmanned aircraft, such as the Global Hawk, could be

used to operate in the East China Sea without exposing crews to contested and denied areas.xvi

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. They counter the regional threat by improving the SDF’s ISR capabilities in the face of

aggressive actions by the PRC and the DPRK, supporting sea-based ISR and signals

intelligence missions.

b. They provide a new capability by supporting air-to-air refueling and cargo missions by

limiting human risk.xvii Large-scale use of UAVs in the future could allow Japan to make up

for inferior numbers, maintaining peak efficiency without risking human lives.xviii

c. They may antagonize regional neighbors because increased drone usage could spark UAV-

vs.-UAV battles over disputed areas.xix

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. UAV development contributes to a joint posture because the United States can provide

operational know-how while Japan can contribute technological expertise in robotics in joint

development projects.

b. Joint development of UAV capabilities does not increase confidence for U.S. guarantees.

c. Improving UAV capabilities will allow Japan to use UAVs separately from the U.S. This

means the U.S. does not have to provide drone capabilities, reducing the overall burden.

21

Can it be implemented?

a. Japanese funding for UAVs is expected to increase to ¥37.2 billion ($372 million) in the next

decade, a more than 300 percent increase. Japan has also lifted its arms exports ban, reducing

barriers to increased cooperation. Unarmed UAVs do not have offensive capabilities, and are

therefore domestically palatable.

b. The U.S. Department of State (DoS) has loosened export restrictions for UAVs, opening up

the potential sale of armed drones. Japan would likely be able to agree to conditions set by

DoS, such as cracking down on domestic populations. Domestic arms manufacturers will

have to be given incentives due to increased cooperation with Japanese defense firms.

c. They are within current industrial capabilities. The U.S. is the world leader in UAV

knowledge, while Japan has significant expertise in robotics.

Based on this analysis, the U.S. should pursue technology sharing and joint development of

UAVs. These actions would increase joint posture and reduce U.S. defense burden, while being

largely implementable. The risk of potential domestic backlash is low and the risk to regional

stability is worth the increased Japanese capability and the technological gain for the U.S.

F-35 Joint Strike Fighter

One of the most visible demonstrations of U.S.-Japan defense cooperation is the F-35

Joint Strike Fighter. Despite initial demands for just licensing rights, Japan decided to participate

in the program and is in the process of creating assembly plants and maintenance facilities for

regional users. The first international partner on the project, Tokyo has plans for 42 F-35s by

2021 with 25 planned over the next five years.xx The justification for the program comes largely

from Japan’s need to modernize its air force, particularly its aging F-4 Kai fighters.

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. The F-35 will counter the regional threat by improving Japan’s capability to gain and

maintain air superiority, to enhance deterrence in contested areas, and the defense of the first

island chain.

b. The F-35 fighter offers a new capability because it is designed to operate as a fleet, rather

than an individual aircraft, enabling improved situational decision-making and awareness as

compared to other platforms. Individual planes from different nations could potentially be

interconnected in operations.xxi

c. It will antagonize regional adversaries because the new capability will be interpreted as a

threat to their own air superiority.

22

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. The F-35 contributes to joint posture because of increased industrial cooperation and

technology sharing with the U.S. to build the aircraft. The F-35 contributes to distributed

defense by linking allies with a common platform, shared maintenance facilities, and system

interoperability.

b. The program increases confidence in U.S security guarantees because it increases reliance of

U.S fighters deployed in the region on Japanese maintenance facilities.

c. The maintenance facilities and improved Japanese fighter capabilities also reduce the burden

on the U.S. by increasing Japanese contributions to its own security.

Can it be implemented?

a. Most of the legal and financial barriers to the fighter have been resolved, though future

budget cuts may adversely impact the program -- especially if subsidies are required. Japan

may have to increase ties with the ROK in order to see increased cooperation.

b. Despite increasing costs for the F-35 program, the projected procurement cost of late has

gone down by almost two percent due to lower labor costs, lower estimated inflation rates,

and a cut in the required number of spares.xxii Efforts have been made to cut costs, improve

oversight, and keep the program on schedule.

c. The aircraft are within current industrial and technical capabilities. The first initial operating

capability for the F-35B is expected in July 2015.

Based on this analysis, the U.S. should leverage the F-35 to increase promote multilateral

defense ties. The program is already being implemented and is a potential tool for increasing

defense ties operationally and industrially due to its unique information sharing capabilities.

Airborne C4ISR

Alongside unmanned aircraft, Japan has chosen to upgrade its airborne C4ISR

capabilities. For instance, it has chosen the E-2D Advanced Hawkeye airborne early warning and

control system (AEW&C) to replace its older E-2C models, as well as upgrade its E-767 airborne

warning and control system (AWACS).xxiii

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. These assets counter the regional threat by allowing Japan to maintain maritime surveillance

of contested areas such as the Senkaku Islands and conduct more effective command and

control, increasing its deterrence capabilities.

b. Airborne C4ISR does not give Japan a niche capability because the U.S. is likely to have the

same, if not more effective, platforms.

c. These systems are unlikely to aggravate regional security risks because they are unarmed and

are less likely to be interpreted as offensive weapons.

23

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. Due to using the same systems as the U.S., these capabilities increase interoperability and

joint posture with the U.S. military. The E-2D and E-767 do not promote distributed defense

because regional allies such as Australia and the ROK use different platforms.

b. These aircraft do not increase confidence in U.S. security guarantees because they will

largely only improve Japanese capabilities -- though interoperability could increase the U.S.

capability to come to Japan’s aid.

c. Increasing Japanese airborne C4ISR capabilities reduce the need for U.S aircraft to conduct

the same patrols, spreading the burden of maritime ISR missions.

Can it be implemented?

a. The programs are domestically palatable in Japan because they are unarmed and can be

interpreted as defensive weapons.

b. The programs are domestically palatable in the U.S. because they increase interoperability

and informations sharing.

c. Using existing components, they are both within industry and technology capabilities.

Based on this analysis, airborne C4ISR is an important defensive asset for the Japanese

military. However, the F-35 and UAV recommendations are more effective in promoting a joint

defense posture and increasing defense ties among partners.

24

Ballistic Missile Defense

The government of Japan first began preliminary consultations on BMD with the U.S.

after the first Nodong flight test in 1993, leading to a U.S.-Japan joint study in 1995, and

ultimately the decision in 2003 to acquire BMD systems. Deployment of BMD units in the SDF

finally began in 2007.xxiv

This section will examine Japan’s increasing Aegis capability, the developmental SM-3

Block IIA missile, and additional Sea-Based X-Band Radar systems.

Increased Aegis Capability

The Aegis Weapon System (AWS), a U.S. technology, is currently leased to Japan in the

form of Aegis-equipped Kongo-class destroyers. Japan is in the process of upgrading two Atago-

class destroyers with Aegis technology, constructing new Aegis-equipped destroyers, and

considering purchasing the land-based variant of the AWS, Aegis Ashore.

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. Destroyer-based Aegis and Aegis Ashore both counter the regional threat by providing

additional tracking and interception capabilities.

b. Though neither provides a new capability, destroyer-based Aegis provides a niche SDF

projected mobile, BMD capability. Both systems, however, rely on the AN/SPY-1 radar and

the SM-3 missile so there is no tactical comparative advantage.xxv

c. Neither fixed Aegis Ashore positions nor upgrading additional destroyers with Aegis

technology will antagonize regional adversaries. Conversely, constructing new Aegis

destroyers suggests a more aggressive maritime potential and will threaten the PRC’s

dominance of their coastal areas.xxvi

Does it deepen U.S. Japan defense integration?

a. All of these options involve a U.S. technology, even if funded and operated by purely

Japanese forces, and therefore contribute to a joint posture.

b. As Aegis is an American technology, greater usage will promote positive views of the U.S.

and therefore strengthens Japanese confidence in U.S. guarantees.

c. None of these will reduce U.S. financial burdens, but they will allow the U.S. to realign

BMD assets in the Asia-Pacific to support other strategic partners.

25

Can it be implemented?

a. Aegis Ashore is not domestically palatable in Japan because people fear living in the vicinity

of wartime targets and because it can be perceived as anchoring Japan to the defense of the

U.S., whereas destroyers are hailed as a purely Japanese defensive mechanism.

b. Leasing Aegis Ashore to Japan is domestically palatable for the U.S. as it is already being

developed for allies, currently through the existing European Phased Adaptive Approach.xxvii

c. Additional Aegis destroyers are feasible because the U.S. will likely continue leasing the

technology to Japan as a major regional ally. However, the 2015 MoD budget’s BMD

allocation of ¥244.9 billion (~$2.4 billion) BMD for both cannot be sustained. xxviii

Based on this analysis, Aegis destroyers are a more viable opportunity for increased

cooperation than Aegis Ashore. Destroyers provide the same BMD capabilities on a more

flexible platform and are a prime example of the U.S. commitment to Japan.

SM-3 Block IIA

The SM-3 Cooperative Development Program is the joint U.S.-Japan development of the

SM-3 Block IIA. Since 2012, Japan alone has spent ¥16.4 billion (~$164 million) on the

Raytheon-Mitsubishi program, which is on track to begin flight testing in 2015.xxix

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. The SM-3 Block IIA meets the regional threat because its 21-inch diameter motor and kinetic

warheads are specifically designed to provide improved velocity and range against short-,

medium-, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles.

b. It provides a new SDF capability of improved, sea-based interceptors.

c. It is simply an improvement upon an existing platform and therefore has not, and will not,

significantly antagonize regional rivals.

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. As a U.S.-Japan development, it symbolizes joint business and military partnerships.

b. It represents the U.S. role in Japanese BMD and therefore increases confidence in Japan for

U.S. guarantees.

c. It reduces the financial burden on the U.S. by outsourcing some design, production, and

testing, as demonstrated by Japan’s annual contribution of about ¥9 billion (~$90 million).

Can it be implemented?

a. It is mostly palatable in Japan, but some experts believe the Japanese role in producing a

platform largely designed for European missile defenses signifies interconnectedness with

European defenses, contrasting traditional Japanese security concerns being entrenched in the

areas surrounding Japan (shuhen).xxx

26

b. It is palatable in the U.S. because it promotes the concept of distributed defense with Japan,

as Raytheon is manufacturing the kill vehicle, Aerojet is building the first-stage motor, and

Mitsubishi is building the nose cone, second-stage and third-stage motors, staging assembly,

and steering control for the interceptor.xxxi

c. It is feasible because there is significant interest in both Japan and the U.S. defense and

political communities for modernized interceptors, as well as sufficient funding and

technological capability.

Based on this analysis, the SM-3 Block IIA represents an area ripe for cooperation. It

provides a unique avenue for distributed defense, alleviates budgetary concerns for both nations,

and improves the interceptor aspect of BMD. Despite being a potentially dual-use technology,

the SM-3 platform is regarded as purely defensive and is not perceived as aggressive.

Sea-Based X-Band Radar

The SBX-1, based in Adak Island, Alaska, is a unique, self-propelled vessel and radar

system without a concomitant interceptor. Japanese officials have expressed interest in a

permanent forward basing plan or the construction of additional SBX platforms.

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. The SBX-1 counters the regional threat by using 45,000 transmitter/receiver modules in an

electronically scanned array to track baseball-sized objects at a distance of 2,500 miles in a

full 360-degree azimuth and 90-degree elevation to provide mobile precision tracking, object

discrimination, and missile kill assessment functions. xxxii

b. It provides a new, niche combination of features, but destroyers match its maritime mobility

with even greater speed and Terminal High Altitude Air Defense also uses X-band radar.

c. It projects a purely defensive posture with increased sensory acuity and therefore does not

currently aggravate regional nations. Additional or permanent forward deployments,

however, could.

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. It shares tracking data with Japanese forces and officials, and therefore contributes toward a

joint posture.

b. It increases confidence in Japan for U.S. guarantees because it was specifically deployed in

response to the April 2012 Unha-3 launch and redeployed after their similar December 2012

launch, exemplifying U.S. dedication to Japanese security.

c. It does not reduce the burden on the U.S. because it is an entirely American endeavor, with

American funding and implementation.

Can it be implemented?

27

a. It is domestically palatable in Japan, even though tts official mission prioritizes BMD

protection for the “U.S. [and] its deployed forces”, and it reinforces the idea that Japan is

being anchored to the defense of U.S. assets. xxxiii

b. Neither permanent forward basing plans nor the construction of additional SBX platforms are

domestically palatable in the U.S. because it was a one-time project. U.S. Army Col. Mike

Arn, SBX project manager for the MDA, notes that it is “the only one of its kind” and “there

are no current plans for another one.”xxxiv

c. It is technologically and industrially within the scope of U.S. production capability.

Based on this analysis, the SBX platform fails to necessitate greater investment. Even though

it allows the U.S. to demonstrate commitment in times of crisis, its redundant capabilities and

unique nature disallow production economies of scale.

28

Space Programs

While the United States and Japan have a long history of cooperation in the realm of civil

and commercial space activities dating back to 1969, a legal framework that required all

Japanese space activities take place for strictly peaceful purposes prevented the development of

significant U.S.-Japan security cooperation in this domain.xxxvWith the creation of Japan’s Basic

Space Law in 2008 and corresponding revisions to the governance of space policy in 2012 and

2013, however, new opportunities for defense cooperation between Japan and the United States

have opened up.xxxvi The Abe cabinet’s early 2015 announcement of its 10-Year Basic Plan on

Space Policy has generated a substantial dialogue and led to the classification of space as a major

pillar of the U.S.-Japan security relationship for the first time.xxxvii

This section examines Japanese efforts to develop greater capabilities in SSA and PNT.

Space Situational Awareness

SSA refers to the field of tracking both man-made and natural objects in space, including

artificial satellites, solar winds, and space debris. While Japan currently operates four FPS/5

Early Warning Radar sites that, despite their primary orientation as part of Japan’s Ballistic

Missile Defense System, provide some limited degree of SSA, efforts are underway to develop

and deploy a “Space Surveillance Radar”, similar in function to the AN/FPS 133 “Space fence”

system previously employed by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, within Japan.xxxviii

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. In the current atmosphere of increasing PRC and Russian ASAT capabilities and the growing

threat of uncontrolled space debris after events such as the PRC’s kinetic ASAT test in

January 2007, improved SSA will allow Japan to monitor threats to its space assets as well as

the American assets that allow U.S. forces to operate smoothly in the region. xxxix

b. Japan’s geographical location at the heart of perhaps the most important region for SSA today

would allow SSA ground stations to provide a significant comparative advantage in

procuring and providing data on threats to alliance assets.

29

c. SSA capabilities are difficult to criticize as they are a dual-use technology with substantial

applications in civil and commercial space for debris tracking and collision avoidance, as

well as security functions in tracking potentially hostile satellites. Better SSA can also play a

role in the promotion of Transparency and Confidence Building Measures (TCBMs)

surrounding space assets that could contribute in a positive way to overall regional security

by deterring ASAT tests.

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. Current arrangements on the sharing of SSA data are governed by the limited 2013

Agreement on Space Situational Awareness Services and Informationxl, but greater Japanese

capabilities could pave the way for meaningful two-way sharing in the near future.xli

b. Greater American reliance on SSA data collected from facilities in Japan would create a

greater stake for the U.S. in Japan’s security and defense, increasing Japanese confidence.

c. A greater indigenous SSA capability within Japan could serve to free up American resources

dedicated to SSA in the region for possible relocation to other partner states such as Australia

or India, areas in which the United States suffers major gaps in SSA coverage. xlii

Can it be implemented?

a. A poll of public comments on the 2015 Basic Plan on Space Policy showed that less than 15

percent indicated Japan should restrict its use of space to non-military activities. xliii Within

the Japanese public, space security occupies a small portion of the major public debate

regarding the overall direction of Japan’s defense policy, increasing the likelihood that

programs in this area can be pursued with minimal public backlash.xliv

b. The U.S. government has been supportive of similar efforts in partner nations, such as the

Sapphire-network in Canada; however the U.S. intelligence community is reluctant to fully

share information with Japan at this time.xlv

c. While Japan possesses a substantial SSA data collection capability, there are technical

limitations in the software necessary to facilitate data sharing with the U.S. xlvixlvii

Based on this analysis, the U.S. should conclude a comprehensive two-way information

sharing agreement with Japan in the field of SSA. An enhanced Japanese SSA capability will

allow the United States to utilize key Japanese geographical advantages towards creating greater

combined security for space assets and contribute positively to regional security through

enabling a more transparent environment.

Positioning, Navigation, and Timing

Another area in which Japan is currently advancing is through the QZSS, which is

designed to provide a regional-scale PNT function similar to GPS in the United States or China’s

30

BeiDou system. Endeavoring to expand the satellite constellation to seven, 2015’s budget for

QZSS increased by roughly 18 percent to ¥22.3 billion (~$187.3 million).xlviii

Does it meet the threat to Japan’s security?

a. Since the first launch in September of 2010, QZSS satellites have provided an important

indigenous source of navigation data for Japan, which assists in HADR missions and which

could provide operational data for other missions to the SDF in the future. xlix

b. The regional nature of QZSS provides a key geographical comparative advantage for Japan

within a combined U.S.-Japan defense posture through promoting the key space security

concepts of resiliency and redundancy via interoperability with GPS.

c. QZSS navigation is inherently dual-use, and the program’s civilian functions have yet to

draw criticism. Interoperability with GPS or use by the United States for military purposes

could potentially be carried out clandestinely. Use of QZSS by Japanese forces for precision

weapon guidance may cause a backlash as such weapons are more offensive in nature.

Does it deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration?

a. Japanese PNT capabilities could lead to greater U.S.-Japan defense integration through

greater information sharing and the redundancy and resiliency in regional navigation and

precision guidance capabilities created through the interoperability between QZSS and GPS.

b. As the United States becomes more dependent on such redundancies to provide a backup for

its own regional capabilities, America’s stake in and commitment to Japan’s defense is

visibly increased.

c. Interoperability between GPS and QZSS could potentially leverage a deterrent effect on

ASAT program development if these programs are no longer seen as feasible or cost-effective

in the face of significantly expanded regional constellations, reducing the U.S. burden to

mitigate these threats through hardening, disaggregation, and rapid replacement capabilities.

Can it be implemented?

a. The Japanese public enjoys utilizing the civilian applications of QZSS and any financial or

security burden created through application to military uses is negligible.

b. While QZSS satellites are produced by Japanese companies, ground stations exist in Guam

and Hawaii. Hosting GPS packages on future QZSS satellites is under discussion. GPS/QZSS

interoperability has been a core feature of the program from the design phase.

c. One QZSS satellite is fully operational with three more scheduled for launch by 2017, with

funding for a further three. Questions of military interoperability are legal and organizational

in nature rather than technical.l

Based on this analysis, the U.S. should work to deepen interoperability between QZSS and

GPS. QZSS systems can provide key redundancy and resiliency to American GPS capabilities in

the region while ensuring smooth interoperability between U.S. and Japanese forces. The dual

nature of QZSS also renders it resistant to domestic and regional opposition.

31

Implementation and Conclusion

The successful implementation of our policy recommendations would reliably meet the

threat to Japan’s security and significantly deepen U.S.-Japan defense integration. However, they

face financial, institutional, and psychological barriers. The obstacles to promoting ISR sharing

are mostly institutional. Attaching GPS modules to QZSS represents a relatively minor financial

cost, but the involved Japanese actors must be convinced that this form of interoperability is

essential in countering the regional threat. By emphasizing key resiliency and redundancy

capabilities gained, and demonstrating these capabilities in military exercises, Japanese decision-

makers should be assuaged of any concerns. Similarly, signing a two-way SSA information

sharing agreement largely depends on the U.S. military and intelligence communities being

convinced that Japan is a reliable ally who can meaningfully contribute and maintain the

integrity of classified information. Substantial support within the DoD and DoS, and strict new

penalties, enacted under Japan’s 2013 State Secret’s Law, can be leveraged in this effort.

Supporting new doctrine, platforms, and programs, however, will impose significant

financial and legal challenges on the United States. The F-35 and SM-3 Block IIA will incur

continuing annual financial commitments, while the U.S.-borne effort associated with enabling

Japan to expand their Aegis-equipped destroyer fleet is mostly legal. Strengthening Japan-

Australia-U.S. security partnerships will require a Status of Forces Agreement between Japan

and Australia. Moreover, promoting Japan to a full partner in the Talisman Saber/Sabre exercises

implies a minor adjustment within the U.S. military.

From Japan’s perspective, many of these costs are higher. For example, each new Soryu-

class submarine costs ¥64 billion (~$640 million)li, each F-35 costs about ¥16 billion ($160

million)lii, and the new amphibious force necessitates 2,000-3,000 personnel and 52 amphibious

32

vehicles. Granted, many of these have already been budgeted for, but these investments must

continue.

These obstacles, though impressive, are surmountable. As demonstrated by Abe’s recent

speech to the U.S. Congress and the 2015 guidelines revision, there is abundant willingness to

expand the nature and scope of the alliance. Abe hailed this partnership as “an alliance of

hope.”liii Japanese military normalization is advancing at an unprecedented pace and the U.S.

should seek to promote its continuation as a form of supporting the rebalance to the Asia-Pacific

and ensuring regional security and influence.

Increased U.S.-Japan defense cooperation is not limited to the recommendations of this

paper. The U.S.-Japan security alliance, a hallmark of the region for seven decades, continues to

expand into new dimensions as political ties and technological levels have increased. This bodes

well for the future of the U.S.-Japan alliance, but America must find the specific aspects of this

transformation that offer the most potential for security in a dynamic region.

33

Appendix A:

Key Assumptions

In light of the prospective nature of this project and the potential for rapid change in

relevant conditions, this paper operates under several key assumptions.

The Japanese government will continue to move towards military normalization

Japan’s move towards a more robust security posture is a lengthy and ongoing process

with roots in the early days of the Cold War. This process has been supported to varying degrees

by a wide variety of prime ministers and their administrations. Recent steps such as the July 1st,

2014, reinterpretation of Article Nine to allow the Japan Self-Defense Forces to participate in

collective self-defense in areas outside of Japan, the relaxation of controls on arms exports to

regional partners, and record defense budgets show a stark acceleration in a long-running trend.

We will be working under the assumption that this trend will continue as Japan pushes for a

greater role, both regionally and internationally, even in the face of short-term economic

difficulties or electoral setbacks for the Liberal Democratic Party.

The United States will continue to support the military normalization of Japan

The United States has already voiced their support for the Japanese military

normalization process, as exemplified by Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter’s visit to Japan and

the revision of the U.S.-Japan Defense Cooperation Guidelines in April 2015. We will be

working under the assumption that U.S. support of Japanese military normalization will continue

as it remains in the strategic interest of the U.S. to do so.

The PRC will continue to rise and become an increasingly dominant power in the region

While the PRC certainly faces significant economic and demographic challenges in its

future, these are unlikely to exert a substantial negative influence on its overall standing in the

region over the near- to mid-term. The Chinese Communist Party has carefully managed the

PRC’s rise over the last three decades, a behavior clearly seen in the steady annual increases in

its defense spending that are easily absorbed by the country’s rate of economic growth. We will

be working under the assumption that Chinese economic and military power will continue to

grow over the next several years.

Territorial conflicts will continue to plague the relationship between Japan and the PRC

The dispute over the sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands has continued between Japan

and the PRC since the return of the islands to Japanese administration in 1972. Several flare-ups

in this dispute over the last decade have led to gray zone scenarios that have left the two nations

on the brink of armed conflict. We will be working under the assumption that no significant

rapprochement will occur in the mid- to near-term that might substantially alter Japan’s

assessment of the level of strategic threat posed by the PRC.

34

Appendix B:

History of the National Police Reserve and Self-Defense Force, 1954-2015

Japan's military has had a particularly defensive orientation, resulting in an ongoing

contradiction between its pacifism and its growing role in international security. The SDF is not

designated as a regular military under Article Nine of Japan's constitution, which renounced the

right of belligerency and maintenance of military forces. The subsequent formation of a military

force has thus been discussed in terms of self-defense, beginning in the 1950s with the start of

the Korean War. Following the deployment of American occupation troops to the Korean theater,

which left Japan largely defenseless, Tokyo announced in July 1950 the creation of the National

Police Reserve. That force was expanded in 1952 to become the National Safety Forces

following an agreement with the United States that Japanese forces would deal with internal

threats and natural disasters while American forces would handle Japan's external defense. Under

the 1954 Self-Defense Forces Act, the force was reorganized into separate services, the Japan

Ground Self-Defense Force, Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, and the Japan Air Self-Defense

force, which were placed under the control of the newly created Defense Agency. In 2006, that

agency was elevated to a Cabinet-level Ministry of Defense for the first time since World War II.

35

Appendix C:

Unresolved Historical Conflicts

The formation of Japan's military has been undertaken in the context of unresolved

historical conflicts in the region stemming from Japan’s actions during World War II and earlier,

most notably with the ROK and the PRC. Ongoing issues include Japan’s use of so-called

“comfort women” and forced laborers, as well as atrocities carried out during the war. Another

cause of tensions is Japanese treatment of colonialism and war in historical textbooks, which are

said to gloss over Japanese oppression, colonialism, war crimes, and other atrocities. Japan has

been criticized by the ROK and the PRC for not having apologized sincerely enough, an image

that has been reinforced by statements and actions by public officials. The result of these

historical conflicts is widespread anti-Japanese sentiments among the populations of both the

ROK and the PRC, which in turn has sparked backlash among Japanese citizens. These attitudes

have notably hindered ROK-Japan military cooperation agreements in the face of a growing

PRC.

36

Appendix D:

Abe’s Government

While the process of Japan’s military normalization has been one of gradual advances

since the earliest days of the U.S. occupation, the last decade has seen it move to the forefront of

political discourse with a new character of urgency under the leadership of Prime Minister

Shinzo Abe. During the lead-up to his first administration in 2006, Abe expressed a desire for

reinterpretation of Article Nine of the Japanese Constitution to allow Japan to maintain more

robust and capable defense forces, ultimately managing to upgrade the Japanese Defense Agency

to its current status as the Ministry of Defense. Soon after, however, his administration

succumbed to internal scandal.

The return of Abe and the Liberal Democratic Party to power, since December of 2012,

has been marked by notably higher levels of public support and a continued focus on efforts to

expand both the capabilities and range of actions available to the JSDF. While continuing to face

opposition from left-wing political groups as well as Komeito members within his own ruling