Untreated Hypercholesterolemia in an Emergency Department Chest Pain Observation Unit Population

-

Upload

abhinav-chandra -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Untreated Hypercholesterolemia in an Emergency Department Chest Pain Observation Unit Population

ACAD EMERG MED • July 2002, Vol. 9, No. 7 • www.aemj.org 699

Untreated Hypercholesterolemia in an EmergencyDepartment Chest Pain Observation Unit Population

Abhinav Chandra, MD, Scott Compton, PhD, Mark Sochor, MD, MS,Sankalp Puri, MD, Robert J. Zalenski, MD, MA

AbstractObjectives: To describe the prevalence of hypercholes-terolemia in a predominantly African American, inner-city chest pain observation unit (CPOU) patient popu-lation, and to estimate the percentage of patients eligiblefor cholesterol-lowering therapy as indicated by the 2001National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines.Methods: A cross-sectional study design utilizing a con-venience sample of patients from a high-volume urbanhospital CPOU. Patients with chest pain suspicious ofcardiac etiology who had negative initial electrocardio-grams and cardiac markers were assigned to the chestpain protocol. Consenting subjects were screened for hy-percholesterolemia through capillary blood point-of-caretesting with a cutoff of 190 mg/dL. Those who testedpositive had four-hour fasting complete lipid profilesperformed by the central laboratory. Results: There were112 patients enrolled in this study (mean age = 51 years;57% male; and 83% African American). Elevated values

on the screening test were obtained on 28 [25%; 95% con-fidence interval (95% CI) = 16.9 to 33.0] of these patients.These patients were found to have a mean four-hourfasting total cholesterol level of 224 mg/dL, a low-den-sity lipoprotein (LDL) level of 138 mg/dL, a high-densitylipoprotein (HDL) level of 52 mg/dL, and a triglyceridelevel of 168 mg/dL. Of the patients identified throughthe screening test, 54% proved eligible for cholesterol-lowering medications and 91.7% of these patients re-ported an interest in initiating therapy. Conclusions: Inthis study, approximately 25% of inner-city CPOU pa-tients are possible candidates for cholesterol-lowering in-terventions. Benefits of initiating therapy during this po-tential ‘‘teachable moment’’ in a CPOU should beinvestigated in a subsequent multicenter randomizedtrial. Key words: hypercholesterolemia; cholesterol; ur-ban; chest pain observation unit. ACADEMIC EMER-GENCY MEDICINE 2002; 9:699–702.

Each year, approximately 8 million patients areevaluated in emergency departments (EDs) forsymptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndromes(ACSs),1 which are the leading cause of death ofAmericans.2 Increasingly, many of these patientswho are initially ruled as low-risk for ACSs receivefurther evaluation in ED chest pain observationunits (CPOUs). These units have been shown to bea safe and cost-effective way to evaluate low-riskfor ACS patients3 during serial testing for ACS,which usually requires 8 to 12 hours to complete.4

This time spent in a CPOU may be a valuableopportunity to introduce ACS risk-reduction edu-cation and interventions. While the patient is seek-ing medical care, he or she may have increasedmotivation to learn about coronary risk factor as-sessment and modification. Although the effective-ness of starting these interventions has not been es-

From the Division of Emergency Medicine, Duke UniversityMedical Center (AC), Durham, NC; and the Department ofEmergency Medicine, Detroit Receiving Hospital, Wayne StateUniversity (SC, MS, SP, RJZ), Detroit, MI.Received October 12, 2001; revision received March 2, 2002; ac-cepted March 12, 2002.Supported by a grant from the OHEP Center for Medical Ed-ucation.Address for correspondence and reprints: Abhinav Chandra,MD, Medical Director, Clinical Evaluation Unit, Division ofEmergency Medicine, Box 3096, Duke University Medical Cen-ter, Durham, NC 27710. Fax: 919-681-7402; e-mail: [email protected].

tablished in this setting, primary and secondaryprevention trials have demonstrated that aggres-sive lipid-lowering therapy decreases cardiacevents and reduces mortality.5 Unfortunately, treat-ment rates of hypercholesterolemia vary widely,and many candidates for drug therapy go uniden-tified.6 For example, it has been noted in a largeCalifornia health maintenance organization (HMO)population, less than one-fifth of patients seekingtreatments for heart attacks are screened within sixmonths for cholesterol values.7

The objective of this study, therefore, was to as-sess the value of screening for high total choles-terol, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) choles-terol, in a CPOU by estimating the prevalence ofpatients with elevated levels who would be eligibleand willing to receive cholesterol-lowering therapy,as indicated by the current National CholesterolEducation Program (NCEP) guidelines.8

METHODSStudy Design. This pilot study was a prospectivecross-sectional study of primarily African Americanpatients who were at low risk for ACS and beingevaluated in a high-volume urban university hos-pital’s CPOU. Patients with chest pain suspiciousof cardiac etiology who had negative initial electro-cardiograms (ECGs) and cardiac markers were as-signed to the chest pain protocol. While in the

700 Chandra et al. • UNTREATED HYPERCHOLESTEROLEMIA IN CHEST PAIN UNIT

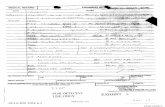

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Low and High (>190 mg/dL) Screened Patients

Low-screen Patients(n = 84)

High-screen Patients(n = 28) p-value

Age—mean (6standard deviation) 52.1 (613.5) yr 48.9 (614.8) yr 0.326Race—African American 62 (82.7%) 16 (84.2%) 0.714Have primary care physician 45 (54.2%) 17 (60.7%) 0.549Willing to take cholesterol-lowering drug if needed 70 (80.9%) 22 (91.7%) 0.782Came to hospital because they thought they were having

a heart attack 54 (66.7%) 15 (57.7%) 0.405History of prior heart attack 15 (18.5%) 4 (14.3%) 0.611

CPOU, patients had serial cardiac markers, ECGs,and risk stratification performed. This study wasapproved by the Wayne State University HumanInvestigations Committee, and informed consentwas obtained from all participants.

Study Setting and Population. All clinically stableadult patients who entered the CPOU were as-sessed for study eligibility. Exclusion criteriaconsisted of chest pain due to trauma, currently re-ceiving treatment with cholesterol-reduction phar-macologic therapy, admission from the CPOU tothe hospital for acute myocardial infarction (MI) orunstable angina, or inability to speak English. Thestudy hospital is an urban, university-affiliated,Level I trauma center with more than 80,000 EDvisits in 2001. The CPOU is located adjacent to theED.

Study Protocol. A self-administered survey wasgiven to eligible patients with standardized writteninstructions, usually read by certified physician as-sistants. After completing the survey, a fingerprickblood test was conducted using the Accu-Check In-stant Plus (Boehringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis,IN) cholesterol evaluation tool. Positive testing onthis initial cholesterol screen was used as an indi-cator for definitive laboratory evaluation. Patientswith preliminary results indicating high cholesterol(total cholesterol value $190 mg/dL) fasted for atleast four hours, and had blood sent for a completelipid profile, with results within 12 hours. Theseresults were provided to the patients before dis-charge, or mailed to them.

To determine the proportion of chest pain pa-tients who were eligible for lipid-lowering drugtherapy, patients were classified into treatmentgroups, as recommended by the NCEP Adult Treat-ment Panel III Report.8 These include:

1. LDL $190 mg/dL and less than 2 cardiovas-cular disease risks (160–189 mg/dL LDL-lowering drug optional).

2. Two or more cardiovascular disease risk factorsand LDL $130 mg/dL with a 10-year risk 10–

20% or LDL $160 mg/dL with a 10-year risk<10%.

3. LDL $130 mg/dL and known cardiovasculardisease or cardiovascular disease risk equiva-lents (100–129 mg/dL LDL-lowering drug op-tional).

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease include: ac-tive smoker, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) <40mg/dL, hypertension, diabetes (cardiovascular dis-ease equivalent), family history of cardiovasculardisease, and age (women aged 55 or older, menaged 45 or older).

Data Analysis. Descriptive statistics [means, stan-dard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs)] were calculated. Chi-square and Student’s t-tests were used to compare patient characteristicsby group (low-screen versus high-screen). All anal-yses were performed using SPSS version 11.0 (SPSSInc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTSA convenience sample of 112 patients was enrolledover a one-year time frame. The majority of pa-tients were male (57.4%), and African American(83%). The mean age of the patients was 51 years(range = 26–91), and 56% reported having a pri-mary care physician. Most (65%) of the patientsstated that they came to the hospital because theythought they were having a heart attack, and 90%stated that they would be willing to immediatelybegin pharmacotherapy if they knew they had highcholesterol levels. A description of the study sam-ple by cholesterol group is shown in Table 1.

Twenty-eight patients (25%; 95% CI = 16.9 to33.0) had a fingerprick screen value above 190mg/dL. Four of these patients did not have theirserum evaluated because of lost or missing sam-ples. Therefore, risk factor data are based on 28 pa-tients and the cholesterol laboratory studies arebased on 24 patients. The average (6standard de-viation) four-hour fasting total cholesterol level forthese patients was 223.6 mg/dL (624.7), the aver-

ACAD EMERG MED • July 2002, Vol. 9, No. 7 • www.aemj.org 701

TABLE 2. Risk Factors of Chest Pain Observation Unit Patients

Low-screen Patients(n = 84)

High-screen Patients(n = 28) p-value

Tobacco use 38 (45%) 12 (43%) 0.749Family history of myocardial infarction 21 (25%) 8 (29%) 0.709Previously told of high cholesterol 15 (18%) 14 (50%) <0.001History of hypertension 49 (58%) 15 (54%) 0.659History of diabetes 15 (18%) 7 (25%) 0.410High-density lipoprotein (HDL) <35 mg/dL 0 1 (4%) —Men aged 45 years or older 32 (38%) 8 (29%) 0.412Women aged 55 years or older 7 (8%) 3 (11%) 0.166

TABLE 3. High-screen Patients Eligible forCholesterol-lowering Therapy

Number (%)PatientsEligible

Eligible for therapeutic lifestyle changesLDL $100 and history of CHD or CHD risk

equivalents* 1 (4.2%)LDL $130 and $2 risk factors 1 (4.2%)LDL $160 and 0 or 1 risk factor 1 (4.2%)

Eligible for diet and pharmacologicintervention

LDL $190 and 0 or 1 risk factor 0 (0%)LDL $130 and 10-year risk 10%–20%, or LDL

$160 and 10-year risk <10% and 2 riskfactors 3 (12.5%)

LDL $130 and history of CHD or CHD riskequivalents 10 (41.6%)

*LDL = low-density lipoprotein (mg/dL); CHD = coronary heartdisease.

age LDL level was 137.7 mg/dL (624.9), the aver-age HDL level was 51.9 mg/dL (617.2), and theaverage triglyceride level was 167.9 mg/dL (695.7).

Patient surveys identified risk factor information,including tobacco use (42.9%), known history of hy-percholesterolemia (50.0%), history of hypertension(53.6%), and family history of MI (16.4%). Twenty-five percent of patients who tested positive for el-evated LDL (>130 mg/dL) had a history of diabe-tes, which is considered a coronary heart diseaserisk equivalent, and thus qualified 54.1% of thehigh-screen patients for diet and pharmacologictherapy. Additionally, as shown in Table 2, high-screen patients more often had knowledge of hav-ing high cholesterol (18% vs 50%, p < 0.001), al-though the groups were similar regarding theirknowledge of the risk factors of smoking status, fa-milial history of MI, diabetes, and age.

Of the 24 patients with complete lipid profiles,three (12.5%) met NCEP criteria for therapeutic life-style changes (i.e., diet and exercise), while 13(54.2%) met criteria for diet and pharmacologic in-tervention. Table 3 shows each of these 16 patients’criteria for meeting the treatment recommendationsput forth by the NCEP Adult Treatment Panel IIIReport.8

DISCUSSIONThe major findings of this study were that a largeproportion (25%) of patients in an urban ED CPOUshowed evidence of untreated hypercholesterole-mia, and that 57.1% of those patients were eligiblefor lipid-lowering therapy. This implies that in thisenvironment, there is a potential opportunity forthe immediate initiation of therapy in these pa-tients, a management approach that has previouslybeen advocated.9 Furthermore, there is evidencethat a safe and effective cardiac-event-loweringtherapy exists. For example, using data obtained inthe LIPID, CARE, and WOSCOPS studies, Simes etal.10 have identified a 20% relative risk reduction forall-cause mortality, and a 24% coronary-specificmortality relative risk reduction associated with

statin use for ACS and non-ACS patients. Addition-ally, the MIRACL trial11 suggested that for patientswith ACS, lipid-lowering therapy reduces recurrentischemic events in the first 16 weeks.

Unfortunately, detection of hypercholesterolemiais low nationally,12 and innovative approaches toidentifying these patients are needed. Given that 8million patients present to EDs for symptoms sug-gestive of ACS each year and a segment of thesepatients will be classified as low-risk and placed inCPOU-type facilities, a strong argument for theneed of an ED cholesterol-screening program canbe made. We hypothesize that CPOUs are favorableenvironments for several reasons: First, CPOU pa-tients are a relatively captive audience who may beexperiencing a teachable moment due to the factthat many sought treatment for fear of a heart at-tack. Second, there is sufficient fasting time (at least4 hours), and most would be willing to accept anintervention in the CPOU, as shown by the willing-ness of our study participants to initiate therapy(91.7%) if needed.

Within the setting of CPOUs, an educational in-tervention could be easily introduced. Patients

702 Chandra et al. • UNTREATED HYPERCHOLESTEROLEMIA IN CHEST PAIN UNIT

could be supplied with educational materials thatidentify the benefits of cholesterol reductionthrough diet, exercise, and pharmacologic interven-tion. Additionally, this study justifies further trialsto determine the benefits of initiating cholesterol-lowering therapy in a CPOU environment. Poten-tially, patients could be prescribed a cholesterol-lowering agent while in the CPOU, with follow-upinstructions for their primary care physician.

LIMITATIONSSeveral limitations are noted in this pilot study, in-cluding sample size (n = 112), use of a single hos-pital setting, a large segment of the patients’ beingof the same race, and obtainment of data as a con-venience sample. Population-based investigationsshould be conducted at centers more representativeof the general population.

CONCLUSIONSHypercholesterolemia identification can be reliablyperformed in ED chest pain observation units.These findings provide preliminary support for theneed for cholesterol screening and treatment pro-grams initiated in CPOU patients.

References

1. Roberts R, Kleiman NS. Earlier diagnosis and treatmentof acute myocardial infarction necessitates the need for a‘new diagnostic mind-set.’ Circulation. 1994; 89:872–81.

2. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics An-nual: 1996. Geneva: WHO, 1998.

3. Zalenski RJ, Rydman RJ, Ting S, Kampe L, Selker HP. Anational survey of emergency department chest pain cen-ters in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 1998; 81:1305–9.

4. Ross MA, Naylor S, Compton S, Gibb KA, Wilson AG.Maximizing use of the emergency department observa-tion unit: a novel hybrid design. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:267–74.

5. Frolkis JP, Zyzanski SJ, Schwartz JM, Suhan PS. Physi-cian noncompliance with the 1993 National CholesterolEducation Program (NCEP-ATPII) guidelines. Circula-tion. 1998; 98:851–5.

6. Danias PG, O’Mahony S, Radford MJ, Korman L, Silver-man DI. Serum cholesterol levels are under evaluatedand under treated. Am J Cardiol. 1998; 81:1353–6.

7. Baker B. Lipid levels get missed in new-onset angina. In-tern Med News. 1999; 40.

8. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the NationalCholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel onDetection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cho-lesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA.2001; 285:2486–97.

9. Hunninghake DB. Post-discharge lipid management ofcoronary artery disease patients according to the newNational Cholesterol Education Program guidelines. AmJ Cardiol. 2001; 88:37K–41K.

10. Simes J, Furberg CD, Braunwald E, et al. Effects of pra-vastatin on mortality in patients with and without coro-nary heart disease across a broad range of cholesterollevels. The Prospective Pravastatin Pooling Project. EurHeart J. 2002; 23:207–15.

11. Schwartz GG, Oliver MF, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Rationaleand design of the Myocardial Ischemia Reduction withAggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) study thatevaluates atorvastatin in unstable angina pectoris and innon-Q-wave acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol.1998; 81:578–81.

12. Gotto AM Jr. Overview of current issues in managementof dyslipidemia. Am J Cardiol. 1993; 71:3B–8B.