Unequal cities of spectacle and mega-events in China · 2013. 1. 29. · spectacles, discussing...

Transcript of Unequal cities of spectacle and mega-events in China · 2013. 1. 29. · spectacles, discussing...

-

This article was downloaded by: [LSE Library]On: 29 January 2013, At: 01:33Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

City: analysis of urban trends, culture,theory, policy, actionPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccit20

Unequal cities of spectacle and mega-events in ChinaHyun Bang ShinVersion of record first published: 18 Dec 2012.

To cite this article: Hyun Bang Shin (2012): Unequal cities of spectacle and mega-events in China,City: analysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy, action, 16:6, 728-744

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.734076

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representationthat the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of anyinstructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primarysources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly orindirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccit20http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.734076http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditionshttp://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

-

Unequal cities of spectacle andmega-events in ChinaHyun Bang Shin

This paper revisits China’s recent experiences of hosting three international mega-events: the2008 Beijing Olympic Games, the 2010 Shanghai World Expo and the 2010 Guangzhou AsianGames. While maintaining a critical political economic perspective, this paper builds upon the lit-erature of viewing mega-events as societal spectacles and puts forward the proposition that thesemega-events in China are promoted to facilitate capital accumulation and ensure socio-politicalstability for the nation’s further accumulation. The rhetoric of a ‘Harmonious Society’ as well aspatriotic slogans are used as key languages of spectacles in order to create a sense of unity throughthe consumption of spectacles, and pacify social and political discontents rising out of economicinequalities, religious and ethnic tensions, and urban–rural divide. The experiences of hostingmega-events, however, have shown that the creation of a ‘unified’, ‘harmonious’ society ofspectacle is built on displacing problems rather than solving them.

Key words: mega-events, spectacles, accumulation, nationalism, China

Between 2001 and 2004, China’snational population was captivatedby the news of three international

mega-events awarded to its major cities:the 2008 Summer Olympic Games toBeijing, the 2010 World Expo to Shanghaiand finally the 2010 Summer Asian Gamesto Guangzhou. Hosted by the three mostinfluential and affluent cities in mainlandChina, these three spectacles came to dom-inate the top urban and regional develop-ment policy agendas in the coming yearsof preparation. This paper is largely con-cerned with scrutinising these mega-eventspectacles, discussing what role theymight have played in China. The paperparticularly draws on Guy Debord’sSociety of Spectacle (1967, 1988), and triesto reinterpret what it would mean in con-temporary urban China contexts.

For many decades, mega-events such as theOlympic Games have been largely the

exclusive domain of cities from the developedWestern world. For instance, apart from thethree Summer Olympiads in Tokyo (1964),Mexico City (1968) and Seoul (1988), allother Games until 2004 were held inWestern cities. As for the World Expo thatwas first held in London in 1851, it was alsodominated by the industrial West until the1970s, after which Japan and subsequentlySouth Korea came to host some of the latestexpositions. In line with the post-Fordist tran-sition of major Western economies and theconcentration of mega-events in post-indus-trial cities, mega-events have been regardedas playing an instrumental role of spurringthe consumption-based economic develop-ment (Burbank et al., 2001). This involvedthe provision of sporting complexes, conven-tion centres, entertainment facilities and sup-porting infrastructure, while it was hopedthat the expected international recognition ofhost cities would also raise their global

ISSN 1360-4813 print/ISSN 1470-3629 online/12/060728–17 # 2012 Taylor & Francishttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.734076

CITY, VOL. 16, NO. 6, DECEMBER 2012

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

profile in the quest for mobile capital (Short,2008). Central government grants were alsofrequently regarded as being a major motifbehind mega-event promotion by cities thatexperienced fiscal problems (Andranovichet al., 2001; Cochrane et al., 1996).

Did China’s mega-events provide similarexperiences as in the West? What would bethe significance of these events for China? Dis-cussions of mega-events in the developingworld tend to focus on the role of mega-events in raising the host city’s profile in inter-national relations or in addressing particularagendas in national politics (for example, seeVan der Westhuizen, 2004; Steenveld and Stre-litz, 1998; Black, 2007). More socially orientedattention has often highlighted detrimentalimpacts on the urban poor as part of beautifica-tion projects to transform host cities’ urbanlandscape (Bhan, 2009; Greene, 2003;Newton, 2009). While maintaining a criticalpolitical economic perspective, this paperattempts to build upon the emerging literatureof viewing mega-events as societal spectacles(see Broudehoux, 2010; Gotham, 2011) andputs forward the proposition that thesemega-events in China are promoted as ameans to create ‘unified space’ (Debord,1967) for the purpose of both capital accumu-lation and socio-political stability for furtheraccumulation. This paper argues that this cre-ation of ‘unified space’ is an attempt to pacifysocial and political discontents rising out ofeconomic inequalities, religious and ethnic ten-sions, and urban–rural divide. The rhetoric ofa ‘Harmonious Society’ and the ‘Glory of theMotherland’, as put forward by the top leader-ship of the Chinese Communist Party, hasbecome the key language of spectacles. Theexperiences of hosting mega-events, however,have shown that the creation of a ‘unified’,‘harmonious’ society of spectacle is built ondisplacing problems rather than solving them.

Mega-events and China’s cities of spectacle

Awarding the 2008 Olympic Games host citystatus to Beijing was shortly before the acces-sion of China to the World Trade

Organization in September 2001. While theOlympic Games itself was awarded toBeijing, it was received as an award to thewhole nation. In particular, the winning ofthe host city status was a compensation forChina’s previous dramatic loss1 to Sydneyin the bid competition for the 2000 SummerOlympiad back in 1993. The timing of this1993 competition could not have beenworse for China, which was just coming outof the standstill of economic reform policiesafter the violent crackdown on democracymovements in 1989. Its vivid memoryformed the basis of many internationalhuman rights organisations’ fierce oppositionto awarding the Olympiad to China at thetime.

The subsequent bid for the 2008 SummerOlympic Games came with the changinginternational atmosphere. Instead of impos-ing democratisation as a pre-condition ofawarding the Games to Beijing, moresupport was garnered for using the Gamesas an instrument of facilitating democracy inChina (Close et al., 2007). The experience ofSouth Korea was often cited as a precedingexample: it was thought that the 1988 SeoulOlympic Games acted as a catalyst to SouthKorea’s democratisation in the mid-1980s,partly due to the global pressure on theregime through its intense media exposure(Black and Bezanson, 2004). China’s acces-sion to the World Trade Organization in2001 and the success of the 2008 Olympicbid gave a further signal to the internationalcommunity that China was becoming moreintegrated with the world. The results weresubsequent successes with Shanghai’s bidfor the 2010 World Exposition in December2002 and Guangzhou’s for the 2010Summer Asian Games in July 2004.

China’s mega-event troika all took placeduring the three-year period between 2008and 2010: the temporal concentration ofthese major international mega-events inChina created urban spectacles that wentbeyond the host cities and reached thewhole nation. For China, however, spectacleswere not entirely new in its modern era. Not

SHIN: UNEQUAL CITIES OF SPECTACLE AND MEGA-EVENTS IN CHINA 729

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

so long ago in the 1960s and 1970s, the entirecountry was engulfed in the fervour of theCultural Revolution, which involvedpopular movements and the intense mobilis-ation of revolutionary slogans, political cam-paigns and violence to launch a ‘class war’against so-called revisionists. Guy Debordhimself refers to China’s experience whenelaborating on his discussion of the ‘concen-trated spectacle’, which is associated withthe constant use of violence (for instance,under fascism) and iconic political leaders asreifications of spectacular moments (1967).

‘Its spectacle imposes an image of the goodwhich subsumes everything that officiallyexists, an image which is usually concentratedin a single individual, the guarantor of thesystem’s totalitarian cohesion. Everyone mustmagically identify with this absolute star ordisappear. This master of everyone else’snonconsumption is the heroic image thatdisguises the absolute exploitation entailed bythe system of primitive accumulationaccelerated by terror. If the entire Chinesepopulation has to study Mao to the point ofidentifying with Mao, this is because there isnothing else they can be.’ (Debord, 1967,p. 50)

Guy Debord’s arguments about the societyof spectacle suggest the rise of a societywhere the ‘social relation between people . . .is mediated by images’ (1967, p. 24) andwhere lived reality is subordinated to andaligned with images that falsify the reality(p. 25). Spectacles function ‘as a means of uni-fication’ by creating ‘delusion and false con-sciousness’ among otherwise isolated andseparate individuals (p. 24). What is beingcreated is a ‘type of pseudocommunity’ thatconceals separation in reality (p. 116).Debord’s subsequent commentaries on thesociety of spectacle in his 1988 publicationargued for the qualitative transformation ofthe society into that of ‘integrated spectacle’:this was a dialectic synthesis of the diffuseand concentrated spectacles, with a heavierweight given to the more victorious ‘diffusespectacle’ (Debord, 1988). The domination

of ‘integrated spectacle’ in late capitalisteconomies dictates that individual life be con-sumed by the immense accumulation of spec-tacles, while the use of violent measures is toaid the domination of this status quo. The useof violence as the state power is justified bythe identification of external threats such asterrorism.

The strengthening importance of imagesand spectacles corresponds to the changingaccumulation needs and strategies in con-temporary cities especially in the post-industrial West (Hall, 1994). Place market-ing and branding cities have come to be animportant tool for urban developmentaimed at attracting investors and tourists(Kavaratzis and Ashworth, 2005). Therecent popularity of celebrity architectsand their products for city marketing couldalso be understood along this line (Knox,2012). Mega-events such as the OlympicGames would mesh all these into an ensem-ble, producing spectacular images as well asspectacular urban spaces to meet thehosting requirements of such events andmaximise host cities’ potential (and largelyeconomic) gains. Under these circumstances,mega-events as urban spectacles have gainedan increasing degree of popularity amongurban elites as a means of staging cities inthe world (Short, 2008).

A handful of preceding works on mega-events resort to the use of Guy Debord’sSociety of Spectacle framework. Forinstance, Kevin Gotham (2005, 2011) exam-ines the US experiences of hosting urban fes-tivals and the world fair to discuss the extentto which mega-events that functioned as ameans to conceal inherent social inequalitiescould also operate as ‘spectacles of contesta-tion’, giving rise to the formation of resistantagendas. Anne-Marie Broudehoux (2007)also discusses how urban spectacles such asthe Olympic Games accompanied the con-struction of spectacular monumental archi-tecture at the expense of cheap migrantlabour and land confiscation. Her latestwork also includes the pre-eminence ofspectacular architecture, which serves the

730 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

need of regulating the society through disse-minating particular images of China (Brou-dehoux, 2010). The underlying theme ofthese preceding works is the extent towhich spectacles play the role of falsifyingrealities.

While it is important to understand howspectacles conceal realities and at the sametime conceive resistance, it would also beessential to examine why spectacles areincreasingly sought after by China’s localand central states. One of the explanations,which this paper accentuates, is the specta-cle’s additional function of promoting a dia-lectic process of (a) aiding the creation of a‘unified space’ (Debord, 1967, p. 114) toenable accumulation and profit-led commod-ity production, and (b) promoting ‘a con-trolled reintegration’ of isolated individualsto the governing system in order to address‘planned needs of production and consump-tion’ (in other words, accumulation needs).This reintegration is not to salvage peoplefrom isolation and separation, but to bring‘isolated individuals together as isolated indi-viduals’, while the isolation is filled ‘with theruling images’ (p. 116). This function of spec-tacle as addressing accumulation needs wasbriefly taken up by Julie Guthman (2008) inher short editorial piece on ‘accumulationby spectacle’, regarded as one of the ‘teach-able moments’ that could be learnt from theobservation of the Beijing Olympic Games.

In this regard, this paper accentuates thespectacle’s function of aiding capital accumu-lation through the examination of China’sexperiences of hosting the Olympic Games,the World Expo and the Asian Games. Thenext section discusses how the preparationfor spectacles contributed to the accumu-lation needs of host cities through spatialrestructuring and investment in the builtenvironment. Then, in the ensuing section,the paper will examine how the sense of‘pseudo-community’ feeling was promotedby the state through the use of particularlanguages, which meant to create the senseof unity through the consumption ofspectacles.

Spectacles and accumulation

In their discussion on American cities’experiences of hosting the Olympic Games,Burbank et al. (2001) frame mega-events asfacilitating the development of a ‘consump-tion-oriented economy’, which focuses oncreating places (convention centres, themeparks and sports complexes) for visitors’pursuit of pleasure. Through the deploymentof regime politics that bring together localbusiness interests and financially weak localgovernments, mega-events are thought tocontribute to the promotion of local entre-preneurial activities for the survival andgrowth of host cities in the increasingly com-petitive global and domestic market (ibid.).While such propositions have some potentialto explain mega-events hosted in post-indus-trial cities of the West, it is questionable howthey would apply to the examination ofmega-event experiences in rapidly industria-lising emerging economies such as China.While local state entrepreneurialism explainsthe ascendancy of major Chinese cities inthe global market, China is also noted forits authoritarian strong state that emphasisespolitical centralisation under the leadershipof the Chinese Communist Party (Wu,2003; Chien, 2010). In this regard, the recentexperiences of hosting mega-events in Chinaare integrated with China’s larger politicaleconomic projects, while the resulting place-specific accumulation strategies have beenled by the local states under the auspices ofthe central state.

The three mega-events in China took placein three cities that had been leading China’srapidly developing economies and itsregions. They also represented core industrialregional clusters: Beijing representing theBeijing–Tianjin–Tangshan region, Shanghai,the Yangtze River Delta region and finallyGuangzhou, the Pearl River Delta region.These mega-city regions are the key areasfor implementing China’s latest regionaldevelopment strategies organised by theChinese central government. Beijing, Shang-hai and Guangzhou, as centres of these

SHIN: UNEQUAL CITIES OF SPECTACLE AND MEGA-EVENTS IN CHINA 731

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

mega-city regions, are the sites of capitalaccumulation and the commanding centresof their respective regions, though the for-mation and development of these mega-cityregions may accompany continuous nego-tiations and territorial conflicts (Ma, 2005;Xu and Yeh, forthcoming). Under these cir-cumstances, the three mega-events could beregarded as having presented host citieswith an opportunity to consolidate theireconomic and political achievements at bothregional and national scales, while facilitatingtheir pursuit to become ‘world-class’ cities inparticular. To some extent, these goals tend toalign with the central state’s national andinternational ambition. This would havebeen particularly the case for Beijing andShanghai, while for Guangzhou, the centralstate influence might have been less influen-tial, given the regional (Asian rather thanglobal) scale of the mega-event itself and theposition of Guangzhou in the nationalpolitics.2

One of the ways in which mega-events ascontributing to capital accumulation couldbe seen in the promotion of fixed assetsinvestment in host cities is through spendingon urban infrastructure and redevelopment.Looking at the Games finance, one of Beij-ing’s high-ranking officials claimed thatabout 15 billion yuan were direct spendingon Games-related venue preparation andGames operation, while 280 billion yuanwere spent on infrastructure projects includ-ing expanding public transport networkssuch as new metro lines (see Shin, 2009,p. 138).3 This is almost equivalent to Beijing’stotal urban fixed assets investment in 2006(308.6 billion yuan), and amounts to a littleless than one-third (31.6%) of the totalurban fixed assets investment between 2005and 2007 when the preparation for the Olym-pics intensified (Beijing Municipal StatisticsBureau, 2011).

As for Guangzhou, the provision of itspublic facilities also received the greatestemphasis. It was reported that the originalestimate of the Asian Games-related expendi-ture, as proclaimed by Guangzhou Mayor

Wan Qingliang, was 122.6 billion yuan: thisincluded the expenditure on Games oper-ation costs, but nearly 90% was reportedlyinvested in infrastructure and urban redeve-lopment projects. Unofficial figures specu-lated by a senior representative at theGuangzhou People’s Congress showed aneven higher estimate of 257.7 billion yuan asthe total investment to host the AsianGames spectacle (Shenzhen Daily, 2011;Times of India, 2011): this was almost equiv-alent to Guangzhou’s total urban fixed assetsinvestment in 2009 (Guangdong StatisticsBureau, 2011). Even if we took the conserva-tive figure from the government, it againsuggested that the investment in infrastruc-ture and urban redevelopment was far moreimportant than the Games itself, andassumed a substantial share in the city’stotal fixed assets investment. A similar storycould be repeated for Shanghai that report-edly spent about US$45 billion on preparingthe city for ‘the biggest and most expensiveparty’ (Guardian, 2010b).

The role of mega-events in triggering urbanaccumulation is further demonstrated bytheir influence on host cities’ spatial restruc-turing. A couple of key examples are pre-sented here. In Guangzhou, the AsianGames preparation became instrumental toGuangzhou’s long-term development goalsof constructing growth centres, one ofwhich is the Guangzhou New Town (here-after GNT), located in the centre of Panyudistrict that received an increasing degree ofgovernment attention for Guangzhou’ssouthward expansion. The GNT was desig-nated as one of the two growth cores (theother being the Tianhe New Town) by themunicipal government when it laid outspatial development strategic plans immedi-ately after Guangzhou’s successful bid forthe Asian Games. The GNT was to be devel-oped on a planned area of 30 square kilo-metres in the rural fringe area of Panyudistrict, adopting a ‘new town construction’strategy. It was located about 25 kilometresto the south from the new central businessdistrict in the Tianhe New Town, and about

732 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

12 kilometres south-east from the Guangz-hou Higher Education Mega Center (alsoknown as Guangzhou University Town).The GNT would be regarded as one of thepivotal projects for the urbanisation ofPanyu district. The Asian Games preparationmade it possible for the GNT to see the firstphase of its development through the posi-tioning of the 2.73-square-kilometre (nearlyequivalent to the combined size of HydePark and Kensington Gardens in London)Asian Games village in the GNT centre’snorth-eastern corner. The construction ofthe Asian Games village was to involve realestate projects by developers who acquired30-year rights to manage facilities and sellcommercial houses.

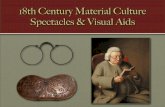

The development of the Asian Gamesvillage also testified to Guangzhou’s interestin using metro line development to lead theurbanisation process, adopting HongKong’s transit-oriented development(Cervero and Murakami, 2009) that makesuse of the combination of rail and propertydevelopment as a means to finance infrastruc-ture construction. You-tien Hsing in her dis-cussion of new town development in Nanjingalso reports a similar development strategyapplied there (2010, p. 107). The municipalexpropriation of farmland for conversioninto urban construction land accompaniedthe installation of infrastructure and apublic transport network such as metro con-nections in order to maximise developmentgains by attracting potential developers andincreasing land use premium. As for the con-struction of the Asian Games village, the LineNo. 4 connection to the village site atHaibang, Panyu district, was already com-pleted by the end of 2006 (New Guangdong,2006). This predated the actual constructionof the Asian Games village, which com-menced only in mid-2008 (see Figure 1). Inaddition to this, Guangzhou investedheavily in metro line construction, eithernew lines or existing line extensions, beforethe Asian Games. During the six-yearperiod of preparing for the Summer Asiad,Guangzhou reportedly invested 70 billion

yuan in metro construction, the total lengthof metro lines having expanded to 236 kilo-metres (People’s Daily Online, 2010). Thiswas a considerable increase, given the realitythat as of the end of 2003, a few monthsbefore the city was awarded the AsianGames, Guangzhou was in possession oftwo metro lines in operation (one of themin test running) whose combined line lengthreached only 41.6 kilometres (GuangzhouNet, 2005).4

The experience of Shanghai’s selection ofthe World Expo site also demonstrates howthe city strategically set its eyes on facilitatingfurther redevelopment of central districts ofShanghai that increasingly faced land supplyconstraints. The site was a waterfront area,located about six kilometres to the south ofthe Shanghai Bund. Divided into two partsby the Huangpu River, the site was largely acombination of industrial and residentialuses, having accommodated various indus-trial and power plants, warehouses and ship-yards for China’s oldest shipbuildingcompany. The 5.28-square-kilometreplanned construction area (1.5 times the sizeof New York Central Park) also includedresidential neighbourhoods whose totalpopulation amounted to about 18,000 house-holds according to government sources(Shanghai Municipal Planning and LandResources, 2005). In order to empty the sitefor Expo construction, these residents wereall subject to displacement from 2005 in thename of fulfilling public interests (seeFigure 2). The latest plan for the developmentof the World Expo site was announced inMarch 2011, and included a combination ofcommercial, business, culture and high-endresidential uses (People’s Daily Online,2011). In fact, the hosting of the ShanghaiWorld Expo enabled the city to assemble amassive site for future development purposes,creating another potential growth pole in thesouth of Shanghai’s historic inner-city dis-tricts. This would lead to a substantialincrease in the supply of urban constructionland for development, especially whenShanghai’s total supply of land in 2010

SHIN: UNEQUAL CITIES OF SPECTACLE AND MEGA-EVENTS IN CHINA 733

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

reached around 8.42 square kilometres(Shanghai Daily, 2011).

Spectacles and the rhetoric of aHarmonious Society

The social division of labour based on theconcentration of the means of production inthe hands of a few has produced isolated indi-viduals and over time aggravated inequalitiesin sharing the outcome of social production.In order for capital accumulation to continueunder these circumstances, social and

political stability becomes a pre-condition:when stability is not found, it needs to becreated even by force. This is where specta-cles become a powerful instrument. As forChina, urban spectacles came to be mobilisedas a means to consolidate the Chinese party-state’s legitimacy in the midst of rising econ-omic, political and social costs resulting fromChina’s decades-long endeavour to develop amarket economy.

Economically, while the reform measureshave resulted in the phenomenal growth ofChina’s economy and substantially reducedabsolute poverty, aggravating income and

Figure 1 Cleared sites (2008) and construction of the Asian Games village (2009)(Source: Original satellite images from Google Earth. Images # 2012 Google, # 2012 GeoEye and # 2012 DigitalGlobe)

734 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

wealth inequalities have come to be a majorsource of concern for the governments.Reports suggest that urban China had seenworsening income inequalities, whichresulted from regional income dispersion aswell as the large-scale unemployment fromthe industrial restructuring of the 1990s(Meng, 2004). The country’s income dis-parity as measured by the Gini coefficientwas said to have increased from 0.33 in 1980to 0.46 twenty years later, mainly due to thewidening rural–urban income gap (Chang,2002).5 Inter- and intra-regional inequalitiesbecame acute especially from the mid-1980swhen reform measures began to deepen(Kanbur and Zhang, 2005). Regional dispar-ities were prominent especially due to thewealth accumulated more rapidly in easterncoastal provinces (Dunford and Li, 2010),which benefited heavily from the earlyreform policies of ‘Get Rich First’ and theestablishment of special economic zones.

Urban areas also saw wealth accumulationat a much faster rate than in rural areas(ibid.). The eastern coastal region thereforesaw a much higher proportion of China’snewly emerging super-rich than otherregions: according to the Hurun WealthReport for 2011, the number of China’s mil-lionaires whose estimated assets were worthmore than RMB 10 million reached 960,000,located mostly in the eastern region such asBeijing (170,000), Guangdong (157,000),Shanghai (132,000) and Zhejiang (126,000)(China Daily, 2011).

Politically, while calls for greater ‘rule oflaw’ have been mounting, the aggravatingregional disparities are compounded by thereligious and ethnic tensions centred aroundthe separatist movements in Tibet and Xin-jiang autonomous areas in particular. Theseareas saw frequent violent protests andbrutal oppressions. Such tensions had beenarguably caused by ‘the systemic violation

Figure 2 Shanghai Expo site’s transition over time: 2004 (pre-demolition), 2006 (demolition in progress) and 2010(completed)(Source: Original satellite images from Google Earth. Images # 2012 Google # 2012 DigitalGlobe and # 2012GeoEye)

SHIN: UNEQUAL CITIES OF SPECTACLE AND MEGA-EVENTS IN CHINA 735

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

of basic rights and insensitivity toward min-ority identities by the state’, further provokedby the narrow range of central state responsesto such ethnic and religious conflicts(Acharya et al., 2010, pp. 1–2). Gladneyassociates the rise of ethnic tensions withthe enactment of ‘internal colonialism’ thataimed at assimilating subaltern ethnicgroups in the wider project of Chinesenationalism centred on the dominant Hanidentity (2004). Some recent examples ofheightened tensions rooted in these regionsinclude the violent conflicts that broke outin 2009 in Xinjiang, which resulted in hun-dreds of casualties (Guardian, 2009), andthe deadly attack in Xinjiang’s Kashgarshortly before the Beijing Olympic Games(Aljazeera, 2008).

Socially, the aforementioned urban–ruraland regional disparities have come with thesurge of rural-to-urban migration: theeastern coastal region was the overwhel-mingly popular destination for migrants.Remittance transfer would significantly con-tribute to the economy in their places oforigin, but their lives in destination placeswere confronted by hardships and disadvan-tages in terms of accessing welfare andsocial services. Entitlements to governmentservices in particular had been increasinglyshaped around local citizenship, barringmigrants as outsiders from accessing them(Smart and Smart, 2001). The restructuringof welfare reforms centred on the strengthen-ing of local citizenship tends to be promotedactively by those local governments in moreaffluent eastern provinces. To this extent,the migrants’ unequal conditions in their des-tination places would be the reflection ofregional disparities.

While the Beijing Olympic Games, theShanghai World Expo and the GuangzhouAsian Games were aimed at showcasingChina’s economic and political power to theoutside world, they were also orchestratedoccasions for the Chinese central governmentto showcase the ‘Harmonious Society’ andthe ‘Glorious Motherland’ to the domesticpopulace. As Ni Chen (2012) finds in a

recent study on how mega-events contribu-ted to the branding of national images, thethree mega-events were propagating mess-ages of the Chinese regime’s political legiti-mation to the domestic audience. NicholasDynon (2011) also finds in his study thatmega-events such as the Shanghai WorldExpo were a place-branding spectacle thatwas ‘tied to an ideological narrative that isconcerned ultimately not with Shanghaiitself but rather with the continuing politicallegitimacy of the CCP [Chinese CommunistParty]’ (p. 195).

For instance, the Olympic Games slogansdemonstrated how the Games were con-ceived in the domestic politics. While theproposed slogan at the time of Beijing’s bidfor the 2008 Olympiad was ‘New Beijing,Great Olympics’, the official Games sloganannounced on 26 June 2005 turned out tobe ‘One World, One Dream’ (New Guang-dong, 2005). In the words of Liu Qi whowas the President of the Beijing OrganizingCommittee for the Games of the XXIXOlympiad (hereafter BOCOG) and theformer Beijing mayor, the official slogan‘expresses the firm belief of a great nation. . . that is committed to peaceful develop-ment, a harmonious society and people’s hap-piness’ (ibid.). This corresponded to thestatement by China’s President Hu Jintaowho emphasised in February 2005 that ‘itwas important to balance the interestsbetween different social groups, to avoid con-flicts and to make sure people live safe andhappy life in a politically stable country’(China Daily, 2005). The official Olympicslogan therefore reflected the emphasis bythe top leadership on the promotion of a‘Harmonious Society’ and keeping thenational stability. The emphasis on a harmo-nious society was also visible in the officialslogan of the Guangzhou Asian Games,which was ‘Thrilling Games, HarmoniousAsia’, with a slight re-orientation towardsAsia due to the regional scope of this mega-event. Banners and posters for event cam-paigns were deployed around Beijing, Shang-hai and Guangzhou, carrying the slogans of a

736 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

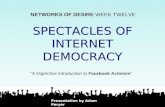

harmonious society, which became theguiding principle of nation-building through-out the period of event preparation (seeFigure 3).

The event preparations in the three citieswere also inundated with symbols of patrioticfeeling and nationalistic sentiments that led tothe glorification of being Chinese and themotherland. The opening ceremonies forthese mega-events, for instance, were specta-cles that amassed a series of symbolic imagesand performances choreographed to deliverparticular patriotic and nationalist messages.At the centre of this choreography was theamelioration of ethnic tensions, toutingethnic harmony. The 2008 Olympic Gamesopening ceremony depicted 2008 drummers(representing the year 2008) followed by 56children in ethnic costumes to representChina’s 55 ethnic minorities and the Han eth-nicity, entering the national stadium whilecollectively holding a Chinese flag. Theensuing performances depicted China’s

imperial histories and its cultural achieve-ments, then fast-forwarded to show thefuture aspiration of ‘One World OneDream’ with China’s astronauts circlingaround the large globe that symbolised theworld. The first line of government campaignslogans for the 2008 Olympic Games was‘For the Glory of the Motherland’, whichcame before the ‘glory of the OlympicGames’ (see Figure 4).

The 2010 Guangzhou Asian Games alsoexhibited a strong Chinese cultural dimen-sion, in this case, southern China’s Lingnanculture rooted in Guangdong province.Filled with Chinese cultural features, theShanghai Expo opening ceremony alsoincluded the appearance of two Tibetan chil-dren who survived the April 2010 earthquakein the Tibetan area of Qinghai provinceshortly before the World Expo opening(Xinhua News Agency, 2010). The WorldExpo’s China Pavilion included exhibitionsof Tibet and Xinjiang, showing how the

Figure 3 Guangzhou: ‘Welcome the Asian Games, Enhance Civility, Build New Styles, and Promote Harmony’ inGuangzhou(Source: Author’s own photograph)

SHIN: UNEQUAL CITIES OF SPECTACLE AND MEGA-EVENTS IN CHINA 737

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

regions had developed over time under Com-munist Party rule and how the ethnicharmony was being achieved (Trouillaud,2010). It hardly portrayed any signs of aviolent ethnic clash, which took place only ayear ago in Xinjiang and resulted in thedeaths of hundreds of protesters and the exer-cise of martial law.

While all the slogans, ceremonies andimages to be aired throughout the countryand to the global audience entailed a heavyemphasis on ‘Chineseness’ and ‘HarmoniousSociety’, the actual preparations were verymuch penalising certain social groups, displa-cing them away from the host city’scontrolled urban landscape. The scale ofevent-related displacement of local residentsappeared to be phenomenal. The Geneva-based Centre on Housing Rights and Evic-tions (hereafter COHRE) reported thatabout 1.5 million Beijing residents wouldhave been displaced during the nine years(2000–2008) leading up to the 2008

Olympic Games (COHRE, 2007). As thisestimate was based on the official data fromthe municipal government, it was not likelyto include migrants. As part of the Olympicspreparation, the municipal government alsoproceeded with the redevelopment of aselected number of former rural villages(known as villages-in-the-city or urbanisedvillages), and it was estimated that about370,500 people (four-fifths of whom wouldbe migrants) might have been displacedbefore the Olympic Games (Shin, 2009,pp. 133–135). As for the Shanghai Expo, theconstruction of the Expo site resulted in thedisplacement of about 18,000 households asindicated earlier, but the municipal-widedemolition and redevelopment during theperiod leading up to the 2010 World Expowould have resulted in a much highernumber of people subject to relocation: Intotal, the official statistics report that476,246 households were subject to reloca-tion between 2003 and 2010 (Shanghai

Figure 4 Beijing: ‘For the Glory of the Motherland, for the Glory of the Olympic Games, Participating in the OlympicGames, Receiving Benefits from the Olympic Games’(Source: Author’s own photograph)

738 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

Municipal Statistical Bureau, 2011, Table 17-7). Again, this figure would have underesti-mated the actual size of displacement, as itis likely to have excluded migrants in theestimation.

Despite the large-scale demolition and dis-ruption to the urban social fabric in hostcities, the three mega-events in China wereheld with minimal domestic disputes,largely aided by the immense power of thelocal and central states in quelling protestsand disturbances. The use of tight securitymeasures as well as the implementation offast-tracked development projects were allcarried out by the authoritarian regimeunder the conditions of what resemblesAgamben’s ‘state of exception’ (2003). Pre-ventive measures such as detention or surveil-lance were taken to keep dissidents orprotesters away from event venues andavoid any chance of public disorder fromthe security perspective (New York Times,2008; South China Morning Post, 2010). Thepreparation for the Beijing Olympic Gamesalso accompanied a whole series of crack-downs on beggars as well as informaltraders such as street hawkers in order tokeep the streets free of trouble and nuisance(Guardian, 2008a). Beijing also kept con-struction sites and factories of certain typesclosed as part of municipal attempts toensure a certain degree of clean air quality,which in turn acted as a driver for migrantconstruction workers’ departure during theGames period (Guardian, 2008b). Strict iden-tity checks were carried out especially withregard to the presence of migrants. Environ-mental improvement as well as security,health care and sanitation were the outspokengovernment claims to justify these discrimi-natory actions. These measures of displacinglocal problems as a means to showcase the‘harmonious’ host city of spectacle becameprecedents for Shanghai and Guangzhou tofollow. Reports suggest that these measureswere largely replicated by the Shanghaimunicipal government as well as Guangdongprovincial and Guangzhou municipal gov-ernments in their preparation for mega-

events. Guangzhou also saw tightened secur-ity measures during the period of hosting the2010 Asian Games, and reportedly carriedout the immigration crackdown on Africantraders and migrants whose number reachedsomewhere between 30,000 and 100,000(Guardian, 2010a). Furthermore, it shouldalso be noted that the heavy dosage of patrio-tic sentiment associated with these high-profile mega-events also made it possible forthe government to win the public opinion,even those of negatively affected such asmigrants (Shin and Li, 2012). The control ofmedia by the Chinese government toproduce pro-event messages also helped toproduce what Lenskyj (2002) refers to as‘manufacturing consent’, which further con-tributed to the isolation of protests anddisputes.

Concluding discussion

The arrival of mega-event spectacles inBeijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou raises thequestion of how spectacles have changedover time in China. The period of the Cul-tural Revolution that saw the domination ofthe ‘concentrated spectacle’ was long gonein the past, and the recent history is filledwith the stories of economic successthrough the implementation of reform pol-icies. Guy Debord’s discussion of thesociety of spectacle reveals how urban specta-cles contribute to the sustenance of capitalaccumulation while alienating people fromexploitative realities. This insight allows usto vividly capture the role of mega-events asspectacles in China.

China’s mega-event troika, that is, the 2008Beijing Olympic Games, the 2010 ShanghaiWorld Expo and the 2010 GuangzhouAsian Games, were awarded to China at itscritical moment of accumulation. Havingbeen endorsed its re-integration with theworld economy through the accession tothe World Trade Organization, Chinaembarked on a greater expansionary phaseof economic development to consolidate its

SHIN: UNEQUAL CITIES OF SPECTACLE AND MEGA-EVENTS IN CHINA 739

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

position as the factory of the world. WithinChina, this came with two spatial strategies.On the one hand, China’s expansion wasaccompanied by the enhancement of its pro-duction capacities through the promotion ofheavy urban and infrastructure investmentsby both the central and local states (Harvey,2012, pp. 57–65). The expansion of state-ledinvestment was particularly pronounced atthe time of the 2008 global financial crisis,resulting in a massive economic stimulipackage. On the other hand, the economicexpansion has been supported by whatDavid Harvey coins as ‘spatial fix’, whichinvolves geographical expansion and restruc-turing to address the inherent contradictionsof capital accumulation (Harvey, 2001). InChina’s regional development contexts, thisrequires the provision of physical infrastruc-ture to facilitate the movement of capital,people (migrants in particular) and productswithin the country, hence the importance ofvarious transport- and communication-related infrastructure (e.g. high-speed railconnection). This also raises the significanceof investing in the central and westernregions in search of additional markets,labour and raw materials as well as exploitingproduction capacities therein.

As noted earlier in this paper, the pre-con-dition to this accumulation strategy would bethe social and political stability in theseregions and in China as a whole, hence theimportance of the promotion of a Harmo-nious Society that comes with nationalismand Chineseness. The three mega-eventsarrived in China when the regional disparitiesand social inequalities were at their highestafter the implementation of reform policies,giving rise to various social and political dis-contents. In this regard, mega-events as spec-tacles aimed to ease the social and politicaltensions experienced by the urban poor,migrants and particularly ethnic groupscentred around the western autonomousregions. The government emphasis on a Har-monious Society and its spectacular displaythrough the mega-event preparation andhosting re-iterates Guy Debord’s statement

that ‘The spectacle is the ruling order’snonstop discourse about itself, its never-ending monologue of self-praise, its self-por-trait at the state of totalitarian domination ofall aspects of life’ (1967, pp. 29–30). The pro-motion of mega-events as spectacles hasallowed the Chinese Communist Party toenforce the alignment of people’s real livesin line with Party policies.

The pre-eminence of nationalism inChina’s politics has led critics such as DruGladney to speculate the possibility ofnationalism emerging as ‘a “unifying ideol-ogy” that will prove more attractive thancommunism and more manageable thancapitalism’ (2004, p. 365). Gladney furtherstates, ‘Any event, domestic or international,can be used as an excuse to promote national-ist goals, the building of a new unifying ideol-ogy’ (ibid.). While the huge amount ofinvestments for the mega-event preparationlays the foundation for future economicdevelopment and facilitates spatial restructur-ing, mega-events as spectacles also serve thefunction of bringing the national populationunder particular ideologies, and in doing so,conceal the social and political ills that thecountry has been suffering from. As GuyDebord succinctly puts it:

‘The spectacle that falsifies reality isnevertheless a real product of that reality.Conversely, real life is materially invaded bythe contemplation of the spectacle, and endsup absorbing it and aligning itself with it.’(1967, p. 25)

Therefore, the mega-event troika in Chinacould be considered as having made contri-butions to China’s accumulation by promot-ing the rhetoric of a Harmonious Society andnationalism as a unifying ideology in order toameliorate ethnic and regional conflicts,which in turn would allow the further expan-sion of accumulation strategies to the ethnicconcentration regions in the central andwestern provinces without political conflicts.The central government’s efforts toimplement more balanced spatial develop-ment strategies seem to have produced some

740 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

positive results with regard to reducingregional disparities from the mid-2000s inparticular, even though urban–rural dispar-ities continued to increase (Dunford and Li,2010; Fan and Sun, 2008). However, thesespatial strategies come with worrying sideeffects. For instance, the Go West policiesin the mid-2000s to redirect state investmentsto the lagged western region resulted in theinflux of the dominant Han population inautonomous regions of Tibet and Xinjiangin particular, which have given rise toviolent conflicts in recent years. The heavydosage of patriotic, nationalist sentiment topromote ‘One China’ as revealed in mega-event hosting could be interpreted as aimingat the achievement of social stability and lit-erally a harmonious society without conflic-tual tensions. These will be the basis offurther capital accumulation that buildsupon the exploitation of migrant workers inparticular and the poorer regions in thecentral and western regions that have largelyacted as the origin of human and naturalresources for the fast-developing easternregion.

At present, it is not very clear whether ornot the state objectives to realise uninter-rupted accumulation as well as a harmonioussociety will be achieved. Guy Debord (1967)highlights the dual nature of spectacle as ‘atonce united and divided’, suggesting that‘The unity of each is based on violent div-isions. But when this contradiction emergesin the spectacle, it is itself contradicted by areversal of its meaning: the division it pre-sents is unitary, while the unity it presentsis divided.’ This point about spectaclesbeing both unitary and divided was takenup by Kevin Gotham (2011) who looks atthe example of Louisiana’s hosting of the1984 World Expo to argue that mega-eventsare also ‘spectacles of contestation’, as theyexhibit ‘highly contradictory representationsthat can generate intense conflict and con-testation’ (p. 209). Unlike in the USA,China’s social, economic and politicalenvironment does not permit the bottom-upcontestation of the ruling regime to blossom

in the open public sphere. Nevertheless,recent reports indicate various signs of organ-ised or sporadic collective resistance, eitherhostile or peaceful, against the local statesand business interests. These range fromlabour actions and ethnic/rural conflicts tohomeowners’ protests against pollutingindustries or forced evictions to rural villa-gers’ rallies against land expropriation(Perry and Selden, 2003; Hsing and Lee,2010). These moments of resistance may con-tinue in the immediate future, given the deepsocietal divide that China faces. As a pro-fessor from the Renmin University of Chinasays, ‘China’s current success is built on 300million people taking advantage of 1 billioncheap laborers. And the unfair judicialsystem and the unfair distribution of wealthare making the challenges even greater’(China Post, 2010).

Spectacles may contribute to the tempor-ary concealment of societal problems, butthey are short of resolving such problems.While the top party leadership may endea-vour to address those sources of social andpolitical discontents, the roots of these dis-contents are so much intertwined with thereform directions that they may not be eradi-cated but simply displaced elsewhere, as wasseen in the experiences of host cities ofChina’s mega-event troika. While GuyDebord’s formulation of an integrated spec-tacle in contemporary capitalist economiesassumes an ‘occult’ controlling centre that is‘never to be occupied by a known leader, orclear ideology’ (1988, p. 9), it is obvious tothe bare eyes in China that the controllingcentre in the country is the Chinese Commu-nist Party. This suggests that while national-ism is clearly on the ascendency and theParty benefits from the increasing sentimentof patriotism at present, its reputation ismore vulnerable to degradation when socialand political discontents further accumulatein times of economic hardship. Therefore,the re-emergence of the use of spectacles inChina to realise state ambitions of accumu-lation and stability might appear to be solidand well guarded for the time being, but

SHIN: UNEQUAL CITIES OF SPECTACLE AND MEGA-EVENTS IN CHINA 741

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

-

along with the time, it might turn out to haveseeded greater cracks in the regulatorysystem.

Acknowledgements

The research, on which this paper is based,benefited from the receipt of the SmallResearch Grant from the British Academyand the STICERD/LSE Annual Fund NewResearcher Award from the London Schoolof Economics and Political Science. I alsothank the anonymous reviewer for construc-tive comments on my earlier draft, and theeditors (Andrea Gibbons, Anna Richter,Dan Swanton and Bob Caterall) for theirhelpful comments and encouragement. Theusual disclaimer applies.

Notes

1 Beijing was leading Sydney until the third round offinal voting, but lost to Sydney in the fourth round by ameagre two votes.

2 The relative importance and hierarchy of the threemega-events were also proven by the fact that theopening announcement for the Beijing OlympicGames and the Shanghai Expo was made byPresident Hu Jintao, while that for the GuangzhouAsian Games was given by Premier Wen Jiabao.

3 According to the International Monetary Fund’sexchange rate archives, GBP 1 was equivalent toabout 10.2224 yuan as of the end of December2010.

4 Guangzhou Net is a website that operates as agateway to the city information, managed by thePropaganda Bureau of the CPC GuangzhouMunicipal Committee.

5 In terms of the ratio between the levels of disposableincome enjoyed by the top 20% and bottom 20% ofincome distribution based on each city’s urbanhousehold surveys, host places all experiencedaggravating income inequalities. While comparabledata are not available for Guangzhou, the level ofincome inequalities in Guangdong province as awhole rose from 3.80 in 2000 to 6.9 in 2010(Guangdong Statistics Bureau, 2001, 2011). Duringthe same period, Shanghai’s income inequalities alsorose from 2.92 to 4.17 and Beijing’s from 3.09 to3.92 (Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau, 2001,2011; Beijing Municipal Statistics Bureau, 2001,2011).

References

Acharya, A., Gunaratna, R. and Wang, P. (2010) EthnicIdentity and National Conflict in China. New York:Palgrave Macmillan.

Agamben, G. (2003) State of Exception. Translated byKevin Attell (2005 edn). Chicago: The University ofChicago Press.

Aljazeera (2008) ‘Deadly attack hits China’s Xinjiang’, 5August, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/asia-pacific/2008/08/2008843587330723.html/ (lastaccessed 10 July 2012).

Andranovich, G., Burbank, M.J. and Heying, C.H. (2001)‘Olympic cities: lessons learned from mega-eventpolitics’, Journal of Urban Affairs 23(2), pp. 113–131.

Beijing Municipal Statistics Bureau (2001) Beijing Statisti-cal Yearbook 2001. Beijing: China Statistical Press.

Beijing Municipal Statistics Bureau (2011) Beijing Statisti-cal Yearbook 2011. Beijing: China Statistical Press.

Bhan, G. (2009) ‘“This is no longer the city I once knew”.Evictions, the urban poor and the right to the city inmillennial Delhi’, Environment and Urbanization21(1), pp. 127–142.

Black, D. (2007) ‘The symbolic politics of sport mega-events: 2010 in comparative perspective’, Politikon34(3), pp. 261–276.

Black, D. and Bezanson, S. (2004) ‘The Olympic Games,human rights and democratisation: lessons fromSeoul and implications for Beijing’, Third WorldQuarterly 25(7), pp. 1245–1261.

Broudehoux, A.-M. (2007) ‘Spectacular Beijing: the con-spicuous construction of an Olympic metropolis’,Journal of Urban Affairs 29(4), pp. 383–399.

Broudehoux, A.-M. (2010) ‘Images of power: architec-tures of the integrated spectacle at the Beijing Olym-pics’, Journal of Architectural Education 63(2),pp. 52–62.

Burbank, M.J., Andranovich, G.D. and Heying, C.H.(2001) Olympic Dreams: The Impact of Mega-eventson Local Politics. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Cervero, R. and Murakami, J. (2009) ‘Rail and propertydevelopment in Hong Kong: experiences and exten-sions’, Urban Studies 46(10), pp. 2019–2204.

Chang, G.H. (2002) ‘The cause and cure of China’swidening income disparity’, China Economic Review13(4), pp. 335–340.

Chen, N. (2012) ‘Branding national images: the 2008Beijing Summer Olympics, 2010 Shanghai WorldExpo, and 2010 Guangzhou Asian Games’, PublicRelations Review (Online First), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.04.003.

Chien, S-S. (2010) ‘Economic freedom and politicalcontrol in post-Mao China: A perspective ofupward accountability and asymmetric decentrali-zation’, Asian Journal of Political Science 18(1),pp. 69–89.

China Daily (2005) ‘Building harmonious society CPC’s toptask’, 20 February, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/

742 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

http://www.aljazeera.com/news/asia-pacific/2008/08/2008843587330723.html/http://www.aljazeera.com/news/asia-pacific/2008/08/2008843587330723.html/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.04.003http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.04.003http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-02/20/content_417718.htm

-

english/doc/2005-02/20/content_417718.htm(last accessed 8 July 2012).

China Daily (2011) ‘Fast growth of economy fuels rise inwealthiest’, 13 April, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2011-04/13/content_12316447.htm(last accessed 10 July 2012).

China Post (2010) ‘China’s unequal wealth-distribution mapcausing social problem’, 28 June, http://www.chinapost.com.tw/commentary/the-china-post/special-to-the-china-post/2010/06/28/262505/p3/China’s-unequal.htm (last accessed 10 July 2012).

Close, P., Askew, D. and Xu, X. (2007) The Beijing Olym-piad: The Political Economy of a Sporting Mega-event. London: Routledge.

Cochrane, A., Peck, J. and Tickell, A. (1996) ‘Manchesterplays games: exploring the local politics of globali-sation’, Urban Studies 33(8), pp. 1319–1336.

COHRE (2007) Fair play for housing rights: Mega-events,Olympic Games and Housing rights. Geneva: Centreon Housing Rights and Evictions.

Debord, G. (1967) Society of Spectacle. Translated by KenKnabb (2009 edn). Eastbourne: Soul Bay Press.

Debord, G. (1988) Comments on the Society of the Spec-tacle. Translated by Malcolm Imrie (1998 edn).London: Verso.

Dunford, M. and Li, L. (2010) ‘Chinese spatial inequalitiesand spatial policies’, Geography Compass 4(8),pp. 1039–1054.

Dynon, N. (2011) ‘Better city, better life? The ethics ofbranding the model city at the 2010 Shanghai WorldExpo’, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 7(3),pp. 185–196.

Fan, C.C. and Sun, M. (2008) ‘Regional inequality inChina, 1978–2006’, Eurasian Geography andEconomics 49(1), pp. 1–20.

Gladney, D.C. (2004) Dislocating China: Muslims, Min-orities and Other Subaltern Subjects. London: Hurst.

Gotham, K.F. (2005) ‘Theorizing urban spectacles’, City9(2), pp. 225–246.

Gotham, K.F. (2011) ‘Resisting urban spectacle: the 1984Louisiana World Exposition and the contradictions ofmega events’, Urban Studies 48(1), pp. 197–214.

Greene, S.J. (2003) ‘Staged cities: mega-events, slumclearance, and global capital’, Yale Human Rights &Development Law Journal 6, pp. 161–187.

Guangdong Statistics Bureau (2001) Guangdong Stat-istical Yearbook 2001. Guangzhou: China StatisticsPress.

Guangdong Statistics Bureau (2011) Guangdong Statisti-cal Yearbook 2011. Guangzhou: China StatisticsPress.

Guangzhou Net (2005) ‘Guangzhou metro (in Chinese:Guangzhou ditie)’, 26 July, http://www.guangzhou.gov.cn/node_2090/node_2386/2005/07/26/112236339662007.shtml (last accessed 20 August2012).

Guardian (2008a) ‘Beijing announces pre-Olympic socialclean up’, 23 January, http://www.guardian.co.uk/

world/2008/jan/23/china.jonathanwatts (lastaccessed 19 May 2012).

Guardian (2008b) ‘Beijing bans construction projects toimprove air quality during the Olympics’, 15 April,http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/apr/15/china.olympicgames2008 (last accessed 10 July2012).

Guardian (2009) ‘Ethnic violence in China leaves 140dead’, 6 July, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/jul/06/china-riots-uighur-xinjiang (lastaccessed 10 July 2012).

Guardian (2010a) ‘China cracks down on African immi-grants and traders’, 6 October, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/oct/06/china-crackdown-african-immigration (last accessed 11July 2012).

Guardian (2010b) ‘Shanghai 2010 Expo is set to be theworld’s most expensive party’, 21 April, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/apr/21/shanghai-2010-expo-party (last accessed 18 July 2012).

Guthman, J. (2008) ‘Accumulation by spectacle and otherteachable moments from the 2008 Beijing Olympics’,Geoforum 39(6), pp. 1799–1801.

Hall, C.M., 1994. Tourism and politics: policy, power, andplace. Chichester, NY: Wiley.

Harvey, D. (2001) ‘Globalization and the spatial fix’,Geographische Revue 2001/2, pp. 23–30.

Harvey, D. (2012) Rebel Cities. London: Verso.Hsing, Y-t (2010) The Great Urban Transformation: Politics

of Land and Property in China. Oxford: Oxford Uni-versity Press.

Hsing, Y-t. and Lee, C.K. eds (2010) Reclaiming ChineseSociety: The New Social Activism. Abingdon:Routledge.

Lenskyj, H.J. (2002) The best Olympics ever? Socialimpacts of Sydney 2000. Albany: State University ofNew York Press.

Kanbur, R. and Zhang, X. (2005) ‘Fifty years of regionalinequality in China: a journey through central plan-ning, reform, and openness’, Review of DevelopmentEconomics 9(1), pp. 87–106.

Kavaratzis, M. and Ashworth, G.J. (2005) ‘City branding:an effective assertion of identity or a transitory mar-keting trick?’, Tijdschrift voor economische en socialegeografie 96(5), pp. 506–514.

Knox, P. (2012) ‘Starchitects, starchitecture and the sym-bolic capital of world cities’, in B. Derudder, M.Hoyler, P.J. Taylor and F. Witlox (eds) InternationalHandbook of Globalization and World Cities,pp. 275–283. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Ma, L.J.C. (2005) ‘Urban administrative restructuring,changing scale relations and local economic devel-opment in China’, Political Geography 24(4),pp. 477–497.

Meng, X. (2004) ‘Economic restructuring and incomeinequality in urban China’, Review of Income andWealth 50(3), pp. 357–379.

SHIN: UNEQUAL CITIES OF SPECTACLE AND MEGA-EVENTS IN CHINA 743

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-02/20/content_417718.htmhttp://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2011-04/13/content_12316447.htmhttp://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2011-04/13/content_12316447.htmhttp://www.chinapost.com.tw/commentary/the-china-post/special-to-the-china-post/2010/06/28/262505/p3/China's-unequal.htmhttp://www.chinapost.com.tw/commentary/the-china-post/special-to-the-china-post/2010/06/28/262505/p3/China's-unequal.htmhttp://www.chinapost.com.tw/commentary/the-china-post/special-to-the-china-post/2010/06/28/262505/p3/China's-unequal.htmhttp://www.chinapost.com.tw/commentary/the-china-post/special-to-the-china-post/2010/06/28/262505/p3/China's-unequal.htmhttp://www.guangzhou.gov.cn/node_2090/node_2386/2005/07/26/112236339662007.shtmlhttp://www.guangzhou.gov.cn/node_2090/node_2386/2005/07/26/112236339662007.shtmlhttp://www.guangzhou.gov.cn/node_2090/node_2386/2005/07/26/112236339662007.shtmlhttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/jan/23/china.jonathanwattshttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/jan/23/china.jonathanwattshttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/apr/15/china.olympicgames2008http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/apr/15/china.olympicgames2008http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/jul/06/china-riots-uighur-xinjianghttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/jul/06/china-riots-uighur-xinjianghttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/oct/06/china-crackdown-african-immigrationhttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/oct/06/china-crackdown-african-immigrationhttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/oct/06/china-crackdown-african-immigrationhttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/apr/21/shanghai-2010-expo-partyhttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/apr/21/shanghai-2010-expo-partyhttp://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/apr/21/shanghai-2010-expo-party

-

New Guangdong (2005) ‘Slogan for 2008 OlympicGames announced’, 27 June, http://www.newsgd.com/news/picstories/200506270001.htm (lastaccessed 9 July 2012).

New Guangdong (2006) ‘20-meter-high elevated sectionof Metro Line 4 to open by year’s end’, 7 July, http://www.newsgd.com/news/guangdong1/200607070055.htm (last accessed 17 June 2012).

New York Times (2008) ‘Dissident’s arrest hints at Olympiccrackdown’, 30 January, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/30/world/asia/30dissident.html (lastaccessed 10 July 2012).

Newton, C. (2009) ‘The reverse side of the medal: aboutthe 2010 FIFA World Cup and the beautification ofthe N2 in Cape Town’, Urban Forum 20(1),pp. 93–108.

People’s Daily Online (2010) ‘8 Guangzhou metro linesopen for Asian Games’, 12 October, http://english.people.com.cn/90001/90776/90882/7163717.html (last accessed 20 August 2012).

People’s Daily Online (2011) ‘Draft plan for ShanghaiExpo Park’s new use released’, 15 March, http://english.people.com.cn/90001/90776/90884/7320750.html (last accessed 12 July 2012).

Perry, E.J. and Selden, M., eds (2003) Chinese Society:Change, Conflict and Resistance, 2nd edn. (London:Routledge Curzon.

Shanghai Daily (2011) ‘Land supply drops in Shanghai’, 6January, http://www.china.org.cn/business/2011-01/06/content_21683706.htm (last accessed 10July 2012).

Shanghai Municipal Planning and Land Resources (2005)‘World Expo relocation in Huangpu to start immedi-ately (in Chinese: Shibo dongqian huangpu ji jiangqidong)’, 13 September, http://www.shgtj.gov.cn/xxbs/lssj/200509/t20050913_272269.htm (lastaccessed 18 July 2012).

Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau (2001) ShanghaiStatistical Yearbook 2001. China Statistics Press

Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau (2011) ShanghaiStatistical Yearbook 2011. China Statistics Press

Shin, H.B. (2009) ‘Life in the shadow of mega-events:Beijing Summer Olympiad and its impact on housing’,Journal of Asian Public Policy 2(2), pp.122–141.

Shin, H.B. and Li, B. (2012) ‘Migrants, landlords and theiruneven experiences of the Beijing Olympic Games’,CASEpaper Series No.163, London: Centre for

Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Econ-omics and Political Science.

Shenzhen Daily (2011) ‘Guangzhou Asiad RMB3b overbudget: auditors’, 28 November, http://www.szdaily.com/content/2011-11/28/content_6265121.htm (last accessed 13 April 2012).

Short, J.R. (2008) ‘Globalization, cities and the summerOlympics’, City 12(3), pp. 322–340.

Smart, A. and Smart, J. (2001) ‘Local citizenship: welfarereform urban/rural status, and exclusion in China’,Environment and Planning A 33(10),pp. 1853–1869.

South China Morning Post (2010) ‘Activists, dissidents andpetitioners ordered to steer clear of venues’, 1 May.

Steenveld, L. and Strelitz, L. (1998) ‘The 1995 RugbyWorld Cup and the politics of nation-building in SouthAfrica’, Media, Culture and Society 20(4),pp. 609–629.

Times of India (2011) ‘Asian Games left Guangzhou inhuge debt: Chinese legislator’, 25 February, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-02-25/others/28633649_1_asian-games-yuan-games-budget (last accessed 12 April 2012).

Trouillaud, P. (2010) ‘China touts Tibet, Xinjiang harmonyat Expo’, AFP, 4 May.

Van der Westhuizen, J. (2004) ‘Marketing Malaysia as amodel modern Muslim state: the significance of the16th Commonwealth Games’, Third World Quarterly25(7), pp. 1277–1291.

Wu, F. (2003) ‘The (post-)socialist entrepreneurial city as astate project: Shanghai’s reglobalisation in question’,Urban Studies 40(9), pp.1673–1698.

Xinhua News Agency (2010) ‘Tibetan orphans from quakezone show up at Shanghai World Expo openingceremony’, 30 April, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2010-04/30/c_13274299.htm(last accessed 10 July 2012).

Xu, J. and Yeh, A.G.O. (forthcoming) ‘Interjurisdictionalcooperation through bargaining: the case ofGuangzhou–Zhuhai railway in the Pearl River Delta,China’, China Quarterly.

Hyun Bang Shin is in the Department ofGeography and Environment at the LondonSchool of Economics and Political Science.Email: [email protected]

744 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

LSE

Lib

rary

] at

01:

33 2

9 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

http://www.newsgd.com/news/picstories/200506270001.htmhttp://www.newsgd.com/news/picstories/200506270001.htmhttp://www.newsgd.com/news/guangdong1/200607070055.htmhttp://www.newsgd.com/news/guangdong1/200607070055.htmhttp://www.newsgd.com/news/guangdong1/200607070055.htmhttp://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/30/world/asia/30dissident.htmlhttp://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/30/world/asia/30dissident.htmlhttp://english.people.com.cn/90001/90776/90882/7163717.htmlhttp://english.people.com.cn/90001/90776/90882/7163717.htmlhttp://english.people.com.cn/90001/90776/90882/7163717.htmlhttp://english.people.com.cn/90001/90776/90884/7320750.htmlhttp://english.people.com.cn/90001/90776/90884/7320750.htmlhttp://english.people.com.cn/90001/90776/90884/7320750.htmlhttp://www.china.org.cn/business/2011-01/06/content_21683706.htmhttp://www.china.org.cn/business/2011-01/06/content_21683706.htmhttp://www.shgtj.gov.cn/xxbs/lssj/200509/t20050913_272269.htmhttp://www.shgtj.gov.cn/xxbs/lssj/200509/t20050913_272269.htmhttp://www.szdaily.com/content/2011-11/28/content_6265121.htmhttp://www.szdaily.com/content/2011-11/28/content_6265121.htmhttp://www.szdaily.com/content/2011-11/28/content_6265121.htmhttp://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-02-25/others/28633649_1_asian-games-yuan-games-budgethttp://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-02-25/others/28633649_1_asian-games-yuan-games-budgethttp://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-02-25/others/28633649_1_asian-games-yuan-games-budgethttp://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-02-25/others/28633649_1_asian-games-yuan-games-budgethttp://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2010-04/30/c_13274299.htmhttp://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2010-04/30/c_13274299.htm

![Smart [ er ] Event | Spectacles | Other Senses](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/56815faf550346895dcea971/smart-er-event-spectacles-other-senses-56c6659538f01.jpg)